Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Hawking The Origin of The Universe

Transféré par

Fe PortabesDescription originale:

Titre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Hawking The Origin of The Universe

Transféré par

Fe PortabesDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

1

The origin of the universe Stephen Hawkings account of the origin of the universe told a story of great brilliance and clarity. The questions Why are we here? and Where did we come from? are very good ones, and we all find ourselves asking them on the day we begin to grow up. When were children, other questions occupy us; we want to know why we cant have more ice cream, and why we have to go to bed right now, and why nothing is fair; but on the day we begin to grow up, which is usually in our early adolescence, we find Professor Hawkings questions becoming more and more interesting. Of course, some people stop growing up, and then they stop asking those questions. They ask other questions instead, such as Whats on TV tonight? or Where can I get the best return for my investments? Professor Hawkings lecture began with an account of the great god Bumba and his digestive problems, which I hadnt heard about before. According to the myths of the Boshongo people, Bumba had a belly-ache and vomited up the sun, the moon, the stars, and various animals including the first human beings. This ingenious piece of gastro-theology provides a very good account of why were here and where we came from, with only the slight disadvantage of being untrue. Or at least unlikely. As I understand Richard Feynmans sum over histories, the great god Bumba may be busily at work somewhere, but probably not in this suburb of the universe. As the lecture progressed, I was struck by how much more interesting Professor Hawkings account was than that of the Boshongo people. I dont only mean more likely, more persuasive, better argued, though it was all of those; I mean more interesting. It was better storytelling: I always wanted to hear what was going to happen next, and why. It was full of more interesting characters and settings. The Steady State, for example, which I couldnt help picturing as a sort of 1950s advertisement, with a pipe-smoking father sitting comfortably in his living room, next to the radiogram, with a wife knitting submissively in the background, and a small boy playing with Meccano on the carpet. The father would remove his pipe and twinkle knowledgeably as he said Of course, Im with Steady State Insurance, and a

caption underneath would say You Know Where You Are With a STEADY STATE Policy. Then there were other fascinating characters, such as the General Theory of relativity, and the microwave radiation from the very early universe that turns up on your television screen, and the spontaneous quantum creation of little bubbles that grow, or dont grow, into universes.

Another reason that the story we heard from Professor Hawking was different from that of the Boshongo people has to do with the relationship we have with the story itself. Its to do with the way we, the audience at an academic lecture, the congregation in a church, the jury in a courtroom, the listeners around the cooking fire in the darkness of the savanna, the way we regard the stories were hearing. Different kinds of stories expect different kinds of audience and certain kinds of attitude from that audience. I dont mean an attitude of liking or respect, though every storyteller would like those; what I mean is theres something in the circumstances of the telling that says This story is to be taken literally, or This is a metaphor. One thing stands for another. Because in the normal course of life, we depend on knowing which attitude its appropriate to take to the stories we hear. A witness in court might be telling the truth, or telling a lie, and the jury might believe him or not; but they dont think that hes talking in metaphor. If the prosecuting counsel says Tell the court what you saw the accused do, and the witness says He stuck a knife in the victims heart, the jury isnt expected to understand this as meaning I saw him write a savage review of the victims latest book. The jury is there to decide whether or not the statement is true, but not what kind of statement it is. Its supposed to be a literal one. Now we dont know whether the first people who listened to the Bumba story thought it was literally true. Maybe they did. But I think that if people have evolved to the point where they can tell stories at all, theyve already got a fairly sophisticated mental world in place, in which they know the difference between whats literal and whats figurative. After all, every one of the Boshongo people must at some point have eaten a piece of dead wildebeest or something that didnt agree with them, and the consequences of that would have looked nothing like the sun, the moon, the stars and the animals and so on. So they were capable of thinking that Bumbas belly-ache and its results were like theirs in some ways but unlike them in others: they were capable of thinking in analogy or metaphor.

As long as that mental capacity persists, human beings are able to think about their world and describe it in more ways than one, and a very great gift that is. At the high point of what we might call the Bumba tendency, we find the sublime poetry of Miltons account of the creation in Paradise Lost. Milton pictures the angel Raphael talking to Adam and Eve and telling them what happened before they themselves were created, and does it in words that celebrate the sensuous physical beauty of the world so vividly that its impossible, for this atheist at least, to withhold a rush of imaginative empathy. I know it isnt literally true, and yet I can enjoy it to the full. Most of us are capable of that sort of mental double vision, and that capacity cant only have evolved last week. I think its as ancient as language and as humanity itself. The trouble comes when the fundamentalists insist that there is no such thing as analogy or metaphor, or else that they are wicked or Satanic, and that there must only be a literal understanding of stories. The Bible is literally true. The world was created in six days. The Kansas Board of Education says so. The worshippers of Bumba, as far as we know, havent developed this modern perversion, this modern limitation on the meaning of narrative; its only the worshippers of Yahweh and Allah who are as silly as that. The delight for me in the account Professor Hawking gave us tonight, and has given us in his marvellous book A Brief History of Time, is that we can both listen to it with wonder and take it literally. Its a tale of heroic endeavour, of intellectual daring and imaginative brilliance without parallel, and those people like me who are in the business of playing variations on the Bumba story, and trying to get as close to the Milton end of the spectrum as our talent will let us, can only take off our hats and salute the storytelling of those like Professor Hawking those who not only tell the story, but who themselves played a part in the events: who uncovered a corner of the mystery, who shone a light into the darkness and revealed something that no-one had ever seen before.

The sort of story that these great heroes (and Im using the word carefully and accurately) that these great heroes of modern science tell does have one thing in common, and I mean in a technical, structural sense, with stories of the Bumba sort. And that has to do with how they end. Most stories that we read in novels or fairy tales, or see in films and plays, are shaped with a conclusion in mind. The events are all arranged to lead up to And they lived happily ever after. Or Reader, I married him. Or the last sentence of George Orwells Animal Farm: The creatures outside looked from pig to man, and from man to pig, and from pig to man again; but already it was impossible to say which was which. Stories of that kind take us on a journey through harmonies and tensions and releases and discords and finally we come to a resolution. The storys done; all the ends are tied up; theres no more to be said. But the stories that both religion and science tell us about our origins dont do that. There isnt that sense of cadence and finality that we have at the end of a play or novel, or the aesthetic and moral closure we feel at the end of one of the classic fairy tales. Stories about origins dont have that sort of determined ending. The religious kind of origin-story might tell us that we were brought forth by a great father in the sky, or in the case of Bumba by a great gurgitator, and they usually go on to put us in some kind of relationship with our creator. We are his children. We owe him gratitude and worship and obedience. The other kind of origin-story, the scientific kind, tells us about the development of matter from the first moments of the universe, the formation of atoms, the way atoms join with other atoms to form more complex structures that eventually give rise to life, and how life itself evolves by means of natural selection. We are the children of the sky-god, or we are made of the same material as the stars.

Either way, stories like this tell us how we got here: but then they say, in effect, The story continues, and the rest is up to you. And whether or not we know this, whether or not we like it, that puts us in a moral relationship with the thing we came from, too, whether thats God or whether its nature. The God stories go on to make this quite explicit: do this, believe that. The stories of science have moral consequences too, but they convey them more subtly, by implication; we might say more democratically. They depend on our contribution, on our making the effort to understand and concur. The implication is that true stories are worth telling, and worth getting right, and we have to behave honestly towards them and to the process of doing science in the first place. Its only through honesty and courage that science can work at all. The Ptolemaic understanding of the solar system was undermined and corrected by the constant pressure of more and more honest reporting: Yes, we know the planets are supposed to go round the earth in perfect circles, but really, if you look, you dont see that. You see this instead. Now why do you think that could be? Whats actually going on up there? So we have the courage of such as Galileo and the other victims of persecution and fearful closed-mindedness. I was very glad to hear that Professor Hawking escaped the clutches of the Inquisition during his visit to the Vatican; four hundred years ago, he would not have done, and in the context of the time scales weve been hearing about tonight, four hundred years is the merest flicker of an instant. We sometimes forget how lucky we are to live in this little bubble of time which is still warmed, you could say, by the background radiation from the Enlightenment. Were privileged today to be able to hear the words of Professor Hawking without having to meet in secret, without having to depend on passwords and disguises, without the danger of betrayal and arrest and torture; and that is not only because of the intellectual brilliance of the great heroes of science, both past and present, but because of their valour too.

Professor Hawking ended his lecture with a survey of the current state of cosmology, and the prediction that we are getting close to answering the age-old questions Why are we here? Where did we come from? Some people are rather afraid of thinking that there might be a final answer to those questions; they think it will take all the mystery and delight out of the universe. I think they could hardly be more wrong. The more we discover, the more wondrous the universe seems to be, and if we are here to observe it and wonder at it, then we are very much part of what it is. And there is no shortage of important questions. Once we know where we come from, we might find that our attention turns to questions like Where are we going? What shall we do? The story continues, and the rest is up to us. Im immensely grateful to science, and to Stephen Hawking in particular, for illuminating our path to the present day with such brilliant clarity, such intellectual daring, and such wit.

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- CommitteesDocument3 pagesCommitteesFe PortabesPas encore d'évaluation

- St. Mary's College Tagum City Holy Rosary Leaders (Every Saturday)Document1 pageSt. Mary's College Tagum City Holy Rosary Leaders (Every Saturday)Fe PortabesPas encore d'évaluation

- Human Rights NmemonicDocument1 pageHuman Rights NmemonicFe PortabesPas encore d'évaluation

- Bar Q & A On PropertyDocument8 pagesBar Q & A On PropertyFe Portabes100% (1)

- Name: Cristy M. Boquel Teacher: Mrs. Dahab Course and Year: Fourth Year BSBA Subject: FM 8Document1 pageName: Cristy M. Boquel Teacher: Mrs. Dahab Course and Year: Fourth Year BSBA Subject: FM 8Fe PortabesPas encore d'évaluation

- Lord, Overflow Us With Your LoveDocument3 pagesLord, Overflow Us With Your LoveFe PortabesPas encore d'évaluation

- Academic Club: Room Assignment Math & Science Club Filipiniana Club English Club Jpia JBA PicesDocument3 pagesAcademic Club: Room Assignment Math & Science Club Filipiniana Club English Club Jpia JBA PicesFe PortabesPas encore d'évaluation

- MissionDocument1 pageMissionFe PortabesPas encore d'évaluation

- CompetitionDocument1 pageCompetitionFe PortabesPas encore d'évaluation

- To All Participants of Musical Drama For Mother Ignacia: What?Document3 pagesTo All Participants of Musical Drama For Mother Ignacia: What?Fe PortabesPas encore d'évaluation

- Letter For MayorDocument1 pageLetter For MayorFe PortabesPas encore d'évaluation

- Introductio 2Document2 pagesIntroductio 2Fe PortabesPas encore d'évaluation

- September 12Document1 pageSeptember 12Fe PortabesPas encore d'évaluation

- 11 November 2008. AnnouncementDocument1 page11 November 2008. AnnouncementFe PortabesPas encore d'évaluation

- Sta - Cruz Davao Del Dur, Philippines: Submitted By: Mary Cris T. Kuizon Bsed 3Document1 pageSta - Cruz Davao Del Dur, Philippines: Submitted By: Mary Cris T. Kuizon Bsed 3Fe PortabesPas encore d'évaluation

- Letter Student's AmbassadorDocument2 pagesLetter Student's AmbassadorFe PortabesPas encore d'évaluation

- Announcement For IntramsDocument4 pagesAnnouncement For IntramsFe PortabesPas encore d'évaluation

- Appointment of The Different YLO Advisers & Club ModeratorsDocument1 pageAppointment of The Different YLO Advisers & Club ModeratorsFe PortabesPas encore d'évaluation

- Attention!: To All College StudentsDocument3 pagesAttention!: To All College StudentsFe PortabesPas encore d'évaluation

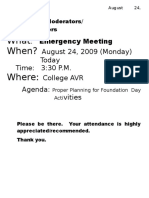

- August 24Document2 pagesAugust 24Fe PortabesPas encore d'évaluation

- Introduction MIWS MassDocument1 pageIntroduction MIWS MassFe PortabesPas encore d'évaluation

- Major Events: Basketball MenDocument5 pagesMajor Events: Basketball MenFe PortabesPas encore d'évaluation

- List of Students 201Document65 pagesList of Students 201Fe PortabesPas encore d'évaluation

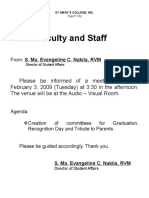

- Awards Com. MTGDocument2 pagesAwards Com. MTGFe PortabesPas encore d'évaluation

- School Chapel 2012Document3 pagesSchool Chapel 2012Fe PortabesPas encore d'évaluation

- HM/TM Programs Family DayDocument15 pagesHM/TM Programs Family DayFe PortabesPas encore d'évaluation

- Prayer For The Beatification of Venerable Ignacia Del Espiritu SantoDocument1 pagePrayer For The Beatification of Venerable Ignacia Del Espiritu SantoFe PortabesPas encore d'évaluation

- 09-09-2017 Dacs Osas Committee & Sports Coordinators Kindly Proceed To The President'S Board Room Thanks!Document1 page09-09-2017 Dacs Osas Committee & Sports Coordinators Kindly Proceed To The President'S Board Room Thanks!Fe PortabesPas encore d'évaluation

- NikaDocument1 pageNikaFe PortabesPas encore d'évaluation

- Dacs Liquidation LabelDocument1 pageDacs Liquidation LabelFe PortabesPas encore d'évaluation

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5794)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (895)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (344)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (399)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (588)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (266)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (73)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)

- AsfanDocument4 pagesAsfanAsfandyar khanPas encore d'évaluation

- Reading ComprehensionDocument3 pagesReading ComprehensionSofia LainezPas encore d'évaluation

- Conditional Sentence BookDocument10 pagesConditional Sentence BookErwin Hari KurniawanPas encore d'évaluation

- SciFiNow Annual Volume 1 - 2014Document180 pagesSciFiNow Annual Volume 1 - 2014Silviu MerticPas encore d'évaluation

- Creative Nonfic ReviewerDocument8 pagesCreative Nonfic ReviewerDarlito AblasPas encore d'évaluation

- 3º Adolescentes Mock Exam 1Document4 pages3º Adolescentes Mock Exam 1miriamacunaPas encore d'évaluation

- Catcher in The Rye - ConflictDocument3 pagesCatcher in The Rye - ConflictJohn RattrayPas encore d'évaluation

- The Tempest SDocument8 pagesThe Tempest SAlex PopPas encore d'évaluation

- Lizardmen Spec RulesDocument9 pagesLizardmen Spec RulesToby Roberts100% (1)

- m07 190Document46 pagesm07 190Alena AndreichukPas encore d'évaluation

- Adventures of Huckleberry FinnDocument179 pagesAdventures of Huckleberry FinnShavonta OutlandPas encore d'évaluation

- Seasons in ShadowDocument6 pagesSeasons in ShadowJarne VreysPas encore d'évaluation

- 21st Century Reviewer 075147Document10 pages21st Century Reviewer 075147salvacionkattbeatrizPas encore d'évaluation

- Hindi Bifurcated SyllabusDocument1 pageHindi Bifurcated SyllabusPunya Surana0% (1)

- Of Being Numerous - George OppenDocument27 pagesOf Being Numerous - George OppenFenetus Maíats100% (1)

- 21st Century Literature (Week 4)Document8 pages21st Century Literature (Week 4)China PandinoPas encore d'évaluation

- The Origin and Development of English Novel: A Descriptive Literature ReviewDocument6 pagesThe Origin and Development of English Novel: A Descriptive Literature ReviewIJELS Research JournalPas encore d'évaluation

- 100 Câu Tr c Nghi m Ng Pháp 01 ắ ệ ữDocument16 pages100 Câu Tr c Nghi m Ng Pháp 01 ắ ệ ữht117Pas encore d'évaluation

- Opinion Rubric Kid FriendlyDocument2 pagesOpinion Rubric Kid Friendlyapi-332467439Pas encore d'évaluation

- L430-Lucian VI Dipsads Saturnalia Herodotus or Aetion Zeuxis or Antiochus Harmonides HesiodDocument524 pagesL430-Lucian VI Dipsads Saturnalia Herodotus or Aetion Zeuxis or Antiochus Harmonides HesiodFreedom Against Censorship Thailand (FACT)100% (1)

- A Brief History of 21st Century Philippines LiteratureDocument6 pagesA Brief History of 21st Century Philippines LiteratureLeigh Nathalie LealPas encore d'évaluation

- 7C's of Communication PresentationDocument15 pages7C's of Communication PresentationBabar NaeemPas encore d'évaluation

- IB English Paper 2 NotesDocument14 pagesIB English Paper 2 NotesShane Constantinou92% (24)

- (Quarter 4 in English 9 - MODULE # 1) - Judge The Relevance and Worth of Ideas, Soundness...Document3 pages(Quarter 4 in English 9 - MODULE # 1) - Judge The Relevance and Worth of Ideas, Soundness...Maria Buizon100% (2)

- Banglabook Links 13Document12 pagesBanglabook Links 13channel_partners5979Pas encore d'évaluation

- Heart of Darkness Full CH 1Document4 pagesHeart of Darkness Full CH 1Connor MunroePas encore d'évaluation

- K-2 Ela-1Document219 pagesK-2 Ela-1Julie SuteraPas encore d'évaluation

- Collins KS2 English RG - Marketing Pages PDFDocument8 pagesCollins KS2 English RG - Marketing Pages PDFjennetPas encore d'évaluation

- 35figure of SpeechDocument8 pages35figure of SpeechAsh UrlopePas encore d'évaluation

- Codex - Eldar HarlequinsDocument11 pagesCodex - Eldar HarlequinsmarkPas encore d'évaluation