Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

(Social Peripheries and Drugs An Ethnographic Study in Psychotropic Territories)

Transféré par

Joao SilvaDescription originale:

Titre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

(Social Peripheries and Drugs An Ethnographic Study in Psychotropic Territories)

Transféré par

Joao SilvaDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Chapter 15 Social peripheries and drugs: an ethnographic study in psychotropic territories

Lus Fernandes In the social sciences, it is now commonplace to say of any subject that it is complex. The topic of this chapter drugs and social exclusion brings together two subjects which are complex enough separately. Each of them is a lasting social problem and a source of riddles for the analytical perspective of the human sciences. Moreover, both subjects intersect at some point in the course of the development of social processes in western societies: if we look at drugs, we come upon social exclusion; when we look at social exclusion, we are forced to take drugs into consideration. The starting-point for our ethnographic research was the description of illegal drug use in an urban-industrial context. At first, we had not even thought about relating this issue to social exclusion: our crucial interest lay in drugs and their use as symbolic features of youth behaviour. In this chapter, the following topics are discussed: the way in which, almost involuntarily, ethnographic research forced us to analyse drugs and social exclusion together; the relationship between illegal drug use and social exclusion from the standpoint rendered possible by the ethnographic method; and the way in which fieldwork made us question drugs, social exclusion and the ethnographic method itself.

Building an ethnographic project

I believe that the real evolution of research ideas is not in accordance with the formal descriptions we read about research methods. Ideas are born, in part, from our immersion in the data and in the process of living ... Only by accumulating a series of reports on how a study is really conducted will we be able to go beyond the logical-intellectual image and learn how to describe the research process. (Whyte, 1955) The ethnographic research we have been developing is part of a set of investigations carried out, since 1983, by the Centro de Cincias do Comportamento Desviante (Centre for the Study of Deviant Behaviour CCCD) at the Faculty of Psychology and Educational Sciences at the University of Oporto. These research projects have

143

Social exclusion been guided by an attempt to understand deviant behaviour as bio-psycho-social phenomena: studies have ranged from laboratory work in psycho-physiology to street ethnography concerned with social ecology. You dont get into drugs without getting out on the street Our experiences as drugs researchers began in a drug treatment unit. The excessive focus on a psycho-pathological approach, and the differences in speech we noticed between the users while inside and outside the institution, quickly led us to become critical of the clinical approach. In 1985, when we joined the CCCD, we were searching for a different way of looking at drug use a naturalistic look. Our preferred method was in accordance with the research directors aim: the creation of a multidisciplinary research team able to conduct research ranging from experimental to ethnographic methods, from the laboratory to the field, from the biological to the social-cultural approach. In a sentence, he summarised the role of the latter: You cant get into drugs without getting out on the street. The naturalistic look would study the phenomenon of drugs in its daily manifestations, in the actual places where its logic constitutes itself and interacts with the logic of social life, far from clinical and juridical reductionism. Extremes touch Initially, we produced a history of the drug use of young people in Portugal, so as to contextualise practices revolving around forbidden products and the meanings these had for the groups involved. In this way, we established a trajectory of youth psychotropism based on drug users life histories. To summarise very briefly, before the revolution of 1974 which restored democracy in Portugal drugs had very little social visibility. During this period, drugs were found only in cultural elites influenced by Anglo-Saxon pop-rock imagery. We named it the lysergic period in a restricted circle. The drugs used were LSD and marijuana. After April 1974, there are two clear-cut periods. The first lasted until 1980, when drug use was part of behavioural and symbolic constellations associated with youth subcultures (the hashish smoker freak is the main character here). Adolescent drug use expanded and the social-political construction of the drug problem began (see Agra, 1993, for an analysis of the construction of juridical instruments and care structures related to the fight on drugs). The second period began around 1980 and was characterised by the progressive establishment of a hard drugs market: heroin and the junkie become the protagonists. Although drug use had increased during the freak period, in the junkie period harder drugs began to be used and there was the progressive involvement of the socially less favoured. When we first got out on the street, we chose to study an old historical neighbourhood in the centre of the town of Oporto which popular rumour then associated with drug users. Our aim was to produce an ethnography of drugs in youth

144

Chapter 15 subcultures. However, the year was 1985, subcultures were less and less important as initiation contexts in the drugs scene, and we were obliged to change our focus. Other contexts and social actors turned urban peripheries into the scenarios for the new elements of urban insecurity: the junkie, the dealer and the drugs markets. In a period of 20 years, drugs had moved from restricted middle- and upper-class groups to the socially less favoured, until they reached the working class, socially excluded groups living in the towns social-spatial periphery. If, as according to a popular saying, extremes touch, then we can say that drugs had now touched both extremes of the social scale. The drugs problem, previously approached as a youth management political issue (drug use prevention), a clinical issue (care and treatment) and a juridical issue (war on drugs), shows great adaptability to strategies aimed at its destruction. Ironically, confirming the popular virus metaphor, the drugs epidemic invades the social groups and urban areas which are resistant to social control techniques. It is in the context of this deep change that social exclusion emerges as an analytical topic, and the evolution of the phenomenon led us to the main topic of our next ethnographic research: an urban periphery associated with social exclusion.

Psychotropic territories

Since 1990, we have been focusing our research on council estates, some of which are persistently called drugs hypermarkets by the media. Between October 1992 and the summer of 1993, we lived in one of those estates, so as to maximise research opportunities and to immerse ourselves as much as possible in the context. What follows is a short summary of the issues developed on the basis of fieldwork data. The drugs estates The images of social exclusion are concentrated in these areas. The primary consequence is the increase of isolation foreshadowed by the estates topographic position in relation to the town. They are places where the town is interrupted: our fieldwork data describe in detail the features of this spatial and social fracture. The analysis of daily life there allows us to look at these zones as parallel social spaces, often represented by their own inhabitants as territories under siege. Drugs in the estates The two main social actors in these territories are the dealer (usually also a drug addict) and the junkie (addicted to hard drugs). They are the main characters in the drugs street scene, and their activities develop as interstices of space and time. We also focused on socialisation processes in these contexts: that is, on how one learns to live in psychotropic territories.

145

Social exclusion At a later stage, when reassembling the data the writing-up phase, which involves a degree of construction above that of the writing down (Atkinson, 1990) the hypothesis was developed that the present eco-social configuration of drugs is an adaptive response to its juridical-moral status. Such an adaptive response allows it to survive, and even expand, despite the numerous measures developed by the machine devoted to fighting drugs. It has at least three axes. Economic adaptation. Council estates associated with the drugs business are sites of economic fragility, and their inhabitants are either poor or vulnerable to poverty. Economic and labour marginalisation makes it much more likely that they will become involved in street drug dealing than inhabitants of other parts of the town. It might be asked why this does not occur in any poor or vulnerable site: it is because space needs to fulfil some conditions it must favour ecological adaptation. Ecological adaptation. War on drugs strategies have generated defensive reactions on the part of the street markets and the places where drug consumers congregate. Both moved to sites which repressive forces find more difficult to access. The drugs council estate is in morpho-topological discontinuity with its urban environment, making it possible for territories over which effective vigilance can be maintained to be constructed. Psychological adaptation. According to Wirth (1928), the ghetto is not only a physical place but a state of mind. The state of mind offered by heroin is anaesthesia which, in a site kept away by the town the ghetto allows one to be kept away. The drugs hypermarket is, then, organised as a territory. We have called it psychotropic territory, and, according to the environmental psychology notion of behaviour setting, defined it as a place of concentration of social actors with a role in the drugs business ... It attracts people sharing an interest in a lifestyle in which drugs play a major role it is ... a spatial matrix of a junkie street subculture ... Its main communicational feature is minimal interaction and it is structured as an interstice of space and time (Fernandes, 1998).

Conclusions

To carry out ethnographic research is a personal experience that leads to much reflection, particularly when it concerns those in an area on the margin of the normative town. In this final section, we discuss what that experience has led us to question. The world of drugs is a faraway entity that brings on feelings of fear and threat. At the social-political level this translates as the war on a plague or epidemic. Daily contact with this quasi-virus forced us to question these images, not in order to deny the social seriousness of some of its manifestations, but to look at the drugs world as a normal phenomenon in our societies. It is normal because the mechanisms of its

146

Chapter 15 production are not located outside social dynamics, because it is repetitive and recurrent, and because it is established in the concrete practices of the concrete town. The ethnographers role in the phenomenon of drugs may then be that of helping its re-naturalisation. The voluntary alteration of the state of the mind through the use of psychoactive substances was turned into a strange, pathological and criminogenic behaviour during the western process of medicalisation and juridification; it is necessary to reinsert it in the social practices from where it emerged. After the attempt to silence it the first aim of the war on drugs it is now time to let it speak: about our social mechanisms, particularly those that produce social exclusion. Our aim here has been to discuss the potentialities and limitations of ethnography. As potentialities, we stress its openness and adequation. As limits, we stress its instrumentalisation. Openness refers to the ability of ethnography to generate relations with other objects from the initial research object. In our case, drugs led us first to youth subcultures, and later to social exclusion and urban insecurity. We were also stimulated to analyse social-spatial peripheries of the town. Adequation means that ethnography is useful to reach and observe layers of reality inaccessible to almost every other research method: those of the hidden populations (Adler, 1990) whose social practices are developed backstage (Goffman, 1961). Instrumentalisation is to be avoided. It occurs when the ethnographer is used as an undercover agent who may serve invasive control strategies. Ethnography might join a strategy that replaces a policed society with a softer surveillance machine made up of social scientists. The author is Professor at the Faculdade de Psicologia e Cincias da Educao da Universidade do Porto, Portugal, and a researcher at the Centro de Cincias do Comportamento Desviante at the same university.

147

Social exclusion

References

Adler, P. (1990) Ethnographic Research on Hidden Populations: Penetrating the Drug World, National Institute on Drug Abuse Research, Monograph Series. Agra, C. da (Ed.) (1993) Dizer a Droga, Ouvir as Drogas, Oporto: Radicrio. Atkinson, P. (1990) The Ethnographic Imagination: Textual Construction of Reality, London: Routledge. Fernandes, L. (1998) O Stio das Drogas, Lisbon: Notcias. Goffman, E. (1961) Asylums: Essays on the Social Situation of Mental Patients and Other Inmates, Garden City, NY: Doubleday Books. Whyte, W. F. (1955) Street Corner Society: the Social Structure of an Italian Slum, Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Wirth, L. (1928) The Ghetto, Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

148

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5782)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (587)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (890)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (72)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (399)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (265)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (344)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2219)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)

- Medical AspectsofBiologicalWarfareDocument633 pagesMedical AspectsofBiologicalWarfaredennyreno100% (2)

- Levels of Organization Answers PDFDocument3 pagesLevels of Organization Answers PDFKevin Ear Villanueva100% (4)

- Herbal Remedies For Treatment of HypertensionDocument22 pagesHerbal Remedies For Treatment of HypertensionIan DalePas encore d'évaluation

- WATER QUALITY STANDARDS FOR BEST DESIGNATED USAGESDocument4 pagesWATER QUALITY STANDARDS FOR BEST DESIGNATED USAGESKodeChandrshaekharPas encore d'évaluation

- Jaw RelationsDocument44 pagesJaw Relationsjquin3100% (1)

- Fundamentals of Nursing: Urinary Elimination, Catheterization, Ostomy Care & Pain ManagementDocument29 pagesFundamentals of Nursing: Urinary Elimination, Catheterization, Ostomy Care & Pain ManagementKatrina Issa A. GelagaPas encore d'évaluation

- F&C Safety Data Sheet Catalog No.: 315407 Product Name: Ammonia Solution 25%Document7 pagesF&C Safety Data Sheet Catalog No.: 315407 Product Name: Ammonia Solution 25%Rizky AriansyahPas encore d'évaluation

- Diabetes Treatment Report ProposalDocument4 pagesDiabetes Treatment Report ProposalrollyPas encore d'évaluation

- Springhouse - Rapid Assessment - A Flowchart Guide To Evaluating Signs & Symptoms (2003, LWW) PDFDocument462 pagesSpringhouse - Rapid Assessment - A Flowchart Guide To Evaluating Signs & Symptoms (2003, LWW) PDFvkt2151995Pas encore d'évaluation

- Nursing Research Group Assignment UoDDocument6 pagesNursing Research Group Assignment UoDShadrech MgeyekhwaPas encore d'évaluation

- Biocontamination Control Techniques For Purified Water System - Pharmaceutical GuidelinesDocument1 pageBiocontamination Control Techniques For Purified Water System - Pharmaceutical GuidelinesASHOK KUMAR LENKAPas encore d'évaluation

- CHN TextbookDocument313 pagesCHN TextbookCynfully SweetPas encore d'évaluation

- COVID-19 violators should face sanctionsDocument2 pagesCOVID-19 violators should face sanctionsAkmal BagyaPas encore d'évaluation

- Emergency Action Code 2013Document200 pagesEmergency Action Code 2013MiguelPas encore d'évaluation

- Plant Pathology LabDocument79 pagesPlant Pathology Labpraveenhansraj87% (15)

- Dräger Incubator 8000 IC - User ManualDocument60 pagesDräger Incubator 8000 IC - User ManualManuel FloresPas encore d'évaluation

- Cfda-Nrega Monitoring and Evaluation ReportDocument87 pagesCfda-Nrega Monitoring and Evaluation ReportAnand SugandhePas encore d'évaluation

- Post Stroke DepressionDocument15 pagesPost Stroke DepressionJosefina de la IglesiaPas encore d'évaluation

- Margo Lynch, Ppa Dennis Lynch, Dennis Lynch and Margaret Lynch v. Merrell-National Laboratories, Division of Richardson-Merrell, Inc., 830 F.2d 1190, 1st Cir. (1987)Document11 pagesMargo Lynch, Ppa Dennis Lynch, Dennis Lynch and Margaret Lynch v. Merrell-National Laboratories, Division of Richardson-Merrell, Inc., 830 F.2d 1190, 1st Cir. (1987)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- Unit 5 General Techniques of Detection and Enumeration of Micro-Organisms in FoodDocument62 pagesUnit 5 General Techniques of Detection and Enumeration of Micro-Organisms in FoodBROOKPas encore d'évaluation

- METABOLISM AND THERMOREGULATIONDocument44 pagesMETABOLISM AND THERMOREGULATIONriezanurdinsyahPas encore d'évaluation

- Addisons DiseaseDocument1 pageAddisons DiseaseAndreia Palade100% (1)

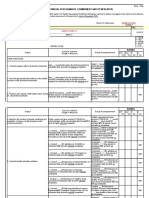

- Individual Performance Commitment and Review (Ipcr) : Name of Employee: Approved By: Date Date FiledDocument12 pagesIndividual Performance Commitment and Review (Ipcr) : Name of Employee: Approved By: Date Date FiledTiffanny Diane Agbayani RuedasPas encore d'évaluation

- Nurs208 Qa Practice Reflection Worksheet 1Document1 pageNurs208 Qa Practice Reflection Worksheet 1api-34714578980% (5)

- Pol 324Document176 pagesPol 324James IkegwuohaPas encore d'évaluation

- Soap For Follow On Hiv-Aids #7Document2 pagesSoap For Follow On Hiv-Aids #7carlos fernandezPas encore d'évaluation

- RCL Softball Registration FormDocument1 pageRCL Softball Registration FormRyan Avery LotherPas encore d'évaluation

- Meningitis Pathophysiology PDFDocument59 pagesMeningitis Pathophysiology PDFpaswordnyalupa100% (1)

- WHO's BulletinDocument11 pagesWHO's BulletinThiago MotaPas encore d'évaluation