Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Will CCT Help or Hurt The Poor

Transféré par

Aj de CastroTitre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Will CCT Help or Hurt The Poor

Transféré par

Aj de CastroDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Will CCT help or hurt the poor?

The conditional cash transfer (CCT) programs worked for some countries. It might work for us. The CCT is certainly better than the many disparate poverty alleviation programs and projects in the past which have been characterized by large leakages (benefits go to the unintended beneficiaries, corrupt bureaucrats, and greedy politicians). As a general rule, if the government wants to help the poor, it is better to give the poor cash rather than rice or noodles or something else. So much is lost in procuring the goods and in storing and transporting the goods. And so much waste is incurred when goods end up in the hands of the less deserving beneficiaries the ward leaders and supporters of politicians rather than the truly needy. This has been the story of poverty alleviation programs in the past. Hundreds of billions are lost in shady importation of rice, and making the same rice accessible at less than market clearing prices for all rice, middle income and poor. While the poor have to struggle the whole day to be able to afford a kilo of rice, the rich who dont need government subsidy are able to buy rice at subsidized rate anytime. Some legislators call the Aquino administrations conditional cash transfer, or CCT, a way of encouraging mendicancy among the poor. Thats a label that has no rigorous basis. CCT programs worked in other countries and they might work for the Philippines too. For the CCT beneficiaries, it might be a possible way out of poverty. It might even a way out of patronage politics. Mendicancy is when you ask the poor to line up in provincial capitols or city halls or congressional district offices for free medicine or a kilo of rice. Mendicancy is when you ask the poor to queue in congressional district officers for scholarships to high schools, TESDA training centers, or colleges. It is much better when scholarship is awarded based on scholastic performance or on excelling in a competitive exam rather than on political connection. Mendicancy is when legislators park part of their pork barrel in specialty hospitals or other public hospitals so that they can sponsor their ward leaders or political supporters (not necessarily the poor) when they get sick. Of course, the ideal public policy is to provide universal basic health care, when citizens get medical attention based on needs rather than on their income or political color. If it works, why are some politicians opposed to it? The first generation CCT programs originated in Brazil and Mexico, but CCT programs are now found across some 30 countries in Latin America, Asia, and Africa. They have been found to be effective in reducing poverty and have increased the use of education and health services. They have reduced dropout rates in Mexico, Cambodia, Pakistan, and other countries. CCT programs might actually work for the Philippines. So, why would a well-meaning legislator be opposed to the conditional cash transfer program? Let me list down some plausible reasons. First, some legislators are bound to be losers in the budget allocation process. Since budget authorization is a zero-sum game, that is, whatever is authorized for CCT is money taken away from programs that do not directly benefit the poor. CCT is expected to benefit 2.3 million families (roughly 11.5 million people or one-third of the poor population). Remember that under the Constitution, Congress may decrease but not increase the budget as submitted by the President. This maybe a hard pill to swallow for legislators who represent constituencies who are not poor and with no children of school age enrolled in public schools. Second, some legislators will lose political influence since CCT will be directly distributed by DSWD Secretary Dinky Solimans crew to the targeted 2.3 million families. The process of distributing the CCT is assumed to be better targeted (based on a very costly survey of who are the poorest of the poor). It can also be expected that the choice of beneficiaries will be transparent

(names of beneficiaries will be posted in the DSWD Web site and can be contested). Since legislators have nothing to do with the identification of beneficiaries and no in-kind subsidy (rice, noodles, drugs and medicines, and scholarships) will pass through the congressional district offices or other legislator distribution units, naturally they wont get credit for government assistance. Imagine P29.1 billion worth of cash transfer, and no credit for individual legislators! Third, the CCT may actually change the lives of the poorest of the poor. And if that happens, they may start to believe that President Aquino III is their savior. It worked in Brazil under the very charming and politically astute Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva. After two terms, Lula is stepping down with a better Brazil. Poverty is significantly down (from an average of 33.8% of population in 1993-95 to 15.3% in 2009), the quality of life of Brazilians has improved, and economic growth has quickened. With the success of CCT, the poor may shift their loyalty to national officials and away from their individual legislators whom they rarely see anyway. This is a distinct possibility which some legislators dread. Legislators who are opposed to the cash transfer argue that CCT cannot take the place of a long-term strategy that addresses the root causes of poverty through asset redistribution and job generation. Thats true. But the CCT and the long-term poverty reduction programs are not mutually exclusive. In its war against poverty, the government has to start somewhere. The CCT will help, not hurt, the poor. CCT in Philippines is teaching people how to fish By Karin Schelzig Bloom Philippine Daily Inquirer First Posted 01:30:00 05/17/2008 Filed Under: Education, Children, Poverty Give a man a fish and he?ll eat for a day, but teach him how to fish and he?ll eat for a lifetime. This principle is at the core of a new way of doing social assistance in Asia. Conditional cash transfer (CCT) programs provide benefits to families on the condition that they invest in their children?s future. The Department of Social Welfare and Development?s new Ahon Pamilyang Pilipino program provides cash benefits to families that take their children for regular health checkups and ensure that they go to school. An 85-percent attendance rate is mandatory. Other conditions require that pregnant women should receive appropriate pre- and post-natal care. Compliance with the conditions is verified. Families receive the full benefit only when all conditions are met?the money is not a ?dole-out.? Smarter, healthier kids Investing in children?s human capital?ensuring that they grow into educated and healthy adults?is the equivalent of teaching them how to fish. Healthy, educated children ultimately have more choices in life and are able to become productive members of society. CCT programs help to break the vicious cycle of poverty. There is a gender empowerment element as well, with cash benefits usually paid to mothers. CCT programs also reduce child labor, since families no longer have to weigh the opportunity costs of sending Juan or Juanita to school when they could be earning money to help put food on the table. Too good to be true? Are CCTs too good to be true? One need only look to Latin America, where there is a wealth of evidence documenting CCT program successes after many years of experience. Perhaps the most famous program, Mexico?s Oportunidades [Opportunities], has been around for more than a decade, with very positive results. The incidence and severity of poverty have fallen, school enrolment and completion rates have improved, health indicators are up, and malnutrition is down. Rigorous monitoring and evaluation, built in from the very beginning, is credited with being

able to demonstrate real impacts. Oportunidades now serves more than 25 million Mexicans and is one of the few large-scale poverty reduction programs that have withstood a change in political administration, no small feat in itself. All of this is not to say that CCT programs are without challenges. Doing it right requires a commitment to support households at least over the medium term (say, five years) in order to help them break out of the cycle of poverty. Identifying and targeting the poorest is always difficult. Setting appropriate benefit levels is complicated, and a payment system must be devised. CCT programs can be complex to administer. The supply of highquality services has to be sufficient if demand for those services is increased. There will be growing pains. In good company But the growing pains can be eased by paying close attention to the many lessons learned from similar programs operating in about 20 countries, including Brazil, Columbia, Ecuador, Jamaica, Nicaragua, Peru and Turkey. The Philippines and Indonesia are the CCT pioneers of Southeast Asia. In a particularly interesting development, 2007 saw the launch of a new CCT program in North America. New York City?s Opportunity NYC is a unique attempt to adapt a successful developing country poverty reduction approach to the context of one of the world?s richest countries, one that still grapples with issues of poverty and social exclusion. The Ahon Pamilyang Pilipino was conceived in 2006 and pilottested in selected provinces in 2007. The government has announced ambitious plans to reach 300,000 poor families in 2008. This is a mere drop in the bucket considering the latest official poverty figures, which estimated that there were 27.5 million poor Filipinos in 2006. These estimates used a poverty line that amounted to about $0.80 per person per day at the time. Poverty levels worsened during the period 2003-2006, and with the current food price crisis the situation does not look likely to improve. Critics say the program, much like giving people fish, will make them dependent on handouts. This misses the crucial point that benefits are tied to health and education conditions designed to benefit the next generation. And the maximum benefit level, P1,400 per month for a family with three school-aged children, is hardly enough to entice a parent to give up work. The National Statistical Coordination Board set the 2007 poverty line for a family of five at P6,195 per month (about $134 at the time). International best practice holds that a poverty-motivated transfer should represent between 20 percent and 40 percent of the poverty line in order to be meaningful to the recipients. At P1,400, the maximum monthly benefit is on the lower end, less than 23 percent of the poverty line. With these benefit levels, the total annual cost for a program covering 300,000 households in the Philippines would be about 0.05 percent its annual gross domestic product. Meeting human development challenges The list of human development challenges in the Philippines is long. Primary education indicators are backsliding. Children are dropping out of school where families can?t afford transportation, uniforms, or school supplies, never mind a nutritious snack. Hunger is a problem on everyone?s minds, particularly given the skyrocketing food prices. Eight women die every day from pregnancy and childbirth-related complications because they don?t get the necessary basic care. Meeting some of the Millennium Development Goals is going to be impossible if concerted efforts are not made. The Ahon Pamilyang Pilipino is a pioneering program that aims to address these challenges headon, and it holds a great deal of promise. D B Me ye sC C Te xp a n s iontolo we rh ighs c ho o ld r opo u tr a t e By Kristine Angeli Sabillo INQUIRER.net MANILA, Philippines The Department of Budget and Management said Sunday the increase in the conditional cash

transfer (CCT) budget is supposed to lower the dropout rate among poor high school students. The expansion of the CCT program is designed to give financial support to in-need high school students, so theyre encouraged to keep at their secondary-school education under the K-12 system and receive their high-school diplomas, said Budget Secretary Florencio Butch Abad in a statement sent to media. Amid mixed views of experts and criticism by various groups, the agency increased the proposed budget for the Pantawid Pamilyang Pilipino Program (4Ps) from P44 billion this year to P62.6 billion in 2014. Of the total 4Ps budget proposed for 2014, P48.3 billion will support the regular CCT program, accounting for 4.3 million of the poorest households nationwide, with up to P1,400 allotted for each family. Meanwhile, the remaining P12.3 billion will be distributed as P500 monthly cash grants to families with children aged 15 to 18. DBM estimated the expanded CCT program will benefit 10.2 million high school students. Without a high school diploma, the job prospects of our youth are severely limited, and this alone is a huge setback for families that are working their way out of poverty. By expanding the CCT, we can help our youth tap into more employment opportunities that will allow them to support themselves and their families in the long-run, Abad said. PHILIPPINE PROGRAM REAPING GOOD RESULTS Ipinakita ng Impact Evaluation ng World Bank (WB) na ang programang Conditional Cash Transfer (CCT) ay strong ang consistent sa pagpapataas ng kalidad ng pamumuhay ng maralitang pamilyang Pilipino, at tinatahak na nito ang pagtupad ng mga layunin lalo na sa larangan ng human development sa pamamagitan ng pamumuhunan sa kalusugan at edukasyon ng mga batang maralita na may edad hanggang 14, pati na ang kababaihan. Ang Impact Evaluation ng WB na ipinatupad sa pakikipagtulungan ng Asian Development Bank at Australian Agency for International Development, pati na rin ang research group na Social Weather Stations, ay ang resulta ng mahigit isang taon na pangangalap ng impormasyon at pag-analisa. Anang WB, ang Pilipinas, sa pamamagitan ng CCT o ang Pantawid Pamilyang Pilipino Program (4Ps), ay nasa mas mainam na posisyon upang matamo sa loob ng tatlong taon ang Millennium Development Goals. Sa ilalim ng progama, tumatanggap ng cash sa kasunduang paaaralin nila ang kanilang mga anak sa mga pampublikong paaralan, magpapa-check up at magpapagamot sa mga health center lalo na yaong mga buntis. Inaasinta ng pamahalaan ang mahigit 4.3 milyong maralitang pamilya pagsapit ng 2016. Hanggang noong Hulyo 1, 2012, ang programa ay mayroong 3,041,152 pamilyang benepisyaryo sa 1,400 lungsod at munisipalidad sa 79 probinsiya sa buong bansa. Pagsapit ng Disyembre 31, 2012, mahigit 321,000 benepisyaryo ang dapat na nakapagtapos sa 4Ps, ngunit ang mga pamilyang ito ay patuloy na aayudahan ng gobyerno sa pamamagitan ng mga programang pangkabuhayan upang gawin silang matatag kapag umalis na sila sa programa. Hangad natin para kina Department of Social Welfare and Development Secretary Corazon J. Soliman, Social Weather Stations President Dr. Mahar Mangahas, World Bank Country Director Motoo Konishi, Asian Development Bank President Haruhiko Kuroda, at Australian Agency for International Development Director-General Peter Baxter, ang tagumpay sa kanilang pagsisikap na mapababa ang kahirapan at mapaangat ang antas ng pamumuhay ng mga Pilipino. CONGRATULATIONS AT MABUHAY!

Wor ldB ankhail scon dition alca shtr an sferpr ogr am By Michelle V. Remo Philippine Daily Inquirer MANILA, PhilippinesThe World Bank Bank said Friday the conditional cash transfer (CCT) program, for which the Philippine government spends a huge amount in monthly subsidies to the poor, is so far proving to be a worthy investment. Citing findings of its recently completed study on the CCT, the World Bank said indicators show favorable developments in the areas of health and education as a result of the subsidies. The report confirms that children [belonging to household] beneficiaries are enrolling and attending schools, with improved health due to regular visits to health stations, and pregnant mothers getting proper care, the World Bank said in a statement. Under the CCT program, the government provides monthly subsidies to selected poor households. Beneficiaries are required to send their children to public schools, and to have the children and the mothers regularly visit public health centers. The objective of the program is to increase school participation rate of children of poor households and to improve health conditions. For 2013, the government has allocated P44.25 billion for the subsidy program. The amount is expected to cover 3.5 million households, each receiving more or less P1,000 a month. One of the findings of the study is that 98 percent of children aged 6 to 11 years old in barangays where the CCT program is implemented are enrolled in schools. This is higher compared with 93 percent for children not belonging to covered barangays. Another finding is that children aged 6 to 14 years old in CCTcovered barangays have higher school attendance rate of 95 to 96 percent. Children of the same ages in barangays not covered by the program registered a school attendance rate of only 91 percent, it said. Moreover, 76 percent of pre-school children in CCT-covered barangays are enrolled in daycare centers. On the other hand, children in the same age group but not covered by the CCT program registered a pre-school enrolment rate of only 65 percent. On the health aspect, the findings showed that 64 percent of mothers covered by the CCT program reported having obtained pre-natal care from public health centers. This is higher than the 54 percent for mothers not covered by the CCT program. Moroever, 85 percent of CCT-covered children aged 6 to 14 years old have undergone deworming compared with the 80 percent of children from children not benefiting from the CCT. The World Bank also said that poor households covered by the program spend 38 percent more on education and 34 percent more on medical expenses than those not covered by the program. This trend indicates a shift in the spending pattern among CCT beneficiaries towards greater investments in health and education for the children, Nazmul Chaudhury, World Banks country sector coordinator for human development, said in the World Bank study titled Philippines Conditional Cash Transfer Program, Impact Evaluation 2012, Given the favorable findings, the World Bank recommends strengthening of the CCT program, such as through an even higher amount of investments in it. 4P s:D i se mpow eringw ome n 4Ps: Disempowering women CWR study While it correctly targeted the poorest of the poor, 4Ps or CCT creates a culture of dependence; and this dependence is disempowering, according to the latest study of the Center for Womens Resources (CWR), a research and training institution. Conducting research studies on women since 1982, CWR has released its latest study on 4Ps (Pantawid Pamilyang Pilipino Program) or Conditional Cash Transfer (CCT). This is the first of a series in monitoring the impact of the program. In the midst of the on -going debate whether the program is alleviating poverty or not, CWR decided

to go directly to the beneficiaries themselves. We want to know their views and the results are interesting, explains CWR executive director Jojo Guan. One hundred women (100), all of whom are parent beneficiaries of the program, participated in a one-on-one interview, conducted from April till mid-July. The respondents are from 18 barangays in the cities of Manila, Pasig, Muntinlupa and Malabon; and from the municipalities in Sorsogon, Camarines Norte, Nueva Vizcaya, Negros and Mindoro. The study explains that while the program has reached out to indigent families, the program has so far been palliative as it did not create jobs or livelihood opportunities for its beneficiaries. A large majority or 59% of the women respondents have no income at all. At best, 4Ps/ CCT has given them money that is being used for the familys everyday needs. Most or 37.7% of the respondents said that they spend the money received for food while 16% allots the cash for health and only 10% for educational needs. The program is a dole out plain and simple. The families go through the motion of having check up at the health center and get certification from the school just to fulfill the requirements of the program, not so much because they believe that having check up or getting education should be a regular family activity. Once the program is stopped, chances are they would again stop visiting the health center and stop sending their children to school in order to help in providing income to the impoverished family, says Cham Perez, CWR senior researcher and sociologist. This observation has been validated by a physician in one of the health centers involved in the CCT program. Requesting anonymity, the doctor reveals that mothers have still a low level of appreciation in going to the health centers because the centers lack medicines and other amenities needed by the indigent families. It is frustrating to prescribe a medicine when you know that the patient could not afford to buy it, the doctor shares. She adds that instead of dole out, the poor can benefit more when there is an increased government budget for free medicines. According to the study, while there is the maximum amount of Php1400 budget per family for a month, the actual distribution and amount received varies. It defeats the objective of being pantawid since there are unexplained varied schedule of distribution and dissimilar cash allotments. Others get lesser while some get the cash in bulk, reveals Perez. There is a perceived arbitrariness or lack of transparency in the process of selection, delisting and deciding on the amount that a family would receive, depending on the performance and attendance of the beneficiaries. The conditionalities like regular attendance to 4Ps meetings so as to avoid deduction reinforces the dependence as the family would drop everything in order to attend the meetings for fear of getting the ire of the donors and being delisted from the list of beneficiaries,says Perez. This dependence is disempowering since it lessens womens self-worth. The dole out makes them feel more indigent who could not complain of the charity they are receiving. It is imposed and so it is not grounded on the real needs of women as revealed in the interviews with the beneficiaries, adds Guan. Eighty-one percent (81%) of the women respondents believe that the long-lasting solution to their impoverished condition is to have a stable job or livelihood, free education for their children, and free medicines for indigents. A mother said: Ilan lang ang Php1400, pandugtong lang; scholarship sa edukasyon para makapagtapos ng pag-aaral na lang sana. Another said: hindi makaka-sustain sa pang araw araw na pangangailangan, livelihood ang kailangan ibigay. And another: Kasi kung ngayon marami nang natatanggal sa listahan at kulang kulang ang binibigay monthly, tapos 5 years lang ang kasunduan namin. Trabaho pa rin sa amin, sariling kayod. Ibigay ng tama ang serbisyo - gamot at iba pa, ilibre na dapat. The initial study has been conducted since April till mid-July, conducting one-on-one interview and informal focus group discussions in selected CCT areas.

(2011, July 27)

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- Alleviating Global Poverty: The Role of Private EnterpriseD'EverandAlleviating Global Poverty: The Role of Private EnterprisePas encore d'évaluation

- Ending Poverty: How People, Businesses, Communities and Nations can Create Wealth from Ground - UpwardsD'EverandEnding Poverty: How People, Businesses, Communities and Nations can Create Wealth from Ground - UpwardsPas encore d'évaluation

- Over The Last Decade or So, Conditional Cash Transfer (CCT) Programs Have Proliferated in LatinDocument3 pagesOver The Last Decade or So, Conditional Cash Transfer (CCT) Programs Have Proliferated in LatinElizabeth AgPas encore d'évaluation

- FMGD Pre-Course Assignment: Krishna Kumari Sahoo UM14029Document4 pagesFMGD Pre-Course Assignment: Krishna Kumari Sahoo UM14029Krishna Kumari SahooPas encore d'évaluation

- Top 10 Solutions to Cut Poverty and Grow the Middle ClassDocument19 pagesTop 10 Solutions to Cut Poverty and Grow the Middle ClassLeilaAviorFernandezPas encore d'évaluation

- ECON 222 Practice Questions on Poverty and Economic Growth ModelsDocument4 pagesECON 222 Practice Questions on Poverty and Economic Growth ModelsDrew NicholasPas encore d'évaluation

- Poverty in the Philippines: Causes and SolutionsDocument4 pagesPoverty in the Philippines: Causes and SolutionsMartin JohnPas encore d'évaluation

- The Cloward-Piven Strategy: The Weight of The Poor-A Strategy To End Poverty-By Cloward & Piven-Pub 2 May 1966Document14 pagesThe Cloward-Piven Strategy: The Weight of The Poor-A Strategy To End Poverty-By Cloward & Piven-Pub 2 May 1966protectourliberty100% (6)

- Economic Development - Chapter 1Document3 pagesEconomic Development - Chapter 1July StudyPas encore d'évaluation

- Indonesian Delegation Commends Philippine CCT Program During Study TourDocument15 pagesIndonesian Delegation Commends Philippine CCT Program During Study TourStephane BacolcolPas encore d'évaluation

- Article 3Document17 pagesArticle 3Tianna Douglas LockPas encore d'évaluation

- Policy Focus: Welfare Reform 2.0Document6 pagesPolicy Focus: Welfare Reform 2.0Independent Women's ForumPas encore d'évaluation

- Conditional Cash Transfer Programs: Assessing Their Achievements and Probing Their PromiseDocument2 pagesConditional Cash Transfer Programs: Assessing Their Achievements and Probing Their PromiseRudi OnoPas encore d'évaluation

- What is poverty and how can it be overcomeDocument6 pagesWhat is poverty and how can it be overcomekatak kembungPas encore d'évaluation

- Why Do The Poor Remain PoorDocument2 pagesWhy Do The Poor Remain PoorJamesPas encore d'évaluation

- Ibon Ccts Position Paper PaperDocument7 pagesIbon Ccts Position Paper PaperJZ MigoPas encore d'évaluation

- Anthropology Group Work - Casa and QuilatonDocument1 pageAnthropology Group Work - Casa and QuilatonWinston QuilatonPas encore d'évaluation

- 4Ps - Case 3Document19 pages4Ps - Case 3Noemie Paula PardoPas encore d'évaluation

- Ref PaperDocument3 pagesRef PaperJaica Mangurali TumulakPas encore d'évaluation

- There Are Two Kinds of Welfare Programs in The United States: ThoseDocument11 pagesThere Are Two Kinds of Welfare Programs in The United States: Thosefaker321Pas encore d'évaluation

- Thesis CCT ProgramsDocument25 pagesThesis CCT ProgramsNerissa Pascua100% (1)

- The American Welfare State How We Spend Nearly $1 Trillion A Year Fighting Poverty - and Fail, Cato Policy Analysis No. 694Document24 pagesThe American Welfare State How We Spend Nearly $1 Trillion A Year Fighting Poverty - and Fail, Cato Policy Analysis No. 694Cato Institute100% (1)

- Through Micro-Enterprise Development and Employment Facilitation Activities That Shall Ultimately Provide A Sustainable Income SourceDocument4 pagesThrough Micro-Enterprise Development and Employment Facilitation Activities That Shall Ultimately Provide A Sustainable Income SourcePatrick RamosPas encore d'évaluation

- SW 3710 5Document7 pagesSW 3710 5api-284002404Pas encore d'évaluation

- The Problem With CCTs and The Opportunism of AkbayanDocument4 pagesThe Problem With CCTs and The Opportunism of AkbayanTeddy CasinoPas encore d'évaluation

- Reduce Poverty Philippines Programs JobsDocument2 pagesReduce Poverty Philippines Programs JobsKate Nicole ParPas encore d'évaluation

- Position PaperDocument1 pagePosition PaperandrewbdPas encore d'évaluation

- Funding Indigenous PeoplesDocument9 pagesFunding Indigenous PeoplesErna Mae AlajasPas encore d'évaluation

- GDP growth and poverty reduction challenges in the PhilippinesDocument30 pagesGDP growth and poverty reduction challenges in the PhilippinesJude Anthony Sambaan NitchaPas encore d'évaluation

- Poverty Line in India Its EvolutionDocument11 pagesPoverty Line in India Its Evolutionkhushbu guptaPas encore d'évaluation

- Why welfare state should be provided selectivelyDocument3 pagesWhy welfare state should be provided selectivelyDev IndraPas encore d'évaluation

- Understanding Poverty Traps and Potential SolutionsDocument1 pageUnderstanding Poverty Traps and Potential SolutionsVaishali GoelPas encore d'évaluation

- KapitDocument1 pageKapitAmria PaternoPas encore d'évaluation

- CSS Essays PDFDocument25 pagesCSS Essays PDFAr NaseemPas encore d'évaluation

- Poverty in America - Essay 3 ProposalDocument6 pagesPoverty in America - Essay 3 Proposalapi-357642398Pas encore d'évaluation

- ScriptDocument2 pagesScriptVaishali GoelPas encore d'évaluation

- Poverty Line in India Its EvolutionDocument11 pagesPoverty Line in India Its EvolutionAnonymous zsx4803Pas encore d'évaluation

- Basic Income Poverty Aff Debate CaseDocument67 pagesBasic Income Poverty Aff Debate CaseNicoPas encore d'évaluation

- Chapter 30 Redistribition of IncomeDocument26 pagesChapter 30 Redistribition of IncomeZuhair Is a nice manPas encore d'évaluation

- Effective Use of Zakat For Poverty Alleviation in Pakistan (Muhammad Arshad Roohani)Document11 pagesEffective Use of Zakat For Poverty Alleviation in Pakistan (Muhammad Arshad Roohani)Muhammad Arshad RoohaniPas encore d'évaluation

- Effectiness of 4PsDocument10 pagesEffectiness of 4PscarloPas encore d'évaluation

- Case Study AnalysisDocument12 pagesCase Study AnalysisVaibhavi Gandhi83% (6)

- Psychology 201 Poverty AnalysisDocument6 pagesPsychology 201 Poverty AnalysisWidimongar W. JarquePas encore d'évaluation

- Population PoliciesDocument7 pagesPopulation PoliciescruellaPas encore d'évaluation

- Mae Lou Fria B. Abarientos Ac16Document2 pagesMae Lou Fria B. Abarientos Ac16charlottevinsmokePas encore d'évaluation

- Poverty Facts and StatsDocument14 pagesPoverty Facts and StatsShibin SuPas encore d'évaluation

- Why Doesn't Aid Work - Cato UnboundDocument9 pagesWhy Doesn't Aid Work - Cato UnboundFiorentina García MiramónPas encore d'évaluation

- There Are Four Reasons To Measure Poverty:: One ApproachDocument6 pagesThere Are Four Reasons To Measure Poverty:: One ApproachHilda Roseline TheresiaPas encore d'évaluation

- EquityDocument5 pagesEquityFrancis AngPas encore d'évaluation

- Poverty and The Middle Class - The Need For Policy AttentionDocument13 pagesPoverty and The Middle Class - The Need For Policy AttentionKrizzia Katrina OcampoPas encore d'évaluation

- Pnoy'S Pantawid Pamilya Program: August 29th, 2011Document2 pagesPnoy'S Pantawid Pamilya Program: August 29th, 2011شزغتحزع ىطشفم لشجخبهPas encore d'évaluation

- Impact of LPG on Marginalized GroupsDocument9 pagesImpact of LPG on Marginalized GroupsRomilModiPas encore d'évaluation

- Dalberg EssayDocument3 pagesDalberg Essayfaith writerPas encore d'évaluation

- Poverty in PhillippinesDocument20 pagesPoverty in Phillippinesalexis macalangganPas encore d'évaluation

- Government Subsidies Can Help Address Problems Faced by Poor CommunitiesDocument4 pagesGovernment Subsidies Can Help Address Problems Faced by Poor CommunitiesAnonymous rfeqISPas encore d'évaluation

- The Freebie Debate: Analyzing Populism, Welfare and India's Growth StoryDocument4 pagesThe Freebie Debate: Analyzing Populism, Welfare and India's Growth StoryGauri GuptaPas encore d'évaluation

- With Reference To Examples, Explain Why Aid Is More Effective in Some Countries Which Receive It Than in Others (AutoRecovered)Document3 pagesWith Reference To Examples, Explain Why Aid Is More Effective in Some Countries Which Receive It Than in Others (AutoRecovered)shahrun abdulghaniPas encore d'évaluation

- COVID-19 Relief Package LetterDocument4 pagesCOVID-19 Relief Package LetterRavi ManglaPas encore d'évaluation

- ECONDocument4 pagesECONAnna ReyesPas encore d'évaluation

- Argument Paper RevisedDocument8 pagesArgument Paper Revisedsamantha chewPas encore d'évaluation

- MAS - First Pre-Board 2014-15 With SolutionsDocument6 pagesMAS - First Pre-Board 2014-15 With SolutionsAj de CastroPas encore d'évaluation

- ToaDocument14 pagesToaAj de CastroPas encore d'évaluation

- BALIUAG UNIVERSITY CPA REVIEW 2014-15 STANDARD COST AND VARIANCE ANALYSISDocument10 pagesBALIUAG UNIVERSITY CPA REVIEW 2014-15 STANDARD COST AND VARIANCE ANALYSISAj de CastroPas encore d'évaluation

- Auditing Problems, Theory of Accounts & Practical Accounting 1 Auditing Problems Theory of Accounts Practical Accounting 1 Audit of CashDocument5 pagesAuditing Problems, Theory of Accounts & Practical Accounting 1 Auditing Problems Theory of Accounts Practical Accounting 1 Audit of CashAj de CastroPas encore d'évaluation

- QuestionnaireDocument1 pageQuestionnaireAj de CastroPas encore d'évaluation

- Accounting Policies, Changes in Accounting Estimates and Errors AND OTHER INCOME Cash Flows and Sme'SDocument1 pageAccounting Policies, Changes in Accounting Estimates and Errors AND OTHER INCOME Cash Flows and Sme'SAj de CastroPas encore d'évaluation

- Baliuag University: It Is Not Enough That We Do Our Best Sometimes We Must Do What Is Required. - Winston ChurchillDocument7 pagesBaliuag University: It Is Not Enough That We Do Our Best Sometimes We Must Do What Is Required. - Winston ChurchillAj de CastroPas encore d'évaluation

- NFJPIA Christmas Photo Contest RulesDocument7 pagesNFJPIA Christmas Photo Contest RulesAj de CastroPas encore d'évaluation

- Financial Instruments NaDocument6 pagesFinancial Instruments NaAj de CastroPas encore d'évaluation

- Direct and Absorption Costing 2014Document15 pagesDirect and Absorption Costing 2014Aj de CastroPas encore d'évaluation

- Chapter I - Definitions SEC. 22. Definitions - When Used in This TitleDocument34 pagesChapter I - Definitions SEC. 22. Definitions - When Used in This TitleAj de CastroPas encore d'évaluation

- Seize A Partner .And Never Be .: RightDocument1 pageSeize A Partner .And Never Be .: RightAj de CastroPas encore d'évaluation

- Auditing Theory - Solution ManualDocument21 pagesAuditing Theory - Solution ManualAj de CastroPas encore d'évaluation

- Persons Who Give Contribution To SociologyDocument4 pagesPersons Who Give Contribution To SociologyAj de Castro100% (1)

- Safeguards in An Accounting EnvironmentDocument2 pagesSafeguards in An Accounting EnvironmentAj de CastroPas encore d'évaluation

- Rizal NotesDocument2 pagesRizal NotesAj de CastroPas encore d'évaluation

- Finish PreDocument2 pagesFinish PreAj de CastroPas encore d'évaluation

- Day 0 and Day 1 schedule for JPIA conferenceDocument4 pagesDay 0 and Day 1 schedule for JPIA conferenceAj de CastroPas encore d'évaluation

- Brief Guidelines and ProceduresDocument5 pagesBrief Guidelines and ProceduresAj de CastroPas encore d'évaluation

- Task Delegation MycDocument2 pagesTask Delegation MycAj de CastroPas encore d'évaluation

- VB CodeDocument7 pagesVB CodeAj de CastroPas encore d'évaluation

- Ccabeg Case Studies Accountants Public PracticeDocument20 pagesCcabeg Case Studies Accountants Public PracticeAj de CastroPas encore d'évaluation

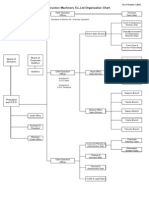

- Itochu Construction Machinery Co.,Ltd Organization Chart: Board of Directors Board of Corporate AuditorsDocument1 pageItochu Construction Machinery Co.,Ltd Organization Chart: Board of Directors Board of Corporate AuditorsAj de CastroPas encore d'évaluation

- NFJPIA Region 3 Council Election RulesDocument10 pagesNFJPIA Region 3 Council Election RulesAj de CastroPas encore d'évaluation

- Multicolore PDFDocument1 pageMulticolore PDFAj de CastroPas encore d'évaluation

- Hybrid Varieties PDFDocument1 pageHybrid Varieties PDFAj de CastroPas encore d'évaluation

- Business Ethics and Social ResponsibilityDocument17 pagesBusiness Ethics and Social ResponsibilityAj de CastroPas encore d'évaluation

- Environmental Accounting Reaction PaperDocument3 pagesEnvironmental Accounting Reaction PaperAj de CastroPas encore d'évaluation

- Estimator PDFDocument4 pagesEstimator PDFAj de CastroPas encore d'évaluation

- Masinag Protocol For Palay PDFDocument1 pageMasinag Protocol For Palay PDFAj de CastroPas encore d'évaluation

- Assessment Template Ass 2Document15 pagesAssessment Template Ass 2Kaur JotPas encore d'évaluation

- Chapter 1Document6 pagesChapter 1Abhee Thegreat80% (5)

- Recipe of A Fantastic IndividualDocument2 pagesRecipe of A Fantastic Individualハーンス アンティオジョーPas encore d'évaluation

- Holding Your Deliverance Win WorleyDocument27 pagesHolding Your Deliverance Win Worleyumesh kumarPas encore d'évaluation

- Certificate-Of-Good-Moral-Character-Autosaved (AutoRecovered)Document7 pagesCertificate-Of-Good-Moral-Character-Autosaved (AutoRecovered)Winie MireraPas encore d'évaluation

- Post Test Session 7 Code of EthicsDocument1 pagePost Test Session 7 Code of EthicsMariel GregorePas encore d'évaluation

- Specpro NotesDocument32 pagesSpecpro NotesSui100% (1)

- Criminal Law Book2 UP Sigma RhoDocument240 pagesCriminal Law Book2 UP Sigma RhorejpasionPas encore d'évaluation

- Nqs PLP e Newsletter No 65 2013 Becoming Culturally Competent - Ideas That Support PracticeDocument4 pagesNqs PLP e Newsletter No 65 2013 Becoming Culturally Competent - Ideas That Support Practiceapi-250266116Pas encore d'évaluation

- Yossi Moff - Unit 1 Lesson 4 - 8th Grade - Reflection Loyalists Vs PatriotsDocument2 pagesYossi Moff - Unit 1 Lesson 4 - 8th Grade - Reflection Loyalists Vs Patriotsapi-398225898Pas encore d'évaluation

- UAP Planning Seminar 2010 Module 1 World PlanningDocument88 pagesUAP Planning Seminar 2010 Module 1 World Planningmark aley solimanPas encore d'évaluation

- Business Ethics and Corporate Social Responsibility. AmayaDocument25 pagesBusiness Ethics and Corporate Social Responsibility. AmayaMary Azeal G. AmayaPas encore d'évaluation

- Binay v. Sandiganbayan Rules on JurisdictionDocument2 pagesBinay v. Sandiganbayan Rules on JurisdictionKing Badong100% (3)

- Covid Letter and Consent FormDocument2 pagesCovid Letter and Consent FormBATMANPas encore d'évaluation

- HR Questions - Set 1Document5 pagesHR Questions - Set 1AANCHAL RAJPUTPas encore d'évaluation

- Cachanosky, N. - CV (English)Document9 pagesCachanosky, N. - CV (English)Nicolas CachanoskyPas encore d'évaluation

- RA 9522 Codal ProvisionsDocument6 pagesRA 9522 Codal ProvisionsFen MarsPas encore d'évaluation

- Abstracts of BOCW ActDocument6 pagesAbstracts of BOCW ActMohanKumarPas encore d'évaluation

- Pacifik Fusion Case Study - MBA 423 - Motivation or Manipulation - Rev 11 - 16 OctDocument30 pagesPacifik Fusion Case Study - MBA 423 - Motivation or Manipulation - Rev 11 - 16 OctHanisevae VisantiPas encore d'évaluation

- Midterm 2 Enculturation and SocializationDocument56 pagesMidterm 2 Enculturation and SocializationMa Kaycelyn SayasPas encore d'évaluation

- (G10) Recollection ModuleDocument4 pages(G10) Recollection ModuleArvin Jesse Santos100% (4)

- Law UrduDocument4 pagesLaw Urduasif aliPas encore d'évaluation

- Critical Reading and Writing For PostgraduatesDocument5 pagesCritical Reading and Writing For PostgraduatesNmushaikwaPas encore d'évaluation

- IsjfnmxfndnDocument5 pagesIsjfnmxfndnJewel BerbanoPas encore d'évaluation

- Exercise No. 5Document1 pageExercise No. 5Princess Therese CañetePas encore d'évaluation

- 1 Rallos vs. Felix Go Chan - Sons Realty Corporation 81 SCRA 251, January 31, 1978 PDFDocument20 pages1 Rallos vs. Felix Go Chan - Sons Realty Corporation 81 SCRA 251, January 31, 1978 PDFMark Anthony Javellana SicadPas encore d'évaluation

- INTL711 Introduction Week 7 Entrepreneurship, Innovation, and Economic Development PDFDocument31 pagesINTL711 Introduction Week 7 Entrepreneurship, Innovation, and Economic Development PDFAnonymous I03Wesk92Pas encore d'évaluation

- B 0018 Goldstein Findley Psychlogical Operations PDFDocument378 pagesB 0018 Goldstein Findley Psychlogical Operations PDFshekinah888Pas encore d'évaluation

- Fighting The Lies of The EnemyDocument10 pagesFighting The Lies of The EnemyKathleenPas encore d'évaluation

- Stages of Change Readiness AddictionsDocument8 pagesStages of Change Readiness AddictionsamaliastoicaPas encore d'évaluation