Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Vermeulen Et Al 1996, Frameprotheses Overleving

Transféré par

costanero12Description originale:

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Vermeulen Et Al 1996, Frameprotheses Overleving

Transféré par

costanero12Droits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Ten-year evaluation of removable partial dentures: Survival rates based on retreatment, not wearing and replacement

A. H. B. M. Vermeulen, DDS, PhD, H. M. A. M. Keltjens, M. A. van% Hof, PhD,b and A. F. Kayser, DDS, PhD

Trikon, Institute for Dental Clinical Nijmegen, Nijmegen, The Netherlands Research, School of Dentistry,

DDS,

University

PhD, of

From a group of 1480 patients, 1036 were treated with metal frame removable partial dentures (RPDs) at least 5 years before this analysis. Of those, 748 patients who wore 886 RPDs were followed up between 5 and 10 years; 288 patients dropped out. The 748 patients in the study groups were wearing 703 conventionally designed metal frame RPDs and 183 RPDs with attachments. When dropout patients and patients who remained in the study were compared, no differences were shown in the variables analyzed, which indicated that the dropouts did not bias the results. Survival rates of the RPDs were calculated by different failure criteria. Taking abutment retreatment as failure criterion, 40% of the conventional RPDs survived 5 years and more than 20% survived 10 years. In RPDs with attachments crowning abutments seemed to retard abutment retreatment. Fracture of the metal frame was found in 10% to 20% of the RPDs after 5 years and in 27% to 44% after 10 years. Extension base RPDs needed more adjustments of the denture base than did tooth-supported base RPDs. Taking replacement or not wearing the RPD as failure criteria, the survival rate was 75% after 5 years and 50% after 10 years (half-life time). The treatment approach in this study was characterized by a simple design of the RPD and regular surveillance of the patient in a recall system. (J &-osthet Dent 1996;76:267-72.)

a major part of the population but still functional dentition. A substantial number of these edentulous portions of the dental arch are not prosthetically restored,l and many patients are functioning with a shortened dental arch without any need for treatment.2 Nevertheless, restoring oral function and appearance is often necessary; there is a particularly higher percentage of replacements in higher economic gr0ups.l Treatment options to replace missing teeth are either fixed or removable appliances; each has its own indication.3 The first reports about removable partial dentures (RPDs) indicated that these restorations could deteriorate the health of remaining dentition and surrounding oral tissues.4,5 Few partial dentures survived for more than 5 to 6 years.6 Other studies demonstrated more favorable results with respect to treatment with RPDs and suggested that the negative effects could be counteracted by a carefully planned prosthetic treatment and regular recall appointments that included patient instruction, retreatments of teeth, and prosthetic adjustments.7-g Studies of the follow-up of a large number of RPDs over an extended period are scarce. This article presents the results of a lo-year longitudinal study of patients (n n many countries has an incomplete

= 748) treated with RPDs and includes 703 conventional metal frame RPDs and 183 RPDs with attachments. By extrapolating survival curves, the efficacy of the treatment and the need for retreatment could be determined.

MATERIAL

Participants

AND METHODS

Assistant thetic bAssociate cProfessor, tistry.

Professor, Dentistry. Professor, Department

Department Department of Oral

of Oral

Function

and

Pros-

of Statistical Function and

Consultation. Prosthetic Den-

The patients for this historic study were recruited from the clinic of the Dental School in Nijmegen, The Netherlands. The total sample consisted of 1480 patients, 68% ofwhom were women. The mean age was 38 years (range 19 to 72 years). Fifty-five patients were treated with an acrylic resin RPD only and were excluded from the study. To ensure a reasonable follow-up time, only those patients who started their treatment at least 5 years before this analysis were selected, resulting in an exclusion of 389 patients. The remaining patients (n = 1036) were treated with a metal frame RPD that could be of a conventional design or provided with attachments. The RPDs were subdivided into extension base and toothsupported base categories. All patients participated in a maintenance program and returned for follow-up at g-month intervals. Patients who did not return for follow-up regularly (288) were considered lost to follow-up, and data of these patients were omitted when they did not return for at least 2 years. The data of the patients were collected by students and checked by staff members. The data collection procedure was explained to the students.

THE JOURNAL OF PROSTHETIC DENTISTRY

SEPTEMBER

1996

267

THE JOURNAL

OF PROSTHETIC

DENTISTRY

VERMEULEN

ET AL

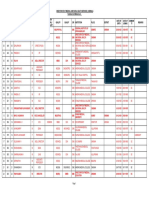

Table I. Survival (% + SD) after 5 and 10 years for conventional (read from survival curves)

Maxilla Failure reason Extension base Tooth-supported base

RPDs (n = 703) according

to different

failure

reasons

Mandible Extension base Tooth-supported base

Initial No. Abutment retreatment 5 10 Adjustment 5 10 RPD fracture 5 10

78 (yr) 38 + 6 23 IL 8

168 41+ 4 22 + 5 82 + 3 55 + 6 89 f 3 73 f 5

338 38 f 3 26 f 4 65 ZL 3 41 f 4 86 + 2 72 + 4

119 38 zt 5 16 + 5 75 f 4 55 f 7 82 + 4 56 + 7

denture

base

(yr) 60 + 6 40 + 9

(yr) 84 + 5 65 f 9

Table II. Survival (% + SD) after 5 and 10 years for RPDs with reasons (read from survival curves)

Maxilla Failure reason Extension base Tooth-supported base

attachments

(n = 183) divided

Mandible

into different

failure

Extension

base

Tooth-supported

base

Original Abutment

No. retreatment

21 (yr) 76 + 10 48 ir 17

20 75 + 11 41+ 18 83+ 9 66 f 17 88+ 8 59 f 18

83 68 zi 6 45 * 9 29 + 5 10 + 5 80 f 5 64 + 8

59 592 7 30 + 10 89+ 4 65 k 10 842 5 63 zk 10

5 10 Adjustment 5 10 RPD fracture 5 10

denture

base

(yr) 72+11 36 + 17

(yr) 84 + 9 -

Criteria

of evaluation

At the start of the study the distribution of the remaining dentition and the dental health was scored with the following standard methods: 1. caries determination with a mirror, explorer, and radiographs, 2. pocket measurement with a pocket probe (Williams, Hu Friedy, Chicago)lO 3. determination of tooth mobility with a 4-point scale,ii and 4. measurement of the alveolar bone height on radiographs. The dentitions were categorized according to the Kennedy Classification. I2 During the recall visits the changes that occurred to the teeth, the restorations, and the RPDs were recorded. Moreover, all retreatment of the RPDs and treatments of the abutment teeth were recorded. To study the survival rates of RPDs, three reasons for failure were distinguished: (1) treatment of the abutment teeth, (2) corrections of the RPD, and (3) replacement of or not wearing the RPD. For the survival analysis on the basis of abutment treatment, the first treatment of one of the abutment teeth marked the mo268

ment of failure. This treatment could be a new restoration or extraction. For situations that required extraction, it could be necessary to adapt the RPD to the new environment. Corrections of the RPD itself could have occurred during the evaluation period. This retreatment consisted of repairing, relining, rebasing, or reconstruction of the RPD. The first retreatment caused by fracture of the appliance or resorption of the alveolar ridge resulting in adjustment of the denture base marked the moment of failure. For these failure reasons, 5- and lo-year survival rates were read from the Kaplan-Meier survival curves (Tables I and II). Some of the earlier mentioned failure reasons 1 and 2 resulted in restorative treatment of the abutment teeth or corrections of the RPDs. However, these RPDs were functioning again after the adjustments had been performed without any problems. Therefore Kaplan-Meier survival curves were calculated, reflecting the percentage of RPDs that were replaced completely or not worn anymore (Fig. 1). In situations that require replacement

VOLUME 76 NUMBER 3

VERMEULEN

ET AL

THE JOURNAL

OF PROSTHETIC

DENTISTRY

CONVENTIONAL RPDs mandible ---j-100 00 extension base II=338 -~--__ - -@- - tooth-supported base n=119 + loo r--T--

CONVENTIONAL RPDs maxilla extension base n=78 -9 - tooth-supported base n=168

60 50

3.

0 12 3 4 5

--L-i6 7

lo

40 L -..L----L--I---L.-L--I

0 12 3 4 5 6 7

i L---l---6 9 10

YEARS RPDs with ATTACHMENTS mandible +

100 so 60 "

YEARS RPDs with ATTACHMENTS maxilla extension base n=21 - -o- - tooth-supported base n=ZCt

30

20

L- L----L

0 12 3 4

___. L.-l _-___ L-'J.---L-..

5 6 7 6 9 10

2n ,o -L---L-A-1-1 0 12 _---- ;-,y 3 d 5 0 IO

YEARS Fig. 1. Survival curves of RPDs on basis of replacement

YEARS and not wearing RPD.

or not wearing the RPD, only the failure reason was scored. Other failure reasons could occur simultaneously.

RESULTS Dropout

Of the 288 dropout patients, 149 (53%) responded to the questionnaire, 129 (45%) did not respond, and 10 (3%) had died. Table III summarizes the reasons for the dropout. The most important reason for not returning for the recall appointments was no time; moving out of the region was another frequent reason. An indication for the dental awareness of the dropout group was the fact that 80% of the responding dropouts were still visiting a dentist regularly. The patients judgment with respect to the result and the procedures of the treatment was included in the questionnaire. Of the dropouts, 88% were satisfied with the result and 96% with the procedure of the treatment. For 5% of the patients dissatisfaction was the primary reason for dropout (Table III). Seven percent of the dropouts did not wear the RPD in the maxilla and 13% in the mandible. In this aspect no difference was found compared to patients remaining in the study group. The dropout groups and study groups were evaluated 269

Dropout

Because 288 patients dropped out and might bias the results of the study, the study group and the dropout group were compared on the basis of seven variables: age, sex, number and type of remaining teeth, number of abutment teeth, type of prosthesis, dental visits, and treatment satisfaction. First, a questionnaire was mailed to all dropout patients. Those who did not respond were called by telephone and requested to answer the questionnaire. The dropouts and study group were matched with respect to the moment of intake in the study, age, sex, and type of prosthesis received. It was only possible to perform this for the dropouts between 25 and 65 years old. Finally, 593 patients of the study group and 248 dropouts remained in the dropout analysis. A three-way analysis of variance (dropout, sex, and age) was applied to the seven mentioned variables.

SEPTEMBER 1936

THE

JOURNAL

OF PROSTHETIC

DENTISTRY

VERMEULEN

ET AL

Table III.

Reason No time

Overview

of reasons

for dropout

%

(a = 149)

for dropout

Moved Prefer another dentist Noncompliance Recall procedure unknown Dissatisfied with treatment No reason

34 29

12 10

5 5 5

with respect to classification and type of prosthesis (Table IV). Analysis of the classification showed that for the mandible the nonresponding dropout group contained significantly more patients with a natural dentition (p = 0.04). Moreover, for the maxilla significantly more patients were included in the study group who were classified as Kennedy I and II (JI = 0.04) (Table IV). Analysis of the type of prosthesis demonstrated that in all dropout groups more patients with a complete denture were included (p = 0.03) (Table IV). As shown in Table V, the clinical variables for the different groups were similar and did not reveal a significant difference between groups. The dropout analysis showed that no serious activity occurred as a result of dropout.

the maxilla after 10 years is not presented because of the low number at risk at that moment. The percentage of RPDs that presented no fracture within 5 years was 80% to 90%; after 10 years the percentages of RPDs with no fracture varied between 56% and 73%. The differences within the groups of conventional RPDs and within the groups of RPDs with attachments were limited. Figure 1 illustrates the Kaplan-Meier survival curves over 10 years for the different RPDs. These curves demonstrated that after 10 years about 50% of all RPDs were still functioning. Extension-base conventional RPDs tended to show lower survival percentages than did tooth-supported base RPDs. For RPDs with attachments in the mandible the survival curves of the extension-base RPDs were less favorable than those with tooth-supported bases. The reason not wearing accounted for 5% of the failures in RPDs with attachments, whereas in conventional RPDs these percentages were 8% for the mandible and 4% for the maxilla.

DISCUSSION

This longitudinal study was conducted on 748 patients with 886 RPDs examined during a 5- to lo-year span. This research was not a controlled clinical trial and therefore some aspects should be interpreted carefully. In particular, when cast restorations were needed on abutments, the choice between a conventionally designed RPD with only crowned abutments or an RPD with attachments was partially dependent on the interest and experience of the staff member and the student. Another phenomenon observed was also the high retreatment need of extension-base RPDs with attachments, leading to a decrease of these restorations in later groups. For these reasons, it is not appropriate to compare the results of RPDs with and without attachments. In the earlier studies caries activity was reported to be high in patients with RPDs.4J3 This study does not support these negative effects. The results of this study are in agreement with those of Bergman et a1.,7 who did not find a marked increase in caries caused by wearing RPDs. In the current study and the study of Bergman et al. patients were kept under surveillance in an active recall system, which was probably responsible for the low caries increase. A recent study by Drake and BeckI demonstrated the importance of patient education, good oral self-care, and regular professional recall for people who wear RPDs. In 40% and 20% of the jaws with conventional RPDs no restorative retreatment of any of the abutment teeth was performed after 5 and 10 years, respectively. Bergman et a1.7 reported 44% of the abutment teeth in need of restorative treatment after 10 years. These percentages give the impression that in this study the results were more unfavorable. It should be considered, however, that the first restorative treatment of one of the abutment teeth was taken as a criterion for faiIure

VOLUME 76 NUMBER 3

Survival

rates

of RPDs

In total, 886 RPDs worn by 748 patients were analyzed: 703 conventional metal frame RPDs (Table I) and 183 with attachments (Table II). The distribution per jaw and the differentiation into extension base and toothsupported base is also given. Most of the RPDs were inserted in the mandible; especially conventional extension-base RPDs constituted the larger part of the total number of RPDs. The number and survival percentages of the RPDs after 5 and 10 years are shown in Tables I and II. By use of the first retreatment of one of the abutment teeth as the criterion for failure, approximately 40% of the conventional RPDs survived 5 years and over 20% survived 10 years (Table I). Between mandible and maxilla or extension-base and tooth-supported base RPDs, only slight differences were noticed. For RPDs with attachments abutment retreatment resulted in 59% to 76% survival after 5 years and 30% to 48% after 10 years. Treatments related to adjustments of the denture base, such as relining, rebasing, or reconstruction, were combined as one cause of failure. A higher percentage of extensionbase RPDs needed an adjustment ofthe denture base within a shorter time than did tooth-supported base RPDs. This phenomenon was found especially in extension-base RPDs with attachments in the mandible (Table II). Another factor of failure was fracture of the RPD. The percentage of extension-base RPDs with attachments in 270

VEFlMEULEN

ET AL

THE JOURNAL

OF PROSTHETIC

DENTISTRY

Table IV. Distribution of study group (n = 593) and dropout prosthesis in maxilla and mandible (in percentages)

Maxilla Study group R Dropout group

group

(n = 248) according

to classification

Mandible

and type of

Study group N-R R

Dropout

group N-R

Edentulous area Complete Kennedy I and II Kennedy III Kennedy IV Natural dentition Type of prosthesis Complete denture Free-end Non free-end No denture

I?, Responding dropout group;

N-R,

28 36 28 3 5 28 19 28 25 nonresponding

32 26 32 5 5 37 13 28 22 dropout group.

25 26 32 7 10 35

10

62 31 3 4

1

69

27

1

51 36 0 13 16 40 22 22

8

54 18 18

27 27

54 24 20

Table

V. Clinical

variables

of study

and dropout

groups

(mean

values)

Dropout group SD, total N-R group

Study

group

(n = 593) R (n = 139) (n = 109)

Total No. of teeth No. of sound teeth No. of abutment teeth Bone height Mobility

R, Responding

16.5

6.2 4.6

16.1

6.3 4.6

17.9

7.2 4.2

92.5

0.17

91.0

0.12

94.3

0.21

4.5 3.0 1.0 8 0.10

Bone height

dropout expressed

group; N-R, nonresponding dropout group. as a percentage of the maximum height of two thirds

root length.

and that most RPDs had several abutments, leading to a higher failure risk per RPD. Moreover, many abutments were filled with plastic filling materials and only one third were crowned, which resulted in a large portion of abutment teeth at risk for retreatment. RPDs with attachments included a varied collection of designs. Most extension-base RPDs were provided with Dolder bars and ball or Dalbo attachments, whereas in the non-free end ones primarily Dolder bars were used.15-17 The survival curves, with the first restorative treatment of an abutment tooth as a criterion for failure, indicated that cast crowns gave a retardation of decay as reported in earlier studies.8J3 The results seemed to be comparable with those of other studies18Jg when the values in this study are reduced to two abutments per jaw. As may be expected, extension-base RPDs, especially in the mandible, needed a higher percentage of adjustments of the denture base. This can be explained by the progression of the resorption in the edentulous parts of the jaw, which was probably intensified by the pressure of the free-end denture base. Bergman et al7 also reported a great number of denture base adjustments af-

ter 10 years in a population that had a large number of extension-base RPDs. Many of the extension-base RPDs were provided with ball attachments, which may be responsible for the unfavorable results of the RPDs with attachments. During the first years of the study the ball attachments were not provided with occlusal rests, resulting in excessive pressure on the alveolar bone and as a consequence a high resorption rate, responsible for the high number of adjustments needed. This problem could be prevented if the ball attachments were supplied with vertical occlusal stops.= Fracture of the RPD was found in 17% after 5 years, increasing to 35% after 10 years. A study of Korber et a1.20 showed a repair percentage of 40% after 5 years, of which 15% was exclusively caused by fracture of metallic parts. Spiekermanr?l reported a clasp fracture percentage of 19% after 4.5 years. In fact, the fracture percentages of RPDs can be considered low considering the high number of casting defects and inaccuracies mentioned in several studies.22,23 When replacement and not wearing of the RPD were 271

SEPTEMBER

1096

THE JOURNAL

OF PROSTHETIC

DENTISTRY

VERMEULEN

ET AL

combined as a criterion for failure, about 50% of the RPDs survived 10 years. This finding is in contrast with the results of Wetherell and Smales,j who reported that only few prostheses lasted for more than 5 to 6 years. Wetherell and Smale@ and Roberts5 reported a large number of RPDs that were not worn. Because of a problem-oriented approach used in this study, a higher percentage of RPDs were worn by the patientsz4 The results of this study are confirmed by Cowan et a1.,25 who reported a high number of patients wearing their RPD several years after insertion without apparent problems.

CONCLUSIONS

Within the limits of this study it was concluded that the survival rate for conventional metal frame RPDs, on the basis of replacement and not wearing, is approximately 75% after 5 years and 50% after 10 years (the socalled half lifetime). The negative effect of an RPD on the remaining teeth can be kept to a minimum. With a simple RPD design and a regular surveillance of the patient in a recall system with an individually adjusted interval, the results of RPD treatment will ensure predictability. REFERENCES

1. Battistuzzi P, Kayser AF, Kanters N. Partial edentulism, prosthetic treatment and oral function in a Dutch population. J Oral Rehabil 1987;14:549-55. 2. Witter DJ, Elteren van P, Kayser AF. Signs and symptoms of mandibular dysfunction in shortened dental arches. J Oral Rehabil 1988;15:413-20. 3. Zarb GA, Bergman B, Clayton JA, MacKay HF. Prosthodontic treatment for partially edentulous patients. 8th ed. St. Louis: Mosby, 1980. 4. Carlsson GE, Hedegard B, Koivumaa KK. Studies in partial dental prosthesis, IV: final results of a 4-year longitudinal investigation of dentogingivally supported partial dentures, Acta Odontol Stand 1965;23:443-72. 5. Roberts BW. A survey of chrome-cobalt partial dentures. N Z Dent J 1978;74:203-9. 6. Wetherell JD, Smales RJ. Partial denture failures: a long term clinical survey. J Dent 1980;8:333-40. 7. Bergman B, Hugoson A, Olsson C. Caries, periodontal and prosthetic findings in patients with removable partial dentures: a ten-year longitudinal study. J Prosthet Dent 1982;48:506-14. 8. Schwalm CA, Smith DE, Erickson JD. A clinical study of patients 1 to 2 years after placement of removable partial dentures. J Prosthet Dent 1977;38:380-91.

9. Rissin L, Feldman RS, Kapur KK, Chauncey HH. Six-year report of the periodontal health of fixed and removable partial denture abutment teeth. J Prosthet Dent 1985;54:461-7. 10. Rateitschak KH, Renggli HH, Muhlemann HR. Parodontologie. 2nd ed. Stuttgart: Thieme, 1978. 11. Caranza FA. Glickmans clinical periodontology. 5th ed. Philadelphia: WB Saunders Co, 1979. 12. Applegate OC. Essentials of removable partial denture prosthesis. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Saunders, 1965. 13. Henrich H, Kerschbaum T. Frequency of caries-related sequelae in the unsupervised use of a removable partial denture [in German]. Dtsch Zahnarztl Z 1980;35:926-30. 14. Drake CW, Beck JD. The oral status of elderly removable partial denture wearers. J Oral Rehabil 1993;20:53-60. 15. Preiskel HW. Precision attachments in dentistry. 3rd ed. St. Louis: Mosby, 1979. 16. Dolder EJ, Durrer GT. The bar-joint denture. Chicago: Quintessence. 1978. 1 7. Owall B. Precision attachment-retained removable partial dentures, Part 2: long-term study of ball attachments. Int J Prosthodont 1995;8:21-8. 1 8. Luzi C. Die steg-geschiebe-prothese: Nachuntersuchungen nach 15ingerer Tragzeit. SSO 1974;84:261-90. 1 9. Lofberg PG, Ericson G, Eliasson S. A clinical and radiographic evaluation of removable partial dentures retained by attachments to alveolar bars. J Prosthet Dent 1982;47:126-32. 20. Korber E, Lehmann K, Pangidis C. Control studies on periodontal and periodontal-gingival retention of partial prosthesis [in German]. Dtsch Zahnarztl Z 1975;30:77-84. 21. Spiekermann H. Follow-up studies on model cast prostheses after 4 years wear [in German]. Dtsch Zahnarztl Z 1975;30:689-91. 22. Eerikainen E, Rantanen T. Inaccuracies and defects in frameworks for removable partial dentures. J Oral Rehabil 1986;13:347-53. 23. Ben-Ur Z, Patael H, Cardash HS, Baharav H. The fracture of cobaltchromium alloy removable partial dentures. Quintessence Int 1986;17:797-801. 24. Kayser AF, Witter DJ, Spanauf AJ. Overtreatment with removable partial dentures in shortened dental arches. Aust Dent J 1987;32:17882. 25. Cowan RD, Gilbert JA, Elledge DA, McGlynn FD. Patient use of removable partial dentures: two- and four-year telephone interviews. J Prosthet Dent 1991;65:668-70. Reprint requests to: DR. H. M. KELTJENS UNIVERSITY OF NIJMEGEN SCHOOL OF DENTISTRY PHILIPS VAN LEY~ENLAAN 25 6525 EX NIJMEGEN THE NETHERLANDS

Copyright0

Prosthetic

1996 by The Editorial

Dentistry.

Council

of The Journal

of

0022-3913/96/$5.00

+ 0. 10/l/74422

272

VOLUME

76

NUMBER

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (895)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5794)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (399)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (73)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (588)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (266)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (344)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1090)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2259)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (120)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)

- D-Ox Benefits of Hydrogen WaterDocument10 pagesD-Ox Benefits of Hydrogen WaterGabi Del RosarioPas encore d'évaluation

- Ramsay Sedation Scale and How To Use ItDocument10 pagesRamsay Sedation Scale and How To Use ItAdinda Putra PradhanaPas encore d'évaluation

- Transferring A Dependent Patient From Bed To ChairDocument5 pagesTransferring A Dependent Patient From Bed To Chairapi-26570979Pas encore d'évaluation

- Pediatrics-AAP Guideline To SedationDocument18 pagesPediatrics-AAP Guideline To SedationMarcus, RNPas encore d'évaluation

- PDP2 Heart Healthy LP TDocument24 pagesPDP2 Heart Healthy LP TTisi JhaPas encore d'évaluation

- Draft HHP Informed Consent FormDocument7 pagesDraft HHP Informed Consent Formapi-589951233Pas encore d'évaluation

- Mental Health Awareness SpeechDocument2 pagesMental Health Awareness SpeechThea Angela Longino95% (20)

- Neurophysiological Effects of Spinal ManipulationDocument15 pagesNeurophysiological Effects of Spinal ManipulationBojan AnticPas encore d'évaluation

- DoctrineDocument1 pageDoctrinevinay44Pas encore d'évaluation

- VPPPA Designing For Construction Safety FINALDocument27 pagesVPPPA Designing For Construction Safety FINALKrischaEverPas encore d'évaluation

- Normative Data For A Spanish Version of The Rey Auditory-Verbal Learning Test in Older PeopleDocument12 pagesNormative Data For A Spanish Version of The Rey Auditory-Verbal Learning Test in Older PeopleeastareaPas encore d'évaluation

- Bellavista 1000 Technical - SpecificationsDocument4 pagesBellavista 1000 Technical - SpecificationsTri DemarwanPas encore d'évaluation

- Model of Decision MakingDocument34 pagesModel of Decision MakingPalalikesjujubesPas encore d'évaluation

- Urbanization and HealthDocument2 pagesUrbanization and HealthsachiPas encore d'évaluation

- ID Faktor Faktor Yang Berhubungan Dengan Perilaku Berisiko Remaja Di Kota MakassarDocument11 pagesID Faktor Faktor Yang Berhubungan Dengan Perilaku Berisiko Remaja Di Kota MakassarEva VidiaPas encore d'évaluation

- Part-IDocument507 pagesPart-INaan SivananthamPas encore d'évaluation

- Graphs CHNDocument24 pagesGraphs CHNiamELHIZAPas encore d'évaluation

- Material Safety Data Sheet: 1 Identification of SubstanceDocument5 pagesMaterial Safety Data Sheet: 1 Identification of SubstanceRey AgustinPas encore d'évaluation

- HB2704IDocument6 pagesHB2704IJENNIFER WEISERPas encore d'évaluation

- Amy L. Lansky - Impossible Cure - The Promise of HomeopathyDocument295 pagesAmy L. Lansky - Impossible Cure - The Promise of Homeopathybjjman88% (17)

- Wu 2008Document8 pagesWu 2008SergioPas encore d'évaluation

- Diare: Dewi RahmawatiDocument20 pagesDiare: Dewi RahmawatiEkwan Prasetyo AzlinPas encore d'évaluation

- Construction of Magic Soak Pit With Locally Available Materials and Economical DesignDocument4 pagesConstruction of Magic Soak Pit With Locally Available Materials and Economical DesignInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyPas encore d'évaluation

- Summary of Wind Turbine Accident Data To 31 December 2016Document6 pagesSummary of Wind Turbine Accident Data To 31 December 2016أحمد دعبسPas encore d'évaluation

- Assessing The Status of Professional Ethics Among Ghanaian RadiographersDocument31 pagesAssessing The Status of Professional Ethics Among Ghanaian Radiographersdeehans100% (1)

- Playlist AssignmentDocument7 pagesPlaylist AssignmentTimothy Matthew JohnstonePas encore d'évaluation

- Secondary Glaucoma IGADocument28 pagesSecondary Glaucoma IGANur JannahPas encore d'évaluation

- MBA Students Habit Toward ToothpasteDocument29 pagesMBA Students Habit Toward ToothpasteSunil Kumar MistriPas encore d'évaluation

- Lymphatic Filariasis in The PhilippinesDocument20 pagesLymphatic Filariasis in The PhilippinesSherlyn Joy Panlilio IsipPas encore d'évaluation

- BECKER, Howard. Marihuana Use and Social ControlDocument11 pagesBECKER, Howard. Marihuana Use and Social ControlDanFernandes90Pas encore d'évaluation