Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

A Welfare Evaluation of East Asian Monetary Policy Regimes Under Foreign Output Shock

Transféré par

Asian Development BankTitre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

A Welfare Evaluation of East Asian Monetary Policy Regimes Under Foreign Output Shock

Transféré par

Asian Development BankDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

A Welfare Evaluation of East Asian Monetary

Policy Regimes under Foreign Output Shock

Joseph D. Alba, Wai-Mun Chia, and Donghyun Park

No. 299 | February 2012

ADB Economics

Working Paper Series

ADB Economics Working Paper Series No. 299

A Welfare Evaluation of East Asian Monetary

Policy Regimes under Foreign Output Shock

Joseph D. Alba, Wai-Mun Chia, and Donghyun Park

February 2012

Joseph D. Alba is Associate Professor, Division of Economics, School of Humanities and Social Sciences,

Nanyang Technological University, Singapore. Wai-Mun Chia is Assistant Professor, Division of Economics,

School of Humanities and Social Sciences, Nanyang Technological University. Donghyun Park is Principal

Economist, Macroeconomics and Finance Research Division, Economics and Research Department,

Asian Development Bank.

Asian Development Bank

6 ADB Avenue, Mandaluyong City

1550 Metro Manila, Philippines

www.adb.org/economics

2012 by Asian Development Bank

February 2012

ISSN 1655-5252

Publication Stock No. WPS124675

The views expressed in this paper

are those of the author(s) and do not

QHFHVVDULO\UHHFWWKHYLHZVRUSROLFLHV

of the Asian Development Bank.

The ADB Economics Working Paper Series is a forum for stimulating discussion and

eliciting feedback on ongoing and recently completed research and policy studies

undertaken by the Asian Development Bank (ADB) staff, consultants, or resource

persons. The series deals with key economic and development problems, particularly

WKRVHIDFLQJWKH$VLDDQG3DFLFUHJLRQDVZHOODVFRQFHSWXDODQDO\WLFDORU

methodological issues relating to project/program economic analysis, and statistical data

and measurement. The series aims to enhance the knowledge on Asias development

DQGSROLF\FKDOOHQJHVVWUHQJWKHQDQDO\WLFDOULJRUDQGTXDOLW\RI$'%VFRXQWU\SDUWQHUVKLS

VWUDWHJLHVDQGLWVVXEUHJLRQDODQGFRXQWU\RSHUDWLRQVDQGLPSURYHWKHTXDOLW\DQG

availability of statistical data and development indicators for monitoring development

effectiveness.

7KH$'%(FRQRPLFV:RUNLQJ3DSHU6HULHVLVDTXLFNGLVVHPLQDWLQJLQIRUPDOSXEOLFDWLRQ

ZKRVHWLWOHVFRXOGVXEVHTXHQWO\EHUHYLVHGIRUSXEOLFDWLRQDVDUWLFOHVLQSURIHVVLRQDO

journals or chapters in books. The series is maintained by the Economics and Research

Department.

Printed on recycled paper

Contents

Abstract v

I. Introduction 1

II. Role of Monetary and Exchange Rate Policies

in Cushioning External Shocks 4

III. The Model 5

A. Households 5

B. Domestic Firms 7

C. Price Level, Terms of Trade, and Real Exchange Rate 8

D. Monetary Policy and Exchange Rate Regimes 9

E. Welfare 9

F. Model Parameterization 10

IV. Simulation Results and Welfare 11

A. Impulse Responses under Various Monetary Policy Regimes 11

B. Welfare Losses under Various Monetary Policies 16

C. Summary of Simulation Results and Welfare 19

V. Conclusions 20

References 22

Abstract

Adverse foreign output shocks have a sizable impact on the welfare of small

open economies. Therefore, one of the key roles of monetary policy in those

economies is to minimize the welfare losses arising from such shocks. To

assess the welfare impact of external shocks under different monetary policy

regimes, we numerically solve and calculate the welfare loss function of a

G\QDPLFVWRFKDVWLFJHQHUDOHTXLOLEULXPPRGHOZLWKFRPSOHWHH[FKDQJHUDWHSDVV

WKURXJK:HQGWKDWFRQVXPHUSULFHLQGH[&3,LQDWLRQWDUJHWLQJPLQLPL]HV

welfare losses for import-to-gross domestic product (GDP) ratios from 0.3 to 0.9.

+RZHYHUZHOIDUHXQGHUWKHSHJJHGH[FKDQJHUDWHUHJLPHLVDOPRVWHTXLYDOHQW

WR&3,LQDWLRQWDUJHWLQJZKHQWKHLPSRUWWR*'3UDWLRLVZKLOHWKHGRPHVWLF

LQDWLRQWDUJHWLQJPLQLPL]HVZHOIDUHZKHQWKHLPSRUWWR*'3UDWLRLV:H

calibrate the model and derive welfare implications for eight East Asian small

open economies.

I. Introduction

Adverse foreign output shocks have a sizable impact on the macroeconomic performance

of small open economies. For example, the sharp recession of the advanced economies

GXHWRWKHJOREDOQDQFLDODQGHFRQRPLFFULVLVRIKDGDSURQRXQFHGHIIHFWRQ

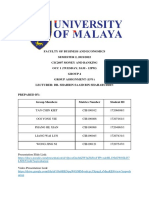

the export and growth of East Asias highly open, export-dependent economies. Table 1

shows the cumulative contraction in real gross domestic product (GDP) growth, relative

WRWUHQGRIWRIRU6LQJDSRUH7DLSHL&KLQDDQG+RQJ.RQJ&KLQD)RU

WKH5HSXEOLFRI.RUHD0DOD\VLDWKH3KLOLSSLQHVDQG7KDLODQGLWZDVWR

7DEOHFRQUPVWKDWWKHSULPDU\FKDQQHOIRUWKHWUDQVPLVVLRQRIWKHJOREDOFULVLVWR(DVW

Asia was the trade channel. The cumulative contraction of real export growth ranged

from 5.96% for Indonesia to 38.78% for Thailand. It is not surprising that exports have

a large impact on the real GDP of East Asian economies in light of their heavy export

GHSHQGHQFH7KHUDWLRRIH[SRUWVWR*'3HYHQH[FHHGVLQ+RQJ.RQJ&KLQD

0DOD\VLDDQG6LQJDSRUH

In light of their large effect on the macroeconomic outcomes of small open economies,

we can expect adverse foreign output shocks to have a large effect on their welfare.

Therefore, one of the key roles of monetary policy in those economies is to minimize

the welfare losses arising from such shocks. Table 1 shows the various monetary and

H[FKDQJHUDWHSROLF\UHJLPHVDGRSWHGE\(DVW$VLDQHFRQRPLHV+RQJ.RQJ&KLQDDQG

6LQJDSRUHKDYH[HGDQGSHJJHGH[FKDQJHUDWHUHJLPHVUHVSHFWLYHO\ZKLOHWKH5HSXEOLF

RI.RUHD,QGRQHVLDWKH3KLOLSSLQHVDQG7KDLODQGKDYHDGRSWHGLQDWLRQWDUJHWLQJ

policies. Malaysia and Taipei,China aim to do both, i.e., stabilize prices and intervene in

WKHIRUHLJQH[FKDQJHUDWHPDUNHWV(FRQRPLHVWKDWWDUJHWH[FKDQJHUDWHV+RQJ.RQJ

&KLQD6LQJDSRUHDQG7DLSHL&KLQDVKRZHGORZHUDYHUDJHFKDQJHVLQH[FKDQJHUDWHV

WKDQFRXQWULHVWKDWWDUJHWLQDWLRQ,QGRQHVLDWKH5HSXEOLFRI.RUHDWKH3KLOLSSLQHV

and Thailand.

1

The exception is Malaysia, which target both variables but experienced

DQDYHUDJHFKDQJHLQH[FKDQJHUDWHFORVHUWRLQDWLRQWDUJHWLQJFRXQWULHV,QDGGLWLRQ

economies that target the exchange rate suffered a visibly larger cumulative decline in

UHDO*'3FRPSDUHGWRHFRQRPLHVWKDWWDUJHWLQDWLRQ,QDWLRQKDVEHHQJHQHUDOO\ORZIRU

all economies regardless of policy regimes.

2

1

Hong Kong, China; Singapore; and Taipei,China experienced the smallest average percentage change in exchange

rates of 0.42%, 3.01%, and 3.98%, respectively. In contrast, Indonesia, the Republic of Korea, the Philippines, and

Thailand experienced an average percentage change in exchange rates in the range of 6.92% to 27.16%. Malaysia,

which targets both exchange rate and infation but experienced an average change in exchange rate of 6.90%,

which is closer to infation-targeting countries, is an exception.

2

In fact, Indonesia and Thailand experienced defation.

T

a

b

l

e

1

:

S

e

l

e

c

t

e

d

E

c

o

n

o

m

i

c

I

n

d

i

c

a

t

o

r

s

o

f

S

m

a

l

l

O

p

e

n

E

c

o

n

o

m

i

e

s

i

n

E

a

s

t

A

s

i

a

E

c

o

n

o

m

y

C

u

m

u

l

a

t

i

v

e

C

h

a

n

g

e

i

n

R

e

a

l

G

D

P

G

r

o

w

t

h

(

%

)

A

v

e

r

a

g

e

C

h

a

n

g

e

i

n

C

P

I

I

n

f

a

t

i

o

n

(

%

)

A

v

e

r

a

g

e

C

h

a

n

g

e

i

n

E

x

c

h

a

n

g

e

R

a

t

e

(

%

)

C

u

m

u

l

a

t

i

v

e

C

h

a

n

g

e

i

n

R

e

a

l

E

x

p

o

r

t

G

r

o

w

t

h

(

%

)

P

e

r

c

e

n

t

a

g

e

o

f

E

x

p

o

r

t

o

v

e

r

G

D

P

P

e

r

c

e

n

t

a

g

e

o

f

I

m

p

o

r

t

o

v

e

r

G

D

P

M

o

n

e

t

a

r

y

P

o

l

i

c

y

(

2

0

0

8

)

N

e

w

l

y

I

n

d

u

s

t

r

i

a

l

i

z

i

n

g

C

o

u

n

t

r

i

e

s

H

o

n

g

K

o

n

g

,

C

h

i

n

a

1

3

.

0

8

0

.

3

8

0

.

4

2

1

8

.

4

0

1

5

8

.

6

0

1

7

2

F

i

x

e

d

e

x

c

h

a

n

g

e

r

a

t

e

u

n

d

e

r

t

h

e

c

u

r

r

e

n

c

y

b

o

a

r

d

K

o

r

e

a

,

R

e

p

.

o

f

7

.

6

5

1

.

3

2

2

7

.

1

6

1

5

.

6

2

3

6

.

2

0

3

9

I

n

f

a

t

i

o

n

t

a

r

g

e

t

i

n

g

S

i

n

g

a

p

o

r

e

1

1

.

8

2

.

0

3

3

.

9

8

1

0

.

5

1

2

1

5

.

0

5

1

9

1

P

e

g

g

e

d

t

o

a

b

a

s

k

e

t

o

f

c

u

r

r

e

n

c

i

e

s

T

a

i

p

e

i

,

C

h

i

n

a

1

2

.

0

4

0

.

1

4

3

.

0

1

2

3

.

0

0

5

3

.

4

6

4

0

A

i

m

s

f

o

r

s

t

a

b

l

e

p

r

i

c

e

s

a

n

d

i

n

t

e

r

v

e

n

e

s

i

n

t

h

e

f

o

r

e

i

g

n

e

x

c

h

a

n

g

e

m

a

r

k

e

t

A

S

E

A

N

4

I

n

d

o

n

e

s

i

a

1

.

1

1

2

.

5

5

9

.

1

7

5

.

9

6

3

1

.

5

4

2

7

I

n

f

a

t

i

o

n

t

a

r

g

e

t

i

n

g

M

a

l

a

y

s

i

a

7

.

3

2

0

.

2

1

6

.

9

2

2

0

.

3

4

1

0

2

.

2

4

9

0

A

i

m

s

f

o

r

s

t

a

b

l

e

p

r

i

c

e

s

a

n

d

s

t

a

b

l

e

e

f

e

c

t

i

v

e

e

x

c

h

a

n

g

e

r

a

t

e

P

h

i

l

i

p

p

i

n

e

s

7

.

4

9

1

.

7

7

1

2

.

2

8

1

9

.

9

9

4

2

.

8

8

4

8

I

n

f

a

t

i

o

n

t

a

r

g

e

t

i

n

g

T

h

a

i

l

a

n

d

8

.

2

6

1

.

1

1

7

.

6

1

3

8

.

7

8

5

7

.

6

1

6

4

I

n

f

a

t

i

o

n

t

a

r

g

e

t

i

n

g

B

e

n

c

h

m

a

r

k

:

U

S

6

.

7

2

1

.

2

9

1

1

T

a

y

l

o

r

r

u

l

e

A

S

E

A

N

4

=

I

n

d

o

n

e

s

i

a

,

M

a

l

a

y

s

i

a

,

t

h

e

P

h

i

l

i

p

p

i

n

e

s

,

a

n

d

T

h

a

i

l

a

n

d

;

C

P

I

=

c

o

n

s

u

m

e

r

p

r

i

c

e

i

n

d

e

x

;

G

D

P

=

g

r

o

s

s

d

o

m

e

s

t

i

c

p

r

o

d

u

c

t

;

U

S

=

U

n

i

t

e

d

S

t

a

t

e

s

.

N

o

t

e

:

W

e

c

o

n

s

i

d

e

r

t

h

e

f

r

s

t

q

u

a

r

t

e

r

o

f

2

0

0

8

a

s

t

h

e

b

e

n

c

h

m

a

r

k

d

a

t

e

o

f

t

h

e

2

0

0

8

f

n

a

n

c

i

a

l

c

r

i

s

i

s

.

W

e

f

o

l

l

o

w

B

l

a

n

c

h

a

r

d

a

n

d

G

a

l

i

(

2

0

0

7

)

i

n

c

a

l

c

u

l

a

t

i

n

g

t

h

e

c

u

m

u

l

a

t

i

v

e

c

h

a

n

g

e

i

n

r

e

a

l

G

D

P

g

a

i

n

o

r

l

o

s

s

o

v

e

r

e

i

g

h

t

q

u

a

r

t

e

r

s

f

o

l

l

o

w

i

n

g

b

e

n

c

h

m

a

r

k

d

a

t

e

r

e

l

a

t

i

v

e

t

o

t

h

e

t

r

e

n

d

g

i

v

e

n

b

y

t

h

e

c

u

m

u

l

a

t

i

v

e

r

e

a

l

G

D

P

g

r

o

w

t

h

r

a

t

e

o

v

e

r

t

h

e

p

r

e

c

e

d

i

n

g

e

i

g

h

t

q

u

a

r

t

e

r

s

.

T

h

e

c

h

a

n

g

e

i

n

C

P

I

i

n

f

a

t

i

o

n

(

n

a

t

i

o

n

a

l

c

u

r

r

e

n

c

y

t

o

U

S

d

o

l

l

a

r

)

i

s

t

h

e

a

v

e

r

a

g

e

r

a

t

e

o

f

i

n

f

a

t

i

o

n

(

d

e

p

r

e

c

i

a

t

i

o

n

o

r

a

p

p

r

e

c

i

a

t

i

o

n

)

i

n

e

i

g

h

t

q

u

a

r

t

e

r

s

f

o

l

l

o

w

i

n

g

e

a

c

h

o

f

t

h

e

b

e

n

c

h

m

a

r

k

d

a

t

e

m

i

n

u

s

t

h

e

a

v

e

r

a

g

e

i

n

f

a

t

i

o

n

(

d

e

p

r

e

c

i

a

t

i

o

n

o

r

a

p

p

r

e

c

i

a

t

i

o

n

)

r

a

t

e

o

v

e

r

t

h

e

e

i

g

h

t

q

u

a

r

t

e

r

s

i

m

m

e

d

i

a

t

e

l

y

f

o

l

l

o

w

i

n

g

t

h

e

b

e

n

c

h

m

a

r

k

d

a

t

e

.

A

p

o

s

i

t

i

v

e

(

n

e

g

a

t

i

v

e

)

s

i

g

n

i

n

t

h

e

f

o

u

r

t

h

c

o

l

u

m

n

i

n

d

i

c

a

t

e

s

t

h

e

d

e

p

r

e

c

i

a

t

i

o

n

(

a

p

p

r

e

c

i

a

t

i

o

n

)

o

f

t

h

e

n

a

t

i

o

n

a

l

c

u

r

r

e

n

c

y

a

g

a

i

n

s

t

t

h

e

U

S

d

o

l

l

a

r

.

M

u

r

r

a

y

,

N

i

k

o

l

s

k

o

R

z

h

e

v

s

k

y

y

,

a

n

d

P

a

p

e

l

l

(

2

0

0

8

)

a

r

g

u

e

t

h

a

t

t

h

e

U

S

F

e

d

e

r

a

l

R

e

s

e

r

v

e

f

o

l

l

o

w

e

d

t

h

e

T

a

y

l

o

r

p

r

i

n

c

i

p

l

e

f

r

o

m

1

9

8

5

2

0

0

9

.

E

x

c

h

a

n

g

e

r

a

t

e

i

s

d

e

f

n

e

d

a

s

n

a

t

i

o

n

a

l

c

u

r

r

e

n

c

y

p

e

r

U

S

d

o

l

l

a

r

.

S

o

u

r

c

e

s

:

A

l

l

q

u

a

r

t

e

r

l

y

d

a

t

a

a

r

e

f

r

o

m

C

E

I

C

D

a

t

a

o

n

E

m

e

r

g

i

n

g

M

a

r

k

e

t

s

e

x

c

e

p

t

f

o

r

e

x

p

o

r

t

a

n

d

i

m

p

o

r

t

a

s

a

p

e

r

c

e

n

t

a

g

e

o

f

G

D

P

,

w

h

i

c

h

a

r

e

f

r

o

m

t

h

e

W

o

r

l

d

D

e

v

e

l

o

p

m

e

n

t

I

n

d

i

c

a

t

o

r

s

o

n

l

i

n

e

(

A

u

g

u

s

t

2

0

1

1

)

.

W

h

e

n

a

v

a

i

l

a

b

l

e

,

s

e

a

s

o

n

a

l

l

y

a

d

j

u

s

t

e

d

r

e

a

l

G

D

P

a

r

e

u

s

e

d

.

I

n

f

o

r

m

a

t

i

o

n

o

n

c

o

u

n

t

r

i

e

s

t

h

a

t

t

a

r

g

e

t

i

n

f

a

t

i

o

n

a

r

e

f

r

o

m

T

r

u

m

a

n

(

2

0

0

3

)

e

x

c

e

p

t

f

o

r

I

n

d

o

n

e

s

i

a

,

w

h

i

c

h

i

s

f

r

o

m

t

h

e

B

a

n

k

o

f

I

n

d

o

n

e

s

i

a

w

e

b

s

i

t

e

.

I

n

f

o

r

m

a

t

i

o

n

o

n

t

h

e

m

o

n

e

t

a

r

y

p

o

l

i

c

y

o

f

S

i

n

g

a

p

o

r

e

i

s

f

r

o

m

t

h

e

M

o

n

e

t

a

r

y

A

u

t

h

o

r

i

t

y

o

f

S

i

n

g

a

p

o

r

e

w

e

b

s

i

t

e

.

I

n

f

o

r

m

a

t

i

o

n

o

n

t

h

e

m

o

n

e

t

a

r

y

p

o

l

i

c

i

e

s

o

f

M

a

l

a

y

s

i

a

a

n

d

T

a

i

p

e

i

,

C

h

i

n

a

a

r

e

f

r

o

m

t

h

e

E

c

o

n

o

m

i

c

I

n

t

e

l

l

i

g

e

n

t

U

n

i

t

s

2

0

0

8

C

o

u

n

t

r

y

R

e

p

o

r

t

s

.

2 | ADB Economics Working Paper Series No. 299

The central objective of this paper is to evaluate and compare the welfare impact of

H[WHUQDOVKRFNVXQGHUGLIIHUHQWPRQHWDU\DQGSROLF\UHJLPHV0RUHVSHFLFDOO\ZHORRNDW

the welfare effects of foreign output shocks under seven different types of monetary and

H[FKDQJHUDWHSROLF\UHJLPHVD[HGRUSHJJHGH[FKDQJHUDWHUXOHDFRQVXPHUSULFH

LQGH[&3,LQDWLRQWDUJHWLQJUXOHLQDWLRQDQGH[FKDQJHUDWHWDUJHWLQJUXOHGRPHVWLF

LQDWLRQWDUJHWLQJ7D\ORUW\SHUXOHQRPLQDORXWSXWWDUJHWLQJDQGUHDORXWSXWWDUJHWLQJ

:HGRVRIRUHLJKWVPDOORSHQHFRQRPLHVLQ(DVW$VLD+RQJ.RQJ&KLQD,QGRQHVLD

WKH5HSXEOLFRI.RUHD0DOD\VLDWKH3KLOLSSLQHV6LQJDSRUH7DLSHL&KLQDDQG7KDLODQG

to assess and compare the extent to which each monetary and exchange rate policy

regime protects each of the eight economies from external shocks. Our welfare evaluation

is based on numerically solving and calculating the welfare loss function of a dynamic

VWRFKDVWLFJHQHUDOHTXLOLEULXP'6*(PRGHO:HFDOLEUDWHWKHPRGHOWRGHULYHZHOIDUH

implications for the eight countries.

Our paper is broadly similar with Alba, Su, and Chia (2011) in its methodology. More

precisely, the two papers both use a model that is broadly based on Monacellis (2004)

DSGE model of a small open economy. However, Alba, Su, and Chia (2011) examine the

impact of a negative foreign output shock on the volatility of macroeconomic variables

under alternative monetary and exchange rate policy regimes while we examine the

more fundamental, policy-relevant issue of the impact of such a shock on welfare. While

macroeconomic volatility is important, it is a much less complete yardstick for evaluating

policy regimes than welfare. Furthermore, the analysis of Alba, Su, and Chia (2011) is

OLPLWHGWRWKUHHSROLF\UHJLPHVDQGIRXUFRXQWULHV7KHLUPDLQQGLQJLVWKDWVPDOORSHQ

HFRQRPLHVWKDWIROORZHLWKHU[HGH[FKDQJHUDWHRULQDWLRQWDUJHWLQJWHQGWRVWDELOL]H

UHDOH[FKDQJHUDWHDQGLQDWLRQEXWDWWKHH[SHQVHRIVXEVWDQWLDOYRODWLOLW\LQWKHUHDO

economy.

Our paper evaluates and compares the welfare losses of foreign output shocks under

alternative monetary and exchange rate policy regimes, and is thus able to inform us

about the relative desirability of different policy regimes. Such a welfare comparison is

useful for determining the optimal monetary and exchange rate policy regime in East

Asias small open economies that are highly dependent on trade and hence vulnerable

WRIRUHLJQRXWSXWVKRFNV7KHSURQRXQFHGLPSDFWRIWKHUHFHVVLRQLQWKH

DGYDQFHGHFRQRPLHVLVDYLYLGUHPLQGHURIWKLVYXOQHUDELOLW\7KHFHQWUDOTXHVWLRQZH

seek to answer is the following: which monetary and exchange rate policy regime leaves

East Asian small open economies best off under external shocks? The rest of this paper

is organized as follows. Section II explores the relationship between monetary and

H[FKDQJHUDWHSROLF\UHJLPHVDQGPDFURHFRQRPLFSHUIRUPDQFH6HFWLRQ,,,VSHFLHVRXU

model. Section IV reports and discusses the main results, and Section V concludes the

paper.

A Welfare Evaluation of East Asian Monetary Policy Regimes under Foreign Output Shock | 3

II. Role of Monetary and Exchange Rate Policies

in Cushioning External Shocks

The current crisis calls for a re-examination of macroeconomic policies in general and

PRQHWDU\DQGH[FKDQJHUDWHSROLFLHVLQSDUWLFXODU6WLJOLW]DUJXHVWKDWLQDWLRQ

targeting is inappropriate, especially for emerging economies where energy and

commodities make up a larger share of the household budget compared to industrialized

countries. Other economists have suggested alternative monetary policy targets such as

nominal GDP.

3

In addition, Blanchard, DellAriccia, and Mauro (2010) argue that there

PD\EHDFDVHIRUWKHHPHUJLQJPDUNHWFHQWUDOEDQNHUVSUDFWLFHRIWDUJHWLQJLQDWLRQ

ZKLOHDOVRLQWHUYHQLQJLQWKHIRUHLJQH[FKDQJHPDUNHWV'HVSLWHWKHFULWLFLVPRILQDWLRQ

WDUJHWLQJGH&DOYDOKR)LOKRQGVWKDWLQDWLRQWDUJHWLQJFRXQWULHVRXWSHUIRUPHG

QRQLQDWLRQWDUJHWLQJFRXQWULHVLQWKHSRVWSHULRG+HDUJXHVWKDWGXULQJWKHFULVLV

LQDWLRQWDUJHWLQJFRXQWULHVORZHUHGQRPLQDOLQWHUHVWUDWHVE\PRUHUHVXOWLQJLQHYHQ

larger real interest rate differentials and thus an even stronger monetary stimulus.

The theoretical and empirical literature also suggest a number of rationales for why

different monetary and exchange rate policy regimes may differ in their capacity to protect

FRXQWULHVIURPH[WHUQDOVKRFNV)RUH[DPSOHLWLVRIWHQDUJXHGWKDWFRXQWULHVZLWKH[LEOH

exchange rate regimes can better insulate their economies from negative real shocks.

4

In a study that is highly relevant to the transmission of foreign output shocks to East Asia

GXULQJWKHFULVLV+RIIPDQQXVHVGDWDIURPDVDPSOHRIGHYHORSLQJ

FRXQWULHVWRWHVWWKHK\SRWKHVLVWKDWH[LEOHH[FKDQJHUDWHVVHUYHDVDVKRFNDEVRUEHU

in small open economies, and mitigate the impact of external shocks more effectively

WKDQ[HGH[FKDQJHUDWHUHJLPHV+RIIPDQQGVWKDWFRXQWULHVZLWKPRUHH[LEOH

nominal exchange rates suffer smaller decline of real GDP. This is due to real exchange

rate depreciation, which improves external competitiveness and thus partly offsets the

negative impact of foreign output shocks.

In this paper, we evaluate and compare the welfare loss due to foreign output shocks in

East Asias small open economies under alternative monetary and exchange rate policy

regimes. To do so, we develop a simple DSGE model that contains a goods market

characterized by imperfect competition and nominal rigidities.

5

We numerically solve and

calculate the welfare loss function of the DSGE model under seven types of monetary

DQGH[FKDQJHUDWHSROLF\UHJLPHVD[HGRUSHJJHGH[FKDQJHUDWHUXOHD&3,LQDWLRQ

WDUJHWLQJUXOHLQDWLRQDQGH[FKDQJHUDWHWDUJHWLQJUXOHGRPHVWLFLQDWLRQWDUJHWLQJ

3

A debate on nominal GDP targeting among economists could be accessed online at http://economistsview.

typepad.com/economistsview/2010/12/bernanke-and-mishkin-on-nominal-gdp-growth-targeting.html

4

Please refer to Friedman (1953), Mundell (1961), Poole (1970), Dornbusch (1980), Lufer (1994), Obstfeld and

Rogof (2000), Devereux (2004), Devereux, Lane, and Xu (2006), Broda (2004), Edwards and Levy Yeyati (2005), and

Hofman (2007).

5

There is a large and growing literature on open economy DSGE models that incorporate imperfect competition

and nominal rigidities. Obstfeld and Rogof (1995 and 1996) initiated open-economy macroeconomics research

based on a synthesis of dynamic intertemporal approaches and sticky-price models of macroeconomic

fuctuations. This synthesis is known as the new open economy macroeconomics. Many economists have relied on

this new class of models to address many classical problems with new tools, and to generate new research ideas

and questions.

4 | ADB Economics Working Paper Series No. 299

Taylor-type rule, nominal output targeting, and real output targeting. The open economy

framework makes it possible to examine the exchange rate channel in the transmission of

foreign output shocks to the domestic economy. We assume foreign output shocks to be

exogenous.

0DQ\'6*(PRGHOVFRQVLGHURQO\WZRIDFWRULQSXWV,QFRQWUDVWZHIROORZ.LPDQG

Loungani (1992) and assume oil to be an input in a constant elasticity of substitution

(CES) production function where oil and capital are substitutes. Hence, our model

captures an important stylized fact of global energy use, i.e., more developed economies

use less energy per unit of capital than less developed economies. In addition, it is

possible that exchange rate depreciation affects the price of imported oil which, in turn,

affects domestic output. We follow Monacelli (2004) and assume that capital is subject

to adjustment costs. Each monetary and exchange rate policy regime implicitly assigns

GLIIHUHQWZHLJKWVRQRYHUDOOLQDWLRQGRPHVWLFLQDWLRQWKHRXWSXWJDSDQGH[FKDQJHUDWH

in the interest rate rule. By explicitly evaluating and comparing the welfare loss due to

foreign output shocks under different types of monetary policy regimes, we address the

extent to which different policy regimes mitigate the loss of welfare.

III. The Model

In this section, we lay out our model, which is broadly based on Monacellis (2004) DSGE

PRGHORIDVPDOORSHQHFRQRP\,GHQWLFDODQGLQQLWHO\OLYHGKRXVHKROGVHDUQLQFRPH

IURPZRUNLQJIRUDQGUHQWLQJSK\VLFDOFDSLWDOWRGRPHVWLFUPV7KH\FRQVXPHEDVNHWVRI

differentiated domestic and foreign tradable goods.

A. Households

The domestic economy is populated by a continuum RILQQLWHO\OLYHGLGHQWLFDO

households. They consume baskets of differentiated domestic and foreign goods that

are both tradable and indexed by j. The baskets of domestic and foreign varieties

of goods are associated with utility-based price indices

P P j dj

H t H t , ,

( )

( )

1

0

1

11

0

0

and

P P j dj

F t F t , ,

( )

( )

1

0

1

11

0

0

, respectively, where the H is the index for home and F for

foreign. The price indices are expressed in units of domestic currency.

P j

H t ,

( )

and

P j

F t ,

( ) are prices of the individual domestic and foreign good j, respectively, where

0 >1

is the elasticity of substitution between varieties within each category. The utility-based

consumer price index is given by P P P

t H t F t

- ( ) ( )

, ,

/

1 1

1 1

1 .

A Welfare Evaluation of East Asian Monetary Policy Regimes under Foreign Output Shock | 5

In each period, the households optimally allocate their expenditure on differentiated goods

within each category. The demand functions are:

C j

P j

P

C C j

P j

P

H t

H t

H t

H t F t

F t

F t

,

,

,

, ,

,

,

( )

( )

; ( )

( )

0

C

F t ,

(1)

for all j goods within the interval of 0 and 1, where the goods are produced

E\DFRQWLQXXPRIUPVDQGWKHUPVDUHRZQHGE\GRPHVWLFKRXVHKROGV

C C j dj

H t H t , ,

( )

( )

0 0

0 0

1

0

1

1

and

C C j dj

F t F t , ,

( )

( )

0 0

0 0

1

0

1

1

are composite indices of

domestic and foreign goods, respectively. The households consume a CES composite of

both home products (C

H

) and foreign products (C

F

):

C C C

t H t F t

- ( )

( )

1 1

1

1

1

1

, ,

(2)

where e [0,1] is the share of home-produced goodsLQWRWDOFRQVXPSWLRQVR)

represents the share of foreign-produced goods. > 1 is the elasticity of substitution

between domestic and foreign goods. Investment composite index

In In In

t H t F t , ,

,

( ) has

an identical expression as consumption for simplicity. The optimal allocation of any

given expenditure between domestic and foreign goods yields the consumption demand

C

P

P

C C

P

P

C

H t

H t

t

t F t

F t

t

t ,

,

,

,

; ( )

1

.

The representative domestic household maximizes the utility function over time:

E

C N

t

t t t

t

1 1

0

1 1

-

(3)

where o > 0 and > 0, | is the discount factor and

| ( ) 0 1 ,

. 1/ o is the intertemporal

elasticity of substitution and is the elasticity of labor substitution. E

t

is the expectation

operator. C

t

is the consumption and N

t

is the labor supply of the representative household

at time t.

The representative household holds securities denominated in domestic currency, rents

RXWLWVFDSLWDOWRWKHKRPHEDVHGPRQRSROLVWLFFRPSHWLWLYHUPDQGGHULYHVLQFRPHIURP

working for each time t. Hence, the households budget constraint is written as:

P C In B WN Z K B

t t t t t

h

t t t t t t t

t

- ( ) - ( ) - - -

- -

-

, 1 1

1

(4)

where B

t -1

is the portfolio of state contingent securities household holds at the end of

t, v

t t , -1

LVGHQHGE\0RQDFHOOLDVWKHSULFLQJNHUQHORIVWDWHFRQWLQJHQWSRUWIROLR

HTXDOWRv

-

( ) h h

t t 1

where Monacelli lets h h h

t

t

( ,...., )

0

be the history of events up to

period t and the date 0 probability of observing h

t

LVGHQHGDVd

t

where at the initial

6 | ADB Economics Working Paper Series No. 299

state d h ( )

0

1 0RQDFHOOLGHQHVWKHH[SHFWDWLRQRSHUDWRU

E d h h

t

h

t t

t

. ( ) {

-

-

1

1

. W

t

is

the nominal wage, Z

t

is the nominal rental cost, and t

t

represents the lump-sum transfer

payment.

Following Monacelli, capital accumulation is described as:

K K

In

K

K

t t

t

t

t -

( ) -

1

1 o (5)

where o is the physical depreciation rate of capital. u(.) is an increasing and concave

function that assumes the adjustment cost in capital accumulation. Hence, In

t

units of

investment translate into In K K

t t t

( )

units of additional capital.

With the arbitrage condition holding, it implies that

1

1

1

R

t

t t

h

t

-

-

v

,

and

1

1

1

1

R

t

t t

h

t

t t

* ,

-

-

-

given that

R

t

and

R

t

*

are expected returns in terms of domestic and foreign currency on

the bond portfolio.

6

0RQDFHOOLHTXDOL]HVWKHVHUHWXUQVWRJHW

t t t t

t

t

h

R R

t

,

*

[ ]

-

-

-

1

1

1

0

The rest of the world is assumed to have foreign households with similar preferences

as the home country so that foreign demand for home produced good j is

C j

P j

P

C

P j

P

H t

H t

H t

H t

H t

H t

,

,

,

,

,

,

( )

( )

( )

0 00

C

H t ,

where C

P

P

C

H t

H t

t

t ,

,

( )

.

B. Domestic Firms

Labor, capital, and oil are inputs to production described by the constant elasticity of

substitution CES production function. Oil is included in the CES function following Alba,

Su, and Chia (2011).

7

7KHUHLVDFRQWLQXXPRIPRQRSROLVWLFDOO\FRPSHWLWLYHUPVZKLFK

are indexed by

j [ ] 0 1 , . The CES production function with constant return to scale has

WKHIROORZLQJVSHFLFDWLRQ

Y j A K j O j N j

t t t t t

( ) ( ) - ( ) ( )

( )

( )

1 1

1 1

1

( ) /

(6)

where

0 1 < < o

,

i > 0

and

u > 0

. The elasticity of substitution between capital and

RLOLVHTXDOWR 1/v while labor share in production is given by o.

6

R

t

= 1 + i

t

where i

t

is the nominal interest rate.

7

For details, please refer to Alba, Su, and Chia (2011). Similarly, Backus and Crucini (2000) and Kim and Loungani

(1992) nest capital and oil as a CES function within a Cobb-Douglas production function while Rotemberg and

Woodford (1996) and Blanchard and Gali (2007) consider oil and labor as inputs to production. Alternatively, Finn

(2000) assumes oil and capital as complimentary. The complemetarity or substitutability of oil and capital are

unresolved in empirical literature. For a survey of the literature, please refer to Apostolakis (1990). In addition,

Bodenstein, Erceg, and Guerrieri (2008) consider oil as part of household consumption while Aoki (2001) examines

the relationship between sector-specifc supply shocks such as oil price shocks and infation fuctuations.

A Welfare Evaluation of East Asian Monetary Policy Regimes under Foreign Output Shock | 7

Monacelli (2004) follows Calvos (1983) pricing. A fraction

1-|

p

RIDOOUPVDGMXVWVWKHLU

SULFHVUDQGRPO\ZKLOHWKHUHVWRIWKHUPV|

p

, do not adjust their prices. The parameter

|

p

represents the degree of nominal rigidity whereby a larger |

p

LPSOLHVIHZHUUPV

adjusting their prices, causing a longer expected time between price adjustments. Firms

IXWXUHSURWVDWt+k are affected by the choice of price at time tRQO\LIWKHUPGRHVQRW

get another opportunity to adjust its price between t and t+k.

|

p

k

LVWKHSUREDELOLW\RIDUP

not adjusting its price from t to t+k7KHGRPHVWLFUPj will set price P

H t

New

,

to maximize the

SURWIXQFWLRQ

E P j MC j Y j

t

k

p

k

t t k H t

new

t k

k

t k

, , - -

-

( ) ( )

( )

0

(7)

subject to the domestic and foreign demand given by

Y j

P j

P

C C

t k

H t

new

H t k

H t k H t k -

-

- -

( )

( )

,

,

, ,

0

where

t t k , -

LVWKHWLPHYDU\LQJSRUWLRQRIWKHUPVGLVFRXQWIDFWRU+HQFHWKHRSWLPDO

pricing condition is:

P j

E MC j Y j

H t

new

t

k

p

k

t t k t k t k

k

,

,

( )

( ) ( )

- - -

1

0

( )

- -

E Y j

t

k

p

k

t t k t k

k

,

0

(8)

7KHDERYHHTXDWLRQGHVFULEHVWKHG\QDPLFPDUNXSIRUSULFHVHWWLQJ:KHQWKHSULFH

signal |

p

HTXDOV]HURHTXDWLRQEHFRPHV P j MC

H t

new

t ,

( ) ( ) 0 0 1 . With symmetric

HTXLOLEULXPWKHGRPHVWLFDJJUHJDWHSULFHLQGH[LV

P P P

H t p H t p H t

new

, , ,

-

( ) ( )

( )

1

1

1

11

1 (9)

C. Price Level, Terms of Trade, and Real Exchange Rate

The nominal exchange rate H

t

is the price of one unit of foreign currency in terms of

domestic currency. Assuming the law of one price holds, P P

H t t H t , ,

c and P P

F t t F t , ,

c . The

terms of trade, S

t

LVGHQHGDVWKHSULFHRIWKHLPSRUWHGJRRGUHODWLYHWRWKHSULFHRIWKH

domestic good (

S

P

P

P

P

t

F t

H t

t F t

H t

,

,

,

,

c

). The real exchDQJHUDWHLVWKHQGHQHGDV c

c

t

r t t

t

P

P

.

For a small open economy, domestic price changes do not affect the foreign price level.

So without loss of generality, we assume that

P P

F t t ,

, where the foreign price level

is determined by the prices of non-oil goods and oil. Hence, it can be expressed as

8 | ADB Economics Working Paper Series No. 299

P P P

t NO t O t

no no

( ) ( )

, ,

1

. For simplicity, we normalize P

NO t ,

-

to one so the foreign non-oil

LQDWLRQS

NO t ,

-

LV]HUR7KHWRWDO&3,LQDWLRQLVGHQHGDVS

t t t

P P ( )

log

1

and the

GRPHVWLFLQDWLRQLVGHQHGDVS

H t H t H t

P P

, , ,

log

( )

1

.

D. Monetary Policy and Exchange Rate Regimes

)ROORZLQJ0RQDFHOOLGHYLDWLRQVRILQDWLRQRXWSXWDQGQRPLQDOH[FKDQJHUDWH

from their long-run target have feedback effects on short-run movements of the nominal

interest rate target given by:

1

1

1

-

( )

i

P

P

Y

t

t

t

t t

y

(10)

where

i

t

LVWKHLQDWLRQWDUJHWDQG

,

y

and

are weights assigned to the movements

RI&3,LQDWLRQRXWSXWDQGQRPLQDOH[FKDQJHUDWHUHVSHFWLYHO\5DWKHUWKDQ&3,

LQDWLRQHTXDWLRQFRXOGEHPRGLHGWRFRQVLGHUGRPHVWLFLQDWLRQZKHUHLQDWLRQ

could be written as

P P

H t H t

H

, ,

( )

1

, where

H

LVWKHZHLJKWRQGRPHVWLFLQDWLRQ7KH

actual short-run interest rate is determined based on the monetary authoritys desire to

smooth changes in the nominal interest rate:

1 1 1

1

1

- ( ) -

( )

- ( )

i i i

t t t

_

_

(11)

The exogenous stochastic processes for the foreign output, foreign interest rate,

domestic technology, and nominal oil price can be summarized as:

Y Y

t t t

y

y

* *

*

exp

( )

1

,

1 1

1

-

( )

-

( ) ( )

i i

t t t

i

i

* * *

*

exp

,

A A

t t t

a

a

( )

1

exp

and

P P

O t O t t

po

po

,

*

,

*

exp

( ) ( )

1

, respectively.

8

E. Welfare

We analyze the impact of various monetary policy regimes based on social welfare loss

function minimized by the central banks. The function is based on the second-order

Taylor expansion of the households utility around the steady state as in Rotemberg and

Woodford (1998 and 1999) and Woodford (2003), and extended to small open economies

by Chung, Jung, and Yang (2007) and Divino (2009). The social welfare loss function is

derived as in Walsh (2010) and could be expressed as:

{ }

| t

=

= O +

_

2 2

0

0

( )

flexible

t t t t

t

W E y y (12)

8

The frst order conditions, the steady state and market equilibrium, and the log-linearized equations are available

from the authors upon request.

A Welfare Evaluation of East Asian Monetary Policy Regimes under Foreign Output Shock | 9

where

( )

( )

-

( )

1

2 1 1

1 2

U C

C

p

p p

( )

( )

- ( )

- ( )

1 1

1

p p

p

, and

flexible

t

y is obtained by setting the probability of nonadjustment in price,

p

, close to zero.

We set the inverse of elasticity of intertemporal substitution, o, and the elasticity of

substitution between home and foreign produced goods, HTXDOWRIROORZLQJ*DOLDQG

0RQDFHOOL7KH\VKRZWKDWXVLQJWKLVVSHFLFDWLRQWRJHWKHUZLWKWKHDVVXPSWLRQV

of purchasing power parity and uncovered interest parity, the combined effects of

PDUNHWSRZHUDQGWHUPVRIWUDGHGLVWRUWLRQVFRXOGEHRIIVHWVRWKDWXQGHUH[LEOHSULFH

HTXLOLEULXPGRPHVWLFLQDWLRQWDUJHWLQJLVWKHRSWLPDOPRQHWDU\SROLF\(TXDWLRQ

measures welfare loss as a second order approximation to the utility loss of the domestic

consumer resulting from deviations from optimal monetary policy. Following Lucas (1987),

DOWHUQDWLYHPRQHWDU\SROLFLHVDUHVSHFLHGLQWKHFRQWH[WRIDVLPSOH'6*(PRGHODQG

the welfare losses are compared to draw policy implications.

F. Model Parameterization

The model is solved numerically and parameterized following Monacelli (2004).

9

The

marginal disutility of work effort is set to 3. As common in the Calvo (1983) pricing

models, the probability of price nonadjustment, |, is set at 0.75. The steady-state

markup, 0 / (0 HTXDOVWR7KHODERUVKDUHRIRXWSXWHTXDOV7KHHODVWLFLW\RI

investment rate to the price of capital q HTXDOV

The monetary policy regime parameters are set as follows: The interest rate smoothing

parameter, _, is 0.5. e

c

IRU[HGRUSHJJHGH[FKDQJHUDWHZKLOHe

c

= 0.1 for

H[LEOHH[FKDQJHUDWH8QGHUWKHH[LEOHH[FKDQJHUDWHUHJLPHWKHFHQWUDOEDQNFRXOG

FKRRVHWRWDUJHWRQO\&3,LQDWLRQVRe

t

= 1.5 and e

y

RURQO\GRPHVWLFLQDWLRQVXFK

that e

tH

= 1.5 and e

y

RUFKRRVHWRIROORZWKH7D\ORUUXOHVRe

t

= 1.5 and e

y

or target nominal output and set e

t

= 1.5 and e

y

= 1.5 or real output and set e

t

= 0 and

e

y

7KHFHQWUDOEDQNFRXOGDOVRWDUJHW&3,LQDWLRQDQGH[FKDQJHUDWHDQGVHW

e

t

= 1.5, e

y

= 0 and e

c

= 0.8.

As in Alba, Su, and Chia (2011), the parameters of the serial correlation of the oil price

shocks (

y*

), foreign interest rate (

i*

), foreign output (

y*

), and technology (

a

) are set

to 0.90. The degrees of the impact of oil price on the foreign price level (

NO

HTXDOV

IRUDSRVLWLYHRLOSULFHVKRFNDQGIRUDQHJDWLYHRLOSULFHVKRFN7KHVHUHHFW

the asymmetric effect of oil price shocks.

10

These asymmetric effects also imply that

DSRVLWLYHRLOSULFHVKRFNKDVVLJQLFDQWHIIHFWRQPDUJLQDOFRVWZKLOHDQHJDWLYHRLO

price shock has negligible effect on marginal cost. The share of capital relative to oil in

production (i) is 0.90. The standard deviations from the steady state of oil price (

P

o

-

) of

9

The numerical solution of the model is described in Uhlig (1997).

10

For example, Chen, Finney, and Lai (2005) fnd empirical evidence that gasoline prices in the US respond quickly to

a crude oil price increase but not to a decrease.

10 | ADB Economics Working Paper Series No. 299

foreign nominal interest rate (

i

*

) and of technology (

a

) are set at 1%. The standard

GHYLDWLRQRIIRUHLJQRXWSXWIURPWKHVWHDG\VWDWHLVVHWWRRYHURQHSHULRG

The inverse of the elasticity of substitution between oil and capital, u, is calculated

from the expression of the steady state of the oil to capital ratio as a function of

the parameters u, o, |, and i.

11

:HIROORZ.LPDQG/RXQJDQLLQVHWWLQJWKH

depreciation rate, o,HTXDOVWRDQGWKHGLVFRXQWUDWH|HTXDOVWR7KH

share of oil relative to capital stock, (1i), is 0.10. Given these parameter values, u is

FDOFXODWHGEDVHGRQDYHUDJHHQHUJ\WRFDSLWDOUDWLRRIIRU,QGRQHVLDIRUWKH

3KLOLSSLQHVIRU0DOD\VLDIRU7KDLODQGIRUWKH5HSXEOLFRI.RUHD

IRU6LQJDSRUHIRU+RQJ.RQJ&KLQDIRU7DLSHL&KLQDDQGIRUWKH8QLWHG

States (US), which is our benchmark country. These values are used to calculate u of 9.3

IRU,QGRQHVLDIRUWKH3KLOLSSLQHVIRU0DOD\VLDIRU7KDLODQGIRUWKH5HSXEOLF

RI.RUHDIRU6LQJDSRUHIRU+RQJ.RQJ&KLQDIRU7DLSHL&KLQDDQG

for the US.

12

7KHHVWLPDWHVIRUWKH86DUHFRPSDUDEOHWR.LPDQG/RXQJDQLVVHWWLQJ

of uHTXDOVWRDQGDQHODVWLFLW\RIVXEVWLWXWLRQRIIRUWKH86$VDSUR[\IRUWKH

SDUDPHWHURQWKHSURSRUWLRQRIIRUHLJQJRRGVLQWRWDOFRQVXPSWLRQ), we use imports

over GDP of East Asian countries as shown in Table 1.

IV. Simulation Results and Welfare

In this section, we report and discuss our simulation results, including estimates of

welfare losses under alternative monetary policy regimes.

A. Impulse Responses under Various Monetary Policy Regimes

7KHVLPXODWHGLPSXOVHUHVSRQVHVLQ)LJXUHVUHSUHVHQWWKHG\QDPLFUHVSRQVHVRI

UHDORXWSXWLQDWLRQWHUPVRIWUDGHQRPLQDOUDWHVDQGUHDOH[FKDQJHUDWHVXQGHUVHYHQ

PRQHWDU\SROLF\UHJLPHV[HGRUSHJJHGH[FKDQJHUDWHUHJLPHVWULFW&3,LQDWLRQ

WDUJHWLQJH[FKDQJHUDWHDQG&3,LQDWLRQWDUJHWLQJWKH7D\ORUUXOHVWULFWGRPHVWLF

LQDWLRQWDUJHWLQJQRPLQDO*'3WDUJHWLQJDQGUHDO*'3WDUJHWLQJ

11

The steady-state capitaloil ratio is given by

K

O

Z

( )

1

, where

Z -

1

1

, which is the steady-

state rental cost of capital. The details of the derivation are available from the authors upon request.

12

Data on energy use in kiloton of oil equivalent (KOE) and gross capital formation are from the World Economic

Indicators for Hong Kong, China; Indonesia; the Republic of Korea; Malaysia; Philippines; Singapore; and the US.

Data for Taipei,China are from the CEIC Database. We calculate energy use by multiplying energy use in KOE by the

average price of a kiloton of crude oil in 2000 US dollars. We use the CPI to convert energy use in 2000 US dollars

to 1985 international dollars in relation to the US. Data on CPI and the price of crude oil are from the International

Financial Statistics online.

A Welfare Evaluation of East Asian Monetary Policy Regimes under Foreign Output Shock | 11

Figure 1: Impulse Responses to a Negative Shock in Foreign Output

Figure 5: Under Fixed/Pegged Exchange Rate

33

0.5

0.4

0.3

0.2

0.1

0

0.1

0.2

0.3

1 3 5 7 9 11 13 15 17 19 21 23 25 27 29 31 33

Terms of trade Domestic infation

CPI infation Nominal exchange rate

Real exchange rate Output

Source: Authors' estimates.

Figure 2: Impulse Responses to a Negative Shock in Foreign Output

Figure 5: Under CPI Infation Targeting

0.5

0.4

0.3

0.2

0.1

0

0.1

0.2

0.3

1 3 5 7 9 11 13 15 17 19 21 23 25 27 29 31 33

Terms of trade Domestic infation

CPI infation Nominal exchange rate

Real exchange rate Output

CPI = consumer price index.

Source: Authors' estimates.

12 | ADB Economics Working Paper Series No. 299

Figure 3: Impulse Responses to a Negative Shock in Foreign Output

Figure 5: Under Exchange Rate and CPI Infation Targeting

0.5

0.4

0.3

0.2

0.1

0

0.1

0.2

0.3

1 3 5 7 9 11 13 15 17 19 21 23 25 27 29 31 33

Terms of trade Domestic infation

CPI infation Nominal exchange rate

Real exchange rate Output

CPI = consumer price index.

Source: Authors' estimates.

Figure 4: Impulse Responses to a Negative Shock in Foreign Output

Figure 5: Under Taylor Rule

0.4

0.3

0.2

0.1

0

0.1

0.2

0.3

0.4

0.5

1 3 5 7 9 11 13 15 17 19 21 23 25 27 29 31 33

Terms of trade Domestic infation

CPI infation Nominal exchange rate

Real exchange rate Output

CPI = consumer price index.

Source: Authors' estimates.

A Welfare Evaluation of East Asian Monetary Policy Regimes under Foreign Output Shock | 13

Figure 5: Impulse Responses to a Negative Shock in Foreign Output

Figure 5: with Domestic Infation Targeting

0.4

0.3

0.2

0.1

0

0.1

0.2

0.3

1 3 5 7 9 11 13 15 17 19 21 23 25 27 29 31 33

Terms of trade Domestic infation

CPI infation Nominal exchange rate

Real exchange rate Output

CPI = consumer price index.

Source: Authors' estimates.

Figure 6: Impulse Responses to a Negative Shock in Foreign Output

Figure 5: with Nominal GDP Targeting

0.4

0.2

0

0.2

0.4

0.6

0.8

1

1 3 5 7 9 11 13 15 17 19 21 23 25 27 29 31 33

Terms of trade Domestic infation

CPI infation Nominal exchange rate

Real exchange rate Output

CPI = consumer price index, GDP = gross domestic product.

Source: Authors' estimates.

14 | ADB Economics Working Paper Series No. 299

Figure 7: Impulse Responses to a Negative Shock in Foreign Output

Figure 5: with Real GDP Targeting

0.2

0

0.2

0.4

0.6

0.8

1

1.2

1 3 5 7 9 11 13 15 17 19 21 23 25 27 29 31 33

Terms of trade Domestic infation

CPI infation Nominal exchange rate

Real exchange rate Output

CPI = consumer price index, GDP = gross domestic product.

Source: Authors' estimates.

$QHJDWLYHIRUHLJQRXWSXWVKRFNKDVWKHELJJHVWLPSDFWRQGRPHVWLFRXWSXWXQGHU[HGRU

SHJJHGH[FKDQJHUDWHUHJLPHIROORZHGE\&3,LQDWLRQDQGH[FKDQJHUDWHWDUJHWLQJ&3,

LQDWLRQWDUJHWLQJGRPHVWLFLQDWLRQWDUJHWLQJ7D\ORUW\SHUXOHQRPLQDO*'3WDUJHWLQJ

and the least under real GDP targeting. For a 1% decline in foreign output, real output

GHFOLQHVIURPLWVVWHDG\VWDWHE\XQGHU[HGH[FKDQJHUDWHUHJLPHXQGHU

&3,LQDWLRQFXPH[FKDQJHUDWHWDUJHWLQJXQGHU&3,LQDWLRQWDUJHWLQJ

XQGHUGRPHVWLFLQDWLRQWDUJHWLQJXQGHU7D\ORUUXOHDQGXQGHUQRPLQDO

RXWSXW8QGHUUHDORXWSXWWDUJHWLQJLWULVHVE\LQWKHUVWSHULRGEHIRUHGHFOLQLQJE\

0.08%.

The mitigated effect on real output under real and nominal output targeting and to a

lesser extent, Taylor-type rule, could be explained by the large and sharp depreciation

in the nominal exchange rate following a negative foreign output shock. In the period

following the 1% negative foreign output shock, nominal exchange rate depreciates

from the steady state value by 0.64% for real output targeting, 0.35% for nominal output

targeting, and 0.24% for Taylor-type rule. In turn, the large exchange rate depreciation

LQFUHDVHVWKHSULFHVRIRLODQGRWKHULPSRUWVFDXVLQJKLJKHUWRWDO&3,LQDWLRQ/LNHZLVH

H[SHFWDWLRQVRIKLJKHULQDWLRQDQGIXUWKHUGHSUHFLDWLRQUDLVHWKHQRPLQDOLQWHUHVWUDWH

The impact on the nominal interest rate is shown in Figure 8 where a 1% negative

foreign output shock increases nominal interest rate by 0.41%, 0.11%, and 0.08% from

the steady state for nominal output targeting, real output targeting, and Taylor-type rule,

respectively. In contrast, nominal exchange rate depreciates only by 0.08%, 0.02%,

A Welfare Evaluation of East Asian Monetary Policy Regimes under Foreign Output Shock | 15

DQGIRU&3,LQDWLRQGRPHVWLFLQDWLRQDQG&3,LQDWLRQFXPH[FKDQJHUDWH

WDUJHWLQJUHVSHFWLYHO\7KLVOHDGVWRDUHGXFWLRQRI&3,LQDWLRQIURPLWVVWHDG\VWDWH

E\IRU&3,LQDWLRQWDUJHWLQJIRUSHJJHGH[FKDQJHUDWHUHJLPHDQG&3,

LQDWLRQDQGH[FKDQJHUDWHWDUJHWLQJDQGIRUGRPHVWLFLQDWLRQWDUJHWLQJWZR

periods after the shock. Hence, nominal interest rate in Figure 8 shows a decline from

VWHDG\VWDWHYDOXHVRIDQGIRU&3,LQDWLRQGRPHVWLFLQDWLRQ

DQG&3,LQDWLRQFXPH[FKDQJHUDWHWDUJHWLQJUHVSHFWLYHO\7KHQRPLQDOLQWHUHVWUDWH

hardly changes under pegged exchange rate regime. The impulse responses clearly show

DWUDGHRIIEHWZHHQORZHURXWSXWYRODWLOLW\DQGKLJKHULQDWLRQDQGQRPLQDOLQWHUHVWUDWH

volatility.

Figure 8: Impulse Responses of Interest Rate to a Negative Foreign

Figure 5: Output Shock Under Various Monetary Policies

0.1

0.08

0.06

0.04

0.02

0

0.02

0.04

0.06

0.08

0.1

1 3 5 7 9 11 13 15 17 19 21 23 25 27 29 31 33

Pegged exchange rate Taylor-type rule

CPI infation targeting Domestic infation targeting

CPI infationexchange rate targeting Nominal output targeting

CPI = consumer price index.

Source: Authors' estimates.

B. Welfare Losses under Various Monetary Policies

We examine the impact of various monetary policies after a negative foreign output

shock using a welfare loss function described in Section II, G and shown in Table 2

with the model parameters of oil-to-capital ratio of 0.25 and import-to-GDP ratio of 0.5

taken as average values for East Asian countries. The results show from least to most

ZHOIDUHORVVHVDVFRPSDUHGZLWKWKHRSWLPDOPRQHWDU\SROLF\DUHDVIROORZV&3,LQDWLRQ

WDUJHWLQJ&3,LQDWLRQFXPH[FKDQJHUDWHWDUJHWLQJSHJJHGH[FKDQJHUDWHUHJLPH

GRPHVWLFLQDWLRQWDUJHWLQJ7D\ORUW\SHUXOHQRPLQDORXWSXWWDUJHWLQJDQGUHDORXWSXW

16 | ADB Economics Working Paper Series No. 299

WDUJHWLQJ:LWKFRPSOHWHSDVVWKURXJK&3,LQDWLRQWDUJHWLQJGHOLYHUVWKHOHDVWZHOIDUH

loss under negative foreign output shock.

Table 2: Welfare Loss after a Negative Foreign Output Shock

Table 2: under Diferent Monetary Policies

Monetary Policy

Weights in the Interest Rate Rule Welfare

Loss

Fixed /pegged exchange rate regime 0 0 0 0.99 2.35

CPI infation targeting 1.5 0 0 0.1 0.71

Exchange rate and infation targeting 1.5 0 0 0.8 1.91

Taylor-type rule 1.5 0 0.5 0.1 10.13

Domestic infation targeting 0 1.5 0 0.1 3.69

Nominal output targeting 1.5 0 1.5 0.1 49.25

Real output targeting 0 0 1.5 0.1 122.14

CPI = consumer price index, GDP = gross domestic product.

Note: Welfare loss is calculated based on the average percentage of imports over real GDP of 50% for the six East Asian countries

excluding Hong Kong, China and Singapore, which have percentage imports over GDP of 172% and 191%, respectively. The

average oil-to-capital ratio is 0.25 and the average elasticity of substitution of oil-to-capital is 3.14, excluding the Philippines

and Indonesia, which have an average oil-to-capital (elasticity of substitution of oil for capital) of 0.58 (7.8) and 0.90 (9.3),

respectively. In the model, the import to GDP is (1) equals 0.5 while the elasticity of substitution of oil and capital is .

,

H

,

y

, and

are the weights on overall infation, domestic infation, output gap, and exchange rate in the interest rate

rule equation.

1

in which optimal monetary policy under fexible price equilibrium is domestic infation targeting

as in Gali and Monacelli (2005).

Source: Authors' estimates.

Since there are large variations in import-to-GDP ratio among East Asian countries, we

FRQGXFWVHQVLWLYLW\DQDO\VLVEDVHGRQWKLVUDWLRUHSUHVHQWHGE\WKHSDUDPHWHU

This is the proportion of import in household consumption in the model. Table 3 shows

the estimates of welfare losses due to a 1% negative output shock for various ratios

of import-to-GDP given an oil-to-capital ratio of 0.25 under different monetary policy

UHJLPHV7KHUHVXOWVVKRZWKDWIRUDQHFRQRP\ZLWKLPSRUWWR*'3UDWLRRI&3,LQDWLRQ

WDUJHWLQJSHJJHGH[FKDQJHUDWHUHJLPHDQGDFRPELQDWLRQRI&3,LQDWLRQDQGH[FKDQJH

rate targeting minimize the welfare losses.

)RUDQHFRQRP\ZLWKLPSRUWWR*'3UDWLRRIGRPHVWLFLQDWLRQWDUJHWLQJGHOLYHUV

WKHOHDVWZHOIDUHORVVIROORZHGE\&3,LQDWLRQWDUJHWLQJDQGWKHQ7D\ORUW\SHUXOH)RU

FRXQWULHVZLWKLPSRUWWR*'3UDWLRVRI&3,LQDWLRQWDUJHWLQJGHOLYHUVWKHOHDVW

ZHOIDUHORVV)RULPSRUWWR*'3RI&3,LQDWLRQWDUJHWLQJH[FKDQJHUDWHSHJDQG

&3,LQDWLRQFXPH[FKDQJHUDWHSHJKDYHHTXLYDOHQWZHOIDUHORVVHV+HQFHFRXQWULHV

ZLWKDODUJHLPSRUWFRPSRQHQWFRXOGFRQWUROLQDWLRQMXVWDVZHOOE\WDUJHWLQJH[FKDQJH

UDWHVVLQFHLPSRUWHGLQDWLRQPDNHVXSDODUJHSURSRUWLRQRIRYHUDOORU&3,LQDWLRQ

These results are consistent with the literature under complete exchange rate pass

WKURXJK,QDUHODWLYHO\FORVHGHFRQRP\GRPHVWLFLQDWLRQWDUJHWLQJVWDELOL]HVGRPHVWLF

prices and output. As the level of opennessproxied by the import-to-GDP ratiorises,

increasing the ratio of foreign goods in the consumption basket so that CPI targeting

stabilizes overall prices and output.

13

13

Chung, Jung, and Yang (2007) note that the lower levels of openness could be less relevant with incomplete

exchange rate pass through.

A Welfare Evaluation of East Asian Monetary Policy Regimes under Foreign Output Shock | 17

Table 3: Welfare Loss after a Negative Foreign Output Shock Under Diferent Monetary

Table 3: Policies and Various Values of Import over GDP

Imports

over GDP

Monetary Policy

Fixed/

Pegged

Exchange

Rate Regime

CPI

Infation

Targeting

Exchange

Rate and

Infation

Targeting

Taylor-

type

Rule

Domestic

Infation

Targeting

Nominal

Income

Targeting

Real

Income

Targeting

1.0 0.44 0.44 0.44 55.65 10.04 246.11 693.19

0.9 0.57 0.37 0.51 42.18 8.56 187.02 515.26

0.7 1.53 0.51 1.22 22.37 5.91 101.58 265.77

0.5 2.35 0.71 1.91 10.13 3.69 49.25 122.14

0.3 2.33 0.78 1.97 3.47 1.06 19.92 47.48

0.1 1.42 0.61 1.28 0.64 0.53 5.60 13.56

CPI = consumer price index, GDP = gross domestic product.

Note: We use import over GDP as a proxy for (1) in the model. The elasticity of oil-to-capital is set at 3.14 as in Table 2.

1 in which optimal monetary policy under fexible price equilibrium is domestic infation targeting as in Gali and

Monacelli (2005).

Source: Authors' estimates.

We also calibrate the model for a pair of economies based on their ratios of oil to capital

and of import to GDP and calculate the welfare losses under various monetary policy

UHJLPHV7KHSDLUVRIHFRQRPLHVDUH+RQJ.RQJ&KLQDDQG6LQJDSRUHWKH5HSXEOLFRI

.RUHDDQG7DLSHL&KLQD0DOD\VLDDQG7KDLODQGDQG,QGRQHVLDDQGWKH3KLOLSSLQHV7KH

estimates of welfare losses under various monetary policy regimes are shown in Table 4.

7KH\VKRZWKDWHLWKHU[HGSHJJHGH[FKDQJHUDWHUHJLPHVRU&3,LQDWLRQWDUJHWLQJ

GHOLYHUWKHOHDVWZHOIDUHORVVIRU+RQJ.RQJ&KLQDDQG6LQJDSRUH2QWKHRWKHUKDQG

&3,LQDWLRQWDUJHWLQJGHOLYHUVWKHOHDVWZHOIDUHORVVIRU,QGRQHVLDWKH5HSXEOLFRI.RUHD

0DOD\VLDWKH3KLOLSSLQHV7DLSHL&KLQDDQG7KDLODQG

Table 4: Welfare Loss after a Negative Foreign Output Shock under Diferent Monetary

Table 3: Policies Calibrated for Various East Asian Countries

Country

Monetary Policy

Fixed/

Peg

Exchange

Rate Regime

CPI

Infation

Targeting

Exchange

Rate and

Infation

Targeting

Taylor-

type

Rule

Domestic

Infation

Targeting

Nominal

Income

Targeting

Real

Income

Targeting

Hong Kong, China and Singapore 0.47 0.47 0.47 56.90 10.97 258.76 720.08

Korea, Rep. of and Taipei,China 2.44 0.77 2.02 5.98 1.87 29.93 79.34

Malaysia and Thailand 0.93 0.39 0.77 31.01 17.66 134.55 357.72

Indonesia and the Philippines 2.27 0.73 1.87 6.47 1.87 31.53 70.50

CPI = consumer price index, GDP = gross domestic product.

Note: Hong Kong, China and Singapore have an average import over GDP of 1, and elasticity of substitution of 2.1. The Republic

of Korea and Taipei,China have an average import over GDP of 0.4 and an elasticity of substitution of oil and capital of 2.3.

Malaysia and Thailand have an average import over GDP of 0.8 and an elasticity of substitution of oil and capital of 5.1.

Indonesia and the Philippines have an average import over GDP of 0.4 and an elasticity of substitution of oil and capital of

8.5.

1 in which optimal monetary policy under fexible price equilibrium is domestic infation targeting as in Gali

and Monacelli (2005).

Source: Authors' estimates.

18 | ADB Economics Working Paper Series No. 299

C. Summary of Simulation Results and Welfare

Consistent with the empirical evidence documented by Hoffman (2007), the comparison

EHWZHHQUHVSRQVHVRIDOWHUQDWLYHPRQHWDU\SROLF\UHJLPHVVXJJHVWVWKDWLERWK[HG

H[FKDQJHUDWHUHJLPHDQGLQDWLRQWDUJHWLQJWHQGWRVWDELOL]HUHDOH[FKDQJHUDWHDQG

LQDWLRQDWWKHH[SHQVHRIVXEVWDQWLDOLQVWDELOLW\LQWKHUHDOHFRQRP\LLWKHPLWLJDWHG

decline in real output under the Taylor-type rule is explained by the large depreciation

RIQRPLQDODQGUHDOH[FKDQJHUDWHVDQGLLLLQDWLRQUDWHLVORZHVWXQGHU&3,LQDWLRQ

targeting. In addition, the decline in output is smallest under nominal and real GDP

targeting due to the higher rate of nominal and real exchange rate depreciation. However,

ERWKRXWSXWWDUJHWLQJDOVROHGWRWKHZRUVWLQDWLRQRXWFRPH&RQVLVWHQWZLWK)ULHGPDQV

SUHGLFWLRQVORQJUXQGLIIHUHQFHVDFURVVUHJLPHVDUHQRWVLJQLFDQW

We also compare the welfare effects of the various monetary policy regimes as compared

ZLWKWKHRSWLPDOPRQHWDU\SROLF\XQGHUH[LEOHSULFHVXVLQJDTXDGUDWLFVRFLDOZHOIDUH

loss function. We show that with an average oil-to-capital ratio of 0.27 and import-to-GDP

UDWLRRI&3,LQDWLRQWDUJHWLQJOHDGVWRWKHOHDVWZHOIDUHORVVIROORZHGE\LQDWLRQ

DQGH[FKDQJHUDWHWDUJHWLQJSHJJHGRU[HGH[FKDQJHUDWHUHJLPHGRPHVWLFLQDWLRQ

targeting, Taylor-type rule, and nominal and real output targeting. The simulation results

VKRZWKDWDQHJDWLYHRXWSXWVKRFNFDXVHVWKHLQDWLRQUDWHDQGVXEVHTXHQWO\WKHQRPLQDO

LQWHUHVWUDWHWRGHFOLQHXQGHU&3,LQDWLRQWDUJHWLQJ,QFRQWUDVWLQDWLRQULVHVXQGHU

Taylor-type rule or nominal and real output targeting due to the large depreciation in the

QRPLQDODQGUHDOH[FKDQJHUDWHV7KHVHQGLQJVDUHFRQVLVWHQWZLWKGH&DUYDOKR)LOKR

(2010).

,IWKHLPSRUWWR*'3UDWLRLVWKHZHOIDUHORVVRIFRXQWULHVZLWK&3,LQDWLRQFXP

exchange rate targeting is comparable to countries with either pegged exchange rate or

&3,LQDWLRQWDUJHWLQJ+RZHYHULIWKHUDWLRLVEHWZHHQDQG&3,LQDWLRQFXP

H[FKDQJHUDWHWDUJHWLQJLVRQO\VHFRQGEHVWWR&3,LQDWLRQWDUJHWLQJ,IWKHUDWLRLVOHVV

WKDQLWLVZRUVHWKDQHLWKHU7D\ORUW\SHUXOHRU&3,LQDWLRQRUGRPHVWLFLQDWLRQ

targeting.

Since East Asian economies vary a lot with respect to the ratio of import-to-GDP, ranging

IURPIRU,QGRQHVLDWRPRUHWKDQIRU6LQJDSRUHDQG+RQJ.RQJ&KLQDZH

calculate the welfare loss of various monetary policy regimes for ratios between 10%

DQG:HQGWKDWZLWKLPSRUWWR*'3UDWLRRIZHOIDUHORVVXQGHUWKH[HGRU

SHJJHGUHJLPHLVDOPRVWHTXLYDOHQWWRWKHZHOIDUHORVVXQGHU&3,LQDWLRQWDUJHWLQJ7KLV

LVFRQVLVWHQWZLWKWKH&KRZDQG0F1HOLVQGLQJWKDW6LQJDSRUHVZHOIDUHORVVZLOO

QRWEHVLJQLFDQWO\OHVVLILWVZLWFKHVWRDPRUHH[LEOHH[FKDQJHUDWHV\VWHPDQGLQDWLRQ

WDUJHWLQJ(FRQRPLHVWKDWGHSHQGKHDYLO\RQLPSRUWVVXFKDV6LQJDSRUHDQG+RQJ.RQJ

&KLQDFDQPRGHUDWHLPSRUWHGLQDWLRQE\SHJJLQJWKHH[FKDQJHUDWH,QFRQWUDVWIRU

LPSRUWVWR*'3UDWLRRIWKHGRPHVWLFLQDWLRQWDUJHWLQJGHOLYHUVWKHOHDVWZHOIDUH

loss as it also stabilizes output. When import-to-GDP ratio is between 0.3 and 0.9, CPI

LQDWLRQWDUJHWLQJGHOLYHUVWKHRXWFRPHZLWKWKHOHDVWZHOIDUHORVV

A Welfare Evaluation of East Asian Monetary Policy Regimes under Foreign Output Shock | 19

V. Conclusions

7KHJOREDOQDQFLDODQGHFRQRPLFFULVLVRIXQGHUOLQHGWKHYXOQHUDELOLW\RI

VPDOORSHQHFRQRPLHVWRDGYHUVHH[WHUQDORXWSXWVKRFNV$OWKRXJK(DVW$VLDVQDQFLDO

V\VWHPVZHUHODUJHO\LPPXQHIURPWKHJOREDOQDQFLDOLQVWDELOLW\WKHLUUHDOHFRQRPLHV

were severely affected by the deep recession of the advanced economies. This reignites

the debate about the appropriate monetary policy regime for a small open economy

subject to external shocks. The primary objective of our paper is to evaluate and compare

the welfare impact of external output shocks acting through the trade channel in eight

East Asian countries with different monetary policy regimes. To do so, we use a simple

G\QDPLFVWRFKDVWLFJHQHUDOHTXLOLEULXPPRGHOZLWKVWLFN\SULFHVDQGLPSHUIHFWFRPSHWLWLRQ

LQWKHJRRGVPDUNHW7KHDOWHUQDWLYHPRQHWDU\SROLF\UHJLPHVFRQVLGHUHGDUH[HGRU

SHJJHGH[FKDQJHUDWHUHJLPH&3,DQGGRPHVWLFLQDWLRQWDUJHWLQJ&3,LQDWLRQFXP

exchange rate targeting, the Taylor-type rule, and nominal and real output targeting.

$OWKRXJKRXU'6*(PRGHOLVKLJKO\VLPSOLHGZHFDQXVHLWVVLPXODWLRQUHVXOWVWR

VFUXWLQL]H+RIIPDQVHPSLULFDOHYLGHQFHDQGLGHQWLI\VLJQLFDQWGLIIHUHQFHVLQUHVSRQVHV

to foreign output shocks across monetary policy regimes. Compared to a Taylor-type

UXOHDQGQRPLQDODQGUHDORXWSXWWDUJHWLQJ[HGRUSHJJHGH[FKDQJHUDWHUHJLPHVDQG

LQDWLRQWDUJHWLQJSUHYHQWQRPLQDOH[FKDQJHUDWHDQGLQDWLRQIURPDGMXVWLQJDQGWKXV

prevents the real exchange rate from depreciating. The negative impact of a fall in foreign

output is thus largely passed to the domestic economy. The mitigated decline in real

output under a Taylor-type rule and nominal and real targeting is explained by a larger

GHSUHFLDWLRQRIWKHQRPLQDODQGUHDOH[FKDQJHUDWHV:HDOVRYHULI\WKDWLQDWLRQUDWHLV

ORZHVWXQGHU&3,LQDWLRQWDUJHWLQJDQGQRPLQDOH[FKDQJHUDWHLVVWDEOHXQGHUSHJV2XU

VLPXODWLRQUHVXOWVDUHFRQVLVWHQWZLWKWKHGH&DUYDOKR)LOKRQGLQJVWKDWLQDWLRQ

WDUJHWLQJFRXQWULHVKDYHORZHULQWHUHVWUDWHVWKDQQRQLQDWLRQWDUJHWLQJFRXQWULHV

Our simulation results are also broadly consistent with the stylized facts of the East

$VLDQH[SHULHQFHGXULQJWKHHFRQRPLFFULVLV$V7DEOHVKRZV+RQJ.RQJ

&KLQD6LQJDSRUHDQG7DLSHL&KLQDZKLFKWDUJHWWKHH[FKDQJHUDWHH[SHULHQFHGWKH

smallest volatility in exchange rate but suffered the largest cumulative reduction in real

*'3JURZWK2QWKHRWKHUKDQGWKHRWKHU(DVW$VLDQFRXQWULHVZKLFKSUDFWLFHLQDWLRQ

targeting, experienced larger currency depreciation but suffered a smaller cumulative

UHGXFWLRQLQUHDO*'3JURZWK,QDGGLWLRQWZRRIWKHLQDWLRQWDUJHWLQJFRXQWULHV

,QGRQHVLDDQG7KDLODQGH[SHULHQFHG&3,GHDWLRQDVSUHGLFWHGE\WKHPRGHO

2XUZHOIDUHDQDO\VLVVKRZVWKDW+RQJ.RQJ&KLQDDQG6LQJDSRUHVSHJJHGH[FKDQJH

rate regimes give the least welfare losses in light of their high ratios of imports to GDP.

7KLVLVFRQVLVWHQWZLWKWKH&KRZDQG0F1HOLVQGLQJIRU6LQJDSRUH:HDOVRQG

LQDWLRQWDUJHWLQJWREHDSSURSULDWHIRU,QGRQHVLDWKH5HSXEOLFRI.RUHD0DOD\VLDWKH

Philippines, and Thailand since it offers the least welfare loss. This is consistent with the

VWXG\RI&KXQJ-XQJDQG<DQJIRUWKH5HSXEOLFRI.RUHD+RZHYHUZHQGWKDW

20 | ADB Economics Working Paper Series No. 299

0DOD\VLDDQG7DLSHL&KLQDFRXOGUHGXFHWKHLUZHOIDUHORVVHVE\PRYLQJIURP&3,LQDWLRQ

FXPH[FKDQJHUDWHWDUJHWLQJWRZDUGWDUJHWLQJRQO\LQDWLRQ

At a broader level, our analysis can provide some guidance about monetary policy

regimes for small open economies. For such economies, which depend heavily on

exports and trade for growth, the capacity of monetary policy to cushion the impact of

adverse external output shocks is one of the most important criteria for the appropriate

policy regime. The pronounced impact of the recession in the advanced economies on

WKHVPDOORSHQHFRQRPLHVGXULQJWKHJOREDOFULVLVRIXQGHUOLQHVWKLVSRLQW

2XUKLJKO\VLPSOLHG'6*(PRGHOVLPXODWLRQUHVXOWVVXJJHVWWKDW&3,LQDWLRQWDUJHWLQJ

delivers the least welfare loss for most East Asian small open economies except for those

ZLWKDQH[FHSWLRQDOO\KLJKGHJUHHRILPSRUW7KHUHIRUHDQLPSRUWDQWDGGLWLRQDOEHQHWRI