Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Villa-Lobos's Brazilian-Inspired Cello Concerto No. 2

Transféré par

red-sealDescription originale:

Titre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Villa-Lobos's Brazilian-Inspired Cello Concerto No. 2

Transféré par

red-sealDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

VILLA-LOBOSS CELLO CONCERTO No.

2 A PORTRAIT OF BRAZIL

by Felipe Jos Avellar de Aquino

Doctoral Essay

Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in Performance and Literature (Violoncello)

Advisor: Dr. Matthew Brown

Eastman School of Music University of Rochester, 2000

Rochester, New York

when can a father say that the Son will be this or that? Now then, I dont know what will come out of my pen and thus it will be impossible for me to make any promise about the Concerto for Violoncello and Orchestra. The only thing I can declare is that I shall write a work with sincerity; it remains to be seen, nevertheless, if this sincerity will please or not. 1

Villa-Loboss response to Aldo Parisots commission (Peppercorn 1994).

For Sandra, Lucas, and my parents.

ii

Acknowledgements

I would like to greatly thank my advisor, Dr. Matthew Brown, for his invaluable insight and his coherent guidance. In addition, I wish to express my gratitude to

Professor Alan Harris, for helping me not only to play this piece but also to achieve a higher level in my musical development. Likewise, I have to acknowledge all my music teachers, specially my very first one, my dearest mom. I want to express my appreciation to the Villa-Lobos Museum, in Rio de Janeiro, for providing all the manuscripts and assisting with the research. Finally, I have to acknowledge the Brazilian Government, through the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development - CNPq, for supporting my studies at the Eastman School of Music.

iii

Preface

This doctoral essay studies the Brazilian elements in Villa-Lobos's Cello Concerto No. 2. It shows how these components infuse the finished score and how they appeared in the compositional process. By understanding the composer's inspirational sources we might enlighten any performance of the concerto. Although Villa-Lobos does not directly quote any folk themes in the Cello Concerto No. 2, the music sounds definitively Brazilian: folk-like elements and dance rhythms permeate the score. The use of Brazilian sources can be viewed as a tribute to a countryman, Aldo Parisot, to whom the work was dedicated. Interestingly, some of these elements were taken from the music of the northeast of Brazil, a region whose folk expression was greatly admired and studied by Villa-Lobos. Being born in that same region, I soon found that the piece had specific allusions to Northeastern material such as the desafio and berimbau patterns; this immediately compelled me to research and write about this marvelous work. Not by coincidence, the northeast is the same region that Parisot is from, in this way Villa-Lobos probably intended to capture his native roots. In order to understand Villa-Lobos's use of vernacular elements in the Concerto, this study traces his background, musical style in general, and his particular affection to the cello. This latter aspect of the study might unveil what compelled him to write such a piece. Moreover, this essay summarizes the formation of the Brazilian culture,

highlighting some of the elements that are crucial for the understanding of the work.

iv

In terms of the finished score, I discuss Villa-Lobos's use of Brazilian folk materials, such as idiomatic themes, harmony, rhythm, texture, form, and instrumental color. Some of these elements are obvious at the surface of the music but others are hidden in the texture. I consider, in particular, the influence of the guitar in Villa-Lobos's writing as well as the use of rhythmic patterns derived from Brazilian folk instruments, such as the berimbau and pandeiro. Moreover, I discuss some of the implications of trying to absorb vernacular material into the rarified genre of the concerto. Concerning the genesis of the piece, I discuss Villa-Lobos's sketches and manuscripts, currently owned by the Villa-Lobos Museum in Rio de Janeiro. These materials, which are available in facsimile, shed important light on Villa-Lobos's creative approach, as well as on the composition process of the work. Finally, this doctoral essay does not intend to make an ethnomusicological study of the Brazilian culture, its ultimate purpose is to demonstrate how the understanding of the Brazilian sources might be helpful in shaping the interpretation of the piece.

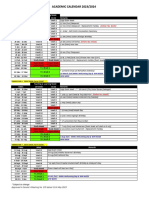

Table of Contents

Aknowledgements.............................................................................................................. iii Preface................................................................................................................................ iv List of Examples .............................................................................................................. viii List of Figures .................................................................................................................... xi List of Tables ..................................................................................................................... xi Chapter 1 - Introduction...................................................................................................... 1 1.1. Villa-Lobos and the Cello: a lifelong commitment ............................................ 2 Chapter 2 - Aspects of Villa-Lobos's Musical Style........................................................... 6 2.1. Search for a Musical Language ......................................................................... 6 2.2. Brazilian Folk Roots ......................................................................................... 11 Chapter 3 - Elements of the Formation of the Brazilian Culture and Folklore................. 18 Chapter 4 - Preliminary Considerations on the Second Cello Concerto........................... 23 4.1. Historical Background ...................................................................................... 23 4.2. Nationalism and Neo-Classicism in Villa-Lobos's Cello Concerto No.2 ......... 27 Chapter 5 - Nationalistic Elements in the Work ............................................................... 31 5.1. First Movement: Allegro non troppo ................................................................ 31 5.2. Second Movement: Molto andante cantabile ................................................... 50 5.3. Third Movement: Scherzo (Vivace). ................................................................. 60 5.4. Fourth Movement: Allegro energico ................................................................ 70

vi

Chapter 6 - Villa-Lobos's Manuscripts and the Compositional Process........................... 76 Chapter 7 - Conclusion ..................................................................................................... 84 Appendix - List of Villa-Lobos's Compositions for the Cello.......................................... 86 Bibliography ..................................................................................................................... 91

vii

List of Examples

Example 1. Villa-Lobos's arrangement of folk songs...................................................... 14 a) No Fundo do Meu Quintal, song No. 57 from the Guia Prtico.......................... 14 b) Ciranda, Cirandinha, song No. 35 from the Guia Prtico........................... 15 Example 2. Villa-Lobos's arrangement of Bach's Prelude 22, BWV 867, from the first book of The Well-Tempered Clavier......................................................................... 16 Example 3. Three scale modes from northeastern Brazil. ................................................ 21 a) First mode. ............................................................................................................ 21 b) Second mode......................................................................................................... 21 c) Third mode: characteristic scale containing a raised ^4 and lowered ^7.............. 21 Example 4. First page of the orchestration. ...................................................................... 30 Example 5. Main motive of the first movement. .............................................................. 33 Example 6. Responsorial style in the Cello Concerto emulating a desafio, mm. 9-25.... 35 Example 7. Papai Curumiass - Lullaby from Par......................................................... 38 Example 8. Allusion to J.S. Bach's polyphonic style....................................................... 40 a) J.S. Bachs G minor Fugue for lute (BWV 1000) ................................................ 40 b) Villa-Lobo's Cello Concerto No. 2 - 1st movement mm. 52 - 63. ........................ 40 Example 9. Ascending sequence based on the tritone, mm. 67-71.................................. 41 Example 10. Syncopated figure created by an implied accentuation, rehearsal No. 18. . 44 Example 11. Syncopated figure created by an implied accentuation as it appears in VillaLobos's Caboclinha and Nazareth's Tango .............................................................. 46

viii

Example 12. Polyrhythm in Brazilian folk music............................................................. 47 Example 13. Villa-Lobos's Concerto for guitar and small orchestra (1951). .................. 48 Example 14. Resemblance between the second movement of the Cello Concerto and the Aria from the Bachianas brasileiras No. 5... 53 a) Opening measures of the Aria from the Bachianas brasileiras No. 5.................. 53 b) Villa-Lobos's Cello Concerto No. 2, first theme of the 2nd mov., mm. 8-12........ 54 Example 15. Second movement mm. 35-42. ................................................................... 55 Example 16. J.S. Bach's Prelude No. 23 in B major, from the first book of The WellTempered Clavier, BWV 868. .................................................................................. 56 Example 17. F#-B interval that frames the movement. ................................................... 59 a) Opening of the second movement. ....................................................................... 59 b) Ending of the second movement. ......................................................................... 59 Example 18. Main motive of the Scherzo, whose bow stroke alludes to the percussive sounds of the berimbau............................................................................................. 61 Example 19. Lejaren Hiller's An Apotheosis of Archaeopteryx (1979) for piccolo and berimbau. .................................................................................................................. 63 a) The use of glissando in the berimbau. .................................................................. 63 b) Exploration of upper neighbor-tone as the main melodic feature of the berimbau............................................................................................. 64 Example 20. "Villa-Lobos glissando" in the Cadenza, related to the sounds of the berimbau... 66 Example 21. Dotted rhythmic figure as a new element in the Cadenza ........................... 69 a) Dotted rhythm figure in the Cadenza................................................................... 69

ix

b) Dotted rhythm as one of the main motivic elements of the Scherzo (third movement) of Villa-Lobos's Deuxime Sonate pour violoncelle et piano. .............. 69 Example 22. Main theme of the Finale ........................................................................... 72 Example 23. Motive of the second episode and its counterpoint treatment .................... 73 a) Motive of the second episode. ............................................................................. 73 b) Same motive explored in imitation, mm. 28-30. ................................................. 74 Example 24. Allusion to a berimbau pattern in the coda of the final movement. ........... 75 Example 25. Villa-Lobos's Sketches of the Second Cello Concerto ............................... 79 a) Beginning of the first movement (from the first page of the sketches) ............... 79 b) Motivic cell employed in the third movement (page 5 of the sketches).............. 80 Example 26. Pi mosso moderato section from the second movement .......................... 81 a) Piano reduction, mm. 37-44................................................................................. 81 b) Orchestration of the same passage, mm. 35-42 ................................................... 82

List of Figures

Figure 1 - Villa-Lobos's cello at the Museu Villa-Lobos, Rio de Janeiro - Brazil. ............ 5 Figure 2 - Program of the first performance of Villa-Lobos's Cello Concerto No. 2 ....... 26 Figure 3 - The berimbau ................................................................................................... 62

List of Tables

Table 1 - Formal scheme of the first movement. .............................................................. 49 Table 2 - Formal scheme of the second movement .......................................................... 58 Table 3 - Formal structure of the third movement............................................................ 67 Table 4 - Formal scheme of the fourth movement............................................................ 71

xi

CHAPTER ONE Introduction

Written in 1953, Villa-Lobos's Cello Concerto No. 2 belongs to his final compositional period. As such, it is the last of a string of important works for cello and orchestra, which also includes the Grand Concerto (1913) and the Fantasia for cello and orchestra (1945). Heitor Villa-Lobos is generally regarded as the most important Brazilian composer. Born in Rio de Janeiro in 1887, he enjoyed great popularity during his lifetime both in his homeland and abroad. It is perhaps a sign of his international reputation that the Fantasia for cello and orchestra was dedicated to Serge Koussevitzky. 1 There can be little doubt that his total musical output, which includes around one thousand works, was strongly influenced by the Brazilian folk and popular music. In fact, Villa-Lobos was the first Brazilian composer to insert a strong national identity into his works, as such he influenced several generations of composers in his country. Towards the end of his long and productive life he fulfilled several concerto commissions, thereby incorporating virtuosic elements into his nationalistic

compositional style. The Cello Concerto No. 2 is just such a piece: it probably contains

The Fantasia was premiered in Brazil in 1946 by cellist Iber Gomes Grosso. Its first performance in the United States was given by Aldo Parisot, on 8 July 1957, with the Stadium Symphony Orchestra under the composer's baton, at the Lewisohn Stadium in New York City.

more folk and dance elements than any other concerto ever written for the instrument. Thus, Villa-Lobos managed to give his music a strong improvisatory character while adhering to the traditional demands of the concerto.

1.1. Villa-Lobos and the Cello: a lifelong commitment

Villa-Lobos started his musical training at an early age. When he was about six years old, his father, who was an amateur cellist, started teaching him the instrument on an adapted viola. Through this intense training, by 1898 he already started developing his love for the works of J.S. Bach, as well as for the popular music of Rio de Janeiro; two elements that were to become very influential in his compositions. As Churchill points out, "his father trained him to love music and to analyze every sound that he heard. He would play a game in which he named the pitches of any sound around him, a streetcar, a bird, or the crash of a pot in the kitchen. It can be said that anything that Villa-Lobos heard was absorbed and internalized through his powerful instinct." 2 Besides the cello, Villa-Lobos also played the guitar, an instrument widely employed in the Brazilian folk and popular music, which enabled him to be in contact with the most important popular musicians of his time. After his father's death in 1899, Villa-Lobos was obliged to work in order to support himself. This is when he began to play the cello professionally in places such as

Mark Churchill, "Brazilian Cello Music: A Guide for Performing Musicians." (Doctoral Essay, University of Hartford, 1987) 39.

theaters and cafs. According to Churchill, the performances at those venues led him to compose a series of short pieces for cello and piano. 3 At the same time, Villa-Lobos started taking cello lessons from Benno Niederberger at the National Music Institute of Rio de Janeiro. Later on he studied both cello and harmony with the influential In fact, Nascimento, together

Portuguese teacher Frederico Nascimento (1852-1924). 4

with Alberto Nepomuceno, anticipated Villa-Lobos in collecting Brazilian folk tunes on a trip to the North and Northeast of the country in 1888. These are regions that VillaLobos visited in 1912, when he went on a tour playing the cello as a member of Lus Moreira's Operetta Company. An accomplished cellist, Villa-Lobos composed several works for the instrument. Besides the pieces already mentioned, he also wrote two sonatas for cello and piano (the first of which is lost). In addition, he composed a Fantasia Concertante for 32 cellos (dedicated to the Violoncello Society in New York - 1958), the Bachianas brasileiras No. 1 (dedicated to Pablo Casals - 1930), and the Bachianas brasileiras No. 5 (1938) for cello ensemble and soprano soloist. Even if Villa-Lobos did not invent the genre of cello ensemble, it was certainly established by him. Early in his career Villa-Lobos used to play concerts with his first wife, pianist Luclia Guimares, Robert Soriano, Souza Lima, among others. 5 According to the

catalog of the Villa-Lobos Museum, he still performed the cello as late as 1930, when he

Ibid, 42. Ibid, 36. Villa-Lobos: Sua Obra, 2nd ed. (Rio de Janeiro: MEC, Museu Villa-Lobos [1972] ), 178-180.

premiered his arrangement of O Trenzinho do Caipira in So Paulo, accompanied by pianist Souza Lima. 6 After quitting playing professionally he never stopped to write new works for the instrument, as shown in his long list of cello compositions (see appendix). Even in his Professional Card of 1937, a mandatory employment document in Brazil, his profession is listed as musician/cellist. Furthermore, Parisot recounts that during the compositional process of the Second Cello Concerto, in 1953, Villa-Lobos was always demonstrating on the cello how a certain phrase or effect should sound. 7 Finally, in January 1959, the year of his death, Villa-Lobos served on the jury of the second International Pablo Casals Competition in Mexico, together with eminent cellists such as Andr Navarra, Zara Nelsova, Mils Sdlo, Gaspar Cassad, Mstislav Rostropovich, Maurice Eisenberg, Adolfo Odnoposoff, and Pablo Casals himself. Russian cellist Mstislav Rostropovich recounts:

He [Villa-Lobos] once announced his intention to write a Triple Cello Concerto for Pierre Fournier, Andr Navarra and myself, which would reflect our different personalities in musical portraits. I very much regret that death prevented him from fulfilling his wish. However, the composer's three musical loves - the cello, Bach, and Brazilian folk music - are clearly manifested in the first of his Bachianas brasileiras. 8

Ibid, 178.

Lisa M. Peppercorn, The Villa-Lobos Letters, Musicians in Letters No. 1 (London: Toccata Press, 1994), 137.

8

Rostropovich, Liner Notes, in Rostropovich: The Russian Years 1950-1974. EMI CDs 72017-72029 (released 1997), 32.

Today his instrument and bow are hosted at the Museu Villa-Lobos in Rio de Janeiro. His cello is labeled Martin Diht Chur, 1779, while his bow was made by L. Lecherc (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Villa-Lobos's cello at the Museu Villa-Lobos, Rio de Janeiro - Brazil.

CHAPTER TWO Aspects of Villa-Lobos's Musical Style

2.1. Search for a Musical Language

Even though Villa-Lobos died only forty years ago, his life is full of controversies and obscure passages, which make the work of several scholars somewhat contradictory. The problems affect mere biographical data such as determining the year in which he was born or the total number of his musical output. Peppercorn, for instance, was probably one of the first scholars to determine the composer's year of birth as 1887, while in several other sources this data appears anywhere between 1881 to 1891. 9 Regarding his musical compositions the numbers are even more contradictory. According to the

Harvard Concise Dictionary of Music, Villa-Lobos's musical output consists of more than three thousand works, the Baker's Biographical Dictionary of Musicians (8th edition, 1992) numbers two thousand, while Appleby's Bio-Bibliography lists about six hundred compositions. Bhague, on the other hand, mentions one thousand works, a number that is ratified by the Villa-Lobos Museum in Rio de Janeiro. More significantly, some scholars question the extent of Villa-Lobos's scholarly studies of Brazilian musical traditions and the originality of the folk material employed in his own music.

See L. Peppercorn, The History of Villa-Lobos Birth Date published in The Monthly Musical Record, 78 (898), (July/August 1948), 153-55.

As a composer from a country outside of the main musical stream, Villa-Lobos was a figure surrounded by myths and exotic episodes. In many instances he is pictured either as a wanderer that participated in all sorts of street musical gatherings, or as an exotic composer who was among native Indians in the middle of the jungle, searching for inspiration. Both of these images are ones that Villa-Lobos himself contributed to create. This poem by Mark Frutkin entitled "Villa-Lobos Lugs his Cello Through the Amazon Jungle" is a good example of how he has been frequently portrayed:

Villa-Lobos lugs his cello through the Amazon jungle. Where he started out is unimportant. Where he is headed is untrackable. No path threads the jungle together, but when he rests and plays each leaf takes its perfect place, the brown and green river bends and bends and never breaks. Birds like shattered stained-glass windows drawn to the quivering sound, blink their green eyes and sharpen their yellow beaks hoping to compete with the cello's music in the cool of evening.

At night the musician lays his body down inside the cello and he feels hollow and trembly in his vine-draped dreams.

The veins of his wrists are like strings. He dreams an entire orchestra of night that by morning will be nothing but dew its music lingering in the triple fan of leaves in the breathing of umbrella trees. 10

Despite all the controversial matters that surround his life, Villa-Lobos was, according to Bhague, the symbolic liberator of the music of Brazil from the postromantic European values that dominated its musical circles. 11 In fact, his early compositions still show a strong European influence, notably by the music of Claude Debussy and by the composition treatise Cours de Composition Musicale, by Vincent d'Indy. This influence can be clearly noticed in works such as the Sonata-Fantasia No.1 (Desesperance) for violin and piano (1913), the piano Trio No. 2 (1915), the cello Sonata No. 2 (1916), as well as in his first two Symphonies. Works that sound very French in character. Even before his first trip to Paris in 1923, Villa-Lobos was in touch with important figures such as Milhaud, Rubinstein, and Diaghilev. Despite living outside of the main musical stream, he was aware of the rapid changes in the music aesthetics that was taking place in Europe in the first two decades of the 20th century. Thus, Villa-

Mark Frutkin, "Villa-Lobos Lugs his Cello through the Amazon Jungle," PRISM International Vol. 26, Issue 2 (January 1988), 41.

11

10

Gerard Behague, Heitor Villa-Lobos: The Search for Brazils Musical Soul (Austin: University of Texas Institute of Latin American Studies, 1994), 149.

Lobos's acquaintance with Darius Milhaud, who lived in Brazil from 1917-1919, allowed him to become more familiar with the music of Debussy and Les Six. Rubinstein, with whom Villa-Lobos developed a strong friendship, was one of the first internationally reputed musicians to perform his works in Europe. 12 Diaghilev, Nijinsky, and the Ballets Russes caught Villa-Lobos's attention during their performances in Rio de Janeiro in 1913 and 1917. In these performances he had a chance to hear Debussy's Prlude l'aprs-midi d'un faune, Stravinsky's Petrushka and Firebird, as well as Ravel's Daphnis et Clo. 13 According to Wright, Villa-Lobos even planned a stage production of his symphonic poem Amazonas with the Russian company, a project that unfortunately was never accomplished due to Diaghilev's death in 1929. 14 Furthermore, during his stay in France Villa-Lobos was surrounded by a circle of important celebrities. Among them are some of the most important artists of the time, including figures such as Fernand Lger, Paul Le Flem, Florent Schmitt, Edgard Varse, Leopold Stokowski, Serge Koussevitzky, Arthur Rubinstein, Sergey Prokofiev, and Andrs Segvia. Another major event, important not only for the establishment of Villa-Lobos's compositional style but also a milestone to the advent of modernism in Brazil, was the so-called Week of Modern Art held in So Paulo in 1922. This was basically a festival, in which Villa-Lobos was one of the forefront figures. It consisted of concerts, art

As a result of this friendship, Villa-Lobos composed the Rude Poema, which is a musical portrait of Rubinstein's personality and contains some Amerindians melodies. Peppercorn implies that in these performances Villa-Lobos was playing the cello in the theater's orchestra (Pepercorn 1989, 39).

14 13

12

Simon Wright, Villa-Lobos, Oxford Studies of Composers (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1992), 19.

exhibitions and lectures that were to change the entire aesthetics of the arts and literature in Brazil. According to Bhague, the Week of Modern Art main goal was to seek "a national artistic renovation based on the principle of adoption of avant-garde European techniques in the arts mixed with enthusiastic promotion of Brazilian folk topics." 15 Musicologist Mario de Andrade, one of the philosophical leaders of the event, is even more emphatic. He remarks that the Week of Modern Art led to "the right of artistic experimentation, the updating of Brazilian artistic intelligence, the formation of a national artistic expression, and the elimination of the slavish imitation of European models." 16 composer. This event was thus a turning point in Villa-Lobos's evolution as a

Gerard Bhague, Music in Latin America: An Introduction, Prentice-Hall History of Music Series, ed. H. Wiley Hitchcock (Englewood Cliffs:Prentice-Hall, 1979), 185. Mario de Andrade, O movimento modernista (Rio de Janeiro: Casa do Estudante, 1942), 2; quoted in Mark Churchill, "Brazilian Cello Music: A Guide for Performing Musicians" (Doctoral Essay, University of Hartford, 1987) 7.

16

15

10

2.2. Brazilian Folk Roots

After discovering the richness of the folk music of Brazil, Villa-Lobos became the first Brazilian composer to insert a strong national identity into his works. His

compositional language created a school of nationalistic composers in his homeland. About his compositional style Villa-Lobos said:

No escrevo dissonante para ser moderno. De maneira nenhuma. O que escrevo conseqncia csmica dos estudos que fiz, da sntese a que cheguei para espelhar uma natureza como a do Brasil. Quando procurei formar a minha cultura, guiado pelo meu prprio instinto e tirocnio, verifiquei que s poderia chegar a uma concluso de saber consciente, pesquisando, estudando obras que, primeira vista, nada tinham de musicais. Assim, o meu primeiro livro foi o mapa do Brasil, o Brasil que eu palmilhei, cidade por cidade, estado por estado, floresta por floresta, perscrutando a alma de uma terra. Depois, o carter dos homens dessa terra. Depois, as maravilhas naturais dessa terra. Prossegui, confrontando esses meus estudos com obras estrangeiras, e procurei um ponto de apoio para firmar o personalismo e a inalterabilidade das minhas idias.

[I dont write dissonant pieces to be modern. Absolutely not. The way I write is a cosmic consequence of the studies Ive done, of the synthesis Ive arrived to portrait a Brazilian nature. When I sought to develop my culture, guided by my own instincts and experience, I realized that I could only come to a conclusion of conscious knowledge researching and studying works which, on the surface, were not musical. Thus, my first book was a map of Brazil, the Brazil that I combed through, town by town, state by state, forest by forest, scrutinizing the soul of the land. Then, the character of the people

11

of this land. Then, the natural wonders of this land. I went on, comparing my studies with foreign compositions, and I sought something to support and strengthen my personal approach and the unchanging character of my ideas.] 17

Even though Villa-Lobos's field research was not as systematic as Bla Bartk's, one can draw a parallel between the compositional thoughts of these two composers. They are related on the way they employed the vernacular material.

Hence, when discussing Bartk's Suite for piano, Op.14, Morgan affirms that "it can be said to represent a sort of 'free imitation' of folk music, in which the folk quality has been modified to accommodate the formal and developmental ambitions of concert music. Bartk later wrote that it should be the aim of the composer 'to assimilate the idiom of folk music so completely that he is able to forget all about it,' so that it becomes his 'mother tongue.' " 18 Compared to Villa-Lobos's own words above, this last statement can be easily applied to describe the compositional approach of the Brazilian composer. Like Bartk, he was close to any form of vernacular expression from the people of his native country, whose elements he ingeniously combined with the avant-garde European musical aesthetics of his time.

Museu Villa-Lobos Home Page. Villa-Lobos: Life and Works (1996) Online. Internet. Available: alternex.com.br/~mvillalobos/

18

17

Robert P. Morgan, Twentieth-Century Music: A History of Musical Style in Modern Europe and America (New York: W.W. Norton, 1991), 108.

12

Villa-Loboss bohemian lifestyle led him to participate directly in several forms of folk and popular expressions. For instance, he performed with the chores (urban instrumental music ensemble), participated in the Brazilian carnival, and played the cello in venues such as theaters and cafs. Besides, from 1905-1913 Villa-Lobos undertook several journeys throughout the country, notably to the northern (Amazon region) and northeastern part of Brazil. Even though his research was not as

scientifically oriented as those of Bartk and Kodly, Villa-Lobos collected over one thousand folk melodies. Moreover, he absorbed the folk elements from the three primary ethnic groups that comprise the Brazilian population: Portuguese, African, and native Indians. As a result of his extensive traveling and his contact with such a diverse folk material, Villa-Lobos compiled the Guia Prtico in 1932. It consists of harmonization of 137 collected Brazilian folk rounds, popular tunes, lullabies, and other childrens songs. It is important to point out that according to Bhague, as with most Latin American countries, it is difficult to make a clear distinction between Brazilian popular music and folk song. 19 Thus, the Guia Prtico, scored for childrens chorus, was mainly arranged for educational purposes, but Villa-Lobos actually employed several of its tunes in his own compositions. This is precisely the case of the Cirandas (1926) and A Prole do Beb No. 1 for piano (1918). When Villa-Lobos did not quote a folk material, he still incorporated folk characteristics into his compositions.

19

Gerard Bhague, Brazil, in The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, ed. Stanley Sadie. Vol. 3, 6th ed. (London: Macmillan, 1980), 224.

13

Example 1a shows the interesting rhythmic and melodic content of a Brazilian folk song. Besides, it demonstrates how Villa-Lobos carefully harmonized this simple tune named No Fundo do Meu Quintal. Example 1b is entitled Ciranda,

Cirandinha, song No. 35 from the Guia Prtico, whose theme Villa-Lobos employed in his Polichinelo from Prole do Beb No. 1, for Piano.

Example 1. Villa-Lobos's arrangements of folk songs. a) No Fundo do Meu Quintal, song No. 57 from the Guia Prtico.

14

b) Ciranda, Cirandinha, song No. 35 from the Guia Prtico.

According to Corra de Azevedo, Villa-Lobos found a strong affinity between Bachs compositions and Brazilian folk music. 20 At some point, the composer even claimed to have found counterpoint typical of J.S. Bach in Brazilian folk music, which

20

Luiz Heitor Corra de Azevedo,Villa- Lobos, Heitor, in The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, ed. Stanley Sadie, Vol. 7, 6th ed. (London: Macmillan, 1980), 765.

15

was never demonstrated with musical examples. 21 Despite this claim, Villa-Lobos deeply studied J.S. Bach's contrapuntal techniques, having transcribed several of his Preludes and Fugues from The Well-Tempered Clavier for both cello orchestra, and cello and piano. As a result, he incorporated several contrapuntal techniques into his own compositional approach, which can be noticed in many sections of the Cello Concerto No. 2. Example 2. Villa-Lobos's arrangement of Bach's Prelude 22, BWV 867, from the first book of The Well-Tempered Clavier.

21

Eero Tarasti, "Heitor Villa-Lobos and the Problem of National Neoclassicism." Atti del XIV congresso della Societ internazionale di musicologia: trasmissione e recezione delle forme di cultura musicale, (Torino: EDT, 1990), 384.

16

The combination of Bach's contrapuntal style with the strong rhythmic figures and melodic styles of the folk music from northeastern Brazil is probably what makes VillaLobos's music sound so unique. He treated folk tunes, or folk-derived material, in a contrapuntal texture that resembles Bachs. This latter feature was highly in fashion in the so-called neo-classic style of the first half of the 20th century. Hence, Villa-Lobos's Bachianas brasileiras are the best examples of how to combine neo-classical trends with a strong national inspiration. They consist of a series of nine suites for different

instrumentation, written between 1930-45, in which most of them contains a prelude and a fugal movement. 22 Ultimately, the fusion of the two elements discussed above is

embodied even in the title of this series.

Bachianas brasileiras No. 1 for 8 cellos (1930); No. 2 for small orchestra (1930); No. 3 for piano and orchestra (1938); No. 4 for piano (1930-6) and orchestrated in 1941; No. 5 for voice and 8 cellos (1938); No. 6 for flute and bassoon (1938); No. 7 for orchestra (1942); No. 8 for orchestra (1944); No. 9 for strings or mixed choir (1945).

22

17

CHAPTER THREE Elements of the Formation of the Brazilian Culture and Folklore

In order to understand Vila-Lobos's use of vernacular elements in the Cello Concerto No. 2, we have to take into consideration the formation of the Brazilian culture, highlighting some of the elements that are crucial for the understanding of the work. Among these aspects one must include the contribution of each ethnical group that form the Brazilian population, the use of modal and pentatonic scales, the use of percussion instruments, as well as the importance of the instruments from the guitar family.

Brazilian folk music is basically formed by the miscegenation of the three distinct ethnic groups already mentioned: Portuguese, Amerindians and Afro-Brazilians. Considering that Portugal colonized and ruled Brazil from 1500 to 1822, the LusoHispanic influence is very strong. Further European immigrations, such as the German and Italians that moved to Brazil in the 19th century, added other European aspects in the formation of the Brazilian culture. 23 On that respect, Mario de Andrade comments:

Furthermore, due to the French invasions in the course of Brazilian history, their influence on the formation of the Brazilian culture is also relatively noticeable. As simple example, until recently the French language was taught in schools, while the wealthy families used to send their sons and daughters to pursue an education both in France and Switzerland.

23

18

Although Brazilian music has attained an original ethnical expression, its sources are of foreign derivation. It is Amerindian in a small percentage, African to a much greater degree, and Portuguese in an overwhelmingly large proportion. Besides, there is a Spanish influence, mainly in its

Hispano-American aspectThe European influence is revealed not only through parlor dances such as the Waltz, Polka, Mazurka, and the Schottische, but also in the structure of the ModinhaApart from these influences, already absorbed, we must consider recent contributions, particularly American jazz. 24

Luso-Hispanic instruments, particularly from the string family, permeated throughout the country. According to Bhague, one of the most important means of folk musical expression is through the viola, a type of guitar with five double courses made of wire or steel. There are various sizes, the standard one being somewhat smaller that the Spanish classical guitar. There are at least five types of viola: the viola paulista, cuiabana, angrense, goiana, and nordestina. 25 The viola tradition presents a considerable variety of tuning. Approximately 25 different tunings are found just in So Paulo, each tuning employed according to the way the instrument is being used - i.e. to accompany a certain song genre, dancing, or even to play solo and in duets. Still according to Bhague, the

Mario de Andrade, Ensaio sobre a msica brasileira, 3rd ed. (So Paulo: Livraria Martins, 1972); quoted in Nicolas Slonimsky, Music of Latin America. Da Capo Press Music Reprints Series, ed. Frederick Freedman (New York: Da Capo Press, 1972), 110.

25

24

Gerard Bhague, Brazil, in The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, ed. Stanley Sadie. Vol. 3, 6th ed. (London: Macmillan, 1980), 229.

19

Luso-Hispanic influence can also be found in the melodies built on the old European modes, gapped scales, and altered modes. 26 The African influence came from almost 400 years of slave trade. This influence, which came primarily from Angola and Congo, can be noticed in the use of scales such as pentatonic, major diatonic with flattened 7th, and major hexatonic without the seventh degree. 27 Characteristically, "African rhythmic traits, such as the hemiola rhythm, form the basis of many rhythmic intricacies of Brazilian folk music." 28 The Amerindian

influence, in a smaller proportion, is noticed mainly through the use of percussion instruments, such as rattles of the maraca type, in the Brazilian folk and popular music. Hence, the Brazilian culture is an amalgamation of distinct elements. For

instance, the slaves' religious rites merged with Roman Catholicism to form unique AfroBrazilian cults, notable for their exotic ceremonies, in which the most influential is the Candombl. Brazilian composer Jos Siqueira, who also did field research, identifies three melodic modes that appear in the folk music of northeast of Brazil (Example 3). Like the authentic and plagal modes in the church modal system, each of these scales has a derived version. 29 Furthermore, Siqueira found anhemitonic pentatonic scales [0,2,4,7,9] being widely employed in the music of African-Brazilian origin. 30

26

Ibid. , 224. Ibid. , 224. Ibid. , 224.

27

28

29

Jos Siqueira, O sistema modal na msica folclrica do Brasil, (Joo Pessoa: Secretaria de Educao e Cultura, 1981), 1-9. Jos Siqueira, Sistema Pentatnico Brasileiro, (Joo Pessoa: Secretaria de Educao e Cultura, 1981), 1.

30

20

The first two scale modes are basically the Mixolydian and Lydian modes, respectively. Whereas the third mode, according to Siqueira, is very unique, it contains a raised ^4 and a flattened ^7 (Example 3c). This scale is thus one of the most striking features of the music of northeastern Brazil.

Example 3. Three scale modes from northeastern Brazil.

a) First mode.

b) Second mode.

c) Third mode: characteristic scale containing a raised ^4 and lowered ^7.

#^4

b^7

21

As described above, Brazilian folk and popular music combine many remarkable features. Thus, after composers started incorporating those characteristics into their work, Nationalism became a strong trend throughout the entire 20th century in Brazil. Thereby, as the study of Villa-Lobos's Second Cello Concerto will demonstrate, art music was strongly influenced by vernacular elements.

22

CHAPTER FOUR Preliminary Considerations on the Second Cello Concerto

4.1. Historical Background

The Cello Concerto No. 2 was written in 1953, in a period in which Villa-Lobos fulfilled several work commissions such as the concertos for guitar, harp, cello, and harmonica. This piece is, for instance, contemporary with the Harp concerto written for Nicanor Zabaleta. It belongs to Villa-Loboss last compositional period, which began around 1945. In this phase his compositional style is noted by the exploration of

instrumental virtuosity. Nevertheless, the Cello Concerto is not limited to a simple display of technical virtuosity, for Villa-Lobos continuously explores elements of Brazilianism. Among Villa-Lobos's cello works, the Concerto No. 2 is, in my opinion, the most outstanding. It was dedicated to the Brazilian cellist Aldo Parisot - one of the leading cello pedagogues in the USA, on the faculty of both Yale University and the Juilliard School of Music - who commissioned the piece for his first performance with the New York Philharmonic in Carnegie Hall. During the late 40s and 50s Parisot was in the peak of his concert career and was considered one of the most important cellists of his

23

generation. He even collaborated with Villa-Lobos on several aspects of the score, especially passages of virtuosic display. In an interview to Claude Kenneson, Parisot states that after his first appearance with the New York Philharmonic, Columbia management suggested him to request a Brazilian composer to write a new cello concerto. This is how he decided to commission the work to Villa-Lobos, who replied on how difficult it is to write for the instrument. Parisot then comments on his collaboration with the composer:

I went to New York from New Haven every day for one week and there I practiced in his hotel room - scales, etudes, concertos - while he was writing. On one side he had the cello concerto, on the other side a symphony, and he was jumping from one to the other. And who was there during all those sessions? Andrs Segovia! When Villa-Lobos had something ready in the concerto, he'd let me try the passage. Then he would say, 'No, no, Aldo. Not that way, this way.' He loved to hear sliding on the cello, not shifting connections, but real slides. And he would demonstrate. In one week he had the whole thing blocked out. Tailor made 31

Despite his close participation during the compositional process and the fact that the composer was an accomplished cellist, Aldo Parisot continued to alter the cello part both

Claude Kenneson, Musical Prodigies: Perilous Journeys, Remarkable Lives (Portland: Amadeus Press, 1998), 223.

31

24

in the first performance and in his subsequent recording of the work. He claims that these alterations were done so that the work would sound more idiomatic to the instrument. According to him, Villa-Lobos approved these changes, even though they did not appear in the published score. Following the premier under Walter Hendl on 5 February 1955, Parisot was granted exclusive rights to perform the concerto for two years. 32 He made the first recording of the piece, in 1962, with the Vienna State Opera Orchestra under Gustav Meier. The first edition was eventually published in Paris by Editions Max Eschig in 1982. 33

32

Walter Hendl later became the director of the Eastman School of Music.

So far, Editions Max Eschig has never published the orchestral score of the concerto, which still is in manuscript form.

33

25

Figure 2. Program of the first performance of Villa-Lobos's Cello Concerto no. 2.

26

4.2. Nationalism and Neo-Classicism in Villa-Lobos's Cello Concerto No. 2

It is common knowledge that Villa-Lobos had a very fertile and creative mind to write new themes. However, being mostly a self-taught composer, his greatest weakness was on how to organize his ideas within a coherent formal structure. The lack of formal training, on the other hand, led him to be much more audacious in his compositional approach. As we are able to verify in his second Cello Concerto, the use of the

vernacular element, whether a simple thematic material or even the use of a Brazilian musical genre, is always the leading factor in his musical language. This path seems to be a natural choice for a prominently nationalistic composer writing for a countryman in the peak of his international concert career. Some of the components of this piece were taken from the folklore of the northeastern Brazil, a region whose folk expression was profoundly studied by Villa-Lobos, and where Parisot was born. Therefore, Villa-Lobos's major task was to combine nationalistic trends, which includes a strong improvisatory character, with virtuosic writing, in a traditional genre such as the concerto. In this piece Villa-Lobos demonstrates some of his most characteristic compositional techniques as he combines elements of neo-classicism and nationalism. As such, in several sections he employs compositional techniques similar to those from his Bachianas, combining idiomatic material with contrapuntal procedures in the style of J.S. Bach.

27

Furthermore, Villa-Lobos employs the standard pattern for a four-movement work in this concerto, which can be viewed as another example of his neoclassical characteristic. 34 This pattern usually consists of an elaborated opening movement in a fast tempo (generally in sonata form), contrasted by a slower and singing second movement. This is followed by a Scherzo in the third movement and a Finale, generally in a fast tempo, cast in either rondo or sonata-rondo form. Thereby, the Second Cello Concerto lasts about twenty minutes and is divided into four movements, according to the archetype described above: Allegro non troppo, Molto andante cantabile, Scherzo (vivace) cadenza, Allegro energico. The first movement consists of an elaborated multi-sectional structure (though not in sonata form) that is contrasted by a slow second movement in an ABA form. The third movement is a rhythmically rich Scherzo,

followed by a compact Finale in rondo-form. Since the last two movements are very short, each one lasting three to four minutes, they are linked by a cadenza in order to give balance to the overall structure. Thereby, the cadenza works as a structural transition from the Scherzo to the Finale. Despite the use of elements that weaken the tonality, such as a bold harmony that includes chords with added 9th, 11th or even a 13th, and the constant avoidance of strong cadences to establish the main keys, the work has its basic tonal center in A minor. In terms of orchestration, the writing is somewhat conservative, in the sense that VillaLobos employs a standard large orchestra without exploring the percussion instruments to depict the vernacular ambience. As shown in the opening page of the orchestral score,

As observed in his musical output, Villa-Lobos followed this four-movement pattern very consistently (see appendix).

34

28

the instrumentation includes piccolo, 2 flutes, 2 oboes, english horn, 2 clarinets, bass clarinet, 2 bassoons, double bassoon, 4 horns, 2 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, percussion (pandeiro de caixa - a small tambourine-like with attached bells - side drums, celesta, cymbals, tam-tam), harp, and strings (Example 4).

29

Example 4. First page of the orchestration.

30

CHAPTER FIVE Nationalistic Elements in the Work

5.1. First Movement: Allegro non troppo

The form of the first movement is somewhat unclear. Even though some scholars label as a modified sonata form, it is in fact a multi-sectional movement in which each section presents and develops its own thematic material. Besides the use of distinct musical ideas, each section is clearly defined by change of tempo, meter, and texture. In order to depict the vernacular character, Villa-Lobos employs elements that diverge from the tonal common-practice, such as the use of modal and pentatonic scales. The

movement, however, has many tonal features for most of the time the composer makes use of triadic harmony and tonal sequences. Nonetheless, the continuous avoidance of VI motion makes the movement sound tonally ambiguous. It opens, for instance, with an open fifth E-B and closes with an E minor-seventh chord. In contrast, as the movement develops, the key of A minor is continuously emphasized through the use of pedal points and eventual points of arrival. Surprisingly, in this movement Villa-Lobos does not use percussion instruments as means of orchestration coloring. It is not uncommon to hear the cello accompanied either by the strings or the wind section alone. In this sense, he was probably concerned with balance between soloist and accompaniment, as he found somewhat difficult to write for cello and orchestra. 31

Section A - Introduction

The movement opens with an eleven-measure orchestral prelude that anticipates the main thematic material. The first measure presents a chord formed by the perfect fifth E-B, in the entire orchestra, colored with the sound of the tam-tam. According to Parisot, this chord depicts the sound of the Brazilian jungle. 35 From mm. 2-4, this chord is broken into a long ascending motion that goes from the low E1 in the double-basses to the high b3 in the piccolo, flutes and violins. While the bassoons sustain a double pedal (E-B), the melodic cell E-B passes through almost all the instruments of the orchestra, as if he is exploring the palette of orchestral colors in its entire range. In fact, the perfect fifth is employed linearly as the opening interval of the first theme, which is first stated by the orchestra and then presented by the soloist in m. 12. As shown in Example 5, the main motive of this section is comprised by two sub-motives: two ascending leaps, of a perfect fifth and a minor third (A), followed by a descending motion (B).

35

Aldo Parisot, Liner Notes, in Villa-Lobos's Cello Concerto No. 2/Guarnieri's Choro for cello and orchestra, Westminster Recordings LP XWN- 18755 (recorded 1962).

32

Example 5. Main motive of the first movement.

After the long orchestral fermata on the tone A, m. 12, the theme is presented by the solo cello in a recitative-like manner. Its highly declamatory style and improvisatory character immediately establishes a dialog between soloist and orchestra; each statement of the cello theme is subsequently responded by the orchestra as in a responsorial singing. In my opinion, this is reminiscent of the popular song genre known in Brazil as desafio. The term desafio (which literally means "challenge") refers to an orally transmitted tradition in which two or more alternating singers compete to show their improvisational skills on a given subject matter. This challenge may continue until one of the singers can no longer respond or gives up to end the contest. 36 Even though the desafio, a long

36

Gerard Bhague, Brazil, in The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, ed. Stanley Sadie. Vol. 3, 6th ed. (London: Macmillan, 1980), 239.

33

tradition in Europe, is not exclusively Brazilian in origin, it is very strong in the Brazilian culture. 37 the country. Several aspects of the opening section of the concerto are related to the desafio. The very first entrance of the soloist, for instance, is marked Impetuoso (impetuous), which refers to the impulsive and spontaneous character of the cello statement that challenges the orchestra. This improvisatory character is highlighted by the way in which this theme is presented. It consists of a written-out accelerando through the rhythmic diminution of the main melodic motive, in which a variation of sub-motive B is treated as descending sequences in mm. 15-20 (Example 6). Due to its declamatory style, the soloist opening statement becomes so irregular that requires a continuous shift of meter (mm. 12-21). In a ten measure span the meter signature changes from 6/4 to 9/4, 6/4, 2/2, and 6/4. Metric irregularity is further This form of folk expression is notably found in the northeastern region of

explored in the second cello intervention, mm. 26-28, in a sequence that displaces a three-note melodic motive in groups of four eight-notes. Those elements emphasize the irregularity of the phrases as if they were being simply improvised.

37

According to Bhague this improvisatory singing is very common in southern Europe. (Ibid. , 239)

34

Example 6. Responsorial style in the Cello Concerto emulating a desafio, mm. 9-25.

35

Improvisation is the most important element in the Brazilian desafio. Since each singer is expected to improvise on a given subject matter, the melody is generally subordinated to the text. In analogy, the motives from Example 5 in this opening section seem to be the subject of improvisation, whereas the resulting melodic material is the consequence of their manipulation. According to Bhague, the desafio consists of a recitative-like melody presenting melodic sequences and isometric rhythms. 38 Moreover, while one singer is improvising, the other makes short interventions or provides the accompaniment. 39 In the case of the Cello Concerto, the soloist and the orchestra alternate the statements of the thematic material. Each intervention presents the theme either in sequence or emphasizing a different key. Furthermore, whenever the theme is being stated, the other medium

provides the accompaniment by sustaining a pedal point or making short interventions. 40 The register explored in the cello part is another link between vocal and instrumental writing. The register of the cello is by nature the closest to the human voice, but in this entire section, mm.1-45, the range of the cello is restricted to its first three octaves, C - c1, which is very close to the range of the male voice. Even though the performance of the desafio is not restricted to a single gender, it is generally performed by male singers.

38

Ibid. , 239.

39

Slonimsky (Music of Latin America, 114, 303) defines four different kinds of desafio: ligeira, in short phrases and fast tempo; martelo, in recitative style; carretilha, in vigorous rhythmic movement; and parcela, in moderato tempo.

See Bhague for an analogy of one of a desafio style (embolada) in the second movement of the Bachianas brasileiras No. 5 (Bhague 1994, 118-122).

40

36

As mentioned above, despite the strong relation to the vernacular material, in this work Villa-Lobos does not quote any folk theme. However, we can find strong affinities between the thematic material of first cello entrance in the concerto and some Brazilian folk tunes. Such is the case with Papai Curumiass, a lullaby collected by Houston-Pret in the state of Par, in the Amazon region (Example 7). 41 The first striking analogy concerns to the irregular rhythmic construction of the lullaby and the opening theme of the concerto, which requires a continuous change of meter. The resemblance of the first four measures of Example 7 and measures12-14 of the concerto is also remarkable. This Brazilian lullaby, for instance, starts with an up-beat and presents two consecutive ascending leaps - a perfect fourth and a minor third - followed by a stepwise descending line that leads to the tonic note. The first cello entrance of the concerto starts with a similar melodic and rhythmic figuration. It contains two consecutive ascending leaps - a perfect fifth and a minor third - followed by a stepwise descending line, except for the descending major third E-C, that leads to the E.

41

Elsie Houston-Pret, Chants Populaires du Brsil (Paris: Librairie Orientaliste Paul Geuthner, 1930), 34.

37

Example 7. Papai Curumiass - Lullaby from Par, in Chants Populaires du Brsil.

38

Section B

After the opening section, a short transition leads to a melodic and textural contrasting segment that starts in rehearsal number 4 (Allegro in cut time). In this new section the cello presents an arpeggiated second theme in the style of guitar writing - an instrument that was extremely important in Villa-Loboss life. In the first eight measures of the B section, the arpeggiated theme is accompanied by an ostinato rhythmic figuration that emphasizes the offbeat syncopation. One could easily imagine a guitar accompanied by some percussion instruments playing these eight measures, whose insistent accompaniment gives a flavor of popular music. The reference to the guitar style is not limited to these few bars, in the Meno that begins in m. 54, another guitar-like figuration starts to be extensively explored (Example 8b). As mentioned before, the guitar is certainly the most important instrument employed in the Brazilian folk and popular music. Hence, in this section Villa-Lobos probably intended to depict its predominance. In order to illustrate the use of the guitar style, let's compare a similar figuration found in Bachs G minor Fugue for lute (BWV 1000), shown in Example 8a.

39

Example 8. Allusion to J.S. Bach's polyphonic style.

a) J.S. Bachs G minor Fugue for lute (BWV 1000).

b) Villa-Lobo's Cello Concerto No. 2, 1st movement, mm. 52 - 63.

The examples above show a very similar figuration. Example 8a emphasizes two distinct voices, whereas Example 8b establishes a three-voice texture in the cello part.

40

The continuous string crossing in this sort of figuration, which is somewhat unidiomatic to the cello, clearly represents Villa-Lobos's fascination for the guitar. The second theme is presented and developed within this section (mm.46-109). It explores the elements already mentioned as well as the melodic augmented second interval. Villa-Lobos also employs some of the current avant-garde compositional

techniques such as the ascending sequence based on the tritone in the cello part, over a descending chromatic line in the orchestral accompaniment (Example 9). Notice that the lower notes of this sequence form an anhemitonic pentatonic scale [0,2,4,7,9], as marked in the example bellow. Furthermore, in this section the composer also leaves room for virtuoso display as in the technically challenging passage in mm. 77-85.

Example 9. Ascending sequence based on the tritone, mm. 67-71.

[0,

2,

4,

7,

9]

[0,

2,

4,

7,

9]

[0,

2,

4,

7,

9]

41

The orchestral ritornello in mm. 86-93 leads to a variant of the arpeggiated theme. At this point, the end of the B section, Villa-Lobos combines some of the elements explored so far. Hence, from mm. 94-109 he combines the arpeggiated theme (mm. 9497) with a variant of motive A from the introduction (mm. 99, 101-103). In addition, he reorganizes the descending sequence that originally appeared metrically irregular in mm. 26-28. It is rearranged as regular sextuplets in mm. 104-105. Notice that in mm. 98-100 Villa-Lobos employs an exotic scale marked by the two augmented-second intervals, D-Eb-F#-G-A-Bb-C#-D. Furthermore, mm. 105-106 is one of the few examples of a clear V-I motion, which leads to the area of D, a resting point that closes the section.

Section C

The next important section, Pi mosso (rehearsal number 9, mm.110-174), abruptly changes the character of the music. It is marked by an intense dance rhythm, which includes syncopations and rhythmic displacement. In this section Villa-Lobos employs his favorite combination: a simple melodic material that recalls folk theme and its contrapuntal elaboration. Section C is, in fact, the most contrapuntal of the entire movement.

42

The orchestra introduces the section presenting a new motive in the oboe, bassclarinet, violins, cellos, and basses, in doubling octaves. Thus, exploring the extremes of instrumentation register. The solo cello enters one measure later, a fifth higher than the initial statement, creating an imitative texture. At some points, such as in mm. 114-119, the fabric contains as many as four different layers. In those measures, the bassoon plays an ascending stepwise line while the cellos explore an ascending sequence based on the first motive of this section. At the same time the insistent motive of the english horn supports the descending sequence of the soloist. In several instances the soloist establishes an imitative dialog with individual sections of the orchestra, as in mm. 123-135. In contrast, from mm. 136-149 the texture becomes homophonic, with the orchestra simply providing a harmonic support to the cello, until the return of the main imitative material in measure 150. The harmony at the end of this section is clearly modal, establishing Bb Aeolian in mm. 165-166 and closing on G Phrygian. Before ending the section, mm. 166-173, the violins curiously move in crude parallel fourths. This orchestration resource is employed as another example of Villa-Lobos's regionalism. Section C (mm. 110-174) can be viewed as a closed unity, since a new thematic material is presented and explored within those measures. Furthermore, at rehearsal number 15 (Tempo Primo), the orchestra restates the first theme of the movement, clearly articulating the return of a modified A section.

43

Section A'

The first theme that was heard in recitative-like style returns with a different rhythmic figuration and a distinct character in the final section of the movement. It is developed with the interpolation of some virtuosic passages that explore several aspects of the instrument technique. This includes extended arpeggios and double stops. In the first four measures of rehearsal number 18 (Example 10 - mm. 206-209), the lower double stops in the cello line create another characteristic Brazilian dance rhythm. This is a syncopated figure created by an implied accentuation, in other words, a syncopation obtained through melodic means. Thus, the lower double stops create an irregular accentuation on the first, fourth, and seventh notes of the eight eighth-note figure. This implied rhythm is a variant of a rhythmic pattern from the urban popular music of Brazil (see Example 11).

Example 10. Syncopated figure created by an implied accentuation, rehearsal No. 18.

44

Bhague defines syncopation as one of the most frequent accompaniment figures of the Brazilian polka, the maxixe, and the choro (Example 11). 42 According to him, this is a typical Villa-Lobos's rhythmic pattern, which he employed in several other works such as the Caboclinha (from A Prole do Beb No. 1 for piano) and the Lenda do Caboclo. Bhague further states:

the syncopated pattern obtained exclusively through accentuation of the first, fourth, and seventh notes of the eight sixteenth-note pulsation finds its counterpart in numerous tangos of the popular composer Ernesto Nazareth, and recurs in other works of Villa-Lobos (e.g., in the ostinato figure of the first piece of the second Prole do Beb and the Noneto). The syncopated melody of Caboclinha further epitomizes the basic patterns of much popular dance music: the so-called habanera pattern (2/4 ), extended

to form what is a ubiquitous figure in Latin America and the Caribbean, called tresillo by the Cubans (2/4 followed by one of its numerous variants. 43 or ), and

42

Gerard Behague, Heitor Villa-Lobos: The Search for Brazils Musical Soul (Austin: University of Texas Institute of Latin American Studies, 1994), 60-63.

43

Ibid, 61-62.

45

Example 11. Syncopated figure created by an implied accentuation, as it appears in Villa-Lobos's Caboclinha and Nazareth's Tango (in Bhague 1994, 63).

Coda

The first movement closes with a coda in which Villa-Lobos juxtaposes several rhythmic patterns (polyrhythm), and treats the first theme in rhythmic diminution. In fact, polyrhythm is another important feature of the Brazilian folk music, as shown in this example for voice and percussion instruments collected by the Brazilian composer Luciano Gallet (Example 12). Besides the intricate syncopated rhythms, this example shows a characteristic irregular accentuation.

46

Example 12. Polyrhythm in Brazilian folk music. 44

The way the cello part is written in the last nine measures of the first movement refers once again to the guitar style. It consists of broken chords and repeated notes in the top line. A similar figuration can be found in an excerpt from Villa-Lobos's guitar concerto written a few years earlier (Example 13). Before closing the movement with a B minor seventh chord, Villa-Lobos explores the E-B interval that was originally presented in the very beginning of the piece. The

return of the same interval that opened the work frames the movement and, above all, gives a sense of unity and closure.

From Nicolas Slonimsky, Music of Latin America, Da Capo Press Music Reprints Series, ed. Frederick Freedman (New York: Da Capo Press, 1972), 118.

44

47

Example 13. Villa-Lobos's Concerto for guitar and small orchestra (1951).

48

As shown in this analysis, the first movement is comprised by four main sections and a coda. It creates an ABCA' scheme, in which the final section (A') and the coda explore the opening thematic material. Each section is clearly articulated with change of tempo marking, which, in some cases, is combined with a shift of meter. Moreover,

each section contains an individual character, presenting and exploring its themes as a closed unity. The following chart summarizes the form of the first movement.

Table 1. Formal scheme of the first movement.

Section Section A Introduction Section B Section C

Tempo Marking Allegro non troppo

Measures 1-45

Thematic Treatment Theme I treated as a desafio Responsorial-like style

Allegro Pi mosso

46-109 110-173

Theme II in guitar-like style New theme (folk-like/dance character) and contrapuntal writing No development of themes I and II

Section A

Tempo primo

174-230

First theme newly treated and developed

Coda

231-246

Theme I in rhythmic diminution Polyrhythm

49

5.2. Second Movement: Molto andante cantabile

If in the first movement Villa-Lobos combines distinct elements of the Brazilian folklore, in the second he restrains to a single aspect of Brazilianism, which is the use of a major Brazilian genre, the Modinha, as its compositional model. Moreover, this

movement is marked by a strong resemblance with another Villa-Lobos's work, the famous Aria from the Bachianas brasileiras No. 5, written in1938, which is a Modinha in essence.

The Modinha, as pointed by Bhague, was one of the most important salon genres in Brazil and Portugal in the 18th and 19th centuries. 45 Thus, most of the Portuguesespeaking poets had their poems set to music in the Modinha style. Through the influence of the Italian opera aria, on the other hand, the Modinha "began to lose its original simplicity, acquiring elaborate melodic lines with typically superficial ornamentation." 46 Despite its European likely origin, this genre can be labeled as the Brazilian Aria. The Modinha, which is generally cast in minor keys, features a sentimental character, almost always dealing with love subject. Its performance was initially

restricted to the aristocracy, becoming so popular in Brazil that converted into one of the

45

Gerard Bhague, Modinha, in The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, ed. Stanley Sadie. Vol. 3, 6th ed. (London: Macmillan, 1980), 454.

46

Ibid., 454.

50

favorite genres for both popular and classical musicians. Hence, what initially was a colloquial salon genre gradually turned into an urban popular song. Scholars have observed a number of different forms in which the Modinhas have been cast, never establishing a fixed formal plan to its structure. However, Mario de Andrade affirms that the Modinha's main harmonic feature consists of a continuos change of mode (major/minor), with a tendency to modulate to the subdominant area. 47 According to Kiefer, several Modinhas open with a characteristic gesture, which consists of an opening phrase starting with ascending leaps followed by descending melodic lines. This is one of the elements that give this music its mournful character. The presence of internal syncopation in its melodic lines and the predominance of feminine endings are some of the characteristics verified by Kiefer. 48 Furthermore, the Modinha contains long melodic lines and is generally sung with guitar accompaniment.

Clearly related to the Modinha, the second movement of Villa-Lobos's Second Cello Concerto opens with an orchestral introduction that is marked mostly by a chromatic triplet figure in the lower instruments. This figure imitates the melodic basses of the guitar accompaniment of a Modinha and is explored as a subsidiary motive throughout the movement. Similarly to the opening of the first movement, the Molto andante cantabile starts with a sequence of an ascending melodic interval F#-B. 49 This

47

Mario de Andrade, Modinhas Imperiais, 8th ed. (Belo Horizonte: Editora Itatiaia Limitada, 1980), 8-9.

48

Bruno Kiefer, A modinha e o lundu: duas razes da msica popular brasileira, Coleo Lus Cosme Vol.9. (Porto Alegre: Editora Movimento, 1977), 17. As opposed to the ascending E-B in the first movement (see page 32).

49

51

melodic cell passes through the strings instruments, from the lower register of the cellos to the high pitched first violins. In fact, the introduction does not foresee any of the

thematic material that governs the movement. It is tonally and melodically unstable except for the presence of the accompaniment motive already mentioned. Unexpectedly, right in the first entrance of the solo cello, in m. 9, the audience is moved to the ambience of the Bachianas brasileiras No. 5. At this point the cello starts a theme that has the same ascending major third followed by two descending major seconds as in the Aria from the Bachianas. As mentioned above, the opening phrase formed by ascending leaps followed by a descending melodic line is characteristic to the Modinha. However, the rhythmic figuration of the main melodic voice is also very similar to that from the famous Aria (Example 14).

52

Example 14. Resemblance between the second movement of the Cello Concerto and the Aria from the Bachianas brasileiras No. 5.

a) Opening measures of the Aria from the Bachianas brasileiras No. 5.

53

b) Villa-Lobos's Cello Concerto No. 2, first theme of the 2nd movement, mm. 8-12.

Besides the example above, the pizzicati accompaniment in the middle section of the movement reinforces the similarities between both pieces. Thus, from mm. 37-57 the melodic line of the solo cello flows over two complementary lines: the pizzicati in the strings and a walking bass line that is doubled by the double-basses and an alternating woodwind instrument (Example 15). The character of urban popular song is noticed in the pizzicati passages that resembles a guitar writing, as well as in some bass line clichs played in the guitar accompaniment of a Modinha, such as in mm. 6-7, 34-35. Measure 44 is an example of 54

the subtle relation between this movement and the Modinha. In that measure the flute and double-basses play a scalar bridge in pizzicato that leads to the return of the main melodic material of the middle section. Modinhas. This is a common clich found in many

Example 15. Second movement mm. 35-42.

55

The figuration of the lower strings in mm. 37-42 is another reference to J.S. Bach's contrapuntal style. Notice how this figure is similar to the opening of Bach's Prelude No. 23 in B major from the first book of The Well Tempered Clavier (Example 16). This emphasizes the relation between this movement and the contrapuntal

techniques characteristic employed in the Bachianas.

Example 16. J.S. Bach's Prelude no. 23 in B major, from the first book of The WellTempered Clavier, BWV 868.

The resemblance to the celebrated Aria from the Bachianas brasileiras No. 5 is so evident that Mr. Parisot comments:

I had hoped Villa-Lobos would write a slow second movement similar in expression to his famous Bachianas for eight cellos and voice. When he finished the concerto the resemblance was remarkable, even to the melody of

56

the soloist accompanied by the pizzicati of the strings imitating the sounds of the Brazilian violo or guitar. 50

As in the Bachianas this movement is marked by the use of constant change of meter. This is a result of its asymmetrical and eliding phrases that occur specially in the outer sections. It also denotes to the improvisatory style that characterizes the entire concerto. Furthermore, this movement is marked by the intense use of chromaticism in its melodic lines. Modeled after the Aria from the Bachianas No. 5, the movement is clearly shaped as an ABA'. Unlike its model, this structure is preceded by an eighth-measure

introduction. Despite the fact that the melodic material of the Pi mosso moderato is a derivation of the A section - the rhythmic and melodic figuration of the solo cello is in essence a variant of the first theme - the threefold structure is clearly defined. The harmonic plan of the slow movement follows a characteristic tonal tendency of the Modinha, which consists of a modulation to the subdominant area. Thus, the A section is mostly in B minor, while the B section is in E minor. The return to the slightly modified A section reestablishes the initial key of B minor that closes the movement. The following chart describes the scheme of the movement (Table II).

50

Aldo Parisot, Liner Notes, in Villa-Lobos's Cello Concerto No. 2/Guarnieri's Choro for cello and orchestra, Westminster Recordings LP XWN- 18755 (recorded 1962).

57

Table 2. Formal scheme of the second movement.

Section Introduction A B A'

Tempo Marking Molto andante cantabile Largo Pi mosso moderato Tempo primo

Measures 1-8 9-36 37-68 69-99

Tonal Area Chromatic/tonally unstable B minor E minor B minor

As occurred in the first movement of the concerto, the melodic intervals that are extensively explored in the opening measures reappear at the end in order to frame the movement and create unity. Thus, F#-B is the melodic interval that frames the slow movement. In comparison to the Allegro non troppo, this feature has been slightly modified. The direction of the ascending opening tones, which form a perfect fourth, appear inverted at the end in order to close the movement with a stronger descending motion (Example 17).

58

Example 17. F#-B interval that frames the movement.

a) Opening of the second movement.

b) Ending of the second movement.

59

5.3. Third Movement: Scherzo (Vivace).

The Influence of the Berimbau and Capoeira

Even though this is the shortest movement of the concerto, just sixty-seven measures long, it is in the Scherzo that dance elements are mostly explored. Thus, the expression mark that entitles the movement is associated with its character rather than its formal structure. The orchestration of the Scherzo is very rich, in which Villa-Lobos employs the full orchestra, including an active participation of the percussion instruments and the harp, to an extent that had not been explored in the preceding movements. The Scherzo is grounded on a rhythmically strong motive based on a triplet figure, which sounds at a first glance as influenced by Spanish music (Example 18). This figure, in my opinion, might be originaly from Spain but it is also a stylization of the rhythmic patterns of the berimbau - a musical bow with a single string of African origins that is widely popular in Brazil and certainly very well know by Villa-Lobos. 51 One can not assure if Villa-Lobos intentionally combined the Spanish rhythm with the berimbau patterns or if he created this ingenuous combination intuitively. The most important

51

Originated in Angola and Congo, according to Renato de Almeida, the berimbau was brought to Brazil still in the 16th century (Almeida 1942, 115).

60

aspect is that the blending of European and African elements in some way summarizes the formation of the Brazilian culture (see Chapter Three).

Example 18. Main motive of the Scherzo, whose bow stroke alludes to the percussive sounds of the berimbau.

The berimbau (or urucungo) is a percussion instrument consisting of a wooden stick in which a metal string is attached to each end in order to provide its arch shape. There is also a hollowed gourd attached at the lower end of the bow that works as a resonator (see Figure 2). The main sound is produced by striking the string with a small and thin bamboo stick. Besides, a metal coin serves as a movable bridge that provides the different pitches. In order to complete the instrument, the performer holds, together with the bamboo stick, a small basket shaker called caxixi that provides an accompanying sound.

61

Figure 3. The berimbau