Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Platinga and The Problem of Evil

Transféré par

arkelmakDescription originale:

Titre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Platinga and The Problem of Evil

Transféré par

arkelmakDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Plantinga and the Problem of Evil

Heimir Geirsson, Iowa State University Michael Losonsky, Colorado State University

The logical problem of evil centers on the apparent inconsistency of the following two propositions: (1) God is omnipotent, omniscient, and wholly good (2) There is evil in the world. As Mackie notes, the inconsistency of these propositions depends on what he called quasi-logical principles , such as good is opposed to evil, in such a way that a good thing always eliminates evil as far as it can, and there are no limits to what an omnipotent thing can do.1 This is the problem that Alvin Plantinga takes to task in his celebrated response to the problem of evil. Succinctly, Plantinga denies that (1) and (2) are inconsistent, and aims to show so by arguing that Mackies principle that there are no limits to what an omnipotent thing can do is false. In particular, Plantinga argues for the claim that (3) It is possible that God is omnipotent, and it was not within his power to create a world containing moral good and no moral evil.2 We aim to defend Mackies case and question Plantingas free will defense.

1. Plantingas Free Will Defense. According to Plantinga, to strongly actualize some state of affairs is to be the cause of that state. So if God were to strongly actualize that human beings choose to do something, then God would be causing them to do it, and Plantinga believes that this is incompatible with freedom. So

according to Plantinga, God cannot strongly actualize a totality T that includes free actions, although, as we will see, God can, on Plantingas view, strongly actualize a world that subsequently includes free actions. Accordingly, God cannot strongly actualize worlds where a person freely chooses to either do or not do act A. Doing so, Plantinga claims, would involve God actualizing worlds where the person both is and is not free. Although God cannot strongly actualize a totality that includes free beings, God can weakly actualize such a world. God weakly actualizes a world W with free beings performing free actions by strongly actualizing T, a subset of world W that includes beings that have the potential to act freely, and the free beings complete the creation of W with their free acts.3 So, if God strongly actualizes a totality T, then Gods actions are sufficient to cause the states of affairs and events in T. But if God weakly actualizes a totality W, then Gods actions are not sufficient to cause the states of affairs and events in W. Instead Gods actions plus the free actions of some other agent(s) would cause some of the states of affairs and events in W. With the distinction between strong and weak actualization in mind, we can refine (3). What Plantinga aims to show is: (3) It is possible that God is omnipotent and it was not within Gods power to strongly or weakly actualize a world with moral good but no moral evil. There are two important premises Plantinga uses to defend (3). One has already been mentioned above, namely that the concept of freedom is such that it is logically not possible for God to strongly actualize, that is cause, someone to act freely. The second premise is about transworld depravity. Plantinga introduces the notion of transworld depravity when discussing a world in which a person named Smedes offers a bribe to Curley, who is free with respect to this bribe. This world

is such that if it were actual and Curley is offered the bribe, Curley freely accepts the bribe. Plantinga then writes: God knows in advance what Curley would do if created and placed in these states of affairs. Now take any one of these states of affairs S. Perhaps what God knows is that if he creates Curley, causes him to be free with respect to A, and brings it about that S is actual, then Curley will go wrong with respect to A. But perhaps the same is true for any other state of affairs in which God might create Curley and give him significant freedom; that is, perhaps what God knows in advance is that no matter what circumstances he places Curley in, so long as he leaves him significantly free, he will take at least one wrong action.4 Plantinga continues and says that if the story is true, then Curley suffers from transworld depravity. However, all Plantinga needs for his argument is that it is possible that everyone suffers from transworld depravity. Consequently, it is possible that God is omnipotent and that it is not within Gods power to strongly or weakly actualize a world with moral good and no moral evil, that is (3). So if (3) shows that (1) and (2) are consistent, Plantinga has shown that the logical problem of evil has a solution.

2. The Problem Triumphant. Even if we grant Plantinga his argument for (3), it does not follow that it is not possible that God has the power to weakly actualize a world in which Curley does not take the bribe. Plantingas discussion is compatible with the following scenario. God surveys all the relevant possible worlds, including the ones in which Curley freely does not take the bribe and ones in which Curley freely does take the bribe. Although God cannot strongly actualize worlds in which Curley makes a free decision, we will argue that God knows in which possible worlds Curley will complete Gods

creation by taking the bribe and in which worlds Curley will complete the creation by not taking the bribe and that he can weakly actualize these worlds. To see this, we need to take a closer look at counterfactuals of freedom and Gods knowledge of them. A counterfactuals of freedom, or CF, is a counterfactual with the following form: If p were in c, then p would freely do a where p is a possible free agent, c is a possible situation, and a is a possible free action. Plantinga, as do we, assumes that God has knowledge of CFs. But if God has such knowledge we can argue that God could have done better without eliminating free will. For suppose that God knows what Curley will do, although God does not determine Curleys actions. If God knows the truth of CFs then he can consider all alternatives and after doing so strongly actualize the world segment that continues with Curley not accepting the bribe. For example, God knows that if he strongly actualizes segment T1 then Curley will accept the bribe, and he knows that if he strongly actualizes segment T2 then Curley will not accept the bribe. Clearly, God can choose to strongly actualize different world segments without undermining the freedom of the agents in the relevant worlds. For when God avoids having his subjects caught in situations and events that allow the wrong action, then he is not eliminating free will. He is at most affecting what options are open for the subjects while they still can choose one action over another. But if that is so, then God can choose whether to strongly actualize T1 or T2 without undermining Curleys freedom. For, as Plantinga acknowledges, it is compatible with indeterminism being true that we know the truth of at least some CFs, and with Gods wisdom being infinitely greater than ours he could certainly know the truth of all CFs. Once we acknowledge that God knows the truth of CFs and that he can actualize different world segments without undermining freedom there is nothing to prevent the possibility of God creating a world in which Curley exists and does not take the bribe. Further, if Curley made some

other immoral choice, then nothing prevents the possibility of God creating a world in which Curley does not make that choice, and in which he refrains from both that act and from taking the bribe. Since the same can be said of every other morally significant choice Curley is faced with, there is nothing to prevent the possibility of God creating a world in which Curley never takes a wrong decision; i.e., nothing prevents the possibility of there being a world where no one is transworld depraved. Other things being equal, that world would surely be a better world than the one that contains the corrupt Curley. And if we now apply the same possibility to other persons, then we see that there is nothing to prevent God from creating a world in which everyone chooses to do what is right. In other words, even if Curleys free actions are undetermined, the existence of the world in which Curley chooses evil is still subject to Gods control, and since God knows CFs he knows Curleys future undetermined actions. This argument can be generalized. Even if we grant that it is possible that God does not have the power to strongly actualize worlds with free human beings and no moral evil, it does not follow that it is not possible that God does have the power to weakly actualize worlds with free human beings and no moral evil. In fact, clearly it is possible that God has this power. God surveys all the possible worlds, including how they are completed by free beings, and has a choice between worlds that are completed by free beings in such a way that there is no moral evil and worlds that are completed by free being in such a way that there is moral evil. A perfect God, namely one that is omniscient, omnipotent and wholly good, will weakly actualize the world that is completed with no moral evil. Clearly, as Mackie writes, his failure to avail himself of this possibility is inconsistent with his being both omnipotent and wholly good.5 Gods perfection, that is, Gods omnipotence, omniscience and omnibenevolence, on the one hand, and the existence of evil on the other hand remain incompatible.

In sum, if (4) is true, that is, if it is possible that God is omnipotent, omniscient, and wholly good and it was within his power to create a world containing moral good and no moral evil, then God would have created a world with good and no evil. To deny that he would do so is to assume either that he does not know of that world, or that he has no preference to create that world over a world that contains evil. The logical problem of evil thus remains because there are possible worlds in which God exists with free beings, moral good and no moral evil. A perfect God would have weakly actualized one of those worlds instead of the one we occupy. As we have shown, pace Plantinga, God has the power to do this without denying freedom.

J. L. Mackie, Evil and Omnipotence, Mind 64 (1955), p. 201. Plantinga, A., The Nature of Necessity (Oxford: The Clarendon Press, 1974), p. 184 3 A maximal world segment, T, of world W, would include everything in W up to a time. For example, one maximal world segment of the actual world includes everything up to George W. Bush being sworn into office. 4 The Nature of Necessity, pp. 185-186. Regarding the concept of significant freedom: a person is significantly free, on a given occasion, if he is free with respect to an action that is morally significant for him. And an action is morally significant for a person at a given time if it would be wrong for him to perform the action at that time but right to refrain from the performing the action, or vice versa. See The Nature of Necessity, p. 166. 5 Mackie, , p. 209.

2 1

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- Encounters with Luther: New Directions for Critical StudiesD'EverandEncounters with Luther: New Directions for Critical StudiesPas encore d'évaluation

- Barth and Brunner Discuss Natural Theology - Brave Daily Christian BooksDocument8 pagesBarth and Brunner Discuss Natural Theology - Brave Daily Christian BooksNathan Holzsterl100% (1)

- Christian Spirituality and Ethical Life: Calvin's View on the Spirit in Ecumenical ContextD'EverandChristian Spirituality and Ethical Life: Calvin's View on the Spirit in Ecumenical ContextPas encore d'évaluation

- Jonathan Tran - Philosophy and TheologyDocument225 pagesJonathan Tran - Philosophy and Theologyfilopen2009100% (3)

- The Logic of Intersubjectivity: Brian McLaren’s Philosophy of Christian ReligionD'EverandThe Logic of Intersubjectivity: Brian McLaren’s Philosophy of Christian ReligionPas encore d'évaluation

- Barth Vs BrunnerDocument3 pagesBarth Vs BrunnerJohnPas encore d'évaluation

- The Unbeliever and Christians Albert CamusDocument3 pagesThe Unbeliever and Christians Albert CamusAkbar HassanPas encore d'évaluation

- Cumenical Rends: Koinonia and PhiloxeniaDocument5 pagesCumenical Rends: Koinonia and PhiloxeniaMassoviaPas encore d'évaluation

- Believing Thinking, Bounded Theology: The Theological Methodology of Emil BrunnerD'EverandBelieving Thinking, Bounded Theology: The Theological Methodology of Emil BrunnerPas encore d'évaluation

- Redeeming the Broken Body: Church and State after DisasterD'EverandRedeeming the Broken Body: Church and State after DisasterPas encore d'évaluation

- Dialogue Derailed: Joseph Ratzinger's War against Pluralist TheologyD'EverandDialogue Derailed: Joseph Ratzinger's War against Pluralist TheologyPas encore d'évaluation

- America on Trial, Expanded Edition: A Defense of the FoundingD'EverandAmerica on Trial, Expanded Edition: A Defense of the FoundingÉvaluation : 5 sur 5 étoiles5/5 (4)

- Breaking Bread, Breaking Beats: Churches and Hip-Hop—A Basic Guide to Key IssuesD'EverandBreaking Bread, Breaking Beats: Churches and Hip-Hop—A Basic Guide to Key IssuesPas encore d'évaluation

- Christ and Controversy: The Person of Christ in Nonconformist Thought and Ecclesial Experience, 1600–2000D'EverandChrist and Controversy: The Person of Christ in Nonconformist Thought and Ecclesial Experience, 1600–2000Pas encore d'évaluation

- Lord, Teach Us to Pray: A Study of Prayer in the BibleD'EverandLord, Teach Us to Pray: A Study of Prayer in the BiblePas encore d'évaluation

- Warfare and Waves: Calvinists and Charismatics in the Church of EnglandD'EverandWarfare and Waves: Calvinists and Charismatics in the Church of EnglandPas encore d'évaluation

- Love Hans Urs Von Balthasar TextDocument2 pagesLove Hans Urs Von Balthasar TextPedro Augusto Fernandes Palmeira100% (4)

- Missional Economics: Biblical Justice and Christian FormationD'EverandMissional Economics: Biblical Justice and Christian FormationPas encore d'évaluation

- Virtue as Consent to Being: A Pastoral-Theological Perspective on Jonathan Edwards's Construct of VirtueD'EverandVirtue as Consent to Being: A Pastoral-Theological Perspective on Jonathan Edwards's Construct of VirtuePas encore d'évaluation

- Christ Across the Disciplines: Past, Present, FutureD'EverandChrist Across the Disciplines: Past, Present, FuturePas encore d'évaluation

- The Forgotten Compass: Marcel Jousse and the Exploration of the Oral WorldD'EverandThe Forgotten Compass: Marcel Jousse and the Exploration of the Oral WorldPas encore d'évaluation

- The Cross: Its Meaning and Message in a Postmodern WorldD'EverandThe Cross: Its Meaning and Message in a Postmodern WorldPas encore d'évaluation

- Confession GuideDocument8 pagesConfession Guideapi-231988404Pas encore d'évaluation

- Quests for Freedom, Second Edition: Biblical, Historical, ContemporaryD'EverandQuests for Freedom, Second Edition: Biblical, Historical, ContemporaryPas encore d'évaluation

- Aspects of Reforming: Theology and Practice in Sixteenth Century EuropeD'EverandAspects of Reforming: Theology and Practice in Sixteenth Century EuropePas encore d'évaluation

- Claiming Resurrection in the Dying Church: Freedom Beyond SurvivalD'EverandClaiming Resurrection in the Dying Church: Freedom Beyond SurvivalPas encore d'évaluation

- The Trinity and the Spirit: Two Essays from Christian DogmaticsD'EverandThe Trinity and the Spirit: Two Essays from Christian DogmaticsPas encore d'évaluation

- Natural Law - OdonovanDocument13 pagesNatural Law - OdonovanJean FrancescoPas encore d'évaluation

- A Post-Christendom Faith: The Long Battle for the Human SoulD'EverandA Post-Christendom Faith: The Long Battle for the Human SoulPas encore d'évaluation

- Interreligious Learning and Teaching: A Christian Rationale for a Transformative PraxisD'EverandInterreligious Learning and Teaching: A Christian Rationale for a Transformative PraxisPas encore d'évaluation

- Taking Hold of the Real: Dietrich Bonhoeffer and the Profound Worldliness of ChristianityD'EverandTaking Hold of the Real: Dietrich Bonhoeffer and the Profound Worldliness of ChristianityPas encore d'évaluation

- Is Evangelical Universalism an OxymoronDocument48 pagesIs Evangelical Universalism an OxymoronStuart McEwingPas encore d'évaluation

- Pinnock Charismatic PDFDocument30 pagesPinnock Charismatic PDFframcisco javier ceronPas encore d'évaluation

- Sutan To 2015Document27 pagesSutan To 2015Robin GuiPas encore d'évaluation

- Christ and the Christian Life: Two Essays from Christian DogmaticsD'EverandChrist and the Christian Life: Two Essays from Christian DogmaticsPas encore d'évaluation

- Election, Barth, and the French Connection, 2nd Edition: How Pierre Maury Gave a “Decisive Impetus” to Karl Barth’s Doctrine of ElectionD'EverandElection, Barth, and the French Connection, 2nd Edition: How Pierre Maury Gave a “Decisive Impetus” to Karl Barth’s Doctrine of ElectionPas encore d'évaluation

- Christ in Crisis by Jim Wallis - Book Study GuideDocument25 pagesChrist in Crisis by Jim Wallis - Book Study GuideChristopher LaTondresse100% (2)

- Sun of Righteousness Arise: God's Future For Humanity And The EarthD'EverandSun of Righteousness Arise: God's Future For Humanity And The EarthÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (3)

- The Rise of Theological Liberalism and the Decline of American MethodismD'EverandThe Rise of Theological Liberalism and the Decline of American MethodismÉvaluation : 5 sur 5 étoiles5/5 (1)

- Vegangelical: How Caring for Animals Can Shape Your FaithD'EverandVegangelical: How Caring for Animals Can Shape Your FaithÉvaluation : 5 sur 5 étoiles5/5 (3)

- A Treatise On First Corinthians 15 28Document13 pagesA Treatise On First Corinthians 15 28123KalimeroPas encore d'évaluation

- Augustine: Earlier WritingsD'EverandAugustine: Earlier WritingsJ. H. S. BurleighÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (7)

- A Catholic Reading Guide to Conditional Immortality: The Third Alternative to Hell and UniversalismD'EverandA Catholic Reading Guide to Conditional Immortality: The Third Alternative to Hell and UniversalismPas encore d'évaluation

- Playful, Glad, and Free: Karl Barth and a Theology of Popular CultureD'EverandPlayful, Glad, and Free: Karl Barth and a Theology of Popular CulturePas encore d'évaluation

- The Living God: A Guide for Study and DevotionD'EverandThe Living God: A Guide for Study and DevotionÉvaluation : 3 sur 5 étoiles3/5 (2)

- Journal of The Evangelical Theological SocietyDocument14 pagesJournal of The Evangelical Theological SocietyNabeelPas encore d'évaluation

- Christ Is Time: The Gospel according to Karl Barth (and the Red Hot Chili Peppers)D'EverandChrist Is Time: The Gospel according to Karl Barth (and the Red Hot Chili Peppers)Pas encore d'évaluation

- Understanding Social SinDocument19 pagesUnderstanding Social SinJenn TorrentePas encore d'évaluation

- The Problem of PietismDocument4 pagesThe Problem of PietismSteve BornPas encore d'évaluation

- The Endless Crisis As An Instrument of Power AgambenDocument5 pagesThe Endless Crisis As An Instrument of Power AgambenarkelmakPas encore d'évaluation

- Nota Conceptual Bono Demog y Empl JuvDocument5 pagesNota Conceptual Bono Demog y Empl JuvarkelmakPas encore d'évaluation

- Who Is Responsible For PeopleDocument2 pagesWho Is Responsible For PeoplearkelmakPas encore d'évaluation

- Ebola - The LancetDocument3 pagesEbola - The LancetarkelmakPas encore d'évaluation

- InfluenzaDocument12 pagesInfluenzaarkelmakPas encore d'évaluation

- What Is Each CountryDocument6 pagesWhat Is Each CountryarkelmakPas encore d'évaluation

- Mplementing CAMBRA in The Private PracticeDocument5 pagesMplementing CAMBRA in The Private PracticearkelmakPas encore d'évaluation

- 1 - 1 - Part 1 Introduction and Course Outline (2113)Document9 pages1 - 1 - Part 1 Introduction and Course Outline (2113)Asmita Wankhede MeshramPas encore d'évaluation

- Cuerpos de Desastres NaturalesDocument4 pagesCuerpos de Desastres NaturalesarkelmakPas encore d'évaluation

- Class1 CimaDocument28 pagesClass1 CimaarkelmakPas encore d'évaluation

- Zimmerman - Van Inwagen's Consequence ArgumentDocument14 pagesZimmerman - Van Inwagen's Consequence ArgumentarkelmakPas encore d'évaluation

- Platinga On God, Freedom and EvilDocument22 pagesPlatinga On God, Freedom and EvilarkelmakPas encore d'évaluation

- Berlin Declaration enDocument3 pagesBerlin Declaration enJCMMPas encore d'évaluation

- Howard-Snyder - Propositional FaithDocument29 pagesHoward-Snyder - Propositional FaitharkelmakPas encore d'évaluation

- A Defense of Alvin Plantinga's Evolutionary Argument Against NaturalismDocument341 pagesA Defense of Alvin Plantinga's Evolutionary Argument Against NaturalismarkelmakPas encore d'évaluation

- Community-Acquired Pneumonia in Childrenguidelines For TreatmentDocument4 pagesCommunity-Acquired Pneumonia in Childrenguidelines For TreatmentarkelmakPas encore d'évaluation

- American Academy of Pediatrics and American Academy of Family PhysiciansDocument17 pagesAmerican Academy of Pediatrics and American Academy of Family PhysiciansatikahanifahPas encore d'évaluation

- El Procomun de La TierraDocument30 pagesEl Procomun de La TierraarkelmakPas encore d'évaluation

- Clinical Practice Guide Line SinusitisDocument11 pagesClinical Practice Guide Line SinusitisGeorge RickersonPas encore d'évaluation

- Capas CabezaDocument1 pageCapas CabezaarkelmakPas encore d'évaluation

- Otitis Media With Effusion AAPDocument18 pagesOtitis Media With Effusion AAPMaria DoukaPas encore d'évaluation

- Ansiedad Al Tratamiento OdontologicoDocument0 pageAnsiedad Al Tratamiento OdontologicoarkelmakPas encore d'évaluation

- Training Effectiveness ISO 9001Document50 pagesTraining Effectiveness ISO 9001jaiswalsk1Pas encore d'évaluation

- Should Animals Be Banned From Circuses.Document2 pagesShould Animals Be Banned From Circuses.Minh Nguyệt TrịnhPas encore d'évaluation

- CH 19Document56 pagesCH 19Ahmed El KhateebPas encore d'évaluation

- Speech Writing MarkedDocument3 pagesSpeech Writing MarkedAshley KyawPas encore d'évaluation

- BI - Cover Letter Template For EC Submission - Sent 09 Sept 2014Document1 pageBI - Cover Letter Template For EC Submission - Sent 09 Sept 2014scribdPas encore d'évaluation

- Structural Works - SharingDocument37 pagesStructural Works - SharingEsvimy Deliquena CauilanPas encore d'évaluation

- Heidegger - Nietzsches Word God Is DeadDocument31 pagesHeidegger - Nietzsches Word God Is DeadSoumyadeepPas encore d'évaluation

- Tes 1 KunciDocument5 pagesTes 1 Kuncieko riyadiPas encore d'évaluation

- Professional Ethics AssignmentDocument12 pagesProfessional Ethics AssignmentNOBINPas encore d'évaluation

- National Family Welfare ProgramDocument24 pagesNational Family Welfare Programminnu100% (1)

- The Awesome Life Force 1984Document8 pagesThe Awesome Life Force 1984Roman PetersonPas encore d'évaluation

- An Analysis of Students Pronounciation Errors Made by Ninth Grade of Junior High School 1 TengaranDocument22 pagesAn Analysis of Students Pronounciation Errors Made by Ninth Grade of Junior High School 1 TengaranOcta WibawaPas encore d'évaluation

- Passive Voice Exercises EnglishDocument1 pagePassive Voice Exercises EnglishPaulo AbrantesPas encore d'évaluation

- Megha Rakheja Project ReportDocument40 pagesMegha Rakheja Project ReportMehak SharmaPas encore d'évaluation

- Trang Bidv TDocument9 pagesTrang Bidv Tgam nguyenPas encore d'évaluation

- Examination of InvitationDocument3 pagesExamination of InvitationChoi Rinna62% (13)

- Comal ISD ReportDocument26 pagesComal ISD ReportMariah MedinaPas encore d'évaluation

- Midgard - Player's Guide To The Seven Cities PDFDocument32 pagesMidgard - Player's Guide To The Seven Cities PDFColin Khoo100% (8)

- MiQ Programmatic Media Intern RoleDocument4 pagesMiQ Programmatic Media Intern Role124 SHAIL SINGHPas encore d'évaluation

- International Standard Knowledge Olympiad - Exam Syllabus Eligibility: Class 1-10 Class - 1Document10 pagesInternational Standard Knowledge Olympiad - Exam Syllabus Eligibility: Class 1-10 Class - 1V A Prem KumarPas encore d'évaluation

- LLB 1st Year 2019-20Document37 pagesLLB 1st Year 2019-20Pratibha ChoudharyPas encore d'évaluation

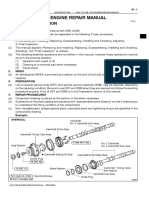

- How To Use This Engine Repair Manual: General InformationDocument3 pagesHow To Use This Engine Repair Manual: General InformationHenry SilvaPas encore d'évaluation

- Tax Q and A 1Document2 pagesTax Q and A 1Marivie UyPas encore d'évaluation

- Strategies To Promote ConcordanceDocument4 pagesStrategies To Promote ConcordanceDem BertoPas encore d'évaluation

- Architectural PlateDocument3 pagesArchitectural PlateRiza CorpuzPas encore d'évaluation

- Virtue Ethics: Aristotle and St. Thomas Aquinas: DiscussionDocument16 pagesVirtue Ethics: Aristotle and St. Thomas Aquinas: DiscussionCarlisle ParkerPas encore d'évaluation

- Maternity and Newborn MedicationsDocument38 pagesMaternity and Newborn MedicationsJaypee Fabros EdraPas encore d'évaluation

- 1120 Assessment 1A - Self-Assessment and Life GoalDocument3 pages1120 Assessment 1A - Self-Assessment and Life GoalLia LePas encore d'évaluation

- Bandwidth and File Size - Year 8Document2 pagesBandwidth and File Size - Year 8Orlan LumanogPas encore d'évaluation

- MVD1000 Series Catalogue PDFDocument20 pagesMVD1000 Series Catalogue PDFEvandro PavesiPas encore d'évaluation