Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Lem's Solaris: Certain and Uncertain Readings

Transféré par

Aviva Vogel Cohen GabrielCopyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Lem's Solaris: Certain and Uncertain Readings

Transféré par

Aviva Vogel Cohen GabrielDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Science Fiction Studies

#35 = Volume 12, Part 1 = March 1985

Istvan sicser!"#ona!, $r %he &oo' is the (lien) *n ertain and +ncertain #eadin,s o- .em/s Solaris

1. Contemporary science describes a world that is neither a rational cosmos, nor a roiling chaos, but something in between: a source of paradox, allowing for complementary, but contradictory, interpretations of humanity's relationship with non_human reality. The "classical" myth of the rational cosmos had shared with the prescientific myths underlying humanistic culture the conception that the human and natural realms were in some ways co-ordinated. Both wor ed according to intelligible, self-consistent, determining laws. !n the system of modern atomic physics, howe"er, scientists ha"e succeeded, according to #lanc , in purging science of determinism and "all anthropomorphic elements" $%rendt: &'(). But as *eisenberg obser"ed, in such a deanthropomorphi+ed uni"erse human beings always "confront themsel"es alone" (ibid., p. &,,). -ince e"ery answer they attain in their in"estigations into nature is a specific answer to a specific .uestion, the sum of these answers allows the application of otherwise .uite incompatible types of natural laws to one and the same physical e"ent. -cience's answers reflect the .uestions scientists are impelled to as of nature/ and thus anthropomorphism is reintroduced at the le"el of hypothesis formation that preselects the data to be studied. Beyond this, it remains extremely problematic whether the seemingly unbridgeable gulf between the languages of human culture and .uantum physics' purely probabilistic and mathematical expressions of the uni"erse will produce "an appropriate widening of the conceptual framewor " to resol"e all the present paradoxes and disharmonies in a new "logical frame," as 0iels Bohr hoped $see %rendt: &,,)1and as radical holistic physicists li e 2rit3of 4apra ha"e proposed1or whether the gulf is inherent in the new physics. The conclusions of the &5th century's science ha"e thus introduced an alienation from the cosmos more radical than any pre"iously concei"ed in human culture. 6hether this alienation is the beginning of a dialectical process of conceptual synthesis or an enormous stalemate, we cannot now. 6e cannot summarily re3ect either historical hypothesis. -2 characteristically transforms scientific and technological ideas into metaphors, by which those ideas are gi"en cultural rele"ance. !t wor s "ery much li e historical fiction in this respect. !t ta es a body of extratextual propositions belie"ed to be true, with no inherent ethical-cultural

significance, and endows it with meaning by incorporating it in fictional stories about characters representing typical "alues of the author's culture. %lthough the historical facts limit what can happen in historical fiction $in the realistic mode, at least), these facts are embedded among purely fictional facts to imply a metaphorical meaning beyond historiography's customary function of describing "what really happened." !n historical fiction, history is no longer true history, e"en if it is in fact true. !t is metaphorical, and hence "more than true"/ it is culturally significant. The same can be said, mutatis mutandis, about -2. 2urthermore, in wor s of artistic interest, we also expect the fictional action and the process of reading to correspond analogically to the fiction's metaphori+ed scientific ideas. 7eading the fiction should act as a metaphor for the process of cognition implied by the science. !n general, it is futile to loo for this sort of harmony of scientific ideas and aesthetic design in contemporary -2. -e"eral commentators ha"e noted that -2 writers usually adhere to the paradigms of romance $cf. 7ose: ,, 2rye: 8(). The paradigmatic forms of -2 are usually more archaic, indeed prescientific, than much of so called mainstream fiction. 9ne boo is an exception, howe"er: -tanislaw :em's Solaris, one of the philosophically most sophisticated wor s of -2. :em has often dismissed the suggestion that -2 should be 3udged by criteria different from the rest of literature.; <et most of Solaris' commentators ha"e discussed the no"el as a wor of "meta_-2," a "irtuoso example of generic criticism and the exploration of the possibilities inherent in the genre.& !n these pages, ! will consider Solaris somewhat differently, as an elaborate metaphor for the cultural and philosophical implications of scientific uncertainty for 6estern culture. 2. Solaris invites several parallel, and even contradictory, interpretations. !t can be read as a -wiftian satire, a tragic lo"e story, a =af aes.ue existentialist parable, a metafictional parody of hermeneutics, a 4er"antean ironic romance, and a =antian meditation on the nature of human consciousness. But none of these readings is completely satisfactory, and :em intended it to be so. The simultaneously incompatible and mutually reinforcing readings ma e the process of interpreting the text a metaphor for the scientific problem of articulating a manifestly paradoxical natural uni"erse. This inbuilt indeterminancy notwithstanding, most of Solaris' commentators agree on a common reading of the no"el's action and point. %ccording to this reading, Solaris is about the problem of whether human beings will e"er be able to ma e contact with a truly alien intelligence, and thus transcend the anthropomorphism and anthropocentrism apparently inherent in human cognition. !n the no"el, a century of attempts by the most ad"anced human

scientists to understand the mysterious, sentient ocean_planet, -olaris, has produced only a chain_reaction of paradoxes. The instruments that the early -olarists ta e to the planet to measure certain phenomena return to them physically transformed by -olaris/ the researchers thus cannot now what it is they ha"e measured (Solaris, 2:27). The methodological paradoxes produced by the exploration of -olaris, which are extrapolations of classical scientific method, come to occupy most of the -olarists' time. The inscrutable and opa.ue planet gradually becomes a macrocosmic mirror of the human image. The -olarists' obsession with the mysteries of -olaris dissol"es into the broader struggle to understand human reflection and identity. 6hen it appears impossible that human scientists will e"er brea out of the enclosure of human consciousness, their space exploration appears to be a religious .uest for "4ontact," mystical union with a godli e intelligence that might re"eal the purpose of the "mission of >an ind" in the uni"erse, and redeem it from cosmic alienation. By the time the narrator, the -olarist psychologist =ris =el"in, arri"es on -olaris -tation, ho"ering a mile abo"e the planet's surface, the theoretical paradoxes of -olaristics ha"e ta en on an unner"ing solidity. The -olarist protagonists are ""isited" by human simulacra, which appear to be incarnations of the scientists' repressed erotic and guilt fixations. 6e cannot now the purpose of these ?isitors, as the -olarists euphemistically call them, or how they arri"ed on the space station. They merely appear when their hosts awa en after a dream_filled sleep. They may be gifts from the planet, or instruments of exploration, or merely augmentations of the scientists' unconscious thoughts. The ?isitors disorient the scientists completely by displaying the .uintessence of each man's sub3ecti"ity in the form of an inscrutable ob3ect. @ach -olarist deals with his confusion in a different way. =el"in's friend and teacher, Aibarian, unable to contemplate "murdering" the .uasi_human beings, ills himself instead/ the pedantic physicist -artorius loc s himself in his laboratory, emerging only after he has in"ented a de"ice to annihilate the ?isitors/ the cyberneticist -nowB ta es to drin , irony, and self_pity1in fear and trembling. 9nly =el"in pro"es open and "innocent" enough to attempt to accommodate the presence of his ?isitor, a replica of his young wife 7heya, for whose suicide ten years earlier he has carried a deep sense of guilt. %t first, the ?isitors are indestructible, and appear to be material copies of an ideal template. 6hen they are e3ected into space, new "ersions of them reappear on the station later. They now only what their hosts remember, and for obscure reasons they must stay within sight of those hosts. !n time, howe"er, they become increasingly autonomous, and seem to de"elop human consciousness. !n the central lo"e story between =el"in and 7heya, 7heya appears to become e"en more human than the true human -olarists1 by willingly accepting her death in order to free her lo"er from his grotes.ue attachment to her.

The transformation in the no"el occurs with =el"in's disillusionment: his recognition that 7heya is not a human being, and that his inappropriate loyalty to her, which was moti"ated by earthly guilt and lo"e, has ept him from the wor to which he had de"oted his life: encountering the 9ther1the planet -olaris. =el"in is compelled to recogni+e that in a world defined by the encounter of the human with a non_human intelligence, the most noble human "alues may be only .uixotic illusions. *is awareness of his diminution comes in stages, with great suffering. 2irst, he must renounce his romantic faith. %t the end of the no"el, still mourning 7heya, he prepares to return to @arth "a sadder and wiser man"/ "! shall ne"er again gi"e myself completely to anything or anybody...and this =el"in will be no less worthy a man than the =el"in of the past, who was prepared for anything in the name of the ambitious pro3ect called 4ontact. 0or will any man ha"e the right to 3udge me" $;8:&5'). :i e all the positi"e assertions made by the protagonists of the no"el, this self_diminution .uic ly turns ambiguous. !n order not to return to @arth without ha"ing e"er physically touched_down on the planet, =el"in descends to the surface before he lea"es. There he plays the game of extending his hand to the ocean, which responds by en"eloping it, without actually touching it. %lthough no physical contact is made, =el"in is deeply affected, and feels "somehow changed. " ! had ne"er felt the gigantic presence so strongly, or its powerful changeless silence, or the secret forces that ga"e the wa"es their regular rise and fall. ! sat unseeing and san into a uni"erse of inertia, glided down an in"isible slope, and identified myself with the dumb, fluid colossus/ it was as if ! had forgi"en it e"erything, without the slightest effort or thought. $;8:&;5) =el"in does not lea"e after all. *e allows himself to belie"e in "a chance, perhaps an infinitesimal one, perhaps only imaginary" $;8:&;;), that some new manifestation of contact or shared creation will occur. 6e surmise his egoistic pro3ections are spent: "! hoped for nothing, and yet li"ed in expectation. ! did not now what achie"ements, what moc ery, e"en what tortures awaited me. ! new nothing and persisted in the faith that the time of cruel miracles was not past" $;8:&;;). >ost critics agree that in his concluding words =el"in has attained a new state of alertness and awareness. *is formerly aggressi"e dri"e for 4ontact has gi"en way to a more serene recepti"ity. -tephen C. #otts $p. D;) belie"es that at this point =el"in "has become...an empty slate ready to recei"e the

uni"erse on its own terms." 2or >ar 7ose, =el"in finally comes to the recognition that the 9ther does in fact exist separately from himself: "he nows that the ocean is real and he is willing to commit himself to whate"er the future may bring" $p. (D). 2or Ear o -u"in, "=el"in wins through to a painfully gained, pro"isional and relati"e faith in an Fimperfect god' " $p. &&5). @"en Ea"id =etterer, who argues persuasi"ely for the hermetic closure of Solaris, writes that "=el"in does learn something of man's limits: they are circumscribed by the reality of -olaris" $p. ;(,). The gist of Solaris in this reading is that human consciousness could not proceed to a new cognition as long as it was trapped in its own human_centered, egocentric conception of reason. 9nly a cathartic encounter with an alien reality insistent and intrusi"e enough to "iolate the membrane of self_sufficient human self_awareness could dissol"e the scientists' repressed emotional fixations and initiate a new recepti"ity to the uni"erse outside the self1a nowledge that something 9ther not only exists, but can transform the self. This reading $which ! ha"e admittedly fleshed out a bit) in"ol"es not so much a paradox as a hidden contradiction. !f we are to belie"e that =el"in is actually purged of illusions at the end of the tale, we must accept the reality of -olaris as a determinate 9ther, whose "not_humanness" defines =el"in for himself, and the reader. But how did =el"in come by this new ability to see himself ob3ecti"ely, if human cognition is a priori anthropomorphicG To see himself determinately1that is, "to learn something of man's limits," as =etterer writes1=el"in must ha"e been able to see himself as a "not_human," an ability that he could only ha"e learned from contact with -olaris. The critics who hold that =el"in arri"es at a new state of humbled and purified cognition conse.uently also appro"e the .uest for "*oly 4ontact," since only the ac.uisition of the 9ther's point of "iew could ha"e both dispelled =el"in's illusions and gi"en him nowledge of himself. !f this is true, then =el"in has redeemed the romantic impulses of -olaristics by pro"ing their truths. *is identification with the alien might be read as the necessary in"ersion that concludes the successful religious .uest, 3ust as the disco"ery of the Arail was to end in translation and absorption into Aod. Before coming to -olaris -tation, =el"in's contribution to -olaristics had been the disco"ery of possible correlations between encephalographic patterns indicati"e of certain human emotions with formally similar patterns ta en from -olaris $;; :;H&_HB). To put it another way, =el"in had disco"ered what could be construed as "personal" and emotional acti"ity in the planet. %t the conclusion of the no"el, the situation is re"ersed. *e substitutes for the personification of the alien his own self_identification with the alien1i.e., alienation from the human. The .uasi_religious .uest for 4ontact, rather than being an illusion to eep humanity from despair, apparently paid off after all: miracles ha"e occurred, e"en if they are cruel ones, and >an has placed one foot beyond his human limits, albeit into a mysterious and undefined

dimension. !t is an apocalypse, of sorts. Therefore, man's nowledge is not limited to himself and his creations. But is this reading "alidG !s =el"in really as empty at the end of the no"el as #otts claims, "ready to accept the uni"erse on its own terms"G Eoes not the uni"erse include =el"in, and the human species, among its termsG Eoesn't =el"in's identification with the alien lea"e us once again with no way of determining where the human ends and the 9ther beginsG 9nly #atric #arrinder has, to my nowledge, challenged the pre"ailing idea that =el"in ultimately succeeds in brea ing out of the anthropocentric hall of mirrors to the doorway of new cognition. 2or #arrinder, =el"in's decision to stay by the alien planet parallels Aulli"er's infatuation with the rational horses in his last 3ourney. The no"el's ending, #arrinder writes, shows the fate of a man who has abandoned humanity for the alien, and so is tragic but also absurd, a symbolic gesture holding at bay the recognition of despair. =el"in has followed through the logic of the scientist_explorer in the liberal_humanist tradition, until he is finally a "ictim of an isolating romantic obsession. $p. D8) To carry #arrinder's reading a step further: =el"in deserts humanity in order not to face the despair of nowing that his species is a singularity in the cosmos, and that reason, desire, lo"e, and truth1e"en the ideas of self and other1are merely tautologies in the isolated, self_reinforcing system of the "human. " !f, as =el"in tells us, he is completely committed to awaiting new interactions with -olaris, are we to admire his renewed spirit of sacrifice and dedication in the cause of 4ontact, or to suspect itG *ow are we to 3udge what we readG To choose either interpretation, =el"in as Arail =night or as Aulli"er, we must ha"e a standard against which to compare each interpretation1and that is precisely what we cannot ha"e in Solaris, 3ust as the -olarists ha"e no reality against which to compare humanity and the ocean_planet. -olaris's alienness is so threatening to the -olarists' scientific egoism that none of their conscious hypotheses regarding the planet can be ta en at face "alue. -till, there is e"idence in the no"el to support the idea that some mysterious and significant contact has been achie"ed between =el"in and the planet. There are moments in the action not interpreted by the protagonists $particularly ha"ing to do with 7heya, and with =el"in's dreams), and these bear hints of a special, non-rational relationship between

-olaris and =el"in that could easily go by the name of 4ontact. !n the first place, 7heya appears to be the co-operati"e creation of =el"in and -olaris: if she is a pro3ection, she is a pro3ection of both, since her form is produced by =el"in's unconscious memory and her substance is produced by the planet. 6e cannot now exactly what the ?isitors' purpose is, but 7heya belie"es she may be "an instrument" $8:D;) of some sort $perhaps analogous to the -olarists' instruments transformed by -olaris in the early stages of exploration). 9n the assumption that -olaris may ha"e "read off" the ?isitors from the dreams of the sleeping scientists after they had begun bombarding the planet with x_rays at night $':H&), the -olarists encode some of =el"in's wa ing thoughts and broadcast these by day, to "inform" -olaris of how much suffering the ?isitors are causing. The idea is farfetched, and it seems to be a way of distracting =el"in's attention from -artorius and -now's attempt to in"ent a neutrino_annihilator to be used against the ?isitors1a de"ice =el"in would li e to sabotage, to pre"ent 7heya's destruction. %s =el"in's encephalographic patterns are broadcast, howe"er, he becomes increasingly sensiti"e to direct intuitions of "an in"isible presence which has ta en possession of the -tation" $;&:;H'). >oreo"er, the annihilated ?isitors do not reappear after the emissions ha"e been completed, implying that the message must ha"e "gone through." >ost suggesti"e of all is =el"in's weird "dream" in 4hapter ;& $"The Ereams"). The language of the dream passage is worth close attention, but here ! can only note that the entire dream can be read as if it were being narrated by either =el"in or -olaris, which is for a while humanly "informed" by =el"in's thoughts. To ma e sense of this dream, for which =el"in pro"ides no commentary, we are in"ited to conclude that =el"in and -olaris penetrate each ocher to create a being1"a womanG" $;&:;H,), doubtless 7heya1and then to experience the excruciating suffering of a mysterious dissection. %t the dream's conclusion, the narrator obser"es hisIits suffering as "a mountain of grief "isible in the da++ling light of another world" $ibid.). 6hoe"er the obser"er here might be, this indeterminate process of incarnation implicates both =el"in and -olaris1as if each were percei"ing it through the other in some inarticulable way. !f these are moments of direct contact bypassing the mediations of egocentric rationality, then we can conclude that some exchange actually does occur between the human and the alien, the self and the 9ther. -now speculates that through the ?isitors -olaris may be learning about mortality, and the increasing human autonomy of the ?isitors may ser"e 3ust this purpose. $"!t implores us to help it die with e"ery one of its creations" J;&:;(&K, he tells =el"in.) -ince -olaris's power to stabili+e matter extends from massless neutrinos to its own orbit around two suns, it is possible that the planet experiences the pain of death for the first time through the annihilation of the ?isitors. $This speculation is 3ustified also by The "piercing scream which came from no human throat" J;&:;(5K, probably the death

agony of -artorius's ?isitor, that awa ens =el"in one night.) Through 7heya specifically, -olaris may ha"e learned dhe ethical and affecti"e essence of the human, the ability to transform necessary death into liberating selfsacrifice for the sa e of lo"ed ones. =el"in, in turn, appears to loosen his clutch on his narcissistic self pro3ections, and comes to identify himself with the planet and to "forgi"e" it, attaining an almost super_human patience. 3. These are suggestive passages, and they resist interpretation as anything other than moments of non_rational, non_conscious exchange1 true moments of contact so surpassing the common run of human communication that they could well be mista en for religious inspiration. -till, the fundamental indeterminacy of Solaris will not let us accept any interpretation based only on what =el"in, our sole informant, tells us. 9nce the .uestion is raised whether we can "see" something that is not a pro3ection of human consciousness, we cannot ma e a purely rational or ob3ecti"e determination one way or the other. 7eaders of Solaris are -olarists, too1the phenomena of the no"el's action reach us in the language of a -olarist and psychologist whose own reflections on how hypotheses are generated anticipate and subsume most of the hypotheses the reader might come up with independently. Cust as the indeterminacy of -olaris deflects its explorers bac into doubt about their methods of interpreting phenomena, the indeterminacy of the e"idence in Solaris deflects us bac into doubt about our own methods of reading. :em has constructed Solaris in such a way that e"ery apparently significant element in the text corresponds to other significant elements, creating a hall of mirrors with no windows from which to obser"e some pri"ileged noncorresponding structure of things. 7ose and =etterer ha"e demonstrated in their readings of the no"el that symbolic images reflect one another to a suffocating degree/ in Solaris, =etterer writes $e"o ing *eisenberg), "man confronts only analogues of his own image" $p. &5;). %llusions to the literature of illusion extend this doubling from the internal action of the tale to the status of the boo and reader in the world outside the text. 2or example, :em re.uires us to accept 7omanticism's fa"orite de"ices of doubling and self-reflection simply to follow the manifestly realistic plot. Ahosts, mirrors, dreams, unconscious memories and impulses, a web of symbolic correspondences, eerily enclosed spaces and sublime "oids all function as empirically concrete "ob3ects" in a scientific mystery. 0ames appear to be allusi"e, and perhaps e"en allegorical: =el"in, 7heya,8 -artorius, -naut, %ndre Berton, 2echner, the designations of the spaceships (Prometheus, Ulysses, Laocoon, Alaric), e"en -olaris itself. But since we cannot be sure exactly how these allusions wor or whether they all wor the same way, or e"en whether they are arbitrary red herrings 3ust imitating allusions,D the extratextual things to which they refer also lose their solidity, and are absorbed into the boo 's world of indeterminate elements.

6e now only that they correspond. 6e do not now what these correspondences mean. To create e"en broader ironies, :em in"o es a whole library of romance, satire, and myth: Eon Luixote, Aulli"er, #oe's phantom lo"ers, the Arail Luest, the tale of @ros and #syche, @cho and 0arcissus, the #assion and the 4reation. -ince the manifest problem of the -olarists and readers is how to determine whether human consciousness can now anything other than itself, each of the myths and stories in"o ed in the boo becomes a "ersion of the same problem1and thus each is transformed into a "ersion of Solaris. %gain, we are shown 6estern culture's problems and the creations responding to them reflecting one another. But what do these reflections signifyG The infinite play of mutually reflecting pro3ections, or the appropriation of transcendental nowledgeG The problem is raised "i"idly, ne"er to be dispelled, when =el"in comes upon the dead Aibarian's ?isitor, a gigantic %frican woman, who reclines soft and warm and ali"e next to Aibarian's corpse in the space station's free+er. Thrown into a panic, =el"in wonders whether what he is seeing is reality or a hallucination. *e tries to concoct a controlled experiment to test his sanity, but he nows that his conclusions can pro"e nothing. % deranged mind's illusions of certainty are indistinguishable from a sane mind's nowledge. 4onsciousness can ne"er ma e an ob3ect out of itself for ob3ecti"e obser"ation. =el"in lands on an apparent solution: he sets up a complicated problem of calculation, which he then matches with the precalculated conclusions of an independently orbiting satellite computer, on the assumption that he would not be able to match the computer's speed e"en in a hallucination. 6hen the numbers mesh, he belie"es he has demonstrated the reality of the ?isitors. !t is a persuasi"e tactic, but once the seed of doubt has ta en root it cannot be pulled up. 4ould not =el"in ha"e dreamed the satellite's results as wellG 6ho can determine the limits of the mind's power of pro3ectionG 0e"er in reading Solaris can we establish a hierarchy of phenomena or significations stable enough for us to interpret e"ents unambiguously. 6e can ne"er tell what is the "real" structure of e"ents and what are the de"iations. 0one of the protagonists' conscious assertions is abo"e suspicion. The -olarists are desperate men. They are faced not only with an alien reality resistant to their reason, but also, in the ?isitors, with their most familiar and unattracti"e sel"es out in the light of day. !n the final analysis, we ha"e no way of determining whether -olaris is not the collecti"e hallucination of the whole human species, li e the "monsters of the id" in the film orbidden Planet. 9r, in"ersely, whether the human species is not the hallucination of the dreaming "ocean yogi" -olaris, corresponding to the *indu notion of maya. 6e cannot tell what is the referent and what is the referring term. 9ur inability to determine =el"in's

fate one way or another is part of the necessary irony of the epistemological problem created by :em's alien. 0o definition of the 9ther $and, of course, of the self) is possible without reference to a standard that transcends both the self and the 9ther. But how can such a thing be concei"ed "scientifically"G !n Solaris's ma+e of correspondences, enclosures, and reflections, what we and the -olarists lac is something that would be non-corresponding, a "meta-alien" structure that would not mean anything: something as determinately different from the dialectical unity of self and 9ther as self and 9ther are from each other. But, of course, that is what neither science nor the reader can ha"e. 4. In the conclusion of his boo Fantastyka i futurologia (Science iction and uturolo!y)' :em discusses the techni.ues he belie"es are appropriate methods for expressing authentically the semantic problems of scientific technological culture in contemporary fiction. 2or :em, modern literature e"ol"es through the conflict between the ruling cultural codes of empiricism and the writer's need to ha"e a coherent set of normati"e rules of social conduct upon which, or against which, to base artistic norms. 6estern culture's dominant empiricism is in fact a set of anti-codes. "2or empiricism," :em writes, "the only in"iolable barrier is the totality of attributes of nature it calls the body of natural laws. Thus, obser"ing the human world from an empirical standpoint necessarily leads to the complete relati"i+ation of cultural norms e"erywhere where they impose Funfounded' imperati"es and restraints" $">etafantasia": '&). Traditionally, art wor ed with structures deri"ed from mythical-religious concepts that antedated scientific rationalism. These concepts reinforced certain social codes by presenting the culture and its axioms as sacred and un.uestionable. The realm of human decisions was "iewed as part of a cosmic order and was gi"en "alue because of its cosmic resonances. @mpiricism, according to :em, was 6estern culture's "Tro3an horse," because of its success in dissol"ing from within those cultural norms not based on utility and comfort. %rtists in the modern age ha"e been unable to find new axiogenic structures to replace the sacred mythological ones that secular science eroded. *ybridi+ation techni.ues abound but original, self consistent ethical and aesthetic structures can not de"elop where norms are constantly sub3ect to rational criticism and technological inno"ation. #arody of myth is one ob"ious and already traditional solution/ but it is purely critical, and entirely dependent on the myths it parodies. :em belie"es that two radical methods of "cunning structuration" $">etafantasia": '8) are particularly appropriate for &5th_century writers in the age of indeterminacy. The first is to gi"e "the total structure of a wor a multidimensional Findeterminacy,'" a techni.ue :em associates with =af a's "he #astle. The writer seals up different modes of signification in the wor 's structure in such a way that the reader is gi"en all the clues

necessary to accept that the wor signifies in a unified way, but not how to determine the significance of that unity, i.e., $hat the wor means. "=af a's "he #astle,% according to :em," can be read as a caricature of transcendence, a *ea"en maliciously dragged down to @arth and moc ed, or in precisely the opposite way, as the only image of transcendence a"ailable to a fallen humanity.... 6or s li e this do not expose those main 3unctures that could re"eal their unambiguous ontological meanings/ and the constant uncertainty this produces is the structural e.ui"alent of the existential secret." $">etafantasia": '8) The other approach :em singles out is the manifest interpenetration of incongruous structures and paradigmatic forms1some harmonious, some dissonant, and some changing their relations in the course of the fiction's de"elopment. :i e =af a's techni.ue, such writing denies the reader an absolute system of relations by which to interpret relati"e systems. -ome of the structures might be so di"ergent that they distort and "damage" the information produced by the other structures/ at other times, con"ergences might occur fortuitously. The most radical model of this techni.ue, in :em's "iew, is the 2rench nou&eau roman, and especially the wor of 7obbe-Arillet, where e"en chance enters as a constituti"e structure to create a clash between the paradigmatic forms of order and chaos $">etafantasia": 'D). Both of these techni.ues of "cunning structuration" are ade.uate to the philosophical problems raised by indeterminacy. 2or the writer who wea ens the reader's sense of certainty by wea ening the culturally pri"ileged con"entions of fiction also wea ens the reader's sense of certainty about the world to which the fiction's language is belie"ed to refer. Because of this systematic refusal to spea plainly, the reader begins to feel unsure whether he or she really understands what the description is concretely about, and this gi"es rise to the semantic wa"ering that characteri+es the reception of modern poetry .... These approaches ha"e a common origin: as the le"el of the reception's indeterminacy rises, the reader's own personal determinations begin to wa"er. !n practice, it is often impossible to determine whether a gi"en narrati"e structure is only "ery indirect and elliptical, but essentially homogeneous, or one deliberately damaged by 'chance noise,' or e"en perforated, softened and bent by

another, discordant structure. 2urthermore, since one can also create multilayered structures, e"en the concrete .uality of the described ob3ect or situation can be transformed beyond recognition and reshaped from one le"el of articulation to another. Thus it is often impossible to determine categorically whether the basic structure of description is an image of order or of chaos. $">etafantasia": ',). >any of the problems of interpreting Solaris e"aporate in the light of :em's meditations on modernism, for :em conflates these two ways of creating semantic indeterminacy in the design of his no"el. The similarity of Solaris to "he #astle is readily apparent: the planet is =el"in's 4astle. 6hether it will yield its secret or not, =el"in insists that it has a secret to yield, and that he has been "called" to plot its dimensions, li e the land_sur"eyor =. !nstead of opening the transcendental significance of the cosmos to him, -olaris remains opa.ue, "communicating" with him through inscrutable messengers, the ?isitors. 9nce these obstructi"e messengers are cleared away, =el"in belie"es he is, 3ust as #otts puts it, an empty slate ready to be inscribed upon by the demiurgic 9ther. The alien intelligence pro"ides human ind with a glimpse of its long-sought %rchimedean point in the uni"erse only to show how inaccessible it is. Solaris might be profitably read as a gloss on =af a's remar that >an "found the %rchimedean point, but he used it against himself/ it seems he was permitted to find it only under this condition" $%rendt: &,H). %t the same time, since the 9ther is $by definitionG) totally inscrutable, =el"in, li e =., accepts that his human cognition and his nowledge of his place in the uni"erse are corrupt in their essence. Both =el"in and =. follow the lead of Aulli"er, who would rather be a horse. :em punctuates and deforms this =af a-li e ambiguity with a "ersion of he other "system of indeterminacy" he associates with literary modernism, the mutual interference of narrati"e structures which outside the text appear as clear and distinct, e"en mutually contradictory. This method creates the in"erse effect to the impenetrable mystery of "dine structural e.ui"alent of the existential secret.'' The reader is made to feel that the elements of narrati"e are all familiar, "ta en from the repertoire of culturally nown situations" in"o ing "the repertoire of possible issues appropriate for JthemK " $">etafantasia": '')/ yet in their incongruous conflation, they seem "perforated, softened and bent" by one another $ibid., p. ',). The hard opacity of the unyielding secret is complemented by the nauseating fluidity of the familiar when facing that opacity.

!. This sense of distortion through "softening" of order comes about spontaneously in the action of Solaris. The "arious self consistent models that the protagonists1and readers1of the no"el use to interpret the mysterious action lose their distinctions. These putati"ely sharply defined systems for articulating reality are transformed into a single fluid process whose only articulation is its difference from the sentient planet. !n a world ruled by positi"e rationality $the implied epistemology of 6estern consciousness in Solaris), certain culturally pri"ileged structures of cognition through which writers ma e sense of the natural and social worlds $such as physics, biology, psychoanalysis, psychochemistry, romantic lo"e, religious faith, mythology, "fantomology,",to mention the most prominent ones in Solaris) appear to be all explaining and mutually exclusi"e from within those structures. 2rom the standpoint of contemporary culture as a whole, they appear to be parts that, when ideally combined, come closer to articulating the truth about reality than any single one of them. This "iew implies that human cognition operates by maintaining a great "ariety of possible techni.ues for world-describing $and the possibility of syntheses among these), some of which are certainly expected to assimilate whate"er reality has in store. %ll such pri"ileged models of explanation are based on the positi"e faith that truth exists "outside" consciousness and must be appropriated by it. 6hen confronted by a concrete existing thing that resists all strategies of appropriation, the common character of these strategies comes out in relief: all are pro3ections of human .ualities, as if they could exist outside human limits. 9f course, :em cannot create a truly alien creature to ma e us see this paradox from outside human consciousness. Though he ta es great pains to e"o e the sense of -olaris's strangeness through "i"idly detailed, and yet barely intelligible, descriptions of the planet and its excrescences, we always see the planet through a human obser"er's language as it stri"es to assimilate an a priori nonassimilable ob3ect. 9ur only e"idence that there is a truly alien intelligence is that all the intrahuman distinctions between modes of thought and types of discourse either disappear $as in =el"in's strange lo"e story) or, when they retain their distincti"eness, they become absurd anachronisms, personified by -artorius's pedantic de"otion to his positi"istic ideals and personal discipline. !n the face of that-which-does-not-correspond, the most di"erse and contradictory ways of ma ing sense become a single self-reflecting set of correspondences an amorphous mythoscience thrashing in its inability to articulate the alien. :em constructs this ironic "alienation" of cognition by at e"ery turn denying the -olarists and readers the opportunity to complete the structure of signification that they were in"ited to expect by the text's allusions. :em, and -olaris, e"o e certain structures particularly pri"ileged in 6estern culture, only to distort them through other structures alien, and e"en

inimical, to them. !n other words, hypotheses are made possible and pro3ected by modes of thought that contradict those hypotheses. !n this way, the failure of the positi"e science of -olaristics $which already encompasses all the existing branches of science and has produced a multitude of new branches by the time =el"in arri"es on the station) to appropriate -olaris gradually leads the scientists to act as if the "-olaris pro3ect" were the pro3ection of something more archaic $i.e., both older and more generati"e) than science. %t one moment it is religious longing and messianism. =el"in disco"ers this "iew fully elaborated in the writings of the -olarist >untius, who had written that "-olaristics is the space era's e.ui"alent of religion/ faith disguised as science.... @xploration is a liturgy using the language of methodology/ the drudgery of the -olarists is carried out only in the expectation of fulfillment, of an %nnunciation, for there are not and cannot be any bridges between -olaris and the @arth" $;;:;H5. -olaristics as messianism and as science may, howe"er, be only a pro3ection of erotic repression and narcissism, which founders when the -olarists ha"e to confront their 2reudian ghosts, the repressed "others" inside themsel"es. -now tells =el"in: 6e thin of oursel"es as =nights of the *oly 4ontact. This is another lie. 6e are only see ing >an. 6e ha"e no need for other worlds. 6e need mirrors....6e are searching for an ideal image of our world....%t the same time there is something inside us which we don't li e to face up to, from which we try to protect oursel"es, but which ne"ertheless remains, since we don't lea"e the @arth in primal innocence. $':H;) :i e the -olarist commentators, we can go further. %ll these ideological and psychological pro3ections may be the ine"itable pro3ection of the physical definition of the human body onto the uni"erse. -o the eccentric -olarist Arastrom speculates in discerning the anthropomorphisms "in the e.uations of the theory of relati"ity, the theorem of magnetic fields, and the "arious unified field theories" $;; :;,H). The ideal systems of reason come gradually to be seen as "ersions of human limitation disguised as transcendence. :em's -olarists, all men of science and hard common sense, are compelled to entertain an idea that necessarily casts gra"e doubts on the basis of their li"es as scientists: that there is no clear line between reason and unreason, reality and illusion. ". #ecause readers of $olaris approach it as fiction, and expect the science to be metaphorical, an educated reader cannot be as upset by the

idea of science as a systemati+ed form of despair as the -olarists are. The literary form offers a ind of comfort, deri"ing from the sense that the story's order is distinct from that of the ideas it "uses." %nd since these ideas are transformed by fiction into metaphors at the outset, the reader already starts out expecting some of the collapse of .uasi-rationalistic systems into one another that the professional scientists of the tale experience in the action. %s the possibility of a realistic interpretation of Solaris dissol"es for the reader, and the scientists themsel"es seem to turn to religious and psychoanalytic explanations, the reader loo s for clues of more traditional mythic structures. :em pro"ides such clues abundantly in "arious inds of allusions: in names, situations, and explicit speculations. But these mythic structures, too, are sub3ect to the no"el's underlying indeterminacy. They also suffer the same mutual deformation and incongruous moti"ation as the .uasi-rationalistic explanatory models. The whole -olarist enterprise seems trapped in a >yth of the 6ill1a myth designed to explain and support humanity's appropriation of the material uni"erse. This myth appears gross and absurd when confronted by a manifestly more powerful alien being. !nto this stalemate come the ?isitors, whom :em clearly identifies with >yths of :o"e. %lthough we ne"er learn who -now's and -artorius's ?isitors are, we can infer from Aibarian's %frican woman and from 7heya, as well as from some of -now's guarded comments, that all the ?isitors are incarnations of repressed ob3ects of erotic desire. The situation implies that the -olarists ha"e drawn their power to explore and their lo"e of ad"enture from this repression, and that the shoc of seeing their shadow-sel"es so concretely in front of them saps their egoistic resol"e. The ironic exception is -artorius. *is sadistic hatred of the ?isitors, and the unbending scientific egoism associated with it, is sufficient sustain him until he succeeds in in"enting the neutrino annihilator that " ills" the simulacra. 6hile =el"in, and to a lesser degree -now, come to accept the ?isitors' and -olaris's right to be real, -artorius's whole existence is predicated on the destruction of e"erything that interferes with his positi"e ego-science. 7heya in particular seems to carry the "alues of nonscientific mythicreligious mediation, albeit in a way that deforms distinct mythic structures of mediation by conflating them. 7heya gradually ta es on the role for =el"in of a personal mediator sent to him for inscrutable reasons by a deific intelligence. -he offers him the opportunity to redeem the guilt and shame of his life with the original 7heya, an absolution of the 9ld =el"in, a &ita nuo&a. But the exact "alue of 7heya's mythic-religious character in Solaris depends on how we interpret =el"in's decision to stay by the planet at the end of the no"el. 7heya begins as a mere embodiment of =el"in's erotic desire. -he seems li e an indestructible goddess attached to a mortal lo"er. *er physical structure appears to be so stable that she might ne"er grow old. *er anomalous

neutrino-based body, howe"er, ma es it doubtful that she could remain stable away from her hea"enly abode near -olaris. These associations are not lost on -now, who refers to 7heya once as a "fair %phrodite, child of 9cean" $;&:;(&), much to =el"in's annoyance1although he himself had earlier called Aibarian's ?isitor "a monstrous %phrodite" $B:B,). %s 7heya becomes increasingly human in her feelings and .uandaries, the character of her lo"e appears to change also. !t gradually becomes less arbitrary, clinging, and childli e, and increasingly faithful and altruistic. -he becomes a doubly in"erted, paradoxical image of 4hrist, a materialistic "ersion of the transcendental mediator. -he is a human form of -olaris, and a -olarian form of the human. %s she mysteriously e"ol"es into a conscious, free agent, again and again acting against her physical limits $by drin ing the li.uid oxygen, eeping her distance from =el"in, and lying about listening to Aibarian's cassette J(:;8BK), she fulfills1:em implies1essential cogniti"e, axiological, and ontological conditions of being human. -he is conscious of her ignorance of her origins/ she is willing to sacrifice her life for a lo"ed one/ and she is, in the end, able to die. The goddess freely chooses to accept death to liberate =el"in from his guilt. -ince -artorius and -now will not be swayed from their determination to annihilate the ?isitors, they ha"e the force of fate for 7heya. *er acceptance of death re_enacts the tragic grace of 4hrist's passion on -olaris -tation. *owe"er, 7heya can only recapitulate the myth of 4hrist if the whole mythic structure of 4hrist's mediation is complete in =el"in's life. *er death ma es sense as a .uasi_religious mediation only if =el"in at the end has been emancipated from his egoism and the burden of his past sins into a condition of new hope. 7heya's act would then imply a "ersion of transcendental grace, "alidating the religion of 4ontact and affirming the "personal" relationship between the godli e -olaris and the human =el"in. But if, with #arrinder, we "iew =el"in as a man stuc in the hall of mirrors of narcissistic self-reflection, then the character of 7heya's mediation changes from emancipatory to ironic. !nstead of 4hrist, she becomes @cho, the lo"eliest and most concrete of =el"in's fated self-reflections. %lthough she is the only one of his echoes capable of lo"ing 0arcissus, her lo"e can do nothing to sa"e him from drowning in the unfathomable ocean-pool whose surface reflects his face throughout the cosmos. These two mythic structures are inimical to each other. % myth cannot simultaneously "alidate transcendental grace and transcendental fatedness. %nd yet we cannot discard either structure in reading Solaris. The paradoxes of interpretation stem not only from the way these incompatible myths associated with 7heya are shaded into one another. The reader is also depri"ed of ways to determine the ontological status of the myths and mythic beings. The realistic ontology of the tale seems fixed. 6e are ne"er led to entertain magical or mythical explanations literally. The role of the mythic is ne"er emphasi+ed in Solaris. !ts presence seems only to

represent the natural tendency of people to create structures of explanation e"en when empirical and rationalistic conditions for one cannot be met. >yth then is an explanation of something that does not cease to be considered mysterious as a result of that explanation. 7heya's physical existence can be explained in materialistic terms: as a "form" ta en from a "psychic tumor" in =el"in's cerebrosides, as a neutrino based anthropomimetic structure, as an "instrument" of -olaris. !n a sense, then, her supernatural character is merely a particularly ob3ecti"e pro3ection of unconscious human $and -olarianG) needs. The mythology she e"o es is closer to 2reud's and 2euerbach's than to Aolgotha's and %ttica's. But, as usual in Solaris, the materialistic explanation leads only to its own limits and to the necessity of inferring a form inconcei"able in materialistic terms. The familiar form of the ?isitors, =el"in tells his colleagues, is only a camouflage: "the real structure, which determines the functions of the ?isitors, remains concealed" $,:;;;). -olarists can determine that the planet is composed of atoms. *ow it can produce a human being formed from neutrinos is beyond the comprehension of -olaristics. %. In Solaris, &em built into his design both of the literary "systems of indeterminacy" he discusses in his ">etafantasia"1hermetic ambiguity and mutual distortion of structures1to represent the cultural implications of the contemporary cogniti"e paradoxes. @ach "system" is an actual, culturally sanctioned ideological interpretation of those implications. *ermetic ambiguity implies that there are possible resolutions/ but, in =af a's words, they are "not for us. " 9pposed to this in"erted transcendentalist model, the mutual deformation of narrati"e structures attempts to reflect the "iew that human consciousness and nature are immanently "impure," indefinite processes. :em does not opt for one or the other of these radical solutions. *e is essentially a realist. *e adopts his clashing paradigms from the actual historical e"olution of 6estern culture, which has pro"en to be a more exact prototype for his drama of cogni+ance than more sub3ecti"e models might ha"e been. !t embodies, by definition, the strictest determinism $it has already happened) and the most complete openness $we can ne"er be sure $hat happened, because it is not o"er). Cust as -olaristics includes idealistic hypotheses that the planet is an "imperfect god" or "ocean yogi," materialistic hypotheses that it is a "plasmic mechanism," and syntheses, li e the "homeostatic ocean" theory, a true image of indeterminacy in reading includes both the .uasi-transcendentalist and .uasi-immanentist paradigms of uncertainty1each of which re_enacts prescientific ideologies in the language of science. Solaris cannot be made intelligible from only one of these mutually contradictory perspecti"es. Both -olaris and Solaris are the product of integrating certain clues into structures that cannot remain stable and closed: since myth and science, metaphor and realistic mimesis, moti"ate one another, no pri"ileged way of reading emerges. 6hether =el"in, the representati"e of human culture, is on the "erge of "widening JaK conceptual framewor " as Bohr hoped the science of the future would, or on

the "erge of an unbridgeable gulf between human culture and the uni"erse, we cannot now. :em lea"es his readers at the station where he belie"es the &5th century's .uantum--olarists arri"ed 3ust before them. 09T@;. :em's collected critical wor s a"ailable in @nglish are scheduled to be published in ;(HD by *arcourt Brace Co"ano"ich, under the title 'icro$orlds, edited by 2ran+ 7ottensteiner. &. @nglish-language commentaries on :em include 7ose $pp. H&_(D), -u"in $in Solaris, pp. &;&_&B), =etterer $pp. ;H&_&5&), and #otts. B. To a"oid confusion, ! will use the @nglish translators' "ersions, -now and 7heya, for :em's #olish originals, -naut and *arey. 8. !n the original #olish "ersion, :em names =el"in's wife and ?isitors "*arey. " The @nglish translators' decision to rename her "7heya" stri es me as an inspired impro"ement o"er the original. The lin ing of this ambiguous mediator with the @arth goddess reinforces and intensifies the irony of =el"in's decision not to return to the @arth. D. The reader who tries to piece Solaris together from apparent allusions is in for a hard time. Eoes the no"el's 2echner, the first explorer to die on -olaris and the possible source of the gigantic child witnessed by his colleague Berton, hint at the great Aerman psychophysicist, Austa" Theodor 2echner, who was e.ually well nown for his "hard" wor in psychological .uantification and his theosophical speculations on the angelic nature of planetsG !s %ndre Berton a distorted allusion to the manifester of -urrealismG -hould =el"in be associated with :ord =el"in and the only absolute currently a"ailable to scienceG !s there significance in the names of the spaceships mentioned by =el"in, and in their order of appearance: the glorious ascetic resol"e of the Prometheus followed by the Ulysses' connotations of cunning and homesic ness, which is then followed by the Laacoon's passi"e suffering for misreading the gods, and finally the Alaric's purely destructi"e power of con.uestG These and many other names seem to call out for interpretation, but we cannot be sure that they are not arbitrary. $!n correspondence, :em claims that all the names in the no"el came to him unconsciously, with the exception of -artorius, who is named for a tiny muscle.) '. The concluding chapter of the boo has appeared in @nglish as ">etafantasia: The #ossibilities of -cience 2iction" $see "6or s 4ited"). ,. !n his Summa "echnolo!iae, :em gi"es this name to the study of artificial realities "that are in no way distinguishable from normal reality by the

intelligent beings that li"e in them, but which nonetheless obey rules de"iating from that normal reality" (Summa, 8:;,;). 697=- 4!T@E %rendt, *annah. (et$een Past and uture $0<, ;('H). 2rye, 0orthrop. Anatomy o) #riticism $#rinceton, ;(,;). =etterer, Ea"id. *e$ +orlds )or ,ld $Bloomington, !0: ;(,8). :em, -tanislaw. ">etafantasia: The #ossibilities of -cience 2iction," S S, H $;(H;): D8-,5. -----. Solaris, trans. Coanna =ilmartin M -te"e 4ox $0<: Ber ley, ;(,5). -----. Summa "echnolo!iae $Budapest, ;(,'). #arrinder, #atric . "The Blac 6a"e: -cience and -ocial 4onsciousness in >odern -cience 2iction" -adical Science .ournal, no. 8 $;(,,), pp. B,-';. #otts, -tephen C. "Eialogues 4oncerning *uman Nnderstanding: @mpirical ?iews of Aod from :oc e to :em," in (rid!es to Science iction, ed. Aeorge -lusser $4arbondale, !:.: ;(,(). 7ose, >ar . Alien /ncounters. $4ambridge, >%: ;(H;). -u"in, Ear o. "The 9pen-@nded #arables of -tanislaw :em and Solaris% in :em's Solaris, ed. cit., pp. &;&-&B.

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- Exorcism PDFDocument249 pagesExorcism PDFEmmanuel Yeboah-ManteyPas encore d'évaluation

- GrimoiresDocument11 pagesGrimoiresRed Phoenix100% (4)

- Mythology of All Races VOL 10: North American (1916)Document496 pagesMythology of All Races VOL 10: North American (1916)Waterwind100% (5)

- Bok Christian - Pataphyscs - The Poetics of An Imaginary ScienceDocument258 pagesBok Christian - Pataphyscs - The Poetics of An Imaginary SciencegrundumPas encore d'évaluation

- D&D 5e AasimarDocument2 pagesD&D 5e Aasimarfishguts4ever86% (7)

- Black MagicDocument12 pagesBlack MagicShashank Shekhar100% (2)

- Occlith PDFDocument258 pagesOcclith PDFMaurizio Demichelis Scapin100% (1)

- The Testament of AbrahamDocument12 pagesThe Testament of AbrahamGeorge FahmyPas encore d'évaluation

- Ibn Arabi - Spiritual PracticeDocument173 pagesIbn Arabi - Spiritual PracticeAbidin Zein100% (9)

- Albert Coe The Shocking Truth PDFDocument128 pagesAlbert Coe The Shocking Truth PDFSachin SvkPas encore d'évaluation

- Genesis Six Giants Steven QuayaleDocument30 pagesGenesis Six Giants Steven QuayaleDavid Nowakowski100% (1)

- Let There Be Light On Genisis by Alvin Boyd Kuhn PHDDocument36 pagesLet There Be Light On Genisis by Alvin Boyd Kuhn PHDanuenkienlil1100% (1)

- Unweaving the Rainbow: Science, Delusion and the Appetite for WonderD'EverandUnweaving the Rainbow: Science, Delusion and the Appetite for WonderÉvaluation : 5 sur 5 étoiles5/5 (2)

- Adi Shakti Sant Mat 2012 FinalDocument42 pagesAdi Shakti Sant Mat 2012 FinalCadena CesarPas encore d'évaluation

- Fairman, The Myth of Horus I, JEA 21, 1935Document11 pagesFairman, The Myth of Horus I, JEA 21, 1935OusermontouPas encore d'évaluation

- OCCLITHDocument258 pagesOCCLITHXam Xann100% (9)

- Tara, A Manifestation of The Divine Feminine, by Lama Palden Drolma (2002) PDFDocument3 pagesTara, A Manifestation of The Divine Feminine, by Lama Palden Drolma (2002) PDFAviva Vogel Cohen Gabriel50% (2)

- Aliens - The Anthropology of Science FictionDocument176 pagesAliens - The Anthropology of Science FictionOZar15100% (2)

- Paul Klee Some Poems by Paul Klee 1962Document34 pagesPaul Klee Some Poems by Paul Klee 1962Priya Naik100% (2)

- Black Illumination - Zen and The Poetry of Death - The Japan TimesDocument5 pagesBlack Illumination - Zen and The Poetry of Death - The Japan TimesStephen LeachPas encore d'évaluation

- HANNAH HÖCH, TIL BRUGMAN, LESBIANISM, AND WEIMAR SEXUAL SUBCULTURE, by Julie Nero. 2013Document496 pagesHANNAH HÖCH, TIL BRUGMAN, LESBIANISM, AND WEIMAR SEXUAL SUBCULTURE, by Julie Nero. 2013Aviva Vogel Cohen Gabriel100% (1)

- ROSEN. Nihilism - A Philosophical EssayDocument261 pagesROSEN. Nihilism - A Philosophical EssayMas Será O Benedito100% (6)

- Dispensationalism ExaminedDocument67 pagesDispensationalism Examinedthelightheartedcalvinist6903Pas encore d'évaluation

- Worm Work - IntroductionDocument15 pagesWorm Work - Introductionynotg3Pas encore d'évaluation

- HUTCHINS - Cognition in The WildDocument7 pagesHUTCHINS - Cognition in The WildPalak GadodiaPas encore d'évaluation

- About "Macario"Document2 pagesAbout "Macario"Elysia ReyesPas encore d'évaluation

- Science Fiction Studies - 001 - Vol. 1, No. 1, Spring, 1973Document50 pagesScience Fiction Studies - 001 - Vol. 1, No. 1, Spring, 1973Michel DawPas encore d'évaluation

- Yesterday Never Dies: A Romance of MetempsychosisD'EverandYesterday Never Dies: A Romance of MetempsychosisÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (3)

- Annus On The Origin of Watchers Comparative Study of Antediluvian Wisdom in Mesopotamian Jewish TraditionsDocument45 pagesAnnus On The Origin of Watchers Comparative Study of Antediluvian Wisdom in Mesopotamian Jewish Traditionsjoegeddes100% (1)

- Kuznetsov EinsteinDocument387 pagesKuznetsov EinsteinIván Sanchez RojoPas encore d'évaluation

- Science Fiction Studies, Vol. 1, No. 1, Spring, 1973Document50 pagesScience Fiction Studies, Vol. 1, No. 1, Spring, 1973Michel Daw100% (1)

- The Dream Culture of the Neanderthals: Guardians of the Ancient WisdomD'EverandThe Dream Culture of the Neanderthals: Guardians of the Ancient WisdomPas encore d'évaluation

- Clyde Kluckhohn - Myths and Rituals. A General TheoryDocument35 pagesClyde Kluckhohn - Myths and Rituals. A General TheoryRob ThuhuPas encore d'évaluation

- MartinismDocument12 pagesMartinismStephan WozniakPas encore d'évaluation

- Jeffrey Cohen Monster Theory Reading CultureDocument47 pagesJeffrey Cohen Monster Theory Reading CulturePaula PepePas encore d'évaluation

- World of Yesterday: An Autobiography, by Stefan ZweigDocument16 pagesWorld of Yesterday: An Autobiography, by Stefan ZweigAviva Vogel Cohen Gabriel100% (2)

- Paul Klee's Pictorial Writing, by K. Porter Aichele. Cambridge University Press, 2002Document0 pagePaul Klee's Pictorial Writing, by K. Porter Aichele. Cambridge University Press, 2002Aviva Vogel Cohen Gabriel100% (3)

- Instruments To Perform Color (In 20th Century Music)Document10 pagesInstruments To Perform Color (In 20th Century Music)Aviva Vogel Cohen GabrielPas encore d'évaluation

- Crapanzano The Life History in Anthropological Field WorkDocument5 pagesCrapanzano The Life History in Anthropological Field WorkOlavo SouzaPas encore d'évaluation

- Asemic WritingDocument2 pagesAsemic WritingAviva Vogel Cohen GabrielPas encore d'évaluation

- Aliens - The Anthropology of Science FictionDocument177 pagesAliens - The Anthropology of Science Fiction1n4r51ssPas encore d'évaluation

- Mandel - Myth of Science FictionDocument3 pagesMandel - Myth of Science Fictionredcloud111Pas encore d'évaluation

- The Anthropology of The AlienDocument9 pagesThe Anthropology of The Alientaqi taqaPas encore d'évaluation

- Do Scientific Objects Have A History? PASTEUR AND WHITEHEAD IN A BATH OF LÂCTIC ACIDDocument17 pagesDo Scientific Objects Have A History? PASTEUR AND WHITEHEAD IN A BATH OF LÂCTIC ACIDlivingtoolPas encore d'évaluation

- Wagner An Anthropology of The SubjectDocument290 pagesWagner An Anthropology of The SubjectCarlos GerrezPas encore d'évaluation

- TGB Well-Physics - March 19, 2014Document2 732 pagesTGB Well-Physics - March 19, 2014Lime CatPas encore d'évaluation

- Thesis Allegory of The CaveDocument8 pagesThesis Allegory of The Caveauroratuckernewyork100% (2)

- Metadrama Final Paper - MPKDocument16 pagesMetadrama Final Paper - MPKMakai Péter KristófPas encore d'évaluation

- Geertz - 1974 - From The Native's Point of View On The Nature oDocument21 pagesGeertz - 1974 - From The Native's Point of View On The Nature oNilaus von HornPas encore d'évaluation

- "Christ Plays in Ten Thousand Places" The Relationship of Logoi and Logos in Plotinus, Maximus and BeyondDocument18 pages"Christ Plays in Ten Thousand Places" The Relationship of Logoi and Logos in Plotinus, Maximus and BeyondMarian UngureanuPas encore d'évaluation

- Collins Sail On! Sail On! (Science Fiction Studies v30 2003)Document20 pagesCollins Sail On! Sail On! (Science Fiction Studies v30 2003)uhtoomPas encore d'évaluation

- SF-TH IncDocument9 pagesSF-TH IncLu_fibonacciPas encore d'évaluation

- SF and The Idea of HistoryDocument16 pagesSF and The Idea of HistoryRebird555Pas encore d'évaluation

- On Anthropological OptimismDocument11 pagesOn Anthropological OptimismRoger SansiPas encore d'évaluation

- Culture and History: Prolegomena to the Comparative Study of CivilizationsD'EverandCulture and History: Prolegomena to the Comparative Study of CivilizationsPas encore d'évaluation

- Лекція 3Document17 pagesЛекція 3Max KukurudzaPas encore d'évaluation

- Ons Ons Ons Ons On Science Fiction Cience Fiction Cience Fiction Cience Fiction Cience FictionDocument12 pagesOns Ons Ons Ons On Science Fiction Cience Fiction Cience Fiction Cience Fiction Cience FictionVansh DubeyPas encore d'évaluation

- Sex Character 00 We inDocument394 pagesSex Character 00 We inAmalia MariaPas encore d'évaluation

- 05 IntroductionDocument17 pages05 IntroductionNoman ShahzadPas encore d'évaluation

- Progress Vs Utopia Fredric JamesonDocument13 pagesProgress Vs Utopia Fredric JamesonÍcaro Moreno RamosPas encore d'évaluation

- Christopher S. Wood - Image and ThingDocument22 pagesChristopher S. Wood - Image and ThingSaarthak SinghPas encore d'évaluation

- Galinier - The Implicit Mythology of Rituals in A Mesoamerican Context PDFDocument18 pagesGalinier - The Implicit Mythology of Rituals in A Mesoamerican Context PDFAngel Sanchez GamboaPas encore d'évaluation

- The Science Fiction of Poetics and the Avant-Garde ImaginationD'EverandThe Science Fiction of Poetics and the Avant-Garde ImaginationPas encore d'évaluation

- Aldiss Ch1Document15 pagesAldiss Ch1Rocío V. RamírezPas encore d'évaluation

- Coleridge - Biografia Literaria - 10, 13, 14Document12 pagesColeridge - Biografia Literaria - 10, 13, 14AdamalexandraPas encore d'évaluation

- Henry Darger, BiographyDocument5 pagesHenry Darger, BiographyAviva Vogel Cohen GabrielPas encore d'évaluation

- Anxiety Disorders. Edited by Vladimir V. KalininDocument336 pagesAnxiety Disorders. Edited by Vladimir V. KalininAviva Vogel Cohen GabrielPas encore d'évaluation

- Weary Rings César VallejoDocument1 pageWeary Rings César VallejoAviva Vogel Cohen GabrielPas encore d'évaluation

- Clare Reilly: A Primitive Neo-Romantic in A Postmodern World. by Gail RossDocument10 pagesClare Reilly: A Primitive Neo-Romantic in A Postmodern World. by Gail RossAviva Vogel Cohen GabrielPas encore d'évaluation

- Sculpture As An Art FormDocument2 pagesSculpture As An Art FormAviva Vogel Cohen GabrielPas encore d'évaluation

- Photographers of The World: An Annotated List With PhotographsDocument199 pagesPhotographers of The World: An Annotated List With PhotographsAviva Vogel Cohen GabrielPas encore d'évaluation

- 2013 Asemic Writing: An International Perspective. Jeremy Balius. 2013Document33 pages2013 Asemic Writing: An International Perspective. Jeremy Balius. 2013Aviva Vogel Cohen GabrielPas encore d'évaluation

- Goethe, Faust, and Science. B. J. MacLennan. 2005 PDFDocument23 pagesGoethe, Faust, and Science. B. J. MacLennan. 2005 PDFAviva Vogel Cohen GabrielPas encore d'évaluation

- Canonization of Jazz + Creation of Non-Victorian Concepts of CultureDocument21 pagesCanonization of Jazz + Creation of Non-Victorian Concepts of CultureAviva Vogel Cohen GabrielPas encore d'évaluation

- ILUYENKORI and Roger Fixy, by Aviva Vogel Gabriel, March 14, 2009Document2 pagesILUYENKORI and Roger Fixy, by Aviva Vogel Gabriel, March 14, 2009Aviva Vogel Cohen GabrielPas encore d'évaluation

- Dada and Surrealism Documents, Dada 6, 1920, Ed. Tristan Tzara PDFDocument26 pagesDada and Surrealism Documents, Dada 6, 1920, Ed. Tristan Tzara PDFAviva Vogel Cohen GabrielPas encore d'évaluation

- The DSM Diagnostic Criteria For Pedophilia. Ray Blanchard. Arch Sex Behavior. 2009Document13 pagesThe DSM Diagnostic Criteria For Pedophilia. Ray Blanchard. Arch Sex Behavior. 2009Aviva Vogel Cohen GabrielPas encore d'évaluation

- Categories of Servitude and The Sense of Not Feeling Offended in The Thought of AkshemseddinDocument17 pagesCategories of Servitude and The Sense of Not Feeling Offended in The Thought of Akshemseddinsantonqadr0% (1)

- Visions, Revelation and Ministry - Gal 1.11-17Document13 pagesVisions, Revelation and Ministry - Gal 1.11-1731songofjoyPas encore d'évaluation

- DeityDocument24 pagesDeityNaimish AgarwalPas encore d'évaluation

- ARCH226 Questions 2Document4 pagesARCH226 Questions 2Meyman WaruwuPas encore d'évaluation

- The Last Moments of LifeDocument8 pagesThe Last Moments of LifeIslamicPathPas encore d'évaluation

- Discovering Your Identity in ChristDocument3 pagesDiscovering Your Identity in ChristPrecious WallenPas encore d'évaluation

- The OdysseyDocument1 pageThe Odysseyjazi aquinoPas encore d'évaluation

- 3 Types of Myths NotesDocument2 pages3 Types of Myths NotesjeffherbPas encore d'évaluation

- Orpheus and EurydiceDocument3 pagesOrpheus and EurydiceJOCELLEPas encore d'évaluation

- EDU315 Answer 10Document4 pagesEDU315 Answer 10MUHAMMAD HAIKAL NAGIBPas encore d'évaluation

- Greek Gods and Goddesses Fact SheetDocument3 pagesGreek Gods and Goddesses Fact SheetJerico Enetorio FuncionPas encore d'évaluation

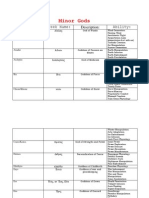

- Greek and Roman Minor Gods TableDocument7 pagesGreek and Roman Minor Gods TableHenreles HenriquePas encore d'évaluation

- Theatre of Tragedy - and When He Falleth LETRADocument2 pagesTheatre of Tragedy - and When He Falleth LETRAGabriel AguilarPas encore d'évaluation

- Rites and RitualsDocument12 pagesRites and RitualsHarikumar NairPas encore d'évaluation

- Skanda PuranamDocument6 pagesSkanda PuranamVishyPas encore d'évaluation

- Oral Exam EgyptDocument1 pageOral Exam EgyptMaría De Los Angeles PerezPas encore d'évaluation