Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Geometry and Architecture

Transféré par

Rabela JunejoDescription originale:

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Geometry and Architecture

Transféré par

Rabela JunejoDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

This article was downloaded by: [Orta Dogu Teknik Universitesi] On: 05 October 2011, At: 02:51 Publisher:

Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK

Architectural Theory Review

Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/ratr20

Geometry And Architecture

Stephen Frith

a a

Guest Editor

Available online: 06 Aug 2010

To cite this article: Stephen Frith (2010): Geometry And Architecture, Architectural Theory Review, 15:2, 107-109 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13264826.2010.495401

PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.tandfonline.com/page/terms-and-conditions This article may be used for research, teaching, and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, redistribution, reselling, loan, sub-licensing, systematic supply, or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The accuracy of any instructions, formulae, and drug doses should be independently verified with primary sources. The publisher shall not be liable for any loss, actions, claims, proceedings, demand, or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of this material.

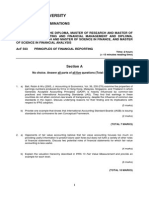

GUEST EDITORIAL

GEOMETRY AND ARCHITECTURE

Downloaded by [Orta Dogu Teknik Universitesi] at 02:51 05 October 2011

Architecture depends on geometry, yet it is an art of seduction that would never upset the senses by means of reason.1 In the beginning of Book 6 of his Ten Books on Architecture, Vitruvius tells us a story: When Aristippus, the Socratic philosopher, had been washed up on the shore of Rhodes after a shipwreck, and noticed that geometric diagrams had been drawn there, he is said to have exclaimed to his comrades: Let us hope for the best; I see human footprints! (VI.praef.1)2 Architecture mediated by geometry has for centuries been a major vehicle for the embodiment of order. Karsten Harries in an essay meditates on Cartesian space innitely extended, eliciting a response of freedom in the writings of Giordano Bruno, later giving rise to Kants rst antinomy: The world has a beginning in time, and is also limited as regards space opposing the contrary, The world has no beginning, and no limits in space; it is innite in regards both time and space. Harries argues that his antinomy haunts every attempt to construct space, every architecture,3 and that underlying our inhabitation of the world is a

ISSN 1326-4826 print/ISSN 1755-0475 online 2009 Taylor & Francis DOI: 10.1080/13264826.2010.495401

geometric construction, and asks Must we not domesticate space if we are to feel at home in it?4 Architectures role in this making the universe palatable can be seen to be dependent on a human will, but this perception is challenged by a geometry which generates architectural form, a capacity now easily available in software used commonly by architectural students. For some it carries with it a stigma, but also promises a thrill much like riding a bike with no hands. This collection of essays on the uses of geometry in architecture arose from a response to the increasing uses of generative geometry in the production of architectural designs in Australasian architecture schools. It was the subject of a symposium attached to the annual meeting of the Association of Architecture Schools of Australasia (AASA) in Canberra in 2008. Several of the papers rst made their appearance at this meeting, and others have been offered that assist the placing of this generative phenomena in an historical context. The keynote address for the AASA symposium was by Stephen Hyde, Professor of Mathematics at the Australian National University, who introduces his work on generative

FRITH

Downloaded by [Orta Dogu Teknik Universitesi] at 02:51 05 October 2011

geometries in mathematics. Michael Ostwald explores the uses of fractal geometries, at one point referring to them when misappropriated as a monster. The ambiguities of Albertis veil is explored by Brendan Murray, followed by the editors paper on Pascal and the relation between geometry and the rhetorical traditions. Philip Goad writes of the uses of polygonal geometry in twentieth century modernism, and Mitchell Whitelaw writes on recent architectural uses of space lling, with reference to his own artistic practice. Jane Burry examines the relation between architectural representation and its production, making a distinction between sensual and perceptual interpretation of architectural making. The special issue section concludes with reections of the potential of generative geometries in student work at the University of Technology Sydney (UTS) by Anthony Burke and Ben Hewitt. The uses of geometry in architecture tend to be instrumental, dovetailing with the process of building as a species of order. The modulation and arrangement of plans and the surfaces of elevations go hand in hand with this ction, but also depend upon geometrical play. This is an ancient habit, but one that has mutated since the eighteenth century in a period of increasing standardisation. The transformation of the historical uses of geometry in the rise of industrial civilisation is evident in a comparison of the construction of two Gothic church towers, one from the nineteenth century and the other from the twelfth to thirteenth centuries. The rst is by Edmund Blacket at St Stephens, Newtown in Sydney. It was built in Camperdown Cemetery in 1871-72, and is a testimony to the architectural poetry that Blacket achieved in his work. The geometry of the tower transforms from a square at its base to the point at its apex. The lower square

section is mediated throughout by an octagonal stair abutment, which takes the eye and stops at a large traceried vented opening whose geometry is dominated by the triangle of an applied gable. This masks the transformation of the geometry from the square to the octagon of the spire. The triangulation signies the most important place of transformation in the building. At this point, the stair resolves in its crenellations, a timid defence against some dark art. The coursing of the stone changes from the standardised one foot courses of the main wall that came from the stone-yard, to a foot and one half coursing for the remainder of the tower assisting the scaling of the spire and its reading from the ground. While Blacket is reliant on contemporary standardised measures from stone suppliers, his architecture celebrates this moment of transformation of stone and geometry by locating the churchs bells at this point, a nuanced collaboration of sound, geometry and architecture that was in part an outcome of his own studies of medieval exemplars. The second tower is from Chartres Cathedral outside of Paris, introduced to many students of architecture in Sydney in the 1970s by Dr John James. The geometry generates the form of the tower, even down to the details such as the angle and placing of the windows. The use of geometry in that culture had a sacral purpose, as if geometry carried the mind of an immanent god throughout matter. In this late medieval context, geometry and numbers became a speculation on the generative relation between geometry and the eternal creation of the world, informed by traditions deriving from ancient texts such as Platos Timaeus, as well as biblical sources, that taught that God ordered all things in measure and number and weight.5 The church fathers were the

108

ATR 15:2-10

GUEST EDITORIAL

other source of this afrmation, especially Augustine, who wrote The soul truly becomes better . . . when it turns away from the carnal senses and is re-formed by the divine numbers of wisdom. For thus it is said in Holy Scripture: I have made the circuit in order to know and contemplate and seek wisdom and number.6 John James own practice of architecture in the 1960s and 70s reected his extensive reNotes

1. Guarino Guarini, Architettura civile, Turin, 1737 (reprint, Milan: Il Polilo, 1968), p. 10. 2. Vitruvius, Ten Books, translated by Ingrid Rowland with commentary by T. N. Howe, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999, p. 75.

searches on geometry in the cathedrals of the Paris Basin, especially at Chartres.7 Teaching in Sydney schools of architecture with Peter Kollar of the University of New South Wales, and Adrian Snodgrass at the University of Sydney, their inspirational teaching regarding architecture and geometry at that time has in several respects led to this collection of papers.

Downloaded by [Orta Dogu Teknik Universitesi] at 02:51 05 October 2011

STEPHEN FRITH Guest Editor

3. Karsten Harries, Space as Construct, an Antinomy, in Peter MacKeith (ed.), Archipelago, essays on architecture , for Juhani Pallasmaa, Helsinki: Rakennustieto, 2006, pp. 8283. 4. Harries, Space as Construct, an Antinomy, p. 84.

5. Wisdom of Solomon 11:20. 6. St. Augustine, De Musica, VIiv.7. 7. John James, The Contractors of Chartres, Wyong: Mandorla Publications and London: Croom Helm, 1978.

109

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (894)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (587)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (344)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (119)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (399)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2219)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- Chapter 1 Capstone Case: New Century Wellness GroupDocument4 pagesChapter 1 Capstone Case: New Century Wellness GroupJC100% (7)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (73)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- The Legend of Lam-ang: How a Boy Avenged His Father and Won His BrideDocument3 pagesThe Legend of Lam-ang: How a Boy Avenged His Father and Won His Brideazyl76% (29)

- School Form 10 SF10 Learners Permanent Academic Record For Elementary SchoolDocument10 pagesSchool Form 10 SF10 Learners Permanent Academic Record For Elementary SchoolRene ManansalaPas encore d'évaluation

- KPMG Software Testing Services - GenericDocument24 pagesKPMG Software Testing Services - GenericmaheshsamuelPas encore d'évaluation

- 8098 pt1Document385 pages8098 pt1Hotib PerwiraPas encore d'évaluation

- Blueprint For The Development of Local Economies of SamarDocument72 pagesBlueprint For The Development of Local Economies of SamarJay LacsamanaPas encore d'évaluation

- Cityscapes PDFDocument2 pagesCityscapes PDFRabela JunejoPas encore d'évaluation

- The World of Ti Bet An Nomads Sept 14Document19 pagesThe World of Ti Bet An Nomads Sept 14Daniel MillerPas encore d'évaluation

- Personal Observations On Sindh PDFDocument410 pagesPersonal Observations On Sindh PDFRabela JunejoPas encore d'évaluation

- The Chachnamah Ancient History of SindhDocument181 pagesThe Chachnamah Ancient History of SindhSani Panhwar100% (4)

- An Ottoman Mentality The World of Evliya Celebi by Robert DankoffDocument305 pagesAn Ottoman Mentality The World of Evliya Celebi by Robert Dankoffmp190100% (2)

- Persian Wars and Burning of PersepolisDocument17 pagesPersian Wars and Burning of PersepolisRabela JunejoPas encore d'évaluation

- Notes From The UndergroundDocument88 pagesNotes From The UndergroundRabela JunejoPas encore d'évaluation

- Cityscapes PDFDocument2 pagesCityscapes PDFRabela JunejoPas encore d'évaluation

- Term PaGEOMETRY IN ISLAMIC ART AND ARCHITECTUREDocument23 pagesTerm PaGEOMETRY IN ISLAMIC ART AND ARCHITECTURERabela JunejoPas encore d'évaluation

- The Culture of Caravanserai:: Trade Along Anatolian Silk Route/RoadDocument16 pagesThe Culture of Caravanserai:: Trade Along Anatolian Silk Route/RoadRabela JunejoPas encore d'évaluation

- C"The Image of An Ottoman City: Imperial Architecture and Urban Experience in Aleppo in The 16th and 17th Centuries"OMMETARY PDFDocument3 pagesC"The Image of An Ottoman City: Imperial Architecture and Urban Experience in Aleppo in The 16th and 17th Centuries"OMMETARY PDFRabela JunejoPas encore d'évaluation

- Ah-501 HegelDocument5 pagesAh-501 HegelRabela JunejoPas encore d'évaluation

- SAS HB 06 Weapons ID ch1 PDFDocument20 pagesSAS HB 06 Weapons ID ch1 PDFChris EfstathiouPas encore d'évaluation

- Lancaster University: January 2014 ExaminationsDocument6 pagesLancaster University: January 2014 Examinationswhaza7890% (1)

- Todd Pace Court DocketDocument12 pagesTodd Pace Court DocketKUTV2NewsPas encore d'évaluation

- FTM Business Template - Margin AnalysisDocument9 pagesFTM Business Template - Margin AnalysisSofTools LimitedPas encore d'évaluation

- Summary of Kamban's RamayanaDocument4 pagesSummary of Kamban's RamayanaRaj VenugopalPas encore d'évaluation

- Aircraft Accident/Incident Summary Report: WASHINGTON, D.C. 20594Document14 pagesAircraft Accident/Incident Summary Report: WASHINGTON, D.C. 20594Harry NuryantoPas encore d'évaluation

- Encyclopædia Americana - Vol II PDFDocument620 pagesEncyclopædia Americana - Vol II PDFRodrigo SilvaPas encore d'évaluation

- Electronic Green Journal: TitleDocument3 pagesElectronic Green Journal: TitleFelix TitanPas encore d'évaluation

- Organizational ChartDocument1 pageOrganizational ChartPom tancoPas encore d'évaluation

- Key Concepts in Marketing: Maureen Castillo Dyna Enad Carelle Trisha Espital Ethel SilvaDocument35 pagesKey Concepts in Marketing: Maureen Castillo Dyna Enad Carelle Trisha Espital Ethel Silvasosoheart90Pas encore d'évaluation

- BCG Matrix Relative Market ShareDocument2 pagesBCG Matrix Relative Market ShareJan Gelera100% (1)

- Taxation of XYZ Ltd for 2020Document2 pagesTaxation of XYZ Ltd for 2020zhart1921Pas encore d'évaluation

- Tax Ii: Syllabus - Value-Added Tax Atty. Ma. Victoria A. Villaluz I. Nature of The VAT and Underlying LawsDocument12 pagesTax Ii: Syllabus - Value-Added Tax Atty. Ma. Victoria A. Villaluz I. Nature of The VAT and Underlying LawsChaPas encore d'évaluation

- Esmf 04052017 PDFDocument265 pagesEsmf 04052017 PDFRaju ReddyPas encore d'évaluation

- The History of Thoth 1Document4 pagesThe History of Thoth 1tempt10100% (1)

- Life Member ListDocument487 pagesLife Member Listpuiritii airPas encore d'évaluation

- Producer Organisations: Chris Penrose-BuckleyDocument201 pagesProducer Organisations: Chris Penrose-BuckleyOxfamPas encore d'évaluation

- Year 2019 Current Affairs - English - January To December 2019 MCQ by Sarkari Job News PDFDocument232 pagesYear 2019 Current Affairs - English - January To December 2019 MCQ by Sarkari Job News PDFAnujPas encore d'évaluation

- Catholic Theology ObjectivesDocument12 pagesCatholic Theology ObjectivesChristian Niel TaripePas encore d'évaluation

- 4-7. FLP Enterprises v. Dela Cruz (198093) PDFDocument8 pages4-7. FLP Enterprises v. Dela Cruz (198093) PDFKath LeenPas encore d'évaluation

- Human Resource Management: Functions and ObjectivesDocument26 pagesHuman Resource Management: Functions and ObjectivesABDUL RAZIQ REHANPas encore d'évaluation

- Hue University Faculty Labor ContractDocument3 pagesHue University Faculty Labor ContractĐặng Như ThànhPas encore d'évaluation

- LDN Mun BrgysDocument8 pagesLDN Mun BrgysNaimah LindaoPas encore d'évaluation

- European Gunnery's Impact on Artillery in 16th Century IndiaDocument9 pagesEuropean Gunnery's Impact on Artillery in 16th Century Indiaharry3196Pas encore d'évaluation