Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Analysis of The Film Burma VJ

Transféré par

marknickolasDescription originale:

Titre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Analysis of The Film Burma VJ

Transféré par

marknickolasDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Mark Nickolas New Directions in Documentary Prof.

Deirdre Boyle March 21, 2012

Midterm Exam: Burma VJ

This film is comprised largely of material shot by undercover reporters in Burma. Some elements of the film have been reconstructed in close co-operation with the actual persons involved, just as some names, places, and other recognizable facts have been altered for security reasons and in order to protect individuals. (opening titles in Burma VJ.) The 2010 Academy Award-nominated Burma VJ (2008) shined a bright spotlight on one of the worlds most repressive authoritarian regimes in the world with its powerful depiction of the anti-government protests of 2007 led by Buddhist monks and the brutal crackdown days later. Burma (officially, the Republic of the Union of Myanmar), which had been occupied by Japan during World War II, achieved independence from Great Britain in 1948, after more than 60 years of colonial rule. After struggling with several communist insurgencies in its post-independence period as a democratic republic, it fell into the hands of the military following a 1962 coup when the army overthrew the elected government rocked by economic crisis and ethnic conflict. What had been one of Southeast Asias wealthiest countries quickly became one of its most impoverished.1 Burmas current regime took power following another coup in 1988 when the army opened fire on peaceful, student-led, pro-democracy protesters, killing an estimated 3,000 people. In the intervening years, Burma regularly occupied the rungs of the most repressive and closed-societies in the world alongside North Korea, Cambodia, Laos, and China.2 In the years following the 1988 uprisings, a handful of Burmese expatriates living in Oslo, Norway (mainly former journalists and political activists) launched a non-profit media organization

Nickolas 2 called the Democratic Voice of Burma (DVB) to make broadcasts aimed at providing uncensored news about the country, its authoritarian rulers, and the political climate.3 At the time, the countrys political opposition was led by Aung San Suu Kyi, a former United Nations staffer who had returned home in 1988 to take care of her ailing mother, but soon found herself leading mass demonstrations for democracy in August 1988 (at one point addressing half a million people at a mass rally in Rangoon). In 1990, Suu Kyis National League for Democracy party won 59 percent of the national vote and 81 percent of the seats in Parliament. Quickly, the results were nullified by the military rulers and Suu Kyi was placed under house arrest, resulting in international condemnation. In 1991, she was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize.4 Democratic Voice of Burma Launched It was in this context that the Democratic Voice of Burma launched its efforts. DVB was initially founded as a radio station operated by a handful of staff and made its first broadcast into Burma by shortwave radio in July 1992. According to the media watchdog Reporters Without Borders, 63 percent of Burmese listen to DVB radio, which airs daily for two hours.5 In 2005, DVB received seed money to expand its work into television programming. According to its own website:6 DVB opened its television studios for the first time in 2005, setting out on a path that has revolutionized the way journalists operate in strictly controlled environments. More than any of our other media platforms, DVB television is dependent on our inside team, an 80-strong network of undercover video journalists, or VJs, that are spread throughout Burmas major urban areas and into the remote border regions. Seventeen of these men and women, some as young as 21, are in prison, serving

Nickolas 3 sentences from eight to 60-plus years. Many fall foul of the governments notorious Video and Electronics Acts, violation of which can result in double-digit jail terms. Footage collected by the VJs is sent via post, through proxy internet servers and sometimes on foot across the border to Thailand. This is then processed in our Thailand and Norway offices into news and feature packages and broadcast back into Burma via satellites in Europe, where it is watched by nearly 30% of the population. A Little 30 Minute Festival Thing It was following DVBs expansion into television in 2005 that they were approached by Norwegian filmmakers/producers Lise-Lense Moller and Jan Krogsgaard about a project.7 Soon, Danish filmmaker Anders Ostergaard joined the team as its director and began work on what he believed was nothing more than a modest film festival project: We started off with quite a small project about Joshuas daily life as a street reporter and the difficulties of getting any interesting material at all because of the obvious hazards and risks of bringing out a camera on the streets of Rangoon. We were going to have quite modest footage from his side and then add his own world to it in his own narration. It was going to be a little 30 minute festival thing. In the midst of this, there was this incredible coincidence [of the Saffron Revolution happening]. At the time that we met him, Joshua was a junior member of the group and not high profile or experienced. Suddenly, he was thrown into events in the way the film recounts, and he became a catalyst for bringing news in and out of Burma to the world media, which was an incredible rite of passage for him.8

Nickolas 4 As the project developed, dramatic fuel price increases led to a series of anti-government protests which became known as the Saffron Revolution. The short-lived campaign of civil resistance, led by Buddhist monks, were put down by way of a brutal crackdown by the government. In an instance, Ostergaards little festival thing would morph into a major and important work on the political developments of this secret country. Virtually closed to all outside media, the VJs disseminated to news outlets across the world the only documentation of the protests that shook the government, exposing Burmas civil rights abuses for all to see, as well as to be documented by Ostergaard. The film was narrated by a VJ named Joshua who remained unseen for safety purposes while hiding in Thailand (having been forced to flee Burma during filming) and the viewer watches the entire narrative unfold almost entirely through the captured video footage and a number of dramatic reenactments. Nick Dawson of Filmmaker magazine argues that Joshuas narration and the reenactments brings out the powerful dramatic aspects of this true story in a way that rivals any fiction film.9 But that was precisely one of the films problems. Controversy Despite its 2010 Academy Award nomination for Best Documentary Feature, Burma VJ generated controversy over its use of reenactments for several of the films most crucial scenes. The most noteworthy criticism came from TIME magazines Andrew Marshall: Burma VJ is pitched as a documentary, when it is actually a docudrama relying heavily on dramatic re-enactmentsMixing documentary footage with dramatic reconstructions is said to be a hallmark of Ostergaard's films. With Burma VJ, that hallmark is a handicap, undermining the film's credibility and dishonoring the very profession its subjects risk their lives to pursueNo scene is labeled as a

Nickolas 5 reconstruction. Some are convincingly real, yet others are so simply betrayed as reenactments by their wooden dialogue that soon I began to anxiously question the authenticity of every scene. I felt moved by a sequence showing protesters gathering on a Rangoon backstreet in defiance of the junta. But when I learned that it had been shot from scratch in the northern Thai city of Chiang Mai, I felt something else: manipulated. [] But it is still hard to simply recategorize Burma VJ as a well-made docudrama and leave it at that not as long as its makers insist that it is a documentary, or that it is composed largely of the work of undercover reporters, when at least half of it seems re-enacted. The cause of Burma's democrats is ill-served by hyperbole and the reconstruction of events to fit a version of the truth.10 Ostergaard, who studied journalism in Denmark before becoming a documentary filmmaker, commented in an interview11 how he views the separation between reporting and filmmaking: Im in documentary, which is related to journalism and theres a lot of method that is shared with journalism. Also, Im very keen on research understanding an issue before I describing it and I would less on intuitive or subjective understanding. But on the other hand Ive deliberately chosen not to work in journalism; I take liberties in my films which you can not take in journalistic. [] Its a great science to recreate the past, to make the past come alive, to be there as much as possible. This leads me to do a lot of reenactments, but Im always happiest when there is some authentic or original element to the reenactment, like a sound bite which I can then build the texture around. Basically I want to tell stories which have the full cinematic flow, the feeling of being there as a cinemagoer, just like any

Nickolas 6 feature film. And in order to achieve that narrative flow, you need reenactmentSome of them [telephone conversations] are original, others are reenacted but on the highest level of factuality. I would call them selfconstructions, in the sense that it was the real protagonists who relived their conversations some months after they took place.[] When you have this narrative ambition, you will of course get closer to the language of fiction films. Ive been working with this for quite some years now and a lot of my colleagues are doing that as well. Its not that we want to tell lies, its not that we want to fictionalize the world. It doesnt allow us to make up stories that never happened. What were trying to do is take factual events and represent them as richly and as directly as we can; thats why we resort to reenact. In another interview: I was very keen to follow Joshua as a protagonist and his story not only because of what he was going through but also because of his narrative skills, his ability to put everything together through his narration. When the whole uprising started there was no way we could just go to his safe house in Thailand and follow him because it would have been too much of a hazard to his safety; so the decision was made then to wait until the entire situation calmed down and then go later to redo the whole thing with him.12 Ostergaard told the New York Times that the film could not be told without reenactments: Im absolutely convinced there was no way to tell this story without reenactmentsNot only visually but on the soundtrack. The cellphone conversations obviously werent recorded at the time. In fact, the V.J.s wouldnt have

Nickolas 7 conversations while they were shooting. This is a cinematic distillation. But the content is authentic in the sense that we have the real guys telling each other what they told each other at the time.13 Finally, Ostergaards co-writer, Jan Krogsgaard, reiterated their thinking: Andrew Marshall of Time magazine criticised us for using re-enactments, but I think the broader message of the film is more importantEighty per cent of the material was recorded by VJs inside Burma. The re-enactments were done with the best intentions of honouring the dangerous work of the VJs. DVB gave us full support during the editing of the film by providing us with footage that was needed, making sure we didnt compromise VJs, and helping out with translations and contacts. 14 Ethical Issues Facing Documentary Filmmakers In 2009, Patricia Aufderheide and her colleagues at American Universitys Center for Social Media published the report Honest Truths: Documentary Filmmakers on Ethical Challenges in Their Work15 which examined, among other things, the ethical challenges facing documentary filmmakers when it came to issues such as reenactments and staging. The report was a summary of 45 long-form interviews in which filmmakers were asked to describe ethical challenges that surfaced in their recent work.16 One of them, documentarian and NYU film professor Sam Pollard, said that bending the truth in pursuit of story was legitimate: When Im working on a doc, I try not to lieBut that doesnt mean that I dont bend the truth. If youre a filmmaker you try to create a POV, you bend and shape the story to your agendaEspecially on a historical documentary, I keep to the facts.

Nickolas 8 But if you want to really explore it, you have to shape and bend. It depends on the project.17 Though, on the issue of staging and reenactments, filmmakers were split on what is permissible. Some argued that more trivial restaging actions (such as walking through a door) were not problematic since those were not what makes the story honest. Others believed that it was important that audiences be made aware somehow that the footage is recreated (which, despite Marshalls criticism of Burma VJ, the film opens with credits that explicitly acknowledge reenactments, suggesting that Marshalls beef is more about desiring a signal to the viewers before each such scene).18 Filmmaker Stanley Nelson argued that people have to know and feel its a recreation. You have to be 99.9 percent sure that people will know. Others admitted to staging events to occur at a time convenient to the filming and that as long as the activities they do are those they would normally be doing, if your filming doesnt distort their life... there is still a reality that is represented.19 But arguably more closely aligned with the choices Ostergaard made in Burma VJ was this comment from an unnamed filmmaker: I would not want to put words in peoples mouth, or edit them in a way thats not leading to the larger truth. But I feel like its important to get the big-picture truth of the situation on camera. The larger truth is that this conversation is going to happen in this city, at some point, and so it doesnt matter that it doesnt happen at this moment. The reports conclusion pointed to the lack of clarity and standards in ethical practice unlike those guiding traditional journalism. It also emphasized the strong overriding desire among

Nickolas 9 filmmakers for social justice and a higher truth, even at the expense of sometimes controversial editorial choices, with one filmmaker citing Picassos famous assertion that Art is a lie that makes us realize truth.20 This report reveals profound ethical conflicts informing the daily work of documentarians. The ethical conflicts they face loom large precisely because nonfiction filmmakers believe that they carry large responsibilities. They portray themselves as storytellers who tell important truths in a world where the truths they want to tell are often ignored or hidden. They believe that they come into a situation where their subjects, whether people or animals, are relatively powerless and they as media makershold some power. They believe that their viewers are dependent on their ethical choices. Many even see themselves as executors of a higher truth, framed within a narrative. Based on his interviews concerning the film, Ostergaards quest for higher truth appears to be that which drove his editorial choices in Burma VJ, especially considering the lack of available archival footage for some of the pivotal moments. The argument of what is appropriate in documentary is a permanent part of the forms DNA. Purists who hold documentarians to a standard similar to journalism fail to appreciate that even the most balanced and objective form of reporting is the product of countless editorial choices and decisions who gets interviewed, which quotes are used, which paragraphs are used first or last, how the information is presented, and which facts are used as the storys predicate in the first instance.

Nickolas 10 As Ive written before, I believe Patricia Aufderheide best captures the essence of what documentary filmmaking is all about: [D]ocumentaries are about real life; they are not real life. They are not even windows onto to real life. They are portraits of real life, using real life as their raw material, constructed by artists and technicians who make myriad decisions about what story to tell to whom, and for what purpose.21 Burma VJ again reminds us that while documentarys form, style, and content may be contentious, messy, and divisive, it remains one of the most powerful vehicles for shining light on the darkest corners of our humanity, as this film so powerfully does.

Nickolas 11

NOTES

1

Freedom in the World 2007: Burma. Freedom House. 2007. Web. 15 Mar. 2012 <http://www.freedomhouse.org/report/freedom-world/2007/burma>. Ibid. About DVB. Democratic Voice of Burma, n.d. Web. 15 Mar. 2011 <http://donate.dvb.no/>. Aung San Suu Kyi - Biography. Nobelprize.org. 15 Mar 2012 <http://www.nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/peace/laureates/1991/kyi-bio.html>. About DVB. Ibid. Konrad, Todd. Film Interview: Burma VJ. Vegas Outsider. 2 Mar. 2010. Web. 28 Feb. 2012 <http://www.vegas-outsider.com/articles/film/interviews/169-burma-vj-interview>. Dawson, Nick. Anders Ostergaard, Burma VJ. Filmmaker. 22 Feb 2010. Web. 28 Feb. 2012 <http://www.filmmakermagazine.com/news/2010/02/anders-stergaard-burma-vj-by-nickdawson/>. Ibid. Marshall, Andrew. Burma VJ: Truth as Casualty. TIME. 29 Jan. 2009. Web. 28 Feb. 2012 <http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,1874773,00.html>. Dawson. Konrad. Anderson, John. Monks, Tanks and Videotape. The New York Times. 17 May 2009. Web. 28 Feb. 2012 <http://www.nytimes.com/2009/05/17/movies/17ande.html>. Jensen, Stefan V. A peek behind the bamboo blinds. Southeast Asia Globe. 6 Jan. 2010. Web. 28 Feb. 2012 <http://www.sea-globe.com/Regional-Affairs/a-peek-behind-the-bamboo-blinds.html>. Aufderheide, Patricia, et al. Honest Truths: Documentary Filmmakers on Ethical Challenges in Their Work. Center for Social Media, American University School of Communications. Sep 2009. Web. 28 Feb. 2012 <http://www.centerforsocialmedia.org/making-your-media-matter/documents/bestpractices/honest-truths-documentary-filmmakers-ethical-chall>. Ibid, p. 1. Ibid, p. 17. Ibid. Ibid, p. 18. Ibid, p. 17. Aufderheide, Patricia. Documentary Film: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Press, 2007, p. 2.

2 3 4

5 6 7

10

11 12 13

14

15

16 17 18 19 20 21

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- No other way to tell it: Docudrama on film and television (second edition)D'EverandNo other way to tell it: Docudrama on film and television (second edition)Pas encore d'évaluation

- Notes On Veneration Without UnderstandingDocument3 pagesNotes On Veneration Without Understandingmma100% (2)

- Movie Minorities: Transnational Rights Advocacy and South Korean CinemaD'EverandMovie Minorities: Transnational Rights Advocacy and South Korean CinemaPas encore d'évaluation

- Journalist in FilmDocument278 pagesJournalist in FilmÁlvaro J. MalagónPas encore d'évaluation

- Naomi Schiller. Circulation and Meaning of The Revolution Will Not Be TelevisedDocument27 pagesNaomi Schiller. Circulation and Meaning of The Revolution Will Not Be TelevisedSeba MartinPas encore d'évaluation

- Alan Winnington - I Saw The Truth in KoreaDocument16 pagesAlan Winnington - I Saw The Truth in KoreaGabriel SansonPas encore d'évaluation

- Wires and Lights in A Box: How Edward R. Murrow Invented Broadcast JournalismDocument14 pagesWires and Lights in A Box: How Edward R. Murrow Invented Broadcast Journalismgot_chenPas encore d'évaluation

- Anna Mccarthy - Allen Funt Stanley Milgram and MeDocument25 pagesAnna Mccarthy - Allen Funt Stanley Milgram and MeKareem HassanPas encore d'évaluation

- Chapter 4Document6 pagesChapter 4Michael ChiuPas encore d'évaluation

- Fulltext PDFDocument73 pagesFulltext PDFAlexandru VladPas encore d'évaluation

- Evolution of Docu FilmsDocument73 pagesEvolution of Docu Filmsradu gorgosPas encore d'évaluation

- Nate ThayerDocument7 pagesNate ThayerGiorgio MattaPas encore d'évaluation

- Written Report On Burma's Media and Information InfrastructureDocument9 pagesWritten Report On Burma's Media and Information InfrastructureAllen ZafraPas encore d'évaluation

- Documentary and Film MakingDocument38 pagesDocumentary and Film MakingSurendra YadavPas encore d'évaluation

- Gendered (Re)Visions: Constructions of Gender in Audiovisual MediaD'EverandGendered (Re)Visions: Constructions of Gender in Audiovisual MediaPas encore d'évaluation

- DAVID HANAN Observational Cinema Comes TDocument11 pagesDAVID HANAN Observational Cinema Comes TlelakibudimanPas encore d'évaluation

- NullDocument14 pagesNullking salazahPas encore d'évaluation

- ETEC 531 Hotel Rwanda Media GuideDocument10 pagesETEC 531 Hotel Rwanda Media GuideBrettPas encore d'évaluation

- Arjun Mahadevan: DOC-CON ReviewDocument1 pageArjun Mahadevan: DOC-CON Reviewrevolutionary socialism in the 21st centuryPas encore d'évaluation

- Writing For Documentary Academic ScriptDocument12 pagesWriting For Documentary Academic ScriptNitin KumarPas encore d'évaluation

- Alexa Milan Modern Portrayals of Journalism in FilmDocument12 pagesAlexa Milan Modern Portrayals of Journalism in FilmNICK ALETRASPas encore d'évaluation

- SCMS ACTIVIST AND REVOLUTIONARY FILM AND MEDIA SCHOLARLY INTEREST GROUP Founded in 2019Document8 pagesSCMS ACTIVIST AND REVOLUTIONARY FILM AND MEDIA SCHOLARLY INTEREST GROUP Founded in 2019Mathilde DmPas encore d'évaluation

- Image Brokers: Visualizing World News in the Age of Digital CirculationD'EverandImage Brokers: Visualizing World News in the Age of Digital CirculationPas encore d'évaluation

- History's Role in Japanese Horror CinemaDocument16 pagesHistory's Role in Japanese Horror CinemaMiharuChan100% (1)

- Documentary ClassDocument17 pagesDocumentary ClassSaumyaPas encore d'évaluation

- Cinema Solidarity The Documentary Practice of Kim LonginottoDocument10 pagesCinema Solidarity The Documentary Practice of Kim Longinottomartinha69Pas encore d'évaluation

- The Representation of Media Critics in Dan Gilroy'S Movie NightcrawlerDocument14 pagesThe Representation of Media Critics in Dan Gilroy'S Movie NightcrawlercupbmcmPas encore d'évaluation

- The Humanity of Evil Bahai Reflections oDocument44 pagesThe Humanity of Evil Bahai Reflections oBernardo Bortolin KerrPas encore d'évaluation

- 5 DocumentariansDocument6 pages5 Documentariansapi-299391331Pas encore d'évaluation

- History of DocumentariesDocument9 pagesHistory of DocumentariesRas GillPas encore d'évaluation

- History of DocumentariesDocument9 pagesHistory of DocumentariesRas GillPas encore d'évaluation

- Post-Communist Malaise: Cinematic Responses to European IntegrationD'EverandPost-Communist Malaise: Cinematic Responses to European IntegrationPas encore d'évaluation

- Brink of Reality: New Canadian Documentary Film and VideoD'EverandBrink of Reality: New Canadian Documentary Film and VideoPas encore d'évaluation

- Interrogating the Image: Movies and the World of Film and TelevisionD'EverandInterrogating the Image: Movies and the World of Film and TelevisionPas encore d'évaluation

- Filmmaking For Change..20 Page Sample PDFDocument24 pagesFilmmaking For Change..20 Page Sample PDFMichael Wiese Productions67% (3)

- Unit 12 - Writing Piece FinalDocument6 pagesUnit 12 - Writing Piece Finalapi-634157326Pas encore d'évaluation

- Macdougall2018 Observational CinemaDocument10 pagesMacdougall2018 Observational Cinemamentamenta100% (1)

- Film and History: A Very Long Engagement - Gianluca FantoniDocument23 pagesFilm and History: A Very Long Engagement - Gianluca Fantonidanielson3336888100% (1)

- Article N. Wanono Imaf Trad EngDocument15 pagesArticle N. Wanono Imaf Trad EngNadinePas encore d'évaluation

- Unit 5: Anthropology of The CinemaDocument24 pagesUnit 5: Anthropology of The CinemaRajendra MagarPas encore d'évaluation

- Image Bite PoliticsDocument333 pagesImage Bite PoliticsAdina PopaPas encore d'évaluation

- Killer Images: Documentary Film, Memory and the Performance of ViolenceD'EverandKiller Images: Documentary Film, Memory and the Performance of ViolenceÉvaluation : 5 sur 5 étoiles5/5 (1)

- "First To Fight!" Playing Your Identity, Hooking Your Desire and BodyDocument18 pages"First To Fight!" Playing Your Identity, Hooking Your Desire and BodyarunabandaraPas encore d'évaluation

- Krenik - Academic Essay MA70079ODocument7 pagesKrenik - Academic Essay MA70079OAnnie KrenikPas encore d'évaluation

- Chapter 3: The Documentary Genre. Approach and TypesDocument18 pagesChapter 3: The Documentary Genre. Approach and TypesEirini PyrpyliPas encore d'évaluation

- Sample Independent Study Proposal #1: DesireDocument4 pagesSample Independent Study Proposal #1: Desireabnou_223943920Pas encore d'évaluation

- The Corruption Behind Government Funded Animation in Twentieth-Century ChinaDocument16 pagesThe Corruption Behind Government Funded Animation in Twentieth-Century ChinaMark MullanPas encore d'évaluation

- An Inspiring Talk With Sotiris Danezis / by Passarivaki MariaDocument11 pagesAn Inspiring Talk With Sotiris Danezis / by Passarivaki MariaMaria PassarivakiPas encore d'évaluation

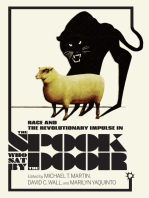

- Race and the Revolutionary Impulse in The Spook Who Sat by the DoorD'EverandRace and the Revolutionary Impulse in The Spook Who Sat by the DoorÉvaluation : 5 sur 5 étoiles5/5 (1)

- Radio Documentary On Child AbuseDocument41 pagesRadio Documentary On Child AbuseAdékúnlé Bínúyó100% (1)

- 1988 O'Connor ReflectionsDocument11 pages1988 O'Connor ReflectionsErica Hsu (Shih-chia)Pas encore d'évaluation

- The Effectivness of America Movie PropagandaDocument15 pagesThe Effectivness of America Movie PropagandaFaris PakriPas encore d'évaluation

- The Marginalization of Chinese Documentaries-FindingsDocument31 pagesThe Marginalization of Chinese Documentaries-Findingswenrui sunPas encore d'évaluation

- My Lai Massacre As A Media CHDocument27 pagesMy Lai Massacre As A Media CHSaurav DattaPas encore d'évaluation

- Chris Marker and Documentary Filmmaking 1962-1982 (PHD Thesis)Document266 pagesChris Marker and Documentary Filmmaking 1962-1982 (PHD Thesis)aaaaahhh100% (1)

- Documentary and ReportDocument8 pagesDocumentary and ReportAna MartínezPas encore d'évaluation

- Date: May 25, 2009 01:35AMDocument35 pagesDate: May 25, 2009 01:35AMDominique HoffmanPas encore d'évaluation

- Adv English - V For VendettaDocument9 pagesAdv English - V For VendettaAria SuzukiPas encore d'évaluation

- 128-World Media ScenarioDocument57 pages128-World Media ScenarioHappyPas encore d'évaluation

- Narrative and Media PDFDocument343 pagesNarrative and Media PDFLaura Rejón López100% (2)

- 120990-Article Text-332804-1-10-20150818 PDFDocument7 pages120990-Article Text-332804-1-10-20150818 PDFanvesha khillarPas encore d'évaluation

- Shock and Awe - NDocument5 pagesShock and Awe - NnaomiPas encore d'évaluation

- Документ Microsoft WordDocument5 pagesДокумент Microsoft WordAlex RacuPas encore d'évaluation

- Heritage KattabommanDocument8 pagesHeritage KattabommanElango Maran R SPas encore d'évaluation

- Reading Guide Spain's EmpireDocument2 pagesReading Guide Spain's EmpireDown2000Pas encore d'évaluation

- The Involvement of Milf Against The Philippine Government: An AnalysisDocument17 pagesThe Involvement of Milf Against The Philippine Government: An AnalysisJerome EncinaresPas encore d'évaluation

- SMUN16 NATO Study GuideDocument37 pagesSMUN16 NATO Study GuidelimliyiPas encore d'évaluation

- Baharistan PDFDocument168 pagesBaharistan PDFKushal RaoPas encore d'évaluation

- 300 Spartans FieraDocument2 pages300 Spartans FieraFiera RiandiniPas encore d'évaluation

- AS - WS 3 - VII - Hist - The Great Uprising of 1857Document1 pageAS - WS 3 - VII - Hist - The Great Uprising of 1857Sachi PatelPas encore d'évaluation

- CBSE Class 12 History Rebels The Raj 1857 Revolt Representations PDFDocument3 pagesCBSE Class 12 History Rebels The Raj 1857 Revolt Representations PDFKismati YadavPas encore d'évaluation

- Battle of Mursa MajorDocument3 pagesBattle of Mursa MajorHenk Vervaeke100% (2)

- Big Bear Vs PoundmakerDocument7 pagesBig Bear Vs Poundmakerapi-306104023Pas encore d'évaluation

- Skill: Causation)Document4 pagesSkill: Causation)api-391205226Pas encore d'évaluation

- Freemasons in JapanDocument3 pagesFreemasons in JapanMichael GreenPas encore d'évaluation

- Quit India MovementDocument7 pagesQuit India MovementtejasPas encore d'évaluation

- 5 Washington AdamsDocument41 pages5 Washington Adamsapi-294843376Pas encore d'évaluation

- Alicia Simpson, Byzantium's Retreating Balkan Frontiers During The Reign of The Angeloi (1185-1203) PDFDocument20 pagesAlicia Simpson, Byzantium's Retreating Balkan Frontiers During The Reign of The Angeloi (1185-1203) PDFMehmet YağcıPas encore d'évaluation

- Measures of Empire Tax Farmers and The Ottoman Ancien Regime, 1695-1807Document9 pagesMeasures of Empire Tax Farmers and The Ottoman Ancien Regime, 1695-1807dragakhalPas encore d'évaluation

- The Turning Point: What Civil War Battle Most Influenced The Outcome of The War?Document5 pagesThe Turning Point: What Civil War Battle Most Influenced The Outcome of The War?kadenandrePas encore d'évaluation

- BookpartDocument35 pagesBookpartxdboy2006Pas encore d'évaluation

- The Art of The RevolutionDocument4 pagesThe Art of The Revolutionapi-461067605Pas encore d'évaluation

- Battle of BuxarDocument41 pagesBattle of BuxarumeshPas encore d'évaluation

- Louis VxiDocument5 pagesLouis VxiTwinkle AgarwalPas encore d'évaluation

- The MapDocument2 pagesThe MapMaria Lou JundisPas encore d'évaluation

- Filipino Revolts Against SpainDocument4 pagesFilipino Revolts Against SpainFaith GregorioPas encore d'évaluation

- The Qissa Khwani Bazaar MassacreDocument3 pagesThe Qissa Khwani Bazaar MassacreQissa KhwaniPas encore d'évaluation

- Emerging NationalismDocument7 pagesEmerging NationalismAngela ReverezaPas encore d'évaluation

- Kas 1 3rd Exam ReviewerDocument16 pagesKas 1 3rd Exam ReviewerAgatha Uy100% (1)

- Ukraine's President Declares A 'Coup' and Refuses To ResignDocument5 pagesUkraine's President Declares A 'Coup' and Refuses To ResignThavamPas encore d'évaluation