Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Jpn. J. Clin. Oncol. 2013 Tomioka Jjco - Hyt021

Transféré par

Carlos Alberto CastañedaDescription originale:

Titre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Jpn. J. Clin. Oncol. 2013 Tomioka Jjco - Hyt021

Transféré par

Carlos Alberto CastañedaDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Japanese Journal of Clinical Oncology Advance Access published February 26, 2013

Jpn J Clin Oncol 2013 doi:10.1093/jjco/hyt021

Original Article

Observation as an Option for Epithelial Positive Margin after Partial Glossectomy in Stage I and II Squamous Cell Carcinoma: Analysis of 365 Cases

Toshifumi Tomioka1,*, Ryuichi Hayashi1, Mitsuru Ebihara1, Masakazu Miyazaki1, Takeshi Shinozaki1 and Satoshi Fujii2

Department of Head and Neck Surgery, National Cancer Center Hospital East Kashiwa, and 2Pathology Division, Research Center for Innovative Oncology, National Cancer Center Hospital East, Kashiwa, Japan *For reprints and all correspondence: Toshifumi Tomioka, Department of Head and Neck Surgery, National Cancer Center Hospital East, 6-5-1 Kashiwanoha, Kashiwa, Chiba 277-8577, Japan. E-mail: totomiok@east.ncc.go.jp

Received July 26, 2012; accepted January 30, 2013

1

Downloaded from http://jjco.oxfordjournals.org/ at Universidad de Antioquia on April 2, 2013

Objective: This study was conducted to assess local recurrence and clinical prognosis in patients diagnosed as having a positive margin in the epithelial layer after a partial glossectomy treated by close observation. Methods: A total of 365 cases of squamous cell carcinoma of the tongue diagnosed as clinical Stage I or II, treated by partial glossectomy in the National Cancer Center Hospital East between 1992 and 2006, were studied retrospectively. Results: Pathological ndings showed that 13 cases had positive margins in the epithelial layer, 4 (30.8%) of whom showed up with local recurrence in 4.4 years (3.0 5.0) on average. Lymph node recurrence was not observed and the 5-year overall survival rate was 76.2% in those 13 cases. The treatment for the recurrent cases was an additional partial glossectomy without neck dissection, which resulted in no recurrence and a survival rate of 100% after an average follow-up of 6.7 years. Conclusions: We suggest careful observation as one option for cases diagnosed with epithelial positive margin. Key words: partial glossectomy epithelial positive margin close observation

INTRODUCTION

Surgeons generally perform a partial glossectomy with 10 15-mm free margins; however, there are cases determined to be histopathologically positive at a certain rate. Several studies reported (1 3) that the additional treatments improve the 5-year survival rate when the histopathological ndings show a deep positive margin, but so far there is no report focusing on treatment when the positive margin is only found in the epithelial layer. This retrospective study assesses the prognosis and recurrence rate of cases with positive epithelial margin to determine whether careful and close observation is proper for these cases.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

The patients included in this study were drawn from the database of the Department of Head and Neck Surgery of the National Cancer Center Hospital East, Kashiwa, Japan between 1992 and 2006. Eight hundred and ten cases of squamous cell carcinoma (SqCC) of the tongue underwent a glossectomy, which included 368 cases diagnosed as having Stage I or II. Among those, 365 cases received an intraoral partial glossectomy without neck dissection. The retrospective study was conducted on these cases, which included 213 males and 152 females. The average age was 60.2 years, while the median age was 61 years (range, 20 93 years).

# The Author 2013. Published by Oxford University Press. All rights reserved. For Permissions, please email: journals.permissions@oup.com

Page 2 of 4

Positive margin after partial glossectomy

The preoperative clinical staging was based on the sixth edition of the UICC (Union for International Cancer Control) TNM, Stage I in 169 cases and Stage II in 196 cases. We sliced the surgical specimens at intervals of every 4 mm after formalin xation. As a general rule, we sliced coronal direction, and sliced sagittal direction about both ends of the specimen additionally. We examined all slices of specimens. In this study, we dened carcinoma cells that are positive at the cut end (i.e. 0 mm) as positive margin. In the case of a suspected positive margin, we sliced a deeper segment and undertook an advanced examination. We presented pathological pictures with a close margin (Fig. 1A and B) and with a positive margin (Fig. 1C and D). The patients were classied into three groups according to pathologic ndings: A with a complete resection, B with a positive deep margin and C with a positive margin only in the epithelium. Cases showing the close margin without the expose of cancer cells were classied as Group A. Also, cases with dysplasia (moderate, mild) at the margin were classied as Group A. Cases with a positive margin deeper than the epithelium or cases in both the epithelium and deeper layers were classied as Group B. Cases with positive margins only in the epithelium (severe dysplasia, carcinoma in situ) were classied as Group C. Statistical signicance was set at P , 0.05. The analyses were performed using SPSS statistical software. A Kaplan Meier method with the log-rank test was applied to analyse the statistical signicance between the three groups with regard to local recurrence.

During the glossectomy, we held a common basic policy to set the resection line at least 10 15 mm from the edge of the tumor. Whenever the lining mucosa had any irregular surface, the region was resected as well. Intraoperative histopathology examinations were performed whenever positive margins were suspected. After operation, we informed all patients of pathological ndings in detail. Then, for patients with positive margins we recommended additional excision or adjuvant treatment. If the patients do not prefer to receive those, next we proposed careful and close observation as an option. In this study, no patient of Group C underwent the additional treatment, but chose close observation. In Group B, 16 patients underwent the additional treatment (14 patients received additional excision, one patient adjuvant chemotherapy, one patient radiation therapy) and 9 patients did not accept any additional treatment but underwent close observation.

Downloaded from http://jjco.oxfordjournals.org/ at Universidad de Antioquia on April 2, 2013

RESULTS

Among all 365 cases, there were 327 cases with a complete resection (Group A), 25 cases with a positive deep margin (Group B) and 13 cases with positive margins only in the epithelium (Group C). There was no statistical signicance in stage, age, differentiation, gender, vascular invasion and perineural invasion, tumor size between the three groups (Table 1).

Figure 1. (A) The carcinoma cells exist closely to cut end. (B) The burning effect on carcinoma cells is almost none. (C) The carcinoma cells are positive at the cut end. (D) The remarkable burning effect on carcinoma cells is observed.

Jpn J Clin Oncol 2013

Page 3 of 4

Table 1. Data on 365 patients Complete resection Total Sex Men Women Age (years) Average 55.1 62.8 71.5 189 138 18 7 6 7 327 Positive deep margin 25 Positive margins only in the epithelium 13

Table 2. Local recurrence Complete resection No local recurrence Local recurrence Local recurrent rate Time to local recurrence 308 19 5.8% 1.8 years (0.15.8 years) Positive deep margin 17 8 32.0% 1.4 years (0.3 3.1 years) Positive margins only in the epithelium 9 4 30.8% 4.4 years (3.05.0 years)

Tumor classication I II Differentiation Well Moderate Poor 239 120 14 15 7 3 8 5 0 155 172 7 18 7 6

Time to local recurrence: average (range).

Downloaded from http://jjco.oxfordjournals.org/ at Universidad de Antioquia on April 2, 2013

Table 3. Regional recurrence Complete resection No regional recurrence 239 1 1 0 Regional recurrent Regional recurrent rate 88 26.9% Positive deep margin 17 8 32.0% Positive margins only in the epithelium 13 0 0.0%

Lymphovascular invasion/perineural invasion ly( ) v( ) pn( ) 43 114 39 9 11 6

Tumor size (mm, average) Long axis Short axis Thickness 21.5 15.4 5.4 21.3 16.2 8.0 23.1 16.1 5.2

LOCAL RECURRENCE Local recurrence was dened as the tumor development at the site of the primary tumor. The mean follow-up period was 5.8 years. The rate of local recurrence was 5.8% in Group A, 32.0% in Group B and 30.8% in Group C. The difference was statistically signicant between Groups A and B (P , 0.001) and between Groups A and C (P 0.0019) (Table 2). The average period until the diagnosis of local recurrence was 1.8 years in Group A, 1.4 years in Group B and 4.4 years in Group C; only Groups B and C showed a signicant difference (P 0.007) (Table 2). LYMPH NODE RECURRENCE The lymph node recurrence rate was 26.9% in Group A, 32.0% in Group B and 0% in Group C. There was no signicant difference in the comparison of Groups A and B (Table 3). PROGNOSIS The 5-year overall survival rate was as follows: 72.2% in Group A, 73.7% in Group B and 76.2% in Group C. There was no signicant difference between each group (Fig. 2).

All cases with local recurrence in Group C were treated by an additional intraoral partial glossectomy. Up to February 2011, all of them have survived more than 5 years without showing recurrence (a mean follow-up of 68 months, median 68 months). Causes of deaths (all patients): 18.1% of the patients died from another disease, 8.2% from primary disease (neck lymph node) and 1.6% from primary disease (tongue).

DISCUSSION

As a matter of course, a complete resection of the primary lesion is the main objective of surgical treatment. An intraoperative frozen section is one of the important procedure to achieve a complete resection (4). But it is also true that although surgeons perform a partial glossectomy with 10 15-mm free margins, there are cases determined to be histopathologically positive at a certain rate. The rate of a positive margin in this study was 10.4%, which is not high comparing with the other report by Bonnardot et al. (5), but still not zero. As this study shows, there is a signicant difference in the recurrence rate between cases with a complete resection and those with positive margins and so additional treatment such as surgical resection or radiation therapy is recommended. Zelefsky et al. (6) reported that postoperative radiation therapy is useful for cases with positive margins. On the other hand, since external radiation therapy includes the whole extensive area surrounding the primary lesion, there is a discussion that its benet does not exceed its side effects (7) or that it turns into exceed treatment. Also its indication

Page 4 of 4

Positive margin after partial glossectomy

of accuracy towing to the intraoperative decision. In contrast, an intraoperative frozen section would be much more reliable for a complete resection (7). This study shows that recurrence among cases with an epithelial positive margin is only seen at the primary lesion, not all cases showed local recurrence (its recurrence rate is 30.2%), the time to the recurrence is signicantly long, all cases with recurrence were curable with an additional resection and there was no prognostic difference. This encourages us to suggest a careful follow-up observation and a surgical resection after local recurrence as reasonable options for cases with an epithelial positive margin.

Downloaded from http://jjco.oxfordjournals.org/ at Universidad de Antioquia on April 2, 2013

Figure 2. Overall survival rate. Blue line is group A, green line is group B and red line is group C.

CONCLUSION

Close observation can be suggested as one option for cases of SqCC of the tongue diagnosed as having clinical Stage I or II with an epithelial positive margin after a partial glossectomy.

in cases with multiple primaries is controversial. At this point, secondary surgery is much less invasive, even regarding that resection is held including the surrounding area because there is a problem of relocating the site of the frozen section which sometimes leads to the additional resection of an inappropriate site (8). There is a point of view that Group C can be treated with additional excision, which is not a major surgery, but it is not always easy to detect the precise location where the margin was positive in a pathological specimen (8). The fact that the margin turned out to be positive despite primary resection was conrmed by Lugol staining, suggesting that limited surgery might not be enough and extended resection might be required oncologically. The rate of local recurrence does not support the validity to give additional excision in all cases, since about 70% of the cases did not show any recurrence. Additionally, all of the cases which had recurrence in Group C were salvaged, which support that a close observation is a reasonable option considering the benet for patients. The 25 cases in Group B were all assessed carefully with computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging preoperatively, and was resected with enough free margin from the tumor. Among the three groups, it had the highest rate of local recurrence, lymph node recurrence and lowest 5-year survival rate. This supports that the additional treatment such as an extended resection with or without reconstruction, neck dissection, or postoperative radiation therapy are needed (6). For the advanced recurrence cases, chemoradiation therapy is needed in addition to postoperative adjuvant therapies (9). Focusing on the 13 cases in Group C with an epithelial positive margin, the positive margin was at the tip of the tongue (three cases), dorsal edge (four cases), oral oor (eight cases) and at the pharynx side (four cases). The margins were not considered as positive during surgery macroscopically, but turned out to be pathologically positive. Evaluation with Lugols spraying (10) or narrow banding imaging (11) would be helpful at the oral oor, but these ndings in the dorsal edge or root of the tongue show a lack

Conict of interest statement

None declared.

References

1. Binahmed A, Nason RW, Abdoh AA. The clinical signicance of the positive surgical margin in oral cancer. Oral Oncol 2007;43:780 4. 2. Huang TY, Hsu LP, Wen YH, et al. Predictors of locoregional recurrence in early stage oral cavity cancer with free surgical margins. Oral Oncol 2010;46:4955. 3. Rusthoven K, Ballonoff A, Raben D, Chen C. Poor prognosis in patients with stage I and II oral tongue squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer 2008;112:345 51. 4. DiNardo LJ, Lin J, Karageorge LS, Powers CN. Accuracy, utility, and cost of frozen section margins in head and neck cancer surgery. Laryngoscope 2000;110(10 Pt 1):1773 6. 5. Bonnardot L, Bardet E, Steichen O, et al. Prognostic factors for T1-T2 squamous cell carcinomas of the mobile tongue: a retrospective cohort study. Head Neck 2011;33:92834. 6. Zelefsky MJ, Harrison LB, Fass DE, Armstrong JG, Shah JP, Strong EW. Postoperative radiation therapy for squamous cell carcinomas of the oral cavity and oropharynx: impact of therapy on patients with positive surgical margins. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 1993;25:17 21. 7. Palazzi M, Tomatis S, Orlandi E, et al. Effects of treatment intensication on acute local toxicity during radiotherapy for head and neck cancer: prospective observational study validating CTCAE, version 3.0, scoring system. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2008; 70:330 7. 8. Kerawala CJ, Ong TK. Relocating the site of frozen sectionsis there room for improvement? Head Neck 2001;23:230 2. 9. Bernier J, Cooper JS, Pajak TF, et al. Dening risk levels in locally advanced head and neck cancers: a comparative analysis of concurrent postoperative radiation plus chemotherapy trials of the EORTC (#22931) and RTOG (# 9501). Head Neck 2005;27:84350. 10. Umeda M, Shigeta T, Takahashi H, et al. Clinical evaluation of Lugols iodine staining in the treatment of stage I II squamous cell carcinoma of the tongue. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2011;40:5936. 11. Lin YC, Wang WH, Lee KF, Tsai WC, Weng HH. Value of narrow band imaging endoscopy in early mucosal head and neck cancer. Head Neck 2012;34:1574 9.

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- AssociationDocument10 pagesAssociationCarlos Alberto CastañedaPas encore d'évaluation

- Dental Caries StrategiesDocument23 pagesDental Caries StrategiesCarlos Alberto CastañedaPas encore d'évaluation

- Shear Bond Strength of Glass Lonomer Cement To Silver Diamine Fluoride-Treated Artificial Dentinal CariesDocument6 pagesShear Bond Strength of Glass Lonomer Cement To Silver Diamine Fluoride-Treated Artificial Dentinal CariesCarlos Alberto CastañedaPas encore d'évaluation

- Maxillary Transverse DeficiencyDocument4 pagesMaxillary Transverse DeficiencyCarlos Alberto CastañedaPas encore d'évaluation

- Clinical Practice: The Approach To The Deaf or Hard-Of-Hearing Paediatric PatientDocument5 pagesClinical Practice: The Approach To The Deaf or Hard-Of-Hearing Paediatric PatientCarlos Alberto CastañedaPas encore d'évaluation

- Black Triangle Dilemma and Its Management in Esthetic DentistryDocument7 pagesBlack Triangle Dilemma and Its Management in Esthetic DentistryCarlos Alberto CastañedaPas encore d'évaluation

- Handbook of OrthodonticsDocument1 pageHandbook of OrthodonticsCarlos Alberto CastañedaPas encore d'évaluation

- Regenerative Therapies For Equine Degenerative Joint Disease: A Preliminary StudyDocument11 pagesRegenerative Therapies For Equine Degenerative Joint Disease: A Preliminary StudyCarlos Alberto CastañedaPas encore d'évaluation

- ARVO Annual Meeting AbstractDocument1 pageARVO Annual Meeting AbstractCarlos Alberto CastañedaPas encore d'évaluation

- ARVO Annual Meeting AbstractDocument1 pageARVO Annual Meeting AbstractCarlos Alberto CastañedaPas encore d'évaluation

- OscarceballosDocument1 pageOscarceballosCarlos Alberto CastañedaPas encore d'évaluation

- Is Paromomycin An Effective and Safe Treatment Against Cutaneous Leishmaniasis? A Meta-Analysis of 14 Randomized Controlled TrialsDocument10 pagesIs Paromomycin An Effective and Safe Treatment Against Cutaneous Leishmaniasis? A Meta-Analysis of 14 Randomized Controlled TrialsCarlos Alberto CastañedaPas encore d'évaluation

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (400)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (588)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (895)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (266)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (345)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)

- 4-ProjectCharterTemplatePDF 0Document5 pages4-ProjectCharterTemplatePDF 0maria shintaPas encore d'évaluation

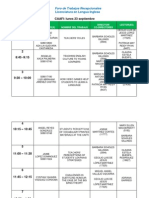

- Foro de ER - Sept - FinalThisOneDocument5 pagesForo de ER - Sept - FinalThisOneAbraham CastroPas encore d'évaluation

- Module 1 Teaching PE Health in Elem. Updated 1Document10 pagesModule 1 Teaching PE Health in Elem. Updated 1ja ninPas encore d'évaluation

- Certified Assessor Training Program On Industry 4.0Document3 pagesCertified Assessor Training Program On Industry 4.0Himansu MohapatraPas encore d'évaluation

- High School Report CardDocument2 pagesHigh School Report Cardapi-517873514Pas encore d'évaluation

- Research 11 3Document3 pagesResearch 11 3Josefa GandaPas encore d'évaluation

- Cot 2021 Cleaning and SanitizingDocument3 pagesCot 2021 Cleaning and SanitizingChema Paciones100% (2)

- Population and SampleDocument35 pagesPopulation and SampleMargie FernandoPas encore d'évaluation

- Technology and Literature Teaching: Using Fanfiction To Teach Literary CanonDocument5 pagesTechnology and Literature Teaching: Using Fanfiction To Teach Literary Canonnita_novianti_2Pas encore d'évaluation

- Your Best Chance For: International OffersDocument9 pagesYour Best Chance For: International Offersumesh kumarPas encore d'évaluation

- 8 In-Depth Quantitative Analysis QuestionsDocument2 pages8 In-Depth Quantitative Analysis QuestionsDeepak AhujaPas encore d'évaluation

- Ecpe TestDocument20 pagesEcpe Test09092004100% (1)

- Teenage SmokingDocument1 pageTeenage SmokingdevrimPas encore d'évaluation

- (M2-MAIN) The Self From Various PerspectivesDocument120 pages(M2-MAIN) The Self From Various PerspectivesAngelo Payod100% (1)

- Linux AdministrationDocument361 pagesLinux AdministrationmohdkmnPas encore d'évaluation

- Ramakrishna Mission Vidyalaya Newsletter - July To December - 2007Document20 pagesRamakrishna Mission Vidyalaya Newsletter - July To December - 2007Ramakrishna Mission VidyalayaPas encore d'évaluation

- Assignment - Quantities and Chemical ReactionsDocument3 pagesAssignment - Quantities and Chemical Reactionsharisiqbal111Pas encore d'évaluation

- Community Development: A Critical Approach (Second Edition) : Book ReviewDocument3 pagesCommunity Development: A Critical Approach (Second Edition) : Book ReviewMiko FernandezPas encore d'évaluation

- Community Service Reflection PaperDocument2 pagesCommunity Service Reflection Paperapi-525941594Pas encore d'évaluation

- GRAMMaR LOGDocument6 pagesGRAMMaR LOGLedi Wakha Wakha0% (1)

- Ict Management 4221Document52 pagesIct Management 4221Simeony SimePas encore d'évaluation

- Structure of Academic TextsDocument22 pagesStructure of Academic TextsBehappy 89Pas encore d'évaluation

- Human Resources Officer CVDocument2 pagesHuman Resources Officer CVsreeharivzm_74762363Pas encore d'évaluation

- Coaching Islamic Culture 2017chapter1Document8 pagesCoaching Islamic Culture 2017chapter1FilipPas encore d'évaluation

- Perdev 2qDocument1 pagePerdev 2qGrace Mary Tedlos BoocPas encore d'évaluation

- Ultimate Customer ServiceDocument10 pagesUltimate Customer ServicesifPas encore d'évaluation

- Empowerment Module1Document15 pagesEmpowerment Module1Glenda AstodilloPas encore d'évaluation

- Portfolio Division ListDocument12 pagesPortfolio Division ListRosman DrahmanPas encore d'évaluation

- BSBAUD501 Initiate A Quality Audit: Release: 1Document5 pagesBSBAUD501 Initiate A Quality Audit: Release: 1Dwi Nur SafitriPas encore d'évaluation

- Intermittent FastingDocument5 pagesIntermittent FastingIrfan KaSSimPas encore d'évaluation