Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Appendicitis

Transféré par

Febriyana SalehCopyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Appendicitis

Transféré par

Febriyana SalehDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Appendicitis: Surgical Perspective

Author: Mark V Mazziotti, MD, Assistant Professor of Pediatric Surgery, Department of Surgery, Baylor College of Medicine, Texas Children's Hospital Coauthor(s): Robert K Minkes, MD, PhD, Professor of Surgery, University of Texas Southwestern; Chief of Surgical Services, Children's Medical Center of Dallas-Legacy Contributor Information and Disclosures Updated: Nov 12, 2008

Print This Email This

Overview Workup Treatment Follow-up Multimedia References Keywords

Information from Industry

Learn more about a contraceptive that offers a variety of benefits for a variety of patients Review information regarding the efficacy and convenience of the nonhormonal IUC. PARA92694AF/100622 Click here

Introduction

Appendicitis is one of the most common surgical conditions in the pediatric patient. Characteristics of appendicitis unique to infants, children, and adolescents are presented in this article. For excellent patient education resources, visit eMedicine's Esophagus, Stomach, and Intestine Center. Also, see eMedicine's patient education articles, Appendicitis and Abdominal Pain in Children.

History of the Procedure

Many early reports described inflammation in and around the appendix, but, in 1886, Reginald Fitz first provided an accurate description of the disease process. He clearly described the clinical history, physical findings, and pathology and was also the first to advocate appendectomy as the cure.

Although Thomas Morton is credited with the first successful appendectomy in the United States in 1887, one of the first surgeons to correctly diagnose acute appendicitis, perform an appendectomy, have the patient recover, and report his experience was Senn in 1889. This was also the year that McBurney described the clinical findings of acute appendicitis, including the point of maximal tenderness, which bears his name.

Problem

Appendicitis may be a significant source of morbidity.

Frequency

Individuals have approximately a 7% risk of developing appendicitis during their lifetime. Appendicitis is much more common in developed countries. Although the reason for this discrepancy is unknown, potential risk factors include a diet low in fiber and high in sugar, family history, and infection. The peak incidence of appendicitis is in children aged 10-12 years; thereafter, the incidence continues to decline, although appendicitis occurs in adulthood and into old age. The lowest incidence of appendicitis is in infancy.

Etiology

See Pathophysiology.

Pathophysiology

Appendicitis is most often due to luminal obstruction followed by presumed bacterial invasion. In children, obstruction is usually due to lymphoid hyperplasia of the submucosal follicles. The cause of this hyperplasia is controversial, but dehydration and a viral infection have been proposed. Another common cause of obstruction of the appendix is a fecalith. Other rare causes include foreign bodies, parasitic infections, and inflammatory strictures. Luminal obstruction and mucus production result in increased intraluminal pressure. Bacteria trapped within the appendiceal lumen begin to multiply, and the appendix becomes distended. Venous congestion and edema follow next, and, by 12 hours after onset, the inflammatory process may become transmural. Peritoneal irritation then develops. If the obstruction is left untreated, arterial blood flow to the appendix is compromised, and this leads to tissue ischemia. Full thickness necrosis of the appendiceal wall leads to perforation with the release of fecal and suppurative contents into the peritoneal cavity. Depending on the duration of the disease process, a localized walled-off abscess occurs, or, if the pathologic process has rapidly advanced, the perforation is free in the peritoneal cavity and generalized peritonitis occurs.

Presentation

Acute appendicitis

A history of periumbilical pain followed by anorexia or nausea is typical, followed by the development of localized right lower quadrant pain. Unfortunately, fewer than half of the children present with this classic combination of signs and symptoms. The length of the illness is usually less than 24-36 hours. All patients with appendicitis have abdominal pain and many have anorexia; absence of both of these findings should place the diagnosis of appendicitis in question. The child who states that riding in a vehicle was painful when the vehicle hit the bumps in the road on the way to the hospital may have peritoneal irritation. Atypical pain is common and occurs in 40-45% of patients. This includes children who initially have localized pain and those with no visceral symptoms. Physical examination helps to distinguish appendicitis from other abdominal diseases. Examination of the child requires skill, patience, and warm hands. Initial and continued observation of the child is of critical importance. An ill-appearing quiet child who is lying very still in bed, perhaps with his or her legs flexed, is much more concerning than a child who is laughing, playing, and walking around the room. The examination should be thorough and start with areas other than the abdomen. Because lower lobe pneumonias can cause abdominal findings, a history of such should be elicited and a thorough chest examination performed. Begin examination of the abdomen by asking the child to point with one finger to the site of maximal pain. Palpate the abdomen at a site distant to this, with the most tender area examined last. A particularly anxious child may be palpated with a stethoscope. Distracting questions concerning school and family members may be helpful to relieve anxiety during the examination. Observing the child's facial expressions during this questioning and palpating is critical. During the abdominal examination, try to avoid eliciting rebound tenderness. This is a painful practice and certainly destroys any trust that has been garnered during the examination. Other methods can be used to establish that the patient has peritoneal irritation. Asking the patient to jump up and down or to bounce his or her pelvis off the bed while in the supine position may elicit pain in the presence of peritoneal irritation. Alternatively, other acceptable maneuvers are tapping the patient's soles and shaking the stretcher. The digital rectal examination can be helpful in establishing the correct diagnosis, especially in sexually active teenage females. The child should be told that the examination is uncomfortable but should not cause sharp pain. The rectal examination is particularly important in the child with a pelvic appendix in whom the findings on the abdominal examination for appendicitis may be equivocal and indicative of peritoneal irritation. During the examination, one may elicit pain during palpation of the right side of the pelvis or one may feel a pelvic mass, which is more important when perforated appendicitis is suspected. Perforated appendicitis A thorough history and physical examination is again paramount for a correct diagnosis. Certain features of a child's presentation may suggest a perforated appendix. A child younger than 6

years with symptoms for more than 48 hours is much more likely to have a perforated appendix. The child may have generalized abdominal pain and may have a temperature higher than 38C. Examination of the abdomen may reveal generalized peritonitis or a tender right lower quadrant mass. Younger children are much more likely to present with diffuse abdominal pain and peritonitis, perhaps because their omentum is not well developed and cannot contain the perforation.

Indications

Appendectomy is indicated once the diagnosis of appendicitis or perforated appendicitis has been made. An exception would be a well-localized appendiceal perforation in a child who is clinically well. This presentation allows initial nonoperative treatment with definitive treatment months later with an interval appendectomy (see Future and Controversies).

Relevant Anatomy

The vermiform appendix is located in the right lower quadrant, arises from the cecum, and is generally 5-10 cm in length. The appendix is lined by typical colonic epithelium. The submucosa contains lymphoid follicles, which are very few at birth. This number gradually increases to a peak of about 200 follicles in persons aged 10-20 years; whereas, in persons older than 30 years, less than one-half that number is present, and the number continues to decrease throughout adulthood. The relation of the base of the appendix to the cecum is constant, but the tip may be found in various locations. Note that the anatomic position of the appendix determines the symptoms and the site of tenderness when the appendix becomes inflamed.

Contraindications

Almost no contraindications exist to the surgical treatment of appendicitis. However, note that certain patients with unrecognized perforated appendicitis may present in a state florid septic shock. In these patients (and even in those not so ill) one must ensure that the patient is adequately fluid resuscitated and is administered appropriate broad-spectrum antibiotics prior to proceeding to the operating room.

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- Pediatric Appendicitis Clinical Presentation - History, Physical ExaminationDocument5 pagesPediatric Appendicitis Clinical Presentation - History, Physical ExaminationBayu Surya DanaPas encore d'évaluation

- Appendicitis: Differential Diagnoses & Workup Treatment & Medication Follow-UpDocument12 pagesAppendicitis: Differential Diagnoses & Workup Treatment & Medication Follow-UpnetonetinPas encore d'évaluation

- Acute Appendicitis PaedsDocument5 pagesAcute Appendicitis PaedsemmaazizPas encore d'évaluation

- Does This Child Have AppendicitisDocument6 pagesDoes This Child Have Appendicitispoochini08Pas encore d'évaluation

- Intussusception - A Case ReportDocument3 pagesIntussusception - A Case ReportAgustinus HuangPas encore d'évaluation

- Appendicitis in Children - Children's Health Issues - MSD Manual Consumer VersionDocument4 pagesAppendicitis in Children - Children's Health Issues - MSD Manual Consumer Version2110053Pas encore d'évaluation

- 3 Common Pediatric Surgery ContinuedDocument5 pages3 Common Pediatric Surgery ContinuedMohamed Al-zichrawyPas encore d'évaluation

- Acute Appendicitis in Children: How Is It Different Than in Adults?Document6 pagesAcute Appendicitis in Children: How Is It Different Than in Adults?LidiaPas encore d'évaluation

- 18-Month-Old Boy With Abdominal Pain and Rectal Bleeding BackgroundDocument5 pages18-Month-Old Boy With Abdominal Pain and Rectal Bleeding Backgroundcamille nina jane navarroPas encore d'évaluation

- A Case Study On Acute AppendicitisDocument56 pagesA Case Study On Acute AppendicitisIvy Mae Evangelio Vios92% (13)

- Chapter X.4. Intussusception: Case Based Pediatrics For Medical Students and ResidentsDocument5 pagesChapter X.4. Intussusception: Case Based Pediatrics For Medical Students and ResidentsNawaf Rahi AlshammariPas encore d'évaluation

- AppendicitisDocument2 pagesAppendicitismaithamPas encore d'évaluation

- Acute AppendicitisDocument9 pagesAcute AppendicitisSyarafina AzmanPas encore d'évaluation

- Acute Appendicitis in Children Clinical Manifestations and Diagnosis - 2019 - UptodateDocument23 pagesAcute Appendicitis in Children Clinical Manifestations and Diagnosis - 2019 - Uptodatewinnie MontalvoPas encore d'évaluation

- AppendicitisDocument3 pagesAppendicitisJoseph Anthony GarciaPas encore d'évaluation

- Acute Abdominal Pain InInfants and ChildrenDocument14 pagesAcute Abdominal Pain InInfants and Childrenemergency.fumcPas encore d'évaluation

- Case Study of Ruptured Appendicitis With Localize Peritonitis (Final)Document76 pagesCase Study of Ruptured Appendicitis With Localize Peritonitis (Final)DRJC82% (22)

- Eduard Montano Case 5Document4 pagesEduard Montano Case 5Eduard GarchitorenaPas encore d'évaluation

- Ashcrafts Pediatric Surgery 6th EdDocument8 pagesAshcrafts Pediatric Surgery 6th Edcarlos olartePas encore d'évaluation

- Pediatric Clinics of North America IIDocument54 pagesPediatric Clinics of North America IIkarenPas encore d'évaluation

- Pyloric Stenosis WDocument11 pagesPyloric Stenosis WKlaue Neiv CallaPas encore d'évaluation

- Apendicitis Colitis y DiverticulitisDocument22 pagesApendicitis Colitis y DiverticulitisJulieth Cardozo PinzonPas encore d'évaluation

- Acute AppendicitisDocument5 pagesAcute AppendicitisPrasetya Ismail PermadiPas encore d'évaluation

- 6INVAGINASIDocument18 pages6INVAGINASIhazelelPas encore d'évaluation

- IntussusceptionDocument4 pagesIntussusceptionlovethestarPas encore d'évaluation

- Intussuseption and Hirschprung's DiseaseDocument5 pagesIntussuseption and Hirschprung's DiseaseAris Magallanes100% (2)

- Surgery - Pediatric GIT, Abdominal Wall, Neoplasms - 2014ADocument14 pagesSurgery - Pediatric GIT, Abdominal Wall, Neoplasms - 2014ATwinkle SalongaPas encore d'évaluation

- Acute AppendicitisDocument30 pagesAcute AppendicitisJohn RyanPas encore d'évaluation

- Gastroschisis - ClinicalKeyDocument33 pagesGastroschisis - ClinicalKeyjpma2197Pas encore d'évaluation

- Appendicitis + AppendicectomyDocument6 pagesAppendicitis + AppendicectomyClara Dian Pistasari PutriPas encore d'évaluation

- Case Presentation On AppendecitisDocument68 pagesCase Presentation On AppendecitisJah GatanPas encore d'évaluation

- AppendicitisDocument14 pagesAppendicitispreethijojo2003558288% (8)

- Apendicitis Diverticulitis y Colitis 2011Document22 pagesApendicitis Diverticulitis y Colitis 2011Jose Arturi Ramirez OsorioPas encore d'évaluation

- Oesophageal Atresia by GabriellaDocument7 pagesOesophageal Atresia by GabriellaGabriellePas encore d'évaluation

- Pinky Assessment Part2Document15 pagesPinky Assessment Part2Ian Mizzel A. DulfinaPas encore d'évaluation

- IntroductionDocument5 pagesIntroductionPrecious UncianoPas encore d'évaluation

- Ped Surg Mcqs 2Document24 pagesPed Surg Mcqs 2abdurrahman100% (1)

- Intus Su CeptionDocument26 pagesIntus Su Ceptiongallegomarjorie16Pas encore d'évaluation

- Acute Abdominal Pain in ChildrenDocument6 pagesAcute Abdominal Pain in ChildrenDeving Arias RamosPas encore d'évaluation

- Case StudyDocument57 pagesCase StudyEdmarkmoises ValdezPas encore d'évaluation

- 299-Article Text-633-1-10-20200912Document5 pages299-Article Text-633-1-10-20200912daily of sinta fuPas encore d'évaluation

- Gastroenterology For General SurgeonsD'EverandGastroenterology For General SurgeonsMatthias W. WichmannPas encore d'évaluation

- Clinical Evaluation of Acute Appendicitis 2014Document8 pagesClinical Evaluation of Acute Appendicitis 2014maithamPas encore d'évaluation

- Grand Case Pres - Transverse Vaginal Septum..Document32 pagesGrand Case Pres - Transverse Vaginal Septum..Gio LlanosPas encore d'évaluation

- GastroschisisDocument19 pagesGastroschisiskunaidongPas encore d'évaluation

- Adult Bowel Intussusception: Presentation, Location, Etiology, Diagnosis and TreatmentDocument4 pagesAdult Bowel Intussusception: Presentation, Location, Etiology, Diagnosis and TreatmentRizki Ismi Arsyad IIPas encore d'évaluation

- Tarlac State UniversityDocument11 pagesTarlac State UniversityJenica DancilPas encore d'évaluation

- Appendicitis CaseDocument8 pagesAppendicitis CaseStarr NewmanPas encore d'évaluation

- Medical Facts and Mcq's Pediatric Surgery MCQDocument34 pagesMedical Facts and Mcq's Pediatric Surgery MCQMohammed Kassim Abdul Jabbar100% (3)

- Current Approach To The Diagnosis and Emergency Department Management of Appendicitis in ChildrenDocument6 pagesCurrent Approach To The Diagnosis and Emergency Department Management of Appendicitis in ChildrenmaithamPas encore d'évaluation

- Incarceratedpediatric Hernias: Sophia A. Abdulhai,, Ian C. Glenn,, Todd A. PonskyDocument17 pagesIncarceratedpediatric Hernias: Sophia A. Abdulhai,, Ian C. Glenn,, Todd A. PonskyPhytoplankton DiatomsPas encore d'évaluation

- Chandrasekaran2014 PDFDocument5 pagesChandrasekaran2014 PDFMirza RisqaPas encore d'évaluation

- Melissa Kennedy, Chris A. LiacourasDocument3 pagesMelissa Kennedy, Chris A. LiacourasChristian LoyolaPas encore d'évaluation

- 03 (A) Health Bulletin APPENDICITISDocument1 page03 (A) Health Bulletin APPENDICITIScristianvoinea13Pas encore d'évaluation

- Intussusception - Practice Essentials, Background, Etiology and PathophysiologyDocument10 pagesIntussusception - Practice Essentials, Background, Etiology and PathophysiologyfkPas encore d'évaluation

- Usg in ChildrenDocument19 pagesUsg in Childrenmia rachmiPas encore d'évaluation

- Esophageal AtresiaDocument18 pagesEsophageal AtresiaNeha RathorePas encore d'évaluation

- Appendicitis: Made By: Madhurpreet KaurDocument46 pagesAppendicitis: Made By: Madhurpreet KaurRAJAT DUGGALPas encore d'évaluation

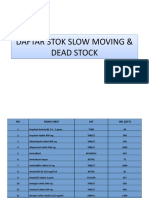

- Daftar Stok Slow Moving & Dead Stock Daftar Stok Slow Moving & Dead StockDocument11 pagesDaftar Stok Slow Moving & Dead Stock Daftar Stok Slow Moving & Dead StockFebriyana SalehPas encore d'évaluation

- TresmmDocument1 pageTresmmFebriyana SalehPas encore d'évaluation

- Pemberitahuan Latsar PDFDocument4 pagesPemberitahuan Latsar PDFFebriyana SalehPas encore d'évaluation

- Susunan Pengurus Idi Cabang Kota Tidore Kepulauan PERIODE 2018-2021Document2 pagesSusunan Pengurus Idi Cabang Kota Tidore Kepulauan PERIODE 2018-2021Febriyana SalehPas encore d'évaluation

- Stok Obat Slow MovingDocument25 pagesStok Obat Slow MovingFebriyana SalehPas encore d'évaluation

- Morning Report 13 SEP - 26 SEPT 2018Document19 pagesMorning Report 13 SEP - 26 SEPT 2018Febriyana SalehPas encore d'évaluation

- Laporan Respon Time Okt 2018Document42 pagesLaporan Respon Time Okt 2018Febriyana SalehPas encore d'évaluation

- Search Results: Cited by 3 Related ArticlesDocument2 pagesSearch Results: Cited by 3 Related ArticlesFebriyana SalehPas encore d'évaluation

- Super Junior LyricDocument5 pagesSuper Junior LyricFebriyana SalehPas encore d'évaluation

- Emw 2007 FP 02093Document390 pagesEmw 2007 FP 02093boj87Pas encore d'évaluation

- Technical Information: Range-Free Controller FA-M3 System Upgrade GuideDocument33 pagesTechnical Information: Range-Free Controller FA-M3 System Upgrade GuideAddaPas encore d'évaluation

- Effects of Climate ChangeDocument3 pagesEffects of Climate Changejiofjij100% (1)

- Gamak MotorDocument34 pagesGamak MotorCengiz Sezer100% (1)

- Extract From The Painted Door' by Sinclair RossDocument2 pagesExtract From The Painted Door' by Sinclair RosssajifisaPas encore d'évaluation

- Training Report On Self Contained Breathing ApparatusDocument4 pagesTraining Report On Self Contained Breathing ApparatusHiren MahetaPas encore d'évaluation

- Tree Growth CharacteristicsDocument9 pagesTree Growth CharacteristicsMunganPas encore d'évaluation

- Worlds Apart: A Story of Three Possible Warmer WorldsDocument1 pageWorlds Apart: A Story of Three Possible Warmer WorldsJuan Jose SossaPas encore d'évaluation

- Guia de CondensadoresDocument193 pagesGuia de CondensadoresPaola Segura CorreaPas encore d'évaluation

- Harmonics PatternsDocument4 pagesHarmonics PatternsIzzadAfif1990Pas encore d'évaluation

- Week 1 - NATURE AND SCOPE OF ETHICSDocument12 pagesWeek 1 - NATURE AND SCOPE OF ETHICSRegielyn CapitaniaPas encore d'évaluation

- Learning Activity Sheets Introduction To World Religions and Belief SystemDocument56 pagesLearning Activity Sheets Introduction To World Religions and Belief SystemAngelica Caranzo LatosaPas encore d'évaluation

- Fully Automatic Coffee Machine - Slimissimo - IB - SCOTT UK - 2019Document20 pagesFully Automatic Coffee Machine - Slimissimo - IB - SCOTT UK - 2019lazareviciPas encore d'évaluation

- Board Replacement CasesDocument41 pagesBoard Replacement CasesNadeeshPas encore d'évaluation

- 41z S4hana2021 Set-Up en XXDocument46 pages41z S4hana2021 Set-Up en XXHussain MulthazimPas encore d'évaluation

- Biophoton RevolutionDocument3 pagesBiophoton RevolutionVyavasayaha Anita BusicPas encore d'évaluation

- NCP Orif Right Femur Post OpDocument2 pagesNCP Orif Right Femur Post OpCen Janber CabrillosPas encore d'évaluation

- H107en 201906 r4 Elcor Elcorplus 20200903 Red1Document228 pagesH107en 201906 r4 Elcor Elcorplus 20200903 Red1mokbelPas encore d'évaluation

- Hydrodynamic Calculation Butterfly Valve (Double Disc)Document31 pagesHydrodynamic Calculation Butterfly Valve (Double Disc)met-calcPas encore d'évaluation

- Lesson 1 Chapter 9 ErosiondepositionDocument1 pageLesson 1 Chapter 9 Erosiondepositionapi-249320969Pas encore d'évaluation

- Niir Integrated Organic Farming Handbook PDFDocument13 pagesNiir Integrated Organic Farming Handbook PDFNataliePas encore d'évaluation

- Lab Report Marketing Mansi 4Document39 pagesLab Report Marketing Mansi 4Mansi SharmaPas encore d'évaluation

- Irina Maleeva - Ariel Snowflake x6 - ENG - FreeDocument4 pagesIrina Maleeva - Ariel Snowflake x6 - ENG - FreeMarinaKorzinaPas encore d'évaluation

- DudjDocument4 pagesDudjsyaiful rinantoPas encore d'évaluation

- Course Registration SlipDocument2 pagesCourse Registration SlipMics EntertainmentPas encore d'évaluation

- SSDsDocument3 pagesSSDsDiki Tri IndartaPas encore d'évaluation

- Sony Cdm82a 82b Cmt-hpx11d Hcd-hpx11d Mechanical OperationDocument12 pagesSony Cdm82a 82b Cmt-hpx11d Hcd-hpx11d Mechanical OperationDanPas encore d'évaluation

- AssessmentDocument9 pagesAssessmentJuan Miguel Sapad AlpañoPas encore d'évaluation

- The Acceptability of Rubber Tree Sap (A As An Alternative Roof SealantDocument7 pagesThe Acceptability of Rubber Tree Sap (A As An Alternative Roof SealantHannilyn Caldeo100% (2)

- Cost Analysis - Giberson Art GlassDocument3 pagesCost Analysis - Giberson Art GlassSessy Saly50% (2)