Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Connelly - Fatal Misconception - Diplomatic History Book Review (2009)

Transféré par

SiesmicCopyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Connelly - Fatal Misconception - Diplomatic History Book Review (2009)

Transféré par

SiesmicDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

elizabeth cobbs hoffman

BOOK REVIEW Social Engineers Run Amok: The International Politics of Population Control

Matthew Connelly. Fatal Misconception: The Struggle to Control World Population. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press, 2008. xiv + 521 pp. Illustrations, notes, index. $35.00.

It is a truism that people are unpredictable. Even the most oppressed exert agency, as historians have emphasized in recent decades. This observation also goes to the heart of democracy. Allowing people to make their own decisions means that outcomes are not predetermined. Matthew Connellys brilliant new book explores choice at its most primordial and underscores the old feminist proverb that the personal is political. He shows that in the name of giving people the power to limit their fertility, transnational agencies climbed into bed with government, as it were, to control individual reproductive behavior. Reformers gave women more say over their lives, but subverted liberty at the same time, making states immeasurably more intrusive. In many ways, this is an old story with stock characters. There are the usual ham-handed government ofcials who implement draconian measures in the name of social engineering. (Think of Peter the Great personally shaving the long beards off Old Believers.) They are egged on by upper-class reformers who think they know best how the poor should live and who blithely impose limits on others they would never tolerate for themselves. But what makes this book deeply humane and an exemplar of intellectual integrity is its recognition that bureaucrats are also unpredictable and that even social engineers want to learn from their mistakes. Connelly is as unwilling to stereotype elites as he is to create a caricature of the poor. They are all aggravatingly human. Fatal Misconception uses archives in seven countries to show how collaboration in the eld of population control brought private agencies together with governments in unprecedented ways. Groups like Planned Parenthood exhorted states worldwide to make birth control available to all potential parents. This harmonized with the dreams of eugenicists, who wanted governments to limit reproduction of the unt and thereby improve the human stock. This dovetailed further with the personal interests of inquisitive scientists, UN

Diplomatic History, Vol. 33, No. 2 (April 2009). 2009 The Society for Historians of American Foreign Relations (SHAFR). Published by Wiley Periodicals, Inc., 350 Main Street, Malden, MA, 02148, USA and 9600 Garsington Road, Oxford OX4 2DQ, UK.

371

372 : d i p l o m a t i c h i s t o r y

bureaucrats, foundation executives, and charismatic activists who took the world as their oyster. Connelly admits that the international politics of population control did not t into Cold War categories (p. 152), but he convincingly demonstrates that people in the twentieth century began to reimagine international relations in terms of the relations between different populations (p. 75). The story begins in the late nineteenth century with Annie Besant in England and moves into the twentieth with Margaret Sanger in the United States. Both saw uncontrolled reproduction as the greatest tyranny affecting the lives of women. Sanger, particularly, recognized the cost. The daughter of Irish Catholic parents, she was the sixth of eleven children her mother bore (from eighteen pregnancies) before dying of cervical cancer and tuberculosis. Sanger became the most important international activist for birth control, seeing it as a universal human value that linked women worldwide (p. 51). Travels to India, Japan, and China convinced her that reformers should use state mechanisms to advance the cause, but that the cause itself transcended borders. Sangers efforts complemented those of other movements less benevolent in their goals. Nativists denounced the Yellow Peril and advocated exclusionary immigration laws. If the Chinese and Japanese (and Jews, Catholics, and other unt immigrants) practiced birth control instead of breeding like rodents, so nativists said, fewer of them would crowd American shores. Eugenicist Madison Grant, author of The Passing of the Great Race in 1916, advocated outright sterilization as the practical, merciful, and inevitable solution for such worthless race types (p. 44). At the same time, he and others of a similar mind feared the indiscriminate promotion of birth control since it might inadvertently liberate the educated and t to breed less frequently (p. 53). What would happen if genteel women took it into their heads to limit fertility? The moral dilemma for Sanger and her followers was how to make use of the political and nancial support eugenicists provided, without being tainted by their parochial and oppressive motives. At a 1925 international conference on population control, Sanger quashed a resolution to encourage reproduction by parents whose progeny had promise, arguing that the the progeny of all parents will give unsuspected promise if planned rationally (p. 65). But she never entirely eluded the taint of association with unsavory types who itched to treat whole populations like laboratory subjects. Eugenicists were nally discredited by the most evil mad scientist of them all, Adolf Hitler, notorious for his efforts to eradicate Jews while enticing blond Aryan women to have litters like rabbits. Meanwhile, population growth soared. Connelly notes the remarkable fact that during World War II, which killed roughly 70 million, the planet grew by 15 million inhabitants annually because of steep declines in infant mortality achieved during the 1930s and 1940s. In the twentieth century, world population doubled and then doubled again.

Social Engineering Run Amok : 373

The birth control movement expanded, too. After World War II, the dialogue went beyond feminists and eugenicists when it became apparent that the planet might surpass its carrying capacity. Connelly calls these the Malthusians: scientists who warned of famine and ecological degradation if the exponential growth rate did not abate. These worriers had much in common with yet another postwar constituency: development economists and postcolonial governments eager to boost Third World living standards. They pointed to the dangerous disparity between rates of economic growth and population growth. If economies grew at 2 percent per annum and populations grew at 3 percent, countries would become poorer and poorer. Connellys book is at its most original in its exploration of this phase. He delves deeply into archives that reveal the intense pressure that institutions like the World Bank, and donor countries like Sweden and the United States, placed on developing countries to control population growth. Loans and other forms of aid were sometimes tied explicitly to progress. Foreign experts often looked the other way when local governments twisted arms (and cut fallopian tubes) to make it happen. At the same time, Connelly explodes the notion that there was any conspiracy by lighter-skinned people to diminish the number of darker-skinned ones, as propagandists have alleged. Indeed, he shows that the keenest anxiety about accelerating birth rates was internal. The Chinese and Indian governments, for example, both used incentives to induce better reproductive choices, and these included nearly every form of welfare benet the state could offer, from clean water and food rations to pay raises and rickshaw licenses. And if this seems beyond the pale, there was worse: forcible sterilizations and abortions. At the height, in the 1970s and 1980s, the Indian government performed eight million sterilizations in one year, and the Chinese performed twenty million. Connelly reports, but does not comment on, an interesting difference in the choices they made. The Indians sterilized mostly males (75 percent of the total), while the Chinese sterilized mostly females (80 percent of the total). In India these operations were often performed en masse, with few concessions to hygiene and none to privacy. Still, the population bomb was defused. The author notes one might be tempted to think the result was worth the price, except for the fact that the sacrices may have been unnecessary (p. 371). Sanger intuitively knew what the experts conceded only recently. Given choices, most people will make sensible ones. Over the past century, the most reliable predictor of a decline in fertility is a rise in female literacy. Women who can read almost invariably have fewer children than those who cannot. It is therefore the emancipation of women, not population control, that has remade humanity (p. 375). Here and elsewhere, the author emphasizes the encroachments upon liberty made by experts. They could have adopted less coercive measures, but they chose not to. The fertility rate declined just as sharply in countries where almost

374 : d i p l o m a t i c h i s t o r y

no effort was made (but women became literate) as in those countries where every effort was made. Ultimately, Connellys heroes are the common people. In India in 1977, they routed Prime Minister Indira Gandhi from ofce and her party from parliament. Something even more powerful, even more implacable, had nally defeated the ideology of population control: People voting one by one (p. 326). Connellys conclusion lifts the discussion to the highest realms of international relations. He asserts that the most egregious errors of international and nongovernmental organizations should remind us that, for all their faults, nation-states may provide the best guarantee of personal liberty. In recent years, the institution of sovereignty has seemed increasingly shaky, he notes. Yet outsiders who are unaccountable to any electorate may create an Empire Lite if not restrained (p. 379). Connelly gives us a beautifully written, fast-paced book. The author admits to the passion of a convert, and there are times when the grudge becomes personal. He thanks his Catholic parents for having so many children, including him, the eighth. One wishes he had drawn back a little. By the end, the prose reads more like a manifesto than an investigation. This blurs the commonly underrated, but nonetheless important, distinction between a scholars job and a citizens responsibility. Yet this is not a fatal misconception. Connelly has written an important, caring book. Readers may wish to thank his parents, too.

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- 2016 - 2017-OPTDocument2 pages2016 - 2017-OPTSiesmicPas encore d'évaluation

- Pakistan Civil Aviation Authority: Major Traffic Flows by Airlines During The YearDocument2 pagesPakistan Civil Aviation Authority: Major Traffic Flows by Airlines During The YearMuhammad IlyasPas encore d'évaluation

- Pakistan Civil Aviation Authority: Major Traffic Flows by Airlines During The YearDocument2 pagesPakistan Civil Aviation Authority: Major Traffic Flows by Airlines During The YearMuhammad IlyasPas encore d'évaluation

- EU Fund Opportunities for Higher EducationDocument30 pagesEU Fund Opportunities for Higher EducationSiesmicPas encore d'évaluation

- The Scientific and Technological Research Council of TurkeyDocument26 pagesThe Scientific and Technological Research Council of TurkeySiesmicPas encore d'évaluation

- Univ of Sheffield - Lecturer in International Relations (2 Posts)Document2 pagesUniv of Sheffield - Lecturer in International Relations (2 Posts)SiesmicPas encore d'évaluation

- Hollins University 2019-2020 Environmental Studies CatalogDocument7 pagesHollins University 2019-2020 Environmental Studies CatalogSiesmicPas encore d'évaluation

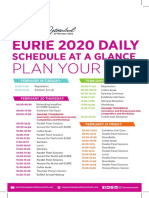

- Eurie Fuar Katalog 2020 PDFDocument52 pagesEurie Fuar Katalog 2020 PDFSiesmicPas encore d'évaluation

- Enabling Entrepreneurship Despite Global CrisisDocument41 pagesEnabling Entrepreneurship Despite Global CrisisSiesmicPas encore d'évaluation

- Global Engagement Plan Edinburgh 2019Document12 pagesGlobal Engagement Plan Edinburgh 2019SiesmicPas encore d'évaluation

- Schedule-2020 Oct19Document1 pageSchedule-2020 Oct19SiesmicPas encore d'évaluation

- University of Tabriz: SINCE 1947Document20 pagesUniversity of Tabriz: SINCE 1947SiesmicPas encore d'évaluation

- Community Outreach Program 2020 BrochureDocument3 pagesCommunity Outreach Program 2020 BrochureSiesmicPas encore d'évaluation

- Internationalization of Higher Education in Iran (With Special Approach To Amirkabir University of Technology) Dr. Mahnaz EskandariDocument23 pagesInternationalization of Higher Education in Iran (With Special Approach To Amirkabir University of Technology) Dr. Mahnaz EskandariSiesmicPas encore d'évaluation

- Internationalization of Turkish Higher EducationDocument18 pagesInternationalization of Turkish Higher EducationSiesmicPas encore d'évaluation

- Global and textual webs in an age of transnational capitalismDocument27 pagesGlobal and textual webs in an age of transnational capitalismSiesmicPas encore d'évaluation

- Türkiye Scholarships: Vision For Turkey As A Global Hub For Higher EducationDocument23 pagesTürkiye Scholarships: Vision For Turkey As A Global Hub For Higher EducationSiesmicPas encore d'évaluation

- Lewis Cardenas Steven Chang Robert Coffey Nurten UralDocument21 pagesLewis Cardenas Steven Chang Robert Coffey Nurten UralSiesmicPas encore d'évaluation

- Bronislaw Szerszynski, End of The End of NatureDocument12 pagesBronislaw Szerszynski, End of The End of NatureJoshua BeneitePas encore d'évaluation

- Study Abroad Guide 2019 Web 19 2 19 131951324290339176Document23 pagesStudy Abroad Guide 2019 Web 19 2 19 131951324290339176SiesmicPas encore d'évaluation

- U or Regina 2019 International ViewbookDocument28 pagesU or Regina 2019 International ViewbookSiesmicPas encore d'évaluation

- Curriculum Internationalization at Iranian UniversityDocument11 pagesCurriculum Internationalization at Iranian UniversitySiesmicPas encore d'évaluation

- Revue de Droit International - History (1924)Document2 pagesRevue de Droit International - History (1924)SiesmicPas encore d'évaluation

- Funk - Mixed Messages About Public Trust in Science (Dec 2017)Document6 pagesFunk - Mixed Messages About Public Trust in Science (Dec 2017)SiesmicPas encore d'évaluation

- Tardieu - Truth About The Treaty (1921)Document313 pagesTardieu - Truth About The Treaty (1921)SiesmicPas encore d'évaluation

- Alantropa - Cabinet - Issue 10 (Spring 2003)Document4 pagesAlantropa - Cabinet - Issue 10 (Spring 2003)SiesmicPas encore d'évaluation

- Washing Machine InstructionsDocument12 pagesWashing Machine InstructionsSiesmicPas encore d'évaluation

- Review of Chen, Asia As MethodDocument3 pagesReview of Chen, Asia As MethodSiesmicPas encore d'évaluation

- Ascherson Liquidator (2010)Document10 pagesAscherson Liquidator (2010)SiesmicPas encore d'évaluation

- 05 Mintz - Sweetness and PowerDocument24 pages05 Mintz - Sweetness and PowerSiesmicPas encore d'évaluation

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5784)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (890)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (399)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (72)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (344)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)

- The Prostitute Poem Explores a Sex Worker's StrugglesDocument17 pagesThe Prostitute Poem Explores a Sex Worker's StrugglesGalrich Cid CondesaPas encore d'évaluation

- OTBA Class 9 Mathematics (English Version)Document11 pagesOTBA Class 9 Mathematics (English Version)Mota Chashma86% (7)

- DeputationDocument10 pagesDeputationRohish Mehta67% (3)

- Managing Curricular Change in Math and ScienceDocument14 pagesManaging Curricular Change in Math and ScienceMichelle Chan Mei GwenPas encore d'évaluation

- CH 1 HRM - Its Nature Scope Functions ObjectiesDocument7 pagesCH 1 HRM - Its Nature Scope Functions ObjectiesBhuwan GuptaPas encore d'évaluation

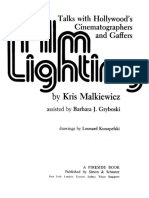

- Film Lighting Malkievicz v1 PDFDocument60 pagesFilm Lighting Malkievicz v1 PDFAlejandro JiménezPas encore d'évaluation

- Scientific MethodDocument11 pagesScientific MethodPatricia100% (2)

- Importance of Green Marketing and Its Potential: Zuzana Dvořáková Líšková, Eva Cudlínová, Petra Pártlová, Dvořák PetrDocument4 pagesImportance of Green Marketing and Its Potential: Zuzana Dvořáková Líšková, Eva Cudlínová, Petra Pártlová, Dvořák PetrMonicaPas encore d'évaluation

- Creativity in TranslationDocument35 pagesCreativity in TranslationRodica Curcudel50% (2)

- (John McRae) The Language of Poetry (Intertext) (BookFi) PDFDocument160 pages(John McRae) The Language of Poetry (Intertext) (BookFi) PDFRaduMonicaLianaPas encore d'évaluation

- The DreamsellerDocument4 pagesThe DreamsellerAnuska ThapaPas encore d'évaluation

- Music Video Hey BrotherDocument4 pagesMusic Video Hey BrotherAnonymous KC4YwhPas encore d'évaluation

- Change Management ModelDocument3 pagesChange Management ModelRedudantKangarooPas encore d'évaluation

- Tintern Abbey by William WordsworthDocument3 pagesTintern Abbey by William WordsworthZobia AsifPas encore d'évaluation

- Tpcastt Richard CoryDocument2 pagesTpcastt Richard Coryapi-530250725Pas encore d'évaluation

- For English 4 2n ParDocument2 pagesFor English 4 2n Parjuan josePas encore d'évaluation

- Make A Difference Annual Report 2014-15Document44 pagesMake A Difference Annual Report 2014-15Make A DifferencePas encore d'évaluation

- CLP Talk 04 - Repentance and Faith PDFDocument5 pagesCLP Talk 04 - Repentance and Faith PDFJason YosoresPas encore d'évaluation

- TAGG Nonmusoall-1Document710 pagesTAGG Nonmusoall-1blopasc100% (2)

- 3rd Yr VQR MaterialDocument115 pages3rd Yr VQR MaterialPavan srinivasPas encore d'évaluation

- June 1958 Advice For LivingDocument2 pagesJune 1958 Advice For Livinganon_888843514Pas encore d'évaluation

- Quantum Tunnelling: ReboundingDocument12 pagesQuantum Tunnelling: ReboundingEpic WinPas encore d'évaluation

- VU21444 - Identify Australian Leisure ActivitiesDocument9 pagesVU21444 - Identify Australian Leisure ActivitiesjikoljiPas encore d'évaluation

- MemoDocument6 pagesMemoapi-301852869Pas encore d'évaluation

- Qualities of A Sports WriterDocument2 pagesQualities of A Sports WriterMaria Bernadette Rubenecia100% (3)

- Eucharistic MiraclesDocument2 pagesEucharistic MiraclespeterlimttkPas encore d'évaluation

- Anjali Kakkar 9810118753 A-219 Saroop Nagar Delhi-42 Near PNB BankDocument2 pagesAnjali Kakkar 9810118753 A-219 Saroop Nagar Delhi-42 Near PNB BankMOHIT SHARMAPas encore d'évaluation

- Finaal PPT EfcomDocument17 pagesFinaal PPT EfcomRolyn BonghanoyPas encore d'évaluation

- Chi SquareDocument12 pagesChi SquareAlicia YeoPas encore d'évaluation

- Vedic Chart PDF - AspDocument18 pagesVedic Chart PDF - Aspbhavin.b.kothari2708Pas encore d'évaluation