Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Arthalankaras in The Bhattikavya

Transféré par

Priyanka MokkapatiTitre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Arthalankaras in The Bhattikavya

Transféré par

Priyanka MokkapatiDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

On Some "arthlakras" in the "Bhaikvya" X Author(s): C.

Hooykaas Reviewed work(s): Source: Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London, Vol. 20, No. 1/3, Studies in Honour of Sir Ralph Turner, Director of the School of Oriental and African Studies, 1937-57 (1957), pp. 351-363 Published by: Cambridge University Press on behalf of School of Oriental and African Studies Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/610388 . Accessed: 23/11/2011 11:23

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Cambridge University Press and School of Oriental and African Studies are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London.

http://www.jstor.org

ON SOME ARTHALANKAMASIN THE BHATTIKAVYA X

By C. HOOYKAAS mahakavya Ravanavadhaby Bhatti, known as the Bhattikavya,differs from the other mahakavyas by its 'flowers' embroidered on the underlying theme of the Rdim4yana: the main purpose of the poem is to illustrate examples from Sanskrit grammar,and halfway through it the poet/grammarian, now becoming a poet/alaikarika, devotes some sargas to a systematic disquisition on poetics: sabddlaikara (anuprasa and yamaka), arthalaitkira (circa 40 of them), and some gu.na and rasa (mddhuryaand bhavikatva). Bhatti's poem is purely traditional, not only in his choice of epic material and its length, but also in many other respects such as the division into 22 sargas, each one marked by a final stanza or some final stanzas written in another metre, and its having one sarga devoted to a display of a great variety of metres. There are, however, at least three points which deserve notice: (a) its beginning is not in strict accordance with the rules for a mahakavya as laid down in Dandin's KavySdarsa I. 14-22; (b) the poem only alludes to the trick of the illusory heads of Rama and Laksmana in xIv. 1, contrary to those rules; and (c) it deals rather summarily with the end, where the teacher in Bhatti was more interested in demonstrating the use of some additional future tenses than was the poet or the believer in achieving the completion of a work of art and a human drama. These facts are apparently counterbalanced by Bhatti's virtuosity shown for example in an uninterrupted display of 20 different yamakas which nevertheless does not cause serious damage to the epic story (x. 2-22), and in his construction of 53 uninterrupted stanzas of arthalanikaras in the same sarga. These have been presented roughly in the sequence in which they were found in Dandin's Kavyaidarsaand Bhamaha's Kavyalainkara; but what can we say about the exact meaning which Bhatti intended to convey in each particular stanza ? There is more reason than before to go into this subject, for Dr. C. Bulcke, S.J., has pointed out in his thesis Ramakatha (Allahabad, 1950) that the Bha.ttikvya is not only a remarkable piece of work like so many other Indian poems, but that it was the prototype of the Old-Javanese Ramiayana. This 'kakawin' (kavya) is the recognized ' adi-kakawin' of a whole series of works of similar character in the Javano-Balinese literature spread over a period of a thousand years and reaching up to the present time. In its wake we find many important poems such as Bhoma-kawya,Arjuna-Wiwaha,Smara-Dahana, Bhtrata-Yuddha, Krs.nyana, Sutasoma, to mention only a few of them. Consequently it appears important to know as much as possible about the OJR Kakawin and its prototype the Bhattikavya, and though Kane in his History of Sanskrit poetics of 1951 (p. 70) is still satisfied with the general

THE

352

C. IIOOYKAAS

and the technical terms applied position of opinion on Bhatti's arthalaikdaras, to them by the current commentaries, Raghavan in his book Studies on some Sastra of 1942 (good indexes) mistrusts the professional conceptsof the Alainkdra omniscience of Bhatti's commentators and exhorts to criticism. Though profoundly aware of the fact that my knowledge of Indology in general and of Indian poetics in particular is inadequate and that my remarks are only the questions arising in a student who is mainly concerned with the Javano-Balinese field, nevertheless I gratefully accept this opportunity of drawing the attention of my Indian colleagues to them. As several out of the 53 stanzas on arthdlainkdra will be dealt with and as in translation it I-v and are more or less accessible xvII-xxii only sargas seemed advisable to begin with offering the translation of the well-rounded passage BhK x. 23-75. I would not have succeeded in this without the help of my colleague C. A. Rylands, and the translation given here is his work.

BHATTI-KAVYA X. 23-75

(Hanumat, the monkey-messenger of Prince Rama, whose wife Princess Sita has been abducted by the raksasa-king Ravana of Lanka, after having met Sita and fulfilled his mission in Lafka, returns to Rama on Mt. Mahendra.) 23. As he (Hanfumat)went, he scattered the waters of the sea; they shook the trees standing on its shore, they (the trees) shed carpets of flowers pleasant to the touch, and amorous kinnaras rested on those flower-carpets. 24. The monkey, with speed arriving at the mountain adorned with groups of trees, showing by his smile his certainty of success, caused it (the mountain) to be adorned by joyful troops of monkeys. 25. Although Garuda, the Wind and the Sun are esteemed for their speed among swift movers, nevertheless they (the monkeys) regarded him (Hanimat) as superior (in speed) when he so soon returned successful. 26. Then that mountain of a monkey appeared with missile-snakes hiding in his wound-caves, with his broad expanse of chest like rough broad rockwalls, with mineral colours produced by his streaming blood. 27. With their waving tawny hair like golden creepers, and their bright rows of eyes like masses of gems, the monkeys shone like golden ridges of the mountain at Haniumat's coming. 28. The monkey-moon, delighting with his welcome sight the seas that were the [other] monkeys, spreading his beams in the form of ambrosial words, made them to have their waters, i.e. their eyes, full of joy. 29. Trampling on the shrubs of the Vindhya, drinking the clear torrentwater, the monkeys like elephants then shook the nectar-grove at the command of the delighted Angada. 30. Dispelling the darkness of despondency in the monkeys, awakening the lotus of good tidings by the rays of his welcome words, the monkey, like the

ON SOME ARTHALANKARAS

IN THE BHATTIKAVYA

353

sun, left the mountain (Mahendra) like [the sun leaving] the Eastern hill and rose into the sky, destroying the gloom of despair residing in the caverns of the king's heart. 31. Hanumat found Rama in the holy grove, wearing matted hair and goatskin and bark-dress, together with his younger brother (Laksmana) who resembled him in quietude and dress and religious meditation, like the Supreme Being (Vis.nu/Narayana) accompanied by Nara. 32. Holding in his joined hands the gem, from which faint rays came out through the interstices of his fingers, like the moon standing in thin tawny clouds, he saluted the king with bent knees and head. 33. Rama saw with [renewed] hope of life his wife's head-jewel, which had the value of a lovely and precious jewel, with a disc like that of the full moon. 34. He (Rama) saw the jewel as resembling himself, of diminished splendour, having come from the (asoka-)grove [or referring to himself: having gone to the forest (in exile)], dim with dust that had not been wiped off, separated from Sita, and possessing only its [intrinsic]value [or: with referenceto himself: possessing only his dignity/honour]. 35. 'Having by his ability accomplished his desired purpose, how can Hanumat fail to be a wish-granting jewel ? ', so thought King [Rama] with Laksmana then, and so did the leader of the monkey-army (Sugriva). 36. 'The enemy (Ravana), not realizing that all of you are like the wind of world-destruction, fool that he is to hold Sita, who is like a spark of fire, lies in Lanka like a lion in his forest-lair, (doomed) to die ', said Hanumat. 37. 'I have returned from seeing him (Ravana), who possessed of magic power stole Kubera's wealth and engaged in great strife with the gods, extremely full of the intoxication of power that scorns shame; (for) who in this world is not driven from the right path by power obtained ? (yamakasin 37). 38. 'He is powerful and a raksasa and a fool, no wonder he is insolent; but what reason have the ignoble to walk in the path of virtue ? 39. 'In his abode I saw Rama's wife, thin, sad and sorrowful. The gist of the business has now been related to you; what is the use of mentioning the rest of my wanton actions 2 40. ' Sta, pure and slender in her decline, would come to resemble the moon's crescent, if indeed no spot previously existing marred the crescent moon or should do so in the future. 41. ' You, 0 king ! must strive adequately to rescue your virtuous wife, who was seized by [Ravana] who acts without reflection, does not respect the old and learned, and is cruel without provocation.' 42. Rama had become parched, oppressed by his troubled mind, completely faint with fever, like a great pool thronged with darting creatures, completely wasted by heat; and [suddenly] the welcome rain (tears of joy) fell without a cloud.

VOL. XX.

23

354

C. HOOYKAAS

43. Then the monkeys assembling followed Rama, who was like Laksmana in form and dress, who held out his fingers as an order to advance, and whose polite command was accepted with a bow by Sugriva. 44. Then the two kings, mounting on Hanumat's back, and the monkeys with their eyes red with flashing fire, quitted (left) the ground, went into the sky and quickly arrived at Mount Mahendra, 45. which stands as if to protect the earth all round from the assault of the sea's waves, extending in the space between sky and earth its mass which withstands the ocean's impulse, 46. with its roots planted in the serpents' abode, touching the gods' world with its hundreds of peaks, filling the quarters with its solid extensive flanks, with its pleasant thickets of trees laden with fruit and flowers, 47. clearly imitating with the humming of its bees the [sweet] tones of his dear one and with its lotuses the charm of her face and laughter, and quickly causing great delight to the lord of men, 48. touching with its peaks, as if in passion with a [lover's] hands, the broad delightful expanse (buttocks) of the sky, with its jewel-girdle of planets, with its unsurpassed possession of beauty and with its cloud-garment taken off. 49. Avoiding [as it were] unsteady, light people, incapable of bearing burdens, unequal, devoid of strength (pride, comm.) [they resorted to Mt. Mahendra which is] steady, of matchless height, bearing lofty clouds and dwelling as it were beside the ocean, 50. causing the divine women to believe it was the god's city, with its crystal chambers provided with jewel-lamps, and with the sounds of young kinnaras singing, free from sorrow, and with many wish-granting trees. 51. Then the monkey-troops, accompanied by Raghu's sons, raising their eyes, saw, indicated by Hanfmat's finger, the [southern] quarter where Sita was, with the ocean intervening, dim with smoke issuing from it. 52. They went from the thickets of Mt. Mahendra, that hid the sun's rays with their mass, to the sea, which, though capable of carrying the earth with its billowing masses of water, yet does not overflow its shores, 53. which dispels the dense darkness of the underworld with the radiance of its pearl-shells containing large heavy gems, and on high obstructs the course of the sun's rays with its masses of light floating diamonds, 54. whose water is swollen by the pure rivers that increase their flow at night, thus clearly showing that Mahendra'sslopes are full of moonstones and (hence) laden with water, 55. containing the mountains and the snakes that hold up the earth, which are able to support the world, unsurpassed in their splendour, bearing many shining gems, of great extensive form, and with tortoises and sharks helpless with exhaustion, hiding in them.(?) 56. They beheld the great waves, which like clouds sprinkled great masses

ON SOME ARTHALANKARAS

IN THE BHATTIKAVYA

355

of spray (rain drops), produced rainbows shining like clear gems, sounded deep and pleasant, and removed the heat of the earth, 57. where the sea-shore and the mountains shone (appeared), adorned (respectively) by coral and by gems, with their forms embellished by masses of pearls and fruits (respectively), and assailed by the waves and by elephants (respectively). 58. 'How can this really be the gem-filled ocean that fills the whole underworld, and hides the sky with mountainous waves ? ' [thinking] so, when they came to it they thought the ocean was an illusion, 59. [they regarded the ocean as] full of beauty, though without a moon; of unimpaired lustre, though the gods had taken Laksmi from it; excelling the sky with its masses of water, though it had been churned by the gods, and of undiminished splendour; 60. carrying the earth, mountain-ranges, the snake gesa and the celestial elephants, like a ship borne on the sea, excelling with its actions even the Great Boar, who supported the agitated earth with his snout as massive as a mountain; 61. bearing a delightful mass of water, the ends of which were the moving rivers attached to the mountains, like the white silken cloth of the earth's mountain-breasts, slipping off when she saw Rama. 62. The marvellous, pure and mighty ocean shone extremely when attained by the monkey-chief and Laksmana and Rama, who were of immense and marvellous power, pure and unsurpassable. 63. As if showing them when they saw it that there is no greatness without adversity, the ocean let its broad, extended, mountain-like waves become continuously every moment calmed. 64. The Love-God, skilful to no purpose, pierced Rama with his soft flower-arrows,but made no wound, and burned him with his breezes cool as water, but caused no fever. 65. Then the sun and Rama, with their splendour faint and dim at the end of the day, having come close to the ocean after passing over the world, made each his form the likeness of the other's. 66. Then the darkness with its cloud-lustre increased together with the growth of Rama's love, completely taking away his comforts and concentrating his thoughts entirely on his dear one. 67. Then the moon appeared dispelling the darkness over the sea and giving sight to the eyes, as if creating again the hidden world; for every great being acts for the advantage of others. 68. ' This is a thunderbolt-but how can that be in a cloudless sky ? It is a shower of sharp arrows-but that is too impossible without a bow.' In this way the love-lorn Rama [wondered] about the moon, and could not decide it was the moon. 69. Spreading its rays on the waterlily-clusters and on the faces of the

356

C. HOOYKAAS

quarters [imagined as women] from which darkness was dispelled, and over the sky, the moon shone in a way that nothing but the moon does. 70. The darkness went as if for shelter to the thicket where its enemies the moonbeams were excluded by the trees, and as if frightened took refuge with its rain-cloud-lustre in the interstices of great irregularrocks. 71. Then his younger brother, charming to the eye and delightful like the Love-God abiding in his mind, yet not perverse [as the Love-God is] spoke to R&ma in a voice like the thunder of the rain-cloud: 72. ' Make your enemies' wives to have their waving locks cut short because of their husbands' deaths, and their collyrium and lip-paint to be washed off by their tears; cease your sorrow; what place has despair in you, saviour of the world ? 73. 'In the world of men one who has attained greatness suffers the worst fall if he is careless: an elephant-leader as tall as a big mountain-peak, if he gets into mud, sinks, being heavy-but wood does not. 74. 'There is nothing to be known which you do not know; nothing you do, even closing your eyes, is without intention; yet my great love, engendered by your merits and fearing disaster for you, impels me to speak.' 75. After hearing Laksmana's words, Rama with a yawn extended his arms and became sleepy; (longing to lie down he) mounted a couch of leaves and ordered the monkeys to keep guard in every quarter. According to Kane in his HSP Bhatti must have lived ? A.D. 600, and the theoretical works which show the most close relation to the BhK are the by Bhamaha (Bh.) and the Kdvyadarsaby Dandin (D). According KavySlainkdra flourished after A.D. 700 and Dandin about 660-80. Then Bhamaha Kane to from about or a little later than there is Udbhata's Alairkdrasdrasahgraha from about A.D. 800 according A.D. 700 and Vamana's Kdvydlaitkdra-sutra to the same authority. Kane considers these five authors as so closely related in time, in method of dealing with their subject and terminology used, that he draws up an alphabetical list of alankaras defined or referred to by Bhatti, Dal.din, Bhamaha, Udbhata, and Vamana in ? 13 on pp. 139-42. Bhatti in his mahakavya found no opportunity to quote his authorities, leaving that to his commentators, of whom 13 are known during these 13 is comparatively an old one according centuries. The commentary Jayamanigald to Kane, who makes its author flourish between A.D. 800 and 1050. Such a relatively difficult work as the BhK, however, needed its commentary from the very outset. It appears that the copyists of the MSS acted, as it were, as pre-commentators during the first centuries of the BhK's existence, and Trivedi in his text-edition + commentary (BSS, LVI and LVII, 1898) continuously quotes the technical terms which the copyists of the MSS applied to the poetic figures exemplified in the BhK x. The first copyists should have been able to

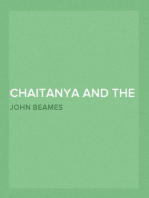

SYNOPTICAL TABLE showing 40 ARTHALANKJRAS BHATTI'S Ravavzavadha(? 600) x. 1 Anuprdsa (alliteration) 2-22 Yamaka (four-line-chime) Ix. 1-7 A summing up of arthalankdras 23 Adi-Dipaka (begin-illuminator) 8-13 Svabhavokti Bh. In. 93-4; BhK 51 ? 24 Anta-Dipaka (end-illuminator) BhK 31-5 14-65 Upama 25 Madhya-Dipaka (or: Atisayokti ?) BhK 26-30 66-96 Rfpaka (metaphor) 27 Kamalaka-Rupaka 26 Rfipaka BhK 23-4 97-119 Dipaka 28 Khanda- or Avayava-Ripaka BhK 38 120-68 Aksepa 30 Lalamaka-Rupaka 29 Ardha-Ruipaka BhK 37 169-79 Arthantaranyasa 32 Yathopama 31 Ivopama BhK 40 180-98 Vyatireka 34 Taddhitopama 33 Sahopama BhK 41 199-204 Vibhavana 36 Samopama 35 Luptopama BhK 42 205-13 Samasokti 37 Arthantaranyasa (corroboration) BhK 50 214-20 Atisayokti BhK 45 38-9 Aksepa (interdiction, suppression) 221-34 Utpreksa 40 Vyatireka (outmatching) BhK 73 235-59 Hetu 41 Vibhavana (surmised cause of effect) BhK 43 260-4 Sfk$ma (the subtle) 42 Samasokti (concise assertion) 265-72 Lava or Lesa (the slender) 43 Atisayokti (or Suksma) or Svabhavokti ? BhK 44 Krama (relative order) 273-4 44 Yathasankhya (enumeration) + Samahita ? 281 srnigara 45 Utpreksa (figurative expression) 283 raudra 275-80 Preyas = Priti 46 Varta (mere mention; not in D; Bh. ii. 87) 285 vira (Mallinatha: Atisayokti) 287 karunya 281-92 Rasavat 47 Preyas or Priti (the joyous) 288 bibhatsa 293-4 48 Rasavat Urjasvi 289 (the impassioned) hasya 49 Urjasvi (the vigorous) adbhuta 290 295-7 50 291 Paryayokta Paryayokta (periphrasis) or Bhrantiman ? bhayanaka 51 Samahita (facilitation) or Svabhavokti ? BhK 51 Samahita 298-9 52-4 Udara or Udatta (the exalted) BhK 52-4 Udara or Udatta 300-3 55-7 Slesa (paronomasia) 304-9 Apahnuti 58 Apahnuti (concealment) 310-22 Slista or glesa (double meaning) 59 Visesokti (statement of difference) BhK 59 323-9 Vise$okti 60 Vyajastuti (disguised eulogy) BhK 62 330-2 Tulyayogita 61 Upama-Rfipaka (simile-metaphor) (xi. 88 Upama-Rfipaka) 62 Tulyayogita (equal pairing) BhK 64 333-9 Virodha 63 Nidarsana (illustration) s 340-2 Aprastutaprasam. 64 Virodha (apparent contradiction) BhK 60 343-7 Vyajastuti 65 Upameyopama (their alternation) 348-50 Nidarsana (II. 18 Anyonyopama) 66 Sahokti (conjoint description) BhK 66 351-4 Sahokti 67 Parivrtti (barter or exchange) Parivrtti (II. 26 Sams.ayopama) 355-6 68 Sasandeha (with uncertainty) (n. 37 Asadharanopama) 69 Ananvaya (without comparison) (n. 221-34 Utpreksa) 70 Utpreksavayava (utpreksa + complications) BhK 72 357 Asis 71 Samsrsti or Saikirna (co-mixture) BhK 71 358-62 Saikirna or Samsrtti 72 Asis (benediction) Bh. II. 85 363 Vakrokti 73 Hetu (cause; DII. 235-59; Bh. ii. 86 not) 364-6 Bhavika 74 Nipuna 367 Subjects not dealt with 75 Paryayokta (periphrasis) ? 368 Concluding stanza DANDIN 'S Kavyddarsa (660-80)

358

C. HOOYKAAS

apply the correct terms to the figures, but as time went on other interpretations were presented; Professor Kane had to be very short here.1 In my critical remarks I shall not consider the stanzas in the sequence in which they occur in the poem. My opinion is that the commentaries were generally right in so far as they consulted Bh. and especially D and used their terminology, but wrong in clinging too strictly to the sequence in which dealt with there. they found the arthalainkdras 1. BhK x. 25. The commentators, expecting to find Madhyadipaka exemplified here, attribute this alafikara to this stanza. Bh. ii. 28 exemplifies this figure in the following way: Malinir amsuka-bhrtah Spring adorns women 'lafikurute madhuh; who wear garlands and garments; striyo harita-suka-vacas ca the joyous chatterings of birds such as the pigeon bhu-dharanam upatyakah and the parrot adorn the declivities of mountains. D ii. 103 is the only example composed on the same principle as that in Bh.: Nrtyanti niculotsafge (They) dance at the foot of the nicula (tree) and sing; the peacocks do, gayanti ca kaldpinah, badhnanti ca payodesu and fix upon the watery clouds drsam harsasru-garbhiniim.an eye welling with tears of joy. It will be clear that the examples from the theorists (Udbhata I. *16 too) have their dominant words, the subject, at the end of the second pada; in the BhK, however, we find there part of a concessive clause: patatam yady api sammatdjave, Garudanila-tigma-rasmayah acirena krtartham agatam tam amanyanta tathapy ativa te. It seems far-fetched to classify this stanza as Madhyadipaka because sammatdcomes in its middle and the cognate word amanyantalater. Accepting Mallinatha's solution that here we have to do with a sainkaraof Kavyaliiga (not in D and Bh.) and Atisayokti implies the sound suggestion of interrupting the triad Upamd-Rlapaka-Dipaka. Bhatti cannot be expected to have exactly followed the order of arthalaiinkrasin Bh. or D. 2. BhK x. 28 offers an example of the advantage of consulting the older authorities. According to the author of the Jayamaigald it is Sesdrthinvavasita- or Khanda-riupaka or Avatarmsaka (Rupaka-with-the-last-part-attached,

1 In order to make amends to Professor Kane, to whom all Indologists owe so much in

this study in general, and to whose HSP with its paragraph on the Visnu-dharmottara-Purdaia particular is indebted, I propose to add a 27th argument to his a-z list pleading for D's priority to Bh. In BhK x. 63, alafikara Nidarsana, Bhatti uses iva. Bh. in. 33 in this connexion vetoes yathd, iva, and -vat in this figure; D does not mention this point. I am inclined to consider a vetoing authority as the younger of the two, and the poet Bhatti who used it freely and the ignoring authority as the older.

ON SOME ARTHALANKARAS IN THE BHATTIKAVYA X

359

Fragmentary Rupaka, or Hanging (Pending) Rupaka). Trivedi adds that Khanda-R corresponds to the Savayava-R of later alahkarikas, a-khanda-R to Niravayava-R. This is exactly what D exemplifies in ii. 71, and explains in ii. 72 as Avayava-R, and historically speaking it seems preferable to use this term. 3. BhK x. 43. The figure exemplified here is called Atisayokti by the commentators. Bh. ii. 81 defines: 'Where something transcending ordinary experience is described, but not without a reason, it is regarded as the figure Atiayokti '. Bh. exemplifies this first in 82: 'The saptacchada trees being rendered invisible by moonlight, which is of the colour of its flowers, were inferred from the hum of bees '. In 83, describing women disporting themselves in water with garments so thin and white that they look as if the water itself had cast a skin, he gives this stanza: ' If like snakes water should shed a skin, then this skin would be the white garments on the bodies of women in the water'. In the BhK x. 43 I fail to see conformity with this definition and these examples. D ii. 214-20, in his definition and examples of Hyperbole is perfectly clear and he corresponds exactly with Bh., and is consequently of no help to explain why the MSS of the BhK should have ascribed the application of this figure here to Bhatti. Trivedi displays a great amount of learning in his annotation, but fails to point to the fact that there can be no question, here, of atisaya. It looks as if the copyists of the Bhatti MSS, having stated that Bhatti dealt with Arthtntaranyssa, Aksepa, Vyatireka, Vibhdvani, and Samdsokti (nearly) in the same order as Bh. and D (and probably other theorists also), and knowing that the next figure in Bh. and D (and probably their contemporary textbooks also) was Atisayokti, somewhat automatically ascribed this designation to stanza 43. Two stanzas further on Bh. mentions Suiksma,which figure he excludes from treatment; D after Atisayokti deals with Utpreksd(221-34) and Hetu (235-59), and in 260 defines: ' A thing gathered from gesture or posture is, by reason of its subtleness, known as The Subtle (Siksma)'. Now the BhK x. 43 also mentions a gesture as well as a posture, but they are so explicit that not much subtle is left. But Bhatti's preceptor may have diverged. Or must we follow Mallinatha and call the figure used here Svabhdvokti ? It would be in accordance with Bh.'s dealing with this figure at this stage

(II. 93-4).

4. BhK x. 50. The figure exemplified here is said to be Parydyokta (Periphrasis). Bh. III. 8 defines and introduces as follows: ' Parydyokta is the statement of an idea in a manner different from the normal or ordinary one, as where Krsna addressing gisupala in the Ratndharana spoke in this way: (9) "We do not eat, either at home or abroad, food which is not eaten by Brahmins learned in the Vedas "; this is to prevent poison being administered '.

360

C. HOOYKAAS

D II. 295 defines: ' Without actually making an intended statement, the expressing of the same in another manner (but) calculated to serve the same end, is considered as Periphrasis'. D 296 exemplifies: 'This cuckoo is biting the blossoms of the mango; I will drive him off; you two may remain (here) undisturbed'; and in 297 explains: 'Thus having united her friend with a young person at the appointed place, with a view to bringing about their loving dalliance, a certain woman makes an excuse to leave that place '. I doubt whether Bh. or D would have applied Parydyoktato this stanza in Bhatti. Mallinatha proposes the figure Bhrdntimdn, 'describing an error'. This term would fit, but the figure and its name both were unknown to Bh. and D. 5. BhK x. 75. When the commentators had reached the end of this sarga, they attributed the untraced term Nipuna to the last stanza but one and took the last stanza as a concluding stanza. Now it does exemplify four grammatical points, but would it be too far-fetched to surmise that it also used the arthalankdraParydyokta? This figure would fit in here, better than in 50. Heroic personages do not suffer from mosquito bites and tropical ulcers, indigestion or dysentery, drowsiness or sleep, and it cannot escape our attention that the hero par excellence, a superhuman being who is an avatara of Visnu, stretches his arms and yawns. This seems too human an action and as such contrary to royal as well as to poetic etiquette-unless the poet meant to present a periphrasis of Rama's complete relaxation, because once again he feels confident in the future and sure of himself. The acceptance of this explanation incorporates this concluding stanza in Bhatti's teaching of alafkara in this sarga and attributes an appropriate place to the hitherto discarded Paryayokta, which otherwise would have been an alankara used by D and Bh. but not to be found in the BhK. 6. BhK x. 51. Commentators find here the figure Samihita exemplified, a figure on which Bh. IIi. 10 is short and clear: ' (The figure) Samahita is thus (illustrated) in (the literary work called) Rajamitra: "To the damsels as they went to propitiate Rama, Narada appeared in front (as a help) " '. This exemplification does not harmonize very well with the BhK x. 51; nor does the definition in D II. 298: 'When unto one about to commence a certain action there results, through the influence of go o d 1luc k, a further accession of means for the same (end), that they call Facilitation, e.g. (299) While with a view to remove her angry pride I was about to prostrate myself at her feet, f o r t u n a t e 1y there arose, to favour me, this roaring of the clouds '. In the Bhatti-stanza there is no vestige of good luck, arriving fort u n a t ely; the commentators seem simply to have followed the list Preyasand to have run off the metals there. Mallinatha, however, Rasavat-Urjasvm here proposes Svabhdvokti'nature-description ', and I agree. Bh. expresses strong doubt regarding the advisability of including this alahkara, with which

ON SOME ARTHALANKARAS

IN THE BHATTIKAVYA

361

he deals only at the end of his Pariccheda I : 'Some are of the opinion that Svabhdvoktiis an alafikara; it consists of objects being described as they are in nature; e.g. (ii. 94) By shouting out, by calling others, by running round and round, and by crying, the little boys ward off with a stick the cattle that stray into the crops'. in ii. 8: ' Making D, who is anterior to Bh., deals first of all with Svabhdvokti manifest bodily the (real) nature of things in varying situations', and after four examples concludes in 13 : ' It is this very (description) that rules supreme in scientific treatises; and in poetry too the same is in requisition '. The Bhatti-stanza is very well characterized by Svabhdvokti-but then what about the Samdhita ? The stanza next to be considered will provide the answer. 7. BhK x. 44 according to the commentators exemplifies Yath&sazkhya (' enumeration'), a figure which in Bh. ii. 88-90 also precedes Utpreksa. Bh. In. 89 defines: 'When many different things (having nothing in common) are set out, and when they are subsequently referred to in the same order, the figure of speech is known as YathdsaAkhya'. His example is the amazing stanza 90: 'The lotus, the moon, the bee, the elephant, the he-cuckoo, and the peacock are defeated by your face, brightness, glance, gait, speech, and braid of hair'. A transposition into more common language of this mnemotechnic wonder would read: 'Your face (0 my beloved one) outshines the lotuses; your brightness surpasses that of the moon', etc. The Bhatti-stanza is a good exemplification of Yathdsaikhya; here the question could be put whether at the same time it could be considered to be an exemplification of Samahita, the figure which did not fit very well in 51 above. For Hanfumat,Vayu-putra, who takes Rama and Laksmana on his back and carries them through the air, thus sparing them the wearisome ascent of the enormous Mt. Mahendra, is a real God-send, just as Narada in the exemplifying stanza of the Samahita. 8. BhK x. 46 is considered to exemplify Varta, dealt with by Bh. in one stanza only and immediately after he has refused to deal with the figures Hetu, Suksma, and Lesa or Lava. It (ii. 87) runs as follows: 'The Sun has set; the Moon shines; the birds are winging back to their nests.-What kind of poetry is this ? This is called Vdrt '. One feels convinced that Bh. was no protagonist of this 'poetic figure', perhaps loathed it, and dealt with it in an extraordinarily short manner, in suggestive surroundings moreover. This word vdrtd in the dictionaries is rendered by 'intelligence, news, tale, story, mention of', and Monier-Williams gives: 'the mere mention of facts without poetical embellishment (in rhet.)'. The BhK x. 46 exemplifies a textbook posterior to the VdhP, where only 18 alafkaras are known. The whole enumeration of ch. xiv is to be found in Kane's HSP on p. 69; llab runs as follows: Yatha sva-rfipa-kathanam Vdrteti parikirtitam, . . . Kane adds between brackets: MS : Svabhdvoktih prakirtita, . . .

362

C. HOOYKAAS

Remarkably enough D does not mention vdrtdas a technical term, but when dealing with Hetu 'cause', he produces the same Sun-set and Moon-rise, followed by the remark (ii. 244 cd): ' . . . is good enough when an indication of the (hetu " cause ") time is intended'. Obviously this was a contended

topos.

This, I think, at any rate is certain, that D chronologically and spiritually stood nearer to Bhatti than did Hemacandra, who suggested that the mention of Sun-set and Moon-shine might mean: 'This is time to go to the lover. Stop work. Perform saindhyd. Don't go far. Get the cows homewards. No heat hereafter. Gather the things exposed for sale', etc. But this would be Parydyokta, found already in the BhK x. 75, and dealt with under sections 4 and 5 above. Mallinatha's Atisayokti then would seem more probable. 9. BhK x. 74 has been labelled Nipuna, a word unknown hitherto as a technical term in poetics, not appearing as such in Monier-Williams. But in the course of the preceding stanzas we could observe that when Bhatti deals with a poetical figure in more than one stanza, this practice corresponds to D's use of half a dozen stanzas at least to define, subdivide, and exemplify a figure, viz. Dipaka 3 : 23, Rupaka 5 : 31, Upamd 6 : 52, Aksepa even 2 : 49, Slesa 2 : 13-the only exception being Uddra/Uddtta with 2 : 4. The reverse is also true: where D needs (more than) a dozen stanzas, Bhatti cannot do with one stanza to exemplify, but needs 2 or 3-with the exceptions, however, of Vyatireka(19 : 1) and Utpreksd(14 : 1). As a consequence, since D devotes 25 stanzas to Hetu, the figure illustrated in the preceding stanza BhK x. 73, in the endeavour to analyse Nipuna it is not beside the point to ask ourselves whether it could be explained as being a kind of Hetu. D in 235 cd expresses his views quite clearly: ' Hetu is either Kdraka (" efficient ") or Jnipaka (" probatory'"), and both of them have numerous varieties'. We might expect that BhK x. 73 had been meant to exemplify Hetu (Kdraka) and BhK x. 74 that of (Hetu) Jnipaka, which last term might have survived in the commentaries as Nipuna. However, both definition and exemplification diverge too much to be applicable here. Still there is another possibility left. Contrary to Bh. who disapproved of the use of Hetu, Suiksma, and Lava (Lesa), D extols them in 235 by saying 'The Cause, the Subtle, and the Little/Slender are the best embellishments of speech'. Bhatti omnium consensu used Hetu in 73, perhaps Siksma in 43 (see above, section 4), and therefore we may expect that he uses Lava/Lesa also. D defines in 265: ' The Slender is the concealing by some slender (pretext) of the nature of a thing about to be disclosed. It is in the illustrations alone that the nature of this (figure) will become evident'. From his exemplifications I only quote the second stanza 267; in 268-72 D exemplifies a slender Ninddstuti obviously found in the treatises of his predecessors (' others consider') and not discarded by him who was only too

ON SOME ARTHALANKARAS

IN THE BHATTIKAVYA * .

363

fond of subdivisions and varieties. It runs: 'How now! At the very sight of this girl my tears of joy are falling '-' my eye is sore by reason of the windwafted pollen from the flowers '. Unfortunately from the BhK x. 74 the clause 'Nothing you do, even closing your eyes, is without intention ', does not give much of a clue in connexion with this alankara. Non liquet for the moment seems the only answer. But I postulate an alankarika between the VdhP with its 18 alankaras and D + Bh. with their ? 40 + numerous subdivisions, who distinguished between 'willed cause' (e.g. murder) and 'not-willed cause' (e.g. lethal accident), 73 being the exemplification of unintentional cause, 74 that of intentional cause. This supposition, however, is no longer knowledge but forms part of divination. As a technical term Nipuna seems to be authentic, for the word occurs in the first verse of the stanza OJR xi. 94 = BhK x. 74, just as BhK x. 48 uses rasa in the first verse of its stanza illustrating Rasavat, and BhK x. 49 uses urjita in the second verse of its stanza exemplifying Urjasvl. In the preceding pages different meanings and names have been attributed to some of Bhatti's alankaras; perhaps the poet of the Old-Javanese Rimayana Kakawin knew of these. This attribution was made possible by turning from the younger alainkrikas to the older ones who lived shortly after Bhatti like Bhamaha and Dandin, or even preceded him like the author of the Visnudharmottara-Purdna. Unfortunately not much conclusive proof could be found, but the endeavour seemed worth while in view of the fact that the BhK, by being a prototype for the OJR, has influenced the Old-Javanese literature.

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- The Catuhsataka of Aryadeva - Bhattacharya.1931.part II PDFDocument336 pagesThe Catuhsataka of Aryadeva - Bhattacharya.1931.part II PDF101176Pas encore d'évaluation

- Alikakaravada RatnakarasantiDocument20 pagesAlikakaravada RatnakarasantiChungwhan SungPas encore d'évaluation

- Michael Hahn - Philipps University Marburg - AcademiaDocument8 pagesMichael Hahn - Philipps University Marburg - Academialinguasoft-1Pas encore d'évaluation

- Vyakhyayukti 9178 9469 1 SMDocument55 pagesVyakhyayukti 9178 9469 1 SMLy Bui100% (1)

- Annals of The B Hand 014369 MBPDocument326 pagesAnnals of The B Hand 014369 MBPPmsakda HemthepPas encore d'évaluation

- Appaya DikshitaDocument15 pagesAppaya DikshitaSivasonPas encore d'évaluation

- The Prajñā-Pāramitā-Ratna-Guna-Samcaya-GäthāDocument18 pagesThe Prajñā-Pāramitā-Ratna-Guna-Samcaya-Gäthācha072100% (1)

- Ames W - Notion of Svabhava in The Thought of Candrakirti (JIP 82)Document17 pagesAmes W - Notion of Svabhava in The Thought of Candrakirti (JIP 82)UnelaboratedPas encore d'évaluation

- Buddhist Philosophy of Language in India: Jñanasrimitra on ExclusionD'EverandBuddhist Philosophy of Language in India: Jñanasrimitra on ExclusionPas encore d'évaluation

- Journal of Buddhist StudiesDocument20 pagesJournal of Buddhist StudiesAadadPas encore d'évaluation

- Vaikhanasa Daily Worship1Document5 pagesVaikhanasa Daily Worship1NK PKPas encore d'évaluation

- Shakya Chokden's Interpretation of The Ratnagotravibhāga: "Contemplative" or "Dialectical"?Document13 pagesShakya Chokden's Interpretation of The Ratnagotravibhāga: "Contemplative" or "Dialectical"?Thomas LeorPas encore d'évaluation

- Apple J.B.-The Single Vehicle (Ekayana) in The Early SutrasDocument31 pagesApple J.B.-The Single Vehicle (Ekayana) in The Early Sutrasshu_sPas encore d'évaluation

- Kāludāyi's VersesDocument48 pagesKāludāyi's VersesAruna Goigoda GamagePas encore d'évaluation

- Hattori - PSV V - W Jnendrabuddhi Comm - Chap 5Document124 pagesHattori - PSV V - W Jnendrabuddhi Comm - Chap 5punk98Pas encore d'évaluation

- Review Patañjali's Vyākaraṇa-Mahābhāṣya. Samarthāhnika (P 2.1.1) by S. D. Joshi PatañjaliDocument3 pagesReview Patañjali's Vyākaraṇa-Mahābhāṣya. Samarthāhnika (P 2.1.1) by S. D. Joshi PatañjaliMishtak BPas encore d'évaluation

- Coomaraswamy A Yakshi Bust From BharhutDocument4 pagesCoomaraswamy A Yakshi Bust From BharhutRoberto E. GarcíaPas encore d'évaluation

- Norman 1994 Asokan MiscellanyDocument11 pagesNorman 1994 Asokan MiscellanyLinda LePas encore d'évaluation

- (Brill's Indological Library 20) Kevin McGrath - The Sanskrit Hero - Karna in Epic Mahābhārata-Brill Academic Publishers (2004) PDFDocument273 pages(Brill's Indological Library 20) Kevin McGrath - The Sanskrit Hero - Karna in Epic Mahābhārata-Brill Academic Publishers (2004) PDFVyzPas encore d'évaluation

- RH-032 Jatakamalas in Sanskrit. Pp. 91 - 109 in The Sri Lanka Journal of The Humanities. Vol. XI. Nos. 1 and 2. 1985 (Published in 1987)Document19 pagesRH-032 Jatakamalas in Sanskrit. Pp. 91 - 109 in The Sri Lanka Journal of The Humanities. Vol. XI. Nos. 1 and 2. 1985 (Published in 1987)BulEunVen0% (1)

- Suttanipata PTS AndersonSmith 1913Document234 pagesSuttanipata PTS AndersonSmith 1913flatline0467839100% (1)

- UtrechtDocument31 pagesUtrechtAigo Seiga CastroPas encore d'évaluation

- Story of The Gita Govinda AND The Rasa TraditionDocument25 pagesStory of The Gita Govinda AND The Rasa TraditionPraveen sagar100% (1)

- Room at The Top in Sanskrit PDFDocument34 pagesRoom at The Top in Sanskrit PDFcha072Pas encore d'évaluation

- Sen 1974 Studies in The Buddhist Jatakas Tradition and PolityDocument141 pagesSen 1974 Studies in The Buddhist Jatakas Tradition and PolityLinda LePas encore d'évaluation

- The Rasa Theory and The DarśanasDocument21 pagesThe Rasa Theory and The DarśanasK.S. Bouthillette von Ostrowski100% (2)

- Alamkara-Contribution To Poetics and Dramaturgy-Sures Chandra BanerjiDocument23 pagesAlamkara-Contribution To Poetics and Dramaturgy-Sures Chandra BanerjiBalingkang100% (1)

- Annals of The Bhandarkar Oriental Research Society Vol. 14, 1935-36Document458 pagesAnnals of The Bhandarkar Oriental Research Society Vol. 14, 1935-36mastornaPas encore d'évaluation

- Alamkaramakarandam A Pre Modern Treatise On PoeticsDocument199 pagesAlamkaramakarandam A Pre Modern Treatise On PoeticsAganooru VenkateswaruluPas encore d'évaluation

- Preservation of ManuscriptsDocument12 pagesPreservation of ManuscriptsMin Bahadur shakya100% (1)

- Karashima 2009 A Sanskrit Fragment of The SutrasamuccayDocument15 pagesKarashima 2009 A Sanskrit Fragment of The SutrasamuccayVajradharmaPas encore d'évaluation

- On Deconstruction and ApohaDocument40 pagesOn Deconstruction and ApohaSivasenani NoriPas encore d'évaluation

- RH-054 Three Sanskrit Texts On Caitya Worship-Ratna Handurukande+ocrDocument167 pagesRH-054 Three Sanskrit Texts On Caitya Worship-Ratna Handurukande+ocrBulEunVenPas encore d'évaluation

- Bhamati CatussutriDocument647 pagesBhamati CatussutriAshwin Kumble100% (1)

- Impressive Sculpture of Shiva Battling the Elephant 35Document20 pagesImpressive Sculpture of Shiva Battling the Elephant 35Rahul GabdaPas encore d'évaluation

- ŚrīsahajasiddhiDocument24 pagesŚrīsahajasiddhicha072100% (1)

- Subkhashita Litarature PDFDocument31 pagesSubkhashita Litarature PDFWackunin100% (1)

- The Spitzer Manuscript and The MahabharDocument13 pagesThe Spitzer Manuscript and The MahabharRahul SinghPas encore d'évaluation

- Jiabs 19-1Document176 pagesJiabs 19-1JIABSonline100% (1)

- The Rite of Durga in Medieval Bengal An PDFDocument66 pagesThe Rite of Durga in Medieval Bengal An PDFAnimesh NagarPas encore d'évaluation

- Theory of Apoha On The Basis of The Pram1Document20 pagesTheory of Apoha On The Basis of The Pram1Dr.Ramanath PandeyPas encore d'évaluation

- Abhinava Aesthetics LarsonDocument18 pagesAbhinava Aesthetics Larsondsd8g100% (2)

- A History of Pingala's Combinatorics (Jayant Shah)Document44 pagesA History of Pingala's Combinatorics (Jayant Shah)Srini KalyanaramanPas encore d'évaluation

- BRILL'S IDEOLOGY AND STATUS OF SANSKRITDocument20 pagesBRILL'S IDEOLOGY AND STATUS OF SANSKRITKeithSav100% (1)

- Nihom, Max Vajravinayā and Vajraśau ADocument11 pagesNihom, Max Vajravinayā and Vajraśau AAnthony TribePas encore d'évaluation

- Staal Happening PDFDocument24 pagesStaal Happening PDFВладимир Дружинин100% (1)

- Siva Sutra PaperDocument16 pagesSiva Sutra PaperShivaram Reddy ManchireddyPas encore d'évaluation

- Gregory Schopen - The Text On The "Dhāra Ī Stones From Abhayagiriya": A Minor Contribution To The Study of Mahāyāna Literature in CeylonDocument12 pagesGregory Schopen - The Text On The "Dhāra Ī Stones From Abhayagiriya": A Minor Contribution To The Study of Mahāyāna Literature in CeylonƁuddhisterie2Pas encore d'évaluation

- JIP 06 4 ApohaDocument64 pagesJIP 06 4 Apohaindology2Pas encore d'évaluation

- MeghadutamDocument7 pagesMeghadutamtaditPas encore d'évaluation

- Sanskrit BuddhacaritaDocument121 pagesSanskrit BuddhacaritaMahender Singh GriwanPas encore d'évaluation

- Ancient Indian Logic Diagram Depicted in Buddhist TextDocument6 pagesAncient Indian Logic Diagram Depicted in Buddhist TextShim JaekwanPas encore d'évaluation

- BKŚS13Document30 pagesBKŚS13av2422Pas encore d'évaluation

- Iṣṭis to the Lunar Mansions in Taittirīya-BrāhmaṇaDocument21 pagesIṣṭis to the Lunar Mansions in Taittirīya-BrāhmaṇaCyberterton100% (1)

- Buddhacarita of Asvaghosa A Critical Study PDFDocument12 pagesBuddhacarita of Asvaghosa A Critical Study PDFManjeet Parashar0% (1)

- Into the Twilight of Sanskrit Court Poetry: The Sena Salon of Bengal and BeyondD'EverandInto the Twilight of Sanskrit Court Poetry: The Sena Salon of Bengal and BeyondPas encore d'évaluation

- Kuvalayamala 2Document14 pagesKuvalayamala 2Priyanka MokkapatiPas encore d'évaluation

- Kuvalayamala 1Document7 pagesKuvalayamala 1Priyanka MokkapatiPas encore d'évaluation

- Dhvanyāloka 1Document21 pagesDhvanyāloka 1Priyanka MokkapatiPas encore d'évaluation

- Bronze Weights in The Western Han DynastyDocument13 pagesBronze Weights in The Western Han DynastyPriyanka MokkapatiPas encore d'évaluation

- Influence of Sanskrit On Chinese ProsodyDocument97 pagesInfluence of Sanskrit On Chinese ProsodyPriyanka Mokkapati100% (1)

- Book of Vermilion FishDocument94 pagesBook of Vermilion FishPriyanka MokkapatiPas encore d'évaluation

- Dvatai As DeconstructionDocument20 pagesDvatai As DeconstructionPriyanka MokkapatiPas encore d'évaluation

- Jaina Goddess TraditionsDocument22 pagesJaina Goddess TraditionsPriyanka Mokkapati100% (1)

- Indian Sculpture Newly AcquiredDocument10 pagesIndian Sculpture Newly AcquiredPriyanka MokkapatiPas encore d'évaluation

- Dhvanyāloka 2Document19 pagesDhvanyāloka 2Priyanka MokkapatiPas encore d'évaluation

- Buddhist Cave Shrine As Mirror HallDocument29 pagesBuddhist Cave Shrine As Mirror HallPriyanka MokkapatiPas encore d'évaluation

- Coconut and Honey. Telugu and SanskritDocument18 pagesCoconut and Honey. Telugu and SanskritPriyanka Mokkapati100% (1)

- Basic Jaina EpistemologyDocument12 pagesBasic Jaina EpistemologyPriyanka Mokkapati100% (2)

- Bhasa's Urubhanga and Indian PoeticsDocument9 pagesBhasa's Urubhanga and Indian PoeticsPriyanka Mokkapati0% (1)

- Abhinavagupta To ZenDocument15 pagesAbhinavagupta To ZenPriyanka Mokkapati100% (1)

- An Image of Aditi-UttānapadDocument13 pagesAn Image of Aditi-UttānapadPriyanka MokkapatiPas encore d'évaluation

- AbhidhaDocument86 pagesAbhidhaPriyanka Mokkapati0% (1)

- An Unpublished Fragment of PaisachiDocument13 pagesAn Unpublished Fragment of PaisachiPriyanka Mokkapati100% (2)

- A Textual History of The NatyasastraDocument28 pagesA Textual History of The NatyasastraPriyanka MokkapatiPas encore d'évaluation

- Yuan Mei's Narrative VerseDocument40 pagesYuan Mei's Narrative VersePriyanka MokkapatiPas encore d'évaluation

- Diamond Sutra Vajra Prajna Paramita - Hsuan HuaDocument248 pagesDiamond Sutra Vajra Prajna Paramita - Hsuan HuamrottugPas encore d'évaluation

- Walter Benjamin Otto Dix and The Question of StratigraphyDocument25 pagesWalter Benjamin Otto Dix and The Question of StratigraphyPriyanka Mokkapati100% (1)

- The Prose Style of Fan YehDocument64 pagesThe Prose Style of Fan YehPriyanka MokkapatiPas encore d'évaluation

- Voice Text and Poetic Borrowing in Classical Japanese PoetryDocument52 pagesVoice Text and Poetic Borrowing in Classical Japanese PoetryPriyanka MokkapatiPas encore d'évaluation

- The Structure and Ecology of IndividualisticDocument28 pagesThe Structure and Ecology of IndividualisticPriyanka Mokkapati100% (1)

- The Logic of MohistsDocument55 pagesThe Logic of MohistsPriyanka MokkapatiPas encore d'évaluation

- Two Books Illustrated by HokusaiDocument6 pagesTwo Books Illustrated by HokusaiPriyanka MokkapatiPas encore d'évaluation

- The Original RamayanaDocument19 pagesThe Original RamayanaPriyanka MokkapatiPas encore d'évaluation

- The Long Prose Form in Medieval IcelandDocument33 pagesThe Long Prose Form in Medieval IcelandPriyanka MokkapatiPas encore d'évaluation

- The Fall of Gondolin - J. R. R. TolkienDocument5 pagesThe Fall of Gondolin - J. R. R. Tolkienguwybane0% (1)

- Orror Agic: Steve Jackson GamesDocument14 pagesOrror Agic: Steve Jackson GamesBadDadInMo100% (1)

- Directions: Answer These Questions On A Separate Sheet of Paper, Using Complete Sentences. UseDocument2 pagesDirections: Answer These Questions On A Separate Sheet of Paper, Using Complete Sentences. UseTerria OnealPas encore d'évaluation

- The Drawing Book For Kids: 365 Daily Things To Draw, Step by Step (Woo! Jr. Kids Activities Books) PDF by Woo! Jr. Kids Activities (Paperback)Document3 pagesThe Drawing Book For Kids: 365 Daily Things To Draw, Step by Step (Woo! Jr. Kids Activities Books) PDF by Woo! Jr. Kids Activities (Paperback)balaji817150Pas encore d'évaluation

- Lesson Plan For Year 6 KSSR-SJKDocument6 pagesLesson Plan For Year 6 KSSR-SJKmalathiselvanadam18Pas encore d'évaluation

- MOZZA TILE - Pricelist APR 2021Document3 pagesMOZZA TILE - Pricelist APR 2021Dunia AnakPas encore d'évaluation

- Eye Magazine - Feature - Rub-Down RevolutionDocument5 pagesEye Magazine - Feature - Rub-Down RevolutionKinga BlaschkePas encore d'évaluation

- Full List D&D v3.5 BooksDocument1 pageFull List D&D v3.5 BooksMiguelPas encore d'évaluation

- Song For A Friend Andreya TrianaDocument1 pageSong For A Friend Andreya TrianaGordana BursaćPas encore d'évaluation

- SLK Types of Non FictionDocument18 pagesSLK Types of Non FictionChristian AbellaPas encore d'évaluation

- 4) Shakespeare - Sonnet 130Document10 pages4) Shakespeare - Sonnet 130Reem MohamedPas encore d'évaluation

- The Palace of IllusionsDocument9 pagesThe Palace of IllusionsRishi Raj25% (4)

- Giamarie Marbella - SP Essay Rough DraftDocument11 pagesGiamarie Marbella - SP Essay Rough Draftapi-667933283Pas encore d'évaluation

- Rethinking Lessings Laocoon Antiquity, Enlightenment, and The Limits of Painting and Poetry (Avi Lifschitz (Editor), Michael Squire (Editor) ) (Z-Library)Document446 pagesRethinking Lessings Laocoon Antiquity, Enlightenment, and The Limits of Painting and Poetry (Avi Lifschitz (Editor), Michael Squire (Editor) ) (Z-Library)Manuel FurtadoPas encore d'évaluation

- The Book of Thoth Etteilla PDF - Google SearchDocument2 pagesThe Book of Thoth Etteilla PDF - Google SearchPedro SallesPas encore d'évaluation

- GRADE 7 ICA English Quiz - How The World Began & Indarapatra & SulaymanDocument4 pagesGRADE 7 ICA English Quiz - How The World Began & Indarapatra & SulaymanKat sandaloPas encore d'évaluation

- Steel Ball RunDocument2 pagesSteel Ball RunocramPas encore d'évaluation

- Unit 2 - The English RenaissanceDocument96 pagesUnit 2 - The English RenaissanceBárbara VérasPas encore d'évaluation

- Nursing Research StatisticsDocument7 pagesNursing Research StatisticsDiksha NayyarPas encore d'évaluation

- Biscuit Cracker and Cookie Recipes For TDocument200 pagesBiscuit Cracker and Cookie Recipes For TNever step back SClub100% (1)

- Solo Leveling Volume 1Document378 pagesSolo Leveling Volume 1sirnix841Pas encore d'évaluation

- Holiday Homework for Class 4 Social StudiesDocument5 pagesHoliday Homework for Class 4 Social Studiescfk3ncft100% (2)

- Citing Sources: Grammar-Quizzes More Writing Aids Writing ProcessDocument28 pagesCiting Sources: Grammar-Quizzes More Writing Aids Writing ProcessDarren Dela Cruz CadientePas encore d'évaluation

- Lit 321 TQ MidtermDocument8 pagesLit 321 TQ MidtermknedoPas encore d'évaluation

- The Absurdity of Temporal Existence-1Document2 pagesThe Absurdity of Temporal Existence-1Udoy ShahriarPas encore d'évaluation

- Complex Picture Books and Chapter Book ListsDocument5 pagesComplex Picture Books and Chapter Book ListskrithikanvenkatPas encore d'évaluation

- Shatter City by Scott Westerfeld ExtractDocument29 pagesShatter City by Scott Westerfeld ExtractAllen & Unwin44% (18)

- Interview With Benjamin ZephaniahDocument5 pagesInterview With Benjamin ZephaniahMaru MoléPas encore d'évaluation

- MESBG v0.14Document1 586 pagesMESBG v0.14Anna GarbiniPas encore d'évaluation

- RPG LinksDocument11 pagesRPG LinksSciola Sciola100% (1)