Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

BANik-Country of Origin, Brand Image Perception and Brand Image Structure-Eng (17 Pages) - 442242

Transféré par

Hammna AshrafDescription originale:

Titre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

BANik-Country of Origin, Brand Image Perception and Brand Image Structure-Eng (17 Pages) - 442242

Transféré par

Hammna AshrafDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

The current issue and full text archive of this journal is available at www.emeraldinsight.com/1355-5855.

htm

Country of origin, brand image perception, and brand image structure

Yamen Koubaa

University of Marketing and Distribution Sciences, Kobe, Japan

Abstract

Purpose The purpose of this paper is to explore the impact of country of origin (COO) information on brand perception and brand image structure. Design/methodology/approach Through an analytical review, research hypotheses were built. An empirical investigation was carried out among Japanese consumers. Two brands of electronics with different levels of reputation were investigated. Findings Results showed that COO had an effect on brand perception. This effect differs across brands and across countries of production. Brand-origin appears to be of significant impact on consumer perception. Brand images are found to be multidimensional. Their structures differ across brands and across COO. Research limitations/implications COO has multiple effects on brand image perception. Brand image is multidimensional. This research dealt with one type of product among culturally similar respondents which may limit the finding. Practical implications Marketing actions should be customized across brands with different levels of reputation. Brand image should be assessed as a multidimensional concept incorporating multiple facets. Consumers are influenced by the brand-origin. Marketers should be aware of this association. Originality/value This research tests the multidimensional aspect of brand image structure and effect of COO information on brand image structure. Results show that COO information affects both the degree of fragmentation of brand image as well as its composition. Keywords Brand awareness, Brand image, Brand management, Country of origin, Japan Paper type Research paper

COO and brand image

139

Received May 2007 Revised September 2007 Accepted September 2007

Introduction Brand image research has long been recognized as one of the central area of the marketing research field not only because it serves as a foundation for tactical marketing-mix issues but also because it plays an integral role in building long-term brand equity (Keller, 1993). Alternately, the globalization has resulted in the proliferation of hybrid products (Czepiec and Cosmos, 1983; Johanson and Nebenzahl, 1986). Hybrid products are products that involve a local manufacturer but carry a foreign brand or locally branded but made in a foreign country (Czepiec and Cosmos, 1983). Hence, many products are experiencing a lack of congruency between the brandorigin (country where the brand is perceived to belong by its target consumers) and the country of origin (COO) labeled on the product. This research studies the effect of different COO labels on brand image perception and brand image structure of two brands with different level of reputation among Japanese consumers. Background Decision making is painful (Pfister, 2003). It requires effortful processing of available information to reach a suitable judgment. Thus, consumers may rely on inferences to make a choice. Huber and McCann (1982) have shown that inferences can affect how

Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistics Vol. 20 No. 2, 2008 pp. 139-155 # Emerald Group Publishing Limited 1355-5855 DOI 10.1108/13555850810864524

APJML 20,2

140

people evaluate products. Inferences come from previous experiences and stored information about the products cues like brand and COO. Fishbein and Ajzen (1975) described three kinds of human beliefs: descriptive, informational, and inferential. Descriptive beliefs derive from direct experience with the product. Informational beliefs are those influenced by outside sources of information such as ads, friends, and so on. Inferential beliefs are those formed by making inferences (correctly or incorrectly) based on past experience as this experience relates to the current stimuli. Images held in consumer mind are one manifestation of these beliefs. Under effect of communication and previous use, consumers form images about products cues that will serves as basis for judgment in future evaluations. Erikson et al. (1984) found that images variables influence consumers multi-attribute evaluation. Images variables are some aspects of the product that is distinct from its physical characteristics but that is nevertheless identified with the product (Erikson et al., 1984). Frequency information (repetitive occurrence of information) affects familiarity (Alba and Marmorstein, 1987) and then affects reputation which in turn, affects images in consumer mind (Holbrook, 1978; Erikson et al., 1984; Alba and Marmorstein, 1987). In line with Thorndikes (1920) conclusion that beliefs recorded on some attributes tend to be caused by a belief recorded on some other attribute, previous researches have revealed significant effect of COO information on brand image (Ahmed and Dastous, 1996; Al-sulaiti and Baker, 1998; Anderson and Chao, 2003; Cervino et al., 2005), and a significant effect of brand reputation on country image (Hui and Zhou, 2003). In 1998, Schlomo and Jaffe proved that there are brand and country images over and above the perceived attributes of products associated with a country or being sold under a specific brand name and that there are two ways interactions among these constructs that change over time. Brand image is defined as a set of perceptions about a brand as reflected by the brand associations held in consumers memory (Hsieh and Lindridge, 2005). Country image is the overall perception consumers form of products from a particular country, based on their prior perceptions of the countrys production and marketing strengths and weaknesses (Roth and Romeo, 1992). Brands as well as countries have different images. With the accelerated movement of globalization (e.g. Levitt, 1983), the emergence of brands across nations revitalizes the age-old issue of which brand strategies, standardization vs customization, should be used in which market. The emergence of global brands gives rise to the issue of whether brand-image appeals affect consumer responses differently in different countries (Hsieh et al., 2004). A firm involved in multiple markets should identify the national characteristics that could affect the success of its brand-image strategies. As one brand may be produced in different countries earning different characteristics, brand images held in consumer mind are likely to be affected differently across countries of production. Ultimately, the power of a brand lies in the minds of consumers or customers (Keller, 2000, p. 157) and that the meaning that customers attached to a brand may be different from that which the firm intends. As image is the fruit of mental configuration and analytical processing, image formation is subject to influence of internal and external factors. Internal factors are the set of consumers personal characteristics (Koubaa, 2006). External factors are the set of product features and country image perceptions (Umbrella brand-image) (Meenghan, 1995). Umbrella brand-image refers to the fact that the brand image perception is under influence of country image perceptions. Country image (from where the brand originate or is manufactured) perceptions is premature to the brand image perception in consumer mind. They come as an umbrella that covers the brand image perception. To some extent, umbrella

brand-image has been described as part of branding strategy at the country level (Meenaghan, 1995). Consumers tend to recall the stored information about the brand and the country in question and then they relate the brand name with the COO to form a brand image and infer the product evaluation (Scott and Keith, 2005). The effect of country image on brand image is moderated by both brand and country reputation (Hui and Zhou, 2003). That is to say the brand image of a well-known brand of a given product produced in a famous country for that product is likely to be affected differently from the brand image of a well-known brand produced in an unknown country and vice-versa. Here another issue is to be considered that of brand-origin. Brand-origin is defined by Takhor and Kohli (1996) as the place, region, or country where brand is perceived to belong by its target consumers. Previous researches revealed strong associations between the brand and the brand-origin (OShaughnessy and OShaughnessy, 2000; Rattif, 1987; Takhor and Kohli, 1996). OShaughnessy and OShaughnessy (2000) affirmed that is important that research shed light on understanding the relative influence of brand-origin associations compared to COO as traditionally manipulated by the Made in cue. When brands come to life, they come in association with their brand-origin. Consumers learn that the brand is born in that country and they may refer to that country in the evaluation of this brand when produced in another country than the brand-origin. Brand image is the reasoned or emotional perceptions consumers attach to a specific brand. It consists of functional and symbolic brand beliefs (Dobni and Zinkhan, 1990). Brand image is made up of brand associations. Brand associations are the category of brands assets and liabilities that include anything linked in memory to a brand (Aaker, 1991). Associations are informational nodes linked to the brand node in memory that contains the meaning of the brand for consumers (Keller et al., 1998). According to the associative network model (Farquhar and Herr, 1993), a persons memory is made up of links and nodes: links represent relationships (positive or negative, weaker or strong), and nodes represent concepts (e.g. brand associations) and objects (e.g. brands). Beliefs have two structural properties, namely, abstraction and complexity. Its must be taken into account in assessment of the structure of brand associations. The role of abstraction in classifying associations finds its evidence in the means-end chain theory, which reflects the memory linkages among attributes (i.e. means), consequences, and attitude (i.e. end) (Gutman, 1982) on the basis of the notion that the product and the consumers sense of self may be hierarchically linked through an interconnected set of cognitive elements along with different levels of abstraction. Several authors defined typologies of brand associations on the basis of the level of abstraction. For instance, Keller (1993) categorizes brand associations as attributes, benefits, and evaluative attitudes of a specific brand along the dimension of level of abstraction. The role of complexity finds its rigueur in Eagly and Chaikens (1993) work. The authors affirmed that the complexity of beliefs associated with an attitude object is typically defined as the dimensionality of the beliefs that a person holds about an attitude object, i.e. the number of dimensions needed to describe the space utilized by the beliefs ascribed to the attitude. To the extend that an economy is market driven, the dimensionality of beliefs could be determined on the basis of their meanings corresponding to the needs, wants, and interests of consumers (Medina and Duffy, 1998). Specifically in satisfying consumers needs, Park et al. (1986) propose three brand dimensions: symbolic benefits, experiential benefits, and functional benefits. Friedman and Lessig (1987) and Kirmani and Zeothaml (1991) classified brand associations into three major categories namely attribute, benefit, and overall brand

COO and brand image

141

APJML 20,2

142

attitude. Attribute refers to the descriptive features that characterize a product or service. Benefit is the personal value that consumers attach to the product or service, and brand overall attitude is consumers overall evaluation of the brand (Wilkie, 1986). Ideally, in consumers memory, brand image perception should encompass all three types of brand associations (Hsieh et al., 2004), hence it is safe to predict a multidimensional structure of brand image. Adding the significant direct effect of COO information on brand image (taken as an overall concept) and the significant moderating effect of brand and country reputations on the impact of COO information on brand image perception; a brand image (taken as a multidimensional concept) is likely to exhibit different structure across brands and across countries of production. Along this research we will try first to study the effect of different countries of origin on brand image perception of two brands with different equities. Then the multidimensional structure of brand image will be checked. Finally, we will try to find how brand image structure evolves across brands and across countries of production. The investigation will be done in Japan. Though, Japan is the brand-origin of many famous brands, it has been a country of investigation for brand image researches for few times only (Usunier, 2006). Literature review The mutual effect of brand name and COO information on consumer perception had been well studied (DAstous and Ahmad, 1999; Hsieh et al., 2004; Kotler and Gertner, 2002; Nebenzahl et al., 2003; Papadopolous, 1993). Most of researches had proven a significant effect of COO information and/or brand name on consumer perception. A significant impact of country image on brand image perception was well supported (DAstous and Ahmad, 1999; Hsieh et al., 2004; Hsieh and Lindridge, 2005; Cervino et al., 2005; Kotler and Gertner, 2002; Stennkamp et al., 2003). In line with these researches, we expect that COO information will have a significant impact on brand image perception. Well-known COO for the product in question will have a positive significant impact while unknown Coo will have significant negative impact. Hui and Zhou (2003) studied the differential effect of the country of manufacture information on product beliefs and attitudes for brands with different levels of equity (high equity, low equity). The finding revealed that the country of manufacturer information does not produce a significant effect on the evaluation of branded products when this information is congruent with the brand origin (i.e. Sony with Japan). However, when the product is manufactured in a country with a less image than the country of the brand origin, country of manufacturer information produces a significant negative effect on product evaluation, and the effect tend to be more devastating for low equity than high equity brands. H1a. COO information will affect significantly brand image perception. H1b. Well-known COO for the product in question will have significant positive effect on brand image perception while unknown COO will have negative impact on brand image perception. H1c. Brand level of reputation will moderate the effect of country of production on brand image.

As concerns brand-origin effects, Takhor and Lavack (2003) declared that brand-origin is one such cue that plays potentially important role in determining a brands image. Samiee et al. (2005) found that consumers classify brands with their COO basing on the brand pronunciation or spelling and its similarity with the brand-origin language.

When the brand is created, it comes out to consumers in association with its brandorigin. Kenny and Aron (2001) investigated the pertinence of culture of origin vs COO and their impacts on consumer brands classifications. Culture of brand origin (COBO) was defined as the set of beliefs, attitudes, references, and inferences that a consumer expresses when hearing, seeing, or reading about a brand. For example, when hearing Volks-vagen fox, consumers refer automatically to the engineering power of Germany even though most of Volks-vagen cars are made in Brazil. Results showed that the COBO had more presence in the mind of consumers and more easily identifiable than the COO. H2. Brand-origin will have a significant effect on brand image perception.

COO and brand image

143

Brand image changes as production is outsourced. Cervino et al. (2005) found a significant impact of product country image on brand performance. Hsieh and Lindridge (2005) argued that brand image structure differs across countries. Nebenzahl and Jaffe (1997) argued that the perceived value of the product is weighted average of its perceived brand and Made in country values. This value can be higher or lower than the value of the brand without reference to the Made in country. Brand image is found to be multidimensional (Hsieh, 2002; Hsieh and Lindridge, 2005). Hsieh and Lindridge (2005) found that dimensions of a brand image differ across countries of production. Brand-image is a set of perceptions about a brand as reflected by the brand associations held in the consumers memory. Aaker (1991) defines brand associations as the category of brands assets and liabilities that include anything linked in memory to a brand. Associations are informational nodes linked to the brand node in memory that contains the meaning of the brand for consumers (Keller et al., 1998). Giving the fact that a persons memory is made of nodes and links (Farquhar and Herr, 1993) and has then a matricidal shape, we expect that brand image will have different facets (dimensions) in consumers mind. A study across 20 countries by Hsieh (2002) supports a multidimensional brand image structure. Revealed dimensions transfer consumers sensory, utilitarian, and symbolic and economic needs about a brand. Low and Lamb (2000) found consistent with the idea that consumers have more developed memory structures for more familiar brands that well-known brands tend to exhibit multidimensional brand associations. Hence we predict a multidimensional aspect of brand image. H3. Brand image is multi-dimensional rather than an overall concept.

Because brands as overall concepts have different perceptions among consumers across brands and across countries of production, and consumers are likely to be different as they have different backgrounds and are under different circumstances of consumption; we expect that brand image structure (the set of dimensions that will define each brand image) will differ across brands and across countries of production. Hsieh (2002) through a study in 70 regions across 20 countries and along 53 brands founds that brands exhibit different structures across countries of production and across brands. Low and Lamb (2000) revealed different multidimensional brand associations across brands and across product categories. H4. Brand images structures will be significantly different across brands and across countries of productions.

APJML 20,2

144

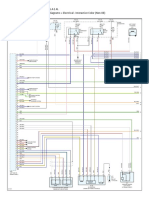

Method A factorial research design was used as shown in Table I. Investigated products were electronics (digital camera and plasma TV). Two brands originating from Japan, but with different levels of reputation, were studied namely, Sony and Sanyo. Respondents were provided with information as concerns warranty (one year for camera and three years for TV) and after service (reparation and components costs), which corresponds to the real case of marketed cameras and Plasma TV in Japan. In total ten combinations were drawn: eight brand-country combinations and one combination for each brand where no COO is mentioned. This method ensures that country-images are not confounded by the respective brand images (Nebenzahl and Jaffe, 1997), since well known brands (e.g. Sony) are associated with their respective home countries (Sauer et al., 1991); and enables us to test for brand/brand-origin interaction. Each combination (Xij) was subject to an evaluation on a five-point scale (from 1: totally disagree to five: totally agree) along 15 criteria. The questionnaire contains scale measuring consumers attitudes toward Sony and Sanyo as produced in the four studied countries and when no COO is mentioned. The scale encloses 15 items measuring the product quality, reliability, durability, style, market presence, etc. This scale was used before (Parameswaran and Yaprak, 1987) and exhibited a high reliability. Respondents were asked in the end of the questionnaire to deliver some personal information related to the gender, age, occupation and yearly spending for electronics. 200 residents (students, employees, and housewives) from an urban area in the city of Kobe (Japan) participated in this investigation. Investigation was done by the researcher. Respondents were selected from a database of an electronics retailer that uses member card system and operates in Kobe area. The selection was based on the frequency of buying electronics from one of the retailers stores, age, and gender. The sample was distributed equally between males (100) and females (100). All the selected respondents were aged between 22 and 59 years. Old people (aged more than 60 years) were not selected because they represent a very low percentage of card holders. In total, 129 questionnaires were available for statistical use. The answers rate is 64.5 per cent. 73 were males and 56 were females. Age in average is 42 years. Yearly spending for electronics is around 2,100USD. Respondents exhibited a high familiarity with both brands. An examination of scales reliability reveals an alpha of Cronbach superior to 0.8 for this scale across all brands. Comparison of overall images between brands as production is outsourced was based on comparing the means values of respondents scores along 15 items, by respondent. Table II summarizes those means by brand and by brand-COO match. ANOVA reveals significant differences at p < 0.00 (F 17.08) across the two brands as production is outsourced. Table III presents ANOVA results.

Xij Country Japan USA China Indonesia Brand image without reference to country Xi Sony X11 X12 X13 X14 X1 Sanyo X21 X22 X23 X24 X2

Table I. Factorial design

Going to explore differences among each pair of brand images, we proceed by a serial of t-tests. Then a joint space mapping was derived from factorizing all brands images together to see clearly how outsourcing activities affect brands images. In a third stage we proceed by an exploratory factor analysis (EFC) to extract the dimensions that define each brand image as production is outsourced. Statistically, the determinants of the dimensionality and the strength of brand associations are equivalent to the criteria of extracting factors from a factor analysis, namely discriminant validity, reliability, and convergent validity. Discriminant validity is the degree to which extracted factors (e.g. image dimensions) are discriminated from one another, reliability is the extend to which the multiple correlations in the observed variables (e.g. Brand associations) are accounted for by the factor, and convergent validity is measured by the value of the correlation coefficients between observed variables and their corresponding factors (e.g. image dimension). Because our objective is to see how moving across countries of production and across brands may affect brand image structure, we factorize each brand image separately. Then, EFC was followed by a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). CFA provides a powerful tool for examining the reliability and the validity of image dimensionality (Hsieh, 2002). CFA was carried out using data collected from a sample of 180 Japanese students. Students were asked to fill the same questionnaire. One hundred and fifty-two questionnaires were available for statistical use. Age in average of the respondents was 21 years. Respondents expressed high familiarity with brands, the four countries, and the investigated products. Findings Overall Sony and Sanyo images are higher when the product is made in Japan and start to decrease continuously when the production is shifted to USA, China, and Indonesia. Differences between Sony-Japan/Sony-China and Sony-Japan/Sony-Indonesia are significant at p < 0.05. However, difference between Sony-Japan/Sony-USA was not significant. It was exactly the same as concerns Sanyo. Thus H1a is confirmed. Differences between Sony/Sony-USA, Sony/Sony-China, and Sony/Sony-Indonesia were significant at p < 0.00 except for Sony/Sony-USA with p < 0.1. The image of Sony when no COO is mentioned had been deteriorated when USA, China, and

COO and brand image

145

Country Japan USA China Indonesia Without reference to any country

Sony image 3.8 3.44 3.03 2.85 3.69

Sanyo image 3.37 3.3 2.86 2.72 3.23

Table II.

Means of joint brandcountry ratings

Sum of squares Between groups Within groups Total 17.664 16.082 33.746

df 9 140 149

Mean square 1.963 0.115

F 17.086

Significance 0.000

Table III.

ANOVA results

APJML 20,2

146

Indonesia were mentioned as countries of origin. The highest deterioration was with Sony-Indonesia (0.84) followed by Sony-China (0.66) and finally Sony-USA (0.25). Differences between Sanyo/Sanyo-China and Sanyo/Sanyo-Indonesia were significant at p < 0.00. Sanyo image when no COO is mentioned had been deteriorated when produced in China and Indonesia. The highest deterioration was with Sanyo-Indonesia (0.51) followed by Sanyo-China (0.47). However, it keeps almost the same image when produced in Japan and USA. Sony and Sanyo were affected differently across the four countries of production. Sony expressed more erosion than Sanyo when moving from a well-known country to a less famous one. H1b and H1c are confirmed. Difference between Sanyo/Sanyo-Japan and Sanyo/Sanyo-USA were not significant. Similarly, no significant difference was revealed between Sony/Sony-Japan. Thus H2 is confirmed. Figure 1 summarizes the means in Table II and shows clearly how brand image differ across brands and across countries of production. Joint space mapping of brand-COO In a second stage, going to gain on accuracy in assessing how exactly outsourcing activities affect brand image, we proceed, as recommended by Heslop and Papadopoulos (1993), by factorizing all brands images taken together. Following PCA (principal components analysis using Varimax rotation) results, we provide a joint space mapping that enables readers to see more clearly what is affected in each brand image as produced in a given country (Figure 2). PCA revealed two factors with 94.64 per cent of explained variance. The first factor contributes for 84.8 per cent and the second factor for 9.84 per cent (Table IV). All communalities are quite high. The first factor represents the product value (highly correlated items are: made with meticulous, good performers, long lasting, easy to repair, high quality). The second factor transfers product style and market presence. An interactive chart was generated from the two factors. Sony image when produced in Japan has gained in product value and lost in market presence and style comparing to its image when no COO is mentioned. For Sanyo-Japan, it gained on both product value and market presence. Sony-USA is less perceived on product value and more perceived on market presence than Sony and Sony-Japan. It is almost same for Sanyo-USA but with a larger difference. Sony-China, Sony-Indonesia, Sanyo-China and Sanyo-Indonesia are less perceived on both product value and style and market presence, respectively, than Sony, Sony-Japan, and Sony-USA; and Sanyo, Sanyo-Japan, and Sanyo-USA. When

Figure 1. Brand images scores across country of production

COO and brand image

147

Figure 2.

Joint space map of brand-image across country of production

Items Inexpensive Highly technical Made with meticulous Innovative Luxurious Sold worldwide Good looking Good performers Heavily advertised in Japan Do not need frequent repairs Marketed in a wide range of styles Long lasting Informative in their ads Easy to repair in Japan High quality consumers items Explained variance

First factor 0.718 0.637 0.892 0.566 0.478 0.095 0.499 0.858 0.857 0.911 0.417 0.865 0.733 0.952 0.823 84.8%

Second factor 0.611 0.759 0.405 0.796 0.859 0.930 0.847 0.495 0.411 0.394 0.882 0.445 0.665 0.139 0.561 9.84%

Communality 0.890 0.983 0.959 0.954 0.967 0.874 0.967 0.981 0.902 0.952 0.951 0.946 0.953 0.927 0.992

Table IV.

Factor analysis of all brands images

production was shifted to China, product value of Sony was strongly affected and the products market presence and style was moderately affected. It was almost same effect for Sony-Indonesia. In case of Sanyo-China, product value was deteriorated; however, it gained on market presence and style. Sanyo-Indonesia image was strongly deteriorated on both factors comparing to its image when no country is mentioned.

APJML 20,2

148

Exploratory factor analysis To assess differences among brand-images structure across countries of production, first an EFC was run for each brand-image separately, then a CFA was run to test the goodness of fit of the revealed structures. EFC reveals a bi-dimensional image for Sony when no COO is mentioned. The first dimension (32.4 per cent) transfers product quality and the second one (11.61 per cent) transfers product durability. Alternately a tri-dimensional image was revealed for Sanyo. The first factor (42.50 per cent) emphasizes product durability. The second factor (10.62 per cent) emphasizes product show (luxurious, good looking). The third dimension (8.29 per cent) focus on product communication and serviceability in Japan. Sony-Japan was tri-dimensional. The first factor (29.96 per cent) emphasizes product durability. The second (13.16 per cent) transfers product show and communication. The third (9.74 per cent) emphasizes the product know-how. However, it was a bi-dimensional structure for Sanyo-Japan. The first dimension (45.34 per cent) emphasizes product high quality. The second one (8.86 per cent) transfer product-show (good looking) and international market presence (sold worldwide). Sony-China was tri-dimensional. The first dimension (37.6 per cent) emphasizes product durability. The second (12.75 per cent) emphasizes product availability and the last one (8.66 per cent) transfers innovation and serviceability. Alternately a bi-dimensional structure for Sanyo-China image was revealed. The first one (44.41 per cent) emphasizes product quality and durability. The second one (9.23 per cent) emphasizes product-show. A bi-dimensional image was revealed for Sony-Indonesia. The first factor (44.04 per cent) emphasizes product quality and know-how. The second one (9.6 per cent) focuses on communication and market presence. Similarly, a bi-dimensional image for Sanyo-Indonesia was revealed. The first dimension (50.59 per cent) emphasizes product value. The second one (8.02 per cent) emphasizes product communication and market presence. Sony-USA was bi-dimensional. The first dimension (35.13 per cent) emphasizes product durability. The second one (13.19 per cent) emphasizes product style and communication. Differently EFA revealed a tri-dimensional structure for Sanyo-USA image. The first dimension (39.14 per cent) emphasizes product communication. The second dimension (11.05 per cent) pictorials product durability and higher quality. The last one (8.25 per cent) illustrates product higher technicality. Still in an exploratory phase, it is clear that both Sony and Sanyo had different image structures. Similarly, Sony and Sanyo had had different image structures as their productions were shifted from one country to another. Although, EFA allows us to support, but with a considerable risk, our third hypothesis, we think it is rigorous to test the stability of the above structures in order to confirm Sony and Sanyo images. Thus we propose to proceed by a CFA using a structural equation modeling. Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) A structural equation modeling using AMOS 4 served as a basis for our CFA. Starting from EFA results, a model was drawn for each combination. Table V illustrates the goodness of fit of each model in term of Chi-square, NFI, CFI, CMIN/DF, RMSEA, and HOELTER coefficients.

Eight images structures were supported (Sony, Sony-Japan, Sony-China, SonyUSA, Sanyo, Sanyo-China, Sanyo-Indonesia, and Sanyo-USA) and two were rejected (Sony-Indonesia and Sanyo-Japan). Sony, Sony-China, Sanyo-China, SanyoIndonesia, and Sanyo-USA images structures are strongly supported. All the latter structures enjoyed reliable indices in term of NFI (so near to one), CFI (so near to one), RMSEA (between 0.05 and 0.08), and Hoelter (superior to 200). As concerns Sony-Japan, Sony-USA, and Sanyo image structures; goodness of fit indices are not so far to be reliable for a fitted model. Although, it is safer to rely on a pattern of indices to judge the fitness of a model, we can experience many studies were researchers rely just on one or two indices. The judgment is, to some extend, subjective. NFI and CFI indices are not so far from one. Hoelter indices were less than 200 which highlight a problem with the sample size. In the case of SonyIndonesia and Sanyo-Japan, it is unsafe to admit the EFA structure. The goodness of fit indices are far to be of a fitted model. Therefore, Sony-Indonesia and SanyoJapan image structures are rejected. Moreover, one correlation was needed in the case of Sanyo to reach a good fit of its image structure. It was between the items 10 (do not need frequent repairs) and 12 (long lasting). As James Arbuckle, the author of AMOS mentioned in the user guide of the program, when a correlation is needed to enhance the models goodness of fit, researchers has to provide explanations that support these correlations; we interpret the correlation between do not need frequent repairs and long lasting by the fact that products that do not need frequent repairs are likely to be of good quality and strong enough to last for a long period. Based on these results, we can affirm with more confidence that the images of Sony, Sony-Japan, Sony-China, Sony-USA, Sanyo-China, Sanyo-Indonesia, and Sanyo-USA have numerous facets in consumers mind and tend to have a multidimensional structure. These structures differ between each others. Differences are detected along the same brand across countries of production, and across brands themselves. Sony, Sony-USA, Sanyo-China, Sanyo-Indonesia are bi-dimensional. However, Sony-Japan, Sony-China, Sanyo, and Sanyo-USA are tri-dimensional. Sony when no COO is mentioned reveals a bi-dimensional structure taking quality as the first dimension and product durability as the second one. Sanyo image was tridimensional taking durability as the most important dimension followed by product show and finally product communication. Looking at Sony-Japan, Sony-China, SonyUSA, Sanyo-China, Sanyo-USA, and Sanyo-Indonesia, we can recognize differences

COO and brand image

149

Chi-square Sony Sony-Japan Sony-China Sony-Indonesia Sony-USA Sanyo Sanyo-Japan Sanyo-China Sanyo-Indonesia Sanyo-USA 9.032 8.456 18.02 50.68 21.32 23.72 47.64 9.62 6.982 14.15

CMIN/DF 1.644 1.986 1.238 5.243 2.145 1.790 3.830 1.293 1.878 1.283

NFI 0.993 0.993 0.992 0.983 0.994 0.991 0.976 0.996 0.992 0.989

CFI 0.996 0.990 0.995 0.977 0.991 0.989 0.981 0.992 0.996 0.996

RMSEA 0.078 0.091 0.046 0.165 0.096 0.092 0.132 0.056 0.079 0.049

HOELTER 242 185 216 48 142 187 79 213 245 231

Table V.

Coefficients summarizing each models goodness of fit

APJML 20,2

150

between the two brands images structures, when they are not labeled any COO, when they are labeled the same COO, and when they are labeled different COO. Differences marked the degree of fragmentation (number of dimensions), the composition of each image (what factors), and the impacts weight of each dimension. The loadings of all items on their respective factors (dimensions) are significant for the eight confirmed image structures. Thats to say that the selected items through the EFA contribute significantly in forming their respective dimension. Therefore, our third and fourth hypotheses are confirmed. Brand image structure is multidimensional (H3) and it was affected differently across country of production and across brands (H4). Interpretations and marketing implications First, alienated with past researches, COO had had a significant impact on brand image perception. Both highly reputed brands and less reputed brands are affected but differently. High reputed brands experience more erosion when production is shifted to others countries than the brand-origin. Less reputed brands may benefit from their production in their brand-origin if the brand-origin is well perceived as a producer of the product in question. It was the case of Sanyo-Japan that was highly perceived than a Sony-China or Sony-Indonesia. Consistent with Thakor and Kohli (1996), the effect of brand-origin on consumer perception appears to be significant. Images of Sony and Sanyo when no COO is mentioned and their images when produced in Japan were almost same; however, their images when produced in USA, China, and Indonesia were significantly different (except for Sanyo-Sanyo USA: not significant). Consumers, automatically, classify Sony and Sanyo as Japanese products, when no COO is given. Their evaluations of Sony and Sanyo when produced in others countries than Japan will be with reference to a Sony-Japan or Sanyo-Japan. While globalization process speeds up outsourcing activities and squeezes investment and trade barriers (macro level), companies are still facing cultural and consumer behavior barriers (micro level). Japanese consumers still perceive a Sony or Sanyo made in China, Indonesia, or even USA as product inferior to a Sony-Japan or Sanyo-Japan. Erosion, when passing from Japan to China or Indonesia, is to some extend expected and found in past researches. However, erosion of Sony image when passing from Japan to USA seems to be due to a strong brand-origin effect. DAstous and Ahmad (1999) found similarly, that the high class BMW image was eroded when production was shifted from Germany to USA. To some extend, German and Japanese have a common cultural characteristic, namely, a relatively developed ethnocentrism, which influences the way they perceive German, respectively, Japanese brands as produced in their home country or abroad. A second interesting point is that the above phenomenon (erosion of Sony-USA) did not happen with Sanyo. Similarly, in line with DAstous and Ahmad (1999), the brand tightness to the brand-origin may serves as reason. DAstous and Ahmad (1999) found that only the high class BMW that was affected when produced in USA comparing to its image when produced in Germany. Others brands were not affected by such delocalization. It was almost same in this research; indeed, Sony is more in tie with Japan than Sanyo. Investors should put into consideration the brand-origin, brand reputation, and the link brand/brandorigin when thinking about a delocalization. It is wise sometimes to hide the COO information if a negative impact on brand image is expected and benefit from

the effect of brand-origin on brand perception (consumers assumption that the brand is produced in the brand-origin if no COO is mentioned). Moreover, marketing actions should be customized across brands, across countries, and across brand-COO combinations. Brand image is multidimensional rather than an overall concept. EFA and CFA proved the multidimensional aspect of brand image structure. Multidimensionality implies a need among consumers for multiple information as concerns the brand. They may refer to several dimensions (quality, style, durability, etc) to fix a final judgment. One brand may encompass all these dimensions in consumers minds. Marketers should provide consumers with the maximum of information as concerns the brand in order to satisfy their need for information along different dimensions. Brands images structures appear to be different across brands and across countries of production. Knowing the dimensions of brand-country image enables marketers to determine a more definitive marketing strategy. Brand image structure changes along different COO. This change is more intense with less reputed brands. Sony image, along the four studied COO, had had durability as the dominant dimension, and communication as the second dimension. Minor differences were revealed with Sony-Indonesia where consumers express a need for market presence, with Sony-China where consumers express a need for product availability, and with Sony-USA where they express a need for product style. However, these differences were revealed along the second or the third dimension. The latter dimensions explain a relatively low variance compared to the first dimension. As concerns Sanyo images, they experience major differences across countries of production. Durability was the dominant dimension with Sanyo. However, it was quality and durability with Sanyo-China, product value with Sanyo-Indonesia, and product communication with Sanyo-USA. Changes were remarkable too along the second most important dimension. The conjoint effect of country image and brand reputation had had an influence on brand image structure. Product development and advertisement strategies should be alienated to these influences. Marketing strategies for bi-national products should encompass the matricidal impact of brands level of reputation and country image on brand image structure held in consumers minds and then on their overall judgment. Conclusions and future research COO did influence consumers overall perception of brands. Influences were different across highly reputed brands and less reputed brands. Brand-origin is found to be of significant impact on brand image perception. The effect of country image on brand image is so strong. It may overcome the power of well-known brands in shaping brand image in consumer mind. Marketers should customize their actions across brands and across countries of production. Both, brands level of reputation and country image impacts should be taken into account when elaborating marketing operations for binational products. Brand image has several facets in consumers imagination. It is found to be multidimensional. Dimensions differ across country of production and across brands. Marketers should look on what dimension(s) to provide for consumers for each brand produced in a specific country. As any research, this research has its limitation. First it dealt with one type of product (electronics). Other products should be investigated. Future researches may spend effort in investigating less or more complex products. Second as it deal with an aspect of consumer behavior, it is interesting to incorporate some cultural (e.g. collectivism/individualism) and personal (e.g. need for

COO and brand image

151

APJML 20,2

affect/need for cognition) characteristics and test their effect on brand image along different COO.

References Aaker, D.A. (1991), Managing Brand Equity, Free Press, New York, NY.

152

Ahmed, S.A. and dAstous, A. (1996), Country of origin and brand effects: a multi-dimensional and multi-attribute study, Journal of International Consumer Marketing, Vol. 9 No. 2, p. 93. Alba, J.W. and Marmorstein, H. (1987), The effects of frequency knowledge on consumer decision making, Journal of Consumer Research, Vol. 14 No. 1, pp. 14-25. Al-sulaiti, K.I. and Baker, M.J. (1998), Country of origin effects: a literature review, Marketing Intelligence Review, Vol. 16 No. 3, pp. 150-99. Anderson, P. H. and Chao, P. (2003), Country of origin effects in global industrial sourcing: toward an integrated framework, Management International Review, Vol. 43 No. 4, pp. 339-60. Cervino, J., Sanchez, J. and Cubillo, J.M. (2005), Made in effect, competitive marketing strategy and brand performance: an empirical analysis for Spanish brands, Journal of American Academy of Business, Vol. 6 No. 2, pp. 237-43. Czepiec, H. and Cosmas, S. (1983), Exploring the meaning of made in: a look at national stereotypes, product evaluations, and hybrids, paper presented at Annual Meeting of the Academy of International Business, San Francisco, CA. DAstous, A. and Ahmad, A.S. (1999), The importance of the country images in the formation of the consumer product perceptions, International Marketing Review, Vol. 16 No. 2, pp. 108-125. Dobni, D. and Zinkhan, G. M. (1990), In search of brand image: a foundation analysis, in Low, G. S. and Lamb, C. W. (2000), the measurement and dimensionality of brand associations, The Journal of Product and Brand Management, Vol. 9 No. 6, pp. 350-62. Eagly, A.H. and Chaiken, S. (1993), The Psychology of Attitudes, Harcourt Brace Javanovich, Fort Worth, TX. Erickson, G.A., Johansson, J.K. and Chao, P. (1984), Image variables in multi-attribute product evaluations: country of origin effects, Journal of Consumer Research, Vol. 11 No. 2, pp. 694-9. Farquhar, P.H. and Herr, P.M. (1993), The dual structure of brand associations in Hsieh, M.H. (2002), Identifying brand image dimensionality and measuring the degree of brand globalization: a cross-national study, Journal of International Marketing, Vol. 10 No. 2, pp. 46-67. Friedman, R. and Lessig, V.P. (1986), A framework of psychological meaning of products, Advances of consumer research, Vol. 13, pp. 338-42. Fishbein, M. and Ajzen, I. (1975), Belief, Attitude, Intention and Behavior: An Introduction to Theory and Research, Addison Wisley, Reading, MA. Gutman, J. (1982), A means-end chain model based on consumer categorization processes, Journal of Marketing, Vol. 46, No. 2, pp. 60-72. Heslop, L. and Papadopoulos, C. (1993), But who knows where and when: reflections on the images of countries and their products in Nenbenzahl, I. and Jaffe, D.E. (1997), Measuring the joint effect of brand and country image in consumer evaluation of global products, Journal of Marketing Practice: Applied Marketing Science, Vol. 3 No. 3, pp. 190-207.

Holbrook, M.B. (1978), Beyond attitude structure: toward the informational determinants of attitude in Erickson, G.A., Johansson, J.K. and Chao, P. (1984), Image variables in multiattribute product evaluations: country of origin effects, Journal of Consumer Research, Vol. 11 No. 2, pp. 694-9. Hsieh, M.H. (2002), Identifying brand image dimensionality and measuring the degree of brand globalization: a cross-national study, Journal of International Marketing, Vol. 10 No. 2, pp. 46-67. Hsieh, M.H. and Lindridge, A. (2005), Universal appeals with local specifications, The Journal of Product and Brand Management, Vol. 14 No. 1, pp. 14-28. Hsieh, M.H., Pan, S.L. and Setiono, R. (2004), Product-, corporate-, and country-image dimensions and purchase behavior: a multicountry analysis, Academy of Marketing Science, Vol. 32 No. 3, pp. 251-70. Huber, J. and McCann, J. (1982), The impact of inferential beliefs on product evaluations, Journal of Marketing Research, Vol. 19, pp. 324-33. Hui, K.M. and Zhou, L. (2003), Country of manufacture effects for known brands, European Journal of Marketing, Vol. 37 Nos. 1-2, pp. 133-53. Johansson, J.K. and Nebenzahl, I.D. (1986), Multinational production: effect on brand value, Journal of International Business Studies, Vol. 17 No. 3, pp. 101-27. Keller, K.L. (1993), Conceptualizing, measuring, and managing consumer based brand equity, Journal of Marketing, Vol. 57, January, pp.1-22. Keller, K. L. (2000), The brand report card, Harvard Business Review, Vol. 78, pp. 147-57. Keller, K.L., Heckler, S.E. and Houston, M.J. (1998), The effects of brand name suggestiveness on advertising recall, Journal of Marketing, Vol. 62, January, pp. 48-57. Kenny, L. and Aron, O. (2001), Consumer brand classifications: an assessment of culture of origin versus country of origin, Journal of Product and Brand Management, Vol. 10 No. 2, pp. 120-36. Kirmani, A. and Zeothaml, V. (1991), Advertising, perceived quality, and brand image in Aaker, D. and Alexander, L.B. (Eds), Brand Equity and Advertising: Advertisings Role in Building Strong Brands, Laurence Erlbaum Associates, Hillsdale, NJ, pp. 143-61. Kotler, P. and Gertner, D. (2002), Country as brand, product, and beyond: a place marketing and brand management perspective, Journal of Brand Management, London, Vol. 9 Nos. 4-5, pp. 249-62. Koubaa, Y. (2006), COO: who uses it, when and how it is used, paper presented at the 9th Conference on Global Business and Technologies Association, Taiwan. Levitt, T. (1983), The globalization of markets, Harvard Business Review, Vol. 61, May-June, pp. 263-70. Low, S.G. and Lamb, W.C., Jr. (2000), The measurement and dimensionality of brand associations, The Journal of Product and Brand Management, Vol. 9 No. 6, pp. 350. Medina, J.F. and Duffy, M.F. (1998), Standardization vs. globalization: a new perspective of brand strategies, Journal of Product and Brand Management, Vol. 7 No. 3, pp. 223-43. Meenaghan, T. (1995), The role of advertising in brand image development, Journal of Product and Brand Management, Vol. 4 No. 4, pp. 23-34. Nenbenzahl, I and Jaffe, D.E. (1997), Measuring the joint effect of brand and country image in consumer evaluation of global products, Journal of Marketing Practice: Applied Marketing Science, Vol. 3 No. 3, pp. 190-207.

COO and brand image

153

APJML 20,2

154

Nebenzahl, D.I., Eugene, D.J. and Usinier, J.C. (2003), Personifying country of origin research, Management International Review, Vol. 43, p. 383. OShaughnessy, J. and OShaughnessy, N.J. (2000), Treating the nation as a brand: some neglected issues in Thakor, M.V. and Lavack, M.A. (2003), Effect of perceived brand origin associations on consumer perceptions of quality, The Journal of Product and Brand Management, Vol. 12 Nos. 6-7, p. 394. Papadopolous, N. (1993), What product country images are and are not in Al-sulaiti, K.I. and Baker, M.J. (1998), Country of origin effects: a literature review, Marketing Intelligence Review, Vol. 16 No. 3, pp. 150-99. Parameswaran, R. and Yaprak, A. (1987), A cross-national comparison of consumer research measures, Journal of International Business Studies, Spring, pp. 35-49. Park, C.W., Jaworski, J.B. and Maclnnis, J.D. (1986), Strategic brand concept-image management, Journal of Marketing, Vol. 50, October, pp. 135-45. Pfister, R.H. (2003), Decision making is painful- we knew it all along, Journal of Behavioral Decision Making, Vol. 16 No. 1, p. 73. Ratliff, R. (1989), Wheres that new car made? Many Americans dont know, in Thakor, M.V. and Anne, M.L. (2003), effect of perceived brand origin associations on consumer perceptions of quality, The Journal of Product and Brand Management, Vol. 12 No. 6/7, p. 394. Roth, M.S and Romeo, J.B (1992), Matching product category and country image perceptions: a framework for managing country of origin effects, Journal of International Business studies, Vol. 23 No. 3, pp. 477-97. Samiee, S., Shimp, T.A. and Sharma, S. (2005), Brand origin recognition accuracy: its antecedents and consumers cognitive limitations, Journal of International Business Studies, Vol. 36, pp. 379-97. Sauer, P.L., Young, M.A. and Unnava, H.R. (1991), An experimental investigation of the processes behind the country of origin effect, Journal of International Consumer Marketing, Vol. 3 No. 2, pp. 29-59. Scott, S.L. and Keith, F.J. (2005), The automatic country of origin effects on brand judgment, Journal of Advertising, Vol. 34, pp. 87-98. Steenkamp, E.M., Jan-Benedict., Rajeev, B. and Dana, L.A (2003), How perceived brand globalness creates brand value, Journal of International Business Studies, Vol. 34 No. 1, pp. 53-66. Thakor, M.V. and Kohli, C.S. (1996), Brand origin: conceptualization and review, Journal of Consumer Marketing, Vol. 13 No. 3, pp. 27-42. Thakor, M.V. and Lavack, M.A. (2003), Effect of perceived brand origin associations on consumer perceptions of quality, The Journal of Product and Brand Management, Vol. 12 Nos. 6-7, p. 394. Thorndike, E.L. (1920), A consistent error in psychological ratings, Journal of Applied Psychology, Vol. 4, pp. 25-9. Usunier, J.C. (2006), Relevance in business research: the case of country of origin research in marketing, European Management Review, Vol. 3, pp. 60-75. Wilkie, W. (1986), Consumer Behavior, John Wiley, New York, NY. Further reading Kotler, P., Haider, D.H. and Rein, I. (1993), Marketing Places: Attracting Investment, Industry, and Tourism to Cities, States, and Nations, Free Press in Kotler, P. and Gertner, D. (2002), Country as brand, product, and beyond: a place marketing and brand management perspective, Journal of Brand Management, Vol. 9 Nos. 4-5, pp. 249-62.

Miyasaki, A.D., Grewal, D. and Goodstein, R.C. (2005), Re-inquiries: the effect on multiple extrinsic cues on quality perceptions: a matter of consistency, Journal of Consumer Research, Vol. 32 No. 1, pp. 146-53. Papadopolous, N., Heslop, L., Graby, F. and Avlonitis, G. (1987), Does country of origin matter? Some findings from a cross-cultural study of consumer views about foreign products in Al-sulaiti, K.I. and Baker, M.J. (1998), Country of origin effects: a literature review, Marketing Intelligence Review, Vol. 16 No. 3, pp. 150-99. Shlomo, I.L. and Jaffe, E.D. (1998), A dynamic approach to country of origin effect, European Journal of Marketing, Vol. 32 Nos. 1-2, pp. 61-78. Corresponding author Yamen Koubaa can be contacted at: Kubaa_85060020@red.umds.ac.jp or koubaa_yam@yahoo.fr

COO and brand image

155

To purchase reprints of this article please e-mail: reprints@emeraldinsight.com Or visit our web site for further details: www.emeraldinsight.com/reprints

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (587)

- AFG Country MetaData en EXCELDocument282 pagesAFG Country MetaData en EXCELHammna AshrafPas encore d'évaluation

- Underline The Describing WordsDocument3 pagesUnderline The Describing WordsHammna AshrafPas encore d'évaluation

- Human Resource Management ProcessDocument44 pagesHuman Resource Management ProcessHammna Ashraf100% (1)

- SCMDocument78 pagesSCMHammna AshrafPas encore d'évaluation

- Tarbiya ThemeDocument1 pageTarbiya ThemeHammna AshrafPas encore d'évaluation

- Preposition 2Document3 pagesPreposition 2Hammna AshrafPas encore d'évaluation

- Backup of Ahtram (1383)Document19 pagesBackup of Ahtram (1383)Hammna AshrafPas encore d'évaluation

- b7202491-156d-442c-ab9e-9d17b60586dbDocument9 pagesb7202491-156d-442c-ab9e-9d17b60586dbHammna AshrafPas encore d'évaluation

- BanksDocument5 pagesBanksHammna AshrafPas encore d'évaluation

- Addition Within 20 WP G1Document5 pagesAddition Within 20 WP G1Hammna AshrafPas encore d'évaluation

- Transfer Function of Rotational Mechanical System with GearingDocument21 pagesTransfer Function of Rotational Mechanical System with GearingHammna AshrafPas encore d'évaluation

- Underline The Describing WordsDocument8 pagesUnderline The Describing WordsHammna Ashraf100% (2)

- No. Q No. Page No. 1 8-2 390 2 8-4 390 3 8-5 391 4 8A-2 393Document2 pagesNo. Q No. Page No. 1 8-2 390 2 8-4 390 3 8-5 391 4 8A-2 393Hammna AshrafPas encore d'évaluation

- Preposition 2Document3 pagesPreposition 2Hammna AshrafPas encore d'évaluation

- G2 Multiplication TWSDocument2 pagesG2 Multiplication TWSHammna AshrafPas encore d'évaluation

- Class 3 Non Hifz (Comp) Academic Syllabus 2018-19Document3 pagesClass 3 Non Hifz (Comp) Academic Syllabus 2018-19Hammna AshrafPas encore d'évaluation

- Motivation PDFDocument6 pagesMotivation PDFCate MasilunganPas encore d'évaluation

- Haalim Episode 21Document92 pagesHaalim Episode 21Hammna Ashraf50% (2)

- Ankhon Se Meri Dekho - Faiza IftikharDocument35 pagesAnkhon Se Meri Dekho - Faiza IftikharHammna AshrafPas encore d'évaluation

- Network PlanningDocument24 pagesNetwork PlanningMITHUNLALUSPas encore d'évaluation

- PrefaceDocument1 pagePrefaceHammna AshrafPas encore d'évaluation

- YehJoIkSubahKaSitaraHewww.paksociety.comDocument48 pagesYehJoIkSubahKaSitaraHewww.paksociety.comHammna AshrafPas encore d'évaluation

- Fault Detection and Correction of Distributed Antenna SystemDocument20 pagesFault Detection and Correction of Distributed Antenna SystemHammna AshrafPas encore d'évaluation

- Introduction To ChemistryDocument3 pagesIntroduction To ChemistryHammna Ashraf100% (1)

- Traffic Engineering": CSE 222A: Computer Communication Networks Alex C. SnoerenDocument40 pagesTraffic Engineering": CSE 222A: Computer Communication Networks Alex C. SnoerenHammna AshrafPas encore d'évaluation

- 9676 w06 ErDocument7 pages9676 w06 ErHammna AshrafPas encore d'évaluation

- Intrinsic and Exintric Motivation 25,52-64Document14 pagesIntrinsic and Exintric Motivation 25,52-64Daniel Thorup100% (1)

- 10 Basic Drives and Motives PDFDocument36 pages10 Basic Drives and Motives PDFHammna AshrafPas encore d'évaluation

- 10 Basic Drives and MotivesDocument10 pages10 Basic Drives and MotivesHammna AshrafPas encore d'évaluation

- ParaphraseDocument8 pagesParaphraseHammna AshrafPas encore d'évaluation

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (890)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (399)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (73)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5794)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1090)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2219)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (344)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (265)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)

- How To Make Money in The Stock MarketDocument40 pagesHow To Make Money in The Stock Markettcb66050% (2)

- Dissolved Oxygen Primary Prod Activity1Document7 pagesDissolved Oxygen Primary Prod Activity1api-235617848Pas encore d'évaluation

- Single Wall Fuel Tank: FP 2.7 A-C Fire Pump SystemsDocument1 pageSingle Wall Fuel Tank: FP 2.7 A-C Fire Pump Systemsricardo cardosoPas encore d'évaluation

- Terms and Condition PDFDocument2 pagesTerms and Condition PDFSeanmarie CabralesPas encore d'évaluation

- Engine Controls (Powertrain Management) - ALLDATA RepairDocument4 pagesEngine Controls (Powertrain Management) - ALLDATA Repairmemo velascoPas encore d'évaluation

- 5.PassLeader 210-260 Exam Dumps (121-150)Document9 pages5.PassLeader 210-260 Exam Dumps (121-150)Shaleh SenPas encore d'évaluation

- E-TON - Vector ST 250Document87 pagesE-TON - Vector ST 250mariusgrosyPas encore d'évaluation

- CAP Regulation 20-1 - 05/29/2000Document47 pagesCAP Regulation 20-1 - 05/29/2000CAP History LibraryPas encore d'évaluation

- Bunkering Check List: Yacht InformationDocument3 pagesBunkering Check List: Yacht InformationMarian VisanPas encore d'évaluation

- Bernardo Corporation Statement of Financial Position As of Year 2019 AssetsDocument3 pagesBernardo Corporation Statement of Financial Position As of Year 2019 AssetsJean Marie DelgadoPas encore d'évaluation

- Growatt SPF3000TL-HVM (2020)Document2 pagesGrowatt SPF3000TL-HVM (2020)RUNARUNPas encore d'évaluation

- Janapriya Journal of Interdisciplinary Studies - Vol - 6Document186 pagesJanapriya Journal of Interdisciplinary Studies - Vol - 6abiskarPas encore d'évaluation

- International Convention Center, BanesworDocument18 pagesInternational Convention Center, BanesworSreeniketh ChikuPas encore d'évaluation

- Max 761 CsaDocument12 pagesMax 761 CsabmhoangtmaPas encore d'évaluation

- Bob Duffy's 27 Years in Database Sector and Expertise in SQL Server, SSAS, and Data Platform ConsultingDocument26 pagesBob Duffy's 27 Years in Database Sector and Expertise in SQL Server, SSAS, and Data Platform ConsultingbrusselarPas encore d'évaluation

- CFEExam Prep CourseDocument28 pagesCFEExam Prep CourseM50% (4)

- ASME Y14.6-2001 (R2007), Screw Thread RepresentationDocument27 pagesASME Y14.6-2001 (R2007), Screw Thread RepresentationDerekPas encore d'évaluation

- 3.4 Spending, Saving and Borrowing: Igcse /O Level EconomicsDocument9 pages3.4 Spending, Saving and Borrowing: Igcse /O Level EconomicsRingle JobPas encore d'évaluation

- Project The Ant Ranch Ponzi Scheme JDDocument7 pagesProject The Ant Ranch Ponzi Scheme JDmorraz360Pas encore d'évaluation

- Lorilie Muring ResumeDocument1 pageLorilie Muring ResumeEzekiel Jake Del MundoPas encore d'évaluation

- Beams On Elastic Foundations TheoryDocument15 pagesBeams On Elastic Foundations TheoryCharl de Reuck100% (1)

- Weka Tutorial 2Document50 pagesWeka Tutorial 2Fikri FarisPas encore d'évaluation

- Proposal Semister ProjectDocument7 pagesProposal Semister ProjectMuket AgmasPas encore d'évaluation

- For Mail Purpose Performa For Reg of SupplierDocument4 pagesFor Mail Purpose Performa For Reg of SupplierAkshya ShreePas encore d'évaluation

- Internship Report Recruitment & Performance Appraisal of Rancon Motorbikes LTD, Suzuki Bangladesh BUS 400Document59 pagesInternship Report Recruitment & Performance Appraisal of Rancon Motorbikes LTD, Suzuki Bangladesh BUS 400Mohammad Shafaet JamilPas encore d'évaluation

- Banas Dairy ETP Training ReportDocument38 pagesBanas Dairy ETP Training ReportEagle eye0% (2)

- Model S-20 High Performance Pressure Transmitter For General Industrial ApplicationsDocument15 pagesModel S-20 High Performance Pressure Transmitter For General Industrial ApplicationsIndra PutraPas encore d'évaluation

- Competency-Based Learning GuideDocument10 pagesCompetency-Based Learning GuideOliver BC Sanchez100% (2)

- Ayushman BharatDocument20 pagesAyushman BharatPRAGATI RAIPas encore d'évaluation

- Bill of ConveyanceDocument3 pagesBill of Conveyance:Lawiy-Zodok:Shamu:-El80% (5)