Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Opioid Toxicity PDF

Transféré par

AdreiTheTripleATitre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Opioid Toxicity PDF

Transféré par

AdreiTheTripleADroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

11/27/13

Opioid Toxicity

Today News Reference Education Log In Register

Opioid Toxicity

Author: Everett Stephens, MD; Chief Editor: Asim Tarabar, MD more... Updated: Oct 23, 2012

Background

Pain is arguably the most common reason why patients seek treatment, especially in the ED. The modern physician wields many tools to relieve pain, the most potent of which are opioids. The term narcotic specifically refers to any substance that induces sleep, insensibility, or stupor, and it is used to refer to opioids or opioid derivatives. It is derived from the Greek "narke" that means "numbness or torpor." It is common, however inaccurate, that the public uses the term narcotics for any illicit psychoactive substance. In cultivation since approximately 1500 BC, pure opium is a mixture of alkaloids extracted from the sap of unripened seedpods of Papaver somniferum (poppy). Opiates, such as heroin, codeine, or morphine, are natural derivatives of these alkaloids. The term opiate is often used (albeit slightly incorrectly) to refer to synthetic opiate derivatives, such as oxycodone, as well as true opiates. Although opioids constitute a relatively small percentage of total overdoses encountered in the ED, they merit particular attention because of the potential mortality/morbidity they cause when unrecognized and untreated, as well as the relative ease of reversing their effects. The notable prevalence of opioids in current prescribing patterns, as well as recreational uses, mandates that physicians maintain a high index of suspicion when treating the patient who is unconscious for unknown reasons. Opioid use and abuse have been reported as increasing in frequency in the past few years, a trend that has been blamed in increasing utilization of opioids by medical personnel as well as illicit drug abuse.[1] While increased availability certainly plays a role in opioid abuse, the link between legitimate use and abuse is not well proven.[2, 3] The increasing use and abuse of opioids has received increasing attention in recentyears.[4, 5] The medical profession, licensing agencies, and federal enforcement have been increasingly focusing on prescribing practices for short- and long-term use of narcotic substances. Some states have enacted sweeping legislation to require more oversight in the use of narcotics (eg, Kentucky HB1). Such legislation affects the prescribing practices of providers in an attempt to reduce diversion of legitimate opiate prescriptions. Statewide registers of controlled substances are available in many states and can help providers track use patterns among patients in an effort to identify those at high risk of abuse or diversion.

Pathophysiology

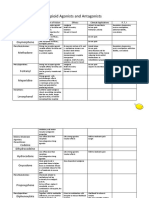

Activation of opioid receptors results in inhibition of synaptic neurotransmission in the central nervous system (CNS) and peripheral nervous system (PNS). Opioids bind to and enhance neurotransmission at 3 major classes of opioid receptors. It is also recognized that several poorly defined classes of opioid receptors exist with relatively minor effects. The physiological effects of opioids are mediated principally through mu and kappa receptors in the CNS and periphery. Mu receptor effects include analgesia, euphoria, respiratory depression, and miosis. Kappa receptor effects include analgesia, miosis, respiratory depression, and sedation. Two other opiate receptors that mediate the effects of certain opiates include sigma and delta sites. Sigma receptors mediate dysphoria, hallucinations, and psychosis; delta receptor agonism results in euphoria, analgesia, and seizures. The opiate antagonists (eg, naloxone, nalmefene, naltrexone) antagonize the effects at all 4 opiate receptors. Common classifications divide the opioids into agonist, partial agonist, or agonist-antagonist agents and natural, semisynthetic, or synthetic. Opioids decrease the perception of pain, rather than eliminate or reduce the painful stimulus. Inducing slight euphoria, opioid agonists reduce the sensitivity to exogenous stimuli. The GI tract and

emedicine.medscape.com/article/815784-overview 1/5

11/27/13

Opioid Toxicity

the respiratory mucosa provide easy absorption for most opioids. Peak effects generally are reached in 10 minutes with the intravenous route, 10-15 minutes after nasal insufflation (eg, butorphanol, heroin), 30-45 minutes with the intramuscular route, 90 minutes with the oral route, and 2-4 hours after dermal application (ie, fentanyl). Following therapeutic doses, most absorption occurs in the small intestine. Toxic doses may have delayed absorption because of delayed gastric emptying and slowed gut motility. Most opioids are metabolized by hepatic conjugation to inactive compounds that are excreted readily in the urine. Certain opioids (eg, propoxyphene, fentanyl, buprenorphine) are more lipid soluble and can be stored in the fatty tissues of the body. All opioids have a prolonged duration of action in patients with liver disease (eg, cirrhosis) because of impaired hepatic metabolism. This may lead to drug accumulation and opioid toxicity . Opiate metabolites are excreted in the urine. Impaired renal function can lead to toxic effects from accumulated drug or active metabolites (eg, normeperidine).

Epidemiology

Frequency

United States Opioids are prescribed widely, often in concert with other analgesics, including nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) or muscle relaxants. Given all toxicologic presentations, pure opioid ingestions are generally a small proportion of ED overdose cases. The etiology of overdoses presenting to an ED often reflects local prescribing tendencies. Polypharmacy overdoses that include opioids can be a challenge for even the most experienced clinician. Fortunately, pharmacologic reversal of the opioid component can assist in the diagnosis of these potentially complex cases. Data from the Drug Abuse Warning Network (DAWN) from 1990-1996 indicated that the abuse of opioid analgesics (as recorded from the number of hospital ED visits) is low; compared with the abuse of other drugs, the abuse of opioid analgesics accounts for 3.8-5.1% of ED presentations. In 1998, a total of 36,848 opiate exposures (pure and mixed preparations) were reported to US poison control centers, of which 1227 (3.3%) resulted in major toxicity and 161 (0.4%) resulted in death. The CDC reports that methadone contributed to 31.4% of opioid-related deaths in the United States from 19992010. Methadone also accounted for 39.8% of all single-drug opioid-related deaths. The overdose death rate associated with methadone was significantly higher than that associated with other opioid-related deaths among multidrug and single-drug deaths.[6]

Mortality/Morbidity

The predominant cause of morbidity and mortality from pure opioid overdoses is respiratory compromise. Less commonly, acute lung injury, status epilepticus, and cardiotoxicity occur in the overdose setting. Case reports of increased incidence of mortality have been documented in patients with coexistent stenosing lesions of the upper airway.[7] Morbidities due to co-ingestants must be considered in polypharmacy overdoses, and they vary depending on the co-ingestant. Intent of the overdose also plays a role; the addition of suicidal intent is linked to increased emergency department usage,[8] and such intent could suggest higher dosages of narcotics or co-ingestants.

Contributor Information and Disclosures

Author Everett Stephens, MD Assistant Clinical Professor, Department of Emergency Medicine, University of Louisville Everett Stephens, MD is a member of the following medical societies: American Academy of Emergency Medicine Disclosure: Nothing to disclose. Specialty Editor Board Mark Louden, MD Assistant Professor of Clinical Medicine, Division of Emergency Medicine, Department of Medicine, University of Miami, Leonard M Miller School of Medicine

emedicine.medscape.com/article/815784-overview 2/5

11/27/13

Opioid Toxicity

Mark Louden, MD is a member of the following medical societies: American Academy of Emergency Medicine and American College of Emergency Physicians Disclosure: Nothing to disclose. John T VanDeVoort, PharmD Regional Director of Pharmacy, Sacred Heart and St Joseph's Hospitals John T VanDeVoort, PharmD is a member of the following medical societies: American Society of HealthSystem Pharmacists Disclosure: Nothing to disclose. Michael J Burns, MD Instructor, Department of Emergency Medicine, Harvard University Medical School, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center Michael J Burns, MD is a member of the following medical societies: American Academy of Clinical Toxicology, American College of Emergency Physicians, American College of Medical Toxicology, and Society for Academic Emergency Medicine Disclosure: Nothing to disclose. John D Halamka, MD, MS Associate Professor of Medicine, Harvard Medical School, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center; Chief Information Officer, CareGroup Healthcare System and Harvard Medical School; Attending Physician, Division of Emergency Medicine, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center John D Halamka, MD, MS is a member of the following medical societies: American College of Emergency Physicians, American Medical Informatics Association, Phi Beta Kappa, and Society for Academic Emergency Medicine Disclosure: Nothing to disclose. Chief Editor Asim Tarabar, MD Assistant Professor, Director, Medical Toxicology, Department of Emergency Medicine, Yale University School of Medicine; Consulting Staff, Department of Emergency Medicine, Yale-New Haven Hospital Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

References

1. Paulozzi LJ. Opioid analgesic involvement in drug abuse deaths in American metropolitan areas. Am J Public Health. Oct 2006;96(10):1755-7. [Medline]. [Full Text]. 2. Compton WM, Volkow ND. Major increases in opioid analgesic abuse in the United States: concerns and strategies. Drug Alcohol Depend. Feb 1 2006;81(2):103-7. [Medline]. 3. Joranson DE, Gilson AM. Wanted: a public health approach to prescription opioid abuse and diversion. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. Sep 2006;15(9):632-4. [Medline]. 4. Tyndale R. Drug addiction: a critical problem calling for novel solutions. Clin Pharmacol Ther. Apr 2008;83(4):503-6. [Medline]. 5. Baker DD, Jenkins AJ. A comparison of methadone, oxycodone, and hydrocodone related deaths in Northeast Ohio. J Anal Toxicol. Mar 2008;32(2):165-71. [Medline]. 6. Vital signs: risk for overdose from methadone used for pain relief - United States, 1999-2010. MMWR Morb Mortal Wk ly Rep. Jul 6 2012;61(26):493-7. [Medline]. 7. Byard RW, Gilbert JD. Narcotic administration and stenosing lesions of the upper airway--a potentially lethal combination. J Clin Forensic Med. Feb 2005;12(1):29-31. [Medline]. 8. Backmund M, Schuetz C, Meyer K, Edlin BR, Reimer J. The risk of emergency room treatment due to overdose in injection drug users. J Addict Dis . 2009;28(1):68-73. [Medline]. 9. US Food and Drug Administration. Propoxyphene: Withdrawal - Risk of Cardiac Toxicity. Available at

emedicine.medscape.com/article/815784-overview 3/5

11/27/13

Opioid Toxicity

http://www.fda.gov/Safety/MedWatch/SafetyInformation/SafetyAlertsforHumanMedicalProducts/ucm234389.htm. Accessed October 11, 2012. 10. Kerr D, Kelly AM, Dietze P, Jolley D, Barger B. Randomized controlled trial comparing the effectiveness and safety of intranasal and intramuscular naloxone for the treatment of suspected heroin overdose. Addiction. Dec 2009;104(12):2067-74. [Medline]. 11. Yokell MA, Zaller ND, Green TC, McKenzie M, Rich JD. Intravenous use of illicit buprenorphine/naloxone to reverse an acute heroin overdose. J Opioid Manag. Jan-Feb 2012;8(1):63-6. [Medline]. 12. Palmiere C, Brunel C, Sporkert F, Augsburger M. An unusual case of accidental poisoning: fatal methadone inhalation. J Forensic Sci. Jul 2011;56(4):1072-5. [Medline]. 13. Vital signs: risk for overdose from methadone used for pain relief - United States, 1999-2010. MMWR Morb Mortal Wk ly Rep. Jul 6 2012;61(26):493-7. [Medline]. 14. Kerr D, Dietze P, Kelly AM. Intranasal naloxone for the treatment of suspected heroin overdose. Addiction. Mar 2008;103(3):379-86. [Medline]. 15. Beletsky L, Ruthazer R, Macalino GE, Rich JD, Tan L, Burris S. Physicians' knowledge of and willingness to prescribe naloxone to reverse accidental opiate overdose: challenges and opportunities. J Urban Health. Jan 2007;84(1):126-36. [Medline]. [Full Text]. 16. Porter R, O'Reilly H. Pulmonary hemorrhage: a rare complication of opioid overdose. Pediatr Emerg Care. Aug 2011;27(8):742-4. [Medline]. 17. Weiner AL, Bayer MJ, McKay CA Jr, DeMeo M, Starr E. Anticholinergic poisoning with adulterated intranasal cocaine. Am J Emerg Med. Sep 1998;16(5):517-20. [Medline]. 18. Brewer C, Streel E. Recent developments in naltrexone implants and depot injections for opiate abuse: the new kid on the block is approaching adulthood. Adicciones . 2010;22(4):285-91. [Medline]. 19. Peles E, Schreiber S, Adelson M. Tricyclic antidepressants abuse, with or without benzodiazepines abuse, in former heroin addicts currently in methadone maintenance treatment (MMT). Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. Mar 2008;18(3):188-93. [Medline]. 20. Dershwitz M, Walsh JL, Morishige RJ, et al. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of inhaled versus intravenous morphine in healthy volunteers. Anesthesiology. Sep 2000;93(3):619-28. [Medline]. 21. Ward ME, Woodhouse A, Mather LE, et al. Morphine pharmacokinetics after pulmonary administration from a novel aerosol delivery system. Clin Pharmacol Ther. Dec 1997;62(6):596-609. [Medline]. 22. Mather LE, Woodhouse A, Ward ME, Farr SJ, Rubsamen RA, Eltherington LG. Pulmonary administration of aerosolised fentanyl: pharmacokinetic analysis of systemic delivery. Br J Clin Pharmacol. Jul 1998;46(1):37-43. [Medline]. [Full Text]. 23. Hutchins KD, Pierre-Louis PJ, Zaretski L, Williams AW, Lin RL, Natarajan GA. Heroin body packing: three fatal cases of intestinal perforation. J Forensic Sci. Jan 2000;45(1):42-7. [Medline]. 24. Olmedo R, Nelson L, Chu J, Hoffman RS. Is surgical decontamination definitive treatment of "bodypackers"?. Am J Emerg Med. Nov 2001;19(7):593-6. [Medline]. 25. Biddle C, Gilliland C. Transdermal and transmucosal administration of pain-relieving and anxiolytic drugs: a primer for the critical care practitioner. Heart Lung. Mar 1992;21(2):115-24. [Medline]. 26. Cherny NI. Opioid analgesics: comparative features and prescribing guidelines. Drugs . May 1996;51(5):713-37. [Medline]. 27. Clark NC, Lintzeris N, Muhleisen PJ. Severe opiate withdrawal in a heroin user precipitated by a massive buprenorphine dose. Med J Aust. Feb 18 2002;176(4):166-7. [Medline]. 28. Crabtree BL. Review of naltrexone, a long-acting opiate antagonist. Clin Pharm. May-Jun 1984;3(3):27380. [Medline]. 29. Gaeta TJ, Capodano RJ, Spevack TA. Potential danger of nalmefene use in the emergency department. Ann Emerg Med. Jan 1997;29(1):193-4. [Medline]. 30. Hamilton RJ, Perrone J, Hoffman R, et al. A descriptive study of an epidemic of poisoning caused by

emedicine.medscape.com/article/815784-overview 4/5

11/27/13

Opioid Toxicity

heroin adulterated with scopolamine. J Toxicol Clin Toxicol. 2000;38(6):597-608. [Medline]. 31. Henderson CA, Reynolds JE. Acute pulmonary edema in a young male after intravenous nalmefene. Anesth Analg. Jan 1997;84(1):218-9. [Medline]. 32. Henry JA. Management of drug abuse emergencies. J Accid Emerg Med. Nov 1996;13(6):370-2. [Medline]. [Full Text]. 33. Howell JM. Emergency Medicine. Philadelphia, Pa: WB Saunders; 1998:1494-8. 34. Iqbal N. Recoverable hearing loss with amphetamines and other drugs. J Psychoactive Drugs . Jun 2004;36(2):285-8. [Medline]. 35. Joranson DE, Ryan KM, Gilson AM, Dahl JL. Trends in medical use and abuse of opioid analgesics. JAMA. Apr 5 2000;283(13):1710-4. [Medline]. 36. Kelly AM, Koutsogiannis Z. Intranasal naloxone for life threatening opioid toxicity. Emerg Med J . Jul 2002;19(4):375. [Medline]. [Full Text]. 37. Markovchick V. Emergency Medicine Secrets . Philadelphia, Pa: Hanley & Belfus Inc; 1993:308-11. 38. Medical Economics Staff. Physician's Desk Reference. Montvale, NJ: Medical Economics Co; 1998:911. 39. Rosen P, Barkin RM, Danzl DF, et al, eds. Emergency Medicine: Concepts and Clinical Practice. 3rd ed. St Louis, Mo: Mosby; 1992:2603-17. 40. Sachdeva DK, Jolly BT. Tramadol overdose requiring prolonged opioid antagonism. Am J Emerg Med. Mar 1997;15(2):217-8. [Medline]. 41. Strange GR, Ahrens W. Pediatric Emergency Medicine: A Comprehensive Study Guide. 1996:563-4. 42. The Le Dain Commission Report. Report of the Canadian Government Commission of Inquiry into the NonMedical Use of Drugs: Narcotics. 1970. [Full Text]. 43. Tintinalli JE, Krome R, Ruiz E, et al, eds. Emergency Medicine: A Comprehensive Study Guide. 4th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 1997:772-5. 44. Vilke GM, Buchanan J, Dunford JV, Chan TC. Are heroin overdose deaths related to patient release after prehospital treatment with naloxone?. Prehosp Emerg Care. Jul-Sep 1999;3(3):183-6. [Medline]. 45. Washton AM, Resnick RB. Clonidine in opiate withdrawal: review and appraisal of clinical findings. Pharmacotherapy. Sep-Oct 1981;1(2):140-6. [Medline]. Medscape Reference 2011 WebMD, LLC

emedicine.medscape.com/article/815784-overview

5/5

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (119)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (399)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (587)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2219)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5794)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1090)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (344)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (890)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- Opioid Agonists and AntagonistsDocument5 pagesOpioid Agonists and AntagonistsCas BuPas encore d'évaluation

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (73)

- Septic Shock TreatmentDocument22 pagesSeptic Shock TreatmentAdreiTheTripleA100% (1)

- Narcotics Controlled Drugs TableDocument4 pagesNarcotics Controlled Drugs TableDurgaNadellaPas encore d'évaluation

- Schedule of Controlled DrugsDocument1 pageSchedule of Controlled DrugsKaye AbordoPas encore d'évaluation

- Vicodin Drug Study Que Fransis A.Document3 pagesVicodin Drug Study Que Fransis A.Irene Grace BalcuevaPas encore d'évaluation

- Classification of Drugs and Their EffectsDocument3 pagesClassification of Drugs and Their EffectsshriPas encore d'évaluation

- Huruf ANDocument3 pagesHuruf ANAdreiTheTripleAPas encore d'évaluation

- Z and Z and A and B and C and D and e and FDocument124 pagesZ and Z and A and B and C and D and e and FAdreiTheTripleAPas encore d'évaluation

- Huruf AHDocument3 pagesHuruf AHAdreiTheTripleAPas encore d'évaluation

- Laporan Transaksi: No. Rekening Nama Produk Mata Uang Nomor CIFDocument2 pagesLaporan Transaksi: No. Rekening Nama Produk Mata Uang Nomor CIFAdreiTheTripleAPas encore d'évaluation

- Huruf AADocument3 pagesHuruf AAAdreiTheTripleAPas encore d'évaluation

- Huruf LDocument3 pagesHuruf LAdreiTheTripleAPas encore d'évaluation

- Huruf UDocument3 pagesHuruf UAdreiTheTripleAPas encore d'évaluation

- Huruf VDocument3 pagesHuruf VAdreiTheTripleAPas encore d'évaluation

- Huruf JDocument3 pagesHuruf JAdreiTheTripleAPas encore d'évaluation

- 2014 AHA/ACC Guideline for NSTE-ACS ManagementDocument151 pages2014 AHA/ACC Guideline for NSTE-ACS ManagementParadina WulandariPas encore d'évaluation

- Huruf RDocument3 pagesHuruf RAdreiTheTripleAPas encore d'évaluation

- Huruf TDocument3 pagesHuruf TAdreiTheTripleAPas encore d'évaluation

- Huruf GDocument3 pagesHuruf GAdreiTheTripleAPas encore d'évaluation

- GOLD Pocket Guide 2014 COPDDocument32 pagesGOLD Pocket Guide 2014 COPDNatalia CvPas encore d'évaluation

- Huruf ADocument3 pagesHuruf AAdreiTheTripleAPas encore d'évaluation

- Global Initiative For Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease. Update 2014Document102 pagesGlobal Initiative For Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease. Update 2014Guss LopezPas encore d'évaluation

- Myasthenia Gravis: Practice EssentialsDocument12 pagesMyasthenia Gravis: Practice EssentialsAdreiTheTripleA0% (1)

- Huruf eDocument3 pagesHuruf eAdreiTheTripleAPas encore d'évaluation

- Delusions of ParasitosisDocument5 pagesDelusions of ParasitosisAdreiTheTripleAPas encore d'évaluation

- Cutaneous Larva Migrans - Doctor - Patient - CoDocument5 pagesCutaneous Larva Migrans - Doctor - Patient - CoAdreiTheTripleAPas encore d'évaluation

- The Future of Diagnosis, Theraphy and ProphylaxisDocument11 pagesThe Future of Diagnosis, Theraphy and ProphylaxisAdreiTheTripleAPas encore d'évaluation

- Congenital NeviDocument6 pagesCongenital NeviAdreiTheTripleAPas encore d'évaluation

- Guillain Barre SyndromeDocument13 pagesGuillain Barre SyndromeAdreiTheTripleAPas encore d'évaluation

- Pa Pill EdemaDocument3 pagesPa Pill EdemaAdreiTheTripleAPas encore d'évaluation

- Choking - Infant Under 1 Year - MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia (Print Version)Document3 pagesChoking - Infant Under 1 Year - MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia (Print Version)AdreiTheTripleAPas encore d'évaluation

- Malignant MelanomaDocument12 pagesMalignant MelanomaAdreiTheTripleAPas encore d'évaluation

- Heimlich Maneuver - MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia (Print Version)Document2 pagesHeimlich Maneuver - MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia (Print Version)AdreiTheTripleAPas encore d'évaluation

- Distributive Shock PDFDocument8 pagesDistributive Shock PDFAdreiTheTripleAPas encore d'évaluation

- Analgesic & AntipyreticsDocument7 pagesAnalgesic & AntipyreticsRaymund RazonPas encore d'évaluation

- Oral Oxycodone For Acute Postoperative PainDocument20 pagesOral Oxycodone For Acute Postoperative PainArmi ZakaPas encore d'évaluation

- Suboxone Brochure LKDDocument2 pagesSuboxone Brochure LKDJohn McconnellPas encore d'évaluation

- Obat PatenDocument8 pagesObat PatenrismaPas encore d'évaluation

- FentanylDocument11 pagesFentanylJereel Hope BaconPas encore d'évaluation

- Etonitazene - An Opioid Selective For The Mu Receptor Types - Moolten MS, Fishman JB, Chen JC, Carlson KR - Life Sci 52 (1993) PL199-PL203Document5 pagesEtonitazene - An Opioid Selective For The Mu Receptor Types - Moolten MS, Fishman JB, Chen JC, Carlson KR - Life Sci 52 (1993) PL199-PL203muopioidreceptorPas encore d'évaluation

- Project Dawn Brochure0515Document2 pagesProject Dawn Brochure0515api-265745737Pas encore d'évaluation

- Latest List of Monitored Drugs in Ontario (2016)Document40 pagesLatest List of Monitored Drugs in Ontario (2016)roxiemannPas encore d'évaluation

- Rekapitulasi Laporan Narkotika: NO Nama Satuan Stok Awal Pemasukan PBFDocument10 pagesRekapitulasi Laporan Narkotika: NO Nama Satuan Stok Awal Pemasukan PBFMiftah JannahPas encore d'évaluation

- Fentanyl Fact SheetDocument2 pagesFentanyl Fact SheetSinclair Broadcast Group - EugenePas encore d'évaluation

- Opioid Conversion Chart 2020 1Document1 pageOpioid Conversion Chart 2020 1aengus42Pas encore d'évaluation

- ترجمه PDFDocument4 pagesترجمه PDFAshkan Abbasi0% (1)

- FORMULA PARACETAMOL ANALGESICOSDocument3 pagesFORMULA PARACETAMOL ANALGESICOSDanilo M MadanesPas encore d'évaluation

- Literature ReviewDocument3 pagesLiterature Reviewapi-609233193Pas encore d'évaluation

- 6.2 Opioid & Non-OpioidsDocument18 pages6.2 Opioid & Non-OpioidsAsem AlhazmiPas encore d'évaluation

- Opioid AnalgesicsDocument29 pagesOpioid AnalgesicsamonlisaPas encore d'évaluation

- T Wycross 1984Document6 pagesT Wycross 1984Ha HaPas encore d'évaluation

- Opioid Rotation Conversion Learning PackageDocument18 pagesOpioid Rotation Conversion Learning Packagepaul casillasPas encore d'évaluation

- Rekapitulasi Laporan Narkotika: NO Nama Satuan Stok Awal Pemasukan PBFDocument13 pagesRekapitulasi Laporan Narkotika: NO Nama Satuan Stok Awal Pemasukan PBFFarmasi Bunda WadungasriPas encore d'évaluation

- Atestat 1Document22 pagesAtestat 1RalucaxdPas encore d'évaluation

- Sudnaloxonesuboxone 8Document2 pagesSudnaloxonesuboxone 8api-665140662Pas encore d'évaluation

- Dangerous Drugs Act 1952 (Consolidated To No 23 of 1990) PDFDocument11 pagesDangerous Drugs Act 1952 (Consolidated To No 23 of 1990) PDFdesmond100% (1)

- 2019 Aiken County Accidental OverdosesDocument1 page2019 Aiken County Accidental OverdosesJeremy TurnagePas encore d'évaluation

- List of Schedule I Drugs (US) - Wikipedia, The Free EncyclopediaDocument7 pagesList of Schedule I Drugs (US) - Wikipedia, The Free EncyclopediaterterdgdfgdfgdfgfdgPas encore d'évaluation

- NaloxBox Press Event Agenda and News ReleaseDocument5 pagesNaloxBox Press Event Agenda and News ReleaseABC6/FOX28Pas encore d'évaluation