Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

People v. Gozo THE PEOPLE OF THE PHILIPPINES, Plaintiff-Appellee, vs. LORETA GOZO, Defendant-Appellant. G.R. No. L-36409 October 26, 1973 Public International Law

Transféré par

Jacinto Jr JameroTitre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

People v. Gozo THE PEOPLE OF THE PHILIPPINES, Plaintiff-Appellee, vs. LORETA GOZO, Defendant-Appellant. G.R. No. L-36409 October 26, 1973 Public International Law

Transféré par

Jacinto Jr JameroDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

THE PEOPLE OF THE PHILIPPINES, plaintiff-appellee, vs. LORETA GOZO, defendant-appellant. G.R. No.

L-36409 October 26, 1973 FACTS: LORETA GOZO, accused, bought a house and lot located inside the United States Naval Reservation within the territorial jurisdiction of Olongapo City. She demolished the house and built another one in its place, without a building permit from the City Mayor of Olongapo City, because she was told by an assistant in the City Mayor's office, as well as by her neighbors in the area, that such building permit was not necessary for the construction of the house. On December 29, 1966, a building and lot inspector of the City Engineer's Office, with Patrolman apprehended four carpenters working on the house of the accused and they brought the carpenters to the police headquarters for interrogation. ... After due investigation, Loreta Gozo was charged with violation of Municipal Ordinance No. 14, the City Fiscal's Office. The City Court of Olongapo City found her guilty of violating Ordinance and sentenced her to an imprisonment of one month as well as to pay the costs. The Court of Instance of Zambales, on appeal, found her guilty on the above facts of violating such municipal ordinance but would sentence her merely to pay a fine of P200.00 and to demolish the house thus erected. She elevated the case to the Court of Appeals but in her brief, she would put in issue the validity of such an ordinance on constitutional ground or at the very least its applicability to her in view of the location of her dwelling within the naval base. Appellant seeks to set aside a judgment of the Court of First Instance. ISSUE: Whether or not, Philippines has territorial jurisdiction over the land occupied by the US Naval Reserve and whether or not the imposition of building permit is binding to the said territory. RULE: (quoted from the case) As was so emphatically set forth by Justice Tuason in Acierto case: "By the Agreement, it should be noted, the Philippine Government merely consents that the United States exercise jurisdiction in certain cases. The consent was given purely as a matter of comity, courtesy, or expediency. The Philippine Government has not abdicated its sovereignty over the bases as part of the Philippine territory or divested itself completely of jurisdiction over offenses committed therein. Under the terms of the treaty, the United States Government has prior or preferential but not exclusive jurisdiction of such offenses. The Philippine Government retains not only jurisdictional rights not granted, but also all such ceded rights as the United States Military authorities for reasons of their own decline to make use of. The first proposition is implied from the fact of Philippine sovereignty over the bases; the second from the express provisions of the treaty." There was a reiteration of such a view in Reagan v. CIR case. Thus: "Nothing is better settled than that the Philippines being independent and sovereign, its authority may be exercised over its entire domain. There is no portion thereof that is beyond its power. Within its limits, its decrees are supreme, its commands paramount. Its laws govern therein, and everyone to whom it applies must submit to its terms. That is the extent of its jurisdiction, both territorial and personal. Necessarily, likewise, it has to be exclusive. If it were not thus, there is a diminution of sovereignty." Then came this paragraph dealing with the principle of auto-limitation: "It is to be admitted any state may, by its consent, express or implied, submit to a restriction of its sovereign rights. There may thus be a curtailment of what otherwise is a power plenary in character. That is the concept of sovereignty as auto-limitation, which, in the succinct language of Jellinek, "is the property of a state-force due to which it has the exclusive capacity of legal self-determination and self-restriction." A state then, if it chooses to, may refrain from the exercise of what otherwise is illimitable competence." The opinion was at pains to point out though that even then, there is at the most diminution of jurisdictional rights, not its disappearance. The words employed follow: "Its laws may as to some persons found within its territory no longer control. Nor does the matter end there. It is not precluded from allowing another power to participate in the exercise of jurisdictional right over certain portions of its territory. If it does so, it by no means follows that such areas become impressed with an alien character. They retain their status as native soil. They are still subject to its authority. Its jurisdiction may be diminished, but it does not disappear. So it is with the bases under lease to the American armed forces by virtue of the military bases agreement of 1947. They are not and cannot be foreign territory." To quote from Acierto case anew: "The carrying out of the provisions of the Bases Agreement is the concern of the contracting parties alone. Whether, therefore, a given case which by the treaty comes within the United States jurisdiction should be transferred to the Philippine authorities is a matter about which the accused has nothing to do or say. In other words, the rights granted to the United States by the treaty insure solely to that country and can not be raised by the offender." Applying such into the case, since Loreta Gozo was not a party to the Philippine-US agreement, she is not entitled to such privilege. She is required to follow the city ordinance and is liable for such omission. WHEREFORE, the appealed decision is affirmed insofar as it found the accused, Loreta Gozo, guilty beyond reasonable doubt of a violation of Municipal Ordinance.

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- People v. Gozo GR No. L-36409 - The Concept of The StateDocument2 pagesPeople v. Gozo GR No. L-36409 - The Concept of The StateALMIRA SHANE Abada MANLAPAZPas encore d'évaluation

- Manish Mahtani Citizenship CaseDocument30 pagesManish Mahtani Citizenship CasebenPas encore d'évaluation

- Week 4 CasesDocument181 pagesWeek 4 CasesMary Ann AmbitaPas encore d'évaluation

- In RE BermudezDocument1 pageIn RE BermudezSharon_Cerro_6742Pas encore d'évaluation

- Holy See VSDocument2 pagesHoly See VSMicho DiezPas encore d'évaluation

- De Leon v. Esguerra (Autonomy of Barangays)Document19 pagesDe Leon v. Esguerra (Autonomy of Barangays)kjhenyo218502Pas encore d'évaluation

- Philippine Bar Association V COMELECDocument2 pagesPhilippine Bar Association V COMELECChristian AribasPas encore d'évaluation

- Consti2Digest - ACCFA Vs CUGCO, G.R. No. L-21484 (29 Nov 1969)Document1 pageConsti2Digest - ACCFA Vs CUGCO, G.R. No. L-21484 (29 Nov 1969)Lu CasPas encore d'évaluation

- 083-Chavez v. JBC G.R. No. 202242 April 16, 2013Document18 pages083-Chavez v. JBC G.R. No. 202242 April 16, 2013Eunice ChavezPas encore d'évaluation

- in Re Saturnino Bermudez, G.R. No. 76180Document2 pagesin Re Saturnino Bermudez, G.R. No. 76180Inez PadsPas encore d'évaluation

- Strict or Liberal Construction of StatutesDocument24 pagesStrict or Liberal Construction of StatutesFrench TemplonuevoPas encore d'évaluation

- Case Digest - Philippine Virginia Tobacco Association vs. Court of Industrial RelationsDocument2 pagesCase Digest - Philippine Virginia Tobacco Association vs. Court of Industrial RelationsJan Marie RamosPas encore d'évaluation

- Case Digest 2Document9 pagesCase Digest 2Andrea Gural De GuzmanPas encore d'évaluation

- Lim Vs BrownwellDocument2 pagesLim Vs Brownwellgherold benitez100% (1)

- Case Digest For Caltex Vs Palomar 18 SCRA 247Document3 pagesCase Digest For Caltex Vs Palomar 18 SCRA 247RR FPas encore d'évaluation

- Province of North Cotabato Vs GRP Peace Panel (Territory - Case Digest)Document2 pagesProvince of North Cotabato Vs GRP Peace Panel (Territory - Case Digest)Bianca Fenix100% (1)

- Supreme Court Rules Against Immunity for Public Officials in Eviction CaseDocument2 pagesSupreme Court Rules Against Immunity for Public Officials in Eviction CaseYhan AberdePas encore d'évaluation

- G.R. No. L-44640. October 12, 1976 DigestDocument2 pagesG.R. No. L-44640. October 12, 1976 DigestMaritoni Roxas100% (2)

- Imbong Vs ComelecDocument3 pagesImbong Vs ComelecFranz JavierPas encore d'évaluation

- Lacson-Magallanes Co., Inc. vs. Paño, G.R. No. L-27811, 17 November 1967, 21 SCRA 895Document1 pageLacson-Magallanes Co., Inc. vs. Paño, G.R. No. L-27811, 17 November 1967, 21 SCRA 895Kyle JamiliPas encore d'évaluation

- Taruc vs. Bishop Dela Cruz (G.R. No. 144801)Document4 pagesTaruc vs. Bishop Dela Cruz (G.R. No. 144801)Ryan LeocarioPas encore d'évaluation

- LAW 116 - IBP v. Zamora (G.R. No. 141284)Document3 pagesLAW 116 - IBP v. Zamora (G.R. No. 141284)Aaron Cade CarinoPas encore d'évaluation

- Republic Vs VillasorDocument1 pageRepublic Vs VillasorNeil bryan MoninioPas encore d'évaluation

- 5 Tablarin v. GutierrezDocument1 page5 Tablarin v. GutierrezMigs GayaresPas encore d'évaluation

- 7.acosta v. AdasaDocument3 pages7.acosta v. AdasaKate Bianca CaindoyPas encore d'évaluation

- 4 - Sema Vs ComelecDocument3 pages4 - Sema Vs ComelecTew BaquialPas encore d'évaluation

- 3 Casibang Vs AquinoDocument3 pages3 Casibang Vs AquinoCarlota Nicolas VillaromanPas encore d'évaluation

- NACOCO Not a Government EntityDocument1 pageNACOCO Not a Government EntityHenteLAWcoPas encore d'évaluation

- PHHC v. CIR Case DigestDocument3 pagesPHHC v. CIR Case DigestNocQuisaotPas encore d'évaluation

- Francisco v. House of RepresentativesDocument3 pagesFrancisco v. House of RepresentativesRaymond RoquePas encore d'évaluation

- Teodoro Abueva, Et Al Vs Leonard Wood, Et Al G.R. No. L-21327 January 14, 1924Document1 pageTeodoro Abueva, Et Al Vs Leonard Wood, Et Al G.R. No. L-21327 January 14, 1924John AmbasPas encore d'évaluation

- Digested Cases 1-10 StatconDocument2 pagesDigested Cases 1-10 StatconLeayza Sta Maria CarreonPas encore d'évaluation

- LORENZO M. TAÑADA and DIOSDADO MACAPAGAL 1Document2 pagesLORENZO M. TAÑADA and DIOSDADO MACAPAGAL 1Christine GelPas encore d'évaluation

- Court rules on effect of repealing law on pending caseDocument3 pagesCourt rules on effect of repealing law on pending caseAriza Valencia100% (1)

- La Bugal-B'laan Tribal Association, Inc. V DENR Sec - RamosDocument1 pageLa Bugal-B'laan Tribal Association, Inc. V DENR Sec - RamosMax RamosPas encore d'évaluation

- Genuine Necessity - PEPITODocument4 pagesGenuine Necessity - PEPITOMike KryptonitePas encore d'évaluation

- MILAGROS E vs. AmoresDocument3 pagesMILAGROS E vs. AmoresJoyce Sumagang ReyesPas encore d'évaluation

- Gudani v. SengaDocument2 pagesGudani v. SengaIkangApostolPas encore d'évaluation

- Statcon Cases 7-12Document8 pagesStatcon Cases 7-12Frances Grace DamazoPas encore d'évaluation

- Pamatong-v-COMELEC-FerrarisDocument2 pagesPamatong-v-COMELEC-FerrarissayyedPas encore d'évaluation

- Miquiabas vs. Commanding General (GR No. l1988, February 24, 1948)Document1 pageMiquiabas vs. Commanding General (GR No. l1988, February 24, 1948)Jolo CoronelPas encore d'évaluation

- NACOCO Not a Government EntityDocument2 pagesNACOCO Not a Government Entitykent kintanarPas encore d'évaluation

- Gallego Vs VerraDocument3 pagesGallego Vs VerraDiannePas encore d'évaluation

- Republic V Judge of CFI of RizalDocument1 pageRepublic V Judge of CFI of RizalQueenie BoadoPas encore d'évaluation

- In The Matter of The IBP Membership Dues Delinquency of Atty. MARCIAL A. EDILION - (3 20 2018) - PROSPER DELOS SANTOSDocument2 pagesIn The Matter of The IBP Membership Dues Delinquency of Atty. MARCIAL A. EDILION - (3 20 2018) - PROSPER DELOS SANTOSjoshuarus favorPas encore d'évaluation

- CA Reverses RTC, Orders Eviction of Homeowners for Unpaid EquityDocument4 pagesCA Reverses RTC, Orders Eviction of Homeowners for Unpaid EquityKristell FerrerPas encore d'évaluation

- G.R. No. 103119 Intod vs. CADocument4 pagesG.R. No. 103119 Intod vs. CAMichelle Montenegro - Araujo100% (1)

- G.R. No. L-9726 US V.S. TaylorDocument5 pagesG.R. No. L-9726 US V.S. TaylorNaezel BaronPas encore d'évaluation

- HRET Ruling on Party-List Rep Qualifications OverturnedDocument2 pagesHRET Ruling on Party-List Rep Qualifications OverturnedChristopher AdvinculaPas encore d'évaluation

- City of Baguio vs. MarcosDocument2 pagesCity of Baguio vs. MarcosLance LagmanPas encore d'évaluation

- Case Digest: Imbong vs. COMELEC (35 SCRA 28)Document5 pagesCase Digest: Imbong vs. COMELEC (35 SCRA 28)Bea CapePas encore d'évaluation

- Republic of The Philippines vs. Villasor GR No. L 30671Document2 pagesRepublic of The Philippines vs. Villasor GR No. L 30671Zonix Lomboy100% (4)

- Salenilla V ComelecDocument2 pagesSalenilla V ComelecJohnson YaplinPas encore d'évaluation

- Meyer v. Nebraska Case DigestDocument2 pagesMeyer v. Nebraska Case DigestAshreabai Kam SinarimboPas encore d'évaluation

- 49 Scra 105Document2 pages49 Scra 105Johnny EnglishPas encore d'évaluation

- Garcia Vs BOI Sec 19 of Art 2Document2 pagesGarcia Vs BOI Sec 19 of Art 2Carlota Nicolas VillaromanPas encore d'évaluation

- 16 - in The Matter of Save The Supreme CourtDocument2 pages16 - in The Matter of Save The Supreme CourtNice RaptorPas encore d'évaluation

- People vs. Orita, G.R. No. 88724. April 3, 1990Document3 pagesPeople vs. Orita, G.R. No. 88724. April 3, 1990Anna BarbadilloPas encore d'évaluation

- People v. GozoDocument1 pagePeople v. GozoReymart-Vin MagulianoPas encore d'évaluation

- People V GozoDocument2 pagesPeople V GozoSomers100% (1)

- Agner Vs BPIDocument5 pagesAgner Vs BPIJacinto Jr JameroPas encore d'évaluation

- Chamber vs. Romulo 614 SCRA 605 2010Document17 pagesChamber vs. Romulo 614 SCRA 605 2010Jacinto Jr JameroPas encore d'évaluation

- Property CasesDocument7 pagesProperty CasesJacinto Jr JameroPas encore d'évaluation

- Africa vs. Caltex L-12986 (TORTS)Document1 pageAfrica vs. Caltex L-12986 (TORTS)Jacinto Jr Jamero100% (1)

- HusseinDocument5 pagesHusseinWilsonPas encore d'évaluation

- Diaz vs. Secretary of Finance - VAT on Toll FeesDocument2 pagesDiaz vs. Secretary of Finance - VAT on Toll FeesCayen Cervancia CabiguenPas encore d'évaluation

- REGALA Vs SandiganbayanDocument16 pagesREGALA Vs SandiganbayanJacinto Jr JameroPas encore d'évaluation

- PEOPLE Vs Sandiganbayan GR# 115439-41Document8 pagesPEOPLE Vs Sandiganbayan GR# 115439-41Jacinto Jr JameroPas encore d'évaluation

- Notes On Jurisdiction of CourtsDocument7 pagesNotes On Jurisdiction of CourtsJacinto Jr Jamero100% (1)

- Hickman v Taylor Work Product DoctrineDocument4 pagesHickman v Taylor Work Product DoctrineJacinto Jr JameroPas encore d'évaluation

- Lee vs. CA GR No. L - 37135Document7 pagesLee vs. CA GR No. L - 37135Jacinto Jr JameroPas encore d'évaluation

- Lee vs. CA GR No. L - 37135Document7 pagesLee vs. CA GR No. L - 37135Jacinto Jr JameroPas encore d'évaluation

- Montesclaros vs. Comelec, G.R. No. 152295, July 9, 2002Document6 pagesMontesclaros vs. Comelec, G.R. No. 152295, July 9, 2002Jacinto Jr JameroPas encore d'évaluation

- Diaz vs. Secretary of Finance - VAT on Toll FeesDocument2 pagesDiaz vs. Secretary of Finance - VAT on Toll FeesCayen Cervancia CabiguenPas encore d'évaluation

- Villa Rey Transit v. FerrerDocument8 pagesVilla Rey Transit v. FerrerJacinto Jr JameroPas encore d'évaluation

- People V TandoyDocument6 pagesPeople V TandoyJacinto Jr JameroPas encore d'évaluation

- Villa Rey Transit v. FerrerDocument8 pagesVilla Rey Transit v. FerrerJacinto Jr JameroPas encore d'évaluation

- Mitmug Vs Comelec - DigestDocument1 pageMitmug Vs Comelec - DigestJacinto Jr JameroPas encore d'évaluation

- Tax TablesDocument4 pagesTax TablesJacinto Jr JameroPas encore d'évaluation

- People V TandoyDocument6 pagesPeople V TandoyJacinto Jr JameroPas encore d'évaluation

- People Vs TanDocument2 pagesPeople Vs TanJacinto Jr JameroPas encore d'évaluation

- G.R. No. 83907. September 13, 1989. NAPOLEON GEGARE, PetitionerDocument4 pagesG.R. No. 83907. September 13, 1989. NAPOLEON GEGARE, PetitionerØbęy HårryPas encore d'évaluation

- De Vera v. AguilarDocument3 pagesDe Vera v. AguilarJacinto Jr JameroPas encore d'évaluation

- RA 7432 - Senior Citizens ActDocument5 pagesRA 7432 - Senior Citizens ActChristian Mark Ramos GodoyPas encore d'évaluation

- Tax RateDocument10 pagesTax RateErwin Dave M. DahaoPas encore d'évaluation

- BIR RR 07-2003Document8 pagesBIR RR 07-2003Brian BaldwinPas encore d'évaluation

- Marcos Asset Dispute: 9th Circuit Applies "Act of State" DoctrineDocument4 pagesMarcos Asset Dispute: 9th Circuit Applies "Act of State" DoctrineJacinto Jr JameroPas encore d'évaluation

- Philsec vs. Ca - FullDocument6 pagesPhilsec vs. Ca - FullERNIL L BAWAPas encore d'évaluation

- Yessesin-Volpin V Novosti Press Agency - DIGESTDocument2 pagesYessesin-Volpin V Novosti Press Agency - DIGESTJacinto Jr JameroPas encore d'évaluation

- A.W. Fluemer vs. Annie Hix, G.R. No. L-32636, March 17, 1930Document1 pageA.W. Fluemer vs. Annie Hix, G.R. No. L-32636, March 17, 1930Sarah Jane-Shae O. SemblantePas encore d'évaluation

- Inflatable Packers enDocument51 pagesInflatable Packers enDavid LuhetoPas encore d'évaluation

- Peter Wilkinson CV 1Document3 pagesPeter Wilkinson CV 1larry3108Pas encore d'évaluation

- Take Private Profit Out of Medicine: Bethune Calls for Socialized HealthcareDocument5 pagesTake Private Profit Out of Medicine: Bethune Calls for Socialized HealthcareDoroteo Jose Station100% (1)

- 4.5.1 Forestry LawsDocument31 pages4.5.1 Forestry LawsMark OrtolaPas encore d'évaluation

- Royal Enfield Market PositioningDocument7 pagesRoyal Enfield Market PositioningApoorv Agrawal67% (3)

- Department of Ece Vjec 1Document29 pagesDepartment of Ece Vjec 1Surangma ParasharPas encore d'évaluation

- Mini Ice Plant Design GuideDocument4 pagesMini Ice Plant Design GuideDidy RobotIncorporatedPas encore d'évaluation

- Corruption in PakistanDocument15 pagesCorruption in PakistanklutzymePas encore d'évaluation

- Rencana Pembelajaran Semester Sistem Navigasi ElektronikDocument16 pagesRencana Pembelajaran Semester Sistem Navigasi ElektronikLastri AniPas encore d'évaluation

- Terms and Condition PDFDocument2 pagesTerms and Condition PDFSeanmarie CabralesPas encore d'évaluation

- Bill of ConveyanceDocument3 pagesBill of Conveyance:Lawiy-Zodok:Shamu:-El80% (5)

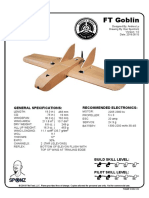

- FT Goblin Full SizeDocument7 pagesFT Goblin Full SizeDeakon Frost100% (1)

- Ralf Behrens: About The ArtistDocument3 pagesRalf Behrens: About The ArtistStavros DemosthenousPas encore d'évaluation

- Mayor Byron Brown's 2019 State of The City SpeechDocument19 pagesMayor Byron Brown's 2019 State of The City SpeechMichael McAndrewPas encore d'évaluation

- Credentials List with Multiple Usernames, Passwords and Expiration DatesDocument1 pageCredentials List with Multiple Usernames, Passwords and Expiration DatesJOHN VEGAPas encore d'évaluation

- High Altitude Compensator Manual 10-2011Document4 pagesHigh Altitude Compensator Manual 10-2011Adem NuriyePas encore d'évaluation

- 158 Oesmer Vs Paraisa DevDocument1 page158 Oesmer Vs Paraisa DevRobelle Rizon100% (1)

- Ieee Research Papers On Software Testing PDFDocument5 pagesIeee Research Papers On Software Testing PDFfvgjcq6a100% (1)

- Sav 5446Document21 pagesSav 5446Michael100% (2)

- Palmetto Bay's Ordinance On Bird RefugeDocument4 pagesPalmetto Bay's Ordinance On Bird RefugeAndreaTorresPas encore d'évaluation

- 13-07-01 Declaration in Support of Skyhook Motion To CompelDocument217 pages13-07-01 Declaration in Support of Skyhook Motion To CompelFlorian MuellerPas encore d'évaluation

- Enerflex 381338Document2 pagesEnerflex 381338midoel.ziatyPas encore d'évaluation

- PS300-TM-330 Owners Manual PDFDocument55 pagesPS300-TM-330 Owners Manual PDFLester LouisPas encore d'évaluation

- Product Manual 36693 (Revision D, 5/2015) : PG Base AssembliesDocument10 pagesProduct Manual 36693 (Revision D, 5/2015) : PG Base AssemblieslmarcheboutPas encore d'évaluation

- Code Description DSMCDocument35 pagesCode Description DSMCAnkit BansalPas encore d'évaluation

- Miniature Circuit Breaker - Acti9 Ic60 - A9F54110Document2 pagesMiniature Circuit Breaker - Acti9 Ic60 - A9F54110Gokul VenugopalPas encore d'évaluation

- Question Paper Code: 31364Document3 pagesQuestion Paper Code: 31364vinovictory8571Pas encore d'évaluation

- 2JA5K2 FullDocument22 pages2JA5K2 FullLina LacorazzaPas encore d'évaluation

- Trinath Chigurupati, A095 576 649 (BIA Oct. 26, 2011)Document13 pagesTrinath Chigurupati, A095 576 649 (BIA Oct. 26, 2011)Immigrant & Refugee Appellate Center, LLCPas encore d'évaluation

- Lorilie Muring ResumeDocument1 pageLorilie Muring ResumeEzekiel Jake Del MundoPas encore d'évaluation