Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Original Article - Cancer in Children

Transféré par

Adienda PutriTitre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Original Article - Cancer in Children

Transféré par

Adienda PutriDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Pediatric Hematology and Oncology, 29:335344, 2012

Copyright C

Informa Healthcare USA, Inc.

ISSN: 0888-0018 print / 1521-0669 online

DOI: 10.3109/08880018.2012.670368

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Use Of Complementary and Alternative Medicine in

Children With Cancer: Effect on Survival

Yasin Karal, MD,

1

Metin Demirkaya, MD,

2

and Bet ul Sevinir, MD

2

1

Department of Pediatrics, Uludag University, Medical Faculty, Bursa, Turkey;

2

Division of

Pediatric Oncology, Department of Pediatrics, Uludag University, Medical Faculty, Bursa,

Turkey

The objective of the present study was to determine the type, frequency, the reason why com-

plementary and alternative medicine (CAM) treatments are used, the factors related with their

use, and the eects of CAM usage on long-term survival. Families of a total of 120 children with

cancer between 018 years of age, including 50 (41.7%) girls and 70 (58.3%) boys, participated in

our study. The authors found that 88 patients (73.3%) used at least one CAM method, the most

common (95.5%) of which was biologically based therapies. Most frequently used biologically

based therapies were dietary supplements and herbal products. The most commonly used di-

etary supplement or herbal product was honey (43.2%) or stinging nettle (43.2%), respectively.

We found that patients used such CAM methods as complementary to, but not instead of, con-

ventional therapy. Sixty-nine out of 88 patient families (78.4%) shared the CAMmethod they used

with their physicians. No statistically signicant relation was found between socioeconomic, so-

ciodemographic, or other factors or items and CAM use. The mean follow-up period of the CAM

users and nonusers groups was 79.4 36.7 (21.3217.9) and 90.9 50.3 (27.4193.7) months, re-

spectively. Five-year survival rates for CAM users and nonusers were found as 81.5% and 86.5%,

respectively (P > .05). In conclusion, families of children with cancer use complementary and al-

ternative treatment frequently. They do not attempt to replace conventional treatment with CAM.

Higher rates of CAM use was found in families with higher educational level. CAM usage did not

aect the long-term survival.

Keywords alternative treatment, cancer, children, complementary medicine

Complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) treatments are defned as medi-

cal health care systems, practices, and products that are not considered a part of con-

ventional treatment [1].

Te US National Institute of Health Center for Complementary and Alternative

Medicine (NCCAM) classifed CAM treatments in 5 categories: (i) alternative med-

ical systems (such as homeopathy or traditional Chinese medicine); ii) mind-body

medicine (activities suchas meditation, prayer, art, dance, andmusic); iii) biologically

based therapies (such as plants, diet supplements); (iv) manipulative and body-based

therapies (such as chiropractic message); and (v) energy therapies (such as Qi gong,

Reiki, healing touch) [2].

CAM treatments are mostly used to decrease the side efects of traditional cancer

treatment. Unfavorable prognosis, previous use of CAM treatment, parents with high

Received 29 September 2011; accepted 23 February 2012.

Address correspondence to Metin Demirkaya, MD, Division of Pediatric Oncology, Department of

Pediatrics, Uludag University, Medical Faculty, 16059 G or ukle, Bursa, Turkey. E-mail:

demirkayametin@hotmail.com

{{,

{{ Y. Karal et al.

educational level, advanced age, and religious belief are factors associated with the

use of CAM treatment in children with cancer [3].

Te prevalence of CAMis reported to be between 24%and 90%in these patients. In

various studies, it was established that CAM treatments were used as complementary

to conventional treatment [3, 4]. In studies carried out in Turkey, the prevalence of us-

ingCAMtreatments has beenaround50%inpediatric patients and22%to53%inadult

patients. Te most frequently used method is treatment with plants, most commonly

the stinging nettle [58].

Tere are only a fewstudies evaluating CAMusage onthe long-termsurvival incan-

cer patients [9, 10]. Tese limited data primarily include adult patients and reveal that

CAM usage does not contribute to long-term survival.

Te objective of the present study was to determine the type, frequency, the con-

tributing factors, and the efect on long-term survival of CAM treatment in children

with cancer.

METHODS

Tis study was carried out between July 2007 and October 2007 with parents of pedi-

atric patients (aged0to18years) inthePediatric Oncology Department of UludagUni-

versity Hospital. However, the patient population was followed up for approximately

4 years to evaluate the efect of CAM on long-term survival.

CAM treatments were defned as any treatment not included in the biomedical

framework in the management of cancer patients. Patients families were frst in-

formed about CAM, and then about the study. Te questionnaire developed for the

study was completed by either one or both of the parents.

Te questionnaire was divided into the following parts: (i) sociodemographic data

(eg, age, sex, occupation of the parents, monthly income of the family, educational

level of the parents, number of siblings, social security, and place of residence); (ii)

information on the disease (diagnosis, date of the diagnosis, cancer history in family

members, treatments administered to the patient, etc); (iii) the use of CAM and the

methods used; (iv) the reason for the use of CAM; (v) time of initiating CAM use; (vi)

expected benefts and/or side efects of CAM; (vii) physician awareness of the familys

use of CAM; and (viii) changes in the way of life of the family after the diagnosis of

cancer.

Educational status of the family was classifed into 4 groups: (i) no school atten-

dance; (ii) primary or secondary school; (iii) high school graduate; and (iv) university

graduate.

Families with monthly income lower than 500 Turkish Liras (TL) were classifed as

low income, those between 500 and 1000 TL as middle income, and those over 1000

TL as high income according to poverty limits of Turkish Institution of Statistic.

Demography of the families was classifed into province, county, and rural areas.

Te study was approved by the ethical committee of Uludag University. Written in-

formed consent was obtained from either or both of the parents of cancer patients

participating in the study.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 13.0 for Windows (SPSS, Chicago, IL,

USA) software. Categorical variables were given with mean, standard deviation, and

minimummaximum values. Te Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used if continuous

variables were distributed normally. Te intergroup comparison of variables dis-

tributed normally was carried out with an independent t test; comparison of the vari-

ables not distributed normally was carried out with the Mann-Whitney U test. In

Pediatric Hematology and Oncology

Complementary and Alternatlve Vedlclne {{;

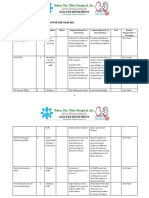

TABLE 1 Distribution of Diagnosis (n =120)

Diagnosis n (%)

Lymphoma 47 (39.2)

Non-Hodgkin lymphoma 33 (27.5)

Hodgkin lymphoma 14 (11.7)

Nervous system tumors 30 (25)

CNS tumor 24 (20)

Neuroblastoma 6 (5)

Sarcoma 16 (13.3)

Soft tissue sarcomas 9 (7.5)

Bone sarcomas 7 (5.8)

Wilms tumor 14 (11.7)

Other 13 (10.8)

Note. CNS =central nervous system.

the intergroup comparison of categorical variables, a chi-square test was used. Te

Kaplan-Meier test was used for survival analysis. Survival periods were compared be-

tween groups by a log-rank test. P value of <.05 was considered signifcant.

RESULTS

One hundred twenty parents of pediatric patients participated in the study. Question-

naires were answered, 74 (61%) by only the mothers, 32 (26.7%) by only fathers, and

14 (11.7%) by both parents together.

When the study was initiated, treatment of 69 patients (57.5%) was completed and

that of 51patients (42.5%) was continuing. Of thelatter, 15(12.5%) werereceivingtreat-

ment for cancer relapse. Table 1 shows the distribution of the diagnoses.

Of 120 patients included in the study, 88 (73.3%) were found to use a method of

CAM. Table 2 shows the classifcation of CAM treatment into major groups and man-

ner of use.

TABLE 2 Te Distribution of CAM Use Within Major Groups of CAM and Mode of Use

n (%)

CAM group

Biologically based therapies 84 (95.5)

Mind-body practices 38 (43.2)

Manipulative and body-based methods 2 (2.3)

Energy therapies 2 (2.3)

Alternative medical systems 0 (0)

Modes of use of CAM

Only biologically based therapy 49 (55.7)

Mind-body practice +biologically based therapy 32 (36.4)

Only mind-body practices 4 (4.6)

Mind-body practice +biologically based therapy +manipulative and body-based

therapies

1 (1.1)

Mind-body practice +biologically based therapy +energy therapies 1 (1.1)

Mind-body practice +biologically based therapy +manipulative and body-based

therapies +energy therapies

1 (1.1)

Note. CAM=complementary and alternative medicine.

More than 1 answer.

Percentage was calculated over 88 patients using CAM.

Copyrlght C

lnforma lealthcare uSA, lnc.

{{8 Y. Karal et al.

Of families using CAM, 53 (60%) stated that they began after the disease was con-

trolled, 32 (36.3%) chose to do so from the moment of diagnosis, and 3 (3.7%) began

when the disease recurred.

Of CAM methods, biologically based treatments were the most commonly used

(95.5%). Of the biologically based treatments, 51 patients (58%) used an herbal treat-

ment, to which 45 of these patients added at least one food or drink. Of herbal prod-

ucts, 38 patients (43.2%) used stinging nettle and 25 (28.4%) drank herbal teas. Other

frequently usedproducts of plant originwere rose hip, black seed, artichoke, andbroc-

coli. In addition to herbal products, the most frequently ingested products in decreas-

ing order of frequency were honey (43.2%), grape molasses (28.4%), and bee pollen

(18.2%). Bee milk, carob molasses, and mulberry molasses were also commonly used

products. Four other patients used metabolic products containing gluconate-cesium,

dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), shark cartilage, and turtle blood, respectively.

Tirty-eight families (43.2%) used body-mind practices such as oferings, animal

sacrifce, amulets, referring to a prayer leaders, and visiting tombs.

Two families (2.3%) did exercise and other activities such as manipulative body

treatment.

Two families (2.3%) referred to a bioenergy center for energy therapy.

No patients used alternative medical systems such as homeopathy, naturopathy,

Ayurveda, or Chinese medicine.

Stated reasons for using CAM included obtaining better blood values (23 families,

26.1%), improvement ingeneral condition(20 families, 22.7%), pressure fromrelatives

(17 families, 19.3%), and to ease the conscience (12 families, 13.6%).

Of families who used and claimed beneft from CAM, 25 (28.4%) stated that

blood values of their children increased, 23 (26.1%) stated that appetite increased, 16

(18.1%) stated that general conditionimproved, and16 (18.1%) statedthat morale was

boosted. None observed any side efects from the use of CAM.

Of families using CAM, 53 (60.2%) changed their nutritional habits, and 74 (84.1%)

started to protect their children from exposure to cigarette smoke. Parents in 13

(14.8%) families started to smoke due to anxiety and/or stress. In 17 families (19.2%),

religious practices increased. Only 4 families experienced no change in lifestyle.

When comparing families using CAM to those who do not, no signifcant difer-

ence was found in terms of the age of parents, age of patients, and number of siblings

(P >.05) (Table 3).

Tables 4 and 5 show sociodemographic and other factors efecting CAM usage.

Tere were no statistically signifcant diference between those who used CAM and

those who do not with respect to sociodemographic (educational levels of parents

and place of residence) and other (diagnosis, treatment, recurrence, cancer history

in the family, belief in recovery, and confdence in medical treatment) factors (P >

.05). Table 6 demonstrates the relation between socioeconomic variables and the use

TABLE 3 Use of CAM With Regard to Ages of Patients, Mothers, and Fathers, and Number of

Siblings

CAM use

Age of the patient

(year)

Age of the mother

(year)

Age of the father

(year)

Number of

siblings

Yes (n =88) 8.7 (218) 35.0 (2350) 38.0 (2455) 1.0 (06)

No (n =32) 10.0 (0.518) 35.0 (2350) 37.5 (2753) 1.0 (06)

P >.05 >.05 >.05 >.05

Note. CAM=complementary and alternative medicine.

Median (minmax).

Pediatric Hematology and Oncology

Complementary and Alternatlve Vedlclne {{

TABLE 4 Sociodemographic Variables and the Use of CAM

Te use of CAM

Yes No

n (%) n (%)

Mothers education level

Primary or secondary school 67 (76.1) 23 (71.9)

High school 12 (13.6) 5 (15.6)

No education 5 (5.7) 3 (9.4)

University 4 (4.5) 1 (3.1)

P >.05 >.05

Fathers education level

Primary or secondary school 53 (60.2) 23 (71.9)

High school 19 (21.6)

University 16 (18.2) 2 (6.2)

No education 0 0

P >.05 >.05

Place of residence

Providence 46 (52.3) 16 (50.0)

County 31 (35.2) 12 (37.5)

Rural area (town, village, etc) 11 (12.5) 4 (12.5)

P >.05 >.05

Note. CAM=complementary and alternative medicine.

of CAM. Te working status of parents and socioeconomic status of the family did not

change the CAM usage (P >.05)

Te mean follow-up period of the using CAM and other groups was 79.4 36.7

(21.3217.9) and 90.9 50.3 (27.4193.7) months, respectively. Tere was no statisti-

cally signifcant diferenceinfollow-uptimes betweenthe2groups. Whensurvival was

analyzed, the overall survival at the end of 5 years of follow-up was 81.5% and 86.5%

for the CAM users and nonusers, respectively (P >.05) (Figure 1).

250,00 200,00 150,00 100,00 50,00 0,00

time (months)

1,0

0,8

0,6

0,4

0,2

0,0

S

u

r

v

i

v

a

l

users

nonusers

FIGURE 1 Overall survival of CAM users and nonusers.

Copyrlght C

lnforma lealthcare uSA, lnc.

{|o Y. Karal et al.

TABLE 5 Other Factors or Items and the Use of CAM

Te use of CAM

Yes No

n (%) n (%)

Diagnosis group

Lymphoma 35 (39.8) 12 (37.5)

Nervous system tumors 21 (23.9) 9 (28.1)

Sarcomas 10 (11.4) 6 (18.7)

Wilms tumor 12 (13.6) 2 (6.2)

Others 10 (11.4) 3 (9.4)

P >.05 >.05

Treatment status

Finished 49 (55.7) 20 (62.5)

Ongoing 39 (44.3) 12 (37.5)

P >.05 >.05

Status of recurrence

No 80 (90.9) 25 (78.1)

Yes 8 (9.1) 7 (21.9)

P >.05 >.05

Treatment administered

Chemotherapy 84 (95.5) 29 (90.6)

Surgery 50 (56.8) 22 (68.7)

Radiotherapy 42 (47.7) 11 (34.4)

Cancer history in the family

Absent 46 (52.3) 23 (71.9)

Present 42 (47.7) 9 (28.1)

P >.05 >.05

Belief in recovery

Yes 79 (89.8) 29 (90.6)

No idea 3 (3.4) 2 (6.2)

Partly 4 (4.5) 0 (0)

No 2 (2.3) 1 (3.1)

Confdence in medical treatment

Yes 83 (94.3) 31 (96.9)

Partly 4 (4.5) 1 (3.1)

No idea 1 (1.1) 0 (0)

No 0 (0) 0 (0)

Note. CAM=complementary and alternative medicine.

TABLE 6 Socioeconomic Variables and the Use of CAM

Te use of CAM

Yes No

n (%) n (%)

Working status of the mother (n =118)

Housewife 77 (88.5) 29 (93.5)

Works 10 (11.5) 2 (6.5)

P >.05 >.05

Working status of the father (n =118)

Works 83 (95.4) 27 (87.1)

Retired (does not work) 4 (4.6) 4 (12.9)

P >.05 >.05

Socioeconomic status

Medium 54 (61.4) 17 (53.1)

High 24 (27.2) 7 (21.9)

Low 10 (11.4) 8 (25.0)

P >.05 >.05

Note. CAM=complementary and alternative medicine.

Pediatric Hematology and Oncology

Complementary and Alternatlve Vedlclne {|+

DISCUSSION

In pediatric oncology patients, CAM is commonly employed by the families. Parents

administer CAMtreatment basedoninformationobtainedfromfamily, friends, or the

Internet rather than that obtained from health care providers. CAM use is generally

kept secret fromphysicians administering conventional treatment. CAMmethods are

a source of concern for oncologists, as they are usually used without being subjected

to investigations [11].

Although survival rates from childhood cancer have recently increased, it is still

a cause of mortality. Incomplete information on the source of the diseaseand

physical and psychological symptoms emerging during conventional treatmentled

the children and their families to seek diferent treatment approaches. Te use of

CAM treatments in pediatric cancer patients varies from country to country and

is reported to range from 24% to 90% [3, 4, 12]. In a 1970s study carried out in the

USA, rate of the use of CAM treatment was found to be 9%, with recently determined

regional diferences ranging from 18% to 84% [1214]. Te corresponding rates in the

other 2 countries of North America were found to be 42.649% and 70% in Canada

and Mexico, respectively [1517]. In studies carried out in Europe, for example, in

Germany and England, the rates were found around 35% [18, 19]. In the study of

Grootenhuis et al in the Netherlands [20], the use of CAM was found to be higher in

patients with relapsing disease (46%) than in those in remission (16%). In Southeast

Asian countries still under the infuence of traditional Chinese medicine, the rates of

CAM use are higher, being 67% and 73% in Singapore and Taiwan, respectively [21,

22]. Tese data indicate that CAM methods are used at diferent rates in diferent

countries and that recently the administration of CAM has tended to be increased.

Two diferent studies performed in 1999 and 2004 in diferent parts of Turkey show

the use of CAM to be around 50% in this patient population [5, 6]. In the present

study, which was performed in 2007, the rate of the use of at least one CAM method

was found to be higher (73.3%) compared with other studies carried out in Turkey

and other countries. Since approximately two third of the population in our region

has been reported to be moved from other regions of Turkey, we believe that our

fgures represent the general pediatric oncology patient of Turkey. Te noticeably

large diferences in the rates of the use of CAM between diferent countries may

be ascribed to methodological diferences plus the lack of standard defnitions and

criteria for CAM. In addition, individual factors and sociocultural characteristics of

the style and adequacy of health services also infuence the rates of CAM use.

CAM methods vary by country, geographical region, ethnic group, socioeconomic

status, and religion [7]. Herbal treatment and nutritional supplements are most

frequently used CAM methods. Mind-body practices such as belief therapy, imagina-

tion, hypnosis, meditation and spiritual recovery, relaxation therapy, aromatherapy,

music, and massage therapy are among the CAM practices established in various

studies. Other CAM options include homeopathy, naturopathy, acupuncture, chiro-

practic, and reiki [12, 1417, 19, 20, 2327]. In the evaluation of the world as a whole,

the most frequently used CAM methods are praying, exercise, and spiritual recovery

[24]. Cancer centers in England most frequently used multivitamins, aromatherapy

massage, diet, and music [19]. For children in Australia, relaxation through hyp-

notherapy and similar imaging techniques is the CAM treatment most commonly

used [28]. In Canada, the rate of the use of chiropractic, homeopathy, naturopathy,

and acupuncture is 84% [29].

CAM methods used in western countries show great variance elsewhere. In

Pakistan, herbal therapy is the most commonly used [30]. Southeast Asians prefer

alterations in diet or packaged fuids or powders to enhance the immune system

Copyrlght C

lnforma lealthcare uSA, lnc.

{|: Y. Karal et al.

(48%) or alterations in diet. Spiritual and traditional Chinese medicine is also used

commonly [21, 22]. In Turkey, Karadeniz et al [6] reported that the most frequently

used CAM method in children with cancer was biologically based therapy, with a

rate of 71.4% (mostly stinging nettle, but also plant essences and Anzer honey, a

honey specifc to the Anzer region in the Black Sea), followed by belief therapy at

40.8% (prayer, oferings, and tomb visits). In the study of G oz um et al [5], herbal

products were the most frequently used methods in Erzurum in eastern Turkey

(90.7%), usually stinging nettle and its seed. In the present study, the most commonly

used complementary and alternative therapies were dietary supplements and herbal

products. Of patients using CAM, 86.3%used at least one dietary supplement (food or

drink other than herbal medicine), whereas 58% used at least one herbal product. Of

dietary supplements, the most commonly usedwere honey, molasses, andbee pollen.

Te most preferred herbal product was stinging nettle (43.2%), followed by herbal

teas (33.3%). Mind-body practices (ofering, sacrifcing animals, amulets, referring to

prayer leader, visiting tombs, etc) were the secondmost frequently usedCAMmethod.

Temost commonreasonfor usingCAMwas toprevent thefall inbloodvalues after

chemotherapy. A 14.1%of the families stated that they used CAMbecause of pressure

fromclose relatives. Indeed, the rate of the use of CAMwas higher among those whose

relatives have a history of cancer (82.3%vs 66.7%). In the study of Fernandez et al [15],

including366families, reasons oferedfor usingCAMwas toenhancetheimmunesys-

tem and the general health condition of the cancer patient. Additional reported aims

were to cure the cancer, to obtain a cure with fewer problems and complications, and

to slowthe progression of the disease. In many other studies, the reasons for CAMuse

were reported to be similar [5, 6, 12, 17, 19, 2123, 25, 26].

In the present study, no serious efects of CAM use were reported, although some

plants may lead to side efects in children whose conventional treatment continued.

For example, when used concurrently with grapefruit, the efect of steroids, irinote-

cans, some chemotherapy agents, and calciumchannel blockers may vary [31]. Other

side afects of herbal therapies as reported by Ernst [32] were bradycardia, brain dam-

age, cardiogenic shock, diabetic coma, encephalopathy, heart rupture, intravascular

hemolysis, liver failure, respiratory failure, toxic hepatitis, and death.

Te present study established that patients used CAM methods to supplement but

not replace conventional treatment, which is similar to the fndings of other studies

carried out in Turkey [5, 6]. In the study of Fernandez et al [15], only 8 of 366 families

used CAMinstead of conventional treatment. Inanother study with44 families partic-

ipating, only 1 used CAM as an alternative to conventional treatment [23].

In various studies, rates of how often families admitted to their physicians that

they used CAM ranged from 9% to 92% [5, 6, 12, 15, 18, 21, 24, 28]. In the present

study, 78.4%of the families using CAMinformed their physicians of the methods they

usedbecause the families of patients were asked to clearly state CAM use. Family

members were then informed as to possible side efects.

Te rate of CAMuse incancer patients was foundtobe higher among those patients

whose parents are employed and/or university graduates. Because the majority was

at a low educational and economic level, however, the diference between parents in

terms of the above rates was not signifcant.

Studies evaluating the efect of CAM usage on overall survival are limited and gen-

erally performed in adult patients. Risberg et al [9] investigated the efect of alterna-

tive medicine (AM) on the long-term survival in their study with a follow-up period

of 8 years, including 515 cancer patients aged above 15 years and found that death

rates were higher in AM users (79%) than in those who did not use AM (65%). Sen-

sitivity analyses strengthened the negative association between AM use and survival.

Tey concluded that the use of AM seems to predict a shorter survival from cancer.

Pediatric Hematology and Oncology

Complementary and Alternatlve Vedlclne {|{

Richardsonet al [10] reportedthat of the 342cancer patients attending 2diferent CAM

clinics (approximately 60% of whom attended after surgery, chemotherapy, or radio-

therapy), only 16.8%survivedat the endof 5years. Buiatti et al [33] reportedthat 5-year

survival rate in 248 pediatric and adult leukemia patients receiving Di Bella multither-

apy (MDB), whichis analternative treatment method, was 29.4%. Tis ratio was found

as statistically lower than those of the patients included in Italian Cancer Registry.

Our study is one of the very limited numbers of studies investigating the relation-

ship between CAM usage and survival rates. In PubMed database, we were unable to

detect any study evaluating the efect of CAM usage on long-term survival in children

withlymphoma or solidtumors. Although5-year survival rate was lower inCAMusers

thannonusers, this was statistically insignifcant. Our patients usedat least one of con-

ventional treatment modalities including surgery, chemotherapy, and radiotherapy.

For this reason, we were reasonably unable to compare the patients solely using CAM

with those solely using conventional treatments.

Inconclusion, the rates andmethods of CAMuse inour patients difer fromthose in

Western countries. Our data indicate that around 75% of our patients use at least one

method of CAM, most commonly therapies that are biologically based (dietary sup-

plements and herbal products). Our fgures suggest that CAM use in our country has

increasedrecently. None of our patients employedCAMtoreplace conventional treat-

ment owingtotheconfdenceinconventional treatments andtothebelief intheharm-

lessness of CAM when used in conjunction with conventional treatments. It was also

established that CAM was used at higher rates in members of families with a profes-

sion and/or high educational level. Informing the families about CAM will contribute

tothe regular use of conventional treatment. Generally usedinadditiontothe conven-

tional treatments, CAM usage does not seem to contribute on the long-term survival

in pediatric cancer patients.

Declaration of Interest

Te authors report no conficts of interest. Te authors alone are responsible for the

content and writing of the paper.

REFERENCES

[1] Kelly KM. Bringing evidence to complementary and alternative medicine in children with cancer:

focus on nutrition-related therapies. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2008;50:490493.

[2] National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine. What Is Complementary and Alter-

native Medicine (2002). Available at: http://nccam.nih.gov/health/whatiscam/D156.pdf. Accessed

November 24, 2006.

[3] Kelly KM. Complementary and alternative medicines for use in supportive care in pediatric cancer.

Support Care Cancer. 2007;15:457460.

[4] Kelly KM. Complementary and alternative medical therapies for children with cancer. Eur J Cancer.

2004;40:20412046.

[5] G oz um S, Arikan D, Buyukavc M. Complementary and alternative medicine use in pediatric oncol-

ogy patients in eastern Turkey. Cancer Nurs. 2007;30:3844.

[6] Karadeniz C, Pinarli FG, Oguz A, et al. Complementary/alternative medicine use in a pediatric on-

cology unit in Turkey. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2007;48:540543.

[7] Samur M, Bozcuk HS, Kara A, et al. Factors associatedwithutilizationof nonprovencancer therapies

in Turkey: a study of 135 patients from a single center. Support Care Cancer. 2001;9:452458.

[8] Ceylan S, Hamzaoglu O, Komurcu S, et al. Survey of the use of complementary and alternative

medicine among Turkish cancer patients. Complement Ther Med. 2002;10:9499.

[9] Risberg T, Vickers A, Bremnes RM, et al. Does use of alternative medicine predict survival from can-

cer? Eur J Cancer. 2003;39:372377.

[10] RichardsonMA, Russell NC, Sanders T, et al. Assessment of outcomes at alternative medicine cancer

clinics: a feasibility study. J Altern Complement Med. 2001;7:1932.

Copyrlght C

lnforma lealthcare uSA, lnc.

{|| Y. Karal et al.

[11] Sencer SF, Kelly KM. Complementary and alternative therapies in pediatric oncology. Pediatr Clin

North Am. 2007;54:10431060.

[12] McCurdy EA, Spangler JG, WofordMM, et al. Religiosity is associatedwiththe use of complementary

medical therapies by pediatric oncology patients. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2003;25:125129.

[13] Faw C, Ballentine R, Ballentine L, et al. Unproved cancer remedies. A survey of use in pediatric out-

patients. JAMA. 1977;238:15361538.

[14] Nathanson I, Sandler E, Ramirez-Garnica G, et al. Factors infuencing complementary and al-

ternative medicine use in a multisite pediatric oncology practice. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol.

2007;29:705708.

[15] Fernandez CV, Stutzer CA, MacWilliamL, et al. Alternative and complementary therapy use in pedi-

atric oncology patients inBritishColumbia: prevalence andreasons for use andnonuse. J ClinOncol.

1998;16:12791286.

[16] Martel D, Bussieres JF, Teoret Y, et al. Use of alternative and complementary therapies in children

with cancer. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2005;44:660668.

[17] Gomez-Martinez R, Tlacuilo-Parra A, Garibaldi-Covarrubias R. Use of complementary and alterna-

tive medicine in children with cancer in Occidental, Mexico. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2007;49:820823.

[18] Langler A, Spix C, Gottschling S, et al. Parents-interview on use of complementary and alternative

medicine in pediatric oncology in Germany. Klin Padiatr. 2005;217:357364.

[19] Molassiotis A, Cubbin D. Tinking outside the box: complementary and alternative therapies use

in pediatric oncology patients. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2004;8:5060.

[20] Grootenhuis MA, Last BF, de Graf-Nijkerk JH, et al. Use of alternative treatment in pediatric oncol-

ogy. Cancer Nurs. 1998;21:282288.

[21] Yeh CH, Tsai JL, Li W, et al. Use of alternative therapy among pediatric oncology patients in Taiwan.

Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2000;17:5565.

[22] LimJ, Wong M, Chan MY, et al. Use of complementary and alternative medicine in paediatric oncol-

ogy patients in Singapore. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 2006;35:753758.

[23] Bold J, Leis A. Unconventional therapy use among children with cancer in Saskatchewan. J Pediatr

Oncol Nurs. 2001;18:1625.

[24] Friedman T, Slayton WB, Allen LS, et al. Use of alternative therapies for children with cancer. Pedi-

atrics. 1997;100(6):E1.

[25] Neuhouser ML, PattersonRE, Schwartz SM, et al. Use of alternative medicine by childrenwithcancer

in Washington State. Prev Med. 2001;33:347354.

[26] Fletcher PC, Clarke J. Te use of complementary and alternative medicine among pediatric patients.

Cancer Nurs. 2004;27:9399.

[27] Loman DG. Te use of complementary and alternative health care practices among children. J Pedi-

atr Health Care. 2003;17:5863.

[28] Sawyer MG, Gannoni AF, Toogood IR, et al. Te use of alternative therapies by children with cancer.

Med J Aust. 1994;160:320322.

[29] Spigelblatt L, Laine-Ammara G, Pless IB, et al. Te use of alternative medicine by children. Pediatrics.

1994;94:811814.

[30] Malik IA, Khan NA, Khan W. Use of unconventional methods of therapy by cancer patients in Pak-

istan. Eur J Epidemiol. 2000;16:155160.

[31] Marchetti S, Mazzanti R, Beijnen JH, et al. Concise review: clinical relevance of drug-drug and

herb-drug interactions mediated by the ABC transporter ABCB1 (MDR1, P-glycoprotein). Oncolo-

gist. 2007;12:927941.

[32] Ernst E. Serious adverse efects of unconventional therapies for children and adolescents: a system-

atic review of recent evidence. Eur J Pediatr. 2003;162:7280.

[33] Buiatti E, Arniani S, Verdecchia A, et al. Results from a historical survey of the survival of cancer

patients given Di Bella multitherapy. Cancer. 1999;86:21432149.

Pediatric Hematology and Oncology

Copyright of Pediatric Hematology & Oncology is the property of Taylor & Francis Ltd and its content may not

be copied or emailed to multiple sites or posted to a listserv without the copyright holder's express written

permission. However, users may print, download, or email articles for individual use.

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5794)

- Try Out Rsbi 7 S1Document7 pagesTry Out Rsbi 7 S1Adienda PutriPas encore d'évaluation

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- Lembar Penilaian Praktik Profesi MedicalDocument2 pagesLembar Penilaian Praktik Profesi MedicalAdienda PutriPas encore d'évaluation

- The Present Continuous Tense: BerlangsungDocument2 pagesThe Present Continuous Tense: BerlangsungAdienda PutriPas encore d'évaluation

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- Jurnal MP AsiDocument14 pagesJurnal MP AsiAdienda PutriPas encore d'évaluation

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (895)

- Intracranial Hypertension TherapyDocument22 pagesIntracranial Hypertension TherapydanicasoniPas encore d'évaluation

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (344)

- Present EFN IndvDocument1 pagePresent EFN IndvAdienda PutriPas encore d'évaluation

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (399)

- Nilai EfnDocument3 pagesNilai EfnAdienda PutriPas encore d'évaluation

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (588)

- Ujian ExelDocument2 pagesUjian ExelAdienda PutriPas encore d'évaluation

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- Empyema - Arkansas Children's HospitalDocument3 pagesEmpyema - Arkansas Children's HospitalAdienda PutriPas encore d'évaluation

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (266)

- Malin KundangDocument1 pageMalin KundangAdienda PutriPas encore d'évaluation

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- Apollo Gleneagles Hospitals: The Next Steps For GrowthDocument16 pagesApollo Gleneagles Hospitals: The Next Steps For Growthyashi mittalPas encore d'évaluation

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- OCR BasicOphthalmology4MedicalStudents&PrimaryCareResidents8ed2004BradfordDocument244 pagesOCR BasicOphthalmology4MedicalStudents&PrimaryCareResidents8ed2004Bradfordハルァン ファ烏山Pas encore d'évaluation

- Physical Examination Pediatric: By: Erni Setiyorini, S.Kep.,NsDocument68 pagesPhysical Examination Pediatric: By: Erni Setiyorini, S.Kep.,NsReka DwiPas encore d'évaluation

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (73)

- Kode Akses UAS Gasal 2021-2022 RegulerDocument5 pagesKode Akses UAS Gasal 2021-2022 RegulerGaluh Restuti Dyah PradwiptaPas encore d'évaluation

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- Solar ElbowDocument22 pagesSolar ElbowMihaela HerghelegiuPas encore d'évaluation

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- Maple Syrup Urine DiseaseDocument14 pagesMaple Syrup Urine DiseasefantasticoolPas encore d'évaluation

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2259)

- Long Case PaedDocument21 pagesLong Case Paedwhee182Pas encore d'évaluation

- EBNDocument5 pagesEBNyanishappyPas encore d'évaluation

- Anavar StackDocument3 pagesAnavar Stackbond99999Pas encore d'évaluation

- Puzzles SetDocument87 pagesPuzzles SetShubham ShuklaPas encore d'évaluation

- General Electric Accesorios DashDocument2 pagesGeneral Electric Accesorios DashIngridJasminTafurBecerraPas encore d'évaluation

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- Scientific Bioassay Development Potency in Philadelphia PA Resume Edward AcheampongDocument3 pagesScientific Bioassay Development Potency in Philadelphia PA Resume Edward AcheampongEdwardAcheampongPas encore d'évaluation

- 194 Surgical Cases PDFDocument160 pages194 Surgical Cases PDFkint100% (4)

- AccreditationReadiness Booklet (Version 1.0) - May 2022Document44 pagesAccreditationReadiness Booklet (Version 1.0) - May 2022Leon GuerreroPas encore d'évaluation

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1090)

- Biomechanics of The HipDocument12 pagesBiomechanics of The HipSimon Ocares AranguizPas encore d'évaluation

- PUVDocument12 pagesPUVOgechukwu NwobePas encore d'évaluation

- Fecal Exams Worming Schedules For DogsDocument1 pageFecal Exams Worming Schedules For DogsikliptikawatiPas encore d'évaluation

- Textbook of Pediatric Hematology and Hemato-OncologyDocument541 pagesTextbook of Pediatric Hematology and Hemato-OncologyAngeline Adrianne83% (6)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (120)

- Reverse Total Shoulder Arthroplasty Rehab ProtocolDocument12 pagesReverse Total Shoulder Arthroplasty Rehab Protocol張水蛙Pas encore d'évaluation

- Sajb 33263 266Document4 pagesSajb 33263 266Ezza RiezaPas encore d'évaluation

- Neuraxial Anaesthesia ComplicationsDocument7 pagesNeuraxial Anaesthesia ComplicationsParamaPutraPas encore d'évaluation

- 07 17 13Document24 pages07 17 13grapevinePas encore d'évaluation

- Growth Comparison in Children With and Without Food Allergies in 2 Different Demographic PopulationsDocument7 pagesGrowth Comparison in Children With and Without Food Allergies in 2 Different Demographic PopulationsMaria Agustina Sulistyo WulandariPas encore d'évaluation

- Lifeguarding ManualDocument405 pagesLifeguarding Manualmegan100% (3)

- SCD Insert NursingDocument2 pagesSCD Insert Nursingmihalache1977100% (1)

- The Last Innovation in Achalasia Treatment Per-Oral Endoscopic MyotomyDocument6 pagesThe Last Innovation in Achalasia Treatment Per-Oral Endoscopic MyotomyBenni Andica SuryaPas encore d'évaluation

- Staff Development Plan 2023Document5 pagesStaff Development Plan 2023SSNHI Dialysis Training CenterPas encore d'évaluation

- A Color Atlas of Orofacial Health and Disease in Children and Adolescents - ScullyDocument241 pagesA Color Atlas of Orofacial Health and Disease in Children and Adolescents - ScullyHameleo1000100% (3)

- Autopathic Bottle Instruction BreathDocument1 pageAutopathic Bottle Instruction BreathjivinaPas encore d'évaluation

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)

- Dental CariesDocument19 pagesDental CariesTesisTraduccionesRuzel100% (5)