Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Equal Protection: "Equal Protection" - Requisites of A Valid Classification - Bar From Drinking Gin

Transféré par

Earleen Del RosarioDescription originale:

Titre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Equal Protection: "Equal Protection" - Requisites of A Valid Classification - Bar From Drinking Gin

Transféré par

Earleen Del RosarioDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

EQUAL PROTECTION

People of the Philippines vs Cayat Equal Protection Requisites of a Valid Classification Bar from Drinking Gin In 1937, there exists a law (Act 1639) which bars native nonChristians from drinking gin or any other liquor outside of their customary alcoholic drinks. Cayat, a native of the Cordillera, was caught with an A-1-1 gin in violation of this Act. He was then charged and sentenced to pay P5.00 and to be imprisoned in case of insolvency. Cayat admitted his guilt but he challenged the constitutionality of the said Act. He averred, among others, that it violated his right to equal protection afforded by the constitution. He said this an attempt to treat them with discrimination or mark them as inferior or less capable race and less entitled will meet with their instant challenge. The law sought to distinguish and classify native non-Christians from Christians. ISSUE: Whether or not the said Act violates the equal protection clause. HELD: The SC ruled that Act 1639 is valid for it met the requisites of a reasonable classification. The SC emphasized that it is not enough that the members of a group have the characteristics that distinguish them from others. The classification must, as an indispensable requisite, not be arbitrary. The requisites to be complied with are; (1) must rest on substantial distinctions; (2) must be germane to the purposes of the law; (3) must not be limited to existing conditions only; and (4) must apply equally to all members of the same class. Act No. 1639 satisfies these requirements. The classification rests on real or substantial, not merely imaginary or whimsical, distinctions. It is not based upon accident of birth or parentage. The law, then, does not seek to mark the non Christian tribes as an inferior or less capable race. On the contrary, all measures thus far adopted in the promotion of the public policy towards them rest upon a recognition of their inherent right to equality in the enjoyment of those privileges now enjoyed by their Christian brothers. But as there can be no true equality before the law, if there is, in fact, no equality in education, the government has endeavored, by appropriate measures, to raise their culture and civilization and secure for them the benefits of their progress, with the ultimate end in view of placing them with their Christian brothers on the basis of true equality.

January 22, 1980

Facts: Petitioner Patricio Dumlao, is a former Governor of Nueva Vizcaya, who has filed his certificate of candidacy for said position of Governor in the forthcoming elections of January 30, 1980. Petitioner Dumlao specifically questions the constitutionality of section 4 of Batas Pambansa Blg. 52 as discriminatory and contrary to the equal protection and due process guarantees of the Constitution which provides that .Any retired elective provincial city or municipal official who has received payment of the retirement benefits to which he is entitled under the law and who shall have been 65 years of age at the commencement of the term of office to which he seeks to be elected shall not be qualified to run for the same elective local office from which he has retired. He likewise alleges that the provision is directed insidiously against him, and is based on purely arbitrary grounds, therefore, class legislation. Issue: Whether or not 1st paragraph of section 4 of BP 22 is valid. Held: In the case of a 65-year old elective local official, who has retired from a provincial, city or municipal office, there is reason to disqualify him from running for the same office from which he had retired, as provided for in the challenged provision. The need for new blood assumes relevance. The tiredness of the retiree for government work is present, and what is emphatically significant is that the retired employee has already declared himself tired and unavailable for the same government work, but, which, by virtue of a change of mind, he would like to assume again. It is for this very reason that inequality will neither result from the application of the challenged provision. Just as that provision does not deny equal protection, neither does it permit of such denial. The equal protection clause does not forbid all legal classification. What is proscribes is a classification which is arbitrary and unreasonable. That constitutional guarantee is not violated by a reasonable classification based upon substantial distinctions, where the classification is germane to the purpose of the low and applies to all those belonging to the same class. WHEREFORE, the first paragraph of section 4 of Batas Pambansa Bilang 52 is hereby declared valid.

DUMLAO vs. COMELEC 95 SCRA 392 L-52245

Ramon Ceniza et al vs COMELEC, COA & National Treasurer Equal Protection Gerrymandering

**Gerrymandering is a term employed to describe an apportionment of representative districts so contrived as to give an unfair advantage to the party in power. ** Pursuant to Batas Blg 51 (enacted 22 Dec 1979), COMELEC adopted Resolution No. 1421 which effectively bars voters in chartered cities (unless otherwise provided by their charter), highly urbanized (those earning above P40 M) cities, and component cities (whose charters prohibit them) from voting in provincial elections. The City of Mandaue, on the other hand, is a component city NOT a chartered one or a highly urbanized one. So when COMELEC added Mandaue to the list of 20 cities that cannot vote in provincial elections, Ceniza, in behalf of the other members of DOERS (Democracy or Extinction: Resolved to Succeed) questioned the constitutionality of BB 51 and the COMELEC resolution. They said that the regulation/restriction of voting being imposed is a curtailment of the right to suffrage. Further, petitioners claim that political and gerrymandering motives were behind the passage of Batas Blg. 51 and Section 96 of the Charter of Mandaue City. They contend that the Province of Cebu is politically and historically known as an opposition bailiwick and of the total 952,716 registered voters in the province, close to one-third (1/3) of the entire province of Cebu would be barred from voting for the provincial officials of the province of Cebu. Ceniza also said that the constituents of Mandaue never ratified their charter. Ceniza likewise aver that Sec 3 of BB 885 insofar as it classifies cities including Cebu City as highly urbanized as the only basis for not allowing its electorate to vote for the provincial officials is inherently and palpably unconstitutional in that such classification is not based on substantial distinctions germane to the purpose of the law which in effect provides for and regulates the exercise of the right of suffrage, and therefore such unreasonable classification amounts to a denial of equal protection. ISSUE: Whether or not there is a violation of equal protection. HELD: The thrust of the 1973 Constitution is towards the fullest autonomy of local government units. In the Declaration of Principles and State Policies, it is stated that The State shall guarantee and promote the autonomy of local government units to ensure their fullest development as self-reliant communities. The petitioners allegation of gerrymandering is of no merit, it has no factual or legal basis. The Constitutional requirement that the creation, division, merger, abolition, or alteration of the boundary of a province, city, municipality, or barrio should be subject to the approval by the majority of the votes cast in a plebiscite in the governmental unit or units affected is a new requirement that came into being only with the 1973 Constitution. It is prospective in character and therefore cannot affect the creation of the City of Mandaue which came into existence on 21 June 1969. The classification of cities into highly urbanized cities and component cities on the basis of their regular annual income is based upon substantial distinction. The revenue of a city would show whether or not it is capable of existence and

development as a relatively independent social, economic, and political unit. It would also show whether the city has sufficient economic or industrial activity as to warrant its independence from the province where it is geographically situated. Cities with smaller income need the continued support of the provincial government thus justifying the continued participation of the voters in the election of provincial officials in some instances. The petitioners also contend that the voters in Mandaue City are denied equal protection of the law since the voters in other component cities are allowed to vote for provincial officials. The contention is without merit. The practice of allowing voters in one component city to vote for provincial officials and denying the same privilege to voters in another component city is a matter of legislative discretion which violates neither the Constitution nor the voters right of suffrage. Rufino Nuez vs Sandiganbayan & the People of the Philippines Equal Protection Creation of the Sandiganbayan Nuez assails the validity of the PD 1486 creating the Sandiganbayan as amended by PD 1606. He was accused before the Sandiganbayan of estafa through falsification of public and commercial documents committed in connivance with his other co-accused, all public officials, in several cases. It is the claim of Nuez that PD1486, as amended, is violative of the due process, equal protection, and ex post facto clauses of the Constitution. He claims that the Sandiganbayan proceedings violates Nuezs right to equal protection, because appeal as a matter of right became minimized into a mere matter of discretion; appeal likewise was shrunk and limited only to questions of law, excluding a review of the facts and trial evidence; and there is only one chance to appeal conviction, by certiorari to the SC, instead of the traditional two chances; while all other estafa indictees are entitled to appeal as a matter of right covering both law and facts and to two appellate courts, i.e., first to the CA and thereafter to the SC. ISSUE: Whether or not the creation of Sandiganbayan violates equal protection insofar as appeals would be concerned. HELD: The SC ruled against Nuez. The 1973 Constitution had provided for the creation of a special court that shall have original jurisdiction over cases involving public officials charged with graft and corruption. The constitution specifically makes mention of the creation of a special court, the Sandiganbayan, precisely in response to a problem, the urgency of which cannot be denied, namely, dishonesty in the public service. It follows that those who may thereafter be tried by such court ought to have been aware as far back as January 17, 1973, when the present Constitution came into force, that a different procedure for the accused therein, whether a private citizen as petitioner is or a public official, is not necessarily offensive to the equal protection clause of the Constitution. Further, the classification therein set forth met the standard requiring that it must be based on substantial

distinctions which make real differences; it must be germane to the purposes of the law; it must not be limited to existing conditions only, and must apply equally to each member of the class. Further still, decisions in the Sandiganbayan are reached by a unanimous decision from 3 justices - a showing that decisions therein are more conceivably carefully reached than other trial courts.

PASEI vs DRILON 163 SCRA 380 Facts:Petitioner, Phil association of Service Exporters, Inc., is engaged principally in the recruitment of Filipino workers, male and female of overseas employment. It challenges the constitutional validity of Dept. Order No. 1 (1998) of DOLE entitled Guidelines Governing the Temporary Suspension of Deployment of Filipino Domestic and Household Workers. It claims that such order is a discrimination against males and females. The Order does not apply to all Filipino workers but only to domestic helpers and females with similar skills, and that it is in violation of the right to travel, it also being an invalid exercise of the lawmaking power. Further, PASEI invokes Sec 3 of Art 13 of the Constitution, providing for worker participation in policy and decision-making processes affecting their rights and benefits as may be provided by law. Thereafter the Solicitor General on behalf of DOLE submitting to the validity of the challenged guidelines involving the police power of the State and informed the court that the respondent have lifted the deployment ban in some states where there exists bilateral agreement with the Philippines and existing mechanism providing for sufficient safeguards to ensure the welfare and protection of the Filipino workers. Issue:Whether or not there has been a valid classification in the challenged Department Order No. 1. Decision:SC in dismissing the petition ruled that there has been valid classification, the Filipino female domestics working abroad were in a class by themselves, because of the special risk to which their class was exposed. There is no question that Order No.1 applies only to female contract workers but it does not thereby make an undue discrimination between sexes. It is well settled hat equality before the law under the constitution does not import a perfect identity of rights among all men and women. It admits of classification, provided that: 1. Such classification rests on substantial distinctions 2. That they are germane to the purpose of the law 3. They are not confined to existing conditions 4. They apply equally to al members of the same class In the case at bar, the classifications made, rest on substantial distinctions. Dept. Order No. 1 does not impair the right to travel. The consequence of the deployment ban has on the right to travel does not impair the right, as the right to travel is subjects among other things, to the requirements of public safety as may be provided by law. Deployment ban of female domestic helper is a valid exercise of police power. Police power as been defined as the state authority to enact legislation that may interfere with personal liberty or property in order to promote general welfare. Neither is there merit in the contention that Department Order No. 1 constitutes an invalid exercise of legislative power as the labor code vest the DOLE with rule making powers.

Read full text

Justice Makasiar (concurring & dissenting) Persons who are charged with estafa or malversation of funds not belonging to the government or any of its instrumentalities or agencies are guaranteed the right to appeal to two appellate courts first, to the CA, and thereafter to the SC. Estafa and malversation of private funds are on the same category as graft and corruption committed by public officers, who, under the decree creating the Sandiganbayan, are only allowed one appeal to the SC (par. 3, Sec. 7, P.D. No. 1606). The fact that the Sandiganbayan is a collegiate trial court does not generate any substantial distinction to validate this invidious discrimination. Three judges sitting on the same case does not ensure a quality of justice better than that meted out by a trial court presided by one judge. The ultimate decisive factors are the intellectual competence, industry and integrity of the trial judge. But a review by two appellate tribunals of the same case certainly ensures better justice to the accused and to the people. Then again, par 3 of Sec 7 of PD 1606, by providing that the decisions of the Sandiganbayan can only be reviewed by the SC through certiorari, likewise limits the reviewing power of the SC only to question of jurisdiction or grave abuse of discretion, and not questions of fact nor findings or conclusions of the trial court. In other criminal cases involving offenses not as serious as graft and corruption, all questions of fact and of law are reviewed, first by the CA, and then by the SC. To repeat, there is greater guarantee of justice in criminal cases when the trial courts judgment is subject to review by two appellate tribunals, which can appraise the evidence and the law with greater objectivity, detachment and impartiality unaffected as they are by views and prejudices that may be engendered during the trial. Limiting the power of review by the SC of convictions by the Sandiganbayan only to issues of jurisdiction or grave abuse of discretion, likewise violates the constitutional presumption of innocence of the accused, which presumption can only be overcome by proof beyond reasonable doubt (Sec. 19, Art. IV, 1973 Constitution). PASEI vs DRILON Edit 0 1

Philippine Judges Association et al vs DOTC Secretary Pete Prado et al on November 6, 2010 Equal Protection Franking Privilege of the Judiciary A report came in showing that available data from the Postal Service Office show that from January 1988 to June 1992, the total volume of frank mails amounted to P90,424,175.00, of this amount, frank mails from the Judiciary and other agencies whose functions include the service of judicial processes, such as the intervenor, the Department of Justice and the Office of the Ombudsman, amounted to P86,481,759. Frank mails coming from the Judiciary amounted to P73,574,864.00, and those coming from the petitioners reached the total amount of P60,991,431.00. The postmasters conclusion is that because of this considerable volume of mail from the Judiciary, the franking privilege must be withdrawn from it. Acting from this, Prado implemented Circ. No. 9228 as the IRR for the said law. PJA assailed the said law complaining that the law would adversely impair the communication within the judiciary as it may impair the sending of judicial notices. PJA averred that the law is discriminatory as it disallowed the franking privilege of the Judiciary but has not disallowed the franking privilege of others such as the executive, former executives and their widows among others. ISSUE: Whether or not there has been a violation of equal protection before the law. HELD: The SC ruled that there is a violation of the equal protection clause. The judiciary needs the franking privilege so badly as it is vital to its operation. Evident to that need is the high expense allotted to the judiciarys franking needs. The Postmaster cannot be sustained in contending that the removal of the franking privilege from the judiciary is in order to cut expenditure. This is untenable for if the Postmaster would intend to cut expenditure by removing the franking privilege of the judiciary, then they should have removed the franking privilege all at once from all the other departments. If the problem of the respondents is the loss of revenues from the franking privilege, the remedy is to withdraw it altogether from all agencies of the government, including those who do not need it. The problem is not solved by retaining it for some and withdrawing it from others, especially where there is no substantial distinction between those favored, which may or may not need it at all, and the Judiciary, which definitely needs it. The problem is not solved by violating the Constitution. The equal protection clause does not require the universal application of the laws on all persons or things without distinction. This might in fact sometimes result in unequal protection, as where, for example, a law prohibiting mature books to all persons, regardless of age, would benefit the morals of the youth but violate the liberty of adults. What the clause requires is equality among equals as determined according to a valid classification. By classification is meant the grouping of persons or things similar to each other in certain particulars and different from all others in these same particulars.

In lumping the Judiciary with the other offices from which the franking privilege has been withdrawn, Sec 35 has placed the courts of justice in a category to which it does not belong. If it recognizes the need of the President of the Philippines and the members of Congress for the franking privilege, there is no reason why it should not recognize a similar and in fact greater need on the part of the Judiciary for such privilege. Ormoc Sugar Company Inc. vs Ormoc City et al on November 15, 2010 Equal Protection In 1964, Ormoc City passed a bill which read: There shall be paid to the City Treasurer on any and all productions of centrifugal sugar milled at the Ormoc Sugar Company Incorporated, in Ormoc City a municipal tax equivalent to one per centum (1%) per export sale to the United States of America and other foreign countries. Though referred to as a production tax, the imposition actually amounts to a tax on the export of centrifugal sugar produced at Ormoc Sugar Company, Inc. For production of sugar alone is not taxable; the only time the tax applies is when the sugar produced is exported. Ormoc Sugar paid the tax (P7,087.50) in protest averring that the same is violative of Sec 2287 of the Revised Administrative Code which provides: It shall not be in the power of the municipal council to impose a tax in any form whatever, upon goods and merchandise carried into the municipality, or out of the same, and any attempt to impose an import or export tax upon such goods in the guise of an unreasonable charge for wharfage, use of bridges or otherwise, shall be void. And that the ordinance is violative to equal protection as it singled out Ormoc Sugar As being liable for such tax impost for no other sugar mill is found in the city. ISSUE: Whether or not there has been a violation of equal protection. HELD: The SC held in favor of Ormoc Sugar. The SC noted that even if Sec 2287 of the RAC had already been repealed by a latter statute (Sec 2 RA 2264) which effectively authorized LGUs to tax goods and merchandise carried in and out of their turf, the act of Ormoc City is still violative of equal protection. The ordinance is discriminatory for it taxes only centrifugal sugar produced and exported by the Ormoc Sugar Company, Inc. and none other. At the time of the taxing ordinances enactment, Ormoc Sugar Company, Inc., it is true, was the only sugar central in the city of Ormoc. Still, the classification, to be reasonable, should be in terms applicable to future conditions as well. The taxing ordinance should not be singular and exclusive as to exclude any subsequently established sugar central, of the same class as plaintiff, from the coverage of the tax. As it is now, even if later a similar company is set up, it cannot be subject to the tax because the ordinance expressly points only to Ormoc Sugar Company, Inc. as the entity to be levied upon. Francisco Tatad et al vs Secretary of Energy on November 15, 2010 Equal Protection Oil Deregulation Law

Considering that oil is not endemic to this country, history shows that the government has always been finding ways to alleviate the oil industry. The government created laws accommodate these innovations in the oil industry. One such law is the Downstream Oil Deregulation Act of 1996 or RA 8180. This law allows that any person or entity may import or purchase any quantity of crude oil and petroleum products from a foreign or domestic source, lease or own and operate refineries and other downstream oil facilities and market such crude oil or use the same for his own requirement, subject only to monitoring by the Department of Energy. Tatad assails the constitutionality of the law. He claims, among others, that the imposition of different tariff rates on imported crude oil and imported refined petroleum products violates the equal protection clause. Tatad contends that the 3%-7% tariff differential unduly favors the three existing oil refineries and discriminates against prospective investors in the downstream oil industry who do not have their own refineries and will have to source refined petroleum products from abroad.3% is to be taxed on unrefined crude products and 7% on refined crude products. ISSUE: Whether or not RA 8180 is constitutional. HELD: The SC declared the unconstitutionality of RA 8180 because it violated Sec 19 of Art 12 of the Constitution. It violated that provision because it only strengthens oligopoly which is contrary to free competition. It cannot be denied that our downstream oil industry is operated and controlled by an oligopoly, a foreign oligopoly at that. Petron, Shell and Caltex stand as the only major league players in the oil market. All other players belong to the lilliputian league. As the dominant players, Petron, Shell and Caltex boast of existing refineries of various capacities. The tariff differential of 4% therefore works to their immense benefit. Yet, this is only one edge of the tariff differential. The other edge cuts and cuts deep in the heart of their competitors. It erects a high barrier to the entry of new players. New players that intend to equalize the market power of Petron, Shell and Caltex by building refineries of their own will have to spend billions of pesos. Those who will not build refineries but compete with them will suffer the huge disadvantage of increasing their product cost by 4%. They will be competing on an uneven field. The argument that the 4% tariff differential is desirable because it will induce prospective players to invest in refineries puts the cart before the horse. The first need is to attract new players and they cannot be attracted by burdening them with heavy disincentives. Without new players belonging to the league of Petron, Shell and Caltex, competition in our downstream oil industry is an idle dream. RA 8180 is unconstitutional on the ground inter alia that it discriminated against the new players insofar as it placed them at a competitive disadvantage vis--vis the established oil companies by requiring them to meet certain conditions already being observed by the latter. EN BANC [G.R. NO. 148208, DECEMBER 15, 2004]

CENTRAL BANK (NOW BANGKO SENTRAL NG PILIPINAS) EMPLOYEES ASSOCIATION, INC., PETITIONER, vs. BANGKO SENTRAL NG PILIPINAS AND THE EXECUTIVE SECRETARY, RESPONDENTS.

FACTS: On July 3, 1993, R.A. No. 7653 (the New Central Bank Act) took effect. It abolished the old Central Bank of the Philippines, and created a new BSP. On June 8, 2001, almost eight years after the effectivity of R.A. No. 7653, petitioner Central Bank (now BSP) Employees Association, Inc., filed a petition for prohibition against BSP and the Executive Secretary of the Office of the President, to restrain respondents from further implementing the last proviso in Section 15(c), Article II of R.A. No. 7653, on the ground that it is unconstitutional. Article II, Section 15(c) of R.A. No. 7653 provides: Section 15, Exercise of Authority -In the exercise of its authority, the Monetary Board shall: (c) Establish a human resource management system which shall govern the selection, hiring, appointment, transfer, promotion, or dismissal of all personnel. Such system shall aim to establish professionalism and excellence at all levels of the Bangko Sentral in accordance with sound principles of management. A compensation structure, based on job evaluation studies and wage surveys and subject to the Boards approval, shall be instituted as an integral component of the Bangko Sentrals human resource development program: Provided, That the Monetary Board shall make its own system conform as closely as possible with the principles provided for under Republic Act No. 6758 [Salary Standardization Act]. Provided, however, that compensation and wage structure of employees whose positions fall under salary grade 19 and below shall be in accordance with the rates prescribed under Republic Act No. 6758. The thrust of petitioners challenge is that the above proviso makes an unconstitutional cut between two classes of employees in the BSP, viz: (1) the BSP officers or those exempted from the coverage of the Salary Standardization Law (SSL) (exempt class); and (2) the rankand-file (Salary Grade [SG] 19 and below), or those not exempted from the coverage of the SSL (non-exempt class). It is contended that this classification is a classic case of class legislation, allegedly not based on substantial distinctions which make real differences, but solely on the SG of the BSP personnels position.

Petitioner also claims that it is not germane to the purposes of Section 15(c), Article II of R.A. No. 7653, the most

important of which is to establish professionalism and excellence at all levels in the BSP. Petitioner offers the following sub-set of arguments: a. the legislative history of R.A. No. 7653 shows that the questioned proviso does not appear in the original and amended versions of House Bill No. 7037, nor in the original version of Senate Bill No. 1235; b. subjecting the compensation of the BSP rank-and-file employees to the rate prescribed by the SSL actually defeats the purpose of the law of establishing professionalism and excellence eat all levels in the BSP; c. the assailed proviso was the product of amendments introduced during the deliberation of Senate Bill No. 1235, without showing its relevance to the objectives of the law, and even admitted by one senator as discriminatory against low-salaried employees of the BSP; d. GSIS, LBP, DBP and SSS personnel are all exempted from the coverage of the SSL; thus within the class of rank-and-file personnel of government financial institutions (GFIs), the BSP rank-and-file are also discriminated upon; and e. the assailed proviso has caused the demoralization among the BSP rank-and-file and resulted in the gross disparity between their compensation and that of the BSP officers. In sum, petitioner posits that the classification is not reasonable but arbitrary and capricious, and violates the equal protection clause of the Constitution. Petitioner also stresses: (a) that R.A. No. 7653 has a separability clause, which will allow the declaration of the unconstitutionality of the proviso in question without affecting the other provisions; and (b) the urgency and propriety of the petition, as some 2,994 BSP rank-and-file employees have been prejudiced since 1994 when the proviso was implemented. Petitioner concludes that: (1) since the inequitable proviso has no force and effect of law, respondents implementation of such amounts to lack of jurisdiction; and (2) it has no appeal nor any other plain, speedy and adequate remedy in the ordinary course except through this petition for prohibition, which this Court should take cognizance of, considering the transcendental importance of the legal issue involved. Respondent BSP, in its comment, contends that the provision does not violate the equal protection clause and can stand the constitutional test, provided it is construed in harmony with other provisions of the same law, such as fiscal and administrative autonomy of BSP, and the mandate of the Monetary Board to establish professionalism and excellence at all levels in accordance with sound principles of management. The Solicitor General, on behalf of respondent Executive Secretary, also defends the validity of the provision. Quite simplistically, he argues that the classification is based on actual and real differentiation, even as it adheres to the enunciated policy of R.A. No. 7653 to establish

professionalism and excellence within the BSP subject to prevailing laws and policies of the national government.

ISSUE: Thus, the sole - albeit significant - issue to be resolved in this case is whether the last paragraph of Section 15(c), Article II of R.A. No. 7653, runs afoul of the constitutional mandate that "No person shall be . . . denied the equal protection of the laws." RULING: A. UNDER THE PRESENT STANDARDS OF EQUAL PROTECTION, SECTION 15(c), ARTICLE II OF R.A. NO. 7653 IS VALID. Jurisprudential standards for equal protection challenges indubitably show that the classification created by the questioned proviso, on its face and in its operation, bears no constitutional infirmities. It is settled in constitutional law that the "equal protection" clause does not prevent the Legislature from establishing classes of individuals or objects upon which different rules shall operate - so long as the classification is not unreasonable. B. THE ENACTMENT, HOWEVER, OF SUBSEQUENT LAWS EXEMPTING ALL OTHER RANK-AND-FILE EMPLOYEES OF GFIs FROM THE SSL - RENDERS THE CONTINUED APPLICATION OF THE CHALLENGED PROVISION A VIOLATION OF THE EQUAL PROTECTION CLAUSE. While R.A. No. 7653 started as a valid measure well within the legislatures power, we hold that the enactment of subsequent laws exempting all rank-and-file employees of other GFIs leeched all validity out of the challenged proviso. The constitutionality of a statute cannot, in every instance, be determined by a mere comparison of its provisions with applicable provisions of the Constitution, since the statute may be constitutionally valid as applied to one set of facts and invalid in its application to another. A statute valid at one time may become void at another time because of altered circumstances. Thus, if a statute in its practical operation becomes arbitrary or confiscatory, its validity, even though affirmed by a former adjudication, is open to inquiry and investigation in the light of changed conditions. The foregoing provisions impregnably institutionalize in this jurisdiction the long honored legal truism of "equal pay for equal work." Persons who work with substantially equal

qualifications, skill, effort and responsibility, under similar conditions, should be paid similar salaries. Congress retains its wide discretion in providing for a valid classification, and its policies should be accorded recognition and respect by the courts of justice except when they run afoul of the Constitution. The deference stops where the classification violates a fundamental right, or prejudices persons accorded special protection by the Constitution. When these violations arise, this Court must discharge its primary role as the vanguard of constitutional guaranties, and require a stricter and more exacting adherence to constitutional limitations. Rational basis should not suffice. Furthermore, concerns have been raised as to the propriety of a ruling voiding the challenged provision. It has been proffered that the remedy of petitioner is not with this Court, but with Congress, which alone has the power to erase any inequity perpetrated by R.A. No. 7653. Indeed, a bill proposing the exemption of the BSP rank-and-file from the SSL has supposedly been filed. Under most circumstances, the Court will exercise judicial restraint in deciding questions of constitutionality, recognizing the broad discretion given to Congress in exercising its legislative power. Judicial scrutiny would be based on the rational basis test, and the legislative discretion would be given deferential treatment. But if the challenge to the statute is premised on the denial of a fundamental right or the perpetuation of prejudice against persons favored by the Constitution with special protection, judicial scrutiny ought to be more strict. A weak and watered down view would call for the abdication of this Courts solemn duty to strike down any law repugnant to the Constitution and the rights it enshrines. This is true whether the actor committing the unconstitutional act is a private person or the government itself or one of its instrumentalities. Oppressive acts will be struck down regardless of the character or nature of the actor. Accordingly, when the grant of power is qualified, conditional or subject to limitations, the issue on whether or not the prescribed qualifications or conditions have been met, or the limitations respected, is justifiable or non-political, the crux of the problem being one of legality or validity of the contested act, not its wisdom. Otherwise, said qualifications, conditions or limitations - particularly those prescribed or imposed by the Constitution - would be set at naught. What is more, the judicial inquiry into such issue and the settlement thereof are the main functions of courts of justice under the Presidential form of government adopted in our 1935 Constitution, and the system of checks and balances, one of its basic predicates. As a consequence, we have neither the authority nor the discretion to decline passing upon said issue, but are under the ineluctable obligation - made particularly more exacting and peremptory by our oath, as members of the highest Court of the land, to support and defend the Constitution - to settle it.

In the case at bar, the challenged proviso operates on the basis of the salary grade or officer-employee status. It is akin to a distinction based on economic class and status, with the higher grades as recipients of a benefit specifically withheld from the lower grades. Officers of the BSP now receive higher compensation packages that are competitive with the industry, while the poorer, low-salaried employees are limited to the rates prescribed by the SSL. The implications are quite disturbing: BSP rank-and-file employees are paid the strictly regimented rates of the SSL while employees higher in rank - possessing higher and better education and opportunities for career advancement - are given higher compensation packages to entice them to stay. Considering that majority, if not all, the rank-and-file employees consist of people whose status and rank in life are less and limited, especially in terms of job marketability, it is they - and not the officers - who have the real economic and financial need for the adjustment This is in accord with the policy of the Constitution "to free the people from poverty, provide adequate social services, extend to them a decent standard of living, and improve the quality of life for all. Any act of Congress that runs counter to this constitutional desideratum deserves strict scrutiny by this Court before it can pass muster. To be sure, the BSP rank-and-file employees merit greater concern from this Court. They represent the more impotent rank-and-file government employees who, unlike employees in the private sector, have no specific right to organize as a collective bargaining unit and negotiate for better terms and conditions of employment, nor the power to hold a strike to protest unfair labor practices. These BSP rank-and-file employees represent the politically powerless and they should not be compelled to seek a political solution to their unequal and iniquitous treatment. Indeed, they have waited for many years for the legislature to act. They cannot be asked to wait some more for discrimination cannot be given any waiting time. Unless the equal protection clause of the Constitution is a mere platitude, it is the Courts duty to save them from reasonless discrimination. IN VIEW WHEREOF, we hold that the continued operation and implementation of the last proviso of Section 15(c), Article II of Republic Act No. 7653 is unconstitutional. Lao Ichong vs Jaime Hernandez on November 22, 2010 Constitutional Law Treaties May Be Superseded by Municipal Laws in the Exercise of Police Power Lao Ichong is a Chinese businessman who entered the country to take advantage of business opportunities herein abound (then) particularly in the retail business. For some time he and his fellow Chinese businessmen enjoyed a monopoly in the local market in Pasay. Until in June 1954 when Congress passed the RA 1180 or the Retail Trade Nationalization Act the purpose of which is to reserve to Filipinos the right to engage in the retail business. Ichong then petitioned for the nullification of the said Act on the

ground that it contravened several treaties concluded by the RP which, according to him, violates the equal protection clause (pacta sund servanda). He said that as a Chinese businessman engaged in the business here in the country who helps in the income generation of the country he should be given equal opportunity. ISSUE: Whether or not a law may invalidate or supersede treaties or generally accepted principles. HELD: Yes, a law may supersede a treaty or a generally accepted principle. In this case, there is no conflict at all between the raised generally accepted principle and with RA 1180. The equal protection of the law clause does not demand absolute equality amongst residents; it merely requires that all persons shall be treated alike, under like circumstances and conditions both as to privileges conferred and liabilities enforced; and, that the equal protection clause is not infringed by legislation which applies only to those persons falling within a specified class, if it applies alike to all persons within such class, and reasonable grounds exist for making a distinction between those who fall within such class and those who do not. For the sake of argument, even if it would be assumed that a treaty would be in conflict with a statute then the statute must be upheld because it represented an exercise of the police power which, being inherent could not be bargained away or surrendered through the medium of a treaty. Hence, Ichong can no longer assert his right to operate his market stalls in the Pasay city market. THE PEOPLE OF THE PHILIPPINES, plaintiff-appellee vs. CAROL M. DELA PIEDRA, accused-appellant G.R. No. 121777 (350 SCRA 163) January 24, 2001 KAPUNAN, J.

initial payment of P2,000 to Jasmine, who assured her that she was authorized to receive the money. Meanwhile, in the morning of the said date, Erlie Ramos, Attorney II of the Philippine Overseas Employment Agency (POEA), received a telephone call from an unidentified woman inquiring about the legitimacy of the recruitment conducted by a certain Mrs. Carol Figueroa. Ramos, whose duties include the surveillance of suspected illegal recruiters, immediately contacted a friend, a certain Mayeth Bellotindos, so they could both go the place where the recruitment was reportedly being undertaken . Upon arriving at the reported area at around 4:00 p.m., Bellotindos entered the house and pretended to be an applicant. Ramos remained outside and stood on the pavement, from where he was able to see around six (6) persons in the sala. Ramos even heard a woman, identified as Carol Figueroa, talk about the possible employment she has to provide in Singapore and the documents that the applicants have to comply with. Fifteen (15) minutes later, Bellotindos came out with a biodata form in hand. Thereafter, Ramos conferred with a certain Capt. Mendoza of the Criminal Investigation Service (CIS) to organize the arrest of the alleged illegal recruiter. A surveillance team was then organized to confirm the report. After which, a raid was executed. Consequently, Carol was charged and convicted by the trial court of illegal recruitment. Upon appeal, accused questions her conviction for illegal recruitment in large scale and assails, as well, the constitutionality of the law defining and penalizing said crime. First, accused submits that Article 13 (b) of the Labor Code defining recruitment and placement is void for vagueness and, thus, violates the due process clause. The provision in question reads:

FACTS: On the afternoon of January 30, 1994, Maria Lourdes Modesto and Nancy Araneta together with her friends Jennelyn Baez, and Sandra Aquino went to the house of Jasmine Alejandro, after having learned that a woman is there to recruit job applicants for Singapore. Carol dela Piedra was already briefing some people when they arrived. Jasmine, on the other hand, welcomed and asked them to sit down. They listened to the recruiter who was then talking about the breakdown of the fees involved: P30,000 for the visa and the round trip ticket, and P5,000 as placement fee and for the processing of the papers. The initial payment was P2,000, while P30,000 will be by salary deduction. The recruiter said that she was recruiting nurses for Singapore. Araneta, her friends and Lourdes then filled up biodata forms and were required to submit pictures and a transcript of records. After the interview, Lourdes gave the

ART. 13. Definitions.(a) x x x. (b) Recruitment and placement refers to any act of canvassing, enlisting, contracting, transporting, utilizing, hiring or procuring workers, and includes referrals, contract services, promising or advertising for employment, locally or abroad, whether for profit or not: Provided, That any person or entity which, in any manner, offers or promises for a fee employment to two or more persons shall be deemed engaged in

recruitment placement.

and

an applicant, according to appellant, for employment to a prospective employer) does not render the law overbroad. Evidently, Dela Piedra misapprehends concept of overbreadth. A statute may be said to be overbroad where it operates to inhibit the exercise of individual freedoms affirmatively guaranteed by the Constitution, such as the freedom of speech or religion. A generally worded statute, when construed to punish conduct which cannot be constitutionally punished is unconstitutionally vague to the extent that it fails to give adequate warning of the boundary between the constitutionally permissible and the constitutionally impermissible applications of the statute.

ISSUES: (1) Whether or not sec. 13 (b) of P.D. 442, as amended, otherwise known as the illegal recruitment law is unconstitutional as it violates the due process clause. (2) Whether or not accused was denied equal protection and therefore should be exculpated

HELD: (1) For the First issue, dela Piedra submits that Article 13 (b) of the Labor Code defining recruitment and placement is void for vagueness and, thus, violates the due process clause. Due process requires that the terms of a penal statute must be sufficiently explicit to inform those who are subject to it what conduct on their part will render them liable to its penalties. In support of her submission, dela Piedra invokes People vs. Panis, where the Supreme Court criticized the definition of recruitment and placement. The Court ruled, however, that her reliance on the said case was misplaced. The issue in Panis was whether, under the proviso of Article 13 (b), the crime of illegal recruitment could be committed only whenever two or more persons are in any manner promised or offered any employment for a fee. In this case, the Court merely bemoaned the lack of records that would help shed light on the meaning of the proviso. The absence of such records notwithstanding, the Court was able to arrive at a reasonable interpretation of the proviso by applying principles in criminal law and drawing from the language and intent of the law itself. Section 13 (b), therefore, is not a perfectly vague act whose obscurity is evident on its face. If at all, the proviso therein is merely couched in imprecise language that was salvaged by proper construction. It is not void for vagueness.

(2)

Anent the second issue, Dela Piedra invokes the equal protection clause in her defense. She points out that although the evidence purportedly shows that Jasmine Alejandro handed out application forms and even received Lourdes Modestos payment, appellant was the only one criminally charged. Alejandro, on the other hand, remained scot-free. From this, she concludes that the prosecution discriminated against her on grounds of regional origins. Appellant is a Cebuana while Alejandro is a Zamboanguea, and the alleged crime took place in Zamboanga City. The Supreme Court held that the argument has no merit. The prosecution of one guilty person while others equally guilty are not prosecuted, is not, by itself, a denial of the equal protection of the laws. The unlawful administration by officers of a statute fair on its face, resulting in its unequal application to those who are entitled to be treated alike, is not a denial of equal protection unless there is shown to be present in it an element of intentional or purposeful discrimination. But a discriminatory purpose is not presumed, there must be a showing of clear and intentional discrimination. In the case at bar, Dela Piedra has failed to show that, in charging her, there was a clear and intentional discrimination on the part of the prosecuting officials. Furthermore, the presumption is that the prosecuting officers regularly performed their duties, and this presumption can be overcome only by proof to the contrary, not by mere speculation. As said earlier, accused has not presented any evidence to overcome this presumption. The mere allegation that dela Piedra, a Cebuana, was charged with the commission of a crime, while a Zamboanguea, the guilty party in appellants eyes,

Dela Piedra further argues that the acts that constitute recruitment and placement suffer from overbreadth since by merely referring a person for employment, a person may be convicted of illegal recruitment. That Section 13 (b) encompasses what appellant apparently considers as customary and harmless acts such as labor or employment referral (referring

was not, is insufficient to support a conclusion that the prosecution officers denied appellant equal protection of the laws.

PLACER VS. JUDGE VILLANUEVA [126 SCRA 463; G.R. NOS. L-60349-62; 29 DEC 1983]

Tuesday, February 03, 2009 Posted by Coffeeholic Writes Labels: Case Digests, Political Law

SEARCHES & SEIZURES Amarga v. Abbas, 98 Phil. 739 (1956) F: Municipal Judge Samulde conducted a preliminary investigation (PI) of Arangale upon a complaint for robbery filed by complainant Magbanua, alleging that Arangale harvested palay from a portion of her land directly adjoining Arangales land. After the PI, Samulde transmitted the records of the case to Provincial Fiscal Salvani with his finding that there is prima facie evidence of robbery as charged in the complaint. Fiscal Salvani returned the records to Judge Samulde on the ground that the transmittal of the records was premature because Judge Samulde failed to include the warrant of arrest (WA) against the accused. Judge Samulde sent the records back to Fiscal Salvani stating that although he found that a probable cause existed, he did not believe that Arangale should be arrested. Fiscal Salvani filed a mandamus case against Judge Samulde to compel him to issue a WA. RTC dismissed the petition on the ground that the fiscal had not shown that he has a clear, legal right to the performance of the act to be required of the judge and that the latter had an imperative duty to perform it. Neverhteless, Judge Samulde was ordered to issue a WA in accordance with Sec. 5, Rule 112 of the 1985 Rules of Court. ISSUE: Whether it is mandatory for the investigating judge to issue a WA of the accused in view of his finding, after conducting a PI, that there exists prima facie evidence that the accused commited the crime charged. HELD: THE PURPOSE OF A PRELIMINARY INVESTIGATION DOES NOT CONTEMPLATE THE ISSUANCE OF A WA BY THE INVESTIGATING JUDGE OR OFFICER. Under Rule 112 of the 1985 ROC, a PI is conducted on the basis of affidavits to determine whether or not there is sufficient ground to hold the accused for trial. To determine whether a WA should issue, the investigating judge must have examined in writing and under oath the complainant and his wirtnesses by searching questions and answers; he must be satisfied that a probable cause exists; and there must be a need to place the accused under immediate custody in order not to frustrate the ends of justice. It is not obligatory, but merely discretionary, upon the investigating judge to issue a WA, for the determination of whether it is necessary to arrest the accused in order not to frustrate the ends of justice, is left to his sound judgment or discretion. The fiscal should, instead, have filed an information immediately so that the RTC may issue a warrant for the arrest of the accused.

Facts:

Petitioners filed informations in the city court and they certified that Preliminary Investigation and Examination had been conducted and that prima facie cases have been found. Upon receipt of said informations, respondent judge set the hearing of the criminal cases to determine propriety of issuance of warrants of arrest. After the hearing, respondent issued an order requiring petitioners to submit to the court affidavits of prosecution witnesses and other documentary evidence in support of the informations to aid him in the exercise of his power of judicial review of the findings of probable cause by petitioners. Petitioners petitioned for certiorari and mandamus to compel respondent to issue warrants of arrest. They contended that the fiscals certification in the informations of the existence of probable cause constitutes sufficient justification for the judge to issue warrants of arrest.

Issue:

Whether or Not respondent city judge may, for the purpose of issuing warrants of arrest, compel the fiscal to submit to the court the supporting affidavits and other documentary evidence presented during the preliminary investigation.

Soliven vs Makasiar

on October 29, 2011

Constitutional Law Presidents Immunity From Suit Must Be Invoked by the President

Beltran is among the petitioners in this case. He together with others was charged for libel by the president. Cory herself filed a complaint-affidavit against him and others. Makasiar averred that Cory cannot file a complaint affidavit because this would defeat her immunity from suit. He grounded his

Held:

Judge may rely upon the fiscals certification for the existence of probable cause and on the basis thereof, issue a warrant of arrest. But, such certification does not bind the judge to come out with the warrant. The issuance of a warrant is not a mere ministerial function; it calls for the exercise of judicial discretion on the part of issuing magistrate. Under Section 6 Rule 112 of the Rules of Court, the judge must satisfy himself of the existence of probable cause before issuing a warrant of arrest. If on the face of the information, the judge finds no probable cause, he may disregard the fiscals certification and require submission of the affidavits of witnesses to aid him in arriving at the conclusion as to existence of probable cause. Petition dismissed.

contention on the principle that a president cannot be sued. However, if a president would sue then the president would allow herself to be placed under the courts jurisdiction and conversely she would be consenting to be sued back. Also, considering the functions of a president, the president may not be able to appear in court to be a witness for herself thus she may be liable for contempt. ISSUE: Whether or not such immunity can be invoked by Beltran, a person other than the president. HELD: The rationale for the grant to the President of the privilege of immunity from suit is to assure the exercise of Presidential duties and functions free from any hindrance or distraction, considering that being the Chief Executive of the Government is a job that, aside from requiring all of the officeholders time, also demands undivided attention. But this privilege of immunity from suit, pertains to the President by virtue of the office and may be invoked only by the holder of the office; not by any other person in the Presidents behalf. Thus, an accused like Beltran et al, in a criminal case in which the President is complainant cannot raise the

presidential privilege as a defense to prevent the case from proceeding against such accused. Moreover, there is nothing in our laws that would prevent the President from waiving the privilege. Thus, if so minded the President may shed the protection afforded by the privilege and submit to the courts jurisdiction. The choice of whether to exercise the privilege or to waive it is solely the Presidents prerogative. It is a decision that cannot be assumed and imposed by any other person.

HELD: Enrile filed for habeas corpus because he was denied bail although ordinarily a charge of rebellion would entitle one for bail. The crime of rebellion charged against him however is complexed with murder and multiple frustrated murders the intention of the prosecution was to make rebellion in its most serious form so as to make the penalty thereof in the maximum. The SC ruled that there is no such crime as Rebellion with murder and multiple frustrated murder. What Enrile et al can be charged of would be Simple Rebellion because other crimes such as murder or all those that may be necessary to the commission of rebellion is absorbed hence he should be entitiled for bail. The SC however noted that a petition for habeas corpus was not the proper remedy so as to avail of bail. The proper step that should have been taken was for Enrile to file a petition to be admitted

Enrile vs Salazar

on October 30, 2011

Constitutional Law Political Question Restriction to the exercise of judicial power

In February 1990, Sen Enrile was arrested. He was charged together with Mr. & Mrs. Panlilio, and Honasan for the crime of rebellion with murder and multiple frustrated murder which allegedly occurred during their failed coup attempt. Enrile was then brought to Camp Karingal. Enrile later filed for the habeas corpus alleging that the crime being charged against him is non existent. That he was charged with a criminal offense in an information for which no complaint was initially filed or preliminary investigation was conducted, hence was denied due process; denied his right to bail; and arrested and detained on the strength of a warrant issued without the judge who issued it first having personally determined the existence of probable cause. ISSUE: Whether or Enriles arrest is valid.

for bail. He should have exhausted all other efforts before petitioning for habeas corpus. The SC further notes that there is a need to restructure the law on rebellion as it is being used apparently by others as a tool to disrupt the peace and espouse violence. The SC can only act w/in the bounds of the law. Thus SC said There is an apparent need to restructure the law on rebellion, either to raise the penalty therefor or to clearly define and delimit the other offenses to be considered as absorbed thereby, so that it cannot be conveniently utilized as the umbrella for every sort of illegal activity undertaken in its name. The Court has no power to effect such change, for it can only interpret the law as it stands at any given time, and what is needed lies beyond interpretation. Hopefully, Congress will perceive the need for promptly seizing the initiative in this matter, which is properly within its province.

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- Consti DigestsDocument37 pagesConsti DigestsEarleen Del RosarioPas encore d'évaluation

- Equal Protection: "Equal Protection" - Requisites of A Valid Classification - Bar From Drinking GinDocument22 pagesEqual Protection: "Equal Protection" - Requisites of A Valid Classification - Bar From Drinking GinEarleen Del RosarioPas encore d'évaluation

- Consti DigestsDocument46 pagesConsti DigestsEarleen Del RosarioPas encore d'évaluation

- Consti DigestsDocument36 pagesConsti DigestsEarleen Del RosarioPas encore d'évaluation

- People of The Philippines Vs Cayat: "Equal Protection" - Requisites of A Valid Classification - Bar From Drinking GinDocument18 pagesPeople of The Philippines Vs Cayat: "Equal Protection" - Requisites of A Valid Classification - Bar From Drinking GinEarleen Del RosarioPas encore d'évaluation

- Consti 3 CasesDocument22 pagesConsti 3 CasesOliver JayPas encore d'évaluation

- Maquera v. Borra DigestDocument4 pagesMaquera v. Borra Digestnadinemuch100% (1)

- Equal Protection (Case Digests)Document9 pagesEqual Protection (Case Digests)ApureelRosePas encore d'évaluation

- Beltran Vs Sec. of Health: 12. Philippine Judges Association vs. Honorable PradoDocument10 pagesBeltran Vs Sec. of Health: 12. Philippine Judges Association vs. Honorable PradoLisa MoorePas encore d'évaluation

- Equal Protection CasesDocument3 pagesEqual Protection CasesRosie AlviorPas encore d'évaluation

- Maquera vs. Borra, 15 Scra 7 (1965)Document4 pagesMaquera vs. Borra, 15 Scra 7 (1965)ariesha1985Pas encore d'évaluation

- Maquera v. BorraDocument5 pagesMaquera v. BorraKRISANTA DE GUZMANPas encore d'évaluation

- 255 - 360 Art IiiDocument47 pages255 - 360 Art IiiGabriel ReyesPas encore d'évaluation

- Reviewer in Election Law - Sandoval NotesDocument21 pagesReviewer in Election Law - Sandoval NotesUi Bin DMPas encore d'évaluation

- A-VI S-8 B GERRYMANDERING Ceniza Vs COMELEC GR L-52304 DigestDocument1 pageA-VI S-8 B GERRYMANDERING Ceniza Vs COMELEC GR L-52304 DigestSonnyPas encore d'évaluation

- Outline 2, 3 and 4Document9 pagesOutline 2, 3 and 4Anne DerramasPas encore d'évaluation

- Ceniza V ComelecDocument3 pagesCeniza V ComelecRR FPas encore d'évaluation

- 6-15 Maquera v. Borra, G.R. No. L-24761, September 7, 1965Document9 pages6-15 Maquera v. Borra, G.R. No. L-24761, September 7, 1965Reginald Dwight FloridoPas encore d'évaluation

- 3 Maquera - v. - BorraDocument6 pages3 Maquera - v. - BorraShine Lws RubinPas encore d'évaluation

- State Policies CasesDocument116 pagesState Policies CasessofiaPas encore d'évaluation

- AASJS Vs DATUMANONGDocument58 pagesAASJS Vs DATUMANONGsan21cortezPas encore d'évaluation

- Digested Consti 2 CasesDocument20 pagesDigested Consti 2 CasesThessaloe B. FernandezPas encore d'évaluation

- Case Digest 157-172Document19 pagesCase Digest 157-172Jm Borbon MartinezPas encore d'évaluation

- Case Digest 157-172Document22 pagesCase Digest 157-172Jm Borbon MartinezPas encore d'évaluation

- Kabataan Party List V COMELEC - DigestcrtiqueDocument3 pagesKabataan Party List V COMELEC - DigestcrtiqueJhea MillarPas encore d'évaluation

- Consti 2 Equal ProtectionDocument8 pagesConsti 2 Equal ProtectionKim Jan Navata BatecanPas encore d'évaluation

- Dumlao Vs ComelecDocument4 pagesDumlao Vs ComelecJuvy Dimaano100% (1)

- Cardino and EjercitoDocument2 pagesCardino and EjercitoKrizea Marie DuronPas encore d'évaluation

- Admelec Final Exam Item No. IDocument9 pagesAdmelec Final Exam Item No. IJolo EspinoPas encore d'évaluation

- Poli. Equal ProtectionDocument13 pagesPoli. Equal ProtectionBettina BarrionPas encore d'évaluation

- Equal Protection CasesDocument19 pagesEqual Protection CasesJan Michael YoungPas encore d'évaluation

- Ceniza Vs ComelecDocument1 pageCeniza Vs ComelecJomar TenezaPas encore d'évaluation

- Right To Information DigestsDocument3 pagesRight To Information DigestsRiya YadaoPas encore d'évaluation

- Dumlao V ComelecDocument4 pagesDumlao V Comeleceieipayad100% (1)

- Dumalo Vs ComelecDocument3 pagesDumalo Vs ComelecDiane UyPas encore d'évaluation

- Statcon DigestDocument4 pagesStatcon DigestAlexis GabuyaPas encore d'évaluation

- League of Cities vs. ComelecDocument4 pagesLeague of Cities vs. ComelecAlexis GabuyaPas encore d'évaluation

- Consti 1 Report-A Just and Dynamic Social OrderDocument8 pagesConsti 1 Report-A Just and Dynamic Social OrderJen DeePas encore d'évaluation

- F1 - Maquera v. BorraDocument3 pagesF1 - Maquera v. BorraJairus LacabaPas encore d'évaluation

- David G. Nitafan, Wenceslao M. Polo, and Maximo A. Savellano, JR., PetitionersDocument7 pagesDavid G. Nitafan, Wenceslao M. Polo, and Maximo A. Savellano, JR., PetitionersLewidref ManalotoPas encore d'évaluation

- Election Laws (Q & A by Atty. Sandoval)Document11 pagesElection Laws (Q & A by Atty. Sandoval)KrisLarrPas encore d'évaluation

- Soriano III vs. ListaDocument1 pageSoriano III vs. ListaSERVICES SUBPas encore d'évaluation

- Consti Cases 88-117Document32 pagesConsti Cases 88-117stephen tubanaPas encore d'évaluation

- Political Law - Election Laws - Absentee Voters Act - Proclamation of Winners in A National ElectionsDocument18 pagesPolitical Law - Election Laws - Absentee Voters Act - Proclamation of Winners in A National ElectionsJennylyn Favila MagdadaroPas encore d'évaluation

- Political Law - Election Laws - Absentee Voters Act - Proclamation of Winners in A National ElectionsDocument7 pagesPolitical Law - Election Laws - Absentee Voters Act - Proclamation of Winners in A National ElectionsJennylyn Favila MagdadaroPas encore d'évaluation

- Equal Protection of The LawsDocument16 pagesEqual Protection of The LawsGlyza Kaye Zorilla PatiagPas encore d'évaluation

- Cruz Vs Secretary of DENRDocument23 pagesCruz Vs Secretary of DENRBai YadePas encore d'évaluation

- Lopez JR Vs ComelecDocument3 pagesLopez JR Vs ComelecRaymond RoquePas encore d'évaluation

- 45 Dumlao VS Comelec PDFDocument3 pages45 Dumlao VS Comelec PDFKJPL_1987Pas encore d'évaluation

- Legislative DepartmentDocument28 pagesLegislative DepartmentCyrus Dait100% (1)

- Equal Protection of The LawsDocument16 pagesEqual Protection of The LawsMary Megan TaboraPas encore d'évaluation

- LOZADA Vs CommissionerDocument2 pagesLOZADA Vs CommissionerM GrâShâ VAPas encore d'évaluation

- CONSTI Legislative CASESDocument20 pagesCONSTI Legislative CASESfatima pantaoPas encore d'évaluation

- EwqewqeqwewqDocument38 pagesEwqewqeqwewqShine BillonesPas encore d'évaluation

- Section 18 22 Group DigestsDocument23 pagesSection 18 22 Group DigestsjohneurickPas encore d'évaluation

- S1 (8) Ichong Vs HernandezDocument13 pagesS1 (8) Ichong Vs HernandezNeil NaputoPas encore d'évaluation

- Dumlao VS ComelecDocument4 pagesDumlao VS ComelecMaica MahusayPas encore d'évaluation

- The Economic Policies of Alexander Hamilton: Works & Speeches of the Founder of American Financial SystemD'EverandThe Economic Policies of Alexander Hamilton: Works & Speeches of the Founder of American Financial SystemPas encore d'évaluation

- Federal Constitution of the United States of MexicoD'EverandFederal Constitution of the United States of MexicoPas encore d'évaluation

- Dela Llana Vs CoaDocument2 pagesDela Llana Vs CoaEarleen Del RosarioPas encore d'évaluation

- Shooter Long Drink Creamy Classical TropicalDocument1 pageShooter Long Drink Creamy Classical TropicalEarleen Del RosarioPas encore d'évaluation

- Makalintal Vs PetDocument3 pagesMakalintal Vs PetEarleen Del RosarioPas encore d'évaluation

- Administrative Order No 07Document10 pagesAdministrative Order No 07Anonymous zuizPMPas encore d'évaluation

- Summary of Jurisdiction of Philippine CourtsDocument13 pagesSummary of Jurisdiction of Philippine CourtsXavier Hawkins Lopez Zamora82% (17)

- Makalintal Vs PetDocument3 pagesMakalintal Vs PetEarleen Del RosarioPas encore d'évaluation

- Poli Digests Assgn No. 2Document11 pagesPoli Digests Assgn No. 2Earleen Del RosarioPas encore d'évaluation

- JurisdictionDocument23 pagesJurisdictionEarleen Del RosarioPas encore d'évaluation

- Transpo CasesDocument16 pagesTranspo CasesEarleen Del RosarioPas encore d'évaluation

- SpamDocument1 pageSpamEarleen Del RosarioPas encore d'évaluation

- Summary of Jurisdiction of Philippine CourtsDocument13 pagesSummary of Jurisdiction of Philippine CourtsXavier Hawkins Lopez Zamora82% (17)

- JurisdictionDocument26 pagesJurisdictionEarleen Del RosarioPas encore d'évaluation

- Labor Case DigestDocument4 pagesLabor Case DigestEarleen Del RosarioPas encore d'évaluation

- Conflict of LawsDocument4 pagesConflict of LawsEarleen Del RosarioPas encore d'évaluation

- A Knowledge MentDocument1 pageA Knowledge MentEarleen Del RosarioPas encore d'évaluation

- Letter of Intent - OLADocument1 pageLetter of Intent - OLAEarleen Del RosarioPas encore d'évaluation

- People Vs FloresDocument21 pagesPeople Vs FloresEarleen Del RosarioPas encore d'évaluation

- Red NotesDocument24 pagesRed NotesPJ Hong100% (1)

- Tax DigestsDocument35 pagesTax DigestsRafael JuicoPas encore d'évaluation

- 2007-2013 REMEDIAL Law Philippine Bar Examination Questions and Suggested Answers (JayArhSals)Document198 pages2007-2013 REMEDIAL Law Philippine Bar Examination Questions and Suggested Answers (JayArhSals)Jay-Arh93% (123)

- Labor CasesDocument55 pagesLabor CasesEarleen Del RosarioPas encore d'évaluation

- Fire Code of The Philippines 2008Document475 pagesFire Code of The Philippines 2008RISERPHIL89% (28)

- The New National Building CodeDocument16 pagesThe New National Building Codegeanndyngenlyn86% (50)

- Torts and Damages Case DigestDocument3 pagesTorts and Damages Case DigestEarleen Del RosarioPas encore d'évaluation

- Labor CasesDocument55 pagesLabor CasesEarleen Del RosarioPas encore d'évaluation

- Tariff and Customs LawsDocument6 pagesTariff and Customs LawsEarleen Del RosarioPas encore d'évaluation

- Tariff and Customs LawsDocument6 pagesTariff and Customs LawsEarleen Del RosarioPas encore d'évaluation

- 212 - Criminal Law Suggested Answers (1994-2006), WordDocument85 pages212 - Criminal Law Suggested Answers (1994-2006), WordAngelito RamosPas encore d'évaluation

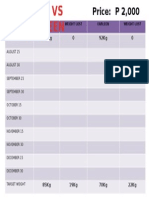

- Biggest Loser ChallengeDocument1 pageBiggest Loser ChallengeEarleen Del RosarioPas encore d'évaluation

- Public Corp Reviewer From AteneoDocument7 pagesPublic Corp Reviewer From AteneoAbby Accad67% (3)

- Dilip Chhabria v. Minda Capital PVT LTDDocument3 pagesDilip Chhabria v. Minda Capital PVT LTDvarshiniPas encore d'évaluation

- United States Court of Appeals, Tenth CircuitDocument2 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals, Tenth CircuitScribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- Censke #484602 v. Lavey Et Al - Document No. 2Document4 pagesCenske #484602 v. Lavey Et Al - Document No. 2Justia.comPas encore d'évaluation

- Notes Ilw1501 Introduction To LawDocument11 pagesNotes Ilw1501 Introduction To Lawunderstand ingPas encore d'évaluation

- MSJ Adelman Brief (Filed)Document39 pagesMSJ Adelman Brief (Filed)Avi S. AdelmanPas encore d'évaluation

- Chapter-Iii: Consent Not Exonerating From The Criminal Liability (Type-One)Document64 pagesChapter-Iii: Consent Not Exonerating From The Criminal Liability (Type-One)vinayPas encore d'évaluation

- Administrative Law: Doctrine of Primary JurisdictionDocument11 pagesAdministrative Law: Doctrine of Primary Jurisdictionwilfred poliquit alfechePas encore d'évaluation

- Specpro - Golden NotesDocument169 pagesSpecpro - Golden NotesAngel E. PortuguezPas encore d'évaluation

- The Essential Guide To Freight Claims Management Laws Fundamentals Management Staying ProactiveDocument76 pagesThe Essential Guide To Freight Claims Management Laws Fundamentals Management Staying ProactiveSergio Argollo da CostaPas encore d'évaluation

- Situations of Irregular Expenditures Based+on+COA+DecisionsDocument26 pagesSituations of Irregular Expenditures Based+on+COA+DecisionshungrynicetiesPas encore d'évaluation

- Premier Semestre: Proces Verbal de La Deliberation Unaba/Mp2Document16 pagesPremier Semestre: Proces Verbal de La Deliberation Unaba/Mp2Béchir Soumaine HisseinPas encore d'évaluation

- Revised Education Code by KVS 2013Document511 pagesRevised Education Code by KVS 2013Harminder Suri83% (6)

- I. What Is Taxation?Document4 pagesI. What Is Taxation?gheljoshPas encore d'évaluation

- Offences Against PropertyDocument4 pagesOffences Against PropertyMOUSOM ROYPas encore d'évaluation

- G.R. No. 196329 Roman v. Sec Case DigestDocument4 pagesG.R. No. 196329 Roman v. Sec Case DigestPlandito ElizabethPas encore d'évaluation

- Class Action Lawsuit Summons vs. The City of Denmark, SC For Its Drinking WaterDocument9 pagesClass Action Lawsuit Summons vs. The City of Denmark, SC For Its Drinking WaterWIS Digital News StaffPas encore d'évaluation

- Guitierrez v. Guitierrez, 56 Phil 177 (1994)Document2 pagesGuitierrez v. Guitierrez, 56 Phil 177 (1994)Clive HendelsonPas encore d'évaluation

- Andres vs. Manufacturers Hanover Trust CorporationDocument9 pagesAndres vs. Manufacturers Hanover Trust Corporationral cbPas encore d'évaluation

- Lloyds Open FormDocument2 pagesLloyds Open FormDan TurnerPas encore d'évaluation

- APPEAL - Rules of CourtDocument13 pagesAPPEAL - Rules of CourtMitch RappPas encore d'évaluation

- BSMT 1 (F) Mar D Final Exam HalinaDocument5 pagesBSMT 1 (F) Mar D Final Exam HalinaJames Ryan HalinaPas encore d'évaluation

- CIB Industrial ReportDocument4 pagesCIB Industrial ReportWilliam HarrisPas encore d'évaluation

- G.R No. 230573Document11 pagesG.R No. 230573alyPas encore d'évaluation

- Consultant For Development and Operation of National Data and Analytics Platform (NDAP)Document157 pagesConsultant For Development and Operation of National Data and Analytics Platform (NDAP)antara choudhury khannaPas encore d'évaluation

- Case Brief - Balatbat Vs CADocument4 pagesCase Brief - Balatbat Vs CAJeff SarabusingPas encore d'évaluation

- IRR Ordinance No. 483, S-2011Document8 pagesIRR Ordinance No. 483, S-2011Michelle Ricaza-Acosta0% (1)

- Unlawful Detainer Complaint 12.23.19Document33 pagesUnlawful Detainer Complaint 12.23.19GeekWirePas encore d'évaluation

- Mechanic's LienDocument3 pagesMechanic's LienRocketLawyer71% (7)

- C I Business Law: Ourse NformationDocument6 pagesC I Business Law: Ourse NformationDawoodkhan safiPas encore d'évaluation

- Model Customs Collectorate, Wazirabad Road, Sambrial, SialkotDocument5 pagesModel Customs Collectorate, Wazirabad Road, Sambrial, SialkotFaraz AliPas encore d'évaluation