Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Text 3 3 1c

Transféré par

api-243080967Titre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Text 3 3 1c

Transféré par

api-243080967Droits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

This article was downloaded by: [Harvard College] On: 04 August 2013, At: 11:29 Publisher: Routledge Informa

Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK

Journal of Jewish Education

Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/ujje20

A Review of: The Essential Conversation: What Parents and Teachers Can Learn from Each Other

Mitchel Malkus Published online: 18 Feb 2007.

To cite this article: Mitchel Malkus (2006) A Review of: The Essential Conversation: What Parents and Teachers Can Learn from Each Other, Journal of Jewish Education, 72:3, 259-263, DOI: 10.1080/15244110600990189 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/15244110600990189

PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Taylor & Francis makes every effort to ensure the accuracy of all the information (the Content) contained in the publications on our platform. However, Taylor & Francis, our agents, and our licensors make no representations or warranties whatsoever as to the accuracy, completeness, or suitability for any purpose of the Content. Any opinions and views expressed in this publication are the opinions and views of the authors, and are not the views of or endorsed by Taylor & Francis. The accuracy of the Content should not be relied upon and should be independently verified with primary sources of information. Taylor and Francis shall not be liable for any losses, actions, claims, proceedings, demands, costs, expenses, damages, and other liabilities whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with, in relation to or arising out of the use of the Content. This article may be used for research, teaching, and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, redistribution, reselling, loan, sub-licensing, systematic supply, or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/page/termsand-conditions

Journal of Jewish Education, 72:259263, 2006 Copyright Network for Research in Jewish Education ISSN: 1524-4113 print / 1554-611X online DOI: 10.1080/15244110600990189

Book Review

1554-611X 1524-4113 UJJE Journal of Jewish Education, Education Vol. 72, No. 3, October 2006: pp. 17

The Essential Conversation: What Parents and Teachers Can Learn from Each Other by Sara Lawrence-Lightfoot (Ballantine Books, 2003)

REVIEWED BY MITCHEL MALKUS

Downloaded by [Harvard College] at 11:29 04 August 2013

Book Review Journal of Jewish Education

In todays culture, most, if not all schools profess the goal of developing strong partnerships with parents to ensure successful experiences and learning for their students. As Jack Wertheimer (2005) has noted with regard to Jewish education and Jewish day schools in particular, Jewish families and educational programs do not operate in two separate spheres, but rather mutually reinforce one anotherit is no longer helpful to look at families as divorced from the Jewish educational process, any more than it is useful to imagine schools and informal education as operating independently of families (p. 8). In her elegantly written and thoroughly researched work, The Essential Conversation, Sara Lawrence-Lightfoot has produced a highly significant volume not about why a dialogue between parents and teachers is important, but about what makes this crucial exchange so difficult. The Essential Conversation marks a return for Lawrence-Lightfoot to the topic of her first book, Worlds Apart (1974), where she investigated the contours of family school relationships surrounding the parentteacher dialogue. In the current study, she has narrowed her focus to explore the microcosm of parent teacher conferences as a way of revealing and illuminating the macrocosm of institutional and cultural forces that define family-school relationships and shape the socialization of our children (p. xxi). Lawrence-Lightfoot is a sociologist by training and a professor at the Harvard Graduate School of Education. In The Essential Conversation, she employs the same form of ethnography, social science portraiture, that she has used successfully in her other research. Portraiture is a method of

Mitchel Malkus is the Education Director of The Rabbi Jacob Pressman Academy of Temple Beth Am in Los Angeles, California.

259

260

Journal of Jewish Education

qualitative research that blurs the boundaries of aesthetics and empiricism in an effort to capture the complexity, dynamics, and subtlety of human experience and organizational life (Lawrence Lightfoot & Hoffman Davis, 1997). Instead of focusing on deficiencies, this research methodology seeks to uncover what is good and healthy in an attempt to apply the findings and conceptualize theory. One of the key characteristics of portraiture is the open use of the researchers voice as a central research instrument. Lawrence-Lightfoots return, some 25 years later, to the study of parent teacher dialogue reflects both her voice as a mother of two children in their late adolescence and her personal autobiographical need to join analysis with action and intervention. The powerful portraits that she weaves with her own personal reflections and analysis make The Essential Conversation a compelling text. As Lawrence-Lightfoot shares her experiences as a mother sitting through parentteacher conferences, the reader instantly feels the emotional nature of the subject matter for her as both a researcher and a parent. The Essential Conversation begins with two rich chapters that frame the landscape against which Lawrence-Lightfoot observes the complex exchange and emotional dialogue of parentteacher conferences. Between the lines of [the] orderly, structured text of a practiced script, she notices the chaos and emotion of a subtext that is often inaudible to the participants (p. 218). As she accurately reflects, [e]very time parents and teachers encounter one another in the classroom, their conversations are shaped by their own autobiographical stories and by the broader cultural and historical narratives that inform their identities, their values, and their sense of place in the world (p. 3). The most poignant example is what Lawrence-Lightfoot terms the Doorknob Phenomenon. Just as a parentteacher conference is seemingly ending and a father heads for the door, he touches the doorknob, abruptly turns back, and passionately refers to a topic that was covered earlier in the meeting, and declares that same thing happened to me in the fifth grade, and I swear it is not going to happen to my child (p. 3). The words are delivered as an emphatic defense of the fathers child with a threatening tone that surprises even him (p. 3). What is at play here, and in all parentteacher conferences, are the deeply psychological themes and intergenerational voices that Lawrence-Lightfoot terms the Ghosts in the Classroom. Lawrence-Lightfoot offers her voice to this emotional conversation as she consciously makes the reader aware of her own ghosts. As in all ethnography, it is essential for the researcher to present her particular proclivities to the reader; in portraiture, this voice is felt throughout the narrative presentation of the data. Growing up as the daughter of middle class academics, Lawrence-Lightfoot was often the token African American girl in her school classroom. She recalls observing the sharp dissonance of values between my home and my school (p. xvi). Her parents picked their battles

Downloaded by [Harvard College] at 11:29 04 August 2013

Book Review

261

carefully, pointing out minor infractions at home with quiet corrections, but spoke up at the blatant racial, misleading, and hurtful comments that her teachers made. Lawrence-Lightfoot recalls her second grade teacher, Mrs. Sullivan, who reported to Saras parents that Saras three-month absence from school for an illness would not only make it probable that she would need to repeat second grade, but Sara might, just might not be college material (p. xiv). What Lawrence-Lightfoot remembers most about the incident was not the wounding words, but her parents tentative, awkward, and uncharacteristically demurred response to Mrs. Sullivan. Upon returning home, her parents emerged from a private discussion by saying that they knew Sara was capable of going to college and, moreover, they knew Mrs. Sullivan was wrong, and the best way to prove her wrong was for her to do excellent work. To this day, Lawrence-Lightfoot understood the primary message from her parents that she was strong and resilient; that I could do anything I set my mind to; that I could overcome prejudice, malice, and stupidity with good work (p. xv). The difficulty of parentteacher dialogues is due to the clash of values and ideals that often transpires in schools. In fact, drawing upon Willard Wallers classic text Sociology of Teaching (1932), Lawrence-Lightfoot even describes how parents and teachers can be considered natural enemies. By the different roles and functions they play in the lives of children, parents tend to have a particularistic relationship with their children, while teachers view students within a more universalistic and dispassionate relationship. This description is troubling both to Lawrence-Lightfoot and to advocates of Jewish education. As the Wertheimer (2005) study points out, Jewish educators and Jewish parents see their spheres of influence on their childrens Jewish education as mutually reinforcing. While this goal is commonly professed in Jewish schools, it is often left unfulfilled. Lawrence-Lightfoot sheds some light on the character of the relationship between parents and teachers in general when she insightfully remarks that misunderstandings, misrepresentations, mistakes in judgment, and indiscretions are unavoidable and come with the territory. In fact, she feels that one measure of candor and authenticity might be whether there is any heat, whether we see sparks fly when parents and teachers get together. Anyone familiar with Jewish schools in North America can attest to the abundance of passion that parents and educators bring to their dialogues. Lawrence-Lightfoot provides the reader with a number of chapters that focus on solutions to improving the quality of the parentteacher dialogues. The two years of research and the dozens of teachers and parents whom she interviewed impressed upon her the need to focus the discussion of the parentteacher dialogue on the child and the truths the hand can touch (p. 76) as the basis for conferencing. By this, Lawrence-Lightfoot means that evidence of student work is essential for telling the individual

Downloaded by [Harvard College] at 11:29 04 August 2013

262

Journal of Jewish Education

stories of students and their progress. As Fania White1 one of the teachers interviewed for the study recounts, there is something about confronting the evidence and feeling my seriousness of concern that gives them (parents) relieftheir eyes brighten and they are thankful (p. 81). White was one of a number of teachers who used student portfolios as the vehicle for collecting and sharing such evidence. In this respect, the teachers reflect much of the focus in the contemporary educational literature on observable evidence as the basis for student assessment. There is also a need to focus the parentteacher dialogue on developing trust between the adult parties. Storytelling, keen listening, and profound understanding on the part of both parents and teachers are essential to the process. Of course, Lawrence-Lightfoot informs us that in order for such trust to be built, parents must be willing to offer their version of the truth about their child and to be honest about their childs strengths and weaknesses (p. 101). She suggests that those who are most successful in this dialogue live on both sides of the table. With parents whose values, histories, and life circumstances are more similar to the teachers this trading of places is easier, more familiar, and natural. For others, the teacher needs to listen harderto the text and the subtext (p. 103). Lastly, it is imperative for teachers to make teacherparent communication a priority in their professional work. When parents and teachers meet only twice during the year, and their communication is limited to those occurrences, it is highly unlikely that the type of mutual trust will be established to foster open, honest dialogue. Despite the importance of the parentteacher dialogue, all the teachers interviewed in the study were not unique in their lack of formal preparation and training they received for working with families (p. 228). All of the subjects in the study stated that most of what they do well with parents results from trial and error and from learning that follows failure, from intuition and experience, or from witnessing and absorbing the ways in which their own parents and teachers encountered one another (p. 228). Lawrence-Lightfoot offers three prerequisites for deepening and enhancing the quality of parentteacher communication a) the extensive use of student artifacts as the basis for discussion; b) a focus on building trust between the adult parties; and c) increasing the frequency of contact between parents and teachers. In all cases, the schools that teachers teach in themselves, and not only the graduate schools that sought to prepare them, have an important role to play in supporting teachers and their continued development. Lawrence-Lightfoot asserts that schools must adopt a stance of welcoming parents, seeking their alliance, listening to their perspectives, honoring their ways in which they see and know their child, and seeing them as a valuable and essential resource (p. 236). Although it is not easy, the move toward

1

Downloaded by [Harvard College] at 11:29 04 August 2013

All of the subjects referenced in the book are pseudonyms.

Book Review

263

Downloaded by [Harvard College] at 11:29 04 August 2013

this focus must be viewed not as a distraction from teaching and learning but as a necessary dimension of building successful relationships with children that will ultimately support their academic success (p. 237). The Essential Conversation invites its readers to consider the complexity and the emotional aspects surrounding parentteacher conferences. It is an important work because it raises crucial questions concerning how parent roles are viewed in the educational process. Furthermore, it asks us to reflect on the dangers that lurk behind the ritual and ordered nature of the scripted dialogue that parents and teachers fall prey to every year. Lawrence-Lightfoot suggests a number of prudent ways to ameliorate the relationship between parents and teachers. In surveying this relationship, Lawrence-Lightfoot offers concrete ideas for how teacher training institutions and schools can better educate and support teachers to be successful in building healthy parentteacher bonds. For Jewish education, and Jewish schools in particular, Lawrence-Lightfoot offers an opportunity to focus on a partnership that is often acknowledged, but infrequently utilized to its potential.

REFERENCES

Lawrence-Lightfoot, S., & Hoffman Davis, J. (1997). The art and science of portraiture. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. Wertheimer, Jack. (2005). Linking the silos: How to accelerate the momentum in Jewish Education Today. New York: Avi Chai Foundation.

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5794)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- Unmanaged Snapshot - 1Document6 pagesUnmanaged Snapshot - 1api-243080967Pas encore d'évaluation

- Space Management ToolkitDocument19 pagesSpace Management Toolkitapi-243080967Pas encore d'évaluation

- 2-Data Recovery BarDocument22 pages2-Data Recovery Barapi-243080967Pas encore d'évaluation

- Nim 1Document5 pagesNim 1api-243080967Pas encore d'évaluation

- Snapshot Filter Project 12-1-2015Document15 pagesSnapshot Filter Project 12-1-2015api-243080967Pas encore d'évaluation

- Dashboardmodules LatestDocument28 pagesDashboardmodules Latestapi-243080967Pas encore d'évaluation

- Snapshot Filter Project 11-20-2015Document24 pagesSnapshot Filter Project 11-20-2015api-243080967Pas encore d'évaluation

- Paper CdsDocument10 pagesPaper Cdsapi-243080967Pas encore d'évaluation

- Inpulse Profile D-LabDocument3 pagesInpulse Profile D-Labapi-243080967Pas encore d'évaluation

- Coraid Dashboard June 13Document4 pagesCoraid Dashboard June 13api-243080967Pas encore d'évaluation

- Inpulse Wireframe2Document11 pagesInpulse Wireframe2api-243080967Pas encore d'évaluation

- Kdnapresentation Strimy 9-16-2011Document21 pagesKdnapresentation Strimy 9-16-2011api-243080967Pas encore d'évaluation

- 6-12-2014 Coraid DashboradDocument23 pages6-12-2014 Coraid Dashboradapi-243080967Pas encore d'évaluation

- Collective Interviews With QuoteDocument18 pagesCollective Interviews With Quoteapi-243080967Pas encore d'évaluation

- Interview ChadDocument5 pagesInterview Chadapi-243080967Pas encore d'évaluation

- Lucio Campanelli Interaction Designer ResumeDocument1 pageLucio Campanelli Interaction Designer Resumeapi-243080967Pas encore d'évaluation

- Asist 10 LCM PaperDocument8 pagesAsist 10 LCM Paperapi-243080967Pas encore d'évaluation

- Groupal AppDocument8 pagesGroupal Appapi-243080967Pas encore d'évaluation

- Moxie Softwaretm Customer Spaces Channels Customer Client ChristopherDocument6 pagesMoxie Softwaretm Customer Spaces Channels Customer Client Christopherapi-243080967Pas encore d'évaluation

- KM Platform-InpulseDocument6 pagesKM Platform-Inpulseapi-243080967Pas encore d'évaluation

- Proposal-For-Madagascar-By-Inqbation Inpulse FinalDocument23 pagesProposal-For-Madagascar-By-Inqbation Inpulse Finalapi-243080967Pas encore d'évaluation

- Studystream InstructionsDocument4 pagesStudystream Instructionsapi-243080967Pas encore d'évaluation

- Image Hub Inpulse ProposalDocument11 pagesImage Hub Inpulse Proposalapi-243080967Pas encore d'évaluation

- Liberia Project Plad-InpulseDocument3 pagesLiberia Project Plad-Inpulseapi-243080967Pas encore d'évaluation

- Collaboration Agreement InpulseDocument1 pageCollaboration Agreement Inpulseapi-243080967Pas encore d'évaluation

- World Bank-Inpulse ProposalDocument10 pagesWorld Bank-Inpulse Proposalapi-243080967Pas encore d'évaluation

- Screen Shot World BankDocument6 pagesScreen Shot World Bankapi-243080967Pas encore d'évaluation

- Gmail - Chevron ProposalDocument2 pagesGmail - Chevron Proposalapi-243080967Pas encore d'évaluation

- Cdcdevelopmentsolutions Technicalproposal MeDocument13 pagesCdcdevelopmentsolutions Technicalproposal Meapi-243080967Pas encore d'évaluation

- Reflections On Portraiture A Dialogue Between Art and ScienceDocument14 pagesReflections On Portraiture A Dialogue Between Art and Scienceapi-243080967100% (1)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (895)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (400)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (588)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (74)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (266)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (344)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1090)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)

- Book StudyDocument12 pagesBook Studyapi-330268622100% (2)

- 2020-02-10-Chris Voss's Tactical Empathy - Combination of 6 Reflective Listening TechniquesDocument6 pages2020-02-10-Chris Voss's Tactical Empathy - Combination of 6 Reflective Listening TechniquesRohab100% (3)

- IELTS Speaking Forecast (9-12.2020)Document22 pagesIELTS Speaking Forecast (9-12.2020)Nguyễn Chí ThànhPas encore d'évaluation

- Reaction PaperDocument2 pagesReaction PaperLoreePas encore d'évaluation

- The Art of Active ListeningDocument3 pagesThe Art of Active ListeningdecowayPas encore d'évaluation

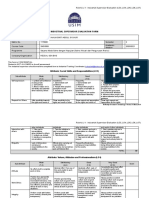

- Rubric LI-1 - Industrial Supervisor EvaluationDocument4 pagesRubric LI-1 - Industrial Supervisor EvaluationNajia SyukurPas encore d'évaluation

- Cross Cultural Case Studies With SolutionsDocument6 pagesCross Cultural Case Studies With Solutionsmridulkhandelwal64% (11)

- Common Core - ELA - UnpackedDocument28 pagesCommon Core - ELA - UnpackedmrkballPas encore d'évaluation

- Assess Your EnglishDocument40 pagesAssess Your EnglishTMPas encore d'évaluation

- An Analysis of Language Style Use in Garfield ComicDocument8 pagesAn Analysis of Language Style Use in Garfield Comicmuhsin alatas0% (1)

- 57 Killer Conversation Starters So You Can Talk To AnyoneDocument55 pages57 Killer Conversation Starters So You Can Talk To Anyonethebest100% (1)

- GCSE Japanese SpecDocument91 pagesGCSE Japanese Spec田口香子Pas encore d'évaluation

- MAKALAH Ccu Dificulty Verbal Non VerbalDocument13 pagesMAKALAH Ccu Dificulty Verbal Non Verbalselviana dewiPas encore d'évaluation

- Ford Motor Company's Digital Participation GuidelinesDocument1 pageFord Motor Company's Digital Participation GuidelinesSorcerer NAPas encore d'évaluation

- Connected, But Alone? by Sherry Turkle (Transcript)Document5 pagesConnected, But Alone? by Sherry Turkle (Transcript)Dwight Manikan Echague100% (1)

- Building Relationships by Communicating SupportivelyDocument6 pagesBuilding Relationships by Communicating SupportivelyShagufta AliPas encore d'évaluation

- Social Identity Wheel Activity - Facilitator InstructionsDocument5 pagesSocial Identity Wheel Activity - Facilitator Instructionsapi-282764739Pas encore d'évaluation

- English 10 - Q1 - Module-5 - Lesson-1 For PrintingDocument20 pagesEnglish 10 - Q1 - Module-5 - Lesson-1 For PrintingLilay Barambangan100% (1)

- 10 Tips For Call Center Etiquette ExcellenceDocument12 pages10 Tips For Call Center Etiquette ExcellenceArafat IslamPas encore d'évaluation

- Oral-Comm Q2W1Document6 pagesOral-Comm Q2W1Elmerito MelindoPas encore d'évaluation

- Adventure Tourism The Freedom To Play With RealityDocument19 pagesAdventure Tourism The Freedom To Play With Realityjfk100Pas encore d'évaluation

- LP Over and Under The SnowDocument5 pagesLP Over and Under The Snowapi-311345739Pas encore d'évaluation

- TN-British and American Short StoriesDocument5 pagesTN-British and American Short StoriesMiquel CochPas encore d'évaluation

- Context: - Discourse That Surrounds A Language Unit and Helps To Determine Its InterpretationDocument3 pagesContext: - Discourse That Surrounds A Language Unit and Helps To Determine Its InterpretationEDSEL ALAPAGPas encore d'évaluation

- Lesson Plan - Ser and Estar IDocument4 pagesLesson Plan - Ser and Estar ITeresa McCormackPas encore d'évaluation

- Planning Let's Speed Up 3Document49 pagesPlanning Let's Speed Up 3Patricia Guevara de HernandezPas encore d'évaluation

- b2 Skill DevelopmentDocument204 pagesb2 Skill DevelopmentTrọng DuyệtPas encore d'évaluation

- Passport To Academic Presentation PDFDocument12 pagesPassport To Academic Presentation PDFdefiaaa14% (7)

- Note de Seminar Management-IDDocument18 pagesNote de Seminar Management-IDconstantin cocaPas encore d'évaluation

- E3 Opa # 2 Unit 9 IndividualDocument2 pagesE3 Opa # 2 Unit 9 Individualyessenia Velarde0% (1)