Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Porn Laid Bare Mowlabocus

Transféré par

Emerson da CunhaDescription originale:

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Porn Laid Bare Mowlabocus

Transféré par

Emerson da CunhaDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

http://sex.sagepub.

com/

Sexualities

Porn laid bare: Gay men, pornography and bareback sex

Sharif Mowlabocus, Justin Harbottle and Charlie Witzel Sexualities 2013 16: 523 DOI: 10.1177/1363460713487370 The online version of this article can be found at: http://sex.sagepub.com/content/16/5-6/523

Published by:

http://www.sagepublications.com

Additional services and information for Sexualities can be found at: Email Alerts: http://sex.sagepub.com/cgi/alerts Subscriptions: http://sex.sagepub.com/subscriptions Reprints: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsReprints.nav Permissions: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav Citations: http://sex.sagepub.com/content/16/5-6/523.refs.html

>> Version of Record - Aug 30, 2013 What is This?

Downloaded from sex.sagepub.com at UNIV FEDERAL DO CEARA on November 7, 2013

Article

Porn laid bare: Gay men, pornography and bareback sex

Sharif Mowlabocus

University of Sussex, UK

Sexualities 16(5/6) 523547 ! The Author(s) 2013 Reprints and permissions: sagepub.co.uk/journalsPermissions.nav DOI: 10.1177/1363460713487370 sex.sagepub.com

Justin Harbottle

Terrence Higgins Trust, UK

Charlie Witzel

Terrence Higgins Trust, UK

Abstract This article details the preliminary findings from Porn Laid Bare, a collaborative research project between the University of Sussex and the Terrence Higgins Trust, Brighton. We explore the multidimensional relationship that respondents identified as having formed with pornographic material, together with its role within gay male subculture. We then consider how interview respondents understood and conceptualised bareback pornography. Our findings reveal consistent contradictions between general discussions of gay pornography and specific discussions of bareback representations. Utilising Deans (2009) work on bareback subculture and the ambivalent gift, we develop a critical reading of these contradictions in order to identify the methods by which the anxieties and pleasures of bareback pornography were handled by respondents. Keywords Bareback, gay men, gift-giving, pornography, sexual health

The academic study of pornography has been revitalised during the last 10 years with the publication of numerous anthologies and monographs engaging with pornography from a range of critical perspectives (see for example, Attwood, 2009; Lane, 2000; Morrison, 2004b; Paasonen et al., 2007). Extending the work undertaken by second-wave feminism, scholars such as Jensen (2007), Kendall (2005) and Bishop (2007) have rearticulated the problematic gender dynamics

Corresponding author: Sharif Mowlabocus, University of Sussex, Silverstone 338, University of Sussex, Brighton, BN1 9RH, UK. Email: S.J.Mowlabocus@sussex.ac.uk

524

Sexualities 16(5/6)

that structure much commercial pornography. Meanwhile, and echoing Williams (1992), authors such as White (2003), Jacobs (2004) and Attwood (2007) have argued for a re-evaluation of pornographys potential to liberate and subvert gendered norms. Within the specic arena of gay male pornography, academic studies have explored a variety of issues within sexually explicit representations of malemale desire. These include the (often problematic) representation of gender dynamics (Escoer, 2003; Stoltenberg, 1991), and of race (Fung, 1991; K Mercer, 1991, 1992; Radel, 2001); the issue of whether pornography can have a pedagogic function (Kendall, 2004, 2005; Patton, 1991, 1996) and the role of pornography in the lives of gay men (Burger, 1995; Dyer, 1985; Morrison, 2004a). The emergence of bareback pornography (pornography that depicts unprotected anal sex UAI between men) in the late 1990s, and its journey from that of niche kink to a feature within a wide variety of gay male pornography, is perhaps the most notable shift in gay male pornographic content. During the mid-1980s, the USdominated gay porn scene sought to normalise condom use within pornography (Mowlabocus, 2010). This was in response to the burgeoning HIV/AIDS crisis of the mid-1980s, the eects of which were rst felt in the gay male communities of coastal cities such as Los Angeles, New York and San Francisco. Unlike heterosexual porn studios (which relied on regular testing and surveillance of performers and their on-screen sexual contact1), commercial gay male pornography adopted the condom code in a bid to protect their actors (and their reputations). In the UK, anxieties over the legal status of gay pornography meant that the 1980s was also a time when over-the-counter gay pornography often shied away from hardcore scenes of penetration and erect penises. While these anxieties dissipated during the 1990s,2 by the time hardcore material was freely available, the condom code had become an entrenched part of commercial gay male pornography. The result of this policy was manifold and meant that, up until 2000, it was rare to nd gay pornography featuring sex without condoms for sale in gay bookshops and sex stores. Today the situation is markedly dierent and it is now uncommon to nd such stores not stocking material that explicitly markets itself as raw, risky, bareback or condom-free (see Rofes, 1998 and Escoer, 2009 for further discussion). The representation of unprotected anal sex (UAI) has gone from being an under-the-counter commodity, to a legitimate product marketed in similar ways and via the same distribution channels as other forms of gay pornography. It is this movement from margin to centre that provides the impetus for the research under discussion here. Earlier studies have identied the formation of disparate barebacking communities and have often positioned barebacking at the periphery of gay male culture (Scarce, 1999; Tewksbury, 2003). While not disputing these earlier claims, the authors of this article identify an increasing mainstreaming of representations that depict bareback sex. Recent forays into bareback pornography by larger commercial studios such as Sean Cody, Corbin Fisher and Chaosmen are good examples of this normalising of bareback pornography, with UAI being incorporated into the existing aesthetic of these studios.

Mowlabocus et al.

525

Of course this journey from margin to centre has not been without controversy. Successive editors of Boyz magazine, the popular weekly scene publication, have spoken out against those who choose to bareback and those who seek to prot from selling representations of UAI. Meanwhile bareback pornography has been discussed in the British Parliament, with Anne Milton, Under-Secretary of State for Health, calling for an end to the promotion of bareback pornography on World Aids day, 2010 (Hansard, 2010). These recent criticisms echo concerns raised a decade earlier by Signorile (1997) and Rotello (1997). Yet while there has been a great deal of discussion over the issue of bareback sex and bareback subculture, there has been relatively little research into bareback pornography and even less that has focused on the role that bareback pornography is playing in the lives of gay men today. This article sets out to respond to this dearth of academic commentary and explores how gay men approach pornography (in general) and bareback pornography (as a specic genre) in dierent ways.3

Methodology

Beginning in December 2010, and with funding from the Terrence Higgins Trusts Informed Passions project (itself funded by the Big Lottery Fund), the research employed a two-stage methodology that involved a textual analysis of a corpus of pornographic material and a series of focus groups with gay and bisexual men based in the Brighton and Sussex region. In the rst stage of the research a total of 125 pornographic scenes taken from popular websites and DVDs were analysed and coded separately by the three researchers. Data from the coding exercise were triangulated and a set of common themes, generic conventions and sexual markers were identied. These themes and markers centred around dierent sexual practices, the number of performers involved in each scene, the dierent body types displayed, the representation of ejaculation and the use of condoms. Importantly, both sexual and non-sexual elements of each scene were analysed For example, the location of the scene was recorded, as was the quality of the footage and whether the material was user-generated or commercially produced. The themes underpinned the development of a set of interview questions that were then tested using a pilot group and with an external moderator. Following a redrafting of the interview script based on feedback and a review of the pilot interview transcript, participants from the Sussex region were recruited to a total of seven focus groups that lasted between 90 minutes and two hours. Focus groups were chosen as the preferred method for interview as they have previously proven to be a useful method for data collection within health and medical research (see Kitzinger, 1994; Powell and Single, 1996) and have also been used eectively in previous research focusing on gay male pornography (Morrison, 2004a). Recruitment utilised online methods (including the use of social networking sites and gay dating sites) and oine methods that employed the Terrence

526

Sexualities 16(5/6)

Higgins Trusts local outreach scheme to distribute publicity material and promote the research in bars, clubs and PSEs.4 The sole exception to this recruitment policy was one focus group interview that involved participants drawn from the London region. Owing to diculties in recruiting younger HIV positive men locally, the researchers extended their eld of recruitment in order to secure an interview with this less visible (and perhaps also smaller) but no less important cohort. Taking into account recent research that has identied dierences in HIV transmission and testing rates according to age group (Smith et al., 2010), focus groups were divided into two age categories, 1825 and 4055, providing the researchers with an opportunity to explore dierences in attitudes and responses according to age. Respondents were then subdivided according to HIV status in order to identify dierences in perceptions of bareback pornography according to serostatus (see also Davis et al., 2006; Gendin, 1997; Goodroad et al., 2000). Excluding the pilot group, 50 men were interviewed. Following transcription, the interview data were uploaded to qualitative data analysis software before being coded by all three researchers using a grounded theory approach (Glaser, 1992) Individual coding was then cross-referenced in order to triangulate data and articulate the key ndings.

Doing things with porn: Gay mens uses of pornography

The importance of pornography within gay male subculture has been well documented previously (Burger, 1995; Macnair, 1996; J Mercer, 2004; Strossen, 1995; Watney, 1996; Waugh, 1985, 1996). As Dyer noted almost 30 years ago:

Gay porn asserts homosexual desire, it turns the denition of homosexual desire on its head, says bad is good, sick is healthy and so on. It thus defends the universal human practice of same sex physical contact (which our society constructs as homosexual); it has made life bearable for countless millions of gay men. (Dyer, 1985: 123)

Two decades on, very similar sentiments were expressed by both older and younger respondents in the focus groups:

I think with . . . with porn like, especially with people my generation like there wasnt anything on TV. So its . . . the only place to go to, to nd out what being gay is about like, so you kind of grow up with it like thats the only place, like no one else talks about, it doesnt get talked about in school, it doesnt get talked about on TV. (1825 HIV Negative cohort 2) we dont see other gay men other than in porn really. (1825 HIV Negative cohort 2)

Such claims provide one explanation behind why gay male culture has historically been more accepting of pornographic imagery than mainstream society (see Mowlabocus, 2010) and why, for instance, gay sex shops are ascribed a far

Mowlabocus et al.

527

more legitimate place within the environs of the gay village than the local high street:

what immediately springs to mind is, theres a sex shop in Hove called Taboo. You cant see in the windows. It says . . . It says exactly what its there for, whats inside, but you cant see inside. Theres no imagery, theres nothing. Thats there. You look at St James Street [the centre of Brightons gay village] and its all there, its all open, so were not hiding anything [general agreement from others]. In a way, its just there, part of life, its mainstream, whats your problem? (4055 HIV Positive cohort 1)

While respondents felt that the contemporary mediascape was becoming increasingly open to representations of (some forms of) gay masculinity, these continued to be staid, safe and polite, in comparison to the plethora of representations that feature heterosexual identities and practices.

Yeah, I mean you dont really see it that often in like TV programmes, its mainly like a kiss, more like you know, a touch of a hand, its not really anything sex based, its, you know, its very . . . very, very frowned upon. (1825 HIV Negative cohort 2) [the media] seems to hype up the fact theres going to be a gay kiss for six weeks before it actually happens, like on . . . what is it, like at the moment . . . and then its only ever a kiss, like what . . . you could go a step further with like heterosexual on TV, but not, I think with gay men. (1825 HIV Negative cohort 2)

Respondents also identied the various ways in which they used pornography in their everyday lives. By far the most popular understanding was its perceived educational dimension, oering instruction on, and experiences of, gay male sexual practices:

Porn was more like . . . its exciting and erm, when you nd . . . when you want to nd out about it more, its kind of like a research tool because you want to nd out the right positions to do, the right methods, you know, the right actions, to help . . . just to help pleasure someone properly, you know. And you kind of . . . it sounds weird, but you kind of learn that in the back of your head and you keep it there. (1825 HIV Positive cohort 1) One benet maybe is for erm younger people who come out as being gay or realise that they are gay that might be the rst err thing that they do to see what its about. (4055 HIV Negative cohort 2) Its got two main, as I see it, aims or . . . Its to entertain, and theres also to educate. (40 55 HIV Positive cohort 1)

Although for one participant, not seeing gay pornography during his formative years was, he felt, perhaps a positive absence to his emerging sexual identity:

I was kind of relieved that I didnt see it, I think it would have actually err inhibited me coming out because it was all very its this sort of shit again, its all very beautiful, hung like a donkey [Tom of] Finland types, you know. (4055 HIV Negative cohort 2)

528

Sexualities 16(5/6)

This latter response, the sole contradiction to an overwhelming belief in the (positive) pedagogic dimension that gay pornography had in participants lives, echoes concerns raised by scholars regarding the challenges that gay pornography might pose for its audience in terms of body image issues, sexual and social condence, prejudice and discrimination (see Stoltenberg, 1991 and Ayres, 1999 for discussion). As important as these issues may be5 this criticism of pornography was but one voice amongst an otherwise positive attitude towards the educational use of pornography.

I think pornography is a lot of peoples rst erm encounter with sex . . . particular gay sex, erm in that they, you know, this isnt . . . something that they will be coming across quite regularly, erm its not something talked about for a lot of people and not in families or around their friendship group . . . its certainly important in just the way in which people sort of rst . . . rst become aware of sex and how it is supposed to be done. (1825 HIV Negative cohort 1)

Beyond its perceived pedagogic dimension however, respondents also regularly identied how gay pornography functioned as an aid to forming and maintaining relationships with other gay men, be they sexual, social, virtual or imagined:

I was, yeah, I was . . . I was going to say erm talking about my own experience erm I always found it exciting to . . . to go shopping for some gay porn with my partner, and either do whatever was showing or if its crap have a good laugh about it. (4055 HIV Negative cohort 2) I think that gay people generally will talk, or share porn with each other more openly than straight people will . . . And not only with people that you are shagging or have shagged or want to, but also with friends where you dont necessarily have a sexual relationship. (4055 HIV Positive cohort 1) Well I think the fact that lots of people have access to the internet and to gay pornography means that if you are living in a community where you like you cant come out whatever and you can see that on the internet you sort of think, okay well theres people like me out there, theres, you know, thousands and thousands and thousands of people out there like me that do this, this is . . . it might help them accept themselves. (1825 HIV Negative cohort 1)

This latter quotation builds upon Burgers (1995) discussion of gay porn consumption in socially conservative states in the USA and highlights two signicant factors regarding gay male pornography and gay male life. Firstly, the respondent identies how, outside of metropolitan areas in which gay villages are perceived to thrive, gay men continue to face obstacles that may limit their ability to come out and to be open about their sexual identity. As the life narratives and oral histories of gay men demonstrate (Hall-Carpenter Archives, 1989; Porter and Weeks, 1991) one of the most challenging aspects of living in such environments is the lack of contact with other gay men, and the sense of isolation and loneliness that this can engender.

Mowlabocus et al.

529

Secondly, and leading on from this point, the respondent identies how, in contexts in which other gay men are equally hidden from view, internet-based pornography might be one way of forging a connection with other gay men that exist out there. Respondents regularly cited the internet as an important resource for people when it came to dealing with issues of sexual identication or accessing sexual communities:

I never knew anybody gay. Obviously there were people that I didnt know because it wasnt as open, there was no areas like this. So I looked on the internet and then I started to identify like other gay people and then in . . . in the coming out years when youre rst discovering yourself thats probably the main way to do it. Because you havent got the condence to walk into a gay bar and actually approach someone. You . . . you kind of nd yourself looking at porn a lot more and going on the dating websites, just chatting around. (1825 HIV Positive cohort 1)

While the foregoing quotations are characteristic of the type of responses articulated across the dierent cohorts, one use of pornography appeared to be identied solely by older HIV positive respondents. In this cohort, several interviewees suggested that pornography had been used as a means of gaining sexual satisfaction without having to engage with the gay scene. While for others, the issue of medication-related erectile dysfunction was overcome through the use of sexually explicit material:

As somebody whos been positive for a long time, before Viagra, with a non-working dick, at least I could get some stimulation from watching porn, and that generally has gone on as you get older and the places you feel comfortable going out in perhaps become more limited. And its one way of going out without leaving your home. (4055 HIV Positive cohort 1)

The (over) investment in the penis as the primary site of sexual pleasure within gay male subculture, twinned with the ongoing diculties that HIV positive men face in terms of social and sexual discrimination have been well documented (see for example Sandstrom, 1996). While interviewees were not asked to directly comment on these two issues, it is reasonable to surmise that a penile-centric culture (in which a good dick is a hard dick) and ongoing HIV stigma have created a context in which pornography has become both a preferable and more satisfying alternative to sexual interactions elicited via the traditional gay village. One respondent later discussed how pornography provided a backdrop to his (non-penile) sexual enjoyment, particularly in sex-clubs and S&M venues;

. . . if youre watching as part of the backdrop [at a sex club], then its part of the backdrop. You take a break, take a breather, then its going on and . . . [Ive] used it in that way and its just running all the time, and thats great . . . (4055 HIV Positive cohort 1)

530

Sexualities 16(5/6)

This statement was made within the context of a discussion regarding the importance of ejaculation in gay pornography. For this respondent, the use of pornography as sexual wallpaper during his night-long sexual scenarios meant that pornography wasnt about getting o so much as providing a breather in between episodes of (or during an extended episode) group sex. This comment also underscores the fact that pornography should not be seen as existing outside of other aspects of gay male sexual/leisure practices, but as part of these practices and the commercial industries that cater to them. Taken together, the responses demonstrate that for many gay men pornography is more than just material for masturbation.6 Whether used as a means of learning new sexual techniques, validating a sense of self, nding an alternative to conventional sexual practices or a method for supporting existing social and sexual relationships, respondents demonstrated the multifarious ways in which they had incorporated pornography into their own lives. Our research builds upon earlier ndings around gay mens use of pornography and continues to identify the important role pornography plays within gay male culture and gay mens lives and, therefore, the ongoing attention that sexual health promotion must pay to both the pleasures and politics of pornography. It also demonstrates how central the internet has become in terms of nding and consuming dierent types of pornography but also in terms of accessing a gay world that is, at times, physically inaccessible. However, while respondents openly discussed the multiple uses of pornography in general, there was one type of pornography that was clearly marked out as being solely for the use of masturbation and sexual fantasy: barebacking.

Some people watch that type of porn because they dont have that type of sex: Bareback pornography and the ambivalent gift

The complex and multifaceted relationship that participants identied forming with pornography was noticeably absent from discussions of bareback pornography, with the sole exception of the older HIV positive cohort. Having spent over an hour discussing the ways in which they related to pornography, respondents immediately began policing their use and understanding of bareback pornography as soon as it became a topic of conversation, often while admitting that they used and enjoyed such material:

What [respondent] has said there, that porn has a role as fantasy, that people dont necessarily, although we did say it has an educative aspect, people dont necessarily use and copy exactly what theyre seeing, but theyre using it as a means of escapism, fantasy escapism. (4055 HIV Positive cohort 1) The only thing I can actually say is the fact that porn is fantasy. (4055 HIV Negative cohort 1)

Mowlabocus et al.

531

No, I was just going to say then it falls into sort of fantasy there. Its not saying, Go out and do this, or You must like this, or whatever but I think it just falls into the fantasy part of it. (4055 HIV Negative cohort 1) In porn its important its not real kind of thing I think sometimes, yeah. (1825 HIV Positive cohort 1)

At this point respondents often (re)framed their early responses about all pornography, asserting that pornography had no relationship to their lives whatsoever. In other words, having earlier identied a plethora of meanings that they attached to pornography, respondents went on to contradict these assertions during the discussion of bareback pornography. As such, all pornography moved from being malleable and culturally relevant to being purely about fantasy when discussed within the context of UAI. How might we account for this seeming contradiction? How can we understand this sudden severing of pornography from reality? What might such a contradiction reveal about gay mens relationship to bareback pornography? One way of comprehending this disparity would be to write such contradictions o as a case of bad faith; that the contradictions and negations contained in their responses serve as proof that interviewees were unwilling to acknowledge the stark reality that bareback pornography is aecting the way they conceptualise and think of gay sex, and that what they enjoy watching on screen is in fact doing them harm. This version of the direct media eects argument is, at best, problematic, because it seeks to identify a single cause upon which to attribute a particular social problem. In doing so, it marginalises the respondents ability to manufacture, frame and negotiate complex textual meanings (see Hall, 1973). Meanwhile the advent of the circuit of culture response to the media eects debate (Du Gay, 1997) has decentred the primacy (and power) of the text over the consumer, not least in relation to the consumption of media texts by LGBTQ audiences (see Gross, 2002; Medhurst, 1998). Put simply, a cause and eect explanation of these contradictions serves to foreclose more productive discussions of this issue discussions that are sensitive to the complex negotiation work that respondents demonstrated in their answers. Echoing Halls assertion regarding hegemonic, negotiated and oppositional readings of texts (1973), participants identied the possibility that bareback pornography could be in the mix when it came to identifying why gay men might have UAI, but that it was far more complex than simply a case of cause and eect:

Yeah, I mean it depends on the individual. Some people, no matter what you tell them not to do, theyll want to do it anyway. There are other people who have a, er . . . maybe a status thing around it. (4055 HIV Negative cohort 1) You couldnt, I dont think, say it will make someone have bareback sex but when someone chooses to have, you know, unsafe sex, I think its in the mix. I think its signicant; its not huge. I think there are far greater things but I think its, I dont

532

Sexualities 16(5/6)

think its that big. I think its certainly there and it will . . . yeah, its there. (4055 HIV Negative cohort 1)

Of course, with recent calls such as those made by Anne Milton (Hansard, 2010) to censor or otherwise ban bareback pornography, our participants may have been unwilling to consider a direct causal relationship between bareback pornography and their own sexual practices. However, if this was the case, the fact that respondents were later willing to cite bareback pornography as one possible reason behind rising HIV transmission rates, but only one among many others,7 suggests that they were not living under some form of queer false consciousness, but were instead constructing articulate and multifaceted readings of bareback pornography. Given this fact, we seek an alternative, more nuanced understanding of participants apparent reticence to relate bareback pornography (indeed all pornography) to their own lived realities having previously articulated an elasticity between their consumption habits and sexual identications, practices and communities. Closer inspection of the transcripts reveals a high degree of concern during the discussions of bareback pornography. Respondents were clearly worried that representations of UAI might be having a negative eect on the sexual health of gay men. However, echoing previous studies of potentially harmful products (Gunther, 1995; Honer and Buchannan, 2002; Lo and Wei, 2002; Shin and Kim, 2011) respondents were reluctant to identify their own consumption as potentially harmful. Instead, while advocating the right to watch bareback pornography, their enjoyment of this material and the naturalness of UAI, respondents regularly displaced any anxiety onto an absent (assumingly vulnerable) Other. In many ways, this echoes historical attitudes towards pornography, whereby women, children and the working class were seen as impressionable and vulnerable to the eects of sexually explicit materials perceptions often constructed and maintained by middle-class men who saw themselves as above any such vulnerability (see Kendrick, 1987). This created a space in which interviewees could enjoy bareback pornography, while shifting anxieties about its impact onto an out group. Most often, and perhaps unsurprisingly, given the organisation of the cohorts, this absent other was identied through age:

The other [younger] group, I think, wont be necessarily exposed to as much life as we have and so well hold dierent views. The uneducated little twats. (4055 HIV Negative cohort 1) Yeah. It is generational, so the people coming along who are young and growing up today, etc. in 20s, 30s, whove only ever known that era since condoms were introduced, will take a dierent view than my looking at a longer period of time. (4055 HIV Positive cohort 1) You get that older generation coming out, they explode of the closet and they just do all the things they thought they missed and its thats put them more at risk because theyre not starting to think about what theyre doing. (1825 HIV Negative cohort 1) Im not being rude at all but do you know because theyre older they might be more desperate, more willing just to have sex with anyone that they meet whereas younger

Mowlabocus et al.

533

people have maybe got more opportunity to pick who they have sex with? (1825 HIV Negative cohort 1)

Although in at least one group, the absent other was dened as of a lower socioeconomic status with limited education:

Yeah I think that would depend on the level of education of the individual watching the porn . . . I think our backgrounds, highly educated, weve gone to university, it would be quite interesting for me to see what somebody who had not nished their GCSEs but didnt receive proper sexual health education at school would say. (1825 HIV Negative cohort 1)

Such displacement is commonly found within third-person eects research, which centres on textual representations that are coded as physically, psychologically or socially problematic or risky (see McLeod et al., 1997 see also Lo and Paddon, 2001). These texts can include lms and television programmes that include sexual or violent content, or which feature anti-social or risk behaviours such as excessive alcohol consumption, smoking and taking drugs. In third-person theory, research participants are asked to comment on their perception of the risks that potentially dangerous or inuential texts might have on others. While it can be argued that the critically awed8 media eects model continues to echo in the background of third-person research, the latter does seek to step away from direct cause and eect and instead considers audience perceptions and community reactions. It might therefore appear that third-person theory (see Davison, 1983; Gunter, 1995; JD Jensen and Hurley, 2005; Lo and Paddon, 2001; Lo and Wei, 2002; Rojas et al., 1996) oers an obvious framework through which to interpret our ndings. However, there are diculties in applying this concept to the research under discussion. These diculties pertain to the already acknowledged investment in, and multiple uses of, pornography within gay male subculture. As previously discussed, pornography was regularly seen as a positive and life-enhancing cultural text that oered more than just an opportunity to get o and even when it did only oer the latter, getting o was never framed in negative terms. As has been previously discussed, for some respondents, getting o on pornography could in fact oer a valuable alternative to real sex. This enjoyment of pornography extended to bareback material. What makes the displacement activities witnessed in focus group interviews so poignant is that the perceived risks of bareback pornography9 also appear to be central to the erotic economy of the pornographic scene. In other words, the self same element that made many respondents express anxiety about the potential eect of bareback porn was also what made it appealing:

Its the taboo, youre not supposed to do it. Its something you are not supposed to do yet you are watching two guys do exactly that. Emphasising the shots and the angles to sensationalise it almost. (4055 HIV Positive cohort 2)

534

Sexualities 16(5/6)

I mean, this idealism, of the thing that you cant do because safer or safe sex or whatever has become such a central point to a lot of peoples gay sex lives that now theres this idea that unsafe sex or bareback sex is more real, more natural, more, whats the word, more intimate, its more intimate to do that and because its a thing that youre not allowed to do, youre saying about this, its a taboo. (1825 HIV Negative cohort 1) I would think its because barebacking is really risky, but its quite erotic as well, they are being naughty and doing that. (4055 HIV Positive cohort 2)

As such, the source of much of the anxiety surrounding bareback pornography was also the site of its erotic meaning. In other words, respondents regularly found bareback pornography to be both something that they enjoyed and something that they felt might be dangerous for others. This poses a challenge for third-person theory, which has hitherto framed the rst-persons understanding of the material under investigation as either neutral or negative (see for example Lo and Paddon, 2001). Third-person theory therefore struggles to contain both the promise of taboo sexual activity that respondents identied as central to bareback pornography and simultaneously the anxieties that that self-same promise embodied for them (and which was displaced onto an absent other). Faced with the sexual, social and erotic ambiguity that bareback pornography appeared to present to our participants, it is to other writings on this sexual practice that we turn our attention. Deans (2009) ethnography of bareback subculture in the USA is perhaps the most sustained discussion of the culture of barebacking including its pornography. Borrowing from Rahejas (1988) work on ritual giftgiving, Dean asserts that bareback sex and, in particular, semen exchange should be understood as an ambivalent gift one that is burdened with meaning and which is at once auspicious and inauspicious: binding and potentially threatening:

The fundamental ambivalence associated with poz-cum is revealed in a ash as two aective worlds collide one in which viral transmission is a highly erotic act and the other in which it is ethically abhorrent . . . There remains an irreducibly erotic component to giving regardless of what is given because the act of giving connects the parties involved, making one body of two (or more than two). (Dean, 2009: 8283)

Anthropological theories of gift giving are almost a century old, with the work of Mauss (1925) widely regarded as the rst prominent study of gift giving culture. This early work has regularly been critiqued10 for the way in which it conceptualises the motivations behind reciprocity. However, as Carrier (2005) notes, there has been a recuperation and reorganisation of Mausss conceptual framework since the 1970s by scholars working mostly on the Indian subcontinent. He cites the work of Raheja (1988), whom Dean also turns to for inspiration. There is not space here for a full and complete exposition of Rahejas work. However, of primary importance to our discussion is her explanation of how rituals

Mowlabocus et al.

535

involving specic Dan obligated gifts are invoked to transfer unwanted, evil or dangerous elements from the donor to recipient:

In Phansu, the contextual equivalence of the Brahman, the Barber, and the Sweeper as appropriate recipients of dan, the reluctance of all three to accept dan, and the fact that sin and inasupiciousness are conveyed to all three as they accept dan from Gujar jajmans make it evident that this ambivalence about the acceptance of dan cannot be understood simply with reference to the supposed inferiority of the donor. Religious gifts can and indeed must be given to Sweepers and Barbers as well as to Brahmans if the well-being and auspiciousness of the donor are to be maintained. (Raheja, 1988: 34)

It is the concept of the inauspicious Dan the transferring of perceived danger or future malady that is at the heart of Deans appraisal of semen exchange during UAI:

What Raheja calls the transferal of inauspiciousness is not just symbolic in bareback subculture, because HIV marks semen with an irrevocable ambivalence. Although the subcultural project of destigmatizing HIV involves an eort to transform it from a punishment into a gift, the older connotation nevertheless lingers. (Dean, 2009: 81)

To repeat, there are marked dierences between Deans eld of study and that under investigation here. Dean is focused on a marginalised subculture dedicated to UAI whereas this project has been interested in representations of UAI as they operate within mainstream gay subculture. Yet despite these dierences, and taking into account both the earlier and more recent work on gift reciprocity and danger, one can trace a line between Maussian concepts of Hua11 Deans appropriation of Rahejas work and the anxious responses of research participants in this study. Bareback pornography represents a form of gift12 (dan) that is both highly ambivalent and epistemologically unstable. For the respondents in this research bareback pornography carried within it competing meanings, articulating both a desire to watch unprotected raw sex and a nervousness about what such a desire meant. Of course, unlike the gifts identied by Mauss, in bareback pornography, the spirit of the gift cannot be returned; this is not a material gift that can necessarily be exchanged.13 However, the anxiety that respondents identied may yet be conceptualised as an anxiety over the dangerous spirit of bareback porn and dealt with accordingly. Working through Deans appropriation of Rahejas thesis, we can deconstruct bareback pornography along similar lines, whereby the bareback text comes to represent an ambiguous gift within gay male subculture and a collision of two aective worlds (Dean, 2009):

Well, I was just going to say on this gentlemans point about bareback being a fetish . . . at that end of the day, originally . . . To use a condom is a very good thing,

536

Sexualities 16(5/6)

of course, in terms of health but it is an artice. Its that somebody told you that you need to do it for whatever reasons and so if youre now looking at bareback sex as a fetish, then they have culturally . . . Theyve made it a fetish. (4055 HIV Negative cohort 2)

Representing as it does a manifold increase in the transgressive nature of gay pornography, bareback pornography acknowledges its outsider status precisely because it is this status that it trades on. While bareback pornography is not solely a matter of depicting UAI14 the penetration of the anus by one or more unsheathed penises is nevertheless central to bareback pornography. As with the vast majority of pornography, bareback porn relies on being understood as naughty, taboo or edgy. Like some other pornographies15 bareback pornography is reliant on the fact that, in representing a disavowed or stigmatised sexual practice, it speaks to the desires of its consumers. These desires are often denied expression within other spheres of gay male culture (including Health Promotion targeted at gay men), and are otherwise repressed in favour of normative (and potentially life-arming) behaviours. It is within this context that we must understand bareback pornography as a gift no matter how ambiguous. Like a gift, it articulates a connection between the gift-giver and the gift-receiver and (when it works, when the gift is accepted) it acknowledges both the desires of the receiver and the fact that those desires are recognised by the giver. By acknowledging the consumers desires we come to see the ambiguous dimension of the bareback gift. Bareback pornography speaks to desires that some gay men may otherwise spend a lifetime policing and sublimating. Bareback pornography not only acknowledges this sublimation, it responds to the reasons behind it (HIV prevention work, sexual safety) at the same time that it depicts the conquering or refusal of such sublimation. Viewed from this perspective, bareback pornography is a mirror that gay male culture holds up to itself; the ensuring reection is one that it struggles to comprehend because what it sees what it desires does not line up with what it thinks or, rather, what it has learned to think is appropriate sexual behaviour. The position that bareback pornography occupies in contemporary gay male culture was something that many respondents were both excited by and anxious about as identied by these two respondents.

With my friend its quite a consensus, that we nd it more exciting, even if we thought that maybe risky for people, to support bareback porn industry but there is quite a consensus. (1825 HIV Negative cohort 1) I would think its because barebacking is really risky, but its quite erotic as well, they are being naughty and doing that. I really dont know. It really doesnt bother me with a condom or not. Some people just like to see esh on esh, thats all. (4055 HIV Positive cohort 2)

For many respondents, identifying that they watched and enjoyed bareback pornography was not at all problematic. While some respondents expressed strong

Mowlabocus et al.

537

dissatisfaction with others use of this material, the overwhelming majority were comfortable identifying their consumption of such material and did not see such viewing habits as stigmatised. Yet while there was little ambiguity expressed about watching bareback pornography, there was a high degree of anxiety around its perceived meaning and eects. Developing Maussian gift-theory (by way of Raheja) allows us to understand the seeming contradiction that respondents articulated in their discussion of bareback pornography their desire for it and anxiety about its potential eects. Faced with this desire/anxiety tension, respondents appear to have chosen to divide the gift of bareback pornography into two separate (though inexorably connected) parts. We here characterise these two parts as the erotic endowment and the inauspicious bequest16 (see Figure 1). The erotic endowment is that which the participants themselves took from bareback pornography and contains within it all that the respondents found appealing in bareback pornography (potential risk, cultural taboo, sexual transgression, rebellion). Like other forms of endowment, the erotic endowment here is positive in tone and meaning, oers a transferral of some form of capital and seeks to benet the recipient. It also places the respondent in a comparatively active position the erotic endowment is something that they took away from bareback pornography. Meanwhile, the inauspicious bequest is that element of the gift that participants passed on to an absent Other, becoming a method for relinquishing the anxieties that bareback pornography engendered but which were, ultimately, central to the erotic capital of the text. We use the term bequest here to acknowledge the contrast to the active dimension of the erotic endowment. A bequest is bequeathed it is given to someone, and is an act of giving, rather than receiving. A bequest is

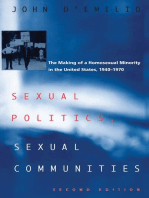

Figure 1. The endowmentbequest legacy of bareback pornography.

538

Sexualities 16(5/6)

bequeathed whether we like it or not. While not wishing to set up a simplistic passive/active dichotomy here, the bequest nevertheless acknowledges the fact that the problems of bareback pornography, (as perceived by our respondents) are not actively sought out or wanted. The anxieties that bareback pornography created for our respondents were unpleasant they wanted no involvement with them. As such, they bequeathed this inauspicious element of the bareback gift on to Others who were not present (and thus who had no opportunity to refuse this bequest). To summarise, when faced with ambivalent and contradictory feelings towards bareback pornography, respondents chose to operationalise a splitting up of the text. In doing so, they parsed their various reactions and responses to such material into two dierent categories in order to avoid or overcome the contradictions and paradoxes that bareback material presented to them. This act of parsing lies at the centre of our endowmentbequest dichotomy. The endowmentbequest dichotomy helps to explain the type of complex splitting that went on during group discussions, such as in the following, extended excerpt:

Respondent 1: The thing is with porn I think you get to . . . you get to look at bare back from a place where youre safe from like . . . from . . . there . . . theres no danger whether youre watching porn or not, you know from catching any STDs or anything from watching it. Erm, so yeah, I think theres . . . theres a big dierence between real life and porn. Respondent 2: No, [respondent] said it quite well actually I guess, that you cant just put . . . Id like to think that were more intelligent than that. Interviewer: Right. Respondent 2: And watch . . . we watch pornography and then do what they will do on screen. Id . . . Id like to think that it is just fantasy and thats as far as itd go. Respondent 1: Then again I think its one thing being like, oh; I want to watch a porn where theres group sex like its a harder thing to achieve and bare back is just not wearing a condom, so its, you can achieve that fantasy really easily as opposed to all of a sudden having these men of dierent ages and ethnicities surrounding you, so. Interviewer: Oh right, yeah, yeah, okay, ne. Yeah, any other thoughts? Respondent 1: But . . . sorry . . . But also what we were saying earlier about just missing out on porn being a big part of like our sexual erm, production I guess. I . . . I do worry about the next generation coming up watching pornography because I think it . . . it could have a eect on their attitudes towards sex and their appetites as well. But then I totally disagree that video games are really damaging to children and things like that as well, so.

Mowlabocus et al.

539

Interviewer: Okay, right, Ive got like a really complicated picture in my head here. Respondent 1: Yeah, its really contradictory, so. (1825 HIV Negative cohort 2)

The endowmentbequest paradigm provides a means of understanding the complex set of contradictions expressed by respondents across the focus groups. For older participants, bareback pornography was understood as both a representation of that which they had lost (the endowment) harkening back to the pre-AIDS period of their sex lives when real sex was raw sex, and a dangerous new trend that might be putting the next generation in harms way (the bequest). Meanwhile for some (but by no means all) HIV positive respondents, bareback pornography illustrated the type of sex they felt they could now legitimately have with other HIV positive men (the endowment), and simultaneously, represented something that might pose challenges to those who were seeking to remain HIV negative (the bequest). Through such splitting up of the bareback gift, respondents were able to entertain the prospect that bareback pornography might be having an eect on gay mens sexual behaviour without having to relinquish their enjoyment of it. Viewing bareback pornography through this dual lens allows us to recognise the positive investments in bareback pornography that individual gay men are making, as well as the anxieties and concerns that these investments raise. This is not to suggest that bareback pornography was seen to have a direct eect on gay mens sexual practice. Only one participant felt that there was a strong correlation between the representation of UAI in pornography and the subsequent practice of UAI among gay men. Far more prevalent was the view that bareback pornography was a potential concern for health promotion and that it may pose challenges in terms of safer sex strategies for some gay men.

Conclusion: Important, but not necessarily interesting

. . . people will watch bareback because although they might say that they are interested in safe sex, in reality they are not. (4055 HIV Positive cohort 2)

The foregoing quotation articulates the challenge that gay mens health promotion currently faces a challenge that is materialised in bareback pornography and upon which it trades. Sexual health remains a priority for many gay men and remaining HIV negative is still hegemonically desirable within gay male subculture. In stating that in reality gay men arent interested in safe sex, the statement that opens this section should not be read as contradicting this assertion. Indeed, this quotation comes from a discussion in which HIV positive participants identied very large dierences in attitudes towards UAI between HIV negative and HIV positive men they knew, where the former were perceived to be wanting to remain HIV negative. Instead, this statement should be understood as articulating the complex sexual realities that gay men occupy today. Safe sex continues to be

540

Sexualities 16(5/6)

understood as important by many, and recent research shows a high level of knowledge regarding HIV prevention among MSM in the region (Sigma Research, 2011), from which the participants were recruited. But being important isnt the same as being interesting. The presence of the endowmentbequest dichotomy across all focus group cohorts starkly illustrates the fact that, in gay male subculture today, using condoms during sex continues to be regarded as important, but watching bareback pornography is what is interesting. Or, to put this another way, the desires articulated through bareback pornography do not necessarily displace or otherwise erase the knowledge of safer sex that gay men have, and which they prioritise when having sex. Our research identies both an anxiety over the perceived eect that bareback pornography might be having on the gay male community, and an erotic investment in the source of those anxieties, namely representations of risky sex. Meanwhile, the very denition of what constitutes bareback sex in pornography requires further elucidation. Understanding how these investments and anxieties are dealt with by gay men, while seeking to recognise the validity of these at an individual and community level, is paramount if health promotion strategies are to be eective in supporting both long-term condom use and the validation of sexual desires that run counter to the rhetoric of safer sex. It is interesting to note that at no point did any respondent suggest that bareback pornography should be censored or criminalised. Given the level of investment that many respondents displayed in such material this is perhaps unsurprising. However, this does not mean that interviewees saw bareback porn as something that was here to stay. Many felt that it was of its time, while others felt it was already beginning to lose its erotic potential and was on the wane. While data from free and amateur sites would suggest otherwise, these two responses are perhaps most useful when considered not as fact-based statements but as expressions of a general sentiment towards the representation of UAI. Bareback pornography in terms of its style, its specic range of sexual practices and its erotic capital has arisen at a specic time in the history of gay male subculture, and speaks to desires that have, by and large, been marginalised by 30 years of highly eective and well-targeted sexual health promotion strategies. For many of the men interviewed talking about the erotic appeal of bareback pornography was not as dicult as conveying and identifying with the anxieties that such enjoyment inevitably engendered. This diculty in articulating these anxieties may be an unintended by-product of successful health promotion work. The authors here identify the need for such anxieties to be explored in more detail by health promotion professionals, and for such investments in bareback representations to be acknowledged and validated as legitimate no matter how challenging these investments might be. Writing of the tense and often fragile political aliations made between gay men and other oppressed minorities Bersani writes that:

The cultural constraints under which we operate include not only visible political structures but also the fantasmatic processes by which we eroticize the real. Even if

Mowlabocus et al.

541

we are straight or gay at birth, we still have to learn to desire particular men or women, and not to desire others; the economy of our sexual drives is a cultural achievement. (Bersani, 1995: 64)

Following Bersanis line of critique, Kippax and Smith sum up the position that gay male culture nds itself in one that also speaks to the problem of bareback pornography:

It is unlikely that political reection upon sexual practice is in itself sucient to cause an alignment between politics and desire: sexual liberation does not automatically follow the identication of objectionable politics. (Kippax and Smith, 2001: 424)

Bareback pornography might be most usefully conceptualised as a fantasmatic process through which the constraints that HIV/AIDS has imposed (via successful health promotion) upon gay male culture have become eroticised. This is not to place any blame on health promotion for investing in the rhetoric of the condom code. Instead, we conclude this article by calling for a recognition of bareback pornography as both a fantasy of unsheathed sexual desire and an expression of the very real desires and concerns that gay men nd themselves grappling with in this post-AIDS environment of ongoing prophylactic use. Funding statement

This article was created from the work undertaken by the Porn Laid Bare (PLB) project as a joint venture between the Terrence Higgins Trust, Brightons Informed Passions project and the University of Sussex. The Informed Passions project, which seeks to better support the sexual health needs of men who have sex with men within Brighton and Hove, is funded by the Big Lottery Funds Reaching Communities programme. As such, PLB is funded entirely by the grant from the Big Lottery Fund awarded to the Informed Passions project. It does not receive funding from the Terrence Higgins Trust.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the anonymous reviewers of this article for their constructive feedback, and also Ford Hickson (Sigma) and members of the Terrence Higgins Trust for their support and feedback.

Notes

1. The authors direct readers to the Adult Industry Medical Healthcare Foundation (n.d.) http://aim.altpixel.com/ for further information. 2. According to Ford Hickson of Sigma Research, this dissipating was in no small part due to the successes of gay mens health promotion whereby the limits of the British obscenity laws were tested through the use of images of penetration and anal intercourse in safer sex campaigns (Hickson, 2012 in conversation).

542

Sexualities 16(5/6)

3. The research objectives of this project, twinned with resource constraints meant that the authors were unable to engage with the issue of bareback porn production. As such, this article focuses on the consumption of said material. Further work is urgently needed regarding the production side of this industry, but is, sadly beyond the scope of this project. 4. PSE Public Sex Environment. 5. Indeed, the authors of this article are by no means unwilling to criticise gay male pornography and gay male subculture for its overinvestment in specific body types and its taxonomies of race, class and gender performance. See Mowlabocus (2010) for further discussion. 6. And even when pornography is used only for solo masturbation, the ways in which it is used, the contexts of use and the various modes of stimulation and enjoyment suggest that watching pornography to jerk off to is a complex affair. The researchers acknowledge this complexity while also recognising that an investigation into the role of pornography in masturbation (and vice versa) is beyond the scope of this current study. 7. Recreational drug use being a far more likely cause in the eyes of many participants. 8. See Gauntlett et al. (1998) for a complete discussion. 9. These risks include the real risk to the performer (of HIV infection), a potential risk to the consumer (of being influenced by the text) and also a moral risk (namely the risk of enjoying something which is considered morally wrong). 10. Carrier (2005) offers an insightful overview of Mausss work in this area, together with a concise history regarding the fashionability of his work in anthropology over the last 80 years. 11. The spirit of the gift that must be returned to the donor via a reciprocal offering. 12. The notion of the gift is, of course, not uncommon within bareback subculture, and some of the most powerful critiques of UAI and its attendant representations have centred on the idea of gift-giving. The conceptualising of HIV as a gift was popularised by the 2001 documentary of the same name (dir. L Hogarth), which sought to highlight the rise of bug-chasing in the USA. Since its release, opinions as to the prevalence of bug-chasing and gift-giving within gay male subculture have been varied. In bareback parlance, gift-giving is understood as seeking to intentionally infect someone with HIV its counterpart being bug-chasing, the act of intentionally seeking out HIV infection. While arguments regarding the veracity of these two practices continue to take up column inches in the popular press, the authors note with concern the fact that, in focusing on such practices and identities, much commentary on barebacking serves to unhelpfully polarise debates around bareback pornography. In doing so it obscures several important facts: that bareback pornography is popular within the mainstream of gay male culture, not just amongst the barebacking scene; that bareback pornography rarely (if ever) identifies itself using the terminology of gifts and bugs; and that watching bareback pornography rarely (if ever) articulates a desire either to seroconvert, or seroconvert others. 13. Although pornography can of course be given as a gift and gift economies around pornography do exist see the work of Slater (1998) for instance. 14. See forthcoming article by Mowlabocus, Harbottle and Witzel for further discussion of how bareback pornography and its representation of risk fits into a broader erotising of sexual and social risks and taboos within gay male pornography.

Mowlabocus et al.

543

15. For instance pornography that eroticises anonymous sexual encounters in public spaces, or which fetishises power disparities, particularly when those disparities are organised according to racial or age-based differences between performers. 16. In choosing these two terms endowment and bequest the authors acknowledge the respondents many references to bareback pornography being a form of cultural legacy. Older and younger respondents identified generational shifts in pornographic consumption and in understandings and attitudes towards HIV/AIDS and sex without a condom. By employing these two terms then, we seek to recognise both the handing down of gay subculture and the transformations and translations that occur in the process of such cultural movement.

References

Adult Industry Medical Healthcare Foundation (n.d.) Available at: http://aim.altpixel.com/ (accessed 19 June 2013). Attwood F (2007) No money shot? Commerce, pornography and new sex taste cultures. Sexualities 10(4): 441456. Attwood F (ed.) (2009) Porn.com: Making Sense of Online Pornography. New York: Peter Lang. Ayres T (1999) China doll The experience of being a gay Chinese Australian. Journal of Homosexuality 36(3): 8797. Bersani L (1995) Homos. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. Bishop MJ (2007) The making of pre-pubescent porn star: Contemporary fashion for elementary school girls. In: Hall AC and Bishop MJ (eds) Pop Porn: Pornography in American Culture. Westport, CT: Praeger, pp. 4556. Burger JR (1995) One Handed-Handed Histories: The Eroto-Politics of Gay Male Video Pornography. New York: Harrington Park Press. Carrier JG (2005) A Handbook of Economic Anthropology. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing. Davis N, Hart G, Bolding G, et al. (2006) Sex and the internet: Gay men, risk reduction and serostatus. Culture, Health & Sexuality 8(2): 161174. Davison WP (1983) The third-person effect in communication. Public Opinion Quarterly 47(1): 115. Dean T (2009) Unlimited Intimacy: Reflections on The Subculture of Barebacking. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. Du Gay P (1997) Doing Cultural Studies: The Story of the Sony Walkman. London: SAGE. Dyer R (1985) Male gay porn: Coming to terms. Jumpcut: A Review of Contemporary Media 30: 2729. Escoffier J (2003) Gay for pay: Straight men and the making of gay pornogaphy. Qualitative Sociology 26(4): 531555. Escoffier J (2009) Bigger Than Life: The History of Gay Porn Cinema From Beefcake to Hardcore. London: Running Press. Fung R (1991) Looking for my penis: The eroticized Asian in gay video porn. In: Bad Object-Choices (ed.) How Do I Look? Queer Film and Video. Seattle, WA: Bay Press, pp. 145168. Gauntlett D (1998) Ten things wrong with the effects model. In: Dickinson R, Harindranath O (eds) Approaches to Audiences. London: Arnold, pp. 120130. R and Linne

544

Sexualities 16(5/6)

Gendin S (1997) Riding bareback: Skin-on-skin sex: Been there, done that, want more. Poz Magazine Online. Available at: www.poz.com/pozgibin/page?pHOME&fcontent&a24/myturn&x1 (accessed 12 January 2013). Glaser B (1992) Basics of Grounded Theory Analysis. Mill Valley, CA: Sociology Press. Goodroad BK, Kirksey KM and Butensky E (2000) Bareback sex and gay men: An HIV prevention failure. Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care 11(6): 2936. Gross L (2002) Up from Invisibility: Lesbians, Gay Men and the Media in America. New York: Columbia University Press. Gunther AC (1995) Overrating the X-rating: The third-person perception and support for censorship of pornography. Journal of Communication 45(1): 2738. Hall S (1973) Encoding Decoding in the Television Discourse. Birmingham: CCCS. Hall-Carpenter Archives (1989) Walking After Midnight: Gay Mens Life Stories (HallCarpenter Archives and Gay Mens Oral History Group). London: Routledge. Hansard (2010) Hansard online 1 December. Available at: http://www.publications.parlia ment.uk/pa/cm201011/cmhansrd/cm101201/halltext/101201h0002.htm (accessed 17 February 2012). Hoffner C and Buchanan M (2002) Parents responses to television violence: The thirdperson perception, parental mediation and support for censorship. Media Psychology 4(3): 231252. Hogarth L (dir.) (2001) The Gift. Dream Out Loud Films. Jacobs K (2004) Pornography in small places and other spaces. Journal of Cultural Studies 18(1): 6783. Jensen JD and Hurley RJ (2005) Third-person effects and the environment: Social distance, social desirability, and presumed behavior. Journal of Communication 55(2): 242256. Jensen R (2007) Getting Off: Pornography and the End of Masculinity. Cambridge, MA: South End Press. Kendall CN (2004) Educating gay male youth: Since when is pornography a path towards self-respect? Journal of Homosexuality 47(34): 83128. Kendall CN (2005) Gay Male Pornography: An Issue of Sex Discrimination. Vancouver: UBC Press. Kendrick W (1987) The Secret Museum: Pornography in Modern Culture. New York: Viking. Kippax S and Smith G (2001) Anal intercourse and power in sex between men. Sexualities 4(4): 413434. Kitzinger J (1994) The methodology of focus groups: the Importance of interaction between research participants. Sociology of Health 16(1): 103121. Lane FS (2000) Obscene Profits: The Entrepreneurs of Pornography in the Cyber Age. New York: Routledge. Lo VH and Paddon A (2001) Third-person effect, gender differences, pornography exposure and support for restriction of pornography. Asian Journal of Communication 11(1): 120142. Lo VH and Wei R (2002) Third-person effect, gender and pornography on the internet. Journal of Broadcasting and Electronic Media 46(1): 1333. Macnair B (1996) Mediated Sex: Pornography and Postmodern Culture. London: Arnold. Mauss M (1925 [2002]) The Gift: The Form and Reason for Exchange in Archaic Societies (trans. I Cunnison). London: Routledge.

Mowlabocus et al.

545

McLeod DM, Eveland WP and Nathanson AI (1997) Support for censorship of violent and misogynic rap lyrics: An analysis of the third-person effect. Communication Research 24(2): 153174. Medhurst A (1998) Tracing desires: Sexuality in media texts. In: Briggs A and Cobley P (eds) The Media: A Critical Introduction. Harlow: Pearson Education, pp. 283294. Mercer J (2004) In the slammer: The myth of the prison in gay american pornographic video. In: Morrison TG (ed.) Eclectic Views on Gay Male Pornography: Pornucopia. New York: Harrington Park Press, pp. 151166. Mercer K (1991) Skin head sex thing: Racial difference and the homoerotic imaginary. In: Bad Object-Choices (ed.) How Do I Look? Queer Film and Video. Seattle, WA: Bay Press, pp. 169222. Mercer K (1992) Just looking for trouble: Robert Mapplethorpe and fantasies. In: Segal L and McIntosh M (eds) Sex Exposed: Sexuality and the Pornography Debate. London: Virago, pp. 92110. Morrison TG (2004a) He was treating me like trash, and I was loving it . . . Perspectives on gay male pornography. Journal of Homosexuality 47(34): 167183. Morrison TG (ed.) (2004b) Eclectic Views on Gay Male Pornography: Pornucopia. New York: Harrington Park Press. Mowlabocus S (2010) Gaydar Culture: Gay Men, Technology and Embodiment in the Digital Age. Farnham: Ashgate. Mowlabocus S, Harbottle J and Witzel C (forthcoming) What we cant see? Understanding the representations and meanings of UAI, barebacking and semen exchange in gay male pornography. (under review) Journal of Homosexuality. Paasonen S, Nikunen K and Saarenmaa L (2007) Pornified: Sex and Sexuality in Media Culture. New York: Berg. Patton C (1991) Safe sex and the pornographic vernacular in bad object choices (ed.) How Do I Look? Queer Film and Video. Seattle, WA: Bay Press, pp. 3150. Patton C (1996) Fatal Advice: How Safe Sex Education Went Wrong. Durham, NC: Duke University Press. Porter K and Weeks J (eds) (1991) Between The Acts: Lives of Homosexual Men, 18851976. London: Routledge. Powell RA and Single HM (1996) Focus groups. International Journal of Quality in Health Care 8(5): 499504. Radel N (2001) The transnational ga(y)ze: Constructing the East European object of desire in gay film and pornography after the fall of the wall. Cinema Journal 40(1): 4062. Raheja GG (1988) The Poison in the Gift: Ritual, Prestation and the Dominant Caste in a North Indian Village. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. Rofes E (1998) Dry Bones Breathe: Gay Men Creating Post-AIDS Identities and Cultures. New York: Harrington Park Press. Rojas H, Shah DV and Faber RJ (1996) For the good of others: Censorship and the thirdperson effect. International Journal of Public Opinion Research 8(2): 163186. Rotello G (1997) Sexual Ecology: AIDS and the Destiny of Gay Men. New York: Dutton. Sandstrom KL (1996) Redefining sex and intimacy: The sexual self-images, outlooks, and relationships of gay men living with HIV/AIDS. Symbolic Interaction 19(3): 241262. Scarce M (1999) A ride on the wild side. Poz Magazine. Available at: www.poz.com/articles/ february1999/inside/rideonthewildeside.html#safer (accessed 18 June 2011).

546

Sexualities 16(5/6)

Shin DH and Kim JK (2011) Alcohol product placements and the third-person effect. Television and New Media 12(5): 412440. Sigma Research (2011) The UK gay mens sex survey: South-east coast of England region of residence data report. Available at: http://www.sigmaresearch.org.uk/files/local/South_ East_Coast_2010.pdf (accessed 14 February 2012). Signorile M (1997) Life Outside: The Signorile Report on Gay Men: Sex, Drugs, Muscles, and the Passages of Life. New York: HarperCollins. Slater D (1998) Trading sex-pics on IRC: Embodiment and authenticity on the internet. Body and Society 4(4): 91117. Smith RD, Delpech VC, et al. (2010) HIV transmission and high rates of late diagnoses among adults aged 50 years and over. AIDS 24(13): 21092115. Stoltenberg J (1991) Gays and the pro-pornography movement: Having the hots for sex discrimination. In: Kimmel MS (ed.) Men Confront Pornography. New York: Meridian, pp. 248262. Strossen N (1995) Defending Pornography: Free Speech, Sex and the Fight For Womens Rights. New York: Scribner. Tewksbury R (2003) Bareback sex and the quest for HIV: Assessing the relationship in internet personal advertisements of men who have sex with men. Deviant Behavior 24(5): 467483. Watney S (1996) Policing Desire: Pornography, AIDS and the Media. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. Waugh T (1985) Mens pornography: Gay vs. straight. Jump Cut: A Review of Contemporary Media 30: 3035. Waugh T (1996) Hard to Imagine: Gay Male Eroticism in Photography and Film, from their Beginnings to Stonewall. New York: NY: Columbia University Press. White M (2003) Too close to see: men, women, and webcams. New Media and Society 5(1): 728. Williams L (1992) Pornography on/scene or diffrent strokes for diffrent folks. In: Segal L and McIntosh M (eds) Sex Exposed: Sexuality and the Pornography Debate. London: Virago, pp. 233265.

Sharif Mowlabocus is a Senior Lecturer in Digital Media at the University of Sussex. His research is situated at the intersection of digital media studies and LGBTQ studies and focuses on issues of identity, sexual practice and health as they are manifested in digital and mixed reality formats. He is a member of the Centre for Material Digital Culture and convenes Masters and Bachelors programmes in Digital Media and Culture. Justin Harbottle is the Programme Ocer for Quality and Engagement at the Terrence Higgins Trust. Justin has worked in the eld of HIV prevention for men who have sex with men for the last six years, and has specialised in providing sexual health promotion across a wide range of online platforms and engaging higher-risk populations. Previously completing a MA in Sexual Dissidence in Literature and Culture at Sussex University, Justins research interests included gay mens usage of online spaces and shifts in the representation of gay

Mowlabocus et al.

547

pornography, both of which proved central in his subsequent role at the Terrence Higgins Trust. Charlie Witzel has occupied a variety of posts at the Terrence Higgins Trust over the last four years, in both London and Brighton and in both health promotion and long-term condition management. Most recently Charlie has worked as coordinator of the Health, Wealth and Happiness project, an initiative that supports over 50s living with HIV. Charlie completed his BA in Anthropology and Development Studies at Sussex University in 2011 and is currently studying for a masters degree in Public Health at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine. Charlies research interests include minority sexual cultures, representations of illness and surveillance of disease.

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- Pornography and Sexual Deviance: A Report of the Legal and Behavioral Institute, Beverly Hills, CaliforniaD'EverandPornography and Sexual Deviance: A Report of the Legal and Behavioral Institute, Beverly Hills, CaliforniaPas encore d'évaluation

- Gender Politics: Citizenship, Activism and Sexual DiversityD'EverandGender Politics: Citizenship, Activism and Sexual DiversityPas encore d'évaluation

- Bishop 2014Document24 pagesBishop 2014Matheus SvóbodaPas encore d'évaluation

- What Do People Do With Porn Qualitative Research IDocument21 pagesWhat Do People Do With Porn Qualitative Research IAnonymous 0eAfcg8PPas encore d'évaluation

- Reflections On Ethical Problems Encountered in Field Research On Mexican Male Homosexuality: 1968 To PresentDocument16 pagesReflections On Ethical Problems Encountered in Field Research On Mexican Male Homosexuality: 1968 To PresentBiblioteca ColsonPas encore d'évaluation

- Porn Sex Versus Real Sex: How Sexually Explicit Material Shapes Our Understanding of Sexual Anatomy, Physiology, and BehaviourDocument23 pagesPorn Sex Versus Real Sex: How Sexually Explicit Material Shapes Our Understanding of Sexual Anatomy, Physiology, and Behaviourzyryll yowPas encore d'évaluation

- After The Paradigm Shift Contemporary PDocument20 pagesAfter The Paradigm Shift Contemporary PRodrigo AlcocerPas encore d'évaluation

- Beyond The Superordinate Categories of "Gay Men" and "Lesbian Women": Identification of Gay and Lesbian SubgroupsDocument27 pagesBeyond The Superordinate Categories of "Gay Men" and "Lesbian Women": Identification of Gay and Lesbian SubgroupsRobert Wynn IIIPas encore d'évaluation

- Understanding and Helping Individuals With Homosexual ProblemsDocument42 pagesUnderstanding and Helping Individuals With Homosexual ProblemsPizzaCowPas encore d'évaluation

- Sanders Sexualities PDFDocument21 pagesSanders Sexualities PDFjudahPas encore d'évaluation

- Langaritaadiego 2017Document15 pagesLangaritaadiego 2017arlourgellPas encore d'évaluation

- Lim JournalofHomosexuality2002Document21 pagesLim JournalofHomosexuality2002jeff verly JOSEPHPas encore d'évaluation

- Running Head: Evolutionary Theories On Male Homosexuality 1Document8 pagesRunning Head: Evolutionary Theories On Male Homosexuality 1Jasmin Jumonong CarumbaPas encore d'évaluation

- CHAPTER 3 Research MARIANO ESCRIN HUSBIEDocument24 pagesCHAPTER 3 Research MARIANO ESCRIN HUSBIEEdcel CardonaPas encore d'évaluation

- Evolutionary SexDocument20 pagesEvolutionary SexAndrés Pereyra RabanalPas encore d'évaluation

- Alphas, Betas, and Incels: Theorizing The Masculinities of The ManosphereDocument20 pagesAlphas, Betas, and Incels: Theorizing The Masculinities of The ManospherecalinPas encore d'évaluation

- Alphas, Betas, and Incels: Theorizing The Masculinities of The ManosphereDocument20 pagesAlphas, Betas, and Incels: Theorizing The Masculinities of The ManospherecalinPas encore d'évaluation

- Is Pedophilia A Mental DisorderDocument5 pagesIs Pedophilia A Mental DisorderPaulo FordheinzPas encore d'évaluation

- Introducing The Gay Gene' - Media and Scientific RepresentationsDocument17 pagesIntroducing The Gay Gene' - Media and Scientific RepresentationsAnonymous Kf4ZRHJJ0jPas encore d'évaluation

- ContentServer PDFDocument23 pagesContentServer PDFsasihPas encore d'évaluation

- Brown, C. C., Durtschi, J. A., Carroll, J. S., & Willoughby, B. J. (2017) PDFDocument8 pagesBrown, C. C., Durtschi, J. A., Carroll, J. S., & Willoughby, B. J. (2017) PDFFarahYumna PutriKamalPas encore d'évaluation

- Shor-Simchai Westermarck AJS 09Document41 pagesShor-Simchai Westermarck AJS 09gavinnurrafiq23Pas encore d'évaluation

- What's The Story? Exploring Online Narratives of Non-Binary Gender IdentitiesDocument29 pagesWhat's The Story? Exploring Online Narratives of Non-Binary Gender IdentitiesItsBird TvPas encore d'évaluation

- Research Paper About Gay LanguageDocument6 pagesResearch Paper About Gay Languagerflciivkg100% (1)

- Gender Differences in Receptivity To Sexual OffersDocument22 pagesGender Differences in Receptivity To Sexual OffersJonathan OrtizPas encore d'évaluation

- Survey of The Brony Subculture, First EditionDocument33 pagesSurvey of The Brony Subculture, First Editionopspe33% (3)

- Teaching Post-Pornography: Cultural Studies Review Vol. 24, No. 1 March 2018Document13 pagesTeaching Post-Pornography: Cultural Studies Review Vol. 24, No. 1 March 2018Thaís CavalcantiPas encore d'évaluation

- Research ProposalDocument8 pagesResearch ProposalWayne WebsterPas encore d'évaluation

- PornDocument38 pagesPorncarrier lopezPas encore d'évaluation

- Jurisprudence Project Edited 1Document17 pagesJurisprudence Project Edited 1Soumik PurkayasthaPas encore d'évaluation

- Gay Rights DissertationDocument5 pagesGay Rights DissertationHelpWritingPaperCanada100% (1)

- Hip Hop Club Scene - Gender Grinding Sex 2007Document15 pagesHip Hop Club Scene - Gender Grinding Sex 2007Laura Sales GutiérrezPas encore d'évaluation

- Coming inDocument30 pagesComing inapi-530420006Pas encore d'évaluation

- Post PrintDocument38 pagesPost PrintHugo RiosPas encore d'évaluation

- Adult Social Bonds and Use of Internet PornographyDocument14 pagesAdult Social Bonds and Use of Internet PornographytrochepPas encore d'évaluation

- Using Biographical Narrative and Life Story MethodDocument7 pagesUsing Biographical Narrative and Life Story MethodPISMPTESLL0622 Nurdalilah Atikah Binti JamaludinPas encore d'évaluation

- Transmuting Gender BinariesDocument15 pagesTransmuting Gender BinariesSergioPas encore d'évaluation

- What Are The Attitudes of The Public Towards Homosexuals?Document9 pagesWhat Are The Attitudes of The Public Towards Homosexuals?Zoe ChengPas encore d'évaluation

- 44Document12 pages44Rifat BeharPas encore d'évaluation

- Sexual Fantasy and Masturbation Among Asexual Individuals: The Canadian Journal of Human Sexuality August 2014Document9 pagesSexual Fantasy and Masturbation Among Asexual Individuals: The Canadian Journal of Human Sexuality August 2014SyaifudinPas encore d'évaluation

- MorrisonDocument29 pagesMorrisonHridaanPas encore d'évaluation

- Revisiting Social Acceptance of HomosexualityDocument18 pagesRevisiting Social Acceptance of HomosexualityAlthea EsperanzaPas encore d'évaluation