Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

POHP Special Section 11-30-03

Transféré par

prisonerofherpastCopyright

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

POHP Special Section 11-30-03

Transféré par

prisonerofherpastDroits d'auteur :

Sonia Reich sits in her room in a Northbrook nursing home.

At night, she refuses to put on pajamas or sleep in her bed, preferring instead to stay in her chair, as if ready to run at a moments notice.

Hunted by the Nazis 60 years ago, Sonia is running again

Story by Howard Reich

N THE FRIGID EVENING OF FEB. 15, 2001, a silver-haired woman who stood less than 5 feet tall packed some skirts, blouses and underwear into two brown shopping bags. She put on her gray winter coat, locked the door to her Skokie home and fled. After she wandered the dark and empty streets of the northern suburb for a couple of hours, the police picked her up and deposited her at a nearby relatives home. The next morning she was out the door and running again, only to be grabbed by the Skokie police once more.

Her psychotic visions revived a nightmarish past in which she, as an 11-yearold girl, escaped the Jewish ghetto in Dubno, Poland, as her family and friends were being shot by German death squads. Although no one knew it, she was suffering from a little-known mental illness that only recently had been diagnosed among aging Holocaust survivors. The womanmy mother, Sonia Reichhardly had spoken of the horrors she experienced, though

Someone was trying to kill her, to put a bullet in my head, the 69-year-old woman told anyone who would listen. But no one in the emergency room of Rush North Shore Medical Center, where the police brought her, nor in the hospitals locked-down psychiatric ward, where she was placed a few hours later, believed this claim, or any of the others she made. They couldnt imagine that someone had painted yellow Stars of David on her front lawn, or that the food she was being served in the hospital was covered with lice or that each night voices told her she was going to be killed and, therefore, she had to run. To her, these delusions were as real as life itself.

occasionally she had mentioned that, as a child, she was running and running, I didnt know where I was running. She described sleeping on the ground and working on farms for scraps of food. She was filthy and ridden with lice. She told my sister, Barbara, that she was in fields alone and people were shooting at me. But that was nearly all she revealed about this harrowing period of her life. Almost 60 years later, a widow who had led a stable postwar existenceraising a family and taking trips to California to visit her grandchildrensuddenly and inexplicably began re-enacting her past. When the police first brought my mother to the hospital, the emergency-room doctors gave her a full run of neurological exams, including brain scans, which showed no abnormalities. Her personal physicians could find no explanation for what was happening to her. Eventually, I learned what was wrong from several specialists I contacted around the world: My mother had lateonset post-traumatic stress disorder. PTSD did not enter the psychiatric lexicon until 1980, and the delayed form that my

PLEASE SEE FOLLOWING PAGE

Photos by Zbigniew Bzdak

An only child, Sonia was an orphan by wars end. A year after this 1946 photo was taken, she began a new life in the U.S.

CHICAGO TRIBUNE

S E C T I O N 19

S P E C I A L R E P O RT

S U N D AY

NOVEMBER 30, 2003

CONTINUED FROM PREVIOUS PAGE

Stars of David made and worn by Holocaust victims in Poland are in the collection at the Jewish Historical Institute and Museum in Warsaw.

To see someone like her, to be able to do nothing to help and then to wash your hands of it is very difficult. You feel helpless. You feel almost as helpless as she is.

Dr. David Rosenberg, a Highland Park psychiatrist who has been evaluating Holocaust survivors for more than 40 years

mother had remains unknown to many physicians. After spending decades coping with frightening memories, many late-onset patients finally begin losing the war against their pasts. Catastrophic events that they experienced long ago reinsert themselves into their lives, the strands of the past and the present becoming inextricably bound, with medicine virtually incapable of unraveling them. No one knows how many people have this form of the disorder, largely because some disappear into the nursing-home population or their symptoms are mistaken as Alzheimers disease or other agerelated mental illness. Your mother has late-onset PTSD with bells and whistles, said Dr. David Rosenberg, a Highland Park psychiatrist who has been evaluating Holocaust survivors for more than 40 years. Last year, he was hired by the German Consulate General in Chicago to assess whether my mother qualified for a small increase in the monthly reparations payments she had been receiving since the late 1960s. But money was not going to change her condition, so I decided not to pursue it. To see someone like her, to be able to do nothing to help and then to wash your hands of it is very difficult, Rosenberg said. You feel helpless. You feel almost as helpless as she is. There was nothing any doctor could do to pull my mother from a thicket of paranoia and delusion. She refused to talk to doctors or nurses. She said they were trying to poison her, which was why she would not take any of the powerful drugs that fight psychosis. She fervently denied, as many such patients do, that anything was wrong with her, focusing her energies on eluding the killers she believed were hunting her. The staff at Rush North Shore and at the Northbrook nursing home where my mother eventually transferred were forbidden by law to force medication upon her unless she posed an imminent threat to herself or to others. So every month or two, when she became overly agitated or tried to escape, they injected her with Haldol, which often is used to treat the symptoms of psychotic disorders. The drug slowed her physically for a day or two but did nothing to reduce her delusions. It takes months of regular treatment before patients can reach potentially therapeutic levels. Although years earlier my mother had signed a document giving me power of attorney in case of medical emergencieswhich ultimately allowed me to place her in the nursing homeI had no legal right to medicate her against her will. Just a few months after my mother had fled her Skokie home, we reached a dead end. During my visits to the nursing home, my mother routinely asked what was happening in the world. She wanted to know about stories on the TV news and how much I was paying for the loaves of challah and pumpernickel bread she always asked me to bring. Once I answered these questions, though, she complained about the swastikas she believed were engraved on the books I gave her and about the other patients she said were trying to kill her. She tried in vain to scrub imagined yellow Stars of David off her clothes and from the inside of the toilet bowl. She kept her fanny pack loaded with bread, toilet paper and other essentials. She refused to put on pajamas or to sleep in bed, preferring to doze fully dressed in a chair all night, every night, as if ready to run at a moments notice. Worse, she insisted that patients in the hallway of the nursing home beat her and spit on her, and that doctors and nurses were touching her private parts. She yelled at them, I am not a whore. What could I possibly say in response? Having spent my entire adult life as a reporter and music critic, I was accustomed to jotting down other peoples words. Out of habit, I began doing so again. Twice a week, when I visited my mother, I wrote down her assertions and asked her questions. When did she escape the Dubno ghetto? How did she survive as a child on her own? In which towns had she found shelter? She almost always refused to answer. Questioning my mother was as futile as everything else I had tried. Still, I was driven by the need to better understand the events behind her delusions. I needed to hear the stories she could not tell. I needed to piece together the narrative of her past, just as I had done hundreds of times in my work. Shortly after my mother moved to the nursing home in the spring of 2001, I opened her mail and found a letter from an aunt of hers, whom I barely knew. Irene Tannen, who was 79, had worried when no one answered the telephone in my mothers house and decided to write. I immediately phoned her and told her what had occurred. Then I arranged to visit her in New York to find out what she knew about my mothers past. She told me that they had lived together in the Dubno ghetto, that she had escaped before my mother and, therefore, only knew pieces of my mothers story. Ask Leon what happenedhe knows everything, Irene said, referring to her nephew, Leon Slominski, who had fled the Dubno ghetto as a child and, like my mother, somehow survived.

Sonia eats bread brought by her son, Howard. She stashes food and supplies in a bag she keeps at her side and often refuses to eat meals served in the nursing home because she believes they are covered with lice.

Secrets, ghosts of a familys life

othing about my parents lives in the United States was as routine or as ordinary as I might have wanted to believe. When my mother arrived here as a

16-year-old, in 1947, she faced a second struggle to survive, toiling in factories to afford one room in a Chicago boarding house. She went to night school to learn English and used to say that when she married Robert Reich, a concentration camp survivor, she had no money, only a couple of hundred dollars in debts. Her choice of my father as a husband seemed fitting, not only because of their shared history but because of the protection he afforded her. Nearly 10 years older, athletic and socially ebullient, he exuded remarkable optimism, considering that he had suffered the loss of both of his parents and several siblings as the Holocaust swept through Sosnowiec, Poland. Though my father spared his children the details, an affidavit he signed on March 12, 1957, for the German government, which I discovered among his papers while researching my mothers past, sketched out his war experiences. German soldiers took possession of his fathers bakery in September 1939, forcing my father to work for them as a baker. In February 1942, at age 20, he was taken to the Markstadt Work Camp in western Poland. For 12 hours a day he hauled heavy asbestos plates, used for roofing, at a factory near the camp. For these labors, he was fed bread or soup once a day. A year later, he was sent to the Funfteichen Concentration Camp nearby, where he loaded sand into dump cars and built railroad beds. Even at night we were given no rest, he said in the affidavit. We would sometimes be awakened and forced to march for miles, or had to submit to beatings and other types of cruelty. By January of 1945, as the Soviet army approached from the east, the Schutzstaffel (SS), Adolf Hitlers elite guard, forced 6,000 Jewish prisoners to walk from Funfteichen toward Buchenwald, a death march that 200 people survived, including my father. At Buchenwald, my father was assigned to throw dead bodies onto wagons. By then, he was sick with typhoid but did not say so, presuming he would be burned to death if he did. On April 11, 1945, he was liberated from Buchenwald by American soldiers and spent the next several months recovering in a hospital in Wiesbaden, Germany. My father used to say that as a child he dreamed of becoming a musician or an artist. I still own the Hohner accordion he bought in Wiesbaden, and the oil paintings he created while recuperating from Buchenwald hang in my living room. But after the

About the author

Howard Reich, 49, has been a Tribune arts critic and reporter for 20 years. He is the author of two books and has been writing about music in Chicago since 1976.

About the photographer

Zbigniew Bzdak, 48, was born and educated in Poland. He left the country in 1979 and has taken photos all over the world, including the Amazon, which he has documented for the last decade. He joined the Tribune in September 2002.

On the Web

For photo galleries, video and other information on Prisoner of Her Past, go to www.chicago tribune.com/sonia

war he worked as a baker, the only trade he knew. He came to the United States on May 18, 1949, arriving in Boston, then he traveled to Chicago, where a few surviving relatives had settled. A mutual friend introduced him to my mother, and they married in 1953. Within a couple of years, my father was co-owner of a bakery on the North Side. As a child, I saw him mixing vats of dough back near the ovens, while my mother served the customers and rang up the cash register in front. After years of getting by in small apartments, they saved up enough money to buy a two-bedroom, one-bath home in an extraordinary place: Skokie. Like a Jewish shtetl transplanted to America, Skokie, once a small bedroom community, was transformed after World War II by Holocaust survivors who built synagogues, Hebrew schools, delis, Jewish community centers and other throwbacks to life in the old country. On High Holy Days, when Jewish families like ours flocked to temple, the public schools were half empty. It was precisely because of the towns identity as an enclave of Holocaust survivors that a neo-Nazi group infamously sought to march through the village in the late 1970s, igniting an international media frenzy and causing anguish to the locals. In the weeks leading up to the 1978 march, which eventually was detoured to Marquette Park, my father paced agitatedly around our one-story, yellowbrick house, railing on the phone to relatives and friends about the neo-Nazis. My mother said little, confining herself to our small kitchen, where she constantly cooked food and scrubbed dishes. My father didnt talk about his wartime experiences, but he did tell us about dreams in which he machine-gunned Nazis. My mother barely seemed to sleep at all. Often, when I woke up in the middle of the night or came home late, I saw her sitting on the floor of the carpeted living room, alongside the low-slung picture window as she peered through the frill at the bottom of the shade. Night after night she sat there, staring through glass for hours on end, watching the occasional car cruise by in the dark. Yet by the time I awoke in the morning, she was always at the kitchen table, sipping black coffee, preparing brown-bag lunches, cooking, cleaning, her usual routine. Actions that seemed unremarkable or a bit eccentric now carry other meanings, hinting at an illness that eventually would reveal itself. But how was a child to know? Didnt other mothers check the chain lock on the inside of the door five or 10 times before being convinced that it was securely fastened? Didnt other moms ask, with alarm, what was wrong whenever someone went to the bathroom in the middle of the night? One night, when I was a teenager, I came home an hour late from the public library to find a squad car parked in front of the house. My mother had called the Skokie police. This was the tragicomic nature of growing up with survivors in Skokie, where adults with bluish numbers tattooed on their forearms were practically everywhere, and the spectacle of relatives yelling about Nazis past and present, real and imagined, seemed almost mundane. But, of course, it was not. The way my father and aunts and unclesall Holocaust survivorsranted and raved at family gath-

NOVEMBER 30, 2003

S U N D AY

S P E C I A L R E P O RT

S E C T I O N 19

CHICAGO TRIBUNE

Panienska Street, shown in a 1930s photo from the Dubno archive, was the most exclusive street in what was one of the oldest Jewish cities in Poland. Before World War II, 12,000 Jews lived in Dubno. By the end of the war, nearly all of the Jewish population in Sonias hometown had been executed.

Sonia (then Bluma Sys) and her childhood playmate, cousin Leon Slominski (Leib Shapiro), pose with their grandfather, family patriarch Schlomo Sys, in Dubno in the late 1930s.

erings became, to me, a kind of din. They decried the perpetual tensions in the Middle East; they saw anti-Semitism practically everywhere; they feuded with each other constantly. I tried to tune it out, eventually finding escape in music. Spending hours every day practicing the piano blocked out the noise and displaced the anger of an extended family that understandably never had overcome its rage. But as I played Bach and Ravel on the Steinway grand that dwarfed our living room, my mother worked in the kitchen in silence. The wall separating the two rooms crisply defined the two distinct worlds in which my mother and I lived. I did not spend much time wondering why my mother had no friends of her own, outside of my fathers, and why she had scant contact with her few surviving relatives. Nor did I recognize that when my parents made their first, and only, return to Poland since the Holocaust, in 1985, my father retraced his past, while my mother mysteriously declined to re-examine hers. Though my parents were staying in Warsaw, where her cousin Leon had lived since the end of the war, my mother did not call or see him. Nor did she travel to Dubno, now in Ukraine, to find out if her family home was still standing or to search for fragments of a destroyed childhood. My mother lived comfortably in the protection of my father. But his death in 1991, at age 69, changed everything. At first, she appeared to be coping, going about the business of keeping her home immaculate, but over the next decade she began to retreat more deeply into it, emerging only to buy groceries or for the occasional doctors appointment. A few months before she fled the house, my mother had begun acting in peculiar ways that my sister and I could not ignore. When making a rare foray with me to the bank, for instance, she insisted upon bringing a gallon of water, although at 98 pounds she barely could handle the outsize plastic jug. She needed this water, she said, but she wouldnt say why. She also told relatives, I later learned, that large, yellow Stars of David had been painted on the lawn of her Skokie home. But it wasnt until my mothers two long stays in the psychiatric ward of Rush North Shore Medical Center, in the spring of 2001, that the nature and depth of her problems started to form a discernible pattern. Practically every delusion carried an echo of her past. Some people here call me a dirty Jew, she said of the other patients. They say I can only sit at the table with the other dirty Jews. The doctors discharged her from the hospital with the generic diagnosis of delusional disorder and ordered that she be kept in a secure environment. But as the hospital staff prepared for her departure, she began scurrying up and down the hallways to elude the orderlies. They want to take me to Wisconsin to work on a farm, she shouted. She also claimed that her three grandchildren had been taken away and that when the other patients played bingo, the winner gets to kill me. Yet she was fully aware of what year it was, that my wife and I were journalists, her daughter a

Some people here call me a dirty Jew. They say I can only sit at the table with the other dirty Jews.

Sonia Reich, during her stay at a pyschiatric ward in 2001

In her room at the nursing home, Sonia enjoys perusing a family scrapbook, which includes a photograph from Feb. 19, 1956, of her and her husband, Robert, at a relatives wedding in Chicago.

homemaker, her son-in-law an accountant. She learned the names of every nurse, doctor, maid and patient on her floor in the nursing home. She kept herself as clean and well-dressed as ever. My mother was trapped, the doctors said, in a strange confluence of bitter memory, visceral fear and the routines of everyday existence. This happened because, as a child, she was thrust into a bizarrely hostile world, wrote Dr. Rosenberg in his evaluation for the German government. She became a hunted animal, a jungle child, who barely survived by the use of running, hiding and begging. Her efforts to survive during the persecution were served by hypervigilance, and by aloofness, and both of these defenses have reappeared in the last few years, but now in psychotic form and intensity. My mother was not alone in her anguish. Now that the child survivors are becoming old, were finding that their problems are worse than the adults faced, I was told by Dr. Henry Krystal, a pioneer in establishing the diagnosis of traumatic stress disorder and a concentration-camp survivor himself. Every visit to the nursing home depressed me more than the last. Sometimes my mother raged at me for not getting her out of there. Sometimes she urged me to sleep in her bed, while she promised to watch over me. During my mothers stay in the nursing home, I managed to pry from her a few precious details of her past. She told me that the room in which the family lived in the Dubno ghetto had no door, only a window through which everyone climbed in and out. She said that a German soldier once threatened to shoot her. By researching books and documents, including the transcripts of the Nuremberg trials, I learned that at least one massacre took place in Dubno. But if I wanted to know anything moreand I fervently didI needed to look elsewhere.

PLEASE SEE FOLLOWING PAGE

CHICAGO TRIBUNE

S E C T I O N 19

S P E C I A L R E P O RT

S U N D AY

NOVEMBER 30, 2003

NOVEMBER 30, 2003

S U N D AY

S P E C I A L R E P O RT

S E C T I O N 19

CHICAGO TRIBUNE

Taking a plunge into the past

never had heard of Leon Slominski, my mothers cousin in Warsaw. Like practically everything else about my mothers past, he was not discussed. But Irene Tannen, my mothers aunt, said

that Leon and my mother were playmates before their youth was interrupted.

I promised myself I never will be without a gun again. I will never be killed like a sitting duck.

Leon Slominski, who enrolled in military school immediately after the war ended

Their closeness is unmistakable in an old family photograph that surfaced when I was cleaning out my mothers Skokie home. In the black-and-white, 1930s shot, Leon and Sonia, then called Leib Shapiro and Bluma Sys, appear in crisply pressed clothes for a formal portrait, embraced by their grandfather, Schlomo Sys. When I arrived at Warsaws Okecie Airport in August, Leon threw his arms around me. He looked impeccable, his slender build, neatly combed hair and perfectly pressed suit pointing to a man in complete control of his appearance. He spoke softly in measured phrases in the manner of a lifelong researcher and scientist who spent most of his career in the military. Leon took my luggage, loaded it into his car, and insisted that we plunge immediately into the past, jet lag or not. He drove to a small Holocaust memorial at the site of the destroyed train station where Jews from the nearby Warsaw ghetto were shipped to their deaths in concentration camps. A few dozen first names commonly used by Jews at the time were carved into the compact stone memorial to represent everyone. Leon pointed to Bluma, my mothers original name. Then he pushed ahead to Warsaws old Jewish cemetery to visit the grave of his sister, Fanka, who hid with him during the Holocaust, the two children often holding hands as they ran to escape gunfire around them. His face began to crumple as we arrived at Fankas tomb, its marble facade listing everyone in the family not seen since they were last together in the Dubno ghetto. Under the surname Sysfor Schlomo Sys, the family patriarchmore than a dozen names of those executed had been carved into stone. After dusting off the marble with a handkerchief, Leon started speaking about the war. He recalled little of life in the ghetto, but his story about being on the run from the Nazis took two days to tell. Early one morning in 42, we passed through the gate of the ghetto, said Leon, 68, speaking excellent English. Probably father had paid a bribe to get us out, the parents and their two children leaving together. A wagon with horses was waiting, with a Ukrainian man who was taking us away, Leon continued. We went by this wagon to a village called Budki, where we stayed with a very poor Polish family. I remember the name of them, Wieczorek. But then our parents sent Fanka to a village called Malinowka, and me to a place not far from Budki called Nowy Swiat, to the farmer called Dabrowski. Probably our parents decided that one child will be there, the other here, and we will blend in. What I remember, of course, was crying at night, Where is my mother? In the village they tried to teach me Catholic praying, just so they could say that I am not a Jew. Leons parents remained in Budki, but after a couple of months they reclaimed both children. By the spring of 1943, they all were hiding on the Dabrowski farm, the owners having fled themselves, for fear of being massacred by Ukrainian nationalists who were attacking Poles, Leon said. With the Dabrowskis gone, 7-year-old Leon, 8-yearold Fanka and their parents hid in a deep ditch in a barn, four people standing upright in nearly total blackness through most of the day and night, for weeks on end. We had to lean against each other in the hole, but at least we could breathe, because the hole was covered with hay, Leon said. I remember my mother passed the days reciting to me a poem of Pushkins, in Russian. This poem was maybe 50 pages long, and she knew it by heart from the first letter to the last one, and she said it to me so many times that, until now, I can remember it. Without pause, Leon began reciting, in Russian, Aleksandr Pushkins epic poem The Tale of Tsar Saltan, its 894 lines recounting the plight of a family torn apart. Son and mother, safe and sound, the poem reads. Feel that theyre on solid ground. From their cask, though, who will take them? Surely God will not forsake them? Around Easter 1943, soldiers set the barn ablaze. We were still inside when the flames started, so father pushed the door open and jumped out, second was Fanka, I was third and mother was fourth, Leon said. Mother didnt get time to go out, so she burned up. I remember hearing her crying. The forest was 15 or 20 meters away, and we ran.

Sonias cousin Leon, 68, visits Warsaws old Jewish cemetery to see the grave of his sister, Fanka, who hid with him during the Holocaust. She suffered both mentally and physically until her death in 1995 at age 60 of kidney failure. Her nervous system was wounded, Leon said.

The soldiers were 100 meters from us, and they seemed a little bit disappointed that we escaped, so they shot at us, but we covered our heads. I see this picture like a photograph: The barn is in flames, soldiers in front of us, behind us the forest, and we are standing. I cannot forget this picture. The three escaped into the woods and eventually found a group of two dozen Jews in hiding. A few months later, the group was at a campfire when the afternoon stillness was shattered by another attack. As he recalled this moment, Leon reverted to Polish, the language of his childhood. It was very warm, the middle of the day, and we were all sitting, having something to eat, Leon said. Fanka was 100 meters away, in a tent or some kind of shelter, and I was with father. Then a small group of troopsfive or 10 men started shooting and screaming. And it took one minute, or less, and all the people disappeared, lying over here or over there. I remember, three or four of my known people killed in front of my eyes. I remember one man who got shot, and I was crying, Frolka, Frolka, what is wrong with you? I couldnt understand what happened to him. And in this moment I was feeling that behind me there is a soldier. So I started to run, in the dirt. He was heavy, not so fast as me, but he was crying, Stop, Jew! Stop, Jew! He was shooting at me. I remember this moment when I was running for my life, and with complete exhaustion I still was running. I fell in the dirt, from exhaustion, and one thought went through my mind: Why me? Why are they shooting me? Im a good boy. Leon and Fanka reunited in the forest a short while later but, in the confusion, they werent sure if their father was alive. The next day, the surviving adults returned to the scene of the massacre and found the fathers body, then informed the children that they were orphans. Leon and Fanka spent the rest of the war in hiding, like my mother. But Leon and Fanka had each other. They found shelter in a small Czech village called Ozirko, where an invalid farmer named Vladimir Loukotkawho had one eye, no fingers and one leg shorter than the othertook them in. Periodically, Loukotka put the children in steamer trunks to hide them when German or Ukrainian soldiers showed up. The children waited out the war with Loukotka. Leon never saw my mother again, but he presumed that her years in hiding were similar to his and Fankas. All he remembered of my mother was the carefree childhood they shared, as Leon, Fanka and my mother played together rambunctiously in Schlomo Sys home. We made so much commotion, recalled Leon, that grandfather always said, Put these children in separate rooms. They are too noisy together. Leon said that after the war, Fanka never fully recovered. Her nervous system was wounded. He told me that she cried hysterically at night and battled depression, drugs, failed personal relationships and other demons, until she died of kidney failure in 1995, at 60. Leon also was transformed by the war, but in a different way. He immediately enrolled in military school. I promised myself I never will be without a gun again, he said. I will never be killed like a sitting duck. As Leon told me this story over two days, his ramrod military posture began to slump and his walking tempo slowed. He was surprised, he said, that the mere retelling would trouble him as much as it did, so he asked for a couple of days away from his American visitor. Later, over dinner with his wife in their home in Warsaw, he explained that the Polish government attributed his heart disease, high blood pressure, nervous anxiety and other maladies to survivors syndrome and paid his medical bills because of it. He was sorry about my mothers decline. I wonder if it will happen to me, he said. Finally, he told me that he wouldnt be able to accompany me to Dubno as he had planned. Leon, who I hoped would know the whole story, knew only part of it. For the rest, I would have to go to the place my mother always called my little Dubno.

A dying city reveals its horror

paths. Wooden shacks, which looked as though they were built a century ago, seemed about to fall over. Women in babushkas prodded cows across fields. Dubno, since 1990 part of Ukraine, hardly recovered from WW II, when the Germans burned half of it to the ground. Buildings blown away by tank fire were now empty lots covered with garbage and dirt, and homes left standing still had working outhouses. The center of the city was practically empty, a few stragglers representing its only signs of life. Though barely a speck on the map today, Dubno once was revered as one of the oldest Jewish cities in Poland, with synagogues that dated to the late 1500s. By the 19th Century, the town was thick with Yiddish theaters, klezmer bands, Hebrew bookstores and religious schools. Eleven temples dotted the city, including the great synagogue in the center of town, its three-story height and blocklong width rendering it the citys most imposing building. Early in the 20th Century, Jews from outside Kiev, Minsk and points east resettled in Dubno and towns like it, where Jewish communities thrived and commerce flourished. By WW II, 12,000 Jews lived in Dubno, nearly half the towns population. One of these immigrants, Schlomo Sys, my greatgrandfather, arrived from a small village near Kiev and eventually acquired a large house on Dubnos most exclusive street, at Panienska 4. The building, which Sys bought with profits from a booming business selling hops used in making beer, occupied a spacious corner lot large enough to hold an additional, smaller brick building in back. Because my mothers parents had divorced early in her childhood, my mother and her mother lived under Sys roof. When I found the family house, it still looked impressive considering its surroundings, an old but sturdy edifice bordered by weeded, abandoned plots. Inside, the living room was not big, but it was comfortable, with large windows affording a full view of a once-scenic neighborhood. In this house, my mother was surrounded by comfort, affluence and an extended family that doted on her. From the old family photo, I knew that as a girl her hair was jet-black with neatly trimmed bangs. Based on the accounts of relatives, I knew that she had played in the park across the street and on sunny

s I traveled the narrow, two-lane roads backward in time. Horse-drawn wagons loaded with hay lumbered along bumpy dirt

on the way to Dubno, it felt like riding

buted his death to the stress of losing everything he had spent a lifetime building. On June 22, 1941, the Germans broke the pact and attacked the Soviet Union, reaching Dubno three days later. For nearly a week, 2,000 tanks from opposing armies battled for control of Dubno, because of its strategic position along the Ikva River, and of Rovno, the nearby county seat. The fighting was so close to Dubnos residential streets that locals felt the explosions shaking their homes, and some believed the world might be coming to a cataclysmic end. The Germans established a makeshift prison on an open parcel a few blocks from the Sys family home, and residents watched as Russian, Polish and other prisoners died of starvation. Responding to this mistreatment, Dubno citizens began sending their small children, including my mother, to the prison to try to sneak food to the inmates. My mother was caught. The German soldier grabbed me, my mother once told me, in one of the few incidents she revealed about her war experience. He told me that if I ever did it again he would put a bullet in my head.

From little Dubno to killing ground

The marble facade of Fankas tomb is engraved with the names of more than a dozen relatives not seen since they were together in the Dubno ghetto.

afternoons walked to the Ikva River, just beyond the back door of the family home. On summer weekends, her grandfather took the family to the river to teach the children how to swim. They threw pebbles into the water, watching the stones glance across the surface, my mothers aunt, Irene Tannen, had told me. But serenity ended on Sept. 17, 1939, as Soviet tanks rolled into the citys streets, less than three weeks after Germany had attacked Poland from the west. Germany and the USSR had struck a non-aggression pact that, in effect, divided Poland between them, and Dubno quickly was transformed. The Soviets immediately dismantled most Jewish institutions and nationalized all private property, taking from Sys ownership of his house and his hops business. He collapsed of a heart attack a few months later, in the spring of 1940, at age 56. His family attri-

I remember this moment when I was running for my life and one thought went through my mind: Why me? Why are they shooting me? Im a good boy.

Leon Slominski

archive, I pulled out a typewritten war crimes report produced toward the end of 1944, a few months after the town was liberated by the Soviets. I later would get a full translation in the United States, but my Ukrainian translator gave me the gist of its contents, explaining that a team of Russian officers, local prosecutors and a few Holocaust survivors had dug up holes to count the bodies. Dubno was a mass grave. The war crimes investigators found that the executions began on June 30, 1941, the day the Germans took over Dubno, and continued on a regular basis,

PLEASE SEE FOLLOWING PAGE

A

3 4

castle on the Ikva River, a fortress in archive filled with Dubnos precious artifacts and documents. From a small glass cabinet in the

medieval times, was now a museum and

Over dinner in his home in Warsaw, Leon pauses to reflect on painful memories of the Holocaust and the toll the ordeal has taken on his health.

1 2 3 4 5 6

CHICAGO TRIBUNE

S E C T I O N 19

S P E C I A L R E P O RT

S U N D AY

NOVEMBER 30, 2003

Lydia Dzikowska lives in the old Sys family home in Dubno, now in Ukraine. Here Sonia spent the early years of her life surrounded by her extended family. Sonias grandfather, Schlomo, bought the large corner house with profits from his hops business. He lost ownership of both the house and the business to the Soviets.

CONTINUED FROM PREVIOUS PAGE

At first they dug a hole, then they took their clothes off and stood at the edge of the ground, by the hole, and the Germans shot at them with machine guns.

Olga Chernobaj, a Ukrainian, who as an 8-year-old witnessed the slaughter at Shibennaya Hill

transforming the town where my mother lived into a killing ground from which there was almost no escape. Unlike central and western Poland, where Jews often were sent long distances by rail or foot to concentration camps to die, in eastern Polish cities such as Dubno they were quickly rounded up in their hometowns, forced to dig their own mass graves, and shot. The methods of genocide had been altered because Hitler saw the Soviet Union and its occupied territories as emblems of a rival political system that needed to be crushed as quickly as possible. Jews were carriers of the bacillus of Communism, according to reports filed by the Einsatzgruppen, or special action groups, that served as mobile death squads operating in and around Dubno. Dubnos main commercial artery, Aleksandrowicz Street, a narrow, two-lane strip of dirt with tiny storefronts on either side, was renamed Hitler Street and was patrolled by German tanks and troops. My mothers cousin Leon remembered watching an old Jewish man being beaten on that street by German soldiers because he didnt get out of their way fast enough. As my mother turned 10, her little Dubno was an armed camp, its every street patrolled by German troops. Children no longer went to school, and their movements were severely restricted by military barricades. Meanwhile, the locals watched as their friends, relatives and acquaintances were paraded to their deaths. The witnesses I foundby approaching old Ukrainians in the street, knocking on doors and consulting the citys unofficial historiansaid they could not forget what happened. It was strangely calm and quiet when the Jews went to die, said Valentina Marcuk, a 79-year-old Ukrainian woman who sat up in bed to talk. Some of the Jews said to the people who stood along the street and watched, Do you see this happening? Dont watch quietly, because in just a little bit, you also will be taken. You are the next. It turned me inside out, she said. There is no minute that I could forget. Vadym Tovstorog, 80, who has lived in the same Dubno house since 1933, sat in his living room and recalled seeing his violin teacher and the teachers young daughter among a group taken to their deaths. I did not see them being killed, Tovstorog said,

RUSSIA Warsaw POLAND BELARUS

RUSSIA MAP AREA

Dubno

UKRAINE

HUNG.

MOLDOVA

ITALY

TURKEY

ROMANIA

200 MILES

B L AC K S E A

DUBNO STREET MAP 1940s Shibennaya Hill (4 kilometers west)

Sys family house

SK T. A S

Ghetto Synagogue

a Ikv

er Riv

A L E K S A N D R O W I C Z S T.

Chicago Tribune

but you did not have to see to know what happened. Everywhere Dubnos residents turned, in fact, they encountered death and dying. Even the idyllic waters of the Ikva River, which wound through the heart of Dubno, became a place where people were afraid to look. I saw three people lying in the Ikva River, near the bridgea man, his wife perhaps, and their

daughter, recalled Iryna Polischuk, 70, who was a child at the time. Their heads were underwater, and their bodies were on the banks of the river. Jews whose skills or strength were of value to the Germans often were allowed to live a while longer. By the end of the summer of 1941, thousands not selected for the first waves of executionsthe exact number is unknownwere moved to a ghetto a few blocks from the Sys familys former home. Stretching about 3 blocks wide and 3 blocks deep, the ghetto was bordered by barbed wire and wood, controlled by three main gates and enclosed at the rear by the Ikva River. This is where the Sys family was placed. Jews who could obtain work were escorted to their tasks in wagons policed by German troops. They were forced to wear yellow stars. Children, such as my mother, stayed indoors and waited. Once they got the Jews into the ghetto, our town became empty, quite emptyvery few people were on the streets anymore, except for the soldiers, Polischuk remembered. The largest massacres occurred on the outskirts of the city. Olga Chernobaj, a 70-year-old Ukrainian who was 8 years old at the time, told me she and a neighbor witnessed a massacre at Shibennaya Hill, just outside of Dubno. We couldnt get close up, but from the top of the hill I saw everything, she said. As we arrived, we saw that some of them already lay naked and shot. At first they dug a hole, then they took their clothes off and stood at the edge of the ground, by the hole, and the Germans shot at them with machine guns. And when we came, there were only two last groups of people who had yet to be killed, Chernobaj continued, pausing to regain her composure. First they dug the holes, then one group took their clothes off. Then they were shot, they fell, then other people came forward. And when the Jews fell, the Germans came to the hole and covered them with something white. I dont know what it was, maybe some chemical. And then they covered them with the ground. And sometimes the ground moved, because maybe somebody was still alive. Then some of the local people came to collect these clothes and chose what they wanted. Everything that Chernobaj described was detailed in the Dubno war crimes report. By digging up the sites where the killings occurred and interviewing the locals who observed the massacres, the investigators showed that Dubno had become a central location for executing Jews from across the region.

Nicola Bura, 14, picks wildflowers from a remote area outside Dubno called Shibennaya Hill, the site where thousands of Jews were stripped, shot by German soldiers and buried in layers six or seven deep on at least six dates between July 1941 and October 1942. Only a small marker alludes to what happened there.

1 2 3 4 5 6

PA NI EN

NOVEMBER 30, 2003

S U N D AY

S P E C I A L R E P O RT

S E C T I O N 19

CHICAGO TRIBUNE

Local boys fish in the Ikva River just behind the old Sys family home in Dubno. A playful place before the war, where children tossed stones and learned to swim, the river, which wound through the heart of Dubno, became a barrier that trapped people in the Jewish ghetto and a place where bodies were found.

This day, begins the report, we arrived at the excavation site, 4 km west of Dubno in the direction of the village of Kleshchikha, in the vicinity of the Shibennaya Hill, where in a gorge we discovered corpses of shot and killed peaceful people of Jewish nationality from the Dubno, Verba and Ostrozhets districts. The total area of all three pits is 900 sq. m, 4 m deep, where there are 6,000 shot and killed people. During the excavation it has been found that there are six to seven layers of corpses of shot people, lying with their faces down. Each layer has up to 21 rows of shot and killed people and is covered with chlorinated lime. The fact that the corpses are naked and lie with their faces down indicates that the shots were aimed at the back of the head and the rear area of the thorax. The killings at Shibennaya Hill took place on at least six dates between July 27, 1941, and Oct. 24, 1942, with 4,000 killed on the last two dates alone. And that was only at Shibennaya Hill. The report also details executions of 650 Jews in the streets of central Dubno, more than 3,500 at the stadium grounds about a mile from the Sys home and as many as 5,000 on the old airfield. In the Vygnanka settlement on the outskirts of Dubno, bodies were dumped near the side of a road. In the center of Dubno, bodies were covered with bricks, empty cans, iron, bottles and a half inch of manure. Some of the executions of Jews took place as civic events, such as one on June 4, 1942, when about 1,000 people were forced into a pit and shot with submachine guns. This had been preceded by a festive reception [with] guests, notes the report, who were present when the women and children were being killed and were applauding successful shots.

In the former Dubno ghetto (above), walls still are painted with colors that match the nearby central synagogue (below), shown in a 1930s photo. The old synagogue now is used to store recycled garbage.

with leaves, and some people were hiding in there. The Germans came, surrounded them and dragged them out of the forest. There were four boysmaybe ages 11 or 12and two girls, one perhaps 8, one perhaps 10, and an older woman with them. The Germans told the children to lie on the ground and began to torture the womanperhaps they wanted to know if there were other children hidden. They struck the woman two times on the head. Then all the policemen, except one, turned around, and one of them killed all the children. I saw this with my own eyes. My mother survived in forests and on farms, until by chance she encountered a friend of Irenes in a Polish village outside Dubno. The friend, also surviving on false papers, went by the name Clara and eventually became Irenes sister-in-law. Clara Tannen, who now lives in Toronto, didnt want to discuss her experiences, but Irene described what happened next. Your mother was maybe 12 years old, and she could not even acknowledge out loud that she knew Clara, because one Jew did not want to show that

PLEASE SEE FOLLOWING PAGE

It was clear that this was the end. We knew that we must escape from here, because everybody will be killed.

Irene Tannen, Sonia Reichs aunt

Out of the ghetto, running for her life

isted to show exactly which one. It was hard to imagine how so many people could live crammed into a 9-square-block area. It was clear that this was the end, Irene Tannen had told me when I visited her in the U.S. We knew that we must escape from here, because everybody will be killed. Irene, who fled the ghetto in the summer of 1942, was the last surviving relative to see my mother in Dubno. Irenes mother obtained false papers from a Dubno priest that christened Irene with a new last name: Sakowska. False documents in hand, she escaped. When I left, Sonia was still there, Irene said. Since most Dubno Jews had been killed by October 1942, according to the war crimes report, my mother presumably escaped before then. Though my mother told me little about how she fled, she once confided that she climbed out the window of the ghetto room. She carried false papers that provided her with a new name: Zosia. She didnt tell me the last name she was given. Zosia later was translated to Sonia in the U.S. She left behind her mother, who was still alive in the ghetto, as well as cousins, aunts and uncles everyone she knew and trusted. They never were heard from again. Unlike Irene, who was 19 years old and capable of finding office work using her false papers, my mother, who was about 11, had no such option. And unlike her cousin Leon, who was fleeing with his sister, my mother had no companion, instead mak-

s I walked the dilapidated area that once was Dubnos Jewish ghetto, I knew that my mother and the rest of the family had lived in one of these aging, rotted shacks, though no records exing her way alone through the villages beyond Dubno. Only my mother knows what happened to her in the year or two she was on her own. But the conditions were severe, judging from the only account of her experiences available: an evaluation that a German-appointed physician penned on June 2, 1966, after my mother applied for compensation for harm done. She ran far away from Dubno and had various hiding places with peasants constantly afraid to be caught by the Germans, according to the physicians assessment. She got her hands and feet frostbitten since she had to sleep outside most of the time. During this time she developed back trouble and became very nervous because she lived in constant fear. Uncounted children like my mother hid across Poland, emerging periodically to beg for work on farms. They were at the mercy of strangers, some more generous than others. The children were hungry, dirty, desperate and in perpetual fear for their lives. After a couple of days in Dubno, I began venturing to villages outside the city, hoping to find someone who might have seen the plight of these children. Mykola Tarasiuk, a 79-year-old Ukrainian who lives in the village of Malin, about 50 miles from Dubno, still had vivid recollections of what he had witnessed in the countryside. There were children and families hiding in the forest. I saw them, in the forest 2 or 3 kilometers from here, in October of 1942, he said. And then the German policemen came. It was autumn, and those Jews in the forest couldnt even make a big fire, because they were afraid people will see them. There were holes in the forest ground, covered

Whenever we heard some heavy steps on the stairs, we were thinking that it was probably [the Nazis] to pick us up, said Sonias aunt Irene Tannen, who hid with her in Poland.

2 3 4 5 6

CHICAGO TRIBUNE

S E C T I O N 19

SPECIAL S CO T RT ION REP

??

S U N D AY

NOVEMBER 30, 2003

CONTINUED FROM PREVIOUS PAGE

she recognized another Jew, and give away the secret, Irene recalled. Later, however, Clara and my mother spoke to each other in private, and Clara decided to take a risk. She brought my mother to Irene, whom Clara knew to be living in another village. Your mother was filthy, dirty, with lice all over, and Clara cleaned her up, Irene said. My mother and Irene spent the last year or so of the war hiding together in various Polish towns. Irene often worked in an office under false papers, while my mother frequently took care of children for Polish families. They lived in constant fear they might be discovered. At one point we were living on the second floor of a house, and whenever we heard some heavy steps on the stairs, we were thinking that it was probably to pick us up, Irene said. By the end of the war, their hometown was decimated. More than 99 percent of Dubnos Jewish population had been executed and buried in more than 55 pits scattered across the city and its surroundings. The bodies lay in unmarked holes that were covered over and soon served once again as ordinary street corners, fields and ravines. My mother never returned to Dubno. But Irene went back in 1945 to see if she could find any surviving relatives. As she expected, she couldnt. With the help of a Jewish cultural organization, she eventually located her nephew and niece, Leon and Fanka, in the tiny village of Ozirko, and brought them back to Warsaw. Irene never saw her hometown again, but most of her family and mine was buried there. As I prepared to depart Dubno, my notebook was filled with the details of events there, but I had only begun to absorb their meaning. In the car leaving town, I listened to a CD given to me by a local singer, Galina Mosijchuk, whose father had been executed by the Germans in Dubno. Her lamenting folk songs, unfolding at the tempo of a dirge, gave voice to a sorrow I never before had felt.

War orphan finds new start, struggles

y mother never told me why she wanted to start over in the U.S., but its not difficult to imagine a desire to flee the place where virtually everyone you knew and

loved was executed. The Jewish Childrens Bureau helped my mother find relatives in Chicago by placing a newspaper announcement in the Chicago Daily News. On Sept. 21, 1947, she stepped off the SS Ernie Pyle in New York. When she arrived at Chicagos LaSalle Street Station on Oct. 2, the Daily News covered the event in a brief news story. Three teen-aged Jewish war orphans from Poland met their American foster mothers today in LaSalle Street Station, read the upbeat report, which I found in my mothers house. They were greeted with warm smiles and kisses by the mothers, who gave the children ice cream. When I asked my mother about the article, she said that she was so nauseated from the journey to Chicago by sea and rail that, after her first lick of ice cream, she threw up. Her foster mother, a younger sister of her grandfathers who lived in America, did not send her to school. Instead, she put my mother to work doing clerical tasks in the familys small publishing business, an arrangement my mother said she did not like and quit. So at about age 16, she went to live in a room in a boarding house on the South Side. She worked in factories until she met Robert Reich. No one knows how much, or how little, she said to him about what she saw and experienced during the war. But the German evaluation of 1966 revealed the extent of her psychological damage. Her years in flight left her with neurotic disorders caused by the hardship in the ghetto and in hiding during her childhood, according to the report by the German-appointed physician. The applicant suffers from a severe anxiety neurosis with some depression. My mother struggled to put her past behind her, rarely talking about it. This enabled her to carry on with her life. Much of the medical literature on late-onset PTSD notes that a stressful event late in life, such as an illness or an important anniversary, can push a person who has been coping with bad memories into a realm of delusion and paranoia. My mother fled her Skokie home on Feb. 15, 2001 the eve of the 10th anniversary of my fathers death.

Sonia gives a farewell hug to her son, Howard, after a recent visit at the nursing home. On the table is the bag that Sonia keeps packed with bread, toilet paper and other supplies she asks Howard to bring her.

But when I arrived in my mothers room, she was seething over something that had happened in the nursing home a few days earlier and refused to talk about anything else. There had been a small fire on another floor of the building, the staff told me, and in order to clean up water damage, all the patients were asked to leave their rooms and gather in the dining area. My mother refused, so the orderlies came to her room and ushered her out to the waiting group. But she sneaked away and headed back to her room. Again the orderlies escorted her where everyone else was gathered, and again she slipped away. The third time she did this, she was given an antipsychotic drug. She then refused to get out of her chair and was brought back to the dining room still sitting in it. They have no right to make me gowho do they think they are? my mother yelled at me. A few days later, I returned to the nursing home with photos in hand. She had calmed down from the last visit and looked curious about what I was pulling out of a large manila envelope. I showed her a photo of Aleksandrowicz Street, Dubnos sole commercial road, its age-old buildings and ancient Catholic church looking as if they hadnt changed in centuries. I showed her the old central synagogue, now used to store recycled garbage, its windows shattered and paint peeling. I showed her the Sys family home, an old lady in a babushka standing in front of it, using a walking stick to wave away a parade of geese. But as soon as my mother began to study the pictures, she became agitated, the volume and tension of her voice rising, the movement of her arms becoming emphatic. I told my mother I had gone inside her grandfathers house, into the park across the street and onto the banks of the river out back. I told her I had met with Leon and Irene, who helped me piece together so many parts of her story. I told her I now understood what had happened in Dubno. My mother listened to me but could not take her eyes off the pictures. Though her delusions often prompted her to deny factssuch as the existence of her grandchildren, who she insisted had been taken away from my sisterthis time there were no denials, no disputations of these concrete images. After a minute or two, she said, sharply, I dont want to know about Leon; I dont want to know about Irene, meanwhile staring intensely at photos of them and their little town of Dubno. You can pack up the pictures and put them back in the envelope, she said. I do not want to remember this. With those words, my mother seemed to close off any possibility of telling me more about her early life. Yet considering what I now knew, the surprise was not that she was still trying to bury the pastor that it still tormented herbut that she had survived her memories for so many decades. My parents once were young and full of hope. But it wasnt until my father was gone and my mother was half removed from reality that I finally could bear to look at what they endured. In my mothers room, I continued to talk to her about the photos, but she only grew angrier. When she lifted her arm and started to sweep the photos onto the floor, I grabbed them and stuffed them back into the envelope. My mother started to relax. We resumed discussing the events of the daythe weather, the news, the family gossip. As always during our visits, she began packing the bread I brought her into small plastic bags before placing them into her fanny pack. When I was a schoolboy, those same tiny hands created bulging sandwiches for me, wrapping them in one layer of plastic atop another before depositing them in my lunch bag. Back then, I wondered why she lavished so much time and attention on a meal I would devour in minutes. I had no idea of the significance that foodor the lack of itonce had in her life. Nor did I imagine how much of an obsession it would become in her old age. No doctor I consulted could convince her that she neednt hoard food anymore. None could get her to understand that her fears of being left hungry and desperate again were unfounded, that no one was trying to kill her, and that she no longer needed to run. My pictures of Dubno, which struck a certain chord in her memory, ultimately did nothing to help her. And probably nothing will. Yet as my mother stood up to walk me out after our visit, her somewhat worn clothes hanging on a slender, slightly stooped frame, I looked at her with newfound awe. I doubted that I could have survived what she suffered. And her refusal to allow doctors and nurses to help her now seemed to me a reflection of the same extraordinary resolve that had enabled her to live through the Holocaust. My mother was 72, alone and frightened, but the journey to Dubno allowed me to begin to understand her for the first time. Now, when she railed about the visions she saw, I could see them too. As we approached the elevator, my mother hugged me twice and said goodbye. Dont be such a strangervisit more often, she said, as the elevator doors closed.

Slamming the door on images of past

fter I returned from Dubno, I went to the tos of the house she once lived in, the streets where she played and the riverbank where she and Leon whiled

nursing home to show my mother pho-

away the afternoons before the war. I wanted to tell her what I had seen and learned.

I dont want to know about Leon; I dont want to know about Irene. You can pack up the pictures and put them back in the envelope. I do not want to remember this.

Sonia Reich

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- Love Me to Death: A Journalist's Memoir of the Hunt for Her Friend's KillerD'EverandLove Me to Death: A Journalist's Memoir of the Hunt for Her Friend's KillerÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (2)

- Confessions of a Jewish Shiksa: The Second Greatest Story Ever ToldD'EverandConfessions of a Jewish Shiksa: The Second Greatest Story Ever ToldPas encore d'évaluation

- Bending Toward the Sun: A Mother and Daughter MemoirD'EverandBending Toward the Sun: A Mother and Daughter MemoirÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (32)

- Sophie's Choice by William Styron (Book Analysis): Detailed Summary, Analysis and Reading GuideD'EverandSophie's Choice by William Styron (Book Analysis): Detailed Summary, Analysis and Reading GuidePas encore d'évaluation

- A WOMAN IN NEED BREAKING FREE FROM GENERATIONAL CURSES AND WITCHCRAFTD'EverandA WOMAN IN NEED BREAKING FREE FROM GENERATIONAL CURSES AND WITCHCRAFTPas encore d'évaluation

- Happiness Is a Choice You Make: Lessons from a Year Among the Oldest OldD'EverandHappiness Is a Choice You Make: Lessons from a Year Among the Oldest OldÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (43)

- SMOKE RINGS RISING: Triumph of a Drug-Endangered DaughterD'EverandSMOKE RINGS RISING: Triumph of a Drug-Endangered DaughterPas encore d'évaluation

- Queen of the Night: A Novel of SuspenseD'EverandQueen of the Night: A Novel of SuspenseÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (109)

- Mental Traveler: A Father, a Son, and a Journey through SchizophreniaD'EverandMental Traveler: A Father, a Son, and a Journey through SchizophreniaPas encore d'évaluation

- Yossarian Slept Here: When Joseph Heller Was Dad, the Apthorp Was Home, and Life Was a Catch-22D'EverandYossarian Slept Here: When Joseph Heller Was Dad, the Apthorp Was Home, and Life Was a Catch-22Évaluation : 3 sur 5 étoiles3/5 (4)

- Secrets of the Asylum: Norwich State Hospital and My FamilyD'EverandSecrets of the Asylum: Norwich State Hospital and My FamilyPas encore d'évaluation

- The Art of Inventing Hope: Intimate Conversations with Elie WieselD'EverandThe Art of Inventing Hope: Intimate Conversations with Elie WieselPas encore d'évaluation

- A Light in the Dark: Surviving More than Ted BundyD'EverandA Light in the Dark: Surviving More than Ted BundyPas encore d'évaluation

- Ghosts and the Spirit World: True cases of hauntings and visitations from the earliest records to the present dayD'EverandGhosts and the Spirit World: True cases of hauntings and visitations from the earliest records to the present dayÉvaluation : 1 sur 5 étoiles1/5 (1)

- Sometimes My Leqerville Friends Left Our Apartment Through the Front Door: The Life of an American ScientistD'EverandSometimes My Leqerville Friends Left Our Apartment Through the Front Door: The Life of an American ScientistPas encore d'évaluation

- Never Tell: recovered memories of a daughter of the Knights TemplarD'EverandNever Tell: recovered memories of a daughter of the Knights TemplarPas encore d'évaluation

- I, Albert Peabody: Confessions of a Serial KillerD'EverandI, Albert Peabody: Confessions of a Serial KillerPas encore d'évaluation

- Summary and Analysis of Their Eyes Were Watching God: Based on the Book by Zorah Neale HurstonD'EverandSummary and Analysis of Their Eyes Were Watching God: Based on the Book by Zorah Neale HurstonPas encore d'évaluation

- Henry Zvi Lothane, MD The Real Story of Sabina Spielrein: or Fantasies vs. Facts of A LifeDocument13 pagesHenry Zvi Lothane, MD The Real Story of Sabina Spielrein: or Fantasies vs. Facts of A LifeIwona Barbara Jozwiak100% (1)

- "ARE YOU KIDDING?" A Lifer's View of The Death PenaltyDocument4 pages"ARE YOU KIDDING?" A Lifer's View of The Death PenaltyBarbara BergmannPas encore d'évaluation

- Annotations and Comment On PieceDocument10 pagesAnnotations and Comment On PieceOliver RaymondPas encore d'évaluation

- Inquiry2 Evidence3 LastnameDocument5 pagesInquiry2 Evidence3 Lastnameapi-311734632Pas encore d'évaluation

- Movie AnalysisDocument5 pagesMovie AnalysisAndrea Autor100% (1)

- Hindustan Coca-Cola Beverages PVT LTD B-91 Mayapuri Industrial Area Phase-I New DelhiDocument2 pagesHindustan Coca-Cola Beverages PVT LTD B-91 Mayapuri Industrial Area Phase-I New DelhiUtkarsh KadamPas encore d'évaluation

- 004 Torillo v. LeogardoDocument2 pages004 Torillo v. LeogardoylessinPas encore d'évaluation

- Curriculum Vitae (CV) - Design-AM-KAWSAR AHMEDDocument5 pagesCurriculum Vitae (CV) - Design-AM-KAWSAR AHMEDEngr.kawsar ahmedPas encore d'évaluation

- The Power of Partnership: Underground Room & Pillar Lateral Development and DownholesDocument4 pagesThe Power of Partnership: Underground Room & Pillar Lateral Development and DownholesjoxegutierrezgPas encore d'évaluation

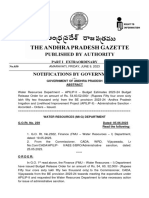

- Gazettes 1686290048232Document2 pagesGazettes 1686290048232allumuraliPas encore d'évaluation

- Assessment of Reading Comprehension 2Document8 pagesAssessment of Reading Comprehension 2Kutu DemangPas encore d'évaluation

- CoasteeringDocument1 pageCoasteeringIrishwavesPas encore d'évaluation

- 327 - Mil-C-15074Document2 pages327 - Mil-C-15074Bianca MoraisPas encore d'évaluation

- Roadshow Advanced 7.2 V3.2 221004 FinalDocument347 pagesRoadshow Advanced 7.2 V3.2 221004 FinalEddy StoicaPas encore d'évaluation

- Presented By: Priteshi Patel: Previously: Kentucky Fried ChickenDocument33 pagesPresented By: Priteshi Patel: Previously: Kentucky Fried Chickensandip_1Pas encore d'évaluation

- Chapter1-The Clinical LabDocument24 pagesChapter1-The Clinical LabNawra AhmadPas encore d'évaluation

- Silicon Epitaxial Planar Transistor 2SA1179: Galaxy ElectricalDocument5 pagesSilicon Epitaxial Planar Transistor 2SA1179: Galaxy ElectricalsacralPas encore d'évaluation

- Flexible Learnin G: Group 3 Bsed-Math 2Document48 pagesFlexible Learnin G: Group 3 Bsed-Math 2Niña Gel Gomez AparecioPas encore d'évaluation

- 8th Semester Mechanical Engineering Syllabus (MG University)Document17 pages8th Semester Mechanical Engineering Syllabus (MG University)Jinu MadhavanPas encore d'évaluation

- Cell Reproduction Practice ExamDocument5 pagesCell Reproduction Practice Examjacky qianPas encore d'évaluation

- 1716 ch05Document103 pages1716 ch05parisliuhotmail.comPas encore d'évaluation

- Scaffolding-Fixed and Mobile: Safety Operating ProceduresDocument1 pageScaffolding-Fixed and Mobile: Safety Operating Proceduresmohammed muzammilPas encore d'évaluation

- A Guide To Patient Medication Review: September 2003Document33 pagesA Guide To Patient Medication Review: September 2003Muhamad GunturPas encore d'évaluation

- HSE Issues Tracker - DAFDocument28 pagesHSE Issues Tracker - DAFMohd Abdul MujeebPas encore d'évaluation

- Module-1-ISO 13485-DocumentDocument7 pagesModule-1-ISO 13485-Documentsri manthPas encore d'évaluation

- Joint Venture Accounts Hr-7Document8 pagesJoint Venture Accounts Hr-7meenasarathaPas encore d'évaluation

- CFM56 3Document148 pagesCFM56 3manmohan100% (1)

- Experiment-3: Study of Microstructure and Hardness Profile of Mild Steel Bar During Hot Rolling (Interrupted) 1. AIMDocument5 pagesExperiment-3: Study of Microstructure and Hardness Profile of Mild Steel Bar During Hot Rolling (Interrupted) 1. AIMSudhakar LavuriPas encore d'évaluation

- JeromeDocument2 pagesJeromeNads DecapiaPas encore d'évaluation

- Transmission Line BOQ VIMPDocument72 pagesTransmission Line BOQ VIMPkajale_shrikant2325Pas encore d'évaluation

- Alfa Laval M6: Gasketed Plate Heat Exchanger For A Wide Range of ApplicationsDocument2 pagesAlfa Laval M6: Gasketed Plate Heat Exchanger For A Wide Range of ApplicationsCyrilDepalomaPas encore d'évaluation

- Annual Report - TakedaDocument50 pagesAnnual Report - TakedaAbdullah221790Pas encore d'évaluation

- Antithesis Essay Joseph JaroszDocument3 pagesAntithesis Essay Joseph JaroszJoseph JaroszPas encore d'évaluation

- Public Places 9 & 10Document2 pagesPublic Places 9 & 10kaka udinPas encore d'évaluation

- BPT Notes Applied PsychologyDocument36 pagesBPT Notes Applied PsychologyVivek Chandra0% (1)