Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Infections of The Urinary Tract

Transféré par

Stephanie Louisse Gallega HisoleTitre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Infections of The Urinary Tract

Transféré par

Stephanie Louisse Gallega HisoleDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

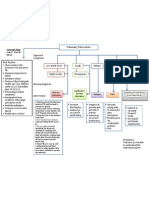

Infections of the Urinary Tract Urinary tract infections (UTIs) are caused by pathogenic microorganisms in the urinary tract

(the normal urinary tract is sterile above the urethra). UTIs are generally classified as infections involving the upper or lower urinary tract (Chart 45-1). Lower UTIs include bacterial cystitis (inflammation of the urinary bladder), bacterial prostatitis(inflammation of the prostate gland), and bacterial urethritis (inflammation of the urethra). There can be acute or chronic nonbacterial causes of inflammation in any of these areas that can be misdiagnosed as bacterial infections. Upper UTIs are much less common and include acute or chronic pyelonephritis (inflammation of the renal pelvis), interstitial nephritis(inflammation of the kidney), and renal abscesses. Upper and lower UTIs are further classified as uncomplicated or complicated, depending on other patient-related conditions (for example, whether the UTI is recurrent and the duration of the infection). Most uncomplicated UTIs are community-acquired. Complicated UTIs usually occur in people with urologic abnormalities or recent catheterization and are often hospital-acquired. Bacteriuria and UTIs are more common in persons older than 65 years of age than in younger adults. Conservative estimates suggest that 20% to 25% of ambulatory women and 10% of men in this age group have asymptomatic bacteriuria; the incidence rises to 50% in women over the age of 80 (Gomolin & McCue, 2000). A UTI is one of the most common reasons patients seek health care. Most cases occur in women, with one of every five women in the United States developing a UTI sometime during her lifetime. The urinary tract is the most common site of nosocomial infection, accounting for greater than 40% of the total number Classifying Urinary Tract Infections Urinary tract infections (UTIs) are classified by location: the lower urinary tract (which includes the bladder and structures below the bladder) or the upper urinary tract (which includes the kidneys and ureters). They can also be classified as uncomplicated or complicated UTI. Lower UTI Cystitis, prostatitis, urethritis Upper UTI Acute pyelonephritis, chronic pyelonephritis, renal abscess, interstitial nephritis, perirenal abscess

Uncomplicated Lower or Upper UTI Community-acquired infection; common in young women Complicated Lower or Upper UTI Often nosocomial (acquired in the hospital) and related to catheterization; occurs in patients with urologic abnormalities, pregnancy, immunosuppression, diabetes mellitus, obstructions Chart 45-1 Chart 45-1 reported by hospitals and affecting about 600,000 patients each year. In most of these hospital-acquired UTIs, instrumentation of the urinary tract or catheterization is the precipitating cause. More than 250,000 cases of acute pyelonephritis occur in the United States each year, with 100,000 of these patients requiring hospitalization. In general, 7 to 8 million UTIs are diagnosed in the United States annually, representing an expenditure of about $1 billion in direct heath care costs. This amount does not include the indirect costs associated with time lost from work and the negative impact on the individuals lifestyle (Foxman, 2002). LOWER URINARY TRACT INFECTIONS Several mechanisms maintain the sterility of the bladder: the physical barrier of the urethra, urine flow, ureterovesical junction competence, various antibacterial enzymes and antibodies, and antiadherent effects mediated by the mucosal cells of the bladder. Abnormalities or dysfunctions of these mechanisms are contributing factors to lower UTIs (Chart 45-2). ROUTES OF INFECTION There are three well-recognized routes by which bacteria enter the urinary tract: up the urethra (ascending infection), through the bloodstream, (hematogenous spread), or by means of a fistula from the intestine (direct extension). The most common route of infection is transurethral, in which bacteria (often from fecal contamination) colonize the periurethral area and subsequently enter the bladder by means of the urethra. In women, the short urethra offers little resistance to the movement of uropathogenic bacteria. Sexual intercourse or massage of the urethra forces the bacteria up into the bladder. This accounts for the increased incidence of UTIs in sexually active women. Bacteria may also enter the urinary tract by means of the blood (hematogenous spread) from a distant site of infec-

tion or through direct extension by way of a fistula from the intestinal tract. Clinical Manifestations A variety of signs and symptoms are associated with UTI. About half of all patients with bacteriuria have no symptoms. Signs and symptoms of uncomplicated lower UTI (cystitis) include frequent pain and burning on urination, frequency, urgency, nocturia, incontinence, and suprapubic or pelvic pain. Hematuria and back pain may also be present. In older individuals, these typical symptoms are seldom noted (see Gerontologic Considerations, below). Signs and symptoms of upper UTI (pyelonephritis) include fever, chills, flank or low back pain, nausea and vomiting, headache, malaise, and painful urination. Physical examination reveals pain and tenderness in the area of the costovertebral angles (CVA), which are the angles formed on each side of the body by the bottom rib of the rib cage and the vertebral column (Fig. 45-2). In patients with complicated UTIs, such as those with indwelling catheters, manifestations can range from asymptomatic bacteriuria to a gram-negative sepsis with shock. Complicated UTIs often are due to a broader spectrum of organisms, have a lower response rate to treatment, and tend to recur. Many patients with catheter-associated UTIs are asymptomatic; however, any patient who suddenly develops signs and symptoms of septic shock should be evaluated for urosepsis. Assessment and Diagnostic Findings Results of various tests, such as colony counts, cellular studies, and urine cultures, help confirm the UTI diagnosis. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) recommends that all pregnant women be screened for asymptomatic bacteriuria since pregnancy itself is a risk factor for UTI because the bladder does not empty as well as it normally does. In an uncomplicated UTI, the strain of bacteria will determine the antibiotic of choice. COLONY COUNTS UTI is diagnosed by bacteria in the urine. A colony count of at least 10 5 colony-forming units (CFU) per milliliter of urine on a clean-catch midstream or catheterized specimen is a major criterion for infection. However, UTI and subsequent sepsis have oc-

curred with lower bacterial colony counts. About one third of women with symptoms of acute infections have negative midstream urine culture results and may go untreated if 10 5 CFU/mL is used as the criterion for infection. The presence of any bacteria in specimens obtained by suprapubic needle aspiration of the urinary bladder or catheterization is considered indicative of infection. CELLULAR STUDIES Microscopic hematuria (greater than 4 red blood cells [RBCs] per high-power field) is present in about half of patients with acute infection. Pyuria (greater than 4 white blood cells [WBCs] per high-power field) occurs in all patients with UTI; however, it is not specific for bacterial infection. Pyuria can also be seen with kidney stones, interstitial nephritis, and renal tuberculosis. URINE CULTURES Urine cultures remain the gold standard in documenting a U and can identify the specific organism present. Because of high probability that the organism in young women with th first UTI is E. coli, cultures are often omitted. The following grou of patients should have urine cultures obtained when bacteriu is present: All men (because of the likelihood of structural or fu tional abnormalities) All children Women with a history of compromised immune functi or renal problems Patients with diabetes mellitus Patients who have undergone recent instrumentation ( cluding catheterization) of the urinary tract Patients who were hospitalized recently Patients with prolonged or persistent symptoms Patients with three or more UTIs in the past year Pregnant women Postmenopausal women Women who are sexually active or have new partners TESTING METHODS Multistrip dipstick testing for WBCs, known as the leukocyte esterase test, and nitrite testing (Griess nitrate reduction test) are common. If the leukocyte esterase test is positive, it is assumed

that the patient has pyuria (WBCs in the urine) and should be treated. The Griess nitrate reduction test is considered positive if bacteria that reduce normal urinary nitrates to nitrites are present. Tests for sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) may be performed because acute urethritis caused by sexually transmitted organisms (ie, Chlamydia trachomatis, Neisseria gonorrhoeae,herpes simplex) or acute vaginitis infections (caused by Trichomonas or Candida species) may be responsible for symptoms similar to those of UTI. Therefore, evaluation for STDs may be performed (see Chap. 70). Historically, intravenous pyelography (IVP) was used to detect abnormalities in patients at high risk for complicated or recurring UTI. Today, diagnostic studies such as computed tomography (CT) and ultrasonography are preferred detection methods for several reasons: CT scans may detect areas of pyelonephritis or abscesses, and ultrasonography is extremely sensitive for detecting obstruction, abscesses, tumors, and cysts. Transrectal ultrasonography (to assess the prostate and bladder) is the procedure of choice for men with recurrent or complicated UTIs. An IVP may be indicated to visualize the ureters or to detect strictures or stones and is necessary for an accurate diagnosis of reflux nephropathy. It is generally accepted that the first episode of UTI in women does not require urologic evaluation (Hooton, Scholes, Stapleton et al., 2000). Medical Management Management of UTIs typically involves pharmacologic therapy and patient education. The nurse is a key figure in teaching the patient about medication regimens and infection prevention measures. Controversy continues about the need for treatment of asymptomatic bacteriuria in the institutionalized elderly patient because resulting antibiotic-resistant organisms and sepsis may be greater threats to the patient. Most experts now recommend withholding antibiotics unless symptoms develop. Treatment regimens, however, are generally the same as those for younger adults, although age-related changes in the intestinal absorption of medications and decreased renal function and hepatic flow may necessitate alterations in the antimicrobial regimen. Renal function must be monitored and the dosage of medications altered accordingly. ACUTE PHARMACOLOGIC THERAPY

The ideal treatment of UTI is an antibacterial agent that eradicates bacteria from the urinary tract with minimal effects on fecal and vaginal flora, thereby minimizing the incidence of vaginal yeast infections. (Yeast vaginitis occurs in as many as 25% of patients treated with antimicrobial agents that affect vaginal flora. Yeast vaginitis often causes more symptoms and is more difficult and costly to treat than the original UTI.) Additionally, the antibacterial agent should be affordable and should produce few adverse effects and low resistance. Because the organism in initial, uncomplicated UTIs in women is most likely E. coli or other fecal flora, the agent should be effective against these organisms. Various treatment regimens have been successful in treating uncomplicated lower UTIs in women: single-dose administration, short-course (3 to 4 days) medication regimens, or 7- to 10-day therapeutic courses. The trend is toward a shortened course of antibiotic therapy for uncomplicated UTIs because about 80% of cases are cured after 3 days of treatment. In a complicated UTI (ie, pyelonephritis), the general treatment of choice is usually a cephalosporin or an ampicillin/aminoglycoside combination. Patients in institutional settings may require 7 to 10 days of medication for the treatment to be effective. Other commonly used medications include trimethoprimsulfamethoxazole (TMP-SMZ, Bactrim, Septra) and nitrofurantoin (Macrodantin, Furadantin). Occasionally, medications such as ampicillin or amoxicillin are used, but E. coliorganisms have developed resistance to these agents. Recent clinical trials comparing the use of TMP-SMZ and the fluoroquinolone ciprofloxacin (Cipro) found ciprofloxacin to be significantly more effective in community-based patients and in nursing home residents (Gomolin & McCue, 2000; Talan et al., 2000). Levofloxacin (Levaquin), another fluoroquinolone, is a good choice for short-course therapy of uncomplicated, mild to moderate UTI. Clinical trial data show high patient compliance with the 3-day regimen (95.6%) and a high eradication rate for all pathogens (96.4%). Before using levofloxacin in patients with complicated UTIs, the causative pathogen should be identified. Levofloxacin is used only when generic and less costly antibiotics are likely to be ineffective (Bonapace et al., 2000). Nitrofurantoin should not be used in patients with renal insufficiency because it is ineffective at glomerular filtration rates (GFRs) of less than 50 mL/min and may cause peripheral neuropathy. Phenazopyridine (Pyridium), a urinary analgesic, may be

prescribed to relieve the discomfort associated with the infection. Regardless of the regimen prescribed, the patient is instructed to take all the doses prescribed, even if relief of symptoms occurs promptly. Longer medication courses are indicated for men, pregnant women, and women with pyelonephritis and other types of complicated UTIs. In pregnant women, amoxicillin, ampicillin, or an oral cephalosporin is used for 7 to 10 days. NURSING PROCESS: THE PATIENT WITH LOWER URINARY TRACT INFECTION Nursing care of the patient with lower UTI focuses on treating the underlying infection and preventing its recurrence. Assessment A history of signs and symptoms related to UTI is obtained from the patient with a suspected UTI. The presence of pain, frequency, urgency, and hesitancy and changes in urine are assessed, documented, and reported. The patients usual pattern of voiding is assessed to detect factors that may predispose him or her to UTI. Infrequent emptying of the bladder, the association of symptoms of UTI with sexual intercourse, contraceptive practices, and personal hygiene are assessed. The patients knowledge about prescribed antimicrobial medications and preventive health care measures is also assessed. Additionally, the urine is assessed for volume, color, concentration, cloudiness, and odor, all of which are altered by bacteria in the urinary tract. Diagnosis NURSING DIAGNOSES Based on the assessment data, the nursing diagnoses may include the following: Acute pain related to inflammation and infection of the urethra, bladder, and other urinary tract structures Deficient knowledge related to factors predisposing the patient to infection and recurrence, detection and prevention of recurrence, and pharmacologic therapy COLLABORATIVE PROBLEMS/ POTENTIAL COMPLICATIONS Based on assessment data, the following complications may develop: Renal failure due to extensive damage of kidney Sepsis

Planning and Goals Major goals for the patient may include relief of pain and discomfort; increased knowledge of preventive measures and treatment modalities; and absence of complications. Nursing Interventions RELIEVING PAIN The pain associated with UTI is quickly relieved once effective antimicrobial therapy is initiated. Antispasmodic agents may also be useful in relieving bladder irritability and pain. Aspirin and applying heat to the perineum help relieve pain and spasm. The patient is encouraged to drink liberal amounts of fluids (water is the best choice) to promote renal blood flow and to flush the bacteria from the urinary tract. Urinary tract irritants (eg, coffee, tea, citrus, spices, colas, alcohol) are avoided. Frequent voiding (every 2 to 3 hours) is encouraged to empty the bladder completely because this can significantly lower urine bacterial counts, reduce urinary stasis, and prevent reinfection. MONITORING AND MANAGING POTENTIAL COMPLICATIONS Early recognition of UTI and prompt treatment are essential to prevent recurrent infection and the possibility of complications, such as renal failure and sepsis. The goal of treatment is to prevent infection from progressing and causing permanent renal damage and renal failure. Thus, the patient must be taught to recognize early signs and symptoms, to test for bacteriuria, and to initiate treatment as prescribed. Appropriate antimicrobial therapy, liberal fluid intake, frequent voiding, and hygienic measures are commonly prescribed for managing UTI. The patient is instructed to notify the physician if fatigue, nausea, vomiting, or pruritus occurs. Periodic monitoring of renal function (creatinine clearance, blood urea nitrogen [BUN], and serum creatinine levels) may be indicated for patients with repeated UTIs. If extensive renal damage does occur, dialysis may be necessary. Patients with UTI, especially catheter-associated infection, are at increased risk for Gram-negative sepsis. Indwelling catheters should be avoided if possible and removed at the earliest opportunity (Thees & Dreblow, 1999). If an indwelling catheter is necessary, however, specific nursing interventions are initiated to prevent infection (see Chap. 44). These include the following: Using strict aseptic technique during insertion of the smallest catheter possible

Securing the catheter with tape to prevent movement Frequently inspecting urine color, odor, and consistency Performing meticulous daily perineal care with soap and water Maintaining a closed system Using the catheters port to obtain urine specimens Careful assessment of vital signs and level of consciousness may warn of impending sepsis. Blood cultures that are positive for inection and elevated WBC counts are reported to the physician. At he same time, appropriate antibiotic therapy and increased fluid intake are prescribed (intravenous antibiotic therapy and fluids may be required). Preventing sepsis is key because the mortality rate for Gram-negative sepsis is significant, especially in elderly patients. PROMOTING HOME AND COMMUNITY-BASED CARE Teaching Patients Self-Care In helping patients learn about and prevent or manage a recurrent UTI, the nurse needs to implement teaching that meets individual patient needs. For a detailed discussion of patient teaching interventions, see Chart 45-4. Evaluation EXPECTED PATIENT OUTCOMES Expected patient outcomes may include: 1. Experiences relief of pain a. Reports absence of pain, urgency, dysuria, or hesitancy on voiding b. Takes analgesic and antibiotic agents as prescribed 2. Explains UTIs and their treatment a. Demonstrates knowledge of preventive measures and prescribed treatments b. Drinks 8 to 10 glasses of fluids daily c. Voids every 2 to 3 hours d. Voids urine that is clear and odorless 3. Experiences no complications a. Reports no symptoms of infection (fever, dysuria, frequency) or renal failure (nausea, vomiting, fatigue, pruritus) b. Has normal BUN and serum creatinine levels, negative urine and blood cultures c. Exhibits normal vital signs and temperature; no signs or symptoms of sepsis d. Maintains adequate urine output more than 30 mL per

hour.

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- Drug Class Ics LabaDocument25 pagesDrug Class Ics LabaStephanie Louisse Gallega HisolePas encore d'évaluation

- Review HDocument62 pagesReview HStephanie Louisse Gallega HisolePas encore d'évaluation

- Efficacy Safety Suitability Cost-EffectivenessDocument30 pagesEfficacy Safety Suitability Cost-EffectivenessStephanie Louisse Gallega HisolePas encore d'évaluation

- MSE FormDocument3 pagesMSE FormStephanie Louisse Gallega HisolePas encore d'évaluation

- Physical Examination Overview: StephylococcusDocument2 pagesPhysical Examination Overview: StephylococcusStephanie Louisse Gallega HisolePas encore d'évaluation

- Date and Time of AssessmentDocument2 pagesDate and Time of AssessmentStephanie Louisse Gallega HisolePas encore d'évaluation

- I. Review of Systems A) General Health SurveyDocument3 pagesI. Review of Systems A) General Health SurveyStephanie Louisse Gallega HisolePas encore d'évaluation

- Chapter 19 Pediatric Diseases and DisordersDocument5 pagesChapter 19 Pediatric Diseases and DisordersStephanie Louisse Gallega HisolePas encore d'évaluation

- Developmental TablesssDocument1 pageDevelopmental TablesssStephanie Louisse Gallega HisolePas encore d'évaluation

- Ineffective Tissue PerfusionDocument3 pagesIneffective Tissue PerfusionStephanie Louisse Gallega Hisole100% (2)

- B. Lateral Rectus Muscle of The EyeDocument1 pageB. Lateral Rectus Muscle of The EyeStephanie Louisse Gallega HisolePas encore d'évaluation

- Bed Making - ScriptDocument6 pagesBed Making - ScriptStephanie Louisse Gallega Hisole100% (2)

- LaboratoryDocument1 pageLaboratoryStephanie Louisse Gallega HisolePas encore d'évaluation

- Caring For The Pregnant Woman With NeurofibromatosisDocument1 pageCaring For The Pregnant Woman With NeurofibromatosisStephanie Louisse Gallega HisolePas encore d'évaluation

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (400)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (588)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (895)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (266)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (345)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)

- PMLS Lesson 5Document7 pagesPMLS Lesson 5Althea EspirituPas encore d'évaluation

- Laparoscopic Course: General Principles of Laparoscopy: Specific Aspects of Transperitoneal Access (R.Bollens)Document4 pagesLaparoscopic Course: General Principles of Laparoscopy: Specific Aspects of Transperitoneal Access (R.Bollens)Anuj MisraPas encore d'évaluation

- English Informative EssayDocument1 pageEnglish Informative EssayPaul Christian G. SegumpanPas encore d'évaluation

- Nur 601 - Literature Review Manuscript-Icd-10-Sunny Carrington-HahnDocument22 pagesNur 601 - Literature Review Manuscript-Icd-10-Sunny Carrington-Hahnapi-357138638Pas encore d'évaluation

- ApendikDocument4 pagesApendikSepti AyaPas encore d'évaluation

- Unstable Angina - Cardiovascular Disorders - MSD Manual Professional EditionDocument1 pageUnstable Angina - Cardiovascular Disorders - MSD Manual Professional EditionboynextdoorpkyPas encore d'évaluation

- Infusion PumpDocument14 pagesInfusion PumpSREEDEVI T SURESHPas encore d'évaluation

- Medical Biotechnology Multiple Choice Question (GuruKpo)Document13 pagesMedical Biotechnology Multiple Choice Question (GuruKpo)GuruKPO91% (11)

- Using Pediatric Pain Scales Neonatal Infant Pain Scale (NIPSDocument2 pagesUsing Pediatric Pain Scales Neonatal Infant Pain Scale (NIPSSevina Eka ChannelPas encore d'évaluation

- Parameters of The Model: Name Live Alpha Beta DescriptionDocument5 pagesParameters of The Model: Name Live Alpha Beta DescriptionAngga Prawira KautsarPas encore d'évaluation

- The Role of Radiotherapy in Cancer TreatmentDocument9 pagesThe Role of Radiotherapy in Cancer TreatmentarakbaePas encore d'évaluation

- Unit 0000 Topik 9. Word Formation: Nouns: Bold) To Nouns. Do Not Change TheDocument5 pagesUnit 0000 Topik 9. Word Formation: Nouns: Bold) To Nouns. Do Not Change TheioakasPas encore d'évaluation

- 2020 Anaphylaxis JACI 2020Document42 pages2020 Anaphylaxis JACI 2020Peter Albeiro Falla CortesPas encore d'évaluation

- Tercera SemanaDocument9 pagesTercera SemanaJesús Torres MayaPas encore d'évaluation

- Manual of Bone Densitometry Measurements - An Aid To The Interpretation of Bone Densitometry Measurements in A Clinical Setting PDFDocument229 pagesManual of Bone Densitometry Measurements - An Aid To The Interpretation of Bone Densitometry Measurements in A Clinical Setting PDFsesjrsPas encore d'évaluation

- Emergency Anaesthetic Management To Extensive Thoracic Trauma-Hossam AtefDocument60 pagesEmergency Anaesthetic Management To Extensive Thoracic Trauma-Hossam AtefHossam atefPas encore d'évaluation

- Mandibulasr Truma ManagementDocument18 pagesMandibulasr Truma Managementjoal510Pas encore d'évaluation

- Case StudyDocument3 pagesCase StudyLouel VicitacionPas encore d'évaluation

- Kleptomania Term PaperDocument6 pagesKleptomania Term Paperbctfnerif100% (1)

- Complications of Insulin TherapyDocument16 pagesComplications of Insulin TherapyIngrid NicolasPas encore d'évaluation

- SeizureDocument10 pagesSeizureRomeo ReyesPas encore d'évaluation

- Parasitology: - IntroductionDocument62 pagesParasitology: - IntroductionHana AliPas encore d'évaluation

- Diabetic Nephropathy BaruDocument24 pagesDiabetic Nephropathy BaruRobiyanti Nur Chalifah HattaPas encore d'évaluation

- Concept Map PTBDocument1 pageConcept Map PTBJoan Abardo100% (2)

- +++A Short Survey in Application of Ordinary Differential Equations On Cancer ResearchDocument5 pages+++A Short Survey in Application of Ordinary Differential Equations On Cancer ResearchEnes ÇakmakPas encore d'évaluation

- HEDING (M-LE-27) : Crane's SummitDocument1 pageHEDING (M-LE-27) : Crane's SummitSilvaPas encore d'évaluation

- All About Rabies Health ScienceDocument28 pagesAll About Rabies Health SciencetototoPas encore d'évaluation

- Daftar Jurnal Kedokteran Internasional GratisDocument3 pagesDaftar Jurnal Kedokteran Internasional GratisdoktermutiaPas encore d'évaluation

- Sports DrinksDocument2 pagesSports DrinksMustofaPas encore d'évaluation

- Anatomy and Physiology - Dengue FeverDocument3 pagesAnatomy and Physiology - Dengue Feverhael yam62% (13)