Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Case Digest

Transféré par

Clint M. MaratasCopyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Case Digest

Transféré par

Clint M. MaratasDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

CASE DIGEST: NEGOTIABLE INSTRUMENTS LAW PHILIPPINE NATIONAL BANK VS. COURT OF APPEALS GR. NO.

107508 April 25, 1996 1st Division Kapunan FACTS: Ministry of Education Culture issued a check payable to Abante Marketing and drawn against Philippine National Bank (PNB). Abante Marketing, deposited the questioned check in its savings account with Capitol City Development Bank (CAPITOL). In turn, Capitol deposited the same in its account with the Philippine Bank of Communications (PBCom) which, in turn, sent the check to PNB for clearing. PNB cleared the check as good and thereafter, PBCom credited Capitol's account for the amount stated in the check. However, PNB returned the check to PBCom and debited PBCom's account for the amount covered by the check, the reason being that there was a "material alteration" of the check number. PBCom, as collecting agent of Capitol, then proceeded to debit the latter's account for the same amount, and subsequently, sent the check back to petitioner. PNB, however, returned the check to PBCom. On the other hand, Capitol could not in turn, debit Abante Marketing's account since the latter had already withdrawn the amount of the check. Capitol sought clarification from PBCom and demanded the re-crediting of the amount. PBCom followed suit by requesting an explanation and recrediting from PNB. Since the demands of Capitol were not heeded, it filed a civil suit against PBCom which in turn, filed a third-party complaint against PNB for reimbursement/indemnity with respect to the claims of Capitol. PNB, on its part, filed a fourth-party complaint against Abante Marketing. The Trial Court rendered its decision, ordering PBCom to re-credit or reimburse; PNB to reimburse and indemnify PBCom for whatever amount PBCom pays to Capitol; Abante Marketing to reimburse and indemnify PNB for whatever amount PNB pays to PBCom. The court dismissed the counterclaims of PBCom and PNB. The appellate court modified the appealed judgment by ordering PNB to honor the check. After the check shall have been honored by PNB, the court ordered PBCom to re-credit Capitol's account with it the amount. PNB filed the petition for review on certiorari averring that under Section 125 of the NIL, any change that alters the effect of the instrument is a material alteration. ISSUE: WON an alteration of the serial number of a check is a material alteration under the NIL. HELD: NO, alteration of a serial number of a check is not a material alteration contemplated under Sec. 125 of the NIL. RATIO: An alteration is said to be material if it alters the effect of the instrument. It means an unauthorized change in an instrument that purports to modify in any respect the obligation of a party or an unauthorized addition of words or numbers or other change to an incomplete instrument relating to the obligation of a party. In other words, a material alteration is one which changes the items which are required to be stated under Section 1 of the Negotiable Instruments Law. In the present case what was altered is the serial number of the check in question, an item which is not an essential requisite for negotiability under Section 1 of the Negotiable Instruments Law. The aforementioned alteration did not change the relations between the parties. The name of the drawer and the drawee were not altered. The intended payee was the same. The sum of money due to the

payee remained the same. The check's serial number is not the sole indication of its origin. The name of the government agency which issued the subject check was prominently printed therein. The check's issuer was therefore insufficiently identified, rendering the referral to the serial number redundant and inconsequential.

PNB CREDIT CARD CORPORATION v. MATILDE M. RODRIGUEZ 500 SCRA 576 (2006), THIRD DIVISION Allegedly failing to settle her account arising from her availment of her PNB Credit Card to which she charged her purchases inclusive of interest and penalty, PNB Credit Card Corporation filed a complaint before the Regional Trial Court (RTC) of Makati against Matilde M. Rodriguez (Matilde), together with Lorenzo Y. Villalon (Villalon), her co-obligor. The complaint was subsequently dismissed for lack of interest to prosecute, without prejudice. The records do not show that the Matilde and Villalon were furnished copy of the order. A second order was issued by the trial court which again dismissed the case without prejudice. A Petition for Review on Certiorari was filed by Matilde arguing that the order of dismissal without prejudice did not become final as it could be revived within a reasonable period of time, citing Medrano & Associates v. Roxas & Company. ISSUE: Whether or not the trial courts first or second order dismissing Matildes complaint had become final HELD: The facts and circumstances attendant to Medrano cited by Matilde, wherein the Court held that even assuming that the therein order of dismissal without prejudice had become final, [t]here was no reason why instead of asking plaintiff to refile the case, the case cannot be reopened in the interest of justice, are clearly different from those of the present case. In Medrano, the trial court, by Order of March 5, 1986, motu propio dismissed the case without prejudice for failure to prosecute. On May 5, 1986, the plaintiff filed a motion to set the case for hearing on May 9, 1986. Before that or on May 7, 1986, the plaintiffs counsel received a copy of the March 5, 1986 order of dismissal. Although the March 5, 1986 order of dismissal appears to have become final as plaintiff failed to appeal therefrom or to file a motion for reconsideration within the reglementary period, the reason plaintiff failed to act accordingly appears to be that even before receipt of said notice of the dismissal order he filed a motion to set the case for hearing. He was obviously awaiting action on the same. Nevertheless, the trial court reset the hearing of the case not once but three times. The only logical consequence of these actions is that the trial court effectively reconsidered its order of dismissal dated March 5. In other words, in Medrano, this Court took into account the fact that, among other things, before the plaintiff received a copy of the dismissal without prejudice order, it filed before the trial court a motion to set the case for hearing, which the trial court granted when it set the case for hearing three times, which action of the trial court this Court took to logically mean that the order of dismissal was effectively reconsidered.

METROBANK vs. CABILZO Case Digest

METROBANK vs. CABILZO G.R. No. 154469 December 6, 2006 510 SCRA 259 FACTS: On 12 November 1994, Cabilzo issued a Metrobank Check No. 985988, payable to CASH and postdated on 24 November 1994 in the amount of One Thousand Pesos (P1, 000.00). The check was drawn against Cabilzos Account with Metrobank Pasong Tamo Branch under Current Account No. 618044873-3 and was paid by Cabilzo to a certain Mr. Marquez, as his sales commission. Subsequently, the check was presented to Westmont Bank for payment. Westmont Bank, in turn, indorsed the check to Metrobank for appropriate clearing. After the entries thereon were examined, including the availability of funds and the authenticity of the signature of the drawer, Metrobank cleared the check for encashment in accordance with the Philippine Clearing House Corporation (PCHC) Rules. On 16 November 1994, Cabilzos representative was at Metrobank Pasong Tamo Branch to make some transaction when he was asked by bank personnel if Cabilzo had issued a check in the amount of P91, 000.00 to which the former replied in the negative. On the afternoon of the same date, Cabilzo himself called Metrobank to reiterate that he did not issue a check in the amount of P91, 000.00 and requested that the questioned check be returned to him for verification, to which Metrobank complied. Upon receipt of the check, Cabilzo discovered that Metrobank Check No. 985988 which he issued on 12 November 1994 in the amount of P1, 000.00 was altered to P91, 000.00 and the date 24 November 1994 was changed to 14 November 1994.Hence, Cabilzo demanded that Metrobank re-credit the amount of P91, 000.00 to his account. Metrobank, however, refused reasoning that it has to refer the matter first to its Legal Division for appropriate action. Repeated verbal demands followed but Metrobank still failed to recredit the amount of P91, 000.00 to Cabilzos account On 30 June 1995, Cabilzo, thru counsel, finally sent a letter-demand to Metrobank for the payment of P90, 000.00, after deducting the original value of the check in the amount of P1, 000.00. Such written demand notwithstanding, Metrobank still failed or refused to comply with its obligation. Consequently, Cabilzo instituted a civil action for damages against Metrobank before the RTC of Manila, Branch 13. In his Complaint docketed as Civil Case No. 95-75651, Renato D. Cabilzo v. Metropolitan Bank and Trust Company, Cabilzo prayed that in addition to his claim for reimbursement, actual and moral damages plus costs of the suit be awarded in his favor. ISSUE: Whether equitable estoppel can be appreciated in favor of petitioner HELD: The degree of diligence required of a reasonable man in the exercise of his tasks and the performance of his duties has been faithfully complied with by Cabilzo. In fact, he was wary enough that he filled with asterisks the spaces between and after the amounts, not only those stated in words, but also those in numerical figures, in order to prevent any fraudulent insertion, but unfortunately, the check was still successfully altered, indorsed by the collecting bank, and cleared by the drawee bank, and encashed by the perpetrator of the fraud, to the damage and prejudice of Cabilzo. Metrobank cannot lightly impute that Cabilzo was negligent and is therefore prevented from asserting his rights under the doctrine of equitable estoppel when the facts on record are bare of evidence to support such conclusion. The doctrine of equitable estoppel states that when one of the two innocent persons, each guiltless of any intentional or moral wrong, must suffer a loss, it must be borne by the one whose erroneous conduct, either by omission or commission, was the cause of injury. Metrobanks reliance on this dictum is misplaced. For one, Metrobanks representation that it is an innocent party is flimsy and evidently, misleading. At the same time, Metrobank cannot asseverate that Cabilzo was negligent and this negligence was the proximate cause of the loss in the absence of even a scintilla proof to buttress such claim. Negligence is not presumed but must be proven by the one who alleges it, which petitioner failed to.

CHING vs. NICDAO G.R. No. 141181 April 27, 2007 Facts: Nicdao was charged eleven (11) counts of violation of Batas Pambansa Bilang (BP) 22. MTC found her of guilty of said offenses. RTC affirmed. Nicdao filed an appeal to the Court of Appeals. CA reversed the decision and acquitted accused. Ching is now appealing the civil aspect of the case to the Supreme Court. Ching vigorously argues that notwithstanding respondent Nicdaos acquittal by the CA, the Supreme Court has the jurisdiction and authority to resolve and rule on her civil liability. He anchors his contention on Rule 111, Sec 1B: The criminal action for violation of Batas Pambansa Blg. 22 shall be deemed to necessarily include the corresponding civil action, and no reservation to file such civil action separately shall be allowed or recognized. Moreover, under the above-quoted provision, the criminal action for violation of BP 22 necessarily includes the corresponding civil action, which is the recovery of the amount of the dishonored check representing the civil obligation of the drawer to the payee. Nicdaos defense: Sec 2 of Rule 111 Except in the cases provided for in Section 3 hereof, after the criminal action has been commenced, the civil action which has been reserved cannot be instituted until final judgment in the criminal action. Accdg to her, CAs decision is equivalent to a finding that the facts upon which her civil liability may arise do not exist. The instant petition, which seeks to enforce her civil liability based on the eleven (11) checks, is thus allegedly already barred by the final and executory decision acquitting her. Issue: 1. WON Ching may appeal the civil aspect of the case within the reglementary period? YES 2. WON Nicdao civilly liable? NO. Held: 1. Ching is entitled to appeal the civil aspect of the case within the reglementary period. Every person criminally liable for a felony is also civilly liable. Extinction of the penal action does not carry with it extinction of the civil, unless the extinction proceeds from a declaration in a final judgment that the fact from which the civil might arise did not exist. Petitioner Ching correctly argued that he, as the offended party, may appeal the civil aspect of the case notwithstanding respondent Nicdaos acquittal by the CA. The civil action was impliedly instituted with the criminal action since he did not reserve his right to institute it separately nor did he institute the civil action prior to the criminal action. If the accused is acquitted on reasonable doubt but the court renders judgment on the civil aspect of the criminal case, the prosecution cannot appeal from the judgment of acquittal as it would place the accused in double jeopardy. However, the aggrieved party, the offended party or the accused or both may appeal from the judgment on the civil aspect of the case within the period therefor. GENERAL RULE: Civil liability is not extinguished by acquittal: 1. where the acquittal is based on reasonable doubt; 2. where the court expressly declares that the liability of the accused is not criminal but only civil in nature; and 3. where the civil liability is not derived from or based on the criminal act of which the accused is acquitted. 2. A painstaking review of the case leads to the conclusion that respondent Nicdaos acquittal likewise carried with it the extinction of the action to enforce her civil liability. There is simply no basis to hold respondent Nicdao civilly liable to petitioner Ching. CAs acquittal of respondent Nicdao is not merely based on reasonable doubt. Rather, it is based on the finding that she did not commit the act penalized under BP 22. In particular, the CA found that the

P20,000,000.00 check was a stolen check which was never issued nor delivered by respondent Nicdao to petitioner Ching. CA did not adjudge her to be civilly liable to petitioner Ching. In fact, the CA explicitly stated that she had already fully paid her obligations. The finding relative to the P20,000,000.00 check that it was a stolen check necessarily absolved respondent Nicdao of any civil liability thereon as well. Under the circumstances which have just been discussed lengthily, such acquittal carried with it the extinction of her civil liability as well. Negotiable Instruments; Delivery Posted by attymarkpiad on July 9, 2012 Significantly, delivery is the final act essential to the negotiability of an instrument. Delivery denotes physical transfer of the instrument by the maker or drawer coupled with an intention to convey title to the payee and recognize him as a holder. It means more than handing over to another; it imports such transfer of the instrument to another as to enable the latter to hold it for himself. (John Dy vs. People of the Philippines, et al, G.R. No. 158312, November 14, 2008, [Quisumbing, Acting C.J.]) Note however that delivery as the term is used in the aforementioned provision means that the party delivering did so for the purpose of giving effect thereto. Otherwise, it cannot be said that there has been delivery of the negotiable instrument. Once there is delivery, the person to whom the instrument is delivered gets the title to the instrument completely and irrevocably. (San Miguel Corporation vs. Puzon, G.R. No. 167567, September 22, 2010, [Del Castillo, J.:])

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- Sample Resignation LetterDocument15 pagesSample Resignation LetterJohnson Mallibago71% (7)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (119)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (399)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (587)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5794)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2219)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1090)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (344)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (894)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- Articles of Incorporation and by Laws Non Stock CorporationDocument10 pagesArticles of Incorporation and by Laws Non Stock CorporationClint M. MaratasPas encore d'évaluation

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- 18 - Carvana Is A Bad BoyDocument6 pages18 - Carvana Is A Bad BoyAsishPas encore d'évaluation

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (73)

- Sample Contract of LoanDocument1 pageSample Contract of LoanRhon Gallego-Tupas93% (28)

- Real Estate Mortgage AgreementDocument3 pagesReal Estate Mortgage AgreementClint M. Maratas100% (4)

- Exclusive Distributor Agreement123Document13 pagesExclusive Distributor Agreement123Clint M. Maratas100% (3)

- Exclusive Distributor Agreement123Document13 pagesExclusive Distributor Agreement123Clint M. Maratas100% (3)

- Rahul IAS Notes on Code of Criminal ProcedureDocument310 pagesRahul IAS Notes on Code of Criminal Proceduresam king100% (1)

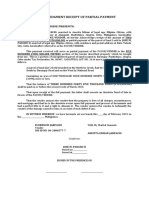

- Acknowledgment Receipt of Partial PaymentDocument2 pagesAcknowledgment Receipt of Partial PaymentClint M. MaratasPas encore d'évaluation

- Chief Affidavit of Petitioner M.v.O.P.222 of 2013Document4 pagesChief Affidavit of Petitioner M.v.O.P.222 of 2013Vemula Venkata PavankumarPas encore d'évaluation

- Compromise Agreement Cebu AccidentDocument3 pagesCompromise Agreement Cebu AccidentClint M. MaratasPas encore d'évaluation

- Deed of Undertaking - Amla Seminar - Legal 3 CopiesDocument1 pageDeed of Undertaking - Amla Seminar - Legal 3 CopiesClint M. Maratas100% (2)

- Creser Precision Systems Vs CA Floro (Week 2)Document1 pageCreser Precision Systems Vs CA Floro (Week 2)Victor LimPas encore d'évaluation

- Share Transfer AgreementDocument4 pagesShare Transfer AgreementClint M. Maratas0% (1)

- Mindanao Island 5.1 (PPT 1) Group 2Document40 pagesMindanao Island 5.1 (PPT 1) Group 2Aldrin Gabriel BahitPas encore d'évaluation

- Special Power of AttorneyDocument5 pagesSpecial Power of AttorneyClint M. MaratasPas encore d'évaluation

- IRR of RA 11934Document12 pagesIRR of RA 11934Red GaddiPas encore d'évaluation

- GuidelinesDocument1 pageGuidelinesClint M. MaratasPas encore d'évaluation

- Daily Package SalesDocument2 pagesDaily Package SalesClint M. MaratasPas encore d'évaluation

- Recommendations For The SystemDocument1 pageRecommendations For The SystemClint M. MaratasPas encore d'évaluation

- Handling ProcessDocument2 pagesHandling ProcessClint M. MaratasPas encore d'évaluation

- LETTER OF INTENT BarangayDocument1 pageLETTER OF INTENT BarangayClint M. MaratasPas encore d'évaluation

- Employee Security Program Pre Approach LetterDocument2 pagesEmployee Security Program Pre Approach LetterClint M. MaratasPas encore d'évaluation

- Gnamma Health MARKETINGoct31Document10 pagesGnamma Health MARKETINGoct31Clint M. MaratasPas encore d'évaluation

- Administrative Procedure LawDocument116 pagesAdministrative Procedure LawnikowawaPas encore d'évaluation

- NAFI Terms and ConditionDocument7 pagesNAFI Terms and ConditionClint M. MaratasPas encore d'évaluation

- Hotels in Cebu: AlcoyDocument53 pagesHotels in Cebu: AlcoyClint M. MaratasPas encore d'évaluation

- BROCHUREclint 2020Document2 pagesBROCHUREclint 2020Clint M. MaratasPas encore d'évaluation

- Gnamma Officers Roles and ResponsibilitiesDocument7 pagesGnamma Officers Roles and ResponsibilitiesClint M. MaratasPas encore d'évaluation

- Christmas PrayerDocument1 pageChristmas PrayerClint M. MaratasPas encore d'évaluation

- Sample Investment Agreement123Document3 pagesSample Investment Agreement123Clint M. MaratasPas encore d'évaluation

- Suggested Telephone Appointment ScriptDocument1 pageSuggested Telephone Appointment ScriptClint M. MaratasPas encore d'évaluation

- Admission RequirementsDocument15 pagesAdmission RequirementsClint M. MaratasPas encore d'évaluation

- VUL Insurance Vs Mutual Fund Vs UITF InvestmentDocument4 pagesVUL Insurance Vs Mutual Fund Vs UITF InvestmentClint M. MaratasPas encore d'évaluation

- TThe Importance of Variable Life InsuranceDocument10 pagesTThe Importance of Variable Life InsuranceClint M. MaratasPas encore d'évaluation

- Cap College GraduatesDocument16 pagesCap College GraduatesClint M. MaratasPas encore d'évaluation

- United States v. Jackie C. Coffey, 415 F.2d 119, 10th Cir. (1969)Document4 pagesUnited States v. Jackie C. Coffey, 415 F.2d 119, 10th Cir. (1969)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- DocsssDocument4 pagesDocsssAnne DesalPas encore d'évaluation

- MELENDEZ Luis Sentencing MemoDocument9 pagesMELENDEZ Luis Sentencing MemoHelen BennettPas encore d'évaluation

- Trilogy Monthly Income Trust PDS 22 July 2015 WEBDocument56 pagesTrilogy Monthly Income Trust PDS 22 July 2015 WEBRoger AllanPas encore d'évaluation

- The Gazzat of PakistanDocument236 pagesThe Gazzat of PakistanFaheem UllahPas encore d'évaluation

- Jei and Tabligh Jamaat Fundamentalisms-Observed PDFDocument54 pagesJei and Tabligh Jamaat Fundamentalisms-Observed PDFAnonymous EFcqzrdPas encore d'évaluation

- Puss in Boots Esl Printable Reading Comprehension Questions Worksheet For KidsDocument2 pagesPuss in Boots Esl Printable Reading Comprehension Questions Worksheet For KidsauraPas encore d'évaluation

- Fdas Quotation SampleDocument1 pageFdas Quotation SampleOliver SabadoPas encore d'évaluation

- Project Report JP MorganDocument41 pagesProject Report JP Morgantaslimr191Pas encore d'évaluation

- Indian Ethos and ManagementDocument131 pagesIndian Ethos and ManagementdollyguptaPas encore d'évaluation

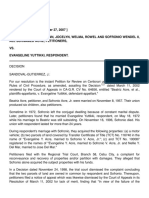

- Acre v. Yuttiki, GR 153029Document3 pagesAcre v. Yuttiki, GR 153029MiguelPas encore d'évaluation

- Notes in Comparative Police System Unit 1 Basic TermsDocument26 pagesNotes in Comparative Police System Unit 1 Basic TermsEarl Jann LaurencioPas encore d'évaluation

- PS (T) 010Document201 pagesPS (T) 010selva rajaPas encore d'évaluation

- Miller Deliveries June transactions analysisDocument7 pagesMiller Deliveries June transactions analysisMD SHAFIN AHMEDPas encore d'évaluation

- Lopez-Wui, Glenda S. 2004. "The Poor On Trial in The Philippine Justice System." Ateneo Law Journal 49 (4) - 1118-41Document25 pagesLopez-Wui, Glenda S. 2004. "The Poor On Trial in The Philippine Justice System." Ateneo Law Journal 49 (4) - 1118-41Dan JethroPas encore d'évaluation

- RTO Question Bank EnglishDocument107 pagesRTO Question Bank EnglishRavi KumarPas encore d'évaluation

- Postgraduate Application Form UPDATEDDocument4 pagesPostgraduate Application Form UPDATEDNYANGWESO KEVINPas encore d'évaluation

- Sap S/4Hana: Frequently Asked Questions (Faqs)Document6 pagesSap S/4Hana: Frequently Asked Questions (Faqs)kcvaka123Pas encore d'évaluation

- Drug Free Workplace Act PolicyDocument8 pagesDrug Free Workplace Act PolicyglitchygachapandaPas encore d'évaluation

- It FormDocument13 pagesIt FormMani Vannan JPas encore d'évaluation

- SEMESTER-VIDocument15 pagesSEMESTER-VIshivam_2607Pas encore d'évaluation

- Accounting Calling ListDocument4 pagesAccounting Calling Listsatendra singhPas encore d'évaluation

- Trinity College - Academic Calendar - 2009-2010Document3 pagesTrinity College - Academic Calendar - 2009-2010roman_danPas encore d'évaluation

- RP-new Light DistrictsDocument16 pagesRP-new Light DistrictsShruti VermaPas encore d'évaluation