Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

English Policy

Transféré par

Ryan Bustillo0 évaluation0% ont trouvé ce document utile (0 vote)

147 vues18 pagesBsed14

Copyright

© Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Formats disponibles

PDF, TXT ou lisez en ligne sur Scribd

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentBsed14

Droits d'auteur :

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Formats disponibles

Téléchargez comme PDF, TXT ou lisez en ligne sur Scribd

0 évaluation0% ont trouvé ce document utile (0 vote)

147 vues18 pagesEnglish Policy

Transféré par

Ryan BustilloBsed14

Droits d'auteur :

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Formats disponibles

Téléchargez comme PDF, TXT ou lisez en ligne sur Scribd

Vous êtes sur la page 1sur 18

chapter 11

Difusion and directions

English language policy in the Philippines

Isabel Pefanco Martin

Ateneo de Manila University, Te Philippines

Tis chapter presents the English language from the viewpoint of language policy.

English was frst introduced to the Filipinos through the American public school

system and, for half a century, the language was systematically promoted as a

civilizing tool. Today, beliefs and attitudes about English, as well as the various

ways in which the language is used, may be traced to the Filipino experience

of American colonial education. A brief survey of the English language policy

situation in the Philippines from the American colonial period to contemporary

times reveals difusions in language policy formulation. Such difusion has

resulted in conficting policies and practices that marginalize Philippine languages

and contribute to the further deterioration of education among Filipino children.

Keywords: language policy and planning, bilingual education, national language,

English as the medium of instruction

1. Te language policy of the American colonial period

In 1928, an American schoolteacher in the Philippines reported that his students com-

positions had the indelible impression of Henry Wadsworth Longfellows romantic

poem Evangeline. Te teacher noted that in these compositions

One nipa shack had acquired dormer windows with gables projecting and was

surrounded by primeval mangoes and acacia.

1

A mere tuba gatherer had a face

which shone with celestial brightness as if he ambled home with his fagons of

home-brewed tuba.

2

Every fair maiden in the class was endowed with eyes as

black as the berry that grows on the thorn by the wayside as she strode to church

with her chaplet of beads and missal, this last word usually being spelled missle.

(Annex Teacher 1928: 7)

1. A nipa shack is a house with leaves similar to coconut tree leaves as roof.

2. Tuba is coconut wine.

:o Isabel Pefanco Martin

What this American teacher had observed is a prequel to the cultural cloning of the

Filipinos. Decades afer the 1946 Philippine independence from the United States,

Filipinos continue to behave like so-called brown Americans. What specifc strate-

gies did the American colonizers use to create this brown American? Te answer

may be found in the language policy imposed by the colonial educators.

On 13 August 1898, a few months before American forces ofcially occupied

Manila, American soldiers had already begun to teach in Corregidor (Estioko

1994: 186). It is assumed that their frst lesson was English. It was no accident that the

frst English teachers in the Philippines were American soldiers. Public education was

introduced as an essential component of military strategy. General Arthur MacArthur

himself declared the following about public education:

Te matter [public education] is so closely allied to the exercise of military force

in these islands that in my annual report I treated the matter as a military subject

and suggested a rapid extension of educational facilities as an exclusively military

measure. (UNESCO-Philippine Educational Foundation 1953: 74)

Troughout the American colonial period, English was systematically promoted as the

language that would civilize the Filipinos. Te aim was to systematically confne the

native languages to outside the territories of schooling. Te policy was institutional-

ized through the heavy use of instructional materials of Anglo-American origin for

language instruction. Troughout four decades of American public education, Filipino

students were exposed to a canon of literature that included works of Henry Wads-

worth Longfellow, Washington Irving, Ralph Waldo Emerson, as well as those of

Shakespeare, George Elliott, Matthew Arnold, and the romantic poets. Meanwhile,

Filipinos were using their own language outside the schools.

When the Americans arrived in the Philippines in 1898, the Filipinos already had a

fourishing literature. In the frst decade of American occupation, with memories of the

revolution against Spain still fresh, secular values spread rapidly as a rejection of 300 years

of religious domination. Spanish declined but English had not yet gained a foothold. Tus,

the foodgates of literature in the native languages were fung wide open. With a new-

found freedom of expression under the American colonizers, poetry, fction, and journal-

ism in the Philippine languages fourished. However, this wealth of writing by Filipinos

did little to promote the recognition of Philippine literature in the colonial classroom.

In 1925, a comprehensive study of the educational system of the Philippines (also

known as the 1925 Monroe Report) reported that Filipino students had no opportu-

nity to study in their native language. Te report recommended that the native language

be used as an auxiliary medium of instruction in courses such as character education,

and good manners and right conduct (Board of Educational Survey 1925: 40). Still,

American education ofcials insisted on the exclusive use of English in the public

schools until 1940. Te policy propelled the English language towards becoming, in

the words of Renato Constantino, a ...wedge that separated the Filipinos from their

past (Constantino 1982: 12).

Chapter 11. Difusion and directions ::

Language policy and planning during American colonial rule were geared to-

wards education and the civil service but [...] not guided by explicit language laws or

agencies (Gonzales 2003: 2). It was only in 1937, when the National Language Insti-

tute was established under the Romualdez Law, that the colonial government began to

formulate a language policy. Tis policy had to do with the establishment of a national

language.

In 1939, afer some years of heated debates about the matter, Tagalog was ofcially

proclaimed as the national language. Soon, the language was taught as a subject in

schools. In 1943 to 1945, Tagalog was recognized by the Japanese-controlled Philippine

government which insisted on the rapid dissemination of the language throughout the

countrys educational institutions. During this period, specifcally in 1942, the nation-

al language was recognized as one of the ofcial languages of the country (together

with Japanese) by virtue of a military ordinance of the Commander-in-Chief of the

Imperial Japanese Forces (Bautista 1996; Gonzales 1998).

2. Post-colonial language policy

Except for the brief period of Japanese occupation, English was maintained as the

dominant language of government and education in the Philippines. Te identifcation

of a national language in the latter part of American colonial rule did not afect the

elevated status of English in the Philippine society.

Political independence from the United States, granted in 1946, saw the continued

spread of the national language as a subject that was taught at the basic education lev-

els, while English was maintained as the medium of instruction. In 1959, the national

language was renamed Pilipino. In 1987, shortly afer the People Power Revolution,

the language was renamed again, this time, to Filipino. Te renaming was an attempt

to promote the national language as one that was not biased towards Tagalog, but in-

stead, refective of the multicultural and multilingual context of the Philippines.

In the 1950s, visiting linguist Cliford Prator conducted studies in the Philippines

resulting in the implementation of the Vernacular Teaching Policy of 1957. Tis policy

prescribed the use of the major vernacular languages as languages of initial teaching

and literacy until Grade 3, with Tagalog and English taught as separate subjects.

Still, English was maintained as the medium of instruction from Grade 3 onwards

(Gonzales 1998).

Despite the continued dominance of English in the domains of education, govern-

ment, and business, there is no formal language-planning agency that sets directions

for this language. Linguist and former Education Secretary Andrew Gonzales believes

that in the Philippines, language planning is not under one unifed agency but is dif-

fused and located in diferent agencies according to the nature of the task to be accom-

plished (Gonzales 1998: 511). Until the 1990s, only one law and one department order

ensured the maintenance of English as one of the two ofcial languages of the country.

:i Isabel Pefanco Martin

Te 1987 Philippine Constitution states that for purposes of communication and in-

struction, the ofcial languages of the Philippines are Filipino and, until otherwise

provided by law, English. Tis law is carried out through DECS Order No. 52 series

1987, also known as the Bilingual Education Policy (henceforth BEP) of the Depart-

ment of Education (henceforth DepEd), which was frst introduced in 1974 and then

re-issued with minor modifcations in 1987. Te BEP aims to develop bilingual Filipi-

nos competent in both English and the national language. Tis BEP is the recognized

language-in-education policy that is still in place today in the education sector.

At present, there are many government agencies with stakes in language planning

in the Philippines. Te Commission on the Filipino Language (Komisyon sa Wikang

Filipino or KWF), which was founded in 1991, is the language-planning agency for the

national language and other Philippine languages. Since its founding, the KWF has not

been genuinely successful in enriching the national language, let alone contributing to

its wide acceptability as a language of instruction. Promoting the national language in

the Philippines remains a highly controversial and emotionally charged task, especially

when the issue of the language of learning comes into play. Gonzales (1998: 515) notes,

Until the mastery of Filipino becomes more necessary for livelihood than for sym-

bolic purposes, based on previous Philippine experience, the widespread use of

Filipino as a language of instruction especially for science and technology at the

higher level of schooling will be limited. (Gonzales 1998: 515)

Two government agencies direct education in the country, namely, the DepEd and the

Commission on Higher Education (henceforth CHED). Both are bound by the 1987

BEP, with the DepEd focusing on basic education and the CHED on tertiary-level edu-

cation. And then there is another agency that advises the Philippine President about

education policy matters. Te Presidential Task Force on Education was created in 2007

through Executive Order (henceforth EO) 635 to assess, plan, and monitor the entire

educational system (Villafania 2007). Tis task force has been at the centre of recent

language-in-education debates afer Presidential Adviser for Education Mona Valisno

reported that President Gloria Arroyo had agreed to the use of the lingua franca or

vernacular for grade one, but emphasized the need to intensify eforts of all concerned

to make the pupils learn more English, math and science (Nolasco 2008: 142).

One set of government agencies with stakes in language planning in the Philippines

are those agencies that have to do with trade and industry. Te exporting of Filipino

labour, also known as Overseas Filipino Workers (henceforth OFW), is believed to be

the single most signifcant force in promoting a high demand for English in Philippine

society. Gonzales writes:

Indirectly, since OFWs are hired largely because of their familiarity with English

and their technical skills, their infuence is considerable for the maintenance of

the English language and its continuing use in the specialised domains of seaman-

ship, the health sciences, technology, and management. (Gonzales 1998: 515)

Chapter 11. Difusion and directions :

Tis reality is evident in the following Employers Guide posting about the advantage

of hiring Filipino nurses:

Te facility in expressing himself/herself in English gives the Filipino nurse the

extra advantage. With a good command of the language, he/she is able to commu-

nicate efectively with his/her employer, co-workers, and most importantly, with

his/her patient or ward. (Philippine Overseas Employment Administration 2005)

Te Information Communications Technology (henceforth ICT) industry is also one

sector that has contributed to maintaining the elevated status of English in the country.

In the last decade, the call centre industry in the Philippines has been receiving a lot of

support from the government in an attempt to attract investors into the country. Soon

afer President Arroyo assumed the presidency, she called for structural reforms, which

included the creation of a telecommunications infrastructure to attract more ICT in-

vestments. In her 2001 State of the Nation Address (henceforth SONA), Arroyo, an

economist by profession, promised the following:

We will promote fast-growing industries where high-value jobs are most plentiful.

One of them is information and communications technology, or ICT. Our English

literacy, our aptitude and skills give us a competitive edge in ICT. (Arroyo 2001)

On 17 May 2003, President Arroyo issued EO No. 210, which aimed to establish a

policy to strengthen the use of English as a medium of instruction because of the

... need to develop the aptitude, competence and profciency of our students in

the English language to maintain and improve their competitive edge in emerg-

ing and fast-growing local and international industries, particularly in the area of

Information and Communications Technology. (Arroyo 2003)

In her 2006 SONA, Arroyo claimed success in the structural reforms her government

had implemented. She described having cofee with a call centre agent as a touching

experience:

I had cofee with some call center agents last Labor Day. Lyn, a new college graduate,

told me, Now I dont have to leave the country in order for me to help my family.

Salamat po. (Tank you.) I was so touched, Lyn, by your comments. With struc-

tural reforms, we not only found jobs, but kept families intact. (Arroyo 2006)

Arroyos 2007 SONA had a more boastful tone when she declared that the Philippines

ranks among top of-shoring hubs in the world because of cost competitiveness and

more importantly our highly trainable, English profcient, IT-enabled management

and manpower (Arroyo 2007).

However, there is a widespread perception that English language profciency

among the Filipinos is deteriorating. Robert S. Keitel, Regional Employment Advisor

of the United States Embassy in Manila, reports that only four percent of Filipino ap-

plicants are hired by call centres while the remaining ninety-six percent were not

:| Isabel Pefanco Martin

because of their sub-standard English skills (Keitel 2008), this, despite 400,000 grad-

uates being produced every year. Keitel (2008) notes the mismatch between the call

centres expectations of applicants and the preparedness of graduates from Philippine

HEIs, thus forcing call centres to collaborate closely with colleges and universities

higher education institutions or HEIs. Keitel writes:

It has been an evolution for academe to recognize that call center employment is

an appropriate career opportunity for their graduates. Such recognition has neces-

sitated changes in the curriculum. Initially, one reaction was, we speak English al-

ready... are we not one of the largest English speaking countries in the world? Yes,

Filipinos speak English but it is a variety called Filipino English, and it is not the

international (global) English required for call center employment. (Keitel 2008)

Like Keitel, American businessman Russ Sandlin, in a letter to a national daily, pres-

ents a less than rosy picture of the call centre industry in the Philippines. Sandlin

writes:

I closed my call center here. Filipinos have much worse English than their Indian

counterparts. Not even three percent of the students who graduate college are

employable in call centers. Trust me; all of us are leaving for China.

... Te Philippines has a terrible talent shortage, and the government and the press

are in denial... English is the only thing that can save the country, and no one here

cares or even understands that the Filipinos have a crisis...God save the Philip-

pines. I hate to see the country falling ever deeper into an English-deprived abyss.

(Sandlin 2008)

Tis English-deprived abyss is indeed what the Philippine government is desperately

attempting to prevent, sadly at the expense of the more basic needs of the Filipinos.

Te Philippine governments formula for economic success has become painfully sim-

plistic: English equals money. Whether Filipino graduates are capable of critical and

creative thinking, or have acquired basic life skills other than language skills, does not

seem to be a major concern. Te Philippine governments language policies seem to be

fxated on English alone.

To be sure, a good command of English is benefcial in employment situations

where the language is used. However, language profciency alone may not ensure eco-

nomic success. As the language is not equally accessible to Filipinos, an over-emphasis

on English profciency because of the proliferation of call centres and medical tran-

scription agencies in the Philippines, as well as increasing demands for Filipino work-

ers abroad, may push schools to propagate the illusion that only profciency in English

guarantees economic success.

Te policy of the Philippine government on the use of English and Filipino is

aptly described by Gonzales (1998: 515) as the product of a compromise solution to

the demands of nationalism and internationalism. On the one hand, advocates of na-

tionalism push for the establishment, spread, and maintenance of Filipino, the national

Chapter 11. Difusion and directions :,

language. Ten there are those who support the continued dominance of English in

important domains in Philippine society. Tese pro-English advocates promote the

language as the countrys main defence against economic doom.

In 2003, at the 75th founding anniversary of a Manila university, President Arroyo

made the following statement that set of a series of reactions among language stake-

holders:

Our English literacy, our aptitude and skills give us a competitive edge in ICT

(information and communications technology)...Terefore, until Congress enacts

a law mandating Filipino as the language of instruction, I am directing the De-

partment of Education to return English as the primary medium of instruction,

provided some subjects will still be taught in Filipino. (Pazzibugan 2003)

Although the statement did not depart from the BEP, language stakeholders regarded it

as an afront to the promotion of Filipino, the national language. A few months later, EO

No. 210, entitled Establishing the Policy to Strengthen the Use of the English Language

as a Medium of Instruction in the Educational System, was issued, followed by DepEd

Order No. 36, which detailed the implementing rules and regulations for EO 210. A

group of language stakeholders, Wika ng Kultura at Agham Incorporated (henceforth

WIKA, meaning in English Language of Culture and Science Incorporated), chal-

lenged EO 210 and DepEd Order 36 by petitioning the Supreme Court to declare the

orders unconstitutional. In its petition, WIKA claims that EO 210 subverts the present

status of Filipino in non-Tagalog areas, and violates the constitutional injunction that

the regional languages shall serve as auxiliary media of instruction (Torres 2007).

Te petition betrays a myth about languages in the Philippines that the English

language is in direct opposition to the national language. Ofen, when stakeholders of

the national language are confronted with attempts to institutionalize English in the

education domain, they cite nationalism, or the lack of it, as a reason for resisting

English. Tis defensive stance towards the national language may be symptomatic of

the inability of the Philippine government to efectively promote the use of Filipino in

important domains in Philippine society. Gonzales (1996: 236) notes that a deterrent

to the full fowering of a national code would be competing policies of government

caused by special economic situations; hence, language ambivalence becomes the rea-

son or manifestation of economic and social forces present outside the language.

Tupas (2007: 75) describes this situation as propagating a simplistic dichotomy

between instrumentalist and identity positions in the language debate in the Philip-

pines. He writes that the framework of the language debates in the Philippines contin-

ues to be:

... not only simplistic in the sense that it marginalizes important dimensions of the

debate, it also fails to capture the underlying social tensions and fssures which are

themselves constitutive of the complex dynamics of power relations in the Philip-

pines. (Tupas 2007: 75)

:o Isabel Pefanco Martin

An unfortunate casualty of difusions in language policy and planning in the Philip-

pines is the basic education sector.

3. Philippine basic education in the periphery

In the 2008 Education for All Global Monitoring Report, United Nations Educational,

Scientifc and Cultural Organization or UNESCO describes the Philippines as having

performed dismally in the 2003 Trends in International Mathematics and Science

Study or TIMSS, when Grade 4 students came out third to last in both Maths and

Science tests. In addition, the Philippines ranked 41st in Maths and 42nd in Science

(out of forty-six participating countries) at the second year high school level

(Caoili-Rodriguez 2007: 13). It was noted in this report that the low scores in Maths

and Science prompted the government to re-evaluate science and math education in

the country and implement remedial actions such as intensifed teacher trainings.

(Caoili-Rodriguez 2007: 13)

In addition to international measures of profciency, there is also a national assess-

ment of the competencies of students in the elementary and high school levels that the

DepEd administers every year. Te National Achievement Tests, also known as NAT,

have been posting disappointing results over the last six years in Maths, Science, and

English (Department of Education 2008b). Te tables below illustrate this point.

Te NAT results for the elementary and high school levels reveal that the mean

percentage scores in Maths, Science, and English since 2003 have not exceeded 65% at

Table 1. NAT elementary school results

School Year Maths Science English

SY 200304 59.45 52.59 49.92

SY 200405 59.10 54.12 59.15

SY 200506 53.66 46.77 54.05

SY 200607 60.29 51.58 60.78

SY 200708 63.89 57.90 61.62

Table 2. NAT high school results

School Year Maths Science English

SY 200304 46.20 36.80 50.08

SY 200405 50.70 39.50 51.30

SY 200506 47.82 37.98 47.73

SY 200607 39.00 41.99 51.78

SY 200708 42.85 46.71 53.46

Chapter 11. Difusion and directions :

the elementary level and 53% at the high school level. Te DepEd identifes the mas-

tery level as being 75% and above. Following this rubric then, one may conclude that

Filipino students have not achieved mastery of Maths, Science, and English (National

Statistical Coordination Board 2007).

In 2008, Education Secretary Jesli Lapus launched the DepEds fagship pro-

gramme known as Project Turning around Low Performance in English (henceforth

TURN). Lapus explains that the project recognizes the importance of English prof-

ciency as an important building block in learning (Department of Education 2008a).

Lapus notes that English profciency is critical in learning as other key subjects such

as Science and Mathematics use English in textbooks and other reference materials

(Department of Education 2008a).

Project TURN was launched through DepEd Order 7, which required all teachers

of English, Maths, and Science in low-performing elementary and high schools to take

an English Profciency test and be trained in oral and written communication in Eng-

lish. Php 500 million (roughly USD 11 million) was earmarked for the in-service

English retooling of public school teachers (Martel 2008).

Tese government interventions illustrate the prevalence of the illusion that Eng-

lish is the cure to the students low achievement scores that English is the only lan-

guage through which knowledge, especially of maths and science, can be accessed.

Tis is further reinforced by persistent attempts by lawmakers to pass laws to institu-

tionalize the sole use of English as the medium of instruction. Cebu Representative

Eduardo Gullas was successful in getting 205 co-authors for House Bill 305 (the Gullas

Bill), or An Act to Strengthen and Enhance the Use of English as the Medium of In-

struction in Philippine Schools (Sunstar Cebu 2008). Gullas claims that the bill:

... aims to correct the defects of the current bilingual education program of the

Department of Education. Its ultimate objective is the improvement of the learn-

ing process in schools to ensure quality outputs. (Te Manila Times 2007)

Te BEP has been widely criticized for many reasons, one being the perception that it

does not contribute to upgrading the students mastery of language and content areas.

Te KWF believes that the BEP must be reviewed and revised. Ricardo Nolasco, for-

mer Chair of the KWF, in pushing for laws that support mother-tongue literacy, writes

about a basic weakness (that) is plaguing Philippine education (Nolasco 2008: 133).

He is referring to the mismatch between the students frst languages and the languag-

es of schooling, which are English and Filipino. Nolasco presents the following facts

about the Philippine language situation (Nolasco 2008: 134):

Te Philippines is a multilingual nation with more than 170 languages.

According to the 2000 Philippine census, the fve biggest Philippine languages

based on the number of frst language speakers are Tagalog (21.5 million),

Cebuano (18.5 million), Ilocano (7.7 million), Hiligaynon (6.9 million), and Bicol

(4.5 million).

:8 Isabel Pefanco Martin

Te 2000 Philippine census also reveals that 65 million out of 76 million Filipinos

are able to speak the national language as a frst or second language.

Tese facts, in addition to studies done on the efects of the BEP, demonstrate that

Filipino school children may be marginalized by a policy that promotes languages that

are not their own. Tere are lawmakers who are aware of this reality, as evident in the

fling of House Bill 3719 by Valenzuela Congressman Magtanggol Gunigundo. Known

as the Multilingual and Literacy Act of 2008, the Gunigundo Bill aims to ...upgrade

the literacy program of the government by making the native tongue as the medium of

instruction for the formative years of basic education (14th Congress of the Republic

of the Philippines 2008).

Some sectors of the government, particularly those in the executive branch, are

also cognizant of the marginalization of the schoolchildrens frst languages. Te chair-

man of the National Economic Development Authority or NEDA and Socioeconomic

Planning Secretary Ralph Recto, in a letter to Executive Secretary Eduardo Ermita,

endorsed the Gunigundo Bill and explains that it is:

... consistent with the goals of the Philippine Education for All (EFA) 2015 Plan

and the Updated Medium-Term Philippine Development Plan (MTPDP) 2004

2010, which supports the utilization of the mother tongue as a fundamental tool

to enhance the learning process itself and improve the relevance of basic educa-

tion. (Personal communication, 12 August 2008)

Te DepEd has also begun to accept the long-term benefts of mother-tongue literacy,

which the department believes does not run counter to the spirit of the BEP. Te

DepEd has recently partnered with universities and associations in training primary

school teachers on the use of the mother language as a medium of instruction. Tis

training programme is presented as an extension of the 1999 Lingua Franca Education

Project that linguist Andrew Gonzales introduced at the DepEd when he was Educa-

tion Secretary (Villafania 2009).

It is unfortunate, however, that President Arroyo remains cold to the issue of

mother-tongue literacy despite the endorsement of the Socioeconomic Planning Sec-

retary and the Education Secretary, both members of her Cabinet. To this day, Arroyo

has not certifed House Bill 3719 as a priority bill of her administration.

In the 1990s, linguist Andrew Gonzalez, who later became Secretary of Education,

refected on the BEP and wrote about his obsession ...to make Filipinos linguistically

competent to be able to think deeply and critically in any language (Gonzalez

1999: 13). Gonzalez appealed for:

... a maximum of fexibility in the media of instruction...Not everything in Philip-

pine education has to be uniform; in fact, even if we have policies towards uni-

formity, we never accomplish enough to be able to attain uniformity of results. So

why not recognize this limitation and exploit it so that we can move faster towards

development? (Gonzalez 1999: 13)

Chapter 11. Difusion and directions :

It is in this spirit of fexibility and resistance to uniformity that Filipino teachers reject

the language purity imposition of the BEP and try to promote code-switching in the

classrooms. Code-switching, despite the policy of English-only in Maths and Science,

may be a form of resistance to prevailing illusions about languages in the Philippines.

Studies on code-switching in the Philippines reveal that it is practiced in various

domains, by diferent groups, for diferent reasons (Martin 2006). Still, that code-

switching is natural, inevitable, and perhaps necessary in Philippine education remains

a touchy issue, especially where content learning is concerned. Two research studies

that support resistance to English-only in education are Allan Bernardos cognitive

science experiments about the efects of language on mathematical learning and per-

formance and Isabel Pefanco Martins study of code-switching among teachers and

students in Science courses.

Bernardo (2000) investigated the efect of using the Filipino students frst or sec-

ond language on their mathematical problem solving ability. He concludes that there

is no single efect of language on mathematical ability. Instead, the language efects are

multifarious and specifc to the diferent components of mathematic problem solv-

ing (Bernardo 2000: 310). Bernardo notes that those who insist that Maths be taught

in English assume some kind of structural-ft efect between English and mathematics

learning and performance (2000: 311) which doesnt exist.

Martins study of code-switching in college Science analyzed two cases which found

that the practice does in fact support the goals of delivering content knowledge. Code-

switching was used by Science teachers as a pedagogical tool for motivating student

response and action, ensuring rapport and solidarity, promoting shared meaning, check-

ing student understanding, and maintaining the teaching narrative (Martin 2006).

English teachers in the public schools also report that they code-switch when they

teach. Dionisia B. Fernandez writes about how the English-only policy did not work in

her school:

One rule I have in my classroom is fairly simple: Speak only English! It was agreed

that whoever broke this rule would pay a fne of one peso for each non-English

word. For two days my students tried very hard to speak English only...

A week afer imposing the Speak English Only campaign, I felt frustrated not

because the students carabao English worsened, or that the class treasurer did not

collect a single peso, but because most of my pupils chose to keep their mouths

shut. Te campaign was a failure! (Fernandez 2009)

What this teacher learned from her experience of the English Only campaign is the

need for some form of resistance to the impositions of language planning and policy in

the Philippines. Te difusions in the language policy situation, from the American

colonial period to contemporary times, only contribute to the promotion of the fol-

lowing myths about English in the Philippines: (1) English and Filipino are languages

in opposition; (2) English is the only cure to all economic ailments; and (3) English is

ioo Isabel Pefanco Martin

the only access to knowledge. If these myths persist, basic education in the Philippines

will be pushed farther to the periphery.

4. Directions for language planning and policy formulation

In his analysis of the Philippine language situation, Schneider observes that the

Philippines could be an example of a country where the predictive implications of the

dynamic model (of new Englishes) may fail (Schneider 2003: 17). Te Philippines

does not seem to be moving into what Schneider identifes as the stage of endonorma-

tive stabilization that stage in which the ...psychological independence and the

acceptance of a new, indigenous identity, result in the acceptance of local forms of

English as a means of expression of that new identity (Schneider 2003: 11).

What Schneider refers to as a local form of English is a variety now known as

Philippine English or PhilE.

3

However, the existence of a Philippine variety of English

does not necessarily translate into acceptance of that variety. When asked why they

identifed American English as their target model for English Language Teaching or

ELT, Filipino teachers gave the following reasons (Martin 2010: 253):

1. It is a global language.

2. American English is the universal language.

3. American English is the standard international language.

4. Tey [Filipino students] have to frst learn the basics.

5. American English is universally accepted.

6. Knowing American English can avoid arguments and debates about the correct

spelling and pronunciation.

7. Te pronunciation of some words is conventional.

8. An approximately correct English understandable and acceptable internationally

9. It is the most accepted English.

10. Its the ideal, the standard in terms of language usage.

11. American English is applicable nationwide.

12. Because the expressions used are familiar to us having being under the American

regime/way of education.

13. Because the Americans were the frst to teach English to the Filipinos.

14. So that pupils will become more eloquent, smart in talking, and be able to com-

municate in the language not only in speaking but in writing as well.

15. You could use American movies as patterns for [teaching] speaking skills.

16. Its widely used in communicative learning.

3. Bautista (2000) presents a comprehensive discussion of the grammatical features of Philip-

pine English.

Chapter 11. Difusion and directions io:

Te list above betrays what Kachru (1995) refers to as the Model Dependency Myth,

which hinges on the belief that the exocentric models of American and British English

are standard and must therefore be taught. Such dependence on the American model

is further reinforced by the fact that the language was brought to the Philippines as a

colonial tool (evident in reasons 12 and 13 above). Te albatross of mythology, as

Kachru (2005: 16) puts it, weighs heavy around the necks of Filipino teachers of Eng-

lish so much so that even the strategies for teaching the language have become depen-

dent on American texts (reason 15 above).

Te First Quarter 2008 Social Weather Survey reported a slight improvement in

the Filipinos self-assessment of English profciency from the previous 2006 survey.

Te number of Filipinos who believe that they were not competent in English has de-

creased (Social Weather Stations 2008). One wonders if this is an indication of a grow-

ing acceptance of or confdence in the language. Whatever the case may be, difusions

in Philippine language planning and policy formulation persist and do not contribute

to upgrading basic education in the country.

In July 2009, the DepEd issued Order No. 74 which calls for the institutionalizing

of mother-tongue based multilingual education (henceforth MTB MLE) in the whole

stretch of formal education including pre-school and in the Alternative Learning Sys-

tem (ALS) (Department of Education 2009). Tis order was intended to be an exten-

sion of the Lingua Franca Education Project which the DepEd launched in 1999 in an

earlier attempt to address the perceived weaknesses of using only English and Filipino

in basic education. It was reported that more than a hundred schools throughout the

nation will begin implementing MTB MLE in the sixty DepEd divisions of the coun-

trys sixteen regions (Talete 2010).

DepEd Order No. 74 was welcomed by language stakeholders as a positive contri-

bution to the promotion of the mother tongue in basic education, as well as the upgrad-

ing of teaching and learning in the public schools. However, the full implementation of

the MTB MLE Order will take some time to achieve since the order sets ten fundamen-

tal requirements for implementation, among them, the development of a working or-

thography for the local languages and the intellectualization of these languages

(Department of Education 2009). It is also unfortunate that the order comes at a time of

crucial leadership changes in the education department. A few months afer the order

was released, a new education secretary was appointed. Tis new secretary is expected

to be replaced again soon afer the May 2010 national elections. Such a situation, the

rapid turnover of leadership in the education department, was identifed as one obstacle

to genuine educational reforms. Bautista, Bernardo and Ocampo (2008/2009: 30) ob-

serve that the rapid succession of DepEds top leaders six secretaries in eight years

since 2000! has lef very little time for the theoretical and empirical arguments

surrounding the language issue to sink in. In addition, the fast-paced turnover of lead-

ership in the education department creates an atmosphere that tends to tilt the perspec-

tive towards the half-empty outlook (Bautista et al. 2008/2009: 37). One wonders what

the future will be for mother-tongue based multilingual education in the Philippines.

ioi Isabel Pefanco Martin

In language planning, it is important to be mindful of the reality that language is

not a fxed code. In fact, the term language planning is in itself already problematic.

Can language be planned? Gonzales (2003: 1) asks the same question which is also the

title of a 1971 book by Rubin and Jernudd. Gonzales notes that afer more than three

decades of his involvement in language planning and policy formulation, he too has

been asking the same question. He writes:

... language planning presumes rationality on the part of the language planners

in drafing action plans, but these action plans likewise presume rationality on

the part of the political decision-makers and would-be benefciaries (parents and

their children) of these rational policies. Unfortunately, in a world not quite fully

rational, rational means to realize plans do not always obtain and results are ofen

mixed, which they are in the Philippines! (Gonzales 2003: 5)

Te language policy situation in the Philippines may persist in its irrelevance if deci-

sions continue to be made in conficting and contradictory terms. However, in ad-

dressing the negative impact of difusions in language planning, the answer does not

lie in doing the opposite in centralizing decision-making. On the contrary, any at-

tempt at homogenizing the implementation of language policies may be doomed to

fail, especially when the implementation does not address deeper social issues besieg-

ing the country, among them, the continued deterioration of basic education, which

results from and contributes to poverty among Filipinos. Tupas (2009: 3) strongly ar-

gues for a language policy that is generated from the ground. He writes:

... the problem of language is ultimately a problem of development. Language

policy becomes more useful and fair if it re-views languages in education from

the point of view of the schools of the people. Tese schools have disengaged from

language policy in order to transform education on the ground. (Tupas 2009: 3)

To be sure, language is not the only force impacting the present education crisis in the

Philippines. Tere are many other forces to contend with. However, the absence of a

genuine commitment to mother-tongue literacy may only hasten the deterioration of

education and push Filipino schoolchildren deeper into the poverty pit. In the end, the

question that needs to be asked is not whether the Philippine government should pro-

mote one or two or three languages. Te question is not whether language policy

should favour English or Filipino or both or neither. Te questions that must be asked

are What must language policy be truly concerned about? What is language policy

ultimately for? Tese are questions that have yet to be asked, let alone answered.

References

14th Congress of the Republic of the Philippines. 2008. An Act Establishing a Multi-lingual

Education and Literacy Program (House Bill 3719).

Chapter 11. Difusion and directions io

Annex Teacher. 1928. Te infuence of noted authors on the Philippines. Graphic March 31: 7.

Arroyo, G. 2001. State of the Nation Address at the Opening of Congress, Batasang Pambansa,

Quezon City on 23 July 2001.

Arroyo, G. 2003. Establishing the Policy to Strengthen the Use of the English Language as a

Medium of Instruction in the Educational System. Executive Order No. 210, 17 May 2003.

<http://elibrary.judiciary.gov.ph/index10.php?doctype=Executive+Orders&docid=a45475

a11ec72b843d74959b60fd7bd645f73003691a4> (11 May 2011).

Arroyo, G. 2006. State of the Nation Address at the Opening of Congress, Batasang Pambansa,

Quezon City on 24 July 2006.

Arroyo, G. 2007. State of the Nation Address at the Opening of Congress, Batasang Pambansa,

Quezon City on 23 July 2007.

Bautista, M.L.S. 1996. An outline: Te national language and the language of instruction. In

Readings in Philippine Sociolinguistics, 2nd edn., M.L.S. Bautista (ed), 223227. Manila: De

La Salle University Press.

Bautista, M.L.S. 2000. Te grammatical features of educated Philippine English. In Parangal cang

Brother Andrew: Festschrif for Andrew Gonzalez on his sixtieth birthday, M.L.S. Bautista,

T.A. Llamzon & B.P. Sibayan (eds), 146158. Manila: Linguistic Society of the Philippines.

Bautista, M.C.R.B, Bernardo, A.B.I. & Ocampo, D. 2008/2009. When reforms dont transform:

Refections on institutional reforms in the Department of Education. Human Development

Network, University of the Philippines, Diliman, Quezon City. <http://hdn.org.ph/wp-con-

tent/uploads/2010/07/When-Reforms-Dont-Transform.pdf> (11 May 2011).

Bernardo, A. 2000. Te multifarious efects of language on mathematical learning and perfor-

mance among bilinguals: A cognitive science perspective. In Parangal Cang Brother An-

drew: Festschrif for Andrew Gonzalez on His Sixtieth Birthday, M.L. Bautista, T. Llamzon &

B. Sibayan (eds), 303316. Manila: Linguistic Society of the Philippines.

Board of Educational Survey. 1925. A Survey of the Educational System of the Philippine Islands.

Manila: Bureau of Printing.

Caoli-Rodriguez, R. 2007. Te Philippines country case study. Country Profle Commissioned

for the EFA Global Monitoring Report 2008, Education for All by 2015: Will We Make It?

UNESCO. <http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0015/001555/155516e.pdf > (4 July 2008).

Constantino, R. 1982. Te Miseducation of the Filipino. Quezon City: Foundation for Nationalist

Studies.

Department of Education. 2008a. English profciency: DepEds fagship program in 2008. Ofce

of the Secretary, 15 January 2008. <http://www.deped.gov.ph> (4 July 2008).

Department of Education. 2008b. Basic education statistics (data fle), 11 September 2008.

<http://www.deped.gov.ph/factsandfgures/default.asp> (17 November 2008).

Department of Education. 2009. Institutionalizing mother-tongue based multilingual education

[DepEd Order No. 74, Series 2009], 14 July 2009. <http://www.deped.gov.ph> (11 October

2009).

Estioko, L. 1994. History of Education: A Filipino Perspective. Manila: Society of Divine Word.

Fernandez, D. 2009. Te Red Carabao. In How, How the Carabao: Tales of Teaching English in the

Philippines, I.P. Martin (ed), 2124. Quezon City: Ateneo de Manila University Loyola

Schools.

Gonzales, A. 1996. Language and nationalism in the Philippines: An update. In Readings in

Philippine Sociolinguistics, M.L.S. Bautista (ed), 228239. Manila: DLSU Press.

Gonzales, A. 1998. Te language planning situation in the Philippines. Journal of Multilingual

and Multicultural Development 19(5/6): 487525.

io| Isabel Pefanco Martin

Gonzales, A. 1999. Philippine bilingual education revisited. In Te Filipino Bilingual: A Multidis-

ciplinary Perspective [Festschrif in honor of Emy M. Pascasio], M.L.S. Bautista & G. Tan

(eds), 1115. Manila: Linguistic Society of the Philippines.

Gonzales, A. 2003. Language Planning in Multilingual Countries: Te Case of the Philippines.

Manila: Andrew Gonzales.

Kachru, B.B. 1995. Te intercultural nature of modern English. In 1995 Global Cultural Diversity

Conference Proceedings, Department of Immigration and Citizenship, Sydney, Australia.

<http://www.immi.gov.au/media/publications/multicultural/ confer/04/speech19a.htm> (17

November 2008).

Kachru, B.B. 2005. Asian Englishes: Beyond the Canon. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press.

Keitel, R. 2008. Academe-call center partnerships. Manila Bulletin Online, 20 January 2008. <http://

www.mb.com.ph/issues/2008/01/20/OPED20080120114885.html> (27 November 2008).

Martel, R. 2008. Spreading English as opposed to Taglish. Te Manila Times, 10 June 2008,

<http://www.manilatimes.net> (4 July 2008).

Martin, I.P. 2006. Language in Philippine classrooms: Enabling or enfeebling? Asian Englishes

9(2): 4867.

Martin, I.P. 2010. Periphery ELT: Te politics and practice of teaching English in the Philip-

pines. In Te Routledge Handbook of World Englishes, A. Kirkpatrick (ed), 247264. London:

Routledge.

National Statistical Coordination Board. 2007. Factsheet: Students Scores in Achievement tests

Deteriorating. <http://www.ncsb.gov.ph/factsheet/pdf07/FS-200705-SS2-01.asp> (22 No-

vember 2008).

Nolasco, R.M. 2008. Te prospects of multilingual education and literacy in the Philippines. In

Te Paradox of Philippine Education and Education Reform: Social Science Perspectives, A.

Bernardo (ed), 133145. Quezon City: Philippine Social Science Council.

Pazzibugan, D. 2003. President wants English back; Estrada objects. INQ7.net, 29 January 2003.

< http://www.inq7.net/nat/2003/jan/30/text/nat_6-1-p.html> (22 October 2003).

Philippine Overseas Employment Administration (POEA). 2005. Filipino Workers: Moving the

World Today [Employers Guide]. <http://www.poea.gov.ph/about/moving.htm> (25 No-

vember 2008).

Rubin, J. & Jernudd, B. (eds). 1971. Can Language Be Planned? Sociolinguistic Teory and Prac-

tice for Developing Nations. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press.

Sandlin, R. 2008. English remains the only hope of the Philippines [Letter to the editor]. Philip-

pine Daily Inquirer, 11 March 2008. <http://opinion.inquirer.net/inquireropinion/lettersto-

theeditor/view/20080311-123952/English-remains-the-only-hope-of-the-Philippines> (11

May 2011).

Schneider, E. 2003. Te dynamics of new Englishes: From identity construction to dialect birth.

Language 79(2): 233281.

Social Weather Stations. 2008. First Quarter 2008 Social Weather Survey: National profciency

in English recovers. SWS Media Release, 16 May 2008. < http://www.sws.org.ph/pr080516.

htm > (24 November 2008).

Sunstar Cebu. 2008. House to pass English bill: Gullas. Sun.Star Archive, 11 February 2008.

<http://www.sunstar.com.ph/static/ceb/2008/02/11/news/house.to.pass.english.bill.gullas.

html> (28 November 2008).

Talete, H.C. 2010. Deped pushes for the use of mother tongue to develop better learners. Positive

News Media, 21 April 2010. <http://www.positivenewsmedia.net/am2/publish/Education_

Chapter 11. Difusion and directions io,

20/DepEd_pushes_for_the_use_of_Mother_Tongue_to_develop_better_learners.shtml>

(28 April 2010).

Te Manila Times. 2007. Lawmaker sees need for English. Worldnews.com, 22 December 2007.

<http://article.wn.com/view/2007/12/21/Lawmaker_sees_need_for_English/> (11 July 2008).

Torres, T. 2007. SC asked to nullify directives on English as teaching medium. INQUIRER.net,

27 April 2007. <http://services.inquirer.net/print/print.php?article_id=20070427-62876>

(11 November 2008).

Tupas, T.R. 2007. Back to class: Te ideological structure of the medium of instruction debate in

the Philippines. In (Re)making Society: Te Politics of Language, Discourse, and Identity in

the Philippines, T.R. Tupas (ed), 6184. Quezon City: University of the Philippines Press.

Tupas, T.R. 2009. Language as a problem of development. AILA Review 22: 2335.

UNESCO-Philippine Educational Foundation. 1953. Fify Years of Education for Freedom: 1901

1951. Manila: National Printing Co., Inc.

Villafania, A. 2007. Ateneo president tapped to head education task force. Inquirer.net, 4 Sep-

tember 2007. <http://newsinfo.inquirer.net/breakingnews/nation/view/20070904-86613/

Ateneo_president_tapped_to_head_education_task_force> (5 May 2005).

Villafania, A. 2009. Educators trained on native tongue teaching. Inquirer.net, 8 May 2009.

<http://newsinfo.inquirer.net/breakingnews/nation/view/20090508-203915/Educat> (14

May 2009).

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- FHENGSUIDocument3 pagesFHENGSUIjessa alambanPas encore d'évaluation

- The Pedagogical Role of English in Labor ReproductionDocument12 pagesThe Pedagogical Role of English in Labor ReproductionPearl CartasPas encore d'évaluation

- Language Planning in Multilingual Countries The Case of The PhilippinesDocument6 pagesLanguage Planning in Multilingual Countries The Case of The PhilippinesNasrun Hensome ManPas encore d'évaluation

- Language GovernmentalityDocument6 pagesLanguage GovernmentalityAnne Jellica TomasPas encore d'évaluation

- The Filipino Language: The National Language of the PhilippinesDocument4 pagesThe Filipino Language: The National Language of the PhilippinesJoel Puruganan SaladinoPas encore d'évaluation

- Read This!Document12 pagesRead This!Cherry Ann Marcial NabascaPas encore d'évaluation

- Don Honorio Ventura State University: Moras Dela Paz, Sto. Tomas, PampangaDocument3 pagesDon Honorio Ventura State University: Moras Dela Paz, Sto. Tomas, PampangaBernie TuraPas encore d'évaluation

- A History of The Philippines' Official LanguagesDocument4 pagesA History of The Philippines' Official LanguagesJemuel VillaPas encore d'évaluation

- 4th Reading Sa MAF 612 Tupas and Lorente A New Politics of Language in The PhilippinesDocument16 pages4th Reading Sa MAF 612 Tupas and Lorente A New Politics of Language in The Philippinesvanessa ordillanoPas encore d'évaluation

- English in Philippine Education: Solution or Problem?: Allan B. I. BernardoDocument20 pagesEnglish in Philippine Education: Solution or Problem?: Allan B. I. BernardoBilly RemullaPas encore d'évaluation

- The Filipino National Language: Discourse On Power: By: Teresita Gimenez MacedaDocument20 pagesThe Filipino National Language: Discourse On Power: By: Teresita Gimenez MacedaAlfonso Tilbe SiervoPas encore d'évaluation

- The Chapter 1 SummaryDocument6 pagesThe Chapter 1 SummarySirc SeralPas encore d'évaluation

- Part I. Definition of TermsDocument16 pagesPart I. Definition of TermsJstn RjsPas encore d'évaluation

- English As A Medium of Instruction in PHDocument10 pagesEnglish As A Medium of Instruction in PHTom Rico Divinaflor100% (1)

- Manarpaac. Reflecting On The Limits of A Nationalist Language PolicyDocument12 pagesManarpaac. Reflecting On The Limits of A Nationalist Language PolicyR.k. Deang67% (3)

- History and Development of English in The PhilippinesDocument12 pagesHistory and Development of English in The Philippinesfrenzvincentvillasis26Pas encore d'évaluation

- Bernardo2004 2Document16 pagesBernardo2004 2olga orbasePas encore d'évaluation

- The War of Translation ColoniDocument21 pagesThe War of Translation ColoniETHAN YEO WEI CHENGPas encore d'évaluation

- Language Planning and Education in Philippine HistoryDocument49 pagesLanguage Planning and Education in Philippine HistoryMeri LynPas encore d'évaluation

- Mckinleys Questionable Bequest Over 100 Years of English in Philippine EducationDocument13 pagesMckinleys Questionable Bequest Over 100 Years of English in Philippine EducationTeacher LearPas encore d'évaluation

- MTB-MLE in The PhilippinesDocument88 pagesMTB-MLE in The PhilippinesConnie Honrado Ramos100% (3)

- EDRADAN - Education Policy EvolutionDocument5 pagesEDRADAN - Education Policy EvolutionFriedrich Carlo Jr. EdradanPas encore d'évaluation

- World English AssignmentDocument7 pagesWorld English AssignmentKetMaiPas encore d'évaluation

- ENG104 Midterm ReviewerDocument7 pagesENG104 Midterm ReviewerJu DumplingsPas encore d'évaluation

- Filipino Language in Education CurriculumDocument4 pagesFilipino Language in Education CurriculumAngelica Faye LitonjuaPas encore d'évaluation

- Breakout Room 4 ELT in Spanish, American and Japanese TimeDocument12 pagesBreakout Room 4 ELT in Spanish, American and Japanese Timerussell torresPas encore d'évaluation

- English Language in The Philippine Education: Themes and Variations in PolicyDocument3 pagesEnglish Language in The Philippine Education: Themes and Variations in PolicyJonathan L. MagalongPas encore d'évaluation

- Failure of The Spanish Language EducationDocument2 pagesFailure of The Spanish Language EducationBlinky Antonette FuentesPas encore d'évaluation

- History of Mother TongueDocument4 pagesHistory of Mother TongueJim Boy BumalinPas encore d'évaluation

- The Development of The National Language and BilingualsDocument1 pageThe Development of The National Language and BilingualsBlinky Antonette FuentesPas encore d'évaluation

- Philippines' Language Planning and Policy Language/s According To The 1987 ConstitutionDocument4 pagesPhilippines' Language Planning and Policy Language/s According To The 1987 ConstitutionIvan DatuPas encore d'évaluation

- KapculDocument8 pagesKapculCharina Sunido GuarinoPas encore d'évaluation

- 7 EL 104 - Language in Education Policies in The Philippines Through The YearsDocument5 pages7 EL 104 - Language in Education Policies in The Philippines Through The YearsAngel RodriguezPas encore d'évaluation

- Philippines - Group 7 DraftDocument12 pagesPhilippines - Group 7 DraftAngelika LazaroPas encore d'évaluation

- Constitutional Provisions On Language in The PhilippinesDocument9 pagesConstitutional Provisions On Language in The Philippinesnina_jane_1Pas encore d'évaluation

- Module of Mother TongueDocument3 pagesModule of Mother TongueJhay Son Monzour DecatoriaPas encore d'évaluation

- Eng221 ReviewerDocument8 pagesEng221 Reviewerbraga.jansenPas encore d'évaluation

- FilipinoDocument5 pagesFilipinoSon Chaeyoung MinariPas encore d'évaluation

- Over 100 Years of English in Philippine EducationDocument19 pagesOver 100 Years of English in Philippine EducationLorraineBCastroPas encore d'évaluation

- Philippines Language PlanningDocument39 pagesPhilippines Language Planningcristiana_23100% (1)

- Research Paper On The Impact of American Education On The PhilippinesDocument6 pagesResearch Paper On The Impact of American Education On The PhilippinesSamuel Grant ZabalaPas encore d'évaluation

- Some Problems in Philippine LinguisticsDocument8 pagesSome Problems in Philippine LinguisticsFrancis Roi RañadaPas encore d'évaluation

- ENG221Document15 pagesENG221proxima midnightxPas encore d'évaluation

- Content and Pedagogy in Mother Tongue Based Multilingual EducationDocument33 pagesContent and Pedagogy in Mother Tongue Based Multilingual EducationJanelle PunzalanPas encore d'évaluation

- Statement of Problem: Chapter I - IntroductionDocument8 pagesStatement of Problem: Chapter I - IntroductionFrazaMaePerualilaPas encore d'évaluation

- Lesson 3 Language in Education Policy EvolutionDocument7 pagesLesson 3 Language in Education Policy EvolutionConan GrayPas encore d'évaluation

- The Metamorphosis of Filipino As National LanguageDocument15 pagesThe Metamorphosis of Filipino As National LanguageKyel LopezPas encore d'évaluation

- The Metamorphosis of Filipino As National Language: Jessie Grace U. RubricoDocument8 pagesThe Metamorphosis of Filipino As National Language: Jessie Grace U. RubricoMargaux Ramirez0% (1)

- Language Policy and Local Literature in The PhilippinesDocument8 pagesLanguage Policy and Local Literature in The PhilippinesĐoh RģPas encore d'évaluation

- Language in Education Policy in The PhilippinesDocument16 pagesLanguage in Education Policy in The PhilippinesMaribel Nitor LopezPas encore d'évaluation

- See 6Document7 pagesSee 6titechan69Pas encore d'évaluation

- Synthesis PaperDocument2 pagesSynthesis PaperJulaton JericoPas encore d'évaluation

- The Intellectualization of FilipinoDocument14 pagesThe Intellectualization of Filipinokim beverly Feranco100% (1)

- History of Phil. EnglishDocument76 pagesHistory of Phil. EnglishFernandez LynPas encore d'évaluation

- Pele PensDocument6 pagesPele PensJohn Kinno CasiaPas encore d'évaluation

- An American Language: The History of Spanish in the United StatesD'EverandAn American Language: The History of Spanish in the United StatesPas encore d'évaluation

- Survival Tagalog: How to Communicate without Fuss or Fear - Instantly! (Tagalog Phrasebook)D'EverandSurvival Tagalog: How to Communicate without Fuss or Fear - Instantly! (Tagalog Phrasebook)Pas encore d'évaluation

- Manual of American English Pronunciation for Adult Foreign StudentsD'EverandManual of American English Pronunciation for Adult Foreign StudentsPas encore d'évaluation

- Education Issues in Creole and Creole-Influenced Vernacular ContextsD'EverandEducation Issues in Creole and Creole-Influenced Vernacular ContextsPas encore d'évaluation

- 1st Summative TEST OCDocument1 page1st Summative TEST OCRyan BustilloPas encore d'évaluation

- Oc Timeline Topic DiscussionDocument1 pageOc Timeline Topic DiscussionRyan BustilloPas encore d'évaluation

- OC First Day ActivityDocument4 pagesOC First Day ActivityRyan BustilloPas encore d'évaluation

- Ucsp 4th Quarter Long TestDocument1 pageUcsp 4th Quarter Long TestRyan Bustillo100% (1)

- Summative Test 11-SodiumDocument2 pagesSummative Test 11-SodiumRyan BustilloPas encore d'évaluation

- Table of Specification in Oral CommunicationDocument3 pagesTable of Specification in Oral CommunicationRyan Bustillo100% (1)

- Oc PretestDocument6 pagesOc PretestRyan BustilloPas encore d'évaluation

- 11-Selenium Attendance SheetsDocument16 pages11-Selenium Attendance SheetsRyan BustilloPas encore d'évaluation

- Oc First WeekDocument65 pagesOc First WeekRyan BustilloPas encore d'évaluation

- MALONES - Thinkingand Writing Task No. 1Document2 pagesMALONES - Thinkingand Writing Task No. 1Ryan BustilloPas encore d'évaluation

- Oral Com 3rd Summative TestDocument4 pagesOral Com 3rd Summative TestRyan BustilloPas encore d'évaluation

- Ucsp Summative 2Document2 pagesUcsp Summative 2Ryan BustilloPas encore d'évaluation

- Julia Espanola Oration SpeechDocument2 pagesJulia Espanola Oration SpeechRyan BustilloPas encore d'évaluation

- 1ST Summative Test 21ST Cent. Lit.Document2 pages1ST Summative Test 21ST Cent. Lit.Ryan BustilloPas encore d'évaluation

- 1ST Summative Test 21ST Cent. Lit.Document2 pages1ST Summative Test 21ST Cent. Lit.Ryan BustilloPas encore d'évaluation

- Activity :examDocument2 pagesActivity :examRyan BustilloPas encore d'évaluation

- How The World Was CreatedDocument1 pageHow The World Was CreatedRyan BustilloPas encore d'évaluation

- Document PDFDocument12 pagesDocument PDFmohammed balakyPas encore d'évaluation

- 1ST Summative Test 21ST Cent. Lit.Document2 pages1ST Summative Test 21ST Cent. Lit.Ryan BustilloPas encore d'évaluation

- Cabinet ProposalDocument4 pagesCabinet ProposalRyan BustilloPas encore d'évaluation

- Oral Communication in Context: References and Photo CreditsDocument2 pagesOral Communication in Context: References and Photo CreditsRyan BustilloPas encore d'évaluation

- Orientation On Supplementary Learning Materials (SLM) DevelopmentDocument26 pagesOrientation On Supplementary Learning Materials (SLM) DevelopmentRyan BustilloPas encore d'évaluation

- Literature ReviewDocument9 pagesLiterature ReviewRyan BustilloPas encore d'évaluation

- Long Exam in UcspDocument2 pagesLong Exam in UcspRyan Bustillo100% (2)

- Summative Test 11-SodiumDocument2 pagesSummative Test 11-SodiumRyan BustilloPas encore d'évaluation

- How to Write a Coherent ParagraphDocument53 pagesHow to Write a Coherent ParagraphRyan BustilloPas encore d'évaluation

- 21st CL 3rd SUMMATIVE TESTDocument3 pages21st CL 3rd SUMMATIVE TESTRyan BustilloPas encore d'évaluation

- Critical Reading As Looking For Ways of ThinkingDocument52 pagesCritical Reading As Looking For Ways of ThinkingRyan BustilloPas encore d'évaluation

- Critical Reading As Looking For Ways of ThinkingDocument52 pagesCritical Reading As Looking For Ways of ThinkingRyan BustilloPas encore d'évaluation

- Critical Reading Skills for College StudentsDocument14 pagesCritical Reading Skills for College StudentsYrnelle Cee CzarPas encore d'évaluation

- Utilizing The Social Media in Evangelizing The YouthDocument32 pagesUtilizing The Social Media in Evangelizing The YouthRonalyn Ablang100% (1)

- Introduction to Event Management: Understanding MICE ConceptDocument49 pagesIntroduction to Event Management: Understanding MICE ConceptMary Ann A. NipayPas encore d'évaluation

- Life, Works and Writings of Dr. Jose RizalDocument12 pagesLife, Works and Writings of Dr. Jose RizalYanna ManuelPas encore d'évaluation

- Science Technology and SocietyDocument8 pagesScience Technology and SocietyMadison CruzPas encore d'évaluation

- LET 08-2014 Secondary-Baguio Room AssignmentDocument242 pagesLET 08-2014 Secondary-Baguio Room AssignmentPRC Baguio100% (1)

- CH 3 STS Philippine HistoryDocument48 pagesCH 3 STS Philippine HistoryCogie PeraltaPas encore d'évaluation

- Types of CurriculumDocument3 pagesTypes of CurriculumGalrich Cid Condesa100% (3)

- Philippine Independence ProclaimedDocument6 pagesPhilippine Independence ProclaimedChristene Tiam0% (1)

- Ayala Land's Strategic Pillars & Marketing StrategiesDocument23 pagesAyala Land's Strategic Pillars & Marketing StrategiesJayfritz FlorPas encore d'évaluation

- Concerns in Philippines After Duterte Given Emergency Powers To Fight COVID-19 Spread March 24, 2020Document3 pagesConcerns in Philippines After Duterte Given Emergency Powers To Fight COVID-19 Spread March 24, 2020Venmarc GuevaraPas encore d'évaluation

- Joseph Ejercito EstradaDocument3 pagesJoseph Ejercito EstradaJoanna Marie Budong CamadoPas encore d'évaluation

- History of Philippine Tourism: From Ancient Times to PresentDocument21 pagesHistory of Philippine Tourism: From Ancient Times to PresentAyen Malabarbas100% (1)

- DOH Performance Report Highlights Health AgendaDocument52 pagesDOH Performance Report Highlights Health AgendaAmiel Francisco ReyesPas encore d'évaluation

- Miseducation of The Filipino NotesDocument4 pagesMiseducation of The Filipino NotesDavidbavePas encore d'évaluation

- Gaa 2023 Vol 1 CDocument1 088 pagesGaa 2023 Vol 1 CKim JinPas encore d'évaluation

- Fil9 q4 Mod13 Pagpapangkatngmgasalita-Ayon-saantasng-pormalida v4Document16 pagesFil9 q4 Mod13 Pagpapangkatngmgasalita-Ayon-saantasng-pormalida v4Reymart BorresPas encore d'évaluation

- Comparative Essay On Ang Tatay Kong Nanay and OliverDocument2 pagesComparative Essay On Ang Tatay Kong Nanay and OliverKat CatalanPas encore d'évaluation

- Bangsamoro Bill Is For Genuine AutonomyDocument7 pagesBangsamoro Bill Is For Genuine AutonomyRegine SagadPas encore d'évaluation

- For Tanod EquipmentDocument2 pagesFor Tanod EquipmentBarangaymananaoevsiqPas encore d'évaluation

- Jose Rizal As Dramatist and NovelistDocument21 pagesJose Rizal As Dramatist and NovelistJeff ValerioPas encore d'évaluation

- Manila Standard Today - August 23, 2012 IssueDocument12 pagesManila Standard Today - August 23, 2012 IssueManila Standard TodayPas encore d'évaluation

- Case Study Revision #2Document24 pagesCase Study Revision #2vince ojedaPas encore d'évaluation

- ESL Teacher ResumeDocument3 pagesESL Teacher ResumeSamantha Louise CarimpongPas encore d'évaluation

- Catholic Practices in Transition: The Case of Mangaldan After The PostwarDocument36 pagesCatholic Practices in Transition: The Case of Mangaldan After The PostwarEzyquel Quinto100% (1)

- Violence Against Women in The PhilippinesDocument6 pagesViolence Against Women in The PhilippinesAaron tv100% (1)

- List of Philippine criminal law casesDocument1 pageList of Philippine criminal law casesLeidi Chua BayudanPas encore d'évaluation

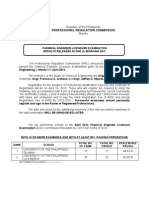

- April 2013 Chemical Engineer Board Exam, Top SchoolsDocument3 pagesApril 2013 Chemical Engineer Board Exam, Top SchoolsScoopBoyPas encore d'évaluation

- Reinforcement Act 6Document6 pagesReinforcement Act 6Ancaja, Jameir 1CPas encore d'évaluation

- Bedan Volunteers who Rendered Service to 2019 Bar CandidatesDocument5 pagesBedan Volunteers who Rendered Service to 2019 Bar CandidatesWazzupPas encore d'évaluation

- Quezon City ZIP Code (Philippines)Document4 pagesQuezon City ZIP Code (Philippines)Azure ZanePas encore d'évaluation