Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Youth Mental Health

Transféré par

Alejandra Márquez CalderónDescription originale:

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Youth Mental Health

Transféré par

Alejandra Márquez CalderónDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 50:4 (2009), pp 386395

doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.2008.01962.x

Youth mental health in a populous city of the developing world: results from the Mexican Adolescent Mental Health Survey

Corina Benjet,1 Guilherme Borges,1,2 Maria Elena Medina-Mora,1 Joaquin Zambrano,1 and Sergio Aguilar-Gaxiola3

1

National Institute of Psychiatry Ramon de la Fuente, Division of Epidemiological and Psychosocial Research, Mexico; 2Metropolitan Autonomous University, Xochimilco Campus, Mexico; 3University of California, Davis, Center for Reducing Health Disparities, School of Medicine, USA

Background: Because the epidemiologic data available for adolescents from the developing world is scarce, the objective is to estimate the prevalence and severity of psychiatric disorders among Mexico City adolescents, the socio-demographic correlates associated with these disorders and service utilization patterns. Methods: This is a multistage probability survey of adolescents aged 12 to 17 residing in Mexico City. Participants were administered the computer-assisted adolescent version of the World Mental Health Composite International Diagnostic Interview by trained lay interviewers in their homes. The response rate was 71% (n = 3005). Descriptive and logistic regression analyses were performed considering the multistage and weighted sample design of the survey. Results: One in every eleven adolescents has suffered a serious mental disorder, one in ve a disorder of moderate severity and one in ten a mild disorder. The majority did not receive treatment. The anxiety disorders were the most prevalent but least severe disorders. The most severe disorders were more likely to receive treatment. The most consistent socio-demographic correlates of mental illness were sex, dropping out of school, and burden unusual at the adolescent stage, such as having had a child, being married or being employed. Parental education was associated with treatment utilization. Conclusions: These high prevalence estimates coupled with low service utilization rates suggest that a greater priority should be given to adolescent mental health in Mexico and to public health policy that both expands the availability of mental health services directed at the adolescent population and reduces barriers to the utilization of existing services. Keywords: Psychiatric disorder, epidemiology, adolescents, Hispanic, World Mental Health Survey Initiative, Mexico.

Insufcient data is available regarding psychiatric disorders in the adolescent population for guiding public mental health policy, especially in developing countries where adolescents generally occupy a much greater proportion of the population (Belfer, 2008; Patel, Flisher, Hetrick, & McGorry, 2007). This is especially relevant as the World Mental Health Surveys from 17 different countries across the world have shown consistently that most psychiatric disorders, unlike most chronic physical conditions, have their rst onset early in life, suggesting the need for a greater focus on the adolescent population (Kessler et al., 2007). For Mexico City, one of the largest cities of the developing world, the situation is no different. The Mexican National Comorbidity Survey found that the median ages of onset of disorders were in the rst decades of life (Medina-Mora, Borges, Benjet, Lara, & Berglund, 2007). According to the year 2000 census, 9.7% of the Mexico City Metropolitan Area is between the ages of 12 and 17, nearly two million adolescents. However, there are no epidemiological general population studies of psychiatric disorders with this age group in Mexico other than the National Addictions

Conict of interest statement: No conicts declared.

Surveys (Mexican Ministry of Health, 1989, 1998, 2002) and the Mexico City Student Surveys (Villatoro et al., 2001) which only estimate substance use. One recent survey which used a screening instrument for psychiatric symptoms, but does not include diagnostic categories, estimates that 15% of Mexico City children and adolescents between 4 and 16 years of age have symptomatology suggestive of a psychiatric disorder (Caraveo-Anduaga, 2007). Epidemiologic surveys of psychiatric disorders among adolescents in other regions of the world (mostly in developed regions like the United States, Britain, Germany and Australia) have reported high rates of mental illness (Costello et al., 1996; Ford, Goodman, & Meltzer, 2003; Sawyer et al., 2001; Shaffer et al., 1996; Wittchen, Nelson, & Lachner, 1998). Costello, Egger, and Angold (2005) in a 10-year update of child and adolescent psychiatric epidemiology report prevalence between 8 and 45% for any psychiatric disorder with a median estimate of just over 25%. Another review of selected prevalence studies since 1995 reports a range from 8% in the Netherlands to 57% in the US (Patel et al., 2007). Recently surveys have been reported in a greater diversity of cultures such as Taiwan (Gau, Chong, Chen, & Cheng, 2005), Brazil (Fleitlich-Bilyk &

2008 The Authors Journal compilation 2008 Association for Child and Adolescent Mental Health. Published by Blackwell Publishing, 9600 Garsington Road, Oxford OX4 2DQ, UK and 350 Main Street, Malden, MA 02148, USA

Psychiatric disorders in Mexican youth

387

Goodman, 2004) and Puerto Rico (Canino et al., 2004), with prevalence estimates uctuating between 12.7 and 23%. Because of the early ages of onset of psychiatric disorders, the large proportion of the population in this age range in Mexico and the lack of epidemiological studies with this population, we conducted the Mexican Adolescent Mental Health Survey. We report here the 12-month prevalence and sociodemographic correlates associated with DSM-IV psychiatric disorders among adolescents living in one of the largest metropolises in the world, the Mexico City Metropolitan Area. Building on prior experiences of high prevalence estimates in community surveys, we also report on the severity of disorders and document the use of services, two issues that have been greatly overlooked in previous surveys. Such estimates are needed to guide public health policy and planning.

All study participants were given contact information for institutions from which they could seek services should they wish to do so. The Human Subjects Committee of the National Institute of Psychiatry approved the recruitment, consent and eld procedures.

Interviewer training and quality control

Lay interviewers were extensively trained in eld procedures, use of the diagnostic instrument and interview techniques, with an initial week-long training by WHOcertied trainers who are also members of the research team, followed by two days of in-eld training and additional booster sessions to maintain quality throughout eldwork. A number of additional actions were taken for quality assurance, such as elaboration of eld manuals, continuous feedback to supervisors and eld managers, independent supervision of both supervisors and interviewers, and the post-eldwork implementation of quality control programs designed for the World Mental Health Survey Initiative to identify possible errors regarding the dating of events (onset and recency, age consistency, etc.), as well as possible missing patterns, and to introduce corrected values when possible.

Methods

Participants

The survey was designed to be representative of the 1,834,661 adolescents aged 12 to 17 who are permanent residents of the Mexico City Metropolitan Area and who are not institutionalized, meaning that street children and those living in correctional facilities, psychiatric hospitals or orphanages were not included. The nal sample included 3,005 adolescents selected from a stratied multistage area probability sample. In all strata, the primary sampling units were census count areas, the Mexican equivalent to US census tracts, cartographically dened and updated in 2000 by the Mexican National Institute of Statistics, Geography and Informatics (INEGI for its abbreviation in Spanish), which is the institution responsible for carrying out the Mexican Census. The average size per census count area varies between 3,000 and 4,000 persons of all ages. Two hundred census count areas were selected with probability proportional to size according to the number of housing units registered by INEGI in the 2000 census. Secondary sampling units were city blocks, four of which were selected with probability proportional to size from each census count area. All households within these selected city blocks with adolescents aged 12 to 17 were selected. One eligible member from each of these households was randomly selected using the Kish method of random number charts. The response rate of eligible respondents was 71%.

Diagnostic assessment

The Mexican Adolescent Mental Health Survey utilized the World Mental Health version of the Adolescent Composite International Diagnostic Interview (WMH stu n, 2004) as the diagnostic tool. CIDI-A; Kessler & U The WMH-CIDI-A is a downward extension of the adult version WMH-CIDI 3.0 used in the M-NCS; this adult version has been validated in diverse countries and cultures (Haro et al., 2006) and reappraisal studies of the adolescent version are under way both in the US and in Mexico. The computer-assisted version was administered in which the interviewer reads the questions to the participant directly from the computer screen; the questions are chosen by the computer based on previous responses of the participant and complex logical skip patterns. The interviewer inputs the respondents answers directly into the computer and several consistency checks are programmed such that inconsistent information is immediately probed and corrected. We report on the 12-month prevalence of psychiatric disorders, classied according to the diagnostic criteria of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV; American Psychiatric Association, 1994). All disorders used organic exclusion rules as well as hierarchy denitions in order to avoid double counting of disorders in the same person. The disorders are grouped as follows: 1. mood disorders: major depressive episode, bipolar I and II disorder (which we group as bipolar broad) and dysthymia; 2. anxiety disorders: specic phobia, social phobia, panic disorder, agoraphobia without panic disorder, separation anxiety disorder, generalized anxiety disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder; 3. substance disorders: alcohol and drug abuse and alcohol and drug abuse with dependence;

Procedures

Face-to-face interviews were carried out in the homes of the selected participants in 2005. A verbal and written explanation of the study was given to both parents and adolescents. Interviews were administered only to those participants for whom signed informed consent from a parent and/or legal guardian and the assent of the adolescent were obtained. The adolescent interview took approximately two and a half hours to administer.

2008 The Authors Journal compilation 2008 Association for Child and Adolescent Mental Health.

388

Corina Benjet et al.

4. impulse-control disorders: oppositional-deant disorder, conduct disorder, attention decit/hyperactivity disorder, and intermittent explosive disorder.

Assessment of disorder severity

Disorders were classied as serious, moderate or mild according to the criteria used in the World Mental Health Survey Initiative, the validity of which is supported by the monotonic association of this measure of severity with the number of days out of role (Demyttenaere et al., 2004). Disorder severity is dened as serious if any one of the following conditions is met: the presence of bipolar I disorder, substance dependence with a physiological dependence syndrome, a suicide attempt in conjunction with any other disorder, or reporting at least two areas of role functioning with severe role impairment as measured by the disorderspecic Sheehan Disability Scales (Sheehan, Harnett-Sheehan, & Raj, 1996). Disorder severity is dened as moderate if the participants did not meet the criteria for a serious disorder, but rated their disability as at least moderate in any Sheehan Disability Scales domain or if the respondent had substance dependence without a physiological dependence syndrome. All other disorders were classied as mild.

burden not typical of the adolescent stage. Working during the school year we consider a burden due to the long hours these adolescents work (a mean of 19 hours per week during the school year) and the unprotected informal sectors in which they work. Having answered afrmatively for any of the three, the participant was categorized as having adolescent burden. The adolescents were asked about the educational attainment of each of their parents which was then categorized as none/primary (6 or fewer years of education), secondary (79 years of education), high school (1012 years of education) or college (13 or more years of education); the score of the parent with the highest level of education was used. Parents reported family income was categorized into tertiles.

Analysis

The data were obtained from a stratied multistage sample and were thus subsequently weighted to adjust for differential probabilities of selection and nonresponse. Post-stratication to the total Mexico City Metropolitan Area adolescent population according to the year 2000 Census in the target age and sex range was also performed. As a result of this complex sample design and weighting, estimates of standard errors for proportions were obtained by the Taylor series linearization method using the SUDAAN software (Research Triangle Institute, 2002). Logistic regression analysis was performed to study demographic correlates (Hosmer & Lemeshow, 2000). Estimates of standard errors of odds ratio (ORs) from logistic regression coefcients were also obtained by SUDAAN, and 95% condence intervals (CI) have been adjusted to design effects. Multivariate tests are based on Wald v2 tests computed from design-adjusted coefcient variance covariance matrices. Statistical signicance was based on two-sided design-based tests evaluated at the .05 level of signicance.

Assessment of service use

Information about 12-month treatment, the type and context of professionals visited, as well as the use of self-help or support groups, hotlines and schoolbased programs was obtained. Twelve-month service use was categorized by service sector. The health-care sector consists of having consulted any mental health provider, including psychiatrists, psychologists, counselors, psychotherapists, mental health nurses, and social workers in a mental health specialty setting, or general medical practitioners, consisting of family physicians and pediatricians; the non-healthcare sector includes human services such as consulting with a social worker or counselor in any setting other than a specialty mental health setting, or a religious advisor, such as a minister, priest, or rabbi, and complementaryalternative medicine including medicinal internet use, self-help groups, and any other healer, such as a herbalist, chiropractor, or spiritualist, and other alternative therapies. Finally, school-based services consists of having attended a special needs school, special classes in school and orientation or school-based therapies.

Results

Socio-demographic distribution

Table 1 presents the un-weighted and weighted socio-demographic distribution of the sample. The weighted sample closely approximates the target population. About two-thirds of the adolescents live with both parents; four-fths are currently students; one in ten has social burdens such as being married, having a child or being employed during the school year. The educational attainment of these adolescents parents represents the overall educational level in Mexico. One-fourth has had 6 years or fewer of formal education whereas only 13% have gone to college. Family income is low in Mexico. The lowest tertile represents those whose monthly family income ranges from US$0 to US$236, the second ranges from US$236.1 to US$708 and the highest corresponds to those whose monthly family income is above US$708.

Assessment of socio-demographic correlates

General information was collected on sex, age and family constellation. Family constellation was categorized as living with both parents or not living with both parents. Participants were considered students if currently enrolled as a student and dropouts if not currently enrolled as a student. Adolescents were asked whether they worked during the school year, whether they were ever married and whether they had children. All three conditions represent an additional

2008 The Authors Journal compilation 2008 Association for Child and Adolescent Mental Health.

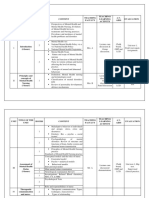

Psychiatric disorders in Mexican youth Table 1 Socio-demographic weighted and un-weighted distribution of the sample,

389

Twelve-month prevalence and severity

The 12-month prevalence and severity of disorders is presented in Table 2. Almost 40% of adolescents reported a 12-month disorder, of which one-fourth were classied as mild disorders, one-half moderate disorders and one-fth were considered serious disorders. The most frequent class of disorders were the anxiety disorders, followed by impulse-control disorders, mood disorders and, least frequent, substance use disorders. Despite being the most frequent, anxiety disorders as a whole were classied as the least severe. Mood disorders, on the other hand, were classied as the most severe. The single most frequent disorders were specic phobia and social phobia which account for 37% of all disorders. The overall 12-month prevalence of psychiatric disorders without including specic and social phobia is 24.7% (SE = .8) (not shown in the table).

Un-weighted % Sex Male Female Age (years) 1214 1517 Living With Parents Yes (both) No (One/none) Current Student Yes No Adolescent Burden Yes No Parents Education None/Primary Secondary (79 years) High School (1012 years) College(13+ years) Parents Income Low Average High SE, Standard Error. 47.9 52.1 58.7 41.3 65.9 34.1 84.1 15.9 10.1 89.9 25.8 37.7 23.2 13.3 36.8 38.1 25.0 SE .9 .9 .9 .9 .9 .9 .7 .7 .5 .5 .8 .9 .8 .6 .9 .9 .8

Weighted % 49.9 50.1 49.3 50.7 65.6 34.4 81.2 18.8 11.5 88.5 26.1 38.0 22.7 13.3 36.8 38.5 24.7 SE 1.1 1.1 1.1 1.1 .7 .7 1.0 1.0 .6 .6 .7 1.5 1.0 .6 1.3 1.0 .8

Disorder severity and treatment

The association of disorder severity and treatment is shown in Table 3. Less than 14% of adolescents with any 12-month disorder received treatment in the same period of time. There is a clear relationship between disorder severity and treatment such that

Table 2 Mexico adolescent 12-month and severity prevalence of CIDI/DSM-IV disorders. 12 month Disorder I. Anxiety Panic disorder Generalized anxiety disorder Agoraphobia Social phobia Specic phobia Separation anxiety Posttraumatic stress disorder Any anxiety disorder II. Mood Major depressive disorder Dysthymia Bipolar disorder (broad) Any mood disorder III. Impulse-control Intermittent explosive disorder Oppositional-deant disorder Conduct disorder Attention-decit/hyperactivity disorder Any impulse-control disorder IV. Substance use Alcohol abuse Alcohol abuse with dependence Drug abuse Drug abuse with dependence Any substance use disorder V. Any disorder Any Total Sample % 1.6 .5 3.6 11.2 20.9 2.6 1.0 29.8 4.8 .5 2.5 7.2 8.7 5.3 3.0 1.6 15.3 2.7 .5 1.1 .2 3.3 39.4 95% CI 1.02.1 .2.8 2.84.5 9.912.5 19.622.2 2.03.3 .81.3 28.231.5 3.95.7 .2.9 1.93.1 6.38.2 7.69.8 4.36.3 2.33.7 .942.3 13.916.6 1.83.5 .2.8 .51.6 .0.4 2.44.2 38.040.9 % 39.3 57.3 30.8 26.5 21.8 34.5 41.4 21.0 40.6 49.3 82.0 54.7 28.0 43.3 44.0 49.9 32.5 27.0 78.5 45.4 100.0 30.9 21.5 8.5 Serious 95% CI 29.449.1 24.889.8 21.140.4 21.831.1 18.225.5 21.347.8 20.262.7 18.024.0 32.249.0 26.971.7 71.492.6 46.862.6 19.736.2 36.150.5 29.758.3 29.869.9 25.839.2 13.840.3 52.8104.3 23.167.7 100.0100.0 17.843.9 18.424.6 7.39.6 % 46.5 34.7 45.5 57.2 52.8 45.1 41.7 52.9 54.0 50.7 18.0 41.8 51.1 51.0 36.0 41.1 50.5 42.8 21.5 27.9 .0 37.8 51.9 20.5 Moderate 95% CI 30.662.4 4.265.3 34.356.8 51.562.9 48.057.6 31.159.1 21.861.6 49.356.4 45.662.5 28.373.1 7.428.6 33.350.2 44.657.7 43.358.8 28.044.1 22.459.8 44.756.2 25.360.3 )4.347.3 14.141.7 .0 23.552.2 48.655.2 18.822.2 % 14.3 8.0 23.7 16.3 25.4 20.3 16.9 26.1 5.4 .0 .0 3.5 20.9 5.6 20.0 9.1 17.0 30.2 .0 26.7 .0 31.3 26.6 10.5 Mild 95% CI 1.926.7 7.423.4 14.433.0 12.320.3 20.930.0 9.830.8 1.432.3 23.528.7 .810.0 .0 .0 .56.6 15.926.2 2.88.5 10.030.0 2.016.2 13.320.8 14.745.6 .0 6.746.8 .0 17.545.1 23.929.3 9.411.6

% , Weighted prevalence estimate; CI, Condence Interval 2008 The Authors Journal compilation 2008 Association for Child and Adolescent Mental Health.

390

Corina Benjet et al.

4.67.6 92.495.4

3.35.3

.31.5

95% Cl

.61.9

almost twice as many adolescents classied as having a serious disorder received treatment as those classied with a mild disorder. A small proportion of adolescents without any disorder also received treatment. Most treatment was provided by the healthcare sector, almost exclusively by mental health care providers (6.1%; data not shown in the table). Some treatment was also provided by services in the school system and by the non-healthcare sector. Virtually no services were received in general medical practice (0.1%; data not shown in the table).

Total

1.7

6.3

2.5 79

280 2725

199

46

9.1 90.9

7.810.4 89.692.2

1.12.3

5.27.5

1.83.2

95% CI

None

4.3

6.1 93.9

1.3

Socio-demographic correlates of psychiatric disorders

Table 4 presents the socio-demographic correlates of 12-month disorders for any disorder, for serious disorders and for each group of disorders individually. Being female, having dropped out of school and being burdened with adult responsibility were associated with greater odds of having any 12-month disorder, and having a serious disorder. With regard to specic socio-demographic correlates for different types of disorders, females were more likely to report mood and anxiety disorder but less likely to report a substance use disorder. Younger age was associated only with a lower report of substance use disorders. Not living with both parents was a risk factor for impulse-control disorders only. Those adolescents no longer in school had larger odds ratios for mood, substance use and impulse-control disorders. Those with adolescent burden had greater odds for all types of disorders. Less parental education was associated with lesser odds of mood disorders.

83

.9 15

24 3.9 13 4.5 29 2.46.5 1.66.1

Mild

6.5

1.7

6.212.1

Moderate

9.2

2.8

9.119.3

13.524.9 75.186.5

81 527

58

14

13.2 86.8

10.216.1 83.989.8

1.04.7

95% Cl

33 280

21

10.4 89.6

6.614.3 85.793.4

3.29.8

95% Cl

.13.3

115 1722

1.77.4

2.17.6

95% Cl

Socio-demographic correlates of treatment utilization

Table 5 shows the results of a multivariate model of treatment utilization, controlling for disorder severity. Overall, none of the socio-demographic variables included were associated to whether the adolescents received treatment. Only low parental education (primary school or less) had lesser odds of receiving treatment.

Serious

4.5

4.8

19.2 80.8 11.316.2 83.888.7 51 196

14.2

%, Weighted prevalence estimate; Cl, Condence Interval

37

12 1.74.1

7.112.0

Any Disorder

2.95.9

95% Cl

13

Discussion

General ndings

One in every 11 adolescents in the Mexico City Metropolitan Area has suffered a serious mental disorder, one in ve a disorder of moderate severity and one in ten a mild disorder. The majority of these adolescents did not receive treatment. Especially worrisome is the lack of use of general physicians (pediatricians) that in many countries are the key source of entry and care before more specialized resources come into play. Fortunately, the most

9.5

2.9

4.4 55

Table 3 Severity by treatment

116

Any health care services Any non-health care service Any schoolbased services Any treatment No treatment

Service

165 1003

31

13.7 86.3

2008 The Authors Journal compilation 2008 Association for Child and Adolescent Mental Health.

Table 4 Socio-demographic correlates of 12-month DSM-IV disorders using weights after stratication

Any 12 month Disorder Serious Disorder OR 1.89 1.00 1.35 1.00 1.58 1.00 1.99 1.00 1.81 1.00 1.00 1.07 1.09 1.00 1.11 .80 1.00 .841.48 .571.14 1.03 .95 1.00 .671.58 .661.36 1.00 .89 1.00 .551.82 .611.90 .651.82 .55 .52 .85 1.00 .37.83* .35.78* .58 1.25 1.22 1.30 1.24 1.00 1.202.74* 1.80 1.00 1.212.67* 1.34 1.00 1.021.75* 1.283.11* 2.16 1.00 1.493.13* 1.26 1.00 .911.76 1.142.20* 1.10 1.00 .721.68 1.03 1.00 .821.29 1.34 1.00 1.44 1.00 2.08 1.00 .971.53 1.031.64 .941.63 .75 .76 .73 1.00 .771.28 .741.08 .97 1.12 1.00 .951.91 1.24 1.00 .931.65 .91 1.00 .781.07 1.23 1.00 1.492.40* 2.54 1.00 1.753.68* 1.66 1.00 1.441.90* 1.14 1.00 .911.42* 95% C1 OR 95%Cl OR 95% CI OR 95% CI Mood Anxiety Impulse-control OR .58 1.00 4.46 1.00 1.021.77* .76 1.00 1.091.91* 2.16 1.00 1.512.86* 1.95 1.00 .481.16 .501.15 .531.01 .74 .79 .75 1.00 .751.25 .841.50 .54 .82 1.00

Substance 95%CI .34.98*

OR

95%Cl

1.38 1.00

1.191.60*

1.11 1.00

.921.33

.851.79

2.238.95*

1.13 1.00

.921.39

.461.27

1.51 1.00

1.151.98*

1.323.52*

2008 The Authors Journal compilation 2008 Association for Child and Adolescent Mental Health. 1.023.73* .341.61 .461.38 .381.48 .30.96* .451.49 Psychiatric disorders in Mexican youth

1.69 1.00

1.342.13*

.98 1.05 .99 1.00

.791.21 .811.37 .791.25

Sex Female Male Age(years) 1517 1214 Living With Parents No (One/none) Yes (both) Current Student No Yes Adolescent Burden Yes No Parents Education None/Primary Secondary (79 yrs) High School (1012 yrs) College (13+ yrs) Parents Income Low Average High

.97 .91 1.00

.761.24 .721.16

OR, Odds Ratio; CI, Condence Interval. *Signicant at the 0.05 level, twosided test.

391

392

Corina Benjet et al.

Table 5 Socio-demographic correlates of 12-month treatment Any 12 month Disorder OR Sex Female Male Age(years) 1517 1214 Living With Parents No (One/none) Yes (both) Current Student No Yes Adolescent Burden Yes No Parents Education None/Primary Secondary (79 years) High School(1012 years) College(13+ years) Parents Income Low Average High 1.18 1.00 1.07 1.00 1.15 1.00 1.05 1.00 .97 1.00 .49 .72 .84 1.00 .96 .90 1.00 95%Cl .901.54

.811.41

.911.44

.681.62

.591.60

.26.89 .441.20 .551.30

.731.25 .661.25

OR, Odds Ratio; Cl, Condence Interval.

prevalent disorders, the anxiety disorders, are the least severe and the more severe disorders are more likely to receive treatment. The most consistent socio-demographic correlates of mental illness in this population are sex, dropping out of school and adolescent burden. Females are more likely to have any disorder, a serious disorder, a mood or an anxiety disorder and less likely to have a substance use disorder. School dropouts are more likely to have any disorder, a serious disorder, a mood, an impulsecontrol or substance use disorder. Those with adolescent burden such as working, being married or having children are more likely to have any disorder, a serious disorder, and all four groups of disorders. Those with the lowest monthly family income have lesser odds of substance use disorders, possibly indicative of the lack of resources to purchase substances. None of the evaluated factors predicted treatment utilization other than parental education.

process has not extended greatly to differing cultures and languages. To our knowledge none of these instruments has been validated in the Mexican adolescent population. The WMH-CIDI-A was chosen as the diagnostic instrument in order to compare our data with the other participating countries in the World Mental Health Survey Initiative and with the Mexican adult population from the Mexican National Comorbidity Survey (Medina-Mora et al., 2005, 2007). In comparison to the adult version, the language is simplied to be more understandable to younger respondents, the examples are more age appropriate and criteria are changed when there is a corresponding caveat in the DSM-IV for adolescents that is different from adults (for example, in a major depressive episode mood can be predominantly irritable in adolescents rather than sad). However, validation of this instrument is still in process. An important strength of this survey in light of critiques of earlier studies is that impairment is included in the diagnostic criteria and additional measures of severity are employed. We report diagnostic classications based on only one informant, namely, the adolescent. Including parent informants is generally deemed most important for the diagnosis of externalizing disorders and for younger participants, although Jensen and colleagues (1999) found no consistent pattern of factors that mediate parentchild agreement on symptoms and/or diagnoses. On the other hand, the issue of multiple informants for adolescent diagnosis is a complex one in terms of how to deal with discrepancies in informant information as generally low concordance (js often less than .20) is found between parent and child (Edelbrock, Costello, Dulcan, Conover, & Kala, 1986; Jaffee, Harrington, Cohen, & Moftt, 2005). We chose therefore to focus on youth report and thus our ndings should be compared to those studies which report youth-only estimates. This survey only includes adolescents with a xed residence and does not include homeless or institutionalized adolescents, who are likely to have a greater prevalence of mental illness and substance use or abuse. Also, we surveyed only the Mexico City Metropolitan area and our results may not extend to other urban or rural areas of Mexico.

Limitations

While the eld of child/adolescent psychiatric epidemiology has developed several diagnostic instruments for adolescents such as the Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Assessment (CAPA; Angold & Costello, 2000), the Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children (DISC; Shaffer, Fisher, Lucas, Dulcan, & Schwab-Stone, 2000) and the Development and Well-Being Assessment (DAWBA; Goodman, Ford, Richards, Gatward, & Meltzer, 2000) and has scrambled to keep up with nosological revisions, this

Conclusions

Our 8.5% prevalence of severe disorder is similar to the 10.7% prevalence of disorders with impairment reported for Mexican American adolescents by Roberts, Roberts, and Xing (2006), but lower than the 19.6% reported by Shaffer and colleagues (1996) for children and adolescents in the US. Our estimate of moderatemild disorder is higher than the one reported by Roberts and colleagues, but similar to that of Shaffer and colleagues. Several individual disorders have almost identical estimates when comparing

2008 The Authors Journal compilation 2008 Association for Child and Adolescent Mental Health.

Psychiatric disorders in Mexican youth

393

ours with this latter report, such as agoraphobia (3.6% for both), separation anxiety (2.6% vs. 2.7%), major depression (4.8% vs. 3.2%), conduct disorder (3.0% vs. 3.2%), and ADHD (1.6% vs. 1.2%). The disorders that present most discrepancy from other studies are specic and social phobia. The difference between our estimates and the 25% median prevalence estimate (Costello et al., 2005) in developed regions may in part be due to the enormous rate of social change and social adversity, especially in developing countries like Mexico. Rapid social transformations have eroded the basic structures of Mexican culture. Once a traditionally rural society, Mexico has seen a large migration to urban areas, diminishing extended family ties, increases in divorce, income loss, the incorporation of mothers raising young children into the labor force, and the incorporation of children in money-raising activities in the informal sectors of the economy with increased risks for drug abuse and victimization (Medina-Mora, 2000). The population living in the 10% of households with the highest income concentrates 35.6% of the national income, whereas 10% of the poorest concentrates only 1.6% (INEGI, 2002). In 2002, SEDESOL estimated that 26.5% of the population did not have the required income to satisfy their basic nutritional requirements or had limited access to education and health services. The level of education in Mexico has risen, amplifying the communication gap between adults and youths. Finally, globalization has also brought about social changes such as a greater availability of illegal substances, violence related to increased drug trafcking and exposure to values dissonant with those of older generations (Villatoro et al., 2001). The high prevalence estimates for mental illness echo the steady increase in completed suicides during recent decades in Mexico, especially among youth for whom there was a 150% increase among 5- to 14-year-olds and a 74% increase among 15- to 24-year-olds between 1990 and 2000, one of the largest increases among 28 countries (Bridge, Goldstein, & Brent, 2006).

availability of mental health services and mental health providers, and fewer years of obligatory education and thus earlier ages of withdrawal from school. With regards to mental health services and providers, Mexico City has only one child psychiatric hospital, which, in fact, is the only one for the entire country of over 100 million inhabitants. The World Health Organizations (2005) Atlas for Child and Adolescent Mental Health Resources documents that countries with the largest proportion of children and adolescents in the population are the most lacking in specic child and adolescent mental health policies, and lower-income, less developed countries have the least amount of child and adolescent psychiatrists, other mental health professionals and availability of community mental healthcare. Because most adolescents have less contact with general healthcare systems than other age groups, being the most physically healthy sector of society (Patel et al., 2007), the school system is an important resource for mental health detection and referral. However, in Mexico City, like in other developing regions of the world, a greater proportion of adolescents are outside of the reach of the educational system owing to a large proportion of adolescents that no longer attend school. Considering that almost 25% of the adolescent population meets criteria for one or more disorders (not including phobias and reaching almost 40% when included), it is not realistic to think that the current health system could possibly meet this demand if barriers to access were eliminated; despite this, epidemiological data such as these, which demonstrate the magnitude and severity of psychiatric disorders and the service utilization gap, should stimulate health policies to assign a greater priority to the mental health needs of this population and to restructuring mental health services so as to use and distribute the available resources optimally and to reduce barriers to service utilization.

Acknowledgements Public health policy implications

While even in the most developed regions of the world mental health service use in adolescents is limited, this study suggests that mental health service use for adolescents in Mexico is a rarity. While this data cannot speak to causality, this study suggests that low levels of parental education may be one barrier to service utilization, a factor that if indeed causally related has potential for modication and intervention. Possible explanations for the low level of service use in Mexican adolescents might be due to factors which Mexico City shares with other developing regions, namely a large adolescent population with scarce The Mexican Adolescent Mental Health Survey was supported by the National Council on Science and Technology in conjunction with the Ministry of Education (grant No. CONACYT-SEP-SSEDF-2003CO1-22) and by the National Institute of Psychiatry Ramon de la Fuente Mun iz (DIES- 4845). The survey was carried out in conjunction with the World Health Organization World Mental Health (WMH) Survey Initiative. We thank the WMH staff for assistance with instrumentation, eldwork, and data analysis. Finally we wish to acknowledge the assistance of Estela Rojas, Clara Fleiz, Sandra Morales and Alejandro Hernandez in the supervision of eldwork.

2008 The Authors Journal compilation 2008 Association for Child and Adolescent Mental Health.

394

Corina Benjet et al.

Correspondence to

Corina Benjet, National Institute of Psychiatry Ramon de la Fuente. Calzada Me xico Xochimilco 101, Colonia San Lorenzo Huipulco, Mexico D.F. 14370 Mexico; Tel: 52-55-5655-2811 ext. 571; Email: cbenjet@imp.edu.mx

References

American Psychiatric Association. (1994). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-IV), fourth edition. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association. Angold, A., & Costello, E.J. (2000). The child and adolescent psychiatric assessment (CAPA). Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 39, 3948. Belfer, M.L. (2008). Child and adolescent mental disorders: The magnitude of the problem across the globe. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01855.x. Bridge, J.A., Goldstein, T.R., & Brent, D.A. (2006). Adolescent suicide and suicidal behavior. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 47, 37294. Canino, G., Shrout, P.E., Rubio-Stipec, M., Bird, H.R., Bravo, M., Ramirez, R., Chavez, L., Alegria, M., Bauermeister, J.J., Hohmann, A., Riberta, J., Garcia, P., & Martinez-Taboas, A. (2004). The DSM-IV rates of child and adolescent disorders in Puerto Rico: Prevalence, correlates, service use, and the effects of impairment. Archives of General Psychiatry, 61, 8593. Caraveo-Anduaga, J.J. (2007). Cuestionario breve de tamizaje y diagnostico de problemas de salud mental en nin os y adolescentes: algoritmos para s ndromes y su prevalencia en la Ciudad de Me xico [Brief screening and diagnosis of mental health problems in children and adolescentes: Algorithms for syndromes and their prevalence in Mexico City]. Salud Mental, 30, 4855. Costello, E.J., Angold, A., Burns, B.J., Stangl, D.K., Tweed, D.L., Erkanli, A., & Worthman, C.M. (1996). The Great Smoky Mountains Study of Youth: Goals, design, methods and the prevalence of DSM.III.R disorders. Archives of General Psychiatry, 53, 1129 1136. Costello, E.J., Egger, H., & Angold, A. (2005). 10-year research update review: The epidemiology of child and adolescent psychiatric disorders: I. Methods and public health burden. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 44, 972986. Demyttenaere, K., Bruffaerts, R., Posada-Villa, J., Gasquet, I., Kovess, V., Lepine, J.P., Angermeyer, M.C., Bernert, S., de Girolamo, G., Morosini, P., Polidori, G., Kikkawa, T., Kawakami, N., Ono, Y., Takeshima, T., Uda, H., Karam, E.G., Fayyad, J.A., Karam, A.N., Mneimneh, Z.N., Medina-Mora, M.E., Borges, G., Lara, C., de Graaf, R., Ormel, J., Gureje, O., Shen, Y., Huang, Y., Zhang, M., Alonso, J., Haro, J.M., Vilagut, G., Bromet, E.J., Gluzman, S., Webb, C., Kessler, R.C., Merikangas, K.R., Anthony, J.C.,

Von Korff, M.R., Wang, P.S., Brugha, T.S., Aguilar-Gaxiola, S., Lee, S., Heeringa, S., Pennell, B.E., Zaslavsky, A.M., Ustun, T.B., Chatterji, S., & WHO World Mental Health Survey Consortium. (2004). Prevalence, severity, and unmet need for treatment of mental disorders in the World Health Organization World Mental Health Surveys. Journal of the American Medical Association, 291, 25812590. Edelbrock, C., Costello, A.J., Dulcan, M.K., Conover, N.C., & Kala, R. (1986). Parentchild agreement on child psychiatric symptoms assessed via structured interview. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 27, 181190. Fleitlich-Bilyk, B., & Goodman, R. (2004). Prevalence of child and adolescent psychiatric disorders in Southeast Brazil. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 43, 727 734. Ford, T., Goodman, R., & Meltzer, H. (2003). The British child and adolescent mental health survey 1999: The prevalence of DMS-IV disorders. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 42, 12031211. Gau, S.S.F., Chong, M.Y., Chen, T.H.H., & Cheng, A.T.A. (2005). A 3-year panel study of mental disorders among adolescents in Taiwan. American Journal of Psychiatry, 162, 13441350. Goodman, R., Ford, T., Richards, H., Gatward, R., & Meltzer, H. (2000). The Development and Well-being Assessment: Description and initial validation of an integrated assessment of child and adolescent psychopathology. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 41, 645656. Haro, J.M., Arbabzadeh-Bouchez, S., Brugha, T.S., de Girolamo, G., Guyer, M.E., Jin, R., Lepine, J.P., Mazzi, F., Reneses, B., Vilagut, G., Sampson, N.A., & Kessler, R.C. (2006). Concordance of the Composite International Diagnostic Interview Version 3.0 (CIDI 3.0) with standardized clinical assessments in the WHO World Mental Health surveys. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research, 15, 167180. Hosmer, D.W., & Lemeshow, S. (2000). Applied logistic regression, (2nd edn). New York: John Wiley & Sons. INEGI: Instituto Nacional de Estad stica Geograf a e Informa tica. (2002). Encuesta Nacional de Ingresos y Gastos [National survey on Income and Expenditure of Households]. Mexico: INEGI. Jaffee, S.R., Harrington, H., Cohen, P., & Moftt, T.E. (2005). Cumulative prevalence of psychiatric disorder in youth. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 44, 406407. Jensen, P.S., Rubio-Stipec, M., Canino, G., Bird, H.R., Dulcan, M.K., Schwab-Stone, M.E., & Lahey, B.B. (1999). Parent and child contributions to diagnosis of mental disorder: Are both informants always necessary? Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 38, 156979. Kessler, R.C., Angermeyer, M., Anthony, J.C., De Graaf, R., Demyttenaere, K., Gasquet, I., De Girolamo, G., Gluzman, S., Gureje, O., Haro, J.M., Kawakami, N., Karam, A., Levinson, D., Medina Mora, M.E., Oakley Browne, M.A., Posada-Villa, J., Stein, D.J., Adley Tsang, C.H., Aguilar-Gaxiola, S., Alonso, J., Lee, S.,

2008 The Authors Journal compilation 2008 Association for Child and Adolescent Mental Health.

Psychiatric disorders in Mexican youth

395

Heeringa, S., Pennell, B.E., Berglund, P., Gruber, n, T.B. M.J., Petukhova, M., Chatterji, S., & Ustu (2007). Lifetime prevalence and age of onset distributions of mental disorders in the World Health Organizations World Mental Health Surveys. World Psychiatry, 6, 168176. stu n, T.B. (2004). The World Mental Kessler, R.C., & U Health (WMH) Survey Initiative Version of the World Health Organization (WHO) Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI). International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research, 13, 93121. Medina-Mora, M.E. (2000). Abuso de Sustancias [Substance abuse]. In DIF-DF & UNICEF (Eds.), Estudio de venes Trabajadores en el Distrito Nin as, Nin os y Jo Federal [Study of boys and girls that work in the Federal District] (pp. 119137). Mexico: UNICEF. Medina-Mora, M.E., Borges, G., Benjet, C., Lara, C., & Berglund, P. (2007). Psychiatric disorders in Mexico: Lifetime prevalence and risk factors in a nationally representative sample. British Journal of Psychiatry, 190, 521528. Medina-Mora, M.E., Borges, G., Lara, C., Benjet, C., Blanco, J., Fleiz, C., Villatoro, J., Rojas, E., & Zambrano, J. (2005). Prevalence, service use, and demographic correlates of 12-month DSM-IV psychiatric disorders in Mexico: Results from the Mexican National Comorbidity Survey. Psychological Medicine, 35, 17731784. Mexican Ministry of Health & National Council on Addictions. (2002). National survey of addictions 2002. Mexico: Mexican Ministry of Health. Mexican Ministry of Health & National Institute of Psychiatry. (1989). National survey of addictions 1989. Mexico: Mexican Ministry of Health. Mexican Ministry of Health & National Institute of Psychiatry. (1998). National survey of addictions 1998. Mexico: Mexican Ministry of Health. Patel, V., Flisher, A.J., Hetrick, S., & McGorry, P. (2007). Mental health of young people: A global public-health challenge. Lancet, 369, 13021313. Research Triangle Institute. (2002). Sudaan Release 8.0.1. North Carolina: Research Triangle Institute. Roberts, R.E., Roberts, C.R., & Xing, Y. (2006). Prevalence of youth reported DSM-IV disorders among African, European, and Mexican American adolescents. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 45, 13291336.

Sawyer, M.G., Arney, F.M., Baghurst, P.A., Clark, J.J., Graetz, B.W., Kosky, R.J., Nurcombe, B., Patton, G.C., Prior, M.R., Raphael, B., Rey, J.M., Whaites, L.C., & Zubrick, S.R. (2001). The mental health of young people in Australia: Key ndings from the child and adolescent component of the national survey of mental health and well-being. The Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 35, 806814. SEDESOL: Secretar a de Desarrollo Social, Comite te cnico para la medicio n de la pobreza. (2002). n de la Pobreza, variantes metodolo gicas y Medicio n preliminar [Poverty measurement, methodestimacio ologic variants and preliminary estimation]. Mexico: SEDESOL. Shaffer, D., Fisher, P., Dulcan, M.K., Davies, M., Piacentini, J., Schwab-Stone, M.E., Lahey, B.B., Bourdon, K., Jensen, P.S., Bird, H.R., Canino, G., & Regier, D.A. (1996). The NIMH Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children Version 2.3 (DISC-2.3): Description, acceptability, prevalence rates, and performance in the MECA study. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 35, 865877. Shaffer, D., Fisher, P., Lucas, C.P., Dulcan, M.K., & Schwab-Stone, M.E. (2000). NIMH Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children Version IV (NIMH DISC-IV): Description, acceptability, prevalences, and performance in the MECA study. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 39, 2838. Sheehan, D.V., Harnett-Sheehan, K., & Raj, B.A. (1996). The measurement of disability. International Clinical Psychopharmacology, 11, 8995. Villatoro, J., Medina-Mora, M.E., Rojano, C., Fleiz, C., Villa, G., Jasso, A., Alcantar, M.I., Bermu dez, P., & Blanco, J. (2001). Reporte Global [Global report]. Mexico: DIF-SEP. Wittchen, H.U., Nelson, C.B., & Lachner, G. (1998). Prevalence of mental disorders and psychosocial impairments in adolescents and young adults. Psychological Medicine, 28, 109126. World Health Organization. (2005). Atlas: Child and adolescent mental health resources. Geneva: World Health Organization. Manuscript accepted 12 May 2008

2008 The Authors Journal compilation 2008 Association for Child and Adolescent Mental Health.

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- DIfferential Diagnosis Bladder DysfunctionDocument8 pagesDIfferential Diagnosis Bladder DysfunctionAlejandra Márquez CalderónPas encore d'évaluation

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- Sensory Dysfunction and Problem Behaviors in Children With AutismDocument103 pagesSensory Dysfunction and Problem Behaviors in Children With AutismAlejandra Márquez CalderónPas encore d'évaluation

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5794)

- The Art of Narrative PsychiatryDocument227 pagesThe Art of Narrative Psychiatryroxyoancea100% (8)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- The Environment Ans ShizophreniapdfDocument10 pagesThe Environment Ans ShizophreniapdfAlejandra Márquez CalderónPas encore d'évaluation

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (894)

- Family Therapy and Childhood One-Set SchizophreniaDocument15 pagesFamily Therapy and Childhood One-Set SchizophreniaAlejandra Márquez CalderónPas encore d'évaluation

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (399)

- Schizophr Initial PhaseDocument15 pagesSchizophr Initial PhaseAlejandra Márquez CalderónPas encore d'évaluation

- Neg Symp at Risk Mental StateDocument9 pagesNeg Symp at Risk Mental StateAlejandra Márquez CalderónPas encore d'évaluation

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- The New Epistemology and The Milan ApproachDocument17 pagesThe New Epistemology and The Milan ApproachAlejandra Márquez CalderónPas encore d'évaluation

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- The Cruel Radiance of What It IsDocument19 pagesThe Cruel Radiance of What It IsAlejandra Márquez CalderónPas encore d'évaluation

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (587)

- OpenDialog ApproachAcutePsychosisOlsonSeikkulaDocument16 pagesOpenDialog ApproachAcutePsychosisOlsonSeikkulaAlejandra Márquez CalderónPas encore d'évaluation

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (265)

- Neg Symp at Risk Mental StateDocument9 pagesNeg Symp at Risk Mental StateAlejandra Márquez CalderónPas encore d'évaluation

- The Second Cybernetics: Deviation-Amplifying Mutual Causal Processes (Maruyama)Document16 pagesThe Second Cybernetics: Deviation-Amplifying Mutual Causal Processes (Maruyama)telecultPas encore d'évaluation

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (73)

- Is Second Order Practice PossibleDocument11 pagesIs Second Order Practice PossibleAlejandra Márquez CalderónPas encore d'évaluation

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- Chapter 14 Psychological Disorders.Document9 pagesChapter 14 Psychological Disorders.BorisVanIndigoPas encore d'évaluation

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (344)

- Alcoholics With Mental Health Issues: Experience, Strength and HopeDocument48 pagesAlcoholics With Mental Health Issues: Experience, Strength and Hopeeduard joseph resmaPas encore d'évaluation

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- ADHD Diagnosis and Screening in AdultsDocument4 pagesADHD Diagnosis and Screening in AdultsGrzegorz Pelutis0% (1)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- Mood Stablizing AgentsDocument15 pagesMood Stablizing AgentsDhAiRyA ArOrAPas encore d'évaluation

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2219)

- Criminology 5Document32 pagesCriminology 5Allysa Jane FajilagmagoPas encore d'évaluation

- 2.e.case Ctudy On BPADDocument9 pages2.e.case Ctudy On BPADManisa Parida100% (1)

- Frank McGillion - The Pineal Gland and The Ancient Art of IatromathematicaDocument21 pagesFrank McGillion - The Pineal Gland and The Ancient Art of IatromathematicaSonyRed100% (1)

- A Review of Oppositional Defiant and Conduct DisordersDocument9 pagesA Review of Oppositional Defiant and Conduct DisordersStiven GonzalezPas encore d'évaluation

- CPG Management of Bipolar Disorder in AdultsDocument78 pagesCPG Management of Bipolar Disorder in AdultsElvis NgPas encore d'évaluation

- Case Report On Bipolar Affective Disorder: Mania With Psychotic SymptomsDocument3 pagesCase Report On Bipolar Affective Disorder: Mania With Psychotic SymptomsmusdalifahPas encore d'évaluation

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1090)

- Abnormal Psychology: Jeremiah Paul Silvestre, RPMDocument144 pagesAbnormal Psychology: Jeremiah Paul Silvestre, RPMMatt MelendezPas encore d'évaluation

- Research EssayDocument13 pagesResearch Essayapi-609533251Pas encore d'évaluation

- Neurobiology of Bipolar DisorderDocument9 pagesNeurobiology of Bipolar DisorderJerry JacobPas encore d'évaluation

- Esquizofrenia Infantil Guia IAACAPDocument15 pagesEsquizofrenia Infantil Guia IAACAPAdolfo Lara RdzPas encore d'évaluation

- C.E. Sandalcı - ProjectDocument37 pagesC.E. Sandalcı - Projectpopopopppopopopp1Pas encore d'évaluation

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (119)

- Mental Health and Mental Disorders-A Rural ChallenDocument18 pagesMental Health and Mental Disorders-A Rural Challenpratiksha ghobalePas encore d'évaluation

- ECTDocument11 pagesECTmanu sethi75% (4)

- Unit Plan ContentDocument9 pagesUnit Plan ContentS KANIMOZHIPas encore d'évaluation

- Common Psychiatric DisordersDocument3 pagesCommon Psychiatric DisordersWaheedullah AhmadiPas encore d'évaluation

- Mental Status ExamDocument10 pagesMental Status ExamSrini VoruPas encore d'évaluation

- SWAP-200 ClassificaçãoDocument12 pagesSWAP-200 ClassificaçãoJéssica De Oliveira ViveirosPas encore d'évaluation

- MOOD DISORDERS GUIDEDocument20 pagesMOOD DISORDERS GUIDESurya BudikusumaPas encore d'évaluation

- Guide For Caregivers PDFDocument65 pagesGuide For Caregivers PDFAlif HasbullahPas encore d'évaluation

- Nes Mental Pharmacy - FinalDocument271 pagesNes Mental Pharmacy - FinalJ Carlos ChambiPas encore d'évaluation

- Mood Disorders and SuicideDocument6 pagesMood Disorders and SuicideCalli AndersonPas encore d'évaluation

- Adulthood & Geriatric PsychiatryDocument13 pagesAdulthood & Geriatric PsychiatryPernel Jose Alam MicuboPas encore d'évaluation

- Bipolar Affective DisorderDocument17 pagesBipolar Affective DisorderEmilie PlacePas encore d'évaluation

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)

- The Schizoaffective Disorder DiagnosisDocument5 pagesThe Schizoaffective Disorder DiagnosisLindha Gra100% (1)

- Effects of Music Therapy On Mood in Stroke Patients: Original ArticleDocument5 pagesEffects of Music Therapy On Mood in Stroke Patients: Original ArticleNURULPas encore d'évaluation

- Philippine Nursing Licensure ExaminationDocument32 pagesPhilippine Nursing Licensure ExaminationVera100% (1)

- Summary: The Myth of Normal: Trauma, Illness, and Healing in a Toxic Culture By Gabor Maté MD & Daniel Maté: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisD'EverandSummary: The Myth of Normal: Trauma, Illness, and Healing in a Toxic Culture By Gabor Maté MD & Daniel Maté: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (9)