Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Wallace Stevens' obsession with the human imagination

Transféré par

kanchu007Titre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Wallace Stevens' obsession with the human imagination

Transféré par

kanchu007Droits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

The human imagination, the ability to perceive another kind of reality made purely of thought, has always been

the muse of artists and writers alike. Poets especially prize this human ability to imagine and create because it is the essence of their work, both for the poet himself and the reader. However, no contemporary poet can be said to have admired the imagination more than Wallace Stevens. Several of his poems are written specifically on the subject of the imagination, oftentimes deifying it as if it were a god in itself. Through the study of Stevens' poems, essays, and articles, one can find reasons behind his obsession and the ways in which he uses poetic techniques to express his ideas. Wallace Stevens' The Palm at the End of the Mind: Selected Poems and a Play is a collection of Stevens' poems, many of which deal with the issues of imagination verses reality, such as "The Men that are Falling," "The Final Soliloquy of the Interior Paramour," and "Angel Surrounded by Paysans." In the chapter of a book by Robert Rehder, entitled "My Reality-imagination Complex," Rehder explains that Stevens' works are a "diagnosis of his 'reality-imagination' complex" (Rehder 150). The poems express his views on the place of the imagination within reality, its relationship with reality, and his views on the definition of what reality truly is; is it what we sense and can measure, or is it mixed up with the subconscious, dreams, and preconceived notions. He writes that "for each individual the imagination comes first and the world afterwards...The baby...dwells in a fantasy realm that is transformed only gradually into reality...This mutually enriching interplay between imagination and reality is the process that creates the self-and art" (Rehder 133). This explains how, for Stevens, the imagination and reality were two parts of a whole; one without the other would not be sufficient enough to move a reader. Poetry, in Stevens' view, had to be written with a "double subject;" one subject would be based in reality and would be something tangible the reader could relate to or fixate upon, while the other would be a string of the imagination, some abstract portion that carries the reader beyond the mere facts of the thing's reality to a deeper meaning. Rehder believes that Stevens was not always successful at writing with a double subject, but that it was what Stevens strove for as his goal throughout all of his work (Rehder 137). Stevens' poetry, however, went beyond merely writing about the imagination and its relation to reality. His poetry oftentimes deified the imagination, raised it up above the usual psychoanalytic view of it, and transformed it into something more divine. In several poems he does this. In "The Men that are Falling," Steven's writes "Taste the blood upon his martyred lips, O pensioners, O demagogues and pay-men! This death was his belief though death is a stone.

This man loved earth, not heaven, enough to die. The night wind blows upon the dreamer, bent Over words that are life's voluble utterance" (Stevens, Holly 130). Stevens describes a martyr that died for his love of earth and of dreams. He presents a secular view of the martyr, and yet, by dying for dreams, the martyr makes the dreams mean more than mere fancies. The last two lines tell the reader what the man in the poem was doing as he died; he was dreaming or imagining, "bent over words that are life's voluble utterance," which could be interpreted to mean poetry or the Bible since Stevens refers to "God and all angels" being the man's desire . Stevens presents poetry and the imagination as something to die for, and something that one can become a martyr for. By this, Stevens compares God to the imagination, using the term normally applied to someone who dies for God, and applying it to a secular ideal. This idea of the deified imagination goes on in Stevens' "Final Soliloquy of the Interior Paramour." In this poem, Stevens presents images that call up dreams, imaginings, wistful fancies, and then clearly and bluntly states what he has been hinting at all through his poems, that "God and the imagination are one" (Stevens, Holly 368). Through his poems, Stevens has taken the art of poetry, which had become so secular during the time of his writing, and brought God back into it. However, the God Stevens fills his poetry with is not the one of Tennyson or Browning; it is the imagination itself. In "Angel Surrounded by Paysans," Stevens personifies reality in the form of an angel and hints at its relationship to the imagination. He describes it as more fleeting than dreams, and yet the angel says, "I am the necessary angel of earth," meaning that, though Stevens seems to focus on the imagination and even deifies it, he recognizes a need for reality in poetry and in life and asserts his goal for a harmonious blending of the two in his poetry (Stevens, Holly 354). Daniel Funchs, in The Comic Spirit of Wallace Stevens, writes, "The peculiar magic of the imagination is that, through it, life's dimensions become more specific while becoming more mysterious" (Funchs 112).Funchs' assertion is one that embodies Stevens' view on the coexistence that needs to be between reality and the imagination; each influences the other. As much as Stevens was concerned about the reality-imagination relationship in his poetry, he was also conscious of his use of language to express that relationship. In "Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Blackbird," the sections of the poem are a mix of the concrete image of the blackbird and an almost playful series of words and images. The reader has to almost struggle to make sense of each section, to hunt for the reason behind the blackbird being present in a seemingly unrelated grouping of phrases. This argument forces the imagination to come up with some veritable explanation or way of working the two parts together, and yet it seems that Stevens focused more on the overall aesthetic feeling of the poems rather than whether or not they made logical sense (Stevens, Holly 20). In essence, Stevens combines the

imagination with the concrete, creating an overall feeling that he sees as the goal of poetry. Through his admiration for the human ability to imagine, to live in two realities, and his attempts to deify the imagination, Stevens is remembered through his poetry. His use of words and images that seek to blend the imagined and the concrete makes him the great modern poet he is recognized to be. These qualities of his poetry are recognized as belonging completely and uniquely to Stevens. Even Stevens himself recognizes the uniqueness of what he has tried to accomplish in his poetry. Rehder quoting Stevens from July 21st 1953 writes "While, of course, I come down from the past, the past is my own and not something marked Coleridge, Wordsworth, etc. I know of no one who has been particularly important to me. My reality-imagination complex is entirely my own even though I see it in others (Rehder 133). Steven's unique views and works make him a modern poet worthy of study and enjoyment by all readers who pick up his books. Stevens' poems are a doorway into his imagination and to the imagined worlds within each reader's mind.

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- Extraordinary Inns & TavernsDocument45 pagesExtraordinary Inns & Tavernskopigix100% (4)

- 6th Central Pay Commission Salary CalculatorDocument15 pages6th Central Pay Commission Salary Calculatorrakhonde100% (436)

- Tintern Abbey by William WordsworthDocument3 pagesTintern Abbey by William WordsworthMarina Vasilic0% (1)

- Vulfpeck - Hero TownDocument2 pagesVulfpeck - Hero TownyellowsunPas encore d'évaluation

- House Arrest Teacher GuideDocument4 pagesHouse Arrest Teacher GuideChronicleBooksPas encore d'évaluation

- Wei Kuen Do PDFDocument7 pagesWei Kuen Do PDFAnimesh Ghosh100% (1)

- Wordsworth'Document9 pagesWordsworth'Flovek FayazPas encore d'évaluation

- What Makes A Woman An AmazonDocument10 pagesWhat Makes A Woman An AmazonMia ČomićPas encore d'évaluation

- Gould - History of Freemasonry Throughout The World Vol. 2 (1936)Document469 pagesGould - History of Freemasonry Throughout The World Vol. 2 (1936)Giancarlo ZardoPas encore d'évaluation

- Among School ChildrenDocument8 pagesAmong School ChildrenBasila HananPas encore d'évaluation

- Nissim Ezekiel's Poetry Collection Focuses on Finding Precise ImagesDocument7 pagesNissim Ezekiel's Poetry Collection Focuses on Finding Precise ImagesG nah jg Cgj he xPas encore d'évaluation

- Man With The Hoe DLLDocument4 pagesMan With The Hoe DLLSelle QuintanoPas encore d'évaluation

- Basic News WritingDocument7 pagesBasic News WritingKaren VerónicaPas encore d'évaluation

- Yeats' Poetry and the Significance of DesireDocument3 pagesYeats' Poetry and the Significance of DesireYoussef Latash100% (1)

- Metaphysical Poetry and JohnDocument14 pagesMetaphysical Poetry and JohnsabeeqaPas encore d'évaluation

- Maya Yoga - Finding Comfort and Ease in EnchantmentDocument6 pagesMaya Yoga - Finding Comfort and Ease in Enchantmentkanchu007100% (1)

- Wordsworth and Coleridge On ImaginationDocument4 pagesWordsworth and Coleridge On ImaginationNoor AnandPas encore d'évaluation

- Deleuze-What Is A DispositifDocument7 pagesDeleuze-What Is A DispositifDaniel RedPas encore d'évaluation

- About Poems and how poems are not about: and how poets are not aboutD'EverandAbout Poems and how poems are not about: and how poets are not aboutPas encore d'évaluation

- Bstract: The Poetic Bliss of The Re-Described Reality: Wallace Stevens: Poetry, Philosophy, and The Figurative LanguageDocument10 pagesBstract: The Poetic Bliss of The Re-Described Reality: Wallace Stevens: Poetry, Philosophy, and The Figurative LanguageJoaquín LanzaPas encore d'évaluation

- WS MeditationDocument1 pageWS MeditationMariana Niculae100% (1)

- More Than RationalDocument9 pagesMore Than RationaldlaveryPas encore d'évaluation

- Wallace Stevens' exploration of imagination and realityDocument10 pagesWallace Stevens' exploration of imagination and realityFizza RaufPas encore d'évaluation

- Wallace Stevens' Poetry and Criticism ExploredDocument8 pagesWallace Stevens' Poetry and Criticism Explored周晓鸥Pas encore d'évaluation

- Gardner Wallace Stevens EJPDocument23 pagesGardner Wallace Stevens EJPsebastian_gardnerPas encore d'évaluation

- The Role of Nature in The Poetry of William WordsworthDocument4 pagesThe Role of Nature in The Poetry of William WordsworthJahan AraPas encore d'évaluation

- Wordsworth and Coleridge: Emotion, Imagination and Literary ImpactDocument7 pagesWordsworth and Coleridge: Emotion, Imagination and Literary ImpactAqeel SarganaPas encore d'évaluation

- Metaphysical Poetry-An Introduction: Vol. 2 No. 2 March, 2014 ISSN: 2320 - 2645Document7 pagesMetaphysical Poetry-An Introduction: Vol. 2 No. 2 March, 2014 ISSN: 2320 - 2645Mahmud MohammadPas encore d'évaluation

- An Aristotelian Analysis of Rabbit As King of The Ghosts by Wallace StevensDocument3 pagesAn Aristotelian Analysis of Rabbit As King of The Ghosts by Wallace StevensRenata ReichPas encore d'évaluation

- Romantic Poet - Role of ImaginationDocument4 pagesRomantic Poet - Role of ImaginationJenif RoquePas encore d'évaluation

- The Plain Sense of Things Poetry Response 1Document3 pagesThe Plain Sense of Things Poetry Response 1api-532345184Pas encore d'évaluation

- Romantic Poetry - Analysis of Wordsworth Poetry by M-Azeem YaseenDocument3 pagesRomantic Poetry - Analysis of Wordsworth Poetry by M-Azeem YaseenAzeem100% (2)

- Tinternabbey: William WordsorthDocument9 pagesTinternabbey: William WordsorthFayyaz Ahmed IlkalPas encore d'évaluation

- Lyric NoteDocument74 pagesLyric NoteBelle LingPas encore d'évaluation

- Theories of LiteratureDocument19 pagesTheories of LiteratureIsti Qomariah100% (1)

- Stevens' "The Emperor of Ice-Cream"Document5 pagesStevens' "The Emperor of Ice-Cream"Vishnu DasPas encore d'évaluation

- Wordsworth and Coleridge's Views on ImaginationDocument4 pagesWordsworth and Coleridge's Views on ImaginationNoor100% (1)

- This Goes Back in Time From The Text We Were Discussing LastDocument10 pagesThis Goes Back in Time From The Text We Were Discussing Lasta_perfect_circlePas encore d'évaluation

- Wallace Stevens and Aesthetic RepresentaDocument14 pagesWallace Stevens and Aesthetic RepresentaКатерина УхнальPas encore d'évaluation

- Department of Social Science: Bs English Linguistics & Literature Romantic PoetryDocument5 pagesDepartment of Social Science: Bs English Linguistics & Literature Romantic PoetryFatima MunawarPas encore d'évaluation

- Writing and LiteratureDocument3 pagesWriting and Literatureryan paynePas encore d'évaluation

- Wordsworth QuestionsDocument5 pagesWordsworth QuestionsArshad Nawaz JappaPas encore d'évaluation

- Nietzsches Shakespeare Musicality and HiDocument20 pagesNietzsches Shakespeare Musicality and HiMiguel HMPas encore d'évaluation

- Criticism AssDocument3 pagesCriticism AssAsmaul HousnaPas encore d'évaluation

- Ode_on_intimations_of_immortality_ADocument16 pagesOde_on_intimations_of_immortality_AKRITI RAJPas encore d'évaluation

- On John Ashbery's Poetic VoiceDocument16 pagesOn John Ashbery's Poetic VoiceJohn RosePas encore d'évaluation

- John Donne As A Metaphysical PoetDocument5 pagesJohn Donne As A Metaphysical PoetKomal Kamran100% (5)

- Jungian Imagination in Wordsworth’s PoetryDocument8 pagesJungian Imagination in Wordsworth’s PoetryNick JudsonPas encore d'évaluation

- Running Head: Writing and Literature 1Document3 pagesRunning Head: Writing and Literature 1ryan paynePas encore d'évaluation

- Aesthetic Debate in Keats's Odes PDFDocument8 pagesAesthetic Debate in Keats's Odes PDFSiddhartha Pratapa0% (1)

- Ma NoteDocument7 pagesMa NotesindhupandianPas encore d'évaluation

- Deman Paper - TreyDocument8 pagesDeman Paper - TreyBushra MumtazPas encore d'évaluation

- Imagination and FancyDocument3 pagesImagination and Fancyfaisal jahangeerPas encore d'évaluation

- Nature in Wordsworth and Shelley's PeotryDocument13 pagesNature in Wordsworth and Shelley's PeotryMuhammad SufyanPas encore d'évaluation

- Chapter 03 paper 01Document10 pagesChapter 03 paper 01Akanksha MahobePas encore d'évaluation

- Redress of Poetry 2Document7 pagesRedress of Poetry 2L'Aurore100% (1)

- Tradition and The Individual TalentDocument9 pagesTradition and The Individual TalentMonikaPas encore d'évaluation

- "Poetry Is The Spontaneous Overflow of Powerful Feelings "Document3 pages"Poetry Is The Spontaneous Overflow of Powerful Feelings "Mr. AlphaPas encore d'évaluation

- John Donne A Metaphysical PoetDocument4 pagesJohn Donne A Metaphysical Poetajjigujjar50% (2)

- Critical Analysis ofDocument7 pagesCritical Analysis ofskylightlightPas encore d'évaluation

- Stevens A Study of The Two PearsDocument4 pagesStevens A Study of The Two Pearsana_maria_nichita5708Pas encore d'évaluation

- Wordsworth-Preface To The Lyrical BalladsDocument19 pagesWordsworth-Preface To The Lyrical BalladsIan BlankPas encore d'évaluation

- Death in Venice by Thomas MannDocument7 pagesDeath in Venice by Thomas ManncsepelyaPas encore d'évaluation

- Walt Whitman and TranscedentalismDocument3 pagesWalt Whitman and TranscedentalismNauman MashwaniPas encore d'évaluation

- Interpretations of Poiesis and ReligionDocument27 pagesInterpretations of Poiesis and ReligionAlma LvPas encore d'évaluation

- W B. Yeats's "A Prayer For My Daughter": The Ironies of The Patriarchal StanceDocument11 pagesW B. Yeats's "A Prayer For My Daughter": The Ironies of The Patriarchal StanceMuguntharajan SuburamanianPas encore d'évaluation

- The Romantic Unityof Keats' OdesDocument7 pagesThe Romantic Unityof Keats' OdesanitaPas encore d'évaluation

- UntitledDocument2 pagesUntitledmdey999Pas encore d'évaluation

- Conceits in Donne S PoetryDocument2 pagesConceits in Donne S PoetryjhondonnePas encore d'évaluation

- 4329 Load SheddingDocument3 pages4329 Load SheddingIno GalPas encore d'évaluation

- Murakami ReviewDocument3 pagesMurakami Reviewkanchu007Pas encore d'évaluation

- You Are Not Your ThoughtsDocument4 pagesYou Are Not Your Thoughtskanchu007Pas encore d'évaluation

- RumiDocument2 pagesRumikanchu007Pas encore d'évaluation

- ChicagoDocument2 pagesChicagokanchu007Pas encore d'évaluation

- Compare Huawei P40 Lite Vs Huawei P30 Lite Vs Huawei Y9 Prime 2019. RAM, Camera, Price & Specs Comparison - WhatMobileDocument2 pagesCompare Huawei P40 Lite Vs Huawei P30 Lite Vs Huawei Y9 Prime 2019. RAM, Camera, Price & Specs Comparison - WhatMobileAdeel AnjumPas encore d'évaluation

- Steedman 11Document24 pagesSteedman 11RolandoPas encore d'évaluation

- Case Studies NL37Document1 pageCase Studies NL37laura alonsoPas encore d'évaluation

- Kings, Farmers and Towns: By: Aashutosh PanditDocument27 pagesKings, Farmers and Towns: By: Aashutosh PanditIndu sharmaPas encore d'évaluation

- Lalitha Pancharatnam StotramDocument2 pagesLalitha Pancharatnam StotramAbhishek P BenjaminPas encore d'évaluation

- 3d Artist New CVDocument1 page3d Artist New CVMustafa HashmyPas encore d'évaluation

- 2 Julie Is An Engineer / A Chef. 3 Julie Is From Italy / AustraliaDocument10 pages2 Julie Is An Engineer / A Chef. 3 Julie Is From Italy / AustraliaJosé Ezequiel GarcíaPas encore d'évaluation

- Languages of the PhilippinesDocument1 pageLanguages of the PhilippinesHannah LPas encore d'évaluation

- Disputers of The Tao-Kwong-Loi ShunDocument4 pagesDisputers of The Tao-Kwong-Loi Shunlining quPas encore d'évaluation

- Abellana, Modernism, Locality-PicCompressedDocument70 pagesAbellana, Modernism, Locality-PicCompressedapi-3712082100% (5)

- Mapeh 1 With TOSDocument7 pagesMapeh 1 With TOSMary rosePas encore d'évaluation

- Restoration of The Basilica of ConstantineDocument73 pagesRestoration of The Basilica of Constantinetimmyhart11796Pas encore d'évaluation

- Katame WazaDocument3 pagesKatame WazaangangPas encore d'évaluation

- Technical Drawing and Computer Graphics Technical Drawing and Computer GraphicsDocument15 pagesTechnical Drawing and Computer Graphics Technical Drawing and Computer Graphicsprica_adrianPas encore d'évaluation

- PM Control Systems, Singapore Training Centre 201 6 Training ScheduleDocument1 pagePM Control Systems, Singapore Training Centre 201 6 Training ScheduleMuh RenandaPas encore d'évaluation

- Keith Sweat v. Kedar Complaint PDFDocument13 pagesKeith Sweat v. Kedar Complaint PDFMark JaffePas encore d'évaluation

- Advertising in Selling Real Estate by C.C.C. TatumDocument7 pagesAdvertising in Selling Real Estate by C.C.C. Tatumreal-estate-historyPas encore d'évaluation

- Froi of The Exiles The Lumatere Chronicles by Melina Marchetta - Discussion GuideDocument2 pagesFroi of The Exiles The Lumatere Chronicles by Melina Marchetta - Discussion GuideCandlewick PressPas encore d'évaluation

- Module 1: Understanding PhilosophyDocument3 pagesModule 1: Understanding PhilosophyJoyce Dela Rama JulianoPas encore d'évaluation

- WindowsDocument2 pagesWindowsafiq91Pas encore d'évaluation

- Concept Car With GM and Frank O. GehryDocument32 pagesConcept Car With GM and Frank O. GehryFabian MosqueraPas encore d'évaluation

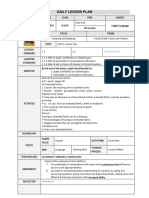

- Daily Lesson Plans for English ClassDocument15 pagesDaily Lesson Plans for English ClassMuhammad AmirulPas encore d'évaluation

- File ListDocument42 pagesFile ListVasiloi RobertPas encore d'évaluation

- Summary of The Eye Have ItDocument4 pagesSummary of The Eye Have Itapi-263501032Pas encore d'évaluation