Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Metamorphosis of Medellín - Joost de Bont - 19032013

Transféré par

Joost de Bont0 évaluation0% ont trouvé ce document utile (0 vote)

29 vues34 pagesMaster of Architecture Thesis on the historical development of Medellín in the last decades with a special focus on slum upgrading practices and a comparetive study of Bogotá.

Titre original

Metamorphosis of Medellín_Joost de Bont_19032013

Copyright

© Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Formats disponibles

PDF, TXT ou lisez en ligne sur Scribd

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentMaster of Architecture Thesis on the historical development of Medellín in the last decades with a special focus on slum upgrading practices and a comparetive study of Bogotá.

Droits d'auteur :

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Formats disponibles

Téléchargez comme PDF, TXT ou lisez en ligne sur Scribd

0 évaluation0% ont trouvé ce document utile (0 vote)

29 vues34 pagesMetamorphosis of Medellín - Joost de Bont - 19032013

Transféré par

Joost de BontMaster of Architecture Thesis on the historical development of Medellín in the last decades with a special focus on slum upgrading practices and a comparetive study of Bogotá.

Droits d'auteur :

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Formats disponibles

Téléchargez comme PDF, TXT ou lisez en ligne sur Scribd

Vous êtes sur la page 1sur 34

1

The Metamorphosis of Medelln

From narcotra c capital to city of ourishing civic culture

Architectural History Thesis [AR2A010] by Joost de Bont | spring 2013

Faculty of Architecture | Del University of Technology

2

Cover photo: Cityscape of Medelln; some rights reserved by David Pea (DavidPLP under a Creave Commons license)

Source: hp://www.ickr.com/photos/davidpenal/350023280

3

Contents 3

Introducon 5

Urban history 7

Medelln as a Lan American case 7

City of violence 7

Illegal land tenure and the right to the city 9

Narco tra c, paramilitaries, guerrillas and polics 11

Spaally fragmented city and globalizaon 13

The transformaon 17

Reinvenon of Colombian civic pride 17

The example of capital Bogot 17

Civic pride of the bogotanos 19

The renaissance of Medelln 21

Metrocable 23

Public libraries and other amenies 25

Cultura ciudadana 27

Conclusions 29

Bibliography 30

4

5

Introducon

The city of Medelln, the second largest city of Colombia, has gone through some decades of major

change. What was once one of the most dangerous and deadly cies in the world and home to one of the

biggest criminals in the recent world history, Pablo Escobar, is now one of the Lan American cies with

the highest annual economic growth rate (McKinsey Global Instute, 2011). This is not only the eect of

the decreasing homicide rate and declining narcotra c. The urban governance of Medelln has improved

a lot since the beginning of the ninees of the last century, together with the fact that the municipal

government has become more stable over me (Marn and Corrales 2011, p. 30). Partly due to this an

integral improvement plan for the whole city, including the highly precarious slums in the outskirts of the

city, was established and is now being executed bit by bit. The main idea of this thesis will be to explain

how Medelln ended up to be the most violent city of its connent and how it aerwards miraculously

escaped from this posion.

The menoned improvement plan was partly based on the one that is iniated in the Colombian

capital Bogot. One of the main objecves of this plan is to increase labour mobility by improving access

to public transport. Labour mobility can be seen as one the most important ways to improve the socio-

economic status of people living in underdeveloped areas, as economist Jeremy Riin stretches in his

book The Age of Access (2000). Next to that a tendency emerged of improving civic culture by construcng

public buildings and making educaon and culture accessible for the people from all dierent strata in the

city.

To describe this transion in a proper way, rst the preceding history of Medelln will be dealt

with. This part on the early history will mainly deal with the socio-economic and urban issues during the

tweneth century, which leaded to the notorious status of being the drug cartel capital of the eighes.

Aer that the era in which the city changed towards the (more successful) metropolitan area that it is now

will be described. This deals with both socio-economic and governance issues, as well as the planning and

urbanism aspects of the improvement plan.

In order to place this urban improvement and slum upgrading project in the context of similar

ones, the Medelln case will be compared with the case of Bogot. Where necessary there will be referred

as well to other Lan American cies and improvement projects. This all to explain the process of major

posive change that took place in Medelln, which was described by journalist Sara Miller Llana as follows:

a combinaon of urban planning at the local level, security at the federal level, and a truce among gangs

on the ground has given rise to what some say is no less than a miraculous transformaon. (2010).

6

Figure 1. Lan American cies round 1900, Medelln with about 50,000 inhabitants (Fernndez-Maldonado 2011)

Figure 2. Evoluon of Lan American cies in general with boom from 1950s on (CEDLA 2008)

Figure 3. Urban populaon in Lan American and annual growth (Fernndez-Maldonado 2011)

7

Urban history

Medelln as a Lan American case

Lan American cies to a great extent share their early urban history. This shared historic is mostly

based on the total Iberian colonizaon of this part of the world. The shared history is even more evident

within the big Hispanic part of the connent. In the inial years of European colonizaon new cies were

founded as centres of mine extracon or near indigenous selements. From 1540 to the end 16th century

the highest peak of European expansion was reached. From 1600 to the mid 19th century there was a

period of slow change (Fernndez-Maldonado 2011). By than cies funconed as nodes of marime and

land routes. These cies were based on the classic Hispano American colonial model, mostly recognized

by a strong grid structure. Up unl far in the tweneth century most of the cies kept following this

inial structure when spreading out over the surrounding area. Starng in the nineeth century the rst

urbanizaon wave spread over the connent (see gure 1 and 2). By the end of this century Medelln was

sll a rather small city with around 50,000 inhabitants (gure 1).

The period from the 1950s on ll 1980 can be mostly characterized by high rates of industrializaon and

urbanizaon, which leaded to heightened urban primacy and populaon concentraons (see gure 3).

Next to the growth of industrial centers, proliferaon of squaer selements took place. This resulted in

an increasing dierenaon between the formal and the informal parts of the cies in Lan America.

In the upcoming period, from 1980 on, a new demographic and economic context came into

existence, a new hierarchy of cies in terms of their global economic integraon (Fernndez-Maldonado

2011). Next to that a diversicaon of naonal urban systems began. A second wave of sub urbanizaon,

mainly symbolized by the fragmentaon into islands of wealth, preceded by road and telecommunicaon

networks (Caldeira 1996). This urban (spaal) fragmentaon has an immense impact on the relaon

between dierent strata in the urban society. It creates tremendous tensions in the city, which can be

menoned in both daily street life as well as in polics. This was as well one of the main reasons that

Medelln became the highly problemac city that it was.

City of violence

If we look closer into the situaon of Medelln and the rest of Colombia, we see that during the ies

and the sixes mass immigraon was caused by polical violence taking place in the country side. In the

period of me from 1948 ll 1953, oen referred to as La Violencia (The Violence), a civil war took place

and one the most crical periods in Medellns history commenced (Marn and Corrales 2011, p. 36).

Even though this le an immense scar, the 1950s, 60s and 70s were decades of prosperity. This prosperity

leaded to an immense growth of the city, as in most of the other Lan American cies, which can be

seen as well in gure 4 and 5. This created together with the emerging polical balance, because of the

Frente Naonal coalion being in charge, hope and a posive vision for the future (Marn and Corrales

2011, p. 36). This is also visible in high amount of instuonal and public buildings being constructed

and educaonal organizaons and private businesses being founded in this period. In this period also

the expansion limits of the city were reached, also see gure 4. The slums on the slopes around the city

covered the whole ring surrounding the metropolitan area in all possible direcons. As a result of this the

only soluon was to grow in the vercal direcon, this mainly happened with residenal buildings in the

city centre, the construcon of the business district and the together with them constructed new avenues.

Next to that Medelln became pioneer in the industrializaon process and development of the country.

But nevertheless the city started declining round about the start of the 80s, and was confronted with a

wide range of violence, fear and terror (Marn and Corrales 2011, p. 36).

Aerwards the degeneraon of the rural economy leaded to an ongoing migraon ow to the

city. At a high pace, in a few decades, Medelln was transformed from a small agricultural based city with

a few hundred thousand inhabitants to a metropolitan area of millions of people. As the main character

Fernando in the movie La Virgen de los Sicarios (1999) explains as well: Medelln was one big farm with

a bishop. The on during mass immigraon together with a governmental incapability of dealing with it

resulted in the complex urban reality of rebellion, criminality and inequality. What made the situaon

even worse was the fact that corrupon started to penetrate into essenal state enes (Marn and

8

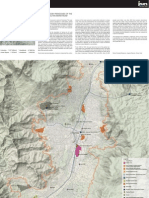

Figure 6. Locaon of pirata and invasione selements with contract forms used (Restrepo Cadavid 2009, p. 47/74, edited by

author)

invasione seulemenLs

formal seulemenLs

oral conLacL

wrluen conLracL

pirata seulemenLs

Figure 4. Expansion of Medelln in the period 1950-2000 (Hernandez Palacio 2012, p.107, edited by author)

Figure 5. Populaon growth of Medelln in the period 1905-2008 (Marn and Corrales 2011, p. 42, edited by author)

1

9

0

5

1

9

1

2

1

9

1

8

1

9

2

8

1

9

3

8

1

9

5

1

1

9

6

4

1

9

7

3

1

9

8

5

1

9

9

3

2

0

0

5

2

0

0

8

5

9

.

8

1

5

7

0

.

5

4

7

7

9

.

1

4

6

1

2

0

.

0

4

4

1

6

8

.

2

6

6

3

5

8

.

1

8

9

7

7

2

.

8

8

7

1

.

0

7

7

.

2

5

2

1

.

4

6

8

.

0

8

9

1

.

6

3

0

.

0

0

9

2

.

2

2

3

.

0

7

8

2

.

3

1

4

.

9

7

3

500.000

1.000.000

1.500.000

2.000.000

2.500.000

opulauon of Medellln (1905-2008)

9

Corrales 2011, p. 38). These corrupt acvies were mainly nanced out of narcotra c, which was also

noceable in the fact that cartel leaders had immense (polical) power. A good example of this last point

are the polical ambious of Pablo Escobar, supported by the enormous inuence that he had on the

lower social class of the urban society (Pescados de mi padre 2009). Escobar mainly gained this inuence

by invesng the money from the narcotra c partly into the housing of this lower social class and by this

creang support for his ideas.

During the eighes and the early ninees migraon to the city happened mostly due to the

growing inuence of armed guerrilla groups and drug cartels (Pao 2011). This all leaded to an enormous

growth of informal selements in the unorganized and hardly unreachable sloped outskirts of the city.

As a result the inhabitants of these informal neighbourhoods or shantytowns had no link to the city;

nor physically (in sense of infrastructure), nor culturally (they did not feel like part of the city, cizens

of Medelln), they missed the feeling of being part of the civic culture. The people that moved from the

country side to the illegal occupied hill sides; exchanged being in a civil war within the rural area for

a maybe even more insecure situaon in the city periphery. A situaon that was controlled by armed

guerrilla groups, organized narcotra c groups and paramilitary groups that had as well big inuence on

the polical situaon of the city. In order to analyze all the dierent aspects that are menoned before

and the ones that contributed as well to the highly fragmented and problemac urban structure, they will

be described separately in the upcoming parts.

Illegal land tenure and the right to the city

One of the things that was not discussed before in this text, but is of a great importance regarding

the problemac growth of the city, is the issue of land tenure. The land that the slum dwellers use is not

their legal property; they occupied a piece of (mostly) state property.

More nuanced there is a disncon to be made between invasiones, when families illegally

occupy land by construcng a house; and pirata, which exists of landowners or promoters illegally selling

plots to people where they will build their houses (Baross and Mesa 1986, p. 153). Mainly the laer is

interesng to look deeper into. The land prices of the plots as they were oered by pirata developers

where rather low, as a result they ourished from the end of the 1960s onwards. One of the main

objecves of these developers was not so much to help these low class people having their own house. In

stead of that they used this process in order to force the government to invest in minimum infrastructural

development of these areas (Baross and Mesa 1986, p. 155). This land tenure speculaon mainly took

place in the zone between the predominantly at inner city (which was commercially more interesng to

develop); and the steep surrounding hills that are mostly occupied by the invasione selements. Aer the

infrastructure was deployed, the pirata developers removed the low income dwellers and their houses

from the land and further (commercially) developed these areas. This clearly shows the underdog role

that the slum dwellers were put into, and as a result that the inhabitants of these areas lacked the right to

the city.

This instable basis on which the slum dwellers balance is as well for a big part the result of the

fact that most of the concluded contracts are based on an oral agreement (see also gure 6) and thus

relavely easy to misuse. Selers with an oral contract have in this case a bigger change of being evicted

from their house (Restrepo Cadavid 2009, p. 80). With regards to this it is interesng to add that in these

informal selements, although based on illegal acvies, there is such a thing as a real estate market in

which trading of housing units takes place. Just like in other Lan American cies with big percentages

of informal selements, like So Paulo in Brazil, this mostly takes place aer a certain neighbourhood is

already consolidated for a certain me (Dias Tamborino 2011, p. 11).

The pirata development greatly declined aer 1970 although sll present (see gure 6),

but aer this the invasione sites kept on emerging (Baross and Mesa 1986, p. 156). These invasione

neighbourhoods consist of even more unfortunate inhabitants, since they are even less wealthy than the

people in the pirata neighbourhoods. The result of this is that these sites are in even more dangerous and

underdeveloped status.

It was only from ninees of the last century on that improvement plans for these neighbourhoods

started to be developed, and that these issues gained polical importance (Marn and Corrales 2011, p.

42). Before that, these urban regions were basically denied, did not exist on both geographical maps and

10

1

9

3

.

2

0

5

3

.

3

9

6

0

.

4

4

2

4

.

5

9

4

3

.

6

1

8

8

.

5

6

2

5

.

5

7

7

7

.

4 9

5

1

.

4

3

5

8

.

3

4

4

1

.

3

8

9

9

.

2

9

5

2

.

3

8

5

1

.

3

0

8

4

.

3

1

2

7

.

3

2

1

0

.

2

7

8

1

.

1

2

8

7

4

0

8

3.000

5.000

7.000

Number of homicides (1987-2008)

Figure 7. Homicides in Medelln between 1987-2008 (Sistema de Informacin para la Seguridad y la Convivencia 2009, p.14, edited

by author)

Figure 8. Repressive act of Colombian military in informal selement (Suarez 2012)

11

polical agendas. Next to that the inhabitants of these neighbourhoods simply did not have the same civil

rights as the people from the formal city, they were not fully accepted as cizens of Medelln.

Narco tra c, paramilitaries, guerrillas and polics

These urban problems are not all standing on their own and are part of a bigger range of urban issues.

Problems in both spaal and socio-economic guises that appeared together with the boom of informal

selements are for instance: scarce educaon amenies, criminality and narcotra c; and high violence

and homicide rates. If we look into the laer ones, we see that these are to a big extent correlated to

each other.

Medelln became notoriously known during the eighes because of the drug cartel leaded by

Pablo Escobar, called the Medelln Cartel. This was not only measurable in criminality rates and the

amount of cocaine that was produced by them, but also in violence and homicide rates. During the end

of the eighes, murder rates grew explosively, with a summit in 1991 of 6,349 homicides in one year

(see also gure 7) (Marn and Corrales 2011, p. 38). It was in this period that Medelln became not only

the most violent and dangerous city of Colombia, but also one of the most violent cies in Lan America

and even the enre world. With a homicide rate per 100,000 inhabitants of up to 444, according to what

Medellns former mayor Alonso Salazar stated in an interview, the city earned this dubious tle (Carbona

2011, p. 7).

It was mainly because of the absence of instuonal power, such as police and judiciary, that

in the poor (informal) selements and outskirts of the city the violence ourished (Marn and Corrales

2011, p. 40). But not only the lack of repressive power from the state was a problem, also the fact

that amenies like educaon, health care and recreaon missed in these areas. As a result there were

the organized criminal groups (such as guerrillas and narcotra c cartels) that took over the power in

these areas. This did not happen only because violent suppression of the inhabitants in these informal

neighbourhoods, it was also because the gang leaders jumped into the vacuum of care taking for these

areas. This is shown as well by for instance whole communies that were housed with the money of the

Medelln Cartel, with even a whole neighbourhood being named aer Pablo Escobar (Pescados de mi

padre 2009). Although the government tried to control the situaon by suppressing these acvies, see

gure 8, it grew totally out of their hands.

Not only narcotra c cartels had taken over the power in the informal selements. They had to

share their prevalence with other pares such as le wing guerrilla and right wing paramilitary groups.

These groups had moved up from the salve (the hardly accessible jungle) to the periphery of the city (La

Sierra 2005). So the people that escaped from the civil war in rural areas, as was menoned before, found

themselves again in a war since the armed groups followed the same path to the city. This power struggle

was and is not only a maer of machismo, but as well a way to provide a certain sense of security for the

inhabitants of these neighbourhoods (Gurrez Sann and Jaramillo 2004, p. 17).

A constant dynamic of new created alliances and enemies made the situaon in these peripheral

parts of Medelln one of constant unpredictability, fear and insecurity. Most of the major extreme le

wing guerrilla groups were formed in the 60s of the last century, of which the FARC, the ELN and M-19 are

most known. That the power of these groups is not solely based on military power can be seen in the fact

that a lot of these groups also founded a polical equivalent, like the Patrioc Union Party (FARC) and the

M-19 Democrac Alliance (M-19) (Insight on Conict 2012). Although many of these side organizaons

feigned to achieve a secure and peaceful situaon and had some posive side eects, for the greatest part

they only enlarged the hegemony of the terrorist groups. The power that these groups have within the

periphery of the city is polically so big that they are oen referred to as a state inside the state (Gurrez

Sann and Jaramillo 2004, p. 21).

This situaon wherein wars between dierent militant groups take over the daily life in these

neighbourhoods is very well recorded in the 2005 documentary La Sierra, about the slum that goes by

the same name. It shows the incompetence of the state and the police to control the situaon in these

areas, as well as the almost hopeless situaon that the gang members and other inhabitants of the

neighbourhood nd themselves in (La Sierra 2005). But eventually it shows as well sparkles of hope

as the paramilitary group in which they end up, Bloque Cacique Nubara, gives up its weapons and as

12

Illegal Armed Actors

Local government gradient of control

Informal seulements

Figure 9. Locaon of informal selement, local government control and illegal armed actors (Samper 2010, edited by author)

Figure 10. Spaal fragmentaon process in the centre of Medelln in the period 1950-2000 (Hernandez Palacio 2012, p.110)

13

members get amnesty from the government and return to legality (Gurrez Sann and Jaramillo 2004, p.

27). That these dierent groups are sll present in the dierent areas of the city and the bales between

these pares are sll ongoing is very apparent (La Sierra 2005; Sann and Jaramillo 2004). This is mainly

a result of the policizaon of crime and violence that is sll very much extant. For is big part because

old role models do not disappear overnight, but as well for the fact that this process is sll (to a lesser

extent) going on. Aer the mainly repressive acons that were taken by the state in mainly the 80s, now

they seem to believe in more result from peace accords, as is shown as well by very recent negoaons

between the government and the FARC (Reyes 2013; Sann and Jaramillo 2004).

The rst negoaons with the dierent milias in the city started in the beginning of the 90s

under leadership of president Csar Gaviria (Marn and Corrales 2011, p. 46). These negoaons did not

sort that much result on the longer term. It is even said that in way the state provided for these groups

a way to connue their acvies, while appearing to be socially acve. This is maybe best stressed by a

quote from a milia member that their acvies existed of military undertakings in the night []and

social work in the day me (Sann and Jaramillo 2004, p. 22). These negoaons did not work out on the

long term, in that sense that aerwards the homicide and criminality rates in Medelln stayed high. On

the other hand the senment that was present within the communies of the informal selements is very

well stressed in the agreement that was achieved in 1994. This agreement stated that the state should

invest in improving the community infrastructure, basic health care, educaon and recreaon amenies;

as well as it should take care of the level of security in these neighbourhoods (Sann and Jaramillo 2004, p.

23).

One could say that the government agreed here on the fact that they have to take proper

responsibility for the quality of life of their cizens living in these informal areas of the city. The local

government of Medelln did not take this responsibility in full account right aer the 1994 agreement. But

with the introducon of a new naonal law, mandang the municipal administraons to be responsible for

assessing their own urban issues with a local development plan, cies like Bogot and Medelln showed

during the last decade how signicant planning is in the renewal of a society (Calderon Arcila 2008, p. 58).

And with the introducon of the Proyectos Urbanos Integrales (PUI) (Urban integral projects), iniated by

the municipality of Medelln in 2002 a real change became visible (EDU 2008). It was from that moment

on that the (local) government really started to take responsibility for these areas of the city, which should

be a part of their polical task. The urban development plan as such revitalized both planning, governance

and local democracy, by using these concepts in order to structurally ght social injusce (Calderon Arcila

2008, p. 58). As a result the city was able to change into a connental (or even world wide) example of

urban improvement and good governance.

Spaally fragmented city and globalizaon

The social fragmentaon within the city of Medelln, both between informal and formal city and within

the informal selements it selves, has a spaal correlave as well. The big dierence between rich and

poor, as it exists in a lot of developing countries, results in a cityscape that reects this socio economic

reality of extremes. This process of urban segregaon constuted the fragmented city that Medelln is.

The fragmented city as a concept is frequently described since it was rst menoned in the beginning

of the 90s. In an arcle on cies in developing countries Italian urban planning professor Marcello Balbo

introduced the term fragmented city (Balbo 1993). A fragmented city is characterized by its heterogeneous

structure, which is hard grasp with tradional planning techniques that were developed for more

homogeneous European and North American cies.

Medelln is a very parcular example of this model of a city as a heterogeneous and fragmented

assembly. Due to the organic and uncontrolled growth of the city, mainly during the tweneth century,

as is described before a cityscape emerged that is very unclear and appears very messy. This is for a big

part the result of the informal growth of the peripheral areas of the city, see gure 9. The contradicon in

these cies lays in the fact that there are islands of wealth, with private golf courts and police patrolling,

interspersed with slums that barely have access to fresh water and other basic infrastructures (Balbo 1993,

p. 25). The city of Medelln exists of dierent kinds of (sub) cultures, urban forms and architectural styles

that do not meet each other in the sense that they all seem to speak another language (Vasquez Zora

and Villalba Stor 2008). This physical fragmentaon is partly generated by new highways and avenues

14

15

that were constructed within the tradional city grid, see also gure 10 (Hernandez Palacio 2012, p. 109).

This resulted in an oversupply of services for the high class, in sense of infrastructure, but an undersupply

of services within the slums of the city. To put it even more extreme; with the creaon of this hyper

connecvity the rich elite, in the form of these highways, the inhabitants of the informal selements

became even more cut o from the rest of the city. For them these infrastructural axis works as a barrier,

that decreases their access to services and amenies outside their own neighbourhood.

It is this incommensurable aspect of the city that shows very well with what kind of complexies

inhabitants, planners and policians have to deal. A lot of mes the fragmented city is related to as an

eect of globalizaon, since the government oen invests more in the accumulaon of global capital than

they do in development for their local cizens (Bolay 2006, p. 285). In the case of Medelln some notes

can be made with regards to this theory. With having one of the biggest texle industries of Lan America,

during the 1980s the producon largely decreased and shied to South East Asia (Mendieta 2011, p. 177).

Even with the cocaine cartels taking over the local economy of the city during the same era, Medelln was

sll very much known as well for the texle producon with major brands like Coltejer and Fabricato.

In that sense the aracon of global capital for Medelln could be a way to reinvent itself as a

big texle producer in the world. And by organizing a big texle fair every year, Colombiatex, the city of

Medelln works on endogenous development in the words of John Friedman (Friedman 2007, p. 990).

The gain is that both local entrepreneurs prot, jobs are created and there are investments in both local

economy and culture (El Colombiano 2013).

The investment in local endogenous culture and economy seems the way to bridge the gap that is

created between the dierent strata in the city. This counts for the social economic development within

the city, as well as for the spaal planning of the city. The creaon of a common civic culture seems to be

the answer to the queson that has been raised in the last few decades by violence and social unrest.

16

Figure 12. Antanas Mockus as Supercizen (The Telegraph 2010)

Figure 11. Medelln divided in the dierent sectors with upgrading projects indicated (Marn and Corrales 2011, p. 30/31).

17

The transformaon

Reinvenon of Colombian civic pride

The intended changes that were already present in the 1990s became really tangible with the

implementaon of the rst Proyectos Urbanos Integrales (PUI), also see gure 11. This upgrading plan

was not the rst of its kind in Lan America and can therefore be compared to its predecessors. There are

several other big cies on the same connent that improved labour mobility by means of implemenng

public transport into the informal selements of the city (Curiba, Carcas, Bogot). This has been done

with dierent kind of transport modes, systemac approaches and on various scale levels. In both Curiba

and Bogot this has been done by the introducon of the Rapid Bus Transit system (Ardila 2004). Curiba

was the rst to implement a system as such, already back in the 1970s. That the mode of transport itself

is not necessarily the point can be seen in the case of Medelln itself and in Carcas where a Metrocable

system was implemented. In order to take a look not so much in the mode of transport that was

implemented itself, but more into the plan that it is embedded in, a comparison to the case of Bogot is

the most fruiul. The comparison to Bogot will be made, since this is not only geographically, but also

with regards to the undergone development process, a city that is close to Medelln.

The example of capital Bogot

Compared to Medelln the city of Bogot had to come from less profound, it did not suer as much from

guerrilla and paramilitary wars and narcotra c. But was sll considered to be one of the most violent

cies in the world, during the beginning of the 1990s (Feireiss 2011, p. 85). The stabilizaon of the

situaon in the capital of Colombia took place already round the change of the centuries. The start of

the era of recuperaon is considered to be with the inauguraon of mayor Antanas Mockus (1995-1997),

also see gure 12, and aer that connued by mayor Enrique Pealosa (1998-2000) (Pizano 2003, p. 13).

Antanas Mockus connued his recuperaon work in another term from 2001 to 2003. On the Architecture

Biennial in Venice of 2006 the city of Bogot was even acknowledged with a Golden Lion for being the

best-pracce case of egalitarian urban transformaon (Calderon Arcila 2008, p. 10).

The main reason for this major turn seems to be the stabilizing governance situaon since the

mid ninees. Several numbers support this postulated improvement of both the socio-economic status of

the city and the spaal organizaon level. A good example for this more stabilized governance situaon,

is the increase from 25 months in 1992 to four years for every mayor to stay in charge (Gilbert 2006).

This without a doubt leads to more connuity of administraon and thus polical stability. A more stable

polical situaon is a really ferle ground for development of integral urban improvement projects. The

Transmilenio project (gure 13), based on the Bus Rapid Transit system in Curituba, is a good example

of this. The project led to a higher labour mobility and by this increased chances for people, from

neighbourhoods that were formerly disconnected from the rest of the city, on the labour market.

Along with big projects like the Transmilenio there were projects on the lower urban level. These

projects that were developed closely with local communies were mostly dealing with recuperaon of

the public space. They existed out of thousands of partnership between the (local) government and civil

community iniaves (Pizano 2003, p. 54). These projects are part of an overarching plan called Red de

Espacios Publicos (Network of Public Spaces) which was launched by the local government together with

the Plan Maestro de Ciclovias (Master Plan Bike Paths) and Red de Bibliotecas (Network of Libraries)

(Calderon Arcila 2008, p. 10).

While the rst term of Antanas Mockus was mostly characterized by the improvement of the civic

culture that he made, besides his somemes eccentric behaviour (gure 12), Pealosa was the one who

pleaded most for infrastructural enforcements (Feireiss 2011, p. 86). Under leadership of Mockus major

changes were achieved, as stated very clear by Lukas Feireiss:

water usage dropped 40 per cent, 7,000 community security groups were formed and the homicide rate fell 70

per cent, tra c fatalies dropped by over 50 per cent, drinking water was provided to all homes (up from 79 per

cent in 1993), and sewerage was provided to 95 per cent of homes (up from 71 per cent). When he asked residents

to pay a voluntary extra 10 per cent in taxes, 63,000 people did so (2011, p. 86).

18

Figure 13. Transmilenio BRT system along Avenida de las Americas (Tongeren 2011)

Figure 14. El Tunal Library (Villamil 2011)

19

Next to that also behavioural changes can be menoned in the daily life of the bogotanos. This diers

from a general clampdown on drunkenness to homicide rates dropping from 80 per 100,000 inhabitants

in 1993 to 23 in 2006 (Gilbert 2006, p. 397). In that sense Mockus and Pealosa were complementary

to each other, as is also stretched by Colombian arst Adriana Torres Topaga in an interview: The rst

changed the citys a tude, and the second connued with these ideas, bringing to fruion necessary

infrastructural changes. (Feireiss 2011, p. 88).

From the introducon of the Transmilenio system on the commuter me dropped with 20 per

cent in 2001, with only a quarter of the total system being completed yet (Echeverry et al. 2004, p. 23).

In 2005 the network already existed out of 362 buses driving on 421 kilometres of especially for these

vehicles constructed bus lanes covering 78 mainly poor neighbourhoods in Bogot (El Tiempo 2005).

Pealosa, who is for the biggest part responsible for the introducon of the Transmilenio, was also the

one who opted for the construcon of new public libraries all over the city (Red de Bibliotecas), see also

gure 14, and parcularly in the poor (informal) neighbourhoods. These libraries that were designed by

Colombias most famous architects now welcome about eleven million visitors per year (Gmez 2004).

Civic pride of the bogotanos

That these big investments in the cultural, but as well the economic, life of the bogotanos improved the

quality of living is not to be doubted about. Various opinion polls show very well that the amount of

the cizens that see the situaon in Bogot improving doubled between 1999 and 2005 (Gilbert 2006,

p. 397). This shows that not only in (economic) stascs the quality of life has increased, but also in the

inhabitants daily life opinion on the city that they live in.

This improvement of the quality of life in Bogot also resulted in that the inhabitants of the city

discovered a sense of pride in their city, as Brish geographer Alan Gilbert put it (2006, p. 398). This civic

pride is maybe one of the most important achievements of all the upgrading projects that were executed

in Bogot. The creaon of this common identy is also very important regarding the fact that unl 1990

inhabitants did not idenfy themselves with Bogot, but with the region they originally came from, even

though they already lived in the city for generaons (Mosca 1987). This changed into four-hs of the city

populaon seeing themselves as bogotano, a full cizen of Bogot (2006, p. 398). This is a major victory,

which can not be overesmated, for both the city as for the inhabitants.

That Bogot can be seen as a (global) example of slum upgrading, and of upgrading a city in

general, goes without a doubt. This can be shown by the fact that many delegaons from all over the

world came to visit the city and see how they changed things (Ardila 2004). One of the major challenges

in that sense is the connuaon of this process of progress. The city has sll a lot to improve, like the big

inequality that is sll present in the city. The inequality is very much visible with 40 per cent of the income

of the metropolitan area, in hands of the upper 7 per cent of the almost 11 million inhabitants (Klink 2008,

p. 2).

Recent developments sll show improvement in for instance a decreasing murder rate, 24 per

cent cut in 2012, but there is also cricism on for instance the failed aempt to make rubbish collecon

a state issue (The Economist 2013). This last point of cricism is due to policy of current mayor Gustavo

Petro, a former guerrilla, who is following a more extreme le wing direcon. There where his recent

predecessors were more in favour of privasaon, which seemed to be a successful way (Gilbert 2006,

p. 402). This shows as well the main possible problems for the future, namely that polical disconnuity,

with a total dierent approach the achievements can be made (partly) undone. Nevertheless the

investments that are done in public transport, libraries and the public space of the city are there to stay.

They made the bogotano proud of its own city and brought the city a lot of welfare and prosperity. The

technocrac approach, of mainly the mayors Mockus and Pealosa, was essenal in the relavely quick

process of implemenng the Transmilenio and other public services (Gilbert 2006, p. 415). These mayors

with their brave and refreshing polical style made a change in the physical cityscape of Bogot, as well as

in the socio economic status of this metropolis. As Marcela Aguilar, a local denst, points out very clearly

in an interview:

The two mayors undoubtedly changed the quality of life of Bogotas inhabitants and visitors. Before their terms

as mayor, it was not possible to walk along the sidewalks in many streets; one had to walk in the street. Chaos

and insecurity reigned in the city (Feireiss 2011, p. 88).

20

Figure 15. Locaon of PUI projects, local government control and illegal armed actors (Samper 2010, edited by author)

Figure 16. Parque Explora building (Gil 2011)

Local government gradient of control

Informal seulements

Integrated Urban Projects

21

Seen from that side it is very much palpable that Bogot worked as a kind of model city for Medelln. The

results that were obtained created a trend in the country, Medelln was one of the cies where just like in

Bogot public services, facilies and public spaces are developed (Calderon Arcila 2008, p. 58). This was

not so much a literal translaon of the used plans, but more an intuive example of how public life in city

that dealt with this kind of issues can be improved.

The renaissance of Medelln

Aer decennias of violence, growing social problems and urban degeneraon as menoned before the

city of Medelln has almost turned one hundred and eighty degrees during the last years. Following the

example of Bogot, also in Medelln plans were made to come up with an integral approach to ght both

the socio economic and spaal urban problems of the city. The example of Bogot could not be followed

as a mere blueprint, since there are curtain dierences like in the specic topography of the city, the

relaon with the salve (jungle outskirts), see also gure 15, and populaon conguraon and a lot of

other urban specics.

The year 2003 can be seen as the start of this process, with Sergio Fajardo in o ce as mayor of

the city. Fajardo appointed a technocrac cabinet that prepared the integral transformaon model of

the city for the term 2004-2007 (Marn and Corrales 2011, p. 48). The main point of this plan is, as was

stated a publicaon of the municipality, to create an equal city were all cizens have the opportunity of

developing relaons supported by all the (cultural) services that are supplied, in the public space (Lpez

2006, p.10). The successor of Fajardo was Alonso Salazar, he connued the transformaon plans aer

2008. Salazar was already a prominent polician and was part of Fajardos government as well, in that way

he was very much complementary to his predecessor. Just like Mockus and Pealosa made the dierence

in Bogot, Fajardo and Salazar were the ones who brought Medelln change and polical connuity.

There were several plans iniated by the local government to improve the underdeveloped

parts of the city. Just like in Bogot the improvement plans focus upon the dierent aspects of urban

transformaon. These plans meant to increase mobility, improve educaon and recover public space and

green areas. They go under following specic plans as they are executed: Integral Urban Project (PUI),

the Land Use Plan (POT) and the Master Plan for Green zones (Drissen 2012). Known experts out of these

plans are the Metrocable project, Parque Bibliotheca Espaa and the outdoor escalators in Comuna

13 (BBC 2011). The Empresa de Desarrollo Urbano del Municipio de Medellin (Urban Development

Coorporaon of the Municipality of Medellin) is in charge of the implementaon of these plans (EDU

2008).

These development projects are received in a very posive way. This not only follows from

literature within the eld of governance, planning and architecture, but also turns out to be in interviews

with inhabitants from all dierent strata and areas of the city.

This if for example explained by interviews with local inhabitants in the book Tesfy! The

Consequences of Architecture on the Parque Explora (gure 16) project. The people from the community

changed their mind about policians, since they saw really posive change in their neighbourhood

(Feireiss 2011, p. 62). This seems to be a mutual exchange of growing respect, since in the same interview

appears that the mayors o ce improved the relaonship with the community. And a really important

gesture was made by creang close partnership with the local community, also showed by the fact that

residents were employed in the construcon zone (Feireiss 2011, p. 62).

The construcon of new public projects in neighbourhoods that were formerly seen as degraded;

gives them a new image and supplies in public funcons, like cultural and educaonal amenies. In

an arcle for El Colombiano Jaime Sarmiento states that the new architecture helped to change the

behaviour and mentality of the people in these poor neighbourhoods (Sarmiento 2011). This idea of

architecture changing the image of an area, also referred to as the Bilbao eect, should be nuanced with

the idea that most of these changes are preceded by years of civic renewal (Kimmelman 2012a). As is

shown in the example of Bogot the built Transmilenio and library projects, among the others, were not

the boosters of the success on themselves. They were supported by societal and polical changes, and are

maybe more physical reecons of these changes in civic life. The built projects in that sense can be seen

as material representaons of the civic pride and not merely as the cause of these proud feelings of the

inhabitants. This makes these projects really valuable in both material and social psychological sense. It

22

Figure 18. Locaon of metro lines in orange, with other projects of PUI located with circle (Navarro Serch 2010)

Figure 17. Metro network of Medelln with Metrocable lines J, K and L (Medelln Digital 2011)

23

should on the other hand not be confused with the idea of these buildings being the reason that this civic

pride is present in the city. The buildings, the architecture, should be seen in a larger social and economic

ecology (Kimmelman 2012b).

In the upcoming part this process will be described, from the iniaons of the plans, to the

construcon ll the newly created urban situaon. In order to give a nuanced idea of this, and to

cover both the lower scale implicaons and the integral urban plan, dierent parcular projects will be

described. These projects vary from transit projects (i.e. Metrocable) to public buildings (i.e. Bibliothecas

Espaa) and public space developments (i.e. Parque de la Paz 20 de Julio). This will be done in order to

describe the eect from the dierent intervenons on the dierent scales.

Metrocable

This aerial cable-car project was one of the rst intervenons to be executed, starng in 2004 (Dvila et

al. 2011). This together with the fact that this project has a very iconic eect on the upgraded area made

it one of the agships of the integral development process. The introducon of this transport mode was

a way to deal with urban challenges such as growing amounts of commuters, increasing transport speed

demands and a queson for environmental friendly soluons (Brand 2012, p.17). The choice for an aerial

cable-car was as such merely the soluon to solve the big height dierences that had to be bridged.

The informal selements that should be taken out of their posion of isolaon, are located mostly on

the steep hills surrounding the city. As a parcular soluon to solve transport problems for informal

selements in comparable topographical se ng; the example is followed by other cies. Other cies that

introduced a comparable system are Carcas (Venezuela), Rio de Janeiro (Brazil) and Kohima (India).

The advantages of such a system is that it needs relavely less space on surface level, only the

staons and the columns are placed on the ground. This oers a lot of opportunies, since there is hardly

any spare ground in these informal selements available. Next to that, demolion of exisng structures is

not desirable, since the underlying social structures will be destroyed as well, which leads to a lot of social

unrest. This Metrocable system instead builds upon these social structures that are already present and

reinforces them with the potenal of mobility, which becomes a more and more powerful concept within

contemporary society (Brand 2012, p.18). As already menoned before it increases labour mobility, but

not only that, it gives the inhabitants of these informal selements the right to the city. The introducon

of a public transport system as such is a way to ght inequality, which was very much present in the city

of Medelln. It literally connected the informal selements with the rest of the city and by this these areas

where taken out of their (socio economic) isolaon.

The exisng metro network of Medelln, exisng of two train lines, was supplemented in 2004

with the compleon of Lnea K (Line K), see also gure 17. This line connects the areas in the northeast

(Comunas 1 and 2) of the city to the exisng public transport network (Brand et al. 2012, p. 39). Later on,

in 2010, this line was extended by a (mainly) tourist line (Lnea L) up to Arv, in the rural outskirts of the

city. The informal areas in the west side of the city (Comunas 7 and 13) where connected to the rest of

the network in 2008, when Lnea J was completed, see gure 18 (Dvila et al. 2011). With the compleon

of these lines some of the objecves as they were formulated in the beginning of Fajardos term in

2004 were achieved. By including these areas in the exisng transport network, they did not become

only spaally integrated with the rest of the city. These comunas (neighbourhoods) also became part of

the service network that is already present in the city, it became a potenal part of the daily life of the

inhabitants. By this the objecve of making educaonal, sport, recreaonal and health services accessible

together with increasing the mobility for all inhabitants of the city was achieved (Lpez 2006, p. 11).

On one hand the Metrocable is a system that has impact on the dierent comunas, because

of the city integraon eect, but on the other hand it has also an eect on the local level. Thus on the

level of the neighbourhood itself this public transport hubs have an impact on for instance the local

economy and the social structure. That the retenon and reinforcement of these structures on the lower

level are obviated as well is showed by the iniaon of the Centros de Desarrollo Empresarial Zonal

(Cedezo) (Local Entrepreneurship Development Centres). The centres are strategically located at the end

of the Metrocable lines, which seems to be well chosen, since for instance in Comuna 1 from all of the

local producon units 72 per cent are placed along Lnea K (Coup et al. 2012, p.81). Next to that, the

24

Figure 20. Fernando Botero Library Park designed by G Ateliers (Garca 2012)

Figure 19. Public escalators in Comuna 13 (La Tercera 2011)

25

contractors who are commissioned by the local government for one of the many satellite projects need

to hire a signicant amount of local labourers (Dvila et al. 2011, p. 9). These dierent projects that are

developed alongside the Metrocable project ensure its success, by simply implemenng the cable-car

system on its own it would not embedded enough in the exisng structure. The complexies of the

exisng informal neighbourhoods ask for a way more subtle soluon. These local entrepreneurship and

employment projects make sure that both on the long and the short term there is a good basis for socio

economic success.

With regards to the exisng social structure in informal selements it is also really important to

take care of the embedding of a new transport system. Within these neighbourhoods there is very strong

sense of a community bond. They are used to take the same pathways on a daily basis, since they are

considered to be safe. This kind of really precarious social structure should be taken into account when

a staon of the Metrocable is placed in a certain neighbourhood. This is why working closely together

with people from the community is a very important issue during the preparaon and design process

of such a transport system. That the authories somemes sll use to much of an top-down approach,

even though with good intenons, was what Colombian American urban sociologist John Betancur found

during his research in Medelln (Betancur 2007, p. 10-11). In reacon to this the government seems to

take this crique serious. It is even explicitly stated that parcipatory planning is a main objecve of the

development plans, together with construcng secondary infrastructure like pavements and public space

equipment (Municipio de Medelln 2007, p. 14). By this it can be seen that a lot of lessons where as well

learned along the way and made the whole process bit by bit more integral.

The mobility of the inhabitants of the dierent comunas is not only enhanced by the Metrocable

network. As stated before also the more local mobility of the inhabitants is developed. A good example of

this is the earlier menoned elevators in the barrio Las of Comuna 13, see gure 19. These elevators are

complementary to the Metrocable system and cover a total height of about 300 meters, decreasing the

travel me from 30 to 5 minutes (Morales Velsquez 2011 and BBC 2011).

These elevators make the rest of the city accessible for those who where not able to climb all the

exhausve stairs anymore and they run during same me of the day as the Metrocable (Gualdrn 2011).

This highly integrated development on a (local) infrastructural level in combinaon with socio economic

support of entrepreneurship and cultural amenies make these PUI as successful as they are.

Public libraries and other amenies

The combinaon and integraon of both the physical infrastructural networks, like the ones are described

in the previous part; and the cultural and educaonal network is one of the main characteriscs of the

PUI. The upcoming part is dealing with these educaonal and cultural amenies that are an integral part

of the development plan. One of the most known is the Bibliotheca Espaa, which is actually just one

of the 23 libraries that are part of the Medelln Library Network (Red de Bibliotecas del Medelln) who

oer together public knowledge to all the city cizens. In the arcle that New York Times architecture

cric Michael Kimmelman devoted to the upgrading projects in Medelln he interviewed several local

inhabitants on the parcular projects. Among them was Mateo Gmez, who stated that: The Espaa

library changed our concepon of ourselves [...] before, we felt a sgma (Kimmelman 2012b). The

Espaa library is located at the intersecon of Lnea K and L. Because of the many tourists that use the

Lnea L, as explained before, the library is good addion to the tourist route they take. This is maybe at

the same me one of the weaknesses of the project as such. Some of the criques on the project are on

the fact that the objecve of this building sll seems to be on creang eye-catching buildings to grace the

covers of glossy magazines (Kimmelman 2012b). This also counts up to a certain extent for a project like

the Fernando Botero Library Park on the western outskirts of the city, close to the Lnea J terminal staon

of the Metrocable, see gure 20.

This criques of course do not erase the big amount of opportunies that were created for

the inhabitants of the informal districts of the city. Because it did not only changed their concepon of

themselves and about how the government and the rest of the city thinks about them and sees them.

But it creates new possibilies that could not be thought of before. So explains as well Harold Giraldo, a

regular user of one of the educaonal building projects, in an interview: Parque Explora is a gateway to

26

Figure 21. Public life in the late aernoon at Parque de los Deseos designed by Felipe Uribe in Comuna 4 (Marn and Corrales

2011, p. 143)

27

knowledge, a place where one can nd out how things work (Feireiss 2011, p. 63). This clearly supports

the idea that this projects opened up a world of changes for the dwellers of informally built housing units.

They are no longer an unsupported part of the city, but they are supplied with the services and amenies

that are available to the rest of the cizens of the city as well.

And not only do these places like Parque Explora, among others as the renovated Botanic

Garden and the Parque de los Deseos, supply services and amenies to the inhabitants of the poor

neighbourhoods. They also aract people from other strata of the society and work in that way as a

social integrator for the city (Marn and Corrales 2011, p. 128). Because not only did they invest in

the development of public space and buildings within the informal selements themselves. They also

developed the public space in other places in the city and on the boundaries between the formal and the

informal. These projects include places varying from sport elds, to cultural centres up to bicycle paths

(Marn and Corrales 2011, p. 132). These places also added to the sense of cizenship for the informal

city dwellers. From now on they are literally able to parcipate with all the other cizens of the city, they

became an inherit part of the city.

On the more pragmac level there are sll aspects that could be improved, as they are menoned

by both inhabitants and other actors in the projects. The libraries for instance can be seen as a good

start of the development of a public realm within the comunas. But as is explained by earlier quoted

Mateo Gmez: were sll missing cultural spaces, the library closes too early, the situaon is sll very

uncertain (Kimmelman 2012b). There is a certain risk that projects become to much of a sham, and are

only becoming a aesthec make over. The challenge of course is to connue this development for a more

equal city, like it is in Bogot too. Here it is best to quote the words of Michael Kimmelman, who sees a big

role for the new generaon, that is not to much concerned about architecture magazine covers, but more

about a city of greater equality:

The city has made big strides, aer all, using cu ng-edge architecture as a catalyst. But here young architects press

for yet more creave soluons. They take for granted as their jobs both formal innovaon and also the humanitarian

role of architectural acvism (2012b).

It is this a tude that has to be inherit by both the community itself as well as by the policians

and planners. A good looking building is something that one can be proud of and should take care of, on

the other hand it should not become a goal on its own. The social context in which the building has to be

embedded should be strengthened by its presence. As is shown with the public buildings that were built

within the upgrading process, a building is able to create new possibilies, to bring people together. It is

this force of a building that should be taken to its maximum strength.

Cultura ciudadana

One of the most important achievements of the upgrading projects is the fact that the informal

neighbourhoods of the city that were: once shunned by cizens and forgoen by the public

administraon, are now a symbol of the urban renaissance in Medellin (Duarte 2011, p. 10). The projects,

as is menoned before, created a sense of cizenship for the inhabitants of the comunas. For decades

they were seen as the parasites of the city. The government did not see the informal selements in which

they lived as part of their responsibility. With the realizaon of the upgrading projects it did not only

appear to the dwellers of these self built neighbourhoods that they were tolerated, but they became

an o cial part of the city. It was the physical representaon of their way out of informality, of not being

registered and not exisng for the local authories.

It is this being part of what one could call the cultura ciudadana (cizen culture), that is the legacy

of this integral upgrading process (see also gure 21). Or to put it in the words of one of the revoluonary

mayors Alonso Salazar: It was a process in which society rea rmed itself in pride of identy, in the work

ethic; a self-made society because it had always been far away from everything (Carbona 2011, p. 37).

The integral upgrading project had as one of its main objecves the social inclusion of a signicant part

of Medellns habitants. And although it was long way, from the rst iniaves in 1993, ll its success

nowadays, it paid of well. The process proved that there are fruiul counter proposals possible as an

alternave to the neo-liberal fragmented city of social exclusion. It created a city with inhabitants that are

proud of living in Medelln and being part of a society with a ourishing civic culture.

28

29

Conclusions

What can we learn from the process that took place in Medelln? First of all that the project does not

stand on its own. The integral upgrading project of the informal selements in Medelln is one that was a

result of years and years of polical and societal struggle. The city had to come from the absolute boom,

with having one of the highest homicide rates in the world. And it was with acknowledgement to a new

polical generaon that the process of social inclusion could take of. This change was necessary in order to

overcome the enormous problems that the city was dealing with, as we can conclude from the following

as well:

Fighng against social exclusion presupposes changes in the exisng governance structures, such as rethinking

mechanisms for delivery of services and providing instuonal space to allow residents to act as subjects in

decision making and change in their neighborhoods (Cars et al. 2002, p. 6).

The extreme situaon that the city found itself in asked for new experimental and bold decisions.

Fortunately there were examples that could be learned from. As well from within Colombia itself, like the

process iniated in Bogot in the 1990s, as from foreign cies like Curiba in Brazil. These cies showed

that with innovave public transport systems (Bus Rapid Transit) the socio-economic situaon of a big part

of the society could be increased. This by liing up their labour mobility and as a result giving them the

right to city, access to services and amenies.

Not only the labour mobility and access to other parts of the city were improved, but by the

construcon of public buildings like libraries and educaon centres the informal areas themselves were

developed as well. This not only created a new face for these neighbourhoods that were before seen

as hideous and a burden by the rest of the urban society. It created a sense of civic pride within these

communies, the feeling that they are an o cial part of the city. This was done with the construcon of

both public facilies as well as open public spaces, that are scarce and mostly even lacking in informally

built neighbourhoods. These intervenons in the built environment were combined with policies like

legalizaon of land tenure (Betancur 2007, p. 10). This not only created an inux with regards to the socio-

economic status of the inhabitants, but also ensured them that they had the right to stay were they live.

The laer is very important, because this was also a reason for house owners to invest in their home and

by that creang a more liveable environment with a higher quality of life.

The iniated process resulted in new emerging social capital that not only added to the value

of the daily environment of the inhabitants of the comunas, but to the city as a whole. It did that by

reinforcing the social bonds that are present and creang new possibilies that together lead to a

urban society of parcipaon, instead one of exclusion and fragmentaon. It was the integral approach

of the upgrading project that marks a big part of the success. What started at the city scale with the

implementaon of the Metrocable system and the construcon of big public works was completed with

the embedding of these systems within the small and local scale. And all this with a parcipatory approach

wherein inhabitants did not only have a voice, but were included up to the construcon process. All

the dierent projects were developed in close partnership with the local community. By this both the

dierent scales where covered, from big tot small, as well as the whole process range, from iniaon to

construcon.

The architecture that has been built works both as a physical representaon of the civic pride of

the inhabitants and as a catalyst of social cohesion. It is up to the new generaons to connue this process

and even leapfrog the older generaon that was somemes maybe more concerned with aesthecs

than with social issues. The process that took place shows that it pays of for policy makers, planners and

architects to stride for a more humanitarian and equal city by carrying out the role of social acvist.

30

Bibliography

Ardila, A. (2004) Transit planning in Curiba and Bogot: roles in interacon, risk and change. [doctoral dissertaon]

Cambridge, Mass.: Massachuses Instute of Technology.

Balbo, M. (1993) Urban Planning and the Fragmented City of Developing Countries, in: Third World Planning Review

15 1, pp. 23-35.

Baross, P. and Mesa, N. (1986) From Land Markets to Housing Markets, in: Habitat Internaonal 10 3, pp. 153-170.

BBC (2011) Giant escalator installed in Colombian city of Medelln, in: BBC World News. Online. Available on: hp://

www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-16336442. Accessed on November 29 2012.

Betancur, J. J. (2007) Approaches to the Regularizaon of Informal Selement: The Case of PRIMED in Medellin,

Colombia, in: Global Urban Development Magazine 3 1, p. 1-14.

Bolay, J. (2006) Slums and Urban Development: Quesons on Society and Globalisaon, in: The European Journal of

Development Research 18 2, pp. 284-298.

Brand, P. (2012) El signicado social de la movilidad, in: Dvila, J. D. (ed.) (2012) Movilidad urbana y pobreza:

Aprendizajes de Medelln y Soacha. London/Medelln: UCL/Universidad Nacional de Colombia, p. 16-22.

Brand, P. and Dvila, J. D. (2012) Los Metrocables y el urbanismo social: dos estrategias complementarias, in:

Dvila, J. D. (ed.) (2012) Movilidad urbana y pobreza: Aprendizajes de Medelln y Soacha. London/Medelln:

UCL/Universidad Nacional de Colombia, p. 38-46.

Caldeira, T. (1996) Fored Enclaves: The New Urban Segregaon, in: Public Culture 8, pp. 303-328.

Calderon Arcila, C. A. (2008) Learning from Slum Upgrading and Parcipaon. Stockholm: KTH, Department of Urban

Planning and Environment.

Carbona, V. (2011) A new dawn for Medelln, in: Urban World UN-HABITAT, January, pp. 36-39.

Cars, G.; Healy, P.; Mandanipour, A. and De Magalhaes, C. (2002) Urban Governance, Instuonal Capacity and

Social Milieux. Hamshire: Ashgate Publishing.

CEDLA (2008) Basiscursus: Kennismaking met Lajns-Amerika. [lecture] Amsterdam: University of Amsterdam,

Centre for Lan American Research and Documentaon.

Coup, F. and Cardona, J. G. (2012) Impacto de los Metrocables en la economa locale, in: Dvila, J. D. (ed.) (2012)

Movilidad urbana y pobreza: Aprendizajes de Medelln y Soacha. London/Medelln: UCL/Universidad

Nacional de Colombia, p. 80-96.

Dvila, J. D. and Daste, D. (2011) Medellns aerial cable-cars: social inclusion and reduced emissions, in: Cies,

Decoupling and Urban Infrastructure. London: UNEP - IPSRM Cies Report.

Dias Tamborino, M. (2011) The Informal Real Estate Market, in: Anglil, M. and Hehl, R. (eds) (2011) Building Brazil!

The Proacve Urban Renewal of Informal Selements. Berlin: Ruby Press, p. 10-11.

Drissen, J. (2012) The Urban Transformaon Of Medellin, Colombia, in: Architecture In Development. Online.

Available on: hp://www.architectureindevelopment.org/news.php?id=49. Accessed November 26 2012.

Duarte, F. (2011) A brave new era for public transport in Lan America, in: Urban World UN-HABITAT, January, pp.

9-10.

Echeverry, J. C.; Ibez, A. M. and Hilln, L. C. (2004) Anlisis Econmico de Transmilenio, el Sistema de Transporte

Pblico de Bogot. Bogot: Universidad de los Andes.

EDU (2008) Historia, Misin y Visin, in: Empresa de Desarrollo Urbano. Online. Available on: hp://www.edu.gov.

co/index.php/edu/mision-y-vision.html. Accessed November 26 2012.

El Colombiano (2013) Colombiatex cerr con 152,5 millones de dlares en oportunidades de negocio, in: El

Colombiano. Online. Available on: hp://www.elcolombiano.com/BancoConocimiento/C/colombiatex_

cerro_con_1525_millones_de_dolares_en_oportunidades_de_negocio/colombiatex_cerro_con_1525_

millones_de_dolares_en_oportunidades_de_negocio.asp. Accessed January 28 2013.

El Tiempo (2005) Cierres en Troncales de Transmilenio por Obras, in: El Tiempo. Online. Available on: hp://www.

elempo.com/archivo/documento/MAM-1956630. Accessed January 29 2013.

Feireiss, L. (ed.) (2011) Tesfy! The Consequences of Architecture. Roerdam: NAi Publishers.

Fernndez-Maldonado, A. M. (2011) Changing Spaal Logics in Lan American Metropolises. [lecture] Del: TU Del

Faculty Architecture, Urbanism Department.

Friedman, J. (2007) The Wealth of Cies: Towards an Assets-based Development of Newly Urbanizing Regions, in:

31

Development and Change 38 6, pp. 987-998.

Garca, O. (2012) Fernando Botero Library Park [Photo] Online. Available on: hp://thelayer.me/wp-content/

uploads/2012/10/Fernando-Botero-Library-Park-by-G-Ateliers-architecture-4.jpg. Accessed February 27

2013.

Gil, H. (2011) Parque Explora [Photo] Online. Available on: hp://www.ickr.com/photos/harveth/5638526316/.

Accessed March 17 2013.

Gilbert, A. (2006) Good Urban Governance: Evidence from a Model City?, in: Bullen of Lan American Research 25

3, pp. 392-419.

Gmez, J. (2004) Transmilenio: la joya de Bogot. Bogot: Transmilenio S.A.

Gualdrn, Y. (2011) Escaleras elctricas, el regalo para la comuna 13 de Medelln, in : El Tiempo. Online. Available on:

hp://www.elempo.com/colombia/ARTICULO-WEB-NEW_NOTA_INTERIOR-10926580.html. Accessed

February 11 2013.

Gurrez Sann, F. and Jaramillo, A. M. (2004) Crime, (counter-)insurgery and the privazaon of security - the

case of Medelln, Colombia, Environment & Urbanizaon 16 2, pp. 16 - 30.

Hernandez Palacio, F. (2012) Sprawl and Fragmentaon. The Case of Medellin Region in Colombia, in: TeMA Journal

of Land Use, Mobility and Environment 5 1, pp. 101-120.

Insight on Conict (2012) Colombia: Conict Timeline, in: Insight on Conict. Online. Available on: hp://www.

insightonconict.org/conicts/colombia/conict-prole/conict-meline/. Accessed October 6 2012.

Kimmelman, M. (2012a) Why Is This Museum Shaped Like a Tub?, in: The New York Times. Online. Available on:

hp://www.nymes.com/2012/12/24/arts/design/amsterdams-new-stedelijk-museum.

html?pagewanted=2&_r=2&. Accessed January 3 2013.

Kimmelman, M. (2012b) A City Rises, Along With Its Hopes, in: The New York Times. Online. Available on:

hp://www.nymes.com/2012/05/20/arts/design/ghng-crime-with-architecture-in-medellin-colombia.

html?pagewanted=4&_r=1. Accessed February 18 2013.

Klink, J. (2008) Building Urban Assets in South America. London: LSE Cies/Urban Age

La Sierra (2005) [moon picture], New York, Films Transit/IFP.

La Tercera (2011) Medelln inaugura escaleras mecnicas, in La Tercera. Online. Available on: hp://diario.latercera.

com/2011/12/28/01/contenido/mundo/8-95461-9-medellin-inaugura-escaleras-mecanicas.shtml. Accessed

February 18 2013.

La Virgen de los Sicarios (1999) [moon picture], Paris, Les Films du Losange/Le Studio Canal+.

Lpez, A. G. (2006) Plan de Desarrollo de Medelln 2004-2007. Medelln compromiso de toda la ciudadana, in:

Revista Salud Pblica de Medelln 1 1, p. 9-14.

Marn, G. and Corrales, D. (2011) Medelln: Transformacin de una ciudad. Medell n: Alcald a de Medell n;

Washington DC: BID.

McKinsey Global Instute (2011) Building globally compeve cies: The key to Lan American growth. August 2011.

New York: McKinsey & Company.

Medelln Digital (2011) Medelln Digital, in: Google+. Online. Available on: hps://lh3.googleusercontent.com/-

HR7BnfVvlTI/TvNSXtatnUI/AAAAAAAAAEs/fdUO02kzsLc/w497-h373/mapametropl%25C3%25BAs.jpg.

Accessed March 17 2013.

Mendieta, E. (2011) Medelln and Bogot: The global cies of the other globalizaon, in: City: analysis of urban

trends, culture, theory, policy, acon 15 2, pp. 167-180.

Miller Llana, S. (2010) Medelln, once epicenter of Colombias drug war, ghts to keep the peace, in: The Chrisan

Science Monitor. Online. Available on: hp://www.csmonitor.com/World/Americas/2010/1025/Medellin-

once-epicenter-of-Colombia-s-drug-war-ghts-to-keep-the-peace. Accessed September 6 2012.

Morales Velsquez, E. (2011) La comuna 13 estren sus escaleras elctricas, in: El Colombiano. [video]. Online.

Available on: hp://www.elcolombiano.com/video.asp?video=Medellin_escaleras-electricas-comuna-13-

inauguracion-26-12-2011. Accessed February 11 2013.

Mosca, J. (1987) Bogot ayer, hoy y maana. Bogot: Villegas Editores.

Municipio de Medelln (2007) Programa Mejoramiento Integral de Barrio. Medelln: Municipio de Medelln.

Pao, F. (2011) An Intergrated Upgrading Iniave by Municipal Authories: A Case Study of Medelln, in: UN-

HABITAT, Building Urban Safety through Slum Upgrading, pp. 7-20.

Pecados de mi padre (2009) [moon picture], Buenos Aires, Red Creek Producons/Arko Vision

32

Pizano, L. (2003) Bogot y el cambio. Percepciones sobre la ciudad y la ciudadana. Bogot: Universidad Nacional de

Colombia/Universidad de los Andes.

Red de Bibliotecas del Medelln (2009) Parque Biblioteca Espaa - Santo Domingo, in: Red de Bibliotecas. Online.

Available on: hp://www.reddebibliotecas.org.co/sistemabibliotecas/Paginas/parque_biblioteca_espana.

aspx. Accessed February 11 2013.

Restrepo Cadavid, P. (2011) The impacts of slum policies on households welfare: the case of Medellin (Colombia) and

Mumbai (India). Paris: MINES ParisTech.

Reyes, E. (2013) Santos pide a las FARC ms ritmo en las conversaciones de paz, in: El Pas. Online. Available on:

hp://internacional.elpais.com/internacional/2013/01/14/actualidad/1358180401_633071.html. Accessed

January 23 2013.

Riin, J. (2000) The Age of Access: The New Culture of Hypercapitalism, Where All of Life Is a Paid-For Experience.

New York: Putnam.

Sarmiento, J. (2011) La arquitectura ha transformado a Medelln, in: El Colombiano. Online. Available on: hp://

www.elcolombiano.com/BancoConocimiento/L/la_arquitectura_ha_transformado_a_medellin/l

a_arquitectura_ha_transformado_a_medellin.asp. Accessed November 11 2012.

Samper, J. (2010) Medelln: The polics of peace process in cies in conict, in: Informal Selements Research.

Online. Available on: hp://informalselements.blogspot.nl/p/medellin.html. Accessed November 11 2012.

Navarro Serch, A. (2010) Stop 2: Medelln, in: FAVELissues. Online. Available on: hp://favelissues.com/2010/01/

27/stop-2-medellin/. Accessed February 27 2013.

Sistema de Informacin para la Seguridad y la Convivencia (2009) Bolen semestral de violencia homicida en

Medelln. Medelln: Alcada de Medelln.

Suarez, Y. (2012) POLI [Photo] Online. Available on: hp://www.ickr.com/photos/81968414@N05/7511525922.

Accessed February 27 2013.

Tongeren, K. van (2011) Transmilenio Avenida de Las Americas [Photo] Online. Available on: hhp://cuentasclaras.

co/wp-content/uploads/bgs/transmilenioWEBf.jpg. Accessed March 17 2013.

The Economist (2013) A load of rubbish, in: The Economist 406 8818, pp. 42.

The Telegraph (2010) [Photo] Online. Available on: hp://i.telegraph.co.uk/mulmedia/archive/01641/

mockus2_1641950c.jpg. Accessed February 4 2013.

Vasquez Zora, L. F. and Villalba Stor, P. (2008) Medellin, ciudad fragmentada. Modernidad, comunicacion y cultura

en la contemporaneidad. Medelln: Fundacion Universitaria Luis Amigo.

Villamil, D. (2011) Biblioteca El Tunal [Photo] Online. Available on: hp://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/