Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

China 8

Transféré par

kritika18081990Titre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

China 8

Transféré par

kritika18081990Droits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Housing

Yingshun

Studies, Vol.

Zhao

18,&No.

Steven

5, 721744,

C. Bourassa

September 2003

722

this reform, the government gradually withdrew from economic activities and

most limitations on private business activities were lifted. Many state-owned

enterprises were privatised, or were transferred into stock companies. SelfChinas Urban

Housing

Reform:

employment,

private enterprises,

foreign

investment Recent

enterprises Achievements

and special

economic

zonesInequities

were encouraged and developed. Competition, material incenand New

tives and decentralisation in decision making were widely used to promote

productivity. The reform produced substantial results and Chinas national

economy started to take off. Entering into the 21st century, China is becoming

a major economic power (Wang & Murie, 1999b; Zhang, 1998).

Before 1980,ZHAO

Chinas&

cities

adoptedC.

a socialist,

work unit-dominated welfare

YINGSHUN

STEVEN

BOURASSA

housing system. This system involved a mixture of three components: socialist

School

of Urban

andphilosophy

Public Affairs,

of Louisville,

426goal

W. Bloom

Louisville,

ideology,

welfare

andUniversity

clan tradition.

The main

of theStreet,

socialist

KY

40208,was

USAto eliminate all defects of modern capitalist society, such as class

ideology

exploitation and con icts, social inequity, growing crime rates and degenerating

[Paper first received 20 July 2002; in final form 29 October 2002]

culture. The way to achieve this goal was to eradicate the root of all these

evilsprivate ownership, by nationalisation or socialist transformation. Under

A

Chinas

urban housing

reformhousing

startedwas

in the

early 1980s,

BSTRACT

this

ideology, most

of Chinas

urban private

transformed

intoas a part of

comprehensive

economic

reform.

old system was

dominated

work the

units that

public ownership

in the 1950s

and,The

subsequently,

public

housing by

became

provided substantial

to their

employees,

including

heavily

subsidised

predominant

form of in-kind

housingservices

provision

in Chinas

cities (Chen,

1996,

1998;

housing.

brought

three

serious

housing

shortages, corruption and inequities.

Wang

& It

Murie,

1996;

Wu,

1996;problems:

Zhou & Logan,

1996).

TheChina

goalsestablished

of housing its

reform

were

to

solve

these

problems

through

urbanashousing

own extensive urban welfare system

after 1949

a

privatisation,

commercialisation

and

socialisation.

This

study

examines

Chinas

symbol of socialist advantages over capitalism. Welfare for urban residents was urban

housing

reform

a case

study

of thesupport

city of to

Jinan.

first reviews

the history of

tied to work.

Thethrough

work units

gave

overall

theirItemployees

from

housing

in Jinan

1950s

to the 1980s,

then

analyses Jinans

cradle todevelopment

grave, including

childfrom

care,the

basic

education,

healthand

care,

pensions,

reform practices

in the

Its finding

that, after

many

years

efforts,

housing

collective

amenities,

life1990s.

employment

andishousing.

Those

who

did not

belong

to

reform inorJinan

made

but mostlyrelief.

with respect

to privatisation.

families

workhas

units

weresubstantial

given stateprogress,

or neighbourhood

Such persons

The

problem

of

housing

shortages

has

been

addressed

and

crowding

has

were very few in number. Organised dependence on work units and state lessened

considerably.

Anecdotalasevidence

suggests

that corruption

is less sector,

widespread

than in the

agencies was regarded

the victory

of socialism.

In the housing

the city

past. Thebureau

other important

housing

problem,

inequity,

still exists

in some respects,

housing

and various

work units

constructed

housing

and and,

administrahas even

worsened.

particular,

a new

form ofThe

horizontal

arisen due to

tively

allocated

this In

housing

to urban

residents.

tenants inequity

paid onlyhas

a nominal

the persistent

role of work

units &

in Murie,

housing1999b;

provision.

This1998).

paper suggests that, in the

rent

for their apartments

(Wang

Zhang,

future,

the

government

should

take

a

more

positive

role

rather

than

thein

market

Chinas clan system has a long history and currently clans are

stillleaving

common

alone

to rural

deal with

of housing

Chinas

areas.the

A problem

typical rural

clan is inequity.

a village where almost all residents

belong to an old family and people live and work together. Clans are considered

K

Wstable

China,

housinginter-personal

policy, reform,

inequity which makes them

ORDS: and

to EY

have

harmonious

relationships,

relatively easy for the government to administer. After 1949, a work unit-based

quasi-clan system emerged in Chinas cities. Work units construct housing

within, or very close to, their compounds, so that their employees can easily get

Introduction

to work. A work unit with housing stock forms a small community or a

Modern Chinas

quasi-clan.

The integration

history canofbework

divided

and into

living

two

is periods:

supposed(1)

to1949

produce

to 1978,

loyalty

theto

traditional

the

enterprise,

socialist

high period,

productivity

and (2)

and1979

a stable

to theurban

present,

society

the reform

(Zhang,period.

2000). In

In the

the

first period,

1970s

and 1980s,

Chinatoestablished

maintain the

andliving

developed

standards

a socialist

of employees

planned economy.

families, the

This

system included

government

evensuch

stipulated

components

that adult

as economic

children could

centralisation,

take on their

nationalisation

parents jobs

or

socialist

if

the parents

transformation,

retired or lost

public

the ability

ownership

to work.

of production means, and a rationed

supply

Generally

of most

speaking,

goods and

Chinas

services

urban

in urban

housing

areas

system

(Zhang,

in the

2000).

first The

period

purpose

was anof

establishing this

unsuccessful

experiment.

system was,

Public

of course,

ownership

to attempt

of urban

to housing

overcome

discouraged

the defectsindiof the

moderninvestment

vidual

capitalist economy.

in housingBut

andthis

resulted

system

in produced

housing shortages.

its own problems,

Welfare such

hous-as

inefficiency,

ing

and its related

a stagnant

administrative

economy allocation

and serioussystem

supplyled

shortages.

to housing

Therefore,

corruption.

in

the late

The

quasi-clan

1970s, China

systemcarried

causedout

a serious

major reform

housingwith

inequity

the aim

among

of accelerating

various work

industrialisation

units.

In the late 1970s,

throughthese

the introduction

problems had

of become

a modern

very

market

serious

economy.

and forced

During

the

0267-3037 Print/1466-1810 Online/03/050721-24

DOI: 10.1080/0267303032000134664

2003 Taylor & Francis Ltd

Chinas Urban Housing Reform

government to carry out reform of the urban housing system. The goals of this

reform were to abolish the three components of the old system and achieve

housing privatisation, commercialisation and socialisation. Privatisation involves

sale of publicly owned dwellings to the tenants; commercialisation involves

establishment of modern urban housing markets where housing is regarded as

a commodity rather than a welfare benefit; and socialisation involves the transfer

of housing management from the control of the work units to professional

companies (in China, socialisation has a different meaning from the Western

understanding, which equates socialisation with nationalisation).

Since Chinas urban housing reform began, there has been a growing body of

research on this topic. The early studies mainly gave a general introduction to

and description of Chinas urban housing system and urban housing reform

(Bian et al ., 1997; Chen, 1996, 1998; Fleisher & Hills, 1997; Tong & Hays, 1996;

Wang, 1995; Wang & Murie, 1996; Wu, 1996; Zhao, 1997; Zhou & Logan, 1996).

After 1998, when the Chinese central government accelerated reform, most

studies tended to address specific issues and new problems faced by the ongoing

housing reform. For example, after 20 years of reform, various work units still

play a key role in the urban housing sector, forming an obstacle to future reform.

Many authors have discussed this problem and urged that the linkage between

work units and housing provision be dissolved. Zhu (2000) argued that the goal

of establishing a market-oriented system of housing development and investment with clear property rights has a long way to go because the work unit is

still in place. Li & Siu (2001) studied residential mobility in Guangzhou and

concluded that the work unit and the municipal housing bureau, rather than

market forces, are the primary driving forces behind suburbanisation in China

today. Rosen & Ross (2000) argued that the resale of privatised public housing

is not feasible because the owners of such housing still rely on their work units

for maintenance and improvements. Moreover, work units are constructing new

housing and employees may exchange their old housing for that new housing.

Li (2000a) posited that Chinas current urban housing market could not replace

the function of work units. Instead, local government would shoulder much of

the housing responsibilities currently resting upon the work units. Fu

(2000) hold the pessimistic viewpoint that weaning urban residents away from

work unit housing is a difficult task because it infringes upon many vested

interests, primarily those of work units, employees and their families.

Wang & Murie (1999a), Lan & Sun (2000), and Li (2000a, 2000b) addressed

construction, sale and management of new private, often referred to as commodity, housing in Chinese cities. Their conclusions were that Chinas urban

housing market was not mature because most developers were state-owned and

few ordinary urban residents are able to buy commodity housing due to its high

price. Chiu (2001) and Zhang (2001) argue that China currently has a dual

system of housing sectors: privatised public housing and commodity housing,

with different prices, rents, and delivery patterns. In this situation, the government should take a more proactive role rather than leaving the market alone to

solve the housing problems of disadvantaged people. A market-oriented policy

does not mean that the government does not need to do anything. Wang (2000)

and Wang & Murie (2000) have also examined Chinese urban housing reforms

impact on the urban poor and housing reforms social and spatial implications,

respectively. In addition, Tang (1994) and Wu (1999) have discussed the impacts

of Chinas urban land system on housing development.

723

et al .

724

Yingshun Zhao & Steven C. Bourassa

This paper explores the new issue of horizontal inequity that has resulted

from housing reform. Previously, a few authors have addressed new inequities

in Chinas urban housing (Lee, 2000; Wang & Murie, 2000; Zhang, 2001). Their

analyses have focused on vertical inequities resulting from the failure to provide

housing for the urban poor or due to the persistence of the rank system for

allocating housing. This paper argues that the new horizontal inequities stem

from the persistence of the work unit system of housing provision. Before

housing reform, there was some inequity in housing conditions among different

work units, but these inequities were not very significant due to the intervention

of the government. But, in the reform era, because of the introduction of market

competition and the withdrawal of the government from the economic sector,

the differences in economic power among work units increased. Some powerful

work units, especially those in monopoly positions, have earned considerable

profits and constructed high quality housing for their employees, while other

work units have been less successful and, consequently, unable to improve their

employees housing. One person may earn only an average income but can have

a good unit of housing because the work unit is powerful. Another person, who

works in a small work unit or a private enterprise without housing stock, or is

self-employed, may earn a good income, but cannot get housing from a work

unit and also cannot afford commodity housing.

Most case studies of Chinese urban housing reform have examined only a few

large cities such as Beijing (Lan & Sun, 2000; Li, 2000a), Guangzhou (Li, 2000a,

2000b; Li & Siu, 2001), Shanghai (Wong, 1998), or Xian (Wang, 1995). These cities

have well developed economies, relatively high personal incomes and more

market-oriented thinking. Housing reform in these cities was carried out relatively early and some of them were selected as pilot cities for urban housing

reform. Their progress in housing reform was greater than that of other Chinese

cities. The subject of the case study here, Jinan, is smaller in population and area

than the above-mentioned cities. Its process of housing reform has been relatively slow. For example, by the end of 1997, the average percentage of

privatised public housing in 36 major Chinese cities (including Jinan) was 60 per

cent, while Jinans was only 31 per cent. By the end of 1998, the national average

rent for urban public housing was 1.51 yuan per sq. metre, while Shanghais

average was 3.05 yuan, Beijings was 2.86 yuan, Nanjings was 2.31 yuan, and

Chengdus was 1.73 yuan. Jinans average rent was only 1.26 yuan. In 1998, the

national average deduction from wages for the Housing Provident Fund was 5

per cent of wages, and some cities had a higher ratio: Shanghai and Tianjin were

6 per cent, and Beijing and Guangzhou were 7 per cent. Jinans average was 5

per cent (4 per cent before 1994). In 1999, the national percentage of commodity

housing purchased by individuals (rather than organisations) was 89.1 per cent,

while Guangzhou was 98.1 per cent, Shanghai was 97.5 per cent, Tianjin was

96.8 per cent, and Beijing was 95.2 per cent. Jinan was only 57.9 per cent

(Yangeng Wang, 2000). These data show that Jinan was different in many

respects from the other, larger cities that have received most of the attention

from researchers. To date, little or no research has been published about second

tier cities such as Jinan.

In addition, Jinan is the capital of Shandong Province, which along with

Guangdong Province had housing reform plans that were unusual in many

respects, especially in regard to the calculation and issuance of one-time purchase subsidies and monthly subsidies. The two plans are believed to be good

Chinas Urban Housing Reform

725

examples by many Chinese scholars and have been cited often in academic

articles and news reports (see Lee, 2000; Li, 1999; Yanjie Liang, 1998; Yongping

Liang, 1998; Wang, 1998; Wong & Flynn, 2001; Xie, 1999). Therefore, study of a

city like Jinan can help to better and more completely explain Chinas ongoing

urban reform.

This is essentially a qualitative study based on information collected in Jinan

in August 2000. The primary data sources include materials from selected work

units, including an industrial firm, a university, a service trades company and

various others. The documents collected include work units housing reform

plans, housing standards and criteria, and educational materials related to

housing reform. In addition, interviews were conducted with individuals in

charge of Jinans housing reform, staff members of work units housing offices,

and city residents holding various types of jobs in different work units. These

primary data were supplemented with various documents published by the

Chinese government, including materials from the city archives section of the

Jinan public library.

The History of Housing in Jinan: 1950s to 1980s

Jinan is located on the Yellow River in eastern China, some 500 km south of

Beijing. In 1998, Jinan City proper had a population of 1.51 million (ranking 15th

among Chinas 668 cities) and a built-up area of 115.6 sq. km (about 47 sq.

miles). Jinans housing includes two large sectors: public and private. Public

housing in Jinan originated in 1949, immediately following the founding of the

new communist city government. At the beginning, public housing was small in

amount but it increased rapidly after the socialist transformation in the mid1950s, which put many private dwellings into public ownership. At that time,

private housing had had a long history and had been the major form of housing

provision. After 1949, development of private housing was limited under the

socialist economic strategy, and that sector gradually came to house a minority

of the citys residents. Public housing may be divided into two sub-sectors:

public housing managed directly by the city government and public housing

managed by various work units. In 1949, private housing, city governmentmanaged public housing and work unit-managed public housing accounted for

76 per cent, 13 per cent, and 11 per cent, respectively, of Jinans housing stock.

By 1998, these figures were 19 per cent, 18 per cent, and 63 per cent, respectively

(Table 1).

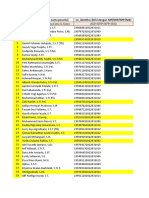

Table 1.

Composition of the housing stock in Jinan: 194998 (1000s of m

Total housing Government- Work unit-

Year space managed housing managed housing Private housing

1949 3985 535 (13%) 438 (11%) 3028 (76%)

1955 4429 549 (12%) 997 (23%) 2882 (65%)

1963 5505 1772 (32%) 1860 (34%) 1872 (34%)

1976 6721 1416 (22%) 4157 (61%) 1156 (17%)

1984 10 370 2602 (25%) 6153 (60%) 1622 (15%)

1998 28 012 5061 (18%) 17 564 (63%) 5395 (19%)

Source: Wang, 1999.

2)

726

Yingshun Zhao & Steven C. Bourassa

City Government-Managed Public Housing

The housing in this sector had three main origins: housing received from other

sources in the late 1940s; private housing converted in the socialist transformation movement in the mid-1950s; and housing constructed since the 1950s. The

new communist city government, which as noted above was founded in 1949,

proceeded to: receive housing from the former city government, the former

ruling party and the old army; confiscate housing from counter-revolutionaries,

political enemies or foreigners; take over housing from private housing owners

for public use; buy housing from private owners; and receive housing donated

by some private owners.

The socialist transformation of urban private housing in Jinan was experimented with in 1956, and carried out on a large scale in 1958. By 1966, the

socialist transformation was basically completed. A total of 1 270 000 sq. metres

of private housing, owned by 6700 landlords, had become government-managed

public housing (Jinan Housing Bureau, 1998). Other Chinese cities also experienced the same process during that period (Wang & Murie, 1999b; Zhang, 1998).

The construction of new public housing started in the 1950s and made great

progress in the 1980s and 1990s. Between 1950 and 1970, a total of 1 189 000 sq.

metres of public housing was constructed. This new housing was mainly

one- oor houses or simple two- or three- oor apartment buildings, with public

toilets and tap water. In the 1980s and the 1990s (the reform era), the public

housing stock increased rapidly and a total of 3 370 000 sq. metres was constructed. The newly-constructed houses in this period were mainly four- to

six- oor apartment buildings with modern facilities, including individual

kitchens, toilets, independent water and electricity meters, halls and balconies.

City government-managed public housing was allocated according to housing

need. To be eligible, applicants had to be legal city residents, had to live in very

crowded conditions, and had to present letters from their work units verifying

that the work unit could not provide housing. The Housing Bureau reviewed all

applications at regular intervals and made housing allocation decisions after

balancing the housing needs of all applicants. Typically, it was very difficult for

city residents to get public housing because of serious housing shortages, and

the waiting time was very long. Due to relatively limited investment, the public

housing managed by the city government was often smaller and simpler than

the public housing managed by various work units. City residents usually asked

for housing from their work units before applying to the city government. Only

those who were self-employed or those working in small work units went

directly to the Housing Bureau (Zhang, 1998).

The city government implemented unified rents for public housing. In theory,

these rents were also applicable to the public housing managed by various work

units. In practice, work units ignored the official rates and established their own

rents, which often benefited their employees because they were lower than the

governments guidelines. Between 1948 and 1977, the city government issued

five rent guidelines and the average rents changed slightly following the

issuance of each guideline. In comparison with the average incomes of urban

employees, rents remained more nominal than substantive. For example, in 1977,

the rent of a standard room (about 12 sq. metres) was about 1.30 yuan, which

made up only 2.7 per cent of the average monthly wages of a typical employee.

In the 1990s, when urban housing system reform started in Jinan, the rent began

Chinas Urban Housing Reform

Table 2.

Rents of government-managed public housing, wages, and

living spaces per person in Jinan: 19482000

Average

Year of Monthly rent monthly urban Housing space Ratio of rent

guideline (yuan/m

) wages (yuan) (m

/person) to wages (%)

1948 0.138 22.5 4.09 2.49

1951 0.192 36.8 3.83 2.01

1959 0.143 49.1 3.27 0.96

1968 0.171 45.8 3.41 1.27

1977 0.108 48.2 4.05 0.91

1992 0.324 225.8 7.62 1.09

1994 0.900 394.7 7.92 1.80

1998 1.268 693.8 9.77 1.78

2000 6.750 937.3 10.48 7.50

Sources:

Jin, 1999; Jinan Annals Office, 2001.

to be raised significantly. Because income also increased, rent continued to

account for only a small part of average monthly wages (Table 2).

Work Unit-Managed Public Housing

Public housing managed by work units has two main origins: housing received

and bought in the early 1950s, and housing newly-constructed by various work

units from the late 1950s to the present. After the 1949 Communist Revolution,

the government started the process of nationalising private enterprises and

many state-owned enterprises were founded. These work units established their

own housing stock for their employees by receiving housing from the old

government-owned enterprises and buying private housing. From the mid1950s, Chinas national economy began to develop and the number of urban

employees increased rapidly. The great demand for urban housing pushed

various work units to construct housing for their employees. The government

encouraged work units to do this in order to rapidly solve the problem of

housing shortages. Many previous limitations on work units housing construction activity were lifted, and work unit-managed public housing expanded

rapidly.

Public housing managed by the city government and public housing managed

by various work units share some characteristics, such as administrative allocation and nominal rent. They also have many differences. First, the city government-managed public housing is scattered throughout the whole urban area and

is provided to legal city residents, while the work unit-managed public housing

is typically close to each work unit and is supplied only to employees. A tenant

of government-managed public housing may remain in place regardless of a

change of employer, but a tenant of work unit-managed public housing would

have to move out under such circumstances. Second, government-managed

public housing has unified criteria for construction (regarding selection of

location, house design and structure, and cost), maintenance and management,

while various work units might construct and manage their housing without

regard to official standards. Thus there are great differences in housing conditions across various work units. Third, although both of them collect a nominal

727

728

Yingshun Zhao & Steven C. Bourassa

Table 3.

Rental rates of selected work units in Jinan,

1985

2

Work unit Rental rate (yuan/m

Public utility 0.055

Factory 0.065

Machine tool factory 0.070

University 0.070

Post office 0.095

Government-managed public housing 0.108

Source: Jinan Housing Bureau, 2000.

rent, the government-managed public housing complies with a uniform rent

guideline, while each work unit has its own rent-setting criteria. As mentioned

previously, the rents for work unit-managed public housing are usually lower

than those for government-managed public housing (Table 3).

Fourth, although both types of housing are allocated administratively, the

allocation principles are very different. Government-managed public housing is

allocated according to housing need and priority is given to those living in the

most crowded conditions. In work units, housing is used as an incentive to

reward employee efforts and to promote employee productivity. For this purpose, two allocation systems, the rank system (each rank is entitled to a certain

amount of housing) and the point system (for priority of allocation within the

same rank), were invented and used widely in various work units (Wang &

Murie, 1999b; Zhang, 1998). Housing conditions such as crowding and inconvenience were not taken into account (Tables 4 and 5).

Private Housing

In 1955, just before the socialist transformation began, Jinan had nearly 2.9

million sq. metres of private housing, making up 65 per cent of all housing in

the city. Most private housing consisted of simple one- oor buildings. In early

1956, the central government issued

Some Ideas on the Current Basic Situation of

Urban Private Housing and the Socialist Transformation Movement

. This defined the

goals for, significance of, and schedule for this movement, and asked all cities to

commence the transformation. Following this directive, the Jinan government

began an experiment in the Shi-Zhong district. This experiment adopted two

models: joint state-private ownership and private ownership with state manage-

Table 4. Ranks and housing entitlements in a

prosperous work unit in Jinan, 1992

Rank Entitlement (m

Ordinary workers and staff 4550

Junior professionals and officials 5055

Middle professionals and officials 6070

Senior professionals and officials 8090

Source: Jin, 1999.

Chinas Urban Housing Reform

Table 5. The calculation of housing allocation points at

a university in Jinan, 1988

Basis for calculation Points

Rank

Ordinary worker or staff 35

Teaching assistant or assistant section chief 40

Lecturer and section chief 45

Assistant department head 50

Associate professor and department head 55

Professor and associate commission head 65

Time on the job

1/year

Other considerations

Model teacher 2

Husband and wife working in same unit 1

Two children over 12 years old of opposite gender 1

Family member in military service 1

Only one child 1

Source: Yangeng Wang, 1999.

ment. The city government stipulated that: (1) Owners of over 600 sq. metres of

private rental housing should participate in the transformation, and their housing, except for a few rooms for the owners living spaces, should be transferred

into joint state-private ownership. This housing should be assigned a price by

the Housing Bureau, and a fixed 0.5 per cent interest payment, based on the

price, would be given to the owner on a monthly basis. Tenants would pay rent

directly to the Housing Bureau. (2) Owners of over 360 sq. metres of private

rental housing should participate in the transformation, and their housing,

except for a few rooms for the owners living space, would be transferred into

state management. The Housing Bureau would collect rent from the tenants at

a rate established by the city government. After withdrawing 18 per cent for

property taxes, 25 per cent for maintenance fees, and 10 per cent for management and insurance fees, the Housing Bureau would give the remaining rent

revenue (called the fixed rent) to the owners. (3) Owners of smaller amounts of

rental housing might participate in the state management programme if they

wanted and if they did not make their living mainly from rental revenue.

In the experiment, a total of 51 300 sq. metres of private housing was

transformed, of which 43 800 sq. metres was transferred into joint state-private

ownership and 7 500 sq. metres was transferred into state management. After

this experiment, owners of another 22 800 sq. metres of private housing expressed their desire to participate in the transformation and the Housing Bureau

met their demands. Therefore, during this period, a total of 74 100 sq. metres of

private housing was transformed.

In 1958, the city government issued

An Idea on the Socialist Transformation of

Private Housing

, which called for a full-scale transformation. Based on the

previous experiment, it made some important modifications. The joint stateprivate ownership pattern was given up. The rental housing owned by churches,

temples and mosques was required to be transformed; however, rental housing

owned by Chinese people living overseas would not be transformed. Rent was

729

730

Yingshun Zhao & Steven C. Bourassa

set at 20 to 40 per cent of the original rent. Due to the previous experiment and

substantial preparatory work, the full-scale transformation was completed very

quickly. In total, 1 040 000 sq. metres of private housing, owned by 5100 persons,

was transformed, consisting of 85 per cent of the housing eligible for transformation. Of all the transformed private housing, 29 200 sq. metres were not eligible

but the owners insisted on participating. A total of 177 200 sq. metres was not

transformed because of poor quality. The average fixed rent was just 27 per cent

of the original rent.

In 1964, the central government issued

A Report on Problems of the Socialist

Transformation of Urban Private Housing

. This report asked for further efforts to

transform the private housing of those owners who were eligible but did not

participate in the 1958 full-scale transformation. Following this report, the Jinan

government started a new wave of transformation. By 1966, another 154 400 sq.

metres of private housing had been transformed (Jinan Housing Bureau, 1999).

In 1975, when China was undergoing the Cultural Revolution, private housing

was further reduced until it accounted for only 7 per cent of all city housing. In

the reform era of the 1980s and 1990s, the government encouraged individuals

to construct housing by themselves. Private housing rose to 19 per cent of the

citys total by 1998. In this period, some two- and three- oor modern-style

private houses were built.

During the 1950s, the Jinan government issued three rent regulations for

private rental housing. These regulations divided private rental housing into

different classes according to location and construction materials and quality.

Rent ranges for each class were fixed, but the tenant and the landlord were still

expected to negotiate the actual rent, which often was higher than that for public

rental housing. The last regulation, issued in 1956, was in effect for almost 30

years. Entering into the 1980s, private rents started to rise significantly, following an increase of migration from rural to urban areas caused by the new

economic growth. In this period, the government did not issue any new rent

regulation and instead allowed the rent to be decided on the market. In practice,

the rent usually was negotiated between the landlord and the tenant based on

current prices of basic commodities. Currently, private rent is usually two times

higher than that for public housing, or about 50 to 100 yuan per room (Zheng,

1999).

Urban Housing System Reform in Jinan in the 1990s

The welfare housing system, with its administrative allocation and nominal rent,

could not support itself and maintain normal investment. Under the overarching

principle of production first, with consumption a distant second, China had for

a long time neglected investment in housing. As a consequence, housing supply

did not increase to meet the growing demand for housing. The resulting

shortage created severe problems in Chinese cities. In Jinan, living space per

resident declined during the 1950s, and by the late 1970s had returned only to

the levels of the late 1940s (Table 2). In 1982, Jinan had 1.45 million sq. metres

of housing in urgent need of repair, of which 415 000 sq. metres of housing was

near collapse. Of Jinans approximately 300 000 families and unmarried adults,

161 700 (54 per cent) had housing problems. Among them, 101 400 did not have

any housing and had to live with parents or relatives, or in offices or workshops;

Chinas Urban Housing Reform

14 700 lived in inconvenient conditions (unmarried adults of opposite gender

lived in the same room); and 45 600 lived in very crowded conditions (Ye, 2000).

Inequity in housing consumption was very serious. In 1979, while the average

living space per capita was 4.06 sq. metres in Jinan, 4 500 households lived in

extremely crowded conditions with average living space of less than 2 sq. metres

per person. In some cases, several generations had to live in a single room.

Under the rank allocation system, ordinary people had no opportunity to live in

adequate housing. At a university in Jinan, it was not uncommon to find many

older workers living in small houses with shared kitchens and toilets, and even

two families sharing a single unit. The work unit management of housing also

resulted in great housing differences. A young university graduate working in

a prosperous company might be allocated a two-bedroom apartment when he

married, while his classmate working in an academic institution might obtain

only a one-bedroom apartment. Many city residents lived in very crowded

housing conditions only because they were self-employed or employed in poor

or small work units.

On the other hand, essentially free public housing with nominal rent resulted

in excess demands because living in larger or better housing did not entail

greater costs to the tenant. Allocation of housing managed by the city government and some work units did not follow a rank system, but instead relied on

administrative discretion. This administrative allocation system led to grave

housing corruption and many officers used their powers to get extra free public

housing, even to the point of acquiring housing for their unborn grandchildren.

A junior officer of the urban district government, who was in charge of

personnel affairs, got four units of housing for his four unmarried sons. These

units were government-managed and scattered in different locations. In another

work unit, about half of 36 units in a new apartment building were mysteriously

empty for several years. These units were reserved for young children or

grandchildren of some of the leaders of the work unit.

These kinds of problems led to resentment by the public and low productivity.

Entering into the 1980s, China started large-scale economic reform. A market

economy was introduced to replace the planned economy, and private enterprises were encouraged. The urban housing system, because of its severe defects,

also became a target of urban reform. In the early 1980s, urban housing reform

experiments took place in many Chinese cities. In Jinan, the city government

carried out some small-scale housing reform programmes in the mid-1980s,

including reorganising housing management systems, selling newly-constructed

commodity housing with subsidies, opening youth apartments for young married couples without their own housing, and experimental sales of old public

housing.

Jinans urban housing reform was formally implemented in 1992 when the city

government issued a

Temporary Plan for the Jinan City Housing System Reform

This plan implemented the central governments

National Plan for Urban Housing

System Reform

issued in 1988,

Notice of Continuing to Carry Out Urban Housing

System Reform

issued in 1991, and the housing reform plans of Shandong

Province. Following Jinans temporary plan, and other directives issued later, a

set of housing reform programmes was carried out. They included raising rent

for public rental housing, establishing the Housing Provident Fund, initiating

comfortable housing projects and selling public housing. The following sections

discuss each of these initiatives.

731

732

Yingshun Zhao & Steven C. Bourassa

Rent Increases

The nominal rent of public housing was a main defect of the old housing system

and the main origin of many housing problems. Therefore, raising rent has been

an important aim of housing reform. In 1992, the Jinan city government started

to raise the rent of public housing. The city government issued a

Notice of Raising

Rent and Issuing Housing Subsidy

that asked the Jinan Housing Bureau and work

units to uniformly raise the rents for all public housing. At the same time,

housing subsidies should be issued to employees who lived in public rental

housing. The amount of this housing subsidy would be 2 per cent of the

employees monthly wages. Those who lived in units larger than the entitlements for their ranks would pay a punitive rent for the extra housing space.

Ordinary workers and staff were entitled to 50 sq. metres, middle officials and

professionals to 70, and senior officials and professionals to 90. The punitive rent

was 1.56 yuan per sq. metre. After this increase, the average rent of public

housing rose from about 0.11 to about 0.32 yuan per sq. metre.

In 1994, the city government issued

The Decision on Jinans Urban Housing

Reform , which further raised the rent of public housing. The new space entitlements for each rank were 65 sq. metres for ordinary workers and staff, 75 sq.

metres for junior officials, 90 sq. metres for middle officials and professionals,

and 120 sq. metres for senior officials and professionals. The punitive rent

for using extra space was increased to 2 yuan per sq. metre. The new regulation

had provisions giving exemptions in hardship cases. After this increase in

rent, the average rent of public housing in Jinan rose to about 0.77 yuan per sq.

metre.

In 1998, the city government issued a

Plan for Further Promoting Housing

Reform, which further raised rents. Punitive rent was raised to 3 yuan per sq.

metre. Households could apply for a special rent subsidy from their work units

if their rents were more than 9 per cent of monthly income; households whose

monthly income per person was less than 130 yuan were allowed to pay only 70

per cent of the newly raised rent. After this increase in rent, the average for

public housing in Jinan rose to 1.27 yuan per sq. metre (Jinan Housing Reform

Office, 1999). In 2000, the rent was raised again and the average for public

housing reached 6.75 yuan per sq. metre. At that time, the market rent in Jinan

was about 20 to 30 yuan per sq. metre (Jinan Annals Office, 2001). Khan

et al .

(1999) show that, across urban China, housing subsidies dropped from about 18

per cent of household income in 1988 to less than 10 per cent in 1995.

The Housing Provident Fund

Chinas housing provident fund system started in 1991, and it followed the

model of the Singapore Central Provident Fund in some respects. A key

difference is that the Singaporean scheme provides broad social insurance while

the Chinese approach provides only for housing. Before the reform era, Chinas

urban welfare housing system resulted in a severe drain of the housing fund and

housing shortages. One of the objectives of the urban housing reform was to

replace this dysfunctional system with one that required employees to bear a

large part of the cost of housing. The provident housing fund is a compulsory

saving programme. It forces employees to spend part of their wages on housing

Chinas Urban Housing Reform

733

in order to solve the problem of housing shortages. It also provides employees

with a source of housing finance in a new market housing system.

The Shanghai government started the first housing provident fund in 1991. It

required each employee to contribute 5 per cent of monthly wages to this fund;

the work unit would contribute another 5 per cent. The fund could be used only

for the construction and purchase of housing. Since then, many Chinese cities

have joined this trend. In 1994, the central government issued a

Guideline for

Provident Housing Funds

, which required all Chinese cities to initiate such a fund

as soon as possible. The guidelines stipulated that the fund should be deposited

at a designated bank and could earn a specified, low rate of interest. The fund

would be managed solely by a centre dedicated to that purpose in each city. The

fund might be used for the following purposes: lending to work units, government or developers for constructing housing; supporting employees in housing

purchases, construction, and renovation; and providing mortgage loans to

employees. By the end of 1999, all of the 203 large- and medium-sized and most

of the 465 small Chinese cities had started provident housing funds. These funds

had attracted 69 million participants and raised 140.9 billion yuan. At the same

time, 15.8 billion yuan in mortgage loans were provided to individuals by the

funds (Ye, 2000).

Jinan started its fund in 1993 when the city government issued

Management of

the Provident Housing Fund of Jinan

.Itrequired all work units to participate in the

fund. Work units and employees would each contribute 4 per cent of monthly

wages, and this ratio might be adjusted upward later depending on economic

growth and wage increases. Delay in payment into this fund by work units

would accrue a 0.5 per cent fine each day. The fund would earn interest and,

after 10 years, employees might withdraw the money they paid in the first year

(after 11 years, they could withdraw the money paid in the second year, and so

on).

In 1994, the city government decided that the employees and work units

contributions to this fund would each be raised to 5 per cent of wages. For

foreign investment enterprises, the contributions would each be 8 per cent of

wages. The government urged those work units that still did not participate in

the fund to do so. Starting in 1995, the city government would force work units

to participate in the fund. In 1997, the city government issued a

Notice of Loan of

the Provident Housing Fund

, which stipulated that employees who participated in

the fund could apply to the fund for home purchase loans. To be eligible for

these loans, an employee had to have a stable job, have invested in the fund

more than 30 per cent of the house price, and have agreed to use the fund

exclusively for buying a house. The amount of these loans could not exceed

50 000 yuan, and their terms were typically 5 to 10 years, and at most not more

than 15 years. Their terms also could not extend beyond an employees typical

retirement date. The interest rate on these loans would be 2 per cent higher than

the rate for a fixed three-month deposit set by Chinas central bank.

In 1998, the city government issued a notice reconfirming that work units and

employees contributions to the fund were each 5 per cent of wages and for

foreign investment enterprises the contributions were 8 per cent. This notice also

suggested that, for some rich or prosperous work units, the contributions could

be raised to 6 or 7 per cent on a volunteer basis. For some poor and depressed

work units, the requirement could be decreased to 4 per cent. For the work units

that still did not participate in the fund, punitive actions would be taken,

734

Yingshun Zhao & Steven C. Bourassa

including disapproval of their housing construction projects, refusal to allocate

land to them for housing construction, not allowing them to enjoy benefits from

the policies for housing reform, and prohibiting them from buying vehicles and

newly-constructed commodity housing. With these measures, the housing provident fund made rapid progress. Since 1996, the value of the citys fund has

grown at an annual rate of 20 per cent. By the end of 1999, 89 per cent of work

units in the Jinan area participated in the fund, and its value had reached 900

million yuan. Almost all employees have used their investments in the fund to

buy public housing.

The Comfortable Housing Project

In 1994, Jinan was designated by the central government as a pilot city for a

five-year Comfortable Housing Project. Subsequently, the city government

issued an

Implementation Plan for the Comfortable Housing Project of Jinan

Comfortable Housing was designed to be good quality, affordable housing for

low-income urban households. Through this project, by the end of the 1990s, all

of the citys low-income households with housing problems (such as crowding)

were to have been able to buy or rent a unit of comfortable housing. The Jinan

Housing Bureau was designated to handle the construction and sale of comfortable housing. This kind of housing was to consist mainly of two-bedroom

apartments. Funds for the project came from: housing development companies

in the Jinan area; housing funds of city and district governments; the provident

housing fund; work units revenues from the sale of their public housing; and a

special appropriation for comfortable housing from the central government. The

city government would also support this project by remitting some regular fees,

such as those for infrastructure, education, commercial facilities, electricity and

water, and the tax on new construction materials.

Comfortable housing would be sold to work units or individuals at a low cost

price. The components of cost price included survey, design and project preparation fees, construction fees, land cost and management fees. Work units

might resell this housing to their employees at a discounted price equivalent to

the sale price of their existing public housing. Work units also might rent this

housing to their employees at cost rent, if these employees did not have the

financial ability to buy. Families who wanted to buy this housing had to meet

two basic requirements: (1) they must have been low-income (less than 130 yuan

per person per month) and (2) they must have been living in very crowded

conditions (less than 4 sq. metres of living space per person), or in very

inconvenient arrangements (having unmarried adults of opposite gender living

in a single room), or have had no housing of their own.

In 1995, the Housing Bureau started to construct the first comfortable housing

subdivision. By the end of 1999, the Comfortable Housing Project had invested

980 million yuan and completed construction of 900 000 sq. metres. This housing

was sold at cost price to poor households with housing difficulties. Special

priority was given to teachers at elementary and middle schools, and retired

workers and staff who lived in poor conditions. The city government also issued

special housing loans for low-income families. By 1999, of 24 500 low-income

households with housing problems in Jinan, 10 800 had bought or rented

comfortable housing.

Chinas Urban Housing Reform

Sale of Public Housing

Sale, or privatisation, of public housing was the first goal of urban housing

reform and had been emphasised by the government many times since the start

of housing reform in the early 1980s. But because the sale of public housing

affected vested interests of the government, work units and individuals, progress was slow. In 1994, after a few experiments with selling public housing in the

1980s, the city government issued

Ideas for Implementing the Decision on Urban

Housing Reform of the Central Government

.Itdefined three tasks for the citys

future housing reform: developing the housing provident fund, raising rent, and

selling public housing. On the sale of public housing, the directive outlined the

general regulations for sale of housing, such as calculation of prices, calculation

of discounts, buyer eligibility, payment patterns, forms of property rights, and

maintenance of sold housing. Subsequently, in 1996 and 1998, the city government issued two more detailed regulations for the sale of public housing. These

regulations played important roles in the privatisation of public housing in

Jinan.

The 1994 regulation stipulated that, in principle, all public housing might be

sold, except: (1) old public housing located in the revitalised areas of the city; (2)

physically dangerous public housing; and (3) public housing over which there

was controversy between the city government and work units regarding property rights. Public housing would be sold at one of three possible prices: for

high-income households, public housing would be sold at the market price; for

middle-income households, at the cost price; and for low-income households, at

the standard price. The different prices would bring different housing property

rights. In Jinan, most urban workers and staff were defined as members of

middle- or low-income groups, and they were allowed to pay the cost or

standard prices when buying housing.

The components of the cost price included compensation for land acquisition,

demolition, design and project preparation fees, construction fees, infrastructure construction fees, housing management fees, interest on housing

construction loans and tax. In 1994, the city government fixed cost price at 845

yuan per sq. metre of gross oor area. The standard price was set at 570 yuan

per sq. metre, which was 9.8 times the average annual wages of a worker

divided by 56 (the size in sq. metres of a standard housing unit). By this price,

a standard two-bedroom house would cost three or four times the average

yearly income of an ordinary urban household with two incomes. This ratio was

said to be normal in foreign countries. Both prices were adjusted for location,

orientation (facing toward or away from the sun), and oor level. Cost or

standard prices for old public housing would be discounted 2 per cent per year

of age. Housing space beyond the entitlement for the buyers rank would not be

sold at cost or standard prices, but at market price, regardless of the buyers

income.

When tenants bought housing at the market price, they would get full

property rights, and might resell their housing and gain all sale revenue. When

tenants bought housing at the cost price, they were allowed to resell only after

five years occupation, and were required to repay any profit from the increased

value of the land. When tenants bought housing at the standard price, they

could occupy and use their housing, but not rent it out. These buyers also might

resell their housing after five years occupation, but only to the original owners

735

736

Yingshun Zhao & Steven C. Bourassa

Table 6.

Housing prices in 1996

Guidelines

(yuan/m

Reinforced concrete

Reinforced concrete foundation and brick Crushed stone and

foundation and wall wall brick wall

Terrazzo Cement Terrazzo Cement Terrazzo Cement

Price class oor oor oor oor oor oor

Market 1869 1635 1352 1139 1070 1011

Cost 1168 1022 845 712 669 632

Standard 768 690 570 535 503 475

Bottom-line 290 250 210 170 150 125

Source: Jinan Housing Reform Office, 1996.

(the city government or work units) and only for 67.5 per cent of the market

value.

Some home buyers were eligible for subsidies and discounts. They included:

(1) a housing purchase subsidy based on length of employment (3.40 yuan per

year for both husband and wife, per sq. metre of housing gross oor area); (2)

a 2.5 per cent discount for buyers who were the current tenants; and (3) an 18.5

per cent discount for payment in a lump sum. The housing sale revenue, after

withdrawing 15 per cent for a maintenance fund, would enter into the housing

fund of each work unit. This fund would be used exclusively for housing

construction and housing reform. Maintenance of the private spaces would be

the responsibility of the buyers, while maintenance of the public spaces would

be the responsibility of the sellers with the help from the maintenance fund.

The 1994 regulation did not produce significant results. There were two

reasons. First, at that time, traditional welfare housing thinking was still very

strong and most employees were hesitant about investing in private property; at

the same time, most work units still constructed housing and rented it to

employees at well below cost. Second, the purchase subsidies and discounts

were not sufficiently attractive and buyers had to pay a considerable amount

(sometimes, all of the family savings) to purchase homes. By the end of 1995, of

about 350 000 units of public housing in Jinan, only 16 500 (4.7 per cent) were

sold. Most of the buyers were rich self-employed or high-income households.

A regulation issued in 1996 provided more detailed and effective rules

regarding the sale of housing. According to this regulation, all saleable public

housing was divided into six classes, and market, cost, and standard prices were

fixed for each class (Table 6). Some very poor quality housing was to be sold

with a ten per cent discount in addition to the other subsidies and discounts.

After deducting all subsidies and discounts, the housing price could not be less

than a bottom-line price. This would prevent the over-discounted sale of public

housing in favour of the employees at the expense of the state. Households that

had a yearly income of more than 39 000 yuan or had a per member yearly

income more than 13 000 yuan had to buy public housing at the market price;

other households might buy housing at the cost or standard prices.

Given that most public housing was old and in need of maintenance, sellers

were required to contribute to a maintenance fund. The fee was calculated at 10

yuan per sq. metre of gross oor area for new houses, with a 2-yuan increase for

each year of housing age, but the highest rate could not be more than 40 yuan

2)

Chinas Urban Housing Reform

per sq. metre. In addition, the discount for a lump sum payment was increased

from the previous 18.5 per cent to 20 per cent, and the discount for current

tenants was increased from the previous 2.5 per cent to 5 per cent.

Also in 1996, the city government issued

The Notice on Maintenance of Sold

Public Housing . This notice clarified the regulations on the maintenance of sold

public housing. They included the definitions of private space and public space

in apartment buildings, maintenance methods, payment patterns for maintenance, con ict resolution between owners and maintenance companies, and

punishment for improper use of housing. This notice recommended establishing

a housing management committee in each work unit or neighbourhood, consisting of representatives of housing sellers and buyers. This committee would

make decisions on the selection of a maintenance company, examine the companys maintenance plan, and supervise maintenance works.

In comparison with the previous regulation, the 1996 regulations gave more

benefits, such as housing maintenance fees paid by sellers and higher purchase

discounts, to housing buyers. In addition, maintenance of the sold housing,

which had been a main concern for ordinary housing buyers because most

public housing was old and the maintenance costs were very high, was addressed in detail by the government. Therefore, following the issuance of the

regulation, more tenants bought their housing. During 1996 and 1997, another

91 000 units of public housing (26 per cent of all urban public housing) were sold

in Jinan. But the majority of Jinans households maintained an attitude of wait

and see, because purchase costs were still high compared with incomes.

In early 1998, Chinas new central government reviewed the long-term and

small-progress urban housing reform and made a determination to accelerate

change. It ordered all city governments and work units to stop the payment of

wages in kind through the housing system by the end of 1998, and to make

further efforts to privatise urban public housing. In response to this, the Jinan

government, based on the provincial housing reform plan of the same year,

issued another housing sale regulation. In comparison with the previous two

regulations, the new one incorporated an important difference: it greatly increased the amount of housing purchase subsidies in order to encourage

individuals to buy public housing: (1) the monetary amount of the subsidy

increased from the previous 3.40 yuan to 6.49 yuan per sq. metre and (2) the

calculation of this subsidy was not based on the actual gross oor area of the

house that one wanted to buy, but on the entitlement for ones rank. Given that

the entitlement was often larger than the actual housing space a household

occupied (and, typically, wanted to buy), the increase in the purchase subsidy

was significant. For some old or high-ranking buyers, the subsidies fully offset

the prices of the dwellings, and some buyers could even qualify for subsidies

greater than the purchase prices. In the latter case, the surplus would typically

be kept by the work unit and used for housing improvement in the future. In

addition, from the end of 1998, a monthly housing subsidy would be issued to

the employees. The amount of this subsidy was 25 per cent of the monthly

wages of each employee. It was not given directly to employees but was

deposited in a special account in the name of the employee in a designated bank.

It could be used only for the purposes of housing purchase, maintenance, or

rent. In addition, from the end of 1998, along with the improvement of peoples

income, the standard sale price would be abolished.

Because of significantly increased housing purchase subsidies, growing

737

738

Yingshun Zhao & Steven C. Bourassa

accumulation in the housing provident fund, and the new monthly housing

subsidy, the sale of public housing became a free or almost free allocation in

many cases. Following this regulation, a wave of housing privatisation took

place in Jinan and substantial progress was made. By the end of 1998, about

124 000 units of public housing (35.6 per cent of all public housing in Jinan) were

sold. By the end of 1999, a total of 280 000 units of public housing (80 per cent)

had been privatised (Jinan Housing Reform Office, 1999).

The Continuing Challenge of Housing Inequity

The reform of the public housing system in Jinan has been carried out for over

10 years, and the achievements are significant. The rent for public housing

increased from an average of 0.11 yuan per sq. metre of living space before the

reform to 6.75 yuan per sq. metre in 2000. The housing provident fund has been

established and is playing an important role in housing reform. Before the

reform, Jinan did not have any work unit with such a fund. But by the end of

1999, 89 per cent of work units in the Jinan area participated in the fund, and its

total value had reached 900 million yuan. From 1996 to 1999, the Comfortable

Housing Project had raised 980 million yuan and completed construction of

900 000 sq. metres. A total of 10 800 low-income households with housing

problems had benefited from the project. The average living space per person in

Jinan had increased from 3.7 sq. metres in 1976 to 10.48 sq. metres in 2000.

Households living in extremely crowded conditions (with less than 2 sq. metres

per person) no longer existed, and among 48 200 households living in very

crowded conditions (less than 4 sq. metres per person), the majority had

significantly improved their housing conditions. The quality of housing has also

been greatly improved; private kitchens, toilets, gas, tap water and telephones

have become common in most ordinary houses. The sale, or privatisation, of

public housing had been a stunning success; by the end of 1999, about 80 per

cent of city public housing had been sold. Along with the reduction of in-kind

payment of wages in the form of subsidised rents, corruption in housing

consumption was significantly diminished. Based on these observations, it might

be concluded that housing reform in Jinan has led to significant achievements

and that the housing conditions of most urban residents have been improved.

However, another problem, housing inequity, still exists in Jinan, and has

even worsened in some cases. Under the old system, housing disparities involved inequity within the work units caused by the different social ranks of

each employee (vertical inequity), and inequity across different work units

caused by differences in the economic power and administrative rank of the

work units (horizontal inequity). During the housing reform era, inequity still

existed because work units continued to dominate housing provision and the

rank allocation system was still in place. But horizontal inequity across different

work units worsened. This trend has been taking place within the context of

widening inequality in household income in urban China. Khan

document a sharp increase in income inequality between 1988 and 1995. During

the same period, housing subsidies became less equally distributed, with 41 per

cent of subsidies in 1995 received by households in the top 10 per cent of the

income distribution. The distribution of income from rental housing in 1995 was

even more unequal than the distribution of subsidies. Khan

conclude: Housing policy (privatisation and subsidies combined) accounted for

et al . (1999)

et al . (p. 299)

Chinas Urban Housing Reform

37 per cent of overall inequality in the distribution of income in urban areas in

1995 compared with about 30 per cent in 1988.

In Jinan, there are some powerful work units that have used their powers to

construct very luxurious apartments within their compounds, in order to favour

their employees and promote productivity. The housing conditions of employees

in these work units improved rapidly in the reform era. Their apartments are

well decorated and equipped by their work units with many modern facilities,

such as air conditioners, hot water heaters, modern kitchen equipment and even

Internet connections, which are not common in Jinans ordinary homes. These

luxurious apartments have been sold to employees at very favourable prices. In

Jinan, such new and luxurious apartment high-rises are very conspicuous. These

buildings often belong to banks, government departments, and some enterprises, such as electricity, postal and telecommunication companies that take

advantage of their monopoly positions to raise huge profits. This type of

housing forms a sharp contrast with the housing of other urban residents.

At the same time, Jinan still has about 70 000 households with housing

problems, including 18 900 households living in very crowded conditions, 19 000

living in inconvenient conditions, and over 32 000 with no housing and living

with their parents (Yangeng Wang, 2000). Most of these households are employed in small work units, such as retail stores, elementary schools, small

factories and depressed state-owned enterprises. These work units cannot provide any housing or financial support to help improve their employees housing

conditions. Other workers are self-employed or employed in private enterprises

without any housing stock. These people also do not have the financial ability

to buy housing on the market. In a survey of 273 work units of Jinan in 2000,

there were 17 big units with more than 500 employees, 94 medium-sized units

with 100 to 500 employees, and 162 small units with less than 100 employees. All

of the big work units had their own housing stock. Among medium-sized work

units, 78 (83 per cent) had their own housing. But among small work units, only

55 (34 per cent) had their own housing.

In one such small work unit without housing stock, seven out of 29 employees

(all of whom were married) did not have their own housing and had to live with

their parents. Given the general housing conditions of Chinas urban residents,

it is extremely crowded and inconvenient for married children (often with their

own children) to live with their parents. Six employees lived in expensive, but

simply appointed, private rental housing. Although the government encouraged

the development of private housing, ordinary city residents often do not rent

such housing because the cost is too high, with average rents some two or three

times higher than those of public rental housing. Another seven employees lived

in old public rental housing owned by the Jinan Housing Bureau; three of them

lived in crowded conditions (less than 4 sq. metres of living space per family

member). Finally, nine employees lived in their own housing, most of which was

outdated. In 1998, the average per capita living space within these employees

households was 6.1 sq. metres, while the average living space per capita in Jinan

as a whole was 9.7 sq. metres.

An example of the poor-quality housing occupied by employees of less

prosperous work units can be found in Jinans Lixia District. A total of 32

households live in a four-storey residential building, owned by the Housing

Bureau. Each apartment has two small rooms (about 10 sq. metres) and a very

small kitchen (about 3 sq. metres). The kitchen has neither tap water nor gas. On

739

740

Yingshun Zhao & Steven C. Bourassa

the public hallway on each oor, there is a public water tap and a public bedpan

with no water supply. It is very crowded and inconvenient waiting to get water

and use the bedpan in the morning and evening, and the smells are very

unpleasant. All employed members of these 32 households work in poor work

units, such as small factories and companies, department stores, middle and

elementary schools, small hotels and restaurants and salvage yards. In the early

1980s, this building accommodated some households whose members worked in

government institutions or big enterprises. Later, their work units constructed

newer and larger housing, and those households moved out. Now, the only

hope of the remaining households in this building is that, when this building

becomes older and unsafe, the government will demolish it and the residents

will be allocated better quality subsidised housing.

Another example can be found in the Shizhong District in the inner city of

Jinan, where a family lives in a one-storey public housing unit. The head of this

family is a middle-aged divorced taxi driver, living with his teenage daughter

and elderly mother. The house is of an old-style and in poor condition. It has

only two small rooms with a small window and little daylight, and it has no

kitchen or toilet. The residents must cook under the houses eaves and walk for

five minutes to the public toilet in another street. The neighbouring houses are

all in similar condition. These rows of houses were built about 50 to 80 years ago

along very narrow lanes. The tenant of this particular house works in a small

taxi company without housing stock, although his monthly income is about 1500

yuan, which is higher than the average monthly income in Jinan (937 yuan).

However, he is not able to buy commodity housing on the housing market. He

hopes that, because his house is located in the inner city, the area will be selected

by the government as a target for urban renewal (for commercial and office

development) in the near future. In that case, he would be resettled by the

government into a new apartment.

The experience of a government official shows how much better are the

housing conditions of employees of some powerful work units. This official is of

middle age and middle-rank and lives with his wife and daughter. In the reform

era, his housing conditions improved rapidly and, within less than 10 years, he

changed his apartment three times. Following each of these changes, his housing

became better and larger. In the early 1990s, he and his family lived in a

two-bedroom apartment in a building in the living quarters of his work unit

very close to his place of work. It was not newly constructed but was modern

and spacious, with a living room, a modern kitchen, a toilet and a balcony, as

well as gas and heating. At that time, this kind of housing was envied by many

people. In the mid-1990s, his work unit developed new living quarters in an

attractive southern suburban area where he was allocated a three-bedroom

apartment. The new apartment was more modern, with hot water, central air

conditioning and cable television. His work unit opened a shuttle bus service

between the new living quarters and the work place. In the late 1990s, his work

unit again started to make investments to further improve living conditions.

New living quarters were again constructed, this time in the southeastern

mountain scenic area, surrounded by a dense forest with plenty of fresh air. The

official moved into a very spacious three-bedroom apartment that was luxuriously decorated with wood oors, modern lighting, kitchen and toilet and three

large balconies. By this time, welfare housing allocation had been discontinued

by the central government and people were required to pay for their new

Chinas Urban Housing Reform

housing. But this official paid only a small amount for his new apartment after

receiving a substantial purchase subsidy from his work unit. He said to the

authors that, compared with other professions, government employees did not

enjoy other benefits because the law strictly regulated wages. So, the only

advantage was to use the governments power to improve employees housing

conditions.

The government admits that its employees enjoy favourable housing conditions

relative to their rates of pay. One state councillor commented in a speech that the

housing conditions of staff employed in government departments and party

institutions is generally better than that of many other employees (Li, 1998). One

study showed that, in 1999, Jinans small and medium-sized enterprises employed

persons occupying apartments with an average living space of 45 sq. metres. In

contrast, the average living space of households with members employed in

government organisations and institutions was 80 sq. metres (Ye, 2000).

The cause of this horizontal inequity is that most urban housing supply

continues to be closely linked with various work units, the work units continue

to construct housing and sell it to their employees, and the privatisation of public

housing was completed only within each individual work unit. One goal of

housing reform is to remove the role of the work unit in housing provision, but

housing privatisation has actually reinforced the work units centrality (Bian

al., 1997). Because there continues to be a strong relationship between employees

and work units in housing supply, the differences in economic conditions among

various work units lead to differences (or horizontal inequity) in housing

consumption among employees. In the reform era, these economic differences

have become larger as a result of the introduction of markets and the withdrawal

of the government from most economic activities, and thus housing inequity has

worsened.

Before the reform era, there were some economic differences, as well as housing

differences, among various work units due to their different sizes, statuses and