Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Croup Recurrente DX y Manejo

Transféré par

natysujananiDescription originale:

Titre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Croup Recurrente DX y Manejo

Transféré par

natysujananiDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

American Journal of OtolaryngologyHead and Neck Medicine and Surgery 28 (2007) 401 407 www.elsevier.

com/locate/amjoto

Recurrent croup presentation, diagnosis, and managementB

Kelvin Kwong, MHSca, Michael Hoa, MDb, James M. Coticchia, MDb,4

b

Wayne State University School of Medicine, Detroit, MI Department of Otolaryngology, Wayne State University, School of Medicine, Detroit, MI Received 10 October 2006

Abstract

Purpose: The lack of clinical insight into recurrent croup often leads to underdiagnosis of an upper airway lesion, and subsequently, inadequate treatment. This study examined the underlying etiology, diagnosis, treatment, and clinical outcome of patients with a history of recurrent croup identified at initial presentation. The aim was to present common diagnostic features and suggest new diagnostic and management recommendations. Materials and methods: A retrospective chart review of 17 children diagnosed with recurrent croup. Demographic, historical, and intraoperative data as noted in clinic charts were collected. Specific collected data included age, sex, chief complaint, presenting symptoms, past medical history, previous medication history, number of emergency room visits and inpatient admissions, tests/ procedures performed and corresponding findings, current treatment given, and posttreatment clinical outcome. Results: Six (35.3%) patients presented initially with a past medical history of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Fourteen (82.3%) patients had positive endoscopic evidence of gastroesophageal reflux. For these 14 patients, 44 laryngopharyngeal reflux lesions were noted, with 32 (72.7%) occurring in the subglottis. All 14 patients demonstrated various degrees of subglottic stenosis ranging from 30% to 70% (Cotton-Myer grade I-II). All 17 patients (100%) demonstrated subglottic stenosis ranging from 15% to 70% airway narrowing. Conclusions: History suggestive of recurrent croup requires close monitoring and expedient direct laryngoscopy/bronchoscopy for diagnosis. Long-term follow-up and antireflux treatment are necessary as well as endoscopic documentation of significant reflux resolution. D 2007 Published by Elsevier Inc.

1. Introduction Recurrent croup is a clinical entity characterized by repeated bouts of croup-like cough that occur in a relapsing and remitting nature that worsen with the onset of upper respiratory tract infection s (URIs), that persist for weeks in a relapsing and remitting nature, and that reflect an exacerbation of a localized airway process. That being said, recurrent croup is a relatively common problem in the pediatric population, with a reported incidence of 6.4% in the infant

B Financial support: Medical research grant from the Department of Otolaryngology, Wayne State University. 4 Corresponding author. Department of Otolaryngology, Wayne State University, 4201 St. Antoine, 5E-UHC, Detroit, MI 48201, USA. Tel.: +1 313 577 0804. E-mail address: jcoticch@med.wayne.edu (J.M. Coticchia).

population followed up for the first 4 years of life [1]. Despite the relatively common nature of this problem, this clinical entity is not well described and is distinct from viral croup or laryngotracheobronchitis in terms of etiology and differential diagnoses. Viral croup, typically preceded by a prodrome of URI, is an acute infection characterized by hoarseness, barking cough, various degrees of inspiratory and/or expiratory stridor, and expiratory rhonchi. These symptoms suggest involvement of the larynx, subglottis, and lower respiratory tract, respectively. Viral croup is the most common cause of upper airway obstruction among children aged between 6 months to 6 years [2]. The incidence of the infection exhibits a seasonal pattern, peaking when parainfluenza type 1, respiratory syncytial virus, and influenza activities are highest. Despite its mild and self-limited nature, this infection occasionally results in severe airway obstruction with a

0196-0709/$ see front matter D 2007 Published by Elsevier Inc. doi:10.1016/j.amjoto.2006.11.013

402

K. Kwong et al. / American Journal of OtolaryngologyHead and Neck Medicine and Surgery 28 (2007) 401 407 Table 2 Endoscopic findings by location Supraglottic Arytenoid edema Interarytenoid edema Granular changes to epiglottis Granular changes to true vocal cords SGS Carinal blunting Mucosal cobblestoning Subglottic shelf Total findings 7 3 1 1 17 8 4 3 32 Glottic Subglottic

reported hospitalization rate ranging from 1.3% to 2.6% [3]. Certain patients have multiple bouts of croup-like symptoms similar to viral croup, except that antecedent or concurrent URI may or may not be associated. Although recurrent croup has been characterized by a constellation of signs and symptoms, it is not a specific diagnosis in itself [4]. Indeed, recurrent croup may represent a manifestation of different underlying airway narrowing processes. Initial studies in the 1970s and 1980s suggested a correlation between recurrent croup and reactive airway disease (RAD) together with other allergic diseases [5-9]. More recent studies have shifted the focus to examining the etiologic association between recurrent croup and upper airway disease processes, such as gastroesophageal reflux (GER), subglottic stenosis (SGS), and other airway narrowing diseases [4,10-12]. The lack of insight into the underlying etiology of recurrent croup often leads to misdiagnosis or underdiagnosis of an upper airway lesion and therefore results in improper or inadequate treatment. The objective of this retrospective study was to review the underlying etiology, diagnosis, treatment, and clinical outcome of patients with a history of recurrent croup identified at initial presentation. 2. Methods After approval from institutional review board was obtained, medical records of 17 infants and children who were referred to the otolaryngology outpatient clinic with a history of recurrent croup between January 2005 and May 2006 were reviewed. Recurrent croup was defined as 2 or more episodes of croup-like symptoms including barking cough, hoarseness, inspiratory stridor, with or without dyspnea, either confirmed medically or reported by parent. In this retrospective case series, the collected data included age, sex, chief complaint, presenting symptoms, past medical history (PMH), previous medication history, number of emergency room visits and inpatient admissions, tests/procedures performed and corresponding findings, current treatment given, and posttreatment clinical outcome.

Table 1 Study findings Average age at first visit Male-to-female ratio % Patients having PMH of RAD % Patients having allergy % Patients having PMH of GERD % Patients with endoscopic evidence of GERD % Patients with endoscopic GER changes having positive endoscopic SGS finding % Patients with endoscopic confirmed dx of SGS % Patients with endoscopically confirmed SGS having confirmed dx of GERD % Patients with sx improvement after starting antireflux medications dx, diagnosis; sx, symptomatic. 3.9 13/17 13/17 5/17 6/17 14/17 (2.5 mo-11 y) (3.25:1) (76.5%) (29.4%) (35.3%) (82.4%)

11

All patients underwent diagnostic direct laryngoscopy/ bronchoscopy (DLB) with rigid equipment as part of a diagnostic workup of recurrent croup. Endoscopic findings of any anatomic abnormalities and pathologic changes in the airway were noted at the time of DLB. Some patients underwent follow-up DLB for clinical reassessment. In addition, 2 patients underwent esophagoscopy with biopsy. All endoscopic evaluations and grading of stenosis were performed by the senior author, who has performed over a thousand DLBs, at a university-affiliated tertiary care hospital. Endoscopic findings, considered to be suggestive of pathogenic GER, included erythema and edema of the arytenoids and posterior glottis, SGS, edematous and erythematous tracheal mucosa, blunting of the tracheal carina, esophageal strictures and signs of esophagitis, and visualized active reflux during esophagoscopy. In patients with SGS, DLB was used to assess the degree of stenosis in percentage obstruction and Cotton-Myer classification (C-M grade) by comparing the individuals endoscope size with the age-appropriate size. Although C-M classification is the most widely used grading system of SGS, we think that the ability to grade smaller changes in SGS with percentage stenosis allows judgements on clinical improvement in a more detailed fashion. Current treatment given for each patient was recorded, and the treatment outcome represented by resolution or improvement of recurrent croup symptoms was followed up prospectively in historical time. To reduce the confounding effect of multiple treatments, the clinical outcome following a single type of treatment was studied. Specifically, cure was defined as patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) who achieved symptom-free status while on antireflux treatment in the absence of other medical treatments (eg, antibiotics). Detailed case descriptions of 2 selected patients were also included in this study. 3. Results The medical records of 17 children with a history of recurrent croup-like symptoms were reviewed. The summary of findings is shown in Table 1. The studied patients consisted of 13 males and 4 females (male-to-female ratio, 3.25:1). The mean age at initial visit was 3.9 years, with a range between 2.5 months and 11 years. Of the 17 studied

15/15 (100.0%) 17/17 (100.0%) 15/17 (88.2%) 13/17 (76.5%)

K. Kwong et al. / American Journal of OtolaryngologyHead and Neck Medicine and Surgery 28 (2007) 401 407

403

Fig. 1. Pathogenesis of viral croup versus recurrent croup.

Fig. 3. Posttreatment DLB findings.

patients, 13 (76.5%) had a PMH of RAD. Among them, 5 (29.4%) had a prior history of allergy or atopic disease. Of the 17 patients, 6 (35.3%) presented initially with a PMH of GERD. All patients underwent endoscopic evaluation. Of 17 patients, 14 (82.3%) had positive endoscopic evidence of GER. All 14 patients demonstrated various degrees of SGS ranging from 30% to 70% (C-M grade I-II). Among these patients, 13 had GER-related laryngopharyng-

eal changes seen in DLB, and 1 had an esophagogastroduodenoscopy done by an outside physician demonstrating reflux esophagitis. The remaining 3 patients, despite the absence of endoscopic evidence of GER, were found to have SGS between 15% and 70% (C-M grade I-II), meaning 100% of our studied patients with recurrent croup demonstrated a localized narrowing in the airway. No elliptically shaped cricoid cartilage was noted in any these patients. Of the endoscopic findings of GER-related changes, 32 (72.7%) of 44 lesions were noted at the level of the

Fig. 2. Pretreatment DLB findings.

Fig. 4. Diagnostic and management algorithm.

404

K. Kwong et al. / American Journal of OtolaryngologyHead and Neck Medicine and Surgery 28 (2007) 401 407

subglottis in the form of either mucosal cobblestoning, SGS, a subglottic shelf, or carinal blunting (Table 2). All 17 patients were started on antireflux medications. Thirteen (76.5%) patients demonstrated clinical improvement as noted by shortened duration of croup-like episodes, decreased symptom severity, or the patient becoming asymptomatic. These 13 patients all had positive endoscopic evidence of laryngopharyngeal reflux-related changes. 3.1. Case 1 TM was a 3-month-old male who presented with a 2-month history of recurrent croup-like cough and inspiratory stridor. The patients mother noted that episodes of intermittent croup-like cough would last for 1 to 2 weeks at a time and would be exacerbated by upper respiratory tract infections. The patient had no known drug allergies and had no significant PMH. On examination, the patient was noted to have croup-like cough with inspiratory stridor. In addition, costal and subcostal retractions were noted. Remainder of physical examination was normal. Endoscopic findings at the first DLB included 50% SGS (C-M grade I), arytenoid and interarytenoid edema, carinal blunting, and mucosal cobblestoning. In the subsequent DLB after antireflux treatment, SGS was reduced to 15% to 20% (C-M grade I) with minimal GER-related mucosal changes. 3.2. Case 2 JB was a 7-year-old boy who presented with a history of a persistently intermittent croup-like cough that worsened in the presence of upper respiratory tract infections. Parents related frequent upper respiratory tract infections distributed throughout fall, winter, and spring, with 8 of 10 episodes associated with a croup-like paroxysmal cough. The patient noted the presence of an intermittent cough at least 1 to 2 times per day. Multiple visits to the emergency department averaging 1 to 2 times per month along with multiple steroid treatments were noted by the patients mother. The patient had no known drug allergies. Past medical history was notable for IgG immunodeficiency. Physical examination of the patient was essentially unremarkable. Endoscopic findings at the initial DLB included 40% SGS (C-M grade II), subglottic shelf, and mild arytenoid erythema and edema. Repeat examination of the patient revealed an improvement to 15% SGS (C-M grade I) on DLB in addition to symptomatic improvement as noted on clinical examination.

4. Discussion 4.1. Characterization of recurrent croup Despite being a relatively common condition in infant and pediatric populations, recurrent croup has not been well described in previous literature in terms of its epidemiology, natural history, and etiology. Recurrent croup is commonly defined as recurring episodes (more than 2) of croup-like symptoms, such as hoarseness, inspiratory stridor, and

barking cough. The age at first visit of our studied population ranged from 2.5 months to 11 years, with an average of 3.9 years. There was a strong male preponderance in our patients, which was also observed in other studies [1,5,13]. Besides the croup-like symptoms, our patients also presented with other symptoms including nasal congestion, rhinorrhea, apneic pauses, and/or intercostal retractions. Although the data suggest that recurrent croup episodes were commonly preceded by a URI challenge, some patients experienced recurrent episodes in absence of a URI prodrome or symptoms. Typically, a recurrent croup episode could last from several days to weeks. There was a seasonal variation in these patients coinciding with the peak of respiratory tract infection in the fall and winter months. Our patients were referred by primary care physicians, general pediatricians, and pediatric subspecialists for a history of bcroupy cough,Q bstridor,Q or bairway evaluation.Q Most of our patients (76.5%) had a PMH of RAD. Nevertheless, none of the patients presented with wheezing, rhonchi, or other symptoms or signs of lower respiratory tract involvement. Atopic symptoms were only found in 5 (29.4%) of the 17 patients. Many of them were treated with maximized doses of RAD medications in an attempt to control the aforementioned symptoms. Despite aggressive medical therapy for RAD, there was no documented improvement in clinical symptoms. Although having not been well defined, spasmodic croup is often referred as a type of afebrile croup with a sudden onset, almost always at night or during sleep, significantly associated with inspiratory stridor and respiratory distress, and usually responds well to humidification [12]. The proposed pathophysiologic mechanism is spasm of the larynx related to allergy, psychological causes, URI, and/or GERD. The disease can be recurrent and usually subsides spontaneously [12]. Sharing some common characteristics with recurrent croup, spasmodic croup may indeed represent a clinical entity that fits into the pathophysiologic model proposed later in this section. The comparison between recurrent croup and viral croup reveals that the 2 conditions indeed represent 2 different clinical entities. First, the recurring nature distinguishes recurrent croup from viral croup, which tends not to recur within the same year unless the patient is immunocompromised or infected by a different strain of pathogen. Second, viral croup first starts as an acute infection of the nasal and pharyngeal mucosa and then extends downward along the respiratory tract to the larynx, subglottic region, trachea, and even bronchi in severe cases. The involvement of the lower respiratory tract, especially the intrathoracic segment, manifests as expiratory stridor, rhonchi, or wheezing. In contrast, recurrent croup involves mainly the upper airway and spares the lower respiratory tract in most cases, as suggested by the lack of rhonchi and wheezing in its clinical manifestation. The 2 differences between recurrent croup and viral croup suggest that the pathogenesis of the 2 conditions is

K. Kwong et al. / American Journal of OtolaryngologyHead and Neck Medicine and Surgery 28 (2007) 401 407

405

fundamentally distinct. The recurrent nature and the lack of lower respiratory tract involvement (ie, less severe infection) indicate that recurrent croup has a lower threshold to clinically significant airway obstruction. This is reinforced by the fact that a recurrent croup episode is not always preceded by URI challenge or prodrome, meaning that minimal insult or irritation to the subglottic mucosa can make patients with recurrent croup become symptomatic. All of these observations point toward a plausible explanation that all patients with recurrent croup have a baseline airway narrowing caused by various etiologies. When challenged with URI or other airway irritating processes, the additional edematous mucosal changes further constrict the already narrowed airway, therefore causing clinically significant obstruction (Fig. 1). To adequately control and treat recurrent croup, it is essential to find the true underlying cause of the existing baseline airway narrowing in the patients. 4.2. Etiologies of the baseline airway narrowing 4.2.1. Recurrent airway disease as an etiology versus comorbidity of recurrent croup The association between recurrent croup and RAD was frequently reported in various earlier studies [5-7,14-16]. In these studies, the reported percentages of recurrent croup patients with RAD range from 40.4% to 82%, which is in good agreement with our finding of 76.5%. Despite the significant association, prior studies have been unable to conclusively demonstrate a cause-and-effect relationship. Neither temporality nor positive dose-response relationships between RAD and recurrent croup have been demonstrated. In addition, no plausible biological mechanism can fully explain the proposed hypothesis. Finally, inconsistency in the association of recurrent croup and atopic diseases further undermines the proposed causal link between RAD and recurrent croup [7-9]. Certain findings in our study argue against the causative role of RAD in reproducing recurrent croup episodes. First, most patients remained symptomatic and continued to have recurrent croup episodes despite medically maximized therapy for RAD. Furthermore, none of the patients presented with wheezing, rhonchi, or other symptoms/signs suggestive of lower respiratory tract involvement. Finally, a high percentage of the patients (82.4%) demonstrated endoscopic findings of laryngopharyngeal reflux. Together with its documented association with RAD, GERD is likely an inducing or exacerbating factor for asthmatic symptoms, hence plausibly explaining the high incidence of RAD among recurrent croup patients. 4.2.2. Gastroesophageal reflux disease as a common finding in our studied patients In this study, GER changes in the laryngotracheal portion of the airway were very common endoscopic findings, observed in 82.3% of our recurrent croup patients. Interest-

ingly, in our patients with recurrent croup, GERD may have been largely undiagnosed, as suggested by the observation that only 35% of our studied patients had a past diagnosis of GERD. Several other studies document the prevalence of GERD in patients with recurrent croup. In an inpatient study of children admitted for recurrent croup (2 or more episodes), GERD, which was documented by scintiscan, esophagoscopy, pH probe, and barium swallow study, was found in 15 (47%) of 32 subjects [13]. Among 16 children with 3 or more episodes, 10 (65%) had a diagnosis of GERD. In an esophageal biopsy study, 12 (75%) of 16 children with a recurrent croup history had positive esophageal biopsy results [12]. Using a double pH probe, Contencin and Narcy [16] observed pharyngeal and esophageal reflux in 8 (100%) of 8 children with recurrent croup. In addition to the high prevalence of GERD, the outcomes of antireflux treatment in our patients give us further insight into the relationship between GERD and recurrent croup. Among 14 patients with positive endoscopic finding of GER, 12 of them showed either improvement or resolution of recurrent croup symptoms after starting the antireflux medications. Gastroesophageal reflux diseaserelated mucosal changes were also improved in the patients who had posttreatment follow-up endoscopic evaluation (Fig. 2 vs 3). This observation provides suggestive evidence that GERD is either a cause or a significant contributing factor to recurrent episodes of croup. 4.2.3. Subglottic stenosis Another striking finding in our study is that 17 (100%) of the 17 studied patients had positive endoscopic findings of various degree of SGS ranging from 30% to 70% (C-M grade I-II). Compared to other recurrent croup studies, SGS was much more common in our studied patients. Waki et al [13] noted that 8 (25%) of their 32 patients with recurrent croup demonstrated anatomical airway abnormalities including SGS and laryngomalacia. Farmer and Wohl [4] reported that 24 (45%) of their 53 pediatric patients with recurrent intermittent airway obstruction had airway narrowing such as acquired laryngotracheal stenosis, congenital cricotracheal abnormality, and subglottic hemangioma. In particular, our findings support the hypothesized pathophysiologic mechanism that all recurrent croup patients have a certain degree of baseline subglottic narrowing, which lowers their threshold to clinically significant airway obstruction and makes the patient more prone to recurrent croup episodes. Subglottic stenosis can either be congenital or acquired. The former is less common and is usually seen in patients born with small elliptically shaped cricoid cartilage [17]. The causes of acquired SGS include traumatic intubation, infection [18-33], and GERD [21-23]. Various animal models have been used to demonstrate these etiologic causes of SGS. Using a canine model, Klainer et al [24] found complete ciliary denudation after 2 hours of intubation with a minimally occlusive low-pressure cuff.

406

K. Kwong et al. / American Journal of OtolaryngologyHead and Neck Medicine and Surgery 28 (2007) 401 407

Squire et al [19] demonstrated that rabbits with intratracheal bacterial inoculation using Staphylococcus aureus had narrower stenoses than those that remained noninfected. Gaynor [21] observed severe mucosal ulceration and necrosis in rabbit tracheas irrigated with synthetic gastric juice of pH 1.4 and pepsin, as compared with controls with saline, which demonstrated no significant mucosal changes. Koufman [25] reported a similar finding as well as healing delay of subglottic submucosal injuries in a canine model. Although the relative contribution of various etiologies to SGS in patients with recurrent croup remains unclear, several findings in our study may provide further insight into this particular issue. In this study, positive endoscopic findings of laryngopharyngeal manifestation of GER were found in 14 (82.4%) of 17 patients with endoscopically confirmed SGS. This prevalence of laryngopharyngeal GER finding among SGS patients was in good agreement with previous studies. In a study of 19 patients with SGS undergoing 24-hour ambulatory pH probe testing with 3- or 4-port probes, Maronian et al [26] reported that a pH of less than 4 was recorded at the level of larynx in 12 (86%) of the 14 tested patients. Yellon et al [27] also demonstrated in a series of 36 children with SGS who underwent laryngotracheal reconstruction, that 21 (81%) of the 26 tested patients had at least 1 positive test for GERD. Although the prevalence of pathologic GERD is estimated to be only 20% and 8% in infants and children after 12 months of age, respectively, the elevated GERD prevalence in patients with SGS supports the hypothesis that GERD may play an important role in the etiology of SGS [28]. The outcome of antireflux treatment could provide further evidence on the association between GERD and SGS. Four of our studied patients underwent a second DLB follow-up after antireflux treatment. Of the 4 patients, 4 (100%) demonstrated an improvement or reduction in stenosis by a magnitude ranging from 10% to 30%. Pretreatment/Posttreatment endoscopic findings of a patient demonstrating 30% stenosis reduction are shown in Fig. 2 (70% stenosis) and Fig. 3 (40% stenosis), respectively. Similarly, Jindal et al [29] reported that 7 of 7 women with idiopathic SGS who initially failed to respond to all conservative measures and radical surgical intervention required GERD medical treatment for symptom resolution. In her study of 25 pediatric SGS patients, Halstead [23] reported that the failure rate of endoscopic repair dropped dramatically after aggressive preoperative GER treatment when compared with the historical controls and additionally noted that 35% avoided surgical intervention. Gray et al [30] also described the improvement in laryngotracheoplasty outcomes with aggressive antireflux treatment. 4.3. Management of recurrent croup We are proposing a diagnostic and management algorithm for patients presenting with recurrent croup-like symptoms

(Fig. 4). First, a thorough history and physical should be obtained to establish the recurrent croup status. The relevant symptoms include hoarseness, barking cough, and various degrees of inspiratory and/or expiratory stridor that recur more than 2 times. Second, presence of URI symptoms, such as fever, nasal discharge, congestion, and sore throat, should be assessed. If the patient has persistent URI symptoms more than a few days, antibiotic treatment is administered to treat the superimposed bacterial infection. The next step is assessment of potential baseline airway narrowing using DLB, which provides direct visualization of any potential narrowing and bsilentQ laryngopharyngeal manifestations of GER. Direct laryngoscopy/bronchoscopy should be performed when the patient is free of respiratory tract infections, which may cause airway edema that hinders the ability to detect baseline airway changes. If DLB is positive for SGS and/or laryngopharyngeal reflux findings such as erythema and edema of arytenoids and posterior glottis, edematous and erythematous tracheal mucosa, and blunting of the carina, antireflux medication together with dietary and lifestyle modifications should be started immediately to control the GER. Initial conservative management includes avoidance of food containing high amounts of fat, chocolate, peppermint, caffeine, and citrus ingredients; frequent small meals taken well before bedtime; elevation of the head of the bed; and weight loss for obese children. Initial pharmacologic treatment includes H2 blockers, such as ranitidine or cimetidine, in combination with prokinetic agents (eg, metoclopramide). We routinely prefer the use of ranitidine over cimetidine because of its higher potency, longer duration, and less frequency of adverse effects and drug interaction [31,32]. Cases refractory to the above initial pharmacologic treatment may require a proton-pump inhibitor (PPI), such as omeprazole or lansoprazole. Proton-pump inhibitors are generally safe and well-tolerated medications in both adults and children [33,34]. Given the limited data and evidence, multicenter studies are needed to investigate the safety profile of the long-term use of PPIs, particularly in pediatric populations. Although 24-hour pH probe monitoring remains the gold standard of diagnosing GERD, endoscopic studies have been shown to demonstrate good correlation with histological studies. In an esophageal biopsy study done by Yellon et al [12], if an erythematous or edematous posterior glottis was noted, the esophageal was positive 83% and 81% of the time, respectively. Patients should then be followed up a month after starting the antireflux medications. In patients with SGS higher than 50% to 60%, DLB should be done in 3 months to follow the progression of the condition. In cases refractory to antireflux treatment, esophagogastroduodenoscopy is recommended. Referral to gastrointestinal subspecialty and pediatric surgery for potential surgical intervention for GERD may be necessary. Patients with negative DLB findings should be observed closely for any future recurrent episodes and condition progression.

K. Kwong et al. / American Journal of OtolaryngologyHead and Neck Medicine and Surgery 28 (2007) 401 407

407

5. Conclusion Being a relatively common pediatric condition, recurrent croup should be considered, diagnosed, and managed as a separate clinical entity from viral laryngotracheobronchitis. The 2 conditions are likely to have different pathophysiological processes as suggested by the proposed models; patients with recurrent croup often have an underlying localized upper airway narrowing and a much lower threshold for airway narrowing that predisposes patients to recurrent bouts of croup-like symptoms. Our data suggest that baseline narrowing is mainly subglottic and that lowering the threshold can lead to significant clinical airway obstruction, especially when patients are challenged by URI or airway mucosal irritation such as GER. In our study, laryngopharyngeal manifestation of GER is a very common finding in recurrent croup patients. Because of the silent nature of laryngopharyngeal GER, early diagnosis of GERD is often missed. Direct laryngoscopy/bronchoscopy is recommended as the first step in the evaluation of recurrent croup to detect any potential airway narrowing and/or evidence of laryngopharyngeal GER, which is also closely associated with SGS. Appropriate antireflux medications should be started in cases with positive GERD findings on DLB to reduce the progression of the airway narrowing or stenosis. Our study shows clinical improvement in most of the studied patients with the treatment of GERD. Future prospective studies should be done to delineate a possible causal relationship between GERD and recurrent croup. References

[1] Hide DW, Guyer BM. Recurrent croup. Arch Dis Child 1985; 60(6):585 - 6. [2] Leung AK, Kellner JD, Johnson DW. Viral croup: a current perspective. J Pediatr Health Care 2004;18(6):297 - 301. [3] Peltola V, Heikkinen T, Ruuskanen O. Clinical courses of croup caused by influenza and parainfluenza viruses. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2002;21(1):76 - 8. [4] Farmer TL, Wohl DL. Diagnosis of recurrent intermittent airway obstruction (brecurrent croupQ) in children. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 2001;110(7 Pt 1):600 - 5. [5] Zach M, Erben A, Olinsky A. Croup, recurrent group, allergy, and airways hyper-reactivity. Arch Dis Child 1981;56(5):336 - 41. [6] Zach MS, Schnall RP, Landau LI. Upper and lower airway hyperreactivity in recurrent croup. Am Rev Respir Dis 1980;121(6):979 - 83. [7] Konig P. The relationship between croup and asthma. Ann Allergy 1978;41(4):227 - 31. [8] Van Bever HP, Wieringa MH, Weyler JJ, et al. Croup and recurrent croup: their association with asthma and allergy. An epidemiological study on 58-year-old children. Eur J Pediatr 1999;158(3):253 - 7. [9] Nicolai T, Mutius EV. Risk of asthma in children with a history of croup. Acta Paediatr 1996;85(11):1295 - 9. [10] Burton DM, Pransky SM, Katz RM, et al. Pediatric airway manifestations of gastroesophageal reflux. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 1992;101(9):742 - 9. [11] Halstead LA. Role of gastroesophageal reflux in pediatric upper airway disorders. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1999;120(2):208 - 14.

[12] Yellon RF, Coticchia J, Dixit S. Esophageal biopsy for the diagnosis of gastroesophageal reflux-associated otolaryngologic problems in children. Am J Med 2000;108(Suppl 4a):131S - 8S. [13] Waki EY, Madgy DN, Belenky WM, et al. The incidence of gastroesophageal reflux in recurrent croup. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 1995;32(3):223 - 32. [14] Litmanovitch M, Kivity S, Soferman R, et al. Relationship between recurrent croup and airway hyperreactivity. Ann Allergy 1990;65(3): 239 - 41. [15] Cohen B, Dunt D. Recurrent and non-recurrent croup: an epidemiological study. Aust Paediatr J 1988;24(6):339 - 42. [16] Contencin P, Narcy P. Gastropharyngeal reflux in infants and children. A pharyngeal pH monitoring study. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1992;118(10):1028 - 30. [17] Bath AP, Panarese A, Thevasagayam M, et al. Paediatric subglottic stenosis. Clin Otolaryngol Allied Sci 1999;24(2):117 - 21. [18] Sasaki CT, Horiuchi M, Koss N. Tracheostomy-related subglottic stenosis: bacteriologic pathogenesis. Laryngoscope 1979;89(6 Pt 1): 857 - 65. [19] Squire R, Brodsky L, Rossman J. The role of infection in the pathogenesis of acquired tracheal stenosis. Laryngoscope 1990; 100(7):765 - 70. [20] Suzumura H, Nitta A, Tanaka G, et al. Role of infection in the development of acquired subglottic stenosis in neonates with prolonged intubation. Pediatr Int 2000;42(5):508 - 13. [21] Gaynor EB. Gastroesophageal reflux as an etiologic factor in laryngeal complications of intubation. Laryngoscope 1988;98(9): 972 - 9. [22] Walner DL, Stern Y, Gerber ME, et al. Gastroesophageal reflux in patients with subglottic stenosis. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1998;124(5):551 - 5. [23] Halstead LA. Gastroesophageal reflux: a critical factor in pediatric subglottic stenosis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1999; 120(5):683 - 8. [24] Klainer AS, Turndorf H, Wu WH, et al. Surface alterations due to endotracheal intubation. Am J Med 1975;58(5):674 - 83. [25] Koufman JA. The otolaryngologic manifestations of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD): a clinical investigation of 225 patients using ambulatory 24-hour pH monitoring and an experimental investigation of the role of acid and pepsin in the development of laryngeal injury. Laryngoscope 1991;101(4 Pt 2 Suppl 53):1 - 78. [26] Maronian NC, Azadeh H, Waugh P, et al. Association of laryngopharyngeal reflux disease and subglottic stenosis. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 2001;110(7 Pt 1):606 - 12. [27] Yellon RF, Parameswaran M, Brandom BW. Decreasing morbidity following laryngotracheal reconstruction in children. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 1997;41(2):145 - 54. [28] Yellon RF, Cotton RT. Gastroesophageal reflux disease. In: Bluestone CD, Stool SE, Alper CM, et al, editors. Pediatric otolaryngology. 4th ed. Philadelphia7 WB Saunders; 2003. p. 1301 - 11. [29] Jindal JR, Milbrath MM, Shaker R, et al. Gastroesophageal reflux disease as a likely cause of bidiopathicQ subglottic stenosis. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 1994;103(3):186 - 91. [30] Gray S, Miller R, Meyer CM. Adjunctive measures for successful laryngotracheal reconstruction. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 1987; (96):509 - 13. [31] Kelly DA. Do H2 receptor antagonists have a therapeutic role in childhood? J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 1994;19(3):270 - 6. [32] Dimand RJ. Use of H2-receptor antagonists in children. DICP 1990;24(11 Suppl):S42-6. [33] Marchetti F, Gerarduzzi T, Ventura A. Proton pump inhibitors in children: a review. Dig Liver Dis 2003;35(10):738 - 46. [34] Gibbons TE, Gold BD. The use of proton pump inhibitors in children: a comprehensive review. Paediatr Drugs 2003;5(1):25 - 40.

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (120)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (588)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (266)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (399)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5794)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2259)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1090)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (895)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)

- Risk Assessment of Heavy LiftingDocument5 pagesRisk Assessment of Heavy Lifting채종언100% (3)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- Evidence-Based Practice in Pediatric Physical Therapy by BarryDocument14 pagesEvidence-Based Practice in Pediatric Physical Therapy by BarryFe TusPas encore d'évaluation

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (73)

- FWA CMS Training (4346) PDFDocument13 pagesFWA CMS Training (4346) PDFinfo3497Pas encore d'évaluation

- Personality Disorders PDFDocument35 pagesPersonality Disorders PDFABHINAVPas encore d'évaluation

- ACOG - External Cephalic Version PDFDocument10 pagesACOG - External Cephalic Version PDFPat CabanitPas encore d'évaluation

- The Impact of Longitudinal Studies On Understanding Development From Young Adulthood To Old AgeDocument11 pagesThe Impact of Longitudinal Studies On Understanding Development From Young Adulthood To Old AgeLana PeharPas encore d'évaluation

- HLTWHS002 AE KN 1of3 Katarina JosipovicDocument20 pagesHLTWHS002 AE KN 1of3 Katarina Josipovicwriter top100% (1)

- Week 2 SolutionsDocument4 pagesWeek 2 Solutionsannavarapuanand100% (2)

- Different Committees in The HospitalDocument8 pagesDifferent Committees in The HospitalShehnaz SheikhPas encore d'évaluation

- Letters of Intent (Cover Letters)Document6 pagesLetters of Intent (Cover Letters)anca_ramona_s0% (1)

- NCP Impaired Gas Exhange Related To Alveolar Wall Destruction EMPHYSEMADocument5 pagesNCP Impaired Gas Exhange Related To Alveolar Wall Destruction EMPHYSEMAMa. Elaine Carla Tating50% (2)

- 7 Legal Dimensions of Nursing Chapter ReviewDocument2 pages7 Legal Dimensions of Nursing Chapter ReviewAmy AnonymousPas encore d'évaluation

- FA CPR Workbook 0001Document56 pagesFA CPR Workbook 0001Shawn KimballPas encore d'évaluation

- Providing Information Raising Awareness: June 2015Document17 pagesProviding Information Raising Awareness: June 2015Aymanahmad AymanPas encore d'évaluation

- Tipos de Diabetes - Diabetes MonogenicaDocument27 pagesTipos de Diabetes - Diabetes MonogenicaSara AmorimPas encore d'évaluation

- Domestic Violence Cycle of Violence Types of Families-2Document22 pagesDomestic Violence Cycle of Violence Types of Families-2api-340420872Pas encore d'évaluation

- Safety Pocket Guide Web 061808Document534 pagesSafety Pocket Guide Web 061808hombre911100% (1)

- Ecological Analysis of The Prevalence of PulmonaryDocument10 pagesEcological Analysis of The Prevalence of PulmonaryLazy SlothPas encore d'évaluation

- 20 MG 100 ML ConivaptanDocument18 pages20 MG 100 ML Conivaptanahmedradwan2005Pas encore d'évaluation

- MDMA-assisted Therapy Significantly Reduces Eating Disorder Symptoms in A Randomized Placebo-Controlled Trial of Adults With Severe PTSDDocument8 pagesMDMA-assisted Therapy Significantly Reduces Eating Disorder Symptoms in A Randomized Placebo-Controlled Trial of Adults With Severe PTSDKayla GreenstienPas encore d'évaluation

- Alternatives To Hydrazine MHI PaperDocument5 pagesAlternatives To Hydrazine MHI PaperjycortesPas encore d'évaluation

- Position Paper de l'UEFA Sur L'interdiction Du Gazon Synthétique Par l'ECHA 19 Juillet 2019Document8 pagesPosition Paper de l'UEFA Sur L'interdiction Du Gazon Synthétique Par l'ECHA 19 Juillet 2019LeMonde.frPas encore d'évaluation

- Asthma Case StudyDocument39 pagesAsthma Case StudyDimitris TasiouPas encore d'évaluation

- Lab Report 15438869 20231127064225Document1 pageLab Report 15438869 20231127064225carilloabhe21Pas encore d'évaluation

- CephalosporinsDocument20 pagesCephalosporinsBianca Andrea RagazaPas encore d'évaluation

- DENGUEDocument17 pagesDENGUEPramod LamichhanePas encore d'évaluation

- Prescribing For Transgender Patients ELHEDocument4 pagesPrescribing For Transgender Patients ELHEGe YgayPas encore d'évaluation

- Lista Medicamente OTC Conform Nomenclator ANM 17 Feb2020Document184 pagesLista Medicamente OTC Conform Nomenclator ANM 17 Feb2020Andreea PasolPas encore d'évaluation

- Prilosec (Omeprazole) MoreDocument3 pagesPrilosec (Omeprazole) MoreLuis Arturo Andrade CoronadoPas encore d'évaluation

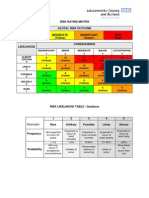

- Example of A NHS Risk Rating MatrixDocument2 pagesExample of A NHS Risk Rating MatrixRochady SetiantoPas encore d'évaluation