Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

People Vs Olvis (Case Digest) - Elro Mar L. Tabiliran

Transféré par

Ǝlro Mar TabiliranTitre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

People Vs Olvis (Case Digest) - Elro Mar L. Tabiliran

Transféré par

Ǝlro Mar TabiliranDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

PEOPLE OF THE PHILIPPINES vs. ANACLETO Q.

OLVIS, Acquitted, ROMULO VILLAROJO, LEONARDO CADEMAS and DOMINADOR SORELA,

G.R. No. 71092 September 30, 1987 Forced re-enactments, like uncounselled and coerced confessions come within the ban against self- incrimination. Evidence based on such re-enactment is a violation of the Constitution and hence, incompetent evidence. Here, accused is not merely required to exhibit some physical characteristics; by and large, he is likewise made to admit criminal responsibility against his will. It is a police procedure just as condemnable as an uncounselled confession. The lack of counsel makes statement in contemplation of law, 'involuntary' even if it were otherwise voluntary. FACTS: On September 9, 1975, authorities from the Integrated National Police station of Barrio Polanco, in Zamboanga del Norte, received a report that a certain Deosdedit Bagon is missing. Bagon had been in fact missing since two days before. He was last seen by his wife in the afternoon of September 7, 1975, on his way home to Sitio Sebaca where they resided. A search party was conducted by the authorities to mount an inquiry. As a matter of police procedure, the team headed off to Sitio Sebaca to question possible witnesses. There, they chanced upon an unnamed volunteer, who informed them that Deosdedit Bagon was last seen together with Dominador Sorela, one of the accused herein. The authorities then thereafter picked up Sorela for interrogation. Sorela bore several scratches on his face, neck and arms when the police found him. According to him, he sustained those wounds while clearing his ricefield. Apparently unconvinced, the police had Sorela take them to the ricefield where

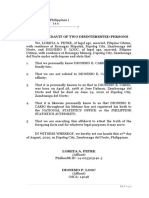

he sustained his injuries. But half way there, Sorela illegally broke down, and, in what would apparently crack the case for the police, admitted having participated in the killing of the missing Bagon. Sorela allegedly confessed having been with Deosdedit Bagon, a friend of his, in the evening of September 7, 1976 in Sitio Sebaca. They were met by Romulo Villarojo and Leonardo Cademas, Sorela's coaccused herein and likewise friends of the deceased, who led them to a secluded place in the ricefields. According to their confessions Villarojo attacked Bagon with a bolo, hacking him at several parts of the body until he, Bagon, was dead. Moments later, Sorela fled, running into thick cogon grasses where he suffered facial and bodily scratches. The police soon picked up Villarojo and Cademas. Together with Sorela, they were turned over to the custody of Captain Encabo the Polanco Station Commander. The police thereafter made the three re-enact the crime. Sorela was directed to lead them to the grounds where Discredit Bagon was supposed to have been buried. But it was Villarojo who escorted them to a watery spot somewhere in the ricefields, where the sack-covered, decomposing cadaver of Bagon lay in a shallow grave. The necropsy report prepared by the provincial health officer disclosed that the deceased suffered twelve stab and hack wounds, six of which were determined to be fatal. In the re-enactment, the suspects, the three accused herein, demonstrated how the victim was boloed to death. A photograph, shows the appellant Villarojo in the posture of raising a bolo as if to strike another, while Solero and Cademas look on. Another photograph, portrays Villarojo in the act of concealing the murder weapon behind a banana tree, apparently after having done the victim in. Initial findings of investigators disclosed that the threesome of Solero, Villarojo, and Cademas executed Discredit Bagon on orders of Anacleto Olvis, then Polanco municipal mayor, for a reward of P3,000.00 each. While in custody, the three executed five separate written confessions each. The first confessions were taken on September 9, 1975 in the local Philippine Constabulary headquarters. The second were made before the Polanco police. On September 18, 1975, the three accused reiterated the same confessions before

the National Bureau of Investigation Dipolog City sub-office. On September 21, 1975 and September 25, 1975, they executed two confessions more, again before the Philippine Constabulary and the police of Polanco. In their confessions of September 9, 1975, September 14, 1975, September 21, 1975, and September 25, 1975, the said accused again pointed to the then accused Anacleto Olvis as principal by inducement, who allegedly promised them a reward of P3,000.00 each. In their confessions of September 18, 1975, sworn before agents of the National Bureau of Investigation, however, they categorically denied Olvis' involvement in the knowing. We note that the three were transported to the Dipolog City NBI sub-office following a request on September 10, 1975 by Mrs. Diolinda O. Adaro daughter of Olvis, and upon complaint by her of harassment against her father by his supposed political enemies. The court a quo rendered separate verdicts on the three accused on the one hand, and Anacleto Olvis on the other. However Olvis was acquitted, while the three were all sentenced to die for the crime of murder. In acquitting Olvis, the trial court rejected the three accused's earlier confessions pointing to him as the mastermind, and denied the admissibility thereof insofar as far as he was concerned. It rejected claims of witnesses that the three accusedappellants would carry out Olvis' alleged order to kill Bagon upon an offer of a reward when in fact no money changed hands. With the acquittal of Olvis, however the remaining accused-appellants subsequently repudiated their alleged confessions in open court despite prior confessions, and now were alleging that there were threats by the Polanco investigators of physical harm if they refused to "cooperate" in the solution of the case. They likewise alleged that they were instructed by the Polanco police investigators to implicate Anacieto Olvis in the case. They insisted on their innocence. The accused Romulo Villarojo averred, specifically, that it was the deceased who had sought to kill him, for which he acted in self-defense. For the defense, the accused Romulo Villarojo admitted hacking the victim to death with a bolo. He

stressed, however, that he did so in self- defense. He completely absolved his coaccused Dominador Sorela and Leonardo Cademas from any liability. The murder of Deosdedit Bagon was witnessed by no other person. The police of Polanco had but the three accused-appellants' statements to support its claiming.

Issues: (1.) (2.) Ruling: (1.) No. The three accused-appellants' extrajudicial confessions are inadmissible in evidence. Prior to any questioning, the person must be warned that he has a right to remain silent, that any statement he does make may be used as evidence against him, and that he has a right to the presence of an attorney, either retained or appointed At the outset, if a person in custody is to be subjected to interrogation, he must first be informed in clear and unequivocal terms that he has the right to remain silent. For those unaware of the privilege, the warning is needed simply to make them aware of the threshold requirement for an intelligent decision as to its exercise. More important, such a warning is an absolute pre-requisite in overcoming the inherent pressures of the interrogation atmosphere. The confessions in the case at bar suffer from a Constitutional infirmity In their supposed statements dated September 9, 14, and 21, 1975, the accused-appellants were not assisted by counsel when they "waived" their rights to counsel. The lack of counsel makes statement in contemplation of law, 'involuntary' even if it were otherwise voluntary, technically. Whether these statements, as any of the extrajudicial confession can stand up in court. Whether Villarojos claim of self-defense tenable?

Forced re-enactments, like uncounselled and coerced confessions come within the ban against self- incrimination. The 1973 Constitution, the Charter prevailing at the time of the proceedings below, says: No person shall be compelled to be a witness against himself. This should be distinguished, parenthetically, from mechanical acts the accused is made to execute not meant to unearth undisclosed facts but to ascertain physical attributes determinable by simple observation. This includes requiring the accused to submit to a test to extract virus from his body, or compelling him to expectorate morphine from his mouth, or making her submit to a pregnancy test, or a foot printing test or requiring him to take part in a police lineup in certain cases." In each case, the accused does not speak his guilt. It is not a prerequisite therefore that he be provided with the guiding hand of counsel. But a forced re-enactment is quite another thing. Here, the accused is not merely required to exhibit some physical characteristics; by and large, he is made to admit criminal responsibility against his will. It is a police procedure just as condemnable as an uncounselled confession. It should be furthermore observed that the three accused-appellants were in police custody when they took part in the re-enactment in question. It is under such circumstances that the Constitution holds a strict application. Any statement he might have made thereafter is therefore subject to the Constitutional guaranty. In such a case, he should have been provided with counsel. (2.) The records will disclose that the deceased suffered twelve assorted wounds caused by a sharp instrument. The assault severed his right hand and left his head almost separated from his body. This indicates a serious intent to kill, rather than self-defense. In finding that Villarojo did take the life of the victim, superior strength or nocturnity is unfound. In the absence of any other proof, the severity and number of wounds sustained by the deceased are not, by themselves, sufficient proof to warrant the appreciation of the generic aggravating circumstance of abuse of superior strength. Hence, Villarojo

should be liable for plain homicide, and accused-appellants Leonardo Cademas and Dominador Sorela are acquitted on the ground of reasonable doubt.

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- People V OlvisDocument2 pagesPeople V OlvisGabe Bedana100% (1)

- Arts. 1451-1452 (Implied Trust)Document8 pagesArts. 1451-1452 (Implied Trust)Kai TehPas encore d'évaluation

- People V Peralto To People V Chua Ho SanDocument18 pagesPeople V Peralto To People V Chua Ho SanGladys Bustria OrlinoPas encore d'évaluation

- Unclos eDocument2 pagesUnclos eBeatrizNicoleAradaPas encore d'évaluation

- Villaflor Vs SummersDocument2 pagesVillaflor Vs SummersinvictusincPas encore d'évaluation

- Feeder International Line LTD. Vs CA Ruling on Seizure of Cargo for Customs ViolationDocument2 pagesFeeder International Line LTD. Vs CA Ruling on Seizure of Cargo for Customs ViolationBryan Jay NuiquePas encore d'évaluation

- JUDGE FELIMON ABELITA III VS. P/SUPT. GERMAN B.DORIA and SPO3 CESAR RAMIREZDocument2 pagesJUDGE FELIMON ABELITA III VS. P/SUPT. GERMAN B.DORIA and SPO3 CESAR RAMIREZshezeharadeyahoocom100% (1)

- People Vs UybocoDocument12 pagesPeople Vs UybocoelCrisPas encore d'évaluation

- Court Rules in Favor of Petitioners in Illegal Gambling CaseDocument3 pagesCourt Rules in Favor of Petitioners in Illegal Gambling CasemmaPas encore d'évaluation

- People Vs GoDocument2 pagesPeople Vs GoUlyssis Bangsara100% (1)

- SC nullifies 42 search warrants in Stonehill caseDocument4 pagesSC nullifies 42 search warrants in Stonehill caseElaine Dianne Laig SamontePas encore d'évaluation

- Alvero vs. DizonDocument1 pageAlvero vs. Dizoncallcenterlife_1977Pas encore d'évaluation

- People Vs CayagoDocument4 pagesPeople Vs CayagoGlomarie GonayonPas encore d'évaluation

- Genuino V de LimaDocument2 pagesGenuino V de LimaMark Aries LuancingPas encore d'évaluation

- Papa v. MagoDocument3 pagesPapa v. MagoSheekan100% (4)

- 61 Kho Benjamin VDocument2 pages61 Kho Benjamin VRuiz Arenas AgacitaPas encore d'évaluation

- People vs. Suzuki DigestDocument3 pagesPeople vs. Suzuki DigestLiz LorenzoPas encore d'évaluation

- Rosana Asiatico vs. People of The Philippines DigestDocument1 pageRosana Asiatico vs. People of The Philippines DigestJaen TajanlangitPas encore d'évaluation

- Lim vs. Mindanao WinesDocument1 pageLim vs. Mindanao WinesMjay GuintoPas encore d'évaluation

- SEARCH AND SEIZURE CASE REVERSES CONVICTIONDocument1 pageSEARCH AND SEIZURE CASE REVERSES CONVICTIONBananaPas encore d'évaluation

- Asuncion vs. CA, 302 SCRA 490 (1999)Document2 pagesAsuncion vs. CA, 302 SCRA 490 (1999)Lloyd David P. VicedoPas encore d'évaluation

- Marcos Vs CruzDocument2 pagesMarcos Vs CruzCarlota Nicolas VillaromanPas encore d'évaluation

- People of The Philippines vs. Noel BartolomeDocument2 pagesPeople of The Philippines vs. Noel BartolomeAdreanne Vicxee TejonesPas encore d'évaluation

- Salcedo-Ortanez VS CaDocument1 pageSalcedo-Ortanez VS CaJoannah GamboaPas encore d'évaluation

- Del Castillo vs. PeopleDocument4 pagesDel Castillo vs. PeopleMarisseAnne CoquillaPas encore d'évaluation

- Stephen Sy V PeopleDocument2 pagesStephen Sy V PeopleOculus DecoremPas encore d'évaluation

- People vs Solayao ruling on admission of homemade firearm evidenceDocument1 pagePeople vs Solayao ruling on admission of homemade firearm evidenceMaria Victoria Dela TorrePas encore d'évaluation

- People Vs CrisologoDocument2 pagesPeople Vs CrisologoBryne Boish100% (1)

- People Vs CabilesDocument1 pagePeople Vs Cabilesabethzkyyyy100% (1)

- People vs. de Gracia - G. R. Nos. 102009-10 (Case Digest)Document2 pagesPeople vs. de Gracia - G. R. Nos. 102009-10 (Case Digest)Abigail TolabingPas encore d'évaluation

- 518 People VS CabanadaDocument1 page518 People VS CabanadaJERICHO JUNGCOPas encore d'évaluation

- People Vs LuceroDocument1 pagePeople Vs Luceroistefifay100% (1)

- Picop v. AsuncionDocument3 pagesPicop v. AsuncionTherese AmorPas encore d'évaluation

- SC Rules on Validity of Search Warrant and Seizure of DrugsDocument6 pagesSC Rules on Validity of Search Warrant and Seizure of DrugsRaine VerdanPas encore d'évaluation

- People of The Philippines Vs Chua Ho SanDocument2 pagesPeople of The Philippines Vs Chua Ho SanJohn Leo SolinapPas encore d'évaluation

- Pp. v. Johnson, Pp. V Bariquit.1Document2 pagesPp. v. Johnson, Pp. V Bariquit.1Josephine BercesPas encore d'évaluation

- Pil-Ey Vs PeopleDocument11 pagesPil-Ey Vs PeopleAnitoPas encore d'évaluation

- Larranaga vs. CADocument1 pageLarranaga vs. CALePas encore d'évaluation

- Consequences of Failing to Inform Suspect of Rights during Custodial InterrogationDocument2 pagesConsequences of Failing to Inform Suspect of Rights during Custodial InterrogationCarlyn Belle de Guzman50% (2)

- Borlongan vs. PenaDocument3 pagesBorlongan vs. PenaMichelle Montenegro - AraujoPas encore d'évaluation

- PP Vs CFI DigestDocument1 pagePP Vs CFI DigestJuLievee Lentejas100% (1)

- SC Upholds Warrantless Arrest, Seizure of Drugs in Plain ViewDocument2 pagesSC Upholds Warrantless Arrest, Seizure of Drugs in Plain ViewTintin Co100% (1)

- People V Dy DigestDocument2 pagesPeople V Dy DigestMartin Alfonso100% (1)

- 00 Compiled Crimpro Digests (Arrest Part II)Document70 pages00 Compiled Crimpro Digests (Arrest Part II)Janz SerranoPas encore d'évaluation

- (CRIMPRO) 190 PeopleVRacho SoonDocument2 pages(CRIMPRO) 190 PeopleVRacho SoonJoshua Cu SoonPas encore d'évaluation

- Terry vs. OhioDocument2 pagesTerry vs. OhioLaw StudentPas encore d'évaluation

- Gozos Vs Tac-An - 123191 - December 17, 1998 - J. Mendoza - Second Division PDFDocument9 pagesGozos Vs Tac-An - 123191 - December 17, 1998 - J. Mendoza - Second Division PDFShaira Mae CuevillasPas encore d'évaluation

- People Vs GalitDocument1 pagePeople Vs GalitGeorge AlmedaPas encore d'évaluation

- 787 Salvador v. People ColoquioDocument1 page787 Salvador v. People ColoquioAaron ThompsonPas encore d'évaluation

- People Vs Dela Cruz DigestDocument2 pagesPeople Vs Dela Cruz DigestmenforeverPas encore d'évaluation

- Libuit Vs PeopleDocument2 pagesLibuit Vs PeoplepandambooPas encore d'évaluation

- Military raid during coup d'etat upheld as valid without warrantDocument1 pageMilitary raid during coup d'etat upheld as valid without warrantmartinmanlodPas encore d'évaluation

- 74 - Digest - Lozano V Martinez - G.R. No. L-63419 - 18 December 1986Document2 pages74 - Digest - Lozano V Martinez - G.R. No. L-63419 - 18 December 1986Kenneth TapiaPas encore d'évaluation

- Olmstead Vs USDocument27 pagesOlmstead Vs USVienie Ramirez BadangPas encore d'évaluation

- Case 14 People Vs AndanDocument1 pageCase 14 People Vs AndanBadez Timbang Reyes100% (3)

- People vs. SalanguitDocument2 pagesPeople vs. SalanguitApril Joyce NatadPas encore d'évaluation

- People V AgustinDocument2 pagesPeople V AgustinistefifayPas encore d'évaluation

- People Vs CorreaDocument2 pagesPeople Vs CorreaRmLyn Mclnao100% (1)

- People Vs OlbisDocument4 pagesPeople Vs OlbisRandyPas encore d'évaluation

- Miranda VDocument26 pagesMiranda VErika Mariz Sicat CunananPas encore d'évaluation

- Affidavit of Same PersonDocument2 pagesAffidavit of Same PersonƎlro Mar TabiliranPas encore d'évaluation

- Affidavit (Alawi)Document1 pageAffidavit (Alawi)Ǝlro Mar TabiliranPas encore d'évaluation

- Affidavit of Same Person (Carig)Document2 pagesAffidavit of Same Person (Carig)Ǝlro Mar TabiliranPas encore d'évaluation

- Sale Motor Vehicle DeedDocument2 pagesSale Motor Vehicle DeedChirenPas encore d'évaluation

- Special Power of Attorney: ENGR. DIOSCORO ENDAB, of Legal Age, Filipino, Married andDocument2 pagesSpecial Power of Attorney: ENGR. DIOSCORO ENDAB, of Legal Age, Filipino, Married andƎlro Mar TabiliranPas encore d'évaluation

- Acknowledgement Receipt (Jamorol)Document1 pageAcknowledgement Receipt (Jamorol)Ǝlro Mar TabiliranPas encore d'évaluation

- Affidavit of Two Disinterested Person (Gandola) 3Document2 pagesAffidavit of Two Disinterested Person (Gandola) 3Ǝlro Mar TabiliranPas encore d'évaluation

- Anti BullyingDocument15 pagesAnti BullyingƎlro Mar TabiliranPas encore d'évaluation

- Special Power of Attorney: ID No. ID No. CRN: Issued By: Laguna SSS Issued By: Rizal COMELECDocument2 pagesSpecial Power of Attorney: ID No. ID No. CRN: Issued By: Laguna SSS Issued By: Rizal COMELECƎlro Mar TabiliranPas encore d'évaluation

- International Humanitarian Law Flowchart 2Document1 pageInternational Humanitarian Law Flowchart 2Rainier Rhett ConchaPas encore d'évaluation

- FDLE - Application For Certificate of Eligibility To Expunge or SealDocument1 pageFDLE - Application For Certificate of Eligibility To Expunge or SealDavid WeisselbergerPas encore d'évaluation

- Fair Trial in IndiaDocument31 pagesFair Trial in Indiaarchit jainPas encore d'évaluation

- SC upholds conviction for illegal recruitment despite claims money was turned over to agencyDocument2 pagesSC upholds conviction for illegal recruitment despite claims money was turned over to agencyemen penaPas encore d'évaluation

- Case DigestDocument6 pagesCase Digestpoiuytrewq9115Pas encore d'évaluation

- Crim I DigestsDocument7 pagesCrim I DigestsBinkee VillaramaPas encore d'évaluation

- Guide For The Mexican MigrantDocument17 pagesGuide For The Mexican MigrantBarbara EspinosaPas encore d'évaluation

- Prejudicial QuestionDocument8 pagesPrejudicial QuestioncaseskimmerPas encore d'évaluation

- Introduction: Nature and Extent of Crime in IndiaDocument15 pagesIntroduction: Nature and Extent of Crime in Indiashreya patilPas encore d'évaluation

- Drafting Previous Year Question PaperDocument8 pagesDrafting Previous Year Question PaperRVPas encore d'évaluation

- Cdi-3 Study MaterialsDocument4 pagesCdi-3 Study Materialsyuan sanchezPas encore d'évaluation

- 017 People v. RullepaDocument3 pages017 People v. RullepaKoko GalinatoPas encore d'évaluation

- Dacanay Vs PeopleDocument3 pagesDacanay Vs PeopleKarina Katerin BertesPas encore d'évaluation

- IndictmentDocument34 pagesIndictmentDavid GuraPas encore d'évaluation

- Life Imprisonment Vs Capital PunishmentDocument104 pagesLife Imprisonment Vs Capital PunishmentHvonNiflheimPas encore d'évaluation

- Office of The Clerk: Case TopicsDocument44 pagesOffice of The Clerk: Case TopicsSteve OutstandingPas encore d'évaluation

- Regional Trial Court: Annex "1". Annex "2"Document10 pagesRegional Trial Court: Annex "1". Annex "2"Norman G. TansingcoPas encore d'évaluation

- Criminal Due ProcessDocument18 pagesCriminal Due ProcessJoanne Marie BolandoPas encore d'évaluation

- State-of-Tamil-Nadu-v-Nalini Case MemorialDocument29 pagesState-of-Tamil-Nadu-v-Nalini Case MemorialBhuvaneswari Ram Motupalli50% (2)

- Teehankee CaseDocument19 pagesTeehankee CasericciongPas encore d'évaluation

- Prosecution of Public Servant On Private ComplaintDocument10 pagesProsecution of Public Servant On Private ComplaintHunny ParasharPas encore d'évaluation

- Basic Bond-Motion To Reduce Bond For The Jail Magistrate CouDocument5 pagesBasic Bond-Motion To Reduce Bond For The Jail Magistrate CouJoshua SmithPas encore d'évaluation

- The Pakistan Criminal Law Amendment Act, 1958: ACE Guide BookDocument7 pagesThe Pakistan Criminal Law Amendment Act, 1958: ACE Guide BookTaifoor KhanPas encore d'évaluation

- Accomplice ApproverDocument4 pagesAccomplice ApproverMichael GreenPas encore d'évaluation

- United States v. CooleyDocument10 pagesUnited States v. CooleyKolby Kicking WomanPas encore d'évaluation

- Galman Vs Pamaran Re Self Incrimination ClauseDocument2 pagesGalman Vs Pamaran Re Self Incrimination ClauseMia AngelaPas encore d'évaluation

- Army Institute of Law National Moot Court Competition 2016: Team Code: Ck9Document37 pagesArmy Institute of Law National Moot Court Competition 2016: Team Code: Ck9Abhigyat ChaitanyaPas encore d'évaluation

- Pre Trial Brief RAPEDocument2 pagesPre Trial Brief RAPEBleizel TeodosioPas encore d'évaluation

- Patrick Reese Appellate DecisionDocument18 pagesPatrick Reese Appellate DecisionPennLivePas encore d'évaluation

- 97 People Vs MamantakDocument2 pages97 People Vs MamantakMichaela PradesPas encore d'évaluation