Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Phonetics Lecture

Transféré par

resfreakCopyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Phonetics Lecture

Transféré par

resfreakDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

PHONETICS The study of the sound system of all languages is called phonetics.

For words to have meanings, they must be made up of different sounds so that they are distinctive. English, for instance, depending on the variety to which it belongs is made up of 40 contrastive sounds, while only 26 alphabet letters exist to represent the sounds of English language. To have one symbol representing one distinct sound, the International Phonetic Alphabet was developed. How is speech produced? Most speech sounds are formed when air passes through the larynx past the vocal folds.

This sound is modified in the nose, throat and oral cavity to produce the distinctive sounds of all the languages. All of the sounds of English are produced through this process called the pulmonic egressive airstream mechanism. However, some languages like Kpelle, spoken in Liberia, have sounds made through the intake of air, which is modified as the air goes through the mouth, a process

called the ingressive airstream mechanism. Press your lips together as if you were going to make the [b] sound, but instead of sending air out of your mouth, suck in air as you release your lips and make a [b] sound. This is different from the egressive [b]. This [b] is the first sound in the Kpelle word banan (camp kitchen). The consonants Consonants are sounds made by obstructing the airstream in differing ways after it leaves the lungs. They are produced by three mechanisms: Voicing-the vibration of the vocal folds Manner of articulation-modification of the airstream as it travels through the larynx and mouth Place of articulation-the movement of articulators where the main modification of the airstream takes place Voicing When air rushes out of the lungs and pushes past the closed glottis, the folds open and shut rapidly causing a vibration.

For instance, the sound [s] is made in exactly the same way as the sound [z], except that for [z], the vocal folds vibrate. This distinctive vibration is known as voicing. It is one of the three features humans use to distinguish the sounds of their languages. There are many other sets of sounds that only differ by this feature of vibration. These sets of sounds are known as minimal pairs. Examples of minimal pairs include [t] and [d], [k] and [g], [s] and [z].

Place of articulation A second descriptor of consonants is to note which articulator, in combination with the tongue, is used to modify the airstream to produce a particular consonant. The articulators are: Lips-labials Teeth-dental or interdental Alveolar ridge-raised part of the mouth above the teeth Palate-top of mouth Velum-the extreme back of the roof of the mouth For instance, for the words tight and kite, the only difference in pronunciation is that the front of the tongue is touching the alveolar ridge when the word begins, and the back of the tongue is raised towards the back of the mouth for the word kite Manner of articulation The third aspect of making a consonant is how the airstream is blocked and released in the vocal cavity. Airstream may be allowed to flow without obstruction by any articulators as it travels out of the larynx It may be partially or completely obstructed at different places in the mouth and throat. Stops or Plosives Stops or plosives occur when, in the production of a consonant, the air cavity is completely blocked for a short time before it is released. A little puff of air explodes from the mouth when the consonant is released. English speakers use three sets of consonants made in three places in the mouth [p] and [b] are made with the lips closing completely to block the air which is then released [t] and [d] which are produced when the tongue blocks the air from escaping at the alveolar ridge [k] and [g] are produced when the back of the tongue rises to close off the air at the back of the mouth. Another stop, which is not in a paired set occurs only in some varieties of English. It is called the glottal stop. It can occur in American English expressions in non-word expressions such as: Uh-oh Uh-uh Uh-huh Whoops No Yes

You can also say these words with your lips closed in which case the sound that comes out approximates: M?m Mhm The glottal stop occurs in varieties of Cockney English where it systematically replaces the [t] sound in words like bottle [bo?l]. Variations in stop sounds Aspiration occurs whenever [p] or another voiceless stop are the first sound in a word or syllable, like in the word pepper. When these sounds occur at the end of a syllable or word, like in the word step, they are unaspirated, meaning that the puff of air associated with aspirated sounds is greatly reduced.

Switch the normal pronunciation of the words pat and stop. It is possible to aspirate the final stop in [p], but it is not normal English pronunciation. Slight changes in tongue position can also make a noticeable difference in the pronunciation of stops. For instance, Latin American Spanish speakers block the airstream at the teeth and not the alveolar ridge, when making the [t] and [d] sounds. This is one of the many differences that contributes to their accents when speaking another language such as English. Stops and the past tense in English Past tense endings in English are produced systematically. It is the final sound in the root word, which determines the ending the word will take in the past tense. If the root ends in a voiced sound (the vocal folds vibrate), then the suffix that gets added will also be voiced, that is the [d] ending. Example, roam-roamED For a root word that ends in an unvoiced sound, the [t] suffix is used. For instance, the word walk ([k] being an unvoiced sound) gets the voiceless [t]. If the root ends in [t], then a vowel [Id] is used to make it easier to say. Example, elect-elect[Id]. The same is done for root words ending in [d]. Example, record-record[Id].

Try finding out the endings for the following: Xerox Fedex Sob Count load Oral and nasal stops At the very back of the mouth is the velum, which is moveable. When the velum is lowered, the air coming up from the lungs escapes through the nasal cavity instead of through the mouth . The sounds created when the air passes over the velum and out through the nose are called nasal sounds. English has three nasal stops: [m]---voiced bilabial stop [n]----voiced alveolar stop [ng]---sing, ring Fricatives Fricatives are another manner of articulation. Fricative consonants are formed by bringing two articulators close together and forcing the air through the remaining space, with the movement of air generally causing a hissing or rushing sound. English has pairs of voiced and unvoiced fricatives at several places of articulation: Labiodental fricative Interdental fricative Voiced alveolar ridge [f] [v] [ ] theta as in though [ ] eth as in thought. [s] as in sip, trucks, mistake and [z] as in zip, buzzard, zoo

Two sounds are produced with the tongue raised towards the centre of the palate which differ only by voicing. [] ship [] pleasure, measure, leisure, genre The final point of articulation to create fricative sounds is the glottis. The fricative, [h], as in hot is unvoiced. Airstream passes without obstruction or modification through the glottis and out of the mouth. Labiodental, interdental, alveolar, palatal, glottal

Affricates A third manner of articulation is created when the airstream is stopped for a very brief instant at the palate and then forced through a narrow space, thus making these sounds a combination of a stop and fricative: [] church [d] judge

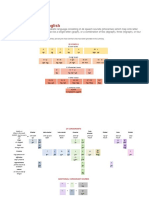

Liquids and Glides The final two categories for English manner of articulation are the liquids and glides. These sounds are produced with little or no obstruction of the airstream: Glides Liquids Vowels Written English has only six vowel letters, but it actually has 11 or mor vowel sounds that are commonly pronounced by speakers of varieties of English across the world. Vowels differ from consonants in that the airstream is never blocked or even seriously constricted by the articulators. Unlike most consonants, they can stand alone. Classification of vowels Vowels are classified by some basic features: Tongue height Part of the tongue being raised Shape of lips high, mid or low in the mouth tip, middle or back spread, neutral or round bilabial alveolar, both voiced [w] wet [l] let [r] red palatal [j] yellow (both are voiced)

Other descriptors can include tenseness and laxness depending on the muscular tension used to produce them, and duration the vowel is held.

The vowel chart The vowel chart is made to roughly approximate the shape of the tongue with the tip of the tongue represented at the left side of the chart.

Vowel symbol examples:

Diphthongs Three very common vowel sounds in English are known as the diphthongs. They are a combination of two sounds (a vowel + glide) resulting in a single unit: [aw] [aj] [j] flout I toy cow fly toil cloud wide moist

Vowel length In English, vowel length is not a contrastive feature. For example, in Finnish, the double or single iteration of a vowel changes the meaning: Tapaan sinut puistossa Tapan sinut pusitossa I will meet you in the park I will kill you in the park

Vowel duration

bit/beet bet/bait food/foot Suprasegmentals Aspects of speech that influence stretches of sound longer than a single segment are known as suprasegmentals. Segments are vowels, consonants, which combine to produce syllable, word, sentence. Aspects include: Length, tone, intonation, syllable structure, stress Length Difference in vowel length can depend on how different vowels are articulated. Lowe vowels (mouth open wide) and high vowels (little movement needed) take less time to articulate. Sometimes two segments may differ in how long they are held while everything else remains the same. While in Japanese, length distinctions exist for both consonant and vowels, in English long and short consonants within words are not differentiated. Vowel length can change meanings: Hawaiian Kau to place Ku to belong to you Kala to forgive Kla money Ka l the sun In English, if you were to pronounce beat the same as bead, the pronunciation could sound strange but the meaning would remain the same. Intonation, syllable, stress

Phonology The aim of phonology is to discover the principles that govern the way sounds are organized in languages, and to explain the variations that occur. For instance, consider the following: Ngfri Rkba fring tark firing bark

Although the second word has no established meaning in English, it follows an established sound pattern as seen in the third example. Therefore, it has the possibility of gaining meaning. On the other hand, Ngfri or Rkba is not a recognized pattern in the English language. Individual languages are analyzed to determine which sound units are used and which patterns they form-the languages sound system. The difference between phonetics and phonology can be seen from another point of view. The human vocal apparatus can produce a wide range of sounds, but only a small number of these are used in a language as units to construct all of its words and sentences. For example, some languages such as Rotokas in Pacific Islands use only 11. By contrast, Xu in southern Africa has 141. English has 44. Whereas, phonetics is the study of all possible speech sounds, phonology studies the way in which speakers of a language systematically use a selection of these sounds in order to express meaning. Further, no two speakers have anatomically identical vocal tracts, and thus no one pronounces sounds in exactly the same way as anyone else. Considerable variation exists also in the sounds produced by a single speaker. While acoustically, there may be much variation in sounds produced by speakers of the same language, much of this variation is discounted by us as we interact with fellow speakers. Identifying phonemes Certain sounds cause changes in the meaning of a word or phrase, whereas other sounds do not. A simple methodology to demonstrate this, which is the minimal pairs test, is to take a word, replace one sound by another, and see whether a different meaning resulted. For example, consider: Pan-ban, par-bar, pat-bat Changing [p] and [b] within these words results in a change of meaning. Similarly, [i] and [e] are important sounds in English they help to distinguish between pin and pen, tin and ten. This approach has its limitations as it can be difficult to find pairs of words, but it has worked quite well in English. There are 44 important (distinguishable) sound units in English. These units are called phonemes. Phonemes are transcribed not within square brackets but within forward slashes /p/, /b/, /t/. etc Identifying allophones When we try to work out the inventory of phonemes in a language using this approach, we soon come across sounds that do not change the meaning, when we make substitutions. For instance, consider the consonants at the beginning of shoe and she. They seem the same, but in fact they have

very different sound qualities. For shoe, the lips are rounded, because of the influence of the following [u] vowel; for she, the lips are spread. If we now change substitute one of these sounds for the other, we do not get a change of meaning-only a rather strange sounding pronunciation. There is only one phoneme here, which we can represent as/f/, but it turns up in two different phonetic shapes or variant forms, in the two words. These phonetic variants of a phoneme are known as allophones. Consider leaf and pool. Although the first l is pronounced much further forward in the mouth than the second l, both are allophones of the single phoneme /l/. Simply, these are pronunciation changing rather than meaning changing differences. Identifying distinctive features We need to recognize smaller units than the individual phoneme, in order to explain how sets of sounds are related. We can see this by comparing any two contrasting phonemes in English, using the articulatory criteria. For instance, /p/ and /b/ are both bilabial, plosive, oral, and pulmonic egressive. They differ only in that /p// is voiceless and /b/ is voiced. /p/ and /g/ differ in voicing and being bilabial vs velar. /p/ and /z/ differ in voicing, as well as manner (plosive vs fricative) and place of articulation. We can use the and + signs to indicate the absence and presence of distinctive features in these phonemes, e.g [n] is voiced and nasal so we note it as [+voiced] and [+nasal]. [p] is unvoiced and bilabial so we note it as [-voice] and [-nasal] Identifying syllables In a phonological approach, we focus on the way sounds combine in a language to produce typical sequences. Syllables are seen as combinations of vowels and consonants. Vowels (V) are now defiend as units which can occur on their own, or which appear at the centre of a sequence of sounds. Consonants (C ) are units which cannot occur on their own or which appear at the edge of a sequence. Typical sequences in the English language are CV see, CVC hat, CCVC stop and CVCC pots. Some languages use only V or CV syllables (e.g Hawaiian). English can have as many as three consonants before a vowel, CCCVC strap and sprig. Not all combinations of consonant and vowel can occur in a language. In English, we can combine /s+t+r/ to produce words such as string, strum, strip but we cannot put together /f/ with /t/ and /r/. There is no word in English beginning with shtr. An allomorph is a different phonological version of a morpheme. This occurs when the surface detail of the morpheme is different, but the deeper meaning remains the same. This commonly occurs when the letters performing the same function, such as plurality or time, produce a different sound or use different letters. Examples of plural allomorphs include the difference between pots and taxes. The studying of allomorphs is part of the studying of morphology in linguistics. A morpheme is a basic unit of representing meaning in a language. These meanings can be either lexical, in that they provide information, or structural. Intolerant, for example, has three morphemes: in-toler-ant. All three elements of intolerant are lexical morphemes. Toler is the root stem indicating the ability to endure or embrace something. The in morpheme means that there is no tolerance and the ant at the end indicates someone who is intolerant. There are several types of morpheme. Free morphemes can exist as a word in their own right. An example of this is the break in unbreakable. On the other hand, morphemes such as toler in tolerant are bound morphemes because they cannot exist unless modified by other morphemes. The allomorph is a bound morpheme that only occurs in order to modify a stem word.

difference in sound of the s in pots, dogs and taxes when spoken aloud. The s in pots sounds like a phonetic [-s], while the s in dogs is more of a phonetic [-z]. The es of taxes, with the e used to separate the x and s, is a phonetic [<<="" p=""> Dative morphemes used with verbs can also become allomorphs. The regular past tense allomorph is -ed. There is a difference in sound between wanted, fired and dashed. Like with the plurals, each variation has a different sound while appearing to be the same on paper. The first is a phonetic [-ed], the second [d] and the third [t]. A regular allomorph can have different sounds. Irregular morphemes are also allomorphs. This means the irregular plural found in sheep and fish are also allomorphs of s. This can occur through the merger of dialects, which produced children. It can also occur when loan words are imported from another language such as with the difference between datum and data, both of which are from Latin. Each allomorph is fixed in position. This means that one form, whether written or pronounced, can be replaced with another. For example, sheep will be the plural of sheep and will not be replaced with sheeps or sheepen. In language studies, such immovability is called complimentary distribution. Phonological rule writing Patterns of interaction between speech sounds in a language can be described formally by writing phonological rules. The rules state the environment in which one sound or class of sounds changes into another. These rules are shorthand notations for various sound relationships. And understanding phonetic features and natural classes helps one to write out various types of pholological rules. 1. For instance, knowing the natural classes of sounds helps in describing the complementary environments of allophones of the same phoneme. 2. Thinking in terms of phonetic features also facilitates the writing of phonological rules, or rules of sound change. a.) Phonological rules can be used to describe historical change (change of [p] to [f] in Germanic). b.) Phonological rules can also be used to describe sound alternations that regularly occur in connected speech. (Give an example of the rule of loss of aspiration--pack, Bill's pack; towel, John's towel-- and of vowel nasalization in English--silly, silly name; yellow mask). Such processes occur every time people speak. And they might be quite different than the phonological processes that occurred in the language's history (e.g., pater --> father; but father --> Bill's father, not *Bill's pather). The alternation between [p] and [f] is historical and not productive in the language; the alternation between [p] and [ph] is productive and occurs as a regular part of speech. Phonological notation can describe both types of sound changes--the productive, contemporary ones; and the nonproductive, historical ones. (Sometimes a historical change can be underway in the present [] to [w] for example; sometimes a change that happened in history can still be productive in a language, as the regressive voicing assimilation rule in Russian.) Another type of phonological rule, called a phonotactic constraint, defines what sound combinations may and may not occur in a language. If you knew all the speech sounds present in a language you still wouldn't be able to make words without knowing the phonotactic constraints operating in that language. For example the sound at the end of /sing/ occurs only in syllable-final position, [h] can only occur in syllable initial position. Another phonotactic constraint prevents [Z] from occurring at the beginning or at the end of native English words (this rule might be changing under the influence of borrowed foreign names such as "Zsa-Zsa, Jacques, Zhanna, etc."). Phonotactic rules could be called phonetic syntax. Here are some phonotactic constraints of English: a.) Word/syllable initial: no [N], only specific types of clusters: s + voiceless plosive + liquid; or s + sonorant; or plosive + sonorant b.) Word/syllable final: no [h] c.) Word/syllable medial-- must be a vowel, no liquid.

Phonotactic constraints gradually change through time (just like the number of phonemes changes through time). The following word initial clusters have dropped out of English: [kn], gn], [xr], [xl]. Often, combinations of sounds that are allowed by the phonotactic rules of a language are not actually used as words: [zib], [charp], [squill]. These are called accidental gaps in the vocabulary of a language; they are potential words--perhaps someone will tomorrow use [charp] to describe the green mutant potato chip found at the bottom of a bag of chips. Every language has its own unique set of phonotactic constraints. Sound combinations that could not possibly be English words might very well be words in another language. For instance both English and Georgian have the sound segments [t], [A], [m]. In English we have Tom but no mot, mta or tma; although mot could be a word. In Georgian we have mta, mountain; and tma hair, but no tom or mot. Foreign borrowings often cause changes in phonotactic rules (just like they can lead to the adoption of a new phoneme). Due to the influence of the original French, many people pronounce a final [Z] instead of [dZ] in garage. Also note the sound combination [sv] in svelte, Sven and a few other words from Scandinavian languages. As a final example, notice that the name Schmidt from German entered the language even though it violated the phonotactic rules of English. Such is also the case with many borrowings from Yiddish that contain consonsant clusters beginning with the sound [sh]: schmooze, schmuck, shlep, shlok. Such foreign borrowings often eventually result in changes in a language's phonotactic rules. Other phonological rules describe the changes that occur in sounds when they are brought together. You will recall that in fusional languages, the morphemes alter their phonetic shape to accommodate the sound of adjacent morphemes. Let's classify these type of changes on phonological grounds. These rules may be classified according to the type of phonetic change that occurs. 1) Feature deletion or addition rules. Lengthening of English consonants before voiced obstruents. a) Assimilation rules (the feature added is present in an adjacent segment) nasalization of English vowels before nasals. b) Dissimilation rules (the feature deleted is present in an adjacent segment) deletion of aspiration after [s]. Assimilation and dissimilation may be progressive (velarization of English [l]) or regressive (nasality in English vowels). 2) Segment deletion or addition rules (a whole sound is added or subtracted) French, also Eng.: autumn, autumnal; athlete/"athalete". Adding schwa between sibilants when adding the English plural ending: boxes. 3) Metathesis rule reorders the segments that are present: ask/aks; nuclear, "nucular", Georgian: dzrokhi/rdze. These are examples of a rule randomly applied. For an example of a metathesis rule regularly applied, see also the example from Hebrew on p 250.

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (399)

- Trustees of Princeton UniversityDocument34 pagesTrustees of Princeton UniversityresfreakPas encore d'évaluation

- Bad Feminist - VQR OnlineDocument10 pagesBad Feminist - VQR OnlineresfreakPas encore d'évaluation

- UCAS Personal StatementDocument2 pagesUCAS Personal StatementresfreakPas encore d'évaluation

- 9686 s08 Ms 2 PDFDocument9 pages9686 s08 Ms 2 PDFresfreakPas encore d'évaluation

- AsiaTEFL Book Series-ELT Curriculum Innovation and Implementation in Asia-Teachers Beliefs About Curricular Innovation in Vietnam A Preliminary Study-Le Van CanhDocument26 pagesAsiaTEFL Book Series-ELT Curriculum Innovation and Implementation in Asia-Teachers Beliefs About Curricular Innovation in Vietnam A Preliminary Study-Le Van CanhresfreakPas encore d'évaluation

- 9686 s08 Ms 2 PDFDocument9 pages9686 s08 Ms 2 PDFresfreakPas encore d'évaluation

- Cognitive Aspects of Language LearningDocument9 pagesCognitive Aspects of Language LearningresfreakPas encore d'évaluation

- BeliefsOfTeachersStudents SelectedReferences 5october2015Document8 pagesBeliefsOfTeachersStudents SelectedReferences 5october2015resfreakPas encore d'évaluation

- Teachers MotivationDocument17 pagesTeachers MotivationTiong Suzanne100% (1)

- MappingDocument8 pagesMappingresfreakPas encore d'évaluation

- 9701 Y10 SyDocument72 pages9701 Y10 SySyEd Mohammed IfrahimPas encore d'évaluation

- Research Report - Monageng MogalakweDocument10 pagesResearch Report - Monageng Mogalakweioana_1611Pas encore d'évaluation

- 8686 w09 QP 2 PDFDocument8 pages8686 w09 QP 2 PDFresfreakPas encore d'évaluation

- 9686 s04 QP 3 PDFDocument2 pages9686 s04 QP 3 PDFresfreakPas encore d'évaluation

- 2003 KANG Use of Lab Beliefs Goals PracticesDocument26 pages2003 KANG Use of Lab Beliefs Goals PracticesLenorePoePas encore d'évaluation

- Cordination For The Month of Aug and Sept X ChemDocument4 pagesCordination For The Month of Aug and Sept X ChemresfreakPas encore d'évaluation

- AERA06 TinocaDocument16 pagesAERA06 TinocaMuhammad Abu BakrPas encore d'évaluation

- 9686 s03 QP 4 PDFDocument8 pages9686 s03 QP 4 PDFresfreakPas encore d'évaluation

- Horsley Paper IARTEM EJournal Vol3 No1Document19 pagesHorsley Paper IARTEM EJournal Vol3 No1resfreakPas encore d'évaluation

- SURP Checklist and Personal Statement RubricDocument2 pagesSURP Checklist and Personal Statement RubricresfreakPas encore d'évaluation

- Challenges For The New Government of GilgitDocument5 pagesChallenges For The New Government of GilgitresfreakPas encore d'évaluation

- Ejss 28 4 08Document12 pagesEjss 28 4 08resfreakPas encore d'évaluation

- Introduction To Research MethodologiesDocument23 pagesIntroduction To Research MethodologiesmadurangaPas encore d'évaluation

- Analyzing Texts and ExercisesDocument47 pagesAnalyzing Texts and ExercisesresfreakPas encore d'évaluation

- Apa CitingDocument2 pagesApa CitingresfreakPas encore d'évaluation

- Building TeamDocument9 pagesBuilding TeamresfreakPas encore d'évaluation

- Writing The Personal StatementDocument35 pagesWriting The Personal StatementresfreakPas encore d'évaluation

- PointsDocument1 pagePointsresfreakPas encore d'évaluation

- Developing Literacy in QuantitativeDocument21 pagesDeveloping Literacy in QuantitativeresfreakPas encore d'évaluation

- Color Code Creative Writing for CohesionDocument1 pageColor Code Creative Writing for CohesionresfreakPas encore d'évaluation

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (894)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (265)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (73)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)

- The Evidence. There Are Four Main Types of Evidence Used in Deducing TheDocument7 pagesThe Evidence. There Are Four Main Types of Evidence Used in Deducing TheviolettaPas encore d'évaluation

- Vietnamese For ForeignersDocument63 pagesVietnamese For ForeignersMeoLuoi13100% (1)

- Contrastive AnalysisDocument28 pagesContrastive AnalysisBerthon Wendyven Silitonga0% (1)

- Connie & Clive Part IIDocument2 pagesConnie & Clive Part IIGisela CarvalhoPas encore d'évaluation

- Diphthong: SN, ST, As in Sheet, Church, These, Place, Snack, and StreetDocument3 pagesDiphthong: SN, ST, As in Sheet, Church, These, Place, Snack, and StreetTalha KhanPas encore d'évaluation

- Learn Luganda Grammar and VocabularyDocument280 pagesLearn Luganda Grammar and VocabularyFrancisco José Da Silva100% (1)

- Sample WordsDocument24 pagesSample WordsMary Camille GambongPas encore d'évaluation

- Korean LettersDocument10 pagesKorean LettersLeymelynn LanuzaPas encore d'évaluation

- Speech-to-Speech TranslationDocument103 pagesSpeech-to-Speech TranslationFaithful FriendPas encore d'évaluation

- Eng Jhs 1 3 SyllabusDocument103 pagesEng Jhs 1 3 SyllabusDerrick SampahPas encore d'évaluation

- Double ConsonantsDocument4 pagesDouble ConsonantsAdriano BulhoesPas encore d'évaluation

- BTech I Yr Lab ManualDocument55 pagesBTech I Yr Lab ManualsainitishPas encore d'évaluation

- Ondering Loud: by Carla FosterDocument18 pagesOndering Loud: by Carla FosterdanPas encore d'évaluation

- Notes On African LinguisticsDocument29 pagesNotes On African LinguisticsAbuskidy Graphics GuruPas encore d'évaluation

- Major Differences Between Arabic and English Pronunciation Systems: A Contrastive Analysis StudyDocument19 pagesMajor Differences Between Arabic and English Pronunciation Systems: A Contrastive Analysis StudyRania FarranPas encore d'évaluation

- Fonetika VidpovidiDocument43 pagesFonetika VidpovidiСніжана ГіричPas encore d'évaluation

- Error in Pronunciation of Consonant and Vowel NDocument2 pagesError in Pronunciation of Consonant and Vowel Nem_bahtiarPas encore d'évaluation

- The 44 Sounds of English: 20 VowelsDocument2 pagesThe 44 Sounds of English: 20 VowelsKopi BrisbanePas encore d'évaluation

- Learning and Teaching Vowels - Messum (2002)Document19 pagesLearning and Teaching Vowels - Messum (2002)Pronunciation SciencePas encore d'évaluation

- Callan-Method-Teacher-9 e 10 PDFDocument263 pagesCallan-Method-Teacher-9 e 10 PDFMurilo Godoi100% (9)

- Sound Phonics Comparison ChartDocument1 pageSound Phonics Comparison ChartDiliana NeychevaPas encore d'évaluation

- Sanskrit Language Science PerfectionDocument7 pagesSanskrit Language Science PerfectionChandrima ChowdhuryPas encore d'évaluation

- Adding IngDocument7 pagesAdding IngAKSHATPas encore d'évaluation

- Course Outline BS EnglishDocument77 pagesCourse Outline BS EnglishKhurram MalikPas encore d'évaluation

- Long Vowels LessonsDocument10 pagesLong Vowels Lessonsaarti.takawane6610Pas encore d'évaluation

- PHONEMES AND MORPHEMES IN KABARDIANDocument121 pagesPHONEMES AND MORPHEMES IN KABARDIANjarubirubiPas encore d'évaluation

- Basic Curriculum 2018Document39 pagesBasic Curriculum 2018Ann MainitPas encore d'évaluation

- Steno 2Document11 pagesSteno 2Aqib BazazPas encore d'évaluation

- An Introduction To Linguistics PDFDocument136 pagesAn Introduction To Linguistics PDFPutrie ParamitaPas encore d'évaluation

- Permutations & Combinations DDPDocument20 pagesPermutations & Combinations DDPVibhu100% (1)