Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Three Mile Island: Objectivity and Ethics

Transféré par

gharmanCopyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Three Mile Island: Objectivity and Ethics

Transféré par

gharmanDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Ethics and Environmental Health | Mini-Monograph

Objectivity and Ethics in Environmental Health Science

Steve Wing

Department of Epidemiology, School of Public Health, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, North Carolina, USA

to distinguish truth, in the form of statements

During the past several decades, philosophers of science and scientists themselves have become about the world made by people, from reality,

increasingly aware of the complex ways in which scientific knowledge is shaped by its social con- the world itself (Hubbard 1990; Rorty 1989),

text. This awareness has called into question traditional notions of objectivity. Working scientists and to be self-critical about the ways scientists

need an understanding of their own practice that avoids the naïve myth that science can become create truths and facts in relation to the real

objective by avoiding social influences as well as the reductionist view that its content is determined world that they study.

simply by economic interests. A nuanced perspective on this process can improve research ethics This article explores how a contextual

and increase the capacity of science to contribute to equitable public policy, especially in areas such research practice can improve the rigor, ethics,

as environmental and occupational health, which have direct implications for profits, regulation, and social responsibility of environmental

legal responsibility, and social justice. I discuss research into health effects of the 1979 accident at health science. I use as a case example research

Three Mile Island near Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, USA, as an example of how scientific explana- on cancer incidence after the 1979 nuclear acci-

tions are shaped by social concepts, norms, and preconceptions. I describe how a scientific practice dent at Three Mile Island (TMI) near

that developed under the influence of medical and nuclear physics interacted with observations Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, USA. I consider how

made by exposed community members to affect research questions, the interpretation of evidence, unarticulated cultural views about the reliability

inferences about biological mechanisms in disease causation, and the use of evidence in litigation. of assumptions and evidence shaped the fram-

By considering the history and philosophy of their disciplines, practicing researchers can increase ing of questions, the design of research, and the

the rigor, objectivity, and social responsibility of environmental health science. Key words: cancer, interpretation of findings in the scientific litera-

chance, dose reconstruction, environmental justice, epidemiology, ionizing radiation, research ture as well as in the courtroom.

ethics, significance testing, Three Mile Island. Environ Health Perspect 111:1809–1818 (2003).

doi:10.1289/ehp.6200 available via http://dx.doi.org/ [Online 19 June 2003] Accident at Three Mile Island

Three Mile Island is in the Susquehanna River

about 16 km (10 miles) from Harrisburg, the

In politics, policy, and law, science has objectivity through independence from social capital of Pennsylvania, where the Susquehanna

emerged as an alternative to folk traditions, forces places science in the role of a religion’s cuts across parallel ranges of hills that rise hun-

religion, and superstition as a way to under- omniscient God (Harding 1991). The illogic dreds of meters above the river. Several smaller

stand and manipulate the material world. The of the naïve view of scientific objectivity has towns are located along the river near to TMI

value and prestige of the sciences derive not been described in physics, genetics, and epi- (Figure 1). Dairy and other farms are common

only from their erudition, explanatory power, demiology, as well as in mathematics and sta- in the area, which has a strong agricultural

and applied technology but from their per- tistics (Armstrong 1999; Hubbard 1990; tradition (Figure 2).

ceived objectivity. A common view among sci- Keller 1992, 1995; Kuhn 1970; Levins 1979; At 4:00 A.M. on 28 March 1979, a series

entists and lay persons alike is that scientific Levins and Lewontin 1985). of events began that led to a loss of control of

objectivity is a consequence of standardized The reluctance of scientists to acknowledge the nuclear chain reaction in the TMI Unit 2

methods of quantitative observation and the shaping of their work by social forces and reactor. For several days it was not clear how

experimentation. The scientific method, by their ongoing avowal of science as value-free or when the reactor could be shut down.

removing subjectivity and social influence, can be viewed as a self-serving argument against Uncontrolled releases of radioactivity to the

yields knowledge that is ostensibly trustworthy public oversight (Keller 1995). However, even environment began shortly after 4:00 A.M. on

and objective. among scientists who accept an ethic of social 28 March. Within hours, radiation monitors

Despite the persistence of this view, responsibility, attempts to salvage naïve objec- at the plant went off-scale because radiation

historians, philosophers, and scientists them- tivity persist because the alternative is perceived

selves have shown that it does not provide an to be a judgmental relativism in which there is This article is part of the mini-monograph “Ethical,

adequate account of the production of scien- no basis for adjudicating competing claims. Legal, and Policy Issues in Environmental Health

tific knowledge (Harding 1991; Holtzman Such relativism is anathema to the most basic Research.”

Address correspondence to S. Wing, Dept. of

1981; Hubbard 1990; Kuhn 1970). There are assumptions of science: that a real world exists Epidemiology, 2101F McGavran-Greenberg Hall,

several reasons why method cannot remove independent of human cognition, and that the- School of Public Health, CB#7435, University of

social influences from science. First, the ories and hypotheses about that world can be North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC 27599 USA.

content and methods of science are formed in tested by controlled methods of observation Telephone: (919) 966-7416. Fax: (919) 966-2089.

relation to answering questions or testing and experimentation. A logical alternative to E-mail: steve_wing@unc.edu

hypotheses that are socially embedded. both judgmental relativism and naïve objectiv- Several colleagues and anonymous peer reviewers

provided excellent critical comments on earlier drafts of

Second, scientific explanation requires lan- ity is “strong objectivity,” an objectivity this manuscript. I am indebted to the many people

guage, concepts, and models that are cultural attained through revealing, rather than conceal- whose lives were affected directly and indirectly by the

products. Although all sciences expend consid- ing, the cultural content and social forces that accident at Three Mile Island and especially to Marjorie

erable effort to rationalize concepts and termi- are embedded in science (Harding 1991). To and Norman Aamodt.

nology, these tools of inquiry are inevitably practice strong objectivity, scientists must con- This work was supported by National Institute of

shaped and transformed by historical forces. sider not only the technical aspects of their dis- Allergy and Infectious Diseases Grant Program on

Research Ethics 1T15 AA149650 and by National

Therefore, scientists cannot even see the world, cipline, but must also take into account its Institute of Environmental Health Sciences grants R25-

much less provide explanations of its workings, history, conceptual foundations, preconcep- ES08206 and R25-ES12079.

without a socially formed perspective. tions, taboos, and the social forces that shape its The author declares he has no conflict of interest.

Ironically, the belief that science could attain content and application. This requires scientists Received 7 January 2003; accepted 16 June 2003.

Environmental Health Perspectives • VOLUME 111 | NUMBER 14 | November 2003 1809

Mini-Monograph | Wing

levels exceeded the instruments’ measurement less than average annual background levels 1993; Dew et al. 1987a, 1987b; Fabrikant

capacity (Macleod 1981). Although thermo- (NRC 1979a; President’s Commission on the 1983; Gatchel et al. 1985; Houts et al. 1991;

luminescent dosimeters were placed off-site Accident at Three Mile Island 1979). Houts and Goldhaber 1981; McKinnon et al.

on 30 March, there were large angular gaps The official position that high-level 1989; Prince-Embury and Rooney 1988;

between the monitors (Beyea 1985). As a radiation exposures were impossible was ques- Schaeffer and Baum 1984).

result, there was little information about tioned by hundreds of local residents who Few studies took on the topic of radiation

early releases and poor capacity to detect nar- reported metallic taste, erythema, nausea, exposures. Ionizing radiation is considered to

row plumes with low dispersion. At the time vomiting, diarrhea, hair loss, deaths of pets be one of the best-understood carcinogens,

the region was experiencing unusually balmy and farm and wild animals, and damage to and scientists asserted that doses at TMI had

temperatures and low winds as an upper-level plants (Del Tredici 1980; Molholt 1985; been too low to produce any observable

cold air mass kept lower-level warm air from Osborn 1996; Three Mile Island Alert 1999). effects on cancer. Population dose estimates

rising—ideal conditions for trapping radioac- Many of these phenomena could be caused by and quantitative cancer risk estimates based

tive emissions (Steinacker and Vergeiner radiation; however, the maximum possible on studies of the survivors of the atomic

2002). Xenon-133 from TMI was detected dose was officially reported to be orders of bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki yielded

in Albany, New York (Wahlen et al. 1980). magnitude less than the dose needed to pro- a prediction of, at most, one accident-related

The possibility that a hydrogen explosion duce acute symptoms. Residents were told cancer death in the lifetimes of the population

in the reactor containment or a meltdown of that their symptoms were due to stress. in the 50-mile area (Hatch et al. 1990).

the reactor core would result in high-level People who pressed their concerns about radi- Therefore, there was no scientific reason to

radiation exposures generated great fear and ation were treated as though they had study health effects of radiation.

anxiety among officials and the public psychologic problems. Yet, concerns persisted that some areas near

(Del Tredici 1980; Gray and Rosen 1982). TMI had been exposed to high radiation levels

Lack of knowledge about details of the plant’s Epidemiology of the Accident during the accident. In 1984 Carl Johnson,

condition, lack of experience with this type of Health studies at TMI began to be planned former Director of Health in Jefferson County,

situation, and nonfunctional radiation moni- soon after the immediate danger had ended. Colorado, site of the Rocky Flats nuclear

tors gave rise to conflicting reports about the In June 1979, the Pennsylvania Department weapons plant, spoke at a public meeting at

severity of the accident and its threat to the of Health, working with the Centers for the Pennsylvania State University–Harrisburg

public. The Nuclear Regulatory Commission Disease Control and the U.S. Census Bureau, campus in Middletown, Pennsylvania. He

(NRC) reported a reading of 3,000 millirads conducted a special census of residents living described reports of symptoms consistent with

per hour taken above the plant on 29 March within 5 miles of TMI (Goldhaber et al. high-level radiation exposure that had been

(NRC 1979b). About 5–6% of people within 1983c). The University of Pittsburgh’s experienced during the accident in several hill-

5 miles of the plant left during the first 2 days Department of Radiation Health provided top neighborhoods near TMI (Johnson C.

of the accident. After Governor Thornburgh’s estimates of radiation doses for 5-mile area Unpublished data). Johnson’s description

30 March order to evacuate pregnant women residents “for educational, public relations piqued the interest of Marjorie Aamodt, an

and children from the 5-mile area, nearly 50% and defensive epidemiology purposes” (Gur experimental psychologist by training, who,

of residents left (Houts and Goldhaber 1981). et al. 1983). The demographics of evacuation with her husband, Norman Aamodt, an engi-

On 1 April, the hydrogen gas bubble began (Goldhaber et al. 1983a), medical care use, neer, had been participating in hearings regard-

to dissipate, and concerns of imminent danger and spontaneous abortion (Goldhaber et al. ing the restart of TMI Unit 1.

diminished. Industry and government repre- 1983b) were studied. Many studies of stress In the spring of 1984, Marjorie Aamodt

sentatives assured the public that only small have been published, making the 1979 acci- initiated a household survey in three hilltop

quantities of radiation had been released and dent at TMI one of the best-studied cases of communities with a total population of about

that exposures were far below levels that could psychologic response to disaster and evacua- 450 people. All three neighborhoods had

affect health. The NRC and a presidential tion (Baum 1990; Baum et al. 1983, 1993; unobstructed views of TMI at distances of

commission released reports indicating that the Cleary and Houts 1984; Cornely and Bromet between 3 and 8 miles (Aamodt and Aamodt

maximum possible off-site radiation dose was 1986; Davidson et al. 1987; Dew and Bromet 1984). Two of the communities were areas

Figure 1. View of TMI from the roof of an apartment building in Middletown, Figure 2. Farm in Londonderry Township near TMI, 4 July 1979. Photograph

Pennsylvania, 19 July 1979. Photograph copyright of Robert Del Tredici (Del copyright Robert Del Tredici (Del Tredici 1980) and used with permission.

Tredici 1980) and used with permission.

1810 VOLUME 111 | NUMBER 14 | November 2003 • Environmental Health Perspectives

Mini-Monograph | Objectivity and ethics in science

that Dr. Johnson had identified. Using a would have been a mistake to attribute high accident were much larger than had been

structured questionnaire designed with input cancer rates in a more exposed area to accident stated by industry and government officials;

from Dr. Johnson, Ms. Aamodt and several emissions if rates there were already higher meteorologic conditions and hilly terrain had

volunteers interviewed residents about symp- prior to the accident. Population counts caused the radioactive gases to disperse in nar-

toms and diseases experienced during and after according to age and gender for each year row plumes; and these intense plumes had

the accident. They obtained descriptions of from 1975 to 1985 were derived from census exposed small areas of the surrounding coun-

metallic taste, nausea, vomiting, hair loss, and data. The Columbia design permitted an eval- tryside to high radiation doses, resulting in

erythema, almost all from people who had uation of the relationship between estimated health impacts including cancer (Merwin et al.

been out-of-doors, as well as information on accident dose and cancer incidence for the 2001). Marjorie and Norman Aamodt were

the occurrences of cancers, cardiovascular dis- population within 10 miles of TMI, with consulting for plaintiffs’ attorneys and asked

eases, reproductive problems, dermatologic adjustment (control) for preaccident variation to meet with me to discuss the litigation. They

conditions, and ruptured/collapsed organs. in cancer incidence. Estimation of dose– provided documents including their health

Residents reported 19 cancer deaths during response relationships with adjustment for dif- survey, sworn affidavits from TMI neighbors,

1980–1984, compared with an expected num- ferences in risk between the exposure groups analyses of local mortality records, scientific

ber of 2.6. In June 1984, the Aamodts submit- prior to exposure is rarely possible in environ- articles, government reports, and letters and

ted a report to the NRC proceeding on the mental epidemiology. memoranda from scientists and government

competency of the utility to conduct surveil- Two publications by Columbia investiga- officials suggesting that radiation releases and

lance of radiation releases (Aamodt and tors describe cancer incidence in relation to doses from the accident had been substantial.

Aamodt 1984). the TMI accident (Hatch et al. 1990, 1991). They asked me to provide epidemiologic

The Aamodt survey soon came to the Hatch et al. (1990) reported positive associa- support for the plaintiffs in the suit.

attention of the TMI Public Health Fund. The tions between accident doses and non- I was wary of becoming involved in the

Fund, financed by the nuclear industry and Hodgkin’s lymphoma, lung cancer, and all lawsuit. Although I had not thoroughly stud-

administered by the Federal District Court in cancers combined. Leukemia, analyzed sepa- ied the TMI accident, I knew that allegations

Harrisburg, had been created in 1981 as part rately for children and adults, was also posi- of high radiation doses at TMI were consid-

of a settlement for economic losses from the tively associated with accident dose. However, ered by mainstream radiation scientists to be a

accident. Scientific advisors to the Fund veri- these estimates lacked statistical precision product of radiation phobia or efforts to extort

fied several aspects of the Aamodt study, because of small numbers (54 cases at all ages money from a blameless industry. Years of col-

including the ascertainment of cancer deaths combined). The authors reasoned that results laboration with epidemiologists and health

and calculation of expected deaths, and recom- did not “provide convincing evidence” that physicists aligned with the U.S. Department

mended a more comprehensive study of cancer TMI radiation releases had influenced cancer of Energy (DOE) Health and Mortality Study

in the TMI area. The Fund chose a team led in the area. Among the considerations weigh- had familiarized me with a culture in which

by Mervin Susser, a highly renowned epidemi- ing against a causal interpretation were concerned workers and community members,

ologist from Columbia University, New York, the lack of effects on the cancers believed to be most

as well as scientists who claimed there was evi-

New York, to design and conduct the cancer radiosensitive and the indeterminate effects on chil- dence of health effects of low-level radiation,

study. The Columbia investigators proposed dren . . . the low estimates of radiation exposure were viewed as threats to the nuclear industry

an innovative design that avoided several com- and the brief interval since exposure occurred. (Morgan 1992). Taking the plaintiffs’ allega-

mon problems that can lead to ambiguous tions seriously enough to become involved in

results in environmental epidemiology (Hatch They continued, any professional capacity might expose me to

et al. 1990). Pending a demonstration that very low dose ostracism and loss of scientific credibility.

Because concerns about cancer among gamma radiation can act as a tumor promoter or However, I was impressed with the

both patients and physicians could have the identification of another late-stage carcinogen intelligence and humanity of the Aamodts

resulted in earlier detection of cancer and in the effluent stream, an effect of plant emissions and with their thoughtful compilation of evi-

cause higher incidence rates as an artifact of in producing the unusual patterns of lung cancer dence. As in all research of this type, impor-

and non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma appears unlikely,

publicity, the Columbia group did not com- and alternative explanations need to be considered. tant measurements of interest had not been

pare TMI area residents to an unexposed con- made, case reports, statistical observations,

trol group from another area. Rather, they One alternative explanation was considered and related records were not entirely consis-

divided the 10-mile area into small study in a second report (Hatch et al. 1991). Using tent, and mechanisms for some putative

blocks, each of which was assigned an accident distance from TMI as the measure of psycho- effects were uncertain. Nevertheless, their sce-

dose based on a state-of-the-art dispersion logic stress, Hatch et al. considered the hypoth- nario of higher-than-reported doses did not

model that considered release estimates, mete- esis that increased cancer rates after the seem implausible. My reaction to the

orologic, and topographic data (Beyea and accident were caused by stress. Findings were Aamodts’ work was not only a function of

Hatch 1999). Dose estimates for the 69 study equivocal because of the speculative nature of evidence suggestive of high releases; it was

blocks varied by more than three orders of the mechanism of cancer promotion by stress- also a function of a willingness to consider the

magnitude. This permitted a comparison of induced neuroendocrine dysfunction as well as possibility that official conclusions might be

cancer rates along a continuum from low to lack of a specific measure of stress. in need of revision.

high exposure areas, all of which had a similar My personal experience, as well as study

potential for early detection of cancer. Reanalysis of the Cancer of the history and current practices of radia-

Although the accident occurred in 1979, inci- Incidence Study tion epidemiology, had led me to adopt a

dent cancer cases were identified for the period By the time the Columbia studies were skeptical attitude toward official assumptions

1975–1985, making it possible to evaluate the published, a lawsuit alleging health damages and logic. On a small scale, our collaborative

variation in cancer rates that existed in the area from radiation released in the TMI accident team engaged in the DOE Health and

both before and after the accident. This design had been under way for several years. Mortality Studies had been assured repeatedly

feature was important because cancer rates Approximately 2,000 plaintiffs argued that by industry and federal officials that no

show significant geographic variability, and it emissions of radioactive gases during the records existed that could account for a gap

Environmental Health Perspectives • VOLUME 111 | NUMBER 14 | November 2003 1811

Mini-Monograph | Wing

we had found in annual radiation dose others. At TMI most symptoms were reported is a mutagen related to most if not all malig-

records. However, shortly after publication of by people who had not been in public, some nancies, and because higher doses of radiation

our report that the existing workers’ badge of whom said they had not even heard about can lead to immune suppression and promo-

readings were related to their cancer mortality the accident at the time of their symptoms. tion of initiated cancers, we considered all can-

(Wing et al. 1991), over 14,000 radiation Thus, although it seemed plausible that some cer as one primary outcome. We examined

records that we had been seeking for more psychosomatic illness would have occurred at lung cancer because beta-emitting radioactive

than 2 years were provided to us (Wing et al. TMI, most reports did not fit the classic sce- gases in the accident plumes could have pro-

1994). On a larger scale, major radioactive nario of mass psychogenic illness. Nonhuman duced higher doses to the lung than to other

releases from nuclear weapons sites had been occurrences were obviously not psychogenic, organs. We considered leukemia, including

concealed from the public for decades although reports could have resulted from chronic lymphocytic leukemia (which had

(Thomas 2001); government-funded scien- increased vigilance or altered perception due been omitted in the Columbia reports) because

tists had conducted human radiation experi- to the accident. I did not attempt to validate studies of high-dose radiation have shown that

mentation without informed consent independently cases of unusual mortalities or leukemia is more radiation sensitive and

(Advisory Committee on Human Radiation abnormalities in animals and plants, and lack appears sooner after exposures than solid

Experiments 1995; McCally et al. 1994); risks of ongoing systematic surveillance precluded tumors. Although leukemia was a primary out-

to workers and the public had been withheld comparisons with baseline (preaccident) rates; come of the Columbia study, incidence among

because of concerns about litigation and loss however, the detail and quality of observation children and adults had been analyzed sepa-

of public support for the nuclear industry left me unable to dismiss these reports. rately, reducing an already small sample size.

(Advisory Committee on Human Radiation The Aamodts were interested in further More important, the childhood cancer analyses

Experiments 1995; Makhijani et al. 1995; examination of cancer incidence data assem- considered children conceived after the acci-

Office of Technology Assessment 1991; bled by Columbia. The Columbia investigators dent as exposed, potentially diluting any differ-

Sterling 1980); and epidemiologists who devi- had not acknowledged the possibility that ences in cancer incidence between exposed and

ated from status quo views about radiation community members’ symptoms might have unexposed children. Finally, we used baseline

and health had lost funding and suffered pro- been a sign of significant amounts of radiation. (preaccident) cancer rates rather than socioeco-

fessionally (Greenberg 1991; Lyon 1999; They assumed from the beginning that acci- nomic status variables (education, income, and

Morgan 1992; Stewart and Kneale 1991; dent doses were below average background lev- population density) as the primary method to

Thomas 2001; Wilkinson 1999). At the scale els, and they did not analyze data for the control for potentially confounding differences

of the scientific culture itself, there had long hilltop communities in the 1984 health survey. in other cancer risk factors between more- and

been a lack of nuanced scientific logic in the The plaintiffs’ legal team asked me to reanalyze less-exposed populations within the 10-mile

deference given by radiation epidemiologists the Columbia cancer incidence data to check area (Wing et al. 1997c).

to quantitative estimates of radiation risks whether study block boundaries had been con- Our analyses corrected for two problems

based on the world’s most studied radiation- structed in a way that might have obscured that had affected the Columbia results. One of

exposed population, the Japanese A-bomb clusters and to evaluate whether excess cancers their published analyses included duplicate

survivors (Stewart 2000; Wing et al. 1999). may have occurred in areas where there had case counts that we were able to eliminate

Given these facts, it seemed possible that been reports of acute symptoms and other from the reanalysis. In addition, the original

the full story about radiation releases, doses, unusual phenomena. preaccident period was defined as 1975–1979.

and health effects from the TMI accident had Although skepticism about the Columbia However, case ascertainment for 1975 was

yet to emerge. Although I had never previ- study was understandable, the study was, in incomplete. This led to an underestimation of

ously participated in litigation, I was aware principle, well designed, and I knew that the cancer incidence in the preaccident period and

that some of my colleagues had provided tes- investigators were highly respected. However, an overestimate of the increase in cancer fol-

timony for the defendants in radiation cases. recognizing that there were several potentially lowing the accident. To correct this problem,

Knowing that the defendants in the TMI case interesting omissions from the published we redefined the preaccident period as

had many experienced experts at their dis- results, I agreed to conduct reanalyses if the 1976–1979 (Wing et al. 1997b, 1997c).

posal and that it was difficult for plaintiffs to data could be released through the court. The We found positive relationships between

find help, I agreed to examine epidemiologic court decided not to disclose the locations of accident dose estimates and cancer rates for all

data related to the case. residence of cancer cases on the grounds that three categories of cancer. The slope of the

One of the first tasks I undertook was a this would violate patient confidentiality; dose–response estimates was largest for

review of published studies on “mass hysteria,” however, the court did direct that we be leukemia, intermediate for lung cancer, and

a medical term for outbreaks of psychogenic given, for each study block, a) dose estimates, smallest for all cancers. Estimates were larger

illness with no physical etiology (Brodsky b) numbers of cases of specific types of cancer, for cancers that occurred in 1984–1985

1988; Donnell et al. 1989; Faust and Brilliant c) population counts, and d) average levels of (a 5-year lag) than for cancers that occurred in

1981; Hefez 1985; Simon et al. 1990; Small education, income, and population density. 1981–1985 (a 2-year lag), and they were larger

and Borus 1987). There is no doubt that the Estimates of doses from gamma radiation for when statistical adjustments were made for

TMI accident had created high stress, even each study block were given in relative units differences in socioeconomic status between

panic nor is there any doubt that stress can that ranged from 0 to 1,666. The values were areas of low and high dose. Lung cancer

produce physical symptoms. Although some not assigned a unit of measurement (e.g., Sv showed the most consistent dose–response

symptoms reported by TMI area residents— or rem) but were calculated on a ratio scale relationship across levels of dose. Figure 3

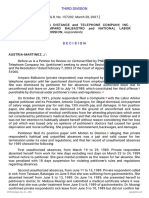

nausea and vomiting, for instance—are com- such that a value of 10 was twice that of 5, shows dose estimates in relation to lung cancer

monly reported in the literature on outbreaks and a value of 1,000 was twice that of 500 rates, based on the 440 cases diagnosed in the

of psychogenic symptoms, other symptoms, (Hatch et al. 1990). 10-mile area during 1981–1985, adjusted for

most notably metallic taste and hair loss, are We considered different primary hypotheses preaccident variation in lung cancer incidence,

not. Furthermore, one hallmark of mass and used a primary analytical method different but not for socioeconomic status. The height

psychogenic illness is that it occurs in public from the one used by the original investigators of the bars represents the difference between

places where people witness the symptoms of (Wing et al. 1997c). Because ionizing radiation the observed numbers of cases at each dose

1812 VOLUME 111 | NUMBER 14 | November 2003 • Environmental Health Perspectives

Mini-Monograph | Objectivity and ethics in science

level and the number that would have hearing. The court’s evaluations of each of The court next considered whether there

occurred if each area had experienced the aver- the criteria are summarized in Table 1. were standards controlling the operation of

age lung cancer rates of the 10-mile area Defendants did not challenge the first our technique. Although seemingly impressed

population as a whole. Daubert criterion, and the judge found that with our quality control procedures, which

“the cancer incidence study methodology led us to identify biases associated with

Epidemiologic Evidence consists of a testable hypothesis” (TMI double-counting of cancer cases and an

in Court Litigation Cases Consolidated II 1996a). undercount in 1975, the court found fault

Scientific rigor and objectivity have a special Under the second criterion the court with what the defendants cited as our failure

value in courts of law, which specify rules for considered whether the methodology used to to conduct analyses of incidence of “the types

deciding what constitutes scientific evidence produce the results had been peer reviewed. of cancers known to be radiogenic” and of

and whether scientific evidence is reliable and The Columbia team’s papers, and therefore cancer deaths. Our failure to conduct these

therefore admissible at trial. Since 1993, the the basic study design and data collection, had analyses balanced against the quality control

standards for admissibility of scientific evi- been peer reviewed and was recognized by the procedures in the court’s evaluation of our

dence in federal courts have been based on court. Part of our study was a replication of standards of control. The court ruled, “This

the U.S. Supreme Court’s ruling in Daubert the original analyses showing that we could factor will not weigh against the admission of

v. Merrell Dow Pharmaceuticals, Inc. (1993). apply the same statistical methods to produce the proffered testimony” (TMI Litigation

Judges decide whether expert testimony can the same results. In other analyses we applied Cases Consolidated II 1996a).

be considered in litigation based on criteria the same statistical method to corrected data

expounded in Daubert, other cases, and in using different controlling (or adjustment) fac-

the Federal Rules of Evidence: tors corresponding to the before–after design

1) there is a testable hypothesis of the study. Despite these facts, the judge,

2) the methodology has been subjected to noting that “Aside from Wing’s ‘unadorned

peer review assertions’ that the methodologies have been Three Mile

3) the results have an acceptable “known or subject to peer review, Plaintiffs have pre- Island

potential rate of error” sented no evidence of this fact,” ruled, “This

4) standards are used to control the reliabil- factor will weigh against the admission of the

ity of the methodology proffered testimony” (TMI Litigation Cases

5) there is adequate support and acceptance of Consolidated II 1996a).

the methodology by a scientific community The court made two rulings on the issue of

6) the testimony relies on facts or data used the third criterion, the known or potential rate

by other experts in the discipline of error (TMI Litigation Cases Consolidated II

7) the expert’s professional qualifications are 1996a, 1996b). Because of a lack of under-

observed and expected cases

Percent difference between

adequate standing of how to interpret the standard 150

8) the methods have the potential to be used errors of the dose–response regression coeffi- 100

for purposes outside the courtroom cients provided in our report, the court initially 50

(Merwin et al. 2001) deferred its decision on the “rate of error.” 0

Exclusion of evidence that does not meet However, the first ruling cited defendants’ –50

these standards is intended to protect juries argument that the findings could have been

from being exposed to untrustworthy scientific “ascribable to chance as well as to any real asso-

0

10

00

66

0–

–5

20

40

80

1–

–1

1,6

testimony. ciation with accident emissions” on the basis of

0–

0–

0–

10

50

0–

10

20

40

80

Our reanalysis of the TMI cancer 95% confidence limits around our estimates of Radiation doses resulting from the 1979

incidence data was submitted to the District dose response for all cancer (in the models that nuclear accident (relative units of radiation)

Court for the Middle District of Pennsylvania omitted socioeconomic status) and leukemia Figure 3. Radiation emissions and incidence of lung

in support of the plaintiff’s allegations. My (in models with and without socioeconomic cancer, 1981–1985, in the TMI 10-mile area. Figure

testimony about relationships between esti- status) (Wing et al. 1997c), which, defendants adapted from Dalrymple (1997).

mated doses and cancer incidence in the noted, included the null value of no effect

10-mile area was being used as evidence that (TMI Litigation Cases Consolidated II Table 1. Consideration of admissibility of evidence

significant exposure had occurred, not as evi- 1996b). The court then cited defendants’ from the reanalyses of cancer incidence in the TMI

dence that a particular plaintiff’s cancer was experts as claiming that lung cancer “has never 10-mile area, District Court for the Middle District

caused by radiation. The defendants argued been identified with radiation exposure as an of Pennsylvania.

that our study was unreliable and that the isolated effect,” implying that lung cancer was Weight in consideration

judge should exclude it from trial on grounds the only type of cancer that showed a dose Criterion for admission of admission

that it did not satisfy the Daubert criteria. effect, and also cited their claim that there was 1. Testable hypothesis For

The court considered the admissibility of not sufficient latency for lung cancer to appear 2. Peer-reviewed methodology Against

our reanalysis based on our report describing after the accident. In its second ruling on the 3. Known or potential rate Neither for

the study’s hypotheses, design, materials, ana- rate of error, the court accepted the defendants’ of error nor against

lytical methods, results, and conclusions; claims that minimum latency for lung cancer 4. Standards are used to Neither for

transcripts of depositions conducted by was known to be 10 years (TMI Litigation control reliability nor against

5. Support and acceptance of Neither for

defense attorneys; the defendants’ motions Cases Consolidated II 1996b). Below I discuss methodology nor against

in limine (to suppress); plaintiffs’ responses to this juxtaposition of argument about statistical 6. Relies on facts or data used Against

defendants; reports on our study prepared by testing and the state of knowledge about cancer by other experts

defendants’ experts; my affidavits responding latency and radiosensitivity. However, in its 7. Professional qualifications For

to questions from the judge; and testimony second ruling, the court did not exclude evi- 8. Potential for use outside

by the defense experts and me at an in limine dence from our study on rate of error grounds. the courtroom For

Environmental Health Perspectives • VOLUME 111 | NUMBER 14 | November 2003 1813

Mini-Monograph | Wing

On the fifth criterion, the court found Testable hypotheses: collision of evidence of its outcome (health effects), constitute a

that the principle of reanalysis was generally and assumptions. The court found that our manipulation of research that was possible, in

accepted, and it attributed to defendants methodology did involve a testable hypothesis. part, because of years of investigative compla-

the claim that “the statistical technique Ironically, we argued that although the cency brought on by entrenched assumptions

employed by Wing is generally accepted in Columbia investigators designed a study with that precluded even consideration of the pos-

the scientific community” (TMI Litigation a testable hypothesis, they were unable to test sibility of high releases. The requirement of

Cases Consolidated II 1996a). The latter it because of their assumptions. A testable prior concurrence by lawyers for the industry

point is ironic given the court’s decision that hypothesis requires that evidence of the effect suggests that the industry’s image and liability

lack of peer review of the methodology be interpretable as supporting the hypothesis. were more important than accuracy and

weighed against admissibility. However, the Support should be strengthened to the extent full disclosure.

court agreed with defendants that the that the design and conduct of the study help Peer review: normal science. Under

methodology was problematic “because it rule out alternative explanations for the find- Daubert, the court considers peer review of

produces conclusions at odds with what is ings. However, the Columbia investigators the methodology to be a factor in the admissi-

generally known and accepted about cancer clearly stated that the accident doses were bility of evidence. The court’s decision that

latency periods” (TMI Litigation Cases known to be too low to produce the effects lack of peer review weighed against admissi-

Consolidated II 1996a). This factor, like the being hypothesized; the increased risk of can- bility of our study was curious and internally

standards of control, did not weigh against cer at the assumed maximum dose to a mem- contradictory for reasons noted above. In

admission of the testimony. ber of the public would have been less than principle, peer review is one of several

Regarding our reliance on facts or data one-half of 1% according to standard assump- Daubert criteria that gives preference to nor-

used by other experts, the court found, “In tions, clearly an excess too small to be mative scientific views under the debatable

many ways Wing’s cancer incidence study detectable by epidemiologic methods (Wing et assumption that widely held beliefs are more

closely resembles a standard and reliable epi- al. 1997c). We argued that a follow-up study reliable. Although peer review may catch

demiologic reanalysis. Yet in one important of cancer mortality among adults in the TMI obvious flaws or poor writing, it cannot

way it does not. Wing’s reanalysis produces 5-mile area (Talbott et al. 2000, 2003) suf- ensure that findings are correct, or even that

no conclusive findings” (TMI Litigation fered from the same logical flaw: assumptions research is not fraudulent (Broad and Wade

Cases Consolidated II 1996a). This lack of of low doses clearly precluded an interpreta- 1982). In areas where scientific research, pro-

conclusiveness, according to the court, tion of the positive dose–response relation- fessional meetings, fellowships, and journals

weighed against admission of our study. The ships as supportive of the hypothesis under are funded through organizations with inter-

court found that criteria seven and eight, pro- investigation (Wing and Richardson 2001). ests in an established perspective, peer review

fessional qualifications and nonjudicial uses, If the testability of a hypothesis depends on by orthodox scientists may lead to rejection of

weighed in favor of admissibility. assumptions as well as methodology, then an studies whose results challenge established

Deferring only the final decision on rate evaluation of the quality of a study must assumptions, even if their methodology is

of error, which eventually was decided in address the logic of key assumptions as well as appropriate (Nussbaum 1998; Nussbaum and

favor of admissibility, the court weighed all the methodology. The assumption that the Köhnlein 1994).

the Daubert criteria to decide on admissibility cancer risk of the maximally exposed person Known or potential rate of error. This

of the reanalysis (TMI Litigation Cases would increase by only 0.5% was supported by criterion of admissibility is intended to recog-

Consolidated II 1996a). The ruling found official reports. We addressed a testable nize that scientific studies make measurements

our results on all cancer and leukemia to be hypothesis only because we considered the pos- to quantify phenomena, and that the accuracy

admissible at trial. The lung cancer findings, sibility that these reports could be wrong. of these measurements is an important crite-

including the regression analysis summarizing Without that possibility, there would be no rion. For example, upon repeated measure-

the dose response shown in Figure 3, were testable hypothesis. Our association with plain- ments of identical samples, variability in a

excluded based on defendants’ arguments that tiffs in the litigation introduced us to critical scale, assay, or other measurement device pro-

radiation-induced lung cancer has a minimum reevaluations of radiation monitoring, detailed duces a distribution of results similar to the

latency of 10 years, and that the analyses were case reports of symptoms (Aamodt and patterns of card combinations produced by

therefore irrelevant to the case. Aamodt 1984; Molholt 1985), biodosimetric well-shuffled decks. In the case of epidemio-

studies of persons who reported symptoms at logic studies of exposure–disease relationships,

Discussion the time of the accident (Shevchenko 1996; the courts have taken statistical parameters

The TMI cancer incidence studies were Shevchenko and Snigiryova 1996), and meteo- such as standard errors, confidence limits, test

conducted in the context of conflict between rologic and environmental analyses (Field et al. statistics, and p-values to be indicators of this

residents who believed they had been injured 1981; Steinacker and Vergeiner 2002; Wahlen rate of error.

and officials who denied that such injuries et al. 1980), as well as the court order that Our report provided information on

were possible, as well as conflicts between directed calculation of radiation doses for the sample size, goodness of fit, and standard

scientists over the magnitude of radiation Columbia study. The order prohibited “upper errors of regression coefficients rather than

releases, the state of knowledge about radia- limit or worst case estimates of releases of p-values or 95% confidence intervals.

tion-induced cancer, and the meaning of evi- radioactivity or population doses . . . [unless] Although confidence limits and p-values can

dence produced by the TMI cancer incidence such estimates would lead to a mathematical be easily calculated from standard errors and

studies. In the next section, I intend to show projection of less than 0.01 health effects,” and likelihood ratio tests, they are commonly mis-

how the objectivity, rigor, and ethics of further specified that “a technical analyst . . . interpreted as reflecting a process of random-

science can be increased by analyzing the designated by counsel for the Pools [nuclear ization in which there is an a priori probability

influence of these conflicts on research industry insurers] concur on the nature and distribution of results from repeated unbiased,

assumptions, methods, and conclusions. I scope of the [dosimetry] projects” (Three Mile well-controlled experiments distributed

begin with a discussion of the court’s reason- Island Litigation 1986). These court-imposed around the true parameter (Greenland 1990).

ing on the admissibility of the reanalysis, restrictions, which conditioned the input of the In the absence of randomization or random

focusing on Daubert criteria 1–3 and 5. investigation (release estimates) on projections sampling in the TMI cancer incidence study

1814 VOLUME 111 | NUMBER 14 | November 2003 • Environmental Health Perspectives

Mini-Monograph | Objectivity and ethics in science

of a total population, I argued that statistical In its second ruling on the rate of error analyzed—can discourage scientists from

evidence should be evaluated issue, the court quoted from the affidavit I humility about the scientific enterprise as well

in the context of the sensitivity of the findings to prepared on this issue in which I attempted to as deeper mechanistic analysis (Gigerenzer

changes in assumptions and data, coherence of the explain why the strict application of statistical et al. 1989). In the case of environmental

evidence with other knowledge, the magnitude of tests being advocated by defendants was health research, this may discourage the test-

associations, their consistency across groups, and increasingly recognized as inappropriate: ing of hypotheses or use of methods with the

temporal relationships of exposure and effect. greatest potential to implicate institutions

(Wing 1995) Abuse of significance testing in epidemiological

research is now widely appreciated and discussed. that permit or produce pollution. An under-

Although the court recognized literature The problem is clearly recognized by one of the standing of how chance as a tool has been

recommending that the admissibility of evi- defense’s experts, K. Rothman, who wrote in an conflated with chance as an explanatory force

dence should not be determined solely on the editorial introducing a paper on logical problems of nature could help to improve the practice

with statistical significance testing, “In a century in

basis of a significant p-value or a confidence and applications of science. However, even

which science has revealed that molecules and

interval excluding the null value of no statistical atoms are mostly unoccupied space and that matter without a detailed understanding of that

association, defendants specifically made that is energy anyway, we should be accustomed to hav- process, it is clear that current practice,

argument, and the court was uncertain about ing the substance of our scientific foundations dis- although normative science, is inconsistent

how to judge my less mathematical approach. solve into emptiness. In this issue [of the journal], and illogical. Chance may have created an

The problem, according the judge, was that, Greenland perforates the foundations of statistical empire in the world of science (Hacking

interpretations used by epidemiologists in just this

“To the extent that the results are more likely 1990), but its emperor has no clothes.

way” (Rothman 1990). The problems with signifi-

the product of random error than a true causal cance testing noted in the paper by Greenland Basis of assumptions about radiogenic

relationship, the probative value of the study (Greenland 1990) have been recognized for some cancers and cancer latency. The court’s ruling

necessarily diminishes” (TMI Litigation Cases time, but have been ignored in the interests of pre- that our lung cancer findings were inadmissi-

Consolidated II 1996a). I argued that random serving a simple if fallacious method that was ble at trial was based on defendants’ claims

error was not the issue because randomization believed to result in the separation of conclusive, that a) only lung cancer was statistically sig-

causal associations from those that are inconclusive

had not been employed. nificantly related to accident dose estimates,

or spurious. That method is the determination of

The court’s interpretation reflects the statistical significance of a finding. As noted by b) lung cancer has never been found as the

confusion between the use of chance as a tool Rothman, “conventional statistics [p-values and sole effect of radiation, and c) radiogenic lung

and the idea of chance as a force of nature. confidence limits] have a strict interpretability in cancer is known to have a minimum latency

Chance as a tool is familiar in card games, experiments with random assignment of exposures. of 10 years. These arguments, repeated in the

random sampling, and random allocation, The results of those experiments are nearly always court’s rulings under several Daubert criteria,

dressed in the same statistical garb that was devel-

and can be created only by complete control especially the fifth, imply that dose–response

oped for and is applied to experimental studies.

over the materials being manipulated: cards, Greenland shows us that, despite our reliance on relationships for leukemia and all cancer

sampled units, or patients assigned to treat- conventional statistics for interpreting our non- resulted from random error, and that the

ment. Under these conditions, probabilities of experimental results, there is no basis for the inter- results for lung cancer must be due to some

particular occurrences are defined because the pretations usually given to these statistics in other error because they could not occur as a

materials can be ordered or mixed through a nonexperimental settings.” [emphasis added]. This is result of the hypothesized cause. Although the

because, in the absence of randomization of expo-

process (shuffling, randomization) that has leukemia dose–response coefficients, based on

sure in a fair experiment, it is not possible to distin-

been constructed to eliminate systematic guish the extent to which test statistics reflect bias 75 cases, were less precise than the lung can-

influence on the order or assignment. or the exposure under investigation. (TMI cer estimates, they were roughly 40% larger in

Following the use of chance as a tool, long- Litigation Cases Consolidated II 1996b) magnitude, which would be consistent with

run probabilities are determined if there is no studies showing steeper relationships for

bias in the conduct of the game or research. That a normative scientific practice used leukemia than for solid tumors after high-

Statistical testing in observational settings, to distinguish causal from noncausal relation- dose radiation. Dose–response coefficients for

including most epidemiology, occurs in ships—central not only to science but to its all cancers were more precise but smaller in

studies of aspects of the real world, such as social and legal applications—could “dissolve magnitude, which would be consistent with

dose–response relationships, in which there into emptiness” should be disconcerting to lower doses to organs other than the lung

have been no randomization and no random those who count on science for objective and (Wing et al. 1997a, 1997c).

sampling. Under these conditions there is no a rational knowledge. Critical analysis of normal Our interest in lung cancer was based on

priori probability distribution because chance scientific practice can help to identify such the presence of radioactive gases, primarily

has not been used as a tool. Therefore, chance emptiness before serious mistakes are made. In xenon-133 and krypton-85, in the accident

introduced through randomization is not a the TMI reanalysis we chose a contextual set plumes. In addition to penetrating gamma

possible explanation of a result. What, then, do of criteria to evaluate quantitative evidence radiation, these gases emit beta radiation,

researchers (or courts) mean when they because we did not believe that results could which has low penetration and therefore

conclude from statistical tests that results are be a product of random error unless random- would have delivered direct doses selectively

likely due to chance? They should not mean ization had been introduced by design. If our to exposed skin and respiratory tissues, which

that some unknown factor is the cause, because primary quest had been small p-values, we would be consistent with reports of erythema

other causes that create (or mask) the appear- would have used one-tailed tests (because our and putative impacts on plants as well as ele-

ance of an association between exposures and hypothesis was one-directional), emphasized vations in lung cancer. However, even if lung

outcomes are referred to as confounders results adjusted for socioeconomic status, and doses were substantial, no cancer effect would

(whether or not they have been measured). analyzed log-transformed doses, which, as be seen in the incidence study if radiogenic

Rather, the concept of chance in observational noted by Mangano (Mangano 1997), would lung cancer has a minimum latency of

research has been confused with its original have better fit the data and produced smaller 10 years.

interpretation in randomized studies: it is p-values. There have been no epidemiologic studies

treated as a force of nature that functions as an Invocation of chance as a force of of the exposure of human populations to

alternative explanation to specific causes. nature—a cause incapable of being further radioactive xenon and krypton gases.

Environmental Health Perspectives • VOLUME 111 | NUMBER 14 | November 2003 1815

Mini-Monograph | Wing

Consequently, assumptions about the types those which are caused by radiation exposure these situations as examples of environmental

and timing of cancers that could result must were due to stress. Studies were designed to injustice. Many rural people living near TMI

be based on inference from studies of other quantify health effects of stress in general, and had modest levels of formal schooling and lit-

types of ionizing radiation. Defendants specifically as an alternative explanation to tle experience in being assertive with govern-

argued that the study of Japanese A-bomb radiation-induced cancer increases following ment and industry officials. Those that spoke

survivors, upon which official estimates of the accident. An editorial commenting on the out about their experiences of physical prob-

radiation risks and latency have been based, paper by Hatch et al. (1991) on stress and can- lems from the accident endured ridicule. The

proved that lung cancer has a 10-year mini- cer suggested that the stress–cancer link might Aamodts were able to influence the TMI

mum latency. In response, we noted that ion- be used as grounds for not disclosing accidents Public Health Fund’s sponsored research on

izing radiation can act as a promoter as well as to the public because the resulting stress would physical impacts of the accident by initiating

an initiator of cancer (Doll 1978); that high injure people (Janerich 1991). When radiation their own survey, researching government

doses can suppress immune function, which is exposures were studied, discussion of findings records, and petitioning the NRC. Other resi-

associated with the appearance of secondary focused on reasons why radiation effects may dents who lived within the 10-mile area also

tumors within 2 years of radiotherapy have been overestimated or spurious, ignoring conducted surveys, constructed disease maps,

(Appelbaum 1993); and that latencies of less plausible reasons why they may well have been and documented damage to plants and ani-

than 5 years have been observed for miners underestimated (Hatch et al. 1990; Talbott et mals (Osborn 1996; Three Mile Island Alert

exposed to radon (Hornung and Meinhardt al. 2000; Wing and Richardson 2001). The 1999). However, when health studies were

1987). A recent study of lung cancer among Columbia investigators chose not to discuss undertaken through official channels, citizens

uranium miners found the best estimate of dose misclassification and migration, for exam- who believed they had been affected by acci-

minimum latency to be less than 1 year ple, as reasons to expect underestimation of dent emissions and their supporters were not

(Langholz et al. 1999). radiation effects (Hatch et al. 1990). In fact, included in the framing of questions, study

Epidemiologists often remain skeptical of they planned to consider the possibility of con- design, analysis, interpretation, or communi-

estimates of dose–response relationships founding bias in estimates of dose response cation of results. The studies themselves were

because of questions about possible con- only in the event that they found a positive funded by the nuclear industry and con-

founding and measurement error. In the area radiation–cancer relationship (Susser 1997), ducted under court-ordered constraints, and a

of radiation health effects, however, the despite the fact that such bias could also mask priori assumptions precluded interpretation

A-bomb survivor studies are widely used for a true effect. The lack of attention to these of observations as support for the hypothesis

risk estimation and have long functioned as a standard interpretive issues can be understood under investigation.

“gold standard” for judging other epidemio- in terms of the key role that assumptions play The naïve approach to objectivity,

logic evidence (BEIR V 1990). The A-bomb in evaluating the meaning of results (Wing represented in the Daubert criteria, contends

studies have this status despite being based on et al. 1997b). that scientists can produce unbiased evidence

a select group of survivors that had to resist Despite differences in results between the by standing apart from legal conflicts and

radiation, blast, and the aftermath of war to Columbia studies and ours, both found evi- adhering to normative science. The problem

enter the study, and whose radiation doses dence of impacts of the accident on cancer with this position is that scientific questions

were not measured but calculated based on incidence. However, the evidence led us to and the details of specific working hypotheses

a) estimates of radiation releases that have different conclusions regarding both cause emerge from conflicts, which also influence the

been repeatedly revised, and b) interviews and biological mechanism. The Columbia assumptions that frame methodologies used to

whose accuracy depended on the survivors’ group concluded that the evidence suggested produce evidence and interpretations of the

memories and their trust of researchers con- stress as a cause, and stress-induced immune meaning of evidence. This process occurs at

nected with the U.S. military occupation system depression as a mechanism. We con- various scales, from decisions about how much

forces (Lindee 1994; Stewart 2000; Wing cluded that the evidence suggested radiation to trust conflicting assertions regarding a spe-

et al. 1999). The status of the A-bomb studies as a cause, and promotion of cancer through cific event like the TMI accident, to the role of

as a gold standard has shaped the normative late-stage “hits” in a multistage process of the A-bomb studies as a gold standard for eval-

scientific culture, including peer review, carcinogenesis, as well as radiation-induced uating evidence, to widespread conventions

research funding, and dismissal of conflicting immune system depression, as mechanisms. such as the confusion between chance as a tool

evidence from other populations (Nussbaum Keller described an analogous situation in and chance as a force of nature. Although sci-

and Köhnlein 1994; Wing et al. 1999). which experimental observations on genetic ence has strong rationalist traditions, it has

Critical analysis of the evolution of radiation mutations were redescribed and reinterpreted also been shaped by perspectives of dominant

epidemiology within the context of the mili- to produce different conclusions about causes gender, race, and class groups, excluding per-

tary, medical, and industrial uses of ionizing and mechanisms (Keller 1992). spectives of groups with less power (Harding

radiation can help scientists reevaluate the 1991; Holtzman 1981; Hubbard 1990; Levins

A-bomb studies more objectively. Such an Conclusion: The Ethics of 1979; Levins and Lewontin 1985). Pretending

approach would help to increase the explana- Strong Objectivity that there are no assumptions embedded in

tory capacity of radiation health science and Conflicts over responsibility for damage to scientific methodology conceals and reinforces

improve its applications in the courts, com- health and the environment are increasingly existing inequalities.

pensation programs, and public education common. They often involve disputes Strong objectivity demands that scientists

(Wing and Richardson 2002). between actors, such as industries and govern- critically evaluate how the knowledge they cre-

Radiation versus stress as causal ments, with the ability to make large impacts ate is shaped at every point by historical social

explanations. From their inception, epidemio- as well as sponsor research on those impacts, forces. Strong objectivity is therefore not a static

logic studies of the TMI accident focused on and communities that are most directly feature of scientific knowledge that, once

stress. Although this was not specifically an affected but that have little political power or attained, becomes a property of that knowl-

issue in the court, it is central to the epidemiol- capacity to conduct research to document edge. It is an evolving process that is never fin-

ogy and public relations of the accident. their exposures or health conditions (Wing ished, like scientific inquiry itself. Scientists

Citizens were told that symptoms similar to 2002). Affected communities may experience should be trained to engage in careful reflection

1816 VOLUME 111 | NUMBER 14 | November 2003 • Environmental Health Perspectives

Mini-Monograph | Objectivity and ethics in science

about how the history of their discipline has three-year-old children living near Three Mile Island: a com- Houts PS, Goldhaber MK. 1981. Psychological and social

affected their hypotheses, assumptions, and parative analysis. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 27:489–498. effects on the population surrounding Three Mile Island

Dalrymple M. 1997. Science on the firing line. Endeavors:The after the nuclear accident on March 28, 1979. In: Energy,

tools, and how their work, like the work of oth- University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill 14(Fall):12–13. Environment and the Economy (Majumdar S, ed).

ers before them, is shaped by contemporary Daubert v. Merrell Dow Pharmaceuticals, Inc. 1993. Case No. Philadelphia:Pennsylvania Academy of Sciences, 151–164.

forces (Armstrong 1999). This is essential as 509 U.S. 579, U.S. Supreme Court, Washington, DC. Houts PS, Tokuhata GK, Bratz J, Bartholomew MJ, Sheffer KW.

Davidson LM, Fleming R, Baum A. 1987. Chronic stress, cate- 1991. Effect of pregnancy during TMI crisis on mothers’

careful measurement and analysis for producing cholamines, and sleep disturbance at Three Mile Island. mental health and their child’s development. Am J Public

an objective science that will be maximally rig- J Hum Stress 13:75–83. Health 81:384–386.

orous, rational, reliable in courts of law, and Del Tredici R. 1980. The People of Three Mile Island. San Hubbard R. 1990. The Politics of Women’s Biology. New

Francisco, CA:Sierra Club. Brunswick, NJ:Rutgers University Press.

useful for improving the world. Strong objectiv- Dew MA, Bromet EJ. 1993. Predictors of temporal patterns of Janerich DT. 1991. Can stress cause cancer? [Editorial]. Am J

ity is needed, not only for good science, but for psychiatric distress during 10 years following the nuclear Public Health 81:687–688.

ethical conduct of research. accident at Three Mile Island. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Keller E. 1992. Between language and science: the question of

Epidemiol 28:49–55. directed mutation in molecular genetics. Perspect Biol

Dew MA, Bromet EJ, Schulberg HC. 1987a. A comparative Med 35:292–306.

Postscript analysis of two community stressors’ long-term mental ———. 1995. Science and its critics. Academe 81:10–15.

In December 1999, after summary dismissal health effects. Am J Community Psychol 15:167–184. Kuhn T. 1970. The Structure of Scientific Revolutions.

Dew MA, Bromet EJ, Schulberg HC, Dunn LO, Parkinson DK. Chicago:University of Chicago Press.

of the TMI case by the District Court for the 1987b. Mental health effects of the Three Mile Island Langholz B, Thomas D, Xiang A, Stram D. 1999. Latency analy-

Middle District of Pennsylvania, the U.S. nuclear reactor restart. Am J Psychiatry 144:1074–1077. sis in epidemiologic studies of occupational exposures:

Third Circuit Court of Appeals found that Doll R. 1978. An epidemiological perspective of the biology of application to the Colorado Plateau uranium miners

the district court had erred in excluding our cancer. Cancer Res 38:3573–3583. cohort. Am J Ind Med 35:246–256.

Donnell HD, Bagby JR, Harmon RG, Crellin JR, Chaski HC, Levins R 1979. Class Science and Scientific Truth. The New York

lung cancer findings (although the appeals Bright MF, et al. 1989. Report of an illness outbreak at the Marxist School Available: http://csf.colorado.edu/gimenez/

court also ruled that the lung cancer findings Harry S. Truman state office building. Am J Epidemiol papers/Class-Science.html [accessed 20 May 2003].

would not change the outcome of the case). 129:550–558. Levins R, Lewontin RC. 1985. The Dialectical Biologist.

Fabrikant JI. 1983. The effects of the accident at Three Mile Cambridge, MA:Harvard University Press.

In December 2002, the circuit court declined Island on the mental health and behavioral responses of Lindee MS. 1994. Suffering made real: American science and

to hear an appeal of Judge Rambo’s second the general population and nuclear workers. Health Phys the survivors at Hiroshima. Chicago:University of Chicago

ruling granting summary dismissal. Attorneys 45:579–586. Press.

Faust HS, Brilliant LB. 1981. Is the diagnosis of “mass hysteria” Lyon JL. 1999. Nuclear weapons testing and research efforts to

representing 1,990 remaining plaintiffs in the an excuse for incomplete investigation of low-level envi- evaluate health effects on exposed populations in the

TMI case declared they would take no further ronmental contamination? J Occup Med 23:22–26. United States. Epidemiology 10:557–560.

legal action (Associated Press 2002). Field R, Field E, Zegers D, Steucek G. 1981. Iodine-131 in thy- Macleod GK. 1981. Some public health lessons from Three Mile

roids of the meadow vole (Microtus Pennsylvanicus) in the Island: a case study in chaos. Ambio 10:18–23.

vicinity of the Three Mile Island nuclear generating plant. Makhijani A, Hu H, Yih K. 1995. Nuclear Wastelands: A Global

REFERENCES Health Phys 41:297–301. Guide to Nuclear Weapons Production and Its Health and

Gatchel RJ, Schaeffer MA, Baum A. 1985. A psychophysiological Environmental Effects. Cambridge, MA:MIT Press.

Aamodt M, Aamodt N. 1984. Petitioners v. U.S. Nuclear field study of stress at Three Mile Island. Psychophysiology Mangano JJ. 1997. Low-level radiation harmed humans near

Regulatory Commission. Aamodt motions for investigation 22:175–181. Three Mile Island. Environ Health Perspect 105:786–787.

of licensee’s reports of radioactive releases during the ini- Gigerenzer G, Swijtink Z, Porter T, Daston L, Beatty J, Kruger L. McCally M, Cassel C, Kimball DG. 1994. U.S. government-spon-

tial days of the TMI-2 accident and postponement of 1989. The Empire of Chance: How Probability Changed sored radiation research on humans, 1945–1975. Med Glob

restart decision pending resolution of this investigation. Science and Everyday Life. New York:Cambridge Surviv 1:4–17.

Docket Number 50-289. Administrative Court, Washington, University Press. McKinnon W, Weisse CS, Reynolds CP, Bowles CA, Baum A.

DC, 21 June. Goldhaber MK, Houts PS, DiSabella R. 1983a. Moving after the 1989. Chronic stress, leukocyte subpopulations, and

Advisory Committee on Human Radiation Experiments. 1995. Final crisis: a prospective study of Three Mile Island area popu- humoral response to latent viruses. Health Psychol

Report, Advisory Committee on Human Radiation Experiments. lation mobility. Environ Behav 15:93–120. 8:389–402.

Washington, DC:U.S. Government Printing Office. Goldhaber MK, Staub SL, Tokuhata GK. 1983b. Spontaneous Merwin S, Moeller D, Kennedy W, Moeller M. 2001. Application

Appelbaum F. 1993. The influence of total dose, fractionation, abortions after the Three Mile Island nuclear accident: a of the Supreme Court’s Daubert criteria in radiation litiga-

dose rate, and distribution of total body irradiation on bone life table analysis. Am J Public Health 73:752–759. tion. Health Phys 81:670–677.

marrow transplantation. Semin Oncol 20:3–10. Goldhaber MK, Tokuhata GK, Digon E, Caldwell GG, Stein GF, Molholt B. 1985. Summary of acute symptoms by TMI area resi-

Armstrong D. 1999. “Controversies in epidemiology”, teaching Lutz G, et al. 1983c. The Three Mile Island Population dents during accident. In: Proceedings of the Workshop

causality in context at the University at Albany, School of Registry. Public Health Rep 98:603–609. on Three Mile Island Dosimetry, Vol 2. Academy of Natural

Public Health. Scand J Public Health 2:81–84. Gray M, Rosen I. 1982. The Warning: Accident at Three Mile Sciences, 12–13 November 1984 Philadelphia, PA:TMI

Associated Press 2002. Plaintiffs end action in TMI lawsuit. Island. New York:W.W. Norton. Public Health Fund, A109–111.

Available: http://www.philly.com/mld/inquirer/news/ Greenberg M. 1991. The evolution of attitudes to the human Morgan KZ. 1992. Health physics: its development, successes,

local/4826524.htm [accessed 16 May 2003]. hazards of ionizing radiation and to its investigators. Am J failures, and eccentricities. Am J Ind Med 22:125–133.

Baum A. 1990. Stress, intrusive imagery, and chronic distress. Ind Med 20:717–721. NRC. 1979a. Population Dose and Health Impact of the Accident

Health Psychol 9:653–675. Greenland S. 1990. Randomization, statistics, and causal infer- at the Three Mile Island Nuclear Station. Washington,

Baum A, Cohen L, Hall M. 1993. Control and intrusive memories as ence. Epidemiology 1:421–429. DC:U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission.

possible determinants of chronic stress. Psychosom Med Gur D, Good WF, Tokuhata GK, Goldhaber MK, Rosen JC, Rao ———. 1979b. Investigation into the March 28,1979 Three Mile

55:274–286. GR, et al. 1983. Radiation dose assignment to individuals Island Accident by Office of Inspection and Enforcement.

Baum A, Gatchel RJ, Schaeffer MA. 1983. Emotional, behavioral, residing near the Three Mile Island nuclear station. Proc Washington, DC:U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission.

and physiological effects of chronic stress at Three Mile PA Acad Sci 57:99–102. Nussbaum RH. 1998. The linear no-threshold dose-effect rela-

Island. J Consult Clin Psychol 51:565–572. Hacking I. 1990. The Taming of Chance. New York:Cambridge tion: Is it relevant to radiation protection? Med Phys

BEIR V. 1990. National Research Council, Committee on the University Press. 25:291–299.

Biological Effects of Ionizing Radiation (BEIR V), Health Harding S. 1991. Whose Science? Whose Knowledge? Ithaca, Nussbaum R, Köhnlein W. 1994. Inconsistencies and open

Effects of Exposure to Low Levels of Ionizing Radiation. NY:Cornell University Press. questions regarding low-dose health effects of ionizing

Washington, DC:National Academy Press. Hatch MC, Beyea J, Nieves JW, Susser M. 1990. Cancer near radiation. Environ Health Perspect 102:656–667.

Beyea J. 1985. Three Mile Island—six years later. J Nucl Med the Three Mile Island nuclear plant: radiation emissions. Office of Technology Assessment. 1991. Complex Cleanup: The

26:1345–1346. Am J Epidemiol. 132:397–412; discussion 413–417. Environmental Legacy of Nuclear Weapons Production.

Beyea J, Hatch M. 1999. Geographic exposure modeling: a valu- Hatch MC, Wallenstein S, Beyea J, Nieves JW, Susser M. Washington, DC:U.S. Congress, Office of Technology

able extension of geographic information systems for use in 1991. Cancer rates after the Three Mile Island nuclear Assessment.

environmental epidemiology. Environ Health Perspect accident and proximity of residence to the plant. Am J Osborn, MS. 1996. Three Mile Island: then, now and next time.

107:181–190. Public Health 81:719–724. Synthesis/Regeneration 10(Spring):11–14.

Broad W, Wade N. 1982. Betrayers of the Truth: Fraud and Hefez A. 1985. The role of the press and the medical community President’s Commission on the Accident at Three Mile Island.

Deceit in the Halls of Science. New York:Simon and in the epidemic of “mysterious gas poisoning” in the 1979. The Need for Change: The Legacy of TMI. Washington,

Schuster. Jordan West Bank. Am J Psychiatry 142:833–837. DC:U.S. Government Printing Office.

Brodsky CM. 1988. The psychiatric epidemic in the American Holtzman E. 1981. Science, philosophy and society: Some Prince-Embury S, Rooney JF. 1988. Psychological symptoms of

workplace. Occup Med 3:653–662. recent books. Int J Health Serv 11:123–148. residents in the aftermath of the Three Mile Island nuclear

Cleary PD, Houts PS. 1984. The psychological impact of the Hornung RW, Meinhardt TJ. 1987. Quantitative risk assessment accident and restart. J Soc Psychol 128:779–790.

Three Mile Island incident. J Hum Stress 10:28–34. of lung cancer in U.S. uranium miners. Health Phys Rorty R. 1989. Contingency, Irony, and Solidarity. New