Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

4330 Relational Theory Lecture

Transféré par

John Baptist John BoscoCopyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

4330 Relational Theory Lecture

Transféré par

John Baptist John BoscoDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

COMM 4330, THEORIES OF IPC RELATIONAL THEORY I. DEFINITION OF DYADIC RELATIONSHIPS A.

In general, a dyadic interpersonal relationship can be defined as an association of two people in which the parties meet each other's interpersonal and social needs. B. Functions as a complete unit; interdependent C. Communication within such a relationship is transactional (each person influences and is influenced by the other; direct immediate feedbac!; dyadic effect occurs, etc." #. $ach dyad is uni%ue and has its own culture rituals

$. #yads are the building bloc!s for other relationships (e.g. families" II. GENERAL TYPES OF RELATIONSHIPS (to be e&plored more later" A. Friendships (range from casual ac%uaintances to close friends" B. 'omantic relationships (cross(se& and same(se&" C. Family, or primary relationships (those we grew up in, those we form later" #. Functional (wor! or tas! related relationships with colleagues" III. FUNCTIONS OF IP RELATIONSHIPS(()hy do we form relationships* A. )eiss notes that relationships pro+ide intimacy, social integration, nurturance, ressurance of worth, assistance guidance. B. Bennis, et al. describe , functions.. /. 0. ,. e&pression of feelings confirmation influence of change creation1wor! (instrumental"

C. #e2ito notes the following four functions.. to lessen loneliness /. to secure stimulation (see types of intimacy, abo+e" 0. to gain self(!nowledge self(esteem (recent research suggests that the better we feel about oursel+es, the less li!ely we are to suffer a heart attac!" ,. to ma&imi3e pleasure and minimi3e pain IV. DIMENSIONS OF IP RELATIONSHIPS

A. Context-(remember from the de+elopmental definition, a more intimate relationship will ha+e a minimum of stereotyping, increased self(disclosure, more trust, and the de+elopment of uni%ue rules B. Time((duration plays a part, in that deeper relationships usually ta!e time to de+elop. 4owe+er, not all long term relationships are +ery deep. 5ime also plays a part in so far as we choose to be together. C. Intimacy level((Altman and 5aylor's model of social penetration notes that the more intimate the relationship, the more breadth and depth of self(disclosure. 5hree types of intimacy in dyadic relationships (no one dyad li!ely to pro+ide all three".. emotional /. intellectual 0. physical (needn't be se&ual" #. Relational dimensions also studied by Burgoon et al, who came up with ./ communication aspects of relationships which they call 6the fundamental topoi of relational communication,6 which they group into 4 basic, independent dimensions: .. emotional arousal, composure, formality /. intimacy 0. immediacy similarity li!ing

,. dominance1submission V. STAGES OF IP RELATIONSHIPS A. #e2ito's si&(stage model (see Figure .7.., p. /89, :th ed., #e2ito" .. Contact (perceptual interactional". Contact e&press a desire for contact (greeting messages; e.g. 64i, my name is . . . 6 or 6)hat's a nice guy li!e you doing in a place li!e this*6". /. Involvement (testing intensifying". Closeness is e&pressed by a desire for increased intimacy in+ol+ement (e.g. 6I'd li!e to see you more often6; 6I can really relate to what you're saying6- etc.". ;tabili3ing messages e&press a desire to stabili3e the relationship at a particular stage (e.g. 6<et's =ust be friends((I can't get more in+ol+ed at this point6". 0. Intimacy (commitment social bonding". $&pressed through a social affirmation of your closeness (e.g. 6<et's get married". ,. Deterioration (dissatisfaction". #istancing messages e&press a desire to differentiate,

or mo+e apart from a relationships (e.g. 6I need more space6; 6we need some time apart6; etc." 9. Repair (may or may not occur". 'epair e&presses a desire to fi& the problems in the relationship (e.g. 6we need to tal!6; 6I'm sorry6- 6can't we wor! things out*6 etc." 7. Dissolution (separation". #issolution e&presses a desire to brea! up (e.g. 6it's =ust not wor!ing out6; 6I thin! we should see others6- etc." B. >napp and 2angelisti(('elational ;tages of coming together Cooper" .. Coming Toget er (establishment e&les of tal! at each stage"coming apart (see ?al+in Cooper for

maintenance"((9 stages (see ?al+in

a. initiating((brief ritualistic e&changes, phatic comm. b. e&perimenting((6auditioning6 persons; small tal!, gossip, superficial self( disclosure, idea(e&change, etc. c. intensi!ying((relationship e&pands w1deeper self(disclosure; less stereotyped interactions; sharing feelings, etc. d. integrating((relationship ta!es on an identity as a social unit((sense of 6we( ness6; deep self(disclosure, etc. e. bonding((not all deep relationships reach this le+el; e&tension of integration through public rituals of connection (e.g. marriage, partnership, friendship rings, etc." /. Coming "part (deterioration decay"; 9 stages-

a. di!!erentiating@re(establishment of 6I6; lst occurs during times of stress conflict (remember, conflict is ine+itable; can strengthen or further wea!en a relationship"; statements li!e 6I need to find myself6 or 6I need space.6 ?ood relationships often mo+e bac! forth between differentiating integrating1bonding b. circumscribing((relationship becomes curtailed, both in time spent in amount of tal! (comm. decreases in %uantity %uality"; interest commitment decreases AB5$- many long term relationships ha+e periods li!e these, esp. dual income couples with children. Croblem is when people continue to withdraw. c. stagnating-(If relationship not renewed, circumscribing leads to stagnation(( relationship has no growth, feels 6stale6 and predictable. Can go on for years; needn't lead to ne&t stage if relationship is renewed periodically. d. avoiding((creating distance (both psychological and physical"; can use e&cuses for not getting together or tal!ing about issues; may remo+e self from scene; etc.

(e.g. )ar of the 'oses". e. terminating((the end of the relationship; parado&ically communication can suddenly increase (in part because already made decision to lea+e what is there to lose*"; can be %uic! or drawn out; can be formal or informal; can be mutual or not. Cody found that the more intimate the relationship, the more the feeling of obligation to =ustify terminating it (see also Dnit .E for strategies of disengagement". 0. According to >napp, mo+ement through these stages is generally se%uential and systematic (we usually don't s!ip steps, though may go through them %uic!ly; not e+eryone would agree". Fo+ement can be forward or bac!ward, and steps can be repeated in new cycles. 'elationships can stabili3e indefinitely at any stage. ,. Fo+ement through stages is usually rapid through areas where positi+e rewards ha+e been achie+ed. 9. Fo+ement is also facilitated whene+er time is short (e.g. summer romances", pro&imity is high, certain situational factors (e.g. e&periencing a crisis together, doing =oint acti+ities, etc.", and usually during the early stages. 7. Fo+ement also is influenced by interpersonal needs and personalities. :. Fo+ement in deterioration may be increased if one person +iolates a particularly sacred part of the co+enant (e.g. a betrayal of trust"((this is esp. so when the offended person has ta!en a strong stand and issued warnings to the other, and there is no redress for the +iolation. E. Fo+ement is also rapid when both parties agree the relationship has reached a 6turning point.6 C. ;ocial Cenetration 5heory .. ;ocial Cenetration theory in+ol+es the process of increasing intimacy in a relationship((the more we !now, the more interpersonal our relationships become. Increased !nowledge leads to increased penetration. >nowledge can be of three typesa. Cultural (+alues, beliefs, language, attitudes, etc.", e.g. 6I'm an American li+ing in the Fidwest.6 b. ;ociological (roles, group norms, etc.", e.g. 6I am a student at DCF.6 c. Csychological (traits, feelings, personal beliefs and attitudes, etc.", e.g. 6I'm basically happy with my life,6 or 6I'm an e&tro+erted person.6 /. ;ocial penetration mo+es from cultural to psychological interaction, whereas depenetration mo+es from psychological to cultural. 5he Altman and 5aylor wheel e&plains this mo+ement. Bnly the psychological le+el of communication is considered to be interpersonal. 0. 5he theory is related to #ocial $xc ange t eory, since as a relationship de+elops we not only

gauge the costs and rewards we ha+e now, we forecast future rewards as a way of deciding to increase breadth and depth of communication (see below". Can also be connected as well to Dncertainty 'eduction 5heory (D'5", Berger Calabrese. ,. 4 stages o! development !or a relationshipa. b. c. d. Brientation (sharing impersonal information" $&ploratory (beginning affecti+e e&change plus small tal!" Affecti+e e&change (more feelings" ;table e&change (highly intimate, +ery rewarding, permits ma&imum prediction"

9. "ltman-Taylor % eel. 5his model, by I. Altman and #. 5aylor, suggests that relationships de+elop incrementally, mo+ing from superficial le+els of disclosure to more personal le+els of disclosure. a. ;ocial penetration means that the breadth and depth of communication increases as the relationship progresses. b. #epenetration (also !nown as the re+ersal hypothesis" means that as relationships deteriorate, generally the depth and breadth of communication decreases. c. Breadth- 'efers to the number of different topics a+ailable during interaction with the actual amount !nown as breadth fre%uence. d. #epth- 'efers to the le+el or depth of information discussed; how personal or intimate it is. 7. Ceople ha+e a basic orientation to self(disclosing, but it also changes with different relationships at different times. 4 general orientationsa. low breadth, low depth (e.g. the under(discloser; the new relationship" b. low breadth, high depth (e.g. the therapeutic relationship; close friends" c. high breadth, low depth (e.g. an ac%uaintance1casual friend relationship" d. high breadth, high depth (e.g. the o+er(discloser; the intimate relationship" #. ;ocial $&change 5heory (Cost(reward" and relational de+elopment. .. 'elational de+elopment is influenced by ;ocial $&change 5heory, or the rewards or costs in a relationship (see below for additional de+elopment of ;ocial $&change 5heory". /. 'ewards refers to 6the pleasures, satisfactions, and gratifications, the person en=oys. 5he pro+ision of a means whereby a dri+e is reduced or a need fulfilled constitutes a reward.6 0. Costs refer to 6any factors that operate to inhibit or deter a performance of se%uencing beha+ior.6 5he greater the deterrents or inhibitions, the greater the costs (e.g. costs are high when great effort is re%uired, when the potential for embarrassment is high, when there are conflicting desires, when there are mental or physical punishments, etc.". ,. In general, then, we de+elop relationships that enable us to ma&imi3e profits, from which we deri+e more rewards than costs.

9. Both costs and rewards can be e&ogenous, or e&ternal (e.g. money, status, doing fun things together, etc." and endogenenous, or internal (e.g. the person meets our needs". 7. $ach person's beha+ioral repetoire (actual and potential actions" yields a particular goodness of outcome, which we assess. :. )e rate new and on(going relationships with according to comparison le+els. 5hese are the standards we use to =udge potential or actual rewards costs. a. 5he first le+el, !nown as C< is a measure of satisfaction and attracti+eness. )e e+aluate the benefits +ersus costs, and continue to be attracted when the former outweighs the latter. b. 5o e&plain why people stay in bad relationships is the le+el C< alt (a measure of dependency, or the lowest le+el of negati+e outcomes tolerated when considering alternati+es and the li!elihood of remaining in a relationship". c. 5hese two comparison le+els lead to four predictions about new or on(going relationships." stable-satis!actory((current relationship is seen as better than past or future prospects (6a good deal6". /" &nstable-satis!actory((current relationship may be more rewarding than those in the past, but not better than future possibilities (e.g 6playing the field6". 0' #table-unsatis!actory((current relationship is not better than those in the past, but seen as better than alternati+es (6ma!ing do6; may also e&plain why people stay in what seem to be bad relationships, since being with a !nown bad thing is preferable to an un!nown bad thing". ," &nstable-unsatis!actory((current relationship is not as rewarding as the past, and not better than alternati+e or future choices (e.g. a blind date". E. 5hese comparisons change o+er time and situation. A relationship can start in one mode, then change to another, as conditions change. 8. In addition, the +alue of rewards and costs tends to increase as the relationship becomes more intimate (the sta!es get higher", intimates ha+e more resources for dealing with percei+ed costs (doesn't ha+e to be tit(for(tat" and can tolerate periods where costs e&ceed rewards (6it will all e+en out in the end6". $. 'elational dialectics (Ba&ter; )at3lawic!; etc.". .. 5here are +arious factors or dimensions of IC relationships which are in dialectical relationship with each other. /. A dialectic is a tension between two or more contradictions, which we must manage in some

way (either resol+e the dialectic in fa+or of one pole, or learn to li+e with the tension". 0. Contextual dialectics((what is the place of the relationship in the society at large* a. public e&pectations +ersus pri+ate elements b. ideal notions about relationships +ersus reality ,. Relational dialectics((in+ol+e tensions within the relationship. a. autonomy(connection((tension between independence and connection. ." 5here may be a se& difference (men may be more li!ely to see! autonomy and women more li!ely to see! connection through relationships. /" 5his can create communication difficulties between women and men (e.g. her attempts to emphasi3e with him may be construed as competition or control; see 5annen". b. novelty(predictability((we see! no+elty, but also li!e predictability and consistency. c. closedness(openness((tension between desires to be e&clusi+e +s. e&pansi+e. d. control(e)uality((the tension between attempts to ha+e power o+er +s. sharing power. 9. Also, remember the difference between complementary and symmetrical patterns of communication. 5here also are additional dialectics depending on type of relationship (e.g. friendship" VI. RELATIONAL ATTRACTION((why relationships. A. ;e+eral factors influencing attraction.. "ppearance. a. Appearance is most important early in a relationship. b. Cercei+ed attraction aids desirability as a potential partner. c. Attracti+e people are seen as more li!eable, trustworthy, competent, credible, intelligent, etc. (and tend to ha+e more success in life, as there is discrimination against those our culture considers plain or homely". d. Appearance attracti+eness is culturally learned, and +aries o+er time. For e&le, weight. In our culture, thin is considered attracti+e, esp. for women, and o+erweight is considered +ery unattracti+e (although studies differ on what is considered o+erweight; usually men in the D.;. are not attracted to women who are as thin as most models". 5his is not true in some cultures (e.g. in some $uropean and Fiddle $astern countries, men li!e plump women". Aor was it true a century or more in the past, where obesity was a sign of wealth. $+en in mid(twentieth century, women were considered attracti+e at larger si3es (e.g. Farilyn Fonroe ranged between si3e ./(.7 (in today's si3ing, si3e .G(.,; e+en gi+en differences in si3es from then to now, she still was not a s!inny woman"; the a+erage si3e of American women today is a si3e ., (thirty years ago this was probably a si3e .7, and still is in the D.>.". how we are drawn to others to form

e. Cleasant personalities and grooming can ma!e us seem more attracti+e physically. f. 5he importance of this factor decreases o+er time and with age. *. +roximity. a. )e are attracted to those with whom we interact most fre%uently. b. )e de+elop relationships with those with whom we are familiar, or see e+ery day (e.g. roommates, people who li+e ne&t to us, those we wor! with, etc.". c. 5here is some e+idence that =ust being e&posed to people increases our attraction for them, as long as our initial encounters are positi+e or neutral (remember the primacy effect". d. As an e&le, >napp disco+ered that persons in a residence hall were more li!ely to become friends with those on the same floor rather than on different floors. 0. #imilarity a. demographics b. +alues and beliefs c. ,alance t eory((we li!e people who li!e what we li!e (or whom we thin! li!e what we li!e", and disli!e those who don't. )e also don't want someone we disli!e to li!e what we li!e, as it creates imbalance. )hen those we li!e, li!e the same things we do, it pro+ides social +alidation and aids our predicti+e abilities (reduces uncertainty". d. t e matc ing ypot esis predicts that we will date and mate with people we percei+e as similar to us in physical attracti+eness (though there are e&ceptions". ,. Complementarity((6opposites attract.6 a. )e often see! out those who are different from us in some ways, especially in ways that we'd li!e to be. 5herefore, and intro+ert may be attracted to an e&tro+ert, a sensor to an intuiti+e, etc. )e might find people of different religions or bac!grounds e&citing. b. If too different, may ha+e some difficulties ad=usting, but usually these relationships are as solid as those formed on similarity factors. 9. Reciprocity((we li!e those who are reciprocal in their beha+iors (who share the burdens and commitments of the relationship". 7. Competency((we are attracted to successful persons (as long as not too competentH". :. Rein!orcement((we are more attracted to those who reinforce us or reward us. )e also tend to li!e those whom we reward. B. "!!inity-see-ing strategies .. 5hese are ways to increase our attracti+eness to others

/. ;ome ways to do so include being altruistic, appearing to be in control, presenting oneself as an e%ual, presenting oneself as rela&ed and confident, seeming to be warm and friendly, etc. 0. Ceople who are high self(monitors are more li!ely to use such strategies, as are those who indicate positi+e immediacy beha+iors (e.g. smiling, positi+e touching, eye contact, etc.". VIII. RELATIONAL REPAIR & DISSOLUTION A. #eterioration occurs when rewards are reduced and costs increase. )e often stay in bad relationships for a number of reasons, such as con+enience, children, fear, financial considerations, and =ust plain inertia. ;e+eral theories discuss dissolution, but the primary theories are from ;te+e #uc!, the 6#issolution Fap,6 and <eslie Ba&ter, strategies of disengagement. B. 'epair strategies can +ary; #e+ito recommends the '$CAI' model.. 'ecogni3e the problem /. $ngage in producti+e conflict resolution 0. Cose possible solutions ,. Affirm each other 9. Integrate solutions into normal beha+ior 7. 'is! new things((apply interpersonal s!ills and consider specific reconciliation strategies. 5his process needn't be bilateral. C. #uc!'s 6Fapping dissolution6 .. A general phase model, based on the assumptions that dissol+ing a relationships in+ol+es comple& decisions and is non(linear (in this way, it pro+ides a counter(theory to ;ocial Cenetration". /. #uc! argues that relational dissolution is sporadic, inconsistent, and ambi+alent, often with attempts to reconcile. 0. 5his roc!y course is based on certain t res olds or points o! decision that define the boundaries of each of the four phasesa. Intra-psyc ic p ase. 5his is the first threshold (6I can't stand it anymore6". ." 5he dissatisfaction, which may ha+e been growing for some time, is recogni3ed on an intrapersonal le+el. /" 5he unhappy partner focuses on the other's beha+ior and the ade%uacy of the other's role performance (as regards e&pectations". 0" 4ere is where we are li!ely to e+aluate the costs +ersus the rewards of being in the relationship. ," 5here are two dilemmas which arise in this phasea" $xpress(repress((you decide if you will e&press the dissatisfaction to

your partner (and attempt to wor! it out". If so, mo+e into ne&t phase. b" Con!ront(avoid((related to the abo+e is the desire to confront your partner +ersus a+oid the conflict. b. Dyadic p ase. 5his is the second threshold (6I'm =ustified in lea+ing6". ." Iou focus on the relationship itself, confronting your partner through tal!. /" Iou consider not only your own dissatisfaction and perceptions, but also those of the other person. 0" Iou tal! about whether or not your are going to sol+e problems or split up. If repair doesn't occur at this stage, you mo+e onto the ne&t. c. #ocial p ase. 5his is the third threshold (6I mean it, I'm lea+ing6". ." Iou focus on the larger group (family, friends, co(wor!ers, etc." and weigh their feelings and opinions with your own to help you decide the ne&t course of action. /" In this gossip1discussion, you may also tell stories that assign blame and1or help you sa+e face. 0" Iou may decide the social costs are not worth a full brea!(up, and call in 6inter+ention teams6 (e.g. family members or friends, or therapy groups", to help repair the relationship. d. .rave dressing p ase. 5his is the ,th and final threshold (6It's ine+itable; it's o+er6". ." 5his occurs after the final rift, when no further repair is possible. /" 5he partners gi+e their own accounts of what happened to others, and go their own ways. 0" 5here is an attempt to cope with the termination (to mourn, hence the idea of 6dressing the gra+e6". Iou do 6getting o+er it6 acti+ities, including a re+iew of the relationship to figure out what went wrong (so you can a+oid it in the future". #. Ba&ter's theory of communication strategies used in disengagement is one that poses that such strategies +ary in directness and concern for the other person#irect ((((((((((((((((((((((((((( $&pedient (((((((((((((((((((((( Blunt ((((((((((((((((((((((((((( Indirect Ine&pedient A+oiding hurt

$ndings are of two main types (can also combine both".. &nilateral. Indirect strategies are more li!ely, including the followinga. %it dra/al (a+oiding and circumscribing beha+iors"((unilaterally a+oiding the other person. b. +seudo de-escalation((pseudo because it is fa!e, a lie such as 6let's remain friends6 when you really mean 6it's o+er.6 c. cost-escalation((a unilateral tactic in which one person beha+es so badly the other person lea+es first.

/. ,ilateral. 5his type includes both indirect and direct strategies, such as a. 0ading a/ay((bilateral situation in which both persons see less and less of each other, and by this implicitly ac!nowledge that it's o+er. b. 1utual pseudo de-escalation((both agree to pretend to be 6friends6 to help sa+e face and a+oid hurt. 5his is what I thought I was doing with my e&(husband, but it turned out to be unilateral (he actually didn't mean for us to stop being lo+ers, =ust to not be married". c. Fait accompli((one partner ma!es a blunt, direct statement to the other that 6it's o+er.6 5he other may or may not agree, but there is usually no further discussion (this is what I finally did with my e&(husband". d. #tate o! t e relations ip tal- (both parties dissect and analy3e the relationship, as a type of post(mortem; can also be unilateral" e. "ttributional con!lict((a direct, bilateral fight in which each person blames the other for the problems in the relationship. f. 2egotiated !are/ell((a mutual parting of the ways without hostility or blame. 0. ;trategies that indicate a lac! of concern for others include withdrawal, cost( escalation, fait accompli, and attributional conflict. 5he others indicate some attempt to smooth the waters and sa+e face. ,. #irectness may be the primary issue in deciding how to disengage from a relationship. 9. )e learn more methods as we mo+e from childhood to adulthood. #irectness is both a personality characteristic and related to age. Ioung children ha+e few strategies, and tend to be more direct than either adolescents or adults. Adults are more indirect than adolescents, since indirect strategies usually try to a+oid hurt. 7. Ba&ter found no gender difference, e&cept that androgynous persons tend to be more direct than those who are highly 6feminine6 or 6masculine6 (those types ha+e different reasons for indirectness". :. Ceople who ha+e high communication apprehension tend to be more indirect. E. 5he more intimate the relationship, the greater the tendency to use caring direct strategies. Finally, all ages ha+e more strategies for starting relationships than for ending them. 8. <i!e #uc!, Ba&ter argues that relational disengagement is comple&. It is more than =ust a mere bac!ing out or reduction of intimacy in a relationship. It often is cyclical, with different strategies at different points. .G. #isengagement seems to occur along particular tra=ectories, or course of action. a. )hich is chosen is dependent upon a number of +ariables, such as the precipitating e+ents (e.g. incremental or single incidents", whether or not the decision is mutual, how the other person reacts, and the degree of certainty of the decision (+ersus ambi+alence". b. Four tra=ectories e&ist." +ersevering indirectness((the use of indirect strategies on a number of occasions (hinting that its o+er, or trying to ma!e the other decide, etc.".

/. "mbivalent indirectness((attempts are made to repair the relationship before gi+ing in and terminating it. 0. #/i!t explicit mutuality((the use of bilateral, direct, and e&pedient (%uic!" strategies (a clean brea!, mutually desired". ,. 1utual ambivalence((the use of indirect strategies, in+ol+ing se+eral attempts at repair, ta!ing a long time. )hen combined with #uc!'s concepts, Ba&ter's concepts pro+ide a much fuller picture of relational dissolution. IX. CRITICISM OF RELATIONAL THEORY A. ;trengths.. 5he trend in many of these theories, especially those related to stages, is to de( emphasi3e indi+idual traits and focus instead on interacti+e and relational dynamics. /. 5hus, many of these theories reinforce the de+elopmental model of ICC. 0. 5hese theories ha+e been +ery heuristic, leading to a lot of important research. ,. Fany of them appeal to us because of intuiti+e 6fit6 with our own li+es((they ha+e e&planatory power for us. 5hey 6ma!e sense6 on a gut le+el. 9. ;ocial $&change 5heory is +ery parsimonious (able to e&plain almost any aspect of social beha+ior with +ery few ideas". B. )ea!nesses.. Fost of these theories indicate conceptual confusion (relationship is as difficult to define as communication". ;ome ideas are hard to distinguish from others. /. )ith ;ocial $&change theory in particular, it is not always clear what is punishing and what is rewarding. 0. Fost of these theories ha+e a limited focus((they show part of a pu33le, but not the whole; each lea+es out important elements. a. 'esearch often limited to obser+able data, ignoring important cogniti+e processes, emotional data, etc. b. ;ocial $&change and ;ocial Cenetration in particular 6put all their eggs in the cost(reward bas!et6 and fail to deal with both relational and cogniti+e processes that might affect the ways in which costs and rewards are defined (more indi+idualistic than relational, in that see relationships as a series of choices moti+ated solely by personal gain". c. Fany are o+erly rationalistic (does real life really wor! this way*". ,. 5end to be reductionist and thus o+ersimplify the processes of relational de+elopment(( this is especially true of ;ocial Cenetration and ;ocial $&change theories. 9. 5oo mechanical and orderly (linear".

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (120)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (588)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (266)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (399)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5794)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2259)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1090)

- Final Self Hypnosis Paperback For PrintDocument150 pagesFinal Self Hypnosis Paperback For PrintRic Painter100% (12)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (895)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (73)

- Brahms Symphony No 4Document2 pagesBrahms Symphony No 4KlausPas encore d'évaluation

- Cool Fire Manual 45M620N2UK 01 PDFDocument198 pagesCool Fire Manual 45M620N2UK 01 PDFPaun MihaiPas encore d'évaluation

- Vitamin C Lab PDFDocument7 pagesVitamin C Lab PDFJohn Baptist John Bosco100% (1)

- Healthymagination at Ge Healthcare SystemsDocument5 pagesHealthymagination at Ge Healthcare SystemsPrashant Pratap Singh100% (1)

- Enrico Fermi Pioneer of The at Ted GottfriedDocument156 pagesEnrico Fermi Pioneer of The at Ted GottfriedRobert Pérez MartinezPas encore d'évaluation

- Oceanarium: Welcome To The Museum Press ReleaseDocument2 pagesOceanarium: Welcome To The Museum Press ReleaseCandlewick PressPas encore d'évaluation

- Manual de Operacion y MantenimientoDocument236 pagesManual de Operacion y MantenimientoalexPas encore d'évaluation

- Soundarya Lahari Yantras Part 6Document6 pagesSoundarya Lahari Yantras Part 6Sushanth Harsha100% (1)

- 160kW SOFT STARTER - TAP HOLE 1Document20 pages160kW SOFT STARTER - TAP HOLE 1Ankit Uttam0% (1)

- Exp 6 Calculation Preparation of Bis (Acetylacetonato) Copper (II)Document1 pageExp 6 Calculation Preparation of Bis (Acetylacetonato) Copper (II)John Baptist John Bosco100% (1)

- 1 2 Hess's LawDocument4 pages1 2 Hess's LawJohn Baptist John BoscoPas encore d'évaluation

- Chem019 - Spectrophotometric Analysis of AspirinDocument5 pagesChem019 - Spectrophotometric Analysis of AspirinJohn Baptist John Bosco0% (1)

- Mountaindew LabDocument6 pagesMountaindew LabJohn Baptist John BoscoPas encore d'évaluation

- 162 Sample LabDocument6 pages162 Sample LabJohn Baptist John BoscoPas encore d'évaluation

- 162 Sample LabDocument6 pages162 Sample LabJohn Baptist John BoscoPas encore d'évaluation

- Lab Fe Pill RedoxDocument2 pagesLab Fe Pill RedoxJohn Baptist John BoscoPas encore d'évaluation

- Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2001 Pietinen 339 44Document7 pagesCancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2001 Pietinen 339 44John Baptist John BoscoPas encore d'évaluation

- Recommendations On BMWDocument2 pagesRecommendations On BMWJohn Baptist John BoscoPas encore d'évaluation

- Formal Correspondence WritingDocument17 pagesFormal Correspondence WritingJohn Baptist John BoscoPas encore d'évaluation

- Nfpa 1126 PDFDocument24 pagesNfpa 1126 PDFL LPas encore d'évaluation

- Seizure Control Status and Associated Factors Among Patients With Epilepsy. North-West Ethiopia'Document14 pagesSeizure Control Status and Associated Factors Among Patients With Epilepsy. North-West Ethiopia'Sulaman AbdelaPas encore d'évaluation

- Fortigate Firewall Version 4 OSDocument122 pagesFortigate Firewall Version 4 OSSam Mani Jacob DPas encore d'évaluation

- LPS 1131-Issue 1.2-Requirements and Testing Methods For Pumps For Automatic Sprinkler Installation Pump Sets PDFDocument19 pagesLPS 1131-Issue 1.2-Requirements and Testing Methods For Pumps For Automatic Sprinkler Installation Pump Sets PDFHazem HabibPas encore d'évaluation

- Electrical Engineering Lab Vica AnDocument6 pagesElectrical Engineering Lab Vica Anabdulnaveed50% (2)

- IOT Architecture IIDocument29 pagesIOT Architecture IIfaisul faryPas encore d'évaluation

- Report DR JuazerDocument16 pagesReport DR Juazersharonlly toumasPas encore d'évaluation

- Daewoo 710B PDFDocument59 pagesDaewoo 710B PDFbgmentPas encore d'évaluation

- Multimedia System DesignDocument95 pagesMultimedia System DesignRishi Aeri100% (1)

- Pelayo PathopyhsiologyDocument13 pagesPelayo PathopyhsiologyE.J. PelayoPas encore d'évaluation

- Philhis 1blm Group 6 ReportDocument19 pagesPhilhis 1blm Group 6 Reporttaehyung trashPas encore d'évaluation

- Arts 6 Week 6Document9 pagesArts 6 Week 6JENNEFER ESCALAPas encore d'évaluation

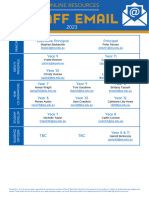

- 2023 Teacher Email ListDocument5 pages2023 Teacher Email ListmunazamfbsPas encore d'évaluation

- Bioinformatics Computing II: MotivationDocument7 pagesBioinformatics Computing II: MotivationTasmia SaleemPas encore d'évaluation

- 21 Tara Mantra-Wps OfficeDocument25 pages21 Tara Mantra-Wps OfficeAlteo FallaPas encore d'évaluation

- G1000 Us 1014 PDFDocument820 pagesG1000 Us 1014 PDFLuís Miguel RomãoPas encore d'évaluation

- ইসলাম ও আধুনিকতা – মুফতি মুহম্মদ তকী উসমানীDocument118 pagesইসলাম ও আধুনিকতা – মুফতি মুহম্মদ তকী উসমানীMd SallauddinPas encore d'évaluation

- Lenovo NotebooksDocument6 pagesLenovo NotebooksKamlendran BaradidathanPas encore d'évaluation

- Cultural Sensitivity BPIDocument25 pagesCultural Sensitivity BPIEmmel Solaiman AkmadPas encore d'évaluation

- Natural Cataclysms and Global ProblemsDocument622 pagesNatural Cataclysms and Global ProblemsphphdPas encore d'évaluation

- IQAc 04-05Document10 pagesIQAc 04-05ymcacollegewebsitePas encore d'évaluation