Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Counseling - Maslow's Hierarchy

Transféré par

Giolina PanopoulouCopyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Counseling - Maslow's Hierarchy

Transféré par

Giolina PanopoulouDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

International Journal for the Advancement of Counselling, Vol. 25, No.

1, March 2003 ( C 2003)

Counseling Children in Crisis Based on Maslows Hierarchy of Basic Needs

Frederick D. Harper,1,4 Jacqueline A. Harper,2 and Aaron B. Stills3

This article addresses how Maslows hierarchy of basic human needs can be used as a framework for cross-cultural counseling with children in crisis; that is, children of the world who are unable to fulll adequately their basic human needs because of extreme circumstances such as natural disaster, violence, various forms of child abuse, extreme poverty, lack of school and community resources, and emotional abandonment. Assessment of child needs is discussed and counseling strategies are presented; strategies that include supportive counseling techniques, crisis intervention techniques, program development, delivery of social services and resources, referral to helping agencies, and counselor consultation with parents and other signicant adults in the lives of children.

KEY WORDS: children; Maslow; client needs; self-actualization.

INTRODUCTION As used in this article, children in crisis are children of the world (infancyto-puberty age) who are continually at risk for being unable to fulll adequately their basic human needs as described by Maslow (1970). These children include those who live with hunger for food, with inadequate shelter, in daily fear of violent threat, in unhealthy and unsafe conditions, under the psychological pain or emotional abandonment, or in a quiet state of painful neglect, rejection, or abuse (Bruntland, 2000; DeLay, 2000; Kaslow, 2001; Saigh, 1998). Maslow (1970) posits that all human beings, regardless of culture, have ve basic needs that can be arranged on a hierarchy according to prepotency or pressing

1 Professor

of Counseling, School of Education, Howard University, Washington, DC. School Counselor, Prince William County Public Schools, Woodbridge, Virginia. 3 Associate Professor of Counseling, School of Education, Howard University, Washington, DC. 4 Correspondence should be directed to Frederick D. Harper, Ph.D., Professor of Counseling, School of Education, Howard University, Washington, DC 20059; e-mail: fharper884@aol.com.

2 Elementary

11

0165-0653/03/0300-0011/0

C

2003 Kluwer Academic Publishers

12

Harper, Harper, and Stills

Fig. 1. Maslows (1970) hierarchy of basic needs based on his theory of human motivation.

drive for fulllment. From the lowest level of needs (the most prepotent needs) to the highest level, these include physiological needs, safety needs, need for belongingness and love, esteem needs, and self-actualization (see Fig. 1). The most prepotent need group, physiological needs, relates to the bodys need for food, water, oxygen, optimal temperature, and sleep in order to maintain physiological homeostasis and survival. The second most prepotent need group, safety needs, includes needs for security, protection, stability, and freedom from fear or constant anxiety. Need for belongingness and love, the next level, is described by Maslow as the need to belong to and feel loved by a group; such as ones family, religious group, work group, professional group, social club or fraternity, or even ones youth gang. The next hierarchical level, esteem, has to do with self-esteem for ones accomplishments or achievements and deserved esteem from others, based on ones accomplishments, status, or appearance. The highest Maslowian need is self-actualization, which is the need to develop ones common potential and unique talent at the highest possible level of growth and achievement. As regard to prepotency of needs, Maslow (1968, 1970) explains that the most prepotent needs of the person occupy the conscious efforts and striving

Maslows Hierarchy of Basic Needs

13

toward satisfaction, while the less prepotent needs are minimized, suppressed, or denied. Therefore, when one need is satised, the next prepotent need emerges to dominate the drive or conscious motivational efforts of the person. Although all human beings have the same basic needs, according to Maslow (1970), they may differ individually and culturally in their ability to fulll their needs. Harper and Stone (1999, 2003) suggest that the ease versus difculty of a human being to fulll basic needs is often inuenced by that persons ethnic, social-class, economic, political, or religious status within a given culture, as well as the environmental resources or opportunities that are available for the need-fulllment of people of a given culture or country. Within the framework of Maslows basic needs, vis-` a-vis environmental opportunity for need-fulllment, this article addresses crisis events and environmental conditions that may present challenges to the fulllment of the needs of children. In addition, it presents strategies that counselors can use in order to facilitate the need-fulllment of children in crisis. GLOBAL CHALLENGES: PROBLEMS AND NEEDS OF CHILDREN In todays world, an increasing number of children are faced with crises because of rapidly changing environmental conditions that challenge stability in their lives as well as their ability to meet basic needs as described my Maslow (1970). Examples of these challenging conditions for children include: 1. Natural disasters such as earthquakes, cyclones, hurricanes, and oods (Mohapatra & Rath, 2001; Roy, 2001; Saigh, 1998; Shelby & Tredinnick, 1995). 2. Violent warfare within and between countries as well as violent crime within cities (Israelashvili, 1999; Johnson, 1998; Saigh, 1998). 3. Bullying and violence in schools (Colvin, Tobin, Beard, Hagan, & Sprague, 1998; Harper & Ibrahim, 1999). 4. Physical and sexual child abuse (Becker & Bonner, 1998; DeLay, 2000). 5. Alcohol and other drug abuse by parents and, in some cases, children (Gullotta, Adams, & Montemayor, 1995; Kritsberg, 1985). 6. Severe famine and hunger, especially in geographic areas of Africa, India, and South America (Kaslow, 2001). 7. High rates of HIV/AIDS and the impact on children and families in SubSaharan Africa, South Asia, and other at-risk AIDS areas of the world (Brundtland, 2000; Hickson & Mokhobo, 1992; Tobias, 2001). 8. Emotional abandonment of children by parents who are too busy with their personal issues, careers, or life activities (Hoffman, 1996; Richards, 1999). 9. Adjustment challenges of migrating families with children (Tatar, 1998; Vontress & Epp, 2000).

14

Harper, Harper, and Stills

10. Loss of a parent or parents because of events such as fatal disease, accidental death, homicide, suicide, warfare, terrorism, marital divorce/ separation, or imprisonment (Brundtland, 2000; McConnell & Sim, 1999; Saigh, 1998; Shelby & Tredinnick, 1995). 11. Community and family disruption caused by job or income losses that are brought on by globalization, local industrial changes, ecological changes, or sociopolitical changes (Marshall, 2001; Stockton, Kaladow, & Garbelman, 2001). In a recent issue of the American Psychologist, under its section of International Perspectives, Kaslow (2001) presents trends, problems, and dilemmas that challenge families and children as the world enters this new millennium. Among worldwide events and circumstances that are negatively impacting families and children, Kaslow includes (a) sociopolitical changes, social revolution, and war in a number of countries such as those in the former Soviet Union, Eastern Europe, Africa, and the Middle East; (b) increased cases of physical and sexual abuse of children by family members; (c) an escalating rate of marital divorce; (d) worldwide increases in addictive behaviors such as alcoholism and other drug addiction; (e) increased incidences and magnitude of wars, famine, persecution, and national disasters; (f) increased rates of child kidnapping, homeless children, runaway children, and throwaway children in both developing and developed countries; (g) the readjustment challenges of shifting populations due to immigration and displaced refugees from countries such as Cuba, Somalia, Bosnia, and Iraq; (h) the impact of the HIV/AIDS epidemic and AIDS-related deaths on families and children; and (i) the impact of cyberspace and news media on youth (e.g., the Internet, media violence, instant communication via e-mail, and other telecommunication technology). Overlapping some of Kaslows (2001) trends, problems, and dilemmas for families and their children, Harper (1998) delineated a brief list of challenges related to counseling families and children in his keynote paper at the Annual Conference of the International Association for Counselling in Paris. On the eve of the new millennium, Harper cited the following challenges to counseling families and children: 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. Preserving the ecological integrity of our world environment Maintaining peace and stability in the world community Safeguarding children and families of the world Helping human beings around the world to meet their basic human needs Helping people to develop their common and unique potential Helping human beings to manage stress, to nd meaning in life, and to learn how to live together as one human race

Harpers (1998) short list of global challenges to children and their families echoes themes from Maslows need theory of motivation in terms of maintaining

Maslows Hierarchy of Basic Needs

15

world stability and safeguarding children (safety needs), helping clients to meet human needs (Maslows hierarchy of needs), and helping clients to develop their common and unique potential (self-actualization).

CONCEPT OF THE NEEDS OF CHILDREN IN THE COUNSELING LITERATURE Except for school counseling, the counseling literature, in general, tends to focus on adult clientele; thus, the counseling profession has minimized a focus on counseling children and the prevention of problems that often begin in early childhood (Gibson & Mitchell, 1999; Harper & Deen, 2003). Moreover, as regard to mental health counseling, Western training of counselors has had a tendency to focus on interpersonal conict, intrapersonal conict, and symptomology versus need-fulllment. Western-oriented counseling literature and diagnostic classications, in particular, appear to focus on symptomology; often in terms of decit behavior, excessive behavior, or deviant behavior of the child, rather than a tendency to focus on the underlying needs of the child that are often expressed in overt behavioral manifestations. For example, the DSM-IV (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders), a popular diagnostic tool developed in the USA, does not mention the word need in its subject index, and the diagnostic disorders delineated under the category of disorders diagnosed during infancy, childhood, and adolescence are often based on behavioral criteria that suggest a deviation from Western societal norms or a deviation from mainstream, culturally expected behaviors (American Psychiatric Association, 1994). Western Counseling Viewpoints Related to Needs As regard to traditional Western counseling theories that address human needs, Glassers (2000) Reality Therapy is among the few counseling theories that focus on the concept of human needs. Glassers (1965) early development of reality therapy was based on his professional work with youth. Moreover, his early work with children and adolescents focused even more than his current thinking, so it seems, on some of Maslows concepts of needs, especially self-worth (selfesteem) and love. Glasser (1965) reects the importance of Maslows basic needs for love and esteem in working with children as suggested by his statement that counselors must be concerned with two basic psychological needs: The need to love and be loved and the need to feel that we are worthwhile to ourselves and to others (p. 9). Another counseling viewpoint that addresses the importance of child needs is that by Gibson, Mitchell, and Basile (1993), who take the position that counseling goals should be based on the needs of children. In determining the needs of children,

16

Harper, Harper, and Stills

Gibson, et al. (1993) note that the counselor should survey children as well as their teachers, parents, and other signicant adults in their lives. In a more recent work, Gibson and Mitchell (1999) discuss the signicance of Maslows needs in setting goals for counseling children. Similar to Gibson and Mitchells position, transcendent counseling is another counseling approach that values satisfaction of basic needs as one of its goals of counseling (Harper & Stone, 1986, 1999, 2003). In addition, Nicholson and Golsans (1983) The Creative Counselor discusses the importance of Maslows basic needs as a perspective for counseling youth. Nicholson and Golsan suggest that counselors should nd eclectic or creative ways to meet the needs of all clients, including children. They further state that counselors should be careful not to allow their own personal needs to interfere with the needs of their clients. Non-Western Counseling Viewpoints Related to Needs Counselors in developing countries and/or countries that are environmentally challenged by intermittent natural disasters, war, and extreme poverty have often found it necessary to focus on unfullled physiological needs and the necessity for survival or safety. Some of these geographical areas of the world include various countries of Africa, Asia, South America, and the Commonwealth of Independent States (formerly, the Soviet Union). As regard to natural disasters and poverty in India, Mohapatra and Rath (2001) discuss counseling families and children in need during the aftermath of a supercyclone and other natural disasters of great magnitude in India. They contend that the children are among the greatest sufferers in such disasters, especially in terms of physiological needs for shelter and food and psychological need for a sense of security and stability. Roy (2001), a crisis counselor, provides a report on the urgent human needs that resulted from an Earthquake in Gujarat, India, e.g., in terms of basic needs for food, medical aid, and shelter for disrupted families and children. Ntoi (2001) and Brundtland (2000) discuss the negative impact of HIV/AIDS in southern Africa in terms of infected young mothers, babies, and children as well as the high number of AIDS-related deaths of wage-earning men who are so crucial to the livelihood of their families. Regarding non-Western counseling viewpoints of human needs, Vontress and Epp (2000) observe that the role of the traditional healer in West Africa involves addressing medical and physiological needs as well as psychological and spiritual concerns of the client. Vontress and Epp go further to explain that traditional healing or counseling in West Africa tends to be holistic, because it deals conjointly with problems of the mind, body, and spirit. At the Annual Conference of the International Association for Counselling in Thessaloniki, Greece, Sizikova (2000) spoke of the exasperating efforts of counselors in Russia as they attempt to nd resources and medicines simply to meet the daily basic needs for the survival of

Maslows Hierarchy of Basic Needs

17

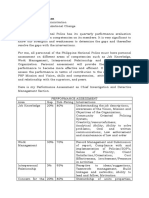

many of their clients. As regard to India, Roy (2001) discusses crisis counseling as essentially a process of focusing on the physiological and safety needs of families and children in crisis due to natural disasters and poverty. ASSESSING MASLOWS NEEDS IN CHILDREN Based on Maslows (1968, 1970) theoretical assumptions as well as supportive empirical research of others (Daftuar & Sharma, 1998; Hagerty, 1999), children of different cultures and countries have the same basic human needs. Therefore, the question can be raised, How can counselors and other helping professionals in various sectors of the world recognize unfullled needs of children based on visible or inferred conditions, problems, and behaviors; and, subsequently, how can counselors and other helping professionals act to facilitate the satisfaction of unmet needs of children? On the one hand, counselors should be cognizant that not all counseling problems of children are related to basic needs; nevertheless, on the other hand, counselors should also be aware that they can many times overlook problems that are simply based on the unfullled needs of a child. Thompson and Rudolph (1983), in Counseling Children, provide a discussion (pp. 810) of how Maslows hierarchy of basic needs can be used as a framework for counselors to assess the needs of children. They suggest that counselors and teachers should observe conditions that suggest unfullled needs in students, for example, in term of (a) signs of insufcient food and poor nutrition (physiological needs), (b) indications of abusive homes or bullying in schools (safety), (c) evidence of rejected or isolated students (need for belongingness and love), (d) tendency of teachers to disrespect and psychologically reject students (need for esteem), and (e) a pattern of not encouraging or even discouraging students from developing a natural talent or ability (need for self-actualization). Gibson, Mitchell, and Basile (1993) go further to delineate six steps that the counselor should take in assessing the needs of children: (a) collecting data, (b) interpreting the data, (c) prioritizing the needs, (d) establishing objectives for children, (e) developing activities based on available resources, and (f) planning for improvement based on evaluation. Along with Thompson and Rudolphs (1983) use of environmental conditions and Gibson, Mitchell, and Basiles (1993) framework of six steps for assessing child needs, we have developed a simple, forced-choice, yes-no, inventory for the counselors use as a quick method of generating information on unfullled needs of a child (see Table 1). The brief, 16-item inventory or questionnaire provides questions about the child client based on Maslows hierarchy of human needs. As an alternative to the yes-no responses, the counselor can feel free to expand the responses from a two-level response (yes or no) to a three-level scale (e.g., the three responses: yes, to some degree, or no) or a ve-level, Likert-type scale for each item (Anastasi & Urbina, 1997). In developing this inventory, we attempted to word the items to include cross-cultural or universal conditions related to the

18

Harper, Harper, and Stills Table I. Inventory for Assessing Maslows Needs in Children Yes No

1. Do counselors and teachers know the talents or potential of the child? 2. Is the child adequately developing unique talents or special aptitudes? 3. Is the child adequately developing common potential for educational learning? 4. Does the child feel good about his or her physical appearance? 5. Does the child feel good about performance related to a specic task, skill, or activity? 6. Does the child feel loved and valued by family and other signicant persons? 7. Does the child feel a sense of belonging to or acceptance by a positive group? 8. Does the child feel abandoned, lonely, isolated, and unwanted? 9. Does the child feel a sense of security and safety while at home? 10. Does the child feel a sense of security and safety while at school? 11. Does the child feel a sense of safety in his or her neighborhood, town, or village? 12. Has the child experienced psychological or physical abuse at home? 13. Has the child experienced psychological or physical abuse at school? 14. Is the child receiving adequate food intake and proper nutrition? 15. Does the child have an adequate home or adequate shelter for living? 16. Does the child have appropriate clothing for various weather conditions? Note. The relationship of assessment items to Maslows needs: self-actualization (items 1, 2, & 3); esteem (items 4 & 5); belongingness and love (items 6, 7, & 8); safety (items 9, 10, 11, 12, & 13); physiological (items 14, 15, & 16).

satisfaction of basic needs. Nevertheless, counselors, according to the culture or status of the child, may choose to alter or add to the language within items or add new items in order to make this inventory relevant to the conditions in which the child lives or functions. For example, we are sensitive to the condition that some child clients of the world may not attend school, may not have a traditional family, and may be homeless or runaway children. As regard to the use of the inventory, counselors would complete the 16 items based on information that is acquired from interviews with the child, interviews with signicant adults in the life of the child (e.g., teachers, parents, or community workers), or direct observation of the childs behavior (e.g., via play therapy or the childs interaction with others in a school or community setting). As convenient, the counselor should attempt to get multiple sources of information on the child before making premature conclusions about conditions or behaviors that suggest unfullled needs. In evaluating the responses on the completed inventory, the counselor would assess the number of item responses that suggest unfullled needs of the child as well as the nature and magnitude of the unfullled needs that are reected in the responses (e.g., unfullled physiological or safety needs being more important to address in counseling versus the self-actualizing need). The purpose of the completed inventory or questionnaire is to provide information that can be evaluated by the counselor for assessing the needs of the child client. It is not designed to yield a score for measuring the type and magnitude of unfullled needs, at least not at this point of its development.

Maslows Hierarchy of Basic Needs

19

A Counseling Case Based on Unfullled Needs The following description is based on a real counseling case from one of our school counseling experiences. The case is presented to demonstrate how a counselor can take an inappropriate direction of overly focusing on the clients feelings and, thus, eventually having to redirect the counseling focus and intervention to client needs, that is, when it becomes evident that the clients problem has more to do with needs than feelings:

Bobby, age 13, was a poor, African-American male from a small town in the USA. He was referred to counseling because of a decline in academic performance and school attendance. His mother was a single parent who had a very limited income. Even more, she had three additional younger offspring to feed and care for. The counselor began the relationship by employing Carl Rogerss client-centered therapy with Bobby in an attempt to allow him the freedom to talk about whatever concerned him. The counselor continually focused on reecting feelings and content of the clients responses, but soon realized that Bobby had become much less talkative after two counseling sessions. During the third session, Bobby constantly looked down at his clasped hands with a disposition of disinterest, while the counselor restated the same comment three times as a Rogerian reection of Bobbys nonverbal behavior: It seems you dont have much to talk about today. After a failure to get Bobby to open up, the counselor changed the orientation and simply asked him, What can I do to help you today? After this question, Bobby alertly raised his head and looked up at the counselor as if the right chord of a musical instrument had been struck. After a brief pause with apparent contemplation, the client commented, I need shoes, clothes, eyeglasses, and a job. Bobby used the word need, suggesting that he knew what his problem was and what he needed in order to x it. After explaining his self-perceived problem, it became evident to the counselor that Bobby did not want to go to school because other children laughed at his worn clothing and ragged shoes with holes in the soles. Moreover, Bobby stated that he could not read schoolwork well because he needed eyeglasses and his mother could not afford to buy them.

Commentary on the Case of Bobby In the counseling case of Bobby, the clients problem or concern suggested a physiological need for clothing and eyeglasses and a need for belongingness because of rejection by school peers who laughed at Bobbys clothing or dress. Moreover, Bobby suffered diminished self-esteem because of (a) his physical appearance that was related to the lack of acceptable clothing and (b) his inability to perform adequately in school which was related to poor vision or a lack of eyeglasses. Bobby began to attend school regularly after the counselor was successful in helping him to fulll self-perceived and real needs, that is, through securing eyeglasses from social services; nding an after-school, part-time job; and acquiring fashionable and nearly new clothing from a charitable effort. The after-school job provided a sense of nancial adequacy and positive pride for Bobby and served as a means of nancially assisting him to meet some of his basic needs of livingsuch as buying clothes, school supplies, and school lunch.

20

Harper, Harper, and Stills

Emotional Abandonment: Assessing Needs for Belongingness and Love Difculty or inability to meet basic needs is not necessarily limited to poor children or children from low-income families, such as in the case of Bobby. There is research on children from middle-class or wealthy families who have killed other children or killed themselves primarily because of an overwhelming feeling of emotional abandonment by their parents or because of constant psychological abuse and emotional rejection by parents and peers (Albayrak-Kaymak, 1999; Hoffman, 1996; Richards, 1999). In some cases, emotional abandonment and abuse by parents have led to severe psychological pain and hurt that have sometimes been expressed in the distorted impulse of a child or adolescent to hurt others and/or hurt self (Harper & Ibrahim; 1999; Hoffman, 1996; Richards, 1999). In the case of suicidal thoughts or acts, Richards (1999) surveyed 100 psychotherapists of suicidal patients from intact families. Employing questionnaires and follow-up interviews, Richards found that parental, emotional abandonment during childhood had an impact on suicidal thoughts, impulses, and acts of adult patients in therapy. Suicidal patients indicated that they frequently perceived their parents (both fathers and mothers) as rejecting, abusing, indifferent, domineering, demanding, aggressive, and even cruel at timessigns of emotional abandonment. These adult perceptions by patients regarding their childhood relationships with their parents suggest unfullled needs for belongingness, love, and esteem. These unlled needs of childhood carried over into adult relationships, wherein continued experiences of rejection, loss, and abandonment, according to Richards, served to trigger an actual suicide act by some patients. COUNSELING STRATEGIES AIMED AT CHILD NEED-FULFILLMENT This section presents counseling strategies and actions that may be employed to assist child clients in meeting their basic human needs as described by Maslow (1970). Recommended counselor strategies and actions are presented below, based on Maslows ve basic human needs: Self-Actualization (Need to Grow and Develop Ones Common and Unique Potential) 1. Counselor consultation on the school curriculum in ways that will provide curricular opportunities for children to express and actualize their natural talents and potential 2. The development of youth programs in the school and the community (during school hours, after school, and during the summer); programs that provide opportunities for children to develop talents in academics,

Maslows Hierarchy of Basic Needs

21

3. 4. 5.

6.

athletics, music, art, writing, public speaking, and other areas of talent development Counselor consultation with teachers and parents in helping them to facilitate the development of the potential and abilities of children Assessment/testing of a childs aptitudes and vocational interests Career guidance and career education for the purpose of exposing the child to career opportunities and the necessary training or education for specic careers Acquisition of social services and employment opportunities for poor parents so that their children will not be used as a source of income for the family; especially in developing countries and poor communities in developed countries where children are sometimes forced to bypass schooling or formal education in order to work and help their family earn income Esteem (Self-Esteem and Esteem from Others)

1. The counselors use of self-esteem assessment techniques or instruments, if these are available and culturally appropriate 2. The counselors employment of self-esteem-building counseling skills or strategies such as role modeling, role playing, approval, reassurance, encouragement, and various methods of positive reinforcement for a childs improvements and achievements 3. The counselors development of self-esteem-enhancement programs within the school, community, or village (programs to award and honor child achievements) 4. The counselors consultation and training with parents related to developing self-esteem in their children, especially parents who may be intentionally or unintentionally indifferent, insensitive, abusive, and demeaning to their children Belongingness and Love (Need to Belong to and Feel Loved by a Group) 1. Counseling efforts that focus on children who are psychologically withdrawn and ignored for the purpose of getting them involved in positive activities and groups 2. Family counseling that focuses on building or rebuilding parent-child bonding as well as facilitating mutual love and respect among family members 3. Counselor consultation and training with parents and other family members in order to help persons to learn how to express appreciation, forgiveness, love, and warmth within the family vis-` a-vis patterns of negative emotions and responses

22

Harper, Harper, and Stills

4. The counselors use of group counseling and play therapy with children for both diagnosis and therapy as related to the childs need for belongingness and love

Safety Needs (Need for Security, Stability, Protection, and Freedom from Fear or Constant Anxiety) 1. The development of peer mediation groups in schools and communities for the purpose of helping to resolve angry conicts between and among children before these disputes lead to violence 2. The establishment of preventive group guidance in schools, religious groups, and communities in order to present information to prevent bullying, gang violence, psychological harassment, sexual harassment, violent crime, and child ghts 3. The counselors consultation with government and business to develop safe havens for children who are exposed to homelessness, abuse, violent crime, terrorism, or violent war

Physiological Needs (Bodys Need for Food, Water, Oxygen, Optimal Temperature, and Sleep) 1. The counselors acquisition of social services and resources to help children and their families to meet their basic physiological needs (e.g., need for adequate food, shelter, and clothing) 2. The counselors referral of families and children to private and government agencies that provide resources and services related to fullling family and child basic needs 3. The counselors consultation with families on the topic of survival skills, proper nutrition, acquisition of social services and resources, nancial management, employment and income, and family problems that interfere with need-fulllment (e.g., alcoholism, other drug abuse, and addictive gambling) 4. The counselors assistance in securing nancial support and jobs in order to help families and their children to meet basic needs of living

CONCLUSION Throughout the world, there are children who cannot adequately satisfy basic needs of life, even at the lowest levels of need for physiological maintenance and safety. By the same token, there are children who may never rise to the level of their

Maslows Hierarchy of Basic Needs

23

natural ability or potential to self-actualize, that is, because of a number of reasons, including a lack of protection, love, and esteem, or a lack of opportunities to acquire a general education or to learn and develop a natural talent. Therefore, throughout the world and across cultures, the primary challenge and focus of counselors who work with children should be to identify children who are in extreme need and to help these young clients to meet their basic needs in order to grow and develop to the highest level or their innate potential. In other words, the counselor focuses on helping children to meet their basic needs within their culture and, thus, to move up Maslows need hierarchy toward self-actualization. Across cultures and within cultures, no child should be intentionally deprived of basic need-fulllment and the right to develop his or her talent because of a lack of access to resources and opportunity or, even more, because of that childs status in society, for example, because of the childs ethnic identity, religious afliation, gender, or state of poverty. In an article on justice for all human beings, Mays (2000) states that, No one should have their future, their health, or their well-being compromised for reasons of class, gender, national origin, physical and psychological abilities, religion, or sexual orientation, or as a result of unfair distribution of resources (p. 326). REFERENCES

Albayrak-Kaymak, D. (1999). Internalizing or externalizing: Screening for problem youth. International Journal for the Advancement of Counselling, 21, 125137. American Psychiatric Association. (1994). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV), (4th ed.). Washington, DC: Author. Anastasi, A., & Urbina, S. (1997). Psychological testing (7th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall. Becker, J. V., & Bonner, B. (1998). Sexual and other abuse of children. In R. J. Morris & T. R. Kratochwill (Eds.), The practice of child therapy (pp. 367389), (3rd ed.). Boston: Allyn and Bacon. Brundtland, G. H. (2000). Outstanding issues in the international response to HIV/AIDS: The WHO (World Health Organization) perspective. Paper presented at the XIII International AIDS Conference, Durban, South Africa. Colvin, G., Tobin, T., Beard, K., Hagan, S., & Sprague, J. (1998). The school bully: Assessing the problem, developing interventions and future research directions Journal of Behavioral Education, 8, 293319. Daftuar, C. N., & Sharma, R. (1998). Beyond Maslow: An Indian perspective of need-hierarchy. Journal of the Indian Academy of Applied Psychology, 24, 18. DeLay, T. (2000). Fighting for children. American Psychologist, 55, 10541055. Gibson, R. L., & Mitchell, M. H. (1999). Introduction to counseling and guidance (5th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Merrill. Gibson, R. L., Mitchell, M. H., & Basile S. K. (1993). Counseling in the elementary school: A comprehensive approach. Boston: Allyn and Bacon. Glasser, W. (1965). Reality therapy. New York: Harper & Row. Glasser, W. (2000). Reality therapy in action. New York: HarperCollins. Gullotta, T. P., Adams, G. R., & Montemayor, R. (1995). Substance misuse and adolescence. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. Hagerty, M. R. (1999). Testing Maslows hierarchy of needs: National quality-of-life across time. Social Indicators Research, 46, 249271.

24

Harper, Harper, and Stills

Harper, F. D. (1998, August). Roles and challenges of counseling professionals for the new millennium. Paper presented at the Annual Conference of the International Association for Counselling, Paris, France. Harper, F. D., & Deen, N. (2003). The international counseling movement. In F. D. Harper & J. McFadden (Eds.), Culture and Counseling: New Approaches (pp. 147163). Boston, MA: Allyn and Bacon. Harper, F. D., & Ibrahim, F. (1999). Violence and schools in the USA: Implications for counseling. International Journal for the Advancement of Counselling, 21, 349366. Harper, F. D., & Stone, W. O. (1986). Transcendent counseling: Toward a multicultural approach. International Journal for the Advancement of Counselling, 9, 251263. Harper, F. D., & Stone, W. O. (1999). Transcendent counseling (TC): A theoretical approach for the year 2000 and beyond. In J. McFadden (Ed.), Transcultural counseling: Bridging cultures (pp. 83108), (2nd ed.). Alexandria, VA: American Counseling Association Press. Harper, F. D., & Stone, W. O. (2003). Transcendent counseling: An existential, cognitive-behavioral theory. In F. D. Harper & J. McFadden, J. (Eds.), Culture and counseling: New approaches (pp. 233251). Boston, MA: Allyn and Bacon. Hickson, J., & Mokhobo, D. (1992). Combatting AIDS in Africa: Cultural barriers to effective prevention and treatment. Journal of Multicultural Counseling and Development, 20, 1112. Hoffman, A. M. (Ed.). (1996). Schools, violence, and society. Westport, CT: Praeger. Israelashvili, M. (1999). Adolescents help-seeking behaviour in times of community crisis. International Journal for the Advancement of Counselling, 21, 8796. Johnson, D. S. (1998). Community solutions to violence: A Minnesota managed care action plan. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 14, 9397. Kaslow, F. W. (2001). Families and family psychology at the millennium. American Psychologist, 56, 3746. Kritsberg, W. (1985). The adult children of alcoholics syndrome. Pompano Beach, FL: Heath Communications. Marshall, A. (2001, June). Life-career counselling issues for youth in coastal and rural communities: The impact of economic, social and environmental restructuring. Paper presented at the Annual Conference of the International Association for Counselling, Lonavla-Mumbai (Bombay), India. Maslow, A. H. (1968). Toward a psychology of being (2nd ed.). New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold. Maslow, A. H. (1970). Motivation and personality (2nd ed.). New York: Harper and Row. Mays, V. M. (2000). A social justice agenda. American Psychologist, 55, 326327. McConnell, R. A., & Sim, A. J. (1999). Adjustments to parental divorce: An examination of the differences between counselled and non-counselled children. British Journal of Guidance and Counselling, 27, 245257. Mohapatra, K., & Rath, P. K. (2001, June). The teenage victims of the supercyclone in Orissa: Some therapeutic interventions. Paper presented at the Annual Conference of the International Association for Counselling, Mumbai, India. Nicholson, J. A., & Golsan, G. (1983). The creative counselor. New York: McGraw-Hill. Ntoi, V. (2001, June). HIV/AIDS in Lesotho: De-Constructing death to cope with loss. Paper presented at the Annual Conference of the International Association for Counselling, Mumbai, India. Richards, B. M. (1999). Suicide and internalised relationships: A study from the perspective of psychotherapists working with suicidal patients. British Journal of Guidance and Counselling, 27, 8598. Roy, J. (2001). Response to the earthquake in Gujarat by Five Rs (rapid response, rescue, relief, reconstruction and rehabilitation). Unpublished Report. Five Rs Group, New Delhi, India. Saigh, P. A. (1998). Posttraumatic stress disorder. In R. J. Morris & T. R. Kratochwill (Eds.), The practice of child therapy (pp. 390418), (3rd ed.). Boston: Allyn and Bacon. Shelby, J. S., & Tredinnick, M. G. (1995). Crisis intervention with survivors of natural disaster: Lessons from Hurricane Andrew. Journal of Counseling and Development, 73, 491497. Sizikova, T. (2000, May). Counseling in Russia. Paper presented at the Annual Conference of the International Association for Counselling, Thessaloniki, Greece. Stockton, R., Kaladow, J. K., & Garbelman, J. (2001, June). Meeting the challenges ahead: The development and history of international counseling. Paper presented at the Annual Conference of the International Association for Counselling, Lonavla-Mumbai (Bombay), India.

Maslows Hierarchy of Basic Needs

25

Tatar, M. (1998). Counselling immigrants: School contexts and emerging strategies. British Journal of Guidance and Counselling, 26, 337352. Thompson, C. L., & Rudolph, L. B. (1983). Counseling children. Monterey, CA: Brooks/Cole. Tobias, B. Q. (2001). A descriptive study of the cultural mores and beliefs toward HIV/AIDS in Swaziland, southern Africa. International Journal for the Advancement of Counselling, 23, 99 113. Vontress, C. E., & Epp, L. R. (2000). Ethnopsychiatry: Counseling immigrants in France. International Journal for the Advancement of Counselling, 22, 273288.

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- Behavioral Health ProfessionalsDocument5 pagesBehavioral Health ProfessionalsNoelle RobinsonPas encore d'évaluation

- Counseling Is The Activity of The Counselor, or A Professional Who Counsels People, Especially On Personal Problems andDocument1 pageCounseling Is The Activity of The Counselor, or A Professional Who Counsels People, Especially On Personal Problems andgheljoshPas encore d'évaluation

- Generalist Social Work Practice Framework Prepared By: Marietta M. LingvallDocument20 pagesGeneralist Social Work Practice Framework Prepared By: Marietta M. LingvallRuss Anne100% (1)

- CounselingDocument18 pagesCounselingXamira Anduyan CuizonPas encore d'évaluation

- Rights and Responsibilities in Behavioral Healthcare: For Clinical Social Workers, Consumers, and Third PartiesD'EverandRights and Responsibilities in Behavioral Healthcare: For Clinical Social Workers, Consumers, and Third PartiesPas encore d'évaluation

- Multicultural Counseling Applied To Vocational RehabilitationDocument16 pagesMulticultural Counseling Applied To Vocational RehabilitationMichele Eileen Salas100% (1)

- Definition of Counselling and PsychotherapyDocument6 pagesDefinition of Counselling and PsychotherapyLeonard Patrick Faunillan BaynoPas encore d'évaluation

- SW 3020 Biopsychosocial Assessment-Final RevisedDocument18 pagesSW 3020 Biopsychosocial Assessment-Final Revisedapi-286703035Pas encore d'évaluation

- Alcohol and YouthDocument9 pagesAlcohol and YouthChrist AngelinaPas encore d'évaluation

- Methods of Social WorkDocument2 pagesMethods of Social WorkDavid Johnson100% (1)

- Social Work CounselingDocument2 pagesSocial Work CounselingDeo JonesPas encore d'évaluation

- Advocacy Is An ImportantDocument40 pagesAdvocacy Is An ImportantPramusetya SuryandaruPas encore d'évaluation

- Worksheet For Overcoming ResistanceDocument3 pagesWorksheet For Overcoming ResistanceDeepak GoswamiPas encore d'évaluation

- College Students and DepressionDocument6 pagesCollege Students and Depressiontink0791Pas encore d'évaluation

- Group ProposalDocument23 pagesGroup Proposalapi-251294159Pas encore d'évaluation

- The Prevalence of Substance Use and Other Mental Health Concerns Among American AttorneysDocument7 pagesThe Prevalence of Substance Use and Other Mental Health Concerns Among American AttorneysDavid AndreattaPas encore d'évaluation

- Stage 5: Final Stage-Consolidation and TerminationDocument7 pagesStage 5: Final Stage-Consolidation and Terminationadi mawaridz100% (1)

- Therapeutic Recreation and Adventure TherapyDocument25 pagesTherapeutic Recreation and Adventure Therapyapi-255002053Pas encore d'évaluation

- Pdhpe Assessment Task Term 1 Drug Use in AdolescentsDocument10 pagesPdhpe Assessment Task Term 1 Drug Use in Adolescentsapi-463236687100% (2)

- Program Theory and Logic Models PDFDocument19 pagesProgram Theory and Logic Models PDFBrooke LindenPas encore d'évaluation

- Master of Social Work (MSW)Document2 pagesMaster of Social Work (MSW)diosjirehPas encore d'évaluation

- Critical Reflection EssayDocument7 pagesCritical Reflection EssaykjdwcPas encore d'évaluation

- Ethics For Substance Abuse CounselorsDocument4 pagesEthics For Substance Abuse CounselorsChe'gu JamalPas encore d'évaluation

- Estimating The Return On Investment For Boys Girls Clubs Univ of MI 20...Document28 pagesEstimating The Return On Investment For Boys Girls Clubs Univ of MI 20...WXYZ-TV Channel 7 DetroitPas encore d'évaluation

- Counseling Case PaperDocument5 pagesCounseling Case PaperDesiree Obtial LabioPas encore d'évaluation

- Comp SCH Counsel ModelDocument118 pagesComp SCH Counsel Modelapi-258938931Pas encore d'évaluation

- Social Care and the Law in Scotland: 11th Edition 2018D'EverandSocial Care and the Law in Scotland: 11th Edition 2018Pas encore d'évaluation

- Macro - CommunityDocument2 pagesMacro - CommunityFaranPas encore d'évaluation

- Values Definition - What Is Values?Document5 pagesValues Definition - What Is Values?Anshuman HarshPas encore d'évaluation

- Issues and Trends in GuidanceDocument20 pagesIssues and Trends in GuidanceChristian DilaoPas encore d'évaluation

- The People Living With HIV Stigma Index: BelizeDocument41 pagesThe People Living With HIV Stigma Index: BelizeEriKa Castellanos100% (1)

- Multicultural Counseling PortfolioDocument11 pagesMulticultural Counseling Portfolioapi-285240070Pas encore d'évaluation

- SW Scope of Pratice Health Dec 15 PDFDocument8 pagesSW Scope of Pratice Health Dec 15 PDFSheethal DeekshithPas encore d'évaluation

- Emotional and Psychological Aspects of Therapeutic CommunityDocument20 pagesEmotional and Psychological Aspects of Therapeutic CommunityAlexander RamosPas encore d'évaluation

- The Meaning of CounselingDocument3 pagesThe Meaning of CounselingChristine Rafael Castillo100% (1)

- Perception of Interviewees On CounselingDocument9 pagesPerception of Interviewees On CounselingηιφΗτ ωιζΗPas encore d'évaluation

- Integrated Group Treatment For People Experiencing Mental Health-Substance Use Problems, Kathleen SciaccaDocument14 pagesIntegrated Group Treatment For People Experiencing Mental Health-Substance Use Problems, Kathleen SciaccaKathleen Sciacca, MA - Sciacca Comprehensive Service Dev. Dual Diagnosis; Motivational Interviewing100% (1)

- 1 Journal PDFDocument12 pages1 Journal PDFRAFPas encore d'évaluation

- Counseling Theories - Strengths and WeaknessesDocument5 pagesCounseling Theories - Strengths and WeaknessesDAVE HOWARDPas encore d'évaluation

- Bipolar Disorder PaperDocument11 pagesBipolar Disorder Paperapi-351215725Pas encore d'évaluation

- Children Exposed To Violence: Caryn Brauweiler, LCSW Debbie Conley, LCSWDocument59 pagesChildren Exposed To Violence: Caryn Brauweiler, LCSW Debbie Conley, LCSWIman MuhammadPas encore d'évaluation

- Sucide Prevention HelpDocument4 pagesSucide Prevention Helpvipin tewariPas encore d'évaluation

- Counseling SkillsDocument10 pagesCounseling SkillsBrian SrotaPas encore d'évaluation

- Provide Counseling To PWUD and PWIDDocument16 pagesProvide Counseling To PWUD and PWIDMariam KiharoPas encore d'évaluation

- Drug Abuse Prevention StrategyDocument5 pagesDrug Abuse Prevention Strategyiulia9gavrisPas encore d'évaluation

- Social Work Supervision in Practice: The Commonwealth and International Library: Social Work DivisionD'EverandSocial Work Supervision in Practice: The Commonwealth and International Library: Social Work DivisionPas encore d'évaluation

- Foundations of Counseling and Psychotherapy: Evidence-Based Practices for a Diverse SocietyD'EverandFoundations of Counseling and Psychotherapy: Evidence-Based Practices for a Diverse SocietyPas encore d'évaluation

- Case StudyDocument12 pagesCase StudyRajesh MKPas encore d'évaluation

- Directive CounselingDocument33 pagesDirective Counselingeduard canares100% (1)

- S. R. Myneni, Political Science, Allahabad Law Publication, Faridabad (2008) P. 207Document2 pagesS. R. Myneni, Political Science, Allahabad Law Publication, Faridabad (2008) P. 207Shayan ZafarPas encore d'évaluation

- Apsy 603 Dual Relationship Assignment 4Document18 pagesApsy 603 Dual Relationship Assignment 4api-161848380100% (1)

- Family Counseling Center ProposalDocument2 pagesFamily Counseling Center ProposalEdna FatimaPas encore d'évaluation

- Counseling Theories Final PaperDocument11 pagesCounseling Theories Final Paperapi-334628919Pas encore d'évaluation

- Psychosocial Assessment Form1 PDFDocument4 pagesPsychosocial Assessment Form1 PDFWindiGameliPas encore d'évaluation

- Notes On PsychologyDocument14 pagesNotes On PsychologybinduannPas encore d'évaluation

- AKA Erik Homburger EriksonDocument34 pagesAKA Erik Homburger EriksonvinwaleedPas encore d'évaluation

- Group Therapy Center For Mental Health by SlidesgoDocument19 pagesGroup Therapy Center For Mental Health by SlidesgoFestus sumukwoPas encore d'évaluation

- Schizophrenia Final PaperDocument6 pagesSchizophrenia Final Paperchad5844Pas encore d'évaluation

- ICPS DCPU SAA NotesDocument6 pagesICPS DCPU SAA NotesDistrict Child Protection Officer VikarabadPas encore d'évaluation

- Quantitative Annotated BibliographyDocument2 pagesQuantitative Annotated Bibliographyapi-310552722Pas encore d'évaluation

- Social Studies S.B.ADocument20 pagesSocial Studies S.B.ASashi Sarah Robin70% (33)

- Proposed CCSD Gender Diverse PolicyDocument8 pagesProposed CCSD Gender Diverse PolicyLas Vegas Review-JournalPas encore d'évaluation

- Teaching and Learning in Nature: Let's Go Outside!Document2 pagesTeaching and Learning in Nature: Let's Go Outside!simonettixPas encore d'évaluation

- Ateeq CVDocument4 pagesAteeq CVNasir AhmedPas encore d'évaluation

- College English and Business Communication 10th Edition by Camp Satterwhite ISBN Test BankDocument55 pagesCollege English and Business Communication 10th Edition by Camp Satterwhite ISBN Test Bankgladys100% (20)

- Peta MindaDocument9 pagesPeta Mindalccjane8504Pas encore d'évaluation

- 5e's ActivitiesDocument2 pages5e's ActivitiesJoyae ChavezPas encore d'évaluation

- ReflectionDocument3 pagesReflectionAngela Joyce MartinPas encore d'évaluation

- WHS Intro To Philosophy 2008 Dan TurtonDocument111 pagesWHS Intro To Philosophy 2008 Dan TurtonDn AngelPas encore d'évaluation

- Human Relations MovementDocument37 pagesHuman Relations MovementAlain Dave100% (2)

- Imagery Within J Alfred PrufrockDocument3 pagesImagery Within J Alfred PrufrockJessicaNosalskiPas encore d'évaluation

- Dance Movement TherapyDocument5 pagesDance Movement TherapyShraddhaPas encore d'évaluation

- Levi Case Study: Harvard Case StudyDocument3 pagesLevi Case Study: Harvard Case StudyDeepanshu Wadhwa0% (1)

- MPA LeadershipDocument3 pagesMPA Leadershipbhem silverioPas encore d'évaluation

- The Most Important Elements in Japanese CultureDocument13 pagesThe Most Important Elements in Japanese CultureKevin Bucknall100% (3)

- (MCP1617) Qustionnaire-GPoA Concepcion, JerichoDocument20 pages(MCP1617) Qustionnaire-GPoA Concepcion, JerichoCep PyPas encore d'évaluation

- Mock InterviewDocument4 pagesMock Interviewsukumaran321Pas encore d'évaluation

- GFPP3113 Politik Ekonomi AntarabangsaDocument11 pagesGFPP3113 Politik Ekonomi AntarabangsaBangYongGukPas encore d'évaluation

- Licensure Requirements 2016 EditionDocument168 pagesLicensure Requirements 2016 Editionprivatelogic100% (2)

- Leasson Plan 4Document31 pagesLeasson Plan 4Eka RoksPas encore d'évaluation

- Rodowick Impure MimesisDocument22 pagesRodowick Impure MimesisabsentkernelPas encore d'évaluation

- 11 Subiect+baremDocument3 pages11 Subiect+baremprobulinaPas encore d'évaluation

- An Open Letter To President Benson and The Board of RegentsDocument6 pagesAn Open Letter To President Benson and The Board of RegentsWKYTPas encore d'évaluation

- Direct Financial CompensationDocument36 pagesDirect Financial CompensationKatPalaganas0% (1)

- Institutional PlanningDocument4 pagesInstitutional PlanningSwami GurunandPas encore d'évaluation

- Detailed Lesson Plan in Grade 9Document6 pagesDetailed Lesson Plan in Grade 9Hero-name-mo?Pas encore d'évaluation

- PSYCH-ASSESSMENT-RRL-and-QUESTIONS FinalDocument4 pagesPSYCH-ASSESSMENT-RRL-and-QUESTIONS FinalRomilenesPas encore d'évaluation

- PIBC LogBook Guide&Samples Jun2012Document12 pagesPIBC LogBook Guide&Samples Jun2012GOKUL PRASADPas encore d'évaluation

- Psychology and ScienceDocument4 pagesPsychology and ScienceSrirangam Bhavana 16PJW019100% (1)