Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

The Wonder-Breading of Our Country: by Margo Adair & Sharon Howell

Transféré par

Carlos Rafael PitirreTitre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

The Wonder-Breading of Our Country: by Margo Adair & Sharon Howell

Transféré par

Carlos Rafael PitirreDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

THE WONDER-BREADING OF OUR COUNTRY By Margo Adair & Sharon Howell

Excerpted from Subjective Side of Politics a Tools for Change pamphlet

Power operates on many levels the political, the institutional, the personal. Power is not an abstraction. It is given shape and texture by the land, the people and their culture. To restore our connection to nature enabling us to live in harmony with the earth and one another, we have to look at how power, politics and place have woven a troubled history for us to inherit. The history of the United States raises fundamental questions of human identity and points to the necessity of creating a new sense of self arising from respect for diversity, the honoring of cultural integrity and the re-creation of community made possible as we regain our connection to place and past. In the U.S. the opening of opportunity to increase our standard of living has been made possible by racism. Racism is woven into our every assumption. Whether or not we are engaging with people of color, it is a part of us, just as sexism doesnt evaporate when women are not present. Race and class are deeply entwined in our experience. Because of the central role that race and class play in the economic and social development of our country, we need to unravel how they are each used as a means of control. Talking about race and class makes us all uncomfortable. This is especially true for those of us of European descent. Looking at these issues reminds us of a painful past. At some level we are aware that whatever comfort and security we have in our lives has been made possible by the genocide of Native Peoples and the stealing of their land, the enslavement of African Americans, the illegal

annexation of Northern Mexico, the use of Chinese labor in building the West while denying them the right to own land, and the abuse of all working people. These truths are troubling. When we allow ourselves to think about them, they create a vague feeling of guilt for a situation we didnt create and feel powerless to change. For most of us, its easier to ignore these issues and go on with our lives. We dont realize denying our past not only keeps us from understanding the horror of our history, but it also hides from us the lives and values of those who struggled against these injustices. Their legacy points the way to creating a new future. Race is a political category. The term white was established as a legal concept after Bacons Rebellion in 1676 to separate the indentured servants of European and African heritage who united against the colonial elite. Prior to this time, most Africans and Europeans were able to look toward a time when they would be free from the harshness of servitude. After the rebellion, however, slavery became the permanent condition for Africans. On the other hand, indentured Europeans, at least in theory, could work their way out. White people, institutionalized in the legal system were given claim to a future, while Africans were cast as less than human. The creation of white meant giving privileges to some, while denying them to others with the justification of biological and social inferiority. Resources attained as the result of racist policies made upward mobility an exclusive white privilege. People of color provided the labor for the

most back-breaking and dangerous work needed for developing the country, thus forming an underclass from which all whites benefited. This is not to say that all Americans of European descent accepted these benefits. We have a long tradition of women and men who dedicated their lives to the struggle for justice. It is precisely because they offer us a vision of our power to change things that they are hidden from us. Almost every American knows the song Amazing Grace, yet most of us are unaware it was written by a captain of a slave ship who became a leading abolitionist. Few of us know the names of Wendell Phillips or William Lloyd Garrison, whose writing and speaking drove the issue of slavery into the center of American politics. While we are taught the names of Civil War battles, we never learn about the Southerners who voted against secession. In Alabama thirtynine percent of the white men voted No! How much of this was a result of tactics like those of the anti-slavery womens organization that would ring meeting houses, beating on pots and pans to drown out the speeches of pro-secessionists? Nor is it to say that all Americans of European descent were of the same class. In fact, those of the working, middle and owning classes have played significantly different roles in maintaining the institution of racism. Since the beginning, the owning class has used the lower classes to enforce racism. To improve their lot, lower class whites were the ones who killed native Americans and Mexicans in the move west. They also were the overseers, administering punishment to

any African who rebelled. People in the lower class were responsible for the terrorism and random violence necessary to maintain the system. These whites, powerless in relation to the power brokers, gained a sense of personal power over people of color. Obviously not solving the injustice done to them, they ameliorated their pain with a sense of superiority and more material advantages. This dynamic continues today. The most intense expressions are in the popularity of the KKK, and other white supremacist groups, including some who actually call themselves the Identity Movement. lncidents of violence against people of color in neighborhoods, subways, parks and college campuses are on the rise. The most insidious racism is the silent acceptance of it by the vast majority, creating the climate that sanctions inhumanity. While the owning and middle classes look down upon or ignore such brutal behavior, or elevate it to valor in the conquest of the West, it is this very activity that enforces their positions of power and privilege. The upper classes indulge in the fantasy that they are not the ones who are racist, when, in fact, it is they who create the policies that maintain the institutional inequities upon which their wealth depends. The Colonial elite created white as an identity of superiority for people of European descent. If those of the lower classes were to look above them, the prerequisite of upward mobility was to deny their own particular cultural heritage, family ties, and loyalty to place, trading these for the idea that they were just the same as those on the topwhite, male, Protestant, heterosexual, able-bodied and serious. No longer Germans, Italians, Finns or Swedes, they were whites. Each wave of immigrants had to wait their turn to become white, enduring ridicule and discrimination as they filled the space between white and the underclass. This is the wonderbreading of America. Cultural ties were

traded in for a piece of the American pie. This trade is made at a tremendous cost. Giving up our ethnic identities, we lose our emotional security and our sense of self. We are no longer rooted in a community and a way of life. The only way to regain respect is by displaying our wealth, from the fanciest car to the biggest house. Consumerism is more than greed. It is the frenzied effort to belong. Our identity has become what we own. The richness of our various cultural heritages has been replaced by a white identity whose roots are not in a history of a people with a particular place, culture and language. White identity was born out of the establishment and maintenance of privilege. Identity is a persons reference point, telling us where we come from, where we are going and with whom our source of pride and loyaltyin short, our sense of who we are. Clearly, an identity based on white is fraught with problems. It has no culture, thus leading to the rip-off of other peoples cultures to fill the void. It obscures the past and the values of those who fought against dehumanization and exploitation. Yet those of European ancestry do identify as white. This is manifested in the working class as a sense of superiority coupled with the fear that they will lose what little privilege theyve managed to acquire a fear that is intensifying as the economy squeezes them out. For the middle classes, white identity is based on maintaining their innocence. Overt violence is much less fashionable. Therefore the worst epithet that a middle class white person can be given is that s/he is racist. This calls into play an unconscious loyalty that pervades all interactionsa white bonding. When racism is charged, the response is not to look at what happened and the impact of actions, but to defend the innocent intent of the person behind them.

White identity here is about protecting their own, not about justice. This dynamic was made clear in the Undoing Racism Workshop we attended a while back. An African American man was giving a presentation on so-called heroes in our history. He got to Andrew Jackson and described the Trail of Tears in which one quarter of the Cherokee people died. A women who originally had introduced herself as one of those white, middle class, suburban types spoke up defending Jackson, saying everybody makes mistakes. We must ask why was this her first reaction? She wants to work against racism or she would not have committed a full weekend to attend the workshop. Yet she identified with Jackson, not with the Cherokee people. Her reaction diverted attention from what this landgrab made possible for whites. This serves the dual purpose of getting each other off the hook and keeping out of view both the injustice and the privilege it provides. It is deeply ingrained in the white middle class first and foremost to identify with and defend one another. Once again the power taboo is operative: the status quo is maintained and the experience of the locked out is kept invisible. Obviously, these dynamics keep racism in place. To get rid of it, the institutions themselves must be changed. But to do that successfully, we must rid ourselves of white identity and embrace our true cultural identities. For many of us, this will be an opportunity to come to terms with the fact that we are the children of many different and distinct cultures African, Irish, Jewish, Chippewa, Spanish, Armenian, Chinese, Syrian, Hungarian.... In the process of reclaiming our ancestors we can learn something about the complexity of our American identity and the importance of consciously deciding the values and traditions we want to pass on to the next generation. The lives and values of those who refused to accept white privilege and who resisted expansion

and exploitation are an important legacy from which we can rebuild our loyalty to family, place and past. Today, the entanglement of race, class and identity is even more difficult to unravel. In the past, the homogenization of whites was made possible by the expanding American pie. Now the pie is shrinking. At the very moment when the locked out succeeded in getting legislation to guarantee them a piece, everything had been doled out. The result is that the reality of power and privilege is even more obscured. The actual conditions of all women and men of color is worse than before the civil rights movements. For example, there is now a greater disparity between the incomes of whites and people of color and between men and women than before the movements. Yet this reality is hidden behind the faces of the few visible tokens who have positions of power. This visibility fosters the idea that anyone can still make it. For the first time, people who knew survival depended on sticking together are now encouraged to think that their security rests in breaking or hiding ties to the community. Community bonds get cut in the desperate dash to make it into the middle class. Now, people of color, like the whites before them, engage in the homogenization process, relinquishing ties to family, place and past. Even those of us who have managed to retain some ties to family, place, and past, often find ourselves in a sterile atmosphere of homogenized, middle class norms. Virtually every situation that brings together different peoplefrom the corporate workplace to the political coalition has its parameters of appropriate behavior set by the wonder-breading process. Power relationships are invisible, conflict taboo, accountability to anything other than our narrow, prescribed function is non existent. The texture of our experience is smoothed over and replaced by an atmosphere that focuses on personality

and taking care of individual feelings, rather than looking at the social conditions out of which they arise. The middle class manageskeeps everything running smoothly and makes us feel better while accepting things as they are. Their role is to keep class antagonisms invisible. We each are viewed as isolated individuals, devoid of heritage, responsibilities and relationships. This focus is played out in the continual judging of our own and one anothers acceptability. So we always have to prove ourselves. Somehow, were never quite good enough. Competition rules, obscuring everyones integrity. Even the white, male, Protestant, middle class, heterosexual, able-bodied, serious person, sometimes has his doubts. Principle doesnt even enter the scene. The middle class, who are there by virtue of relinquishing their heritage, have created a culture of estrangement characterized by alienation, isolation and constantly having to be on guard. Everyone is individually free to do their own thing. Yet we are social beings in interrelationshipswhether we acknowledge them or not. This means we cannot be supportive of one another without mutual accountability. The middle class views accountability as constricting, when, it is the very thing that enables us to trust one another. In the name of respecting freedom, we cannot challenge one another. If we cant talk about new ways of being together, how are we ever going to create them?

Tools for Change, 1989

PAMPHLETS FROM Tools for Change: The Subjective Side of Politics Breaking Old Patterns Weaving New Ties: Alliance Building

READERS COMMENTS: This makes visible the hidden barriers that block our ability to work together effectively. Its full of concrete strategies for creating a context that welcomes everyone's contributions. --Sister Guadalupe Guajardo A very important piece of work for both emerging and established organizations. Although it's good for individuals, it's best to study it collectively and use it for training programs. --Richard Moore For a copy of the pamphlets send $10. for one and $15 for both to 2408 East Valley, Seattle, CA 94114 or order on line.

Tools for Change offers training, consulting, and facilitation services on justice issues and the bringing together of history, heart, spirit, values and. Vision. See website: www.toolsforchange.org write: info@toolsforchange.org or call: 206 329-2201

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- Stephen Jones - Secrets of TimeDocument237 pagesStephen Jones - Secrets of TimeKld Brn86% (7)

- Driven toward Madness: The Fugitive Slave Margaret Garner and Tragedy on the OhioD'EverandDriven toward Madness: The Fugitive Slave Margaret Garner and Tragedy on the OhioÉvaluation : 5 sur 5 étoiles5/5 (1)

- Workbook for White Fragility: Why It's So Hard for White People to Talk About Racism by Robin DiAngeloD'EverandWorkbook for White Fragility: Why It's So Hard for White People to Talk About Racism by Robin DiAngeloPas encore d'évaluation

- Cabeza de Baca-Moral Renovation-Tijuana RoleDocument232 pagesCabeza de Baca-Moral Renovation-Tijuana RoleJosué BeltránPas encore d'évaluation

- Beyond Black Only - Bonding Beyond Race by Bell HooksDocument4 pagesBeyond Black Only - Bonding Beyond Race by Bell HooksPovi-TamuBryantPas encore d'évaluation

- Adrienne Davis Don't Let Nobody Bother Yo' PrincipleDocument12 pagesAdrienne Davis Don't Let Nobody Bother Yo' PrinciplegonzaloluyoPas encore d'évaluation

- Black Power and the American Myth: 50th Anniversary EditionD'EverandBlack Power and the American Myth: 50th Anniversary EditionÉvaluation : 5 sur 5 étoiles5/5 (1)

- Accuracy of Eye Witness TestimonyDocument5 pagesAccuracy of Eye Witness Testimonyaniket chaudhary100% (1)

- "The Black Immigrants and Politics of Race" and "Holding Aloft The Burner of Ethiopia" 1Document6 pages"The Black Immigrants and Politics of Race" and "Holding Aloft The Burner of Ethiopia" 1Gladys vidzoPas encore d'évaluation

- Class War, Not Race WarDocument2 pagesClass War, Not Race WarJerkFace66Pas encore d'évaluation

- Anthro Reading #60Document3 pagesAnthro Reading #60Jennifer SamsonPas encore d'évaluation

- White Privilege Is A Division Among The Race of Whites and The Rest of The Opposing RaceDocument7 pagesWhite Privilege Is A Division Among The Race of Whites and The Rest of The Opposing Raceapi-273412332Pas encore d'évaluation

- Study Group 7 - White Supremacy and Black LiberationDocument50 pagesStudy Group 7 - White Supremacy and Black LiberationIsaacSilverPas encore d'évaluation

- Article WhiteAmericans01 03Document9 pagesArticle WhiteAmericans01 03SusanPas encore d'évaluation

- Analysisessay 2Document5 pagesAnalysisessay 2api-351669208Pas encore d'évaluation

- Race: The Power of An IllusionDocument6 pagesRace: The Power of An IllusionEluru SwathiPas encore d'évaluation

- White Privilege and White Guilt 1Document19 pagesWhite Privilege and White Guilt 1Jeff SablePas encore d'évaluation

- Aaaaaa PDFDocument41 pagesAaaaaa PDFRichie HuamanPas encore d'évaluation

- Indigenous Peoples and Black People in CanadaDocument32 pagesIndigenous Peoples and Black People in CanadaBop GoesBop100% (2)

- EBSCO FullText 2023 12 26Document14 pagesEBSCO FullText 2023 12 26RitikaPas encore d'évaluation

- Alcoff - What Should White People DoDocument21 pagesAlcoff - What Should White People DoAytanGuluzadePas encore d'évaluation

- This Violent Empire: The Birth of an American National IdentityD'EverandThis Violent Empire: The Birth of an American National IdentityPas encore d'évaluation

- Black Feminist ThoughtDocument7 pagesBlack Feminist ThoughtGerald Akamavi100% (2)

- Racist Love Chin and ChanDocument7 pagesRacist Love Chin and ChanCynthia FongPas encore d'évaluation

- Race: The Power of An IllusionDocument8 pagesRace: The Power of An IllusionEluru SwathiPas encore d'évaluation

- Inventing America's Worst Family: Eugenics, Islam, and the Fall and Rise of the Tribe of IshmaelD'EverandInventing America's Worst Family: Eugenics, Islam, and the Fall and Rise of the Tribe of IshmaelÉvaluation : 5 sur 5 étoiles5/5 (2)

- We Have Overcome: An Immigrant’s Letter to the American PeopleD'EverandWe Have Overcome: An Immigrant’s Letter to the American PeoplePas encore d'évaluation

- W11 AN405 TallBear - Caretaking Relations Not American DreamingpdfDocument18 pagesW11 AN405 TallBear - Caretaking Relations Not American DreamingpdfS WuPas encore d'évaluation

- Bandits, Misfits, and Superheroes: Whiteness and Its Borderlands in American Comics and Graphic NovelsD'EverandBandits, Misfits, and Superheroes: Whiteness and Its Borderlands in American Comics and Graphic NovelsPas encore d'évaluation

- When Doves Cry Shell .1-2: Impact ExtensionDocument5 pagesWhen Doves Cry Shell .1-2: Impact ExtensionMetelitswagPas encore d'évaluation

- Deconstructing Frameworks of TruthDocument25 pagesDeconstructing Frameworks of TruthDiggzBeatzPas encore d'évaluation

- White SupremacismDocument25 pagesWhite SupremacismIván100% (1)

- Zainab Amadahy and Bonita Lawrence PDFDocument32 pagesZainab Amadahy and Bonita Lawrence PDFMike WilliamsPas encore d'évaluation

- Ethnocentrism MaterialDocument2 pagesEthnocentrism MaterialPiyali MitraPas encore d'évaluation

- Uyematsu-Emergence Yellow PowerDocument10 pagesUyematsu-Emergence Yellow Powerapi-581842870Pas encore d'évaluation

- Some Black Men May Be Jerks But Black Ma PDFDocument35 pagesSome Black Men May Be Jerks But Black Ma PDFSamori Reed-BandelePas encore d'évaluation

- Ambiguity of Race FinalDocument11 pagesAmbiguity of Race Finalapi-223037220Pas encore d'évaluation

- Essay ModificationDocument6 pagesEssay Modificationapi-709997912Pas encore d'évaluation

- ResearchDocument13 pagesResearchapi-535238750Pas encore d'évaluation

- Understanding the Black Lives Matter MovementD'EverandUnderstanding the Black Lives Matter MovementÉvaluation : 3 sur 5 étoiles3/5 (2)

- Peaceful Protest ProblemsDocument3 pagesPeaceful Protest Problemsapi-302491268Pas encore d'évaluation

- Tcrtcriticalessay 2Document6 pagesTcrtcriticalessay 2api-300973520Pas encore d'évaluation

- Diversity Interest Group Resources - 05-28-23Document8 pagesDiversity Interest Group Resources - 05-28-23Jose M RodriguezPas encore d'évaluation

- Black Nationalism by Fagbamila Fagunwa 2006Document8 pagesBlack Nationalism by Fagbamila Fagunwa 2006Kwa Kwamu100% (1)

- Afro-American Definayion of WomanhoodDocument5 pagesAfro-American Definayion of WomanhoodKashish RajputPas encore d'évaluation

- Dian Million Felt TheoryDocument7 pagesDian Million Felt TheoryAyelen Rosario TisseraPas encore d'évaluation

- RUN IN MY SHOES: THE JOURNEY OF UNDERSTANDING RACE AND PREJUDICE IN AMERICA AS SEEN BY AN AFRICAN-AMERICAND'EverandRUN IN MY SHOES: THE JOURNEY OF UNDERSTANDING RACE AND PREJUDICE IN AMERICA AS SEEN BY AN AFRICAN-AMERICANPas encore d'évaluation

- Assignment On Slave ResistanceDocument6 pagesAssignment On Slave ResistanceJanhavi ShahPas encore d'évaluation

- Resisting White Supremacy at EarlhamDocument23 pagesResisting White Supremacy at Earlhamkrina_guezPas encore d'évaluation

- Race and Racism CurriculumDocument9 pagesRace and Racism Curriculumiricamae ciervoPas encore d'évaluation

- Final ResearchDocument121 pagesFinal ResearchDimple RamchandaniPas encore d'évaluation

- Remembering Slavery: African Americans Talk About Their Personal Experiences of Slavery and EmancipationD'EverandRemembering Slavery: African Americans Talk About Their Personal Experiences of Slavery and EmancipationÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (11)

- Teaching Hard History American SlaveryDocument52 pagesTeaching Hard History American SlaveryKERANews100% (1)

- Rethinking Race and NationDocument8 pagesRethinking Race and NationCarolina SourdisPas encore d'évaluation

- Kaufmann, EP and Oded Haklai, 'Dominant Ethnicity: From Minority To Majority,' Nations and Nationalism, Issue 14.4 (2008), Pp. 743-67Document21 pagesKaufmann, EP and Oded Haklai, 'Dominant Ethnicity: From Minority To Majority,' Nations and Nationalism, Issue 14.4 (2008), Pp. 743-67Eric KaufmannPas encore d'évaluation

- Du Bois: The Gift of Black Folk to America: Historical Account of the Role of African Americans in the Making of the USAD'EverandDu Bois: The Gift of Black Folk to America: Historical Account of the Role of African Americans in the Making of the USAPas encore d'évaluation

- Not An Indian Tradition: The Sexual Colonization of Native PeoplesDocument16 pagesNot An Indian Tradition: The Sexual Colonization of Native PeoplesFatema ZahraPas encore d'évaluation

- Sociology Chapter 9 OutlineDocument4 pagesSociology Chapter 9 Outlinebwade2_916499061Pas encore d'évaluation

- Greywater Treatment RecipeDocument4 pagesGreywater Treatment RecipeCarlos Rafael PitirrePas encore d'évaluation

- Eco Base Camp DesignDocument11 pagesEco Base Camp DesignCarlos Rafael PitirrePas encore d'évaluation

- Revolution: & BlackDocument36 pagesRevolution: & BlackCarlos Rafael PitirrePas encore d'évaluation

- ATC Training Weekend 8-9th May, Nottingham: Compost Toilet Block - Assembly InstructionsDocument34 pagesATC Training Weekend 8-9th May, Nottingham: Compost Toilet Block - Assembly InstructionsCarlos Rafael PitirrePas encore d'évaluation

- Permaculture Noosa Hatches Permaculture CaloundraDocument8 pagesPermaculture Noosa Hatches Permaculture CaloundraCarlos Rafael PitirrePas encore d'évaluation

- Urban PermacultureDocument4 pagesUrban PermacultureCarlos Rafael PitirrePas encore d'évaluation

- Shame Handout Oct 12Document2 pagesShame Handout Oct 12Carlos Rafael PitirrePas encore d'évaluation

- Compost TroubleshootingDocument1 pageCompost TroubleshootingCarlos Rafael PitirrePas encore d'évaluation

- Perennial For Age Hand OutDocument2 pagesPerennial For Age Hand OutCarlos Rafael PitirrePas encore d'évaluation

- Stamets Statement Oil SpillDocument4 pagesStamets Statement Oil SpillCarlos Rafael PitirrePas encore d'évaluation

- Principles of Social PermacultureDocument2 pagesPrinciples of Social PermacultureCarlos Rafael PitirrePas encore d'évaluation

- AI Interview Hand Out PowerDocument1 pageAI Interview Hand Out PowerCarlos Rafael PitirrePas encore d'évaluation

- Peoplecare PrinciplesDocument7 pagesPeoplecare PrinciplesCarlos Rafael PitirrePas encore d'évaluation

- Patterns in Nature MDocument3 pagesPatterns in Nature MCarlos Rafael PitirrePas encore d'évaluation

- Eight Principles of Rainwater HarvestingDocument5 pagesEight Principles of Rainwater HarvestingCarlos Rafael PitirrePas encore d'évaluation

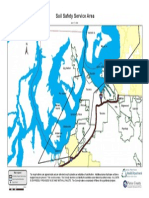

- Asarco Plume MapDocument1 pageAsarco Plume MapCarlos Rafael PitirrePas encore d'évaluation

- What's in The Soil-And What To Do About ItDocument1 pageWhat's in The Soil-And What To Do About ItCarlos Rafael PitirrePas encore d'évaluation

- What Is BioremediationDocument2 pagesWhat Is BioremediationCarlos Rafael PitirrePas encore d'évaluation

- 1987 Bar Questions Obligations and Contract Estoppel 1987 No. 7Document5 pages1987 Bar Questions Obligations and Contract Estoppel 1987 No. 7AiPas encore d'évaluation

- Business Ethics: Felix M. Del Rosario, Cpa, MbaDocument38 pagesBusiness Ethics: Felix M. Del Rosario, Cpa, Mbafelix madayag del rosarioPas encore d'évaluation

- G.R. Nos. L-27425 & L-30505 - Converse Rubber Vs Jacinto RubberDocument8 pagesG.R. Nos. L-27425 & L-30505 - Converse Rubber Vs Jacinto RubberArmand Patiño AlforquePas encore d'évaluation

- Persuasive Essay Draft 1Document11 pagesPersuasive Essay Draft 1mstreeter1124Pas encore d'évaluation

- Essay 3Document6 pagesEssay 3api-378507556Pas encore d'évaluation

- 1 Estate of Hemady v. Luzon SuretyDocument2 pages1 Estate of Hemady v. Luzon SuretyTherese EspinosaPas encore d'évaluation

- Final ISO IEC FDIS 17065 2012 E Conformity AssDocument77 pagesFinal ISO IEC FDIS 17065 2012 E Conformity AssahmadPas encore d'évaluation

- Kohlberg 29Document32 pagesKohlberg 29wendy nguPas encore d'évaluation

- Sayson TheStruggleAgainstMining-PAD2004Document106 pagesSayson TheStruggleAgainstMining-PAD2004junsaturayPas encore d'évaluation

- Vinuya Vs Executive SecretaryDocument4 pagesVinuya Vs Executive SecretaryMark Lester Lee AurePas encore d'évaluation

- Mary ToostealDocument4 pagesMary ToostealtesttestPas encore d'évaluation

- Admin Case DigestsDocument50 pagesAdmin Case DigestsJennyMariedeLeon100% (1)

- Article 3 - Classes of Constitutional Rights: Political Social Economic Civil Rights of The AccusedDocument3 pagesArticle 3 - Classes of Constitutional Rights: Political Social Economic Civil Rights of The AccusedJp Dela CruzPas encore d'évaluation

- A Psychological Study of Nathaniel Hawthorne'S The: Scarlet LatterDocument10 pagesA Psychological Study of Nathaniel Hawthorne'S The: Scarlet LatterRomilyn PiocPas encore d'évaluation

- UN Career Framework EN FINALDocument19 pagesUN Career Framework EN FINALGleh Huston AppletonPas encore d'évaluation

- Algeria External Application Teacher PositionDocument8 pagesAlgeria External Application Teacher PositionImàNePas encore d'évaluation

- Infancy and Toddlerhood FinalDocument4 pagesInfancy and Toddlerhood Finalapi-447499660Pas encore d'évaluation

- Maintenance and Welfare of Parents and Senior Citizens ActDocument12 pagesMaintenance and Welfare of Parents and Senior Citizens ActKrishna PrasadPas encore d'évaluation

- BAPMI Rules On ArbitratorsDocument5 pagesBAPMI Rules On Arbitratorsedwina_kharismaPas encore d'évaluation

- Rakowski Complaint1 Amy MorrisDocument4 pagesRakowski Complaint1 Amy Morrisapi-286623412Pas encore d'évaluation

- Deed of Assignment SM DavaoDocument2 pagesDeed of Assignment SM DavaoFrancisquetePas encore d'évaluation

- James Daniel Lynch - Kemper County Vindicated, and A Peep at Radical Rule in Mississippi (1879)Document438 pagesJames Daniel Lynch - Kemper County Vindicated, and A Peep at Radical Rule in Mississippi (1879)chyoungPas encore d'évaluation

- Virtue As ExcellenceDocument2 pagesVirtue As ExcellenceMelissa AlexandraPas encore d'évaluation

- Shahnama 09 FirduoftDocument426 pagesShahnama 09 FirduoftScott KennedyPas encore d'évaluation

- 04 Integrated Contractor v. NLRCDocument2 pages04 Integrated Contractor v. NLRCJill BagaoisanPas encore d'évaluation

- Mental Health Nursing Assignment Sample: WWW - Newessays.co - UkDocument15 pagesMental Health Nursing Assignment Sample: WWW - Newessays.co - UkAriadne MangondatoPas encore d'évaluation

- Dussel Philosophy of Liberation Preface and Chap 1Document40 pagesDussel Philosophy of Liberation Preface and Chap 1eweislogel100% (1)