Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

The Development and Validation of A Survey Instrument

Transféré par

Schahyda ArleyTitre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

The Development and Validation of A Survey Instrument

Transféré par

Schahyda ArleyDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

The Development and Validation of a Survey Instrument for the Evaluation of Instructional Aids Elaine Strachota Steven W.

Schmidt Simone C. O. Conceio Abstract The processes associated with survey development and testing are critical when doing survey research. Survey development for educational program evaluation is no different. This study offers the researcher both a model for survey development as well as a valid and reliable survey instrument to measure the effectiveness, appeal, and efficiency of instructional aids in an online course environment. Introduction Instructional aids in online environments have been used as a content tool to enhance learning in adult education. However, most articles addressing the use of instructional aids are based on personal experiences, expert opinion, and conventional wisdom. Few studies are grounded in the use of valid and reliable instruments to evaluate instructional aids. This study attempts to address this concern by developing an instrument to measure constructs associated with the use of instructional aids in a higher education context. This instrument was developed and pilot-tested in a health occupations science online course. In a kinesiology online course, students used instructional aids such as videos on movements of the body and muscle testing, digital flash cards and games to identify key concepts related to muscles of the body, and a tutorial program to review content on osteology. These instructional aids were placed within the Blackboard Learning Management System for review and practice of content in preparation for exams. Instructional aids are defined as small units of digital educational materials that can be used flexibly and in a variety of formats (e.g., videos, interactive games, and tutorials) to enhance online lessons. Also known as learning objects, instructional aids decompose content into granular pieces of information that can be stored, retrieved, and reused in instruction (Jonassen & Churchill, 2004, p. 32). These learning objects, or instructional aids, can be used individually, or they can be linked together in units to form a course (Hamel & Ryan-Jones, 2001). Instructional aids are being used increasingly more often in adult education and online education as teaching tools to help students understand concepts. They are easy to use, and can be reused in different contexts (making them cost efficient) (Conceio, Olgren, & Ploetz, 2006). Because of this flexibility, it has been suggested that they are the future of online instruction. Hamel and Ryan-Jones (2001) posit that instructional designers will not be designing courses anymore. [Rather] they will be designing small stand-alone units of instruction called learning objects (p. 1058). The successful use of instructional aids for learning incorporates the following constructs: effectiveness, efficiency, and appeal (Reigeluth, 1999). Effectiveness is how well the instructional aids work relative to student learning. Efficiency is defined by the

level of effectiveness of the instruction divided by the time of the instruction. The level of appeal is the extent to which the learners enjoy using the instructional aids. Pollack (1998) notes that evaluation is frequently difficult in face-to-face learning environments and is compounded in distance education (p. 6). Using a valid and reliable instrument that measures all three constructs will help adult educators and instructional designers to more accurately know if the online instructional aids their students are using are, in fact, enhancing learning. Survey Model How can the constructs of effectiveness, efficiency, and appeal related to the use of instructional aids best be measured? In order to answer this question, a survey instrument was developed to evaluate the effectiveness, efficiency, and appeal of instructional aids in a kinesiology online course. The structure of the course for this study included 15 modules of online instruction, optional one-hour open labs held each week when there was a scheduled oncampus proctored exam, discussion groups, and online quizzes. The open lab was designed primarily as a review of content and for hands-on demonstration. Students were given surveys asking their opinion of the effectiveness, efficiency, and appeal of the instructional aids before taking the on-campus exams. Twenty students enrolled in the online course completed a survey instrument to evaluate the instructional aids embedded within each lesson during the course of the semester. Students were given multiple surveys after each unit of instruction. The survey depended on the instructional aids used during the unit. For example, for unit 1 the instructional aid was video, so a survey with questions specific to the video aid was conducted. Units 2 and 3 used a tutorial, so a survey focusing on the tutorial was conducted. Units that contained video and interactive games used a survey specific to this type of instructional aid. The survey was the same with the exception of the name of the instructional aid.

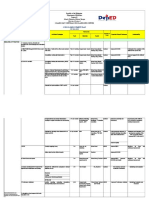

Yes Factor Analysis (Reliabiltiy and Validity Check)

Review of Literature

Research Question

Construct Development

Survey Question Development

Content Validity Check

Pilot Study (Test)

Add/Delete/ Change Questions?

No

Survey adaptable for online use?

Yes

Adapt survey

Distribute Survey

Data Collection

Data Analysis

No

ONLINE ENVIRONMENTAL CONCERNS: Survey Audience Technical Skills Internet Access

Consider other methods of survey distribution

GENERAL ENVIRONMENTAL CONCERNS: Cost Efficiency Time Efficiency Methodological Efficiency

Figure 1. Model for Online Survey Development

Survey Instrument In order to develop a survey instrument to evaluate instructional aids, a model for online survey development was used (see Figure 1) (Schmidt, Strachota, & Conceio, 2006). A review of literature on instructional aids was conducted, and it was determined that there was a gap in the literature related to the evaluation of instructional aids in higher education settings. Constructs related to the evaluation of instructional aids were identified based on Reigeluths (1999) instructional design theory, and survey questions were developed. To ensure content validity, experts in survey research and in the subject matter were consulted and their input was used in question revision and redesign. A pilot test (N=20) was also conducted in order to establish content validity. Factorial analysis of data from the pilot test then determined the construct validity. Following factor analysis, the instrument was tested for reliability. Instructional Aids Survey Instrument Instructional aids were evaluated using the following instrument. The purpose of this investigation is to study the effectiveness, efficiency, and appeal of instructional aids within this college course. Data collected from this survey will be kept confidential. Data will be grouped and your comments will not be individually identifiable. Filling out this survey indicates that you are at least 18 years old and are giving your informed consent to be a participant in this study. DEMOGRAPHICS Age: __18-24 __25-34 __35-44 __45-54 __55-64 Gender: _____Male _____Female Ethnicity: __Caucasian/White, __African American, __Hispanic, __Asian, __Native American Strongly Agree Agree Neutral Disagree Strongly Disagree

EFFECTIVENESS OF INSTRUCTIONAL AIDS 1. This instructional aid helped me when practicing (insert as appropriate: movements of the body, muscle testing positions, etc). 2. This instructional aid helped me to better understand the information (insert as appropriate: movements of the body, muscle testing positions, etc). 3. This instructional aid put meaning to the written material (content) for this lesson. 4. This instructional aid helped me to better understand the textbook information. APPEAL OF INSTRUCTIONAL AIDS 5. This instructional aid was organized by a specific (insert as appropriate: joint, bone, muscle) so that it was easy to search and review information. 6. This instructional aid offered feedback so that I knew if my response was correct or incorrect and if I needed to continue to review. 7. I was satisfied with the design of this instructional aid.

8. I was satisfied with the look of this instructional aid (visual clarity). EFFICIENCY OF INSTRUCTIONAL AIDS 9. Approximately how many hours did you spend reviewing the information in this instructional aid? _____Hours 10. Select the purpose for using this instructional aid (select all that apply): ___ Reinforce, ___ Clarification, ___ Practice, ___ Review, ___ Retention 11. I experienced technical difficulty when using this instructional aid? _____ Yes _____ No If yes, describe what technical problems you encountered. GENERAL SATISFACTION WITH INSTRUCTIONAL AIDS 12. Did you like using the instructional aids in this course? _____ Yes _____ No Strongly Agree Agree Neutral Disagree Strongly Disagree 13. Overall I was satisfied with this instructional aid. 14. Overall I feel I was able to learn the information from this instructional aid as well as I would have in a face-to-face class presentation. Reliability and Validity This study was conducted during the spring 2006 semester. Validity and reliability were established for the instrument. Through the process of factor analysis using varimax rotation the instrument identified two strong constructs: effectiveness and appeal. Items within the construct of effectiveness factor loaded from .800 to .916. Items within the construct of appeal factor loaded from .618 to .905. Reliability was found to have a Cronbachs alpha of .90. Efficiency was found not to be a strong construct because of its interdependency on effectiveness. It was determined that efficiency could be more accurately measured through the use of qualitative questions. Therefore, qualitative questions were designed for the efficiency category. The pilot test was found to be an important stage of the instrument development process as necessary revisions were identified. These revisions were made and the final survey instrument was used to evaluate the instructional aids. Summary of Results Survey results showed that students were highly satisfied with the instructional aids used in this online course. There was no significant difference in the level of effectiveness and appeal when comparing the use of instructional aids such as video, interactive games, and tutorial instruction. Overall video received the highest ratings compared to interactive games and tutorials. Video was used for the movements of the body and for all muscle testing units in the course. Through qualitative analysis of efficiency, students identified that video was used most often for clarification of concepts (81.3%). Comments included statements such as, viewing the video clips helps me understand the content better by viewing it instead of just reading the material or when I had a question I was able to go back to the videos to find out the answer and it made it more clear. Therefore, the use of video enhanced learning by offering visual feedback for clarification of written content.

Interactive games were designed using a QUIA software program, which allowed the designer to develop a variety of activities such as flashcards with embedded graphics and audio, matching games, concentration, challenge boards, ordered lists, higher-ordered questioning, and self-assessment quizzes. Through qualitative analysis of efficiency, students identified that interactive games were used most often to reinforce concepts (76.5%) and for practice (58.8%) and review (58.8%). Interactive games were used least often for clarification (29.4%). Comments included statements such as, the QUIA flashcards reinforced learning for example, being able to save or discard cards to find out which ones I needed to practice more or the flashcards help a lot. As soon as I saw the pictures on the cards I remembered them from the reading materials. It made studying more efficient. The interactive activities were developed to reinforce written content and for practice and review as often as needed prior to the exam. A tutorial was developed for the osteology unit using Authorware software. The tutorial was created with a graphic of each bone and the specific landmarks of that bone. Landmark names were created as labels on the left of the screen. The student was to mentally attempt to identify where the landmark was located and then click on a designated label. Once the label was selected it then moved to the correct location on the bone. Through qualitative analysis of efficiency, students identified that the tutorial was used most often to reinforce concepts (75%) and for practice (62.5%). Comments included statements such as, the program helped me see the landmarks of the bones. It helps because the bone is there and I can say what it is, then click on it and I can see if I got it right or the tutorial was a great tool in reviewing and reinforcing all the landmarks of the bones. The tutorial was developed to reinforce written content and to offer feedback to the student as to what content had or had not been learned. Overall the majority of students felt that they could learn online as effectively as they could in a classroom environment. Analysis of instructional media showed that 87.5% of the students (strongly agree and agree) felt they could learn online as effectively when video was used (6.3% neutral, 6.3% disagree). This compared to 70.5% of the students (strongly agree and agree) who felt they could learn as effectively online when interactive games were used (17.6% neutral, 11.8% disagree), whereas 65% of the students (strongly agree and agree) felt they could learn online as effectively when tutorial instruction (18.8% neutral, 18.8% disagree) was used. As one student stated, with video, I was able to replay it, and replay it. In a classroom setting you basically see it once. Another valuable comment made was, I would like to say that all of the instructional aids that are provided with this course have been extremely helpful and beneficial to grasping the course content. I dont think this course could be an online course (effectively) without the way it is set up organizationally and also without the tools that have been provided. Limitations of this study include a small sample size and the fact that this course was a required program course only offered through an online format. Although students did not choose online learning the majority found it to be a positive experience. One student summed the course experience as, I actually think I learn better online as I can take my time and go over things as many times as I need to. Conclusions and Implications for Practice Klecker (2005) states that online assessments can measure the students achievement of intended learning objects if, and only if, great diligence is used in their construction (p. 2). The formal process used in the development of this survey instrument is an example of exactly that

diligence. Pilot testing a survey instrument is a critical step of survey research. In this study the survey instrument was revised based on the pilot study. A model for online survey development as well as a valid and reliable survey instrument to measure the effectiveness, appeal, and efficiency of instructional aids was developed and shared. This study further identifies the need to move beyond text and to create interactivity using instructional aids such as video, interactive games, and tutorials in an online environment. This study serves to link the theory of instructional design to the practice of adult education and online learning. Further studies of this nature should be conducted to support the findings of this research study. References Conceio, S., Olgren, C., & Ploetz, P. (2006). Reusing learning objects in three settings: Implications for online instruction. International Journal of Instructional Technology and Distance Learning, 3(4). Hamel, C. J., & Ryan-Jones, D. L. (2001). Were not designing courses anymore. In W. A. Lawrence-Fowler and Joachim Hasebrook (Eds.), Proceedings of WebNet 2001 World Conference on the WWW and Internet (pp. 1057-1062), Orlando, FL. Jonassen, D., & Churchill, D. (2004). Is there a learning orientation in learning objects? International Journal on E-Learning, 3(2), 32-41. Klecker, B. M. (2005). Assessing learning online: The top ten list. Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the Society for Information Technology and Teacher Education (SITE), Phoenix, AZ. Pollack, T. A. (1998). Preparing a course for distance education delivery. Association of Small Computer Users in Education: Proceedings of the 31st ASCUE Summer Conference (pp. 122-127), North Myrtle Beach, SC. Reigeluth, C. (1999). What is instructional design theory and how is it changing? In C. Reigeluth (Ed.), Instructional design theories and models, volume II: A new paradigm of instructional theory (5-30). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. Schmidt, S., Strachota, E., & Conceio, S. (2006). The use of online surveys to measure satisfaction in job training and workforce development. Columbus, OH: Academy of Human Resource Development Conference. Elaine Strachota, PhD, Associate Professor, Concordia University Wisconsin, Professor, Milwaukee Area Technical College, strachoe@matc.edu, Steven W. Schmidt, PhD, Assistant Professor, East Carolina University, schmidts@ecu.edu, Simone C. O. Conceio, PhD, Assistant Professor, University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, simonec@uwm.edu. Presented at the Midwest Research-to-Practice Conference in Adult, Continuing, and Community Education, University of Missouri-St. Louis, St. Louis, MO, October 4-6, 2006.

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- Online vs Classroom Education: Integrating Effective Online Teaching StrategiesDocument32 pagesOnline vs Classroom Education: Integrating Effective Online Teaching StrategiesDiana Deng100% (2)

- School Improvement Plan: Republic of The Philippines Department of Education Region 02 Schools Division of Nueva VizcayaDocument20 pagesSchool Improvement Plan: Republic of The Philippines Department of Education Region 02 Schools Division of Nueva VizcayaClarissa Flores Madlao MendozaPas encore d'évaluation

- Effectiveness of 5E Instructional MaterialsDocument5 pagesEffectiveness of 5E Instructional MaterialsJohn Jufel Valdez100% (1)

- Coaching Critical Thinking To Think Creatively!Document14 pagesCoaching Critical Thinking To Think Creatively!Zaid Ali Alsagoff92% (13)

- ClassVR Whitepaper A Guide To AR VR in EducationDocument32 pagesClassVR Whitepaper A Guide To AR VR in EducationDražen Horvat100% (1)

- Cot-Rpms Observation Notes FormDocument3 pagesCot-Rpms Observation Notes FormJane Del Rosario100% (1)

- The Schoolwide Enrichment Model in Science: A Hands-On Approach for Engaging Young ScientistsD'EverandThe Schoolwide Enrichment Model in Science: A Hands-On Approach for Engaging Young ScientistsÉvaluation : 5 sur 5 étoiles5/5 (1)

- Effects of Cell Phone To Academic PerforDocument36 pagesEffects of Cell Phone To Academic PerforRobert Podiotan MantosPas encore d'évaluation

- Introduction to Multivariate ANOVA (MANOVADocument14 pagesIntroduction to Multivariate ANOVA (MANOVASchahyda ArleyPas encore d'évaluation

- Accomplishment Report Inset 21-22Document13 pagesAccomplishment Report Inset 21-22JOE RALPH MABBORANG100% (2)

- Statement of PurposeDocument2 pagesStatement of PurposeSaurav Pariyar0% (1)

- Practical Research 1 11 Q2 M5Document15 pagesPractical Research 1 11 Q2 M5Akisha Fijo100% (1)

- The Virtual Avatar Lab (VAL) : Tapping Into Virtual Live Environments To Practice Classroom Feedback ConversationsDocument12 pagesThe Virtual Avatar Lab (VAL) : Tapping Into Virtual Live Environments To Practice Classroom Feedback Conversationsemmanuel torresPas encore d'évaluation

- Working Paper SeriesDocument21 pagesWorking Paper SeriesDarren KuropatwaPas encore d'évaluation

- Research Proposal PlanDocument5 pagesResearch Proposal PlanFaqih SopyanPas encore d'évaluation

- Multimedia Research Summary and Analysis: Design and Development of Multimedia Instruction Gerald T. Dolphus Houston Christian UniversityDocument6 pagesMultimedia Research Summary and Analysis: Design and Development of Multimedia Instruction Gerald T. Dolphus Houston Christian Universityapi-560824582Pas encore d'évaluation

- Benefits of Online Learning with Video for Nursing StudentsDocument20 pagesBenefits of Online Learning with Video for Nursing StudentsNamoAmitofouPas encore d'évaluation

- 8611 Assignment 2Document19 pages8611 Assignment 2Khan BabaPas encore d'évaluation

- Designing For Impact A Conceptual Framework For Learning Analytics As Self Assessment ToolsDocument12 pagesDesigning For Impact A Conceptual Framework For Learning Analytics As Self Assessment ToolsMathijs StevensPas encore d'évaluation

- Bsic Terms in EductaionDocument10 pagesBsic Terms in EductaionMarcos MendozaPas encore d'évaluation

- Qualities of Classroom Observation SystemsDocument28 pagesQualities of Classroom Observation SystemsAshrafPas encore d'évaluation

- Stake S Countenance ModelDocument16 pagesStake S Countenance Model유웃Pas encore d'évaluation

- M.E.T. RationaleDocument35 pagesM.E.T. RationaledmdainessmithPas encore d'évaluation

- Telaah JurnalDocument7 pagesTelaah JurnalAremia VaneshaPas encore d'évaluation

- Enhancing Academic Performance with Video-Assisted LearningDocument11 pagesEnhancing Academic Performance with Video-Assisted LearningJohnpaul DaugPas encore d'évaluation

- Fostering Sustained Idea ImprovementDocument12 pagesFostering Sustained Idea Improvement黃裕成Pas encore d'évaluation

- Mod8 Discussion PostDocument6 pagesMod8 Discussion Postapi-535003994Pas encore d'évaluation

- Group e Simulation Powerpoint-2Document6 pagesGroup e Simulation Powerpoint-2api-302205250Pas encore d'évaluation

- Journal Analysis C3Document21 pagesJournal Analysis C3Reginald AgcambotPas encore d'évaluation

- Stake's Countenance ModelDocument15 pagesStake's Countenance ModelNanaMulyanaPas encore d'évaluation

- Swandermelinda A Review of The Literature ngr6715Document7 pagesSwandermelinda A Review of The Literature ngr6715api-259047759Pas encore d'évaluation

- Storyboard - Development - For - Interactive - M20160127 21969 7v3dqc With Cover Page v2Document15 pagesStoryboard - Development - For - Interactive - M20160127 21969 7v3dqc With Cover Page v2s160818035Pas encore d'évaluation

- Why Gizmos WorkDocument27 pagesWhy Gizmos Workmitooquerer72600% (2)

- Improving Biology Learning with Game-Based Formative AssessmentsDocument3 pagesImproving Biology Learning with Game-Based Formative Assessmentsjane austin lynn rebancosPas encore d'évaluation

- Review of Literature on Quipper School E-Learning PlatformDocument19 pagesReview of Literature on Quipper School E-Learning PlatformRoland Roi De GuzmanPas encore d'évaluation

- VIIIIDocument10 pagesVIIIIMadhu BalaPas encore d'évaluation

- 7500 Miller 2Document2 pages7500 Miller 2api-319316297Pas encore d'évaluation

- Multimedia Learning andDocument13 pagesMultimedia Learning andArya zebuaPas encore d'évaluation

- Field Experiences To Synthesize and Apply The Content and Professional Knowledge, Skills, andDocument2 pagesField Experiences To Synthesize and Apply The Content and Professional Knowledge, Skills, andapi-533548625Pas encore d'évaluation

- Chapter 4Document6 pagesChapter 4MARIFA ROSEROPas encore d'évaluation

- Problem Statement Definition: Understanding The ProblemDocument6 pagesProblem Statement Definition: Understanding The Problemmanoj chowdaryPas encore d'évaluation

- Ab Lowery KarmenDocument5 pagesAb Lowery Karmenapi-632517517Pas encore d'évaluation

- AR Boudah PDFDocument20 pagesAR Boudah PDFAin SurayaPas encore d'évaluation

- Mini Lesson2Document7 pagesMini Lesson2api-316726013Pas encore d'évaluation

- Educ 581 - Field Experience ReportDocument26 pagesEduc 581 - Field Experience Reportapi-548868233Pas encore d'évaluation

- Fostering Effective Learning Strategies in Higher EducationDocument18 pagesFostering Effective Learning Strategies in Higher Educationjefford torresPas encore d'évaluation

- Document 2 NewDocument30 pagesDocument 2 Newaruma jayantiPas encore d'évaluation

- Learning and Online AssessmentsDocument12 pagesLearning and Online AssessmentsMarkaela BryanPas encore d'évaluation

- Validity and Reliability of Research InstrumentDocument4 pagesValidity and Reliability of Research InstrumentZaira M.Pas encore d'évaluation

- Instructional Design Framework For Educational Media: SciencedirectDocument16 pagesInstructional Design Framework For Educational Media: SciencedirectHeng LyhourPas encore d'évaluation

- Module 2 Developing Action Researches Steps and ActionsDocument8 pagesModule 2 Developing Action Researches Steps and ActionsDora ShanePas encore d'évaluation

- Assignment 7 - Research On Visual and Media LiteracyDocument9 pagesAssignment 7 - Research On Visual and Media Literacyapi-704120575Pas encore d'évaluation

- Half-Day Tutorial: Evaluating Interactive Products For and With ChildrenDocument3 pagesHalf-Day Tutorial: Evaluating Interactive Products For and With ChildrenDevia DevahartPas encore d'évaluation

- Quali Template Ge 2Document4 pagesQuali Template Ge 2ABM1 TAMONDONGPas encore d'évaluation

- Published Version in Cjni of Collaborative Design of Online Simulation Platform For Unfoldign Case StudiesDocument10 pagesPublished Version in Cjni of Collaborative Design of Online Simulation Platform For Unfoldign Case Studiesapi-293628090Pas encore d'évaluation

- Awareness On The Advantages and Disadvantages ofDocument10 pagesAwareness On The Advantages and Disadvantages ofMatthew Spencer HoPas encore d'évaluation

- Ar DonavieDocument9 pagesAr Donaviejd gomezPas encore d'évaluation

- Motivation and Learning Modes: Towards An Automatic Intelligent Evaluation of Learner MotivationDocument10 pagesMotivation and Learning Modes: Towards An Automatic Intelligent Evaluation of Learner MotivationSoleh RitongaPas encore d'évaluation

- Traditional and Alternative AssessmentDocument34 pagesTraditional and Alternative AssessmentCaro MoragaPas encore d'évaluation

- Gtu Me Dissertation Review CardDocument4 pagesGtu Me Dissertation Review CardWhereCanIBuyResumePaperAkron100% (1)

- Document 3Document10 pagesDocument 3Allysa MendozaPas encore d'évaluation

- Developing An Intelligent Diagnosis Assessment E-Learning ToolDocument19 pagesDeveloping An Intelligent Diagnosis Assessment E-Learning ToolEmil StankovPas encore d'évaluation

- SHS Module PRACTICAL RESEARCH 2 Week 1Document22 pagesSHS Module PRACTICAL RESEARCH 2 Week 1Roilene MelloriaPas encore d'évaluation

- Professional Inquiry Project-Emma de CureDocument11 pagesProfessional Inquiry Project-Emma de Cureapi-361111336Pas encore d'évaluation

- Foster Ted 4000 Stratpres SummaryDocument3 pagesFoster Ted 4000 Stratpres Summaryapi-532262279Pas encore d'évaluation

- Journal Paper BharathDocument9 pagesJournal Paper BharathVajram Ramesh - IPPas encore d'évaluation

- How To Increase Learning TransferDocument2 pagesHow To Increase Learning TransferCyrilraincreamPas encore d'évaluation

- Additional Science CourseworkDocument10 pagesAdditional Science Courseworkafazbsaxi100% (2)

- Researcher Design and MethodologyDocument8 pagesResearcher Design and MethodologyMyraPas encore d'évaluation

- Link OppmDocument1 pageLink OppmSchahyda ArleyPas encore d'évaluation

- HargreavesDocument77 pagesHargreavesSchahyda ArleyPas encore d'évaluation

- Baseball: Design: DESIGN-38 Option: Round Neck Sleeves: SET-INDocument1 pageBaseball: Design: DESIGN-38 Option: Round Neck Sleeves: SET-INSchahyda ArleyPas encore d'évaluation

- Individual Ability TestDocument7 pagesIndividual Ability TestSchahyda ArleyPas encore d'évaluation

- EQ PresentationDocument64 pagesEQ Presentationa5nuPas encore d'évaluation

- Install NotesDocument1 pageInstall NotesSchahyda ArleyPas encore d'évaluation

- Contoh JournalDocument23 pagesContoh JournalSchahyda ArleyPas encore d'évaluation

- Statement of ProblemDocument1 pageStatement of ProblemSchahyda ArleyPas encore d'évaluation

- Good PowerpointDocument63 pagesGood PowerpointSchahyda Arley100% (1)

- Tips For Developing An Effective QuestionnaireDocument7 pagesTips For Developing An Effective QuestionnaireSchahyda ArleyPas encore d'évaluation

- FoodchainDocument13 pagesFoodchainSchahyda ArleyPas encore d'évaluation

- 2 Collapsing N Rating Scales ValidityDocument4 pages2 Collapsing N Rating Scales ValiditySchahyda ArleyPas encore d'évaluation

- Instrument Development 2Document20 pagesInstrument Development 2Schahyda ArleyPas encore d'évaluation

- 0.1 Fundamental Principles of MeasurementDocument35 pages0.1 Fundamental Principles of MeasurementSchahyda ArleyPas encore d'évaluation

- The Extent To Which Neurological Status, Gross Motor, and Executive Processing Support Growth in Daily Living Skills Across Elementary School Ages For Children Who Vary in Biological RiskDocument76 pagesThe Extent To Which Neurological Status, Gross Motor, and Executive Processing Support Growth in Daily Living Skills Across Elementary School Ages For Children Who Vary in Biological RiskSchahyda ArleyPas encore d'évaluation

- 0.2 Rasch Model Theorem Scale ConstructDocument23 pages0.2 Rasch Model Theorem Scale ConstructSchahyda ArleyPas encore d'évaluation

- Alaba Adeyemi AdediwuraDocument12 pagesAlaba Adeyemi AdediwuraSchahyda ArleyPas encore d'évaluation

- Assignment Presentation ReportDocument48 pagesAssignment Presentation ReportSchahyda ArleyPas encore d'évaluation

- Webpage FlowDocument5 pagesWebpage FlowSchahyda ArleyPas encore d'évaluation

- MID Term KTNDocument6 pagesMID Term KTNSchahyda ArleyPas encore d'évaluation

- Test Bias Against MinoritiesDocument32 pagesTest Bias Against MinoritiesSchahyda ArleyPas encore d'évaluation

- Boards of Christian Mission SchoolsDocument12 pagesBoards of Christian Mission SchoolsSchahyda ArleyPas encore d'évaluation

- An Assessment of The Motor Ability of LeanersDocument114 pagesAn Assessment of The Motor Ability of LeanersSchahyda ArleyPas encore d'évaluation

- Questionnaire SampleDocument4 pagesQuestionnaire SampleSchahyda ArleyPas encore d'évaluation

- Test Anxiety in School Settings Implication On TeachersDocument5 pagesTest Anxiety in School Settings Implication On TeachersSchahyda ArleyPas encore d'évaluation

- Nota SainsDocument4 pagesNota SainsSchahyda ArleyPas encore d'évaluation

- Bab 11 Test Paired SamplesDocument27 pagesBab 11 Test Paired SamplesSchahyda ArleyPas encore d'évaluation

- Test Anxiety in School Settings: Implication On Teachers: Nor Shahida Mohammad Ali, Rohaya TalibDocument1 pageTest Anxiety in School Settings: Implication On Teachers: Nor Shahida Mohammad Ali, Rohaya TalibSchahyda ArleyPas encore d'évaluation

- Student Teaching Experience at Trece Martires City National HighschoolDocument78 pagesStudent Teaching Experience at Trece Martires City National HighschoolCheriel Alcala CalledoPas encore d'évaluation

- Python Introduction LessonDocument9 pagesPython Introduction LessonRockyphPas encore d'évaluation

- SISPres 9Document73 pagesSISPres 9sayedmhPas encore d'évaluation

- Impact of Digital Technology On Education: August 2005Document9 pagesImpact of Digital Technology On Education: August 2005Uday MugalPas encore d'évaluation

- Generalao Company Draft 3Document24 pagesGeneralao Company Draft 3jaylordsolis381Pas encore d'évaluation

- Desi Tri Lestari - The Implementation of Learning Management System For Online Learning in English As Foreign Language (Efl) at Sman 1 JatilawangDocument134 pagesDesi Tri Lestari - The Implementation of Learning Management System For Online Learning in English As Foreign Language (Efl) at Sman 1 JatilawangFauzan MiraclePas encore d'évaluation

- Yearbook 2021Document123 pagesYearbook 2021rlinaoPas encore d'évaluation

- Project ReportDocument52 pagesProject ReportMaria FatimaPas encore d'évaluation

- Etech W10 Q4 Cot 12072022Document24 pagesEtech W10 Q4 Cot 12072022Ryan TusalimPas encore d'évaluation

- Video-Based E-Module For Mathematics in Nature and Students' Learning Experiences in A Flipped ClassroomDocument21 pagesVideo-Based E-Module For Mathematics in Nature and Students' Learning Experiences in A Flipped ClassroomMalagante AiraPas encore d'évaluation

- Lesson Plan Week 8Document4 pagesLesson Plan Week 8api-545805920Pas encore d'évaluation

- Is Online Schooling As Effective As in Face-to-FaceDocument2 pagesIs Online Schooling As Effective As in Face-to-FaceKarylle Keith BilongPas encore d'évaluation

- Thesisfinal Draft ProjectDocument99 pagesThesisfinal Draft Projecttahani emhmedPas encore d'évaluation

- SM 313 Strategic ManagementDocument11 pagesSM 313 Strategic Managementריאל אמנם נכוןPas encore d'évaluation

- Educ 301 OBTLDocument9 pagesEduc 301 OBTLRazel DizonPas encore d'évaluation

- Mac4862 2024 TL 101 0 AbDocument16 pagesMac4862 2024 TL 101 0 AbstibalowPas encore d'évaluation

- English Remedial Course OutlineDocument3 pagesEnglish Remedial Course OutlinechinjeannePas encore d'évaluation

- Academic stress in the midst of New Normal LearningDocument7 pagesAcademic stress in the midst of New Normal LearningIanPas encore d'évaluation

- Entrepreneurship & Halal EarningDocument7 pagesEntrepreneurship & Halal EarningAritri AyatPas encore d'évaluation

- SS21 Lesson 5 Physical & Digital SelfDocument14 pagesSS21 Lesson 5 Physical & Digital SelfCARRAO, Samuel Jr.Pas encore d'évaluation

- COVID Induced Inequalities For Publication 20230306Document117 pagesCOVID Induced Inequalities For Publication 20230306Sandugash TagoboyevaPas encore d'évaluation

- BPED 3B - Topic 2 Part 2-BENLACDocument13 pagesBPED 3B - Topic 2 Part 2-BENLACAnton Rafael SiapnoPas encore d'évaluation