Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

4-3 24 LeBon - Decision Making 3

Transféré par

Maxhar AbbaxCopyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

4-3 24 LeBon - Decision Making 3

Transféré par

Maxhar AbbaxDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Practical Philosophy

November 2001

Towards Wise Decision-Making III: Critical and Creative Thinking

Tim LeBon and David Arnaud

Tony's girlfriend, Liz, has just told him that she is moving back home, because her job here is not working out and she is a bit homesick. Liz has intimated that she would like Tony to join her. The trouble is that home for Liz is Australia. Tony comes to you, a decision counsellor, for help with the difficult task of deciding whether to uproot from the UK and join her in Australia, or in effect end a promising relationship. How might you help him?

1) Introduction

Our aim in this series of articles is to arrive at a procedure which will help the practical philosopher enable clients like Tony make wise decisions. In the first article we looked at decision analysis, where options presented by the client are assessed in terms of the probability and utility of likely outcomes. Whilst we admired its structured and logical approach, we concluded that it paid too little attention to the need for creativity in order to think up options, and questioned its narrowness in assessing outcomes in terms of utility. (Practical Philosophy 3.1, March 2000). In our last article (Practical Philosophy 3.3, November 2000) we looked at the role of the emotions in wise decision-making. We argued that at each stage of the decision-making process emotions can either help or hinder, and suggested how the decision counsellor could best work with them. In the present paper we intend to complement these ideas by looking at how thinking can help produce wise decisions. Whilst there has recently been an explosion of work in philosophy on critical thinking, and in management literature on creative thinking, there has been relatively little on how either can be applied specifically to decision-making. Furthermore surprisingly little has been written on how critical and creative thinking can be harnessed together. In this paper we aim to take a step towards improving this situation. We will begin by discussing the varieties of critical and creative thinking and their efficacy in producing wise decisions. We will

go on to explore how critical and creative thinking can best be used in harness, with reference to the logically desirable stages of decision-making. Whilst we will be making a number of comments about the value of the various approaches, our main aim is the constructive one of developing methods of use to the practical philosopher. In order to ensure that our discussion pays sufficient attention to the concrete, we will use the case vignette of Tony above to illustrate the various approaches. In the final section, we will examine to what extent the discussion has succeeded in providing a framework for wise decision-making.

2) Critical Thinking

Robert Ennis has defined critical thinking as 'a process, the goal of which is to make reasonable decisions about what to believe and what to do.'1 (Ennis, 1996). However, there are two different ideas about what this process entails, which can be termed the 'fallacies' and the 'good reasons' approach. We will look at each in turn in order to explore the usefulness and limitations of each in helping people make wise decisions.

2.1 The fallacies approach The fallacies approach to critical thinking categorises the errors in thinking that lead people to mistaken conclusions. This has resulted in the generation of lists of fallacies and is exemplified in Nigel Warburtons Thinking From A to Z.2 (Warburton, 1996). Fallacies listed

1

In practice critical thinking has focused more on what to believe than what to do.

Warburton's book is more than just a list of fallacies; it also contains explanations of other philosophical terms such as 'necessary condition' and 'thought experiment'.

2

24

http://www.practical-philosophy.org.uk

Towards Wise Decision-Making III: Critical and Creative Thinking

Tim LeBon & David Arnaud

by Warburton include:

Fallacy Ad hominem Affirming the consequent Bad company fallacy Rash generalisation Straw man

Meaning Attacking the person rather than the relevant argument An argument of the form If p then q; q; therefore p Attacking something because it has been held by someone evil or stupid A statement based on insufficient evidence Caricaturing opponent's view to make it seem more implausible than it really is

troubling; one tailors the list of fallacies to the cognitive abilities and logical habits of the client, and the amount of time one has. To argue that just because you cannot cover every fallacy to the conclusion that the method is no use may seem itself to be an example of an 'all-ornothing' fallacy itself. Moreover, it may be possible to focus mainly on the major sources of fallacious reasoning which, we suggested in our previous article (Practical Philosophy 3.1, March 2000) may be vividness and emotional language. In Tony's case, for example, it may be the vividness of his friend Pete's story that leads to his reasoning errors - hence a reminder that 'vividness does not equal importance' could be very helpful. But a further limitation of the fallacies approach is much more damaging. This is that the fallacies approach provides no account of what makes for a wise decision; it only specifies what a bad reason is. This would be all right providing every decision which involves no fallacies is wise and every decision which does involve fallacies is unwise. But neither is the case. For example, suppose Tony says he should not go to Australia because he will have difficulty getting work out there. This reasoning does not involve any fallacies; are we to conclude that it is necessarily a wise decision? No, because we need to assess not only whether reasons are fallacious, we also need to decide whether they are strong. Similarly, even if he decides not to go to Australia because of his friend Pete's experience, this does not entail that this is a bad decision; it only means that he is making it for the wrong reason.4 2.3 The good reasoning approach Fortunately, the other approach to critical thinking, the good reasoning approach, promises exactly what is required; the capacity not merely to detect fallacious reasons, but to guide us as to how important nonfallacious reasons are. Here the approach is not upon listing fallacies but upon specifying what good reasoning involves.5 This consists of an analysis of the

this in a group counselling environment with addicts, with considerable success.

Table 1: Some of the fallacies listed in Warburton's Thinking From A to Z.

2.2 The fallacies approach and decision-making Basing wise decision-making on the fallacies approach involves identifying fallacies in the reasoning behind a decision. Let us return to our example of Tony, faced with the decision of whether to emigrate with his girlfriend, Liz, to Australia. A decision counsellor using the fallacies approach would ask Tony to give his reasons for and against going. Suppose he said that he is very wary of going, because his best friend, Pete, had had a similar decision to make with a Canadian, had decided to emigrate, and it had turned out disastrously. The fallacy theorist would point out that Tony was guilty of the fallacy of rash generalisation (not necessarily using this term of course). Just because Pete had had a bad experience emigrating, does not mean all people do, and more to the point does not mean that Tony will. While such an approach is useful to the extent that it really does enable people to recognise and avoid fallacies it also has several limitations. First it is nonexhaustive; there are a potentially unlimited number of ways it is possible to reason wrongly so no list of fallacies will ever catch all these errors. If the counsellor responds by adding more and more fallacies to the list, it will rapidly become unmanageable; it is unreasonable to expect clients to be able to digest too many kinds of fallacies.3 This criticism might not be thought to be too

Unless one devotes a large proportion of session time to teaching fallacies. Raabe (2000) describes how he did precisely

3

4 Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT), although it does not focus specifically on decision-making, is open to similar criticisms since it concentrates on avoiding errors in thinking rather than producing good thinking.

5 For examples of books which take the good reasoning approach to critical thinking see Govier, T. (1985) and Thomson, A. (1999).

http://www.practical-philosophy.org.uk

25

Practical Philosophy

November 2001

formal characteristics of good reasons. For a reason to be a good reason there are three formal characteristics that need to be satisfied. It must be: a) Acceptable 6 - a conclusion is not supported by a reason that is more doubtful than the conclusion. In Tonys case it might be that, unknown to him, Petes experience of going to Canada turned out fine in the end. If this were so then Petes emigration to Canada turned out disastrously is not an acceptable, and therefore not a good, reason for Tony to conclude that his going to Australia will turn out disastrously. b) Relevant. It might be that the reason is acceptable but that it is simply irrelevant to the purported conclusion. Suppose on a gloomy day Tony sees a holiday program featuring his favourite presenter having a splendid time in a sunny foreign country. 'My favourite presenter likes being abroad in the sun' is acceptable - it is the case that the presenter likes being abroad in the sun - but is it really relevant to Tonys decision about whether to live in Australia? C) Strong. Finally, reasons which are both acceptable and relevant need to be evaluated in terms of their strength - not all acceptable and relevant reasons are equally important. For instance living in a sunny country and having a good career are both relevant and acceptable reasons for choosing where to live but are they both equally important? 2.4 The good reasoning approach and decision-making Applied to decision-making, the good reasoning approach means listing the pros and cons for and against an option and choosing the option with the weightiest 7 reasons. Of course, listing the pros and cons is hardly new; a famous example being Charles Darwin's deliberation over whether to get married (LeBon, 2001). What is more novel, and makes the method much more rigorous and attractive, is combining pros and cons with the 'acceptable/relevant/strong' criterion for assessing reasons. In a sense, the good reasoning approach is

logically superior to the fallacies approach. If one succeeds in applying the good reasons approach, we arrive at a decision that is not only not fallacious; it is also positively good. Though clearly helpful, the good reasoning approach can be somewhat limited on three counts. Limitation 1: the good reasoning approach helps us assess the reasons presented for making a particular decision, but it does not help us perceive (think up, imagine) what these reasons might be. The decision counsellor can't just rely on the client producing all the reasons but needs to help the client uncover other weighty factors. Limitation 2: the good reasoning approach allows us to assess reasons for the problem presented but it does not question whether the problem presented is the one that should actually be tackled. The decision counsellor needs to help the client uncover what problem he or she wishes to tackle. Limitation 3: the good reasoning approach allows us to assess existing options but it doesnt help us generate possible options for solving the problem. The decision counsellor needs to help the client uncover other possible solutions to the problem. In Tony's case, the good reasoning approach does not help us come up with all the relevant reasons for and against going to Australia (limitation 1); it does not help us think about whether 'Should I go to Australia' is really the question Tony should be asking (limitation 2), and it does not help him think about other options rather than just going to Australia or splitting up (limitation 3). While being able to think critically is important in making wise decisions it is not sufficient. For these reasons, we need to go beyond critical thinking and look to creative thinking to complement it.

3) Creative Thinking

6 The term 'acceptable' is generally used instead of the more obvious 'true' in order to cover moral reasons as well as factual ones. We actually recommend using true with clients as acceptable for the non-philosopher can easily be assumed to imply a severe relativism and preclude critical thinking - of the 'its acceptable to me' sort.

Creative thinking is the generation of thoughts, ideas, decisions and actions, often by novel and unexpected means. Although creative thinking is often said to be an attitude of mind as much as a set of techniques, this has not stopped a large number of writers inventing a vast array of them. Here we select three that are germane to

7 Weightiness is an overall measure that takes into account acceptability, relevance and importance.

26

http://www.practical-philosophy.org.uk

Towards Wise Decision-Making III: Critical and Creative Thinking

Tim LeBon & David Arnaud

decision-making - namely brainstorming, thinking and win/win thinking 8. 3.1 Brainstorming

lateral

sort of things people might come up to start with might include: 'Get her friends and family over here' 'Take a year off work and go to Australia', 'Agree to spend six months in Australia'. The facilitator would then encourage the group to crossfertilise these ideas - which might lead to ideas like 'Agree to spend six months in Australia, then spend six months here being visited by some of her friends you've met over there'. Then they would be asked to forget inhibitions and come up with really wild ideas. These might include 'Steal her passport', 'Have an affair with someone else to make her jealous so she changes her mind', 'Threaten to kill himself ', 'Get her pregnant' and 'Propose marriage'. In terms of the three limitations of critical thinking (need to generate reasons, need to generate options, need to reframe problem), brainstorming clearly helps most with generating options. It also, to a limited extent, helps with reframing the problem (for example from 'Should I' to 'How to'). 3.2 Lateral Thinking Lateral thinking is Edward de Bono's name for a special type of creative thinking which involves 'patternswitching within a patterning system' (de Bono, 1982, p.55). It may be that a problem results from us being stuck in a certain way of looking at things, and lateral thinking advocates looking sideways at it to get a fresh perspective. One of de Bono's own examples is as follows: Grandma is knitting and young Susie is disturbing her playing with the wool. The father suggests putting Susie into the playpen. The mother suggests it might be a better idea to put Grandma in the playpen. One of De Bono's techniques to help lateral thinking is to provocatively say something which may be a stepping stone to a good idea, on the grounds that something may not be realised to be worth saying, until it has been said. De Bono invented the word 'po', derived from 'hypothesis', 'suppose' and 'possible', to indicate that one is provocatively saying something to spark new ideas. For example, faced with an urban traffic parking problem, de Bono proposed 'Po cars would limit their own parking'. This led to the idea of cars being able to park wherever they like, as long as they leave their lights on. Applying lateral thinking via 'po' to Tony's problem, we could state that 'Po the world is round'. This may suggest all sorts of ideas - for example thinking of a third place they could live, thinking of interesting places he

Brainstorming was the invention of Alex Osborn, (Osborn, 1953) and is a technique for problem-solving through the generation of ideas. Rawlinson (1986) identifies the six stages of brainstorming, as follows. 1. State and discuss the problem. 2. Restate the problem in the form 'How to' to ensure that it is a restatement, not an attempted solution. 3. Select a basic restatement from step 2) and write it down in the form 'In how many ways can we'. 4. Have a warm-up session of about 5 minutes - for example the group might be asked to think of as many uses for a CD as they can. 5. Brainstorm, recording suggested answers to the problem on a flip chart. 6. Ask the group to finish with the wildest idea they can think of (laughter and noise are good!) These stages should be kept discrete and work best with a group of about 12. Rawlinson suggests four further guidelines which make brainstorming work well, which he recommends be displayed for all to see: 1. Suspend judgement (do not evaluate). 2. Freewheel (don't have any inhibitions). 3. Value quantity (not quality). 4. Cross-fertilise (let new ideas sprout from old ones). How might a brainstorming session be applied to Tony's dilemma of whether to stay in the UK or move to Australia? At stage 2 his problem might be restated as 'How can Tony keep his relationship with Liz going?' This would then become 'How many ways can we think of in which Tony can stay with Liz?' After the warm-up stage, the group would freewheel ideas - the

8 Other creative thinking methods include attribute analysis (asking about the attributes of a problem may simplify it), wishful thinking (abstracting back from an ideal solution) and random word stimulation (opening a dictionary at a random page to stimulate ideas). For a good overview see Robert Harris's Creative Thinking Techniques (Harris, 1998) on the world wide web.

http://www.practical-philosophy.org.uk

27

Practical Philosophy

November 2001

could visit when visiting Liz, planning a round the world trip with Liz.9 Lateral thinking can clearly help us come up with new options; it can also help us 'find the best problem'.10 We should not necessarily accept a problem at face value. Anthony Weston shows how this can be applied to classic dilemmas, like that of Heinz and Sartre's student. Sartre's student's problem is posed as an ultimate choice between helping his mother and fighting for the Free French; why, asks Weston, should we be restricted to these two choices? Is the mother really as helpless as the student thinks? If not, the answer may lie in helping her realise her own resources.11 Can Tony's problem be reframed? We might ask whether Tony should take Liz's words at face value. Perhaps she is bluffing, or pleading for more say in the relationship or more commitment. Maybe the real problem facing Tony is the relationship, and the job and homesickness are pretexts.

At this point many critics accuse advocates of 'win/win' as mere idealists, but in doing so they neglect the creative technique which it is claimed allows everyone to win. The trick is to move away from specific, concrete objectives to the abstract values that lie behind them. For whilst we may not be able to secure the very specific targets we have in mind, because they might conflict with other people's specific wishes, we have a much better chance of mutual success if we think instead about the reasons why we want these things, and how else they might be accomplished. The classic example is where the husband wants the window open (say) and the wife wants it shut. How can win/win be possible here when their wishes are diametrically opposed? A compromise would be to have the window half-shut, but this would make no-one happy. Win/win asks both parties to give the reason why they want the window open or shut. Suppose the husband says he wants some fresh air in the room, whilst the wife says she does not want a draught. Now a win/win solution is apparent open a window in a nearby room, giving fresh air without a draught.13 Win/win thinking might well appeal to Tony. Whilst they cannot both be in he UK and Australia at the same time, we need to step back and ask 'For what reasons do you, Tony, want to be in the UK and for what reasons do you, Liz, want to be in Australia'. We would then build up a list of 'what matters' to each party which would be a stepping stone to finding a solution acceptable to both. Win/win thinking helps with the generation of reasons. Since brainstorming and lateral thinking cover generating options and reframing the problem this means that we now have methods to deal with all the limitations of critical thinking.

3.3

Win/Win Thinking

According to Stephen Covey, one of the seven habits of highly effective people is to 'think win/win'. As Covey says, 'Win/Win means that agreements or solutions are mutually beneficial, mutually satisfying' (1992, p.207). Covey argues that 'win/win' is a superior paradigm to aiming for 'win/lose'. This may be obvious in cases when one cares about the other person (as Tony surely does), but Covey points out that even in purely business deals 'win/win' provides a more secure, lasting foundation. 'Win/win' is also to be distinguished from mere compromise; win/win means giving the other person what they want without having to compromise. 12

9 The 'Po' sentence does not need to have any connection with the problem.

4. Critical and Creative Thinking

Is creative thinking on its own the answer then? Clearly not. Brainstorming generates many, many options, but we need to separate the wheat from the chaff. Lateral thinking (and, to some extent, brainstorming) may give us a new way of looking at the problem, but how then

10

The expression is Anthony Weston's (Weston, 1997).

11 If the problem cannot be reframed in quite such a dramatic way, lateral thinking encourages the restating of the problem in terms of 'how to' rather than 'whether' in a similar way to stages 2 and 3 of brainstorming.

Covey focuses on the interpersonal aspects of 'win/win thinking'. Actually win/win has both an intra personal dimension as well as the inter-personal one alluded to by Covey. If we have many conflicting objectives, win-win thinking asks us to think of ways that they can all be satisfied.

12

13

This example derives from Mary Parker Follett writing early in the twentieth century - though she called it 'integration' rather than 'win/win'.

28

http://www.practical-philosophy.org.uk

Towards Wise Decision-Making III: Critical and Creative Thinking

Tim LeBon & David Arnaud

do we decide whether the solutions to that problem are any good? Win/win thinking facilitates a way of thinking that may suggest mutually acceptable solutions; again, however, we need to think about not only whether they are acceptable, but also whether they are wise. Creative thinking helps us generate ideas but we also need critical thinking skills to evaluate them. We now need to use our creative and critical thinking skills at a meta level to work out a process which combines the best of each.14 First, you need to understand the situation and find the best problem; there's not much point generating or evaluating options to the wrong problem! Lateral thinking and critical thinking are vital tools here. Next, in order to facilitate win/win thinking and the evaluation of options, we should identify the elements of a good solution. This will involve critical thinking to decide whether these really are elements of a good solution. Now we are in a position to combine brainstorming and win/win thinking to generate likely options. Finally, we can assess these options in terms of the objectives identified at stage two.

importance as well as over-generalisation. Creative thinking may make a big difference in finding the best problem. As discussed, the real problem may well be Tony's relationship with Liz. If this is true, it will be a very valuable insight, and point the way towards Tony having a discussion with Liz, or possibly Liz and Tony coming together for counselling.

2. Identify the elements of a good solution ('what matters') Obviously this would depend on whether Tony was having decision counselling on his own or had asked Liz to come along too. Assuming the latter, we might draw up two lists, of what matters to Liz and what matters to Tony.

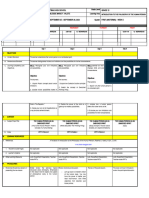

Current Concern Going to Australia

Being with Tony 4.1 Applying critical and creative thinking to Tony's dilemma We have already suggested a lot of possible insights into Tony's dilemma, but without a structure they might appear more like confusing alternatives. We will now see how the framework above might help Tony make a wise decision. 1. Understanding the situation and the finding the best problem Being with Liz Critical thinking can help with understanding the situation. Tony should avoid the fallacy of assuming that his situation is the same as his friend's Pete - the fallacy here may be as much confusing vividness with

Underlying concern(s) 1) Having a good career 2) Keeping in touch with friends and family 3) There being justice in the relationship Being with Tony

Strength

3 4 4 5

Table 2: What Matters to Liz

Current Concern Staying in the UK

Underlying concern(s) 1) Keeping in touch with his friends and family 2) Having a good career Being with Liz

Strength

3 3 5

Table 3: What Matters to Tony

14 Such a process would be in the spirit of de Bono's Six Thinking Hats (2000) where he recognises the need for both creative (Green Hat) and critical (Black Hat) thinking. We should also note that de Bono values information (white hat), red hat (emotions and intuitions) and blue hat (process). It differs in that we are doing our 'blue hat' thinking up front to try to say which type of thinking is required at which stage. We have left out red hat thinking in this article as we covered it previously. White hat thinking is included under critical thinking.

Tables 2 and 3 summarise the possible results of this stage of decision counselling with Liz and Tony. The first column shows their current concern; this is what they come into the session thinking. The next column underlying concern, is the result of having probed more deeply into why it matters. So, for example, Staying in the UK is not an end in itself for Tony; he wants to stay here in order to keep in touch with friends and family and have a good career. The final column is a rough indicator of the strength (out of five) of each underlying concern. Tables 2 and 3 suggest that Liz and

29

http://www.practical-philosophy.org.uk

Practical Philosophy

November 2001

Tony have a common concern in being with each other, but need to generate options which allow them have a good career and stay in touch with friends and a sense of justice in the relationship.

strength of 5 (the maximum). The next three columns list each option (generated at stage 3) and assess each option in terms of what matters. The bottom row (Conclusion) gives an overall assessment of whether each option should be accepted or rejected. It can readily be seen that the third option is the best; it satisfies both their sense of justice, and gives them the best chance of each finding a satisfying career and keeping in touch with friends and family.

3. Generate possible options The decision counsellor might well ask Tony and Liz to brainstorm, replacing the original problem 'Should Tony move to Australia or stay in the UK' with 'How many ways can we think of in which Liz and Tony both have a good job, keep in touch with friends and family, and be with each other?' They might come up with the following ideas: Pay at least yearly visits to their place of birth Arrange for visits of friends and family Explore career opportunities for Tony in Australia Explore career opportunities for Liz in England

The advice to cross-fertilise these options might produce an option combining several of these ideas: combined option might in fact decide that the best option combines all four of these ideas, namely: Explore career opportunities for each. Then make decision about emigration, and agree to pay yearly visits and arrange for friends to come as an option to compete with Liz going to Australia by herself or with Tony.

4. Evaluating Options Tony and Liz are now in a good position to evaluate the possible alternatives (which for the sake of exposition we will limit to being the original two options plus the option which combines a number of the ideas reaped from brainstorming).

We can assess each of the three alternative options in terms of how far they meet Liz and Tony's ultimate concerns. In effect, we are judging them by reasons we have already determined to be acceptable and relevant and strong. The best option is the one that satisfies as much as possible of the strongest concerns. The results are summarised in table 4, below. The two columns list the objectives (what matters) and their strength which have just been arrived at (in stage 3) Note this works on the underlying concerns and the strengths arrived at after some critical thinking. So Tony being with Liz has a

30

http://www.practical-philosophy.org.uk

Towards Wise Decision-Making III: Critical and Creative Thinking

Tim LeBon & David Arnaud

Option

Liz goes to Australia on her own Liz and Tony emigrate to Australia together Explore career opportunities for each. Then make decision about emigration, and agree to pay yearly visits and arrange for friends to come. Yes Yes/ to some extent Probably Yes To some extent/Yes Probably Yes

Objective (what matters)

Tony being with Liz Tony keeping in touch with his friends and family Tony having a satisfying career Liz being with Tony Liz keeping in touch with his friends and family Liz having a satisfying career Liz feeling a sense of justice in the relationship Conclusion

Strength

5 3 4 5 4 4 4 No Yes Yes No Yes Yes No

Yes No Maybe Yes Yes Yes Yes

REJECT

REJECT

ACCEPT

Table 4: Evaluating options according to Liz and Tonys objectives

5. Conclusion

Readers of our last paper will comment that emotions have been left out of the equation. This was done purely for the sake of exposition. In the full model they would appear at stage 1 (were their emotions distorting their view of the situation?) and stage 2 (what do the appropriate emotions tell us about what matters?). Some may also voice concern about stage 2 (what matters). We are assessing what matters in terms of acceptability, relevance and strength, but on what basis? Is it just the client's subjective preference ? Or is there some more objective base for deciding what really matters? We will leave such considerations for a future paper. We began by suggesting the need to harness critical and creative thinking together to help with wise decisionmaking. We believe the framework proposed does exactly this. It uses each of three creative methods (lateral thinking, brainstorming and win/win thinking) at the most appropriate stage of the decision-making process; namely framing the problem, generating reasons and

generating options. Critical thinking skills are used to complement these, using the fallacies approach to help understand the situation and asking whether the reasons generated concerning what matters in a solution are acceptable, relevant and strong. We believe that such a marriage of critical and creative thinking does indeed constitute significant progress towards wise decisionmaking.

References

Arnaud, D. and LeBon,T. (2000) Towards Wise Decision-Making 2: The Emotions, Practical Philosophy, 3, 3 Covey, S. (1992) The Seven Habits of Highly Effective People: Restoring the Character Ethic. London: Simon and Schuster de Bono, E. (1982) de Bono's Thinking Course. London: BBC Books

http://www.practical-philosophy.org.uk

31

Practical Philosophy

November 2001

de Bono, E . (2000) Six Thinking Hats. London: Penguin Engel S. M. (2000 )With Good Reason: An Introduction to Informal Fallacies. New York: St Martins Press Ennis, R. (1996) Critical Thinking. Upper Saddle River: Prentice-Hall Goman, C. (1989) Creative Thinking in Business. London: Kogan Govier ,T. (1985) A Practical Study of Argument. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth Harris, R. (1998) Creative Thinking Techniques. www: http://www.virtualsalt.com/crebook1.htm Johnson, R., and Blair, J. Anthony. (1994) Logical SelfDefense. New York: McGraw-Hill LeBon, T. and Arnaud D. (2000) Towards Wise Decision-Making 1: Decision-Analysis, Practical Philosophy, 3, 1 LeBon, T. (2001) Wise Therapy: Philosophy for Counsellors. London: Continuum Osborn, A. (1953) Applied Imagination. New York: Scribners Raabe, P. (2000) Philosophical Counselling. Westport, Connecticut: Praeger Rawlinson, J. (1986) Creative Thinking and Brainstorming. London: Gower Thomson, A. (1999) Critical Reasoning in Ethics: A Practical Introduction. London: Routledge Warburton, N. (1996) Thinking from A to Z. London: Routledge Weston, A (1997) A Practical Companion to Ethics. Oxford: OUP

Tim LeBon has worked for many years as a counsellor and therapist using philosophical ideas and methods. His first book Wise Therapy: Philosophy for Counsellors has recently been published by Continuum. His e-mail address is timlebon@aol.com. David Arnaud has worked for a number of years as a lecturer in philosophy and psychology. He is now embarking on a PhD integrating philosophical and psychological material on decision-making and writing a book about the same. His e-mail address is davidarnau@aol.com.

32

http://www.practical-philosophy.org.uk

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- Buy-In (Review and Analysis of Kotter and Whitehead's Book)D'EverandBuy-In (Review and Analysis of Kotter and Whitehead's Book)Pas encore d'évaluation

- 4-3 24 LeBon - Decision Making 3Document9 pages4-3 24 LeBon - Decision Making 3michaelcheungPas encore d'évaluation

- 10 valuable insights into the ancient Stoic thought for successful investingD'Everand10 valuable insights into the ancient Stoic thought for successful investingPas encore d'évaluation

- Introduction To The Study of Logic Part 1 and Part 2 of SyllabusDocument23 pagesIntroduction To The Study of Logic Part 1 and Part 2 of SyllabusKMA1320Pas encore d'évaluation

- Correction without criticism: A guide to having emotionally tough conversationsD'EverandCorrection without criticism: A guide to having emotionally tough conversationsPas encore d'évaluation

- Critical Thinking Chapter 2Document12 pagesCritical Thinking Chapter 2VbaluyoPas encore d'évaluation

- Chapt4 EL AmDocument59 pagesChapt4 EL AmPramod Surya MakkenaPas encore d'évaluation

- Critical Thinking BasicsDocument61 pagesCritical Thinking BasicsMohd SyamilPas encore d'évaluation

- Module 2.1 3 PhiloDocument16 pagesModule 2.1 3 PhiloJomel SobrevillaPas encore d'évaluation

- Addiction Definition EssayDocument8 pagesAddiction Definition Essaygatxsknbf100% (2)

- Critical ReasoningDocument15 pagesCritical ReasoningZafar ShaikhPas encore d'évaluation

- 1607592032criticalreasoning EbookDocument135 pages1607592032criticalreasoning EbookSimanta MridhaPas encore d'évaluation

- The Power of Critical Thinking: Chapter ObjectivesDocument8 pagesThe Power of Critical Thinking: Chapter ObjectivesOVS TutoringPas encore d'évaluation

- Screenshot 2023-02-09 at 16.34.54Document28 pagesScreenshot 2023-02-09 at 16.34.54Supriyaa MagarPas encore d'évaluation

- Prime Minister by Bobby OngkojoyoDocument31 pagesPrime Minister by Bobby OngkojoyoAzizun HakimPas encore d'évaluation

- 1701253233critical Reasoning EbookDocument75 pages1701253233critical Reasoning EbookYaswanth Reddy PutluruPas encore d'évaluation

- English9 Q4 M2Document16 pagesEnglish9 Q4 M2Skyler MontalvoPas encore d'évaluation

- Critical ThinkingDocument6 pagesCritical ThinkingMia ČomićPas encore d'évaluation

- Essays On DepressionDocument7 pagesEssays On Depressionb7263nq2100% (1)

- Malfunctions of CommunicationDocument9 pagesMalfunctions of CommunicationJitu NovomePas encore d'évaluation

- Creativity Is The Ability To Develop Good Ideas That Can Be Put IntoDocument5 pagesCreativity Is The Ability To Develop Good Ideas That Can Be Put Intomtim360Pas encore d'évaluation

- Facts Inferences Judgement PDFDocument14 pagesFacts Inferences Judgement PDFSarthakPas encore d'évaluation

- Fact Inference Judgement - Tips To Solve FIJ Questions in CAT ExamDocument14 pagesFact Inference Judgement - Tips To Solve FIJ Questions in CAT ExamSarthakPas encore d'évaluation

- Discussion Paper-Expressing Opiniions in PublicDocument7 pagesDiscussion Paper-Expressing Opiniions in PublicchinawhitePas encore d'évaluation

- Euthyphro's ChoiceDocument5 pagesEuthyphro's ChoiceMichael YongPas encore d'évaluation

- ArgumentDocument36 pagesArgumentAhmad Fahrurrozi ZSPas encore d'évaluation

- English 9 Q4 Weeks 1 8Document44 pagesEnglish 9 Q4 Weeks 1 8mariannxxcPas encore d'évaluation

- AT SkeptDocument4 pagesAT SkeptagentnachosPas encore d'évaluation

- Debate SimplifiedDocument30 pagesDebate Simplifieddyane000Pas encore d'évaluation

- Ptcas EssayDocument5 pagesPtcas Essayzobvbccaf100% (2)

- 9gold Q4English CastillonDocument6 pages9gold Q4English CastillonNow OnwooPas encore d'évaluation

- Essay About AdviceDocument8 pagesEssay About Advicevotukezez1z2100% (2)

- Analytical Listening & Problem SolvingDocument5 pagesAnalytical Listening & Problem SolvingJennefer Gudao AranillaPas encore d'évaluation

- checkedLAS Intro-to-Philo MELC6Document16 pagescheckedLAS Intro-to-Philo MELC6Jenny Rose PaboPas encore d'évaluation

- English 6 Q3 W2Document47 pagesEnglish 6 Q3 W2Jay Mark AlascoPas encore d'évaluation

- Strategies For Argument RefutationDocument11 pagesStrategies For Argument RefutationLinh DangPas encore d'évaluation

- Critical Reading As Looking For Ways of ThinkingDocument52 pagesCritical Reading As Looking For Ways of ThinkingRyan BustilloPas encore d'évaluation

- English I - Week 4.student - VersionDocument31 pagesEnglish I - Week 4.student - VersionMaricica FloreaPas encore d'évaluation

- M3 Critical Thinking - SSY1 - 2023 - UpdatedDocument51 pagesM3 Critical Thinking - SSY1 - 2023 - Updatedelbertpc8205Pas encore d'évaluation

- Persuasive Against MyselfDocument4 pagesPersuasive Against Myselfwillmalson100% (1)

- How To WriteDocument26 pagesHow To WritecikgusitizPas encore d'évaluation

- Cirtical Thinking Review Questions Mr. IsmaelDocument8 pagesCirtical Thinking Review Questions Mr. IsmaelKura .DlshkawPas encore d'évaluation

- Purcom Week 8Document13 pagesPurcom Week 8Ryan Jhes TolentinoPas encore d'évaluation

- Reference Module 10Document10 pagesReference Module 10Princess CastilloPas encore d'évaluation

- Persuasive EssayDocument2 pagesPersuasive EssayClaire Maldia JaramillaPas encore d'évaluation

- The Acceptability of Reasons: Including Their Credibility: Chapter-6Document38 pagesThe Acceptability of Reasons: Including Their Credibility: Chapter-6Rojan Joshi20% (5)

- Critical Thinkingproper PPDocument195 pagesCritical Thinkingproper PPSaleem KholowaPas encore d'évaluation

- Eapp Week 6Document59 pagesEapp Week 6Sam Louis PangilinanPas encore d'évaluation

- Unit 1 Arguments - L1Document8 pagesUnit 1 Arguments - L1Muskan LonialPas encore d'évaluation

- Communication Theory ChapterDocument13 pagesCommunication Theory ChapterMia SamPas encore d'évaluation

- Chapter 2 ARQ Tenth EdDocument7 pagesChapter 2 ARQ Tenth EdKLaingReyPas encore d'évaluation

- Critical Thinking LearningDocument16 pagesCritical Thinking Learningmeow li100% (4)

- Critical ThinkingDocument3 pagesCritical ThinkingWidita AndiniPas encore d'évaluation

- Logical and Critical Thinking The University of AucklandDocument60 pagesLogical and Critical Thinking The University of AucklandelenabbardajiPas encore d'évaluation

- Chapter 2Document18 pagesChapter 2Alyssa Ashley A. ImamPas encore d'évaluation

- Introductiontophilosophy 11 Quarter 1 SLM 2Document29 pagesIntroductiontophilosophy 11 Quarter 1 SLM 2MITCHANGPas encore d'évaluation

- Lesson 2 Methods of Philosophizing - Day 1 4Document72 pagesLesson 2 Methods of Philosophizing - Day 1 4Vergel D. JudalPas encore d'évaluation

- Engl MidtermDocument25 pagesEngl MidtermMeeka CalimagPas encore d'évaluation

- EfoloiactivityDocument7 pagesEfoloiactivityapi-287771244Pas encore d'évaluation

- Introduction For Argumentative EssayDocument8 pagesIntroduction For Argumentative Essayafhbgdmbt100% (2)

- NTS GAT (General) GUIDE BOOK by DOGAR PUBLISHER PDFDocument372 pagesNTS GAT (General) GUIDE BOOK by DOGAR PUBLISHER PDFwaqasahmadz86% (977)

- The CSS Point - Everyday Science BookDocument84 pagesThe CSS Point - Everyday Science BookMaxhar AbbaxPas encore d'évaluation

- Marketing Plan of Haleeb Milk Pakistan: Sir Naveed AltafDocument13 pagesMarketing Plan of Haleeb Milk Pakistan: Sir Naveed AltafMaxhar AbbaxPas encore d'évaluation

- The Nature of Strategic ManagementDocument17 pagesThe Nature of Strategic ManagementMaxhar AbbaxPas encore d'évaluation

- Strategic ManagementDocument27 pagesStrategic ManagementMaxhar AbbaxPas encore d'évaluation

- Project On Pakistan Petroleum: Sir Waseem UllahDocument20 pagesProject On Pakistan Petroleum: Sir Waseem UllahMaxhar AbbaxPas encore d'évaluation

- Analysis of Financial Statements: BY Rana Asghar AliDocument31 pagesAnalysis of Financial Statements: BY Rana Asghar AliMaxhar AbbaxPas encore d'évaluation

- The Launch of Ariel by The Procter and Gamble PakistanDocument2 pagesThe Launch of Ariel by The Procter and Gamble PakistanMaxhar Abbax100% (1)

- Developing New Products FOR Global MarketsDocument37 pagesDeveloping New Products FOR Global MarketsMaxhar AbbaxPas encore d'évaluation

- The Case of The Sikh TempleDocument3 pagesThe Case of The Sikh TempleMaxhar AbbaxPas encore d'évaluation

- Internship Report On Tapal Tea (PVT) Ltd.Document63 pagesInternship Report On Tapal Tea (PVT) Ltd.Maxhar AbbaxPas encore d'évaluation

- History of Pakistan Cricket Board (PCB) : Domestic Cricket Is Further Divided in AssociationsDocument10 pagesHistory of Pakistan Cricket Board (PCB) : Domestic Cricket Is Further Divided in AssociationsMaxhar Abbax0% (1)

- Qualitative or Quantitative in NatureDocument2 pagesQualitative or Quantitative in NatureMaxhar AbbaxPas encore d'évaluation

- The Misuse of LPG Has Come Down After Capping The Cylinder To Nine, Says BPCL ChiefDocument4 pagesThe Misuse of LPG Has Come Down After Capping The Cylinder To Nine, Says BPCL ChiefMaxhar AbbaxPas encore d'évaluation

- Ranking of Universities and Higher Education Institutions For Student Information Purposes?Document158 pagesRanking of Universities and Higher Education Institutions For Student Information Purposes?Maxhar AbbaxPas encore d'évaluation

- Lecture1 Competitive AdvantageDocument16 pagesLecture1 Competitive AdvantageMaxhar AbbaxPas encore d'évaluation

- Decision Support Tools For Process Design and Selection: Soorathep Kheawhom, Masahiko HiraoDocument9 pagesDecision Support Tools For Process Design and Selection: Soorathep Kheawhom, Masahiko HiraoMaxhar AbbaxPas encore d'évaluation

- Qualitative or Quantitative in NatureDocument2 pagesQualitative or Quantitative in NatureMaxhar AbbaxPas encore d'évaluation

- Chemical Process Route Selection Based On Assessment of Inherent Environmental HazardDocument6 pagesChemical Process Route Selection Based On Assessment of Inherent Environmental HazardMaxhar AbbaxPas encore d'évaluation

- Outline of Academic Disciplines - WikipediaDocument11 pagesOutline of Academic Disciplines - WikipediamtkliemaPas encore d'évaluation

- Essay 7232 Writing Correction Task 2Document5 pagesEssay 7232 Writing Correction Task 2yousef shabanPas encore d'évaluation

- Le Senne - The DutyDocument14 pagesLe Senne - The DutyFitzgerald BillyPas encore d'évaluation

- A Systemic Design Method To Approach Future Complex Scenarios and Research Towards Sustainability: A Holistic Diagnosis ToolDocument30 pagesA Systemic Design Method To Approach Future Complex Scenarios and Research Towards Sustainability: A Holistic Diagnosis ToolJames MaddinsonPas encore d'évaluation

- World Handbook of Existential TherapyDocument10 pagesWorld Handbook of Existential TherapyFaten SalahPas encore d'évaluation

- Sri Krishna Arts and Science Computer Technology: Course Coordinator Dr. V. S. Anita Sofia Prof. & HeadDocument78 pagesSri Krishna Arts and Science Computer Technology: Course Coordinator Dr. V. S. Anita Sofia Prof. & HeadAnita Sofia VPas encore d'évaluation

- Methods of Scientific ThinkingDocument11 pagesMethods of Scientific ThinkingHana AdivaPas encore d'évaluation

- The Verstehen PositionDocument7 pagesThe Verstehen Positionapi-31417059Pas encore d'évaluation

- Transcendental and Gothic ProjectDocument6 pagesTranscendental and Gothic Projectapi-250753975Pas encore d'évaluation

- Zaltman Metaphor Elicitation TechniqueDocument3 pagesZaltman Metaphor Elicitation TechniqueMuskanPas encore d'évaluation

- Natural Law MIDTERMS!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!Document5 pagesNatural Law MIDTERMS!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!![AP-STUDENT] John Patrick AmoraPas encore d'évaluation

- Observation of Reading ComprehensionDocument2 pagesObservation of Reading ComprehensionNaning Ahya pratiwiPas encore d'évaluation

- The Mediator Role of Organizational Justice Percep PDFDocument17 pagesThe Mediator Role of Organizational Justice Percep PDFLicense Sure ReviewersPas encore d'évaluation

- Comte de GabalisDocument176 pagesComte de Gabalis895508Pas encore d'évaluation

- Cote 2.2 1Document32 pagesCote 2.2 1Enkhgerel MunkhbatPas encore d'évaluation

- Does Regionalism Challenge GlobalisationDocument3 pagesDoes Regionalism Challenge GlobalisationOggie FebriantoPas encore d'évaluation

- William James On Habit - Brain PickingsDocument9 pagesWilliam James On Habit - Brain PickingsrajPas encore d'évaluation

- Nietzsche - Critical AnalysisDocument7 pagesNietzsche - Critical Analysisdizenz0750% (2)

- READINGS IN PHILLIPPINE HISTORY Topic 1Document7 pagesREADINGS IN PHILLIPPINE HISTORY Topic 1Angel Joy LunetaPas encore d'évaluation

- Chapter 3Document18 pagesChapter 3chtganduPas encore d'évaluation

- Philippine Politics MODULE 4Document14 pagesPhilippine Politics MODULE 4jonas arsenuePas encore d'évaluation

- Dll-Philo W5Document5 pagesDll-Philo W5BLESSIE MARIE VALETEPas encore d'évaluation

- ICB Cultural Dilemma 6Document2 pagesICB Cultural Dilemma 6Mahamud AbdiPas encore d'évaluation

- Chapter Xvii Discretionary Powers (I)Document12 pagesChapter Xvii Discretionary Powers (I)Harshita RanjanPas encore d'évaluation

- Alex Wayman Millennium of Buddhist Logic Vol1 PDFDocument376 pagesAlex Wayman Millennium of Buddhist Logic Vol1 PDFderenif100% (2)

- SHS Report Card - Grade11Document14 pagesSHS Report Card - Grade11Roxan Marie Mendoza Cruz100% (3)

- Ihum3011 TQF 3 UpdatedDocument18 pagesIhum3011 TQF 3 Updatedgladz25Pas encore d'évaluation

- Weighted Hinge QuestionsDocument10 pagesWeighted Hinge QuestionsBPas encore d'évaluation

- STD 8 Cre Schemes-Of-WorkDocument16 pagesSTD 8 Cre Schemes-Of-WorkJOSEPH MWANGIPas encore d'évaluation

- Ethical Studies On Leadership in Improving The Quality of Performance and Institutional ImageDocument7 pagesEthical Studies On Leadership in Improving The Quality of Performance and Institutional ImageInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyPas encore d'évaluation

- Love Life: How to Raise Your Standards, Find Your Person, and Live Happily (No Matter What)D'EverandLove Life: How to Raise Your Standards, Find Your Person, and Live Happily (No Matter What)Évaluation : 3 sur 5 étoiles3/5 (1)

- ADHD is Awesome: A Guide to (Mostly) Thriving with ADHDD'EverandADHD is Awesome: A Guide to (Mostly) Thriving with ADHDÉvaluation : 5 sur 5 étoiles5/5 (3)

- The Age of Magical Overthinking: Notes on Modern IrrationalityD'EverandThe Age of Magical Overthinking: Notes on Modern IrrationalityÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (30)

- LIT: Life Ignition Tools: Use Nature's Playbook to Energize Your Brain, Spark Ideas, and Ignite ActionD'EverandLIT: Life Ignition Tools: Use Nature's Playbook to Energize Your Brain, Spark Ideas, and Ignite ActionÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (404)

- Raising Good Humans: A Mindful Guide to Breaking the Cycle of Reactive Parenting and Raising Kind, Confident KidsD'EverandRaising Good Humans: A Mindful Guide to Breaking the Cycle of Reactive Parenting and Raising Kind, Confident KidsÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (170)

- By the Time You Read This: The Space between Cheslie's Smile and Mental Illness—Her Story in Her Own WordsD'EverandBy the Time You Read This: The Space between Cheslie's Smile and Mental Illness—Her Story in Her Own WordsPas encore d'évaluation

- The Ritual Effect: From Habit to Ritual, Harness the Surprising Power of Everyday ActionsD'EverandThe Ritual Effect: From Habit to Ritual, Harness the Surprising Power of Everyday ActionsÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (4)

- The Body Keeps the Score by Bessel Van der Kolk, M.D. - Book Summary: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of TraumaD'EverandThe Body Keeps the Score by Bessel Van der Kolk, M.D. - Book Summary: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of TraumaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (266)

- Raising Mentally Strong Kids: How to Combine the Power of Neuroscience with Love and Logic to Grow Confident, Kind, Responsible, and Resilient Children and Young AdultsD'EverandRaising Mentally Strong Kids: How to Combine the Power of Neuroscience with Love and Logic to Grow Confident, Kind, Responsible, and Resilient Children and Young AdultsÉvaluation : 5 sur 5 étoiles5/5 (1)

- Summary: The Psychology of Money: Timeless Lessons on Wealth, Greed, and Happiness by Morgan Housel: Key Takeaways, Summary & Analysis IncludedD'EverandSummary: The Psychology of Money: Timeless Lessons on Wealth, Greed, and Happiness by Morgan Housel: Key Takeaways, Summary & Analysis IncludedÉvaluation : 5 sur 5 étoiles5/5 (81)

- Think This, Not That: 12 Mindshifts to Breakthrough Limiting Beliefs and Become Who You Were Born to BeD'EverandThink This, Not That: 12 Mindshifts to Breakthrough Limiting Beliefs and Become Who You Were Born to BeÉvaluation : 2 sur 5 étoiles2/5 (1)

- The Marshmallow Test: Mastering Self-ControlD'EverandThe Marshmallow Test: Mastering Self-ControlÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (60)

- Manipulation: The Ultimate Guide To Influence People with Persuasion, Mind Control and NLP With Highly Effective Manipulation TechniquesD'EverandManipulation: The Ultimate Guide To Influence People with Persuasion, Mind Control and NLP With Highly Effective Manipulation TechniquesÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (1412)

- Cult, A Love Story: Ten Years Inside a Canadian Cult and the Subsequent Long Road of RecoveryD'EverandCult, A Love Story: Ten Years Inside a Canadian Cult and the Subsequent Long Road of RecoveryÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- Why We Die: The New Science of Aging and the Quest for ImmortalityD'EverandWhy We Die: The New Science of Aging and the Quest for ImmortalityÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5)

- Summary: Thinking, Fast and Slow: by Daniel Kahneman: Key Takeaways, Summary & Analysis IncludedD'EverandSummary: Thinking, Fast and Slow: by Daniel Kahneman: Key Takeaways, Summary & Analysis IncludedÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (61)

- Dark Psychology & Manipulation: Discover How To Analyze People and Master Human Behaviour Using Emotional Influence Techniques, Body Language Secrets, Covert NLP, Speed Reading, and Hypnosis.D'EverandDark Psychology & Manipulation: Discover How To Analyze People and Master Human Behaviour Using Emotional Influence Techniques, Body Language Secrets, Covert NLP, Speed Reading, and Hypnosis.Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (110)

- Troubled: The Failed Promise of America’s Behavioral Treatment ProgramsD'EverandTroubled: The Failed Promise of America’s Behavioral Treatment ProgramsÉvaluation : 5 sur 5 étoiles5/5 (2)

- Mindset by Carol S. Dweck - Book Summary: The New Psychology of SuccessD'EverandMindset by Carol S. Dweck - Book Summary: The New Psychology of SuccessÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (328)

- The Secret of the Golden Flower: A Chinese Book Of LifeD'EverandThe Secret of the Golden Flower: A Chinese Book Of LifeÉvaluation : 5 sur 5 étoiles5/5 (4)

- Summary: Limitless: Upgrade Your Brain, Learn Anything Faster, and Unlock Your Exceptional Life By Jim Kwik: Key Takeaways, Summary and AnalysisD'EverandSummary: Limitless: Upgrade Your Brain, Learn Anything Faster, and Unlock Your Exceptional Life By Jim Kwik: Key Takeaways, Summary and AnalysisÉvaluation : 5 sur 5 étoiles5/5 (8)

- Empath: The Survival Guide For Highly Sensitive People: Protect Yourself From Narcissists & Toxic Relationships. Discover How to Stop Absorbing Other People's PainD'EverandEmpath: The Survival Guide For Highly Sensitive People: Protect Yourself From Narcissists & Toxic Relationships. Discover How to Stop Absorbing Other People's PainÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (95)

- The Garden Within: Where the War with Your Emotions Ends and Your Most Powerful Life BeginsD'EverandThe Garden Within: Where the War with Your Emotions Ends and Your Most Powerful Life BeginsPas encore d'évaluation

- The Courage Habit: How to Accept Your Fears, Release the Past, and Live Your Courageous LifeD'EverandThe Courage Habit: How to Accept Your Fears, Release the Past, and Live Your Courageous LifeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (253)

- Outlive: The Science and Art of Longevity by Peter Attia: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisD'EverandOutlive: The Science and Art of Longevity by Peter Attia: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1)

- When the Body Says No by Gabor Maté: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisD'EverandWhen the Body Says No by Gabor Maté: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2)