Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

21 2goodwin

Transféré par

Aytaç KöktürkDescription originale:

Titre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

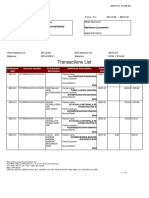

21 2goodwin

Transféré par

Aytaç KöktürkDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

More Than a Laughing Matter: Cartoons and Jews

George M. Goodwin

Modern Judaism, Volume 21, Number 2, May 2001, pp. 146-174 (Article)

Published by Oxford University Press

For additional information about this article

http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/mj/summary/v021/21.2goodwin.html

Access provided by Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin - Preussischer Kulturbesitz (6 Mar 2014 08:47 GMT)

George M. Goodwin

MORE THAN A LAUGHING MATTER: CARTOONS AND JEWS

INTRODUCTION

Cartoons can bring so many rewards: pleasure, joy, insight, and wonder. They can be drawn from countless lines or only a stroke. Whether inundated with words or remaining utterly silent, they can bring forth surprising recognition, shock, and anger. Indeed, cartoons can be masterful inventions, giving perfect form to thought and feeling. Though they embellish newspapers, magazines, and books, cartoons are not limited to publications. A staple of film, television, and video, cartoons are occasionally recycled as musical theatre.1 As animation has become computerized, computers seem inanimate without goofy calligraphy, characters, and websites. Cartoons have infiltrated numerous other realms, from toys and games to advertising, packaging, clothing, merchandising, sports, and tourismeven such a weighty domain as architecture.2 Who would deny that at the end of the Clinton presidency (or dawn of the Ventura governorship) they seem emblematic of our entire culture? For centuries Jews have participated in the world of cartoons, but seldom as artists or viewers.3 Usually, Jews have been victims of ridicule and hatred. Throughout Europe they have been portrayed as demons ugly, lecherous, grasping, and evilunlike other humans.4 In America too there have been periods when Jews have been viciously maligned and stereotyped.5 And even today numerous hate groups vilify Jews through monstrous characterizations. Thus it may seem ironic that American Jewry has produced so many distinguished cartoon artists.6 Can any other ethnic group lay claim to comparable riches? We are eager to proclaim Jewish contributions to all facets of American life, especially the arts, where nearly every medium and genre has been touched by Jewish warmth, hope, and compassion. As scores of writers, performers, and entertainers have demonstrated, laughter may be our most magical gift and potent weapon. Thus, it is disappointing to see how, at the end of the last century, the world of Jewish cartoon art was so glumly acknowledged. A Jewish

Modern Judaism 21 (2001): 146174 2001 by Oxford University Press

Cartoons and Jews

147

museum, for example, had not yet mounted an engrossing exhibition. No cartoons were reproduced in Grace Grossmans gorgeous coffee-table volume, Jewish Art.7 In his otherwise glowing study, In Search of American Jewish Culture, Stephen Whitfield had little to say about this medium.8 Such neglect is partially offset by the handy new American Jewish Desk Reference, which serves as a kind of Jewish hall of fame for general readers and students.9 Scores of fine artists are included, but only four cartoonists. There have been few theoretical studies of cartoonswhy they are made and their salient characteristics.10 Perhaps a litmus test would seem foolish (or the worthy subject of still another cartoon book). To stay fresh, nimble, and outrageous the best cartoonists shirk criticism and skirt tradition. Surprisingly, the world of cartoons has found less a target than a niche in higher education. While no university has yet offered a degree in humor studies, cartoons have invaded academic discourse under the rubric of popular culture.11 Universities have published scholarly studies of comic strips.12 Dr. Seuss, Charles Schulz, and Gary Trudeau have received honorary degrees. Within the academic realm of art history, however, cartoons are still regarded as preliminary studies for such large-scale commissions as frescoes, tapestries, and stained-glass.13 Leonardo, Bernini, and the Carracci family are rightfully regarded as pioneers of caricature, but cartoon art seems to have reached its apogee in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries with Hogarth, Rowlandson, and Daumier.14 Only a tiny number of specialized institutions collect cartoons.15 Opinions are deeply divided over their importance. Many scholars dismiss them as gimmicky, tedious, and insipid. Others believe, at an opposite extreme, that all cartoonsthe seedier the betterdecode profound mysteries of modern (and postmodern) society. A third group of observers, representing a middle ground, recognize qualitative differences. They appreciate exceptional cartoons, which show originality, nuance, and depth. Cartoons can function on many different and sometimes contradictory levels, however. Aesthetic quality and popularity are not mutually exclusive criteria. Indeed, cartoon readers make their own judgments, with or without the experts acquiescence. Succeeding for all kinds of reasons, cartoons may be heart-warming, frightening, shocking, blasphemous, and erotic. In 1990 the Museum of Modern Art presented a groundbreaking exhibition and publication, High and Low: Modern Art and Popular Culture.16 Such masters as Picasso, Miro , Klee, and Dubuffet were seen in a bold, new light. Intrigued by caricature, cartoons, and graffiti they exaggerated, distorted, and mutilated the human figure to unleash

148

George M. Goodwin

modernisms sublime fury. High and Low also demonstrated how such younger American artists as Lichtenstein, Oldenburg, and Warhol fashioned a full-blown style from the imagery of consumer culture and comics. Arts sacred power to redeem and uplift also became a weapon to subvert and mock. Is there an explanation, other than their love of laughter, why so many Jews have become cartoon artists? An anti-authoritarian attitude is surely useful. Pain and suffering also help. Not many professions thrive on mischief, irreverence, and insubordination.17 There have been few barriers restricting Jews. Cartooning requires no particular preparationacademic or artistic. There is no licensure or much overhead. The very young can gain a foothold, and the elderly can remain as long as they astonish. By living in big cities, especially New York, Jews have enjoyed unlimited access to outstanding art museums, art schools, and all facets of entertainment. New York also boasts countless publishers and publications. No doubt, cartoonists flourish through some sense of camaraderie and competition. More important, Jews have been keen observers of urban life. Whether native-born or new Americans, Manhattan residents or commuters, they are bewildered, stressed, and confused by their surroundings. A bad hair day is almost every dayor an entire epoch. Quite naturally, Jews identify with outsiders and underdogs. Further, they are not afraid of speaking up. Like class clowns, many Jewish cartoonists clamor for attention. As idealists, however, Jews believe in a civil, just, and humane society. They respect the rule of law, democratic institutions, informed voters, and progressive causes. While seeking truth, kvetching becomes quite satisfying. Things could get much worse. Quick to notice frailties and foibles, Jewish cartoonists most acutely recognize their own likenesses in the mirror. They are simultaneously amused and appalled. The following pages highlight Jewish contributions to American cartoon art during the twentieth century. Among a constellation of candidates, six artists are profiled, representing such overlapping categories as political cartoons, caricatures, comic strips and books, panel cartoons, and underground cartoons. Though few of these artists have been religiously observant, all deserve closer scrutiny within a broad Jewish context.

GOLDBERG

Since its inception in 1922, the Pulitzer Prize for editorial cartooning has been won by at least one Jew.18 In 1948 it was bestowed upon Reu-

Cartoons and Jews

149

ben Lucius Goldberg (18831970), known throughout America and to many generations as Rube Goldberg. His popularity as a creator of comic strips far outweighs his contribution to editorial pages, however. To some extent Goldbergs Pulitzer was a fluke. Both Herblock and Bill Mauldin, young veterans of World War II, had already claimed their first Pulitzers (in 1942 and 1945). By the 1950s, cartoon art would become reinvigorated by many new publications. Whether or not there was a need, Goldberg was seen as a wise, elder statesman. Though he was widely regarded as a Jewand occasionally received anti-Semitic hate mailGoldberg had little personal interest in Judaism or Jewish organizations. So why did he cling to his name? It was easily identifiable, and perhaps the first meant more than his last. But he also seemed proud that a Jew could gain such national celebrity. Born in San Francisco, he grew up in an atmosphere where Jews faced little discrimination.19 The Bay Areas Jewish eccentrics included Emperor Norton as well as his own father, Max, who was born in Prussia and went West before the Civil War. As a successful entrepreneur and a Republican ward boss, the elder Goldberg held various positions, including fire chief and police commissioner. He enjoyed playing poker on Friday evenings. Rubens mother, Hannah Cohen, who was born in Northern California, died before all her brood reached adulthood. Since boyhood, Ruben, a southpaw, drew funny faces. He admired the prolific work of Frederick Burr Opper (18571937), Americas first leading Jewish cartoonist.20 He of course drew for the student paper at Lowell High School and on Friday evenings took art lessons from a sign painter. Though his father wanted him to attend West Point or Annapolis, Ruben reached a compromise by studying engineering at the University of California. Awed by the Guggenheim familys exploits, he emphasized mining. Upon his graduation from Berkeley in 1904, Goldberg worked briefly for San Franciscos engineering department, then tried cartooning. From The Chronicle he moved to The Bulletin, where he developed a following as a sports illustrator. A superior encouraged him to pursue writing. In 1907 Goldberg left for New York City, as Opper had departed from northeastern Ohio, to seek his fortune. He quickly found a job at The Evening Mail and launched a cartoon strip, the first of more than sixty that preceded his switch to editorial pages. Though some lasted only a few years, about half of these strips lasted at least five years. Seven comic strips ran for more than two decades. He created some 50,000 wacky drawings. Among Goldbergs most enduring strips were: Benny Sent Me (191434), Boob McNutt (191534), Foolish Questions (190934),

150

George M. Goodwin

Mike and Ike, They Look Alike (191534), and The Weekly Meeting of the Tuesday Ladies Club (191234). But the favorite, running a half-century (19141964), the same length as Schulzs Peanuts, was The Inventions of Professor Lucifer Gorgonzola Butts. In the mundane Goldberg found wonders. His characters may have been foolish, but they were not necessarily fools. They reflected and complemented his readers self-perceptions. Like Alexander Calder, the inventor of mobiles, Goldberg put his engineering education to good use. Between 1914 and 1934, he created hundreds of ridiculous machines. These absurd but delightful contraptions, such as A Simple Way to Sharpen Ice Skates and How to Keep the Divorce Rate Down, burnished his fame. Never having fancied himself as an artist, Goldberg had even less use for the avant-garde. Yet, as a homespun humorist similar in outlook to Will Rogers (or Garrison Keillor), he was pulled in many directions. He achieved early success as a vaudevillian. After settling in New York, he wrote nearly fifty stories for such magazines as Vanity Fair, Saturday Evening Post, and Cosmopolitan. Goldberg also published ten books, which included collections of drawings. Hoping to reach ever larger audiences, he hosted radio and television broadcasts. He also tried screenwriting and wrote lyrics for three musical comedies. At the height of his career, Goldberg was the most popular and best paid cartoonist in America. In the mid-1920s, when the Hearst chain offered him $50,000 per year, The Evening Mail met the challenge by establishing its own syndicate for him. In 1928 the frustrated engineer earned an astounding $125,000. By the mid-1930s, however, Goldbergs popularity began its decline. During the depths of the Depression, when Americans were hungry for humor, every newspaper allocated space for the funny papers. Goldberg could not compete with younger, brighter talents. After failing with two new strips, Doc Wright and Lala Palooza, he admitted defeat. Goldberg was brought out of early retirement and to political cartooning by New Yorks Evening Sun. Beginning in 1938, his cartoons appeared three times per week. By 1942 they appeared five times, but still without syndication. When the Evening Sun ceased publication in 1950, he was hired by the New York Sun. This represented a symbolic victory: the prestige of a Hearst masthead. Goldberg received his Pulitzer for a cartoon captioned Peace Today, which was published on July 22, 1947. It was a remarkably simple drawing, showing a huge atomic bomb hanging over a precipice (world control) and falling into a void (world deconstruction). Placed atop the bomb was a scene of domestic oblivion: a husband,

Cartoons and Jews

151

wife, child, and dog seated outside their cozy home. Today it is difficult to comprehend why or how this drawing gained much attention. It would appear in retrospect that Goldberg had few gifts for editorial cartooning. Once a masterful interpreter of slang and banterincluding such words as boob, loon, bunk, and baloneyhe grew to mistrust language. More significantly, Goldberg was not passionate about world affairs. Having hobnobbed with numerous presidents, he was perhaps too well connected. As a Republican, he met editorial expectations with repeated criticism of big government. Worst of all, Goldberg was not outlandish or zany. During the Cold War, Goldberg seemed even further adrifta Lawrence Welk ambushed by Elvis or Dylan. He opposed labor unions and the United Nations. He admired Senator Joseph McCarthy. Confused about Korea, Vietnam, and the Middle East, he grew increasingly obtuse. He chose not to renew his contract when it expired in 1964. In his final years Goldberg sought vindication. His experiments with oil painting were humiliating, however. Perhaps in emulation of Daumier, he turned to sculpture, and his bronzes of animals were exhibited commercially. In a further bid for immortality, he also donated some of his papers to Berkeley. Goldberg lived long enough to attend the opening of a retrospective exhibition, Do It the Hard Way, which was presented by the Smithsonians National Museum of History and Technology rather than a neighboring art museum. Sadly, his celebrity outlasted his extraordinary inventiveness.

HIRSCHFELD

Albert Hirschfeld has practiced his craft for more than seven decades, most frequently and prominently on the pages of The New York Times. He has published several coffee-table volumes, and a Manhattan gallery, Margo Feiden, deals exclusively with his drawings and limitededition prints. Hirschfeld has also been lauded through film. The Line King, a documentary, was nominated in 1996 for an Academy Award; and a segment in Disneys Fantasia/2000 mimics his style. Twice during the 1990s he received commissions for postage stamps. Like Howard Pyle, N. C. Wyeth, and Norman Rockwell Hirschfeld is beloved. Yet the artists popularity is misleading. He is not merely an entertainer, whose use of the hidden epigram NINA brings perpetual amusement to Times readers. Though he has resisted serious portraiture by a historian or a journalist, he has thought deeply about his craft and such ill-fitting labels as cartoonist and caricaturist. Yet, having

152

George M. Goodwin

written about problems of language, aesthetics, and perception he has discovered few underlying truths.21 Most disillusioning to Hirschfelds viewers is a simple fact: his art appears deeply intuitive, but it is highly studied. So he remains largely an enigmaeven unto himself. Born in St. Louis in 1903, he spent his earliest years far outside the art world.22 His father, Isaac, a salesman from Albany, was a third-generation American. His mother, Rebecca, had emigrated from the Ukraine. Perhaps the boy inherited an appreciation for pantomime because his parents had difficulty speaking to each other. Judaism, though a subtext of his life and career, did not bind the Hirschfeld family. No doubt Albert was a prodigy. In 1914, accepting the advice of a local art teacher, his parents moved (with two other sons) to New York City. Having left high school at age sixteen, Al worked briefly as an office boy. While taking classes at the National Academy of Design and the Art Students League, he worked as an artist for Goldwyn, Selznick, and the Warner Brothers in the new motion picture business. By twenty-one years of age, he had saved enough money for a Parisian sojourn. Initially attracted to sculpture and later to painting, Hirschfeld dreamed of becoming a fine artist. He quickly discovered, however, that a drafty garret didnt suit his pleasures. He wanted to reach a large audience. Back in Manhattan he churned out commercial art by day and editorial cartoons by night. Though technically proficient, his lithographs for The Masses were overbearing and didactic. His hatred of Father Coughlin, for example, could not be expressed in a personal or nuanced manner. Hirschfelds entre e to the world of caricature occurred in 1926, when a friend helped him submit a theatrical portrait to The New York Herald Tribune. Thus began an assignment, including a period as a Moscow correspondent, which lasted twenty years. He also published ink drawings in numerous other papers, such as The Brooklyn Eagle, The Morning Telegram, and The New York Times. He produced books in collaboration with S. J. Perelman and William Saroyan and later authored his own, Show Business Is No Business. Hirschfelds extraordinary stylehis endlessly flowing, weaving, and dancing linetook hold within a few years. Having portrayed theatre in all of its guisescircus, burlesque, vaudeville, comedy, drama, the musical, and opera, as well as movies and televisionhe has continually refined and purified his vision. That is, rendering humanity through the clearest, simplest, but most startling means. It has been a remarkable challenge, resulting in a singular achievement. How, for so many decades, did Hirschfeld pull it off? There are

Cartoons and Jews

153

only clues. He launched his career during caricatures heyday, when numerous newspapers and magazines competed for top talent.23 He also experienced an extraordinary epoch in American theatre, when live entertainment not only abounded, but was suffused with glamour and larger-than-life performers. Hirschfeld, the former revolutionary, was also fortunate to glimpse a world of high fashion: top hats, tuxedoes, patent leather shoes, gowns, gloves, and diamonds. Black and white were not the absence of color but its quintessence. Art Deco itself was exuberant ornamentation. Though he may have taken liberties to disguise them, Hirshfeld was responsive to a wide array of stimuli. These included facets of the European avant-garde, such as Picassos mutability, Chagalls whimsy, and Miro s wit. Through travel and study he was further intrigued by Javanese shadow puppets and Japanese prints. Despite the acuity of his gaze, Hirschfeld never considered himself a critic who offered opinions about productions. (Werent they all impressive?) Rather, he gave himself the more demanding task of describingif possible, recreatingthe experience of performance. Hirschfeld worked hard at his endeavor. He frequently previewed shows outside New York and sketched backstage. He also taught himself an in-the-dark method of notation, combining words and key images. Only upon returning to the barbers chair in his Upper East Side studio would he begin the highly calculated process of composition. Perhaps Hirschfelds story of rapid and sustained development is in some small sense disappointing. Within only a few decades, he achieved perfection. Had he perished accidentally at forty, he would be remembered as an exceptional artist. By 1961, however, with the publication of The American Theatre as Seen by Hirschfeld, he had completed the equivalent of a full career. Hirschfeld created cartoons of increasing complexity and on a far larger scale: murals for a theatre in New York, a hotel in Miami, and a worlds fair pavilion in Brussels. He toyed with political caricature, but was, surprisingly, unconvincing. Presidents and congressmen came to resemble other performers, which, in a bizarre way, many were. So in a further display of virtuosity, Hirschfeld invented new theatrical roles for favorite performersZero Mostel playing Peter Pan, for example. The irony was that Hirschfeld had become both Mostel and Olivier, as each had excelled at comedy and drama. As a visual artist, he became more accomplished than a writer of short stories or a poet fixated on sonnets. Within narrow physical constraints and limited intellectual parameters, Hirschfeld created his own epic. His drawings were as voluptuous as Noguchis marbles and as sensuous as Rothkos oils. His manipulation of line was perhaps exceeded only by Calders, which eventually fused metal, air, sound, and water.

154

George M. Goodwin

As a master of dance, Hirschfeld had already surpassed Busby Berkeley and perhaps rivaled Jerome Robbins. But his portraits of Danny Kaye and Marcel Marceau, with flapping arms and spinning legs, seemed sadly artificial. Perhaps filmmaking beckoned. In a strange and haunting way, Hirschfeld, at the very height of his career, found himself boxed in. Genius encountered gridlock. With one or two acts to follow, the magician needed a new bag of tricks. Could he have saved some for a finale? Perhaps there is a side of Hirschfeld the world does not yet know.

EISNER

Long before Hirschfelds caricatures were championed by The New York Times, comic books were considered the dregs of cartoon art. Published primarily for children, they glorified escapist behavior. Violence was glorified through epic battles between super-heroes and supervillains. Superman, which debuted in 1939, was the archetype created by Joseph Shuster and Jerry Siegel, two Jewish teenagers from Cleveland.24 Will Eisner, a cartoon artist reared on Alex Raymonds Flash Gordon and Milton Caniffs Terry and the Pirates, made an important name for himself both as the father of his own strip and as a developer of instructional comics. His most fascinating work occurred even later in his career, when he developed the idea of graphic novels. As both a writer and a draftsman, Eisner has vividly explored his complicated identity as a Jew. He is one of the few Jewish cartoon artists to have done so. Born in New York City in 1917, Eisner has always seen the world in terms of urban conflict and struggle.25 Not merely dramatic, his city is rife with violence, cruelty, and betrayal. Wills father, Samuel, an immigrant from an Austrian shtetl, trained as an oil painter in Vienna. He worked on Second Avenue as a set painter and designer in Yiddish theatre. Wills mother, Fannie, was born on a voyage from Russian persecution. Throughout her life she suffered recurring incidents of anti-Semitism as well as economic and emotional deprivation. Will, reared in tenements in Brooklyn and the Bronx, experienced both Christian and Jewish bigotry. As a child he displayed artistic and manual gifts, which were encouraged by his adoring father. Movies and popular fiction also fed his imagination. Eisner drew for student publications and designed theatrical productions at DeWitt Clinton High. Before graduating in 1936, he sold

Cartoons and Jews

155

his first comic to Wow! magazine. He also attended classes on scholarship at the Art Students League. Eisner never fantasized about becoming a fine artist, however. To begin making a living, he worked briefly in the advertising department of The New York American and as an illustrator for Eve, a Jewish womens magazine. By 1937 he and a friend established their own art studio, churning out comics for publishers. Will produced five strips, in five styles, under five names. He was soon supervising a staff of twenty assistants, but sold out in 1939 to start a new venture. While residing and working in New York, he formed a partnership with the Des Moines Register and Tribune to produce a sixteenpage comic insert. This syndicated supplement, known as The Weekly Comic Book, reached 1.5 million readers. Though Eisner sought an adult audience, he was required to produce a comic strip of super-heroes. The Spirit debuted in June, 1940 and continued through October, 1952. Consisting of 645 episodes, including weekly and later daily installments, the strip eventually filled nearly 5,000 pages. At the height of its popularity, The Spirit was published in twenty Sunday papers and was enjoyed by more than five million readers. The strip also ran as a separate comic book between 1941 and 1954 and enjoyed a brief life through radio broadcast. Denny Colt, the lead character, was a masked private investigator who miraculously escaped death in order to battle Dr. Cobra, a mad scientist. Colt was not always victorious, however, because Eisner was interested in characterization as action. He also invented several femmes fatales, including Lorelei Rox, Autumn Mews, Sparrow Fallon, and PGell. Decades before Robert Culp and Bill Cosby teamed up on television, Colts sidekick was Ebony White, one of comics first major African-American characters. Eisners extraordinary skills as a draftsman might have served him well as a painter or a printmakerperhaps even as an architect. He trained numerous assistants, including Jules Feiffer, long associated with The Village Voice, who earned a Pulitzer for editorial cartooning in 1986. While serving in the army during World War II, Eisners comic strip was scripted and drawn by his staff. Upon his discharge in 1946 he reluctantly returned to The Spirit, but eventually rejected its popularity. Beginning with Private Dogtag, a comic strip for Aberdeen Proving Ground, he discovered new opportunities for his talents. When reassigned to the Pentagon, he developed comic strips as instructional tools. In Army Motors, Pvt. Ona Ball demonstrated the proper methods of preventive maintenance; Joe Dope, the improper methods. Eisner

156

George M. Goodwin

also conceived and edited Firepower, an enormously popular ordnance manual. Eisners own instructional publishing company, American Visuals, lasted two decades. Its clients included the American Medical Association, the American Dental Association, Girl Scouts, the Department of Labor, and General Motors. Eisners most successful endeavor in this era was the army magazine P.S., a preventive maintenance monthly featuring Joe Dope, which ran from the Korean through the Vietnam wars. Seeing himself as an educator, Eisner also taught cartoon art at New York Citys School of Visual Arts between 1972 and 1984. A primer, using examples of his work, was published as Comics & Sequential Art in 1985.26 Beginning in the mid-1970s, Eisner sought to bridge his dual interests in entertainment and instruction. Though perhaps aware of William Blake and Victor Hugo, he was at a loss for other models.27 James Thurber, for example, was far more accomplished as a humorist than as a draftsman. Thus, to a large degree, Eisner has invented or popularized a new genre, which is more weighty than a deluxe comic book. Each graphic novel, consisting of up to 200 pages, requires several hours of careful attention. A page may have up to eight scenes, spilling beyond rectangular panels. Some pages have only one scene, either from a towering or a hovering perspective. Words tend to propel a story, but Eisner has sought a symbiotic relationship between text and image. Some pages are saturated with dialogue; others have none. Except for colorful covers, the graphic novels tend to be drawn in black and white, further conveying an eerie, film-noir quality. Eisner has been primarily concerned with how humble and broken characters achieve salvationa sense of decency and fulfillment. Yet, many of his novels lack heroes. For lovers of funny papers, these are surprisingly gritty and grim stories, wholly unappealing to children. Eisners first graphic novel, A Contract with God and Other Tenement Stories, was drawn in sepia tones. Published in 1978, it has enjoyed numerous reprintings and six translations, including Yiddish. Eisner could not read or speak his parents tongue, but he clearly opened his heart to words of endearment and approbation. The letters of God in the title are drawn to resemble Hebrew. All four stories in Contract are set in the same gloomy neighborhoodidentified as Dropsie Avenue in the Bronxbut each has its own characters, plots, and subplots. The title story involves a thoughtful orphan, Frimme Hersh, who, having survived a pogrom in his Russian village, is sent to New York. Following the death of his beloved daughter, Rachele, he abandons his

Cartoons and Jews

157

holy contract. Only upon seeing the wickedness of his ways, Hersh is struck down by a heart attack. Other morality tales in Contract involve: a family destroyed by vanity and drink; the death of a lonely lecher; and adulterous affairs at Catskill resorts. There are numerous scenes of nudity and intercourse. Eisner has created nearly twenty graphic novels, which have been published by Dennis Kitchens Kitchen Sink Press in Northampton, Massachusett. One of the most moving, published in 1991, is To the Heart of the Storm, an autobiographical saga set in 1942. While riding a troop train from New York to basic training, the author recalls assorted traumatic experiences with his parents, neighbors, and friends. Eisners most recent novel, A Family Matter, published in 1998, is even more disturbing. As a grandfather celebrates his ninetieth birthday, five conniving children plan for their inheritance. As a group, Eisners disturbing graphic novels confront entrenched notions of literature. Can illustration aspire to high art in the medieval tradition? Against considerable odds, Eisner has prevailed as a fearless and gripping storyteller.

KURTZMAN

For decades, Harvey Kurtzman (19241993) enjoyed a loyal following among devotees of cartoon art. No doubt his obsession with accuracy and detail placed limits on his productivity. Yet, the impact of his creativity has been substantial, if not universal. Kurtzman spent almost his entire life and career in greater New York City.28 Born in Brooklyn and reared in the Bronx, he eventually worked out of his home in Mt. Vernon. His father, David, who emigrated from Russia, died when he was a small child. Fortunately, his stepfather, a steel engraver, recognized the boys precociousness. As a youngster Harvey drew with chalk on sidewalks, attracted attention in school, and took classes at Pratt Institute and the Brooklyn Museum. At twelve years of age, when requesting a job application from Disney studios, he no doubt disguised his leftist upbringing. At thirteen Kurtzman was admitted to the prestigious High School of Music and Art. As a fan of such comic strips as Tarzan, Popeye, and Dick Tracy, he was largely self-educated, however. His first comic strip, Ikey and Mikey, was clearly inspired by Goldberg. Kurtzman won a scholarship to Cooper Union, where he attended evening classes for one year. Before breaking into the cartoon business, his lifelong passion, he labored as a sign painter and as a printers apprentice. Kurtzmans luck turned when he was hired at Classic Com-

158

George M. Goodwin

ics. Having learned to ink other artists drawings, he began to write his own stories. Between 1942 and 1945 he served as an army draftsman, drawing cartoons and designing training aids. Though never sent overseas, he developed a deep interest in combat. After World War II, Kurtzman freelanced in New York Citys burgeoning comic book industry. One memorable assignment was an antivenereal disease comic for Columbia University. By the early 1950s, however, Kurtzman found a foothold at Entertainment Comics, a small but successful publishing house begun by Max Gaines, a former elementary school principal who forsaw an educational use for comics in Picture Stories from the Bible. Maxs son, William, attracted a cadre of Jewish nudniks, including Al Feldstein, another World War II veteran and New York University graduate. While EC sought new niches in horror and science fiction, Kurtzman expanded in still another direction, adventure comics, which coincided with the Korean War. Kurtzman became well known for two series of comic books, Two Fisted Tales (195053) and Frontier Combat (195154), whose stories he wrote, designed, and edited. Interested in visualizing a concept, Kurtzman relied on a highly gifted team of assistants. His collaborators included many classmates from Music and Art, especially Jack Davis, Will Elder, and Wallace Wood. To portray the drudgery, suffering, and misery of the trenches, Kurtzman studied news clippings, researched weaponry, and interviewed soldiers. Dramatic effects were achieved through a bold and concise style of storytelling. Like Eisner, he sought a cinematic approach to illustration. Indeed, Kurtzman saw himself as a behind-thescenes cartoonist, directing a team of masterful collaborators. By the fall of 1952, EC needed a more profitable series, Kurtzman a new challenge. A new publication, planned as a parody of horror comics, soon acquired a much broader scope. Besides advertising, television, movies, music, and fashion it spoofed every other facet of Cold War consumer culture and mores.29 An immediate success, ECs Mad Magazine became known throughout America and, because of thirteen foreign editions, in numerous countries.30 (As a so-called magazine, which accepted no advertising, the ten-cent rag was not beholden to the self-imposed rules of the Comics Code Authority, established in 1954.31) A new title, Mad, was created by Feldstein, but the first twenty-eight issues (through July, 1956) were Kurtzmans brainchild. Generations of summer campers, Sunday school students, high school idlers, and homesick servicemen became subscribers. At its zenith in 1973, Mad had 2.4 million readers.

Cartoons and Jews

159

If ever a comic book exemplified sophomoric humor, it was this cockamamie undertaking. Kurtzman was responsible for numerous ideas, not the least being the trademark character, Alfred E. Neuman, and his slogan, WhatMe Worry? Kurtzman did not actually invent the imbecilic urchinthe antithesis of Disney wholesomenessbut found his likeness in early twentieth century illustration. Indeed, the most famous nerd in cartoon history was initially known as Melvin Coznowski. The Neuman moniker was borrowed from the eminent Jewish film composer, Alfred Newman. Though a cover boy and a mascot, Neuman never actually inhabited his own comic strip. Rather, with only a toothy grin, he presided over all of the comic books absurd contents. Mad, the most original and successful satirical magazine of the postwar era, exerted an enormous impact on stand-up comedy, records, television, movies, and adolescent behavior. There were numerous spin-offs, from Cracked to Brand Echh to National Lampoon. EC exploited its popularity through more than a hundred Mad anthologies. The magazines most popular artists, such as Mort Drucker and Al Jaffee, published an even larger number of cartoon collections. Ironically, Kurtzmans own later efforts were largely unsuccessful. After a bitter falling-out with Gaines over editorial control and ownership, he left Mad to launch several other humor magazines with his own retinue of jesters. Hugh Hefner became the publisher of Trump, a lavish publication lasting only two issues. Humbug, launched in 1957, lasted eleven issues. Help!, which mixed humorous photographs with cartoon dialogue, ran from 1960 to 1965. Realizing that his strengths lay outside business, Kurtzman also wrote and drew for such magazines as Madison Avenue and Esquire. The Mad creator does deserve acclaim for a long-running comic strip, perhaps the most expensively produced in magazine history. This was Little Annie Fanny, a parody of Harold Grays Little Orphan Annie, which ran in Playboy for 106 episodes between 1962 and 1988. Originally a bimonthly strip, it generated such huge labor and production costs that it eventually appeared only a few times per year. But Hefner was an exceptional publisher and editor, who, before Playboy, had sought a career as a cartoonist.32 Though Little Annie Fanny helped usher in an era of sexual liberation and hedonism, it soon collided with an equally potent social revolution, that of womens liberation. Annie was the bulbous blonde beach babe (perhaps Alfred E. Neumans older sister) who epitomized sexual naivete and exploitation. Yet, her misadventures seemed merely naughty compared to ensuing waves of erotic and pornographic publishing. Between 1973 and 1990 Kurtzman taught cartooning at New Yorks School of Visual Arts. Before succumbing to cancer, he pub-

160

George M. Goodwin

lished anthologies of early drawings. Alas, his autobiography, a grandfatherly guide for children, made no reference to Ms. Fanny.33

STEINBERG

If ever an artist defied categorization, it was Saul Steinberg (1914 1999), best known over six decades for more than 600 drawings in The New Yorker. In an ironic reflection of his own considerable interest in birds, he has been squeezed into numerous pigeonholes. In the latest edition of Whos Who in American Art, for example, he was labeled most conveniently as cartoonist.34 In the authoritative Dictionary of Art, he was identified as a draughtsman, painter, sculptor, and cartoonist.35 In the Dictionary article on caricature, his was the only drawing representing the twentieth century. Though never recognized by a Pulitzer committee, Steinberg received in 1974 the Medal for Graphic Art from the American Academy of Arts and Letters. Writing in the journal Architecture, the esteemed critic Peter Blake called him by far the most brilliant architectural critic in the United States in the past half century.36 Perhaps his most fitting accolade was found in the headline of his front-page obituary in The New York Times, where he was proclaimed an epic doodler.37 Steinberg was ignored by the International Cartoon Museums Hall of Fame. Like Hirschfeld, he never received The Reuben, the statuette sculpted by Goldberg for the National Cartoonists Society.38 He is rarely mentioned in the voluminous cartoon literature. Yet, from the outset of his American career, Steinberg was recognized at the avant-gardes loftiest levels. In 1946 he was included in an important group exhibition, Fourteen Americans, at the Museum of Modern Art. He soon participated in the Whitneys Annual, Pittsburghs Carnegie International, and shows throughout Europe and South America. Steinberg was represented by such prestigious dealers as Betty Parsons, Sidney Janis, Pace, and Maeght. In 1950 he received an eight-page spread in the premiere issue of Portfolio, the visionary but short-lived magazine of graphic art edited by Alexey Brodovitch for George Rosenthals Zebra Press. The artist received hundreds of reviews in art publications, and he socialized with leading abstract painters and sculptors, even finding a vacation home near East Hampton among them. Despite the waves of recognition, Steinberg, like Hirschfeld, eluded close personal scrutiny. He would have been an ideal subject for a profile in his own New Yorker. Even by 1978, when honored with a major retrospective at the Whitney Museum (only a block from his home), he escaped close biographical examination.39

Cartoons and Jews

161

The outlines of Steinbergs career have been clearly drawn.40 In 1914 he was born in Ramnicul-Sarat, a small town near Bucharest.41 His father, Maurice, a printer and bookbinder, became a manufacturer of cardboard boxes. His mother, Rosa Jacobson, a homemaker, produced fancifully decorated pastry. Steinberg was reared in Bucharest, graduating from secondary school in 1932. His sister, a painter known professionally as Lica Roman, later resided in Paris. Steinberg studied sociology and psychology at the University of Bucharest before enrolling in the architecture faculty of Milans Reggio Politecnico. He graduated with a doctor of architecture degree in 1940. The study of architecture, he later remarked, is a marvelous training for anything but architecture.42 Italy was an ideal place to encounter the remnants of defunct principalities as well as a new empires gropings. Fascinated by the trappings of power, he grew to enjoy all manifestations of pomp and spectacle. His keen eye for the ridiculous found an outlet in Bertoldo, a humor magazine. Though multilingual and cosmopolitan, it is not known to what degree the Steinbergs were religiously observant. The issue remained somewhat academic, for the familys losses during the Holocaust probably substantialwere never revealed. Already published in Harpers Bazaar and Life, Steinberg sought an American visa. A friend and agent in New York was unable to provide assistance, however. From Italy Steinberg fled to Lisbon, where he obtained passage to New York City. Refused entry, he was sent to Santo Domingo. As the philosopher and art critic Arthur Danto has observed, this was the perfect place, following Columbus example, to disembark in the New World.43 By 1941, he was permitted entry to Miami, where he boarded a bus for Manhattan. Further assistance with immigration was arranged by The New Yorker, where, along with PM, his drawings began to appear.44 Throughout his life Steinberg was obsessed by documentation visas and passports, but also licenses and diplomas. He issued all kinds of spurious records. Steinbergs professional development was both delayed and accelerated by military service. Drafted in 1942, he did not return to New York until 1944, by which time he was naturalized and married to Hedda Lindenberg Sterne, a Romanian-born painter. Assigned to an elite Air Force intelligence unit, Steinberg traveled widelyto India, China, North Africa, and Italywhere he drew extensively. Many of his delicate ink sketches, showing GIs amidst foreign cultures, were published in Life, Time, and The New Yorker. Steinbergs book, All in Line, the first of eight, appeared in 1945. It included several silly drawings of Hitler, Mussolini, and Hirohito.

162

George M. Goodwin

Though he had not yet developed a signature style, Steinbergs witty and elegant drawings seemed well suited to Harold Rosss debonair weekly, which had debuted in 1925.45 Itself difficult to categorize, The New Yorker contained gossip, news, profiles, humor, fiction, poetry, criticism, and classy advertisements. Cartoons were not unusual for such a smart periodical, but as they disappeared from other magazines, they became The New Yorkers most beloved feature.46 Here were comics for those who disdained the Sunday funnies or juniors trashy journals. Steinbergs early drawings harmonized with vignettes by such established artists as Garrett Price, Gardner Rea (who created the trademark Eustace Tilly character), and Otto Soglow.47 Usually consisting of only one scene, these were known as panel or gag cartoons. Many were conceived in collaboration with gag writers, who suggested playful scenarios or captions. Some of Steinbergs wartime sketches received such superfluous amendations as No Mail, Taxi, or Siesta, but they never needed punchlines. In time, the artist would provide his own verbage, which became inseparable from his imagery. If difficult to categorize Steinbergs occupation, it is even more vexing to say what his art is about. Though often minutely drawn, it is panoramic in scope. Rarely humorous, its deals with deep, philosophical issues: mysterious essentials or essential mysteries. Steinbergs musings exist on a level of complexity far beyond Goldbergs contraptions or Eisners melodramas. In many ways he was the opposite of his longtime New Yorker colleague, William Steig (born 1907), who grew more sentimental and adorable with age.48 Among other artifacts of human invention, Steinberg was taken by vehicles: bicycles, motorcycles, automobiles, taxis, trains, ships, and planes. He was fascinated by all aspects of the built environmentnot only homes, motels, offices, and courthousesbut plazas, boulevards, and byways.49 The ultimate voyager, Steinberg was intrigued by all kinds of landmarks, labyrinths, and mapsmanmade and metaphysical. Though nearly every drawing is populated by humans, Steinberg was not particularly sympathetic toward this species. He found as much enjoyment in predatory creatures, particularly cats and crocodiles.50 Like Boschs or Beckmanns, many of Steinbergs animals are half human or half beast, and some of his his humans are entirely bestial. Perhaps Steinberg felt more orphaned than mothered by nature. He clearly enjoyed trees and gardens, but was also awed by the vastness of plains, deserts, and oceans. Often isolated and dwarfed by their surroundings, people seem large only in their imagination. The most famous of his eighty-five covers for The New Yorker, published on March 29, 1976, framed a view of the world from across Ninth Avenue. Representing a peak not only in the artists career but

Cartoons and Jews

163

in all of cartoon history, it was imitated in countless renditions from Bangkok to Boston. Fascinated by both speed and distance, he was also preoccupied by timewhich showed either the presence or absence of history. But the future, as represented by Modern and Art Deco buildings, seemed decadent and uninviting. America epitomized Steinbergs concerns about scale, hierarchy, government, sport, materialism, and nature. He was both attracted and repelled by his countless odysseys. For all of Americas freedom, prosperity, and energy, he discovered much loneliness, melancholy, and desolation. Contrary to the comic stip tradition, Steinberg did not invent his own characters. Neither did he caricature politicians or celebrities. Instead, he harkened back to the allegories of Thomas Nast and Frederick Opper. His favorite symbols were the Statue of Liberty, Uncle Sam, Uncle Tom, and Abraham Lincoln, but he also celebrated the bald eagle, Thanksgiving turkey, Santa Claus, and the Easter Bunny. Indeed, all could dine peacefully without devouring one another. Steinbergs favorite cartoon character was Mickey Mouse, depicted as a menacing or deranged predator.51 Indeed, all of the artists drawings reconfigured and regurgitated cartoon history. Balloon-shaped dialogue became another victim. Steinberg was fascinated by the entire creative process, often represented by music. Every orchestral sound became audible through his calligraphy. While still in Italy he represented the visual arts through a hand, a mirror, or a painters studio. Almost anything in sequenceletters, punctuation marks, dates, and numberswere similarly malleable. Perhaps the austerity of Steinbergs early pen-and-ink drawings was misleading. He employed pencil, charcoal, pastel, crayon, watercolor, wash, and temperaoften in various combinations. In the fullest Cubist tradition, which Hirschfeld once mimicked, Steinberg mastered the language of collagemixing graph paper, musical notations, photographs, finger prints, and rubber stamps. He also created masks from paper bags and murals from paper fragments.52 Trompe loeil effects superimposed on actual tabletops were showcased in his Whitney retrospective. Many writing and drawing implements, which looked like found objects, were carved or painted. Sculpture, however, was probably Steinbergs least convincing foray. The artists career displayed surprising consistency and growth. As he developed self-assurance, he sought greater candor. His abandonment of control over drawing was simply another illusion. Always festive, Steinbergs sense of color grew intentionally garishas if to connect and critique Le ger and Lichtenstein. Indeed, Steinbergs palette brightened as his message darkened.

164

George M. Goodwin

The artists brooding late work was clearly his boldest. He tickled death through the motif of a sauntering skeleton. Perhaps this was his tribute to the great Mexican cartoon artist Posada or his allusion to the grotesquerie that had descended upon his birthplace and people.

SPIEGELMAN

Among a younger generation of American cartoon artists, Art Spiegelman (born 1948) has garnered unusual honors. His two-volume masterwork, Maus: A Survivors Tale, once rejected by numerous publishers, has received extraordinary critical and popular acclaim. Both the first volume, subtitled My Father Bleeds History (1986), and the second, subtitled And Here My Troubles Began (1991), were nominated for National Book Critics Circle Awards. In 1992 Maus received a Pulitzer Prizethe first ever presented as a special award. Published in its final format by Pantheon Books (now owned by Bertelsmann), Maus has sold hundreds of thousands of copies and has been translated into eighteen languages.53 Yet everything about Maus seems implausible. For lack of a better description, it is a Holocaust comic bookor a true graphic novel. Consisting of nearly two thousand tiny panels, all composed in black and white, it incorporates several spoken, written, and gestural languages. Maus is biography and autobiography, history and ethnography. Existing in the past and the present, it darts back and forth between the two. Though mostly horrifying, the work is occasionally comical. All humans are portrayed as animals, and some also wear animal masks. Though eager to condemn Europes bigoted cartoon history, Spiegelman also exploits the theme of miserliness. Unlike Aesop or Orwell, Maus is neither fable nor allegory. Why did such suffering occur? Who or what was responsible? What are the costs of survival? Why does suffering persist? Maus offers no conclusion, explanation, or salvation. Complex and contradictory on many levels, Maus also seems somewhat implausible because of its artist-author. Was Spiegelman poorly equipped to tell such a harrowing tale, or was he the natural candidate? Born in Sweden, he came to America when he was only three. He had few relatives, no siblings, and deeply troubled parents. Spiegelman had little religious education, a weak Jewish identity, and only a vague understanding of the calamity that devoured Poland. For better or worse, he lived in Rego Park, a quite ordinary neighborhood in Queens. Spiegelmans only goal in life was to become a cartoonist. Before graduating from New Yorks High School of Art and Design, he published drawings in the Long Island Post and began a lengthy relationship

Cartoons and Jews

165

with Topp, a chewing gum company, where he drew baseball cards and Bazooka comics. As an undergraduate at the State University of New York at Binghamton, Spiegelman studied art and philosophy and worked on campus publications. Having suffered a mental breakdown, he committed himself to a hospital, where he remained several months. He was then shaken by his mothers suicide. Leaving school to journey to San Francisco, Goldbergs hometown, he discovered the national incubator of underground comics.54 Sold in headshops with psychedelic posters and drug paraphernalia, these outrageous comic books, inspired by Kurtzman, were produced in small quantities for a tight circle of devotees. Dubbed comix because of their X-rated content, they celebrated a triumvirate of Sex, Dope, and Cheap Thrills. In flagrant defiance of the Comics Code, many underground cartoons were obscene, sexist, and racistalso raucously funny.55 Like most other newcomers to the underground movement, Spiegelman was inspired by R. Crumb (born 1943), a wildly gifted, prolific, and freewheeling artist trained in Cleveland at Jacob Sapirsteins American Greetings.56 Well known for his ribald characters, his grimy streetscapes, and the slogan Keep on Truckin, Crumb has been hailed as the underground comics Mozart.57 His grungy creations and Steinbergs late work are fused by the same manic energy. During his San Francisco sojourn, which lasted until 1975, Spiegelman drew and wrote for a slew of underground publications, such as Choice Meat, Young Lust, Real Pulp, and Bizarre Sex. While editor of Arcade and Douglas Comix, he also taught at the San Francisco Academy of Art. In 1972, two decades before his Pulitzer Prize, Spiegelman began experimenting with the concept of Maus. He created Micky, a three-page cartoon strip for Funny Aminals (sic), showing cute mice, with big noses, ears, and whiskers, being tormented by cats.58 The felines were identified as die Katzen, but there were no explicit references to the Holocaust. Mice have long intrigued cartoonists. Besides Disneys, there have been Supermouse, Atomic Mouse, and Eek and Meek. Cartoon cats have included: Krazy Kat, Ciceros Cat, Felix the Cat, Calculus Cat, and Garfield. Crumb himself created Fritz the Cat. And a comic strip featuring a cat and a mouse, Tom and Jerry, has been around for more than three decades.59 Spiegelman would probably not have known that cat and mice imagery had existed in an American lithographic cartoon published in 1861. It showed a cat (Uncle Abe) chasing Confederate states.60 The artists second progression toward Maus occurred in 1973, when he created Prisoner on the Hell Planet, a haunting, four-page

166

George M. Goodwin

story for Short Order Comics, which was reprinted (as if an insert) on pages 100 to 104 in the first volume of Maus. Less the story of his mothers suicide and funeral, it deals with the impact of her death. Horror resounds from its exaggerated style, which accentuates black, emulates woodblock printing, and mimics the imagery of German Expressionism. Except for the use of Hebrew and a superimposed photograph, most of these shrill effects were abandoned in Maus. Spiegelman needed to learn much more about his family and the Holocaust. This called for a deeper, perhaps more satisfying, relationship with his father. The artists dramatic disappointments, however, were reflected on the final pages of both volumes. The Spiegelman saga evolved through installments in Raw, the artists own underground, large-format publication begun in 1980 with Franc oise Mouly, his French-born wife. Perhaps a grandson of Mad, this magazine was a compendium of outrageous humor and graphics by relatively unknown American and foreign artists. Each eye-popping issue boasted a new subtitle, such as The Graphic Magazine for Postponed Suicides and The Graphic Magazine That Lost Its Faith in Nihilism. Initially published in runs of 5,000, Raw is now available through reprints from Pantheon. By the close of the first volume of Maus, the Spiegelmans had only reached the gates of Mauschwitz. Yet, readers could feel and hear these characters, whose mouths opened only to scream in wordless agony. For installments in Raw leading to the second volume, Spiegelman received support from the Guggenheim Foundation. When the free world has become deluged with Holocaust testimonies, documentaries, memorials, and museums, few works rival the originality, delicacy, or completeness of Maus.61 Perhaps the only comparable work in recent years has been Roberto Benignis Academy Award-winning movie, Life Is Beautiful. It too stands tradition on its head: finding a new and compelling use for an omnipotent subject and medium. One of Spiegelmans least-known honors was bestowed by the Museum of Modern Art. In December, 1991 and January, 1992before he received his Pulitzerall 269 pages of Maus, as well as many preparatory studies, photos, and tape recordings, received their own exhibition.62 Among cartoon artists only Steinberg, in his 1978 Whitney retrospective, had received such adulation. Spiegelman later enjoyed exhibitions in Jewish and contemporary art museums throughout America and Europe. The artist continues to publish Raw, draw for such mainstream publications as Playboy and The Village Voice, and teach at the School of Visual Arts. But since 1986, had there been any lingering doubt, he can no longer be considered an underground artist.

Cartoons and Jews

167

Beginning in 1993, under Tina Browns editorship, he has been a frequent contributor to The New Yorker. To make the magazine trendier and hipper, several young and emerging artists have been featured also Hirschfeld. With well over two-dozen covers to his credit, Spiegelman has become one of the weeklys most touted and controversial. His first cover, of February 15, 1993, was perhaps his most blasphemous. Drawn to celebrate Valentines Day and commemorate riots in Crown Heights, it shows a Hasid and a young black woman embracing. Such an image is of course heretical to Orthodox Jews (and maybe others), but it seems horribly misguided for an artist regaled for his sensitivity. This cover may outlive most Steinbergsas one of the magazines worst accomplishments. Speigelmans cover of September 13, 1993, also seems undignified and tasteless. The brightly colored painting shows grade-schoolers brandishing machine guns and ammunition, a horrible premonition of the massacre at Columbine High School. There were other graspings for attention. News R Us, published on September 11, 1995, depicts three toddlers cutting out newspaper hats from such words as drugs, rape, and terrorist bombers. Theology of the Tax Cut, from April 14, 1995, shows the Easter Rabbit crucified in a business suit against an I. R. S. form. For the cover of May 20, 1996, a procession of college graduates has help wanted pages wrapped around their diplomas. Spiegelmans humorous covers, being apolitical, poke fun at snowmen, summer bugs, and the magazine itself (Eustace Tilley dressed as Dick Tracy). But thus far, the artist may be as far out of his element as when Goldberg and Hirschfeld turned to editorial pages. Perhaps Spiegelman will reassert his skill, imagination, and moral authority through the graphic novel format, telling readers more about his marriage, children, and growing Jewish identity. A happy omen appeared in the issue of February 14, 2000, when, portrayed as a chainsmoking mouse, he paid homage to Charles Schulz. Could Spiegelman become eclipsed by a strange, new underground? Ben Katchor, whose strip Julius Knipl, Real Estate Photographer appears in several newspapers, has published The Jew of New York, a novel set in the nineteenth century.63 Even more astounding is the English translation of Vittorio Giardinos A Jew in Communist Prague, which deals sympathetically with the plight of one Jonas Finkel.64

CONCLUSION

Whether highbrow or lowbrow, ours or theirs, Jewish cartoon artists in America have contributed to a welter of publications. These in-

168

George M. Goodwin

clude The New York Times and The New Yorker as well as the Sunday funnies, Mad, Playboy, and Raw. Jewish cartoon artists have created characters and stories that have left temporary and lasting marks on the American imagination. Consider: Professor Lucifer Gorgonzola Butts, NINA, Denny Colt, Ebony White, Joe Dope, Frimme Hersh, Alfred E. Neuman, Little Annie Fanny, and the Spiegelman family. These artists have condemned intolerance and injustice, opposed nuclear war, taught soldiers to fight and maintain weapons, captured the beauty of theatrical illusion, and questioned the patterns and rhythms of our ordinary lives. For a very small price and a moments indulgence, these artists have lifted our spirits, engaged our intellects, and challenged our complacency. Yet, the cartoon artists lot has never been easy. Disappointment and hardship abound. Professional awards have been perhaps the most fickle measures of success. While Goldbergs importance as an editorial cartoonist was surely exaggerated by his Pulitzer, the world would probably know little of Spiegelman without his. Fortunately, we know who these artists really are: Rube, Al, Will, Harvey, Saul, and Art. No more and no less. For the most part, uneducated but driven men with big eyes, quick hands, clever minds, and noble hearts. Sadly, with the exception of Steinberg, many cartoonists have struggled with their identities as artists, seeking acceptance and respectability elsewhere. Despite nearly a lifetime of success, Goldberg, for example, sought renown as an oil painter and a bronze sculptor. Fortunately, Hirschfeld had the good sense, quite early, to abandon such tomfoolery. All six Jewish cartoon artists have been fascinated not only by visual storytelling but by language: words, dialogue, slang, and gibberish. Since the outset of his career, Goldberg wavered between drawing and writing. Beyond his early work as a correspondent and a writer, Hirschfeld invented an entire language out of only his daughters name. Before creating the graphic novel, Eisner enjoyed a highly successful career as an educator. More an idea man than a technician, Kurtzman gave vision to several publications. Rising far above his origins as an underground cartoonist, Spiegelman achieved world acclaim by marrying image and text. But perhaps the most unusual and intriguing example is Steinberg, who said so little about himself in print and prevented others from tempting fate. His drawings, however, are alive with words and overflowing with puzzles, games, and riddles. Challenged and confounded by words, Jewish cartoon artists have inevitably searched for new avenues of expression. Far from being rigid

Cartoons and Jews

169

or static, cartoon art, in their minds and hands, has continually evolved to reach new audiences through various formats. Yet, cartoon artistry remains a mostly solitary and demanding endeavoralways in search of a predicament, a cause, or a revelation. Gradually, Jewish cartoon artists have grown more secure expressing their Jewishness. Granted, few religiously observant individuals have been attracted to this profession, and it is unlikely that they will be. After all, cartoonists reject dogmas, orthodoxies, and conventionsas well as a measure of common sense. But many of these artists are idealists who seek a communal response. Yet, who could have predicted that a cartoon artist would have written A Covenant with God? And who, in his right mind, would have ever imagined a cartoon exegesis of the Holocaust? Jews have consistently shown over the past century that cartoons are not only or fundamentally about laughter. They may begin or end with laughter, but something else happens along the way. Though they may never say so, cartoon artists tell us stories we would not ordinarily listen to or ever bother to read. These artists are our never-tiring, ever-forgiving teachers, therapists, judges, and rabbis, who flatter us with their lies and scold us with their truths. But they do not fear us, nor we them. Indeed, many of us have grown to love their honesty, wisdom, generosity, and kindness. How nonsensical our world would be without their profane and prophetic judgments.

PROVIDENCE, RHODE ISLAND

NOTES

1. For an example of the migration of cartoon imagery, see Garyn C. Roberts, Dick Tracy and American Culture: Morality and Mythology, Text and Context (Jefferson, NC, 1993), chapters 6 and 7. 2. For cartoons about the modern era, see Alan Dunn, Architecture Observed (New York, 1970). 3. It is a common misperception that Max Beerbohm (18721956) was a Jew. He denied it. See N. John Hall, Max Beerbohm Caricatures (New Haven, 1997), p. 1. For early Jewish cartoonists in Europe, particularly in Britain and France, see Ann Gould, Masters of Caricature: From Hogarth and Gillray to Scarfe and Levine (New York, 1981). 4. See Edward Fuchs, Die Juden in der Karikatur: Ein Beitrag zur Kulturgeschichte (Munich, 1921). Many great cartoonists, such as Rowlandson, Cruikshank, Daumier, and Beardsley, fashioned anti-Semitic imagery. 5. See Rudolph Glanz, The Jew in Early American Wit and Graphic Humor (New York, 1973) and John J. Appel, Jews in American Caricature, 1820 1914, American Jewish History, Vol. 71 (September, 1980), pp. 103133.

170

George M. Goodwin

6. For a lengthy but antiquated list, see Cartoonists, Encyclopedia Judaica, 1977 ed., Vol. V, pp. 215220. Articles on many prominent artists are found in other volumes. 7. Grace C. Grossman, Jewish Art (New York, 1995). The author focuses on liturgical and ceremonial art, but devotes a chapter to twentieth century painting and sculpture. 8. He did refer to Art Spiegelmans Maus within the context of Holocaust studies, however. See Stephen J. Whitfield, In Search of American Jewish Culture (Hanover, NH, 1999), pp. 185186. 9. American Jewish Desk Reference: The Ultimate One-Volume Reference for the Jewish Experience in America (New York, 1999). 10. One early study, Caricature (London, 1940), was by the eminent German emigre scholars, E. H. Gombrich and Ernst Kris. 11. See, for example, Eric Smoodin, Cartoon and Comic Classicism: HighArt Histories of Lowbrow Culture, American Literary History, Vol. 4 (1992), pp. 129140; and Raymond N. Norris, Behind the Jesters Mask: Canadian Editorial Cartoons about Dominant and Minority Groups, 19601979 (Toronto, 1989). A comprehensive bibliography is found in Ian Gordon, Comic Strips and Consumer Culture, 18901945 (Washington, DC, 1998). 12. Among the most impressive are David Kunzles, published by the University of California Press: The Early Comic Strip: Narrative Strips and Picture Stories in the European Broadsheet from c. 1450 to 1825 (Berkeley, 1973) and The History of the Comic Strip: The Nineteenth Century (Berkeley, 1990). 13. See, for example, Shirley Millidge, Cartoon, The Dictionary of Art, 1996 ed., Vol. V, pp. 898899. 14. Further examples of recent cartoon scholarship include Robert J. Goldstein, Censorship of Political Caricature in Nineteenth-Century France (Kent, OH, 1989) and Kirsten Powell and Elizabeth C. Childs, Femmes desprit: Women in Daumiers Caricature (Middlebury, VT, 1990). 15. Important academic institutions are The Cartoon Research Library, Ohio State University, Columbus, and The Centre for the Study of Cartoons and Caricature, Templeman Library, University of Kent, Canterbury. The International Museum of Cartoon Art, established in Greenwich, Connecticut, in 1974, built a new facility in Boca Raton, Florida, in 1996. It has a collection of 160,000 original drawings. In 1999 Melvin R. Seiden, an alumnus, gave 500 original drawings from The New Yorker to Harvards Houghton Library. Highlights were exhibited in Pusey Library. 16. Kirk Varnedoe and Adam Gopnik, High & Low: Modern Art and Popular Culture (New York, 1990). The exhibition was also shown at the Art Institute of Chicago and the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles. Its lavishly illustrated book contains numerous essays as well as an extensive bibliography. 17. See The New Yorker Book of Lawyer Cartoons and The New Yorker Book of Doctor and Psychiatrist Cartoons (both New York, 1994). 18. Herblock (born 1926) explained in his autobiography that his father, David, was only nominally Jewish. In deference to his mother, he was reared as a Catholic. As an adult, he has not identified with any religion. See Herblock: A Cartoonists Life (New York, 1993), pp. 78.

Cartoons and Jews

171

19. For biographical information, see Peter C. Marzio, Rube Goldberg: His Life and Work (New York, 1973) and Clark Kinnaird, ed., Rube Goldberg Vs. The Machine Age: A Retrospective Exhibition of His Work with Memoirs and Annotations (New York, 1968). 20. For Opper and political cartoons history, see William Murrell, A History of American Graphic Humor: 18651938 (New York, 1938); Alan Nevins and Frank Weitenkamp, A Century of Political Cartoons: Caricature in the United States from 1800 to 1900 (New York, 1944); Stephen Hess and Milton Kaplan, The Ungentlemanly Art: A History of American Political Cartoons (New York, 1968); Charles Press, The Political Cartoon (Rutherford, NJ, 1981); and Roger A. Fischer, Them Damned Cartoons: Explorations in American Political Cartoon Art (North Haven, 1996). 21. For autobiographical essays and collections of drawings, see The American Theatre as Seen by Hirschfeld (New York, 1961) and The World of Hirschfeld (New York, 1970). 22. For biographical information, see Albert Hirschfeld, Current Biography Yearbook (New York, 1971), pp. 9194. 23. An excellent study is Wendy W. Reaves, Celebrity Caricature in America (Washington, DC, 1998). An unusual though relatively minor caricaturist mentioned by Reaves was a Jewish woman, Aline Fruhauf (19071978), who specialized in portraits of musicians and dancers. In 1977 she received a retrospective exhibition at Washingtons Corcoran Gallery. Several federal repositories other than the National Portrait Gallery collect cartoon art. Most important are the Smithsonians National Museum of American History and the Library of Congress Department of Prints and Photographs. 24. See Mike Benton, Masters of Imagination: The Comic Book Artists Hall of Fame (Dallas, 1994), pp. 1727. 25. For biographical information, see Will Eisner, Current Biography Yearbook (New York, 1994), pp. 160162. 26. The publisher was Eisners own Poorhouse Press, in Tamarac, Florida, where he built a vacation home. 27. Scores of artists adept in two media are found in Kathleen G. Hjerter, Doubly Gifted: The Author as Visual Artist (New York, 1986). For a fascinating but little-known genre, see Roselyne de Ayala and Jean-Pierre Gueno, eds., Illustrated Letters: Artists and Writers Correspondence, trans. by John Goodman (New York, 1999). 28. For biographical information, see Robert C. Harvey, Harvey Kurtzman, American National Biography, 1999 ed., Vol. XIII, Nos. 12; and Benton, Master of Imagination, pp. 98106. 29. Todd Gitlin believes that the Mad mentality contributed to the political upheaval of the Vietnam era. See The Sixties: Years of Hope, Days of Rage (New York, 1987), pp. 3536. 30. See Marla Reidelbach, Completely Mad: A History of the Comic Book and Magazine (Boston, 1991). 31. See Amy K. Nyberg, Seal of Approval: The History of the Comics Code (Jackson, 1998), pp. 117124. 32. For an insightful discussion of Hefner and Playboy, see David Halber-

172

George M. Goodwin

stam, The Fifties (New York, 1993), pp. 570576. For an unflattering portrait of Hefner, see Russell Miller, Bunny: the Real Story of Playboy (New York, 1984). 33. Harvey Kurtzman, My Life as a Cartoonist (New York, 1988). 34. Whos Who in American Art (New Providence, NJ, 1997), p. 1160. 35. Burt Chernow, Saul Steinberg, Dictionary of Art, 1996 ed., Vol. XXIV, p. 605. 36. Peter Blake, Saul Steinberg: Critic Without Words, Architecture, Vol. LXXXVIII (September, 1999), p. 108. 37. Sarah Boxer, Saul Steinberg, Epic Doodler, Dies at 84, New York Times, May 13, 1999, Section I, p. 1. 38. The annual award, established in 1946, was named in honor of the Societys founding president. Goldberg won the award in 1967. 39. The Whitney retrospective traveled to the Hirshhorn Museum in Washington, DC; the Art Council of Great Britains Serpentine Gallery in London; and the Fondation Maeght in Saint-Paul, France. The exhibition catalogues lengthy essay was by Harold Rosenberg, the prominent art critic and champion of Abstract Expressionism. In 1999, when the Whitney presented its gargantuan, two-part exhibition, The American Century: Art & Culture, no example of Steinbergs work was included. There were no cartoons whatsoever. See Barbara Haskell, Art & Culture, 19001950; and Lisa Phillips, Art & Culture, 19502000 (New York, 1999). 40. The most complete reference is the Whitney catalogue, which includes a chronology and an extensive bibliography. For the artists early years, see also Saul Steinberg, Current Biography Yearbook (New York, 1957), pp. 523525. 41. Romania, which produced several prominent avant-garde artists, was the birthplace of two prominent Jewish painters: Marcel Janco (18951984) and Victor Brauner (19031966). 42. Steinberg, Whitney catalogue, p. 235. 43. Saul Steinberg, The Discovery of America (New York, 1992), p. xii. 44. An undocumented account of the artists emigration is found in Brendan Gill, Here at The New Yorker (New York, 1975), pp. 228229. A letter written in 1941 on Steinbergs behalf is reproduced in Ben Yagoda, About Town: The New Yorker and the World It Made (New York, 2000), p. 178. 45. See Thomas Kunkel, Genius in Disguise: Harold Ross of The New Yorker (New York, 1995). For Rosss impact, see Mary F. Corey, The World through a Monocle: The New Yorker at Midcentury (Cambridge, MA, 1999). 46. For a handsome and thoughtful study, see Lee Lorenz, The Art of The New Yorker: 19251995 (New York, 1995). A Steinberg drawing serves as the books frontispiece. Also, Seasons at The New Yorker (New York, 1984); and Bob Mankoff, ed., The New Yorker 75th Anniversary Cartoon Collection (New York, 1999). 47. See The New Yorker Twenty-Fifth Anniversary Album: 19251950 (New York, 1951). The magazines artists have always included Jews. Soglow (1900 1975), for instance, was responsible for many spot drawings in margins and borders. He was perhaps better known as the cartoonist of The Little King, which ran for more than forty years, beginning in 1934.

Cartoons and Jews

173

Though impressive, it is tempting to exaggerate the importance of Steinbergs earliest work. When writing his New Yorker obituary, Adam Gopnik, the magazines former art critic, did not quite explain when Steinberg became the greatest artist to be associated with this magazine, and the most original man of his time. May 13, 1999, p. 55. 48. Steig, who published his first New Yorker drawing in 1930, had some Jewish background. His paternal ancestors, from Lvov, were Hasids. But his father, who was an atheist and a socialist, provided no religious education or affiliation. See Lee Lorenz, The World of William Steig (New York, 1998), p. 14. 49. Only on rare occasions did the artist portray synagogues. Park East Synagogue, for example, is found in his 1983 drawing of 67th Street. The Star of David is flanked on neighboring buildings by American and Soviet flags. See Steinberg, The Discovery of America, p. 152. 50. The first lithographic editoral cartoon published in America, Anthony Imberts A New Map of the United States with Additional Territories, dated 1828, shows an alligator representing the West, a tortoise representing the East. See The Image of America in Caricature & Cartoon (Fort Worth, 1976), p. 63. 51. For more than a hundred reinterpretations of Disneys rodent, but not including Steinbergs, see Craig Yoe and Janet Morra-Yoe, The Art of Mickey Mouse (New York, 1991). 52. Murals were painted for the dining room of the Terrace Plaza Hotel in Cincinnati (1947) and the American pavilion at the Brussels Worlds Fair (1958). Hirschfeld had decorated the same pavilion. 53. For information about Spiegelmans career, see Current Biography Yearbook (New York, 1994), pp. 563566. 54. For a beautifully illustrated collection with an unreliable text, see Roger Sabin, Comics, Comix and Graphic Novels: A History of Comic Art (London, 1996). 55. Offshoots of the underground movement were comic books created by and for women. See Diane Noomin, ed., Twisted Sister: A Collection of Bad Girl Art (New York, 1991). Noomin and several other artists are Jews. Her comic strips include Life in the Bagel Belt with Didi Glitz and Meet Marvin Mensch. There were other comic books by and for gays and lesbians. See also Trina Robbins books, A Century of Women Cartoonists (Northampton, MA, 1993) and The Great Women Super Heroes (Northampton, MA, 1996). 56. Gary Groth, ed., The Complete Crumb, Vols. I and II (2nd ed.; Seattle, 1996). Crumbs wife, Aline Kominsky-Crumb, a cartoonist and editor of Weirdo, is probably Jewish. 57. Mark J. Estrin, A History of Underground Comics (3rd ed.; Berkeley, 1993), p. 62. 58. Some reproductions are found in Joseph Witek, Comic Book as History: The Narrative Art of Jack Jackson, Art Spiegelman, and Harvey Pekar (Jackson, 1989), pp. 96120. 59. For a guide to animal characters and strips, see Maurice Horn, ed., The Encyclopedia of Comics (Philadelphia, 1999), Index G. 60. The Image of America, p. 77. 61. Gopnik, one of the most learned and argumentative proponents of cartoon art, proclaimed Maus a masterpiece of Jewish religious art, in many

174

George M. Goodwin

ways comparable to the thirteenth century Sarajevo Haggadah. See Comics and Catastrophe, The New Republic, Vol. 196 (June 22, 1987), pp. 2934. 62. See Ken Johnson, Art Spiegelman at MOMA, Art in America, Vol. 70 (March, 1992), p. 123. 63. (New York, 1998). 64. Vittorio Giardino, A Jew in Communist Prague (New York, 1997).

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5794)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (895)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (400)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (588)