Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

3:13-cv-24068 #101

Transféré par

Equality Case FilesCopyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

3:13-cv-24068 #101

Transféré par

Equality Case FilesDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Case 3:13-cv-24068 Document 101 Filed 03/14/14 Page 1 of 40 PageID #: 3722

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF WEST VIRGINIA HUNTINGTON DIVISION

CASIE JO MCGEE and SARA ELIZABETH ADKINS; JUSTIN MURDOCK and WILLIAM GLAVARIS; and NANCY ELIZABETH MICHAEL and JANE LOUISE FENTON, Individually and as next friends of A.S.M., minor child, Plaintiffs, v. KAREN S. COLE, in her official capacity as CABELL COUNTY CLERK; and VERA J. MCCORMICK, in her official capacity as KANAWHA COUNTY CLERK, Defendants, and STATE OF WEST VIRGINIA, Defendant-Intervenor. Civil Action No. 3:13-24068

DEFENDANTS AND DEFENDANT-INTERVENORS JOINT REPLY SUPPORTING THEIR MOTIONS FOR SUMMARY JUDGMENT

Case 3:13-cv-24068 Document 101 Filed 03/14/14 Page 2 of 40 PageID #: 3723

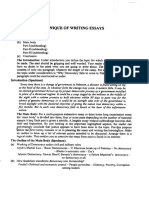

TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS................................................................................................................ ii TABLE OF AUTHORITIES ......................................................................................................... iii INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................................... 1 ARGUMENT.................................................................................................................................. 3 I. BAKER V. NELSON IS BINDING AND DISPOSITIVE.................................................... 3 A. B. II. III. IV. Baker Has Never Been Expressly Overruled.......................................................... 3 Baker Has Not Been Implicitly Overruled.............................................................. 5

WASHINGTON V. GLUCKSBERG REFUTES PLAINTIFFS CONTENTION THAT A FUNDAMENTAL RIGHT IS AT ISSUE. ...................................................................... 7 VENEY V. WYCHE REQUIRES THAT THIS COURT APPLY RATIONAL BASIS REVIEW TO PLAINTIFFS EQUAL PROTECTION CLAIM....................................... 10 THE CHALLENGED LAWS SURVIVE THE REQUIREMENTS FOR RATIONAL BASIS REVIEW SET FORTH BY THE SUPREME COURT......................................... 13 A. Plaintiffs Improperly Ignore The Supreme Courts Established Standards For Rational Basis Review. ......................................................................................... 14 1. 2. 3. 4. B. The State is not required to produce evidence. ......................................... 15 The States interest need not be actual but only conceivable. .................. 17 The State need only explain whether including a group would advance a legitimate state interest........................................................................... 18 The State is entitled to precisely formulate its interest. ............................ 20

Plaintiffs Wrongly Assert That The States Interests Are Not Conceivable Interests Or Are Not Furthered By the Challenged Laws..................................... 22 1. The traditional definition of marriage advances a conceivable state interest in expanding gay rights incrementally through successive legislation.................................................................................................. 22 The traditional definition of marriage furthers the conceivable state interest in ameliorating a unique consequence of opposite-sex intercourse................................................................................................. 26

2.

C. V.

The Exception For Statutes Motivated By A Bare Desire To Harm Is Not Applicable. ............................................................................................................ 27

THIS COURT LACKS JURISDICTION TO ENJOIN WEST VIRGINIA CODE 48-2-104(C).................................................................................................................... 29

CONCLUSION............................................................................................................................. 30

ii

Case 3:13-cv-24068 Document 101 Filed 03/14/14 Page 3 of 40 PageID #: 3724

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES CASES Agostini v. Felton, 521 U.S. 203 (1997)........................................................................................................ 2, 3, 4, 5 Allen v. Wright, 468 U.S. 737 (1984).................................................................................................................. 30 Baker v. Nelson, 409 U.S. 810 (1972)........................................................................................................... passim Barnstone v. Univ. of Houston, 446 U.S. 1318 (1980).................................................................................................................. 6 Belk v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Bd. of Educ., 269 F.3d 305 (4th Cir. 2001) ...................................................................................................... 3 Bishop v. Holder, 2014 WL 116013 (N.D. Ok. Jan. 14, 2014).............................................................. 9, 12, 18, 21 Boddie v. Connecticut, 401 U.S. 371 (1971).................................................................................................................... 8 Bostic v. Rainey, No. 2:13cv395, 2014 WL 561978 (E.D. Va. Feb. 13, 2014).................................... 1, 11, 12, 18 Bourke v. Beshear, No. 3:13-CV-750-H, 2014 WL 556729 (W.D. Ky. Feb. 12, 2014).......................... 9, 12, 15, 18 Bowen v. Owens, 476 U.S. 340 (1986).................................................................................................................. 23 Brooks v. Vassar, 462 F.3d 341 (4th Cir. 2006) ...................................................................................................... 3 Califano v. Westcott, 443 U.S. 76 (1979).................................................................................................................... 19 City of Cleburne v. Cleburne Living Ctr, Inc., 473 U.S. 432 (1985)........................................................................................................... passim Columbia Union Coll. v. Clarke, 159 F.3d 151 (4th Cir. 1998) ...................................................................................................... 3 Cutter v. Wilkinson, 544 U.S. 709 (2005).................................................................................................................. 24 De Leon v. Perry, No. SA-13-CA-00982-OLG, 2014 WL 715741 (W.D. Tex. Feb. 26, 2014)................ 12, 18, 22 Edelman v. Jordan, 415 U.S. 651 (1974).................................................................................................................... 5 Eisenstadt v. Baird, 405 U.S. 438 (1972).......................................................................................................... 8, 9, 19

iii

Case 3:13-cv-24068 Document 101 Filed 03/14/14 Page 4 of 40 PageID #: 3725

FCC v. Beach Communications, Inc., 508 U.S. 307 (1993)........................................................................................................... passim Gill v. Office of Pers. Mgmt., 699 F. Supp. 2d 374 (D. Mass. 2010) ....................................................................................... 25 Gillette v. United States, 401 U.S. 437 (1971).................................................................................................................. 24 Golinski v. U.S. Office of Pers. Mgmt., 824 F. Supp. 2d 968 (N.D. Cal. 2012) ...................................................................................... 25 Goodridge v. Dept of Pub. Health, 798 N.E.2d 941 (Mass. 2003) ................................................................................................... 23 Goulart v. Meadows, 345 F.3d 239 (4th Cir. 2003) .............................................................................................. 10, 11 Graves v. Barnes, 405 U.S. 1201 (1972).................................................................................................................. 6 Heller v. Doe, 509 U.S. 312 (1993)........................................................................................................... passim Hicks v. Miranda, 422 U.S. 332 (1975)................................................................................................................ 4, 5 High Tech Gays v. Def. Indus. Sec. Clearance Office, 895 F.2d 563 (9th Cir. 1990) .................................................................................................... 11 Hohn v. United States, 524 U.S. 236 (1998).................................................................................................................... 2 Hollingsworth v. Perry, 558 U.S. 183 (2010).................................................................................................................... 6 Johnson v. Daley, 339 F.3d 582 (7th Cir. 2003) .................................................................................................... 22 Johnson v. Robison, 415 U.S. 361 (1974)........................................................................................................... passim Kadrmas v. Dickinson Pub. Sch., 487 U.S. 450 (1988).................................................................................................................. 24 Kitchen v. Herbert, No. 2:13-217, __F. Supp. 2d__, 2013 WL 6697874 (D. Utah Dec. 20, 2013)....................................................................... 15, 18 Kitchen v. Herbert, No. 13A687, 2014 WL 30367 (Jan. 6, 2014).......................................................................... 5, 6 Lawrence v. Texas, 539 U.S. 558 (2003).................................................................................................. 8, 10, 11, 29 Lebron v. Rumsfeld, 670 F.3d 540 (4th Cir. 2012) .................................................................................................... 30

iv

Case 3:13-cv-24068 Document 101 Filed 03/14/14 Page 5 of 40 PageID #: 3726

Lee v. Orr, No. 13-CV-8719, 2014 WL 683680 (N.D. Ill. Feb. 21, 2014) ................................................. 12 Liberty Univ., Inc. v. Lew, 733 F.3d 72 (4th Cir. 2013) ...................................................................................................... 24 Little Sisters of the Poor Home for the Aged v. Sebelius, 134 S. Ct. 1022 (2014)................................................................................................................ 6 Loving v. Virginia, 388 U.S. 1 (1967)............................................................................................................... passim Lyng v. Intl Union, 485 U.S. 360 (1988)............................................................................................................ 23, 24 Mackall v. Angelone, 131 F.3d 442 (4th Cir. 1997) ...................................................................................................... 4 Mandel v. Bradley, 432 U.S. 173 (1977).................................................................................................................... 5 Massachusetts v. HHS, 682 F.3d 1 (1st Cir. 2012)......................................................................................................... 24 McDonald v. Bd. of Election Commrs of Chicago, 394 U.S. 802 (1969).................................................................................................................. 22 Michael M. v. Superior Court of Sonoma Cnty., 450 U.S. 464 (1981).................................................................................................................. 27 Muriithi v. Shuttle Exp., Inc., 712 F.3d 173 (4th Cir. 2013) ...................................................................................................... 3 Plyler v. Doe, 457 U.S. 202 (1982).................................................................................................................. 24 Rodriguez de Quijas v. Shearson/American Express, Inc., 490 U.S. 477 (1989)........................................................................................................ 2, 3, 4, 5 Romer v. Evans, 517 U.S. 620 (1996)................................................................................................ 10, 19, 27, 28 Sevcik v. Sandoval, 911 F. Supp. 2d 996 (D. Nev. 2012)................................................................................... 11, 13 SmithKline Beecham Corp. v. Abbott Laboratories, 740 F.3d 471 (9th Cir. 2014) .................................................................................................... 11 Sons of Confederate Veterans, Inc. ex rel. Griffin v. Commn of Va. Dept of Motor Vehicles, 288 F.3d 610 (4th Cir. 2002) .................................................................................................... 30 Thomasson v. Perry, 80 F.3d 915 (4th Cir. 1996) ...................................................................................................... 10 Turner v. Safley, 482 U.S. 78 (1987)...................................................................................................................... 8

Case 3:13-cv-24068 Document 101 Filed 03/14/14 Page 6 of 40 PageID #: 3727

United States Dept of Agriculture v. Moreno, 413 U.S. 528 (1973)...................................................................................................... 19, 20, 23 United States v. Cheek, 415 F.3d 349 (4th Cir. 2005) ...................................................................................................... 4 United States v. Danielczyk, 683 F.3d 611 (4th Cir. 2012) ...................................................................................................... 3 United States v. Olivera-Hernandez, 328 F. Supp. 2d 1185 (D. Utah 2004)......................................................................................... 1 United States v. Windsor, 133 S. Ct. 2675 (2013)....................................................................................................... passim Varnum v. Brien, 763 N.W.2d 862 (Iowa 2009) ................................................................................................... 23 Veney v. Wyche, 293 F.3d 726 (4th Cir. 2002) .......................................................................................... 1, 10, 11 Washington v. Glucksberg, 521 U.S. 702 (1997)........................................................................................................... passim Waste Mgmt. Holdings, Inc. v. Gilmore, 252 F.3d 316 (4th Cir. 2001) ...................................................................................................... 4 Watson v. City of Memphis, 373 U.S. 526 (1963).................................................................................................................. 16 Webster v. Reproductive Health Services, 492 U.S. 490 (1989)............................................................................................................ 29, 30 West v. Anne Arundel Cnty., Md., 137 F.3d 752 (4th Cir. 1998) ...................................................................................................... 4 Wilkins v. Gaddy, 734 F.3d 344 (4th Cir. 2013) ........................................................................................ 11, 15, 23 STATUTES W. Va. Code 48-2-104 ................................................................................................... 13, 29, 30 W. Va. Code 48-5-107 ............................................................................................................... 13 W. Va. Code 48-5-502 ............................................................................................................... 13 W. Va. Code 48-5-503 ............................................................................................................... 13 W. Va. Code 48-5-602 ............................................................................................................... 13 W. Va. Code 48-8-103 ............................................................................................................... 13 W. Va. Code 48-9-206 ............................................................................................................... 13 OTHER AUTHORITIES Bertrand Russell, Marriage & Morals (Liveright Paperbound Edition, 1970) ...................................................................................... 26

vi

Case 3:13-cv-24068 Document 101 Filed 03/14/14 Page 7 of 40 PageID #: 3728

Brief Amicus Curiae of the Becket Fund for Religious Liberty, Hollingsworth v. Perry, Nos. 12-144, 12-307, 2013 WL 439976 (U.S. Jan. 28, 2013) ..................................................................................... 16 Def. Response to Pl. Motion for Summary Judgment, Bourke v. Beshear, No. 13-750, Doc. 39 (W.D. Ky. Jan. 13, 2014) .......................................................................................................... 25 Def. Smiths Cross-Motion for Summary Judgment, Bishop v. U.S. ex rel. Holder, No. 04-CV-848-TCK-TLW, Doc. 216 (N.D. Okla. Oct. 19, 2011)........................................................................................ 22 I William Blackstone, Commentaries ........................................................................................... 26 James Q. Wilson, The Marriage Problem (2002)......................................................................... 26 Same-Sex Marriage and Religious Liberty: Emerging Conflicts (Douglas Laycock et al. eds., 2008).......................................................................................... 16

vii

Case 3:13-cv-24068 Document 101 Filed 03/14/14 Page 8 of 40 PageID #: 3729

INTRODUCTION At its core, this case invites the Court to ignore decades of never-overruled precedent including Baker v. Nelson, 409 U.S. 810 (1972), Washington v. Glucksberg, 521 U.S. 702 (1997), Veney v. Wyche, 293 F.3d 726 (4th Cir. 2002), Heller v. Doe, 509 U.S. 312 (1993), and FCC v. Beach Communications, Inc., 508 U.S. 307 (1993)and to take what Plaintiffs believe will be the Supreme Courts next logical step after United States v. Windsor, 133 S. Ct. 2675 (2013). In their most recent filing, Plaintiffs lean heavily on the avalanche of one-sided case law since Windsor as evidence of where the Supreme Courts supposedly well-trodden path is headed. Doc. 89 at 1, 5; see also id. at 13 (emphasizing what every court to have considered the issue post-Windsor has done). They urge this Court to follow the lead of recent cases like Bostic v. Rainey, No. 2:13cv395, 2014 WL 561978 (E.D. Va. Feb. 13, 2014), in which the district court pledged to use its power to grant fairness wherever it is demanded. Id. at * 23 That is, Plaintiffs implore, emphatically the responsibility of this Court. Doc. 89 at 2. But the responsibility of this Court, id., is to follow precedent unless it has been expressly overrulednot to anticipate the direction, or holding, of future Supreme Court cases. United States v. Olivera-Hernandez, 328 F. Supp. 2d 1185, 1186 (D. Utah 2004). And here, the binding precedent mandates judgment in favor of Defendants. To begin with, Baker v. Nelson is binding and dispositive of Plaintiffs claims. In the alternative, the challenged laws are valid under settled principles of constitutional law. First, under Washington v. Glucksberga case that Plaintiffs did not even bother citing in their opening briefPlaintiffs due process claim is subject to rational basis review. Second, under the Fourth Circuits decision in Veney v. Wyche, Plaintiffs equal protection claim on the basis of sexual preference is also subject to rational basis review. 293 F.3d at 732. Third, the challenged laws easily satisfy rational basis

Case 3:13-cv-24068 Document 101 Filed 03/14/14 Page 9 of 40 PageID #: 3730

review under the long-established standards set forth in Heller v. Doe and FCC v. Beach Communications. Moreover, even if this Court were to conclude that Windsor calls these precedents into question, which it does not, this Court must follow these precedents until the Supreme Court itself overrules them. The Supreme Court has said unequivocally: If a precedent of this Court has direct application in a case, yet appears to rest on reasons rejected in some other line of decisions, [lower courts] should follow the case which directly controls, leaving to this Court the prerogative of overruling its own decisions. Rodriguez de Quijas v. Shearson/American

Express, Inc., 490 U.S. 477, 484 (1989); see also Hohn v. United States, 524 U.S. 236, 25253 (1998) (Our decisions remain binding precedent until we see fit to reconsider them, regardless of whether subsequent cases have raised doubts about their continuing vitality.). Thus, although the Supreme Court in Agostini v. Felton, 521 U.S. 203 (1997), ultimately overruled an earlier decision, it praised the district court for recogniz[ing] that the motion [to vacate] had to be denied unless and until this Court reinterpreted the binding precedent. Id. at 238. That is especially true here, where the relief that Plaintiffs request will place an important and fundamental policy question outside the arena of public debate and legislative action. Glucksberg, 521 U.S. at 720. The West Virginia Legislature has, in recent years and nearly unanimously, thrice reaffirmed the traditional definition of marriage. This Court should not accept Plaintiffs invitation to interfere with that legislative judgment based solely on a prediction of where the Supreme Courts jurisprudence might be headed next.

Case 3:13-cv-24068 Document 101 Filed 03/14/14 Page 10 of 40 PageID #: 3731

ARGUMENT1 I. BAKER V. NELSON IS BINDING AND DISPOSITIVE. Because Plaintiffs cannot dispute that the precise issue presented and decided in Baker is the same issue presented here, Doc. 56 at 16, they argue instead that the decision is no longer binding because it has been []touched by subsequent doctrinal developments, Doc. 89 at 67. The argument lacks merit, as Baker has been neither explicitly nor implicitly overruled. A. Baker Has Never Been Expressly Overruled.

As Defendants have explained, Baker is still binding because it has not been expressly overruled by the Supreme Court. Doc. 68 at 21-26. In cases like Rodriguez and Agostini, the Supreme Court has made clear that its precedents remain binding unless and until they have been expressly overruled. See supra at 12. And the Fourth Circuit has closely adhered to that rule. See, e.g., Muriithi v. Shuttle Exp., Inc., 712 F.3d 173, 182 (4th Cir. 2013) (We will not readily infer that the Supreme Court impliedly has overruled its own precedent.); Brooks v. Vassar, 462 F.3d 341, 360 (4th Cir. 2006) (We have previously acknowledged the Supreme Courts instruction [in Agostini].); Belk v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Bd. of Educ., 269 F.3d 305, 411 (4th Cir. 2001) (if a precedent of the Supreme Court has direct application in a case, inferior courts must follow that precedent even if later cases appear to call it into question, leaving to the Supreme Court the prerogative of overruling its own decisions (internal quotations and alterations omitted)); Columbia Union Coll. v. Clarke, 159 F.3d 151, 158 (4th Cir. 1998) (We have consistently adhered to the Agostini directive.).2

In separate filings, see Docs. 8586, 92, the State has thoroughly addressed the question of proper defendants, see Doc. 89 at 3947. Defendant Clerks are simultaneously filing with this memorandum their response to those issues.

2

See also United States v. Danielczyk, 683 F.3d 611, 615 (4th Cir. 2012) (the Agostini principle requires lower courts to apply Supreme Court precedent that directly controls the case before it 3

Case 3:13-cv-24068 Document 101 Filed 03/14/14 Page 11 of 40 PageID #: 3732

Unable to point to any Supreme Court decision expressly overruling Baker, Plaintiffs contend that Rodriguez and Agostini do not apply to summary decisions and that Hicks v. Miranda, 422 U.S. 332 (1975), instead controls the precedential effect of such decisions. For at least two reasons, however, Plaintiffs reliance on the Hicks rule is unavailing. Doc. 89 at 6. First, the Hicks rule can and should be read consistently with Rodriguez and Agostini. Plaintiffs imply that the Hicks decision set forth a definitively different standard than Rodriguez and Agostini, but that is not true. The phrase the Supreme Court used in Hicksexcept when doctrinal developments indicate otherwiseis indisputably ambiguous. 422 U.S. at 344

(internal quotations omitted). While Plaintiffs prefer to read it broadly, it can also be read to refer only to those circumstances where there has been an express overruling. Plaintiffs offer no reason to adopt their broad reading. They cite no Supreme Court decisionbecause there is nonethat interprets the phrase any differently than the Rodriguez/Agostini standard. Nor do Plaintiffs make any argument explaining why a summary decision should be less binding on lower courts than an argued decision. To be sure, summary decisions are different in certain important respects from argued decisions. For example,

because there is no written reasoning, summary decisions are more distinguishable on their facts

despite subsequent Supreme Court case law that may have affected the precedent by implication); United States v. Cheek, 415 F.3d 349, 35253 (4th Cir. 2005) (Even were we to agree with the prognostication that it is only a matter of time before the Supreme Court overrules Almendarez-Torres, we are not free to overrule or ignore the Supreme Courts precedents.); Waste Mgmt. Holdings, Inc. v. Gilmore, 252 F.3d 316, 330 (4th Cir. 2001) (if a precedent of the Supreme Court has direct application in a case, yet appears to rest on reasons expressly rejected by a few or even a majority of the Justices in some other line of decisions, the Court of Appeals should follow the case which directly controls (internal quotation marks omitted)); West v. Anne Arundel Cnty., Md., 137 F.3d 752, 760 (4th Cir. 1998) (Lower federal courts have repeatedly been warned about the impropriety of preemptively overturning Supreme Court precedent. . . . The Supreme Courts direction has been crystal clear.); Mackall v. Angelone, 131 F.3d 442, 449 (4th Cir. 1997) (As an inferior appellate court, we are not at liberty to disregard this controlling authority.).

Case 3:13-cv-24068 Document 101 Filed 03/14/14 Page 12 of 40 PageID #: 3733

than argued decisions. Mandel v. Bradley, 432 U.S. 173, 177 (1977). The Supreme Court has also suggested that, for its purposes, a summary decision may have less stare decisis value. See Edelman v. Jordan, 415 U.S. 651, 671 (1974). But where a summary decision has reject[ed] the specific challenges raised in a subsequent caseas herethe Supreme Court has been clear that it prevent[s] lower courts from coming to opposite conclusions on th[ose] precise issues. Mandel, 432 U.S. at 176. Second, to the extent Hicks does set a different standard for summary decisions, the Rodriguez/Agostini standard is now controlling. In Hicks, the Supreme Court expressly noted that it might someday instruct otherwise. 422 U.S. at 344 (internal quotations omitted). It has done so in Rodriguez, Agostini, and a legion of other cases. B. Baker Has Not Been Implicitly Overruled.

Even if a lower court could unilaterally determine that a Supreme Court precedent has been implicitly overruledand therefore no longer binding, as Plaintiffs claimthe Supreme Courts cases do not support such a conclusion about Baker. Baker stands for the proposition that Minnesotas prohibition on same-sex marriage did not violate the Fourteenth Amendment. To overrule Baker, therefore, would be to conclude that the state law prohibition did violate the Constitution. But the Supreme Courts recent stay order in Kitchen v. Herbert makes clear that the Court has not implicitly reached that conclusion. Kitchen v. Herbert, No. 13A687, 2014 WL 30367 (Jan. 6, 2014). The Kitchen stay order is telling because, as Defendants have explained, the rigorous standards for a stay include a fair prospect of success on the merits. To obtain a stay, an applicant must show (1) a reasonable probability that four Justices will consider the issue sufficiently meritorious to grant certiorari; (2) a fair prospect that a majority of the Court will vote to reverse the judgment below; and (3) a likelihood that irreparable harm will result from 5

Case 3:13-cv-24068 Document 101 Filed 03/14/14 Page 13 of 40 PageID #: 3734

the denial of a stay. Hollingsworth v. Perry, 558 U.S. 183, 190 (2010) (per curiam). If the Supreme Court believed that Baker has been overruled, it could not have found that fair prospect of success prong satisfied and would not have granted the stay. Plaintiffs argument that the Kitchen order says nothing about the merits (and therefore nothing about Baker), Doc. 89 at 7, is wrong. The two cases that Plaintiffs citeBarnstone v. Univ. of Houston, 446 U.S. 1318 (1980), and Graves v. Barnes, 405 U.S. 1201 (1972)were denials of the requested relief, which simply means that a majority of the Justices agreed one or more of the relevant factors were not satisfied. That is why those in-chambers opinions caution against drawing any conclusion about the merits. In contrast, the grant of relief is strong evidence that a majority of the Court believes that all the relevant factors have been met. In fact, the Supreme Court has shown that it will expressly indicate otherwise if a grant of relief does not reflect as much. Two weeks after the stay grant in Kitchen, for example, the Supreme Court granted an application for an injunction in Little Sisters of the Poor Home for the Aged v. Sebelius and stated: The Court issues this order based on all the circumstances of the case, and this order should not be construed as an expression of the Courts views on the merits. 134 S. Ct. 1022 (2014). The Court made no such statement in Kitchen. Plaintiffs also contend that Windsor implicitly overruled Baker, see Doc. 89 at 78, but that argument fails upon a close examination of the Windsor decision. In support of their argument, Plaintiffs note that the Supreme Courts statement that Section 3 of DOMA violates basic due process and equal protection principles. Doc. 89 at 7. The reason why, however, is that the federal government sought to take away the status of marriage that New York had granted to same-sex couples within its borders. The State sought to give a class of persons dignity and further protection, and the federal government use[d] th[at] state-defined class

Case 3:13-cv-24068 Document 101 Filed 03/14/14 Page 14 of 40 PageID #: 3735

for the opposite purposeto impose restrictions and disabilities. Windsor, 133 S. Ct. at 2692. That is the holding of Windsor. Contrary to Plaintiffs repeated assertion in this case, the Supreme Court never once stated in Windsor that a States prohibition on same-sex marriage, which does not take away any existing rights, demeans or imposes a stigma on same-sex couples. This is not to say that Windsor shields state marriage laws from constitutional review. Doc. 89 at 4. Plaintiffs erect and attack that strawman with vigor, but that is not Defendants position. Defendants argument is that Windsor, by its own terms, is a narrow decision that neither expressly nor impliedly overrules Baker. 133 S. Ct. at 2696 (confin[ing] the opinion and its holding to the constitutionality of the federal law that refused to recognize same-sex marriages made lawful by the State). II. WASHINGTON V. GLUCKSBERG REFUTES PLAINTIFFS CONTENTION THAT A FUNDAMENTAL RIGHT IS AT ISSUE. Plaintiffs renew their assertion that they are not seeking a new fundamental right to samesex marriage, but rather seek to avail themselves of the already-recognized fundamental right to marry. Doc. 89 at 9; see id. at 10 (Plaintiffs challenge, when viewed properly, is not seeking access to a new right, but to a preexisting one: marriage.). They make no effort to suggest that a fundamental right to same-sex marriage exists and also appear to have abandoned the host of other related fundamental liberty interests referenced in their opening brief. Doc. 41 at 8. As Defendants have explained, however, the Supreme Courts decision in Washington v. Glucksberg, 521 U.S. 702 (1997)a case that Plaintiffs did not even cite in their opening brief makes clear that the fundamental right to marry includes only the right to marry a person of the opposite sex. Glucksberg teaches that fundamental rights must be objectively, deeply rooted in this Nations history and tradition and implicit in the concept of ordered liberty. 521 U.S. at 72021 (internal quotations omitted). The scope of the fundamental right to marry, therefore,

Case 3:13-cv-24068 Document 101 Filed 03/14/14 Page 15 of 40 PageID #: 3736

must accord with the historical and traditional understanding of marriage. And as the Supreme Court recently recognized, marriage between a man and woman no doubt ha[s] been thought of by most people as essential to the very definition of that term and to its role and function throughout the history of civilization. Windsor, 133 S. Ct. at 2689 (emphasis added). The Windsor Court notably did not conclude that the challenged law implicated the fundamental right to marry, but rather suggested that same-sex marriage is a new perspective [and] new insight. Id. Unable to rebut this historical understanding of marriage, Plaintiffs seek to evade it by casting doubt on Glucksberg and the relevance of history. They assert, for example, that the Supreme Court has in several cases extended the fundamental right to marry to a group of people who historically had not been permitted to exercise it. Doc. 89 at 1112 (discussing Loving v. Virginia, 388 U.S. 1 (1967) (interracial couples), Turner v. Safley, 482 U.S. 78 (1987) (incarcerated persons), and Boddie v. Connecticut, 401 U.S. 371 (1971) (divorced persons)). They also cite Eisenstadt v. Baird, 405 U.S. 438 (1972), which they claim extended the fundamental right to use contraceptives to a group that did not historically have that right. See Doc. 89 at 12.3 According to Plaintiffs, these cases show that, notwithstanding Glucksberg, history is not the end of the analysis. Doc. 89 at 10. Plaintiffs reliance on these cases is misplaced. First, the suggestion that these cases cast doubt on Glucksberg cannot be squared with the fact that they all pre-date Glucksberg and involve fundamental rights specifically highlighted in Glucksberg. The Supreme Court plainly considered Loving and Eisenstadt when it articulated the Glucksberg framework. 521 U.S. at

3

Plaintiffs also rely on Lawrence v. Texas, 539 U.S. 558 (2003), asserting that the Supreme Court held there that lesbian and gay Americans could not be excluded from the existing fundamental right to sexual intimacy. Doc. 89 at 1213. As Defendants have explained, however, Lawrence was not a fundamental-rights case. Doc. 68 at 2829.

Case 3:13-cv-24068 Document 101 Filed 03/14/14 Page 16 of 40 PageID #: 3737

720 (citing Loving and Eisenstadt). And after doing so, it could not have been clearer: Our Nations history, legal traditions, and practices thus provide the crucial guideposts for responsible decisionmaking that direct and restrain our exposition of the Due Process Clause. Id. at 721 (emphases added and citation omitted). Second, there is nothing inconsistent about what the Supreme Court did in those cases and what Defendants advocate here. The Supreme Court has found that the idea that marriage is between a man and a woman has beenthroughout the history of civilizationessential to the very definition of that term and to its role and function. Windsor, 133 S. Ct. at 2689 (emphasis added); see also id. (noting that [t]he limitation of lawful marriage to heterosexual couples has for centuries been deemed both necessary and fundamental (emphasis added)). The same cannot be said of the restrictions on marriage overturned in the cases that Plaintiffs cite, no matter how accepted or longstanding. The Supreme Court has never foundand

Plaintiffs do not contendthat the race,4 incarceration, or previous divorce of individuals seeking to be married has been similarly vital over the course of history to the meaning of marriage.5

The Supreme Courts invalidation of long-standing anti-miscegenation laws in Loving is also an inapt analogy to this case because [t]he clear and central purpose of the Fourteenth Amendment was to eliminate all official state sources of invidious discrimination in the States. 388 U.S. at 10.

5

Plaintiffs claim that every court to have considered th[is] issue post-Windsor has rejected the argument advanced by Defendants, Doc. 89 at 13, is demonstrably false. See Bourke v. Beshear, No. 3:13-CV-750-H, 2014 WL 556729, at * 5 (W.D. Ky. Feb. 12, 2014) ([N]either the Supreme Court nor the Sixth Circuit has stated that the fundamental right to marry includes a fundamental right to marry someone of the same sex.); see also Bishop v. Holder, 2014 WL 116013, at * 24 n.33 (N.D. Ok. Jan. 14, 2014) (declining to decide the question, but observing that language in Windsor indicates that same-sex marriage may be a new right, rather than one subsumed within the Courts prior right to marry cases).

Case 3:13-cv-24068 Document 101 Filed 03/14/14 Page 17 of 40 PageID #: 3738

III.

VENEY V. WYCHE REQUIRES THAT THIS COURT APPLY RATIONAL BASIS REVIEW TO PLAINTIFFS EQUAL PROTECTION CLAIM. A. Plaintiffs also continue to assert that there is no binding precedent in this Circuit for

the level of scrutiny to apply to classifications based on sexual orientation. Doc. 89 at 16. But as the State has explained, the Fourth Circuits decisions in Veney and Goulart v. Meadows, 345 F.3d 239 (4th Cir. 2003), require that this Court apply rational basis review. Doc. 68 at 31. Plaintiffs suggestion that these cases have been made obsolete by Lawrence v. Texas, Doc. 89 at 15, lacks merit. Plaintiffs argument is mainly premised on attacking Thomasson v. Perry, 80 F.3d 915 (4th Cir. 1996) (en banc), which they claim is the foundation for the Fourth Circuits application of rational basis review in Veney. Doc. 89 at 1516. But whatever might be said about Thomasson, Plaintiffs understanding of Veney is entirely incorrect. The Fourth Circuit in Veney did cite to the Thomasson decision, but only for the proposition that [t]here is no fundamental right to engage in homosexual acts generally. 293 F.3d at 731 n.4. It did not rely on Thomasson for its decision to apply rational basis review to claims based on sexual preference. Id. at 732. For that, the Veney court relied on Romer v. Evans, 517 U.S. 620 (1996), which is indisputably still good law. Id. Plaintiffs assertion that Veney be discounted as irrelevant because it occurred in the prison context, Doc. 89 at 16 n.6, is also based on a flat misreading of the case. What the Veney court said was that [o]utside the prison context, [a sexual preference claim] is subject to rational basis review. Id. (emphasis added). That Veney involved a prisoner required the court to further adjust the level of scrutiny, id., but it had nothing whatsoever to do with the courts conclusion that sexual orientation claims are ordinarily subject to rational basis review.

10

Case 3:13-cv-24068 Document 101 Filed 03/14/14 Page 18 of 40 PageID #: 3739

Veney is further bolstered by Goulart, a case that post-dates Lawrence and which Plaintiffs also unpersuasively attempt to discredit. The Fourth Circuit in Goulart listed the classifications subject to heightened scrutinyrace, national origin, alienage, sex, and illegitimacyand did not include sexual orientation. 345 F.3d at 260 (citing City of Cleburne v. Cleburne Living Ctr, Inc., 473 U.S. 432, 44041 (1985)). Plaintiffs point out that Goulart did not involve a claim of sexual orientation discrimination, Doc. 89 at 16 n.7, but it also did not involve any of the other classifications listed above. B. Because Veney is binding precedent, this Court need not (and indeed, may not) apply the factors set forth in Wilkins v. Gaddy, 734 F.3d 344 (4th Cir. 2013), to determine the appropriate level of scrutiny for a classification based on sexual orientation.6 Nevertheless, Defendants have noted that other courts that have applied those factors have determined that sexual orientation is not a quasi-suspect classification. See Doc. 68 at 32 n.8 (citing Sevcik v. Sandoval, 911 F. Supp. 2d 996, 100713 (D. Nev. 2012), and High Tech Gays v. Def. Indus. Sec. Clearance Office, 895 F.2d 563, 57374 (9th Cir. 1990)). Plaintiffs argue that Sevcik and High Tech Gays have been undermined in that respect by SmithKline Beecham Corp. v. Abbott Laboratories, 740 F.3d 471, 48384 (9th Cir. 2014), but that is not correct. SmithKline did not call into question the reasoning of those cases, but rather determined that it was required by Windsor to apply heightened scrutiny to classifications based on sexual orientation. Id. at 484.7

This Court should certainly not follow the decision of the district court in Bostic v. Rainey, No. 2:13-CV-395, 2014 WL 561978 (E.D. VA. Feb. 13, 2014), which failed entirely to address any of the relevant Fourth Circuit decisions on this issue. See Doc. 89 at 18 (urging this Court to follow the reasoning of . . . Bostic).

7

As the State has explained, SmithKline is also wrongly decided. See Doc. 68 at 3233 (explaining that Windsor applied rational basis review).

11

Case 3:13-cv-24068 Document 101 Filed 03/14/14 Page 19 of 40 PageID #: 3740

C. As in their opening brief, Plaintiffs again retreat to the assertion that the challenged laws discriminate on the basis of sex, reiterating the same arguments they made there. See Doc. 89 at 1820. These arguments are no more persuasive this second time. Doc. 68 at 3334. First, contrary to Plaintiffs bald assertion, laws like West Virginias are gender-neutral. They apply the same standard to men as to women. No man can marry a person of the same sex, nor can any woman. Unsurprisingly, of all the courts to consider this issue after Windsor, every court but one has found that a prohibition on same-sex marriage constitutes a classification based on sexual orientation (rather than sex). See De Leon v. Perry, No. SA-13-CA-00982-OLG, 2014 WL 715741, at * 1114 (W.D. Tex. Feb. 26, 2014) (finding compelling the arguments that the traditional definition of marriage discriminates . . . on the basis of . . . sexual identity); Bostic, 2014 WL 561978, at * 21 (finding that [t]he laws at issue target . . . gay and lesbian individuals); Lee v. Orr, No. 13-CV-8719, 2014 WL 683680, at * 2 (N.D. Ill. Feb. 21, 2014) (holding that the traditional definition of marriage discriminat[es] against individuals based on their sexual orientation); Bourke, 2014 WL 556729, at *45 (the provisions challenged here impose a classification based on sexual orientation); Bishop, 2014 WL 116013, at * 2425 (holding that same-sex couples are excluded from marriage regardless of their gender). Second, Plaintiffs reliance on Loving is unavailing. See Doc. 89 at 1920. The Supreme Courts rejection of the equal application principle in Loving was expressly tied to the fact that the case involved racial discrimination. See 388 U.S. at 8 (The mere fact of equal application does not mean that our analysis of these statutes should follow the approach we have taken in cases involving no racial discrimination.); id. at 9 (In the case at bar, however, we deal with statutes containing racial classifications, and the fact of equal application does not immunize the statute from the very heavy burden of justification which the Fourteenth Amendment has

12

Case 3:13-cv-24068 Document 101 Filed 03/14/14 Page 20 of 40 PageID #: 3741

traditionally required of state statutes drawn according to race.). Moreover, as the State has explained, see Doc. 68 at 3334, the law in Loving was clearly a measure[] designed to maintain White Supremacy, 388 U.S. at 11, whereas there is no indication [here] of any intent to maintain any notion of male or female superiority, Sevcik, 911 F. Supp. 2d at 1005. Third, nothing in the challenged laws remotely supports Plaintiffs suggestion that the marriage ban enforces conformity with the stereotype that men and women must perform different roles within a relationship. Doc. 89 at 19. In fact, to import such an understanding into the laws would be utterly inconsistent with other West Virginia laws that treat married men and women equally. Spouses have equal rights to be free from violence by their partners, W. Va. Code 48-2-104 (notifying couples that [t]he laws of this state affirm your right to enter into this marriage and to live within the marriage free from violence and abuse and that [n]either of you is the property of the other (emphasis added)), equal rights to seek divorce, e.g., id. 485-107, 48-5-502, 48-5-503, 48-5-602, 48-8-103, and an equal chance at obtaining child custody, id. 48-9-206.8 IV. THE CHALLENGED LAWS SURVIVE THE REQUIREMENTS RATIONAL BASIS REVIEW SET FORTH BY THE SUPREME COURT. FOR

Plaintiffs assertion that the challenged laws fail rational basis review, see Doc. 89 at 28 39, does not withstand scrutiny.9 The laws satisfy rational basis review because they further at

8

To the extent Plaintiffs now suggest that the child A.S.M.s equal protection claims are an independent basis for heightened scrutiny, see Doc. 89 at 39 n.17, they are wrong. A.S.M.s interests are entirely derivative of the denial of marriage to the adult Plaintiffs. See Doc. 68 at 34 n.10. The harms that A.S.M. alleges are not a result of the challenged laws operating on him, but rather an effect of the laws disparate treatment of the adult Plaintiffs. See Doc. 89 at 1 (A.S.M. is denied married parents, together with the legitimacy, security, and protection that children of married parents receive.).

9

Contrary to Plaintiffs assertions, Doc. 89 at 14 n.5, the States marriage laws would also survive if heightened scrutiny were the proper standard, which it is not. See Doc. 68 at 4445 n. 14. 13

Case 3:13-cv-24068 Document 101 Filed 03/14/14 Page 21 of 40 PageID #: 3742

least two conceivable interests that same-sex marriage would not further at all or to the same degree. First, the laws advance a conceivable legislative interest in expanding gay rights

incrementally through successive legislation in order to avoid the potential unforeseen or disruptive consequences of an abrupt expansion of marriage to same-sex couples. Second, they further a conceivable legislative interest in ameliorating a unique consequence of opposite-sex intercourse: unplanned children. A. Plaintiffs Improperly Ignore The Supreme Courts Established Standards For Rational Basis Review.

The chief error of Plaintiffsand the district courts that have struck down similar prohibitions on same-sex marriageis their failure to faithfully apply the Supreme Courts standards for rational basis review. As shown below, Plaintiffs and these courts have not heeded the Supreme Courts instruction that the State is not required to produce evidence, may rely on any conceivable legislative interest, need only justify the inclusion (rather than the exclusion) of a group, and is entitled to precisely formulate its interest. Plaintiffs suggest that these longsettled standards are limited to the facts of the cases in which they were articulated. See Doc. 89 at 23 (The State relies heavily on FCC v. Beach Communications, Inc., 508 U.S. 307 (1993), but that case involved a challenge to distinctions between certain types of facilities under the Cable Communications Policy Act.). But there is no basis in law for that suggestion. These cases make clear that the standards apply to all rational basis review cases. See, e.g., FCC v. Beach Commcns, Inc., 508 U.S. 307, 313 (1993) (describing rational basis review for statutes [i]n areas of social and economic policy). Plaintiffs complain that the standards are easily satisfied, see Doc. 89 at 2021, but that is precisely the point of rational basis review. When no suspect (or quasi-suspect) class or

fundamental right is affected, courts should be very reluctant to closely scrutinize legislative

14

Case 3:13-cv-24068 Document 101 Filed 03/14/14 Page 22 of 40 PageID #: 3743

choices as to whether, how, and to what extent [a States] interests should be pursued. City of Cleburne, 473 U.S. at 44142. Rational basis review embodies an idea critical to the

continuing vitality of our democracythat courts have no power to to judge the wisdom or desirability of legislative policy determinations made in areas that neither affect fundamental rights nor proceed along suspect lines. Heller v. Doe, 509 U.S. 312, 319 (1993) (citation omitted); see also Wilkins v. Gaddy, 734 F.3d 344, 348 (4th Cir. 2013). For this reason, rational basis review accord[s] laws a strong presumption of validity. Id. 1. The State is not required to produce evidence.

Under rational basis review, the State has no obligation to produce evidence to sustain the rationality of a statutory classification. Heller, 509 U.S. at 320. It may assert interests based on rational speculation unsupported by evidence or empirical data, and its interest must be upheld if there is any reasonably conceivable state of facts that could support it. Id. Unlike heightened scrutiny, rational basis review does not subject a States asserted interest to courtroom factfinding. Id. But Plaintiffs repeatedly fault the State for failing produce evidence, for engaging in speculation, or for asserting hypothetical interests. See Doc. 89 at 3 (arguing that [t]he State presents no evidence . . .); id. at 19 (Defendants do not put forth any evidence); id. at 30 (criticizing speculation about [the] financial, legal, and religious consequences of same-sex marriage); id. at 3233 (asserting that potential religious concerns are merely hypothetical and speculative). This is the same error committed by several of the district courts that have invalidated laws regarding same-sex marriage. See Bourke, 2014 WL 556729, at * 8, * 10; Kitchen v. Herbert, No. 2:13-217, __F. Supp. 2d__, 2013 WL 6697874, at * 26 (D. Utah Dec.

20, 2013) ([T]he State is not able to cite any evidence . . .).

15

Case 3:13-cv-24068 Document 101 Filed 03/14/14 Page 23 of 40 PageID #: 3744

Plaintiffs assert that the Supreme Court has consistently held that an interest in avoiding speculative and unidentified consequences . . . does not suffice for rational basis review. Doc. 89 at 30. But none of their cited cases support that principle. City of Cleburne stands for the proposition that mere negative attitudes . . . or fear are not permissible rational bases, 473 U.S. at 448; the case in no way contradicts Hellers mandate that a legislative choice . . . may be based on rational speculation, 509 U.S. at 320 (internal quotations omitted). Watson v. City of Memphis is not a rational basis review case. 373 U.S. 526, 53536 (1963) (holding that avoiding public hostility and conflict is not a compelling interest satisfying the heightened scrutiny applicable to racial segregation). In any event, with respect to the issue on which Plaintiffs primarily demand evidence, they are wrong in asserting that the State has provided none. Criticizing the State for fearmongering, Plaintiffs main complaint is that the State has made hypothetical and hyperbolic allegations of conflict between religious liberty and allowing same-sex couples to marry. Doc. 89 at 3233. But the State has directed this Court to sources showing the conflict. See Doc. 68 at 38 n.11; Same-Sex Marriage and Religious Liberty: Emerging Conflicts (Douglas Laycock et al. eds., 2008) (demonstrating the scholarly consensus that the conflict with religious liberty is real); Brief Amicus Curiae of the Becket Fund for Religious Liberty, Hollingsworth v. Perry, Nos. 12-144, 12-307, 2013 WL 439976, at * 628 (U.S. Jan. 28, 2013) (providing examples of real cases). It is irrelevant that in some cases the actual liability [may] stem[] from laws regulating commercial activity. Doc. 89 at 33. The point is that same-sex marriage can trigger burdens on the freedom of expression and religious exercise in a wide variety of areas, including by expanding the scope of commercial laws.

16

Case 3:13-cv-24068 Document 101 Filed 03/14/14 Page 24 of 40 PageID #: 3745

2.

The States interest need not be actual but only conceivable.

Plaintiffs also err in contending that the States asserted interest in in expanding gay rights incrementally through successive legislation is not supported by reality. They assert that [t]he list of enacted and proposed-but-rejected legislation the State points to in support of that proposition cannot bear the weight of its assertions. Doc. 89 at 2930; see also id. at 37 (accusing the State of advancing a post-hoc justification). Under rational basis review, it is entirely irrelevant . . . whether the conceived reason for the challenged [law] actually motivated the legislature. FCC, 508 U.S. at 315. Instead, [t]he burden is on the one attacking the legislative arrangement to negative every conceivable basis which might support it, whether or not the basis has a foundation in the record. Heller, 509 U.S. at 32021 (internal quotations and citations omitted). For this reason, it simply does not matter whether the legislative record actually reflects incremental progress. Nevertheless, Plaintiffs are wrong in asserting that West Virginias laws do not reflect a possible interest by the Legislature in incremental progress. As the State showed, West Virginia has progressively adopted laws that help same-sex couples in important ways, including in the areas of adoption, bullying, and hospital visitation.10 Doc. 68 at 40, 4748. Plaintiffs object that these are generally applicable provisions and not explicit protections based on sexual orientation, Doc. 89 at 29, but that does not diminish the fact that these laws benefit gay and lesbian individuals in new ways.

10

Contrary to Plaintiffs assertion, under these recent laws the adult Plaintiffs could visit their partner or child in the hospital. Doc. 89 at 2.

17

Case 3:13-cv-24068 Document 101 Filed 03/14/14 Page 25 of 40 PageID #: 3746

3.

The State need only explain whether including a group would advance a legitimate state interest.

Plaintiffs also repeatedly insist that the State must show a rational relationship between the States exclusion and the legitimate governmental interest, Doc. 89 at 2223, and demonstrate that any excluded groups will not suffer harm, see id. at 39 (arguing that the classification inflicts . . . injury on the child of same-sex parents); see also id. at 29 (arguing that the State must assess the impact on those excluded); id. at 35 ([T]he State fails to demonstrate how this interest is furthered . . . by excluding same-sex couples from marriage.); id. at 36 (Excluding same-sex couples from marriage has no bearing on how marriage may affect the children different-sex couples may unintentionally produce.), id. at 33 (claiming that the State must connect a blanket exclusion of same-sex couples from marriage to its interest). In support, Plaintiffs cite a number of district court decisions that have done the same. See id. at 3637; see also De Leon, 2014 WL 715741, at * 16, * 23 (requiring the State to establish how banning same-sex marriage . . . furthers the asserted state interest); Bostic, 2014 WL 561978, at * 14 (scrutinizing whether a state interest is furthered by excluding one segment); Bourke, 2014 WL 556729, at *8 (requiring the State to justify its exclusion of samesex couples); Bishop, 2014 WL 116013, at * 29 (scrutinizing the link between excluding samesex couples from marriage and the asserted state interests); Kitchen, 2013 WL 6697874, at * 24 (examining whether the States [asserted] interests . . . are furthered by prohibiting same-sex couples from marrying). But the focus under rational basis is solely on whether including or adding a group would further a legitimate interest. Doc. 68 at 4243. As the Supreme Court explained in Johnson v. Robison, a classification survives rational basis review if the inclusion of one group promotes a legitimate governmental purpose, and the addition of other groups would not. 415 U.S. 361,

18

Case 3:13-cv-24068 Document 101 Filed 03/14/14 Page 26 of 40 PageID #: 3747

382 (1974) (emphasis added). The State need only identify characteristics peculiar to [the included] group [that] rationally explain the statutes different treatment of the two groups. Id. at 378. It need not show that exclusion of any group is necessary to promote the States interests or that an excluded group will suffer no harm from the classification. See Romer v. Evans, 517 U.S. 620, 632 (1996) (holding that rational basis review upholds a law even if the law seems unwise or works to the disadvantage of a particular group); Cleburne, 473 U.S. at 440 (noting that, under rational basis review, the Constitution presumes that even improvident decisions will eventually be rectified by the democratic processes). Plaintiffs counter with several Supreme Court cases, see Doc. 89 at 23, 29, but none of them supports Plaintiffs novel understanding of rational basis review or contradicts Johnson v. Robison. Three of the casesEisenstadt, Loving, and Califano v. Westcott, 443 U.S. 76

(1979)are entirely irrelevant because they involved heightened scrutiny and not rational basis review. See Glucksberg, 521 U.S. at 720 (classifying Eisenstadt and Loving with other cases providing heightened scrutiny for fundamental rights and liberty interests); Califano, 443 U.S. at 8589 (discussing whether the challenged law meets intermediate scrutiny). As the State has explained, higher levels of scrutiny do require a more precise means-end fit. See Doc. 68 at 43. The remaining two casesCity of Cleburne and United States Department of Agriculture v. Moreno, 413 U.S. 528 (1973)are consistent with Johnson. In both cases, the Supreme Court found the challenged scheme unconstitutional because there was no characteristic that justified including one group but not another. City of Cleburne involved a zoning scheme that benefited virtually all property users but burdened the mentally retarded. 473 U.S. at 43537. The Supreme Court found that the government had no legitimate interest tied to characteristics of the benefited class that the

19

Case 3:13-cv-24068 Document 101 Filed 03/14/14 Page 27 of 40 PageID #: 3748

excluded class did not also share. See 473 U.S. at 44950 (finding that both classes faced the possibility of a flood, might not take legal responsibility for [their] actions, would concentrate the population if they build multiple-occupant homes, could cause congestion of the streets, posed fire hazards and danger to other residents, and could threaten the serenity of the neighborhood). Moreno involved a federal food stamp scheme that similarly benefited one class (households of related family members) but not another class (households of non-related individuals). 413 U.S. 528, 530 (1973). The Supreme Court found that classification

unconstitutional because all of the governments legitimate interests in the program would be furthered by providing food stamps to both classes. 413 U.S. at 53338. For example, the benefited class had no distinguishing characteristics relevant to the governments interest in feeding the hungry or stimulating agricultural production. 413 U.S. at 53334 ([t]he

relationships among persons constituting one economic unit and sharing cooking facilities have nothing to do with their abilities to stimulate the agricultural economy by purchasing farm surpluses, or with their personal nutritional requirements (citation omitted)). And to the extent that the potential for fraud was a conceivable justification for the law, neither class had a higher potential than the other. 413 U.S. at 53538. 4. The State is entitled to precisely formulate its interest.

Rational basis review requires a court to evaluate the legitimacy of the interest as asserted by the State, not the interest as reformulated by Plaintiffs or the court. Johnson v. Robison, 415 U.S. 361 (1974), is illustrative. In that case, the Court reviewed a federal program providing educational benefits to those who served during the Vietnam War. Id. at 376. A conscientious objector who had performed alternate public service to active military duty sought inclusion in the program, arguing that including him would further the programs purpose, which he defined 20

Case 3:13-cv-24068 Document 101 Filed 03/14/14 Page 28 of 40 PageID #: 3749

as eliminat[ing] the educational gaps between persons who served their country and those who did not. Id. at 36263, 37677. But as the court explained, the error in this rationale is that it states too broadly the congressional objective. Id. at 377. The government had in fact

advanced a more limited reason for the program: to compensate for the disruption that military service causes to civilian lives. Id. (emphasis added). In short, neither the plaintiffs nor a court may substitute a straw-man for the States actually asserted interest. A courts failure to examine the precise interests a State asserts is a critical and often outcome-determinative error. Defining a States interest in a law differently affectsand

sometimes removesthe rational connection between the law and the interest. In particular, restating a States interests at a higher level of generality will usually weaken the fit between the law and the interest, making the law seem far more under- or over-inclusive. Plaintiffs, however, consistently redefine the States interest as something different from what the State has asserted. While the State has asserted a specific interest in the care of unplanned children, Plaintiffs describe the interest instead as generally benefit[ing] children, promoting the welfare of our children, or prefer[ing] some children over others. Doc. 89 at 37, 38. Similarly, though the State has asserted a conceivable interest in expanding gay rights through successive legislation, Plaintiffs characterize the interest as expanding gay rights through the challenged laws themselves. Id. at 28 (arguing that [t]here is nothing about the marriage ban that expands the rights of lesbian and gay people). This error has also been made by district courts that have invalidated laws prohibiting same-sex marriage. For example, the Bishop court claimed that the articulated state goal is to reduce children born outside of a[ny] marital relationship, Bishop, 2014 WL 116013, at *29, but the State actually asserted a narrower interest in channel[ing] naturally procreative sexual

21

Case 3:13-cv-24068 Document 101 Filed 03/14/14 Page 29 of 40 PageID #: 3750

relationships into stable, enduring unions for the sake of producing and raising the next generation, Def. Smiths Cross-Motion for Summary Judgment, Bishop v. U.S. ex rel. Holder, No. 04-CV-848-TCK-TLW, Doc. 216, at * 27 (N.D. Okla. Oct. 19, 2011). See also, e.g., De Leon, 2014 WL 715741, at * 1415 (characterizing the States interest as the welfare of children when the State asserted a narrower interest in increas[ing] the likelihood that a mother and a father will be in charge of childrearing). B. Plaintiffs Wrongly Assert That The States Interests Are Not Conceivable Interests Or Are Not Furthered By the Challenged Laws.

In addition to ignoring the proper standards for rational basis review, Plaintiffs also contend that the States asserted interests are not conceivable interests or are not furthered by the challenged laws. These arguments lack merit. 1. The traditional definition of marriage advances a conceivable state interest in expanding gay rights incrementally through successive legislation.

Plaintiffs concede, as they must, that furthering an incremental approach is a legitimate basis for a law. See, e.g., FCC, 508 U.S. at 316 (holding that a legislature must be allowed leeway to approach a perceived problem incrementally); McDonald v. Bd. of Election Commrs of Chicago, 394 U.S. 802, 809 (1969) (a legislature traditionally has been allowed to take reform one step at a time, addressing itself to the phase of the problem which seems most acute to the legislative mind (citation omitted)); see also Johnson v. Daley, 339 F.3d 582, 596 (7th Cir. 2003) (The ability to take one step at a time, to alter the rules for one subset (to see what happens) without changing the rules for everyone, is one of the most important legislative powers protected by the rational-basis standard.). Instead, they challenge whether an incremental approach here is in pursuit of legitimate goals. Doc. 89 at 29. As the State has explained, the West Virginia Legislature could

22

Case 3:13-cv-24068 Document 101 Filed 03/14/14 Page 30 of 40 PageID #: 3751

reasonably have believed that there would be at least three legitimate reasons to expand gay rights incrementally: (1) to avoid unforeseen disruption to other important legislative judgments and to the public fisc; (2) to best evaluate accommodations for those who conscientiously object to endorsing or facilitating same-sex marriages; and (3) to learn from the experiences of other States that have expanded their definitions of marriage. Doc. 68 at 3739. Plaintiffs contest the legitima[cy] of all three goals. a. Plaintiffs first contend that fiscal interests cannot justify the marriage ban. Doc. 89 at 31. But contrary to Plaintiffs bald assertion, the Supreme Court has repeatedly held that [p]roblems of the fisc . . . are legitimate concerns of government. Moreno, 413 U.S. at 543; see also Lyng v. Intl Union, 485 U.S. 360, 373 (1988) (protecting the fiscal integrity of Government programs, and of the Government as a whole, is a legitimate concern of the State (citation omitted)); Wilkins, 734 F.3d at 349 (affirming that protecting the public fisc is a legitimate state interest under rational basis review). In fact, the Supreme Court has

recognized that it is legitimate for a State to have concern about the legal and fiscal effect of an all-or-nothing approach. Bowen v. Owens, 476 U.S. 340, 347 (1986). Fiscal concerns thus may justify proceed[ing] more cautiously through incremental changes in the laweven if it create[s] distinctions among categories of beneficiaries. Id. at 34748. Plaintiffs cite no cases that hold otherwise. See Doc. 89 at 31. Two of the cases are from state courts interpreting state constitutions and are therefore irrelevant to question of federal constitutional law here. See Varnum v. Brien, 763 N.W.2d 862, 878, 886, 90203 (Iowa 2009) (interpreting the Iowa Constitution); Goodridge v. Dept of Pub. Health, 798 N.E.2d 941, 964 (Mass. 2003) (interpreting the Massachusetts Constitution).

23

Case 3:13-cv-24068 Document 101 Filed 03/14/14 Page 31 of 40 PageID #: 3752

The remaining federal cases are also irrelevant, as they all involved the application of heightened scrutiny and not rational basis review. In Plyler v. Doe, the Supreme Court rejected the States asserted financial interests under a heightened level of equal protection scrutiny. 457 U.S. 202, 227 (1982); Kadrmas v. Dickinson Pub. Sch., 487 U.S. 450, 459 (1988) (confirming the heightened level of scrutiny in Plyler). Similarly, in Massachusetts v. HHS, the First Circuit applied heightened scrutiny when it rejected a concern about government resources. 682 F.3d 1, 911 (1st Cir. 2012) (citing Plyler and describing its analysis as not classic rational basis review).11 b. Plaintiffs next challenge the legitimacy of the States interest in evaluating

accommodations for those who conscientiously object to endorsing or facilitating same-sex marriages. See Doc. 89 at 32. But contrary to Plaintiffs assertions, accommodating religious exercise does not impermissibly give legal effect to the religious objections of private individuals. Id. The Supreme Court has said that it is hardly impermissible for [the

government] to attempt to accommodate free exercise values, in line with our happy tradition of avoiding unnecessary clashes with the dictates of conscience. Gillette v. United States, 401 U.S. 437, 453 (1971) (internal quotations omitted); see also Liberty Univ., Inc. v. Lew, 733 F.3d 72, 102 (4th Cir. 2013), cert. denied, 134 S. Ct. 683 (U.S. 2013) (recognizing the Governments legitimate interest in accommodating religious practice under Fourteenth Amendment rational basis review). [L]egislative accommodation of religion is a permissible secular purpose

especially where it alleviates exceptional government-created burdens on private religious exercise. Cutter v. Wilkinson, 544 U.S. 709, 713, 720 (2005).

11

Plaintiffs also cite to Lyng, see Doc. 89 at 31, but the language they quote comes from the dissenting opinion.

24

Case 3:13-cv-24068 Document 101 Filed 03/14/14 Page 32 of 40 PageID #: 3753

c. Finally, Plaintiffs contest the legitimacy of the States interest in learning from the experiences of other States that have expanded their definitions of marriage. They characterize this as an appeal[] to tradition and contend that a justification of upholding the status quo is not a legitimate government interest. Doc. 89 at 34, 35. Plaintiffs, however, completely mischaracterize the States argument. They cite

numerous cases that reject tradition alone as a legitimate state interest, but that is not the States position. The State has argued that the Legislature could conceivably have sought to proceed incrementally in order to observe the consequences of practices in other States. See Doc. 68 at 3739. This is a far cry from the naked interests in defending tradition that other courts have rejected. See Def. Response to Pl. Motion for Summary Judgment, Bourke v. Beshear, No. 13-750, Doc. 39 at * 5 (W.D. Ky. Jan. 13, 2014) (arguing that Kentuckys marriage laws pass the rational basis test simply because preserving the institution of traditional marriage is Kentuckys public policy). Nor has the State merely argued that it has an interest in preserving the status quo indefinitely or in avoiding a socially divisive issue. See Gill v. Office of Pers. Mgmt., 699 F. Supp. 2d 374, 393 (D. Mass. 2010) (This court seriously questions whether it may even consider preservation of the status quo to be an interest.); Golinski v. U.S. Office of Pers. Mgmt., 824 F. Supp. 2d 968, 1001 (N.D. Cal. 2012) (find[ing] that Congressional caution in the area of social divisiveness does not constitute a rational basis). What the State has said is that [o]ther States experiments could provide valuable practical data about the effects of same-sex marriage, which in the fullness of time could allow the Legislature to decide how best to implement same-sex marriage. Doc. 68 at 39. To that, Plaintiffs have no answer.

25

Case 3:13-cv-24068 Document 101 Filed 03/14/14 Page 33 of 40 PageID #: 3754

2.

The traditional definition of marriage furthers the conceivable state interest in ameliorating a unique consequence of opposite-sex intercourse.

As to the States other asserted interest, Plaintiffs do not dispute that the general principle that the traditional definition of marriage promotes the care of unanticipated children. They admit that the ability to accidentally procreate is a ground of difference between same-sex couples and different-sex couples. Doc. 89 at 37. And they do not contest that marriage generally encourages opposite-sex couples to care for unintentionally conceived offspring. Nor could they, as scholars have consistently reaffirmed that a reason for marriage is to promote the care of children conceived through sex. In the 1700s, William Blackstone wrote that the principal end and design of marriage is linked directly to the great relation[] of parent and child, and it is by virtue of this relation that infants are protected, maintained, and educated. 1 William Blackstone, Commentaries * 410. In the 1970s, Betrand Russell wrote: But for children, there would be no need of any institution concerned with sex. Bertrand Russell, Marriage & Morals 77 (Liveright Paperbound Edition, 1970). And little more than a decade ago, James Q. Wilson described marriage as a socially arranged solution for the problem of getting people to stay together and care for children that the mere desire for children, and the sex that makes children possible, does not solve. James Q. Wilson, The Marriage Problem 41 (2002). Instead, Plaintiffs argue that in this case, West Virginia law somehow weakens the link between marriage and the care of unintentionally conceived children. See Doc. 89 at 3538. Noting the provisions of West Virginia law concerning court-ordered child support and custodysharing, Plaintiffs appear to suggest that marriage provides no additional benefit to unplanned children. See id. at 35 (West Virginia law ensures that children are able to look to both of the people who brought them into the world for support regardless of whether those parents were 26

Case 3:13-cv-24068 Document 101 Filed 03/14/14 Page 34 of 40 PageID #: 3755

married.); see also id. at 37 (asserting that procreation and marriage are wholly separate matters under West Virginia law). But this argument has matters exactly backwards. These laws do not replace marriage; they are a backstop to marriage. They are the States attempt to replicate the benefits that marriage naturally provides to a child, in the event that the childs parents are not or cease to be married. Contrary to Plaintiffs assertion, the very existence of these laws is proof that marriage provides intrinsic benefits to unplanned children. Indeed, Plaintiffs argument is belied by their own contention that marriage provides certain unique benefits and protections to children. See Doc. 89 at 1 (A.S.M. is denied married parents, together with the legitimacy, security, and protection that children of married parents receive. All Plaintiffs are also denied vital benefits and protections under state and federal law, from access to state laws securing parent-child relationships to federal benefits such as Social Security and family medical leave.). C. The Exception For Statutes Motivated By A Bare Desire To Harm Is Not Applicable.

As the State has explained, certain Supreme Court cases suggest that laws motivated by a bare desire to harm fail rational basis review regardless of any other legitimate interest. See Doc. 68 at 35, 4546.12 Ordinarily, a law survives rational basis review even when motivated by an illegitimate purpose (such as morality)so long as the illegitimate purpose is not the only basis for the law. See id. at 44; see also Michael M. v. Superior Court of Sonoma Cnty., 450 U.S. 464, 472 n.7 (1981). In Windsor and Romer, however, the Supreme Court appears to have carved out an exception to that rule: where the illegitimate purpose is a bare desire to harm, the

12

Plaintiffs assertion that Defendants have ignore[d] this line of cases, Doc. 89 at 22, is thus provably false. 27

Case 3:13-cv-24068 Document 101 Filed 03/14/14 Page 35 of 40 PageID #: 3756

challenged law fails rational basis review regardless of any other legitimate interest. See Doc. 68 at 4546. This is ultimately the core of Plaintiffs arguments: that the sole purpose and effect of the marriage ban is to harm same-sex couples and make them unequal, Doc. 89 at 29; see also id. at 22, 2425, 2930, 39. But they are wrong. Plaintiffs argue that the Windsor/Romer exception triggers if it can be show[n] that the law was motivated by an improper motive, such as moral disapproval. Id. at 25. And here, they allege, [c]ontemporaneous statements by members of the legislature illustrate that moral disapproval. Id. at 26. This argument fails for at least two reasons. First, Plaintiffs misunderstand the Windsor/Romer exception. At issue is not what the record shows, but rather whether the challenged law on its face specifically targets and takes away existing rights. See Doc. 68 at 4546; see also id. at 24. Plaintiffs have no answer to this, nor do they contend that the challenged West Virginia laws target and take away existing rights. Second, even if a bare desire to harm could be found outside the limited context of a statute that takes away existing rights, the evidence that Plaintiffs identify is hardly sufficient to establish that the challenged laws were motivated by pure animus. To begin with, none of the statements cited by Plaintiffs are in the official legislative record. Cf. Johnson, 415 U.S. at 383 n.18 (rejecting as wholly lacking in merit a claim that a law reflects a bare . . . desire to harm a politically unpopular group when there was not a single reference in the legislative history of the Act to support [the] claim) (emphasis added). Furthermore, by their own admission, Plaintiffs evidence shows only moral disapproval. Doc. 89 at 25. But as the State has explained, morality is not the same as the raw malice, negative attitudes, fear, irrational prejudice, or some instinctive mechanism to

28

Case 3:13-cv-24068 Document 101 Filed 03/14/14 Page 36 of 40 PageID #: 3757

guard against people who appear to be different that constitutes animus. Doc. 68 at 47 (quoting City of Cleburne, 473 U.S. at 448, 450). The Supreme Court in Lawrence held that traditional sexual morality is not a rational basis, but it did not equate morality with animus. 539 U.S. at 577; see also id. at 582 (OConnor, J., concurring) (discussing [m]oral disapproval as a separate concept from bare desire to harm). Finally, Plaintiffs evidence fails even to meet their own standard. They do not identify [c]ontemporaneous statements by members of the legislature, but rather just one statement by one legislator more than a year before the challenged laws were first enacted in 2000. Doc. 89 at 26 (quoting Delegate Steve Harrisons statement in February 1999 to the press that [h]omosexuality is an immoral and unhealthy lifestyle). The remaining (sparse) evidence consists of three short press statements by Governor Underwood in 2000 and the opinion of the chairman of the West Virginian Gay and Lesbian Coalition. Id. at 27. Plaintiffs cite nothing contemporaneous to the 2001 or 2012 enactments. V. THIS COURT LACKS JURISDICTION TO ENJOIN WEST VIRGINIA CODE 48-2-104(C). Finally, even if the Fourteenth Amendment requires the State to permit same-sex marriage, this Court cannot enjoin the Legislatures non-operative statement in West Virginia Code 48-2-104(c) about what marriage is. Courts lack jurisdiction to pass on the