Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Epic and Allegory

Transféré par

jurbina1844Description originale:

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Epic and Allegory

Transféré par

jurbina1844Droits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Epic and Allegory in "Paradise Lost", Book II Author(s): James S. Baumlin Source: College Literature, Vol. 14, No.

2 (Spring, 1987), pp. 167-177 Published by: College Literature Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/25111735 . Accessed: 03/03/2014 16:46

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

College Literature is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to College Literature.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 200.75.19.130 on Mon, 3 Mar 2014 16:46:58 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

EPIC AND PARADISE

IN ALLEGORY LOST, BOOK II

by James S. Baumlin

Paradise classical

Lost, though conforming broadly to the style and structure of poem of mixed genre, a complex epic, is a typically Renaissance of pastoral and georgic, interlayering comedy and tragedy, allegory and to mention the many in this epic, the satire, not lyric moments and sonnets.1 Paradise Lost epithalamion, hymns, prayers, complaints, one that criticizes as well, is a revisionary and redefines the poem heroism of pagan epic, asserting in its place the true Christian heroism of selflessness, and obedience. The mixing of genre is indeed sufferance, a means which achieves Milton this revision of classical by epic; the of heroism classical deflates when countered military epic by the alternative values and world-views. Mean genres, with their alternative in Lost to Paradise is we thus understand Satan must ing genre-bound: consider how this fallen

the "old heroism," the proud angel embodies of and how this heroism is and heroism, pagan epic, military qualified devalued by other generic modes: as Satan's for by role, example, tragic or as the allegorical of Pride. must We villain, personification understand Adam, or genres similarly, through the major literary modes him: pastoral, georgic, and, with his fall, tragedy. the freedom of will to obey or rebel, is a central theme, choice, a major and the dialectic vehicle for developing among genres becomes it. Epic and allegory, pastoral and georgic, comedy and tragedy describe attitudes towards of genres in contrasting life; and the juxtaposition Paradise creates Lost tensions or world-views, these attitudes among tensions resolved only through a character's choice (and, as Stanley Fish Moral would have it, a reader's choice) of lifestyle. Translated into generic that define

This content downloaded from 200.75.19.130 on Mon, 3 Mar 2014 16:46:58 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

168

COLLEGE

LITERATURE

Satan falls by rejecting humble to God and his Son, "hymns" in their and the of classical choosing place proud heroism eloquence innocence and his tranquility or otium pastoral epic. Similarly, Adam's become dependent role as a georgic laborer: his duty upon his Virgilian the garden/' both the external garden of Nature and his is to "tend own internal garden, the garden of his passions, and desires. intellect, When Adam fails to keep his own inner garden, he too falls?and falls from the genres of pastoral and georgic to tragedy. terms, In Paradise moral the Lost, therefore, choice, presented through a of poetry, becomes conventions And choice among genres. essentially a heroism?is poetry of proud, military epic, surely pagan epic?the and redemption. fallen genre, one in need of redefinition Book III, with to epic of the allegorical debate between Justice and its adaptation the Son's for man. redefines heroism sacrifice great Mercy, through on must nature of pagan other the first the fallen Book hand, prove II, a it different convention of This does by adapting allegory: by epic. that upon the heroic council and by Satan's flyting with Death of the Seven Deadly Sins. A the themes and characterizations of these sins in fact unfolds when each of the seven speakers "pageant" of a particular in this book reveals his embodiment vice, one of which and actions. the dominant his words then motivates genre of Epic, is thus devalued Paradise Lost, (in Book II) and again revalued and the epic debate. Though redefined III) by means of allegorical (in Book to readers of Book of its familiar conventions II, much may be more Yet once we under has indeed been examined.2 symbolism allegorical of mixed genre, we see that neither the heroic nor stand the implications of this should stand alone in an interpretation the allegorical elements a to in is distort to them isolation that and complex, book, study even conflicts, text built on the relationships, text?a multilayered layering involves between of its differing the conventions (and values, and world-views) can the therefore be A gained by exploring genres. deeper understanding a whose dialectic between dialectic symbolism, epic and allegorical of Book II. effects can be seen most clearly in the characterizations Sins is extensive the Seven Deadly through Christian sources. of have had would any number "Parson's Tale," which typifies much of this literature, ranks order of severity, from the worst of all the deadly vices in a particular to and, Covetousness, Sloth, Wrath, Gluttony, these, Pride, Envy, as most the vices in In Lust. versions, Chaucer, develop finally, The tradition of and Milton

literature, Chaucer's

This content downloaded from 200.75.19.130 on Mon, 3 Mar 2014 16:46:58 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

EPIC AND ALLEGORY

IN PARADISE

LOST

169

each from its predecessor, progressively, retains this order among his own Milton the champion of Pride, the embodiment

from Pride. and all ultimately Satan characterizations, making to of the devils and first speak I. Beelzebub, of Envy and Satan's in Book the embodiment lieutenant, In the infernal council which begins Book II, three new speaks next. Belial embodying embodying Wrath, speakers are introduced, Moloch

At Hellgate avarice or Covetousness. Sloth, and Mammon embodying two more and Sin, characters Death, speak: representing Gluttony, more or lust The elaborate and Lechery. images trappings representing emblems and visual symbols of Lust or of the traditional pageant?the of course absent from the description and dress Envy or Gluttony?are It is what heroic devils. they say and do, predominantly to unmistakable allusion that makes however, tradition, allegorical of a particular vice. each character as the embodiment marking II Moloch In the heroic council of Book speaks first, the "Scepter'd now King . . . the strongest and fiercest Spirit / That fought in Heav'n; of Milton's Moloch's "fierce" his "frowning" nature, by despair."3 (line 105) and furious aspect, his advice to wage "open War" (line 51), to / Arm'd with Hell flames and fury all at once / To force "choose to fight with "rage" and resistless way" (lines 60-62) (line 67) against fiercer of anger or Wrath. Such VI War the in when, during symbolism furious King, who him defied, / And Gabriel Heaven, fights "Moloch at his chariot wheels to drag him bound / Threat'n'd" (lines 357-59). so indeed is the allusion to Achilles' Moloch's fury is here remarkable; of Hector's the of the Iliad body, being "the wrath of dragging subject . . . . " Moloch stern Achilles is fierceness and Wrath, is just as Achilles God's angels incarnational all mark continues in Book the Homeric deflation, Moloch's wrath, Foe" ascribes Moloch embodiment of this trait. But Moloch hero. himself the object There defined then, of the Achillean characterization. Being he projects this quality on is also a devil and a are other in ironies him as the embodiment

His entire (line 78), God. to God's character only himself embodies:

Th' Our event is feared; some should worse

argument the ire and

and controlled by of his own ire, his "fierce for all-out war therefore rage

is easy provoke may find

and

ferocity

that

Th' we way

ascent again

then;

stronger,

his wrath

To our destruction:

if there be in Hell

This content downloaded from 200.75.19.130 on Mon, 3 Mar 2014 16:46:58 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

170

COLLEGE

LITERATURE

Fear

to be worse

destroyed

. . .

What fear we then? what doubt we to incense His utmost ire? which to the highth enrag'd,

Will . . . quite consume us ... . (lines 79-96)

But more in others. (or devil) only anger on the and is Moloch's ironic, surely significant, brooding of his in the fear?a word which he three times anger, repeats opposite to above. Moloch's wrath after reduced is, fear, all, passage pain, and in Book VI when, cloven to the waist by Gabriel's cowardice sword, he / And fled "with shatter'd Arms uncouth pain (lines bellowing" hero. Indeed the 361-62). This is not a flattering picture of the Achillean is that the vice he embodies criticism of Moloch's character harshest it is not war he argues for so much as suicide. becomes self-destructive: a wrath turned inward, a desperate to escape His is ultimately attempt than to cause pain in the life of the pain of one's own existence more The of anger more

others.

man

sees

Belial

is second

to offer

advice

in the heroic

On th' other and

council:

side up rose

Belial, A For But Dropt fairer

in act more person lost

graceful not

humane; he seem'd

Heav'n; high make

dignity all was Manna,

compos*d false and and

and hollow:

exploit: though his Tongue appear the worse

could . . .

the better

reason

. . . [yet] To vice industrious, and slothful but ....

his

thoughts deeds

were

low;

to Nobler (lines

Timorous

108-17)

for a for war, Belial counsels angry advice and reasonable humble and quiet peace. His counsels are, superficially, are in the ironies characterization. Yet there again spoken. persuasively and slothful" Belial is, the narrator tells us, "Timorous (line 117), and in reason's garb" (line 226). Instead of peace, his advice but "cloth'd In contrast to Moloch's sloth" (line 227). then, Belial "Counsell[s]s ignoble ease, and peaceful ease." That he imitates of "ignoble is Sloth, is the embodiment Belial rather than into a Ciceronian himself the classical rhetoricians, making seem for a further irony. While his counsels Achillean hero, becomes in the place of hero offers mere words the public good, this Ciceronian uses words the will, to paralyze action?indeed the fallen angels alike to do nothing. The most causing men and devils can derive from Belial's

This content downloaded from 200.75.19.130 on Mon, 3 Mar 2014 16:46:58 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

EPIC AND ALLEGORY

IN PARADISE

LOST

171

an argument is to become born of his own slothfulness, argument, numb to the pain of Hell. in this developing of the deadly sins is to speak Next pageant as In I Book he is revealed Belial's advice. echoes who Mammon, and covetous: materialistic Mammon,

From Were The Than Heav'n, always riches aught

the least erected Spirit that fell

for ev'n in Heav'n bent, pavement, holy else his looks more Gold and thoughts downward of Heav'n's divine or admiring

trodd'n enjoy'd

(lines 679-84) for in Heaven alone can satisfy Mammon's Hell materialism, things cannot be piled up and prized for their own sake. Mammon's very name riches) signifies the (deriving from the New Testament Greek mammona: the vice that defines his nature. Thus his counsel vice of Covetousness, In Hell than his own greed. for peace is motivated by nothing more to his need alone he can build his golden possess temples, satisfying God's "magnificence": As he our darkness,

Imitate when we

In vision beatific,

cannot we his Light

This Desert soil

please? or

Wants

Nor

not her hidden lustre, Gems and Gold;

we skill and art, from can whence Heav'n to raise show more? (lines 269-73) what

want

Magnificence;

"Let

suggests,

us not

"but

then pursue"

rather seek

(line 249) a course

/ Our own good

of war, Mammon

from ourselves,

therefore

and from

to ourselves" (lines 252-54). The repetition of "own" that Mammon, of all the devils, shows clearly has and selfishness into the world. Yet the irony of his brought ownership character is that he cannot covets, God's truly possess what he most can and Heaven's he For he imitate. these, rather, beauty; light only the "lustre" of things, mistaking their reflected misinterprets light for the inner light emanating from each spirit still touched by God. Light imitated remains spiritual darkness. whom we have already met in Book I, is next to speak in Beelzebub, his advice is to seek "revenge" council; (line 336) against God by seducing mankind: That thir God May prove thir foe, and with repenting hand

Abolish his own works. This would surpass

our own / Live and "ourselves"

This content downloaded from 200.75.19.130 on Mon, 3 Mar 2014 16:46:58 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

172

COLLEGE

LITERATURE

Common In our

revenge, confusion,

and and

interrupt our Joy

his upraise

joy

In his disturbance,

(lines 368-73)

in another's while Beelzebub feels joy only one's misfortune, good fortune can cause him only pain. Envy motivates every aspect of his at least during the council, an embodiment of advice, and he becomes, who believes God this vice. Like Moloch, shares his wrath, Beelzebub he assumes feels "joy" projects his own envious nature on God?whom The only satisfaction of such envy, then, is in the devils' "confusion." But there is a revenge against God and the ruin of man's happiness. in Beelzebub's incarnation of this irony, if not contradiction, powerful his unbounded is his slavish, even selfless vice. Balancing envy of God to his infernal chief, Satan. For the narrator devotion suggests that his in collaboration of revenge has been made with the fallen proposition no more than a spokesman Beelzebub for Satan's Archangel, making own envy and revenge: Pleaded his devilish Counsel,

By So Of Satan, and in part proposed:

Thus Beelzebub first devis'd

for whence, the race

But from the author of all ill could Spring

deep a malice, in one all to mankind to confound . . . root

. . . done

spite

The great Creator? We are reminded

(lines 378-85)

Lost that Satan Paradise is the preemi throughout (Book V, nently envious one, that his "envy against the Son of God" But Book V also shows Satan line 662) leads to the revolt in Heaven. "So spake the false Arch-Angel, and instilling this envy into Beelzebub: into th' unwary breast / Of his Associate" (lines of envy, thus be the source may yet their close of Satanic envy and the the mouthpiece makes Beelzebub relationship in II: what Satan of bid for Book hand Satan's power op?rant to rest in the Beelzebub advises council. originally devises, infus'd / Bad influence 694-96). Satan has further allegorical Satan's and Beelzebub's relationship as as to are other the vice Envy is to Pride. close each they significance: but Satan's Pride envy and revenge are its is, after all, great vice, in the beginning of Book I: inevitable products. The narrator asserts this Of course, Who

Th'

first seduc'd them to that foul revolt?

infernal Serpent. He it was, whose guile,

This content downloaded from 200.75.19.130 on Mon, 3 Mar 2014 16:46:58 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

EPIC AND

ALLEGORY

IN PARADISE

LOST

173

Stirr'd up with Envy and Revenge, deceiv'd The Mother of Mankind; what time his Pride

Had cast him out from Heav'n .... (lines 33-37)

of Pride, and it is equally the embodiment indisputably and originates all the other vices. that he both experiences indisputable St. Bernard's Thus Milton's becomes poem dramatizes claim, which of allegorical tradition: all sins proceed itself a major proposition from Pride.4 If the vices are Satan's offspring, quite literally so are the characters as to Satan her own birth and that of her Sin and Death; Sin describes, Satan is

son's, A Out of thy and head I sprung: me Goddess seiz'd arm'd

amazement

All

At

th' host of Heav'n;

first, call'd

back they recoil'd afraid

Sin, and for a sign won full oft

Portentious

I pleas'd, The most

held me; but familiar grown,

and with attractive thee chiefly, such graces who averse,

Thyself

Becam'st With me

in me thy perfect image viewing

enamor'd, in secret, and that my joy womb thou took'st conceiv'd

A growing burden, (lines 757-767) an infernal Athena, is a warrior-goddess, Here who is the personifica on yet another tion of sin?and level of allegory is the embodiment of all too clear. The allusion to St. Lust, as her tale of seduction makes James is also clear lust hath it bringeth forth ("when conceived, sin: and sin, when it is finished, forth death"). As with the bringest one other of in her finds vice, personifications irony characterization: far from being an attractive femme fatale, this incar . . . detestable" a "sight nation of physical pleasure and desire becomes no monster than less the from down. waist (line 745), Her son, Death, is similarly complex in his allegorical significances. as an he functions the Though epic warrior, guardian of Hellgate, yet he name both his and another Death is personifies deadly vice, Gluttony. a tormented and insatiable which he himself by perpetual hunger, in Book X: describes

To Alike There mee, who is Hell, best, with eternal famine or Paradise, where most with pine, or Heav'n, ravin I may meet;

Which

here, though plenteous,

all too little seems

This content downloaded from 200.75.19.130 on Mon, 3 Mar 2014 16:46:58 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

174

COLLEGE

LITERATURE

stuff this Maw, this vast 597-601) In Book II Satan can thus win Death over be fill'd / Immeasurably, all things shall be which Death "Grinn'd horrible a ghastly

To

unhide-bound

Corpse,

(lines

him, "ye shall by promising your prey" (lines 843-45), to smile, to hear / His famine should be fill'd" Of most ironic in Death's course, (lines 846-47). of Gluttony embodiment is that he has no body to glut; his is an as he is himself "unhide-bound sheer appetite divorced from Corpse," the "lawful desires of nature." Thus Milton the moral layers upon his epic characterizations symbol ism of traditional allegory. These layers both clash with and qualify one another. The Christian a spiritual II becomes of Book allegory on classical heroism, the of the commentary poverty motive, showing

true viciousness, behind each character's brave or politic seemingly words and actions. Allegory in clear relief the otherwise hidden places their becomes spiritual underside of each devil's choice of action?which and revenge choice, once again, of genre, their choice of epic warfare than devalue pagan against God. But this layering of genres does more it allows otherwise abstract Sin, epic; personifications (Mammom, to assume concrete out and as be fully fleshed Death) epic roles?to as palpable, as the epic warriors tests "real," they join in Hell. Allegory a word, and criticizes incarnates?the epic, but epic concretizes?in abstract personifications otherwise II. This mixing of genre of Book to be a perspectivist, allows Milton in the delineation then, particularly are never "merely" thus these characters of character; personifications, nor are they ever "merely" epic figures. Each genre provides a different us to see different on the characters, aspects of allowing perspective

their complex natures.5

question incarnational a traditional obvious what is heroic

concerning symbolism element of

of is Milton's genre still remains: technique in any way an innovation in epic, or is it itself too this literary form? The answer is perhaps literary form found to define that attempts in its characters the

always the interpretive symbols of virtue and vice. The Renaissance, following and the middle traditions of late antiquity ages, inevitably read classical texts and the Renaissance of the classics, with their epic allegorically; event, and allegoresis of character, commentaries scene, and a similar blending in their own of epic and allegory the "Romance" compositions?hence epic of Tasso and Spenser. encouraged moral

in that readers of epic?the in human nature?have

elaborate poetic

This content downloaded from 200.75.19.130 on Mon, 3 Mar 2014 16:46:58 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

EPIC AND

ALLEGORY

IN PARADISE

LOST

175

We

a more subtle should not be surprised, then, to find Milton making use of moral in epic characteriza symbolism though no less pervasive a contemporary and critic of this of Milton tion. Sir William Alexander, the of Nature, above Course that the writes poet, genre, "soaring epic to Horrour Vice to the of invite and Virtue of the Beauty making Man with all his furnish the may liberally Beholders, imaginary affright of a perfect Creature."6 for the accomplishing the Qualities requisite "a gentleman Spenser also sees the chief goal of the epic as fashioning and characterization, or noble person in vertuous and gentle discipline"; the primary means with its incarnation of the virtues and vices, becomes of this moral for

Sexes ment,

instruction.7

Alexander

again of

praises

Sidney's for

prose both

Constancy,

epic, the

The Arcadia, affording

... As Discretion; still

many

for Men, and

exquisite

Magnanimity, in Women, by

Types

Modesty, a tender

Perfection

Courtesy, Shamefastness,

Carriage, sense

Valour,

Judg

Continency,

accompanied

of Honour.

And

his

chief

Persons being Eminent for some singular Virtue, united in every one of them. (187) Sidney likewise defines

and yet all Virtues

[are]

as "feigning notable epic characterization or so in and what vices, doing makes else,"8 images of virtues, in heroic of characterization the foundation incarnational symbolism once on the such symbolism reflects The poetry. again emphasis Renaissance of the classical models. poet's (and reader's) understanding is a poem not of one but of a number of Homer's Iliad, for example, a particular each of whom and clearly delineated espouses heroes, virtue?be military classical above define behavior or in political it physical prowess, wisdom strength, martial the ability to lead men, whatever. In the strategy, eloquence, in full relief are each character epics the scenes that portray all the heroic councils, formal debates over policy which tend to the

to the advice participants according they give and their it. Nestor affirms his wisdom, while giving demon Odysseus as well as cowardice, strates his guile, Thersites reveals his brashness and so on through the classical models. Milton uses of rather the heroic But council what precisely happens when to the end, classical heroism is one writes of are the characters the same

delineation devalued

character. than affirmed, when devils rather than true heroes? What "virtues" shall they embody? How answer would shall the poet point to their spiritual natures? Milton's

This content downloaded from 200.75.19.130 on Mon, 3 Mar 2014 16:46:58 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

176

COLLEGE

LITERATURE

perhaps virtue:

which all ...

sound quite

like Spenser's

own description

of Arthur

and heroic

So in the person of Prince Arthure

vertue . But ... of is the perfection the xii. other of

I sette forth magnificence

all the rest, and xii. conteineth other I make

in particular,

in knights it them and

vertues,

patrones. "So pride other

(407) to paraphrase of Satan," sets forth Spenser, "Milton which vice is the origin of all the rest, but of the six * six other knights' makes [devils] the patrons."

in the person in particular, vices, Milton

NOTES

1 Rosalie Colie's is the seminal study of mixed genre: The Resources of Kind: Genre Theory in the Renaissance. Berkeley: U California Press, 1973. Also useful in Alastair Fowler's Kinds of Literature: An Introduction to the

Theory of C. Fox Genres and Modes. Cambridge, in three Mass.: Harvard UP,

(1982):

2 Robert

180-83 et passim.

has explored Milton's allegory Lost." articles: "Satan's Triad

of Vices."

Character

Texas Studies

of Mammon

in Literature

in Paradise

and Language

Review

2 (1960): 261-80. "The

Studies, N.S. 13

of English

(1962): 30-39. "The Allegory

Language useful Book Muse's Jr., Quarterly in preparing II are Joseph Method. "Milton's 24 this H. (1963): essay. Summers,

of Sin and Death

354-64. Among "Satan, Harvard and Death: His other Sin, works

in Paradise

in of

Lost." Modern

have the allegory II of been in The

particular

explorations and UP, A Death," 1962; Comment and

Chapter Robert on

Cambridge, Allegory of

Mass.: Sin

B. White,

Backgrounds."

Modern

significant

Philology

step and of the

(1973): 337-41.

from these actions Deadly in Book

It is therefore

to II as a my subtle

a small but,

own, but which

I think, a

views the

discussions

characterizations "pageant"

carefully-orchestrated however, on

Seven

Sins?a

pageant

superimposed,

epic warriors

once again of elements

engaged

the

in "heroic council"

between that genres, is crucial

and in flyting before Hellgate.

between to explore. the epic and

It is

relationship

allegorical

characterization,

3 Paradise

Major

Lost,

Book

Ed.

II, lines 43-45.

Y. Hughes.

In John Milton,

Indianapolis:

Complete

Poems

1957:

and

233.

Prose.

Merritt

Bobbs-Merrill,

4 Though I have done little more than allude to Satan's embodiment of this vice, Fox describes in detail the pride of this fallen angel, noting that other of

the devils' vices, particularly Beelzebub's envy and Moloch's wrath, stem from

him ("Satan's Triad of Vices,"

The vices of they pride, constitute envy, the lectively,

276):

and wrath of form Satan's an infernal character; trinity: individually, col essence

This content downloaded from 200.75.19.130 on Mon, 3 Mar 2014 16:46:58 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

EPIC AND

ALLEGORY

IN PARADISE

LOST

111

they heart wrath. himself

are of

the Satan's

respective rebellion he

vices

of

Satan,

Beelzebub, and one: this from his

and pride the with to

Moloc. flow he

At envy retains

the and for and and

is his shares possession with

This the

pride exclusive he vices

pride, no with of his these

symbolically, vice. But

secondary Beelzebub form a

derivative wrath yet facet Once three with

shares

Moloc.

In Satan

associates?envy are united vices and again

complex

consistent of Satan's

character; soul Satan vices are

in Beelzebub is isolated possesses of his birth.

in Moloc in a pure all

a particular form. not these

and manifested and experiences

again, only. All

though, the

the

vices,

5 Joseph Addison (in The Spectator, January 5 to May 2, 1712) is largely in his famous criticism of Sin and Death, the criticism that these mistaken

abstractions classicism make thus, does the do does not not properly fully of Frye belong in an the epic work. of mixed decorous First of genre, in work; are all, Addison's would (and he than from in as the understand allegorical would nature which an epic

presence

as Northrop seem to not that Hell's

appreciate they function inhabitants?and

personifications term it, an encyclopedic) these that personifications as epic that just as genre the warriors?no they other thus are both

secondly, more always really, allegorical epic warriors Death from

abstractions, other their well status 6 Anacrisis, Essays of of mixed as of

different, epic Sin and and are

characterizations, of vice. Mixed "mere

characters

symbols

elevates

and abstraction." personification or a Censure Poets Ancient of Some the Seventeenth Century, 1605-1685.

and Modern Ed. J. E.

(1634). Springarn.

In Critical 3 vols.

Oxford:

7 "Letter Smith

Oxford UP,

and

1908): 1, 186.

Works Oxford UP, of Edmund 1912. Rpt. Spenser, 1959: Ed. 407. J. C.

to Raleigh." In The Poetical E. De Selincourt. London:

8 The Defense

Robert

of Poesy,

New

in Sir Philip

York: Holt,

Sidney: Selected Prose

Rinehart, 1969: 112.

and Poetry.

Ed.

Kimbrough.

This content downloaded from 200.75.19.130 on Mon, 3 Mar 2014 16:46:58 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- The Play That Goes WrongDocument39 pagesThe Play That Goes Wrongd artanjan83% (6)

- A Tolerated Margin of MessDocument41 pagesA Tolerated Margin of MessCarolina Bracco100% (1)

- Made in TokyoDocument20 pagesMade in Tokyoricardo80% (5)

- The Issue of Subjective Narration in Paradise LostDocument3 pagesThe Issue of Subjective Narration in Paradise LostLaurent Alibert100% (1)

- Conventions of The Gothic GenreDocument2 pagesConventions of The Gothic GenreGisela PontaltiPas encore d'évaluation

- Sexual Stereotypes and Tragic Violence in MacbethDocument18 pagesSexual Stereotypes and Tragic Violence in Macbethmerve sultan vuralPas encore d'évaluation

- Kiss Me With Those Red Lips: Gender Inversion DraculaDocument28 pagesKiss Me With Those Red Lips: Gender Inversion Draculametamilvy100% (1)

- Paradise LostDocument9 pagesParadise LostMoumita SinhaPas encore d'évaluation

- Paradise Lost As An EpicDocument7 pagesParadise Lost As An Epicismatnoreen100% (1)

- Paradise LostDocument14 pagesParadise LostAadPas encore d'évaluation

- Reflections of Virgil in MiltonDocument12 pagesReflections of Virgil in MiltonGraecaLatinaPas encore d'évaluation

- A Critical Estimate of MiltonDocument3 pagesA Critical Estimate of MiltonTANBIR RAHAMANPas encore d'évaluation

- McEachern - 2000 - Figures of Fidelity Believing in King LearDocument21 pagesMcEachern - 2000 - Figures of Fidelity Believing in King LearSethLesterPas encore d'évaluation

- Iliad and Paradise LostDocument6 pagesIliad and Paradise LostTanvi Diwan100% (1)

- Milton's Satanic Hero in Paradise LostDocument15 pagesMilton's Satanic Hero in Paradise LostRenê PlatelmintoPas encore d'évaluation

- Tigres en Blake y Borges PDFDocument10 pagesTigres en Blake y Borges PDFFabianaPas encore d'évaluation

- Macbeth as Tragic Hero: Understanding the Protagonist's FallDocument14 pagesMacbeth as Tragic Hero: Understanding the Protagonist's FallKasturi GuhaPas encore d'évaluation

- William Blake's "The TygerDocument2 pagesWilliam Blake's "The TygerMiruna BurnatPas encore d'évaluation

- The Battle of Good and Evil in ShakespeareDocument118 pagesThe Battle of Good and Evil in ShakespeareHorman PosterPas encore d'évaluation

- An Aspect of Tragedy: F. G. ButlerDocument22 pagesAn Aspect of Tragedy: F. G. ButlerPabitra PandaPas encore d'évaluation

- Satan's ShieldDocument18 pagesSatan's ShieldAPURBA SAHUPas encore d'évaluation

- On ProtagorasDocument12 pagesOn ProtagorasRafael ZimmermanPas encore d'évaluation

- 1 PB PDFDocument13 pages1 PB PDFGuilhermeCopati100% (1)

- Paradise Lost: AssignmentDocument8 pagesParadise Lost: Assignmentrupal aroraPas encore d'évaluation

- Milton's Satan: Exploring the Debate Over Paradise Lost's Tragic HeroDocument7 pagesMilton's Satan: Exploring the Debate Over Paradise Lost's Tragic HeroKazal BaruaPas encore d'évaluation

- Paradise Lost As An EpicDocument2 pagesParadise Lost As An EpicCHHANDAM DEBPas encore d'évaluation

- Gender Inversion and Desire in DraculaDocument28 pagesGender Inversion and Desire in DraculaRea100% (1)

- Diplomski Rad Satan As The Hero of Paradise Lost Književno-Kulturološki SmjerDocument44 pagesDiplomski Rad Satan As The Hero of Paradise Lost Književno-Kulturološki SmjerHavvaPas encore d'évaluation

- A Contradiction in Essence - Eroticism and The Creation of The SDocument36 pagesA Contradiction in Essence - Eroticism and The Creation of The SRonildo SansaoPas encore d'évaluation

- The Tragic Philosophy of The IliadDocument12 pagesThe Tragic Philosophy of The IliadAlvah GoldbookPas encore d'évaluation

- Документ Microsoft WordDocument8 pagesДокумент Microsoft WordIngaRusuPas encore d'évaluation

- Three Representations of the Fall in Lovecraft's Dream CycleDocument15 pagesThree Representations of the Fall in Lovecraft's Dream CycleScott RassbachPas encore d'évaluation

- William Blake AnalysisDocument3 pagesWilliam Blake AnalysisAngela HarrisPas encore d'évaluation

- Kuzmanovic en PDFDocument22 pagesKuzmanovic en PDFadnanPas encore d'évaluation

- Milton'S Satan: Hero or Anti-Hero?: Edith KAITER, Corina SANDIUCDocument6 pagesMilton'S Satan: Hero or Anti-Hero?: Edith KAITER, Corina SANDIUCМарија АнтићPas encore d'évaluation

- Parks PreyTellHeroes 1993Document17 pagesParks PreyTellHeroes 1993jlt.oldescheperPas encore d'évaluation

- Wolf's Justice. The Iliadic Doloneia and The Semiotics of WolvesDocument36 pagesWolf's Justice. The Iliadic Doloneia and The Semiotics of WolvesEstrimerPas encore d'évaluation

- Anaphora LacerationDocument15 pagesAnaphora LacerationAngelDPas encore d'évaluation

- This Content Downloaded From 146.50.98.29 On Sun, 03 Oct 2021 11:13:52 UTCDocument41 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 146.50.98.29 On Sun, 03 Oct 2021 11:13:52 UTCmarinaPas encore d'évaluation

- English Extension Literary WorldsDocument4 pagesEnglish Extension Literary WorldsPhoebe XuPas encore d'évaluation

- Mahabharta and The Iliad - A ComparisonDocument6 pagesMahabharta and The Iliad - A ComparisonPradeepa SerasinghePas encore d'évaluation

- The Anger of Achilles and Tarwater ComparedDocument15 pagesThe Anger of Achilles and Tarwater ComparedDiego AlonsoPas encore d'évaluation

- Snake Vs 2 Head SnakeDocument5 pagesSnake Vs 2 Head SnakefelipecalvettePas encore d'évaluation

- Marriage of Heaven and HellDocument32 pagesMarriage of Heaven and HellNikos GkizisPas encore d'évaluation

- Paradise LostDocument5 pagesParadise Lostkhushnood aliPas encore d'évaluation

- "Under The Volcano" Geoffrey Firmin's Tragic Epiphany - Jospeh A. LongoDocument12 pages"Under The Volcano" Geoffrey Firmin's Tragic Epiphany - Jospeh A. LongoMaríaPas encore d'évaluation

- Plato - The Myth of ErDocument16 pagesPlato - The Myth of ErPrashanth JanardhanPas encore d'évaluation

- Drama: Name of The Paper: Topic: Macbeth Sub-Topic: Macbeth As A Shakespearean TragedyDocument13 pagesDrama: Name of The Paper: Topic: Macbeth Sub-Topic: Macbeth As A Shakespearean TragedyMohd Anish KhanPas encore d'évaluation

- 90Document4 pages90jgjlllllllfyjfPas encore d'évaluation

- FryeDocument7 pagesFryewiweksharmaPas encore d'évaluation

- Allegory-Routledge (2017)Document78 pagesAllegory-Routledge (2017)César Andrés Paredes100% (1)

- EPICDocument2 pagesEPICAbdul Nisar JilaniPas encore d'évaluation

- Absalam and AchitophelDocument32 pagesAbsalam and AchitophelronPas encore d'évaluation

- Romantic Devil as Tragic HeroDocument12 pagesRomantic Devil as Tragic HeroCassio CarvalheiroPas encore d'évaluation

- 1992 Postexistentialism in The Neo Gothic Mode of Anne RiceDocument20 pages1992 Postexistentialism in The Neo Gothic Mode of Anne RiceGuilhermeCopatiPas encore d'évaluation

- George Washington University, Folger Shakespeare Library Shakespeare QuarterlyDocument13 pagesGeorge Washington University, Folger Shakespeare Library Shakespeare QuarterlyDom BlaquierePas encore d'évaluation

- Archetypal Symbols in William Blake's 'The LambDocument7 pagesArchetypal Symbols in William Blake's 'The LambArkan NaserPas encore d'évaluation

- Vol 2 Issue XI 234 241 Paper 39 SahabuddThe Epic Structure and Style of John Milton's Paradise Lost A Critical Study With PartDocument8 pagesVol 2 Issue XI 234 241 Paper 39 SahabuddThe Epic Structure and Style of John Milton's Paradise Lost A Critical Study With PartPabitra DasPas encore d'évaluation

- Tragedy and Its OriginsDocument6 pagesTragedy and Its OriginsemilyjaneboylePas encore d'évaluation

- The Symbolic Framework of Blake's TygerDocument3 pagesThe Symbolic Framework of Blake's TygerJason ChismPas encore d'évaluation

- Ijser: Satan, The Most Well-Developed Character of Milton's: A Critical AnalysisDocument13 pagesIjser: Satan, The Most Well-Developed Character of Milton's: A Critical AnalysisYugant DwivediPas encore d'évaluation

- Epic and Hispanic BalladDocument17 pagesEpic and Hispanic Balladjurbina1844Pas encore d'évaluation

- Chronotopes As Memory SchemataDocument16 pagesChronotopes As Memory Schematajurbina1844Pas encore d'évaluation

- Framed Narrative MedievalDocument12 pagesFramed Narrative Medievaljurbina1844Pas encore d'évaluation

- Mimesis Semiotic CommunicationDocument25 pagesMimesis Semiotic Communicationjurbina1844Pas encore d'évaluation

- Theologians of SalamancaDocument16 pagesTheologians of Salamancajurbina1844Pas encore d'évaluation

- A Chronicle Toward Novel Bernal DiazDocument17 pagesA Chronicle Toward Novel Bernal Diazjurbina1844Pas encore d'évaluation

- Achilles in GerusalemmeDocument14 pagesAchilles in Gerusalemmejurbina1844Pas encore d'évaluation

- Aspects of The Spanish Religious EpicDocument11 pagesAspects of The Spanish Religious Epicjurbina1844Pas encore d'évaluation

- Aristotle Mimesis and UnderstandingDocument13 pagesAristotle Mimesis and Understandingjurbina1844Pas encore d'évaluation

- Teun A Van Dijk - Ideology and DiscourseDocument118 pagesTeun A Van Dijk - Ideology and Discourseİrem Özden AtasoyPas encore d'évaluation

- Aspects of The Spanish Religious EpicDocument11 pagesAspects of The Spanish Religious Epicjurbina1844Pas encore d'évaluation

- Spices Spanish EmpireDocument30 pagesSpices Spanish Empirejurbina1844Pas encore d'évaluation

- A Chronicle Toward Novel Bernal DiazDocument17 pagesA Chronicle Toward Novel Bernal Diazjurbina1844Pas encore d'évaluation

- Genres in The Renaissance and AfterDocument17 pagesGenres in The Renaissance and Afterjurbina1844Pas encore d'évaluation

- Boes ModernistDocument14 pagesBoes ModernistdeeptheonlyonePas encore d'évaluation

- Bildungsroman in EnglishDocument396 pagesBildungsroman in Englishjurbina1844100% (3)

- Female Imperial GazeDocument26 pagesFemale Imperial Gazejurbina1844Pas encore d'évaluation

- Five Imperial AdventuresDocument30 pagesFive Imperial Adventuresjurbina1844Pas encore d'évaluation

- Imperial AuthorityDocument22 pagesImperial Authorityjurbina1844Pas encore d'évaluation

- Female Imperial GazeDocument26 pagesFemale Imperial Gazejurbina1844Pas encore d'évaluation

- Beyond The BildungsromanDocument23 pagesBeyond The Bildungsromanjurbina1844Pas encore d'évaluation

- Imperial Discourse in GibraltarDocument16 pagesImperial Discourse in Gibraltarjurbina1844Pas encore d'évaluation

- Rhodes University: Institute For The Study of English in Africa, Rhodes UniversityDocument12 pagesRhodes University: Institute For The Study of English in Africa, Rhodes Universityjurbina1844Pas encore d'évaluation

- Anti Imperialist LeagueDocument17 pagesAnti Imperialist Leaguejurbina1844Pas encore d'évaluation

- Critique of EmpireDocument38 pagesCritique of Empirejurbina1844Pas encore d'évaluation

- Holy LandscapeDocument32 pagesHoly Landscapejurbina1844Pas encore d'évaluation

- Spices Spanish EmpireDocument30 pagesSpices Spanish Empirejurbina1844Pas encore d'évaluation

- Iberian Colonial ScienceDocument8 pagesIberian Colonial Sciencejurbina1844Pas encore d'évaluation

- Lucan Civil War LandscapeDocument25 pagesLucan Civil War Landscapejurbina1844Pas encore d'évaluation

- 1 Point Perspective GridDocument8 pages1 Point Perspective GridRohan BhardwajPas encore d'évaluation

- Botong Francisco - An Insight Into His ArtistryDocument2 pagesBotong Francisco - An Insight Into His Artistryjironramelo112103Pas encore d'évaluation

- Le Mepris Jean-Luc Godard 1963 and Its S PDFDocument13 pagesLe Mepris Jean-Luc Godard 1963 and Its S PDFIsadora ZilioPas encore d'évaluation

- Bad Nut Shawl: by Josh RyksDocument4 pagesBad Nut Shawl: by Josh RyksRdeS100% (2)

- AJC Access Atlanta 11Document2 pagesAJC Access Atlanta 11Atlanta Celebrates PhotographyPas encore d'évaluation

- Z Adventure Glove Box Easy Out Bracket Fitting GuideDocument3 pagesZ Adventure Glove Box Easy Out Bracket Fitting GuideGiambattista GiannoccaroPas encore d'évaluation

- 2023 P&G GuidelinesDocument64 pages2023 P&G GuidelinesE Daniel BerríosPas encore d'évaluation

- 6 Elevation Day Spa-Finish Floor PlanDocument1 page6 Elevation Day Spa-Finish Floor Planapi-290046801Pas encore d'évaluation

- Audio ScriptsDocument39 pagesAudio ScriptsNadia Salsabilla TsaniPas encore d'évaluation

- KarateDocument15 pagesKarateFrank CastlePas encore d'évaluation

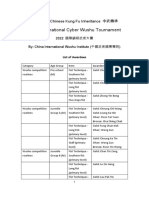

- List of Awardees - 2022 International Cyber Wushu TournamentDocument11 pagesList of Awardees - 2022 International Cyber Wushu TournamentMOUSTAFA KHEDRPas encore d'évaluation

- Red, Gold, and Green: The Colorful, Heraldic Symbolism Within Sir Gawain and The Green KnightDocument6 pagesRed, Gold, and Green: The Colorful, Heraldic Symbolism Within Sir Gawain and The Green KnightJohnPas encore d'évaluation

- UNIVERSITY BAND CONCERTDocument5 pagesUNIVERSITY BAND CONCERTboviaoPas encore d'évaluation

- Coimbatore PDFDocument12 pagesCoimbatore PDFYogesh Babu NmkPas encore d'évaluation

- The Black Death and the Rise of Gothic ArchitectureDocument9 pagesThe Black Death and the Rise of Gothic ArchitectureMooni BrokePas encore d'évaluation

- Aries Kitten: Head & BodyDocument4 pagesAries Kitten: Head & BodySelena KPas encore d'évaluation

- CubismDocument4 pagesCubismCassie CutiePas encore d'évaluation

- Augusto Ferrer-Dalmau - ArtDocument36 pagesAugusto Ferrer-Dalmau - ArtManuel NeivaPas encore d'évaluation

- Spring 2013 Interweave Retail CatalogDocument122 pagesSpring 2013 Interweave Retail CatalogInterweave100% (2)

- A Marriage Proposal - Wikipedia, The Free EncyclopediaDocument3 pagesA Marriage Proposal - Wikipedia, The Free EncyclopediaRay Rafael RamosPas encore d'évaluation

- KusamakuraDocument3 pagesKusamakuraMeggy Villanueva0% (1)

- Instrução Albany TwinDocument12 pagesInstrução Albany TwinleonPas encore d'évaluation

- Z Thesis SynopsisDocument22 pagesZ Thesis SynopsisAfsheen NaazPas encore d'évaluation

- Vinilex 5000 - 07 Mar 2017Document2 pagesVinilex 5000 - 07 Mar 2017Ajie Dwi YuniarsoPas encore d'évaluation

- Virginia Woolf in The Modern Machine Age PDFDocument44 pagesVirginia Woolf in The Modern Machine Age PDFApoorva DevPas encore d'évaluation

- Master-LK CompressedDocument33 pagesMaster-LK CompressedTú HoàngPas encore d'évaluation

- Big Bull Head (Pared) - Paper FreakDocument28 pagesBig Bull Head (Pared) - Paper FreakLuis RalonPas encore d'évaluation

- 2016 CatalogDocument692 pages2016 Catalogshawn.fannon9274Pas encore d'évaluation