Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Tools of Autocracy: Vitali Silitski

Transféré par

Armando Garcia TeixeiraTitre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Tools of Autocracy: Vitali Silitski

Transféré par

Armando Garcia TeixeiraDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Tools of Autocracy

Vitali Silitski

Journal of Democracy, Volume 20, Number 2, April 2009, pp. 42-46 (Article)

Published by The Johns Hopkins University Press

DOI: 10.1353/jod.0.0067

For additional information about this article

Access Provided by Oxford University Library Services at 12/26/11 7:05PM GMT

http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/jod/summary/v020/20.2.silitski.html

TOOLS OF AUTOCRACY

Viicli Siliis|i

Vitali Silitski is director oj the Belarusian /nstitute jor Strategic Stud-

ies. He has been a visiting jellow at the Center on Democracy, Devel-

opment, and the Rule oj Law at Stanjord University (2006-2007), and

a Reagan-Fascell Democracy Fellow at the National Endowment jor

Democracy (2004-2005).

Controversy may continue to rage about how and why the Russian po-

litical system has reached its current state, but it is not hard to say what

that state is. Much of the confusion about the proper definition to at-

tach to Russia`s regime and those resembling it arises from a lingering

tendency to see otherwise-authoritarian systems that offer a degree of

multiparty electoral competition as diminished forms of democracy.

Arguably a flawed democracy in the 1990s, Russia took a distinctly

authoritarian turn under President Vladimir Putin from 2000 to 2008.

The country now lives under a faade democracy that barely conceals

the political and administrative dominance of a self-interested bureau-

cratic corporation. This corporation is not immune to factional squab-

bles and internal games over power and wealth, but its basic instinct for

self-preservation has been enough to keep it relatively unified.

The current regime fits the classic definition of authoritarianism,

which places more emphasis on what the system lacks than on what it

has. Thus Russia today displays all the facets of 'limited . . . political

pluralism,

1

including a system of formal multiparty electoral competi-

tion that for most of the last decade has been deprived of unpredictabil-

ity. Incumbents have no reason to sweat on election night, even if they

must work hard between elections in order to make sure that no serious

challengers can emerge. Hence, Russia`s authoritarianism can no longer

be regarded as competitive.

2

Russia`s autocracy is also typical to the extent that it does not rely

upon an 'elaborate and guiding ideology, but is heavily grounded in

'distinctive mentalities,

3

meaning a specific political culture that justi-

1ournal oj Democracy \olume 20, Number 2 April 2009

2009 National Endowment jor Democracy and The 1ohns Hopkins University Press

ReadIng RussIa

43 \itali Silitski

fies strong centralized authority through the use of extensive references

to history, faith, and identity. Likewise, it does not rely upon broad or

intense political mobilization, except in selected instances, as when the

Kremlin recruited youth groups such as Nashi for a time as part of a

strategy to prevent any Russian replay of Ukraine`s 2004 Orange Revo-

lution. (Authorities easily demobilized Nashi later.)

As is the case with most other contemporary autocratic regimes,

Russia`s rulers claim that their country is a democracy. In dealing with

opponents, today`s autocracies tend to avoid wholesale force and open

repression, preferring instead to rule via manufactured consent. The

manufacture of consent involves three major tools. The first is 'politi-

cal technology, which is shorthand for information and propaganda

campaigns aimed at discrediting and destroying opponents before they

even enter the political contest. The Russian elite truly pioneered the

application of political technology, and worked to spread it widely in

the post-Soviet arena. In the minds of those who run the Kremlin, this is

nothing to be ashamed of: They simply cannot imagine a political sys-

tem working differently. In their view, the spontaneity that one seems to

observe in Western democracies is a product of the same elite consensus

and fixing, through which outsiders are marginalized. Western rhetoric

about democracy and the rule of law is spurned as a cynical attempt to

open up political space for outsiders who enjoy foreign backing.

The second tool is a more concrete form of preemption.

4

Like regimes

elsewhere in the post-Soviet space such as those of Azerbaijan, Belarus,

and Kazakhstan, the Russian regime routinely attacks potential oppo-

nents with more than just rhetoric and propaganda. In the mid-2000s,

with a strong economy and the approval ratings to go with it, the Kremlin

began implementing measures not only to discredit and demoralize the

opposition with hostile propaganda, but also to strip it of anything like a

level playing field and, when necessary, to remove it physically from the

scene. This last goal may be pursued by simply disqualifying opposition

figures from running for office, but also by jailing them, forcing them

into exile, or even, in extreme cases, murdering them. Quick to shut

down opponents in politics as well as in business and the bureaucracy,

Putin`s Kremlin also freely twists election rules and party legislation so

that no one of whom it does not approve can even enter the contest for

power. Today, the Kremlin enjoys a free hand to appoint both the ruling

party and the opposition.

The third tool is-or was-the steady flow of material benefits for

citizens, which the regime financed with once-abundant petrodollars.

To complement this, the regime also allowed individuals a wide zone of

social autonomy in which state officials did not interfere.

While the authoritarian nature of Russia`s regime is beyond question,

it is somewhat more difficult to define precisely what kind of authori-

tarianism it is. On the one hand, nearly unlimited presidential authority,

44 1ournal oj Democracy

embedded in formal rules and supported by myriad informal practices,

points to the personalistic nature of the Kremlin`s rule. On the other,

Russia is definitely not a primitive sultanistic dictatorship governed by

rulers` whims and court intrigues. The government in Russia manages a

unique and diverse country though a vast and complex bureaucracy, and

regime stability depends upon the rulers`

ability to incorporate and make strategic

deals with a multitude of powerful sub-

jects.

History shows, however, that person-

alistic rule, as the name suggests, relies

in the end upon the personality and re-

solve of the ruler. Putin`s personality

had a definitive impact on the new class

of beneficiaries and powerful subjects

that emerged in the 2000s, largely rep-

resenting the law-enforcement agencies.

At the same time, the real constraints on the president`s absolute power

came not from internal factors (powerful political competitors or strong

democratic institutions), but rather from considerations of Russia`s in-

ternational prestige. As long as the pursuit of Russian greatness required

formal acceptance by the 'gentlemen`s club of democratic powers, the

Kremlin`s ruler could not be seen as stooping to the level of a crude

autocrat.

Accordingly, when Putin reached the end of his second consecutive

term in the presidency, rather than stay on (which would have required

altering the constitution), he observed the niceties of presidential succes-

sion and became prime minister instead. With this shift, the system came

to resemble the Soviet-era collective leadership, in which a nominal head

of state cohabited with a supreme party leader and premier. The combina-

tion of a formally powerful presidency (albeit one now filled by a figure-

head) with a prime minister who is the de facto ruler and maintains a huge

clientele in the state bureaucracy, the ruling party, and parliament must be

considered a token of unconsolidated authoritarianism-and the potential

for instability is inherent in this gap between formal and informal rules.

Of all the things that could expose this gap and fuel splits within the

elite, the question of presidential succession is the foremost. In order to

bolster regime stability as much as possible, Putin moved while presi-

dent to block any channel through which political protest could lead to a

change of government. Further efforts at such 'institutional tightening

may still come, perhaps in the form of extended terms of office for both

the president and parliament. The rise of a strong civic force demanding

democratic reform remains a possibility, but a very distant one. This is

due to both strategic factors (the regime`s repertoire of fine-tuned pre-

emption techniques) and structural ones: Even in the more liberal days

The very conditions

that make for authori-

tarian stability in good

times might make

protests less predictable

and harder to control

when things go bad.

45 \itali Silitski

of Yeltsin, there was hardly a nationwide civil society capable of setting

the political agenda for the entire country, and no genuinely nationwide

party aside from the Communists.

Although Russia`s system is well barricaded, might it still be vulner-

able to spontaneous protests from below-the kind that can flare up

once citizens begin to understand that the provider-state will not be able

to maintain its implicit contract with them? The very conditions that

make for authoritarian stability in good times might make such pro-

tests less predictable and harder to control when things go bad. Such

conditions include the marginalization of large parts of society, social

polarization, widespread disengagement from public life, and the preva-

lence of 'low-intensity citizenship. The authorities` panicky reaction to

pensioners` protests following the clumsy abolition of social benefits in

January 2005 highlighted the extent to which a deficit of feedback from

'real society (as opposed to handpicked 'representative bodies) had

opened up on Putin`s watch. Although the regime may take comfort in

reflecting that there is no framework of institutions or unifying ideology

to give shape and direction to the public`s more protest-prone moods,

the possibility of 'contagion effects leading to nationwide upheavals

cannot be ruled out.

If out-of-system protests do spring up, the institution of alternation

in power may turn into a source of real problems for the status quo. At

some point, the figurehead president, unwilling to take all the blame

for the country`s woes, could start using his sweeping decree powers.

If President Dmitri Medvedev ever felt pushed to take such a course, it

could deal a fatal blow to Putin`s 'parallel presidency and pave the way

for a major elite reshuffling and a new round of struggle over spoils.

The absence of ideology as a driving factor in Russian foreign (and

domestic) policy means that the Kremlin will have no rationale for engag-

ing in a full-scale confrontation with the West. Yet two aspects of Rus-

sia`s political regime will continue to affect the country`s foreign policy.

The first is the regime`s deep-seated suspicion of the value-based agenda

of the West toward Russia and its 'near abroad. This distrust will lead

the Kremlin to carry on with its attempts to drive U.S. and EU political

and economic influence out of the post-Soviet space, even if such efforts

harm Russia`s own economic interests. The regime is prepared to tolerate

such financial losses, for it sees Western influence in the Russian 'near

abroad as a threat to the status quo within Russia itself. Moreover, the

current regime`s inability to propose a credible long-term development

strategy beyond reinvesting energy-export profits will drive the Krem-

lin to use its foreign policy to keep the 'oil paradigm going. Russia, in

other words, will be keenly interested in anything that keeps energy prices

from falling, with ominous implications regarding Moscow`s behavior in

such sensitive regions as Central Asia, the western portions of the former

USSR, Iran, and the rest of the Middle East.

46 1ournal oj Democracy

NOTES

1. Juan J. Linz, 'An Authoritarian Regime: The Case of Spain, in Erik Allardt and

Stein Rokkan, eds., Mass Politics: Studies in Political Sociology (New York: Free Press,

1970), 255.

2. Steven Levitsky and Lucan Way define competitive authoritarian regimes as ones

which, while falling short of democracy, 'also fall short of full-scale authoritarianism. Al-

though incumbents in competitive authoritarian regimes may routinely manipulate formal

democratic rules, they are unable to eliminate them or reduce them to a mere faade. . . .

As a result, even though democratic institutions may be badly flawed, both authoritarian

incumbents and their opponents must take them seriously. Steven Levitsky and Lucan

A. Way, 'The Rise of Competitive Authoritarianism, 1ournal oj Democracy 13 (April

2002): 53-54.

3. Linz, 'An Authoritarian Regime, 255.

4. See Vitali Silitski, 'Contagion Deterred: Preemptive Authoritarianism in the Former

Soviet Union (The Case of Belarus), CDDRL Working Paper No. 66, June 2006. Avail-

able at http://iis-db.stanjord.edu/pubs/21152/Silitski_No_66.pdj.

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- Russia'S Political Regime and Its Future Perspectives: Živilė ŠatūnienėDocument40 pagesRussia'S Political Regime and Its Future Perspectives: Živilė ŠatūnienėCristina Anda ChircaPas encore d'évaluation

- Sovereigh Democracy Ideology of ERDocument15 pagesSovereigh Democracy Ideology of ERАнтон КурилкинPas encore d'évaluation

- Ilya Budraitskis: The Weakest Link of Managed Democracy: How The Parliament Gave Birth To Nonparliamentary PoliticsDocument17 pagesIlya Budraitskis: The Weakest Link of Managed Democracy: How The Parliament Gave Birth To Nonparliamentary PoliticsAnonymous NupZv2nAGlPas encore d'évaluation

- 2nd Version Conflict ManagmentDocument4 pages2nd Version Conflict ManagmentMai SabryPas encore d'évaluation

- Putin’s Russia (Revised and Expanded Edition)D'EverandPutin’s Russia (Revised and Expanded Edition)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (10)

- Political Change in RussiaDocument22 pagesPolitical Change in RussiaA.L.Pas encore d'évaluation

- Russias Elections and Managed DemocracyDocument3 pagesRussias Elections and Managed Democracyapi-164891616Pas encore d'évaluation

- In the Name of the People: How Populism is Rewiring the WorldD'EverandIn the Name of the People: How Populism is Rewiring the WorldPas encore d'évaluation

- A New Turn To Authoritarian Rule in RussiaDocument21 pagesA New Turn To Authoritarian Rule in RussiaqrazyPas encore d'évaluation

- Project Muse 886929Document15 pagesProject Muse 886929Aung MyintPas encore d'évaluation

- Authoritarian Countries in 21ST CenturyDocument13 pagesAuthoritarian Countries in 21ST Centuryyash A.Pas encore d'évaluation

- Stoner, 2023Document15 pagesStoner, 2023Saqlain RazaPas encore d'évaluation

- Vladimir Putin: Authoritarianism and Anti-AmericanismD'EverandVladimir Putin: Authoritarianism and Anti-AmericanismPas encore d'évaluation

- Democratization, Graduation, and Russia: Post-Communism Presents Three Studies That FulfillDocument12 pagesDemocratization, Graduation, and Russia: Post-Communism Presents Three Studies That FulfillRaluca MicuPas encore d'évaluation

- The Russian Protests and Putin's ChoicesDocument12 pagesThe Russian Protests and Putin's ChoicesCarnegie Endowment for International PeacePas encore d'évaluation

- Global Political Economy EssayDocument4 pagesGlobal Political Economy Essaygeorgeballgalceran1Pas encore d'évaluation

- Yeltsin IntroductionDocument2 pagesYeltsin IntroductionMárton PanghyPas encore d'évaluation

- What Is Sharp Poer - Walker2018Document16 pagesWhat Is Sharp Poer - Walker2018Javier CastrillonPas encore d'évaluation

- Illiberal Capitalism FTDocument4 pagesIlliberal Capitalism FTMila IvanovicPas encore d'évaluation

- Authoritarian State Building and The Sources of Regime Competitiveness in The Fourth Wave: The Cases of Belarus, Moldova, Russia, and UkraineDocument32 pagesAuthoritarian State Building and The Sources of Regime Competitiveness in The Fourth Wave: The Cases of Belarus, Moldova, Russia, and Ukrainei CristianPas encore d'évaluation

- Russia without Putin: Money, Power and the Myths of the New Cold WarD'EverandRussia without Putin: Money, Power and the Myths of the New Cold WarÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (5)

- Is Russia Under Putin A Democracy EssayDocument7 pagesIs Russia Under Putin A Democracy EssaydanPas encore d'évaluation

- Explaining Eastern Europe: What IsDocument16 pagesExplaining Eastern Europe: What Isjoao simoesPas encore d'évaluation

- Power Dynamics: Authoritarianism, Regimes, and Human Rights: Analyzing Authoritarian Regimes, Consolidation of Power, and Impact on Human Rights: Global Perspectives: Exploring World Politics, #3D'EverandPower Dynamics: Authoritarianism, Regimes, and Human Rights: Analyzing Authoritarian Regimes, Consolidation of Power, and Impact on Human Rights: Global Perspectives: Exploring World Politics, #3Pas encore d'évaluation

- Woodrow Wilson: Collected Works: The New Freedom, Congressional Government, George Washington, Essays, Inaugural Addresses…D'EverandWoodrow Wilson: Collected Works: The New Freedom, Congressional Government, George Washington, Essays, Inaugural Addresses…Pas encore d'évaluation

- Who Will Tell The People: The Betrayal Of American DemocracyD'EverandWho Will Tell The People: The Betrayal Of American DemocracyÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (22)

- Political Reform in Post-Mao China: Democracy and Bureaucracy in a Leninist StateD'EverandPolitical Reform in Post-Mao China: Democracy and Bureaucracy in a Leninist StatePas encore d'évaluation

- Summary Of "Constitution Theory" By Karl Loewenstein: UNIVERSITY SUMMARIESD'EverandSummary Of "Constitution Theory" By Karl Loewenstein: UNIVERSITY SUMMARIESPas encore d'évaluation

- What Is The Relationship Between Kleptocracy and AuthoritarianismDocument5 pagesWhat Is The Relationship Between Kleptocracy and AuthoritarianismMuhammad KashifPas encore d'évaluation

- Cesifo1 wp6864Document22 pagesCesifo1 wp6864Shahryar ShaukatAliPas encore d'évaluation

- Fateful Transitions: How Democracies Manage Rising Powers, from the Eve of World War I to China's AscendanceD'EverandFateful Transitions: How Democracies Manage Rising Powers, from the Eve of World War I to China's AscendancePas encore d'évaluation

- China and IndiaDocument3 pagesChina and IndiaPaul JennepinPas encore d'évaluation

- Breaking The Equilibrium From Distrust oDocument33 pagesBreaking The Equilibrium From Distrust owanjiruirene3854Pas encore d'évaluation

- Okila Kosimbekova. Final Essay. PoliticsDocument7 pagesOkila Kosimbekova. Final Essay. PoliticsRiley ButlerPas encore d'évaluation

- AuthoritarianismDocument9 pagesAuthoritarianismEnea Zenuni100% (1)

- Debating the American State: Liberal Anxieties and the New Leviathan, 193-197D'EverandDebating the American State: Liberal Anxieties and the New Leviathan, 193-197Pas encore d'évaluation

- The Congressional Government: A Study in American PoliticsD'EverandThe Congressional Government: A Study in American PoliticsPas encore d'évaluation

- Revolutionary Constitutions: Charismatic Leadership and the Rule of LawD'EverandRevolutionary Constitutions: Charismatic Leadership and the Rule of LawPas encore d'évaluation

- Conversations On RussiaDocument398 pagesConversations On RussiaAlexandru Irina100% (1)

- The Rise of Modern PopulismDocument2 pagesThe Rise of Modern PopulismAi ZhenPas encore d'évaluation

- The Modern State and Its Enemies: Democracy, Nationalism and AntisemitismD'EverandThe Modern State and Its Enemies: Democracy, Nationalism and AntisemitismPas encore d'évaluation

- Russia Paper 7-18-16Document5 pagesRussia Paper 7-18-16mccaininstitutePas encore d'évaluation

- Globalization and The Death of DemocracyDocument15 pagesGlobalization and The Death of DemocracyMaria Mercedes Prado EspinosaPas encore d'évaluation

- Founding Acts: Constitutional Origins in a Democratic AgeD'EverandFounding Acts: Constitutional Origins in a Democratic AgePas encore d'évaluation

- Can Law Protect Democracy?Document28 pagesCan Law Protect Democracy?Thaís CostaPas encore d'évaluation

- GelmanDocument10 pagesGelmanmeleshkinaPas encore d'évaluation

- Nationalization of The Future: Paragraphs Pro Sovereign DemocracyDocument15 pagesNationalization of The Future: Paragraphs Pro Sovereign DemocracyRaluca MicuPas encore d'évaluation

- Authoritarianism in Globalization: A Theoretical ConsiderationDocument18 pagesAuthoritarianism in Globalization: A Theoretical ConsiderationArunav Guha RoyPas encore d'évaluation

- The People vs. Democracy: Why Our Freedom Is in Danger and How to Save ItD'EverandThe People vs. Democracy: Why Our Freedom Is in Danger and How to Save ItÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (33)

- Incentives and Institutions: The Transition to a Market Economy in RussiaD'EverandIncentives and Institutions: The Transition to a Market Economy in RussiaPas encore d'évaluation

- The Essential Writings of President Woodrow Wilson: The New Freedom, Congressional Government, George Washington, Essays, Inaugural Addresses…D'EverandThe Essential Writings of President Woodrow Wilson: The New Freedom, Congressional Government, George Washington, Essays, Inaugural Addresses…Pas encore d'évaluation

- Putin Rusia ProtestDocument5 pagesPutin Rusia ProtestAnna MarksPas encore d'évaluation

- Edinburgh University Press The New Russian NationalismDocument29 pagesEdinburgh University Press The New Russian NationalismDahlia NoirPas encore d'évaluation

- FULL Dictatorship Reform RussiaDocument44 pagesFULL Dictatorship Reform RussiaokmokmPas encore d'évaluation

- Catalogue Maltep en PDFDocument88 pagesCatalogue Maltep en PDFStansilous Tatenda NyagomoPas encore d'évaluation

- ShindaiwaDgw311DmUsersManual204090 776270414Document37 pagesShindaiwaDgw311DmUsersManual204090 776270414JGT TPas encore d'évaluation

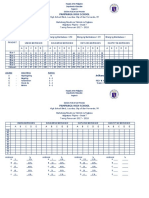

- Practical Research 2 - Chapter 1Document30 pagesPractical Research 2 - Chapter 1Luis ConcepcionPas encore d'évaluation

- Assignment On How To Increase Own Brand Mantras: Submition Date: January 29,2021Document5 pagesAssignment On How To Increase Own Brand Mantras: Submition Date: January 29,2021Ferari DroboPas encore d'évaluation

- Short Questions From 'The World Is Too Much With Us' by WordsworthDocument2 pagesShort Questions From 'The World Is Too Much With Us' by WordsworthTANBIR RAHAMANPas encore d'évaluation

- Exotic - March 2014Document64 pagesExotic - March 2014Almir Momenth35% (23)

- s4c Project - Hollie MccorkellDocument7 pagess4c Project - Hollie Mccorkellapi-662823090Pas encore d'évaluation

- Alternate History of The WorldDocument2 pagesAlternate History of The WorldCamille Ann Faigao FamisanPas encore d'évaluation

- Grade Up CurrentsDocument273 pagesGrade Up CurrentsAmiya RoyPas encore d'évaluation

- Napoleon Lacroze Von Sanden - Crony Capitalism in ArgentinaDocument1 pageNapoleon Lacroze Von Sanden - Crony Capitalism in ArgentinaBoney LacrozePas encore d'évaluation

- Principle of ManagementsDocument77 pagesPrinciple of ManagementsJayson LucenaPas encore d'évaluation

- Mapua Cwtsstudentsmodule (Ay08 09)Document62 pagesMapua Cwtsstudentsmodule (Ay08 09)anon-805332Pas encore d'évaluation

- Direct Method (Education) : Navigation SearchDocument5 pagesDirect Method (Education) : Navigation Searcheisha_91Pas encore d'évaluation

- Silent Reading With Graph1Document2 pagesSilent Reading With Graph1JonaldSamueldaJosePas encore d'évaluation

- Class 10 Science Super 20 Sample PapersDocument85 pagesClass 10 Science Super 20 Sample PapersParas Tyagi100% (1)

- Form Filling & Submission QueriesDocument3 pagesForm Filling & Submission QueriesMindbanPas encore d'évaluation

- UCCP Magna Carta For Church WorkersDocument39 pagesUCCP Magna Carta For Church WorkersSilliman Ministry Magazine83% (12)

- Thesis For Driving AgeDocument6 pagesThesis For Driving Agestefanieyangmanchester100% (2)

- Critical LengthDocument3 pagesCritical LengthRamiro RamirezPas encore d'évaluation

- CWWDocument2 pagesCWWmary joy martinPas encore d'évaluation

- All About Me - RubricDocument3 pagesAll About Me - Rubricapi-314921155Pas encore d'évaluation

- LTE Principle and LTE PlanningDocument70 pagesLTE Principle and LTE PlanningShain SalimPas encore d'évaluation

- Pegasus W200Document56 pagesPegasus W200Aleixandre GomezPas encore d'évaluation

- The Basics of Effective Interpersonal Communication: by Sushila BahlDocument48 pagesThe Basics of Effective Interpersonal Communication: by Sushila BahlDevesh KhannaPas encore d'évaluation

- Vishnu Dental College: Secured Loans Gross BlockDocument1 pageVishnu Dental College: Secured Loans Gross BlockSai Malavika TuluguPas encore d'évaluation

- 2014 Price ListDocument17 pages2014 Price ListMartin J.Pas encore d'évaluation

- (Downloadsachmienphi.com) Bài Tập Thực Hành Tiếng Anh 7 - Trần Đình Nguyễn LữDocument111 pages(Downloadsachmienphi.com) Bài Tập Thực Hành Tiếng Anh 7 - Trần Đình Nguyễn LữNguyên NguyễnPas encore d'évaluation

- Bond - Chemical Bond (10th-11th Grade)Document42 pagesBond - Chemical Bond (10th-11th Grade)jv peridoPas encore d'évaluation

- Micro Fibra Sintetica at 06-MapeiDocument2 pagesMicro Fibra Sintetica at 06-MapeiSergio GonzalezPas encore d'évaluation

- Introduction To Mechanical Engineering Si Edition 4Th Edition Wickert Lewis 1305635752 9781305635753 Solution Manual Full Chapter PDFDocument36 pagesIntroduction To Mechanical Engineering Si Edition 4Th Edition Wickert Lewis 1305635752 9781305635753 Solution Manual Full Chapter PDFwilliam.munoz276100% (13)