Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Gallois Berkeley's Master Argument

Transféré par

phgagnonDescription originale:

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Gallois Berkeley's Master Argument

Transféré par

phgagnonDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Philosophical Review

Berkeley's Master Argument Author(s): Andre Gallois Source: The Philosophical Review, Vol. 83, No. 1 (Jan., 1974), pp. 55-69 Published by: Duke University Press on behalf of Philosophical Review Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2183873 . Accessed: 04/04/2014 12:36

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Duke University Press and Philosophical Review are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Philosophical Review.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 140.209.2.26 on Fri, 4 Apr 2014 12:36:33 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

BERKELEY'S

MASTER ARGUMENT

the following Philonous, famous argumentoccurs which I shall referto as the master argument.

IN

THE first dialogueof the Three Dialogues between Hylasand

combination of qualities,or any sensibleobject whatever, to exist withoutthe mind, then I will grantit actually to be so." Hylas: "If it comesto thatthe pointwill soon be decided.What more easy to conceiveof a treeor a house existing by itself, independent of,and unperceived by any mindwhatsoever? I do at thismoment conceivethemexisting afterthat manner." Philonous:"How say you Hylas, can you see a thingwhichis at the same timeunseen?" Hylas: "No, thatwere a contradiction." Philonous: "Is it not as great a contradiction to talk of conceiving a thingwhichis unconceived ?" Hylas: "It is." Philonous:"The treeor housetherefore whichyou think ofis conceived by you." Hylas: "How should it be otherwise?" Philonous: "And what is conceived by you is surelyin the mind." Hylas: "Withoutquestion,that which is conceivedis in the mind." Philonous: "How then came you to say, you conceiveda house or tree existing independent, and out of all mindswhatsoever?" Hylas: "That I own was an oversight."' Berkeley in the person of Philonous appears to attach considerable weightto thisargument.It is introducedwith the words "But to pass by all that hath hithertobeen said, and reckon it for nothing I am content to put the whole on this issue." A like declaration precedes a similar argument in the Principles, which indicates that what, for this reason, I have called the "master argument" deserves more than the cursory attention that is usually given to it. As it is presented in the Dialogues the master argument seems

1

Philonous: ". . . If you can conceive it possible for any mixture or

Three Dialoguesbetween Hylas and Philonous, T. E. Jessop edition,p. 200.

55

This content downloaded from 140.209.2.26 on Fri, 4 Apr 2014 12:36:33 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

ANDRE GALLOIS

singularlyweak. It is temptingto dismissit on the grounds that Berkeleycommitsthefallacyofmovingfrom"necessarilywhatever is conceived is conceived" to "whatever is conceived is so necessarily." This charge can be restated in more detail as follows: Hylas does not content himself with the bare assertion that something might exist unconceived by anyone, but proceeds to give examples, "a tree or a house" which he conceived of existing "after that manner." Now the crucial step in the argument appears to be this. Any example of an unconceived object which Hylas cites in order to establishhis claim that such objects might, or indeed do, existis automaticallydeprived of that status by the very fact of Hylas' citing it as such. Let us grant forthe moment that the propositionthat some unconceived object exists can be justifiablyassertedonly if it is possible to mentionparticular examples of unconceived objects. Further let us grant that mentioningan object entails conceivingit. Conceding this much in no way tells against the logical possibilityof there being an unconceived object. At most we have no justificationforbelieving that such objects do exist,which does not by itself tell against believing that theymight.Philonous has gone no way toward showingthat the possibilityof somethingexistingunconceived is ruled out. Still the masterargumentwould be important,to say the least, if it demonstratedan epistemological restriction to thingswhich are in the mind in some strongersense than simply being the object of some mental state. Berkeleyappears, however,to give no reason forthinking that Philonous' claim "And what is conceived by you is surelyin the mind" is not either tautological or false. Another weakness of the Dialoguesversion of the master argument is that Berkeley conflatesthinkingof or about something with thinkingthat somethingis the case. Hylas contends that he can conceive' of a tree existing "independently of. . . any mind whatsoever." On the one hand, if conceiving of an object having a certain propertycannot be safelyidentifiedwith thinkingthat an object ofthat kind has that property, thenthe masterargument fails to get off the ground. It would then be open to Hylas to maintain that, though he may not be able to conceive of trees existing independent of the mind, this is compatible with him thinkingthat there are such. On the other hand, if conceiving of

56

This content downloaded from 140.209.2.26 on Fri, 4 Apr 2014 12:36:33 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

BERKELEr'S

MASTER ARGUMENT

an object having a propertycan be equated in the argumentwith thinkingthat objects of that kind have that property, then we can provisionallyoutline the masterargumentas follows.Let p be the propositionthat thereare treesunconceived by anyone. Then the desired conclusion is: It is not possible thatp. That is: (A)

(i)

(possibly p)

which is supposed to follow from: (3x) (x believes p) entails'p. (2) Hylas believes p.

p). (3) (3x) (x believes

As we have seen, this fails to establish (A) unless Berkeley is allowed the furtherunargued-for premise: possibly p entails (possibly (3x) (x believes p & p)). In any case, several crucial steps are clearly missingfromthe argument.Without some filling in, what reason is there to accept (i) ? It is at thispoint that the distinctionbetween thinking that and thinkingabout becomes important,for only the latter cognitive state can take a non-propositionalobject. Put another way, if I say that I am thinkingabout a tree, then, if asked, I should be able to produce an identifyingdescription of the tree about which I claim to be thinking-for example, the tallesttreein my garden. On the otherhand, I could perfectly well thinkthat there is a tree which, say, no one has ever perceived withoutcommiting myselfto producing on demand an identifying description of a particular unperceived tree. Philonous persuades Hylas that thereis somethingwhich is the object of Hylas's thoughtwhich Hylas thinksis not the object of any thought. Which-gives us step (i) since it implies that what Hylas thinks is false. Hylas might have replied that the only admission he is forcedto make is that he thinksthat thereis a tree which no one is thinkingabout, from which it does not follow that any tree is the object of Hylas's thought.That is, Philonous moves illegitimately from: Hylas thinks that (ix) (+x. no one is about to thinking x) (3x) (axe Hylas is thinkingabout X).2

2 Not to mention the factthatthe latterclaim has existential which import the former lacks.

57

This content downloaded from 140.209.2.26 on Fri, 4 Apr 2014 12:36:33 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

ANDRE GALLOIS

Berkeley'sconfusionof thinkingthat with thinkingof or about is understandablein the lightof his rejectionof abstractideas. All for Berkeleyabout anythingwe can be said to perceive thinking involves having ideas of objects with determinate properties. Sometimeshe appears to identify the ideas which accompany, or even constitute, with the objects of thought,treatingthe thinking, formeras if they instantiatedpropertieslike color and extension. At any rate, since thoughtabout a class of objects, for Berkeley, implies imaging a member of that class with determinatecharacit is natural for him to conflate thinkingof something teristics, with thinkingthat somethingis the case. In order to thinkabout a class, we must contemplate an object which functions as a of that class, of which we could produce an identirepresentative fyingdescription,since it has determinatecharacteristics. Together with Berkeley'sconflationof ideas and their objects, thereis a corresponding assimilationof having ideas to perceiving, where imaging is treated as a kind of self-inducedperception. Berkeley'sfailureto distinguish clearly between ideas and their objects on the one hand, and imaging and perceiving on the other,is particularlyevidentin the Principles versionof the master argument: But say you, surelythereis nothing easier than to imaginetrees,for instancein a park, or books in a closet,and no one by to perceive them.I answer, you may do so, thereis no difficulty in it, but what is all this,I beseechyou, morethanframing in yourmindcertainideas which you call books and trees,and at the same time omitting to frame theidea ofany one thatmay perceive ? But do not you yourself perceiveor thinkof themall the while? This therefore is nothingto the purpose:it onlyshowsyou have the powerof imagingor framing ideas in yourmind: but it doth not show thatyou can conceivethem unconceived or unthought existing of,whichis a manifest repugnancy.3 Berkeleyheld the view that words denote ideas,4 and that ifwe are not to be misled by language we must attend to the ideas correspondingto the words we are using. Any idea we attemptto "frame," correspondingto an expressionlike "unperceived tree"

3The Principlesof Human Knowledge,T. E. Jessop edition, sec. 23, p. 50. 4Which is not, of course, their only function or a function of all words.

58

This content downloaded from 140.209.2.26 on Fri, 4 Apr 2014 12:36:33 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

BERKELEr'$

MASTER ARGUMENT

has then to satisfy two incompatible requirements.It has to serve as the denotation of the expressionin question, and so must be unperceived. It must also be introspected-that is, perceived-by any person claiming to have such an idea. Grantingall that can be said against both versionsof the master argument,we mightquestion whetherthe foregoing criticisms are really as damaging as theyappear. While it is true that the argument requires considerable reformulationif it is to be at all persuasive, one is left with the persistentfeeling that Berkeley's central point so far has been missed. Though conceiving of, conceivingthat,imaging,and perceivingare distinguishable, they may turn out to be conceptually related in such a way that the master argumentretains much of its force. One of the most puzzling featuresof the Dialoguesversionof the master argument is that, even if valid, it is difficult to see what support it lends to Berkeley's central thesis that whatever is perceivable is perceived. One explanation we have already consideredis that Berkeley treatsconceivingas a species of perceiving. There is, however, another more interestingalternative. In the rest of this paper I shall tryto elaborate on the thoughtthat the Dialoguesand Principles versionsof the masterargumentcannot be properly understood in isolation from one another. I wish to suggest that the central point that emerges from both these argumentstaken togetherreflects on the conditionsfor ascribing the possessionof a particular concept namely, the concept of a perceivable. An individual mustsatisfy a numberofdiversecriteriabeforehe can be said to be in possession of a concept. One in particular concerns us here, a criterionthat has played a prominentrole in the history of philosophy which may be called the imagistic criterion.It can be stated simplyenough. In order forsomeone to have the concept of thingsof a certain kind, he must be able to image thingsof that kind. The same thing applies to the concept of an event, action, process,and so forth.' Some philosophershave talked as though concepts and images could be identified, but, of course, one need not take that view to see imaging as a necessarycomponent in conceptualizing. There are difficulties enough, however,with the thesisthat the capacity

59

This content downloaded from 140.209.2.26 on Fri, 4 Apr 2014 12:36:33 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

ANDRE GALLOIS

to image goes hand in hand with conceptual capacities. For one thing,an analysis of what it is to have a concept in termsof the at least ifit is allowed that abilityto image has an air ofcircularity, imaging itselfinvolves the exerciseof concepts. Be that as it may, the ability to image appropriatelyappears to be neithera necescondition for having a concept. It is not a sary nor a sufficient necessary condition, for an individual may have little or no capacity forimaging withoutin any way limitinghis capacity to think. Also, there seems to be a contingent limitation on the capacity of human beings generally to image certain things. A well-knownexample is that of the chilagon. It is not a sufficient conditionsince a given image may, as it were, do dutyfordistinct concepts,where possessionof the one does not imply possessionof the other. An image of Brigitte Bardot could serve equally well as an image of a woman or an image of a filmstar. All these objections against an imagistictheoryof what it is to have a concept are familiarenough, but thereremains a relation between imaging and the ascription of concepts which is worth exploring.If we say that someone has a concept of a certain kind, then one requirementhe must meet is that ifhe images at all with respect to anythingto which that concept applies, he must image correctly.One way of elucidating the force of this demand is to focus on the ways of describingwhat we can be said to image. I may image any one of a number of thingsifrequested to image, say, the Empire State Building, and may describe what I am ways. For example, I might imaging in a variety of different content myselfwith, say, the description"the tallest building in New York" or, more noncommittally, as just "a building in New York" or still more noncommittallyas "something oblong and grey." One thing I could not say without calling into question either my linguisticcompetence or my possessionof the concept of a building is that I am imaging somethingwith fourlegs and a head. We can then thinkof a concept as collectingtogethera class of images associated with it and, by a natural extension,the same concepts collecting together the same images. Of course, this illustrationof the point I wish to make about the relation of imaging and conceptualizingcould equally well be construedas a point about the way in which the sense of an expressiondepends

6o

This content downloaded from 140.209.2.26 on Fri, 4 Apr 2014 12:36:33 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

BERKELEr'S

MASTER ARGUMENT

on the truthconditionsof sentencesin which it figures.They are distinct,however, and putting the matter in terms of imaging rather than truthconditionswill serve, I believe, to get a firmer grasp on what Berkeleymight be saying. We are now in a position to resume discussion of the master argumentand see, in the lightof what has been said above about conceptualizing and imaging, how Berkeley might have sidebetween thinking stepped the objection that he failsto distinguish that, thinking about, and imaging. If someone claims that a propertycould be instantiated,then it seems reasonable to insist that he should be prepared to replace the initial variable in the descriptionso open sentence "x is s" with a definiteor indefinite that a closed sentencewhich could be trueobtains. In otherwords, a kind or kindsofthingswhich,though he should be able to specify not be, could be b.So in the passage quoted theymay contingently fromthe Dialogues,even had Hylas not done so in mentioninga tree and a house, Philonous would have been justifiedin asking Hylas to elaborate on his claim that somethingmightexistunperceived by mentioningthe sortsof thingsthat could so exist. Further,if Hylas thinksthat a b mightexist unperceived-say, a table-then it followsthat Hylas has the concept of an unperceived b; and if he has this concept then he can image appropriately with respect to it. This last step is important,forit bridges the gap between thinkingthat somethingperceivable mightexist unperceived and imaging an unperceivedperceivable. If it can be taken, then the complaint that one need not produce an identifyingdescriptionof an unperceived tree or house which one is currently imaging loses itsforce.It is true that one need not image a tree,stillless the treein one's neighbor'sgarden, while thinking that there is such a tree. The suggestionis rather that one must have the capacity, perhaps unrealized, to image a tree in order to entertainthis thought. So far nothing has been said about the necessary connection between being perceived and being perceivable which Berkeley wishesto argue for.It is now time to introduceinto the discussion Berkeley's test for necessary connections between properties. upon we discoversuch necessaryconnectionsby reflecting Briefly, our capacity to image something having one property while

6i

This content downloaded from 140.209.2.26 on Fri, 4 Apr 2014 12:36:33 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

ANDRE GALLOIS

lacking another.One major argumentthat Berkeleybringsagainst is thatit is inconceivable quality distinction the primary-secondary that anythingcould have extensionwithoutcolor, forin imaging factoimaging it as having some somethingas extended we are ipso color. This is not the place to launch into an elaborate defenseof the ofnecessity.(Some would deny imagisticcriterion much-criticized being necessarproperties thatit makes sense to talk about distinct ily connected at all and perhaps rely on a criterionrelated to an in termsoflinguisticconventionor stipulation analysisof necessity which is, I think,even less defensiblethan an imagisticcriterion.) It is appropriate, however, to say something here about the is based upon plausibilityof the thesisthat knowledgeof necessity imagination. of our powers of the limits about we discover what the view that of The major, and to many conclusive, criticism necessaryconnectionsare revealed by the powers of imagination is one we have already noted in another context-namely, that limited. It may be true,though such powers may be contingently is necessarcertainlyit is open to question,that because something ily not the case we cannot imagine it being the case, but the as it were, puts converseis not true.An imagistictestfornecessity, the cart beforethe horse. A good deal more space than I can devote here would be required to develop a really adequate reply to thispoint. I can at least indicate the outline of a reply, however. In brief,hypothesizing a necessaryconnectionbecause of a general failureto image thingsof a certainsortmay turnout to be the best explanation for such failure. Of course, this can amount to no more than a plea withoutelucidating fortoleranceforan imagistictestfornecessity in some detail what is meant by "best explanation" in thiscontext. I do not, however,propose to engage in that task here, since I am not out to establish the validity of the master argument,but only its considerable plausibility in the light of some assumptions themselvesnot implausible. It is now time to returnto the master argument and spell out these background assumptions. Whenever one can be said to image, one can be said to image a potential experience and moreoveran experience which is potentiallyone's own. One way

62

This content downloaded from 140.209.2.26 on Fri, 4 Apr 2014 12:36:33 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

BERKELEr'S

MASTER ARGUMENT

of making clearer this rathervague statementabout the relation between imaging and experiencingis as follows. Suppose that I am asked to image the table in the next room and describe what I am imaging. A typical descriptionmight be: a table with an oval brown top, white legs, and so forth.Now the list of features of the imaged table (which of course need not be construed as featuresof a mental picture) could equally well count as a list of featuresof what one perceives when one perceives a table. This bringsout the connectionbetween imaging and perceiving.In the case of visual imagerythe contentof an image is limited to what can be taken in at a glance. In thisway visual images can be said to reproduce visual experiencesthat one mighthave (which is not to say that they are a kind of self-inducedvisual experience). Consequently,imaging an x and imaging oneselfperceivingan x are not separable tasks.It makes perfectly good sense to talk about revisingmy imagery that is, replacing one image with anotherso that if the table contingently has some featureone can image it at one time having that feature,and at another as lacking that feature.I may image a table at one time as brown, at another as red. Puttingit, then, in termsof the featuresthat we can be said to image somethingas having: if I image the following,a table perceived by me, is there any featureof the object of my state of imaging which I can delete so that I am leftwith an image of a table but not an image of a table perceived by me? It is fairly clear that there is no such feature. If this is so then we can reconstructthe master argument as follows: Hylas thinksthat possibly (3x) (x is perceivable and x is unperceived). (2) If what Hylas thinksis true, then the concepts beingthe and being the object of possible object of some perception someperception do not necessarily apply to the verysame things. (3) In order to sustain the claim that somethingcould be both perceivable and unperceived, it must be possible to have an image of a perceivable which is not an image of somethingperceived.

(i)

63

This content downloaded from 140.209.2.26 on Fri, 4 Apr 2014 12:36:33 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

ANDRE GALLOIS

([s] follows from [2] in conjunction with an imagistic criterionof necessity,the demand that Hylas be in a position to mention the kind of thing that could be both perceivable and unperceived, and finally,that he can image appropriately something of this kind if he is to qualify as having the concept of an unperceived perceivable).

embodiedin (3) and (4) Hylas cannotmeet the condition

his failure in this respect is not the result of a contingent limitation of Hylas's powers of imaging.

The desired conclusion that nothing could be both perceivable and unperceived follows. of the master argument is not That the above reconstruction unfaithfulto Berkeley is, I submit, indicated in the following passage fromthe Principles: and motionfrom when we attemptto abstractextension So likewise, we presently all other qualities, and considerthem by themselves, All of which lose sightof them,and run into great extravagancies. it is supposedthat extension, first depend on a two foldabstraction: fromall othersensiblequalitiesand forexample,may be abstracted its being from ofextension may be abstracted thatthe entity secondly perceived.5 Now it may be that in this passage Berkeleyis attemptingno more than to remindthe reader of his earlier argumentsconcerning the primary-secondaryquality distinction, abstract ideas, and the esse est percipiprinciple. I think it is more plausible, however, to suppose that he is doing more than this: that is, pointing to a connection between these arguments.Just as we cannot image somethingas extended and colorless,so we cannot image somethingas extended and unperceived.We could say that though we cannot image an unperceived perceivable we may still have an abstract idea of it were it not, Berkeleywould reply,for the incoherence, or, at least, obscurityof this notion. This last remarkmakes it look as though the plausibilityof the master argument is contingent upon the success of Berkeley's

5 Principles, sec.

99, p. 85.

64

This content downloaded from 140.209.2.26 on Fri, 4 Apr 2014 12:36:33 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

BERKELEY'S MASTER ARGUMENT

attack on abstract ideas. Now certainlyBerkeleyseemed to think that this is in fact the case. Then the master argumentwould be open to the criticismthat Berkeley's rejection of abstract ideas resultsfromconfusing a concept with an image, a criticism which I think would be misplaced. It would be misplaced because, as I have tried to show, this step in the argumentcan be restatedas a point about the relation between concepts and images and does not depend on identifying them. Can we accept the validityof the masterargumentin itspresent form? Certainly it would be difficult to accept and would have been difficult for Berkeleyto have accepted, for we can equally derive fromit a solipsisticconclusion for there is no distinctive featurewhich an experienceis imaged as having when one images it as potentiallyone's own. This is one way ofintroducing what, it seemsto me, is the central flaw in the master argument. That is to regard being the object of some perception as a featurethat somethingcould be imaged as having, and to conclude that since nothingcould be imaged as lacking this feature,then necessarilyif anythingis perceivable it is perceived. What is wrongwith thismove is that one cannot talk about imaging somethingas perceived in the same way that one can talk about imaging somethingas brown. "Is perceived" is not a predicate that could figurein any descriptionof what one is imaging. So any talk of, as it were, abstracting the associated propertyfromthe contentof one's imageryis inappropriate. It would be unsatisfactory to leave the matter here without saying somethingabout why being perceived is not an imageable featurein the way in which being brown is. If my interpretation of the master argumentis correct,it turnson two points: that we cannot discriminatebetween imaging a potential perception of something and imaging something potentially perceivable, and that thereis no difference in the contentof one's imagerybetween a imaging potential perceptionof somethingand imaging oneself in that perceptual state. If there were a differencebetween imaging a perceptual experience and imaging oneselfhaving that perceptual experience, then the master argument would fail. At mostwe could derive fromit the ratherunexcitingconclusion that whatever is perceivable is perceivable. In order to image some65

This content downloaded from 140.209.2.26 on Fri, 4 Apr 2014 12:36:33 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

ANDRE GALLOIS

thingperceivable we mustimage it as perceivable-that is, as the object of a possible perceptual experience-rather than as perceived-that is, as the object of someone's perceptual experience; namely, our own. In recent discussionson the subject of the ascriptionof mental states,it has been pointed out6that one could not ascribe a present mental state to oneselfon the basis of a distinctivecharacteristic of that state which marksit, so to speak, as one's own. In order to do so one would have to be in the mental state in question and so be in a position to recognize it as one's own. In the light of this remarkit is hardlysurprising that to image a perceptual state is to image being in that perceptual state. It is not that in imaging a perceptual state it is impossible to abstract from the content of one's imagerythat featurewhich makes the perceptual state one's own, but rather that it makes no sense to talk about any mental state having such a feature. It may seem fromthe last few remarksthat I am in danger of confusinga feature of an object of a perceptual state-namely, being the object of a perceptual state-with a feature of a perceptual state-namely, being someone's perceptual state. This, however,is not so. Rather my argumentis that if we wish to talk about the propertyof being perceived as an imageable feature, then we can do so only if there is some distinctivecontent to an image of a perceived object. How could there be any such distinctivecontentto one's imagery? As we have seen, the claim that to image somethingthat could be perceived is to image it as the object of a perceptual state can be interpretedin a more or less innocuous way. Interpretedone way, all this amounts to is that in imaging an object one is imaging it as having those propertieswhich could be mentionedin a descriptionof what one perceivesif one perceivesthat object. Interpretedin anotherway, it becomes the more exciting thesisthat, included in the content of one's imagery, and necessarily so, is some feature which indicatesthat the object is the object ofsomeone's perceptual state.

6 See: Shoemaker, SelfKnowledge andSelfIdentity, (Ithaca, 1963); J. Bennett, Kant's Analytic (Cambridge, i966); P. F. Strawson, TiheBoundsof Sense

(London, I 966).

66

This content downloaded from 140.209.2.26 on Fri, 4 Apr 2014 12:36:33 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

BERKELEr'S

MASTER ARGUMENT

My suggestionis then that the only candidate forthis role would be a featurewhich an individual's perceptual states must have in common in order forhim to count7 them as his perceptual states. If this is correct, the question then is can there be any such ? feature Giving a negative answer to this question leaves open the alternatives.Eitherit is not possibleforsomeone imaging following a potential experience to discriminateon the bases of the content of his imagery (what featureshe images the experience as having) between imaging that experienceas his own and just imaging that experience,because ifwe image an experiencewe mustimage it as having that feature which makes it someone's experience, or because it is simply inappropriate to talk about imaging experiences as having some featurein virtueof which theyare owned. If one opts forthe first alternative,then since imaging something that could be perceived amounts to imaging the kinds of experiences one would have in perceivingit, the conclusionofthe master argumentwould be difficult to reject. Not to mention a stronger conclusion.On the otherhand, ifone opts forthe second solipsistic alternative, then the master argument loses its force, for its plausibility,as we have seen, depends on the acceptability of an imagistic criterionof necessity,and such a criterionapplies only to imaged features. Ironically, Berkeleychose the first alternative and gave in the the central reason forchoosing the second. Principles8 It will perhapsbe said, thatwe want a sense (as somehave imagined) properto know substances withal,which if we had, we mightknow To thisI answer,that in case we our own soul, as we do a triangle. had a new sense bestowedupon us, we could only receive thereby some new sensations of ideas of sense.But I believeno body will say,

The phrase "in order for him to count" is crucial here. There may be a characteristic which all my mental states must share, in order to count as mine: e.g., if what is often referred to as a no-ownership theory is correct, that they all stand in a determinate causal relationship to states of a particular body. The point, however, is that it could not be on the basis of recognizing that a given mental state has this characteristic that I recognize that it is mine. 8 Principles, sec. I36, pp. I03-I04. 67

This content downloaded from 140.209.2.26 on Fri, 4 Apr 2014 12:36:33 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

ANDRE GALLOIS

that what he means by the termssoul and substance,is only some infer, that all We may therefore particularsortof idea or sensation. our faculties to think reasonable is not more it duly considered, things or active in thattheydo notfurnish us withan idea ofspirit defective, not than it would be ifwe shouldblame themfor substance, thinking a round square. being able to comprehend What I thinkBerkeleyis pointingto here is that no matterwhat features our experiences have, we could not recognize an experience as our own in virtueof recognizingthat it has some feature, for in order to effectthe latter recognitionwith respect to any given experience we must be in a position to recognize that we have it. In particular, we could not ascribe experiences to ourselves in virtue of standing in some relation to an experience of would arise forthe ourselves,forthe same problem of ascribability latter. In the light of this considerationit is no surprisethat imaging in termsof the contentofwhat an experienceis not distinguishable is imaged from imaging oneself having that experience. How content,since iftherewere we could therebe any such distinctive could on that basis ascribe experiences to ourselves in a way in which we cannot? If this analysis of the basic flawof the masterargumentis substantiallycorrect,then the argumentamounts to somewhat more than the trivial sophism it is oftenmade out to be. Berkeleywas obtaining philosophical mileage from an unclarity about the conditions for the self ascription of experiences which was unresolved,I believe, until Kant's discussionof these issues in the Critique. It must seem to many that my discussionof Berkeleyhas been rather anachronistic: framedin termsthat he would never have used. To those who feel this way I offerthe followingdefense.A to expressa point ofcentralimportance philosopherin attempting to him might have been able to do so with greatersuccess had developed at a later point in the history concepts and distinctions of philosophy been available to him at that time. For those who followthereis always the risk,utilizingsuch concepts and distincto state them with greater his views in an effort tions,of distorting I forceand clarity.It is a riskwhich thinkought to be taken when 68

This content downloaded from 140.209.2.26 on Fri, 4 Apr 2014 12:36:33 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

BERKELEY'S MASTER ARGUMENT

with an argumentwhich is at once suggestive,puzzconfronted importance to the philosopher in question and, obvious ling, of on the surface at least, lacking in plausibility. Such is the case, I would say, with Berkeley'smaster argument.

ANDRE GALLOIS

ofFlorida University

69

This content downloaded from 140.209.2.26 on Fri, 4 Apr 2014 12:36:33 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- Visit WWW - Csstimes.pk To Download More E-BooksDocument222 pagesVisit WWW - Csstimes.pk To Download More E-Bookskashif saleem100% (1)

- 3-Minute French 25 Lesson SeriesDocument117 pages3-Minute French 25 Lesson SeriesAFAPas encore d'évaluation

- Eng3 - Q4 - Module 3 - Degrees of Adjective - V4Document10 pagesEng3 - Q4 - Module 3 - Degrees of Adjective - V4Mary Cris Lutao89% (9)

- Ontological Argument For The Existence of GodDocument7 pagesOntological Argument For The Existence of GodWilliam GallasPas encore d'évaluation

- Module III - Punctuation and CapitalizationDocument110 pagesModule III - Punctuation and CapitalizationAnonymous FHCJucPas encore d'évaluation

- Arrernte Wilkins1989Document665 pagesArrernte Wilkins1989cecihauffPas encore d'évaluation

- Reiner Schürmann - The Ontological DiferenceDocument25 pagesReiner Schürmann - The Ontological DiferenceÖvül Ö. DurmusogluPas encore d'évaluation

- Groundless Belief: An Essay on the Possibility of Epistemology - Second EditionD'EverandGroundless Belief: An Essay on the Possibility of Epistemology - Second EditionPas encore d'évaluation

- Rance Gilson Newman BlondelDocument13 pagesRance Gilson Newman BlondelphgagnonPas encore d'évaluation

- Kripke - Naming and Necessity SummaryDocument4 pagesKripke - Naming and Necessity SummaryMaria Sri PangestutiPas encore d'évaluation

- Turkish Grammar Updated Academic Edition Yüksel Göknel October 2012 PDFDocument438 pagesTurkish Grammar Updated Academic Edition Yüksel Göknel October 2012 PDFCristinaPas encore d'évaluation

- Reichmann Scotus and Hæcceitas Aquinas and Esse PDFDocument13 pagesReichmann Scotus and Hæcceitas Aquinas and Esse PDFphgagnonPas encore d'évaluation

- The Intentionality of Sensation: A Grammatical FeatureDocument21 pagesThe Intentionality of Sensation: A Grammatical Featureapi-26004537Pas encore d'évaluation

- Who Designed the Designer?: A Rediscovered Path to God's ExistenceD'EverandWho Designed the Designer?: A Rediscovered Path to God's ExistenceÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (5)

- Carraro Deleuze's Aesthetic Answer To Heraclitus-The Logic of SensationDocument25 pagesCarraro Deleuze's Aesthetic Answer To Heraclitus-The Logic of SensationphgagnonPas encore d'évaluation

- Possessive PronounsDocument12 pagesPossessive PronounsJojj LimPas encore d'évaluation

- Handout Berkeley First DialogueDocument14 pagesHandout Berkeley First DialoguebezimenostPas encore d'évaluation

- Berkeley The Master ArgumentDocument3 pagesBerkeley The Master ArgumentLeonard_CPas encore d'évaluation

- Causal Necessity and The Ontological ArgumentDocument11 pagesCausal Necessity and The Ontological ArgumentAdam RafkinPas encore d'évaluation

- DescartesDocument4 pagesDescartesmaximilliandhutchingsPas encore d'évaluation

- Duke University Press Philosophical ReviewDocument7 pagesDuke University Press Philosophical ReviewRuan DuartePas encore d'évaluation

- Bandini Aude Perception & Its Givenness 15Document17 pagesBandini Aude Perception & Its Givenness 15Felipe ElizaldePas encore d'évaluation

- 701 800Document116 pages701 800readingsbyautumnPas encore d'évaluation

- 2.4 Complex ArgumentsDocument4 pages2.4 Complex ArgumentsraiyanduPas encore d'évaluation

- Locke Empirical KnowledgeDocument21 pagesLocke Empirical KnowledgeRichardo ManahanPas encore d'évaluation

- MooreRefute PDFDocument12 pagesMooreRefute PDFPritish MohanPas encore d'évaluation

- Fuller - The Theory of God in Book Λ of Aristotle's MetaphysicsDocument15 pagesFuller - The Theory of God in Book Λ of Aristotle's MetaphysicsScottPas encore d'évaluation

- Intuition&Inference FinalDocument12 pagesIntuition&Inference Finaljswenson2011Pas encore d'évaluation

- Descartes Ms WebDocument18 pagesDescartes Ms Webg526159Pas encore d'évaluation

- Nyaay Proofs For Soul - A ChakravartiDocument28 pagesNyaay Proofs For Soul - A ChakravartimprussoPas encore d'évaluation

- Hume Dialogues - 9 To EndDocument25 pagesHume Dialogues - 9 To EndDaniel BalurisPas encore d'évaluation

- Bimal Krishna Matilal-Perception - An Essay On Classical Indian Theories of Knowledge - Oxford University Press, USA (1986)Document44 pagesBimal Krishna Matilal-Perception - An Essay On Classical Indian Theories of Knowledge - Oxford University Press, USA (1986)DanielmetalattackPas encore d'évaluation

- Arguments For The Existence of GodDocument27 pagesArguments For The Existence of GodBrito RajPas encore d'évaluation

- Berkeley - 3 DialoguesDocument65 pagesBerkeley - 3 DialoguesConniePas encore d'évaluation

- Jimenez - Christian Evidences 3Document7 pagesJimenez - Christian Evidences 3David JiménezPas encore d'évaluation

- Scots Philosophical Association University of St. AndrewsDocument14 pagesScots Philosophical Association University of St. AndrewsAlice SilvaPas encore d'évaluation

- A Christian and Intelligent DesignDocument17 pagesA Christian and Intelligent Designapi-314366077Pas encore d'évaluation

- Berkeley 1713 Part 1Document27 pagesBerkeley 1713 Part 1Omar MarínPas encore d'évaluation

- Review of Alan Sidelle, Necessity, Essence and IndividuationDocument5 pagesReview of Alan Sidelle, Necessity, Essence and IndividuationTristan HazePas encore d'évaluation

- Bunge-New Dialogues Between Hylas and PhilonousDocument9 pagesBunge-New Dialogues Between Hylas and Philonousfmedina491922100% (1)

- Ontological Argument EssayDocument7 pagesOntological Argument EssayafmocrkjbPas encore d'évaluation

- Qualia and The Argument From Illusion - A Defence of FigmentDocument20 pagesQualia and The Argument From Illusion - A Defence of FigmentPraveen MeduriPas encore d'évaluation

- Fodor WithoutWhatswithin 2001Document51 pagesFodor WithoutWhatswithin 20011376070274Pas encore d'évaluation

- 10 Strangest Philosophies Created by ManDocument3 pages10 Strangest Philosophies Created by MangsakuraiPas encore d'évaluation

- Ansel Ontological ArgumentDocument14 pagesAnsel Ontological ArgumentRafael RoaPas encore d'évaluation

- Malcolm, Norman. 'Anslem's Ontological Arguments.'Document23 pagesMalcolm, Norman. 'Anslem's Ontological Arguments.'Oscar MacePas encore d'évaluation

- Problems of PhilosophyDocument6 pagesProblems of PhilosophySubhendu GhoshPas encore d'évaluation

- Holbrook - Descartes On PersonsDocument6 pagesHolbrook - Descartes On PersonsJuanPas encore d'évaluation

- Are Beliefs About GodDocument22 pagesAre Beliefs About GodMylen Maygay GambetPas encore d'évaluation

- Responding To SkepticismDocument26 pagesResponding To SkepticismLookinglass1Pas encore d'évaluation

- Berkeley's Three Dialogues between Hylas and PhilonousD'EverandBerkeley's Three Dialogues between Hylas and PhilonousPas encore d'évaluation

- A Leibnizian Cosmological ArgumentDocument21 pagesA Leibnizian Cosmological Argumentnellyv319Pas encore d'évaluation

- Hegeler InstituteDocument25 pagesHegeler InstituteRené Francisco Gómez ChávezPas encore d'évaluation

- Dissertation Chapter 1Document23 pagesDissertation Chapter 1Noam HofferPas encore d'évaluation

- Rethinking The Ontological Argument: A Neoclassical Theistic Response, by DanielDocument3 pagesRethinking The Ontological Argument: A Neoclassical Theistic Response, by DanielRuan DuartePas encore d'évaluation

- Science Cannot Determine Human Values-LibreDocument4 pagesScience Cannot Determine Human Values-LibrehoangvietmangmtPas encore d'évaluation

- Patryk Filozofia. WordDocument5 pagesPatryk Filozofia. Wordmonikalea6Pas encore d'évaluation

- Berkeley and HumeDocument22 pagesBerkeley and HumeAlia Hammad Naushahi100% (1)

- Can It Be Shown That GodDocument5 pagesCan It Be Shown That Godmichaelsifeldeen100% (1)

- Descartes EssayDocument5 pagesDescartes EssayPaul HanPas encore d'évaluation

- Antony Flew - Theology and FalsificationDocument3 pagesAntony Flew - Theology and FalsificationLuis DelgadoPas encore d'évaluation

- Forgie 1975Document21 pagesForgie 1975Kenneth DavisPas encore d'évaluation

- 1 11 Sellars PDFDocument39 pages1 11 Sellars PDFGabriela LoulyPas encore d'évaluation

- Platonic Anamnesis Revisited Author(s) : Dominic Scott Source: The Classical Quarterly, New Series, Vol. 37, No. 2 (1987), Pp. 346-366 Published By: On Behalf of Stable URL: Accessed: 08/05/2013 20:40Document22 pagesPlatonic Anamnesis Revisited Author(s) : Dominic Scott Source: The Classical Quarterly, New Series, Vol. 37, No. 2 (1987), Pp. 346-366 Published By: On Behalf of Stable URL: Accessed: 08/05/2013 20:40James Gildardo CuasmayànPas encore d'évaluation

- Sed Vitae, Non Scholae Discimus I.: Meaning of The Word PhilosophyDocument12 pagesSed Vitae, Non Scholae Discimus I.: Meaning of The Word PhilosophyAlexaPas encore d'évaluation

- Peter Bayles CosmologyDocument14 pagesPeter Bayles CosmologycotwancoPas encore d'évaluation

- Kant - A To Any Future Met A PhysicDocument87 pagesKant - A To Any Future Met A PhysicAhmad AlhourPas encore d'évaluation

- Is There A Mind-Body ProblemDocument12 pagesIs There A Mind-Body ProblemjohnPas encore d'évaluation

- Bub in Defense of A "Single-World" Interpretation of Quantum MechanicsDocument5 pagesBub in Defense of A "Single-World" Interpretation of Quantum MechanicsphgagnonPas encore d'évaluation

- Dusek Review Fuller Dissent On DescentDocument12 pagesDusek Review Fuller Dissent On DescentphgagnonPas encore d'évaluation

- Sadler The 1930s Christian Philosophy DebatesDocument14 pagesSadler The 1930s Christian Philosophy DebatesphgagnonPas encore d'évaluation

- Gelernter The Closing of The Scientific MindDocument9 pagesGelernter The Closing of The Scientific MindphgagnonPas encore d'évaluation

- KullDocument21 pagesKullphgagnonPas encore d'évaluation

- Katz R L Gregory and Other-The Wrong PictureDocument11 pagesKatz R L Gregory and Other-The Wrong PicturephgagnonPas encore d'évaluation

- Midgley Duties Concerning IslandsDocument8 pagesMidgley Duties Concerning IslandsphgagnonPas encore d'évaluation

- Duns The Lord Has Made All Things-Creatio Ex Nihilo and Theological ImaginationDocument8 pagesDuns The Lord Has Made All Things-Creatio Ex Nihilo and Theological ImaginationphgagnonPas encore d'évaluation

- Wimsatt Memetics Does Not Provide A Useful Way of Understanding Cultural EvolutionDocument10 pagesWimsatt Memetics Does Not Provide A Useful Way of Understanding Cultural EvolutionphgagnonPas encore d'évaluation

- Simpson Bayes at Bletchley ParkDocument5 pagesSimpson Bayes at Bletchley ParkphgagnonPas encore d'évaluation

- Simon Can There Be A Science of Complex Systems? PDFDocument12 pagesSimon Can There Be A Science of Complex Systems? PDFphgagnonPas encore d'évaluation

- Grammar Essentials Learning Express Basic SkillsDocument224 pagesGrammar Essentials Learning Express Basic SkillsAri Tata AdiantaPas encore d'évaluation

- Heidegger's LichtungDocument2 pagesHeidegger's LichtungRudy BauerPas encore d'évaluation

- Anul III Stit Teoria Traducerii Oct 2016Document43 pagesAnul III Stit Teoria Traducerii Oct 2016Monica Dobre100% (1)

- Semantic NetworksDocument3 pagesSemantic Networksskaushik2410Pas encore d'évaluation

- Coursework - Reflexive Pronouns in Modern EnglishDocument4 pagesCoursework - Reflexive Pronouns in Modern EnglishZhanetPas encore d'évaluation

- HuangYan 2007 1introduction PragmaticsDocument20 pagesHuangYan 2007 1introduction PragmaticsMonikrqPas encore d'évaluation

- English Language and Literature Technical TermsDocument16 pagesEnglish Language and Literature Technical TermsAbeera AliPas encore d'évaluation

- PRATICE TEST Parts of SpeechDocument7 pagesPRATICE TEST Parts of Speechamin 99Pas encore d'évaluation

- German Vocab L1Document16 pagesGerman Vocab L1Matko MaršićPas encore d'évaluation

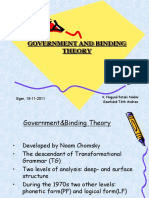

- Government and Binding TheoryDocument14 pagesGovernment and Binding TheoryNoémi K. Nagyné PatakiPas encore d'évaluation

- Dap An Thi Thu Tieng Anh Chuyen Nguyen HueDocument2 pagesDap An Thi Thu Tieng Anh Chuyen Nguyen HueĐăng ThưPas encore d'évaluation

- Wuolah Free PEC2201516expDocument10 pagesWuolah Free PEC2201516expkotyPas encore d'évaluation

- Semantic 1Document9 pagesSemantic 1Lan PhamPas encore d'évaluation

- 3 Types of PronounsDocument18 pages3 Types of PronounsJoemeniel S. AmbrocioPas encore d'évaluation

- GRE AntonymsDocument96 pagesGRE AntonymsmahamnadirminhasPas encore d'évaluation

- Dan Nhap Ngon Ngu - 8h00Document6 pagesDan Nhap Ngon Ngu - 8h00Khanh LePas encore d'évaluation

- THE Relationship Between Case AND AgreementDocument25 pagesTHE Relationship Between Case AND AgreementAnonymous R99uDjYPas encore d'évaluation

- Final Model Test-05 Set-01Document8 pagesFinal Model Test-05 Set-01Kawser Ahmed RaihanPas encore d'évaluation

- Tugas Bahasa InggrisDocument3 pagesTugas Bahasa InggrisSyafira MpuhuPas encore d'évaluation

- AdjectiveDocument7 pagesAdjectiveMalik Muhammad UsmanPas encore d'évaluation

- Language Processing Analysis of Source Program Synthesis of Target ProgramDocument13 pagesLanguage Processing Analysis of Source Program Synthesis of Target Programwww.entcengg.comPas encore d'évaluation

- Modern Greek DitransitivesDocument6 pagesModern Greek DitransitivesAlexandra FPas encore d'évaluation