Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Greiner Und Sakdapolrak - Translocality - Submitted Version

Transféré par

gioanelaCopyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Greiner Und Sakdapolrak - Translocality - Submitted Version

Transféré par

gioanelaDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

AccepLed for publlcaLlon ln Ceography Compass

1

Translocality: Concepts, applications and emerging research perspectives 1

Clemens Greiner & Patrick Sakdapolrak 2

3

Abstract 4

The employment of translocality as a research perspective is currently gaining 3

momentum. A growing number of scholars from different research traditions 6

concerned with the dynamics of mobility, migration and socio-spatial 7

interconnectedness have developed conceptual approaches to the term. They 8

usually build on insights from transnationalism, while at the same time attempting to 9

overcome some of the limitations of this long-established research perspective. As 10

such, translocality is used to describe socio-spatial dynamics and processes of 11

simultaneity and identity formation that transcend boundaries including, but also 12

extending beyond, those of nation states. In this review we trace the emergence of 13

the idea of translocality and summarise the characteristics that different authors 14

associate with the term. We elucidate the underlying notions of mobility and place, 13

and sketch out fields of research where the concept has been employed. On the 16

basis of our findings, we conclude by proposing key areas where a translocal 17

approach has the potential to generate fruitful insights. 18

Key words: translocality, spatial theory, migration, transnationalism 19

20

AccepLed for publlcaLlon ln Ceography Compass

2

Why write about translocality? 21

Translocality has come into vogue. As a catchword it appears in the writings of 22

scholars from a variety of disciplinary backgrounds, such as geography (Castree 23

2004, Conradson and McKay 2007, Steinbrink 2009, Brickell and Datta 2011b, 24

Featherstone 2011, Hedberg and do Carmo 2012a, Verne 2012), history and area 23

studies (Oakes and Schein 2006b, Freitag and von Oppen 2010b), cultural studies 26

(Ma 2002, Bennett and Peterson 2004), anthropology (Escobar 2001, Appadurai 27

2003, Peleikis 2003, Marion 2005, Argenti and Rschenthaler 2006, Nez-Madrazo 28

2007, Gottowik 2010, Greiner 2010) and development studies (Grillo and Riccio 29

2004, Zoomers and Westen 2011). Sometimes, translocality (or translocalism) is 30

merely used as a synonym for transnationalism. In most cases, however, it is used to 31

build upon and extend insights from this long-established research tradition. As such, 32

the term usually describes phenomena involving mobility, migration, circulation, and 33

spatial interconnectedness not necessarily limited to national boundaries. But what 34

can the idea of translocality offer beyond these obvious similarities? How is it defined 33

by those authors who employ it? Is it merely an extension of transnationalism, or 36

should it be understood as a theoretical concept in its own right? 37

In this review, we critically engage with these questions. We start by tracing the 38

conceptual relation between transnationalism and translocality and explore how the 39

latter serves to overcome some of the conceptual weaknesses of the former. We 40

then turn to the current literature in order to determine the similarities and differences 41

between the various current definitions of translocalism and to explore two central 42

dimensions of the concept: mobility and place. We briefly review research areas 43

where the concept has been applied so far, and by extension postulate that the 44

concept should be considered a research perspective in its own right (rather than 43

AccepLed for publlcaLlon ln Ceography Compass

3

merely an extension of transnationalism). We conclude by pointing out some of the 46

concept's potentialities. 47

48

Expanding the concept of transnationalism 49

When theories of transnationalism emerged out of the necessity to conceptualise 30

social fields that increasingly transcended national borders and to challenge existing 31

concepts of nationhood and citizenship (Basch, Glick Schiller and Szanton Blanc 32

1995), they were primarily concerned with processes of de-territorialisation and 33

notions of spatially unbounded communities (Hannerz 1996, Castells 2000, 34

Appadurai 2003). While the concept of rootedness, understood as a firm 33

relationship between identity and territory, has been questioned in Social 36

Anthropology and related disciplines (Malkki 1992; Gupta and Ferguson 1992), 37

empirical studies point to a global (re-)emergence of territorialised notions of 38

belonging and of ethno-nationalist movements (Geschiere 2009), which have led to 39

an academic rediscovery of the importance of the local (Kokot 2007). Since the mid- 60

1990s scholars of transnationalism have engaged with more localised phenomena of 61

international migration (Ley 2004). This shift has been reflected in growing concerns 62

over local-to-local relations (Guarnizo and Smith 1998), transnational urbanism 63

(Smith 2001) and cultural sites (Olwig 1997), which contributed to more 64

territorialised notions of transnationalism, and highlighted the articulation of global 63

and local dynamics in specific localities such as cities, neighbourhoods, homes and 66

families. While transnationalism is clearly an attempt to overcome the limitations of 67

methodological nationalism (Wimmer and Glick Schiller 2002), the primary concern 68

still rests on the transgression of and exchange beyond national borders. The 69

concept furthermore remains deeply anchored in the notion of the world as formed 70

AccepLed for publlcaLlon ln Ceography Compass

4

and ordered by a static framework of clearly distinguishable scales (Amelina 2010; 71

Verne 2012). 72

Authors applying the concept of translocality commonly base their writings on the 73

insights of transnational approaches. Following the shift toward a more grounded 74

transnationalism (Brickell and Datta 2011a, p. 3), they are concerned with local 73

contexts and the situatedness of mobile actors. At the same time, they expand their 76

analytical focus beyond the limits of the nation-state (Oakes and Schein 2006b) by 77

focusing on various other dimensions of border transgressions and on socio-spatial 78

configurations beyond those induced by human migration (Uimonen 2009, Gottowik 79

2010). This move has been long overdue for various reasons. 80

Firstly, from a historical standpoint, in much of the Global South nation-building is a 81

recent phenomenon, while interregional exchange dates back much further (for 82

example throughout the Arab world or within the Indian Ocean region; Freitag and 83

von Oppen 2010a, Verne 2012). Secondly, international boundaries in many former 84

colonies were drawn arbitrarily and enforced only poorly, as a consequence of which 83

the distinction between domestic and international migration is almost rendered 86

obsolete. In much of Africa, for example, international migration sometimes involves 87

relatively shorter distances and less social heterogeneity () and fewer barriers than 88

internal migration (Adepoju 2006, p. 28). Thirdly, the focus on transnational 89

movements has led to the neglect of internal migration, which makes up the bigger 90

share of global migration dynamics (Trager 2005). According to recent estimates of 91

the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) there are currently about 740 92

million internal migrants worldwide, while the number of international migrants is 93

comparatively small; only 214 million (UNDP 2009, p. 21). Fourthly, socio-economic 94

disparities and spatially uneven development, which are often considered major 93

AccepLed for publlcaLlon ln Ceography Compass

3

push-and-pull factors in international migration (Faist and Reisenauer 2009), not only 96

occur between nations but are also apparent within national borders. Lastly, research 97

on transnational migrant communities shows that migrants everyday social practices 98

are informed by their localised experiences. Significant articulations, therefore, have 99

to be understood as local-to-local interactions (Smith 2001, Nez-Madrazo 2007). 100

Against this background, some authors consider translocality as the more general 101

concept (Hedberg & Do Carmo, 2012), and Freitag and von Oppen (2010a, p. 12) 102

aptly remark that transnationalism appears to be merely a special case of 103

translocalism. 104

103

Defining Translocality 106

Scrutinizing the growing literature on translocality, one is confronted with a multitude 107

of terms, revolving around notions of mobility, connectedness, networks, place, 108

locality and locales, flows, travel, transfer and circulatory knowledge. Some authors 109

seek conceptual coherence by synthesising these terms with reference to different 110

bodies of social theory (e.g. Bourdieu, Giddens) (e.g. Steinbrink 2009; Brickell and 111

Datta 2011; Greiner and Sakdapolrak 2012), while others use translocality as an 112

umbrella term to describe mobilities and multiple forms of spatial connectedness 113

(e.g. Grillo and Riccio 2004; Ma 2002). 114

Along these lines, Tenhunen (2011: 416, n.1), for example, defines translocality as 113

relations that extend beyond the village community. For Mandaville (2002, p. 204), 116

translocality is a space in which new forms of (post)national identity are constituted. 117

Similarly, Freitag and von Oppen (2010a, p. 5) use translocality as a descriptive tool 118

that refers to the sum of phenomena which result from a multitude of circulations and 119

AccepLed for publlcaLlon ln Ceography Compass

6

transfers. As such, they use this perspective to challenge the regional limitations 120

often implicit in area studies, and emphasise that the world is constituted through 121

processes that transgress boundaries on different scales, which results in the 122

production and reproduction of spatial differences. A translocal perspective enables 123

research into these processes in a more open and less linear way, and captures the 124

diverse and contradictory effects of interconnectedness between places, institutions 123

and actors. It overcomes the limitations of nationalist historiographies and facilitates 126

a non-Eurocentric understanding of global history as constituted by processes of 127

entanglement and interconnectedness (Freitag and von Oppen 2010a, p. 1). 128

Focusing on the multiple forms of mobility in contemporary China, Oakes and Schein 129

(2006b) deploy the term translocality to capture the implications of these dynamics. 130

Translocality is defined as being identified with more than one location (Oakes and 131

Schein 2006a, p. xiii). As such, the concept is used to simultaneously address 132

localities and mobilities within a holistic context. In a similar vein, authors such as 133

Brickell and Datta (2011a) use the concept to develop an agency-oriented approach 134

to these dynamics. They draw on Bourdieus concepts of habitus and social fields to 133

address the agents simultaneous situatedness across different locales (ibid, 4). 136

Through the notion of habitus, as Brickell and Datta (2011a, p. 13) highlight, the 137

translocal, where multi-scalar engagements of mobile and immobile actors are 138

formed by localized context and everyday practices, emerges at the same time as 139

the material, spatial and embodied. In translocal social fields, which are 140

characterised by uneven power relationships, mobile and immobile actors negotiate 141

and struggle over power and positions through the exchange of various capitals 142

which are valued differently across different scales (e.g. Kelly and Lusis 2006). This 143

view acknowledges what Massey (1991, p. 25) coined the power geometry of time- 144

AccepLed for publlcaLlon ln Ceography Compass

7

space compression, which draws attention to questions such as who moves and 143

who does not, how power relations are differentiated in flows and movements, and 146

how power and powerlessness are experienced simultaneously in different locations. 147

Hedberg and do Carmo (2012a) employ translocality to facilitate an understanding of 148

the relational dimensions of space created through mobility. Such an approach 149

overcomes the notion of container spaces and the dichotomy between here and 130

there, between rural and urban (Steinbrink 2009, Greiner 2010). Translocality 131

thus refers to the emergence of multidirectional and overlapping networks that 132

facilitate the circulation of people, resources, practices and ideas. Steinbrink (2009) 133

draws on Giddens Structuration Theory (Giddens 1984) to point out that translocal 134

networks are both structured by the actions of the people involved and at the same 133

time provide a structure for these very actions (see also Greiner and Sakdapolrak 136

2012). 137

With regard to scale, Verne (2012, p. 17) emphasises that translocality does not only 138

mean the addition of a translocal scale between the global and the local. This, she 139

argues, would merely reify the notion of hierarchical and clearly distinguishable 160

scales implicit in studies on transnationalism. Instead, a translocal perspective draws 161

on insights gained from research on scales (e.g. Smith 1995, Agnew 1997, Delaney 162

and Leitner 1997, Swyngedouw, 1997), which has shown, as Brown and Purcell 163

(2005, p. 609) summarizes, that socio-spatial scales are a) not given a priori, but 164

rather socially produced, b) simultaneously fluid and fixed and c) fundamentally 163

relational. In acknowledging these insights, the translocal perspective acknowledges 166

intermediary arrangements, fluidity and intermingling processes (Verne 2012, p. 17- 167

18) crucial for the understanding of the dynamic quality and effects of various socio- 168

spatialities (Amelina 2010). 169

AccepLed for publlcaLlon ln Ceography Compass

8

To sum up, authors use translocality to capture complex social-spatial interactions in 170

a holistic, actor-oriented and multi-dimensional understanding. The central idea of 171

translocality is aptly synthesised by Brickell and Datta (2011a, p. 3) as situatedness 172

during mobility. Authors engaging in the development of a translocal perspective 173

seek to integrate notions of fluidity and discontinuity associated with mobilities, 174

movements and flows on the one hand with notions of fixity, groundedness and 173

situatedness in particular settings on the other. Beyond this, however, what kind of 176

mobilities and movements are authors referring to when writing about translocality? 177

And how are the notions of situatedness and groundedness conceived? In the 178

following sections, we address these questions. 179

(Im)mobilities, movements and flows 180

Central to the notion of translocality is a holistic perspective on mobilities, movements 181

and flows, and the way in which these dynamics produce connectedness between 182

different scales. The majority of studies are primarily concerned with movements of 183

people. This concern is not restricted to transnational migration but also includes 184

various forms of internal migration as well as commuting and everyday movements 183

both within cities and between rural and urban areas (Hedberg and do Carmo 186

2012b). Many authors, however, are not concerned with mobile actors alone. They 187

also pay attention to those segments of the population that are considered immobile, 188

as they form a crucial dimension of connectedness (Brickell and Datta 2011a, Rau 189

2012). For Sun (2006, p. 240), this includes paying attention to those who talk, 190

speculate, and fantasize about certain places and to those who remember 191

experiences of familiar places. Such perspectives remind us that translocal spaces 192

are constantly co-produced by mobile and immobile populations. The often arduous 193

negotiation of physical co-presence by multiply located actors regarding, for example 194

AccepLed for publlcaLlon ln Ceography Compass

9

participation and non-participation in important social occasions, is a central aspect in 193

what Conradson and McKay (2007) describe as translocal subjectivities. 196

Although movement of people is of prime concern in many studies, this is but one 197

aspect of translocality. The concept also refers to material flows, such as those of 198

remittances (Long 2008) and goods (Verne 2012), and symbolic flows such as 199

movements of styles, ideas, images and symbols (Ma 2002, Lange and Bttner 2010, 200

Reetz 2010). One aspect of this latter dimension of translocality is the visualisation 201

and imagining of linkages between places, what Brickell and Datta (2011a, p. 18) 202

refer to as translocal imagination. 203

For an understanding of these connections, networks are of particular concern, as 204

they facilitate repeated flows of knowledge and communication, and of political, 203

cultural and economic activities between places (Hedberg and do Carmo 2012a). 206

Migrants and non-migrants are embedded in these networks, which are as much an 207

outcome of as a precondition for translocal practices (Steinbrink 2009). The position 208

of actors within these networks, in turn, influences the access those actors have to 209

various resources (Zoomers and Westen 2011). Research on migration, both 210

international (e.g. Singer and Massey (1998) for the case of undocumented border 211

crossing of Mexican migrants) and internal (e.g. Peth (2012) for the case of rural-rural 212

labour migration in Bangladesh) has vividly pointed out the role of networks in 213

overcoming mobility barriers and facilitating border transgression. At the same time 214

these studies also show the exclusionary power of networks for those actors who 213

have insufficient resources, be they financial, cultural or symbolic, to be able to 216

access them (e.g. Kothari 2002). Dissatisfied with conventional approaches to 217

networks, McFarlane (2009, p. 566) suggests a notion of translocal assemblages as 218

an alternative way to conceive of spatial connectedness as mediated by processes of 219

AccepLed for publlcaLlon ln Ceography Compass

10

disassemblage and reassemblage of history, labour, materiality and performance. 220

In a similar vein, Verne (2010, p. 23-31) departs from the shortcoming of a 221

conventional understanding of networks and proposes the metaphor of rhizome 222

(Deluze and Guattari 1976) as a means by which to grasp the complexity, dynamics 223

and relationality of translocal connectedness. 224

223

Places and locales 226

Common to most writings about translocality is an analytical focus on place as the 227

setting of grounded movements. This emphasis, however, appears to be driven by 228

diverse motives. While some authors (Freitag and von Oppen 2010) use translocality 229

to challenge notions of spatial boundedness implicit in area studies, others use it to 230

bring the local context back into deterritorialised conceptions of movement and flow 231

(Smith 2011). Translocality appears, then, as a concept serving both ends. It implies 232

a transgressing of locally bounded, fixed understandings of place and at the same 233

time emphasises the importance of places as nodes where flows that transcend 234

spatial scales converge. Referring to Doreen Masseys work on Power Geometries, 233

Brickell and Datta (2011) imagine translocal places as articulated moments in 236

networks of social relations (Massey 1999: 22). A translocal perspective focuses at 237

the same time on both what flows through places and what is in them (Verne 238

2010: 19). The relational nature of place as dynamic (i.e. not static) and constituted 239

through linkages to the outside (i.e. not bounded) (Massey 1991, p. 29) thus 240

appears to be commonly accepted in approaches to translocality, whereas 241

perspectives on the processes of the social and cultural production of place differ in 242

both scope and theoretical approach. 243

AccepLed for publlcaLlon ln Ceography Compass

11

For some authors a translocal perspective provides a vehicle to engage with 244

subjective and phenomenological dimensions of place-making. Situatedness during 243

mobility, according to Brickell and Datta (2011a), is embodied and experienced in 246

places. Places, as Oakes and Schein (2006b, p. 18) put it, are defined by subjective 247

meaning, history, and practices that transcend various spatial scales. While these 248

hermeneutically inspired approaches to translocality revolve around questions of 249

identities, narratives, imaginaries and symbolic representations (Freitag and von 230

Oppen 2010a, Hall and Datta 2010, Lambek 2011, Verne 2012), others expand their 231

conceptual scope to include the material and physical dimensions of place (McKay 232

2003). 233

Hedberg and do Carmo (2012a, p. 3), for example, state that a translocal approach 234

facilitates understanding of the role of mobility in connecting and transforming 233

places. In a similar vein, Greiner and Sakdapolrak (2012) stress the need to focus 236

on how scale-transcending practices materialise and become inscribed into the 237

physical environment, for example in land-use patterns, agricultural practices or built 238

environments. Building on concepts from Structuration Theory, they refer to locales 239

as the settings for social interaction. Processes of time-space distanciation 260

(Giddens 1984, p. 171), through mobility and movements, stretch these locales 261

beyond places, whereby they eventually become trans-locales through the 262

establishment of routine activities. These trans-locales provide the context and 263

setting for action that is extended and increasingly influenced by remote interaction. 264

The production of trans-locales implies a strong temporal dynamic, as they are 263

constructed and dismantled along what Giddens (1984, p. 132) terms time-space 266

trajectories. 267

AccepLed for publlcaLlon ln Ceography Compass

12

To sum up, whatever the specific theoretical conceptions of place or locales may be, 268

they are always conceived of as important arenas of scale-transcending interaction. 269

Translocal approaches, therefore, usually acknowledge a primacy of place (Casey 270

1996) while at the same time they break with essentialising notions of spatially 271

bounded territorial units. 272

273

Empirical application of translocality 274

Translocal approaches are applied to enhance the understanding of various 273

phenomena related to the production and re-production of social spatial 276

configurations, covering such issues as international and internal migration, identity 277

formation, media-use and knowledge transfer as well as local development 278

processes. This list is far from being comprehensive, but it provides an overview of 279

translocalitys range of potential applications. 280

A great majority of studies focus on the multifaceted dimensions of international 281

migration (Peleikis 2003, Velayutham and Wise 2005, Sinatti 2006, Nez-Madrazo 282

2007, Chacko 2011, Leung 2011). Increasingly, however, studies also focus on the 283

highly dynamic rural-urban interactions that constitute translocal fields within national 284

boundaries. In southern Africa, where many internal migration patterns are a product 283

of the political system of Apartheid, these patterns have largely persisted into the 286

post-1990s era. Steinbrink (2009) uses a translocal approach to describe how such 287

patterns of rural-urban interaction impact on the ability of households to cope with 288

and adapt to livelihood risks, and how those patterns are sustained. Greiner (2011) 289

reports from Namibia, a country equally affected by apartheid, about how 290

remittances, part-time pastoralism and other migration-related patterns of 291

AccepLed for publlcaLlon ln Ceography Compass

13

translocality induce processes of socio-economic stratification. In a similar vein, Long 292

(2008), Steel, Winters and Sosa (2011) and McKay (2003) use a translocal approach 293

to elucidate the social impact of rural-urban migration and remittances in Peru, 294

Nicaragua and the Philippines respectively. 293

The analysis of translocal rural spaces, however, is not limited to areas of the Global 296

South. The contributions in a recently published volume on Translocal Ruralism by 297

Hedberg and do Carmo (2012a) are concerned with translocal phenomena in 298

Europe. The editors direct attention to various forms of migration (internal and 299

international) and mobility (e.g. daily commuting) in order to demonstrate that 300

geographically peripheral regions of Europe are engaged in a constant process of 301

functional reconfiguration. Here, translocal approaches are applied to challenge 302

notions of stagnation and isolation often associated with rural spaces (Do Carmo and 303

Santos 2012, Guran-Nica and Sofer 2012, Papadopoulos 2012, Rau 2012). 304

Translocal social spaces are, however, not only produced by refugees (Stenbacka 303

2012) and (labour) migrants (Papadopoulos 2012), but also by musicians (Ma 2002), 306

communities of ballroom dancers (Marion 2005) and amateur football players 307

(Steinbrink 2010), amongst others. 308

The volume Translocal Geographies. Spaces, Places and Connections edited by 309

Brickell and Datta (2011a) uses scale as the main structuring dimension to illustrate 310

the multiplicity of translocal affiliations. The contributions present experiences of 311

multi-scalar and multi-sited translocal geographies at the scale of home and family 312

(Brickell 2011, Tan and Yeoh 2011, Hatfield 2011) and neighbourhoods (Centner 313

2011, Datta 2011, Wise 2011) as well as that of the city (Chako 2011, Christou 2011, 314

Page 2011). As Brickell and Datta (2001a, p. 19-20) summarise, the volume 313

highlights how the local and local-to-local connections exist across a variety of scales 316

AccepLed for publlcaLlon ln Ceography Compass

14

and points to the importance of considering the material and embodied practices of 317

migrants for gaining an understanding of translocality. 318

Another area of focus of translocal research is that of identity in the context of 319

intensifying mobility (de Lima 2012, Stenbacka 2012). Using Cameroon and 320

Tanzania as examples, Page (2011) shows how globally operating home-town 321

associations become differentially enmeshed with localised identity politics in the 322

migrant sending areas. The volume Translocal China, edited by Oakes and Schein 323

(2006b), explicitly addresses such multifaceted questions of identity against the 324

background of contemporary China. They point out that people and institutions have 323

become translocal in the recent era of reform and rapid socio-economic 326

transformation. While the subject of the movement of people is often taken up in 327

addressing questions of identity (Chongyi and Changzhi 2006, Schein 2006, Sun 328

2006, Greiner 2010), some authors apply a translocal approach to expand the focus 329

beyond the topic of migration. 330

As such, translocality is also applied to study the use of media and the circulation of 331

knowledge and ideas in globally operating networks. Focusing on the spatial 332

organisation of high-tech innovation in Germany, Lange and Bttner (2010), use a 333

translocal approach to map out the possibilities for and restrictions on translocal 334

knowledge-transfers which result in differential spatial knowledge formations. The 333

flow of information, ideas and opinions through the internet, and its influence on 336

identity formation, is taken up by Gan (2006), who shows how young mothers in 337

China use online parenting forums to construct and negotiate their new identities as 338

mothers alongside their identities as career women. The role of the internet in 339

producing translocal relations and imageries is also reflected by Uimonens (2009) 340

study on art college students in Tanzania. The changing patterns of translocal 341

AccepLed for publlcaLlon ln Ceography Compass

13

communication facilitated by mobile phones, and their impact on political practices 342

(protests and riots), is illustrated in a case study by Tenhunen (2011) from West 343

Bengal. Analysing poems as a symbolic and material expression of translocality, 344

Suns (2010) study on migrant workers in Chinas industrial south reveals how 343

movements by this group are marked by a sense of alienation, displacement and 346

disenchantment. The exchange of symbol and images among transnationally 347

operating South Asian Muslim groups is described by Reetz (2010). He employs a 348

translocal perspective to illustrate the production of alternate globalities that position 349

themselves against Western-dominated and economy-centred activities. 330

Another area of investigation explores the implications of translocality for 331

development (Helvoirt 2011, Noorloos 2011). In the article Translocal Development, 332

Development Corridors and Development Chains by Zoomers and Westen (2011), in 333

a special issue of the International Development Planning Review, translocality is 334

applied to redefine notions of locally bounded development. The contributions in the 333

Review highlight how local-to-local connectedness produces both opportunities for 336

and constraints upon people in their struggle for better livelihoods. The possibilites 337

available for and difficulties encountered by development cooperation below the level 338

of the state, such as formalised municipal partnerships (Bontenbal and Lindert 2011) 339

or development projects of migrants associations (Grillo and Riccio 2004, Page and 360

Mercer 2012), are addressed by several authors from a translocal perspective. 361

Kaags (2011) case study from Chad, for example, examines the work of Islamic 362

NGOs from the Arab world in Africa. While rather limited in financial volume and 363

economic impact, the study highlights the nevertheless important political and moral 364

implications that result from the NGOs work in connecting the umma (Islamic 363

community). Pointing to the fact that development is often related to practices of 366

AccepLed for publlcaLlon ln Ceography Compass

16

accumulation through extraction, expulsion and marginalisation of local populations, 367

authors such as Banerjee (2011) and McFarlane (2009) highlight the emancipatory 368

potential of translocality. The exchange of ideas, knowledge, practices, materials and 369

resources across places, they argue, is a resource that enables local social 370

movements to resist or challenge development paths or change them in their favour. 371

Similarly, using a case study from inhabitants of a squatter settlement in Lisbon, 372

Portugal Horta (2002) illustrates how translocal forms of migrants grassroots 373

organizations have become crucial in their practices of collective mobilization to 374

negotiate their interests. 373

376

Conclusion: Translocalism an approach in its own right 377

Translocality has been applied as a way to comprehend the tension between mobility 378

and locality and to enhance understanding of this relationship, which characterises 379

an increasing number of socio-spatial dynamics. The approach builds on insights 380

from the longer-established research tradition of transnationalism, but seeks to 381

overcome the latters limited focus on the nation state. This analytical expansion, we 382

have argued, was both necessary and overdue. Writings on translocality direct 383

attention to various forms of mobility beyond the movement of people. Building on a 384

relational notion of place, these writings place a strong emphasis on the micro level 383

and local-to-local dynamics to explain socio-spatial phenomena. 386

Translocal approaches exhibit several commonalities with research on grounded 387

transnationalism. Although many authors do not differentiate tranlocalism from 388

transnationalism, let alone designate it as an analytical concept in its own right, we 389

nevertheless consider that the approach warrants consideration as an emerging 390

AccepLed for publlcaLlon ln Ceography Compass

17

research concept. Based on our review of existing concepts and empirical 391

applications, we argue that translocality has the potential to address important issues 392

in socio-spatial research. We conclude this review by outlining some of these areas. 393

Firstly, translocality can serve as a fruitful starting point from which to challenge 394

dichotomous geographical conceptions (Agnew 2005), such as space and place, 393

rural and urban, core and periphery. 396

Secondly, the actor-oriented focus on the social production of translocality enhances 397

a more explicit discussion of the temporal dynamics, path dependencies and time- 398

space interconnections of socio-spatial dynamics. The concept thereby offers a more 399

nuanced perspective on how these processes are socially differentiated, and is 400

sensitive to the role of power in relation to flows and movements (Massey 1991, p. 401

25f). 402

Thirdly, the shift away from a primary concern with the nation state directs attention 403

to alternative historiographies of globalization. 404

Fourthly, translocality emphasises significant spatial scales beyond the national 403

entities and their specific non-hierarchic interactions and configurations. In particular, 406

it highlights the importance of networked places, which are, in Doreen Masseys 407

words (1991: 28), constructed on a far larger scale than what we happen to define 408

for that moment as place. 409

Fifthly, translocality facilitates research on mobilities beyond human migration. By 410

addressing flows and circulations of ideas, symbols, knowledge, etc., it offers a 411

stimulating perspective from which to engage with subjects such as the impact of a 412

globalising world on non-migrants, and the co-production of connectedness by 413

mobile and immobile populations. 414

AccepLed for publlcaLlon ln Ceography Compass

18

Finally, by placing an explicit emphasis on local conditions, translocality draws 413

attention to transformations of the physical and natural environment (e.g. farming 416

systems, urban areas, riparian zones). In so doing, translocal research can engage in 417

the discussion on global environmental change and strengthen the importance of the 418

mobility of people, concepts and resources within the debate. To conclude, this 419

review demonstrates that translocality is a dynamic and emerging field of research 420

which is both a suitable and a timely means by which to address socio-spatial 421

dynamics in an increasingly mobile world. 422

AccepLed for publlcaLlon ln Ceography Compass

19

References 423

Adepo[u, A. (2006). lnLernal and lnLernaLlonal mlgraLlon wlLhln Afrlca. ln: kok, ., Celderblom, u., 424

Cucho, !. C. and van Zyl !., (eds), !"#$%&"'( "( *'+&, %(- *'+&,.$( /0$"1%. Cape 1own: PS8C 423

ress, pp. 26-43. 426

Agnew, !. (2003). Space:lace. ln: Cloke, . and !ohnsLon, 8., (eds), *2%1.3 '0 4.'#$%2,"1%5 6,'+#,&7 427

8.1'(3&$+1&"(# 9+:%( 4.'#$%2,".3 ;"(%$".3. London: Sage pp. 81-96. 428

Amellna, A. (2010). Scallng lnequallLles!? Some SLeps Lowards Lhe Soclal lnequallLy Analysls ln 429

MlgraLlon 8esearch beyond Lhe lramework of Lhe naLlon SLaLe. 8lelefeld. 430

Appadural, A. (2003). !'-.$("&< %& =%$#.> ?+5&+$%5 8":.(3"'(3 '0 45'@%5"A%&"'(. Mlnneapolls, London: 431

unlverslLy of MlnnesoLa ress. 432

ArgenLl, n., and 8schenLhaler, u. (2006). lnLroducLlon: 8eLween Cameroon and Cuba: ?ouLh, slave 433

Lrades and Lranslocal memoryscapes. *'1"%5 /(&,$'2'5'#< BC(01), pp. 33-47. 434

8aner[ee, S. 8. (2011). volces of Lhe Coverned: Lowards a Lheory of Lhe Lranslocal. D$#%("A%&"'( 433

BE(3), pp. 323-344. 436

8asch, L., Cllck Schlller, n., and SzanLon 8lanc C. (1993). F%&"'(3 G(@'+(-> 6$%(3(%&"'(%5 H$'I.1&3J 437

H'3&1'5'("%5 H$.-"1%:.(&3J %(- 8.&.$$"&'$"%5"A.- F%&"'(K*&%&.3. 8asel: Cordon and 8reach 438

ubllshers. 439

8enneLL, A., and eLerson, 8. A. (eds) (2004). !+3"1 31.(.37 5'1%5J &$%(35'1%5 L M"$&+%5. nashvllle: 440

vanderbllL unlverslLy ress. 441

8onLenbal, M., and LlnderL, . v. (2011). Munlclpal parLnershlps for local developmenL ln Lhe Clobal 442

SouLh? undersLandlng connecLlons and conLexL from a Lranslocal perspecLlve. N(&.$(%&"'(%5 443

8.M.5'2:.(& H5%(("(# O.M".P QQ(4), pp. 443-461. 444

8rlckell, k. (2011). 1ranslocal Ceographles of home" ln slem reap, Cambodla. ln: 8rlckell, k. and A. 443

uaLLa (eds), 6$%(35'1%5 4.'#$%2,".37 *2%1.3J H5%1.3J ?'((.1&"'(3. larnham: AshgaLe, pp. 23- 446

38. 447

8rlckell, k., and uaLLa, A. (2011a). lnLroducLlon: 1ranslocal Ceographles. ln: 8rlckell, k. and uaLLa, A., 448

(eds), 6$%(35'1%5 4.'#$%2,".3 *2%1.3J H5%1.3J ?'((.1&"'(3. larnham: AshgaLe, pp. 3-20. 449

- (eds) (2011b). 6$%(35'1%5 4.'#$%2,".3> *2%1.3J H5%1.3J ?'((.1&"'(3. larnham: AshgaLe. 430

Casey, L. S. (1996). Pow Lo CeL from Space Lo lace ln a lalrly ShorL SLreLch of 1lme: 431

henomenologlcal rolegomena. ln: leld, S. and 8asso, k. P., (eds), *.(3.3 '0 H5%1.. SanLa le: 432

1he School of Amerlcan 8esearch, pp. 13-32. 433

CasLells, M. (2000). 6,. N(0'$:%&"'( /#.7 R1'(':<J *'1".&< %(- ?+5&+$.. Cxford: 8lackwell. 434

CasLree, n. (2004). ulfferenLlal geographles: place, lndlgenous rlghLs and 'local' resources. H'5"&"1%5 433

4.'#$%2,< SQ, pp. 133-167. 436

AccepLed for publlcaLlon ln Ceography Compass

20

CenLner, 8. (2011). Ways ouL of crlsls ln 8uenos Alres: 1ranslocal landscapes and Lhe acLlvaLlon of 437

Moblle resources. ln: 8rlckell, k. and uaLLa, A., (eds), 6$%(35'1%5 4.'#$%2,".37 *2%1.3J H5%1.3J 438

?'((.1&"'(3. larnham: AshgaLe, pp. 109-124. 439

Chacko, L. (2011). 1ranslocallLy ln WashlngLon, u.C. and Addls Ababa: Spaces and Llnkages of Lhe 460

LLhloplan ulaspora ln 1wo CaplLal ClLles. ln: 8rlckell, k. and uaLLa, A., (eds), 6$%(35'1%5 461

4.'#$%2,".3 *2%1.3J H5%1.3J ?'((.1&"'(3. larnham: AshgaLe, pp. 163-178. 462

ChrlsLou, A. (2011). 1ranslocal spaLlal Ceographles. MulLl-slLed LncounLers of Creek MlgranLs ln 463

ALhens, 8erlln, and new york. ln: 8rlckell, k. and uaLLa, A. (eds), 6$%(35'1%5 4.'#$%2,".37 464

*2%1.3J H5%1.3J ?'((.1&"'(3. larnham: AshgaLe, pp. 143-162 463

Chongyl, l., and Changzhl, Z. (2006). Cpenness, change, and LranslocallLy. new mlgranLs' 466

ldenLlflcaLlon wlLh Palnan. ln: Cakes, 1. and Scheln, L., (eds), 6$%(35'1%5 ?,"(%> ="(T%#.3J 467

N-.(&"&".3J %(- &,. $.":%#"(# '0 32%1.> new ?ork: 8ouLledge, pp. 74-92. 468

Conradson, u., and Mckay, u. (2007). 1ranslocal Sub[ecLlvlLles: MoblllLy, ConnecLlon, LmoLlon. 469

!'@"5"&".3 S(2), pp. 167-174. 470

uaLLa, A. (2011). 1ranslocal Ceographles of larnham. 8elonglng and oLherness" among ollsh 471

MlgranLs afLer 2004. ln: 8rlckell, k. and uaLLa, A. (eds.), 6$%(35'1%5 4.'#$%2,".37 *2%1.3J 472

H5%1.3J ?'((.1&"'(3. Lodon: AshgaLe, pp. 73-92. 473

ue Llma, . (2012). 8oundary crosslng. MlgraLlon, belonglng/'unbelonglng' ln rural ScoLland. ln: 474

Pedberg C. and uo Carmo M. 8., (eds) ), 6$%(35'1%5 O+$%5"3: !'@"5"&< %(- ?'((.1&"M"&< "( 473

R+$'2.%( O+$%5 *2%1.3. Peldelberg: Sprlnger, pp. 203-218. 476

uelaney, u. and LelLner, P. (1997): 1he pollLlcal consLrucLlon of scale. H'5"&"1%5 4.'#$%2,< BU (2), pp. 477

93-97. 478

uLLLuZL, C. and CuA11A8l, l. (1976). 8hlzome. MlnulL: arls. 479

uo Carmo, M. 8., and SanLos, S. (2012). 8eLween marglnallsaLlon and urbanlsaLlon. moblllLles and 480

soclal change ln SouLhern orLugal. ln: Pedberg C. and uo Carmo M. 8., (eds) ), 6$%(35'1%5 481

O+$%5"3: !'@"5"&< %(- ?'((.1&"M"&< "( R+$'2.%( O+$%5 *2%1.3. Peldelberg: Sprlnger, pp. 13-34. 482

Lscobar, A. (2001). CulLure slLs ln places: reflecLlons on globallsm and subalLern sLraLegles of 483

locallzaLlon. H'5"&"1%5 4.'#$%2,< SV, pp. 139-174. 484

lalsL, 1., and 8elsenauer, L. (2009). lnLroducLlon: MlgraLlon(s) and uevelopmenL(s): 1ransformaLlon 483

of aradlgms, CrganlsaLlons and Cender Crders. *'1"'5'#+3 WX(1), pp. 1-16. 486

leaLhersLone, u. (2011). Cn assemblage and arLlculaLlon. /$.% CQ(2), pp. 139-142. 487

lrelLag, u., and von Cppen, A. (2010a). lnLroducLlon. "1ranslocallLy": An Approach Lo ConnecLlon and 488

1ransfer ln Area SLudles. ln: lrelLag, u. and von Cppen, A., (eds), 6$%(35'1%5"&<7 6,. *&+-< '0 489

45'@%5"3"(# H$'1.33.3 0$': % *'+&,.$( H.$32.1&"M.. Lelden: 8rlll, pp. 490

- (eds) (2010b). 6$%(35'1%5"&<7 6,. *&+-< '0 45'@%5"3"(# H$'1.33.3 0$': % *'+&,.$( H.$32.1&"M.. 491

Lelden: 8rlll. 492

AccepLed for publlcaLlon ln Ceography Compass

21

Can, W. (2006). "neL-moms" - a new place and a new ldenLlLy. ln: Cakes, 1. and Scheln, L., (eds), 493

6$%(35'1%5 ?,"(% ="(T%#.3J N-.(&"&".3J %(- &,. $.":%#"(# '0 32%1.. new ?ork: 8ouLledge, pp. 494

133-163. 493

Ceschlere 2009 1he erlls of 8elonglng. AuLochLhony, ClLlzenshlp, and Lxcluslon ln Afrlca & Lurope 496

Chlcago, unlverslLy of Chlcago ress. 497

Clddens, A. (1984). 6,. ?'(3&"&+&"'( '0 *'1".&<> D+&5"(. '0 &,. 6,.'$< '0 *&$+1&+$%&"'(. Cambrldge: 498

ollLy ress. 499

CoLLowlk, v. (2010). 1ransnaLlonal, 1ranslocal, 1ransculLural: Some 8emarks on Lhe 8elaLlons 300

beLween Plndu-8allnese and LLhnlc Chlnese ln 8all. *'I'+$(7 Y'+$(%5 '0 *'1"%5 N33+.3 "( 301

*'+&,.%3& /3"% SW(2), pp. 178-212. 302

CupLa A., and lerguson !. (1992). 8eyond "CulLure": Space, ldenLlLy, and Lhe ollLlcs of ulfference. 303

?+5&+$%5 /(&,$'2'5'#< 7(1), pp. 6-23. 304

Crelner, C. (2010). aLLerns of 1ranslocallLy: MlgraLlon, Llvellhoods and ldenLlLy ln norLhwesL 303

namlbla. *'1"'5'#+3 UVZS[, pp. 131-161. 306

- (2011). 1ranslocal neLworks and SLraLlflcaLlon ln namlbla. /0$"1%7 Y'+$(%5 '0 &,. N(&.$(%&"'(%5 307

/0$"1%( N(3&"&+&. EBZC[, pp. 606-627. 308

Crelner C., and Sakdapolrak . (2012) 8ural-urban mlgraLlon, agrarlan change, and Lhe envlronmenL 309

ln kenya: a crlLlcal revlew of Lhe llLeraLure. H'2+5%&"'( L R(M"$'(:.(&J pp. 1-30 (onllne flrsL) 310

Crlllo, 8., and 8lcclo, 8. (2004). 1ranslocal developmenL: lLaly-Senegal. H'2+5%&"'(J *2%1. %(- H5%1. 311

BV(2), pp. 99-111. 312

Cuarnlzo, L. L., and SmlLh, M. . (1998). 1he LocaLlons of 1ransnaLlonallsm. ln: SmlLh M. . and 313

Cuarnlzo L. L., (eds), 6$%(3(%&"'(%5"3: 0$': ;.5'P. new 8runswlck, London: 1ransacLlon 314

ubllshers, pp. 3-34. 313

Curan-nlca, L., and Sofer, M. (2012). MlgraLlon dynamlcs ln 8omanla and Leh counLer-urbanlsaLlon 316

process. A case sLudy of 8ucharesL's rural urban frlnge. ln: Pedberg C. and uo Carmo M. 8., 317

(eds) ), 6$%(35'1%5 O+$%5"3: !'@"5"&< %(- ?'((.1&"M"&< "( R+$'2.%( O+$%5 *2%1.3. Peldelberg: 318

Sprlnger, pp. 87-102. 319

Pall, S., and uaLLa, A. (2010). 1he Lranslocal sLreeL: Shop slgns and local mulLl-culLure along Lhe 320

WalworLh 8oad, souLh London. ?"&<J ?+5&+$. %(- *'1".&< B(2), pp. 69-77. 321

Pannerz u. (1996). 6$%(3(%&"'(%5 ?'((.1&"'(37 ?+5&+$.J H.'25.J H5%1.3. London: 8ouLledge. 322

PaLfleld, M. L. (2011). 8rlLlsh lamllles Movlng Pome: 1ranslocal Ceographles of 8eLurn MlgraLlon 323

from Slngapore. ln: 8rlckell, k. and uaLLa, A. (eds), 6$%(35'1%5 4.'#$%2,".37 *2%1.3J H5%1.3J 324

?'((.1&"'(3. Lodon: AshgaLe, pp. 33-70. 323

Pedberg, C., and do Carmo, 8. M. (2012a). 1ranslocal 8urallsm: MoblllLy and ConnecLlvlLy ln 326

Luropean 8ural Spaces. ln: Pedberg, C. and do Carmo, 8. M., (eds), 6$%(35'1%5 O+$%5"3: 327

!'@"5"&< %(- ?'((.1&"M"&< "( R+$'2.%( O+$%5 *2%1.3. uordrechL: Sprlnger, pp. 1-9. 328

AccepLed for publlcaLlon ln Ceography Compass

22

- (eds) (2012b). 6$%(35'1%5 O+$%5"3:7 !'@"5"&< %(- ?'((.1&"M"&< "( R+$'2.%( O+$%5 *2%1.3. uordrechL: 329

Sprlnger. 330

PelvolrL, 8. v. (2011). CloballsaLlon and reglonal developmenL chalns: Lhe lmpacL of MeLro Cebu on 331

reglonal developmenL ln Lhe CenLral vlsayas, hlllpplnes. N(&.$(%&"'(%5 8.M.5'2:.(& H5%(("(# 332

O.M".P QQ(4), pp. 389-407. 333

PorLa, A. . 8. (2002). 6$%(3(%&"'(%5 F.&P'$T3 %(- &,. 5'1%5 2'5"&"13 '0 :"#$%(&3 #$%33$''&3 334

'$#%("A%&"'( "( 2'3&K1'5'("%5 H'$&+#%5. 1ransnaLlonal CommunlLles rogramme Worklng 333

aper Serles no. W1C 02-03. Cxford. 336

kaag, M. (2011). ConnecLlng Lo Lhe +::% Lhrough lslamlc rellef: LransnaLlonal lslamlc nCCs ln Chad. 337

N(&.$(%&"'(%5 8.M.5'2:.(& H5%(("(# O.M".P QQ(4), pp. 463-474. 338

kelly, . & 1. Lusls (2006): MlgraLlon and Lhe LransnaLlonal hablLus: evldence from Canada and Lhe 339

hlllpplnes. R(M"$'(:.(& %(- H5%(("(# / 38, pp. 831-847. 340

kokoL, W. (2007). CulLure and Space - anLhropologlcal approaches. LLhnoscrlpLs 9, pp. 10-23. 341

hLLp://www.eLhnologle.unl-hamburg.de/de/pdfs/LLhnoscrlpLs_pdf/es_9_1_arLlkel1.pdf (lasL 342

accessed 20 uecember 2012). 343

koLharl, u. (2002). MlgraLlon and Chronlc overLy. ManchesLer: lnsLlLuLe for uevelopmenL ollcy and 344

ManagemenL, unlverslLy of ManchesLer. 343

Lambek M. (2011). O.05.1&"'(3 '( ,.$:.(.+&"13 %(- &$%(35'1%5"&<. ZMC Worklng apers no. 4. : 346

8erlln: ZenLrum Moderner CrlenL. 347

Lange, 8., and 8uLLner k. (2010). SpaLlallzaLlon aLLerns of 1ranslocal knowledge neLworks: 348

ConcepLual undersLandlngs and Lmplrlcal Lvldences of Lrlangen and lrankfurL/Cder. 349

R+$'2.%( H5%(("(# *&+-".3 BE(6), pp. 989-1018. 330

Leung, M. (2011). Cf corrldors and chalns: Lranslocal developmenLal lmpacLs of academlc moblllLy 331

beLween Chlna and Cermany. N(&.$(%&"'(%5 8.M.5'2:.(& H5%(("(# O.M".P QQ(4), pp. 473- 332

489. 333

Ley, u. (2004). 1ransnaLlonal spaces and everyday llves. 6$%(3%1&"'(3 '0 &,. N(3&"&+&. '0 ;$"&"3, 334

4.'#$%2,.$3 SX, pp. 131-164. 333

Long, n. (2008). 1ranslocal Llvellhoods, neLworks of lamlly and CommunlLy, and 8emlLLances ln 336

CenLral eru. ln: lom and Ssrc, (eds). Ceneva, new ?ork: lnLernaLlonal CrganlzaLlon for 337

MlgraLlon and Soclal Sclence 8esearch Councll, pp. 37-68. 338

Ma, L. k.-w. (2002). 1ranslocal spaLlallLy. N(&.$(%&"'(%5 Y'+$(%5 '0 ?+5&+$%5 *&+-".3 W, pp. 131-132. 339

Mandavllle, . (2002). 8eadlng Lhe sLaLe from elsewhere: Lowards an anLhropology of Lhe 360

posLnaLlonal. O.M".P '0 N(&.$(%&"'(%5 *&+-".3 SE(01), pp. 199-207. 361

Marlon, !. S. (2003). "Where" ls "1here"?: 1owards a 1ranslocal AnLhropology. /(&,$'2'5'#< F.P3 362

CU(3), pp. 18-18. 363

Mclarlane, C. (2009). 1ranslocal assemblages: Space, power and soclal movemenLs. 4.'0'$+: CV(4), 364

pp. 361-367. 363

AccepLed for publlcaLlon ln Ceography Compass

23

Mckay, u. (2003). CulLlvaLlng new Local luLures: 8emlLLance Lconomles and Land-use aLLerns ln 366

lfugao, hlllpplnes. !ournal of SouLheasL Aslan SLudles 34(2), pp. 283-306. 367

Massey u. (1991). A Clobal Sense of lace. Marxlsm 1oday, pp. 24-29. 368

- (1999). ower-CeomeLrles and Lhe ollLlcs of Space and 1lme. PeLLner LecLure 1998, ueparLmenL 369

of Ceography, unlverslLy of Peldelberg. 370

noorloos, l. v. (2011). A LransnaLlonal neLworked space: Lraclng resldenLlal Lourlsm and lLs mulLl- 371

local lmpllcaLlons ln CosLa 8lca. N(&.$(%&"'(%5 8.M.5'2:.(& H5%(("(# O.M".P QQ(4), pp. 429- 372

444. 373

nunez-Madrazo, C. (2007). Llvlng 'Pere and 1here': new MlgraLlon of 1ranslocal Workers from 374

veracruz Lo Lhe SouLheasLern unlLed SLaLes. /(&,$'2'5'#< '0 \'$T O.M".P SE(3), pp. 1-6. 373

Cakes, 1., and Scheln, L. (2006a). reface. ln: Cakes, 1. and Scheln, L., (eds), 6$%(35'1%5 ?,"(% 376

="(T%#.3J N-.(&"&".3J %(- &,. $.":%#"(# '0 32%1.. London: 8ouLledge, pp. xll-xlll. 377

- (eds) (2006b). 6$%(35'1%5 ?,"(%> ="(T%#.3J N-.(&"&".3J %(- &,. $.":%#"(# '0 32%1.. London: 378

8ouLledge. 379

Clwlg, k. l. (1997). CulLural slLes. SusLalnlng a home ln a deLerrlLorlallzed world. ln: Clwlg, k. l. and 380

PasLrup, k., (eds), *"&"(# ?+5&+$. 6,. 3,"0&"(# %(&,$'2'5'#"1%5 '@I.1&. London: 8ouLledge, pp. 381

17-38. 382

age, 8. (2011). lear of Small ulsLances: Pome AssoclaLlons ln uouala, uar es Salaam and London. ln: 383

8rlckell, k. and uaLLa, A., (eds), 6$%(35'1%5 4.'#$%2,".3 *2%1.3J H5%1.3J ?'((.1&"'(3. 384

larnham: AshgaLe, pp. 127-144. 383

age, 8., and Mercer, C. (2012). Why do people do sLuff? 8econcepLuallzlng remlLLance behavlour ln 386

dlaspora-developmenL research and pollcy. H$'#$.33 "( 8.M.5'2:.(& *&+-".3 BS, pp. 1-18. 387

apadopoulos, A. C. (2012). 1ransnaLlonal lmmlgraLlon ln rural Creece. Analyslng Lhe dlfferenL 388

moblllLles of Albanlan lmmlgranLs. ln: Pedberg, C. and uo Carmo, M. 8., (eds), 6$%(35'1%5 389

O+$%5"3: !'@"5"&< %(- ?'((.1&"M"&< "( R+$'2.%( O+$%5 *2%1.3. Peldelberg: Sprlnger, pp. 163- 390

184. 391

elelkls, A. (2003). =.@%(.3. "( !'&"'(> 4.(-.$ %(- &,. !%T"(# '0 % 6$%(35'1%5 ]"55%#.. 8lelefeld: 392

Lranscrlp. 393

eLh, S. A. (2012). MlgraLlonspfade und ArbelLsraume ln 8angladesch - 1ranslokale Lebensslcherung 394

ln elner slch wandelnden (um)WelL. ueparLmenL of Ceography: 8helnlsche lrledrlch- 393

Wllhelms-unlverslLaL 8onn. unpubllshed MasLer 1hesls. 396

8au, P. (2012). 1he Lles LhaL blnd? SpaLlal (lmmoblllLles) and Lhe LransformaLlon of 8ural-urban 397

ConnecLlons. ln: Pedberg, C. and uo Carmo, M. 8., (eds), 6$%(35'1%5 O+$%5"3: !'@"5"&< %(- 398

?'((.1&"M"&< "( R+$'2.%( O+$%5 *2%1.3. Peldelberg: Sprlnger, pp. 33-33. 399

8eeLz, u. (2010). 'AlLernaLe' CloballLles? Cn Lhe CulLures and lormaLs of 1ransnaLlonal Musllm 600

neLworks from SouLh Asla. ln: lrelLag, u. and von Cppen, A., (eds), 6$%(35'1%5"&<7 6,. *&+-< 601

'0 45'@%5"3"(# H$'1.33.3 0$': % *'+&,.$( H.$32.1&"M.. Lelden: 8rlll, pp. 293-334. 602

AccepLed for publlcaLlon ln Ceography Compass

24

Scheln, (2006). negoLlaLlng scale. Mlao women aL a dlsLance. ln: Cakes, 1. and Scheln, L., (eds), 603

6$%(35'1%5 ?,"(% ="(T%#.3J N-.(&"&".3J %(- &,. $.":%#"(# '0 32%1.. new ?ork: 8ouLledge, pp. 604

213-237. 603

SlnaLLl, C. (2006). ulasporlc CosmopollLanlsm and ConservaLlve 1ranslocallsm: narraLlves of naLlon 606

Among Senegalese MlgranLs ln lLaly. *&+-".3 "( R&,("1"&< %(- F%&"'(%5"3: U(3), pp. 30-30. 607

Slnger, A. and Massey, u. S. (1998). 1he Soclal rocess of undocumenLed 8order Crosslng among 608

Mexlcan. N(&.$(%&"'(%5 !"#$%&"'( O.M".P QS (3), 361-392. 609

SmlLh, M. . (2001). 6$%(3(%&"'(%5 G$@%("3:> ='1%&"(# 45'@%5"A%&"'(. Malden, MassachuseLLs 610

- (2011). 1ranslocallLy: A CrlLlcal 8eflecLlon. ln: 8rlckell, k. and uaLLa, A., (eds), 6$%(35'1%5 611

4.'#$%2,".3 *2%1.3J H5%1.3J ?'((.1&"'(3. larnham: AshgaLe, pp. 181-198. 612

SLeel, C., WlnLers, n., and Sosa, C. (2011). MoblllLy, Lranslocal developmenL and Lhe shaplng of 613

developmenL corrldors ln (seml-)rural nlcaragua. N(&.$(%&"'(%5 8.M.5'2:.(& H5%(("(# O.M".P 614

QQ(4), pp. 409-428. 613

SLelnbrlnk, M. (2009). =.@.( AP"31,.( *&%-& +(- =%(-> !"#$%&"'(J 6$%(35'T%5"&^& +(- ].$P+(-@%$T."& 616

"( *_-%0$"T%. Wlesbaden: vS verlag fur SozlalwlssenschafLen. 617

- (2010). 1he 8ole of AmaLeur looLball ln Clrcular MlgraLlon SysLems ln SouLh Afrlca. /0$"1% 618

*2.1&$+: CW(2), pp. 33-60. 619

SLenbacka, S. (2012). "1he rural" lnLervenlng ln Lhe llves of lnLernal and lnLernaLlonal mlgranLs. 620

MlgranLs, blographles and Lranslocal pracLlces. ln: Pedberg, C. and uo Carmo, M. 8., (eds), 621

6$%(35'1%5 O+$%5"3: !'@"5"&< %(- ?'((.1&"M"&< "( R+$'2.%( O+$%5 *2%1.3. Peldelberg: 622

Sprlnger, pp. 33-72. 623

Sun, W. (2006). 1he leavlng of Anhul. 1he souLhward [ourney Loward Lhe knowledge class. ln: Cakes, 624

1. and Scheln, L., (eds) , 6$%(35'1%5 ?,"(% ="(T%#.3J N-.(&"&".3J %(- &,. $.":%#"(# '0 32%1.. 623

new ?ork: 8ouLledge, pp. 238-262. 626

- (2010). narraLlng 1ranslocallLy: uagong oeLry and Lhe SubalLern lmaglnaLlon. MoblllLles 3(3), pp. 627

291-309. 628

Swyngedouw, L., 1997b. nelLher global nor local: glocallzaLlon and Lhe pollLlcs of scale. ln: Cox, k. 629

(Ld.), Spaces of CloballzaLlon. Cullford ress, new ?ork, pp. 137-166. 630

1an, 8. A. L., and ?eoh, 8. S. A. (2011). 1ranslocal lamlly 8elaLlons amongsL Lhe Lahu ln norLhern 631

1halland. ln: 8rlckell, k. and uaLLa, A. (eds), 6$%(35'1%5 4.'#$%2,".37 *2%1.3J H5%1.3J 632

?'((.1&"'(3. larnham: AshgaLe, pp. 39-34. 633

1enhunen, S. (2011). CulLure, ConfllcL, and 1ranslocal CommunlcaLlon: Moblle 1echnology and 634

ollLlcs ln 8ural WesL 8engal, lndla. R&,('3 76(3), pp. 398-420 633

1rager, L. (2003). lnLroducLlon: 1he uynamlcs of MlgraLlon. ln: 1rager L., (ed) !"#$%&"'( %(- R1'(':< 636

45'@%5 %(- ='1%5 8<(%:"13. WalnuL Creek: AlLa Mlra ress, pp. 1-43. 637

ulmonen, . (2009). lnLerneL, arLs and LranslocallLy ln 1anzanla. *'1"%5 /(&,$'2'5'#< B`(3), pp. 276- 638

290. 639

AccepLed for publlcaLlon ln Ceography Compass

23

unu (2009). Puman uevelopmenL 8eporL 2009. Cvercomlng barrlers: Puman moblllLy and 640

developmenL. unlLed naLlons uevelopmenL rogramme, new ?ork 641

velayuLham, S., and Wlse, A. (2003). Moral economles of a Lranslocal vlllage: obllgaLlon and shame 642

among SouLh lndlan LransnaLlonal mlgranLs. 45'@%5 F.&P'$T3 W(1), pp. 27-47. 643

verne, !. (2012). ="M"(# 6$%(35'1%5"&<> *2%1.J ?+5&+$. %(- R1'(':< "( ?'(&.:2'$%$< *P%,"5" 6$%-.. 644

SLuLLgarL: lranz SLelner verlag. 643

Wlse, A. (2011). ?ou wouldn'L know whaL's ln Lhere would you?' Pomellness and 'lorelgn' Slgns ln 646

Ashfleld, Sydney. ln: 8rlckell, k. and uaLLa, A. (eds), 6$%(35'1%5 4.'#$%2,".37 *2%1.3J H5%1.3J 647

?'((.1&"'(3. Lodon: AshgaLe, pp. 93-108. 648

Wlmmer, A., and Cllck Schlller, n. (2002). MeLhodologlcal naLlonallsm and beyond: naLlon-sLaLe 649

bulldlng, mlgraLlon and Lhe soclal sclences. Clobal neLworks 2(4), pp. 301-334. 630

Zoomers, A., and WesLen, C. v. (2011). lnLroducLlon: Lranslocal developmenL, developmenL corrldors 631

and developmenL chalns. N(&.$(%&"'(%5 8.M.5'2:.(& H5%(("(# O.M".P QQ(4), pp. 377-388. 632

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- Conceptualizing Simultaneity: A Transnational Social Field Perspective On SocietyDocument39 pagesConceptualizing Simultaneity: A Transnational Social Field Perspective On SocietyPatrícia Tavares de FreitasPas encore d'évaluation

- Motility: Mobility As Capital : Vincent Kaufmann, Manfred Max Bergman and Dominique JoyeDocument12 pagesMotility: Mobility As Capital : Vincent Kaufmann, Manfred Max Bergman and Dominique JoyeMuhammad Nurul FajriPas encore d'évaluation

- Levitt, Glick-Schiller - 2004 - Conceptualizing Simultaneity A Transnational Perspective On SocietyDocument38 pagesLevitt, Glick-Schiller - 2004 - Conceptualizing Simultaneity A Transnational Perspective On SocietyKeveen Del Refugio Escalante100% (1)

- Steven Vertovec TransnationalismDocument2 pagesSteven Vertovec TransnationalismtytrackPas encore d'évaluation

- UC San Diego Previously Published WorksDocument25 pagesUC San Diego Previously Published WorksZeynepPas encore d'évaluation

- Transnationalism - Schiller and LevittDocument39 pagesTransnationalism - Schiller and Levitttrevorjohnson515Pas encore d'évaluation

- The New Mobilities Paradigm ExplainedDocument22 pagesThe New Mobilities Paradigm ExplainedAnabel GonzalezPas encore d'évaluation

- Schiller & Salazar (2013) Regimes of Mobility Across The GlobeDocument19 pagesSchiller & Salazar (2013) Regimes of Mobility Across The GlobeMiguel Ángel JiménezPas encore d'évaluation

- Questions of MigrationDocument16 pagesQuestions of MigrationSheikh SakibPas encore d'évaluation

- On The Issue of Diaspora's Terminological Dispersal: June 2020Document13 pagesOn The Issue of Diaspora's Terminological Dispersal: June 2020Gerdav CabelloPas encore d'évaluation

- Towards A Theoretical Ethnography of Migration: David FitzgeraldDocument24 pagesTowards A Theoretical Ethnography of Migration: David FitzgeraldAPas encore d'évaluation

- Mobility as Capital: Motility and Social FluidityDocument12 pagesMobility as Capital: Motility and Social FluidityturudrummerPas encore d'évaluation

- Radcliffe 2017 Decolonising Geographical KnowledgesDocument5 pagesRadcliffe 2017 Decolonising Geographical KnowledgesClyde MatthysPas encore d'évaluation

- The New Mobilities Paradigm - UrryDocument21 pagesThe New Mobilities Paradigm - UrryJuan Ignacio Pérez Karich100% (1)

- 1-New Keywords Migration and BordersDocument34 pages1-New Keywords Migration and BordersMaria V. Martínez GonzálezPas encore d'évaluation

- Configurations of Geographic and Societal Spaces: A Sociological Proposal Between Methodological Nationalism' and The Spaces of Flows'Document24 pagesConfigurations of Geographic and Societal Spaces: A Sociological Proposal Between Methodological Nationalism' and The Spaces of Flows'api_bookPas encore d'évaluation

- Salazar - Mobility - 2019Document6 pagesSalazar - Mobility - 2019mc.fPas encore d'évaluation

- Sheller, M. - MobilityDocument12 pagesSheller, M. - MobilityGustavo Jiménez BarbozaPas encore d'évaluation

- Philosophy Study Analyzes Identity in Era of Global CommunicationDocument7 pagesPhilosophy Study Analyzes Identity in Era of Global CommunicationAlthea Kae Gaon TangcoPas encore d'évaluation

- Transnationalmigration 2017Document7 pagesTransnationalmigration 2017PappaPas encore d'évaluation

- What Attracts Knowledge Workers? The Role of Space and Social NetworksDocument28 pagesWhat Attracts Knowledge Workers? The Role of Space and Social Networkslura saPas encore d'évaluation

- Pisarevskaya Et Al 2019Document27 pagesPisarevskaya Et Al 2019lora nikolaevaPas encore d'évaluation

- Latin Americans in LondonDocument39 pagesLatin Americans in LondonJuan PobletePas encore d'évaluation

- The Limits of GIS: Towards A GIS of Place: Alberto Giordano Tim ColeDocument13 pagesThe Limits of GIS: Towards A GIS of Place: Alberto Giordano Tim ColeAdanely Escudero BarrenecheaPas encore d'évaluation

- BRITAIN, David John. Sedentarism and Nomadism in The Sociolinguistics of DialectDocument34 pagesBRITAIN, David John. Sedentarism and Nomadism in The Sociolinguistics of DialectIncognitum MarisPas encore d'évaluation

- Revisiting The "Transnational" in Migration Studies: A Sociological UnderstandingDocument19 pagesRevisiting The "Transnational" in Migration Studies: A Sociological UnderstandingjescymmPas encore d'évaluation

- From Lifestyle Migration To Lifestyle in Migration - Categories, Concepts and Ways of ThinkingDocument18 pagesFrom Lifestyle Migration To Lifestyle in Migration - Categories, Concepts and Ways of Thinkingjulinau25Pas encore d'évaluation

- Migration, Society and Globalisation: Introduction To Virtual IssueDocument6 pagesMigration, Society and Globalisation: Introduction To Virtual IssueLucianoDalcolVianaPas encore d'évaluation

- Introduction, Towards A Cross-Disciplinary History of TheDocument10 pagesIntroduction, Towards A Cross-Disciplinary History of TheRose BlackpinkPas encore d'évaluation

- ShamirDocument22 pagesShamirPalloma Valle MenezesPas encore d'évaluation

- Walking The Cultural Distance - in Search of Direction Beyond FrictionDocument24 pagesWalking The Cultural Distance - in Search of Direction Beyond FrictionViệtTrầnKhánhPas encore d'évaluation

- A Conceptual and Empirical Approach To C PDFDocument26 pagesA Conceptual and Empirical Approach To C PDFAndre AguiarPas encore d'évaluation

- Reflections on Migration and GovernmentalityDocument25 pagesReflections on Migration and GovernmentalityWalter MendozaPas encore d'évaluation

- Introduction Intercultural ContactDocument27 pagesIntroduction Intercultural ContactCostel Maryan DalbanPas encore d'évaluation

- 336-Article Text-421-1-10-20150819 PDFDocument22 pages336-Article Text-421-1-10-20150819 PDFsarahPas encore d'évaluation

- AucoinPaulineMcKenzie TowardanAnthropologicalUnderstandingofSpaceandPlace 2017 PDFDocument19 pagesAucoinPaulineMcKenzie TowardanAnthropologicalUnderstandingofSpaceandPlace 2017 PDFInácio Dias de AndradePas encore d'évaluation

- Chapter 17Document10 pagesChapter 17Chope PangPas encore d'évaluation

- Toward An Anthropological Understanding of Space and Place: March 2017Document19 pagesToward An Anthropological Understanding of Space and Place: March 2017Pablo PerezPas encore d'évaluation

- History without scale: The micro-spatial perspectiveDocument17 pagesHistory without scale: The micro-spatial perspectiveJerónimo PinedoPas encore d'évaluation

- Searching For An Appropriate Research Strategy On Transnational MigrationDocument21 pagesSearching For An Appropriate Research Strategy On Transnational MigrationThaysa AndréiaPas encore d'évaluation

- Elliott Cooper Et Al 2019 Moving Beyond Marcuse Gentrification Displacement and The Violence of Un HomingDocument18 pagesElliott Cooper Et Al 2019 Moving Beyond Marcuse Gentrification Displacement and The Violence of Un HomingccssnniinnnnaaPas encore d'évaluation

- Global Art and Politics of Mobility TranDocument39 pagesGlobal Art and Politics of Mobility TranTadeu RibeiroPas encore d'évaluation

- J5. Introduction Understanding Migration ResearchDocument8 pagesJ5. Introduction Understanding Migration ResearchFitriyah RasyidPas encore d'évaluation

- Editorial Geohumanities (Cresswell)Document20 pagesEditorial Geohumanities (Cresswell)expanded aestheticsPas encore d'évaluation

- Transnational Behavior in Comparative PerspectiveDocument29 pagesTransnational Behavior in Comparative PerspectiveLazarovoPas encore d'évaluation

- Mills2018 Article IntermarriageTechnologicalDiffDocument36 pagesMills2018 Article IntermarriageTechnologicalDiffArely MedinaPas encore d'évaluation

- Beyond The Diaspora - A Response To Rogers BrubakerDocument13 pagesBeyond The Diaspora - A Response To Rogers BrubakerLa IsePas encore d'évaluation

- Knappet-Technological Mobilities Perspectives From The Eastern Mediterranean An IntroductionDocument17 pagesKnappet-Technological Mobilities Perspectives From The Eastern Mediterranean An IntroductionMartina B. KavurPas encore d'évaluation

- Understanding Immobility: Moving Beyond The Mobility Bias in Migration StudiesDocument28 pagesUnderstanding Immobility: Moving Beyond The Mobility Bias in Migration StudiesShresth DubeyPas encore d'évaluation

- Bailey 2001Document4 pagesBailey 2001berkeaccPas encore d'évaluation

- 7-Urry Mobilities ArtigoDocument22 pages7-Urry Mobilities ArtigoLeandro CarmeliniPas encore d'évaluation

- Demographic Modeling of The Geography of Migration and Population: A Multiregional PerspectiveDocument41 pagesDemographic Modeling of The Geography of Migration and Population: A Multiregional PerspectiveCristian ChiruPas encore d'évaluation

- Thomas Hylland Eriksen - GlobalizationDocument15 pagesThomas Hylland Eriksen - Globalizationbilal.salaamPas encore d'évaluation

- Raghuram - Migration Categories - 2021Document29 pagesRaghuram - Migration Categories - 2021vchsubPas encore d'évaluation

- De Haas - Migration Theory Quo Vadis - PDF PDFDocument39 pagesDe Haas - Migration Theory Quo Vadis - PDF PDFDario NoceraPas encore d'évaluation

- Fichamento - Global History and International Relations - Possible Disciplinary Encounters and An Initial Review of Contributions From Latin American ResearchDocument10 pagesFichamento - Global History and International Relations - Possible Disciplinary Encounters and An Initial Review of Contributions From Latin American ResearchBeatriz DevidesPas encore d'évaluation

- Mapping the Transnational World: How We Move and Communicate across Borders, and Why It MattersD'EverandMapping the Transnational World: How We Move and Communicate across Borders, and Why It MattersPas encore d'évaluation

- Language of Tomorrow: Towards a Transcultural Visual Communication System in a Posthuman ConditionD'EverandLanguage of Tomorrow: Towards a Transcultural Visual Communication System in a Posthuman ConditionPas encore d'évaluation

- Immigration and Integration in Israel and BeyondD'EverandImmigration and Integration in Israel and BeyondOshrat HochmanPas encore d'évaluation

- Editorial: Scandinavian Housing and Planning ResearchDocument2 pagesEditorial: Scandinavian Housing and Planning ResearchgioanelaPas encore d'évaluation

- Capital Leakage From Owner-Occupied Housing: Jim Kemeny and Andrew ThomasDocument18 pagesCapital Leakage From Owner-Occupied Housing: Jim Kemeny and Andrew ThomasgioanelaPas encore d'évaluation

- The Significance of Swedish Rental Policy: Cost Renting: Command Economy Versus The Social Market in Comparative PerspectiveDocument14 pagesThe Significance of Swedish Rental Policy: Cost Renting: Command Economy Versus The Social Market in Comparative PerspectivegioanelaPas encore d'évaluation

- Post Industrial Housing Crisis-A Comment On Anneli Juntto: Scandinavian Housing and Planning ResearchDocument2 pagesPost Industrial Housing Crisis-A Comment On Anneli Juntto: Scandinavian Housing and Planning ResearchgioanelaPas encore d'évaluation

- Political Science Faculty Win 2 Major CSU AwardsDocument6 pagesPolitical Science Faculty Win 2 Major CSU AwardsgioanelaPas encore d'évaluation

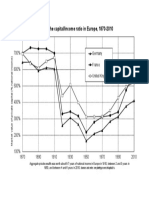

- Figure I.2. The Capital/income Ratio in Europe, 1870-2010: Germany France United KingdomDocument1 pageFigure I.2. The Capital/income Ratio in Europe, 1870-2010: Germany France United KingdomgioanelaPas encore d'évaluation

- F10 5-2 PDFDocument1 pageF10 5-2 PDFgioanelaPas encore d'évaluation

- Contemporary Issue PaperDocument1 pageContemporary Issue PapergioanelaPas encore d'évaluation

- Religion Is Not What It Used To Be. Consumerism, Neoliberalism, and The Global Reshaping of ReligionDocument10 pagesReligion Is Not What It Used To Be. Consumerism, Neoliberalism, and The Global Reshaping of ReligiongioanelaPas encore d'évaluation

- A Qualitative Examination of Jim Kemeny's Arguments On High Home Ownership, The Retirement Pension and The Dualist Rental System Focusing On AustraliaDocument23 pagesA Qualitative Examination of Jim Kemeny's Arguments On High Home Ownership, The Retirement Pension and The Dualist Rental System Focusing On AustraliagioanelaPas encore d'évaluation

- F10 10 PDFDocument1 pageF10 10 PDFgioanelaPas encore d'évaluation

- Figure 1.1. The Distribution of World Output 1700-2012: Asia AfricaDocument1 pageFigure 1.1. The Distribution of World Output 1700-2012: Asia AfricagioanelaPas encore d'évaluation

- 2020.4 Coronavirus Crisis Underlines Weak Spots in U.S. Economic System - The New York TimesDocument3 pages2020.4 Coronavirus Crisis Underlines Weak Spots in U.S. Economic System - The New York TimesgioanelaPas encore d'évaluation

- Rati 12127Document16 pagesRati 12127gioanelaPas encore d'évaluation

- Renewable and Sustainable Energy ReviewsDocument15 pagesRenewable and Sustainable Energy ReviewsgioanelaPas encore d'évaluation

- Plagiarism in The Japanese Universities: Truly A Cultural Matter?Document13 pagesPlagiarism in The Japanese Universities: Truly A Cultural Matter?gioanelaPas encore d'évaluation

- Dan BadulescuDocument2 pagesDan BadulescugioanelaPas encore d'évaluation

- 2020.4 Coronavirus Stimulus Package F.A.Q. - Checks, Unemployment, Layoffs and More - The New York TimesDocument12 pages2020.4 Coronavirus Stimulus Package F.A.Q. - Checks, Unemployment, Layoffs and More - The New York TimesgioanelaPas encore d'évaluation

- Wealth inequality in the U.S. over 200 years: top 10% own 80% in 1910, 75% todayDocument1 pageWealth inequality in the U.S. over 200 years: top 10% own 80% in 1910, 75% todaygioanelaPas encore d'évaluation

- Geopolitics and Diffusion of Economics in Communist RomaniaDocument22 pagesGeopolitics and Diffusion of Economics in Communist RomaniagioanelaPas encore d'évaluation

- Sumer Travel 2020 FlightsDocument2 pagesSumer Travel 2020 FlightsgioanelaPas encore d'évaluation

- Book Review - Has Globalization Gone Too Far - by Dani Rodrik. Wash PDFDocument18 pagesBook Review - Has Globalization Gone Too Far - by Dani Rodrik. Wash PDFgioanelaPas encore d'évaluation

- Global Poverty Section 102 & 105 SyllabusDocument2 pagesGlobal Poverty Section 102 & 105 SyllabusgioanelaPas encore d'évaluation

- Contemporary Issue PaperDocument1 pageContemporary Issue PapergioanelaPas encore d'évaluation

- F10 5-2 PDFDocument1 pageF10 5-2 PDFgioanelaPas encore d'évaluation

- 2020.4 Coronavirus Stimulus Package F.A.Q. - Checks, Unemployment, Layoffs and More - The New York TimesDocument12 pages2020.4 Coronavirus Stimulus Package F.A.Q. - Checks, Unemployment, Layoffs and More - The New York TimesgioanelaPas encore d'évaluation

- 2020.4 Coronavirus Crisis Underlines Weak Spots in U.S. Economic System - The New York TimesDocument3 pages2020.4 Coronavirus Crisis Underlines Weak Spots in U.S. Economic System - The New York TimesgioanelaPas encore d'évaluation

- Smith1776 1Document98 pagesSmith1776 1gioanelaPas encore d'évaluation

- F10 10 PDFDocument1 pageF10 10 PDFgioanelaPas encore d'évaluation

- F1 1 PDFDocument1 pageF1 1 PDFgioanelaPas encore d'évaluation