Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Impact of Ebiz Iniviative On Fitm Value

Transféré par

Sahil SuderaTitre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Impact of Ebiz Iniviative On Fitm Value

Transféré par

Sahil SuderaDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Electronic Commerce Research and Applications 1 (2002) 4156 www.elsevier.

com / locate / ecra

Impact of e-Business initiatives on rm value

Ho Geun Lee*, Dong Hwan Cho, Seong Chul Lee

Department of Business Administration, College of Business and Economics, Yonsei University, Shinchon-Dong 134, Seodaemun-Ku, Seoul 120 -749, South Korea Accepted 10 April 2002

Abstract A growing number of rms are competitively entering into e-Business because they see the high potential of e-Business growth as an opportunity. The positive expectation of the e-Business market leads most rms to go into e-Business, but it is not clear what kinds of benets rms gain through e-Business. In this paper, we examine whether rms economic benets are related to e-Business activities. For this purpose, we employ event study methodology and assess the cumulative abnormal returns for 782 e-Business initiatives by rms listed in Korean capital markets. The well-known Dot Com Effect is veried empirically by this study. The results of this study indicate that e-Business potential is highly valued in the capital market, and e-Business rms are expected to create signicant benets in the future period. 2002 Published by Elsevier Science B.V.

Keywords: e-Business; Electronic commerce; Event study; Market value; Internet economy

1. Introduction People are becoming more interested in the Internet and e-Business all over the world. Such interest can be observed by the increasing number of Internet users. According to NUA, an Internet survey investigator in the US, the number of home Internet users was estimated to be 379 million in 2001 [1]. This gure is about twice the 201 million users in 1999. Korea is not an exception to this fast growing trend, and the number of Internet users in Korea was 19 million at the end of December 2000 [2]. This huge number of Internet users in Korea, and the world,

* Corresponding author. Tel.: 1 82-2-2123-4470; fax: 1 82-2393-7430. E-mail address: hlee@base.yonsei.ac.kr (H.G. Lee).

means a lot of potential customers in the e-Business market. The e-commerce market around the world was estimated to be more than $500 billion in 2001, and is expected to reach $1.49 trillion in 2003 according to Forrester Research. LG Economic Research Institute and Andersen Consulting state that the e-commerce market size in Korea is expected to grow about 100% every year [3]. Another reason that rms have been entering the e-Business market emulously is the high stock prices of Internet rms [4] (p. 25). Korean Internet rms have had very high stock prices compared to other stocks in Korea. The KOSDAQ index was over 290 at one time with an annual growth rate of more than 100%, and this number was actually driven by Internet rms. A number of brick-and-mortar rms, which observed the high stock prices of Internet rms, have been

1567-4223 / 02 / $ see front matter 2002 Published by Elsevier Science B.V. PII: S1567-4223( 02 )00005-4

42

H.G. Lee et al. / Electronic Commerce Research and Applications 1 (2002) 41 56

making efforts to enter e-Business, and new Internet start-ups have been increasing. Although many companies enter the e-Business arena looking at the fast growing number of Internet users and the rapid growth of the e-commerce market, evidence of the benets to rms from eBusiness initiatives is far from unequivocal, and the costs of entry are real and overwhelming. Considerable up-front investments for creating e-Business capabilities are required to be a viable player in the current e-Business environment. According to a recent report, the construction and engineering industry spent $1,863 per employee for e-commerce initiatives, compared with the nancial services sector which made e-commerce investments of $13,628 per worker [5]. The Gartner Group estimates that the average cost of developing and launching an e-Business web site is $1 million, and it needs $520 million to achieve market differentiation that sets it apart from the competition [6]. Further, the publicly reported gures for hardware and software expenditures in e-Business ventures comprise only 21% of the overall costs, with the predominant expense being the labor costs for developing the site and implementing interfaces to back-end business applications. This cost of development and implementation of web sites is expected to rise by 25% annually [7]. Once these investments are in place, the company needs to promote its e-Business web site. This effort can include putting banner ads in one of the portal sites, or placing commercials in newspapers, magazines, or on TV. As the number of e-Business rms is growing from day to day, these kinds of costs are inevitable, and it looks as if the amount of money required for such advertising is increasing [8] (p. 136). Although e-Business requires many such costs, a growing number of rms are making, or considering making, such investments both in information technologies and in organizational changes related to e-Business. A research question that follows is: What are the economic returns to rms from engaging in e-Business? In this paper, we focus on the market value of rms based on the economic returns they receive through e-Business activities. We analyze the impact of e-Business initiatives on the market value of rms in Korea. For this purpose, we employ the event

study methodology, which is based on the efcient market hypothesis. In an efcient capital market, investors are believed to recognize future benet streams from managerial initiatives announced by rms, a judgment subsequently reected in the stock price of the rm. If e-Business activities enhance future cash ows, the capital market would respond favorably to e-Business announcements by rms, and this would be reected in a positive movement of their stock price. Event study methodologies are very useful tools for management researchers to examine the consensus estimates regarding the future benet streams attributable to organizational initiatives [9] (p. 626). The impact of e-commerce initiatives on the market value of rms in the USA was investigated by Subramani and Walden [8]. They validated the popular notion of the Dot Com Effect by showing that the Abnormal Returns of e-commerce initiatives were greater than the normal market returns. However, their research interest was conned to e-commerce rms and a small number of e-commerce initiatives. This study differs from theirs in two distinct ways. First, we have expanded the types of e-Business rms investigated as well as these rms e-Business initiative types, so that broader ranges of e-Business activities can be evaluated. Second, eBusiness initiatives are analyzed in two different capital markets (KSE and KOSDAQ) to investigate whether similar e-Business initiatives result in different rm values in the two markets. In this paper, we empirically study the Dot Com Effect in Korea by assessing the value implications of e-Business initiatives announced by rms. We examine if the economic value of e-Business initiatives is linked to the nature of the stock market, whether the stock market is KSE (Korea Stock Exchange) or KOSDAQ. We also investigate if the economic value of e-Business initiatives is associated with the nature of the e-Business rm layers, whether the layer is Internet infrastructure, application, intermediary or commerce. It is assessed if the protability of e-Business initiatives is inuenced by the nature of the e-Business initiative, whether it relates to business-to-consumer e-commerce or business-to-business e-commerce. It is also examined if the protability of e-Business is related to the types of e-Business initiatives.

H.G. Lee et al. / Electronic Commerce Research and Applications 1 (2002) 21 56

43

2. Research hypotheses

2.2. Capital markets

The KSE (Korea Stock Exchange) has expanded greatly since it opened its market in 1956. When it opened its market, there were only 12 listed companies. Now it is the oldest and biggest stock market in Korea, and it is among the top 10 markets of the world in terms of transaction volume and total market price. To support this fast growth, it moved ahead with computerization of its trading system in 1981, and the KSEs trading system was fully computerized in September 1997. Now it has a stock market, bond market, options market, and a futures market [14]. The KOSDAQ (Korea Securities Dealers Automated Quotation) is a kind of institutionalized offboard market. Examples of these off-board markets are NASDAQ in the US, JASDAQ in Japan, and USM in England. The off-board stock market of Korea was rst institutionalized in April 1987, and KOSDAQ was inaugurated in July 1996. Since KOSDAQ began, it has expanded greatly in terms of listed companies and total market price [15]. e-Business has swept both stock markets in Korea, and at this time the stock prices of e-Business rms are rated high. This is shown clearly in the Internet Bubble, with an apprehensive voice. The cause of this enthusiasm for e-Business-related stocks is likely to be found in the expectation of a rms rapid renovation and remarkable success on introducing Internet technology [4] (pp. 2528). It is KOSDAQ that has been taking the lead for this eagerness in Korea. The KOSDAQ Premium is well known to investors in Korea. It means that stock prices are far more highly valued in KOSDAQ than in KSE, even if they are the same sized rms engaging in the same business [16]. Because Internet-related stocks and technology related stocks have a high potential for future growth, KOSDAQ, in which many of these stocks are listed, is highly valued in the Korean stock market. Certainly, even though KSE has Internetrelated stocks and technology related stocks, their numbers are relatively small and, moreover, the majority of these stocks listed in KSE are conventional brick-and-mortar rms. Consequently, stocks listed in KOSDAQ are expected to be more highly valued than in KSE.

2.1. Dot Com Effect

The mass media, such as newspapers and TV, report that the number of Internet users is rapidly increasing, and that the e-Business market will grow sharply. This trend brings about the emergence of continuous Internet rm initiatives and changes of conventional rms operational structure to adjust to Internet environments. Firms that cannot adjust to new managerial environments such as the Internet should not survive in the long run. This trend is also presented in the new terminology of the New Economy, as opposed to the Old Economy or manufacturing-based economy. Under these circumstances, new e-Business initiatives or changes of operational structures to adjust to the Internet environment can be viewed as attempts to take advantage of e-Businesss potential and to improve future benets for the rms. Furthermore, IT investments related to e-Business will enhance rms operational efciency, and this will likely lead to operational cost savings and enhanced cash ow [10]. In terms of the resource-based view of the rms [1113], rms investment in e-Business can be regarded as creating diverse resources to perform their own e-Business. Firms initiating e-Business earlier than competitors can learn more quickly about e-Business, better capture the diverse resources required for e-Business activities, and gain considerable organizational experience and understanding of the e-Business market. Consequently, rms engaging in e-Business will achieve a considerably advantageous position, sufcient to achieve strategic and operational superiority. If so, investors are likely to respond positively to the e-Business initiatives by rms and consequently positive abnormal stock market returns are yielded. This positive abnormal stock market return is a risk-adjusted return that exceeds the average stock market return, which leads to the following hypothesis that e-Business initiatives would consequently improve the market valuation of rms. Hypothesis 1. For rms engaging in e-Business activities, the abnormal returns attributable to eBusiness initiatives are positive.

44

H.G. Lee et al. / Electronic Commerce Research and Applications 1 (2002) 41 56

In the case of the United States, Internet rms performed better than conventional brick-and-mortar rms in terms of stock price returns in the period from June 1998 to June 1999. In this period, the index of Internet rm stocks increased to returns of about 400% annually. The returns of the S&P500 or the Dow-Jones Industrial Average based on conventional rms increased 18.90%, on average [4] (pp. 307308). Similarly, in Korea, due to the KOSDAQ Premium, the stock prices in KOSDAQ, where a large number of state-of-the-art Internet rms are centralized, are more highly valued. If so, investors are likely to respond more positively to e-Business initiatives by the rms listed in KOSDAQ than those listed in KSE. This suggests that the abnormal returns of rms listed in KOSDAQ are higher than the abnormal returns of KSE-listed rms after new e-Business initiatives. This leads to the following hypothesis. Hypothesis 2. The abnormal returns attributable to e-Business initiatives of KOSDAQ-listed rms are higher than the abnormal returns attributable to eBusiness initiatives of KSE-listed rms.

2.3. e-Business rm layers

The e-Business rm categorization used in this paper is based on the previous research of the University of Texas and Cisco systems [17]. According to this report, there is a natural structure or hierarchy to the Internet economy that can be directly traced to how businesses generate revenues. Based upon this type of structure, the Internet economy is broadly classied into infrastructure and economic activity categories. The infrastructure category is further divided into two distinct but complementary layers: the Infrastructure layer, and the Applications layer. The economic activity category is also subdivided into two layers: the Intermediary layer and the Commerce layer. Fig. 1 shows these layers with example companies in the USA and Korea. Taking into account the rapidly increasing number of Internet users, the expected future rapid growth of the e-commerce market, and the enhancement of rms operational efciency attributable to e-Busi-

ness investments, it is suggested that potential growth and benets of e-Business rms related to the Intermediary or Commerce layer are relatively higher than those related to the other layers. Also, e-Business is likely to substitute for the conventional business domain in these layers. Among American companies, Amazon.com may be a good example. Amazon.com has encroached on the business of Barnes & Noble, a gigantic bookseller in American book retailing. As a result, Barnes & Noble entered into e-Business. However, reports indicate that a considerable number of e-Business rms, including Amazon.com, will be on the verge of bankruptcy sooner or later due to fund starvation [18]. This analysis suggests that their fund holdings will nally be exhausted because a large number of e-Business rms do not have solid prot structures. Considering this analysis, those e-Business rms in the Infrastructure or Application layers equipped with a solid business base should be more protable than e-Business rms in the Intermediary or Commerce layers. Some analysts predict that the rms which will eventually earn prots attributable to the growth of e-Business are not those in the Intermediary or Commerce layers, but are those in the Infrastructure or Application layers. Metaphorically speaking, at the time of the Gold Rush in the United States, it was mining equipment providers who actually earned money, not gold mine operators or miners who went to seek for gold in the West. The bright prospect of e-Business growth has driven many rms to enter e-Business. However, it may be the rms providing e-Business rms with equipment, networks, and applications that ultimately earn money [19]. Based on the above argument, it is difcult to estimate accurately which rms among the four layers will be affected more by e-Business initiatives. Therefore, we rst hypothesize that the effects of e-Business initiatives are different according to the layers, and reveal the differences among layers through data analysis results.

Hypothesis 3. The abnormal returns attributable to e-Business initiatives are different depending on the layer to which the e-Business rm belongs.

H.G. Lee et al. / Electronic Commerce Research and Applications 1 (2002) 21 56

45

Fig. 1. e-Business rm layers.

2.4. B2 B vs. B2 C e-Business rms

Electronic Commerce is classied roughly into two categories: Business-to-Business Electronic Commerce (B2B), and Business-to-Consumer Electronic Commerce (B2C) [20]. B2B is commerce where transactions between rms are performed or supported on-line. Typical examples include manufacturers who purchase raw material on-line, or who sell their products to retailers on-line. B2C is commerce where consumers are provided with products

or services via the Internet, and most Internet shopping malls and portal site services are examples. According to Forrester Research, the B2B e-commerce market will rapidly grow from $251 billion in 2000 to $1,331 billion by 2003. In contrast, the B2C e-commerce market will grow from $33 billion in 2000 to $108 billion by 2003. Many market research estimates consistently claim that the B2B market scale is much bigger than that of B2C. Similarly, it is expected that the increase in the B2B e-commerce market is likely to far exceed that of the B2C

46

H.G. Lee et al. / Electronic Commerce Research and Applications 1 (2002) 41 56

e-commerce market in Korea. According to Anderson Consulting, the B2B e-commerce market in Korea is estimated to grow from $300 million in 2000 to $7,100 million by 2005. The B2C e-commerce market in Korea is estimated to grow from $150 million in 2000 to $1,000 million by 2005 [3]. However, B2B e-Businesses inherently have risks. In order to activate e-commerce between rms, it is required to integrate the processes between the participating rms. Establishing effective managerial processes between rms is also challenging [21]. These tasks cannot be accomplished easily and thus B2B e-Business inherently involves complexity and high risk. B2B rms tend to be relatively large-sized. In other words, their sales volume and the number of employees are relatively large. In contrast, B2C rms tend to be small-sized. According to CAPM (Capital Asset Pricing Model), the expected returns of a stock are only evaluated by the systematic risk, regardless of the scale of the rm that issues the stocks. In reality, however, it has been observed that higher abnormal returns are created in small-sized rms, which is termed the rm size effect [22]. Considering this effect, it is suggested that the abnormal returns created by relatively small-sized B2C rms are larger than those of larger B2B rms. Considering the inherent complexity and high risk of B2B e-Business, and the rm size effect in actuality, it is estimated that the market valuation associated with e-Business initiatives is higher in B2C rms than in B2B rms. This leads to the following hypothesis. Hypothesis 4. The abnormal returns attributable to e-Business initiatives of B2C rms are higher than the abnormal returns attributable to e-Business initiatives of B2B rms.

disclosed to the public with public announcements, which can help investors judge investment decisions rationally, can help securities circulate smoothly, and can help the practice of fair trading to be established [23]. Public announcements on a legal basis can be divided into two groups: legal, an enforced public announcement, or autonomous, an optional public announcement. The former is an announcement by the commercial law, the securities exchange law, and KOSDAQ managerial regulations (public announcements in a narrow sense), and the latter is an announcement by the press (public announcements in a broad sense) [24]. In this paper, public announcements are limited to autonomous optional public announcements made by rms through the press (Public announcement in a broad sense). We are mainly interested in the public announcements associated with new e-Business initiatives or the expansion of an existing e-Business. We classify them into three categories: (1) e-Business initiatives related to the alliances between rms; (2) e-Business initiatives related to the expansion of conventional off-line rms by entering into e-Business; and (3) e-Business initiatives related to the business expansion of existing e-Business rms. Table 1 shows the categories and the denitions of each e-Business initiative used in this study. Because these categories have different natures, market valuations are likely to vary according to the category of e-Business initiative. For instance, when a brick-and-mortar rm enters into new on-line markets, its impact might differ from when an Internet shopping mall expands its business within on-line markets. Thus, we hypothesize that the effects of e-Business initiatives are different depending on the types of announcements. Hypothesis 5. The abnormal returns attributable to e-Business initiatives are different depending on the types of e-Business initiatives.

2.5. e-Business initiative types

Public announcements are intended to inform the stakeholders of any changed conditions about the rm. Legally, the public announcement system imposes duties on companies, requiring them to announce information essential to stakeholders judgment, such as nancial statements or new business initiatives. Major information about the company is

3. Research design

3.1. Event study methodology

The event study methodology has begun to be used as a powerful tool that can help IS researchers

H.G. Lee et al. / Electronic Commerce Research and Applications 1 (2002) 21 56 Table 1 Classication of e-Business initiatives Category Alliance-related initiatives Denition of e-Business initiative

47

1. Alliance 1 Business Expansion Business expansion by alliance between companies Example: LG International Corp. agrees to make strategic alliance with SK Global to develop B2B web-site Chemround 2. Alliance 1 Investment 1 Business Expansion Business expansion by alliance and investment between companies, including the establishment of afliated companies Example: Hyundai Corporation establishes an e-Business rm together with LG International and SK Global by participating in Chemround.com 3. Alliance 1 Technology Development Technology development by alliance between companies Example: SK Telecom tries to develop new wireless multimedia service together with AT&T 1. Change of Firm Name To change the company name into Dot Com, Net, Tech, etc. Example: Kasan Electronics changes its name to Mplus Tech 2. Addition of Firm Objective To add e-Business-related objective to rms current objectives or to change rms objective into e-Business-related objective Example: Kisan Telecom adds e-Business to its business objectives 3. Expansion of Non-Internet Firm into e-Business Traditional company (non-Internet company) goes into e-Business Example: Pulmuone drives e-Business in retail industry 1. e-Business Domain Expansion To expand its own e-Business in the already entered domain, or to the lower layers (to expand its own e-Business in the same e-Business rm layers, or when the rms in layer 3 or 4 expand their e-Business into layer 1 or 2 e-Business) Example: Terra expands its business into UMS-related equipment manufacturing and super-speed Internet business 2. Layer 1 / 2 Firms e-Business Expansion into Layer 3 / 4 Company in layer 1 or 2 goes into on-line e-Business of layer 3 or 4 Example: Pantech expands its business into Internet and e-commerce services

Business expansion from non-Internet into e-Business

Business expansion of established e-Business rms

Layer 1 (Infrastructure layer), layer 2 (Application layer), layer 3 (Intermediary layer), layer 4 (Commerce layer).

assess the business performance of IT investments such as e-Business initiatives. It obviates the need to analyze accounting-based measures of IT investments benets, which have been criticized because they are often not adequate indicators of the true performance of IT investments [9] (p. 626). We take the event study methodology that estimates the AR (Abnormal Return) of rm activities as a method for evaluating the market values of eBusiness rms. AR represents the estimated future return of rms forecasted by many investors related to e-Business initiatives in capital markets. This method has been successfully used in previous studies [8,25,26]. If investors speculate that the

company announcing the start of a new e-Business can create future prot through this e-Business initiative, they would respond positively to the companys new e-Business activities. This will be represented by positive abnormal stock market return after the event day. Selection of the length of an event period and an estimation period is based on previous event studies. We select ve days before and after the event announcement (for a total of 11 days) as the event period to observe the effect of e-Business initiatives (t 5 [25,5]). For the estimation period, we used 45 days before the event (t 5 [250, 2 6]) to estimate the expected return. Appendix A describes in detail how

48

H.G. Lee et al. / Electronic Commerce Research and Applications 1 (2002) 41 56

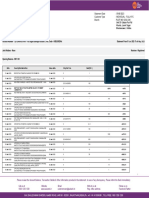

Table 2 Classication of e-Business rms in Korea Layer Market KSE 1 2 3 4 1, 2 1, 3 1, 4 2, 3 3, 4 1, 2, 4 1, 3, 4 2, 3, 4 Total 36 7 31 33 2 1 1 5 2 1 119 KOSDAQ 43 23 7 9 1 2 3 6 1 1 96 Total 79 30 38 42 3 2 4 7 6 2 1 1 215

ments by those selected rms was 388 in KSE and 394 in KOSDAQ for the predetermined six months. Thus, a total of 782 e-Business initiatives were used in analysis of the data. In order to test the research hypotheses, we classied these e-Business initiatives according to the research variables. These research variables included KSE and KOSDAQ, e-Business rm layers, B2B and B2C, and e-Business initiative types. Table 3 shows the distribution of e-Business initiatives used for each hypothesis test. To maintain consistency throughout the analysis, we excluded some sample data if they did not belong to relevant categories. Thus, three hypotheses (Hypotheses 3, 4, and 5) use some of the 782 data points.

4. Analysis and discussion to calculate the abnormal return. This computation is consistent with related studies in MIS, accounting and nance.

4.1. Effect of e-Business initiatives

Fig. 2 presents the effect attributable to e-Business initiatives of all e-Business rms listed in KSE and KOSDAQ. In this gure, bars in the graph present CAR2 for 782 e-Business initiatives. The graph shows that the CAR for the ve days after the event day are higher than the CAR for the ve days before the event, with the event day the turning point. The biggest increase of CAR is on the day of the event, which increases from 2.17 to 3.50%. We observe that CAR slowly increases except for day t 1 2 (2 days after the day of the event), and it reaches 4.74% on day t 1 5, which is the impact of the e-Business initiative on rm value. The graph also includes a signicance test of Hypothesis 1. The shaded region represents the outer limits of the 95% condence interval over the time window for the hypothesis that CAR is positive (CAR . 0). Therefore, all bars rising above the shaded region are statistically signicant at the 0.05 level. For all bars remaining below the shaded region, CAR is not statistically signicant at the 0.05 level. As shown in Fig. 2, Hypothesis 1 is accepted

CAR (Cumulative Abnormal Return) is the return that sums cumulatively the abnormal return at each time. Abnormal return is an excess stock return resulting from e-Business initiatives. For details of abnormal return and CAR, refer to Appendix A.

2

3.2. Data collection

Korean rms related to our research were collected and categorized in order to examine the AR (Abnormal Returns) attributable to the e-Business initiatives of these rms. This was done by referencing guidebooks 1 which contain information about publicly traded rms, searching the Internet, and visiting the web-sites of those rms. We selected rms from those listed in the KSE and KOSDAQ, and categorized them into four layers. This categorization of four layers was done according to previous research [27]. Through this investigation, we identied 215 rms, with 119 rms listed in KSE and 96 rms listed in KOSDAQ (see Table 2). In the next step, we collected new e-Business initiatives released by these rms for six months from October 1, 1999 to March 31, 2000. The collected public announcements are related to the beginning of a new e-Business or the expansion of an established one. The number of public announce1 Korean Credit Information, Analysis of Listed Firms, Maeil Business Newspaper, Korean Credit Information, 2000, Shinhan Jeungkwon Investment, 2000 Stock Investment List@KOSDAQ Companies, The Korea Economic Daily, Seoul, 2000.

H.G. Lee et al. / Electronic Commerce Research and Applications 1 (2002) 21 56 Table 3 Number of e-Business initiatives Distinction Market type KSE Capital market Total (Hypotheses 1 and 2) e-Business rm layers KSE KOSDAQ Layer Layer Layer Layer B2B B2C Alliance-related Business expansion from non-Internet into e-Business Business expansion of established e-Business rms 1 2 3 4 (Infrastructure) (Application) (Intermediary) (Commerce) 388 388 165 30 48 65 308 132 128 260 105 38 49 192 394 394 172 81 19 25 297 111 125 236 98 61 48 207 782 337 111 67 90 605 243 253 496 203 99 97 399 KOSDAQ Total

49

Total (Hypothesis 3) B2B / B2C Total (Hypothesis 4) e-Business initiative types

Total (Hypothesis 5)

and, consequently, abnormal returns attributable to e-Business initiatives are positive.

4.2. Returns to KSE-listed rms vs. KOSDAQlisted rms

Fig. 3 presents the results for the test of Hypothesis 2. CARs for KOSDAQ-listed rms and KSElisted rms are presented in Fig. 3a and b, respectively, and Fig. 3c depicts the differences in the CARs between KOSDAQ-listed rms and KSElisted rms (CAR KOSDAQ 2 CAR KSE ). We can see that the CAR in both Fig. 3a and b increase considerably since the event day. The difference shown in Fig. 3c is positive, which is the same direction as postulated in the hypothesis. This is the

effect difference between KOSDAQ-listed rms and KSE-listed rms attributable to e-Business initiatives. The null hypothesis is rejected because the bars rise above the shaded region (95% condence level). Consequently, we accept Hypothesis 2 that the abnormal returns attributable to e-Business initiatives of KOSDAQ-listed rms are higher than those in KSE.

4.3. Returns according to e-Business rm layers

KSE and KOSDAQ are different markets, and their natures are distinct, as revealed in the test of Hypothesis 2. From now on, we analyze the remaining hypotheses (Hypotheses 3, 4, and 5) by separating the rms listed in KSE and KOSDAQ. With clear

Fig. 2. CARs for e-Business initiatives. *Shaded region represents the critical value of the test CAR 5 0, with a 5 0.05.

50

H.G. Lee et al. / Electronic Commerce Research and Applications 1 (2002) 41 56

Fig. 3. CARs for KSE-listed rms vs. KOSDAQ-listed rms.

differences in KSE and KOSDAQ, hypothesis testing with combined data from both markets may lead to the wrong conclusions. We employ ANOVA3 to test Hypothesis 3 (detailed results are provided in Appendix B). For KSE, the P value, which indicates the difference in CAR according to e-Business rm layers, is 0.037. Consequently, Hypothesis 3, that the abnormal returns attributable to e-Business initiatives are different depending on the layers to which the e-Business rm belongs, is accepted. To nd the reason for this result, we performed post hoc analysis 4 to examine in which layers there is a difference. We found that CAR in layer 2 has a negative (2) value, and is signicantly different from the CARs in other layers. In KOSDAQ, the P value, which indicates the difference in CAR according to e-Business rm layers, is 0.940, which is not signicant at the 0.05 level. No matter which layer rms in KOSDAQ belong to, their CARs of e-Business initiatives remain high. So, there is no difference in CAR

3

according to layers in KOSDAQ-listed rms. Consequently, Hypothesis 3, that the abnormal returns attributable to e-Business initiatives are different according to the layers, is rejected for KOSDAQ. It is interesting to note that large software rms listed in KSE (Application layer rms) do not enjoy dot com effects, while rms in KOSDAQ exhibit signicant impacts of e-Business initiatives on their rm value regardless of the layer. One possible explanation for this difference is that investors consider the proliferation of e-Business as signicant opportunities for relatively small software rms (mostly listed in KOSDAQ), but threats to large software rms (mostly listed in KSE). For large Application layer rms, the focus on traditional software may serve as a liability in the new digital economy, where small and fast moving software venture rms have advantages.

4.4. Returns to B2 B rms vs. B2 C rms

Fig. 4 presents the test results for Hypothesis 4 on KSE-listed rms. Fig. 4a depicts B2C rms, Fig. 4b depicts B2B rms, and Fig. 4c depicts the difference between B2C rms and B2B rms (CAR B2C 2 CAR B2B ). It indicates that the direction of difference

This is to test if there is a difference between the mean for six days after the event day and the mean for ve days before the event day according to layers. 4 Duncans method was used in the post hoc analysis.

H.G. Lee et al. / Electronic Commerce Research and Applications 1 (2002) 21 56

51

Fig. 4. CARs for B2B rms and B2C rms in KSE.

is the same as hypothesized. In Fig. 4a, the CAR of 2.96% on the day of the event continuously increases to reach 4.80% at day t 1 5. In Fig. 4b, the CAR gradually decreases at the turning point of day t 1 1, with the exception of 0.81% CAR on day t 1 5. In Fig. 4c, the CAR of B2C rms is higher than that of B2B rms for all the event window, and their CAR differences are positive. Consequently, Hypothesis 4 is supported in KSE. The abnormal returns attributable to e-Business initiatives of B2C rms are higher

than the abnormal returns attributable to e-Business initiatives of B2B rms. Fig. 5 depicts the test results of Hypothesis 4 on KOSDAQ-listed rms. Fig. 5a depicts B2C rms, Fig. 5b depicts B2B rms, and Fig. 5c depicts the difference in CAR between B2C rms and B2B rms (CAR B2C 2 CAR B2B ). In Fig. 5a, the CAR of 2.74% on the event day increases to 4.25% at day t 1 5. In Fig. 5b, the CAR of 5.59% on the event day increases to 7.44% on day t 1 5. In Fig. 5c, the

Fig. 5. CARs for B2B rms and B2C rms in KOSDAQ.

52

H.G. Lee et al. / Electronic Commerce Research and Applications 1 (2002) 41 56

differences in CAR between B2C rms and B2B rms listed in KOSDAQ (CAR B2C 2 CAR B2B ) are the opposite of those hypothesized (Hypothesis 4) and they are not signicant across the event window at the 0.05 level. Consequently, Hypothesis 4 is rejected in KOSDAQ. The abnormal returns attributable to e-Business initiatives of B2C rms are higher than the abnormal returns attributable to e-Business initiatives of B2B rms. It should be noted that Hypothesis 4 is supported in KSE, but rejected in KOSDAQ. Although the reason for this difference is not clear, we have a plausible explanation. The period during which data was collected for this study was when the e-Business theme was transferring from B2C to B2B. Investors in KOSDAQ tend to be swift in absorbing new trends in the Internet economy. Thus, B2B rms are highly valuated in KOADAQ, which is sensitive to new trends in e-Business. In contrast, B2B rms are less valued in KSE, which is slow to respond to the new e-Business movement. B2C rms have enjoyed scale effects (B2C rms are smaller than B2B rms, thus gaining more stock returns than B2B rms) in KSE and this results in supporting Hypothesis 4.

rms in KSE, and the analysis results are provided in Appendix B. According to the results, in KOSDAQ, the P value, which indicates the difference in CAR according to the categories of public announcements, is 0.265, which is not statistically signicant at the 0.05 level. Consequently, Hypothesis 5, that the abnormal returns attributable to e-Business announcements are different according to the categories of public announcements, is rejected in KOSDAQ. These results are similar to those of Hypothesis 3. Whereas there are signicant differences in CAR according to e-Business rm layers and categories of public announcements in KSE, there are no signicant CAR differences in KOSDAQ. Appendix C provides the Cumulative Abnormal Returns according to each hypothesis over the veday time window.

5. Conclusion Overall, the results of this study suggest that e-Business initiatives contribute to the creation of considerable future benets for rms, which is reected in an enhancement of the market values of rms. Similarly to the results of a previous study [8], the results of this study suggest that rms competitively entering into e-Business may be considered more than a simple bandwagon effect or a managerial action mimicking other rms. e-Business announcements enhance the market value of rms and lead to the creation of value for the rms stockholders. Our main results are: 1. Capital markets respond positively to the eBusiness initiatives of rms, which leads to enhanced market value of the rms. The CAR (Cumulative Abnormal Return) for e-Business initiatives is 3.50% on the day of the event, and is 4.74% over the ve-day time window around the event date. 2. This positive effect is observed more strongly in KOSDAQ-listed rms than in KSE-listed rms. The difference in CAR (CAR KOSDAQ 2 CAR KSE ) of e-Business announcements is

4.5. Returns according to the e-Business initiative types

ANOVA5 was performed to test Hypothesis 5, and the analysis results are provided in Appendix B. In KSE, the P value, which indicates the difference in CAR according to the types of e-Business initiatives, is 0.021. This result is statistically signicant at the 0.05 level. Consequently, Hypothesis 5, that the abnormal returns are different depending on the types of e-Business initiatives, is accepted in KSE. Again, post hoc analysis 6 was performed to investigate in which type there is a difference. It was revealed that business expansion from non-Internet into e-Business is signicantly different from the other categories. We tested Hypothesis 5 for the rms in KOSDAQ with the same ANOVA analysis performed for the

5

This is to test if there is a difference between the mean for six days after the event day and the mean for ve days before the event day according to layers. 6 Duncans method was used in the post hoc analysis.

H.G. Lee et al. / Electronic Commerce Research and Applications 1 (2002) 21 56

53

2.93% on the day of the event and 4.36% over the ve-day time window. 3. Firms in KSE and KOSDAQ are classied into e-Business rm layers. For KSE, the abnormal returns attributable to e-Business initiatives are different according to the layer that rms belong to. In contrast, for KOSDAQ, the abnormal returns attributable to e-Business initiatives are not signicantly different according to the layer rms belong to. 4. In the case of KSE, positive effects of e-Business initiatives are observed more strongly in B2C rms than in B2B rms. The difference in CAR (CAR B2C 2 CAR B2B ) is 2.18% on the day of the event and 3.98% in the ve-day time window around the event date. For KOSDAQ, the positive effects of e-Business initiatives are not signicantly different between B2C rms and B2B rms. 5. In the case of KSE, the abnormal returns attributable to e-Business initiatives are observed to be different according to the activity type. For KOSDAQ, the abnormal returns attributable to e-Business initiatives are not signicantly different according to the activity type. In particular, the CAR of public announcements related to business expansion from nonInternet into e-Business is 8.58% on the day of the event, and records the highest gure at 14.77% in the ve-day time window around the event date. The effects of e-Business initiatives by rms have already been veried academically in the United States, and are also observed in KOSDAQ. However, this study highlights the different effects of e-Business initiatives according to capital market, layer, and type of e-Business activity, in addition to examining if there are actually effects of e-Business announcements. Furthermore, this study shows how e-Business rms, in a variety of circumstances, can take advantage of public announcements as a sound tool to manage their own stock prices according to their own conditions or opportunities. This study is different from that of Subramani and Walden [8] in three distinct aspects. First, the types of e-Business rms investigated and the rms eBusiness initiative types are dened in a broader

context. Second, e-Business initiatives are analyzed in two different capital markets (KSE and KOSDAQ) to examine if similar e-Business initiatives result in different rm values in the two markets. Third, the data collection periods are different. Taking these differences into account, there are some interesting comparisons between this research result and those of the previous study. First, as the US capital market, Korean capital markets react positively to rms announcements of e-Business initiatives, leading to a signicant enhancement of the rm value. Second, B2C e-Business initiatives have greater impacts on rm value than B2B eBusiness initiatives in the US capital market. However, this phenomenon was observed only in KSE in Korea. In KOSDAQ, B2B e-Business initiatives have greater impacts on rm value than B2C e-Business initiatives. Third, business expansion from non-Internet into e-Business initiatives have greater impacts on the market value of the rm than business expansion of an established e-Business rm initiatives in Korea. This is opposite to the ndings for the USA. From these differences, we can postulate that the capital market condition and investors responses to e-Business actions differ in the USA and Korea. In this paper, we have reported various e-Business announcements that could affect the market values of rms. Due to the fact that diverse e-Business initiatives were targeted, however, we could not obtain sufcient data samples for some e-Business initiative categories. For instance, the number of e-Business initiatives by rms of layer 2 in KSE is only 30. To gain greater insight from this study, it would be necessary to accumulate research ndings through continuous follow-up studies, with which it would be possible to compare and analyze the Dot Com Effect according to time ow.

Acknowledgements This work was supported by Korea Research Foundation Grant (KRF-2001-2-0770).

Appendix A. Abnormal return The event study methodology is based on the

54

H.G. Lee et al. / Electronic Commerce Research and Applications 1 (2002) 41 56

Appendix B. ANOVA results

Hypothesis Firm layers (Hypothesis 3) Initiative types (Hypothesis 5) Capital market KSE KOSDAQ KSE KOSDAQ Type III sum of squares 0.08910 0.00103 0.08835 0.08446 Df 3 3 2 2 Mean square 0.02970 0.00034 0.04418 0.04223 F value 2.863 0.134 3.958 1.337 Sig. 0.037** 0.940 0.021** 0.265

**Signicant at the 0.05 level.

Appendix C. Cumulative abnormal returns according to hypothesis

Hypothesis Time t25 Hypothesis 2 KSE KOSDAQ Hypothesis 3 KSE Layer 1 Layer 2 Layer 3 Layer 4 KOSDAQ Layer 1 Layer 2 Layer 3 Layer 4 Hypothesis 4 KSE B2B B2C KOSDAQ B2B B2C 0.33 (0.41) 0.77 (0.65) t24 0.69 (0.58) 1.33 (1.01) t23 0.59 (0.73) 2.07 (1.26) t22 0.94 (0.87) 2.47 (1.49) t21 1.16 (0.99) 3.16 (1.64) t 2.02 (1.10) 4.95 (1.78) t11 2.32 (1.21) 5.88 (1.95) t12 2.15 (1.29) 5.69 (2.15) t13 2.29 (1.35) 6.01 (2.30) t14 2.06 (1.35) 6.35 (2.46) t15 2.54 (1.43) 6.90 (2.60)

0.28 (0.67) 2 0.65 (1.67) 0.13 (1.15) 1.19 (0.99) 0.96 (1.02) 0.02 (1.31) 1.42 (1.15) 1.30 (2.34)

0.97 (0.89) 0.27 (1.72) 0.13 (2.04) 1.30 (1.47) 0.82 (1.53) 1.66 (1.97) 1.37 (2.04) 1.40 (3.25)

0.84 (1.11) 2 0.01 (2.49) 2 0.01 (2.12) 1.33 (1.99) 1.74 (1.90) 2.42 (2.51) 1.60 (2.12) 1.53 (3.47)

1.34 (1.32) 0.69 (3.55) 2 0.17 (2.56) 1.17 (2.14) 2.51 (2.21) 2.43 (3.05) 1.83 (2.56) 2.75 (4.28)

1.54 (1.52) 2 0.30 (3.74) 0.35 (3.06) 1.28 (2.55) 2.50 (2.39) 3.97 (3.47) 4.61 (3.06) 2.44 (4.75)

2.77 (1.65) 2 0.98 (4.51) 2.05 (3.37) 1.85 (2.80) 3.96 (2.69) 6.51 (3.65) 7.25 (3.37) 3.35 (4.78)

2.98 (1.77) 2 1.54 (4.72) 1.82 (3.90) 2.31 (3.27) 4.65 (2.97) 7.73 (4.01) 9.54 (3.90) 4.08 (5.32)

2.88 (1.87) 3.37 (4.86) 0.84 (4.34) 2.05 (3.39) 4.68 (3.28) 6.97 (4.59) 9.16 (4.34) 4.69 (5.55)

3.08 (2.04) 2 4.78 (5.23) 0.23 (4.32) 2.40 (3.18) 5.05 (3.50) 7.69 (4.85) 6.80 (4.32) 5.97 (6.12)

3.35 (2.07) 2 6.26 (4.76) 2 0.13 (4.18) 1.14 (3.18) 5.26 (3.74) 6.42 (4.86) 7.52 (4.18) 6.83 (7.25)

4.19 (2.21) 2 4.60 (5.53) 2 0.70 (3.91) 1.67 (3.45) 5.89 (3.93) 6.68 (5.26) 7.38 (3.91) 7.21 (7.24)

0.12 (0.68) 0.69 (0.75) 0.79 (1.27) 0.10 (1.14)

0.25 (0.97) 1.64 (1.05) 2.12 (1.92) 2 0.97 (1.75)

2 0.15 (1.25) 1.87 1.35 2.98 (2.32) 0.04 (2.20)

0.16 (1.44) 1.77 1.58 2.98 (2.67) 0.38 (2.67)

2 0.24 (1.68) 2.27 (1.68) 3.57 (2.89) 1.25 (2.95)

0.78 (1.87) 2.96 (1.81) 5.59 (3.19) 2.74 (3.23)

0.86 (2.17) 3.33 1.98 6.33 (3.54) 4.43 (3.54)

0.62 (2.34) 3.54 2.24 5.00 (3.98) 4.45 (3.88)

0.36 (2.39) 4.19 2.36 5.92 (4.23) 3.87 (4.16)

0.40 (2.39) 4.07 (2.40) 6.89 (4.48) 3.53 (4.51)

0.81 (2.49) 4.80 (2.43) 7.44 (4.64) 4.25 (4.79)

H.G. Lee et al. / Electronic Commerce Research and Applications 1 (2002) 21 56

55

Appendix C. Continued

Hypothesis Time t25 Hypothesis 5 KSE Alliance From non-Internet into e-Business Expansion of established e-Business KOSDAQ Alliance From non-Internet into e-Business Expansion of established e-Business t24 t23 t22 t21 t t11 t12 t13 t14 t15

0.70 (0.76) 0.01 (1.27) 0.52 (1.62) 0.17 (1.33) 1.61 (1.70) 2 0.64 (1.96)

0.45 (1.08) 1.19 (2.58) 1.12 (2.08) 2 0.05 (1.94) 4.45 (2.92) 2 0.48 (3.20)

0.51 (1.28) 1.35 (3.58) 1.37 (2.39) 0.60 (2.53) 5.28 (3.62) 0.72 (3.48)

0.89 (1.52) 1.98 (3.75) 0.96 (2.92) 1.02 (3.04) 6.25 (4.24) 0.77 (3.89)

1.70 (1.71) 2.59 (4.54) 0.89 (3.06) 1.77 (3.24) 7.06 (4.71) 0.88 (4.18)

1.98 (1.76) 3.66 (5.24) 2.18 (3.30) 4.86 (3.71) 8.58 (5.17) 1.32 (4.46)

1.36 (1.98) 6.45 (6.00) 2.29 (3.42) 6.03 (4.17) 11.13 (5.73) 2.36 (4.48)

1.26 (2.00) 8.45 (7.18) 1.42 (3.58) 5.64 (4.73) 12.11 (6.44) 2.79 (4.82)

1.68 (2.23) 9.75 (7.08) 0.78 (3.62) 5.95 (4.98) 12.87 (7.02) 2.68 (5.40)

1.15 (2.27) 8.31 (6.68) 1.37 (3.89) 5.65 (5.42) 13.31 (7.0) 1.92 (5.88)

1.55 (2.21) 8.23 (6.97) 2.09 (3.95) 6.43 (5.53) 14.77 (7.84) 0.57 (6.03)

Note: The upper gures in each cell present CARs, and the gures in parentheses present the critical values at a condence level of 95%. If the CAR is greater than the critical value in parentheses, we can say that CAR is signicant at the 95% condence level.

EMH (Efcient Market Hypothesis), which states that the capital market is an efcient mechanism to process information about the company. The logic of EMH is to evaluate the effects of a companys activities, not only for its current performance, but also for its predicted future performance, by processing information released in the capital market [28]. The basic assumption for this methodology is that if the public gains additional information about a companys activities which can impact on its present revenue and future revenue, the stock price will change sufciently to reect the current evaluation of the value of the company. The event study uses AR (Abnormal Return) in order to measure the effects of a companys activities on future cash ow. AR means that the actual return is different from normal market ow, and the return is created abnormally by specic events. Thus, AR represents a consensus measure of a rms future prot forecast by investors in the capital market. For example, if rm A initiated a new e-Business project B, investors might think that A would create additional cash ow with its new business. Let us suppose that, without the new project B, the stock price of company A is $10. If it went up to $11 on the day of rm As announcement, it can be stated that the effect of the e-Business initiative was $1 (10%), the difference between $11 and $10. This

10% increase in the market value of this rm is an AR. In order to calculate the effect caused by a specic event, we rst need to predict the companys stock price when the specic event does not happen, and then we can estimate the future stock price through a regression analysis based on past stock price data: R s , t 5 b0 1 b1 R m , t 1 s , t (A.1)

where t refers to time, s to the specic stock, and m to the market. Therefore, R s , t is the return of stock s during time t, and is calculated by R s , t 5 (Price s , t 2 Price s , t 2 1 ) / Price s , t 2 1 which gives stock s s rising rate in comparison with the stock price on the previous day (Price s , t is the price of stock s during t ). R m , t is the average return of stock in capital market m, s , t is the random error term for stock s during time t, and b0 and b1 are the coefcients that should be estimated. We select ve days before and after public announcements (for a total of 11 days) as an event window to observe the effect of e-Business initiatives (t 5 [25,5]). Here we set up t 5 [250, 2 6] as an estimation window to estimate the regression coefcients, and calculate estimates of the regression coefcients according to formula (A.1) using 45-day

56

H.G. Lee et al. / Electronic Commerce Research and Applications 1 (2002) 41 56 announcements on the market value of rms, Information Systems Research 12 (2) (2001) 135154. A. McWilliams, D. Siegel, Event studies in management research: theoretical and empirical issues, Academy of Management Journal 40 (3) (1997) 626657. G. Hamel, J. Sampler, The e-corporation: more than just web-based, its building a new industrial order, Fortune 138 (11) (1998) 8092. B. Wernerfelt, A resource-based view of the rm, Strategic Management Journal 5 (2) (1984) 171180. M.A. Peteraf, The cornerstones of competitive advantage: a resource-based view, Strategic Management Journal 14 (3) (1993) 179191. C.K. Prahalad, G. Hamel, The core competence of the corporation, Harvard Business Review May / June (1990) 7991. http: / / www.kse.or.kr. http: / / www.kosdaq.or.kr. Maeil Business Newspaper, Differences between KOSPI and KOSDAQ, Nov. 8, 1999. http: / / www.internetindicators.com / oct 1999.pdf. ] S. Yoon, Silicon valley report: gray prospect for Amazon.com, Maeil Business Newspaper, Oct. 30, 2000. H. Lee, Say it again, Steve, The Korea Economic Daily, Sept. 30, 1999. http: / / www.ecommerce.gov / emerging.htm. P. Hart, C. Saunders, Power and trust: critical factors in the adoption and use of electronic data interchange, Organization Science 8 (1) (1997) 2342. J. Park, J. Park, J. Cho (Eds.), Modern Financial Management, Dasan, Seoul, 2001, pp. 379380. http: / / kse.or.kr / upload / rule / rule014.zip. http: / / kse.or.kr / upload / rule / rule15.zip. V. Lane, R. Jacobson, Stock market reactions to brand extension announcements: the effects of brand attitude and familiarity, Journal of Marketing 59 (1) (1995) 6377. C.A. Mackinlay, Event studies in economics and nance, Journal of Economic Literature 35 (1997) 1339. http: / / www.internetindicators.com / archives.html. E. Fama, L. Fisher, M.C. Jensen, The adjustment of stock prices to new information, International Economic Review 10 (1) (1969) 121.

data. Abnormal Returns can be calculated from the difference between the expected return calculated according to the above procedure and the actual stock return as follows: AR s , t 5 R s , t 2 ( b0 1 b1 R m , t ) (A.2)

[9]

[10]

That is, when a specic companys actual return exceeds the gure expected by normal market ow on a specic day, this surplus is Abnormal Return. A specic rms CAR (Cumulative Abnormal Return) is the return that sums abnormal returns cumulatively at each time t during the event window. This is represented by the formula CAR s , t 5

[11] [12]

[13]

t 50

O AR

t

s,t

(A.3)

[14] [15] [16] [17] [18] [19] [20] [21]

For details of the event study methodology, refer to Ref. [9]. By calculating CAR, we can assess the impact of new e-Business initiatives on rm value.

References

[22] [1] [2] [3] [4] [5] [6] [7] [8] http: / / www.nua.ie / surveys. http: / / stat.nic.or.kr / sdata.html. Enable, Softbank Media, Seoul, Dec. 1999. A. Perkins, M. Perkins, The Internet Bubble, Gimm-Young, Seoul, 2000. T. Hoffman, Study: 85% of IT departments fail to meet business needs, Computerworld 33 (41) (1999). http: / / cnn.com / TECH / computing / 9905 / 31 / pockets.idg / index.html. Anonymous, Cost to build e-commerce site tops $1 million, Global Finance, New York, 13(7 / 8) (1999). M. Subramani, E. Walden, The impact of e-commerce [23] [24] [25]

[26] [27] [28]

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- SRS MastersDocument47 pagesSRS MastersSahil SuderaPas encore d'évaluation

- SRS TransactionsDocument151 pagesSRS TransactionsSahil SuderaPas encore d'évaluation

- FAO - Make Money by Growing Mushroom PDFDocument64 pagesFAO - Make Money by Growing Mushroom PDFT4urus-VegaPas encore d'évaluation

- Junior Software DeveloperDocument2 pagesJunior Software DeveloperSahil SuderaPas encore d'évaluation

- Sas InterviewDocument10 pagesSas InterviewArjun ReddyPas encore d'évaluation

- 10 Principles of EconomicsDocument5 pages10 Principles of EconomicsSahil Sudera100% (1)

- BIG DATA With OIL and GasDocument11 pagesBIG DATA With OIL and GasSahil SuderaPas encore d'évaluation

- Dsci Privacy SroDocument14 pagesDsci Privacy SroSahil SuderaPas encore d'évaluation

- Secure Electronic Transaction FinalDocument60 pagesSecure Electronic Transaction FinalSahil SuderaPas encore d'évaluation

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5794)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (895)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (344)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (399)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (588)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (266)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (73)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2259)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (120)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)

- GST Impact On E-CommerceDocument2 pagesGST Impact On E-CommercePAUL FREDERICK LLMPas encore d'évaluation

- #Designing The Uber Cash Experience - Uber Design PDFDocument5 pages#Designing The Uber Cash Experience - Uber Design PDFNaveen ThotapalliPas encore d'évaluation

- A Paradigm Shift 2Document11 pagesA Paradigm Shift 2Abhishek GhoshPas encore d'évaluation

- Saudagar Ecommerce Project BangladeshDocument13 pagesSaudagar Ecommerce Project BangladeshKamal ShovonPas encore d'évaluation

- E Commerce Business Plan ExampleDocument22 pagesE Commerce Business Plan Examplegshearod2u100% (2)

- CCG 2014 - Uae - Export and BusinessDocument108 pagesCCG 2014 - Uae - Export and BusinessPandey AmitPas encore d'évaluation

- IBEF Retail March 2021Document35 pagesIBEF Retail March 2021saacheeeePas encore d'évaluation

- Case StudyDocument13 pagesCase StudySanchit KaushalPas encore d'évaluation

- IBISWorld Industry Report Paper Bag & Disposable Plastic Product Wholesaling in The US 2018Document36 pagesIBISWorld Industry Report Paper Bag & Disposable Plastic Product Wholesaling in The US 2018uwybkpeyawxubbhxjyPas encore d'évaluation

- Chobani: The Falling First Mover: Jianan LiaoDocument5 pagesChobani: The Falling First Mover: Jianan Liaowofop34547Pas encore d'évaluation

- FDI GuidelinesDocument3 pagesFDI GuidelinesAnkur BhattPas encore d'évaluation

- 2023 01 20 23 09 42 PDFDocument13 pages2023 01 20 23 09 42 PDFSantosh Kumar GuptaPas encore d'évaluation

- E Transaction e Commerce AdamDocument19 pagesE Transaction e Commerce AdamLutchmee1112Pas encore d'évaluation

- Role of AI in RetailDocument46 pagesRole of AI in RetailpavanPas encore d'évaluation

- Walmart StakeholdersDocument20 pagesWalmart StakeholdersZareen RehanPas encore d'évaluation

- Chapter 29Document4 pagesChapter 29Siraj Ud-DoullaPas encore d'évaluation

- Nour Maher: Digital Marketing SpecialistDocument3 pagesNour Maher: Digital Marketing SpecialistNour MaherPas encore d'évaluation

- PPRO MEA and Africa Payments and Ecommerce Report 2022Document13 pagesPPRO MEA and Africa Payments and Ecommerce Report 2022omoakadesh01Pas encore d'évaluation

- E-Commerce and ManagementDocument11 pagesE-Commerce and ManagementRafiulPas encore d'évaluation

- 2022 Franchising Economic OutlookDocument36 pages2022 Franchising Economic OutlookNguyệt Nguyễn MinhPas encore d'évaluation

- bigbasket.comDocument32 pagesbigbasket.comNidhi Shah100% (3)

- 11 - Chapter 2Document40 pages11 - Chapter 2RoshiniPas encore d'évaluation

- 12 Rules For Life An Antidote To Chaos - PDF - Visper Zyraxes - Academia - EduDocument355 pages12 Rules For Life An Antidote To Chaos - PDF - Visper Zyraxes - Academia - EduРоман Гроян0% (34)

- E BankingDocument77 pagesE BankingDEEPAKPas encore d'évaluation

- DigitaL MarketingDocument26 pagesDigitaL MarketingNguyễn Quỳnh TrangPas encore d'évaluation

- Entrepreneurship: Jean-Baptiste SayDocument5 pagesEntrepreneurship: Jean-Baptiste SayPramod KumarPas encore d'évaluation

- W2-Part II (System Planning and Selection) Chapter 4-Identifying and Selecting Systems Development ProjectsDocument46 pagesW2-Part II (System Planning and Selection) Chapter 4-Identifying and Selecting Systems Development ProjectsAlissa Saphira PutriPas encore d'évaluation

- IS3223 Zara Case Study: Zara: IT For Fast FashionDocument27 pagesIS3223 Zara Case Study: Zara: IT For Fast FashionAlex NguyenPas encore d'évaluation

- Review of Related Literature and Studies: Online Reviews / Online Review RatingsDocument40 pagesReview of Related Literature and Studies: Online Reviews / Online Review RatingsAldrin Dela Cruz100% (1)

- Visa Annual ReportDocument164 pagesVisa Annual Reportcaoxx274Pas encore d'évaluation