Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Oslo 4

Transféré par

Ernest SagalaTitre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Oslo 4

Transféré par

Ernest SagalaDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

1 Professor William Tetley McGill Law Faculty Law 3644 Peel Street Montreal H3A 1W9 CANADA E-mail:

william.tetley@mcgill.ca Website: http://tetley.law.mcgill.ca

Scandinavian Institute of Maritime Profs. Rsg & Wilhelmsen Thursday, September 16, 2004 at 10:15 Tetley Lecture # 4

MARITIME LIENS AND CONFLICT OF LAWS (Page References to "ICL" refer to W. Tetley, "International Conflict of Laws", 1994, Chapter XVII, pp. 533-587. Page References to "MLC, 2 Ed." refer to W. Tetley, "Maritime Liens and Claims", 2 Ed., 1998) See also W. Tetley, International Maritime and Admiralty Law, 2002 at pp. 512-514 See http://tetley.law.mcgill.ca/conflicts/marliensconf.pdf I. Traditional Maritime Liens (ICL p. 539; MLC, 2 Ed., 59-60) 1) 2) 3) 4) 5) II. Arise with the claim. Follow the ship, even after a bona fide sale (except a judicial sale). Are secret -- need not be registered. Rank ahead of a ship mortgage. Are rights found in the codes of civilian jurisdictions ("privileges").

Ranking U.S. (ICL p. 540; MLC, 2 Ed., pp. 872-876) The American system of ranking is very original and out of step with most of the rest of the world. 1) Special legislative rights (of governments) (wreck removal; St. Lawrence Seaway and Panama Canal tolls and damages; rights of detention, removal and destruction for pollution; rights of forfeiture and sale for various federal statutory offences (e.g. drug trafficking, illegal immigration, etc.)); Custodia legis and some court costs (e.g. costs of seizure and judicial sale and attorney's fees); Preferred maritime liens: a) Wages of master and crew (including maintenance and cure), b) Salvage (including contract salvage) and general average (cargo against the ship) c) Maritime torts (e.g. collision), including personal injury and death, property damage and cargo tort liens; d) Longshoremen (individuals, not stevedore company).

2) 3)

2 U.S. contract maritime liens (necessaries) entered into before the filing of a U.S. preferred mortgage. This includes repairs, supply of bunkers, supplies, stevedores, towage, contract cargo damage liens and charterer's liens, etc. (and also including statutory maritime liens, e.g. for civil penalties); Preferred U.S. ship mortgage liens, as of the date of filing, as well as preferred ship mortgages on foreign ships whose mortgages have been guaranteed under Title XI of the Merchant Marine Act, 1936 (46 U.S. Code Appx. sect. 1101 et seq. at sect. 1271 et seq.); U.S. contract liens (necessaries) arising after the filing of the U.S. preferred ship mortgage (these are not preferred maritime liens); Foreign ship mortgages (not guaranteed under Title XI of the Merchant Marine Act, 1936); U.S. contract liens (other than necessaries) (e.g. contract cargo damage liens and charterers' liens) accruing after foreign ship mortgages; Unregistered (i.e. non-preferred) mortgages and perfected, non-maritime liens (including tax liens and other Government claims which are subordinate to maritime liens); state chattel mortgages and liens and liens for maritime attachment; and foreign contract liens (e.g. U.K. or Canadian statutory rights in rem). e)

4)

5) 6) 7) 8)

III.

Who May Bind in the U.S. (ICL p. 541; MLC, 2 Ed., pp. 602-605). In the U.S., the charterer (and not merely the shipowner) is presumed to have authority to bind the ship for necessaries. If the charterer does not have authority to bind the ship, the supplier of necessaries must be informed in advance. The supplier need not inquire if there is a prohibition of lien clause in the charterparty or in the ship mortgage.

IV.

Ranking in the U.K. and Canada (ICL pp. 539-540; MLC, 2 Ed., pp. 884-890 and 892-897) Ranking of liens and mortgages in the U.K. and Canada is more traditional than in the U.S. and is as follows: 1) 2) 3) Special legislative rights; Court costs (e.g. costs of seizure and judicial sale) and custodia legis; Maritime liens: salvage, damage (e.g. collision), wages. Ship mortgages (registered); Necessaries give statutory rights in rem: a) Do not follow the ship when sold, b) Only owner or beneficial owner may bind the ship in Canada for statutory rights in rem. c) In U.K., the owner, beneficial owner or demise charterer may bind the ship for statutory rights in rem. d) For bunkers, repairs, supplies, towage, etc.

4) 5)

3 e) There is no statutory right in rem for stevedores in the U.K., but there is in Canada. f) Necessaries in Canada extend to goods and materials as well as services and insurance. Necessaries in the U.K. extend to goods and materials. g) Statutory rights in rem arise in U.K. upon issue of the writ (now called an in rem claim form). h) Statutory rights in rem arise in Canada upon arrest of the ship. V. Four Major Decisions Four major decisions are noted here to illustrate how conflicts of maritime liens and mortgages have been solved. 1) Ioannis Daskalelis [1974] S.C.R. 1248, [1974] 1 Lloyd's Rep. 174, 1973 AMC 176 (Supr. Ct. of Can.) (ICL pp. 566-567). a) Greek ship has a Greek mortgage, i.e. foreign mortgage. b) Ship is repaired in Todd Shipyard, Brooklyn. c) Ship sails, avoiding possessory lien and U.S. maritime lien for d) e) f) Ship avoids arrest in U.S. on orders of mortgagee. Ship arrested in Canada. Supreme Court of Canada recognizes a foreign lien (the U.S. maritime lien for repairs) as a maritime lien, although no such maritime lien exists in Canadian law. Ranks the U.S. lien procedurally by Canadian lex fori, ahead of the mortgage.

repairs.

2)

Halcyon Isle [1980] 2 Lloyd's Rep. 325, 1980 AMC 1221, [1981] A.C. 221 (P.C.) (ICL pp. 570-573). a) b) c) British ship has a British mortgage (mortgage not recorded). Ship enters the same Todd Shipyard in Brooklyn and is repaired. Ship sails and avoids possessory lien and U.S. maritime lien for Mortgage is registered. Ship is arrested in Singapore. Privy Council applies the lex fori (3-2) and does not recognize the

repairs. d) e) f) lien. In a strong dissenting decision, Lords Salmon and Scarman held as follows: "A maritime lien is a right of property given by way of security for a maritime claim. If the Admiralty Court has, as in the present case, jurisdiction to entertain the claim, it will not disregard the lien. A maritime lien validly conferred by the lex loci is as much part of the claim as is a mortgage similarly valid by the lex loci. Each is a limited right of property securing the claim. The lien travels with the claim, as does the mortgage: and the claim travels with the

4 ship. It would be a denial of history and principle, in the present chaos of the law of the sea governing the recognition and priority of maritime liens and mortgages, to refuse the aid of private international law." (Emphasis added) ([1981] A.C. 221 at p. 250, [1980] 2 Lloyd's Rep. 325 at p. 339, 1980 AMC 1221 at p. 1249). They also held: "The question is - does English law, in circumstances such as these, recognise the maritime lien created by the law of the United States of America, i.e. the lex loci contractus where no such lien exists by its own internal law? In our view the balance of authorities, the comity of nations, private international law and natural justice all answer this question in the affirmative. If this be correct then English law (the lex fori) gives the maritime lien created by the lex loci contractus precedence over the mortgagees' mortgage. If it were otherwise, injustice would prevail. The ship-repairers would be deprived of their maritime lien, valid as it appeared to be throughout the world, and without which they would obviously never have allowed the ship to sail away without paying a dollar for the important repairs upon which the ship-repairers had spent a great deal of time and money and from which the mortgagees obtained substantial advantages." ([1981] A.C. 221 at pp. 246-247, [1980] 2 Lloyd's Rep. 325 at pp. 336-337, 1980 AMC 1221 at p. 1244). 3) Ocean Ship Supply v. Leah 729 F. 2d 971, 1984 AMC 2089 (4 Cir. 1984) (ICL p. 549). a) b) c) d) e) 4) Greek ship obtains necessaries in Quebec City January 1, 1980. August 1980, ship sold and registered in Honduras. Ship arrested in Charleston S.C. American Court recognizes the statutory right in rem of Canada and that it is not a maritime lien and is lost with the sale of the ship. Arrest and claim dismissed.

Marlex Petroleum v. Har Rai [1984] 2 F.C. 345, 1984 AMC 1649 (Fed. Ct. of Appeal); upheld [1987] 1 S.C.R. 57 (Supreme Ct. of Canada) (ICL pp. 567-568). a) b) c) d) e) Bunkers supplied in Los Angeles to a time chartered vessel flying the Indian flag. Bunkers not ordered by owner but supplier did not know of charterer's lack of authority (former 46 U.S. Code Appx. sect. 973, now 46 U.S. Code 31341 and 31342). Vessel arrested in Vancouver. U.S. maritime lien was recognized in Canada. Proceedings also in personam against the owner, but were dismissed.

VI.

The New Zealand Experience (ICL 576-578) In The Betty Ott v. General Bills Ltd. [1992] 1 N.Z.L.R. 655, the New Zealand Court of Appeal held that on the basis of The Halcyon Isle (supra) (by which the Court was presumably bound), it could not recognize a foreign ship mortgage duly registered in Australia as equivalent to a New Zealand ship mortgage, because the mortgage was not registered in New Zealand. This was so, despite the fact that Australian ship mortgages are registered under terms and conditions very similar to those governing ship mortgage registration in New Zealand. The Australian mortgage was therefore held subordinate under New Zealand ranking to an equitable charge resulting from a debenture issue. The decision points up the absurd results to which The Halcyon Isle, as a general principle, can lead, as the minority in that decision foresaw.

VII.

Australia In Morlines Maritime Agency Ltd. & Ors v. The Skulptor Vuchetich 1997 AMC 1727, the Federal Court of Australia decided to follow The Halcyon Isle.

VIII.

South Africa The Halcyon Isle was followed in: 1) The Andrico Unity 1989 (4) S.A. 325, 1989 AMC 1561 (S. African Supr. Ct., App. Div.), upholding 1987 (3) S.A. 794 (Cape of Good Hope Provincial Div.) (ICL p. 574); Brady-Hamilton Stevedoring v. Kalantiao 1989 (4) S.A. 355, 1989 AMC 1597 (S. African Supr. Ct., App. Div.) (ICL pp. 574-575); Banco Exterior de Espana S.A. v. Government of Namibia 1999 (2) S.A. 434 (Namibia High Court).

2) 3)

IX.

Cyprus The Halcyon Isle was followed in: Hassanein v. The Hellenic Island [1989] 1 C.L.R. 406 (Cyprus Supr. Ct.) (ICL pp. 575-576).

X.

Singapore Singapore followed The Halcyon Isle in The Andres Bonifacio (1993) 3 S.L.R. 521 (Singapore C.A.). The Halcyon Isle has also been invoked to establish that the categories of maritime liens in Singapore's maritime law are the same as those at English

6 maritime law. See The Ohm Mariana ex Peony (1992) 2 S.L.R. 623 (Singapore High Ct.). No foreign maritime lien claim was asserted in this case, however. XI. Malaysia The Malaysian High Court has held, on the basis of The Halcyon Isle, that Malaysia, as well as Singapore, have the same (English) admiralty jurisdiction and substantive maritime law. See Ocean Grain Shipping Pte Ltd. v. The Dong Nai (1996) 4 MLJ 454 (High Ct. - Johor Bahru). The Halcyon Isle has also been cited as authority for the categories of maritime liens in Malaysia. See The Ocean Jade (1991) 2 MLJ 385 (Malaysian High Ct.). No foreign maritime lien claim was asserted in the latter case, however. XII. Israel The Supreme Court of Israel, in The Nadja S. (Griffin Corp. v. Koor Sachar) 44 (3) P.D. 45 (1990), was a decision in which each of the three judges took a different position. The President of the Supreme Court held that the foreign maritime lien for necessaries was a substantive right which should be governed by either the lex situs (the law of the place where the necessaries were supplied) or the lex loci contractus (the law of the place of the contract), with priorities governed by the lex fori (the law of the forum). A second judge held that both recognition and priorities should be governed by the lex causae, and that if those laws differed, the lex fori should govern priorities. The third judge held, as did the majority of the Privy Council in The Halcyon Isle, that the lex fori should apply to both recognition and ranking. (ICL pp. 579-580). XIII. National Legislation China The People's Republic of China applies the law of the forum to maritime liens under art. 272 of its Maritime Code 1993 (ICL p. 584). Sweden Under the Swedish Maritime Code 1994, chap. 3, sect. 51, Swedish law governs maritime liens and rights of retention in a vessel "referred to in this chapter" (i.e. a Swedish-registered vessel) when the maritime lien or right of retention is invoked before a "Swedish Authority". In the case of other vessels, the effect of a maritime lien, right of retention or similar right is determined by the law of the vessel's registry. Nevertheless, such right ranks after any maritime lien or right of retention provided for in chap.

7 3 and after any hypothec (ship mortgage) complying with the Liens and Mortgages Convention 1967 (to which Sweden is a party). Greece The Greek Code of Private Maritime Law at art. 9 subjects foreign maritime liens and claims to the law of the ship's flag (ICL pp. 582-583). The Netherlands The Netherlands Conflict of Maritime Laws Act, 1993 at art. 3(2) also provides that the law of the ship's registry (flag) governs the question of whether a maritime claim is protected by a lien, as well as the scope and consequences of such a lien. Moreover, even if the lien exists under the law of the flag, it will outrank a mortgage only if an equivalent lien would have done so in Dutch law. (ICL pp. 583-584). Reliance on the law of the flag is out of place in our contemporary world of flags of convenience, double-flagging, and flagging out, where the flag is only one contact (or connecting factor) among others, and should by no means be seen as a definitive indication of the properly applicable law of foreign maritime liens or claims against ships. XIV. The Rome Convention, 1980 The Rome Convention (on conflict of law in contract) is binding on the European Union and thus in the United Kingdom since April 1, 1991. If suit were taken today in the U.K. upon the arrest of ship in the U.K. under the same events as the Halcyon Isle (i.e. repair of a ship in Brooklyn, U.S.A. under a U.S. contract calling for U.S. law), the U.K. court would apply U.S. law. This is because of arts. 3 or 4 (express or implied choice); arts. 1(2)(h), 10(1)(c) and 14 (procedure); and art. 10(1)(c) (consequences of a breach). Thus much of the air has been taken out of the Halcyon Isle balloon. The law of the flag, in respect of contractual liens, seems inconsistent with the basic conflict rules of arts. 3 and 4 of the Rome Convention 1980, which call for the law expressly or implicitly chosen by the parties or the law having the closest connection with the contract. (ICL pp. 580-581). XV. International Convention on Maritime Liens & Mortgages, 1993 The 1993 Convention is not in force and is unlikely to be, because its authors (against strong advice) did not take into consideration special legislative rights of various nations (MLC, 2 Ed., p. 214). XVI. Equity

There can be gross inequities in respect of ship mortgages and maritime liens without uniform international law on the subject. Similarly, there are bound to be other commercial and maritime inequities without international uniformity in conflicts of law. XVII. Conclusions The world needs a proper convention on international maritime liens and mortgages and as well as a proper international convention on conflict of laws. Oslo Lecture # 4 wt/July 14, 2004

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (890)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (587)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (344)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (119)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (399)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2219)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (73)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- Friendzone Annihilation Formula (E-Book) PDFDocument38 pagesFriendzone Annihilation Formula (E-Book) PDFsamuel vincent50% (4)

- Statement of Claim by Kawartha Nishnawbe Mississaugas of Burleigh FallsDocument63 pagesStatement of Claim by Kawartha Nishnawbe Mississaugas of Burleigh FallsPeterborough ExaminerPas encore d'évaluation

- Woolridge V SumnerDocument30 pagesWoolridge V SumnerBernice Purugganan AresPas encore d'évaluation

- Born in Blood and Fire Introchapter 1Document20 pagesBorn in Blood and Fire Introchapter 1awm8m7478100% (2)

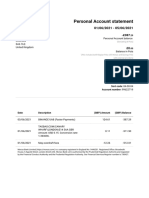

- Personal Account Statement: Sean William CutlerDocument2 pagesPersonal Account Statement: Sean William CutlerSean CutlerPas encore d'évaluation

- WH - FAQ - Chaoszwerge Errata PDFDocument2 pagesWH - FAQ - Chaoszwerge Errata PDFCarsten ScholzPas encore d'évaluation

- United States Court of Appeals, First CircuitDocument8 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals, First CircuitScribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- Settlement Agreement in Leiterman v. JohnsonDocument11 pagesSettlement Agreement in Leiterman v. JohnsonNorthern District of California Blog0% (1)

- Shirley A. Duberry v. Postmaster General, 11th Cir. (2016)Document6 pagesShirley A. Duberry v. Postmaster General, 11th Cir. (2016)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- Santos v. LlamasDocument2 pagesSantos v. Llamasjovani emaPas encore d'évaluation

- Virginia Workers' Compensation Claim Surgery Approval DisputeDocument10 pagesVirginia Workers' Compensation Claim Surgery Approval Disputedbircs777Pas encore d'évaluation

- Haines Man Sentenced To 20 Years in Prison For Sexually Exploiting MinorsDocument2 pagesHaines Man Sentenced To 20 Years in Prison For Sexually Exploiting MinorsAlaska's News SourcePas encore d'évaluation

- Themes of A Passage To India: Culture ClashDocument6 pagesThemes of A Passage To India: Culture ClashGabriela Macarei100% (4)

- 083-Chavez v. JBC G.R. No. 202242 April 16, 2013Document18 pages083-Chavez v. JBC G.R. No. 202242 April 16, 2013Eunice ChavezPas encore d'évaluation

- Dang Vang v. Vang Xiong X. Toyed, 944 F. 2d 476 - Court of Appeals, 9th Circuit 1991Document7 pagesDang Vang v. Vang Xiong X. Toyed, 944 F. 2d 476 - Court of Appeals, 9th Circuit 1991bbcourtPas encore d'évaluation

- Aphra BehanDocument4 pagesAphra Behansushila khileryPas encore d'évaluation

- Azuela Vs CADocument7 pagesAzuela Vs CAJoel Longos100% (1)

- X 018 CurDocument4 pagesX 018 CurdedogPas encore d'évaluation

- Peak Ebpp DescriptionDocument4 pagesPeak Ebpp Descriptionapi-259241412Pas encore d'évaluation

- Asia Pacific Chartering Inc. vs. Farolan G.R. No.151370Document2 pagesAsia Pacific Chartering Inc. vs. Farolan G.R. No.151370rebellefleurmePas encore d'évaluation

- When Buddhists Attack Mann 1Document41 pagesWhen Buddhists Attack Mann 1Helio LaureanoPas encore d'évaluation

- Shockwave (WFC) - Transformers WikiDocument13 pagesShockwave (WFC) - Transformers Wikiamos_evaPas encore d'évaluation

- Arya Samaj Mandir Provides Inter - Religion Marriage Registration and Cerificate SupportDocument2 pagesArya Samaj Mandir Provides Inter - Religion Marriage Registration and Cerificate SupportaryasamajmandirmarriagePas encore d'évaluation

- Headway: Clil WorksheetsDocument2 pagesHeadway: Clil WorksheetsAmina VeladžićPas encore d'évaluation

- Raga Vartma CandrikaDocument26 pagesRaga Vartma CandrikaЕвгений ЗиборовPas encore d'évaluation

- Private Criminal Complaint v. Eric Calhoun & Alley Kat Bar With Lancaster City Police Response To Scene - September 22, 2007Document6 pagesPrivate Criminal Complaint v. Eric Calhoun & Alley Kat Bar With Lancaster City Police Response To Scene - September 22, 2007Stan J. CaterbonePas encore d'évaluation

- Holy See Wins Sovereign Immunity CaseDocument2 pagesHoly See Wins Sovereign Immunity CaseRochelle Ann ReyesPas encore d'évaluation

- The Normative Implications of Article 35 of the FDRE ConstitutionDocument23 pagesThe Normative Implications of Article 35 of the FDRE ConstitutionAbera AbebePas encore d'évaluation

- Jewish TravelerDocument60 pagesJewish TravelerAna HiršlPas encore d'évaluation