Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

A Senior Thesis in Just War Theory

Transféré par

brianscottgCopyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

A Senior Thesis in Just War Theory

Transféré par

brianscottgDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

1 Brian S.

Gallagher

A Senior Thesis in Just War Theory

Whither Jus Post Bellum?

Brian S. Gallagher

I.

In practice, the inflation of ends is probably

inevitable unless it is barred by considerations of

justice itself. Michael Walzer, Just and Unjust Wars

1

Introducing J us Post Bellum

The above pronouncement of Walzers, made in the context of his discussion of just

settlements and the handling of the North Korean regime near the Korean Wars end, is notable

for its concise illustration of how the principles of just war theorythough separated into

different componentsnevertheless impact each other. There is first the ad bellum stock of

1

Michael Walzer, Just and Unjust Wars (New York, New York: Basic Books, 2006), p. 120.

In abstract, the argument of this thesis will proceed in

two sections. The first will discuss the grounding for the

conceptual structure of Just War Theory; specifically,

its traditional partitioning into two components, ad

bellum and in belloalong with the relatively recent

suggested addition of a third componentjus post

bellum. The second section, in concluding the thesis,

will argue for a revised structural conception of the

theory that has formal and substantive implications for

the normative content of a postwar, peace building

ethic.

2 Brian S. Gallagher

principles, which has been stated variously but at its core consists in the criteria of i) just cause,

ii) necessity, iii) proportionality, and iv) likelihood of success. In fulfilling these criteria, it is

held that a state may justly resort to war. The most obvious cases in which resort to such

violence is justified is in self- or in other-defense against aggression by another state, and the

justice of warring for these purposes shapes the political and military aims sought at the wars

conclusion. When North Korea invaded its Southern neighbor, then, a just cause to aid the latter

arose, and the United States (with UN authorization) took it upon itself to carry it out. The justice

the US would initially plan to exact, however, was hardly far-reaching, committed only to

pushing the N. Korean forces back to their side of the 38

th

parallel in order to restore the status

quo ante bellumoriginally there were no aims of trials and punishments, or of regime change

and rehabilitation; there was only the aim of returning things to how they were shortly before

war broke out. This limited military end had the implication that, politically, the US would aim

short of regime change and leave the aggressor state as it was.

This pursuit of limited justicelimited because of its contentedness with merely

halting the aggression of N. Korea rather than bringing them to account for it and preventing its

future expressioncorrespondingly limits the sort of attacks against N. Korea that are militarily

appropriate. The purpose of the in bello principle of proportionality is to constrain justified

military tactics to those which are necessary for, in this case, pushing the N. Korean army back

across the 38

th

parallel. As Walzer goes on to illustrate, however, this end was not held

constant; rather, in the course of the military campaign, it inflated. Warren Austin, the US

Ambassador to the UN, told the latter that the forces of N. Korea should not be permitted to

take refuge behind the 38

th

parallel because that would recreate the threat to peace

2

The just

cause hadnt changedit was still the protection of the South Koreansbut the reach of its

2

Quoted in Walzer, Just and Unjust Wars, p. 118.

3 Brian S. Gallagher

justice had, namely in Austins apparent contention that restoring the status quo ante bellum

would be strategically, if not also morally, wrongheaded. But in crossing that dividing line

between the warring Koreas, America, Walzer remarks, also took on a more radical purpose,

and goes on to say that, in so doing, it took on the goal of unifying Korea into a democracy by

force, which would require of them not limited attacks within the borders of North Korea, but

the conquest of the entire country.

3

With this expansion of ends, new military means are

made proportional, gauged in relation to a more thorough leveling of the N. Korean armed

forces. And with territorial and military conquest comes the stage and period of occupation, an

occasional phase of war that functions to maintain the security of a territory more than to take it

over.

This change in military emphasis is important because it marks a significant transition in

the occupying states political and military role in relation to the livelihood of the civilians in the

society of which they occupy. This role, as a peculiar activity conducted in wars aftermath, has

so far not received as rich normative theorization as the other aspects of warfighting

particularly the initiation of war and its conduct, or the component phases of ad bellum and in

bellobut it has of late generated lots of constructive and speculative literature.

4

In these fresh

discussions of justice after war, the 2003 US invasion and subsequent occupation of Iraq proves

3

Ibid., p. 118.

4

Brian Orend is jus post bellums most prolific advocate. His arguments are brought together in his The Morality of

War (Peterborough, ON: Broadview Press, 2006), e.g. at 1920 and chapters 6 and 7. For his most recent statement

of the theory, see Jus Post Bellum: The Perspective of a Just War Theorist, Leiden Journal of International Law

20, no. 3 (2007): 57191. Other supporters of jus post bellum include Gary Bass, Jus Post Bellum, Philosophy and

Public Affairs 32, no. 4 (2004): 384410; Richard P. DiMeglio, The Evolution of the Just War Tradition: Defining

Jus Post Bellum, Military Law Review 186 (2005): 11663; Robert E. Williams and Dan Caldwell, Jus Post

Bellum: Just War Theory and the Principle of Just Peace, International Studies Perspectives 7, no.4 (2006): 309

20; Patrick Hayden, Security beyond the State: Cosmopolitanism, Peace and the Role of Just War Theory in Just

War Theory: A Reappraisal, ed. Mark Evans (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2005), 15776; and Moral

Theory and the Idea of a Just War in Evans (ed.), Just War Theory, 121, at 13, 1920. Carsten Stahn, in Jus ad

Bellum, Jus in Bello Jus post Bellum? Rethinking the Conception of the Law of Armed Force, European

Journal of International Law 17, no. 5 (2006): 92143 theorizes jus post bellum from the perspective of

international law.

4 Brian S. Gallagher

itself as the case which most animates critical reflection on the sorts of rights, responsibilities,

and obligations that come into play in the tenuous relation and strenuous situation that is the

reconstitution and rehabilitation of a war-torn society. Jus post bellumas a component of the

theory of waging just warclaims itself rightly equipped to grasp the ethical quandaries that

follow, for instance, from the military conquest of the Iraqi state, the dismantling of its political

and legal constitution, and the international stewardship required to see the downtrodden

population stand up once again. Necessarily involved in these issues are concerns about the value

of sovereignty and territorial integrity, the meaning of just peace and just society, and the

procedures which bring these outcomes aboutlike war crimes trials, compulsory compensation,

demilitarization, and/or truth commissions and apologies. If war is meant to bring about a better

state of peace and prevailing justice than was present before

5

, then we must essentially be talking

about the exercise of healing social and political relations and capabilities once war has been

terminated. The question I would like to explore, then, is whether the ethical framework of just

war theory can adequately provide normative guidance in this broad moral activity.

The Purpose and Scope of Just War Theory

In his 1977 preface to Just and Unjust Wars, Walzer describes just war theory as a

comprehensive view of war as a human activity and a more or less systematic moral doctrine,

which sometimes, but not always, overlaps with established legal doctrine.

6

That was my

italicization, the reason for which was to highlight and emphasize a very important point about

5

Walzer, in Just and Unjust Wars p. 121, quotes from Liddell Harts Strategy p. 338: The object in war is a better

state of peace. Walzer goes on to describe it as a condition that is relatively safer and more secure for ordinary

men and women and for their domestic self-determinations.

6

Ibid., p. xxi.

5 Brian S. Gallagher

what I contend Just War Theory is for: to articulate a set of substantive precepts and procedural

standards that regulate the peculiarly massive and violent exercise of state-sanctioned

warfighting.

This purpose has implications for how the divisions of just war theory should be

interpreted; namely, I shall argue that jus ad bellum, jus in bello, (and a third component I will

soon introduce) should be understood as sets of principles and procedures that govern how

particular and distinct aspects of fighting a war should be practiced.

At odds with understanding war in this way is Brian Orend. His conceptual

characterization of the components of Just War Theory is temporal. Conceptually, he says,

war has three phases: beginning, middle, and end.

7

To the contrary, I hold that war has three

sub-practices: the initiation of war, its execution, and its termination.

Revising the theory of just war into this formulation has its advantages. In the first place,

abandoning the view of war as primarily a time period of violence between states allows for a

more coherent conception of Just War Theory, because doing so brings into tighter focus the

activities of warfare that require justification. Secondlyand consequentlythe issue of Just

War Theorys incompleteness, due to its alleged silence on the question of how wars should end,

is solved. Not, however, in the way that Orend thinks he has solved it with his addition of jus

post bellum, an addition thatfrom the beginning of his introduction of itconflates two

importantly distinct activities: that of ending, or terminating, a war justly; and that of justly

exercising and carrying out post-war rights, responsibilities, and obligations.

For helping me to see this point, I must thank Seth Lazar, whose working paper on this subject I read on the

internet but which was, as it itself stated, not for citation.

7

Brian Orend, The Morality of War, p. 160.

6 Brian S. Gallagher

All too often, still today, begins Orend, just war theorists stick with the first two

categoriesof jus ad bellum and jus in belloand pretend that is all they have to talk about.

International law, sadly, has joined just war theory regarding its relative silence on proper war

termination [my italics].

8

Proper war terminationisnt this clearly distinct from, say, the

need to impose short-term, direct military occupation over a shattered society

9

? In his account

of jus post bellum, Orend clumps these practices together and expects the same set of normative

principles to guide the practice of both. But the former concerns the justice of ending a war,

while the latter concerns what justice might require after the war has ended. Here and in other

places, Orend makes the mistake of believing that both these moral inquiries can be answered by

the same ethical criterianamely the precepts and procedures outlined in just war theory.

His motivation for this is clear. Orend thinks that if the theory cannot speak to both of

these ethical issues, then it will fail to be as robust as it should and succumb to a sharp,

potentially devastating objection from both realists and pacifists; namely, that just war theory

fails to consider war in a deep enough, systematic enough kind of way. Continuing, he says,

with its hitherto narrow [my italics] focusit does not ultimately care why war breaks out

and does not seek to improve things after wars end so as to make the international system more

peaceful over the long term [my italics].

10

Of course, I do not share these fears. As I have stated

above, it is not the task of just war theory to provide ethical guidance on the very broad goal of

making the international order more peaceful in the future, and this should be obvious by the

name of the theory. Rather, just war theory does have a narrow focus, the focus of morally

regulating warfare in the three practices I mentionedits initiation, execution, and termination.

With this schema, the theory is complete and coherent and there is no need to supply it further.

8

Ibid., p. 160.

9

Ibid., p. 162.

10

Ibid., p. 160.

7 Brian S. Gallagher

The task of theorizing what justice requires in the aftermath of war must be met by normative

criteria outside of just war theory (which I will discuss in the second section).

The idea of adding to just war theory the component of just war termination comes from

Darrell Moellendorf.

11

He terms it jus ex bello, whichthough philosophically unimportantis

a bit strange since the Latin translates vaguely to the right of war.

12

To be more specific it

should be termed jus terminare bellum, or the right to terminate war. This, as Ive been hinting

to, is the proper third component of normative criteria to add to complete the theory. (Before

sketching out these criteria, I do not want to go without mentioning an oddity of jus post bellum

that makes its inclusion to the theory more suspicious and less plausible. It means justice after

war and claims to render the just war theory conceptually complete; ironically, however, it

incriminates itself by implying that yet another category needs to be included in virtue of

symmetryif the theory requires an account of justice after war, must it not also require one of

justice before war, too? This, of course, is a sort of reductio ad absurdum; my point is that,

before war, the account of justice we use to evaluate our conduct in global affairs will just be our

broad international political morality, grounded in universal human rights. This could be

cosmopolitanism or something else; but whatever it ends up being, just as it would be our

normative guide before war, so, too, would it be our guide after war (more on this in the second

section). Thus, in assessing justice before and after war, calling upon the guidance of just war

theory does not seem sensible.)

*

Jus terminare bellum, my phrasing for the criteria of just war termination, is concerned

with the question of whether, and how, a war should be brought to an end. Moellendorf considers

11

Darrell Moellendorf, Jus ex Bello, The Journal of Political Philosophy 16, no. 2 (2008), pp. 123 136.

12

I am here relying on Google Translate.

*

I again credit Seth Lazar for bearing out this point.

8 Brian S. Gallagher

this to be a possible fourth set of criteriaalongside jus post bellumwhich he rightly describes

as the arrangements that should come to pass upon wars end.

13

Though he apparently regards

them as compatible, my thesis will not touch upon how he might think this is so; all I need is his

account of just war termination and how it is distinguished from and connects with just initiation

and execution, which I will now lay out.

To show that the criteria of jus ad bellum (the same criteria I listed at the outset) is

neither sufficient nor necessary for determining whether morally a war should be terminated

once it has begun,

14

he begins by making an argument for the first claim that, even if a war

begins completely just, it is still possible for its termination short of victory to be morally

required. Reflecting on the principle of likelihood of success bears this out. Once started, a war

whose success seemed probablegiven the relevant facts on an objective reading, or the

available evidence on a subjective onecould still turn out, in the course of the military

campaign, to be unlikely to succeed; and if its unlikely to succeed, then theres a strong reason

for the wars continuation to be unjust. To put it another way, because the judgment of whether

the initiation of war satisfies the ad bellum criteria is fallible, the question of whether the war is

likely to succeed must be constantly reassessed during the course of the war. This is what any

reasonable commitment to the justice of war requires.

15

Next, and more controversially,

Moellendorf defends the claim that it could very well be morally required to continue a war

which was initiated unjustly, not satisfying all of the ad bellum criteria. This, its important to

note, flies in the face of Orends proclamation that failure to meet jus ad bellum results in

automatic failure to meet jus in bello and just post bellum. But for Moellendorf, such positive

shifts in the justice of a war are demonstrably illustrated with the case of Iraq: If grave

13

Moellendorf, Jus ex Bello, p. 123.

14

Ibid., p. 124.

15

Ibid., pp. 125 126.

9 Brian S. Gallagher

humanitarian danger provides just cause for intervention, then surely it justifies continuing a war,

even if the war originally did not satisfy the principle of just cause.

16

He does not share Orends

conviction that once youre an aggressor in war, everything is lost to you, morally.

17

This point of divergence is extremely interesting because it leads to a fundamental

question about the nature of a just war: namely, under what conditions does the overall justice of

a war change? On Orends view, there is no redemption for a war that starts out unjustlyjus

ad bellum failure corrupts the whole resulting project. Referring to Iraq, he says, even if it

all turns out well, that still will not make the original decision just; it will simply mean that the

post-war situation was not as bad as it might have been.

18

Orend, admittedly, is working to

construct what he contends is an ideal conception of post-war justice; and thus, no matter

how much continuing a war might remedy injustice, if it starts unjust it stays unjust.

19

But this is

unhelpful and a weakness in Orends account, for there is rarely ever a war which is ideally just,

and in his attempt to articulate what that might be, he at the most blinds himself to an entire

component of just war theory, or at the least hastily passes over it. For he does, in a brief

passage, come close to hitting upon the central notion of jus terminare bellum when he

speculates on the bedrock limit to the justified continuance of a just war [my italics]

20

specifically, since all just causes are grounded on the principle of rights vindication (a just cause

is just because it vindicates violated rights) no war can justifiably continue once the violated

rights that grounded the just cause have been vindicated by the war. In other words, the principle

of rights vindication entails the transformation of a just war into an unjust one if it devolves into

something like a Crusade, where the goal of the war is no longer rights vindication but rather

16

Moellendorf, Jus ex Bello, p. 128.

17

Orend, The Morality of War, p. 162.

18

Ibid., p. 195.

19

Ibid., p. 163.

20

Ibid., p. 163.

10 Brian S. Gallagher

conquest or annihilation. But, as I said, this is just to pass over terminare bellum; to give it

proper treatment, as Moellendorf does, one must investigate the conditions under which even an

unjust war may be justifiably continuedand if it may, it can no longer be regarded as unjust.

But the justice of the original decision to go to war, for Orend, is very important; and

Moellendorf acknowledges that his relative lenience in this respect might constitute a reasonable

objection to his account. Still, he says, in the event that a war that was unjust to initiate becomes

just to continue, the case for continuing is based in part on the danger of compounding the initial

injustice by ending a war when good reason has developed to pursue it.

21

If, according to

Orend, the warstarted unjustlyis irredeemably unjust, should the good reason to continue

with the war be ignored and allowed pass away? What if a pressing cause for humanitarian

intervention cries out for attention, as it surely did in Iraq? He concedes that we could sayif

American-led reconstruction worksthat Iraq is better off but that the USs war, despite being

successful, cannot be fully just because of its unjust initiation. Justice for Orend, then, is a

matter of degree, as he bears out explicitly when he says, the less just your start of war, the

fewer your rights in the post-war phase.

22

But how, given his conceptual and normative

resources presented thus far, would he be able to say that the US should continue with the war

given that it started unjustly? There seems to be no moral principle which Orend can call upon to

support the bettering of the Iraqi state if such action would mean continuing an unjustly initiated

war. This is a consequence of his account lacking treatment of jus terminare bellum, a

consequence with which Moellendorf is not inflicted because he allows for the morality of a war

to shift in response to new and pressing causes arising from the vicissitudes of military conflict.

21

Moellendorf, Jus ex Bello, p. 130.

22

Orend, Morality of War, p. 195.

11 Brian S. Gallagher

Orend can be seen to unconsciously struggle with this theoretical weakness as he

contradicts himself concerning the USs moral responsibility in reconstructing Iraq. Discussing

the ends of a just war, he remarks that it is only when the victorious regime has fought a just

and lawful war, as defined by international law and just war theory, that we can speak

meaningfully of rights and duties, of both victor and vanquished, at the conclusion of armed

conflict.

23

If post-war rights and duties have meaning only when a war is began justly and

justly concluded, it would seem America has no means of justification in its restorative

occupational role in Iraq. Orend realizes this, and tries to wiggle away from this conclusion in

asserting that the US should not just up and leave because of the Pottery Barn Rule dictate: if

you break it, you buy it. In breaking Iraq, Orend contends, the US brought upon itself separate

responsibilities to help put Iraq back together [my italics].

24

He goes on to say that America,

therefore, has few rights, but many duties, regarding post-war Iraq [my italics]. I assume that

he takes these duties of America to have meaning in the sense above, but how can it be

reconciled with that stance he takes? Either the US has meaningful duties, or it does not. This is

perhaps the central problem with Orends account of jus post bellum: he wants to derive post-war

duties from the just adherence to just war principles and hold the US to that standard, yet he also

cant avoid granting the US post-war duties despite their failure to uphold that standard. Thus his

invocation of separate responsibilitiesseparate, presumably, because they are not derived from

adherence to just war principles. But from where, then, are they derived? If they are derived from

the Pottery Barn Rule, as Orend readily concedes, our task must then be to further characterize

the ethical nature of this principle, and to put forward an account of wherein an international

political ethicthis principle fits. Orend does not do this. Rather, he is content to assume what

23

Ibid., p. 162.

24

Orend, Morality of War, p. 196.

12 Brian S. Gallagher

he must prove: namely, that the goal of regime change, of realizing human rights, of building a

minimally just society,

25

can be read off, and extrapolated from, the jus ad bellum principles

which justify the resort to war in the first place. To his credit, this is very nearly right; for the

mistakethe fallacious stepis a subtle one, which I will now set forth to explain and make

bare.

II.

Like Moellendorf

26

(and like Walzer

27

before him), Orend

28

subscribes, though not

explicitly, to a cosmopolitan account of states rights. In its most basic form, it is the view that

states have rights only in virtue of those human rights possessed by their inhabitants. A states

rights, in other words, are dependent upon, and derived from, those of its populace. This

collective manifestation of rights in the state is contingent upon the state upholding the rights of

its membersforgoing this, the state loses claim to its rights. This is contrasted to a statist

conception of states rights, which is more dated and conservative in character because the state

is said to have rights independently from those of its inhabitants. As Moellendorf observes,

depending on which view of states rights is acceptedstatist or cosmopolitana just cause for,

say, humanitarian intervention, may or may not be permissible. Both he and Orend are advocates

25

Ibid., p. 35 37. Orend outlines three criteria for a minimally just society. The first criterion is the societys

general recognitionby its own people and the international communityas being minimally just. So societies that

fulfill this criterion typically are not pervasively criticized by international officials as being unscrupulous or subject

to heavy skepticism about its capacity to organize a decent communal life for its members. The second criterion is

the societys avoidance of violating the rights of other states, the most easily identifiable case being the commission

of aggression. The third criterion is the societys making every reasonable effort to realize the human rights of its

populace.

26

Darrel Moellendorf, Cosmopolitan Justice (Boulder, Colorado: Westview Press, 2002), p. 159.

27

Walzer, Just and Unjust Wars, pp. 53 54.

28

Orend, Morality of War, pp. 33 35.

13 Brian S. Gallagher

of cosmopolitanism, and Orendelaborating and extending this ideaformulates conditions

that states must meet in a cosmopolitan society if they are to retain their rights: this is the concept

of a minimally just society mentioned above. If a state wishes to retain its rights, then it must

be minimally just, or else it has no moral claim against those who wish to intervene into their

internal affairs, with a moral mandate to protect and secure human rights.

These rights of the state are commonly conceived as, in the least, the right to political

sovereignty, territorial integrity, and resistance against aggression.

29

Therefore, given all that was

said in the above paragraph, when a humanitarian intervention against a state is justified, it is

justified because the state no longer has a claim to any of the three rights just listed. To vividly

bring out Orends mistake in his account of the grounding of post-war rights and duties, Ill lay

out the premises just discussed with reference to the case of Iraq.

I admit, Orend says, that Saddams regime had no right not to be attacked. It seems as

though his regime violated the condition of making every reasonable effort at domestic human

rights satisfaction, and therefore lost the rights of statehood, which includes the right not to be

overthrown.

30

Though he admits this, Orend maintains that the plight of the Iraqi people under

Saddam does not seem comparable to the humanitarian emergencies of Rwanda in the 1990s and

Cambodia in the 1970s; those seemed to require quick and decisive stopping; while for Iraq in

2003, it was not obvious that the humanitarian cause was as pressing, and therefore the question

of whether it would be a wise judgment call to intervene is just thata judgment call. He does

say that humanitarian intervention was the strongest case for the Iraq War, but fighting for that

cause could never justify the war because of the USs originally professed unsubstantiated reason

29

Orend, Morality of War, p. 37.

30

Ibid., p. 97.

14 Brian S. Gallagher

for going: to pre-emptively strike in defense of an anticipated attack by Saddam Hussein.

31

For

Orend, having the right intentionhaving the right reason to initiate the warfrom the start, is

essential for the moral integrity of the war; this includes announcing, in advance, the main reason

for the war, as well as publicly committing to adhere to the mandates of just war theory, meaning

being tempered by the in bello constraints and requirements and of those having to do with

eventually terminating the war justly; being unprepared to meet the responsibilities of waging

war at the time of its initiation counts as an injustice. Winners, like America over Iraq in 2003,

Orend says, should never find themselves in a position where they have won the war but they

do not know what to do next, and so start making up post-war policy on the fly.

32

This is the

result of their scatter-shot

33

approachlisting a host of plausible-sounding reasons for war but

never settling on a main or defining causean approach that conveys the impression of being an

incompetent statesmen and is therefore irresponsible.

34

I will not be taking a stance on whether the war in Iraq was just or not (though I am

inclined to think that, given Saddams unscrupulous and depraved regime, such hostilities were

inevitable). Let us entertain, then, the logic of the following premises. In the case of the Iraq war,

it is by definition the case that Saddam waged an unjust war against the US: his regime was

unworthy of the right not to be overthrown and had no moral right to wage war in defense

because of its failure to be minimally just. Thus, either the US war in Iraq was a case of both

31

Orend, Morality of War, pp. 78 83.

32

Ibid., p. 164.

33

Ibid., p. 49. The approach is scatter-shot because, as the name implies, no particular cause for war is targeted as

the main, animating reason. Orend observes that the Iraq war was, at one time or another, justified by each of these

reasons: 1) Saddam had WMDs, some of which could be deployed within forty-five minutes; 2) Saddam intended to

give some of its WMDs to al-Qaeda, for use against America; 3) Saddam was actually involved with al-Qaeda in the

9/11 attacks; 4) Saddam needed to be overthrown as an act of humanitarian intervention on behalf of the Iraqi

people; 5) Saddam posed a threat to regional security, especially regarding Israel and the Saudi oil-fields; 6) Saddam

kicked out the UN weapons inspectors in 1998 violating the Persian Gulf War treaty, which specified possible

violent consequences for doing so; and 7) Saddam needed to be overthrown to create forcibly the first Arab

democracy, which would serve as a Trojan Horse for better values throughout the Islamic world.

34

Ibid., p. 50.

15 Brian S. Gallagher

sides warring unjustly, or not. If neither side was just, thenaccording to Orenda just peace

settlement would be, as a matter of principle, impossible; or, as he would say, there could only

be injustice after such a war because the injustice of [the USs] cause infects the conclusion of

the war

35

However, as I mentioned earlier in the paper, Orend concedes that moral

considerations independent of justicethose aforementioned separate responsibilitiessupply

a standard of evaluation for judging the social and political relations within a state and those

extending internationally, as better or worse. This fact also implies a standard of accountability

for bringing these outcomes aboutwhich Orend alludes to in submitting that the US is

accountable for rehabilitating Iraq; yet he is silent on how this could be, given that real post-war

duties are supposed to arise from the waging of a just war from the start. I submit, therefore, that

the real question about justice after war (lets say with the case in Iraq) is this: By what

permissible means is the US to achieveregardless of the wars justicethe bettering of the

Iraqi state? In other words, justice after war is just thatthe justice that comes after the war has

concluded, after it has been deemed just or unjust: the question of how to realize justice after war

must be a live and real question regardless of whether the recently concluded war was unjust. For

this precise reason, the question of how to realize justice in the aftermath of war is not the

prerogative of just war theory to answer: it only answers the questions of whether a war was

justly initiated, justly executed, and justly terminated; the justice of war lies in the ethical

practice and regulation of the three activities that constitute it. The practice of restoring and

rehabilitating a war-torn society does not form part of the practice of warfare, and is therefore

not guided by the normative regulatory principles of warfare, which are jus ad bellum, jus in

bello, and jus terminare bellum.

35

Orend, Morality of War, p. 162.

16 Brian S. Gallagher

All this entails a further interesting implication. It is possible for two unjustly warring

states to agree to a cease-fire and subsequently agree to a fully just peace settlement. For Orend,

this is not possible, because in order for there to be a just peace settlement at the termination of

war, there had to have been one state with justice on its side from the start. But this seems

implausible, I think, in view of my proposed revision: if we characterize a just peace settlement

by the fairness of its terms in view of the weight of justice and injustice on each side, then we

can say that, even when a war is unjust on both sides, still, they can come to agree to a fair set of

terms in a cease-fire, at least in principle. I say this because, empirically, such a scenario is not

likely since the unjust wars would probably be denounced as illegal by the international

community, whose members would then therefore have the right to intervene to stop itjustly

and if victorious, then we are brought back to a case where there is justice on one side of the war.

In this sort of event, the terms of the peace settlement would be made or overseen not by the

unjustly warring states, but by an international body or a unilateral representative of such. We

can, however, imagine a case where such just intervention by the international community is not

possible. If a war, waged unjustly on both sides, is terminated, the practice of terminating the

warwithout the oversight and mandate of a just third-partycould still conceivably be just;

what makes it just is having the counting up of injustices on each side fairly factor into the terms

of the settlement. Here I agree with Orend that justice comes in degrees, so that one side could be

more unjust than the other, which would mean more concessions would be made by the side with

a higher degree of injustice. I leave it open to argument whether, say, violations of jus ad bellum

are more weighty than those of jus in bello; how to add these injustices up and factor them into

the peace settlement appropriately is beyond the scope of this thesis. I submit this as an aspect

that requires more conceptual fleshing-out.

17 Brian S. Gallagher

Now we are ready to turn, finally, to the set of principles that make up jus terminare

bellum

36

. Just as there is a requirement of just cause to initiate a war, so must there be one to

terminate it. The most obvious case where a just cause to terminate war is present is when the

war has been won, which essentially means that the rights whose violation justified the wars

initiation have been victoriously vindicated. In other words, once the just cause for the war has

been realized, the justice of war termination requires that the war end. And as mentioned before,

wars do, in the vindication of violated rights, aim for a more secure possession of them. This is

to say that, in justly terminating a war, the war must end in such a way as to create the conditions

for a peace that is more secure than that which preceded the onset of war. A war may also be

justifiably terminated if it is likely to fail, or if its continuance could only promise an outcome

that is disproportionately good in comparison to the bad effects of waging it. And in terminating

war, its assumed that there is an authority that has the power to do so; requiring that the

authority be legitimate has some plausibility, for instance, in cases where it might be positively

unjust to terminate the war; but, most of the time, no one will listen to someone who wishes to

terminate the war that has no authority to do so in the first place. A war also may be justly

terminated if an opportunity for diplomatic resolution arises

37

. There is an important

qualification to this criterion that Moellendorf refers to by way of quoting Walzer: It isnt

always true that such cease-fires serve the purpose of humanity. Unless they create a better

better state of peace, they may simply fix the conditions under which the fighting will be

resumed, at a later time and with a new intensity. Not all diplomatic resolutions, in other words,

36

Remember from earlier in the paper that this is essentially Moellendorfs account of jus ex bello. He, however,

frames his principles in terms of justifying the continuance of war. I frame the same principles negatively in terms

of what would justify, not the wars continuance, but rather its termination. So I take it that, in general, if one is

justified in terminating war, then one is thereby unjustified in continuing it, and vice versa. However, exceptions to

this are possible.

18 Brian S. Gallagher

are adequate to justify war termination. So we must ask, what are the considerations that favor

seeking a negotiated settlement over a non-negotiated one and vice versa? If an unjustly warring

state is sufficiently morally bankrupt and coarse, like Saddam Hussein, it may only be

demeaning and degrading to negotiate with him; it also may simply be unwise, for hes likely not

to abide by the terms of the settlement in any case. So, taken together, the principles of jus

terminare bellum are so far: i) just cause, 2) likelihood of failure, 3) disproportionality, and 4)

opportunity for diplomacy. But another is important to mention, and it is political and military

trust. Justly terminating war depends on both of these levels, as political leaders must be counted

on to abide by the terms of settlement (if there are any) and soldiers must not take advantage of

the enemy letting their guard down when hostilities have ceased. Trust strengthens the entire

system of normative regulation of warfare, and helps to further peace not only immediately after

war but for future wars as well; so on consequentialist grounds, trust is an important criterion for

import. Just reflect on how difficult it would be to terminate war if no one actually believed that

the fighting would stop after a settlement had been made. Its not only powerful in terms of

consequences, however; to lie and to breach a settlement in order to swindle ones enemy is

wrong regardless of the consequences.

The application of these principles can become more complicated, however, in a situation

where the just termination of war itself causes an injustice to arise as a consequence of ending it.

Imagine, for instance, that the US would be justified in terminating its war in Iraq, say, because it

could no longer afford fighting Saddam, who nevertheless was significantly weakened by the US

bombardment. But now with the US planning to leave, and with Saddam weakened, his rivals

and enemies within and around Iraq see an opportunity to try and seize power and thereby a civil,

sectarian, ethnic, and/or regional war ensues. Now, because (well say) in this case the USs war

19 Brian S. Gallagher

was justified by a cause for humanitarian intervention, this means that, in terminating their war

and leaving, they must do their best to mitigate the injustice in failing to realize the just cause of

humanitarian intervention. As Moellendorf says, Because the war satisfies the principle of just

cause, the process of withdrawing troops requires balancing the moral requirement of not

extending an unjust war against the requirement to mitigate the injustice that cannot be

remedied.

38

Hence this means, in more concrete terms, that the military aims must become more

modest in comparison to the formerly stronger aims which were set in order to realize the just

cause in fulllike, for example, seeking merely the protection of the Kurd minority rather than,

more strongly, seeking the ousting of the regime and the sources of hostility that threaten them.

In summation, then, I shall review what has been argued for thus far. There is first the

issue of how to understand the tripartite structure of just war theory as well the purpose of the

theory itself. The waging of war, I have said, consists in three distinct activities, each with their

own set of regulatory principles and precepts. Jus ad bellum for the initiation of war, jus in bello

for the execution of war, and jus terminare bellum for the termination of warthis, Ive argued,

is a conceptually complete account of what is involved in waging a just war. I then went on to

show that jus post bellum, most ardently and sophisticatedly explicated by Orend, is

consequently left without a place in just war theory. This is because it provides a view of what

rights and duties states have to each other after war has been concluded, rights and duties the

discharging of which constitutes an activity quite distinct from waging war, and therefore

requiring a likewise distinct set of ethical criteria separate from those that regulate the practice of

warfare. Ive attempted to show that Orend comes up against this very fact and, as a result of his

account, contradicts himself, or at least stumbles into inconsistency. This was illustrated I think

38

Moellendorf, Jus ex Bello, p. 135.

20 Brian S. Gallagher

rather plainly in how Orend admitted that, despite the US not having justice on its side, it still

retained duties to aid in the rehabilitation of Iraqa position that is clearly ruled out by his own

contention that there can only be duties of justice postwar in the event of a war justly waged; I

therefore disagree with his assertion that each phase of warthe initiation, execution, and

terminationare intimately bound together in such a way that were a war to be initiated unjustly,

the practices of executing and terminating would necessarily be unjust as well. To the contrary

Ive attempted to show that a war can be terminated justly even in a case in which it was unjustly

initiated. If this is all right, then I have dismantled the tripartite version of just war theory

proposed by Orend and thus have reopened the question of how to understand the moral basis for

the rights and responsibilities we think states sometimes possess in the aftermath of war.

21 Brian S. Gallagher

Bibliography

Bass, G. (2004). Jus Post Bellum. Philosophy & Public Affairs, 384-412.

Bellamy, A. J. (2008). The Responsibilities of Victory: Jus Post Bellum and the Just War.

Review of International Studies, 601-625.

Evans, M. (2008). Balancing Peace, Justice, and Sovereignty in Jus Post Bellum: The Case of

'Just Occupation'. Journal of International Studies, 533-554.

Evans, M. (2009). Moral Responsibility and the Conflicting Demands of Jus Post Bellum. Ethics

and International Affairs, 147-164.

Fabre, C. (2008). Cosmopolitanism, Just War Theory, and Legitimate Authority. International

Affairs, 963-976.

Kant, I. (1991). Perpetual Peace. In H. Reiss, Political Writings (pp. 93-130). Cambridge:

Cambridge University Press.

Kellogg, D. E. (2002). Jus Post Bellum: The Importance of War Crimes Trials. Parameters, 87-

99.

McCready, D. (2009). Ending the War Right: Jus Post Bellum and the Just War Tradition.

Journal of Military Ethics, 66-78.

Melandri, M. (2011). The State, Human Rights, and the Ethics of War Termination: What

Should a Just Peace Look Like? The Journal of Global Ethics, 241-249.

Moellendorf, D. (2002). Cosmopolitan Justice. Boulder: Westview Press.

Moellendorf, D. (2008). Jus ex Bello. The Journal of Political Philosophy, 123-136.

Orend, B. (2000). Jus Post Bellum. Journal of Social Philosophy, 117-137.

Orend, B. (2006). The Morality of War. Peterborough: Broadview Press.

Orend, B. (2007). Jus Post Bellum: The Perspective of a Just-War Theorist. Leiden Journal of

International Law, 571-591.

Recchia, S. (2009). Just and Unjust Postwar Reconstruction: How Much External Influence Can

Be Justified? Ethics and International Affairs, 165-187.

Walzer, M. (1977). Just and Unjust Wars. New York: Basic Books.

Welsh, A. G. (2009). The Imperative to Rebuild: Assessing the Normative Case for Postconflict

Reconstruction. Ethics and International Affairs, 121-146.

22 Brian S. Gallagher

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- Human Rights and Humanitarian Intervention: Legitimizing the Use of Force since the 1970sD'EverandHuman Rights and Humanitarian Intervention: Legitimizing the Use of Force since the 1970sPas encore d'évaluation

- Jus Post Bellum WilliamsDocument12 pagesJus Post Bellum WilliamsSebastián Aliosha Soto CaviedesPas encore d'évaluation

- Just War TheoryDocument11 pagesJust War TheoryJoshuandy JusufPas encore d'évaluation

- Just War Theory - FinalDocument15 pagesJust War Theory - FinalPouǝllǝ ɐlʎssɐPas encore d'évaluation

- Carl Schmitt's Five Arguments Against The Idea of Just War - Gabriella SlompDocument14 pagesCarl Schmitt's Five Arguments Against The Idea of Just War - Gabriella SlompAnonymous eDvzmvPas encore d'évaluation

- (International Library of Critical Essays in The History of Philosophy) Haakonssen, K. (Ed.) - Grotius, Pufendorf and Modern Natural Law-Dartmouth (1999) PDFDocument607 pages(International Library of Critical Essays in The History of Philosophy) Haakonssen, K. (Ed.) - Grotius, Pufendorf and Modern Natural Law-Dartmouth (1999) PDFThiagoPas encore d'évaluation

- Miller-2008-Journal of Political PhilosophyDocument20 pagesMiller-2008-Journal of Political PhilosophyfaignacioPas encore d'évaluation

- Cecile Fabre - Whose Body Is It Anyway - Justice and The Integrity of The Person (2006)Document247 pagesCecile Fabre - Whose Body Is It Anyway - Justice and The Integrity of The Person (2006)SergioPas encore d'évaluation

- (Routledge Research in International Law) Milena Sterio - The Right To Self-Determination Under International Law - Selfistans, - Secession, and The Rule of The Great Powers-Routledge (2012)Document225 pages(Routledge Research in International Law) Milena Sterio - The Right To Self-Determination Under International Law - Selfistans, - Secession, and The Rule of The Great Powers-Routledge (2012)Nona TatiashviliPas encore d'évaluation

- Machiavelli's Paradox - Trapping or Teaching The PrinceDocument13 pagesMachiavelli's Paradox - Trapping or Teaching The PrinceDavid LeibovicPas encore d'évaluation

- Machiavellis True Views The Discourses VDocument7 pagesMachiavellis True Views The Discourses VThomas ClarkePas encore d'évaluation

- Dismantling The Cyprus ConspiracyDocument85 pagesDismantling The Cyprus ConspiracyCHRISTOSOFATHENSPas encore d'évaluation

- The Prince and The Modern PrinceDocument12 pagesThe Prince and The Modern Princevsprlnd25Pas encore d'évaluation

- Michael Walzer Oblogation To DisobeyDocument14 pagesMichael Walzer Oblogation To DisobeyInternshipexternePas encore d'évaluation

- Just War DebateDocument7 pagesJust War Debateapi-437469743Pas encore d'évaluation

- Postcolonialism and Global JusticeDocument15 pagesPostcolonialism and Global JusticeDerek Williams100% (1)

- McCornick P John - Machiavellian Democracy - Controlling Elites With Ferocious PopulismDocument17 pagesMcCornick P John - Machiavellian Democracy - Controlling Elites With Ferocious PopulismDianaEnayadPas encore d'évaluation

- Key Points From EssayDocument6 pagesKey Points From EssayMaya AslamPas encore d'évaluation

- An End To The Clash of Fukuyama and Huntington's ThoughtsDocument3 pagesAn End To The Clash of Fukuyama and Huntington's ThoughtsAndhyta Firselly Utami100% (1)

- Andreasson 2014 - Conservatism in Political Ideologies 4th EdDocument29 pagesAndreasson 2014 - Conservatism in Political Ideologies 4th EdSydney DeYoungPas encore d'évaluation

- Machiavelli and The Context in Which He Wrote The PrinceDocument32 pagesMachiavelli and The Context in Which He Wrote The PrinceJamir Gayo100% (1)

- St. Augustine and Neo-PlatonismDocument3 pagesSt. Augustine and Neo-PlatonismCherrey Mae BartolataPas encore d'évaluation

- Conceptualizing NationalismDocument23 pagesConceptualizing NationalismShameela Yoosuf Ali100% (1)

- Schall Metaphysics Theology and PTDocument25 pagesSchall Metaphysics Theology and PTtinman2009Pas encore d'évaluation

- ABIZADEH Democratic Theory and Border Coercio. No Right To Unilaterally Control Your Own BordersDocument29 pagesABIZADEH Democratic Theory and Border Coercio. No Right To Unilaterally Control Your Own BorderslectordigitalisPas encore d'évaluation

- Tuck - 1987 - The 'Modern' Theory of Natural LawDocument11 pagesTuck - 1987 - The 'Modern' Theory of Natural LawTomás Motta TassinariPas encore d'évaluation

- 1950 Marshall Citzenship and Social Class OCR PDFDocument47 pages1950 Marshall Citzenship and Social Class OCR PDFFer VasPas encore d'évaluation

- Me Too Movement: Time To Break The SilenceDocument11 pagesMe Too Movement: Time To Break The SilenceSudheer VishwakarmaPas encore d'évaluation

- Kleinhaus - Leo Strauss On ThucydidesDocument28 pagesKleinhaus - Leo Strauss On ThucydidesDimitris PanomitrosPas encore d'évaluation

- Scheuerman - Between The Norm and The Exception - The Frankfurt School and The Rule of Law PDFDocument328 pagesScheuerman - Between The Norm and The Exception - The Frankfurt School and The Rule of Law PDFnicolasfrailePas encore d'évaluation

- Russell Kirk The Conservative MindDocument73 pagesRussell Kirk The Conservative MindDenisa Stanciu100% (1)

- 4352 002 The-Roots-Of-Restraint WEBDocument78 pages4352 002 The-Roots-Of-Restraint WEBputranto100% (1)

- Gabriel-2017-Journal of Applied PhilosophyDocument17 pagesGabriel-2017-Journal of Applied PhilosophymikimunPas encore d'évaluation

- Luca Baccelli - Political Imagination, Conflict and Democracy. Machiavelli's Republican Realism PDFDocument22 pagesLuca Baccelli - Political Imagination, Conflict and Democracy. Machiavelli's Republican Realism PDFarierrefbPas encore d'évaluation

- NamDocument46 pagesNamKumar DatePas encore d'évaluation

- CubaDocument28 pagesCubaANAHI83Pas encore d'évaluation

- (Michael J. Butler) Selling A 'Just' War Framing, (BookFi) PDFDocument299 pages(Michael J. Butler) Selling A 'Just' War Framing, (BookFi) PDFEdson Neves Jr.Pas encore d'évaluation

- Unanswered Threats: Political Constraints on the Balance of PowerD'EverandUnanswered Threats: Political Constraints on the Balance of PowerÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1)

- Sociological DebatesDocument7 pagesSociological DebatesStatus VideosPas encore d'évaluation

- Political Communication in the Arabian Gulf Countries: The Relationship Between the Governments and the PressD'EverandPolitical Communication in the Arabian Gulf Countries: The Relationship Between the Governments and the PressPas encore d'évaluation

- Kibbutz TzubaDocument14 pagesKibbutz TzubaDana EndelmanisPas encore d'évaluation

- Jervis Realism Neoliberalism Cooperation DebateDocument22 pagesJervis Realism Neoliberalism Cooperation Debatemcqueen2007Pas encore d'évaluation

- End of The Post Colonial StateDocument28 pagesEnd of The Post Colonial StateOpie UmsgoodPas encore d'évaluation

- Machiavelli Popular Resistance and The CDocument35 pagesMachiavelli Popular Resistance and The CFabio PrimoPas encore d'évaluation

- R2P and The US Intervention in Libya PDFDocument300 pagesR2P and The US Intervention in Libya PDFHidayatmuhtarPas encore d'évaluation

- Nature of The StateDocument5 pagesNature of The Stateapi-223744460Pas encore d'évaluation

- Global Society: Publication Details, Including Instructions For Authors and Subscription InformationDocument24 pagesGlobal Society: Publication Details, Including Instructions For Authors and Subscription InformationmichaeljohngloverPas encore d'évaluation

- Schmitt Teology PDFDocument21 pagesSchmitt Teology PDFEmanuele Giustini100% (1)

- European Security IdentitiesDocument30 pagesEuropean Security Identitiesribdsc23100% (1)

- Leo Strauss - Machiavelli & Classical Literature (1970)Document21 pagesLeo Strauss - Machiavelli & Classical Literature (1970)Giordano Bruno100% (2)

- John Chalcraft - Popular Politics in The Making of The Modern Middle East (2016, Cambridge University Press) PDFDocument612 pagesJohn Chalcraft - Popular Politics in The Making of The Modern Middle East (2016, Cambridge University Press) PDFKepa Martinez GarciaPas encore d'évaluation

- Michael Mann - The Dark Side of Democracy - Explaining Ethnic Cleansing (2004)Document590 pagesMichael Mann - The Dark Side of Democracy - Explaining Ethnic Cleansing (2004)Lorena Cardona100% (1)

- Fujimori y Chavez PopulismoDocument358 pagesFujimori y Chavez PopulismoRafael Mac-QuhaePas encore d'évaluation

- Intro To PeacebuildingDocument13 pagesIntro To PeacebuildingesshorPas encore d'évaluation

- Harold Berman,: Law and RevolutionDocument32 pagesHarold Berman,: Law and RevolutionTay Na MoPas encore d'évaluation

- Philosophy Faculty Reading List and Course Outline 2019-2020 Part IB Paper 07: Political Philosophy SyllabusDocument17 pagesPhilosophy Faculty Reading List and Course Outline 2019-2020 Part IB Paper 07: Political Philosophy SyllabusAleksandarPas encore d'évaluation

- Democracy and Its CriticsDocument7 pagesDemocracy and Its CriticskurtdunquePas encore d'évaluation

- Summary of The Geneva ConventionsDocument3 pagesSummary of The Geneva ConventionsTechRavPas encore d'évaluation

- Topic 6 - Peace and DevelopmentDocument11 pagesTopic 6 - Peace and Developmentvin mellowPas encore d'évaluation

- Heneral Luna Critique PaperDocument6 pagesHeneral Luna Critique PaperJulliane Manuzon100% (2)

- Fy13 Srip2Document61 pagesFy13 Srip2NeilRupertPas encore d'évaluation

- Battles of Ligny and Waterloo DescriptioDocument45 pagesBattles of Ligny and Waterloo DescriptioRichard BarrettPas encore d'évaluation

- TTG Sultan HasanuddinDocument5 pagesTTG Sultan HasanuddinNdy AdlaiPas encore d'évaluation

- Mary R. Bachvarova From Hittite To HomerDocument690 pagesMary R. Bachvarova From Hittite To HomerPanos Triantafyllidhs100% (6)

- Sniper EliteDocument2 pagesSniper EliterexPas encore d'évaluation

- UntitledDocument4 pagesUntitledaufchePas encore d'évaluation

- 21st Bomber Command Tactical Mission Report 223, 231, OcrDocument110 pages21st Bomber Command Tactical Mission Report 223, 231, OcrJapanAirRaids100% (1)

- Thunder Roads New York Magazine - March 2010Document40 pagesThunder Roads New York Magazine - March 2010Thunder Roads New York100% (1)

- Production Information For Military Versions of The Model 1911 Handgun MFG From 1912 To 1945Document10 pagesProduction Information For Military Versions of The Model 1911 Handgun MFG From 1912 To 1945blowmeasshole1911Pas encore d'évaluation

- RAPP, Rez. Peace and War in Byzantium PDFDocument4 pagesRAPP, Rez. Peace and War in Byzantium PDFDejan MitreaPas encore d'évaluation

- Whitney Museum: Jenny Holzer: PROTECT PROTECT BrochureDocument5 pagesWhitney Museum: Jenny Holzer: PROTECT PROTECT BrochurewhitneymuseumPas encore d'évaluation

- The EstellaDocument242 pagesThe EstellaHoàng MinhPas encore d'évaluation

- Moral Sense TestDocument4 pagesMoral Sense TestDeepam TandonPas encore d'évaluation

- Raquiza Vs BradfordDocument6 pagesRaquiza Vs BradfordTahani Awar GurarPas encore d'évaluation

- Space Wolves 6th Ed V1Document7 pagesSpace Wolves 6th Ed V1fuffa02Pas encore d'évaluation

- AP U.S. Unit 7 Exam + AnswersDocument8 pagesAP U.S. Unit 7 Exam + Answersdanwillametterealty60% (5)

- Purnell Reference Books - 20th Century v4 PDFDocument152 pagesPurnell Reference Books - 20th Century v4 PDFevripidis tziokasPas encore d'évaluation

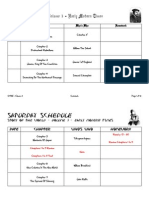

- STOW - Vol. 3 - ScheduleDocument12 pagesSTOW - Vol. 3 - ScheduleDavid A. Malin Jr.100% (2)

- Little Red ManDocument2 pagesLittle Red ManTommy GoodwinPas encore d'évaluation

- Ammunition TablesDocument7 pagesAmmunition Tablesenrico100% (1)

- Crisis and Absolutism in Europe Post InstructionalDocument13 pagesCrisis and Absolutism in Europe Post Instructionalapi-239756775Pas encore d'évaluation

- Basic Impetus 1 CheatsheetDocument1 pageBasic Impetus 1 CheatsheetchalimacPas encore d'évaluation

- 2023-2024 Academic Calendar - Ges FinalDocument7 pages2023-2024 Academic Calendar - Ges FinalNusenu Kwaku50% (2)

- Modern Guided Aircraft BombsDocument14 pagesModern Guided Aircraft Bombsمحمد علىPas encore d'évaluation

- Historical Dictionary of The Gilded Age (2009)Document317 pagesHistorical Dictionary of The Gilded Age (2009)yasser rhimiPas encore d'évaluation

- San Ramon Prison and Penal FarmDocument12 pagesSan Ramon Prison and Penal FarmRica Mae MarceloPas encore d'évaluation

- Soft Power Fast Power: Joseph Nye John ChipmanDocument1 pageSoft Power Fast Power: Joseph Nye John Chipmanprasenajita2618Pas encore d'évaluation