Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

9 FCFD 5109 Be 4086178

Transféré par

Creddy Pradeep BTitre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

9 FCFD 5109 Be 4086178

Transféré par

Creddy Pradeep BDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Causes of Sub-prime crisis

and

Public Intervention

ATM TARIQUZZAMAN

Executive Director

Securities and Exchange Commission

Dhaka, Bangladesh

atm_zaman@hotmail.com

DR. QUAMRUL ALAM

Department of Management

Monash University

Australia.

Quamrul.alam@buseco.monash.edu.au

MOHAMMAD ABU YUSUF

Department of Management

Monash University

Australia

e-mail: mohammad.yusuf@buseco.monash.edu.au; ma_yusuf@hotmail.com

Corresponding Author: ATM Tariquzzaman

e-mail: atm_zaman@hotmail.com

1

Causes of Sub-prime crisis

and

Public Intervention

Abstract: This paper examines two issues: (i) the underlying causes of subprime lending

and resultant crisis that severely damaged the US and world financial markets; and (ii) the

rationality of state intervention in such crises. A comprehensive analysis of the subprime

crisis suggests that excessive deregulation of the financial system, lax regulation,

excessively accommodative monetary policy, bad lending and housing bubble have been

responsible for the subprime crisis and global financial meltdown. Withdrawal of the state

from financial markets due to over confidence in the market and irrational behaviour by the

borrowers, lenders and investors driven by greed aggravated the subprime crisis.

Keywords: Subprime, Financial Crisis, Organizational leadership, Layoff, Strategic decision

making

2

1. INTRODUCTION

The financial market has been dramatically changed in the last few months as the subprime

mortgages meltdown in the USA dried up credit markets and funding liquidity (White 2008) and

created a ripple effect in the global economy (Harmon 2008). The impact of the global financial

crisis, first felt in J uly 2007 when Bear Stearns, the fifth largest investment bank in the US ,

announced that two of its mortgage investment funds, worth about $US 1.5 billion, had literally

no value left in them (Nason 2007). Then Lehman Brothers opted for the biggest bankruptcy in

US history (The New Age, Dhaka, 8 December, 2008).

The US government also came up with a $US700 billion rescue fund to buy a stake in a broad range

of financial companies (The Australian, 5 November, 2008). Central banks of different countries

across the world are slashing interest rates to battle the deepening global crisis. In a globalized world

where nations are increasingly interdependent, the downturn in the worlds largest economy has had

global ramifications. The US downturn is sweeping across the world- Every nation, every government

and every economy is affected (Rudd, 2008). The subprime crisis and resultant economic recession

are having significant impact on organizations management practices. Unlike normal circumstances,

executives in charge of managing enterprises are now focusing more on minimising losses instead of

maximising profits. Strategically, organizational leaderships are increasing their focus on reducing

(through layoff, cutting back shifts/working time) or relocating their workforce (Ernst and Young

2009) and resorting pay cuts with a view to reducing costs and avoid bankruptcy. For instance,

Holden are cutting back shifts in order to slow production (King 2009). Pacific Brands decided to

move its production offshore (axing more than 1800 jobs in Australia) in an effort to reduce costs

(Schneiders, Sharp & Murphy 2009). Organizations are increasingly getting it difficult to access trade

credit from banks/lenders. Critical thinking and strategic decision making by business leadership

became essential to weather this difficult period. The ongoing financial crisis rooted in subprime

lending has put enormous pressure on CEO/Boards of enterprise to manage/adjust their workforce

wisely and meet cash requirements so that businesses do not suffer in the long run from want of

skilled and experienced staffing. This paper contributes to the existing literature by demonstrating

3

how highly decentralised and weak regulatory architecture created conditions for the near collapse of

the global financial system that forced governments of major economies to come up with rescue

package . The crisis is so acute that the G-20 leaders (in Pittsburgh meeting) had to reach a strong

consensus'' on firmer oversight of the global financial system and measures to curb excessive

executive pay (Davies, 2009). This paper provides a brief description of the precursors of subprime

lending in section 2. Section 3 discusses the factors responsible for the subprime crisis. Section 4

examines why government intervention becomes necessary in the event of financial meltdown and

Section 5 offers some suggestions for improvements in the financial regulatory and monitoring regime

to minimise the recurrence of such crises. Section 6 concludes the paper.

2. PRECURSORS OF SUBPRIME LENDING AND ITS GROWTH

Subprime mortgages are residential loans extended to individuals who do not qualify for

prime credit, i.e., individuals who have a higher likelihood of default (J onker 2008:9) and

are generally not eligible for credit from traditional sources. It represents mortgage lending

that allows the unsuitable borrowers to get credit those who for a variety of reasons would

otherwise be denied it (Chomsisengphet & Pennington-Cross 2006). Subprime borrowers

are high risk borrowers as they are often unable to offer a down payment, they have a record

of being unable to pay debts and they do not have income source. In the case of those who

have income, their credit liability is disproportional to that income.

Low global interest rates arising from high levels of global liquidity

i

(such as huge surpluses

accumulated in China, J apan and the OPEC nations which match the savings deficits in the

USA

ii

) contributed to rapid credit expansion. This credit expansion resulted in high asset

prices which preceded the crisis. The US government policy of interest rate cuts, tax

incentives on mortgage loans and encouragement for spending and lending initiated during

1980s created the policy platform for subprime lending. In the US, it was Greenspans

extraordinarily low interest-rate policy at the Federal Reserve that provided the extra fuel for

subprime lending and heated up the housing sector of the US economy (Foo 2008).

Subprime loans went to borrowers who had never qualified for a loan. Relaxation of

mortgage credit standards since 1977 and the enactment of the Community Reinvestment Act

4

(CRA), encouraging banks to extend more credit to the communities in which they operated,

created an environment for a subprime credit bonanza. The First-time Homebuyer

Affordability Act 1999 and the American Homeownership and Economic Opportunity Act

200l, eased financing home buyers down payments and house loan provisions to home

buyers (Fisher, 2001): Borrowers are being approved for loans that they would have been

turned down for [sic] just a year or two ago (Crum 2000).

Banks became popular with lower income and minority borrowers as lenders promised loans

with less paperwork, quick approval and no down payments. Banks and financial

institutions seduced the new borrowers(who were signing up to subprime deals) by easy- to-

get loans and attractive short-term interest rates (commonly known as teasers); but they

actually had to lock in to higher rates, reset often double the original rate after two years a

rate they could hardly afford (Brummer 2008).

Lack of due diligence

iii

resulted in different types of subprime loans. Some (home) loans

required little or no proof of a borrowers ability to meet repayments known as low

documentation (low doc

iv

) or no documentation (no doc) loans while other loans needed

no proof of income or credit history. Other types of mortgages included jumbos-

particularly large loans which were disproportionate to borrowers incomes or house values.

Mortgages were also sold by brokers and intermediaries without assessing the buyers

affordable capacity.

3: CAUSES OF THE SUBPRIME CRISIS

High liquidity of capital and its global movement, US government policy coupled with

imprudent behavior on the part of both lenders and borrowers and poor corporate

governance can be linked to the massive subprime loans that ultimately turned into the

subprime crisis. Self interest (greed) by the subprime lenders and Government Sponsored

Entities (GSEs) (i.e. Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac) are also liable for escalating the crisis.

Greed had triumphed over the traditional banking virtue of prudence (Brummer 2008:53).

These government-backed mortgage companies were aware of the risks they were

shouldering; yet they invested heavily in the subprime and alternative mortgage market,

5

ignoring the warning about the risks and probable losses of their investments in mortgage

backed securities. Warnings were raised by Fannies risk officer that many of the loans

would be susceptible to losses if home prices fell. Concerns were also raised about the

authenticity of the rating agencies risk assessment. The practice of these two GSEs of

buying so- called no-income, no-asset (NINA) mortgages allowing borrowers to get loans

without showing or verifying their income or assets was also opposed by the risk officer

(Hagerty 2008). Still the GSEs continued with their reckless lending practices. They lent

more than $US30 million between 2003 and 2007 but their irresponsible decisions have

resulted in billions of tax payers money bailing out financial organizations (Hughes 2008).

Easy availability of subprime credit not only resulted in the subprime crisis and, ultimately

in economic recession, but also developed a speculative consumption psyche among the

consumers for commodities which seems unaffordable to them at their present income

stream. The consumption psyche, coupled with easy access to credit cards increased the

possibility of more loan defaults by the consumers, thus aggravating the credit crisis further.

The causes of the subprime crisis are many and complex. The odious partnership of banks,

real estate companies, home building and GSEs which was formed under the home ownership

policy of the US govt to support affordable housing was the root cause of the subprime crisis

(Whalen 2008). The homeownership policies pursued under the Clinton administration

(namely National Home Ownership Strategy which had its mandate in the Community

Reinvestment Act (CRA), 1977) with a view to extending home loans to many who could not

afford them were instrumental in massive subprime lending. The partnership has been called

odious because it was almost unprecedented for regulators to forge close partnership with

those whom they have been charged to regulate. The CRA does not prescribe specific criteria

for evaluating the performance of financial institutions, but stipulates that the evaluation

process should accommodate the situation and context of each individual institution

(Demyanyk and Hemert 2008).

The specialised agencies who disbursed most subprime loans were not subject to the safety

and soundness regulations(as they are not deposit taking institutions) that apply to federal

6

or state banks, leaving the door open for fraud and abuse. These entities were less closely

monitored under the Home Ownership and Equity Protection Act, 1994 (HOEPA) and the

CRA. The outcome was a marked increase in abusive and predatory lending

v

(Schumer and

Maloney 2007).

Subprime lending created favourable conditions (through housing loan on easy terms and

conditions) for increased demand for housing loans which in turn enhanced home ownership

during the bubble years. The housing bubble was a major cause, if not the cause of the

subprime crisis. The perception that house prices go only in one direction i.e., go up year after

year

vi

created an atmosphere among lenders and financial institutions towards relaxing their

credit terms and risking default. Expansion in credit following easy credit terms has been an

important factor in asset price boom and bust cycles in the US and in other countries such as ,

J apan, Norway, Sweden, Finland

vii

and Mexico in the recent past. When the central bank

increased interest rates (tightened monetary policy) 17 times from 1% to 5.25% and imposed

reserve requirements in 2004-06 to moderate credit expansion with the motive of fighting

inflation, the bubble burst. Asset prices collapsed. Falls in asset prices imposed significant

strains on the banking sector (Allen and Gale 2007; Katalina and Bianco 2008). Financial

institutions holding real asset and stocks with falling prices (or with loans to the owners of

these assets) suffered greatly because payments are often missed by borrowers and banks

foreclose on the loans. The For Sale signs were thus seen everywhere (Brummer 2008).

However, the lenders could not recover the full amount of their credit by liquidating the assets

as the reduced asset prices become inadequate to cover their loans (as their loan amount is

fixed). This resulted in widespread defaults and retrenchments in the financial system. This

in turn exacerbated the problem of falling asset prices (negative asset price bubble.

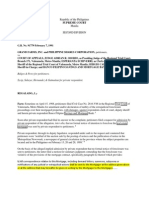

This scenario suggests that expansionary credit policy and the occurrence of significant rises

in asset prices, and subsequent fall in asset prices (property boom and bust) are symbiotically

related. Expansionary credit policy led to boom in asset (housing) prices. This asset, especially

in the housing boom, caused a kind of madness in lenders attitude to approve any amount of

loans irrespective of the value of mortgage assets. In this regard, it is worth noting in one

7

instance, a couple were given loans worth $15 m on a house bought (with no down payment)

for $1.16 m. This couple then drew $333,000 to spend on consumer goods and lived in a nice

home for three years before walking away (The Economist, 29 Nov,2008:86). This madness

generally attracts everyone other than the few who can resist the temptation of buying a house

in a rising market with an easy loan. The symbiotic relationship between credit policy, asset

prices and financial crisis is shown in Figure 2(in appendix)

Figure -1 to be inserted here

With the collapse of the housing bubble came high default rates on subprime, Adjustable Rate

and Alt-A(near prime) mortgages. Significant falls in asset prices (housing bust), along with

high debt have led to weak balance sheets, resulting in widespread defaults and insolvency

(Davis and Karim 2008). The bursting of the housing bubble has become a direct cause of the

breach of trust among market players. Market players are unwilling to lend to each other,

because they are not sure they will be repaid. Many investments that were rated AAA turned

out to be junk when the housing bubble burst (Krugman 2008). Nobel laureate Krugman

believes the causes of the crisis are ideological: I believe that the problem was ideological:

policy makers, committed to the view that the market is always right, simply ignored the

warning signs about a potential subprime crisis (Krugman 2007).

Lower capital adequacy of banks deepens the financial crisis because it reduces banks

robustness to shocks. Although banks risk adjusted capital adequacy ratio appears sound,

securitisation created hidden difficulties for banks (Davis and Karim, 2008). The Subprime

crisis was aggravated as the banking system was not better regulated with an adequate

capital-asset ratio. The Federal Reserve and other agencies waited until it was too late before

trying to tame the excesses in the financial sector. Before 2007, Federal Reserve and

treasury officials praised subprime lenders for helping millions of families buy homes for

the first time. They were more occupied with the dream of providing people with home

ownership than in safeguarding the interests of depositors and the broader society (Andrews,

2007). It looks like a popular election campaign approach.

4 MARKET FAILURES AND GOVERNMENT INTERVENTION

8

The subprime crisis and the resultant financial meltdown forced the US and other developed

economies to come forward with massive financial support to rescue troubled banks and

financial institutions. Governments around the world had to devise fiscal stimulus packages

and take monetary measures to cut interest rates. The US government bailout package of

$700 billion became its biggest intervention in the financial system since the Great

Depression (Hughes & Guy 2008). The bailout packages and other government interventions

are due to market failure in three main tasks: to manage risk, mobilise savings, and allocate

capital (Stiglitz, 2008). The proponents of unregulated capitalistic market economy rely

overly on market based solutions and they consider that the market will automatically correct

imperfections. In this global crisis, it is evident that sole reliance on the market may be

harmful for society when the market itself is overly optimistic. The recent collapse of the

financial markets has already raised questions about the sustainability of the unregulated

capitalistic system. We call it unregulated because some non-bank subprime lenders were not

subject to any regulations. For instance, a lot of the subprime loans were lent by independent

mortgage brokers who were not regulated or insured by the Federal Deposit Insurance

Corporation (FDIC) (Harmon 2008). Some may say (and some have already expressed their

view) that capitalism has lost its relevance. We argue that capitalism is not at risk. It is the

excessive reliance on the market, too much deregulation and excesses by financial institutions

that are responsible for the financial collapses.

Reasons for government intervention

The recent turmoil in the global financial system, the behaviour of corporate executives, the

role of rating agencies and distorted market information that led to consumers going crazy

clearly suggest that the market led model is not always a perfect one. The crisis illustrates

how financial intermediaries, banks, and brokers deceived people and harmed their interest in

terms of loss of home ownership. Millions of homeowners in the US have defaulted on their

mortgage payments and are in danger of losing their property (Baaquie 2009).

Compelling subprime borrowers to default on unbearable loan payments under complex

subprime loan covenants (such as 2/28, 3/27 adjustable rate mortgages ), leading to millions

9

of homeowners losing their homes , the collapse of banks and other financial institutions

inflicting harms on investors and drying up inter-bank credit

viii

and loans to small and

medium sized firms created a situation where its ill effects affected lives over and above the

loss of homes. Against this backdrop of deregulated markets going to the wall, governments

had to step in to provide security to multiple stakeholders (who rely on the financial system

for loans, dividends, jobs and other financial services). For example, the UK government

were being forced to bail out the previously high ranking bank to the tune of 30 billion

pounds. The US government rescued Citi-group by guaranteeing $US306 billion of troubled

mortgage assets (held by Citigroup) and injecting another $US20 billion in capital. In

September, 2008 the US government committed $US700 billion towards rescuing the leading

financial institutions and injecting liquidity into the US economy. Similar steps were taken by

the UK and other European Union countries costing a huge amount of public money (Baaquie

2009). The examples of state intervention mentioned so far demonstrate the reality that in a

welfare state, governments have an obligation to protect investors, taxpayers and the

shareholders from the moral hazards of financial intermediaries. The pursuit of self- interest

(greed) led these institutions to engage in socially destructive activities that ignored even the

interests of their own shareholders.

Reposing sole confidence in the market and treating the market as the only saviour seems

somehow a mistaken concept. Neve, Luetchford & Pratt commented (2008:3) under neo-

liberalism the Market is treated as universal, a trans-historical and trans-cultural entity; it is

naturalised and reified, rather than thought of as a set of social relations; it is treated as a

given rather than the result of a historical process with complex social actors. This is not

always the case. Market forces manipulated the weak regulatory regime and as a result failed

to correct market imperfections. The subprime crisis and the resultant global economic

recession is largely the result of the excesses of financial market capitalism (Wood 2008).

There are examples where market could not always emerge as protectors of the public good

by rectifying its imperfections. In particular unfettered markets are not self-correcting and

there always remains an important role for government to play in the economy (Stiglitz

10

2008). It is to be noted that government intervention is not without its demerits. It was

government policies (lower interest rate, tax deductibility, CRA etc) which prompted initially

large scale subprime lending. Once the subprime crisis occurred, government intervention

and rescue packages become inevitable options to bolster market confidence and keep

financial institutions afloat. The US Treasury has already spent almost all the first US$350

billion tranche of the Troubled Assets Relief Program on top of its US$ 700 billion bailout

package (Australian Financial Review, 24 November 2008). The UK government has

nationalised Northern Rock which went bankrupt in September, 2007(Baaquie,2009).The

US$19 billion bailout package for three automotive companies is a clear sign that state

intervention is the last resort when all market mechanisms fail.

Socialists may celebrate the recent government interventions in the financial system

(government guarantees to bank liabilities and central banks providing cash to financial

institutions) as the victory of socialistic ideology and the end of capitalism. We however,

disagree with that notion. It is not capitalism that has collapsed; rather it is parts of the

financial system

ix

that are in serious difficulty. Edwards (2008) argues, Capitalism is not in

danger, but there is no doubt that some aspects of the way the global economy works needs

serious thought. The issues that need serious thought include among others, the transparency

of risk, the role of rating agencies, capital adequacy, asset valuation and imprudent behaviour

by lending agencies. Capitalism does not mean dismantling of regulations. Rather proper

regulation and reforms are necessary to allow capitalism work in citizens best interests.

Interventions to bail out Citigroup, Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, AIG, Northern Rock etc.,

using public money, may be beneficial in the short term but it is most likely there will have

long-term impacts (such as moral hazard) for rewarding bad behaviour. Corporate boards of

the institutions and their allies who were instrumental in creating the crisis should not be

allowed to get off scot free. Reckless lending and borrowing, which is to be contained would

rather be encouraged by public guarantees. To avoid such global catastrophe in the longer

term, revamping the regulatory architecture for the global financial system with agreed

11

variations is an important requirement. Public guarantees to reenergise the financial sector

worldwide show that the state is the bearer of capital.

5. HOW COULD THE RECURRENCE OF FUTURE CRISES BE MINIMISED?

It is well accepted that no model or regulatory regime is perfect. No amount of fine tuning of

regulations and risk measurement can be a sufficient and perfect response to the increasing

complexity in global financial markets (Hildebrand 2008). There are human limitations.

Complete elimination of the recurrence of such events and crises is unrealistic. However,

streamlined and tight regulations with a more ethical corporate governance regime could

minimise such recurrence. Different suggestions are already on the table for a global

response. Quiggin (2008:62) proposed a system of narrow banking where regulated and

guaranteed banks are confined to a specific set of low risk activities with well established

accounting rules. The following are some of the areas where improvements could be made

to reduce the possibility of recurrence of such crises:

Basel II needs reform

The new capital adequacy rules of Basel II depend largely on the use of credit agency ratings.

The rating agencies themselves lack credibility. Given the lack of credibility of the rating

agencies in the structured credit market turmoil, allowing these agencies to perform a quasi-

regulatory role in relation to capital adequacy by Basel II seems inappropriate (Melbourne

Centre for Financial Studies, 2007). Basel II rules set by the Basel Committee on Banking

Supervision have a degree of national discretion. Therefore, national governments should set

tight capital requirements for banks that are in conformity with their exposure to operational

risks (including risks attached with dealing in structured financial products) and help them

secure sufficient capital to cushion against losses. In other words, banks' reserve requirements

should be tailored to the riskiness of their customers.

Global financial watchdog

Over the last few decades the world capitalist order has faced a series of problems which

have struck particularly the global financial system (Beams 2008). The world financial

market is now more interdependent and interrelated than ever before. The globalization of the

12

world financial system not only brought benefits in terms increased trade and easy and

cheaper access to capital, also allowed US bankers to export the results such as the subprime

crisis, the collapse of the share market, increased unemployment, and social and

psychological stress, all costing many countries billions of dollars for their greed and

mistakes (Brummer 2008). It is apparent that a global financial institution to monitor and

control the financial system with a view to protecting consumers and investors interests is

absent. Such international institutions are in place to monitor and regulate other cross border

economic and trade activities, for example the WTO for trade facilitation and dispute

settlement, the IMF for currency and exchange rate stabilization, the World Bank for

financing development activities, etc. No such institution exists to monitor and guide

international financial markets. So a global financial watchdog is a necessity.

Credit check

It is also necessary on the part of the government to bring about some changes in the

legislation to ensure that lenders must verify a borrower's ability to pay and to promote

fairness, financial stability and social justice. Moreover, margin requirements (safety margin

and buffer) could be introduced in lending where borrowers obtain loans on the basis of

inadequate collateral.

Asymmetry in incentive structure (where profits are shared by employees as bonuses but

losses are borne by banks, shareholders etc) motivates bank employees to take a short- term

view and excessive risk. This asymmetry should be reduced and banks need to adjust their

incentive structures to force bank employees exercise due diligence in lending and

investment.

6. CONCLUSION

Subprime lending is not the source of all evils. It is simply the manifestation of a disease

that has been growing in structured financial products for the last couple of years. The

collective actions of uninformed residential mortgage borrowers

x

, financial intermediaries,

rating agencies and poorly informed irrational exuberant investors in the absence of proper

regulations have led to the growth of the subprime market. Growth in subprime lending

13

ultimately turned into global financial meltdown causing severe adverse consequences for

home owners, investors, lenders, employees and tax payers. The top executives of

enterprises are under acid test how to face the crisis and survive if not grow in this difficult

time. It seems that, a totally decentralised, ineffective and fragmented regulatory regime has

weakened the fundamental basis of the market- based financial system. The negation of the

states regulatory role without creating a global watchdog has created a non-transparent and

unaccountable financial system that was pivotal in causing the crisis. Against the backdrop

of the collapse of previously high-flying financial institutions, which were considered too

big to be allowed to fail, states had to step in and rescue them pumping in billions of dollars

from the public exchequer. The result of the subprime crisis seems to be the classic

combination of capitalised profits and socialised losses. Capitalism cannot be blamed for the

crisis because it was not at fault; rather the absence of proper monitoring and regulations

can be largely blamed for this. Too much reliance on market force helped to cause the crisis.

The implications for the policy makers are that proper regulatory governance is essential to

ensure sustainability of the global economic and business activities. The perception that the

state has no significant role in market economy has been proved a myth. The state

intervention can be an important policy measure to restrain corporate excess, introduce

ethical and responsive corporate behaviour with a view to protecting stakeholders interest.

The crisis has also impacted the psychology of risk of the financial institutions. The

financial crisis and collapse (or near collapse) of many financial institutions triggered an

increase in the risk aversion of banking and financial institutions resulting in pulling back

them from lending. It has also dented the confidence of bank depositors who are concerned

about banks solvency. This increase in risk aversion will definitely have far reaching

ramifications on the access to finance, industrial output, trade and business transactions,

employment, discretionary spending and GDP growth of the countries across the world.

14

15

Appendix

Figure 1: Credit policy, asset prices (boom and bust) and financial crisis

relationship

Credit

Expansion

Asset

price

bubble

Madness in

lenders

attitude-

(more

credit)

Inflation

Loan default

(Banking/financ

ial crisis)

Asset price

bust/collap

se

Tightened

monetary

policy/incr

ease

interest

(credit

contractio

n)

(Source: the Authors)

16

i

The high level of global liquidity stems from countries (such as China) current account

surpluses and foreign exchange reserves, maintaining artificially low exchange rates and a

positive savings investment balance.

ii

J ohn Edwards, Capitalism, The Deal, P-32

iii

Not only lenders but also Investors bought AAA-rated instruments with little or no further

diligence or consideration of risk

iv

Because low-doc loans involve higher risk, the lenders require a higher deposit from the

homebuyers, usually between 20 per cent and 40 per cent of the property's value

v

Mortgage lending on the basis of asset value, without regard to borrower ability to pay, is

widely recognized as predatory and harmful to borrowers.

vi

There were no data on the long term performance of home prices neither for the US nor for

any other country.

vii

In Finland, housing price rose by a total 68 percent in 1987-88 due to massive credit

expansion (bank loan to GDP ratio increased from 55 percent in 1984 to 90 percent in 1990)

17

18

viii

In February 2007 HSBC acknowledged a loss of $10.8 billion in its US real estate

portfolio. In J uly 2007, two of Bear Stearns hedge funds defaulted on about $10 billion of

financial obligations, causing losses of $1.5 billion of investors money. By August 2007,

there was large scale panic in the financial markets resulting in flight from the US real estate

market. Banks were no longer willing to provide liquidity to other banks since it was not

clear which financial institution was holding what quantity of toxic subprime mortgages

(Baaquie,2009). In addition to that, fear also acts as an obstacle which made banks reluctant

to lend (Andrews,2009)

ix

These are new developments in the financial system such as the growing use by banks of

the originate and lending model, the reliance on off-balance sheet vehicles, the development

of new structured products, and the reliance on ratings agencies in making them pretty to

investors (White,2008)

x

Bicksler (2008) referring to survey information observes that residential mortgage

borrowers were borrowing rate and transaction costs uninformed.

19

REFERENCES

ACCA. (2008) Climbing out of the credit crunch: An ACCA Policy paper, The Association

of Chartered Certified Accountants, London, September.

Allen, F. & Gale, D.(2007) Understanding Financial Crises, Oxford University Press, New

York,

Andrews, E.(2009, J anuary 12). US has no guidebook to countering fear, The Australian

Financial Review, Melbourne p. 11

Ashcraft, A.B. & Schuermann, T.(2008) Understanding the Securitization of Subprime

Mortgage Credit, Staff Report No.318:1-76

Andrews, E.L.(2007) December 18. Fed Shrugged as Subprime Crisis Spread, The New

York Times,

Bianco, K.M.(2008) The Subprime Lending Crisis: Causes and Effects of the Mortgage

Meltdown, CCH Mortgage Compliance Guide and Bank Digest: 1-21

Baaquie, B.E (2009 3 J anuary). US subprime loans and the 2008 financial meltdown, The

New Age, Editorial, Dhaka

BBC.(2007) The US sub-prime crisis in graphics, 21 November BBC News, available at

http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/business/7073131.stm?src=rss viewed on 22/04/2008.

Bicksler, J .L.(2008) The subprime mortgage debacle and its linkages to corporate

governance, International Journal of Disclosure and Governance, 5(4):295-300

Brummer, A (2008 )The Crunch: the Scandal of Northern Rock and the Escalating Credit

Crisis. Random House Business Books: London.

Chomsisengphet , S & Pennington-Cross, A (2006) The Evolution of the Subprime

Mortgage Market, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Review, J an/Feb:31-56

Crum G. R (2000) Get Fast Loan Approval, Christian Science Monitor, J uly 3 . 16 sec. 2

Demyanyk, Y.& Hemert, O.V (2008) December 5. Understanding the Subprime Mortgage Crisis,

SSRN working paper, p. 1-39

Davis, E.P. and Karim, D (2008) Could Early Warning Systems Have Helped to Predict the Subprime

Crisis? National Institute Economic Review, 206:35-47

Davis, P. & Barrell, R (2008) The Evolution of the Financial Crisis of 2007-8, National Institute

Economic Review, .206:5-15

Davies, A (2009) G20 'consensus' on global financial reforms, The Age, September 26

20

Edwards, J .(2008) Capitalism; It is not the end of the financial World, The Australian

Business Magazine, November, 1(2):32-33

Ernst and Young (2009) Seizing Opportunities A Once in a lifetime chance.

http://www.ey.com/Publication/vwLUAssets/Seizing_Opportunities:_A_once_in_a_lifetime_chance/

$File/11992_Exceptional_Enterprises_Sgl_F.pdf accessed on 27 May 2009

Foo, C. T (2008) Conceptual lessons on financial strategy following the US subprime crisis, the

Journal of Risk Finance, 9(3)::292-302

Harmon, J (2008) Subprime Crisis More Aptly called a Securitization Crisis, National Mortgage

News, New York. 33(11): 6-7

Hagerty, J .R (2008) Email trail exposes risky business of Mae and Mac, the Australian. December

11:21

Hildebrand, P.M (2008)The subprime crisis: A central bankers perspective, Journal of Financial

Stability, 4(4):313-320

Hughes, A (2008) Fannie and Freddie ignored warnings. The Australian Financial Review, December

11:13

Hughes, A & Guy, R (2008) US forced to save Citigroup, The Australian.25 November

J onker, W (2008) The subprime saga: anatomy of an accident, Collective insight, Finweek, autumn,

Media 24

Katalina, M. & Bianco, J .D.2008. The Subprime Lending Crisis: Causes and Effects of the Mortgage

Meltdown, CCH Mortgage Compliance Guide and Bank Digest. pp. 1-21 accessed

http://www.business.cch.com/bankingfinance/focus/news/Subprime_WP_rev.pdf.

Keys, B.J . , Mukherjee, T., Seru, A. And Vig, V (2008) Did Securitization Lead to Lax Screening?

Evidence From Subprime Loans 2001-2006.

http://www.emilioontiveros.com/EO/Did%20securitization%20lead%20to%20lax%20screening-

evidence%20from%20subprime%20loans%202001-2006.pdf accessed 9 J anuary 2009.

King, P (2009, 3 April) Holden trims shifts to avoid layoffs, The Australia, April 03

Klan, A (2008) Low-document loans are dead, says J ohn Symond .The Australian. September 20

Krugman, P (2007, 3 December) Innovating our way to financial crisis, New York Times,

Lander, D (2008) Regulating Consumer Lending. In Xiao, J .J .(Eds.), Handbook of Consumer Finance

Research.387-410. Newyork: SpringerLink.

Lay, B (2008) J oseph Stiglitz: The chuckling economist, Eurokea Street

Leonard P (2007) Testimony of Paul Leonard, California office director, before the California senate

banking committee, Center for responsible lending, March 26, available at

21

http://www.responsiblelending.org/pdfs/FINAL-Leonard-3-26-Testimony.pdf viewed on

05/05/2008.

Macartney, J (2008, December 2) Red alert as capitalist failings threaten communism, The

Australian, Melbourne

Melbourne Centre for Financial Studies (2007), Lessons from Recent Financial Turmoil

(http://www.melbournecentre.com.au/ANZSFRC/ 30 November, 2008

Neve, G.D. Leutchford, P. & Pratt, J (2008) Hidden Hands in the Market: Ethnographies of Fair

Trade, Ethical Consumption, and Corporate Social Responsibility, Research in Economic

Anthropology, 28:1-30

Moodys Corporation (2007) Investor Day Presentation, August 2007.

Quiggin, J (2008 December 04) Banks should be banks again, The Australian Financial

Review, Melbourne

Reilly, D (2008, 2 December) Banks should be held responsible, the Australian, Melbourne,

Rosner, J (2001)Housing In the New Millennium: A Home Without Equity Is J ust a Rental With Debt,

SSRN Working Paper

Rudd, K. (2008, 26 November) Full text of the ministerial statement by Kevin Rudd, The Australian

Schneiders, B, Sharp, A. & Murphy, K (2009) Work heads offshore as Pacific Brands Axes J obs. The

Age, Melbourne, 26 February 2009

Schumer, C.E. & Maloney, C.B (2007) The Sub Prime Lending Crisis: The Economic Impact on

Wealth, Property Values and Tax Revenues and How We Got Here, Report and Recommendations by

the Majority Staff of the Joint Economic Committee, US October

Schwarcz, S.L (2008) Markets, Systemic Risk, and the Subprime Mortgage Crisis, Southern

Methodist Law Review:61(2)

Selten, S.L (2008) Regulation of the Financial Market is Important Spigel Online International,

(http://www.spiegel.de/international/world/0,1518,590035,00.html accessed on 06 J anuary,2009)

Shiller, R.J (2008) The Subprime Solution: How Today's Global Financial Crisis Happened, and What

to Do about It, Princeton University Press:1-192

Solomon, D (2008) November 5. Treasury to broaden focus of financial rescue package,

The Australian, Melbourne

Stiglitz J .E.(2006) Making Globalization Work, Allen Lane, Penguin Books, Australia.

Stiglitz, J .E (2008) Nobel Economists Offer First Aid for Global Economy, accessed via

http://www.spiegel.de/international/business/0,1518,590038,00.html on 28 Nov,2008

Stiglitz, J . E (2008. 9 December) Heeding Keynes real message, the Age, Melbourne

22

The Australian (2008, November25.) Citigroup rescue sparks Wall St surge, Melbourne.

The Economist (2008, November 29) Paper Money: 85-86

The New Age (2008) December,8. Dhaka

Whalen, R.C (2008) The Subprime Crisis- Cause, Effect and Consequences, Networks Financial

Institute, March

White, W.R (2008) Past financial crises, the current financial turmoil, and the need for a new

macroeconomic stability framework, Journal of Financial Stability, 4(4) :307-312

Wood, A (2008, December 19) Profit motive, not philanthropy, can save the world, The Australian,

Melbourne.10

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (121)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (588)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (266)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (400)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5794)

- The Shadow Banking SystemDocument1 pageThe Shadow Banking SystemcitypaperPas encore d'évaluation

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2259)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1090)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (895)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (74)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- Credit Repair Retainer AgreementDocument3 pagesCredit Repair Retainer AgreementKNOWLEDGE SOURCE100% (2)

- Grands Farms v. CA (Digest)Document3 pagesGrands Farms v. CA (Digest)Kikoy IlaganPas encore d'évaluation

- Citi - Auto ABS PrimerDocument44 pagesCiti - Auto ABS Primerjmlauner100% (1)

- Infosys Offer LetterDocument2 pagesInfosys Offer LetterAbhinav Darbari11% (9)

- Wipro Offer Letter PDFDocument14 pagesWipro Offer Letter PDFChandni Agrawal75% (8)

- BP Amoco CaseDocument37 pagesBP Amoco CaseIlayaraja DhatchinamoorthyPas encore d'évaluation

- Biñan Steel Corporation Vs CADocument7 pagesBiñan Steel Corporation Vs CAirish7erialcPas encore d'évaluation

- Day 1 Checklist 2018Document1 pageDay 1 Checklist 2018Creddy Pradeep BPas encore d'évaluation

- Payment Acknowledgement Payment Acknowledgement: General GeneralDocument1 pagePayment Acknowledgement Payment Acknowledgement: General GeneralCreddy Pradeep BPas encore d'évaluation

- Payment Acknowledgement Payment Acknowledgement: General GeneralDocument1 pagePayment Acknowledgement Payment Acknowledgement: General GeneralCreddy Pradeep BPas encore d'évaluation

- Letter of Offer Clean Version PDFDocument52 pagesLetter of Offer Clean Version PDFCreddy Pradeep BPas encore d'évaluation

- Marketing Capsule FR Sbi PoDocument16 pagesMarketing Capsule FR Sbi PoPuneet KhatriPas encore d'évaluation

- Computer AwarenesDocument51 pagesComputer AwarenesCreddy Pradeep BPas encore d'évaluation

- 1012091291872997quantitative AptitudeDocument6 pages1012091291872997quantitative AptitudeCreddy Pradeep BPas encore d'évaluation

- WebsitwebsitesesDocument1 pageWebsitwebsitesesCreddy Pradeep BPas encore d'évaluation

- PC Keyboard Shortcuts PDFDocument1 pagePC Keyboard Shortcuts PDFSelvaraj VillyPas encore d'évaluation

- Seminar Report On: HadoopDocument42 pagesSeminar Report On: HadoopujjjjjawalaPas encore d'évaluation

- My Dinh Lam Felony InformationDocument6 pagesMy Dinh Lam Felony InformationCamdenCanaryPas encore d'évaluation

- Buying Vs Renting: Net Gain by Buying A HomeDocument2 pagesBuying Vs Renting: Net Gain by Buying A HomeAnonymous 2TgTjATtPas encore d'évaluation

- 11 Spouses Buot vs. CADocument6 pages11 Spouses Buot vs. CARachel LeachonPas encore d'évaluation

- Tax Anticipation Scrip As A Form of Local Currency in The USA During The 1930s - Loren GatchDocument34 pagesTax Anticipation Scrip As A Form of Local Currency in The USA During The 1930s - Loren GatchLocal MoneyPas encore d'évaluation

- AGENT, Sub Agnet and SustitutedDocument34 pagesAGENT, Sub Agnet and SustitutedTathagat SharmaPas encore d'évaluation

- Eugenio v. Sta. Monica RiversideDocument3 pagesEugenio v. Sta. Monica RiversideAliyah RojoPas encore d'évaluation

- Insurance Company OperationsDocument5 pagesInsurance Company Operationssvprasad1986100% (1)

- Case Study On Loan Portfolio of Southeast Bank LimitedDocument31 pagesCase Study On Loan Portfolio of Southeast Bank LimitedMahi MaheshPas encore d'évaluation

- P2 103 Special Revenue Recognition Installment Sales Construction Contracts Franchise 1Document12 pagesP2 103 Special Revenue Recognition Installment Sales Construction Contracts Franchise 1Kate Alvarez100% (2)

- Hawala Used To Launder 20 Million in England - Money JihadDocument3 pagesHawala Used To Launder 20 Million in England - Money JihadSaslina KamaruddinPas encore d'évaluation

- 72 - Roman vs. Asia Banking Corporation, 46 Phil. 705, June 26, 1922Document3 pages72 - Roman vs. Asia Banking Corporation, 46 Phil. 705, June 26, 1922Christine ValidoPas encore d'évaluation

- Kshitij Case SolutionDocument18 pagesKshitij Case SolutionKshitij Vijayvergia100% (1)

- PTU DDE BBA Finance International Finance Exam - Paper2Document3 pagesPTU DDE BBA Finance International Finance Exam - Paper2Gaurav SehgalPas encore d'évaluation

- Financial Inclusion and Information TechnologyDocument8 pagesFinancial Inclusion and Information TechnologydhawanmayurPas encore d'évaluation

- Company CasesDocument14 pagesCompany CasesLynette Tang100% (1)

- 2nd Assignment PDFDocument36 pages2nd Assignment PDFbobPas encore d'évaluation

- Chap 005Document8 pagesChap 005Anass BPas encore d'évaluation

- Year Wise Compliance Report of Audit Paras/Audit Comments 2010-2011 Sr. No para No. Office With Subject Status/PositionDocument5 pagesYear Wise Compliance Report of Audit Paras/Audit Comments 2010-2011 Sr. No para No. Office With Subject Status/PositionNaeem AkhtarPas encore d'évaluation

- 1 Compare & Contrast Objective Risk and Subjective Risk?: Insurance CompanyDocument6 pages1 Compare & Contrast Objective Risk and Subjective Risk?: Insurance Companytayachew mollaPas encore d'évaluation

- Lyons Vs RosenstockDocument3 pagesLyons Vs Rosenstockj531823Pas encore d'évaluation

- Credit Bureau Understanding Your Credit ReportDocument1 pageCredit Bureau Understanding Your Credit ReportsurfnewsPas encore d'évaluation

- A Project Study On Banking at HDFC Bank LTDDocument99 pagesA Project Study On Banking at HDFC Bank LTDManjeet SinghPas encore d'évaluation

- 1st Case de Leon Vs OngDocument1 page1st Case de Leon Vs OngChristian RiveraPas encore d'évaluation

- Personal Property Loan AgreementDocument7 pagesPersonal Property Loan AgreementSergio ArtinanoPas encore d'évaluation