Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

The TOWS Matrix - A Tool For Situational Analysis

Transféré par

mr.avdheshsharmaDescription originale:

Titre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

The TOWS Matrix - A Tool For Situational Analysis

Transféré par

mr.avdheshsharmaDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

1

The TOWS Matrix ---

A Tool for Situational Analysis

Heinz Weihrich*, Professor of Management, University of San Francisco

This article has two main purposes One is to review general considerations in strategic planning and the second to introduce the TOWS

Matrix for matching the environmental threats and opportunities with the company's weaknesses and especially its strengths. These factors

per se are not new; what is new is systematically identifying relationships between these factors and basing strategies on them. There is little

doubt that strategic planning will gain greater prominence in the future. Any organization—whether military, product oriented,

service-oriented or even governmental—to remain effective, must use a rational approach toward anticipating, responding to and even

altering the future environment.

Situational Analysis: A New Dimension in Strategic Planning

Today most business enterprises engage in strategic planning, although the degrees of sophistication and formality

vary considerably Conceptually strategic planning is deceptively simple: analyze the current and expected future

situation, determine the direction of the firm and develop means for achieving the mission. In reality, this is an

extremely complex process, which demands a systematic approach for identifying and analyzing factors external to

the organization and matching them with the firm's capabilities.

The purpose of this article is twofold: first, the concept of strategy and a model showing the strategic process are

introduced. This part not only provides an overview of strategic planning, but also alerts the reader to the various

alternatives available for formulating a strategy. The second purpose of the article is to propose a conceptual

framework for identifying and analyzing the threats (T) and opportunities (O) in the external environment and

assessing the organization's weaknesses (W) and strengths (S) For convenience, the matrix that will be introduced is

called TOWS, or situational analysis. Although the sets of variables in the matrix are not new, matching them in a

systematic fashion is. Many writers on strategic planning suggest that a firm uses its strengths to take advantage of

opportunities, but they ignore other important relationships, such as the challenge of overcoming weaknesses in the

enterprise to exploit opportunities. After all, a weakness is the absence of strength and corporate development to

overcome an existing weakness may become a distinct strategy for the company. Although efforts are now being

made to gain greater insights into the way corporate strengths and weaknesses are defined, much remains to be

done.1

The TOWS matrix, discussed later in detail, also serves as a conceptual framework for future research about the

combination of external factors and those internal to the enterprise, and the strategies based on these variables.

*

The author is Professor of Management, School of Business and Management, University of San Francisco, San Francisco, CA 94117,

U.S.A. He has had many years of business and consulting experience in the United States and Europe, working with such companies as

Volkswagen, Hughes Aircraft Company, etc.

Long Range Planning © Heinz Weihrich

2

Equally important, the matrix 'forces' practicing managers to analyze the situation of their company and to develop

strategies, tactics, and actions for the effective and efficient attainment of its organizational objectives and its

mission.

Strategic Planning

The term 'strategy' (which is derived from the Greek word 'strategos', meaning 'general') has been used in different

ways. Authors differ in at least one major aspect, Some, such as Kenneth Andrews,2 Alfred D. Chandler3 George A.

Sterner/John B. Miner,4 and Richard Vancil,5 focus on both the end points (purpose, mission, goals, objectives) and

the means of achieving them (policies and plans). But other writers such as Igor H. Ansoff 6 and Charles W.

Hofer/Dan Schendel7 emphasize the means to the ends in the strategic process rather than the ends per se. The great

variety of meanings of the word 'strategies' is illustrated in the glossary of one book:

[Strategies are] general programs of action and deployment of emphasis and resources to attain comprehensive objectives; the

program of objectives of an organization and their changes, resources used to attain these objectives, and policies governing the

acquisition, use, and disposition of these resources; tile determination of the basic long-term objectives of an enterprise and the

adoption of courses of action and allocation of resources necessary to achieve these goals.8

In this article, primarily because of space limitations, the narrow meaning will be used, that is, the ends will not be

emphasized so that sufficient attention can be given to the analysis of the current situation. It is assumed that the

purpose of the firm has already been established, yet is subject to change after an evaluation of the situation.

Present

Inputs External External

People Environmen Treats and

Capital Opportunities

Medium Range

Managerial Evaluation and Planning

Skills Strategic

Technical Choice

Skills

Goals of Enterprise Forecast Alternative

Profile of Future Strategies Short Range

Claimants

Environmen Planning

Internal Implementation

Resource Weaknesses

Audit and Strengths

Consistency

Testing

Contingency

Planning

Figure 1. Strategic planning process

Long Range Planning © Heinz Weihrich

3

Although specific steps in the formulation of the strategy may vary, the process can be built, at least conceptually,

around the following framework:

(1) Recognition of the various organizational inputs, especially the goal inputs of the claimants to the enterprise.

(2) Preparation of the enterprise profile.

(3) Identification of the present external environment.

(4) Preparation of a forecast with predictions of the future environment.

(5) Preparation of a resource audit with emphasis on the company’s internal weaknesses and strengths.

(6) Development of alternative strategies, tactics and other actions.

(7) Evaluation and choice of strategies.

(8) Consistency testing.

(9) Preparation of contingency plans.

These steps—shown in Figure 1—then, serve as the framework for the discussion that follows.

Inputs for Strategic Planning

Strategic planning, to be effective, must carefully consider the inputs into the system. These inputs, de-emphasized

in this discussion, are enclosed by broken lines, as shown in Figure 1. They include people, capital, managerial and

technical knowledge and skills. In addition, various groups of people make demands on the enterprise.

Unfortunately, many of the goals of these claimants are incongruent with each other and it is the manager’s task to

integrate these divergent needs and goals.

Employees, for example, want higher pay, more benefits and job security. Consumers demand safe and reliable

products at a reasonable price. Suppliers want assurance that their products are purchased. Stockholders want not

only a high return on their investment but also security of their money. Federal, state and local governments

depend on taxes paid by the enterprise; they also expect the enterprise to comply with their laws. Similarly, the

community demands that enterprises be 'good citizens', providing jobs and emit a minimum of pollutants. Other

claimants to the enterprise may include financial institutions and labor unions; even competitors have a legitimate

claim for fair play. It is clear that many of these claims are incongruent with each other, and it is management's job

to integrate the legitimate objectives of the claimants.

The Enterprise Profile

The way an enterprise has operated in the past is usually a starting point to determine where it will go and

where it should go. In other words, top executives wrestle with such fundamental questions as:

‘What is our business?’

‘Who are our customers?’

‘What do our customers want?’

‘What should our business be?’

These and similar questions should provide answers about the basic nature of the company, its products and

services, geographic domain, its competitive position and its top management orientation and values. These

topics demand elaboration.

Long Range Planning © Heinz Weihrich

4

Geographic Orientation. A company must also answer questions such as:

‘Where are our customers?’

‘Where are those who should be our customers, but are not at present?’

Companies need to develop a profile of their geographic market. While some firms may restrict themselves to the

eastern part of the United States, others view the whole country as their region of operations. Many large

companies, of course, conduct their business on different continents.

Competitive Situation. Business firms usually do not have an exclusive market; instead, they compete with

other firms. But current market share is not necessarily a sufficient indicator of a firm's long-range potential.

One must also consider other factors and competitive items such as price, quality, cost, services, product

innovation, distribution systems, facilities and locations.

The assessment of the competitive situation involves several steps. First, key success factors must be

identified. Then the relative importance of these key success factors needs to be estimated. Next, the firm's

competitive position in respect to these key success factors must be evaluated and ranked. Thus, only a careful

analysis of the current competitive position provides an indication of the company's future growth and profits.

The competitive analysis, especially for large firms, is done for individual business units, product lines or even

specific products. Moreover, the competitive analysis focus is not only on the present situation, but also looks

into the more distant future. 9 This analysis becomes intricate for firms that compete in the national and

international markets.

Top Management Orientation. An enterprise profile is shaped by people, especially executives. They set the

organizational climate, they influence the atmosphere in the organization and they determine the direction of the

company. For example, management may not pursue opportunities in the liquor business because it conflicts with

top management's values that are against the production and consumption of alcohol. Another example of the

influence of values may be management's commitment to socially responsible actions, believing that these activities

will benefit the enterprise in the long run.

The External Environment: Threats and Opportunities

In the analysis of the external environment, many diverse factors need to be considered. Today, the threats certainly

would include the problems of inflation, energy, technological change and government actions. The diverse

factors—which can be either threats or opportunities—can be grouped into the following categories: economic,

social and political factors, products and technology, demographic factors, markets and competition, plus others.

Economic Factors. The general state of the economy certainly affects strategy formulation. For example, the

expansion phase of the business cycle in the 1960s created an abundance of business opportunities while the

recession in the first half of the 1970s required many industries to change their strategy, and drastically reduce

their business activities. The strategist, of course, takes other economic factors besides the business cycle into

account, such as the level of employment, the availability of credit and the level of prices. Also, individual

companies are affected differently by economic factors. What is a threat to one firm is an opportunity for

another.

Long Range Planning © Heinz Weihrich

5

Social and Political Factors. Social developments also influence the business strategy. For instance,

consumerism and consumer protection movements require the firm's attention to product safety and truth in

packaging. Similarly, managers are confronted by a host of federal, state and local laws and regulations. The

public's demand for clean air, clean water and a clean environment is often considered a threat to business. At

the same time, these factors can become opportunities, as shown by the car emission test requirements in many

states which presented opportunities for the companies to develop, produce or operate such test equipment.

Products and Technology. Products need to be adjusted to technological changes. For example, the astonishing

success of the Volkswagen Beetle in the 1960s diminished in the 1970s. New customer demands for optional

equipment, safety requirements and competition, along with new technology, gave rise to a new generation of

VWs. It must be remembered that in almost all situations success is only temporary and product innovation is

needed to ensure a competitive advantage for the firm. Of course, innovation is also costly and risky and the

failure rate of new products is high; yet, a policy of no innovation at all may cause the demise of a company.

Demographic Factors. Demographic changes significantly affect business. In the United States there are geographic

shifts such as the movement of many people to the 'sun belt'. White-collar jobs tend to increase proportionally to

blue-collar occupations. Income levels are expected to change, although the direction is less clear and may vary for

different sectors of the labor market. The age composition will also change with elderly people making up an

increasing proportion of the population. The strategist must take these and other factors into account because they

influence the preferences for the kinds of products and services demanded by consumers.

Markets and Competition. In the United States, coping with competition in the marketplace is a corporate way

of life. The following questions and the answers to them are crucial for formulating a strategy:

'Who are our competitors?'

'How does our company compare with the competition’

'What are the strengths and weaknesses of our competitors?'

'What are their strategies?'

'How do we best compete?'

Other Factors. There are, of course, many other factors that might be particularly important to a specific firm.

The availability of raw materials, suppliers and the transportation system, are a few examples. The ever-

changing environment demands continuous scanning for opportunities and threats. A company that discovers

customer needs and provides the products and services demanded, certainly has a better chance for success

than an enterprise that ignores such changes.

Information Gathering and Forecast of the Future. To collect data on the various factors is, to say the least, a

tedious task. The study by Jerry Wall of 1211 executives, all readers of the Harvard Business Review, gives

some insights on how companies collect information about their competitors. The sources used most

frequently include: company sales persons, published sources, and personal and professional contacts with

competitors and customers. Other less frequently used sources include: formal market research, brokers,

wholesalers and other middlemen, analyses of processes and products of competitors, and suppliers. The least

utilized sources include: employees of competitors, advertising agencies and consultants.10

Since there are many factors that need to be analyzed, the executives must be selective and concentrate on

those factors that are critical for the success of the enterprise. Furthermore, it is not enough for the strategist to

Long Range Planning © Heinz Weihrich

6

assess only the present environment. Planning for the future, and strategic planning in particular, is very much

concerned with the more distant future. Thus, managers must anticipate the future and forecast changes in the

environment that will crucially affect the enterprise.

The Internal Environment: Weaknesses and Strengths. The demands of the external environment on the

organization must be matched with the resources of the firm. Internal strengths and weaknesses vary greatly

for different enterprises; they may, however, conveniently be categorized into (1) management and

organization, (2) operations, (3) finance and (4) other factors important for a particular organization.

Management and Organization. This category includes not only managerial talent but also the labor force as a

whole. It also encompasses labor relations; personnel policies; the appraisal, selection, training and

development of employees; and the reward system. The planning and control system as well as the

organization structure and climate are equally important for the success of the organization.

Operations. Operations must be carefully analyzed in terms of research and development capabilities, and the

adequacy and productivity of the manufacturing facilities available to meet the expected growth and other

objectives of the firm. Similarly, marketing must be assessed in terms of product distribution channels, brand

name protection, competitive pricing, appropriate customer identification, service, and company image.

Finance. A careful evaluation of the company's strengths and weaknesses also must be made in the areas of

capital structure, financing, profitability, the tax situation, financial planning and the accounting system. Many

financial ratios are available for making analyses. But financial management not only requires focusing on the

past and the present situation; it also demands short- and long-term financial planning congruent with the

firm's objectives and strategy.

Other Factors. The focus here is on the obvious factors on which the strengths and weaknesses of the

organization must be evaluated. Other factors however such as patents inventions and the firms image may be

peculiar to an enterprise or may be prominent during a particular time period.

Strategic Alternatives

The foregoing analysis of environmental opportunities and threats and the company’s strengths and

weaknesses, encourages the creative process of developing alternatives. As any experienced manager knows,

in almost all situations alternative courses of action are available.

One strategy is to specialize or concentrate. Thus, a company may utilize its energy and strengths to pursue a

single purpose or it may restrict its efforts to only a few aims. For example, American Motors for many years

used its limited resources primarily for the production of small cars, rather than competing directly with

General Motors, Ford or Chrysler who had a complete product line ranging from relatively small models to

large, luxurious cars.

Other alternative strategies are backward and forward integration. In backward integration a company may

acquire suppliers to ensure a steady flow of materials. In forward integration the attempt is to secure outlets

for products or services and to reach toward the ultimate user of the product.

Another strategy focuses on diversification by moving into new and profitable markets. This may result in

greater growth than would be possible without diversification.

Long Range Planning © Heinz Weihrich

7

Still another strategy would be to focus on innovation -- new products and new services. Thus, a company,

vulnerable to obsolescence, may look for new ideas whose time has arrived. Polaroid, a company known for

innovation developed through tremendous research and development efforts and the successful SX70 instant

picture camera, a truly innovative product. But, as exemplified by the same company, investing in innovation

is also risky. Polaroid may have persisted too long and invested too much in promoting Polavision, the instant

movie system.

A company may adopt a ‘no change’ strategy and decide to do nothing. Instead of innovation or expansion, a

firm may continue to follow the tried and proven path, utilizing existing products and services and letting

others make possible mistakes in innovation.

A company may also select an international strategy, repeating the approach which was successful in its home

country and extending its operations from there to different parts of the world. Companies with global

strategies include Unilever, Colgate-Palmolive, Singer, Nestle and IBM, to mention a few.

Still another strategic alternative is for an enterprise to decide on liquidation, which may require terminating

an unprofitable product line or service. If the company is a one-product firm, this may mean dissolving the

company—an especially difficult strategic decision.

In some cases the extreme decision of liquidation may not be necessary. Instead, a retrenchment strategy may

be more appropriate. To be sure this is often only a temporary measure and may involve reducing operating

expenses or restricting the scope of the operation. Still, such a strategy may be a viable alternative to

liquidation.

Finally, there is the alternative of engaging in joint ventures, which may take different forms. For example,

corporations may join with foreign firms to overcome political and cultural barriers. Another example of a

joint venture is the Alaskan Pipeline which was a project even too big for one of the financially strong oil

companies. Still another kind of joint venture occurs when two or more firms pool their resources and establish

a new company, which then is jointly owned.

The strategies discussed above provide an overview of possible approaches. Within these categories, of course,

many variations are possible. In reality, enterprises often pursue a combination of these strategies. What has

become clear is that evaluating and choosing a strategy, the next topic of discussion, is not a simple task.

Evaluation and Choice of Strategies

The strategic manager has to evaluate a multiplicity of possible strategies. Clearly, such a manager has to take

into consideration both external realities and internal capabilities. Unfortunately, environments are not static,

but are dynamic and subject to constant change. Thus, the strategist has to make predictions of changes about

the future.

In making strategic choices, opportunities must be evaluated in the light of risks. There may indeed be profit

opportunities for a new product, but the company may not be able to afford the risks involved in the new

venture. At other times, however, a firm cannot afford not taking a calculated risk.

Long Range Planning © Heinz Weihrich

8

Timing is another critical element in the strategic decision. Although early action may at times be desirable

(e.g. to be the first in the market), a firm may not be able to take the risk associated with it. On the other hand,

a company may have to enter a new field because its survival depends upon it.

Companies do not operate in a vacuum, of course. A new strategic action is usually met with a reaction from

one or more competitors, this, in turn, requires counteractions. Clearly, strategic choices are made in a

dynamic environment and to cope with the many uncertainties demands executives with tolerance for

ambiguity.

Consistency Testing

During all stages of strategy formulation, the steps have to be examined for consistency with the enterprise

profile, the present and projected environment, and the resources of the firm. In addition, the goals of the

claimants to the organization have to be considered since the choice of strategy is not only based on a rational

analysis of the facts, but also on personal values and personal goals, especially those of the chief executive

officer, an important claimant to the enterprise, as pointed out above.

Alternative strategies are then tested for congruency with other medium- and short-range plans which, in turn,

may require adjustments of the master strategy. Similarly, the feasibility of implementing the plans also needs

to be examined. For example, the organization structure as well as the availability and suitability of human

resources should be considered before strategic choices are made. As shown in the model in Figure 1,

consistency testing is necessary at the various steps in the strategic planning process.

Contingency Plans

Contingency plans will have to be prepared. Since the future cannot be predicted with great accuracy, plans

need to be made with different premises. To be sure, not all possible contingencies can be taken into account,

but those crucial to the survival and success of a firm—such as a cutoff or reduction of oil from foreign

sources—should provide premises for alternative plans.

An Operational Model for Analysis of the Situation

As pointed out above, it has been common in the past to suggest that companies identify their strengths and

weaknesses, and the opportunities and threats in the external environment. But what is often overlooked is that

combining these factors may require distinct strategic choices. To systematize these choices, the TOWS

Matrix is proposed in which 'T' stands for threats, 'O' for opportunities, 'W' for weaknesses and 'S' for

strengths. Before describing this matrix, however, one should be aware of other 'tools' that have been used

effectively in strategy formulation.

Today, strategy designers have been aided by a number of matrixes showing the relationships of critical

variables. For example, the Boston Consulting Group developed the Business Portfolio Matrix, which

essentially shows the linkages between the business growth rate and the relative competitive position of the

enterprise (identified by the market share). However, this approach has been criticized as being too simplistic,

and the growth rate criterion has been considered insufficient for the evaluation of the industry's attractiveness.

Similarly, the market share as a yardstick for estimating the competitive position may be inadequate.

Long Range Planning © Heinz Weihrich

9

Another useful matrix for developing a firm's strategy is General Electric's Business Screen. Basically, the GE

matrix consists of two sets of variables: business strengths and industry attractiveness. Each variable is divided

into low, medium and high ratings, resulting in a nine-cell grid. Business strengths, for example, evaluates

size, growth, share, position, profitability, margins and technology position, to mention a few of the items.

Industry attractiveness, on the other hand, is judged in terms of size, market growth, market diversity,

competitive structure, industry profitability and so on. But Charles W. Hofer and Dan Schendel suggest that

the GE Business Screen does not give adequate attention to new industries that are beginning to grow.

Consequently, they suggest a matrix in which the 'competitive position' and their 'stage of product/market

evolution' are plotted. 11 Both matrixes, however, appear to give insufficient attention to the threats and

constraints in the external environment.

The TOWS Matrix, described in this paper, has a wider scope and has different emphases than the ones

mentioned above. This matrix does not replace either the Business Portfolio Matrix, the GE Business Screen,

or the matrix by Hofer and Schendel, but it is proposed as a conceptual framework for a systematic analysis

that facilitates matching the external threats and opportunities with the internal weaknesses and strengths of

the Organization.

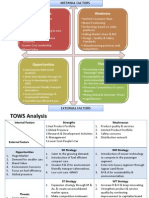

The TOWS Matrix: A Conceptual Model

The process of strategy formulation, shown before in Figure 1, is now surrounding the TOWS Matrix in Figure

2. Preparation of the enterprise profile, Step 1, deals with some basic questions pertaining to the internal and

external environments. Steps 2 and 3, on the other hand, concern primarily the present and future situation in

respect to the external environment. Step 4, the audit of strengths and weaknesses, focuses on the internal

resources of the enterprise. Steps 5 and 6 are the activities necessary to develop strategies, tactics and more

specific actions in order to achieve the enterprise's purpose and overall objectives. During this process

attention must be given to consistency of these decisions with the other steps in the strategy formulation

process. Finally, since an organization operates in a dynamic environment, contingency plans must be prepared

(Step 7).

There are different ways of analyzing the situation. One is to begin with the identification of important

problems. A second approach is to start with determining the purpose and objectives of the firm. A third way is

to focus on opportunities.12 The question may be raised whether one should start with the analysis of the

external environment or with the firm’s internal resources. There is no single answer. Indeed, one may deal

concurrently with the two sets of factors: the external and the internal environment. It is important, therefore,

to remember that the process followed here is just one of several options

Long Range Planning © Heinz Weihrich

10

Step 1. Prepare an Enterprise Profile: (a) the Kind of Business; (b) Geographic Domain;

(c) Competitive Situation; (d) Top Management Orientation

Step 4. Prepare a SW Audit in: (a) Management and Organization;

(b) Operations; (c) Finance; (d) Marketing; (e) Other

Internal Step 5. Develop List Internal Strengths (S): List Internal Weaknesses

Factors Alternatives (W):

(1)

Step 6. Make Strategic (1)

Choices

Consider Strategies,

Tactics, Action

External

Factors Steps 1 to 6. Test for

Consistency. Also Prepare

Contingency Plans.

(Step 7)

List External Opportunities SO: Maxi-Maxi WO: Mini-Maxi

Step 2. Identify and (O):

Evaluate the Following (Consider Risks Also)

Factors:

(a) Economic (1)

(b) Social

(c) Political

(d) Demographic

(e) Products and

Technology

(f) Market and Competition

List External Threats (T): ST: Maxi-Mini WT: Mini-Mini

Step 3. Prepare a

Forecast, Make Predictions (1)

and Assessment of the

Future

*The Steps Are Suggestive and May Vary

Figure 2. Process of corporate strategy and the TOWS analysis

The External Environment. Within the suggested framework, the analysis starts with the external environment.

Specifically, the listing of external threats (T) may be of immediate importance to the firm as some of these

threats (such as the lack of available energy) may seriously threaten the operation of the firm. These threats

should be listed in box 'T' in Figure 2. Similarly, opportunities should be shown in box 'O'.

Threats and opportunities may be found in different areas, but it is advisable to carefully look for the more

common ones which may be categorized as economic, social, political and demographic factors, products and

services, technology, markets and, of course, competition. As mentioned above, the analysis of these factors

must not only pertain to the present but, even more important, the future environment.

Long Range Planning © Heinz Weihrich

11

The Internal Environment. The firm's internal environment is assessed for its strengths (S) and weaknesses

(W), and then listed in the respective spaces in Figure 2. These factors may be found in management and

organization, operations, finance, marketing and in other areas. Since they were previously discussed, they will

not be repeated here.

Strategies, Tactics and Actions. The TOWS Matrix, Figure 2, indicates four conceptually distinct alternative

strategies, tactics and actions. In practice, of course, some of the strategies overlap or they may be pursued

concurrently and in concert. But for the purpose of discussion the focus is on the interactions of four sets of

variables. The primary concern here is strategies, but this analysis could also be applied to the development of

tactics necessary to implement the strategies, and to more specific actions supportive of tactics.

(I) The WT Strategy (mini-mini). In general, the aim of the WT strategy is to minimize both weaknesses and

threats. A company faced with external threats and internal weaknesses may indeed be in a precarious position.

In fact, such a firm may have to fight for its survival or may even have to choose liquidation. But there are, of

course, other choices. For example, such a firm may prefer a merger, or may cut back its operations, with the

intent of either overcoming the weaknesses or hoping that the threat will diminish over time (too often wishful

thinking). Whatever strategy is selected, the WT position is one that any firm will try to avoid.

(2) The WO Strategy (mini--maxi). The second strategy attempts to minimize the weaknesses and to maximize

tile opportunities. A company may identify opportunities ill the external environment but have organizational

weaknesses which prevent the firm from taking advantage of market demands. For example, an auto accessory

company with a great demand for electronic devices to control the amount and timing of fuel injection in a

combustion engine, may lack the technology required for producing these microprocessors. One possible

strategy would be to acquire this technology through cooperation with a firm having competency in this field.

An alternative tactic would be to hire and train people with the required technical capabilities. Of course, the

firm also has the choice of doing nothing, thus leaving the opportunity to competitors.

(3) The ST Strategy (maxi-mini). This strategy is based on the strengths of the organization that can deal with

threats in the environment. The aim is to maximize the former while minimizing the latter. This, however, does

not mean that a strong company can meet threats in the external environment head-on, as General Motors

(GM) realized. In the 1960s, mighty GM recognized the potential threat posed by Ralph Nader, who exposed

the safety hazards of the Corvair automobile. As will be remembered, the direct confrontation with Mr. Nader

caused GM more problems than expected. In retrospect, the initial GM response from Strength was probably

inappropriate. The lesson to be learned is that strengths must often be used with great restraint and discretion.

(4) The SO Strategy (maxi-maxi). Any company would like to be in a position where it can maximize both,

strengths and opportunities. Such an enterprise can lead from strengths, utilizing resources to take advantage

of the market for its products and services. For example, Mercedes Benz, with the technical know-how and the

quality image, can take advantage of the external demand for luxury cars by an increasingly affluent public.

Successful enterprises, even if they temporarily use one of the three previously mentioned strategies, will

attempt to get into a situation where they can work from strengths to take advantage of opportunities. If they

have weaknesses, they will strive to overcome them, making them strengths. If they face threats, they will cope

with them so that they can focus on opportunities.

Long Range Planning © Heinz Weihrich

12

S W

S W O SO WO

S W

O SO WO T ST WT

S W

O SO WO Present Plus T2, etc.

T ST WT

O SO WO T ST WT

Present Plus T1

T ST WT Present

Past Time

Figure 3. Dynamics of TOWS analysis

Time Dimension and the TOWS Matrix

So far, the factors displayed in the TOWS Matrix pertain to analysis at a particular point in time. External and

internal environments are dynamic; some factors change over time while others change very little. Because of

the dynamics in the environment, the strategy designer must Prepare several TOWS Matrixes at different

points in time, as shown in Figure 3. Thus, one may start with a TOWS analysis of the past, continue with an

analysis of the present, and, perhaps most important, focus on different time periods in the future.

Complexity of Interactions of Situational Factors

The conceptual model provides a good framework for identifying relationships, but it can become a complex

process when many factors are being identified. The matrix, shown in Figure 4, is an example of one approach

to identity combinations of relationships which, in turn, may become the basis for strategic choices. (See

Figure 4)

In Figure 4, a '+' indicates a match between the strengths of the company and external opportunities, while an

'0' indicates a weak or nonexistent relationship. Analysis of Figure 4 indicates that Strength No. 1 can be

matched with several opportunities. Similarly, many strengths can be utilized to exploit Opportunity No 7.

Although this figure shows only the relationship between strengths and opportunities, similar tables can be

used for analyzing the other three strategy boxes (WO, ST, WT) shown in Figure 2.

A word of caution is in order here. One cannot simply add up the number of pluses (although especially strong

relationships could be indicated by two pluses such as '+ + ') in each row and in each column to determine the

best match between several strengths and opportunities. Clearly, different relationships may have different

weights in terms of their potential, so each should be carefully evaluated. Still, it is suggested that this matrix

is a relatively simple way of recognizing promising strategies that use the company's strengths to take

advantage of opportunities in the external environment.

Long Range Planning © Heinz Weihrich

13

Strength

Opportunity 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10

1 + 0 + 0 0 + + 0 0 0

2 + 0 0 + 0 0 0 + 0 0

3 0 0 0 + 0 0 0 0 0 +

4 + + + 0 + + 0 + + +

5 + 0 + 0 0 0 + 0 0 0

6 + 0 0 0 + 0 0 0 + +

7 + + 0 + + 0 + + + +

8 0 0 0 0 0 + 0 0 + 0

9 + 0 0 + 0 0 0 + 0 0

10 + + 0 0 + 0 0 0 0 0

Figure 4. Interaction matrix

Application of the TOWS Matrix to Volkswagen

The foregoing discussion of the conceptual framework for strategic planning can be illustrated by an example.

Volkswagen (VW) was chosen because it demonstrates how a successful company experienced great

difficulties in the early 1970s, but then developed a strategy that resulted in an excellent market position in the

late 1970s. The TOWS Matrix shown in Figure 5 will focus on the crucial period from late 1973 to early

1975. The external threats and opportunities pertain mostly to the situation VW faced in the United States, but

a similar situation prevailed in Europe at that time.

The External and Internal Environment

In a situational analysis as conceptualized above, one would first list and analyze the threats and opportunities

in the external environment and the weaknesses and strengths of the enterprise before developing alternative

strategies and tactics. However in this illustration to be concise, the situation and the related actions, shown in

Figure 5, are combined.

Strategies and Tactics

Strategies, as discussed earlier, pertain to major courses of action for the achievement of the enterprise mission

and comprehensive objectives. Tactics, on the other hand, refer to action plans by which strategies are

executed. In practice, and even conceptually, these distinctions are often blurred.

Long Range Planning © Heinz Weihrich

14

Weaknesses and Threats (WT). A company with great weaknesses often has to resort to a survival strategy. VW

could have seriously considered the option of a joint operation with Chrysler or American Motors. Another

alternative would have been to withdraw from the American market altogether. Although in difficulties VW

did not have to resort to a survival strategy because the company still had many strengths. Consequently, a

more appropriate strategy was to attempt to overcome the weaknesses and develop them into strengths. In

other words, the direction was toward the strength-opportunity position (SO) in the matrix shown as Figure 5.

Specifically, the strategy was to reduce the competitive threat by developing a more flexible new product line

that would accommodate the needs and desires of the car-buying public.

Internal Strengths: Internal Weaknesses:

1. Strong R & D and Engineering 1. Heavy Reliance on One Product

2. Strong Sales and Service Network (Although Several Less Successful

3. Efficient Production/Automation Models were Introduced)

Capabilities 2. Rising Costs in Germany

3. No Experience With U.S. Labor

Unions if Building Plant in the U.S.

External Opportunities: SO: WO:

(Also Consider Risks)

1. Develop and Produce Multiproduct 1. Develop Compatible Models for

1. Growing Affluent Market Demands Line with Many Options, in Different Different Price Levels (Ranging from

More Luxurious Cars with Many Price Classes (Dasher, Scirocco, Rabbit, Rabbit to Audi Line) (O1 W1)

Options Audi Line) (O1 S1 S2) 2. To Cope with Rising Costs in

2. Attractive Offers to Build an 2. Build Assembly Plant Using R & D, Germany, Build Plant in U.S., Hiring

Assembly Plant in U.S. Engineering, and U.S. Managers with Experience in

3. Chrysler and American Motors Need Production/Automation Experience (O2 Dealing with U.S. Labor Unions (O2

Small Engines S1 S3) W 2 W 3)

3. Build Engines for Chrysler and AMC

(O3 S3)

External Threats: ST: WT:

1. Exchange Rate: 1. Reduce Effect of Exchange Rate by A. Overcome Weaknesses by Making

Devaluation of Dollar in Relation to Building a Plant in the U.S. (T1 T2 S1 S3) Them Strengths (Move Toward OS

Deutshe Mark (DM) 2. Meet Competition with Advanced Strategy)

2. Competition from Japanese and Design Technology - e.g. Rabbit (T2 T3 1. Reduce Threat of Competition by

U.S. Automakers S1 S2) Developing Flexible Product Line (T2

3. Fuel Shortage and Price 3. Improve Fuel Consumption Through W 1)

Fuel Injection and Develop Fuel Efficient

Diesel Engines (T3 S1) B. Possible Options not Exercised by

VW:

1. Engage in Joint Operation with

Chrysler or AMC

2. Withdraw From U.S. Market

Figure 5. Application of the TOWS matrix to Volkswagen.

This illustrative analysis covers the period from late 1973 to early 1975

Weaknesses and Opportunities (WO). The growing affluence of customers has resulted in 'trading up' to more

luxurious cars. Yet, VW had essentially followed a one-model policy which presented a problem when the

design of the Beetle became obsolete A new model line had to be introduced to reach a wider spectrum of

buyers. In order to minimize the additional costs of a multiproduct line, the building block principle was

employed in the design of the new cars. This allowed using the same parts for different models that ranged

from the relatively low-priced Rabbit to the higher priced Audi line.

Long Range Planning © Heinz Weihrich

15

Another weakness at VW was the rising costs in Germany. For example, in 1973 wages and salaries rose 19

per cent over the previous year. Similarly, increased fuel costs made the shipping of cars to the United States

more costly. This situation favored setting up an assembly plant in the United States. However, this also

created some problems for VW because it had no experience in dealing with American organized labor. To

overcome this weakness, VW's tactic was to recruit managers from Detroit who were capable of establishing

good union relations.

Strengths and Threats (ST). One of the greatest threats to VW was the continuing appreciation of the Deutsche

mark against the dollar. For example, between October 1972 to November 1973 the mark appreciated 35 per

cent. This meant higher prices for the buyer. The result, of course, was a less competitive posture. Japanese and

American automakers obtained an increasingly larger share of the small-car market. To reduce the threats of

competition and the effects of the unfavorable exchange rate, VW was forced to build an assembly plant in the

United States.

Another strategy for meeting competitive pressures was to build on VW's strengths by developing a car based

on advanced-design technology. The result of this effort was the Rabbit, a model with features later adopted by

many other car manufacturers.

The oil crisis in 1973-1974 not only caused a fuel shortage, but also price rises, a trend that has continued. To

meet this threat, VW used its technological capabilities not only to improve its engines (through the use of fuel

injection, for examples), but also to develop the very fuel-efficient Diesel engine. This tactic, which was

congruent with its general strategy, helped improve the firm’s market position.

Strengths and Opportunities (SO). In general, successful firms build on their strengths to take advantage of

opportunities. VW is no exception. Throughout this discussion VW's strengths in research, development,

engineering, and its experience m production technology became evident. These strengths, under the

leadership of Rudolf Leiding, enabled the company to develop a product line that met market demands for an

economical car (the Rabbit, successor to the Beetle), as well as the tastes for more luxurious cars with many

available options (Scirocco and the Audi line).

Eventually the same company's strengths enabled VW to plan and build the assembly facility in New Stanton,

Pennsylvania. Thus, YW could benefit from substantial concessions granted by the state government to attract

VW which, in turn, provided many employment opportunities.

In another tactical move, VW manufactured and sold small engines to Chrysler and American Motors. These

companies urgently needed small engines for installation in their own cars and revenues from these sales

improved the financial position of VW.

Application of the TOWS Matrix to Winnebago Industries Inc.

Winnebago, the largest manufacturer of recreational vehicles (RVs) produced a full line of such vehicles, but

emphasized traditional motor homes. The company, located in Forest City, Iowa, operated a large, modern and

efficient plant.13

The External and Internal Environment

Long Range Planning © Heinz Weihrich

16

The threats and opportunities in the external environment are condensed into the table shown as Figure 6. In

the past, the company had prospered by the high demand for RVs. However, serious threats from competitors

as well as the gasoline shortage could have a great impact on the firm.

While Winnebago has considerable strengths, heavy reliance on essentially one product makes the company

vuh1erable to the external threats.

Strengths: Weaknesses:

1. Identifiable Corporate Name With a 1. Vulnerability Because of Single-

Good Reputation product Company

2. Good Service and Warranty 2. Concentration on Higher Priced

3. Established Dealer Network With Units

Good Dealer Relations 3. Heavy Investment in Toolmaking

4. Extensive Research and Raising Costs of Model Changes

Development Capabilities 4. One-plant Location

5. Automated, Economical Plant 5. No Preparation for Transition from

6. Manufacturing of Most Parts for the Family to Corporate Management

Motor Home

Opportunities: SO: WO:

1. Demand for Smaller RVs 1. Emphasize Smaller, More Efficient 1. Develop and Produce Smaller

2. Development of International Motor Homes (O1 S1 S2 S3 S4 S5 S6) RVs(O1 O2 W1 W2)

Market 2. Expand into Foreign Markets (O2 S1 2. Build Smaller Plants in Different

3. Demand for Low-cost Modular S4) Parts of the Country and Abroad (O1 O2

Housing (FHA Subsidy for Mortgage 3. Diversity into Modular Housing (O3 W 4)

Loans) S1 S4 S6)

Threats: ST: WT:

1. Gasoline Shortage and Higher Prices 1. Diversify into Farm Equipment, 1. Sell the Company (T1 T2 T4 W1 W4

of Gasoline Railroad Cars (T1 T2 T3 S1 S3 S4 S5) W 5)

2. Slackening Demand for RVs 2. Consider Diesel Engines for Motor

3. "Trade-up" Creates Secondary Homes (T1 S4)

Market 3. Make RVs Safer in Anticipation of

4. Increased Competition (GM, Ford, Safety Regulations (e.g. Visibility,

International Harvester, VW, Toyota) Flame Retardant, Crash Resistant,

5. Impending Safety Regulations Brakes) (T4 T5 S6)

Figure 6. Application of the TOWS matrix to Winnebago.

This illustration covers the period of the early 1970s.

Strategies and Tactics

Based on the analysis of the situation, several alternative strategies and tactics are available to Winnebago.

Weaknesses and Threats (WT). The factors in the external environment, particularly the gasoline shortage, the

high fuel prices, the slackening ill demand for recreational vehicles, as well as the increased competition

constitute serious threats to the enterprise. When these threats are seen in relation to the weaknesses, an

alternative would be to sell the company. But this strategic choice would probably be unacceptable to the

family-dominated management group.

Long Range Planning © Heinz Weihrich

17

Weaknesses and Opportunities (WO). Customers in the United States and abroad demand smaller RVs. But

one of the weaknesses of the firm was the heavy reliance on relatively larger and higher-priced units.

Consequently, the development and manufacture of smaller vehicles could take advantage of the demand for

small RVs in a market segment neglected in the past by the firm. Furthermore, smaller plants could be built in

various parts of the country, thus alleviating the comparatively high transportation costs for the smaller RVs

from the factory to the dealers.

Strengths and Threats (ST). To cope with the threats in the external environment the company may use its

strengths. Specifically, diversifying into farm equipment and railroad cars, using the firm's capabilities, can

alleviate problems caused by the slackening demand for RVs due to the secondary market created by the

custom of 'trading up'. Similarly, the use of diesel engines in motor homes can reduce fuel consumption of

these vehicles. Impending safety regulations are expected to make more demands on RV manufacturers.

Rather than reacting to these regulations, Winnebago can use its extensive research and development

capabilities to develop safer vehicles.

Strengths and Opportunities (SO). Winnebago needs to use its strengths to take advantage of the opportunities.

The good reputation of the firm, its service network its research and development as well as the manufacturing

facilities, can be effectively used to produce smaller RVs. Similarly, most of these strengths facilitate the

expansion into the international market. Finally, the firm's capabilities can be used to diversify into modular

housing. But the company has little or no knowledge of the housing market and some difficulties can be

anticipated.

So far, the focus has been on strategy formulation in two product-oriented businesses, Volkswagen and

Winnebago, but does strategic planning also apply to other kinds of organizations?

Who Needs Strategic Planning?

For a long time strategic planning meant making plans in light of the actions or potential actions of an

adversary. In feet it is the military that has had long experience with strategic planning.

In the business world, strategic planning has been used extensively by product-oriented firms. The concern is

about the deployment of resources to make the kind of product the customers want at a price they are willing

to pay. Companies also have to decide whether they want to be a product leader or follow the lead of

innovative competitors.

But to focus only on businesses that snake a distinct product leaves out the important sector of the service

industry. Examples of service businesses are consulting, law, computer service firms, airlines, banks and

theaters. Dan R. E. Thomas drew attention to the fact that strategic management for such enterprises is

significantly different from companies that make a physical product.14

Clearly, to describe services is abstract and more difficult that1 to show and demonstrate a product. There are

two kinds of services: one is equipment-based (e.g. automatic car washes) while the other is people-based (e.g.

consulting). A few illustrations of the latter will indicate some in1plicatiotls for strategic planning. It may be

extremely difficult to evaluate the quality of services of a consulting firm. Consequently, a client tends to

Long Range Planning © Heinz Weihrich

18

employ the services of large consulting firms with established reputations. Unfortunately, this makes it

extremely difficult for a small consulting firm without such an image to enter the market. Another example

pertains to pricing in the service industry. Product-oriented firms usually aim to reduce the cost and price of a

product to increase their market share. In the service industry, however, a low price is often perceived as and

associated with providing poorer quality of professional services.

Does Thomas suggest that strategic management does not apply to the service industry? Certainly not. What is

needed, however, is a change in the thinking pattern away from product-oriented management to the

application of techniques and language peculiar to service-oriented businesses.

Of all the different kinds of organizations, Western governments probably make the least use of strategic

planning. For example, little systematic planning was done to prepare for the oil shortage. There is a tendency

to respond to problems rather than to anticipate them and prepare contingency plans. Many large businesses

now make a situational analysis and establish goals that give the enterprise direction. Why should not the same

managerial concept be applied by our government?

References

1

See the exploratory study by Howard H. Stevenson, Defining corporate strengths and weaknesses. Sloan

Management Review, Spring (1976).

2

K. Andrews, E. Learned, C. R. Christensen and W. Guth, Business Policy. Text and Cases, Richard D. Irwin,

Homewood, Illinois (1965).

3

A. Chandler, Strategy and Structure. Chapters in the History of American Industrial Enterprise, MIT Press,

Cambridge, Massachusetts (1962).

4

G. A. Steiner and J. B. M Miner, Management Policy and Strategy, Macmillan, New York (1977).

5

R. Vancil, Strategy formulation in complex organizations, Sloan Management Review, in Peter Lorange and

Richard F. Vancil, Strategic Planning Systems, Prentice-Hall, Englewood Cliffs. NJ (1977).

6

H. l. Ansoff, Corporate Strategy, McGraw-Hill, New York (1 965).

7

C. W. Hofer and D. Schendel, Strategy Formulation: Analytical Concepts, West Publishing. St. Paul (1978).

8

H. Koontz, C. O'Donnell and H. Weihrich, Management, 7th ed., McGraw-Hill, New York (1980), p. 847. For

additional meanings, see Roger Evered, ‘The Strategic Decision Process', in Don Hellriegel and John W. Slocum,

Or., eds., Management in the World Today, Addison Wesley, Reading, Massachusetts (1975).

9

For an excellent discussion of the various approaches to forecasting; see Spyros Makridakis and Steven C.

Wheelwright, Forecasting: issues and challenges for marketing management Journal of Marketing, October (1977)

in Harold Koontz, Cyril O'Donnell and Heinz Weihrich, Management: A Book of Readings, 5th ed., McGraw-Hill,

New York (1980).

Long Range Planning © Heinz Weihrich

19

10

J. Wall, What the competition is doing: your need to know, Harvard Business Review, November-December

(1974).

11

Hofer and Schendel, op. cit.. Chapter 2.

12

See, for example. the comparison of steps suggested by different authors in G. A. Steiner and J. B. Miner, op cit.,

Chapter 8.

13

H. E. R. Uyterhoeven, R. W. Ackerman and J. W. Rosenblum, Strategy and Organization, Richard D. Irwin,

Homewood, Illinois (1977).

14

D. R. E. Thomas, Strategy is different in service businesses, Harvard Business Review, July-August (1978).

Long Range Planning © Heinz Weihrich

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- TOWS Matrix Analysis for Apple and SamsungDocument16 pagesTOWS Matrix Analysis for Apple and SamsungAbinash Biswal67% (3)

- Swot To TowsDocument16 pagesSwot To Towsmanochm100% (1)

- Swot TowsDocument12 pagesSwot TowsDrAnand BajpaiPas encore d'évaluation

- Tows AnalysisDocument6 pagesTows AnalysisSahil Chhabra0% (1)

- Swot and Tows Analysis of Samsun2Document9 pagesSwot and Tows Analysis of Samsun2sangeetha100% (2)

- TOWS AnalysisDocument11 pagesTOWS AnalysisRehan Siddiqui50% (2)

- The Essentials of Strategic Management Concepts Clearly ExplainedDocument14 pagesThe Essentials of Strategic Management Concepts Clearly ExplainedAmit KuPas encore d'évaluation

- Full Assignment of MPDocument70 pagesFull Assignment of MPmandeep1985100% (1)

- Strategic Analysis For SamsungDocument19 pagesStrategic Analysis For SamsungJoanne RomaPas encore d'évaluation

- Tata Motors SWOT TOWS CPM MatrixDocument6 pagesTata Motors SWOT TOWS CPM MatrixPreetam Pandey33% (3)

- Introduction and ObjectiveDocument5 pagesIntroduction and ObjectiveKheang PhannaPas encore d'évaluation

- cs4 2Document5 pagescs4 2Hoang Lee40% (5)

- VRIO FrameworkDocument15 pagesVRIO FrameworkTarun AhujaPas encore d'évaluation

- TowsDocument1 pageTowsPraveen SahuPas encore d'évaluation

- Swot TowsDocument23 pagesSwot TowsKristel Mae AlagarPas encore d'évaluation

- Porter's Five Forces Vs Resource Based ViewDocument13 pagesPorter's Five Forces Vs Resource Based ViewMohi Asad95% (21)

- GE Matrix Explained: Analyzing Business Units by Strength and Market AttractivenessDocument26 pagesGE Matrix Explained: Analyzing Business Units by Strength and Market AttractivenessFijo JosePas encore d'évaluation

- Group 1 Case Study 7 - AcerDocument38 pagesGroup 1 Case Study 7 - AcerVõ Thị Xuân HạnhPas encore d'évaluation

- Application of SPACE MatrixDocument11 pagesApplication of SPACE Matrixdecker444975% (4)

- Horizontal and Vertical IntegrationDocument9 pagesHorizontal and Vertical IntegrationAmna Rasheed100% (1)

- Strategy: Choices and Change MN6003 Session 17 Strategic Change Context Lecturer: XXXXXXDocument29 pagesStrategy: Choices and Change MN6003 Session 17 Strategic Change Context Lecturer: XXXXXXVladimir LosenkovPas encore d'évaluation

- Strategy Implementation and ExecutionDocument57 pagesStrategy Implementation and ExecutionAjil RafaelPas encore d'évaluation

- David sm13 PPT 06Document44 pagesDavid sm13 PPT 06john brownPas encore d'évaluation

- Tailoring Strategy To Fit Specific Industry and Company SituationsDocument53 pagesTailoring Strategy To Fit Specific Industry and Company Situationsmrmaheshnaik86% (14)

- Towards A Dynamic Theory of Strategy by Michael PorterDocument39 pagesTowards A Dynamic Theory of Strategy by Michael Porterpdforever100% (1)

- BCG Matrix of LGDocument22 pagesBCG Matrix of LGsumancalls71% (14)

- Five Forces Analysis.Document3 pagesFive Forces Analysis.kuntodarpito100% (2)

- Porter's Five Forces ModelDocument5 pagesPorter's Five Forces ModelPrajakta GokhalePas encore d'évaluation

- CH 6 AMS - Understanding The Organizational Resource BaseDocument39 pagesCH 6 AMS - Understanding The Organizational Resource BaseAde TenyomPas encore d'évaluation

- Supply Chain Management Definitions and Theories PerspectiveDocument14 pagesSupply Chain Management Definitions and Theories PerspectiveakyregisterPas encore d'évaluation

- Lenovo Case StudyDocument5 pagesLenovo Case Studycharantejch100% (1)

- TOWS MatrixDocument6 pagesTOWS MatrixNarendra VaidyaPas encore d'évaluation

- Carol Tomé's Leadership SkillsDocument6 pagesCarol Tomé's Leadership SkillsAlisa BisopPas encore d'évaluation

- A Business Model Innovation TypologyDocument31 pagesA Business Model Innovation Typologyn1i1Pas encore d'évaluation

- Strategic MAnagment and Strategic CompetitivenessDocument20 pagesStrategic MAnagment and Strategic Competitivenessrohan_jangid8Pas encore d'évaluation

- Toyota Motor Corporation Market AnalysisDocument4 pagesToyota Motor Corporation Market AnalysisRandy Teofilo MbaPas encore d'évaluation

- Strategic Management Quiz 2 PDFDocument4 pagesStrategic Management Quiz 2 PDFXainab AmirPas encore d'évaluation

- Strategy Implementation DriversDocument7 pagesStrategy Implementation DriversMohemmad Naseef0% (1)

- Strategy Review, Evaluation and ControlDocument27 pagesStrategy Review, Evaluation and Controldonna mendozaPas encore d'évaluation

- Analyzing a Firm's Internal Resources Using the VRIO FrameworkDocument10 pagesAnalyzing a Firm's Internal Resources Using the VRIO FrameworkPrajakta GokhalePas encore d'évaluation

- Uniqlos Marketing Plan To Expand To VietDocument42 pagesUniqlos Marketing Plan To Expand To Vietkhanh nguyenPas encore d'évaluation

- Analyzing The Internal Environment of The FirmDocument7 pagesAnalyzing The Internal Environment of The FirmRegine Balaan Anua100% (1)

- Brand Positioning GuideDocument30 pagesBrand Positioning GuidePruthviraj RathorePas encore d'évaluation

- A Strategic Plan Nokia A Strategic Plan Nokia12564 PDFDocument32 pagesA Strategic Plan Nokia A Strategic Plan Nokia12564 PDFImam MohamedPas encore d'évaluation

- Chapter 3 - Performance Management and Strategic PlanningDocument29 pagesChapter 3 - Performance Management and Strategic PlanningDr.Nadeem SyedPas encore d'évaluation

- 10 Reasons Strategic Plans FailDocument3 pages10 Reasons Strategic Plans FailmatloobilahiPas encore d'évaluation

- MKTG MGMT CH8 MARKET SEGMENTATIONDocument16 pagesMKTG MGMT CH8 MARKET SEGMENTATIONSalman PreeomPas encore d'évaluation

- A Critique of Competitive AdvantageDocument12 pagesA Critique of Competitive AdvantagePhilippe HittiPas encore d'évaluation

- Strategy Analysis and ChoiceDocument10 pagesStrategy Analysis and ChoiceMichelle EsternonPas encore d'évaluation

- IBA Marketing Management Course OutlineDocument12 pagesIBA Marketing Management Course OutlineSauban AhmedPas encore d'évaluation

- Strategy Formulation and ImplementationDocument33 pagesStrategy Formulation and ImplementationDat Thanh Bui100% (7)

- 1 - AMAZON SolutionDocument10 pages1 - AMAZON SolutionNono DedePas encore d'évaluation

- Cost Leadership, Differentiation and Niche Strategies AssignmentDocument19 pagesCost Leadership, Differentiation and Niche Strategies AssignmentDoris AchengPas encore d'évaluation

- The TOWS Matrix A Tool For Situational AnalysisDocument13 pagesThe TOWS Matrix A Tool For Situational Analysisanon_174427911Pas encore d'évaluation

- The Strategic Planning ProcessDocument14 pagesThe Strategic Planning ProcessDESH RAJ BHANDARIPas encore d'évaluation

- Ads553 Chapter 2Document39 pagesAds553 Chapter 2marcalynPas encore d'évaluation

- Management Chap 3Document22 pagesManagement Chap 3irshad_aliPas encore d'évaluation

- 1 Strategic-ManagementDocument25 pages1 Strategic-Managementami tyPas encore d'évaluation

- Using Critical Success Factors in Planning Per V. Jenster PDFDocument8 pagesUsing Critical Success Factors in Planning Per V. Jenster PDFNishantha BandaraPas encore d'évaluation

- Strategic Management and Business Management FDocument129 pagesStrategic Management and Business Management FmushtaquermPas encore d'évaluation

- Charu Kejriwal DissertationDocument87 pagesCharu Kejriwal Dissertationmr.avdheshsharmaPas encore d'évaluation

- Analysis of Working Capital For Bharti... by Charu Kejriwal... EDITEDDocument81 pagesAnalysis of Working Capital For Bharti... by Charu Kejriwal... EDITEDmr.avdheshsharma67% (3)

- Indian Automobile Industry AnalysisDocument41 pagesIndian Automobile Industry Analysismr.avdheshsharma85% (26)

- Beyond Leveraged Losses: The Balance Sheet Effects of The Home Price DownturnDocument45 pagesBeyond Leveraged Losses: The Balance Sheet Effects of The Home Price Downturnbunchamunk100% (2)

- jÖnkÖping International Business SchoolDocument73 pagesjÖnkÖping International Business Schoolmr.avdheshsharmaPas encore d'évaluation

- 6th Central Pay Commission Salary CalculatorDocument15 pages6th Central Pay Commission Salary Calculatorrakhonde100% (436)

- Indian Stock MarketsDocument13 pagesIndian Stock Marketsmr.avdheshsharmaPas encore d'évaluation

- DNA Computing: Bachelor of Technology in Computer Science & Engineering byDocument34 pagesDNA Computing: Bachelor of Technology in Computer Science & Engineering bymr.avdheshsharmaPas encore d'évaluation

- The TOWS Matrix - A Tool For Situational AnalysisDocument19 pagesThe TOWS Matrix - A Tool For Situational Analysismr.avdheshsharma100% (6)

- Sub Sector / Value Chain Analysis For Livelihood InterventionDocument24 pagesSub Sector / Value Chain Analysis For Livelihood InterventionS.Rengasamy100% (4)

- A Bottom-Up Analysis of Including Aviation Within The EU's Emissions Trading SchemeDocument29 pagesA Bottom-Up Analysis of Including Aviation Within The EU's Emissions Trading SchemeTyndall Centre for Climate Change ResearchPas encore d'évaluation

- A Report On Banking Sector Analysis - Factors Affecting Indian Banking SectorDocument53 pagesA Report On Banking Sector Analysis - Factors Affecting Indian Banking Sectorchinushibbu83% (18)

- ProteinShop: A Tool For Protein Structure Prediction and ModelingDocument27 pagesProteinShop: A Tool For Protein Structure Prediction and Modelingmr.avdheshsharmaPas encore d'évaluation

- Project - Online Exam SystemDocument27 pagesProject - Online Exam SystemsanuvijayPas encore d'évaluation

- Networking in LinuxDocument52 pagesNetworking in Linuxmr.avdheshsharmaPas encore d'évaluation

- Protein StructureDocument22 pagesProtein Structureapi-3706290100% (1)

- Near Field CommunicationDocument26 pagesNear Field Communicationmr.avdheshsharmaPas encore d'évaluation

- Protein Structure (Pauling)Document26 pagesProtein Structure (Pauling)mr.avdheshsharmaPas encore d'évaluation

- Lecture Presentation - Protein MetabolismDocument8 pagesLecture Presentation - Protein Metabolismmr.avdheshsharma100% (1)

- Honeypots CorrectDocument35 pagesHoneypots Correctmr.avdheshsharmaPas encore d'évaluation

- Time Keeping SystemDocument1 pageTime Keeping Systemmr.avdheshsharmaPas encore d'évaluation

- 6th Central Pay Commission Salary CalculatorDocument15 pages6th Central Pay Commission Salary Calculatorrakhonde100% (436)

- Promoters and Management GroupDocument1 pagePromoters and Management Groupmr.avdheshsharmaPas encore d'évaluation

- Blu Ray DiscDocument23 pagesBlu Ray Discmr.avdheshsharma100% (2)

- Summer Training Project ReportDocument2 pagesSummer Training Project Reportmr.avdheshsharma100% (1)

- Data Findings & Analysis: Recruitment at Hind Lamps LTDDocument3 pagesData Findings & Analysis: Recruitment at Hind Lamps LTDmr.avdheshsharmaPas encore d'évaluation

- Cell SignalingDocument29 pagesCell Signalingmr.avdheshsharma100% (1)

- QDocument2 pagesQmr.avdheshsharmaPas encore d'évaluation

- PersonnelDocument1 pagePersonnelmr.avdheshsharmaPas encore d'évaluation

- Industrial RelationDocument1 pageIndustrial Relationmr.avdheshsharmaPas encore d'évaluation

- Module For Chapter 2 - Strategic Human Resource Management - MGT101-HRMDocument5 pagesModule For Chapter 2 - Strategic Human Resource Management - MGT101-HRMTricia Claire BarraquioPas encore d'évaluation

- Explore Business IdeasDocument39 pagesExplore Business IdeasAl Cheeno AnonuevoPas encore d'évaluation

- Course Profile: Organizational Studies: Organizational Behaviour and Human ResourcesDocument48 pagesCourse Profile: Organizational Studies: Organizational Behaviour and Human Resourcestome440% (1)

- Sop Kredensial PpaDocument8 pagesSop Kredensial PpaKIRANADEWIPas encore d'évaluation

- Gender and DevelopmentDocument17 pagesGender and DevelopmentAngeline TrayfalgarPas encore d'évaluation

- Anna University TQM May June (8 TH Sem) 05Document2 pagesAnna University TQM May June (8 TH Sem) 05Deepak100% (1)

- Implementing A Performance Management SystemDocument25 pagesImplementing A Performance Management SystemSuryansh Gupta50% (2)

- 2014 - Academics - Sport and Development in AfricaDocument171 pages2014 - Academics - Sport and Development in AfricatiaPas encore d'évaluation

- 05 Handout 1Document4 pages05 Handout 1Shedy GalorportPas encore d'évaluation

- Assessing Student Learning EffectivelyDocument3 pagesAssessing Student Learning EffectivelyDhon ValePas encore d'évaluation

- Chapter 6 Mixed Methods ResearchDocument18 pagesChapter 6 Mixed Methods ResearchMr XPas encore d'évaluation

- Operating Risk Assessment For Underground Metal Mining Systems - Overview and DiscussionDocument26 pagesOperating Risk Assessment For Underground Metal Mining Systems - Overview and DiscussionIonut Patras100% (1)

- Pilot Study and Action ResearchDocument3 pagesPilot Study and Action ResearchdingolapyPas encore d'évaluation

- Acpa Ethical Principals and StandardsDocument7 pagesAcpa Ethical Principals and Standardsapi-310813184Pas encore d'évaluation

- Procedures For On-Site EvaluationDocument7 pagesProcedures For On-Site EvaluationEnes BuladıPas encore d'évaluation

- Ijresm V4 I12 29Document13 pagesIjresm V4 I12 29PANAO, BABYLYN T.Pas encore d'évaluation

- PDFDocument12 pagesPDFrubel-buPas encore d'évaluation

- NB Guidelines and Standards-Educational Planning For Students With ExceptionalitiesDocument34 pagesNB Guidelines and Standards-Educational Planning For Students With Exceptionalitiesapi-249986210Pas encore d'évaluation

- Calibration Essentials Ebook PDFDocument64 pagesCalibration Essentials Ebook PDFsolbahia100% (1)

- Maintenance Planner Day2 DetailsDocument7 pagesMaintenance Planner Day2 Detailsahmed mahmoudPas encore d'évaluation

- Cedar Rapids Seeks Proposals for Professional IT ServicesDocument16 pagesCedar Rapids Seeks Proposals for Professional IT ServicesnabdelbaqiPas encore d'évaluation

- SQA Week 1Document15 pagesSQA Week 1sabaPas encore d'évaluation

- Washington State Performance GuideDocument45 pagesWashington State Performance GuideedrialdePas encore d'évaluation

- Chapter 2 SQADocument13 pagesChapter 2 SQAInam Ullah KhanPas encore d'évaluation

- Course Outline Spring-2020: Department of Management Sciences University of GujratDocument7 pagesCourse Outline Spring-2020: Department of Management Sciences University of Gujrat17460920-076Pas encore d'évaluation

- Medical Coding Apps For The Iphone and IpadDocument20 pagesMedical Coding Apps For The Iphone and IpadMedicalApps100% (1)

- Chap 13Document28 pagesChap 13Aamir ChohanPas encore d'évaluation

- JOIN LUISS BUSINESS SCHOOLDocument2 pagesJOIN LUISS BUSINESS SCHOOLAri HastantoPas encore d'évaluation

- New Bsbins603Document24 pagesNew Bsbins603Samit ShresthaPas encore d'évaluation

- CCCJ Social Work Practicum Guide 2017Document24 pagesCCCJ Social Work Practicum Guide 2017Brittany OliphantPas encore d'évaluation

- Generative AI: The Insights You Need from Harvard Business ReviewD'EverandGenerative AI: The Insights You Need from Harvard Business ReviewÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (2)

- Scaling Up: How a Few Companies Make It...and Why the Rest Don't, Rockefeller Habits 2.0D'EverandScaling Up: How a Few Companies Make It...and Why the Rest Don't, Rockefeller Habits 2.0Pas encore d'évaluation

- Lean Thinking: Banish Waste and Create Wealth in Your Corporation, 2nd EdD'EverandLean Thinking: Banish Waste and Create Wealth in Your Corporation, 2nd EdÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (17)

- Small Business For Dummies: 5th EditionD'EverandSmall Business For Dummies: 5th EditionÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (10)

- SYSTEMology: Create time, reduce errors and scale your profits with proven business systemsD'EverandSYSTEMology: Create time, reduce errors and scale your profits with proven business systemsÉvaluation : 5 sur 5 étoiles5/5 (48)

- How to Grow Your Small Business: A 6-Step Plan to Help Your Business Take OffD'EverandHow to Grow Your Small Business: A 6-Step Plan to Help Your Business Take OffÉvaluation : 5 sur 5 étoiles5/5 (61)

- Scaling Up: How a Few Companies Make It...and Why the Rest Don't (Rockefeller Habits 2.0 Revised Edition)D'EverandScaling Up: How a Few Companies Make It...and Why the Rest Don't (Rockefeller Habits 2.0 Revised Edition)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (13)

- Impact Networks: Create Connection, Spark Collaboration, and Catalyze Systemic ChangeD'EverandImpact Networks: Create Connection, Spark Collaboration, and Catalyze Systemic ChangeÉvaluation : 5 sur 5 étoiles5/5 (8)

- Systems Thinking: A Guide to Strategic Planning, Problem Solving, and Creating Lasting Results for Your BusinessD'EverandSystems Thinking: A Guide to Strategic Planning, Problem Solving, and Creating Lasting Results for Your BusinessÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (80)

- Sales Pitch: How to Craft a Story to Stand Out and WinD'EverandSales Pitch: How to Craft a Story to Stand Out and WinÉvaluation : 5 sur 5 étoiles5/5 (1)

- HBR's 10 Must Reads on Strategy (including featured article "What Is Strategy?" by Michael E. Porter)D'EverandHBR's 10 Must Reads on Strategy (including featured article "What Is Strategy?" by Michael E. Porter)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (11)

- The Toyota Way (Second Edition): 14 Management Principles from the World's Greatest ManufacturerD'EverandThe Toyota Way (Second Edition): 14 Management Principles from the World's Greatest ManufacturerÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (121)

- Artificial Intelligence: The Insights You Need from Harvard Business ReviewD'EverandArtificial Intelligence: The Insights You Need from Harvard Business ReviewÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (104)

- How to Grow Your Small Business: A 6-Step Plan to Help Your Business Take OffD'EverandHow to Grow Your Small Business: A 6-Step Plan to Help Your Business Take OffPas encore d'évaluation

- Blue Ocean Strategy, Expanded Edition: How to Create Uncontested Market Space and Make the Competition IrrelevantD'EverandBlue Ocean Strategy, Expanded Edition: How to Create Uncontested Market Space and Make the Competition IrrelevantÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (387)

- Amp It Up: Leading for Hypergrowth by Raising Expectations, Increasing Urgency, and Elevating IntensityD'EverandAmp It Up: Leading for Hypergrowth by Raising Expectations, Increasing Urgency, and Elevating IntensityÉvaluation : 5 sur 5 étoiles5/5 (50)

- HBR Guide to Setting Your StrategyD'EverandHBR Guide to Setting Your StrategyÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (18)

- Tax-Free Wealth: How to Build Massive Wealth by Permanently Lowering Your TaxesD'EverandTax-Free Wealth: How to Build Massive Wealth by Permanently Lowering Your TaxesPas encore d'évaluation

- The 10X Rule: The Only Difference Between Success and FailureD'EverandThe 10X Rule: The Only Difference Between Success and FailureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (289)

- Elevate: The Three Disciplines of Advanced Strategic ThinkingD'EverandElevate: The Three Disciplines of Advanced Strategic ThinkingÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (3)

- Strategic Roadmap: An Intentional, Memorable Approach to Achieving SuccessD'EverandStrategic Roadmap: An Intentional, Memorable Approach to Achieving SuccessPas encore d'évaluation

- HBR's 10 Must Reads on Business Model InnovationD'EverandHBR's 10 Must Reads on Business Model InnovationÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (12)

- Understanding Michael Porter: The Essential Guide to Competition and StrategyD'EverandUnderstanding Michael Porter: The Essential Guide to Competition and StrategyÉvaluation : 5 sur 5 étoiles5/5 (24)

- HBR's 10 Must Reads on Managing Yourself, Vol. 2D'EverandHBR's 10 Must Reads on Managing Yourself, Vol. 2Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (11)