Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

What Factors Have Contributed To Globalisation in Recent Years?

Transféré par

shariz5000 évaluation0% ont trouvé ce document utile (0 vote)

31 vues5 pagesGlobalisation

Titre original

5F173131A1478B73B9D918395207B05C-2

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Formats disponibles

PDF, TXT ou lisez en ligne sur Scribd

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentGlobalisation

Droits d'auteur :

© All Rights Reserved

Formats disponibles

Téléchargez comme PDF, TXT ou lisez en ligne sur Scribd

0 évaluation0% ont trouvé ce document utile (0 vote)

31 vues5 pagesWhat Factors Have Contributed To Globalisation in Recent Years?

Transféré par

shariz500Globalisation

Droits d'auteur :

© All Rights Reserved

Formats disponibles

Téléchargez comme PDF, TXT ou lisez en ligne sur Scribd

Vous êtes sur la page 1sur 5

What factors have contributed to

globalisation in recent years?

by Maziar Homayounnejad, Queen Elizabeth's School, Barnet.

Globalisation can be defined: as the growing interdependence of world economies.

This definition has two main features:

Firstly, the fact that globalisation is not an end result, but is a continuing process that keeps

growing and gathering pace

Secondly, there is the idea that globalisation leads to world economies becoming more reliant

upon each other.

The first writer to use the term globalisation in anything like its modern form was the American

economist Theodore Levitt in 1983. He argued that all around the world people's tastes seemed to be

converging and that firms were now beginning to offer standardised products in all countries.

The question to be addressed here is how this emerging trend came into being, thus it is important

for us to understand the factors driving this process of globalisation. We will consider the reduction

and removal of trade barriers; transport costs; growth of the internet; growth of multinational

corporations; and the development of trading blocs.

The Reduction and Removal of Trade Barriers

Since the end of World War II, the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) and its successor,

the WTO, have reduced tariffs and various non-tariff barriers to trade, enabling more countries to

exploit their comparative advantage.

Developing countries continue to drive the global recovery, but their output growth is also expected

to moderate to 6.0 per cent during 2011-2012, down from 7.0 per cent in 2010, because of the

slowdown in the advanced countries and phasing out of stimulus measures. Developing Asia, led by

China and India, continues to show the strongest growth performance, but some moderation (to

around 7 per cent) is expected in 2011 and 2012.

High unemployment is the Achilles heel for the recovery

The Uruguay Round of trade negotiations (1986-94) was the real watershed for global trade. Here, a

large package of measures was agreed, which freed up trade in both goods and in services. As a

result, the volume of world trade rose by 50% just in the 6 years following the conclusion of the

Uruguay Round.

Equally important is the number of countries taking part in free trade negotiations. In 1948, when the

GATT treaty became effective, there were only 23 Contracting Parties to the agreement. Just over 60

years later, there are now 153 member states of the WTO who all enjoy the benefits of free trade

based on the principle of comparative advantage.

Accordingly, between 1948 and 2008, trade rose from only 5% to a massive >25% of world GDP.

This means countries are becoming more and more reliant upon each other for their export earnings,

income and employment. This exposes them to the international trade multiplier, where domestic

business cycles become vulnerable to changes in the level of economic activity in the rest of the

world.

However, the recent global recession brought international trade onto a downhill path. With world

demand for all goods and services in decline and a temptation by many countries to impose

protectionist barriers in order to protect jobs, the WTO in 2009 forecast a 9% fall in global trade

flows. This is the first time since the end of World War II that trade has gone into decline and has

been termed 'deglobalisation'.

Transport Costs

Improvements in containerisation have drastically lowered freight charges. For example, over the last

25 years, sea transport unit costs have fallen by over 70%, while air-freight costs have fallen by 3-

4% year-on-year. The result has been a boost in trade flows, as transport costs are now less likely to

cancel out the gains from comparative advantage.

However the rise in sea and air transport has also caused great concern over the negative

externalities of global trade. Indeed recent estimates that CO2 emissions will rise by >70% by 2020

have led to calls for green taxes on shipping transport. If these go ahead, they will partially offset the

falls in transport costs, hence the process of globalisation will be dampened to some extent.

Growth of the Internet

The growth of the internet has increased e-commerce, enabling firms of all sizes to compete more

easily in global markets. Essentially, the internet acts as a 24-hour shop front allowing consumers all

over the world to buy products online and around the clock, from whoever happens to be offering the

best deal. For the firm, it therefore provides cheap marketing with global reach, such that even small

local businesses can afford to serve customers abroad.

Accordingly, the internet gives all firms - both domestic and MNCs alike - easier access to foreign

markets. We now find that international trade is no longer the sole preserve of the larger firm. It can

now even be undertaken by, say, a local antiques shop, which can either set up its own website or

sell through an online auction like eBay. The end result is of course that more countries become

interdependent and reliant upon each other for the sale and provision of goods and services.

However, despite the 'global reach' of the internet, which ostensibly makes it a potent driver of

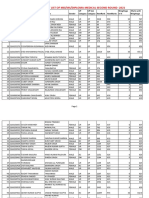

globalisation, we see a very uneven spread of internet usage around the world. The figures below

demonstrate how effectively the developed countries are embracing the World Wide Web as a tool for

wealth creation, while the developing countries are being left behind to varying degrees.

Source: Adapted from www.internetworldstats.com

This is perhaps understandable: given the costly infrastructure and the hardware required to access

the internet, poor countries such as those in Sub-Saharan Africa will clearly have little incentive to

take part in the internet revolution. Not surprisingly, these regions will continue to focus on basic

survival needs rather than investing in sophisticated IT equipment, until such time as they can

adequately address their more immediate concerns.

Quite apart from this, there are censorship laws in many Middle Eastern and Asian countries (such as

Saudi Arabia and China) which further limit the ability of the internet to forge links between world

economies.

Accordingly, while the internet revolution has propelled us into a whole new era of globalisation over

the past 15 years or so, this has mainly been skewed towards the rich liberal democracies, whose

political and economic infrastructures have been more receptive to this relatively new technology. It

is therefore arguable that the growth of the internet has made a substantial, though imbalanced

contribution towards the process of globalisation.

Growth of Multinational Corporations (MNCs)

An MNC is a firm which owns production facilities in at least one country outside its home state. MNCs

are said to epitomise global interdependence, as they often span across a number of different

countries, with sales, profits and a smooth flow of production being reliant on several countries at

once. The question, however, is how MNCs have come about.

Firstly, with lower transport costs firms are more easily able to disperse their production processes

around the world to take advantage of varying cost conditions. For example, it is now more viable for

car manufacturers to produce simple components like windscreens and door mirrors in cheap labour

countries, than to have these components transported into the UK where they are assembled onto

the finished good. The transport costs are now so small (see above) that they no longer cancel out

the cost savings from producing components overseas.

Secondly, falls in communication costs have also facilitated a dispersal of the production process. For

example, when asked why there is an increasing number of Western MNCs relocating their ancillary

services to India, most people will cite the country's cheap but increasingly educated workforce.

However, the Indian workforce was both cheap and highly educated during the '80s and '90s, yet call

centres have only been relocating there during the last 10 years. The reason would therefore seem to

be falling telephone charges. With international calls to Asia costing only a few pence per minute (as

opposed to a few pounds during the '80s and '90s), India's comparative advantage in labour intensive

services is much clearer now and is no longer being cancelled out by high communication costs.

Both types of cost reductions (i.e. falls in transport costs and communication costs) are said to have

caused the death of distance, which has enabled the so-called 'hollowing out' effect. Namely,

company operations are being dispersed around the world as firms carry out efficiency-seeking FDI.

Hence, MNCs based in the UK or US have become reliant upon factor inputs in a number of different

countries. And nations which consume the goods produced by an MNC are effectively relying on a

number of different countries, both for the production and delivery of the good and for the customer

service that goes with it.

To illustrate the growth of MNCs, in 1969 there were around 7,000 of them in the world; today, there

are 82,000 MNCs, whose subsidiaries and foreign affiliates are responsible for around 33% of world

exports (UNCTAD: World Investment Report 2009). Furthermore, as the opportunities to outsource

continue to grow, so does the number of new MNCs coming into existence.

The Development of Trading Blocs

Also known as a 'regional trade agreement' (RTAs), a trading bloc is essentially a group of countries

that remove tariffs and quotas on trade between themselves. In some cases, this abolition of internal

barriers to trade is replaced with a common external tariff against non-members of the RTA.

In recent years, the number and size of trading blocs have increased dramatically. For example,

between 1948 and 1994 the GATT received 124 notifications of RTAs; however, since the WTO was

established in 1995, over 240 additional notifications have been received. This includes the

establishment of new RTAs, as well as the accessions of new countries into existing ones like the EU

(which, since 2004, expanded from 15 to 27 member states).

Trading blocs promote global interdependence through trade creation. Namely, where the dismantling

of internal trade barriers causes a country to switch from purchasing goods from a high-cost producer

(often in the domestic market) to a low-cost producer elsewhere in the trading bloc. An example can

be seen with the UK's membership of the EU where, since 1973, consumers have had access to

cheaper wine from France, free from any tariffs or quotas.

However, trading blocs do not always promote trade; those that impose a common external tariff

against non-members also cause trade diversion. That is, where the common external tariff causes a

country to switch from a low-cost producer outside the trading bloc, to a higher cost producer inside

the bloc. Again, the UK's membership of the EU provides a good illustration of this. Before 1973,

British consumers had easy access to agricultural products from New Zealand, especially lamb and

apples. However, upon joining the EU all agricultural products from outside the bloc, including those

from New Zealand, became subject to very high tariffs (all part of the Common Agricultural Policy).

Many UK consumers have therefore switched to British or other EU produce, with the consequence

that our reliance on countries outside the EU has fallen greatly.

Conclusion

Since the end of World War II, and particularly in the past 10 to 15 years, we have seen the process

of globalisation drive forward at an unprecedented rate. A large part of this is down to legal, political

and technological developments which have facilitated trade across national boundaries, both in

products and in factor inputs. However, when evaluating the effectiveness of these factors in

promoting global interdependence, it is important to bear in mind that many of them have their

drawbacks and limitations. Nonetheless, globalisation continues to gather pace in the 21st century

and with technology becoming cheaper and more advanced, we can only expect the process of

globalisation to propel further forward in the years to come.

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- Plunder Case vs. GMA On PCSO FundsDocument10 pagesPlunder Case vs. GMA On PCSO FundsTeddy Casino100% (1)

- 6th Central Pay Commission Salary CalculatorDocument15 pages6th Central Pay Commission Salary Calculatorrakhonde100% (436)

- Hard Core Power, Pleasure, and The Frenzy of The VisibleDocument340 pagesHard Core Power, Pleasure, and The Frenzy of The VisibleRyan Gliever100% (5)

- The World Trade Organization: A Beginner's GuideD'EverandThe World Trade Organization: A Beginner's GuideÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1)

- Gear Krieg - Axis Sourcebook PDFDocument130 pagesGear Krieg - Axis Sourcebook PDFJason-Lloyd Trader100% (1)

- Case 104-Globe Mackay Cable and Radio Corp V NLRCDocument1 pageCase 104-Globe Mackay Cable and Radio Corp V NLRCDrobert EirvenPas encore d'évaluation

- Retirement Pay PDFDocument3 pagesRetirement Pay PDFTJ CortezPas encore d'évaluation

- Amplify University TrainingDocument11 pagesAmplify University Trainingshariz500100% (1)

- International Business Management or Business EnviormentDocument141 pagesInternational Business Management or Business Enviormentonly_vimaljoshi100% (2)

- The Role of Multipurpose Cooperatives in Socio-Economic Empowerment in Gambella Town, EthiopiaDocument80 pagesThe Role of Multipurpose Cooperatives in Socio-Economic Empowerment in Gambella Town, EthiopiaCain Cyrus Mondero100% (1)

- Edexcel GCE Core 4 Mathematics C4 6666/01 Advanced Subsidiary Jun 2005 Question PaperDocument24 pagesEdexcel GCE Core 4 Mathematics C4 6666/01 Advanced Subsidiary Jun 2005 Question Paperrainman875Pas encore d'évaluation

- USAID Civil Society Engagement ProgramDocument3 pagesUSAID Civil Society Engagement ProgramUSAID Civil Society Engagement ProgramPas encore d'évaluation

- International Business Management As Per VTUDocument141 pagesInternational Business Management As Per VTUjayeshvk97% (62)

- Revolutionizing World Trade: How Disruptive Technologies Open Opportunities for AllD'EverandRevolutionizing World Trade: How Disruptive Technologies Open Opportunities for AllPas encore d'évaluation

- Drivers of GlobalizationDocument4 pagesDrivers of GlobalizationлюдмилаPas encore d'évaluation

- Course Outline For Portfolio TheoryDocument4 pagesCourse Outline For Portfolio Theoryshariz500Pas encore d'évaluation

- Individualism and CollectivismDocument12 pagesIndividualism and CollectivismSwastik AgarwalPas encore d'évaluation

- Globalization: How It Affects International TradeDocument5 pagesGlobalization: How It Affects International TradeDuke SucgangPas encore d'évaluation

- INB372 Chapter 1 NotesDocument5 pagesINB372 Chapter 1 NotesTasin RafaPas encore d'évaluation

- Current Trends in GlobalizationDocument8 pagesCurrent Trends in GlobalizationahmedPas encore d'évaluation

- Globalisation - A-Level EconomicsDocument15 pagesGlobalisation - A-Level EconomicsjannerickPas encore d'évaluation

- International Trade Lesson 2Document7 pagesInternational Trade Lesson 2Kristen IjacoPas encore d'évaluation

- Daryl Kayle SantosDocument3 pagesDaryl Kayle Santosdarylkaylesantos21Pas encore d'évaluation

- International Marketing (Maseco 3)Document48 pagesInternational Marketing (Maseco 3)Angela Miles DizonPas encore d'évaluation

- Barriers and Drivers of GlobalisationDocument7 pagesBarriers and Drivers of GlobalisationViknesh KumananPas encore d'évaluation

- Drivers of GlobalizationDocument2 pagesDrivers of Globalizationpink pinkPas encore d'évaluation

- International Business PaperDocument8 pagesInternational Business PaperKellyPas encore d'évaluation

- Example: at Distributed Service Systems, A Small Full-Service Computer Company Located inDocument7 pagesExample: at Distributed Service Systems, A Small Full-Service Computer Company Located inRajah CalicaPas encore d'évaluation

- Drivers of International BusinessDocument4 pagesDrivers of International Businesskrkr_sharad67% (3)

- Recent Trends in World TradeDocument2 pagesRecent Trends in World TradeSamarthPas encore d'évaluation

- Global Trade Liberalization and The Developing Countries - An IMF Issues BriefDocument6 pagesGlobal Trade Liberalization and The Developing Countries - An IMF Issues BriefTanatsiwa DambuzaPas encore d'évaluation

- Q2. Globalization Reduces Employment Opportunities. Explain?Document8 pagesQ2. Globalization Reduces Employment Opportunities. Explain?Sumeet VermaPas encore d'évaluation

- International Business and Trade NOTESDocument6 pagesInternational Business and Trade NOTESAnthonete MadragaPas encore d'évaluation

- Eco HW (Globalization)Document3 pagesEco HW (Globalization)michaelpage054Pas encore d'évaluation

- Trade Policies, Developing Countries, and GlobalizationDocument37 pagesTrade Policies, Developing Countries, and Globalizationazadsinghchauhan1987Pas encore d'évaluation

- Global Business NoteDocument12 pagesGlobal Business NoteRan ChenPas encore d'évaluation

- Globalisation of Services and JobsDocument18 pagesGlobalisation of Services and JobsCharlie AngPas encore d'évaluation

- The Structure of GlobalizationDocument16 pagesThe Structure of GlobalizationRoselle Joy VelascoPas encore d'évaluation

- Lesson 1-International TradeDocument12 pagesLesson 1-International TradeJerry Len TapdasanPas encore d'évaluation

- International Business and Trade Course ExplainedDocument14 pagesInternational Business and Trade Course ExplainedReymar GallardoPas encore d'évaluation

- International Trade Is Exchange of Capital, Goods, and Services Across International Borders orDocument14 pagesInternational Trade Is Exchange of Capital, Goods, and Services Across International Borders orMithun DeyPas encore d'évaluation

- MB0053Document6 pagesMB0053Pratibha DograPas encore d'évaluation

- WTO Economics AssignmentDocument15 pagesWTO Economics AssignmentDaheem AminPas encore d'évaluation

- International Business MGT-413Document21 pagesInternational Business MGT-413sakibPas encore d'évaluation

- International Trade:: Sell Your Surplus GoodsDocument4 pagesInternational Trade:: Sell Your Surplus Goodsalichaudhary123Pas encore d'évaluation

- GlobalisationDocument5 pagesGlobalisationJasonPas encore d'évaluation

- Ie I - HandDocument80 pagesIe I - HandTaju MohammedPas encore d'évaluation

- Catch Up Friday Jan 19 1Document4 pagesCatch Up Friday Jan 19 1Reka LambinoPas encore d'évaluation

- International Trade Dissertation IdeasDocument4 pagesInternational Trade Dissertation IdeasHelpMeWithMyPaperUK100% (1)

- Internaltional ManagementDocument28 pagesInternaltional ManagementramyathecutePas encore d'évaluation

- Globalisation: Intro Globalisation Refers To The Integration of Markets in The Global Economy, Leading ToDocument6 pagesGlobalisation: Intro Globalisation Refers To The Integration of Markets in The Global Economy, Leading ToAnanya SinghPas encore d'évaluation

- Q1. Write A Note On Globalization.: 1. Trade: Developing Countries As A Whole Have Increased Their Share of World TradeDocument6 pagesQ1. Write A Note On Globalization.: 1. Trade: Developing Countries As A Whole Have Increased Their Share of World TradeYogesh MishraPas encore d'évaluation

- Chapter 01 - Globalization TrendsDocument8 pagesChapter 01 - Globalization TrendsDayah FaujanPas encore d'évaluation

- Chapter-1-GlobalizationDocument55 pagesChapter-1-Globalizationfrancis albaracinPas encore d'évaluation

- What Are The Core Features of Globalization?Document4 pagesWhat Are The Core Features of Globalization?HashimAhmedPas encore d'évaluation

- Maritime Logistics Diploma: Upon The Successful Completion of This Module, You Should Be Able ToDocument20 pagesMaritime Logistics Diploma: Upon The Successful Completion of This Module, You Should Be Able ToNadine ShaheenPas encore d'évaluation

- Globalization and The National EconomyDocument20 pagesGlobalization and The National EconomyPrachi SharmaPas encore d'évaluation

- Concept of GlobalizationDocument10 pagesConcept of GlobalizationRomario BartleyPas encore d'évaluation

- Literature Review of Wto and Developing CountriesDocument8 pagesLiterature Review of Wto and Developing CountriesafdtorpqkPas encore d'évaluation

- Globalization and Economic RelationDocument34 pagesGlobalization and Economic Relation23103601Pas encore d'évaluation

- 1 - Growth and Direction of International Trade - PPT - 1Document18 pages1 - Growth and Direction of International Trade - PPT - 1Rayhan Atunu67% (3)

- Module 1 Module in International EconomicsDocument18 pagesModule 1 Module in International EconomicsMar Armand RabalPas encore d'évaluation

- Factors That Have Enabled Global Is at IonDocument4 pagesFactors That Have Enabled Global Is at Ionواسل عبد الرزاق100% (2)

- The Trends in GlobalizationDocument2 pagesThe Trends in GlobalizationBielan Fabian GrayPas encore d'évaluation

- Macro Topic 5-1Document40 pagesMacro Topic 5-1samantha swalehPas encore d'évaluation

- International Business: An Asian PerspectiveDocument23 pagesInternational Business: An Asian PerspectiveJue YasinPas encore d'évaluation

- Globalization's Impact on Civil EngineeringDocument10 pagesGlobalization's Impact on Civil EngineeringAshadi HamdanPas encore d'évaluation

- QuickReferenceGuide IntermediateDocument2 pagesQuickReferenceGuide Intermediateshariz500Pas encore d'évaluation

- Introducing Visual Basic For ApplicationsDocument5 pagesIntroducing Visual Basic For Applicationsshariz500Pas encore d'évaluation

- Metastock Enhanced Syatem Tester Default CodingDocument1 pageMetastock Enhanced Syatem Tester Default Codingshariz500Pas encore d'évaluation

- QuickReferenceGuide IntermediateDocument2 pagesQuickReferenceGuide Intermediateshariz500Pas encore d'évaluation

- Measures To Promote Growth and DevelopmentDocument1 pageMeasures To Promote Growth and Developmentshariz500Pas encore d'évaluation

- Calculus AnswersDocument8 pagesCalculus Answersshariz500Pas encore d'évaluation

- Mayor of London: Special Fares ApplyDocument2 pagesMayor of London: Special Fares Applyshariz500Pas encore d'évaluation

- MSC Finance RankingDocument1 pageMSC Finance Rankingshariz500Pas encore d'évaluation

- Mayor of London: Special Fares ApplyDocument2 pagesMayor of London: Special Fares Applyshariz500Pas encore d'évaluation

- GlobalisationDocument6 pagesGlobalisationshariz500Pas encore d'évaluation

- June 2012 Economics Unit 4 MarkschemeDocument30 pagesJune 2012 Economics Unit 4 MarkschemeEzioAudi77Pas encore d'évaluation

- C4 January 2006 Mark SchemeDocument6 pagesC4 January 2006 Mark Schemeshariz500Pas encore d'évaluation

- June 2012 Economics Unit 4 MarkschemeDocument30 pagesJune 2012 Economics Unit 4 MarkschemeEzioAudi77Pas encore d'évaluation

- C2 Practice Paper A4 Mark SchemeDocument3 pagesC2 Practice Paper A4 Mark Schemeshariz500Pas encore d'évaluation

- Economics Unit 4 Past Year Essay QuestionsDocument4 pagesEconomics Unit 4 Past Year Essay Questionsshariz500Pas encore d'évaluation

- Malaysian Studies ProjectDocument1 pageMalaysian Studies Projectshariz500Pas encore d'évaluation

- FP2 - June 2009 PaperDocument28 pagesFP2 - June 2009 PaperchequillasPas encore d'évaluation

- Jan 2007Document24 pagesJan 2007shariz500Pas encore d'évaluation

- Chem Ark Scheme Jan 05 AsDocument15 pagesChem Ark Scheme Jan 05 Asihshan007Pas encore d'évaluation

- C2 Practice Paper A7 Mark SchemeDocument4 pagesC2 Practice Paper A7 Mark Schemeshariz500Pas encore d'évaluation

- FP2 - June 2009 PaperDocument28 pagesFP2 - June 2009 PaperchequillasPas encore d'évaluation

- Mark Scheme (Final) Summer 2008: GCE Chemistry (6243/02)Document9 pagesMark Scheme (Final) Summer 2008: GCE Chemistry (6243/02)Lara AndrewPas encore d'évaluation

- C2 Practice Paper A1 Mark SchemeDocument4 pagesC2 Practice Paper A1 Mark Schemeshariz500Pas encore d'évaluation

- United States Court of Appeals, Third CircuitDocument7 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals, Third CircuitScribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- Belonging Romulus My FatherDocument2 pagesBelonging Romulus My FatherEzio Auditore da FirenzePas encore d'évaluation

- LA DPW Engineering NewsletterDocument12 pagesLA DPW Engineering NewsletterBill RosendahlPas encore d'évaluation

- MECA News Summer 2012Document8 pagesMECA News Summer 2012Middle East Children's AlliancePas encore d'évaluation

- CITES Customs Procedure GuideDocument1 pageCITES Customs Procedure GuideShahnaz NawazPas encore d'évaluation

- Cifra Club - Pink Floyd - Another Brick in The WallDocument3 pagesCifra Club - Pink Floyd - Another Brick in The WallFabio DantasPas encore d'évaluation

- Civil Rights Movement Lesson PlanDocument3 pagesCivil Rights Movement Lesson Planapi-210565804Pas encore d'évaluation

- Doctrine of State Lesson EditDocument11 pagesDoctrine of State Lesson EditCarlos FreirePas encore d'évaluation

- DOJ Rescission Impact Equitable Sharing LetterDocument2 pagesDOJ Rescission Impact Equitable Sharing LetterJames PilcherPas encore d'évaluation

- Application For ObserverDocument4 pagesApplication For Observerসোমনাথ মহাপাত্রPas encore d'évaluation

- National Judicial Service-ThaniaDocument26 pagesNational Judicial Service-ThaniaAnn Thania Alex100% (1)

- Foucault, Race, and Racism: Rey ChowDocument15 pagesFoucault, Race, and Racism: Rey ChowNenad TomićPas encore d'évaluation

- So, Too, Neither, EitherDocument13 pagesSo, Too, Neither, EitherAlexander Lace TelloPas encore d'évaluation

- UP MDMS Merit List 2021 Round2Document168 pagesUP MDMS Merit List 2021 Round2AarshPas encore d'évaluation

- UntitledDocument2 pagesUntitledmar wiahPas encore d'évaluation

- Anderson - Toward A Sociology of Computational and Algorithmic JournalismDocument18 pagesAnderson - Toward A Sociology of Computational and Algorithmic JournalismtotalfakrPas encore d'évaluation

- Japanese Style Consulting Toolkit by SlidesgoDocument7 pagesJapanese Style Consulting Toolkit by SlidesgorealsteelwarredPas encore d'évaluation

- Secret of Shimla AgreementDocument7 pagesSecret of Shimla Agreement57i100% (1)

- Analytical ParagraphsDocument8 pagesAnalytical ParagraphsParna ChatterjeePas encore d'évaluation

- Extradition Costs To CPSDocument2 pagesExtradition Costs To CPSJulia O'dwyerPas encore d'évaluation

- Historical Background of IndonesiaDocument4 pagesHistorical Background of IndonesiaTechno gamerPas encore d'évaluation

- Government of India Act (1935) Study MaterialsDocument2 pagesGovernment of India Act (1935) Study Materialschandan kumarPas encore d'évaluation